Abstract

Objective: Firefighter first responders and other emergency medical services (EMS) personnel have been among the highest risk healthcare workers for illness during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. We sought to determine the rate of seropositivity for SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibodies and of acute asymptomatic infection among firefighter first responders in a single county with early exposure in the pandemic. Methods: We conducted a cross-sectional study of clinically active firefighters cross-trained as paramedics or EMTs in the fire departments of Santa Clara County, California. Firefighters without current symptoms were tested between June and August 2020. Our primary outcomes were rates of SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibody seropositivity and SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR swab positivity for acute infection. We report cumulative incidence, participant characteristics with frequencies and proportions, and proportion positive and associated relative risk (with 95% confidence intervals). Results: We enrolled 983 out of 1339 eligible participants (response rate: 73.4%). Twenty-five participants (2.54%, 95% CI 1.65-3.73) tested positive for IgG antibodies and 9 (0.92%, 95% CI 0.42-1.73) tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 by RT-PCR. Our cumulative incidence, inclusive of self-reported prior positive PCR tests, was 34 (3.46%, 95% CI 2.41-4.80). Conclusion: In a county with one of the earliest outbreaks in the United States, the seroprevalence among firefighter first responders was lower than that reported by other studies of frontline health care workers, while the cumulative incidence remained higher than that seen in the surrounding community.

Key words:

Introduction

The first known death in the United States due to SARS-CoV-2 occurred on February 6, 2020 in Santa Clara County, California (Citation1). By early March, a firefighter from the station that cared for that individual was hospitalized with SARS-CoV-2 (Citation2). He had been on shift in the interim and attended a course with personnel from other fire departments. Rapidly, more than a dozen firefighters became symptomatic and tested positive, while 80 others were quarantined, with a significant impact on the workforce.

Firefighter first responders and other emergency medical services (EMS) personnel are among the highest risk healthcare workers for illness during outbreaks. In New York City, 34.5% of firefighters and 40.7% of EMS responders had taken medical leave as of July 2020 for suspected or confirmed SARS-CoV-2 (Citation3). Workforce reduction was a particular threat to fire departments along the West and Gulf Coasts in 2020 because of concurrent natural disasters requiring emergency personnel from across the country.

Several issues increase the SARS-CoV-2 infection risk to firefighters and EMS. On shift, firefighters must live in close quarters, often sharing common sleep rooms and communal meals. On scene, the variable presentation of patients with SARS-CoV-2 and limited patient information complicates clinical gestalt. Additionally, a culture among health care workers of working even when they feel ill (Citation4–6) coupled with a lack of available testing for SARS-CoV-2 early in the pandemic, meant that many firefighters and EMS personnel went untested.

These factors combined with the early impact of the pandemic on Santa Clara County created a significantly higher risk to its firefighter and EMS population. In this study, we aimed to determine the seropositivity of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies and asymptomatic acute infection rates among firefighter first responders in the county.

Methods

Study Design

We conducted a cross-sectional study of firefighters cross-trained as paramedics or emergency medical technicians (EMTs) in Santa Clara County, California, to determine the rate of SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibody seropositivity and SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR swab positivity. The Stanford Institutional Review Board approved this study (#56572). We obtained written informed consent from all participants.

Setting

Santa Clara County is one of the top 20 most populous counties in the United States with approximately 1.9 million residents (Citation7, Citation8). By the completion of the study, (August 31st, 2020) there was a cumulative total of 18,021 COVID-19 cases and 285 COVID-19 related deaths (Citation9, Citation10).

