Abstract

In recent years, the rights of trans people in the United Kingdom and elsewhere have been increasingly under scrutiny. This paper considers forms of resistance to Trans Exclusionary Radical Feminism (TERF) and neo-fascist gender conservative movements in Edinburgh, Scotland through an analysis of trans-positive stickers in public space. Using an archive of 461 images of trans-rights-related stickers photographed in Edinburgh between August 2018 and May 2022, we explore how trans-positive activism is publicly (en)countering transphobic politics and discourses. Our analysis begins by examining palimpsests of conflict, or the layerings of trans-positive and transphobic stickers – removed, written on, or covered up – in the materiality of public space. We then turn to the transformative potential of stickers as materials of resistance, arguing that trans-positive stickers can undermine transnormative, TERF and neo-fascist gender conservative ideologies and political tactics. Stickers offer public expressions of allyship, communicate political solidarity across social justice movements and marginalised communities, and also provide representations of non-normative trans identities and embodiments. Through this analysis, we present the political potential of stickers as important materials of public resistance that intervene in transphobic political and cultural discourses to produce trans-affirming encounters in public space.

Introduction

The rights of trans people in the United Kingdom (UK), and many other parts of the world, have been increasingly scrutinised and attacked in recent years (Hines, Citation2020; Pearce et al., Citation2020a). While many of these disputes about trans people’s recognition, wellbeing, and support have taken place on social media and during both in-person and online events, they are also occurring in urban public spaces. This paper explores trans activism in the city of Edinburgh, Scotland through an analysis of trans-positive stickers in public space. As geographers who are interested in ordinary, unnoticed, and often disregarded expressions of resistance, this paper serves as a collaborative effort to strengthen alliances between geographies of resistance, trans, queer, and feminist geographies and studies.

Stickers are a common sight on city streets, accompanying posters, flyers, and graffiti in their adornment of street furniture and architecture. Many stickers are dedicated to social and political movements that range from far-left to far-right, and communicate ideological affiliations by promoting protest marches or rallies, social/political groups, and radical or subversive opinions. Stickers are also an inexpensive, accessible, and relatively low-risk tactic for expressing opinions on objects in public and private spaces (Awcock, Citation2021). Despite how prevalent stickers are in the everyday makeup of our environments, they have received limited attention from scholars across disciplines (exceptions include Awcock, Citation2021, in press; Conley, Citation2020; Reershemius, Citation2019; Ritchie, Citation2019; Vigsø, Citation2010). In this paper, we call attention to the utility of stickers in illuminating dynamic political contentions surrounding trans rights, and conveying existing trans solidarities within public spheres.

Stickering is a spatial-temporal act rooted in the material present, and its ability to bring discourses into public spheres invites an opportunity to engage with the everyday politics of trans representations, subjectivities, and embodiments. This paper provides evidence of trans political geographies in mundane, ordinary urban locations. Our analysis demonstrates how trans-positive activism, expressions of trans allyship and solidarity, and non-normative trans representation publicly (en)counter transphobic politics and discourses of Trans Exclusionary Radical Feminist (TERF)Footnote1 and neo-fascist gender conservative movements. Everyday trans political geographies assert non-normative expressions of trans embodiment, illuminate forms of solidarity that validate trans rights, and contribute to shifts in public discourses about trans people that often go unseen (Marvin, Citation2022).

In this paper we apply the metaphor of palimpsests to the layerings of trans-positive and transphobic stickers as they have been removed, written on, or covered up in public space. As materials subject to the intensity of temporality, stickers can be peeled off, scratched away, crossed out, written on, or covered up within minutes, hours, or days. Elsewhere, these interactions have been called ‘sticker wars’ (Ritchie, Citation2019), but this paper employs palimpsests as a critical lens to understand conflict through stickers. The metaphor of palimpsest-as-landscape has been used in geography, urban planning, and archaeology, describing a place “in which layers of history simply overlie and partly obscure and erase ones that went before” (Massey, Citation2011, p. 24). This horizontal layering has been critiqued by geographers like Doreen Massey as a flattening spatial concept that fails to consider the dynamic interplays of power and space between pasts, presents, and futures (Holt & Ashmore, Citation2020, p. 1; see also Bartolini, Citation2014).

While we align with this critique, we diverge from the largely visual readings of palimpsests by taking their materiality seriously, especially when “material residues” are made partial or fragmented through people’s interactions with stickers (DeSilvey, Citation2007, p. 420). Applying palimpsests to stickers attends to their material forms, including their size, texture, strength of adhesive, design, and ability to be peeled. This reading of stickers has clear parallels with the ways trans subjectivities and experiences complicate binaries of mind/body and intimate that identity production occurs “in a shifting field of distributed potentialities and relations…” (Brice, Citation2021, p. 305). Following Brice’s (Citation2021) reminder that trans subjectifications trouble the subject-object dynamic, we exercise the metaphor of palimpsests as a trans theoretical drive to agitate additional binaries of visual/material, time/space, and political/cultural. Palimpsests complicate understandings of how time, politics, power, and identity play out in both physical and cultural landscapes. Framing stickers as palimpsests reads time and space together through various forms of representation and materiality, and invites opportunities for in-depth critical engagement with political conflict. Specifically, our theoretical exercise encourages a deeper appreciation of the political tensions and contestations that emerge materially and discursively through trans expressions and representations.

