Abstract

Anaphylaxis is a life-threatening condition with a known effective prehospital intervention: parenteral epinephrine. The National Association of EMS Physicians (NAEMSP) advocates for emergency medical services (EMS) providers to be allowed to carry and administer epinephrine. Some states constrain epinephrine administration by basic life support (BLS) providers to administration using epinephrine auto-injectors (EAIs), but the cost and supply of EAIs limits the ability of some EMS agencies to provide epinephrine for anaphylaxis. This literature review and consensus report describes the extant literature and the practical and policy issues related to non-EAI administration of epinephrine for anaphylaxis, and serves as a supplementary resource document for the revised NAEMSP position statement on the use of epinephrine in the out-of-hospital treatment of anaphylaxis, complementing (but not replacing) prior resource documents. The report concludes that there is some evidence that intramuscular injection of epinephrine drawn up from a vial or ampule by appropriately trained EMS providers—without limitation to specific certification levels—is safe, facilitates timely treatment of patients, and reduces costs.

Introduction

Anaphylaxis is a life-threatening condition with a known effective prehospital intervention: parenteral epinephrine (Citation1–3). Epinephrine administration by paramedics, basic life support (BLS) providers and even the lay public has long been advocated as an important anaphylaxis-related public health strategy (Citation3–6). In 2011, the National Association of EMS [emergency medical services] Physicians (NAEMSP) issued a position statement on the use of epinephrine for out-of-hospital treatment of anaphylaxis, which states, “EMS providers should be allowed to carry and administer epinephrine, in conjunction with strict medical oversight, for the treatment of anaphylaxis in the out-of-hospital setting” (Citation7, p. 544). The statement also identifies education and continuous quality improvement as important components of any epinephrine administration program. The statement does not, however, limit the recommendation to either a specific level of provider or a specific mechanism for epinephrine delivery (Citation7, Citation8).

Epinephrine auto-injectors (EAIs) are one widely marketed mechanism for allowing people with minimal medical training to deliver epinephrine to patients suffering anaphylactic reactions. Historically, some states have allowed both the lay public and BLS EMS providers to administer epinephrine using syringes containing pre-drawn or vial-drawn medication (Citation9, Citation10), but several states that allow BLS epinephrine administration now constrain it to EAI administration. The cost and sometimes limited supply of EAIs, however, limits the ability of some EMS agencies to provide epinephrine for anaphylaxis (Citation11, Citation12). Thus, the NAEMSP Standards and Practice (S&P) committee was charged with reviewing the evidence and revising the organization's position statement to address non-EAI epinephrine administration, specifically by BLS providers.

The new position statement, published online in January 2019 (Citation13), expands on the previous version to specify that NAEMSP believes: (1) “[t]here is some evidence that intramuscular injection of epinephrine drawn up from a vial or ampule by appropriately trained EMS providers is safe” and that (Citation2) “medical directors are the decision-making authority regarding whether and how best to provide epinephrine for anaphylaxis”—both without limitation to specific certification levels.

This literature review and consensus process identifying and describing the extant literature as well as practical and policy issues related to non-EAI administration of epinephrine for anaphylaxis—particularly by BLS providers—was undertaken as part of the process of revising the NAEMSP position statement, and serves as a supplementary resource document—complementing but not replacing prior resource documents (Citation8)—for that position statement.

Methods

Literature Search Strategy

Our search strategy incorporated selected terms associated with emergency medical services, anaphylaxis and epinephrine, tailored as necessary for each database (). We searched three databases: The National Library of Medicine using the Ovid search engine; the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) using the EBSCOhost search engine; and the Academic Complete database using the EBSCOhost search engine. We also searched the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. We searched all available years in each database without restriction (e.g., English language). The searches were executed February 5, 2018 and covered all years included in each database.

Table 1. Search strategies

Title and Abstract Review

All of the identified citations, including the article title and (if available) abstract, were randomly distributed among the eight authors with two authors independently reviewing each title and abstract to determine the paper's relevance to the study question. Authors rated each article as “on-point,” “relevant background/reference,” or “not relevant/exclude.” Reviewers were blinded to each other's appraisal. If the reviewers disagreed on an article's potential relevance, a third blinded author reviewed the title and abstract and provided adjudication. All articles identified as "on-point" were retained for detailed review.

