Abstract

In the prehospital setting, EMS clinicians are challenged by the need to assess and treat patients who are clinically undifferentiated with a large constellation of possible medical problems. In addition to possessing a large and diverse set of knowledge, skills, and abilities, EMS clinicians must integrate a plethora of environmental, patient, and event specific cues in their clinical decision-making processes. To date, there is no theoretical framework to capture the complex process that characterizes the prehospital experience from dispatch to handoff, the interface between cues and on-scene information and assessments, while incorporating the importance of leadership and communication. To fill this gap, we propose a theoretical framework for clinical judgment in the prehospital setting that builds upon previously defined methodologies and applies them to the clinical practice of EMS clinicians throughout the EMS experience.

Introduction

EMS clinicians are challenged by the need to assess and treat patients who are clinically undifferentiated with a large constellation of possible medical problems, ranging from trivial to life-threatening (Citation1). To address this, they are required to command a large and diverse set of knowledge, skills, and abilities (KSAs) (Citation2). As in other medical fields, much of the decision-making process is driven by the extensive conscious and subconscious information captured by the clinician throughout the EMS experience (Citation3, Citation4), including diverse cues from environmental, patient, and event-specific sources. The cues are unique and specific to the setting and, in the case of prehospital care, make clinical decision-making increasingly complex as EMS clinicians must integrate information from an inherently dynamic environment.

There is no existing theoretical framework that captures the entirety of the prehospital experience (from dispatch to handoff), the interface between cues and on-scene information and assessments, and the importance of clinician leadership and communication. This type of framework may be important to enhance EMS initial and continuing education, clinician assessment, and the development of clinical tools to support decision-making. To fill this gap, we propose a theoretical framework for clinical judgment in the prehospital setting that leverages previously defined methodology and applies these theories to the clinical practice of EMS.

Defining Clinical Judgment

Over the past two decades, numerous studies have been devoted to defining and operationalizing the higher-order construct of clinical judgment. A higher-order construct is an abstract cognitive concept that exists independent of the lower-order constructs, subsumed under it, and which predicts performance on those lower-order constructs. Higher-order constructs are useful in identifying learning domains and objectives, as well as in informing the pedagogical approaches to enhancing knowledge and skills that characterize the lower-order constructs, as well as the complex processes that connect them within a lower-order construct and with the higher-order one. Examples of higher-order constructs include complex thinking in mathematics (Citation5), teachers’ understanding of fraction arithmetic (Citation6), high school students’ understanding of an Advance Placement course content (Citation7), or demand planning activities performed in supply chains (Citation8). A large focus of the work in this area has been on conceptualizing and assessing the construct of clinical judgment in nursing (Citation4, Citation9–11).

Terms such as “clinical reasoning,” “problem solving,” “critical thinking,” and “decision making” have often been used interchangeably with “clinical judgment,” even though in fact they represent different lower-order aspects of the higher-order clinical judgment construct. For example, Tanner differentiated between clinical reasoning defined as the process a clinician follows to make a judgment and clinical judgment defined as the conclusion concerning a patient’s condition, care, and interventions based on the patient’s response (Citation11). Victor-Chmil (Citation12) differentiated between critical thinking, clinical reasoning, and clinical nursing judgment, and concluded that clinical judgment is a more complex construct that requires “the ability to analyze empirical information in relation to both the specific situation and the aesthetic and reflective aspects of the nurse and the environment of practice.” Nonetheless, he saw the ability to analyze (think critically), the ability to apply KSAs (clinically reason), and the ability to act (clinically judge) as three interconnected but separate pieces of the puzzle. More recently, Betts et al. (Citation4) emphasized the higher-order nature of clinical judgment, and that it represents a combination of “medical knowledge, skills, decision making, and critical thinking.” In this conceptualization, clinical judgment is seen as the outcome of the critical thinking and decision-making processes, while considering different individual (e.g., nurse’s KSAs, personal characteristics, prior experience) and environmental (patient observations, medical records, resources, time pressure) factors.

Given the complex and multi-layered nature of the clinical judgment construct, it is important to clearly define it. Based on this prior work, we use the following definitions for this proposed framework: “Clinical reasoning” is defined as a thought process a clinician uses to evaluate a problem. The conclusion of this thought process, or the choice made, is “clinical decision-making.” Finally, the overall process encompassing both clinical reasoning and clinical decision-making is represented by “clinical judgment.”