Our paper analyses how trans-positive stickers bring visibility to non-transnormativeFootnote2 gendered identities and embodiments, as well as overlapping political solidarities between trans, queer, feminist, and women’s communities. Trans-positive stickers wield a potential to undermine transphobic discourses through the allegiances they cultivate with other communities, identities, and political movements. While it is often not possible to know why a sticker was placed, removed, or altered, the material interactions people have with stickers can convey different contestations around trans rights. In what follows, we explore how trans-positive stickers counter TERF and neo-fascist gender conservative political tactics to splinter trans people and rights from other marginalised communities. As well, we demonstrate how trans-positive stickers further support the existing relationships between “cis lesbian and trans identities and communities [which] have been represented almost exclusively in negative terms—framed as border crossings, trespassing, battlegrounds, and conquests” (Beemyn & Eliason, Citation2016, p. 2). Our analysis signals how scholarship about everyday, often overlooked acts of resistance can reveal the current and developing landscapes of coalition building and trans solidarity in the face of increasingly vocal and active transphobic movements.

Trans-positive stickers in Edinburgh

Recent scholarly imperatives have sought to redefine resistance as inclusive of more everyday, less visible, emergent, spontaneous, and ambiguous acts (Horton & Kraftl, Citation2009; Luger, Citation2016). Prescribing resistance risks excluding and invisibilising emergent modes of resistance that do not necessarily conform to traditional presentations of resistance as large-scale, organised, public displays of protest (Chatterton & Pickerill, Citation2010; Hughes, Citation2020). Interventions by feminist, critical race, queer, trans, Indigenous, and post-colonial scholarship contribute to the project of uncovering resistance in unexpected and overlooked places, including through the body (Vasudevan et al., Citation2022), imagination (Cahuas, Citation2021; Rosenberg, Citation2017b), memory and knowledge (Daigle, Citation2016, Citation2019; Ware, Citation2017), and social relations (Rosenberg, Citation2021). A small but growing body of literature is also expanding how resistance is understood by exploring political stickers, attending to them as ephemeral, frequently overlooked forms of political engagement in public space (Awcock, in press; Conley, Citation2020; Ritchie, Citation2019).

Stickers are a declaration of presence and provide a way of claiming space for particular social movements, cultural affiliations, and political perspectives (Awcock, Citation2021; Vigsø, Citation2010). Often, the spatial concentration of stickers can impress that a particular view is strong and widespread, even though it could easily be the work of a single, enthusiastic person placing the stickers in a given area (Ritchie, Citation2019). While some writing explores how stickers are used in relation to specific political topics and events—like the 2014 Scottish independence referendum (Ritchie, Citation2019) and Brexit (Awcock, in press)—their connections to trans advocacy have yet to be explored. However, forms of trans-related street media are noted to powerfully charge spaces with a sense of inclusion and belonging, alongside vulnerability through increased visibility (Malatino, Citation2019; Montgomery, Citation2020). As similar materials of visual representation, stickers provide an additional lens for analysing the impacts of trans representation on trans communities, trans (solidarity) politics, and public space.

The material for this paper is an archive of 461 images of trans-rights-related stickers, photographed by Hannah (one of the authors) in Edinburgh between August 2018 and May 2022. Most stickers were photographed from August 2020 onwards after a noticeable increase in trans-related stickers. The stickers were found across the city (including the city centre, Leith, Abbeyhill, and Morningside) on a range of street furniture, including lampposts, bollards, phone boxes, street and road signs, bus shelters, pedestrian crossings, and junction boxes. Of the 461 photographs taken during the data collection, 141 include stickers with transphobic content while 350 feature trans-positive sentiment. Photographs of stickers were analysed by theme, including conflict, community solidarity, and intersecting political issues (such as Scottish independence and reproductive justice). Our thematic analysis was then furthered by distinguishing different representations of conflict (such as physical changes to stickers), forms of solidarity, identity, and embodiment. This paper focuses solely on trans-positive stickers to avoid amplifying transphobic perspectives, and to build scholarship on how trans activists are resisting the backlash against trans rights by TERF and neo-fascist gender conservative political ideologies.

Sticker designs vary in frequency and new stickers appeared throughout the study period. However, there are some trends in the design of stickers, particularly those with trans-positive messages. The size of stickers varies from a few centimetres to the size of a postcard, and the vast majority include some text, with common slogans including “Trans rights are human rights,” “Trans people are welcome here”, and “You/We belong here.” Some of the trans-positive stickers assembled in the archive use stand-alone images or symbols, while others combine text with imagery and symbols including trans and anti-fascist iconography, clasped hands, clenched fists, hearts, the Edinburgh skyline, various pride flags (or flag colour-schemes), and images of activists (such as Angela Davis, Kuchenga, and Sylvia Rivera). While the stickers were gathered in a range of locations across Edinburgh, we cannot claim that the stickers forming our argument are representative of trans-rights stickers across the entire city, as the stickers captured follow Hannah’s particular everyday movements. Nevertheless, the images collected provide insight into the struggles over, and discourses of, trans solidarities and resistances in the face of increasing TERF and neo-fascist gender conservative transphobia in Edinburgh.