Detailed Article Reviews

We subsequently obtained paper or electronic copies of each retained article and distributed them among the authors, again with two independent reviewers abstracting information from each article. Using a structured data abstraction form, reviewers first determined each article's relevance based on three criteria: (1) non-hospital/out-of-hospital management of anaphylaxis, (2) administration of epinephrine by EMTs or first responders, and (3) use of non-auto-injector epinephrine. After determining an article's relevance, reviewers used the same form to extract numerical data (into a 2 × 2 table when possible), list reported adverse events, and summarize any policy recommendations. Reviewers also referred any additional relevant citations discovered during their review for further evaluation. For this step, an article's information was included if either reviewer determined it was relevant and extracted data, adverse events or policy recommendations.

We developed, and report here, descriptive summaries of each included article. We made no attempt to aggregate data using meta-analytic techniques.

Consensus Building

An initial draft of the revised position statement, along with the descriptive summary of the identified literature, was shared with all members of the NAEMSP S&P committee. Committee members provided feedback on the draft position statement, and identified related practical and policy issues and concerns through interactive email exchanges. The project leader (JWL) moderated these exchanges to encourage presentation of all viewpoints. Although not a true Delphi process, this iterative process contributed to subsequent revisions of the position statement, and provided context presented in the Discussion section below.

Results and Discussion

Literature Review

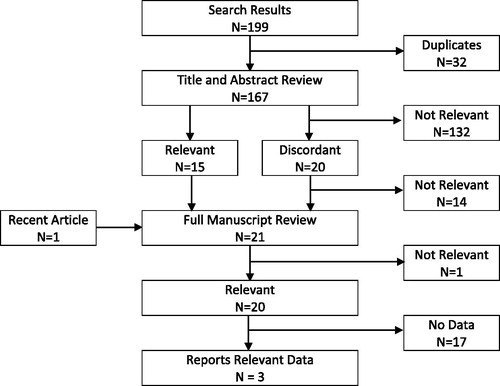

shows the results of the search and review process. There were no relevant systematic reviews in the Cochrane database, but the search identified 199 potentially relevant citations in the remaining databases. After eliminating duplicates, 167 citations underwent title and abstract review. Based on the titles and abstracts, reviewers agreed that 15 citations were clearly relevant, and 132 citations were clearly not relevant; there were 20 citations for which reviewers did not agree (overall agreement = 88%; Kappa = 0.54). After adjudication by a third reviewer, six of these citations were retained. One additional potentially relevant paper was published during the review process. Thus, a total of 21 papers underwent full manuscript review. After full manuscript review, there was complete agreement that 20 of the papers were relevant to prehospital management of anaphylaxis (Kappa = 1.0), and substantial agreement (Kappa = 0.77) that only three of those papers reported data relevant to non-EAI epinephrine administration by BLS providers (see ).

TABLE 2. Inter-rater agreement for full manuscript review

Fortenberry et al. (Citation4) reported a case series of eight anaphylaxis patients who received non-EAI subcutaneous epinephrine administered by EMT park rangers working in Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks, California. All eight cases involved Hymenoptera stings. The park rangers had completed a 2-hour didactic training session, followed by a practical component practicing subcutaneous injection. The epinephrine was provided as 0.3 mL of 1:1,000 epinephrine (0.3 mg) in prefilled syringes. Every patient experienced improvement in clinical symptoms within 2–25 minutes of epinephrine administration, although some patients also received diphenhydramine. One patient experienced near-syncope 15 minutes after epinephrine administration, with a reported heart rate of 100 and a blood pressure of 135/80 mmHg.