All fire departments in the county require yearly N95 fit testing and training. Prompted by early evidence of community transmission in California, personal protective equipment for both droplet and contact precautions (PPE: gloves, eye protection, gowns, and N95 masks) became mandatory for all county EMS personnel when responding to calls of patients with fever or respiratory symptoms on March 4, 2020. If tolerated by the patient, surgical or procedure masks were placed on patients with fever or respiratory symptoms. On April 2, the Santa Clara County EMS Agency issued an administrative order for the judicious use of aerosol generating procedures: early transition to laryngeal mask airway (LMA) in cardiac arrest, nebulized albuterol and/or CPAP reserved only for pulse oximetry less than 94%, whether on oxygen or not. Changes were also made within fire stations, including temperature screening, prohibition of duty uniforms in living quarters, and requirements to disinfect surfaces and wear masks while in the station. However, these changes were variably implemented throughout the county in March and April.

Selection of Participants and Outcomes

We included participants from ten of the county’s eleven fire departments. We excluded the single fire department staffed by cross-trained public safety officers who do not work as paramedics. All sworn firefighters clinically active since November 2019 were eligible to participate. We recruited participants through emails sent via fire department and union leadership and obtained written informed consent to ensure that study participation was voluntary. We conducted testing at local fire stations from June to August 2020, allowing crews to participate while on duty and minimizing impact on system resources. Participants completed a survey including demographics, prior exposures, symptoms, use of PPE, and results of prior PCR testing. Within demographics we collected information on participant’s primary county of residence as anecdotally we understood some participants did not live and work in the same county. To better understand exposures, we collected data on work-related exposures (e.g. bag valve mask ventilation, intubation, confirmed patient or coworker COVID-19 exposure), changes to living quarter policies (e.g. mask wearing, temperature screening), travel, and community COVID-19 exposures.

Outcomes

Our study’s primary outcomes were SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibody seropositivity and SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR swab positivity. In order to optimize diagnostic accuracy, our clinical lab’s antibody testing protocols evolved during the study using three validated testing platforms: a laboratory-developed enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) test for IgG to the receptor binding domain of the spike protein (Stanford)(Citation11); a high-throughput CMIA test for IgG to the nucleocapsid protein (Abbott Architect); and an ELISA for IgG to the S1 domain of the spike protein (EuroImmun). We also tested participants for active SARS-CoV-2 infection with a sample collected via nasopharyngeal swab using a laboratory-developed RT-PCR test (Stanford) with FDA emergency use authorization. All tests were performed at the Stanford Health Care Clinical Laboratories.

Data Analysis

We report a cumulative incidence which includes participants positive for IgG antibodies, positive on the study’s RT-PCR, or previously PCR positive by self-report. We report participant characteristics with frequencies and proportions, as well as proportion positive and the associated relative risk (with exact 95% confidence intervals). We used SAS Enterprise Guide version 8.2 for our data analysis.

Results

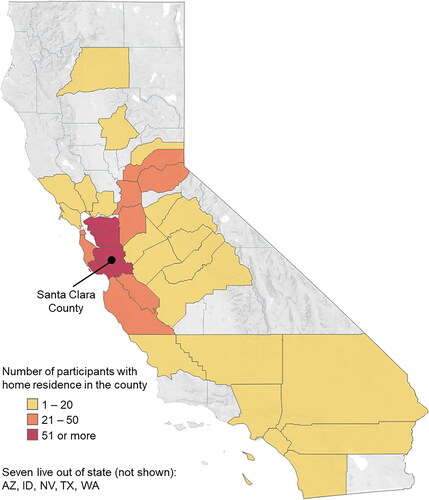

We enrolled 983 participants out of 1339 eligible, for a response rate of 73.4%. Most participants were men 942 (95.8%) and lived outside the county (68.3%). 60.4% of participants were white non-Hispanic (). When not on duty, firefighters resided throughout California, including more than half of all counties (33/58, 56.9%), with 7 (0.7%) returning to homes out of state ().