Scotland in the international neo-conservative gender panic

Tensions surrounding trans rights in Edinburgh have emerged in response to local contexts, as well as larger, international trends of rising conservatism and neo-fascism, of which transphobia is just one manifestation (Gusmeroli, Citation2023; Hines, Citation2020; Pearce et al., Citation2020a). Over the past decade, transphobia “has been increasingly adopted by far-right organisations and politicians in numerous American, European and African states” (Pearce et al., Citation2020a, p. 681). In the United States (US), moral panics about trans people have been heralded by conservative politicians and Christian groups which have challenged legal measures of protecting and supporting trans communities (Pearce et al., Citation2020a). TERF organisations, like the Women’s Liberation Front and Deep Green Resistance’s Women’s Caucus, have supported these groups and their various initiatives by participating in conservative think-tanks, transphobic conservative political campaigns, and legal challenges that target and denigrate trans people at the federal and state level across the US (Barefoot, Citation2021; Pearce et al., Citation2020a). Beyond the US, politicians in right-wing governments such as in the UK and Hungary have used the COVID-19 pandemic to argue for the rolling back of trans rights, and transphobia has been found to strongly correlate with right-wing ideologies in the UK, Italy, and Belgium (Gusmeroli, Citation2023; Makwana et al., Citation2018; Pearce et al., Citation2020b).

These international trends are filtered through local cultural and political specificities within the UK, where religious and conservative transphobic rhetoric is often expressed through white middle-class ‘feminism’ (Pearce et al., Citation2020b). Transphobic sentiment in the UK has surged since the 2018 public consultation for the UK’s Gender Recognition Act reform, including increased TERF organisational meetings across the UK, and transphobic vitriol circulating on digital media platforms like Twitter and Mumsnet (Pearce et al., Citation2020a). In Scotland, Edinburgh has been the focus of particularly intense trans rights ‘debates’ due to its association with transphobic author JK Rowling (Gardner, Citation2022). Public attention to trans rights has substantially increased in Scotland since the Scottish National Party (SNP) pledged to pass the Gender Recognition Reform (Scotland) Bill during the 2016 Scottish Parliamentary elections. Conversations surrounding trans rights continued through the Bill’s introduction to the Scottish Parliament in early 2022. Although this legislation was passed by the Scottish Parliament in December 2022, the Bill was blocked in January 2023 by the right-wing Conservative UK government. This is the first time a Scottish Bill has been blocked by the UK government since the Scotland Act 1998 was passed, which devolved some decision-making powers to the Scottish Parliament over matters such as healthcare, social services, education, wellbeing, and the rights of the people in Scotland. As an unprecedented move that curtailed the democratic rights of Scotland to govern, the links between transphobic and conservative political movements have been further cemented into UK politics and culture. Given these events, the topic of trans rights is particularly prominent in Edinburgh as Scotland’s capital city and home to the Scottish Parliament.

Impacts of trans representation

Gender is attached to social, cultural, and political practices that are anchored in space, with unique consequences for trans people, who experience increased visibility and vulnerability to gender policing in public and semi-public spaces (Brice, Citation2020; Doan, Citation2010). While visibility is often celebrated and encouraged by mainstream LGBTQ + political movements, it is often a source of increased proximity to violence and death for trans people, particularly trans women of colour (Williams, Citation2020). Given the routine antagonisms that trans people encounter in public, digital spaces (such as online forums and social media) are frequently alternative sites for trans-majority social encounters (Malatino, Citation2020, p. 68). Trans-majority spaces in physical environments, like conventions and protests, often occur in fleeting events that temporarily transform spaces to provide comfort and ease for trans people (Doan, Citation2007). While queer public and semi-public spaces are assumed to be more inclusive of diverse gender expressions and identities, they often instead reinforce gender norms and white masculine privilege, and function as unwelcoming, hostile, and unsafe environments for trans people—especially for those who are low-income, racialised, and young (Hanhardt, Citation2013; Rosenberg, Citation2017a, Citation2021).

Trans representation can reproduce normativities that negatively impact trans people, regardless of the mediums or the intentions to express trans inclusion, allyship, or positivity (Malatino, Citation2020; Marvin, Citation2022). Malatino (Citation2020) notes that for some trans people, trans visibility has culturally anchored transnormative ideals of ‘passing’ and and ‘transitioning’. However, many trans people struggle to access medical care that would generate such futures (Malatino, Citation2019). Transnormative discourses hinge upon, and render legibility to, a future embodiment in which gender is registered by others’ cisnormative perceptions and confirmations of gender, rather than one’s own sense of self (Bey, Citation2017). Trans people who are made illegible through transnormative visibility are dismissed in mainstream trans discourses, and prospects of exploring and celebrating diverse trans subjectivities and embodiments are foreclosed.

Rather than seeking expressions bent on a transnormative future of gender recognition, it is imperative to identify non-normative trans representation as a means of countering transphobia, and celebrating the range of trans existence and corporeality in the present. Stickers are one way to attend to this material nowness by temporally countering transphobia through discursive and representational claims in the built environment. In what follows, we trace the fleeting, public assertions of conflict and solidarity that emerge through trans rights stickers in Edinburgh. First, we explore the material and visual signifiers of political contestations through stickers as palimpsests. We then engage with the discourses of trans resistance that emerge in trans rights stickers, how they transform trans encounters with public space, and the unexpected forms of recognition they transmit through their resistance to transphobia.