Lindbeck et al. (Citation5) retrospectively reviewed 37 instances of EMS administered non-EAI subcutaneous epinephrine for patients with allergic reactions in a rural area of Virginia, including 14 cases where the epinephrine was administered by BLS providers. Most cases (65%) resulted from insect stings, but reactions due to food and medication allergies were also included. The EMS providers had completed a 2-hour initial training session, followed by 1-hour annual refresher courses. The epinephrine was provided as 1 mL of 1:1,000 epinephrine in a prefilled syringe with a “plunger stop system” that allows only 0.3 mL to be administered with a single push (ANA-KIT, Bayer, Spokane, WA, USA). However, 38% of patients received epinephrine drawn up from an ampule; these were presumably patients treated by advanced life support (ALS) personnel, but that is not explicitly clear. Eighty percent of patients had improved symptoms following epinephrine administration, although there were minimal changes in vital signs. No adverse events were reported.

Recently, Latimer et al. (Citation12) reported their experience with 411 patients who received non-EAI intramuscular epinephrine administered by EMTs in King County, Washington. Food and nut allergies accounted for nearly half of the cases, followed by insect stings (17.5%) and medication reactions (16.7%). The EMTs had completed about 2 hours of training on the “Check and Inject” program, which uses a physical checklist to verify that epinephrine is indicated, that the EMT is using the right drug and dosage, that proper injection technique is used, and that follow-up monitoring is performed. The epinephrine was provided in 1 mL vials of 1:1,000 epinephrine along with two 1-mL syringes with 25 g needles. There were 44 cases (10.7%) where EMTs failed to document a clear indication for epinephrine administration on the “Check and Inject” checklist, but physician review of the EMS record determined that epinephrine was clinically indicated in 36 of those cases. Among the 8 cases without a clear indication on the checklist or following physician review, there were no adverse events. Among the remaining cases, there were two instances of cardiac arrest; these were judged to be related to the patients' clinical condition and not related to epinephrine administration. The authors estimate that using drawn-up epinephrine instead of EAIs would provide as much as $335,000 in annual cost savings to the King County EMS system.

Several additional authors advocate for non-EAI epinephrine administration by BLS providers, but do not present data to support their recommendations (Citation5, Citation12, Citation14–17).

Other than the one case of pre-syncope reported by Fortenberry et al. (Citation4), we found no reports of adverse events specifically associated with non-EAI epinephrine administration by BLS providers. However, a literature review by Safdar et al. (Citation18) revealed three reported instances of adverse events associated with prehospital epinephrine for anaphylaxis: (1) a 39-year old with “hypertensive urgency,” congestive heart failure and wheezing who paramedics mistook as having an allergic reaction suffered a subarachnoid hemorrhage after receiving 0.5 mg of subcutaneous epinephrine; (2) a 30-year old with a history of recurrent anaphylaxis suffered a myocardial infarction after self-administering subcutaneous epinephrine; (3) a 27-year old suffered myocardial ischemia—including chest pain, sinus tachycardia and diffuse ST elevation—after accidentally being administered 2mg of epinephrine. Other putative side effects include anxiety, palpitations, headache, nausea, vomiting, pallor and dizziness (Citation19). Importantly, epinephrine administration using EAIs is not immune from these potential adverse events and side effects, and comes with the additional risk of accidental injection (Citation20, Citation21) and failed injection due to device malfunction or inadequate needle length (Citation22–25).

Consensus Process

Twenty-five S&P committee members posted email comments during the consensus process. The comments varied widely, representing perspectives from committee members in urban, suburban, rural, and remote settings, as well as members from the spectrum of struggling to well-resourced systems. The comments are summarized here to reflect the full range of perspectives and concerns for systems and medical directors considering non-EAI epinephrine by BLS personnel.

Generally, the comments could be classified into five main categories as detailed in the following sections.

Is There a Need for BLS Administration of Epinephrine?

Some committee members questioned whether the incidence of true anaphylactic emergencies justifies the opportunity costs associated with implementing epinephrine administration by BLS providers, regardless of delivery method. Beyond the cost of equipment and supplies, scarce education and oversight resources might be better spent on other priorities. This could be particularly true for BLS providers who are integrated into primarily paramedic or other ALS systems where epinephrine for anaphylaxis is already otherwise available. Other committee members noted that much of the United States is served by BLS-only systems without the availability of ALS support or intercept. In those settings, BLS administration of epinephrine for anaphylaxis could be life-saving.