Table 1. Characteristics of study participants and proportion with IgG antibodies or SARS-CoV-2

Twenty-five participants (2.54%, 95% CI 1.65-3.73) tested positive for IgG antibodies and 9 (0.92%, 95% CI 0.42-1.73) tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 by RT-PCR. Of the 9 positive for SARS-CoV-2 by RT-PCR, 3 were positive for IgG antibodies. Of the 952 participants who were negative on both IgG and RT-PCR testing, 3 reported a prior positive PCR test. This resulted in a cumulative incidence of 34 out of 983, or 3.46% (95% CI 2.41-4.80).

Over the 60-day study period we saw no trend in testing positivity rate. The 9 participants tested RT-PCR positive at days 20, 21, 22, 24(2), 26, 43, and 51(2). The 32 participants who were either RT-PCR positive or IgG antibody positive, were positive at days 3, 20(2), 21(2), 22(5), 24(2), 26, 29(3), 30(2), 31, 35, 38, 42(3), 43(2), 51(6). Further, most of the reported prior positive PCR tests occurred greater than 2 months before our study period (83.3% (10/12)).

Of the 25 participants who were IgG antibody positive, 10 participants (40.0%) were asymptomatic since February 1, 2020. This is compared to 651 (68.0%) asymptomatic participants in the IgG negative group (P = 0.005). Of the 9 participants who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 by RT-PCR, only 1 (11.1%) had any symptoms within the preceding two weeks.

Hispanic firefighters faced a higher relative risk of having IgG antibodies compared to white non-Hispanic firefighters (RR = 3.48, 95% CI 1.36-8.90) (). Participants who thought they “definitely” had SARS-CoV-2 previously and were not known to be previously SARS-CoV-2 positive, had an 8.80 relative risk (95% CI 1.80-43.07) of being IgG positive. Of note, this represented only two participants. Sharing working quarters with someone the participant believed to be SARS-CoV-2 positive increased the relative risk of having IgG antibodies (RR = 3.37, 95% CI 1.53-7.41) and active SARS-CoV-2 infection (RR = 4.49, 95% CI 1.13-17.83) (). Exposure at work to a confirmed SARS-CoV-2 positive patient’s respiratory secretions also increased the relative risk of being IgG positive (RR = 2.85, 95% CI 1.32-6.16). While multiple community exposures carried a higher relative risk, this finding was not statistically significant (RR = 3.05, 95% CI 0.94-9.89).

Table 2. Workplace exposures of Study Participants and Proportion with IgG Antibodies or SARS-CoV-2

Discussion

Our study estimates a 2.54% seropositivity rate for IgG antibodies to SARS-CoV-2, and 0.92% positivity rate of SARS-CoV-2 acute asymptomatic infection in firefighter first responders. Even in a county with one of the earliest outbreaks, our seroprevalence was low compared to the 5.4% seropositivity in EMS first responders in Cleveland (Citation12), 8.9% IgG seropositivity among firefighters in South Florida (Citation13), or 6.0% IgG seropositivity among health care workers in a multistate hospital network (Citation14). However, our IgG seropositivity is higher than the 1.5% seropositivity seen among Arizona first responders (Citation15). The cumulative incidence of 3.46% was much higher than that seen in the surrounding community of 0.93% (Citation16). Over the course of the study, the test positivity in the community increased from 2.4% to 3.3%, with a late July peak of 4.6% (Citation16). However, we saw no trend in our study’s test positivity.

The county’s early mandatory PPE order may have helped protect EMS. Criteria for PPE use expanded beyond travel history to include all patients with fever or respiratory symptoms. In addition, aerosolizing procedures and the number of personnel in direct contact with the patient were limited. Even with these changes, only 67.8% of respondents reported having worn full PPE during an exposure to a patient later confirmed to have COVID-19. This may be indicative of the broad range of symptoms COVID-19 may present with beyond fever or respiratory symptoms.