Palimpsests of conflict

Stickers are expressions of political ideologies that can be contested through their physical forms. Palimpsests of conflict can encapsulate these discursive and representational struggles through, for example, the layering, removal, and covering of stickers. In palimpsests, traces of conflict are fragmentary, partial, and incomplete; unless each interaction with the palimpsest is witnessed, it is impossible to know exactly how it developed. Reading stickers as palimpsests of conflict enables us to trace the dynamics between trans-positive and transphobic discourses, and how they assert territorial claims in public space by charging meaning—however momentarily—to a street, corner, or pedestrian crossing. Of the 95 images in the collection that we categorise as palimpsests, most contain two or three layers of stickers, as demonstrated in the top two images of . Many of the palimpsests involve multiple stickers that have been ripped off, put back on, or covered up over time, like the two bottom images of and .

Figure 1. Palimpsests of conflict are created when a sticker is partially or completely removed, covered up, written on, or otherwise altered or obscured, sometimes multiple times (Photos by Hannah Awcock).

Figure 2. Reading palimpsests of conflict on a lamppost in Abbeyhill, Edinburgh. The photos were taken, from left to right, on the 3rd, 4th, and 6th of October 2021. Each time, another layer had been added or removed (Photos by Hannah Awcock).

While we cannot definitively know the motives behind interactions with stickers, the topic of trans rights can provide a strong impression of intent. The top left image in , for example, depicts a yellow transphobic stickerFootnote3 at a bus stop that is partly torn, covered up with black marker, and replaced with trans-positive messages (“trans is beautiful” and “bus ads support trans rights”). While the original sticker’s transphobic message has been countered with trans-positive content, a lingering trace of transphobia remains at the bus stop, indicating the conflicting aims of different actors interacting with the sticker. Similar traces are evidenced in the two lower images in , where layers of previous stickers with conflicting sentiments around trans rights are visible. Two stickers stating “trans people are welcome here,” and one sticker claiming “my feminism is trans inclusive,” were used to conceal transphobic stickers, but were then torn off—likely to remove the trans-positive content, as signified by the marked effort to obscure the stickers. Contestations signalled by the material changes to stickers are less clear in the lower of the two stickers in the bottom-left image. This torn “trans people are welcome here” is accompanied by another sticker possibly above or below it, indicated by folds, adhesive, and colours that do not match, as well as a design that is visibly recognisable as the common trans-positive sticker: “queer Edinburgh for trans rights.” While it can be difficult to decipher the meaning of stickers that have been almost entirely removed/covered, the material state of these stickers illuminates numerous challenges surrounding trans rights.

In addition to the material conditions and layerings of stickers, ideological contestations regarding trans rights also manifest through sticker design and language. Some stickers, like that on the top right of , are designed with the explicit aim of identifying and concealing transphobia. By naming the “transphobic shite” below this sticker, the sloth sticker identifies that transphobia has occurred here, but also communicates that it is being opposed and countered. In another deliberate design effort, the black sticker in parodies a common transphobic sticker that mimics a dictionary definition of ‘woman’ as an “adult human female,” using the same font, colour scheme, and style of the transphobic stickers. These transphobic stickers publicly assert the biological essentialism that underpins transphobic and TERF beliefs, which have been used in recent conservative political movements to ban trans girls and women from women’s spaces such as bathrooms and athletic activities (Pearce et al., Citation2020a). Imitating a dictionary definition further attempts to fix categories of gender and emphasise immutable ‘truths’ about gender through a categorical, knowable explanation of a word. To counter these transphobic beliefs, the sticker in offers a definition for ‘transphobia’ as an “irrational fear of transgender people.” Its design also appropriates the transphobic sticker’s attempt to present gender through a (literally and ideologically) black and white framework, and like the sloth sticker in , names the transphobic intent of the stickers to which it is responding.

As with the stickers in , demonstrates the amalgamation of material and visual cues as ways of altering meaning and making ideological claims through the built environment. In the far-left image of , the trans-positive intent of the sticker was altered by a transphobic viewer who scratched out the ‘ir’ from ‘irrational’, changing the sticker to state “rational fear of transgender people.” By the day after the first photo was taken, the previously altered trans-positive sticker was replaced with a new version (as depicted in the centre image of ), displaying a trans-positive message once again. Two days later, however, the newly replaced sticker had been removed (far-right image of ). While this removal left the first sticker almost completely obscured, it also gave visibility to an additional alteration that was not captured before the new sticker had been placed: the altered word of ‘rational’ had been scratched out. As a result, the sticker subsequently defined transphobia as a “fear of transgender people.” The speed at which the exchange in takes place suggests an intense struggle over transphobic discourses in public space. Such dynamic interchanges demonstrate the ferocity with which trans rights are being both attacked and defended in Edinburgh. These contestations locally anchor national and global discourses surrounding trans rights that circulate widely in the current context of expanding TERF and neo-fascist gender conservative movements.