Although not ideal for determining incidence or prevalence of disease on a national level, data from the 2016 NEMSIS Public Release Dataset indicate approximately one in every 200 9-1-1 scene responses attended by a paramedic level agency in 2016 was identified as being for an allergic reaction, and approximately one in ten of those allergic reaction patients received parenteral epinephrine. The incidence of identified allergic reactions was essentially identical for 9-1-1 scene responses by BLS-only agencies, but only one in 35 of those patients received parenteral epinephrine (unpublished data). It is more likely that this disparity represents under-treatment of patients attended by BLS-only agencies, rather than a lower level of true anaphylaxis among patients treated by BLS-only agencies.

Is Skill Expansion the Best Response to What is Primarily a Financial Issue?

The committee members noted that this issue is largely being driven by the spiraling cost of EAIs, and allowed that NAEMSP and other professional bodies might have been unwitting contributors to the problem through their well-intentioned support of policy and regulatory initiatives promoting widespread availability of EAIs. Some committee members strongly advocated for efforts to address EAI pricing. The much-anticipated arrival of generic EAIs is expected to help drive prices down, although it is still unknown whether that will fully alleviate the problem. Enabling medical directors to implement non-EAI epinephrine administration is one strategy—but not the only strategy—for ensuring appropriate care is available for patients with anaphylaxis.

How Well can BLS Providers Master and Retain Non-EAI Injection Skills?

The current National EMS Scope of Practice Model does not include intramuscular injection as a skill for emergency medical responders (EMRs) or EMTs, although they can assist patients with their own autoinjectors. If BLS providers are going to administer non-EAI epinephrine for anaphylaxis, they will require additional education to enable them to recognize anaphylaxis, differentiate it from other similar presentations, and understand the pharmacology of epinephrine. They will also require training in the skill of drawing up a medication and administering an intramuscular injection.

Some committee members raised concerns about the resources required for such additional education and training, and about the whether the frequency of events would be enough to promote skill maintenance. Other committee members noted that some states already allow BLS administration of epinephrine, either by EAI or using drawn up medication, and have education and training standards in place. Non-EAI epinephrine use by BLS providers is also advocated by leaders in Wilderness Medicine (Citation26). The committee members offering anecdotes of success with BLS epinephrine programs acknowledged the absence of published data reporting their experiences.

The committee members agreed that initial and ongoing education and training, coupled with a comprehensive quality improvement program and focused medical oversight, are imperative for systems that elect to implement non-EAI epinephrine administration for anaphylaxis. It was noted that in some rural systems the number of providers who would require training and oversight is small, and that the additional education, training and oversight requirements should not be onerous. In other systems, the numbers of providers and diversity in their backgrounds might make implementation of non-EAI epinephrine impracticable.

Is Non-EAI Epinephrine Administration Safe?

The key concern for all committee members was the safety of non-EAI epinephrine administration, not only by BLS providers but generally. While EAIs are not immune from administration errors (Citation19–25)—including dosing errors associated with their one-size-fits-all approach—it was noted that the outcomes associated with EAI-related administration errors are generally less severe than those associated with non-EAI administration errors (Citation27). Some committee members reported emergency departments and hospitals switching to EAIs for in-hospital use for this reason.

As demonstrated by the literature review, the evidence regarding the safety of BLS administration of non-EAI epinephrine for anaphylaxis—while consistent—is not robust (Citation4, Citation5, Citation12). Only the recent work by Latimer et al. includes enough patients to support any attempt at generalization, but it represents the experience of a single system with the ability to dedicate significant resources to their non-EAI epinephrine initiative (Citation12). While we found no reported evidence of increased risk of harm associated with non-EAI epinephrine for anaphylaxis, we again caution that such programs must incorporate extensive education and training, ongoing quality improvement, and intense medical oversight.

How do we Avoid Unintended Consequences?