Framework for Clinical Judgment in EMS

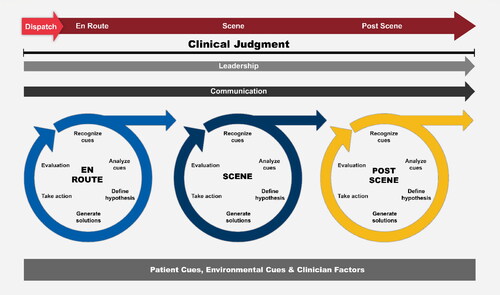

Using this revised definition of clinical judgment and the encompassed pieces of clinical reasoning and decision making, a clear theoretical framework for clinical judgment in the EMS environment can be developed. First, the cognitive process an EMS clinician experiences when encountering new information used to make an actionable decision must be defined. In practice, these steps may not be consciously recognized, but they are important in understanding how information is processed to reach decisions, especially in varied and complex situations. This process information cycle includes recognizing cues, analyzing those cues, defining a hypothesis from the information gathered, generating a solution to the defined problem, taking action to solve the clinical problem, and finally evaluating the outcome of the action (). Notably, this process-information cycle is continuously being repeated as new information becomes available that may require recognizing new cues, re-analyzing the situation, defining new hypotheses, generating new solutions, implementing them, and evaluating their effects.

One critical concept in this framework is the role of identifying cues in the EMS environment. Environmental and patient cues are the contextual factors that drive an EMS clinician’s information processing (). Additionally, as these cues are integrated into the process-information cycle, the EMS clinician’s individual traits also influence their information processing. Clinician-specific factors such as personal characteristics (e.g., gender, race, ethnicity, cultural background), knowledge, skills, and abilities will influence the cues they recognize, how they are analyzed, the hypotheses that are defined, the solutions generated, the actions taken, and the evaluation of the effects generated by actions taken. These clinician-specific impressions are potential drivers for social disparities in care and are critical to the larger clinical judgment framework (Citation34).

As the EMS clinician moves from one setting to the next throughout the EMS experience (e.g., from dispatch to response and to the scene), they also continuously reevaluate and proceed through a series of process-information cycles. Since the evaluation step of an earlier cycle generates new information that requires reassessment, the cycle is continually fed by input from the EMS clinician’s perceptions and experiences, forming a new cycle that generates a continuous loop.

These pieces form the backbone of the new framework for clinical judgment in EMS. This theoretical framework captures the complex environment in which EMS clinicians operate, the various cues that they must respond to, and the continuous loops of information processing required to make clinical judgments during events. Furthermore, this framework allows for the addition of other elements that are noted to be important for EMS clinicians to possess. As an example, in previous work, communication and leadership on an EMS response have been found to be important aspects for effective and safe patient care, and thus are important attributes for an EMS clinician to command (Citation2, Citation13–16). Since communication and leadership can exist as independent constructs but inform the clinical judgment process in the prehospital setting, they are subsumed underneath clinical judgment in the proposed framework.

Discussion

In this article we propose a theoretical framework for clinical judgment in EMS that can guide EMS clinicians’ initial and continuing education, assist with assessment of their KSAs, and support the development of clinical tools to enhance their clinical judgment. Although tailored for the EMS environment, an important aspect of this framework is that it is not exclusive to emergency situations, and it is applicable to the full array of existing and evolving EMS environments. Previously, only one prehospital evaluation identified three main themes to improve clinical reasoning: keeping a holistic view of the patient, being open minded, and improving through feedback (Citation20). Additionally, the endpoint of clinical judgment (i.e., decision-making) has been assessed, but the process itself has not been defined or evaluated (Citation17–19). These prior studies provide a basis of understanding concepts to improve clinical judgment, but a larger framework of the construct is necessary. The framework proposed here encompasses these concepts and extends them by defining the process of clinical judgment for EMS clinicians.