Discourses of trans resistance

In addition to the material and visual conflicts evidenced in trans-related stickers, TERF and neo-fascist gender conservative movements are discursively antagonised through the political solidarities, non-normative trans embodiments and subjectivities conveyed in trans-positive stickers. Trans-positive stickers frequently depict existing allegiances amongst trans and queer communities, with statements including “#LGBWithTheT,” “bisexual and trans solidarity,” “queer Edinburgh for trans rights,” and “lesbians for trans rights” overlayed onto combinations of the trans, genderqueer and progress pride flags. Trans solidarity is also implicated beyond the LGBTQ +community through statements such as “punks against transphobia” or “anti-transphobic action” accompanied by the trans pride colours and other iconography, like anti-fascist symbols.

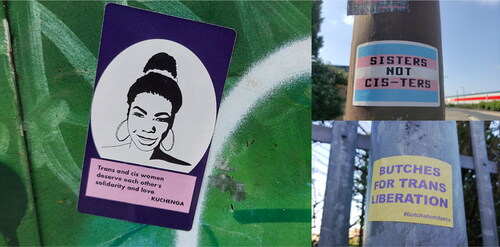

Conveying solidarities between trans, feminist, and women’s communities/movements undermines TERF tactics of minimising trans inclusive feminism. TERF discourses commonly claim that the opinions of a minority are that of the majority. For example, while most Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival attendees expressed a desire to include trans women in a 1992 survey, the organisers not only maintained their trans exclusionary policy, but also suppressed records of trans inclusive activism by cis women at their events (Williams, Citation2020). Expressing solidarities amongst trans women and/or feminine people, broader trans communities, feminists, and cis women can counter TERF discourses and political strategies by reminding the public of existing trans allyship amongst cis women and feminists (see ) (Currans, Citation2023; Gill-Peterson, Citation2022).

Figure 3. Stickers that reflect solidarity between trans people, women, and broader LGBQ + communities/identities (Photos by Hannah Awcock).

The sticker on the left of features a portrait of Kuchenga, a well-known Black trans activist and writer in the UK, with the statement “Trans and cis women deserve each other’s solidarity and love.” By publicly acknowledging a current deficit of support between trans and cis women, and calling for different practices of care and solidarity, this sticker directly counters TERF attempts to splinter women’s communities and foster antagonisms amongst women. Existing sentiments of solidarity are also amplified amongst various gender identities in the other anti-TERF stickers in : “sisters not cis-ters" and “butches for trans liberation.” Both stickers redefine structures of gendered political allegiance outside of biological essentialist ideas of womanhood and femininity, bringing other gendered descriptors like “butch” alongside calls for trans rights. The term “butch” has a strong history in lesbian communities, although it can be claimed by a person of any gender and sexual orientation. Such statements, as well as others noted earlier, like “bisexual and trans solidarity” and “lesbians for trans rights,” increase the legibility of diverse gendered and sexual identities, while also articulating how queer and trans communities stand alongside each other. Doing so fortifies the sense of trans allyship amongst queer communities, publicly displaying camaraderie through challenging discriminatory politics and normative ideas of sexuality and gender. Assertions like these weaken the increasingly visible TERF and neo-fascist gender conservative discourses that attempt to pit trans and other marginalised communities against each other (Gailey & Brown, Citation2016). Collectively, these alliances express that trans rights are relevant to, and supported by, a wider range of people and communities (including, but not limited to, cis women).

As noted earlier, TERF and neo-fascist gender conservative politics try to assert immutable, stable truths about gender in response to gender panics that hinge upon the breakdown of ‘natural’ orders of sex and gender (Pearce et al., Citation2020a). It is often trans people, gender non-conforming people, people of colour, people with disabilities, and Indigenous peoples who agitate biological essentialist ideologies of TERF and neo-fascist gender conservative discourses, and, as such, are frequently invisibilised, refused, and unrecognised (Malatino, Citation2020). However, some stickers—like those in —interrupt singularising narratives of trans experiences and bring representation to diverse trans identities and bodies.

Figure 4. Stickers rejecting singularising narratives of trans identities and providing celebratory recognition of diversity amongst trans people (Photos by Hannah Awcock).

On the right of is a sticker stating “women are more than wombs” in the colours of the genderqueer flag and the British women’s suffrage movement. The top left sticker references the neoclassical sculpture The Three Graces, depicting Zeus’ three daughters with external genitals and gonads that differ from the original piece. These figures are overlayed onto the trans flag, and the words “support your sisters not just cisters” are placed around their lower bodies. These two stickers publicly assert embodiments of trans womanhood and/or femininity as detached from transnormative narratives of gendered subjectivity through medicalised transitions and ‘passing’ as cisgender. Womanhood and/or femininity are visually accompanied by a diverse range of upper and lower body parts, as well as a lack of wombs, rather than cisnormative biological symbolism. The play on The Three Graces communicates this further by subverting a traditional and eminent artwork to convey non-transnormative representation through beauty and intimacy. In destabilising transnormative ideas of trans embodiment, these stickers bring legibility to trans women’s and/or feminine people’s bodies in ways that resist the biological essentialism wielded by TERF and neo-fascist gender conservative politics to create a trans exclusive category of woman and/or femininity (Beemyn & Eliason, Citation2016; Williams, Citation2020). Womanhood and femininity exist regardless of the presence or absence of visible genitals, gonads, and reproductive organs: a sentiment these stickers pull into public view.