Further, work and living condition changes, such as masks and cleaning protocols, may have prevented living in a fire station from being a recurrent superspreading event. The fire departments in the study all implemented various levels of changes in living quarters early in the pandemic with increased attention on protocol adherence as cases rose over late summer. In our study, most of the firefighters lived outside of the county. Consequently, there was significant travel occurring weekly to monthly between this county, other regions of California, and across five other states. Efforts required to fight wildfires create similar conditions of increased exposure risk and travel. Both fire camps where firefighters stay and incident command where activities are coordinated present scenarios where firefighters must work together with little ability to socially distance (Citation17). Lessons learned from the pandemic should be evaluated for their utility in these situations as well.

Symptoms of COVID-19 are both insensitive and nonspecific. Among participants with evidence of prior infection, 40% had no symptoms during the pandemic, while many study participants who were seronegative reported symptoms consistent with COVID-19. Further, notification of a confirmed positive exposure, whether patient or colleague, and non-work-related positive exposures, did not demonstrate statistically significant increases in risk. One reason may be a concern expressed by participants: they were worried that they were not notified of patients later found to have SARS-CoV-2. Nationally, real-time linking of hospital data to prehospital emergency care data is an on-going challenge and contact tracing efforts remain understaffed. Consequently, the reported confirmed positive exposure notifications may well underestimate actual confirmed positive exposures, and overall actual positive exposures.

Limitations

These findings have two primary limitations. First, specimens were collected at one point in time. IgG accuracy would have been improved by two rounds of specimen collection. Further, declining antibody levels in the months following documented infection suggest that some previously seropositive individuals may have become seronegative (Citation18). However, our large sample size limits this bias and a recent study using serial antibody tests in an EMS population found no new positives at retesting after three weeks (Citation12). Second, there is no adjusted prevalence based on test characteristics. The sensitivity of serological tests for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in asymptomatic individuals remains a topic of active investigation and given the high performance of the tests used in this study, this limitation can be considered minor (Citation19).

Conclusion

Given that prehospital EMS personnel, including firefighters, serve at the frontline of any disease outbreak, it is important to better understand their risk of infection. In our cross-sectional study of 983 firefighter first responders in Santa Clara County, 2.54% and 0.92% of participants tested positive for IgG antibodies and acute SARS-CoV-2 respectively, with a cumulative incidence of 3.46%. For a US county that experienced an early outbreak, firefighter first responders had a relatively low seroprevalence compared to other published rates for health care workers. Despite the virus’s early arrival and limited availability of testing, early changes to care protocols, including broadened criteria for PPE use, and living quarter modifications, may have mitigated the spread of infection in this high-risk population. Future research should investigate the efficacy of such mitigation strategies with larger sample sizes to advance pandemic preparedness.

References

- Jorden MA, Rudman SL, Villarino E, Hoferka S, Patel MT, Bemis K, Simmons CR, Jespersen M, Johnson JI, Mytty E, CDC COVID-19 Response Team, et al. Evidence for limited early spread of COVID-19 within the United States, January-February 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(22):680–4. doi:https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6922e1.

- Winton R. COVID-19 outbreak in San Jose fire department may be early sign of danger for first responders [Internet]. Los Angeles Times. 2020. [cited 2020 Sep 27]. Available from: https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2020-03-18/coronavirus-outbreak-san-jose-fire-department-first-responders.

- Prezant DJ, Zeig-Owens R, Schwartz T, Liu Y, Hurwitz K, Beecher S, Weiden MD. Medical leave associated with COVID-19 among emergency medical system responders and firefighters in New York City. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(7):e2016094. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.16094.

- Chiu S, Black CL, Yue X, Greby SM, Laney AS, Campbell AP, Perio MA. Working with influenza-like illness: Presenteeism among US health care personnel during the 2014-2015 influenza season. Am J Infect Control. 2017;45(11):1254–8. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2017.04.008.

- Rebmann T, Charney RL, Loux TM, Turner JA, Abbyad YS, Silvestros M. Emergency medical services personnel’s pandemic influenza training received and willingness to work during a future pandemic. null. 2020;24(5):601–9. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10903127.2019.1701158.