This theoretical framework leverages models proposed in the literature for other medical fields that have been extensively evaluated and validated (Citation3, Citation4, Citation21, Citation22). However, these paradigms have not been tested in the EMS setting. Important next steps will need to include continued subject matter expert feedback on this proposed framework and how it integrates other constructs (e.g., communication and leadership), as well as iterative simulated EMS clinician assessments to better understand the process-information cycle and how clinical judgments are made. As an example, one approach could be to assess this framework in the context of enhancing clinical judgment around comprehensive airway management (Citation23).

Several important issues still remain. First, clinical judgment varies by the experience of the clinician. Less experienced clinicians often rely on analytic thinking to make decisions, whereas proficient and expert clinicians tend to use more efficient, global, and intuitive processing that relies on pattern recognition (Citation24–26). At these advanced levels, thinking is based on a deep understanding of the situation that is grounded in prior experience and reflection, and often only requires resorting to analytic thinking in unfamiliar or unusual situations (Citation25, Citation27). This enhanced ability at the proficient and expert levels permits rapid, intuitive, accurate decision-making. In the future, the effect of clinician experience and how it affects the process-information cycle will need to be evaluated.

Second, decision tools such as screening strategies that identify time-critical diagnoses and early warning scores that predict patient severity and likelihood to deteriorate are increasingly being used and studied in EMS (Citation28–30). Based on the proposed framework, the use of screening tools may support the process-information cycles and decrease cognitive load. Further evaluation of the effect of screening tools and information processing may be critical in enhancing the development of other tools to improve clinical judgment.

Third, is the importance of continued feedback to enhance clinical judgment for EMS clinicians (Citation31, Citation32). Though occurring outside of this framework, feedback is important in the development of EMS clinicians and allows for fundamental improvement in a clinician performance (Citation33). This may lead to possibly more accurate and efficient process-information cycles resulting in improved clinical judgment. Thus, the feedback given to EMS clinicians is proximal to this theoretical framework, which is directed at a specific clinical event in the EMS experience.

Fourth, another important area where this framework may have significant potential is closing the gap in disparities of medical care provision. A challenge in training clinicians is to confirm that patient cues are recognized and appropriately interpreted (Citation34). The causes for missing these cues may be multifactorial, including both implicit bias and explicit bias (Citation35). These missed cues may lead to disparities in care and misunderstandings between patients and clinicians. In a training environment, this framework may allow for the development of structured patient presentations with predefined sets of cues for clinicians to recognize their personal biases as related to their clinical judgment (Citation36). Since the process-information cycles are affected directly by clinician-related factors (e.g., age, gender, race, ethnicity), their responses in these training situations has the potential to assist in closing this gap.

Finally, prior to its adoption, another important step will be for national EMS leadership organizations such as the National Registry of Emergency Medical Technicians, the National Association of EMS Educators, and the National Association of EMS Physicians to rigorously assess the proposed theoretical framework, and to support evaluations to refine the framework for initial education, assessment, and continued competency. This will provide validity evidence for the framework in the EMS setting.

Conclusion

This proposed theoretical framework defines clinical judgment in EMS as it encompasses the initial thought process (i.e., clinical reasoning) that allows the EMS clinician to come to a conclusion (i.e., clinical decision-making). Further, the proposed framework captures the process that brings together the prehospital experience from dispatch to handoff, the interface between cues and information processing, and other important constructs of EMS care (e.g., leadership and communication) that inform clinical judgment. If this new framework is validated and widely adopted, it could assist in the continued evaluation and understanding of the complicated thought processes that drive clinical care in EMS.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- National Association of State EMS Officials. National EMS Scope of Practice Model 2019 (Report No. DOT HS 812-666) Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration; 2019. [cited 2021 February 2nd]. Available from: https://www.ems.gov/pdf/National_EMS_Scope_of_Practice_Model_2019.pdf.

- Panchal AR, Rivard MK, Cash RE, Corley JP, Jr., Jean-Baptiste M, Chrzan K, Gugiu MR. Methods and implementation of the 2019 EMS practice analysis. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2022;26(2):212–222. doi:10.1080/10903127.2020.1856985.

- Dickison P, Haerling KA, Lasater K. Integrating the national council of state boards of nursing clinical judgment model into nursing educational frameworks. J Nurs Educ. 2019;58(2):72–8. doi:10.3928/01484834-20190122-03.

- Betts J, Muntean W, Kim D, Jorian N, Dickison P. Building a method for writing clinical judgment items for entry-level nursing exams. J Applied Testing Technol 2019;20(S2):21–36.