Reflecting non-transnormative trans embodiment through neoclassical artwork also challenges TERF and neo-fascist gender conservative discourses claiming that trans people are a current phenomenon rooted in liberal politics, ‘global elitism’, and neoliberalism (Gusmeroli, Citation2023; Pearce et al., Citation2020a). Time is further wielded as a means of shifting transnormative discourses, as these two stickers depict trans embodiment without fixing a future direction of medicalised transitioning in public forms of trans representation. Rather, these stickers publicly witness womanhood and/or femininity in their multiplicities and, in so doing, set a present course to challenge transnormative narratives of futurity within trans representation.

The stickers in also depict a range of sexual and gender identities amongst trans people in their statements that “butch trans women know the truth #butchabundance,” and “trans dykes are vibrant and hot #transfemmes.” These affirming stickers bring visibility to diverse sexual and gendered identities and expressions amongst trans people, including butch trans women who do not conform to binary or traditional conceptualisations of womanhood as feminine. This diverse trans representation orients stickers towards a queer and trans audience of various identities through insider language like “dykes” and “transfemmes,” as well as stating that “butch trans women know the truth”: a truth that only butch trans women viewing the sticker can know, and those who have butch trans women in their lives can appreciate. Such visibility invites a multitude of gender and sexual identities amongst trans people into public space through an affirming politics of representation. Like the stickers in , these forms of trans visibility and allyship challenge TERF and neo-fascist gender conservative attempts to pit trans communities against other marginalised communities, such as queer and lesbian women’s communities (Rossiter, Citation2016; Webster, Citation2022).

Counteractions of coalitional presents and futures

Transphobic ideologies occupy a pronounced space within our political, social, and physical environments through the increased presence of TERF and neo-fascist gender conservative movements. In response, trans activism is increasingly challenging this hostility through creative and smaller-scale modes of resistance, including stickering. Stickers demonstrate palimpsests of conflict across the city of Edinburgh, conveying layers of contested interactions around the topic of trans rights. In identifying and challenging transphobia in public spaces, trans-positive stickers undermine and reclaim the discursive and territorial circulation of transphobic TERF and neo-fascist gender conservative beliefs. Trans-positive stickers are powerful forms of representation and visibility that play a significant role in temporarily shifting public urban landscapes into trans-affirming spaces. While the visibility of public resistance against TERF and neo-fascist gender conservativism can pose risks to the safety and wellbeing of trans people, the covert nature of stickering provides an alternative means of resistance for trans people and allies to wield in the public sphere. Such agentic political acts combat the splintering of identity politics by offering visibility to cross-community solidarities, and celebrating diverse and underrepresented trans experiences that speak to the overlapping nature of multiple identities.

The nuanced trans visibility featured in these stickers offsets the conventional and normative codes of femininity expressed through TERF and neo-fascist gender conservative political discourses. Trans people, experiences, and identities are represented in their multiplicities, which generates overlapping allegiances between trans people and other marginalised communities—notably lesbian, queer, and feminist women—often falsely presented in conflict through TERF and neo-fascist gender conservative narratives. Publicly countering these discourses by presenting commonalities and shared identities between trans people, lesbian women, and feminist women invites further consideration of the evolution of lesbian identities as political strategies against TERF, neo-fascist gender conservative, and other hate-based movements (Webster, Citation2022). For example, stickers featured in that refuse biological essentialism pull trans and reproductive rights together against TERF and neo-fascist gender conservative ideologies that target medical access for trans people and cis women alike. In the wake of the decision by the US Supreme Court to reverse access to safe abortions, trans and feminist political solidarities can unify struggles against hate-based politics and strengthen social justice movements (Sutton, Citation2023). Trans-positive stickers like those in and also provide material and visual antidotes to the false narratives that trans and cis women do not share spaces, work in coalitions, and build relationships, intimacies, and communities together (Hines, Citation2020). In doing so, trans-positive stickers interrupt attempts of TERF and neo-fascist gender conservative ideologies to “[use] our bodies as instruments of… violence by acting as straightening rods policing gender” (Perkins, Citation2022, p. 197), and instead contribute to the present and future political momentum of trans, queer, lesbian, and feminist political solidarities.

The interactions between people and stickers, as well as the ways stickers are designed, phrased, placed, and layered upon each other, constitute fierce struggles over politics and social justice in public space. Gender panics amongst TERF and neo-fascist gender conservative movements are certainly present in Edinburgh, reflecting the rising transphobia in the UK and elsewhere. However, trans-positive stickers interrupt the hold of gender panic in Edinburgh’s public imaginary by asserting the tenacious insistence of a present in which trans people are recognised, and exist in solidarity, through differences, non-normative embodiments, and powerful cross-community allegiances.

Disclosure of interest statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to the editors of this special issue for supporting our submission in this timely and critical intervention. We are grateful for the thoughtful and generous feedback of our anonymous reviewers, and for the initial comments we received when first presenting content for this paper at the Feminist Geography Conference in 2022.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Hannah Awcock

Hannah Awcock researches the ways activists and social movements claim rights to urban public and discursive spaces through examples of historical and contemporary activism and resistance. She received her PhD from Royal Holloway, University of London in 2018.