- Barnett DJ, Levine R, Thompson CB, Wijetunge GU, Oliver AL, Bentley MA, Neubert PD, Pirrallo RG, Links JM, Balicer RD. Gauging U.S. emergency medical services workers' willingness to respond to pandemic influenza using a threat- and efficacy-based assessment framework. PLOS One. 2010;5(3):e9856. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0009856.

- Quick Facts Santa Clara County, California; California [Internet]. United States Census Bureau. Available from: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/santaclaracountycalifornia,CA/PST045219.

- US County Populations. 2021. [Internet]. World Population Review. Available from: https://worldpopulationreview.com/us-counties.

- Count of deaths with COVID-19 by date [Internet]. County of Santa Clara Open Data Portal. 2020. Available from: https://data.sccgov.org/COVID-19/COVID-19-case-counts-by-date/6cnm-gchg.

- COVID-19 case counts by date [Internet]. County of Santa Clara Open Data Portal. 2020. Available from: https://data.sccgov.org/COVID-19/COVID-19-case-counts-by-date/6cnm-gchg.

- Röltgen K, Wirz OF, Stevens BA, Powell AE, Hogan CA, Najeeb J, Hunter Sahoo MK, Huang C, Yamamoto F, Manalac J, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Antibody Responses Correlate with Resolution of RNAemia But Are Short-Lived in Patients with Mild Illness [Internet]. Infectious Diseases (except HIV/AIDS); 2020. [cited 2020 Sep 26]. Available from: doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.15.20175794.

- Tarabichi Y, Watts B, Collins T, Margolius D, Avery A, Gunzler D, Perzynski A. SARS-CoV-2 infection among serially tested emergency medical services workers. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2021;25(1):39–45. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10903127.2020.1831668.

- Caban-Martinez AJ, Schaefer-Solle N, Santiago K, Louzado-Feliciano P, Brotons A, Gonzalez M, Issenberg B, Kobetz E. Epidemiology of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies among firefighters/paramedics of a US fire department: a cross-sectional study. Occup Environ Med. 2020;77(12):857–61. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/oemed-2020-106676.

- Self WH, Tenforde MW, Stubblefield WB, Feldstein LR, Steingrub JS, Shapiro NI, Ginde AA, Prekker ME, Brown SM, Peltan ID, Gong MN, Aboodi MS, et al. COVID-19 response team, IVY Network. Seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 among frontline health care personnel in a multistate hospital network — 13 academic medical centers, April–June 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep [Internet]. 2020;69:1221–1226. [cited 2020 Sep 23]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/69/wr/mm6935e2.htm.

- Shukla V, Lau CSM, Towns M, Mayer J, Kalkbrenner K, Beuerlein S, Prichard P. COVID-19 exposure among first responders in Arizona. J Occup Environ Med [Internet]. 2020. [cited 2020 Oct 15]; Publish Ahead of Print. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/joem/Abstract/9000/COVID_19_Exposure_among_First_Responders_in.98082.aspx.

- Santa Clara County, California Coronavirus Cases and Deaths [Internet]. USAFacts.org. 2020. [cited 2020 Sep 21]. Available from: https://usafacts.org/visualizations/coronavirus-covid-19-spread-map/state/california/county/santa-clara-county.

- Thompson MP, Bayham J, Belval E. Potential COVID-19 outbreak in fire camp: modeling scenarios and interventions. Fire. 2020;3(3):38. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/fire3030038.

- Ibarrondo FJ, Fulcher JA, Goodman-Meza D, Elliott J, Hofmann C, Hausner MA, Ferbas KG, Tobin NH, Aldrovandi GM, Yang OO . Rapid decay of Anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in persons with mild Covid-19 . N Engl J Med. 2020;383(11):1085–7. doi:https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc2025179.

- Flower B, Atchison C. SARS-CoV-2 antibody seroprevalence in patients receiving dialysis in the USA. The Lancet. 2020;396(10259):1308–9. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32006-7.