- Graf EA, Arieli-Attali M. Designing and developing assessments of complex thinking in mathematics for the middle grades. Theory Practice. 2015;54(3):195–202. doi:10.1080/00405841.2015.1044365.

- Bradshaw L, Izsák A, Templin J, Jacobson E. Diagnosing teacher's understanding of rational numbers: building a multidimensional test within the diagnostic classification framework. Educ Measure Issues Practice. 2014;33(1):2–14. doi:10.1111/emip.12020.

- Huff K, Steinberg L, Matts T. The promises and challenges of implementing evidence-centered design in large-scale assessment. Applied Measure Educ. 2010;23(4):310–24. doi:10.1080/08957347.2010.510956.

- Swierczek A. Investigating the role of demand plannig as a higher-order construct in mitigating distruptions in the European supply chains. IJLM. 2020;31(3):665– 96. doi:10.1108/IJLM-08-2019-0218.

- Muntean WJ. Nursing clinical decision-making: aliterature review. 2012. Available from: https://www.ncsbn.org/Nursing_Clinical_Decision_Making_A_Literature_Review.htm.

- Dickison P, Luo X, Kim D, Woo A, Muntean W, Bergstrom B. Assessing higher-order cognitive constructs by using an information-processing framework. J Applied Testing Technol. 2016;17(1):1–19.

- Tanner CA. Thinking like a nurse: a research-based model of clinical judgment in nursing. JNE. 2006;45(6):204–11.

- Victor-Chmil J. Critical thinking versus clinical reasoning versus clinical judgment: differential diagnosis. Nurse Educ. 2013;38(1):34–6. doi:10.1097/NNE.0b013e318276dfbe.

- Gugiu MR, Cash R, Rivard M, Cotto J, Crowe RP, Panchal AR. Development and validation of content domains for paramedic prehospital performance assessment: a focus group and delphi method approach. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2021;25(2):196–204. Epub 20200501. doi:10.1080/10903127.2020.1750743.

- Sumner BD, Grimsley EA, Cochrane NH, Keane RR, Sandler AB, Mullan PC, O'Connell KJ. Videographic assessment of the quality of EMS to ED handoff communication during pediatric resuscitations. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2019;23(1):15–21. Epub 20180830. doi:10.1080/10903127.2018.1481475.

- Crowe RP, Cash RE, Christgen A, Hilmas T, Varner L, Vogelsmeier A, Gilmore WS, Panchal AR. Psychometric analysis of a survey on patient safety culture-based tool for emergency medical services. J Patient Saf. 2021;17(8):e1320–e1326. doi:10.1097/PTS.0000000000000504.

- Crowe RP, Wagoner RL, Rodriguez SA, Bentley MA, Page D. Defining components of team leadership and membership in prehospital emergency medical services. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2017;21(5):645–51. Epub 20170502. doi:10.1080/10903127.2017.1315200.

- Mackenzie CF, Gao C, Hu PF, Anazodo A, Chen H, Dinardo T, Imle PC, Hartsky L, Stephens C, Menaker J, et al. Comparison of decision-assist and clinical judgment of experts for prediction of lifesaving interventions. Shock. 2015;43(3):238–43. PubMed PMID: 25394243. doi:10.1097/SHK.0000000000000288.

- Wallgren UM, Castren M, Svensson AE, Kurland L. Identification of adult septic patients in the prehospital setting: a comparison of two screening tools and clinical judgment. Eur J Emerg Med. 2014;21(4):260–5. doi:10.1097/MEJ.0000000000000084.

- van Rein EAJ, Sadiqi S, Lansink KWW, Lichtveld RA, van Vliet R, Oner FC, Leenen LPH, van Heijl M. The role of emergency medical service providers in the decision-making process of prehospital trauma triage. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2020;46(1):131–46. Epub 20180920. doi:10.1007/s00068-018-1006-8. PubMed PMID: 30238385; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC7026224.

- Andersson U, Maurin Soderholm H, Wireklint Sundstrom B, Andersson Hagiwara M, Andersson H. Clinical reasoning in the emergency medical services: an integrative review. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2019;27(1):76. Epub 20190819. doi:10.1186/s13049-019-0646-y. PubMed PMID: 31426839; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6700770.