Rae Rosenberg

Rae Rosenberg is a Lecturer of Human Geography in the School of GeoSciences at the University of Edinburgh. His work explores the contestations of living and forms of resistance amongst multiply-marginalised LGBTQ2+ people.

Notes

1 Trans Exclusionary Radical Feminism/Feminists refers to a movement of self-proclaimed radical feminism that opposes trans rights. TERF ideologies are rooted in biological essentialism, or the belief that sex assigned at birth is an immutable category and is synonymous with gender. TERFs use this concept to falsely claim that trans women are men and trans men are women. TERFs argue that trans inclusion and existence are antithetical to feminism; and, in particular, that trans women seek to invade/infiltrate cis women’s spaces, appropriating cis women’s experiences and subjectivities.

2 Transnormativity describes the reproduction of heteronormative, cisnormative, and often white understandings of gender and sex through trans recognition and visibility. Transnormativity attaches trans subjectivities to medicalised discourses of transitioning that rely on binarist, biological essentialist, and linear ideologies of gendered embodiment (Malatino, Citation2019). For most trans people who cannot and/or do not want to reside in normative registers of gendered embodiment, their experiences, subjectivities, and bodies are rendered impossibilities and become illegible, particularly in public and mainstream spheres.

3 The archive of images contains unobscured versions of the stickers included in Figures 1 and 2, allowing us to gauge the original intentions of stickers as transphobic or trans-positive.

References

- Awcock, H. (2021). Stickin’ it to the man: The geographies of protest stickers. Area, 53(3), 522–530. https://doi.org/10.1111/area.12720

- Awcock, H. (In press). Bollocks to Brexit: The geographies of Brexit protest stickers, 2015–21. In S. Hughes (Ed.), Critical geographies of resistance. Edward Elgar.

- Barefoot, A. (2021). Women-only spaces as a method of policing the category of woman. In B. Gökarıksel, M. Hawkins, C. Neubert, & S. Smith (Eds.), Feminist geography unbound: Discomfort, bodies, and prefigured futures (pp. 158–179). West Virginia University Press.

- Bartolini, N. (2014). Critical urban heritage: From palimpsest to brecciation. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 20(5), 519–533. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2013.794855

- Beemyn, G., & Eliason, M. (2016). The intersections of trans women and lesbian identities, communities, and movements: An introduction. Journal of Lesbian Studies, 20(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/10894160.2015.1076232

- Bey, M. (2017). The trans*-ness of Blackness, the Blackness of trans*-ness. TSQ: Transgender Studies Quarterly, 4(2), 275–295. https://doi.org/10.1215/23289252-3815069

- Brice, S. (2020). Geographies of vulnerability: Mapping transindividual geometries of identity and resistance. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 45(3), 664–677. https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12358

- Brice, S. (2021). Trans subjectifications: Drawing an (im)personal politics of gender, fashion, and style. GeoHumanities, 7(1), 301–327. https://doi.org/10.1080/2373566X.2020.1852881

- Cahuas, M. C. (2021). Researching for El Mundo Zurdo: Imagining-creating-living Latinx decolonize feminist geographies in Toronto. Gender, Place & Culture, 28(9), 1213–1233. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2020.1786015

- Chatterton, P., & Pickerill, J. (2010). Everyday activism and transitions towards post-capitalist worlds. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 35(4), 475–490. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-5661.2010.00396.x

- Conley, J. (2020). “Voting, votive, devotion: “I voted” stickers and ritualization at Susan B. Anthony’s grave.” Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion, 36(2), 43–62. https://doi.org/10.2979/jfemistudreli.36.2.05

- Currans, E. (2023). Forging gender and racial solidarities at trans-inclusive women’s festivals. Journal of Lesbian Studies, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/10894160.2023.2187160

- Daigle, M. (2016). Awawanenitakik: The spatial politics of recognition and relational geographies of Indigenous self-determination. The Canadian Geographer / Le Géographe Canadien, 60(2), 259–269. https://doi.org/10.1111/cag.12260

- Daigle, M. (2019). Tracing the terrain of Indigenous food sovereignties. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 46(2), 297–315. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2017.1324423

- DeSilvey, C. (2007). Salvage memory: Constellating material histories on a hardscrabble homestead. Cultural Geographies, 14(3), 401–424. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474474007078206

- Doan, P. (2007). Queers in the American city: Transgendered perceptions of urban space. Gender, Place & Culture, 14(1), 57–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/09663690601122309

- Doan, P. (2010). The tyranny of gendered spaces: Reflections from beyond the gender dichotomy. Gender, Place & Culture, 17(5), 635–654. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2010.503121

- Gailey, N., & Brown, A. D. (2016). Beyond either/or: Reading trans* lesbian identities. Journal of Lesbian Studies, 20(1), 65–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/10894160.2015.1076233

- Gardner, A. (2022, January3). A complete breakdown of the J.K. Rowling transgender-comments controversy. Glamour. https://www.glamour.com/story/a-complete-breakdown-of-the-jk-rowling-transgender-comments-controversy

- Gill-Peterson, J. (2022). Toward a historiography of the lesbian transsexual, or the TERF’s nightmare. Journal of Lesbian Studies, 26(2), 133–147. https://doi.org/10.1080/10894160.2021.1979726

- Gusmeroli, P. (2023). Is gender-critical feminism feeding the neo-conservative anti-gender rhetoric? Snapshots from the Italian public debate. Journal of Lesbian Studies, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/10894160.2023.2184908

- Hanhardt, C. B. (2013). Safe spaces: Gay neighborhood history and the politics of violence. Duke University Press.