The committee members also recognize that previous well-intentioned policy efforts may have had unintended consequences. Specifically, the committee acknowledges concerns about the creeping expansion of scope of practice. NAEMSP endorses the National EMS Scope of Practice Model, which does not include intramuscular injection of drawn up medications as an EMR or EMT level skill. However, the National Scope of Practice Model only defines the minimum competencies for each EMS provider level; it does not create or define a scope of practice ceiling for any provider. Scope of practice should be defined locally by EMS medical directors and system leadership, consistent with state, regional, or local regulatory requirements. The intention of this revision to the NAEMSP position statement on epinephrine for anaphylaxis is to enable EMS medical directors who identify a need in their system to implement non-EAI epinephrine for anaphylaxis; it is not to comprehensively advocate non-EAI epinephrine by all BLS providers in all EMS systems. This position statement is specific to non-EAI epinephrine and should not be interpreted—either positively or negatively—as having any implications for other medications (e.g., glucagon, naloxone, etc.). Finally, the position statement is written in the context of the current medical and regulatory environment, and might require editorial or substantive revision if that environment changes, for example with changes in the National EMS Scope of Practice Model or innovations in anaphylaxis therapy (e.g., epinephrine tablets). Indeed, the statement purposefully refers to dosing “consistent with current clinical guidelines” to allow for changes in the standard of care over time.

Limitations

Although the new position statement (Citation13) addresses epinephrine administration for anaphylaxis, this literature review and consensus process focused on non-autoinjector administration by BLS providers. This was the impetus for the revision, and is the crux of the difference between the new and previous statements. The literature review was not an exhaustive systematic review. For example, while the National Library of Medicine indexing process maps terms like “adrenaline” or “allergic reactions” to “epinephrine” and “hypersensitivity” (respectively), our CINAHL and Academic Complete searches would not have identified articles where those terms appear only as text words. Also, we did not have access to the Embase database. Those limitations might have caused us to miss relevant articles from foreign journals. We also did not search clinicaltrials.gov for relevant trials, although a post-hoc search during the preparation of this report identified no relevant trials. Finally, we only identified three peer-reviewed studies evaluating administration of drawn-up epinephrine by BLS providers. Given the paucity of studies on this topic, further research is clearly indicated.

Conclusion

This article serves as a supplementary resource document—complementing but not replacing prior resource documents (Citation8)—for the new NAEMSP position statement on “Use of epinephrine for out-of-hospital treatment of anaphylaxis” (Citation13). This literature review and consensus process concludes that “[t]here is some evidence that intramuscular injection of epinephrine drawn up from a vial or ampule by appropriately trained EMS providers is safe, facilitates timely treatment of patients, and reduces costs” (Citation13) without limitation to specific certification levels.

References

- Sheikh A, Shehata YA, Brown SG, Simons FE. Adrenaline (epinephrine) for the treatment of anaphylaxis with and without shock. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008(4):CD006312. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006312.pub2.

- Lieberman P, Nicklas RA, Randolph C, Oppenheimer J, Bernstein D, Bernstein J, Ellis A, Golden DB, Greenberger P, Kemp S, et al. Anaphylaxis—a practice parameter update. Ann Alergy Asthma Immunol. 2015;115:341–84. doi:10.1016/j.anai.2015.07.019.

- Kemp SF, Lockey RF, Simons FE. Epinephrine: The drug of choice for anaphylaxis. A statement of the World Allergy Organization. Allergy. 2008;63:1061–70. doi:10.1111/j.1398-9995.2008.01733.x.

- Fortenberry JE, Laine J, Shalit M. Use of epinephrine for anaphylaxis by emergency medical technicians in a wilderness setting. Ann Emerg Med. 1995;25:785–7. doi:10.1016/S0196-0644(95)70208-3.

- Lindbeck GH, Burns DM Rockwell DD. Out-of-hospital provider use of epinephrine for allergic reactions: pilot program. Acad Emerg Med. 1995;2:592–6.

- Cone DC. Subcutaneous epinephrine for out-of-hospital treatment of anaphylaxis. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2002;6:67–8. doi:10.1080/10903120290938823.

- National Association of EMS Physicians. The use of epinephrine for out-of-hospital treatment of anaphylaxis. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2011;15:544.

- Jacobsen RC, Millin MG. The use of epinephrine for out-of-hospital treatment of anaphylaxis: Resource document for the National Association of EMS Physicians position statement. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2011;15:570–6. doi:10.3109/10903127.2011.598619.