- Shinnick MA, Cabrera-Mino C. Predictors of nursing clinical judgment in simulation. Nurs Educ Perspect. 2021;42(2):107–9. doi:10.1097/01.NEP.0000000000000604.

- Jang A, Park H. Clinical judgment model-based nursing simulation scenario for patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding: amixed methods study. PLoS One. 2021;16(5):e0251029. Epub 20210503. PubMed PMID: 33939752; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC8092762. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0251029.

- Dorsett M, Panchal AR, Stephens C, Farcas A, Leggio W, Galton C, Tripp R, Grawey T. Prehospital airway management training and education: an NAEMSP position statement and resource document. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2022;26(sup1):3–13. doi:10.1080/10903127.2021.1977877.

- Dreyfus S, Dreyfus H. A five-stage model of the mental activities involved in directed skill acquisition.: Berkeley: University of California, Berkeley; 1980 [cited 2022 February 2nd]. Available from: https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/citations/ADA084551.

- Benner P. From novice to expert. American J Nursing. 1982;82(3):402–7.

- Perona M, Rahman MA, O'Meara P. Paramedic judgement, decision-making, and cognitive processing: a review of the literature. Australasian J Paramedicine. 2019;16:160. doi:10.33151/ajp.16.586.

- Smith MW, Bentley MA, Fernandez AR, Gibson G, Schweikhart SB, Woods DD. Performance of experienced versus less experienced paramedics in managing challenging scenarios: a cognitive task analysis study. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;62(4):367–79. Epub 20130617. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2013.04.026.

- Martín-Rodríguez F, Castro-Villamor MÁ, Del Pozo Vegas C, Martín-Conty JL, Mayo-Iscar A, Delgado Benito JF, Del Brio Ibañez P, Arnillas-Gómez P, Escudero-Cuadrillero C, López-Izquierdo R. Analysis of the early warning score to detect critical or high-risk patients in the prehospital setting. Intern Emerg Med. 2019;14(4):581–9. Epub 20190109. doi:10.1007/s11739-019-02026-2.

- Polito CC, Isakov A, Yancey AH, Wilson DK, Anderson BA, Bloom I, Martin GS, Sevransky JE. Prehospital recognition of severe sepsis: development and validation of a novel EMS screening tool. Am J Emerg Med. 2015;33(9):1119–25. Epub 20150422. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2015.04.024. PubMed PMID: 26070235; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4562872.

- Lee JS, Verbeek PR, Schull MJ, Calder L, Stiell IG, Trickett J, Morrison LJ, Nolan M, Rowe BH, Sookram S, et al. Paramedics assessing elders at risk for independence loss (PERIL): derivation, reliability and comparative effectiveness of a clinical prediction rule. CJEM. 2016;18(2):121–32. doi:10.1017/cem.2016.14.

- Croskerry P. The feedback sanction. Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7(11):1232–8. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.2000.tb00468.x.

- Ericsson KA, Krampe RT, Tesch-Römer C. The role of deliberate practice in the acquisition of expert performance. Psychol Review. 1993;100(3):363–406. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.100.3.363.

- Hubner P, Lobmeyr E, Wallmüller C, Poppe M, Datler P, Keferböck M, Zeiner S, Nürnberger A, Zajicek A, Laggner A, et al. Improvements in the quality of advanced life support and patient outcome after implementation of a standardized real-life post-resuscitation feedback system. Resuscitation. 2017;120:38–44. Epub 20170831. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2017.08.235.

- Tait RC, Chibnall JT. Racial/ethnic disparities in the assessment and treatment of pain: psychosocial perspectives. Am Psychol. 2014;69(2):131–41. doi:10.1037/a0035204.

- Hagiwara N, Kron FW, Scerbo MW, Watson GS. A call for grounding implicit bias training in clinical and translational frameworks. Lancet. 2020;395(10234):1457–60. PubMed PMID: 32359460; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC7265967. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30846-1.

- Gonzalez CM, Lypson ML, Sukhera J. Twelve tips for teaching implicit bias recognition and management. Med Teach. 2021;43(12):1368–73. Epub 20210208. doi:10.1080/0142159X.2021.1879378. PubMed PMID: 33556288; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC8349376.