- Hines, S. (2020). Sew wars and (trans) gender panics: Identity and body politics in contemporary UK feminism. The Sociological Review, 68(4), 699–717. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038026120934684

- Holt, Y., & Ashmore, R. (2020). Introduction: Layered landscapes. Arts, 9(1)(31), 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts9010031

- Horton, J., & Kraftl, P. (2009). Small acts, kind words and ‘not too much fuss’: Implicit activisms. Emotion, Space and Society, 2(1), 14–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emospa.2009.05.003

- Hughes, S. M. (2020). On resistance in human geography. Progress in Human Geography, 44(6), 1141–1160. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132519879490

- Luger, J. (2016). Singaporean ‘spaces of hope?’ Activist geographies in the city-state. City, 20(2), 186–203. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2015.1090187

- Makwana, A. P., Dhont, K., De Keersmaecker, J., Akhlaghi-Ghaffarokh, P., Masure, M., & Roets, A. (2018). The motivated cognitive basis of transphobia: The roles of right-wing ideologies and gender role beliefs. Sex Roles, 79(3–4), 206–217. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-017-0860-x

- Malatino, H. (2019). Future fatigue: Trans intimacies and trans presents (or how to survive the interregnum). TSQ: Transgender Studies Quarterly, 6(4), 635–658. https://doi.org/10.1215/23289252-7771796

- Malatino, H. (2020). Trans care. University of Minnesota Press.

- Marvin, A. (2022). Short-circuited trans care, t4t, and trans scenes. TSQ: Transgender Studies Quarterly, 9(1), 9–27. https://doi.org/10.1215/23289252-9475481

- Massey, D. (2011). Landscape/space/politics: An essay. https://thefutureoflandscape.wordpress.com/landscapespacepolitics-an-essay/

- Montgomery, M. (2020). Trans happiness is real’: Transphobic and transpositive street media in Oxford [Unpublished master’s thesis]. University of Oxford.

- Pearce, R., Erikainen, S., & Vincent, B. (2020a). TERF wars: An introduction. The Sociological Review, 68(4), 677–698. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038026120934713

- Pearce, R., Erikainen, S., & Vincent, B. (2020b). Afterword: TERF wars in the time of COVID-19. The Sociological Review, 68(4), 882–888. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038026120934712

- Perkins, K. J. (2022). Willful lives: Self-determination in lesbian and trans feminisms. Journal of Lesbian Studies, 26(2), 194–198. https://doi.org/10.1080/10894160.2021.1997073

- Reershemius, G. (2019). Lamppost networks: Stickers as a genre in urban semiotic landscapes. Social Semiotics, 29(5), 622–644. https://doi.org/10.1080/10350330.2018.1504652

- Ritchie, E. (2019). Yes after no: The indyref landscape, 2014–16. Journal of British Identities, 2, 1–30.

- Rosenberg, R. (2017b). When temporal orbits collide: Embodied trans temporalities in U.S. prisons. Somatechnics, 7(1), 74–94. https://doi.org/10.3366/soma.2017.0207

- Rosenberg, R. D. (2017a). The whiteness of gay urban belonging: Criminalizing LGBTQ youth of color in queer spaces of care. Urban Geography, 38(1), 137–148. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2016.1239498

- Rosenberg, R. D. (2021). Negotiating racialised (un)belonging: Black LGBTQ resistance in Toronto’s gay village. Urban Studies, 58(7), 1397–1413. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098020914857

- Rossiter, H. (2016). She’s always a woman: Butch lesbian trans women in the lesbian community. Journal of Lesbian Studies, 20(1), 87–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/10894160.2015.1076236

- Sutton, B. (2023). Abortion rights in the crosshairs: A transnational perspective on resistance strategies. Journal of Lesbian Studies, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/10894160.2023.2174682

- Vasudevan, P., Ramírez, M. M., González Mendoza, Y., & Daigle, M. (2022). Storytelling earth and body. Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 0(0), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2022.2139658

- Vigsø, O. (2010). Extremist stickers: Epideitic rhetoric, political marketing, and tribal demarcation. Journal of Visual Literacy, 29(1), 28–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/23796529.2010.11674672

- Ware, S. M. (2017). All power to all people? Black LGBTTI2QQ activism, remembrance, and archiving in Toronto. TSQ: Transgender Studies Quarterly, 4(2), 170–180. https://doi.org/10.1215/23289252-3814961

- Webster, L. (2022). Erase/rewind: How transgender Twitter discourses challenge and (re)politicize lesbian identities. Journal of Lesbian Studies, 26(2), 174–191. https://doi.org/10.1080/10894160.2021.1978369

- Williams, C. (2020). The ontological woman: A history of deauthentication, dehumanization, and violence. The Sociological Review, 68(4), 718–734. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038026120938292