- McDougle L, Klein GL, Hoehler FK. Management of hymenoptera sting anaphylaxis: A preventive medicine survey. J Emerg Med. 1995;13:9–13.

- Sicherer SH, Forman JA, Noone SA. Use assessment of self-administered epinephrine among food-allergic children and pediatricians. Pediatrics. 2000;105:359–62.

- Duhig C. Outcry over EpiPen prices hasn't made them lower. New York Times. June 4, 2017. [accessed 2018 Sept 12]. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/06/04/business/angry-about-epipen-prices-executive-dont-care-much.html.

- Latimer AJ, Husain S, Nola J, Doreswamy V, Rea TD, Sayre MR, Eisenber MS. Syringe administration of epinephrine by emergency medical technicians for anaphylaxis. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2018;22:319–25. doi:10.1080/10903127.2017.1392667.

- National Association of EMS Physicians. Use of epinephrine for out-of-hospital treatment of anaphylaxis. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2019: doi:10.1080/10903127.2018.1551453.

- Brasted ID, Ruppel MC. Anaphylaxis and its treatment. EMS World. 2016;45(9):31–7.

- Brasted ID, Dailey MW. Basic life support access to injectable epinephrine across the United States. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2017;21(4): 442–447. doi:10.1080/10903127.2017.1294224.

- Cashin S. Is there a role for prehospital intramuscular adrenaline in anaphylaxis? Austr J Emerg Care. 1996;3(1):11–5.

- Goldhaber SZ. Administration of epinephrine by emergency medical technicians. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:822. doi:10.1056/NEJM200003163421115.

- Safdar B, Cone DC, Pharm K-T C. Subcutaneous epinephrine in the prehospital setting. Prehosp Emerg Care 2001;5(2):200–7. doi:10.1080/10903120190940137.

- Cunningham SR. EMT-basics and epinephrine. Emergency (01625942). 1995;27(6):18–25.

- Simons FE, Lieberman PL, Read EJ, Edwards ES. Hazards of unintentional injection of epinephrine from autoinjectors: a systematic review. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2009;102:282–7. doi:10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60332-8.

- Simons FE, Edwards ES, Read EJ, Clark S, Liebelt EL. Voluntarily reported unintentional injections from epinephrine auto-injectors. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125:419–23. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2009.10.056.

- Stecher D, Bulloch B, Sales J, Schaefer C, Keahey L. Epinephrine auto-injectors: is needle length adequate for delivery of epinephrine intramuscularly? Pediatrics. 2009;124:65–70. doi:10.1542/peds.2008-3388.

- Bhalla MC, Gable BD, Frey JA, Reichenbach MR, Wilber ST. Predictors of epinephrine autoinjector needle length inadequacy. Am J Emerg Med. 2013;31:1671–6. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2013.09.001.

- Song TT, Lieberman P. Epinephrine auto-injector needle length: what is the ideal length? Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;16:361–5. doi:10.1097/ACI.0000000000000283.

- Tsai G, Kim L, Nevis IF, Dominic A, Potts R, Chiu J, Kim HL. Auto-injector needle length may be inadequate to deliver epinephrine intramuscularly in women with confirmed food allergy. Allergy, Asthma, Clin Immunol. 2014;10(1):39. doi:10.1186/1710-1492-10-39.

- Millin MG, Johnson DE, Schimelpfenig T, Conover K, Sholl M, Busko J, Alter R, Smith W, Symonds J, Taillac P, Hawkins SC. Medical oversight, educational core content, and proposed scopes of practice of wilderness EMS providers: A joint project developed by wilderness EMS educators, medical directors, and regulators using a Delphi approach. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2017;21:673–81. doi:10.1080/10903127.2017.1335815.

- Chime NO, Riese VG, Scherzer DJ, Perretta JS, McNamara L, Rosen MA, Hunt EA. Epinephrine auto-injector versus drawn up epinephrine for anaphylaxis management: A scoping review. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2017;18:764–9. doi:10.1097/PCC.0000000000001197.