Abstract

Background

Prehospital initiation of buprenorphine treatment for Opioid Use Disorder (OUD) by paramedics is an emerging potential intervention to reach patients at greatest risk for opioid-related death. Emergency medical services (EMS) patients who are at high risk for overdose deaths may never engage in treatment as they frequently refuse transport to the hospital after naloxone reversal. The potentially important role of EMS as the initiator for medication for opioid use disorder (MOUD) in the most high-risk patients has not been well described.

Setting

This project relies on four interventions: a public access naloxone distribution program, an electronic trigger and data sharing program, an “Overdose Receiving Center,” and a paramedic-initiated buprenorphine treatment. For the final intervention, paramedics followed a protocol-based pilot that had an EMS physician consultation prior to administration.

Results

There were 36 patients enrolled in the trial study in the first year who received buprenorphine. Of those patients receiving buprenorphine, only one patient signed out against medical advice on scene. All other patients were transported to an emergency department and their clinical outcome and 7 and 30 day follow ups were determined by the substance use navigator (SUN). Thirty-six of 36 patients had follow up data obtained in the short term and none experienced any precipitated withdrawal or other adverse outcomes. Patients had a 50% (18/36) rate of treatment retention at 7 days and 36% (14/36) were in treatment at 30 days.

Conclusion

In this small pilot project, paramedic-initiated buprenorphine in the setting of data sharing and linkage with treatment appears to be a safe intervention with a high rate of ongoing outpatient treatment for risk of fatal opioid overdoses.

Background

Prehospital initiation of buprenorphine treatment for opioid use disorder (OUD) by paramedics is an emerging potential intervention to reach patients at greatest risk for opioid-related death. Emergency medical services (EMS) patients who are at high risk for overdose deaths may never engage in treatment as they frequently decline transport to the hospital after naloxone reversal (Citation1–3). Not only is there a high level of stigma in treating these patients, but also there is a lack of training and education among EMS personnel about the acute treatments for OUD in the emergency department (ED) (Citation4). While there has been substantial policymaker interest in increasing ED access to buprenorphine treatment for OUD, the potentially important role of EMS as the initiator for medication for OUD (MOUD) in the most high-risk patients has not been well described.

Since 2011, death by overdose is the leading cause of accidental death in the United States; two-thirds of all overdose-related deaths involve opioids (Citation5, Citation6). According to recent data from the Centers for Disease Control, in the 12 months ending in October 2021, the number of overdose deaths increased to more than 100,000. This estimate represents the highest number of deaths ever recorded in a 12-month period, with ongoing dramatic increases year after year (Citation7). Fentanyl and its analogues have been the largest drivers of overdose deaths in the United States (Citation8). Fentanyl has several characteristics that put patients at higher risk for fatal overdose. Primarily, it is highly lipophilic with more rapid onset than even injected heroin, substantially reducing the time from use to critical respiratory depression. Potency is not easily determined by the appearance and can vary widely between batches and dealers such that regular fentanyl users may still overdose with the “same” amount they might regularly use (Citation9, Citation10). Hence, as fentanyl becomes the most prevalent illicit opioid in use, overdoses have predictably increased. Consequently, the ideal public health response should focus not only on those at risk for overdose, but also overdose survivors.

Recent data have demonstrated a significant increase in both short- and long- term mortality following opioid overdoses. Weiner et al. reported 5.5% 1-year mortality in a cohort of patients discharged from the ED after non-fatal opioid overdoses. Of those who died in the first month after discharge, many (22.3%) died within the first 48 hours (Citation11). Survivors of non-fatal opioid overdoses who decline EMS transport are at an even higher risk (Citation2). A total of 30% of patients who die from overdose have been shown to use EMS services in the year prior to their death (Citation12). Additionally, despite its life-saving characteristics, it has been shown that fewer than 8% of non-fatal narcotic overdose patients leave the ED with prescriptions for naloxone (Citation13). The increasing trend in overdose deaths, coupled with the large risk of overdose death among those with prior overdoses, highlights the need for innovations and treatment services for these particularly vulnerable patients with OUD.

Strong evidence suggests that the initiation of MOUD is the single most effective intervention to prevent overdose deaths in patients with OUD and that increasing access to medication should be a national public health priority. Evidence suggests that ED and acute care hospital-based delivery of MOUD has strongly positive outcomes (Citation14, Citation15). These facilities can serve as access portals to expand the use of buprenorphine and methadone.

Integrating EMS into ongoing efforts to increase access to OUD treatment through EDs and hospitals is a potentially high-impact and scalable treatment strategy. This intervention, if implemented widely, could reach a large population of at-risk persons with OUD who may otherwise face substantial barriers to receiving OUD treatment.

CAL OMRI

Several EMS agencies have developed novel interventions to combat the overdose epidemic. These may include increased screening and education for OUD, harm reduction techniques, treatment initiation, and active referral. After partnering with the California Bridge Program (CA Bridge) (Citation16) and the California Department of Public Health (CDPH), Contra Costa County launched an innovative, multi-pronged California Opioid Multi-agency Response Intervention project (Cal-OMRI).

This project relies on four interventions. First, a public access naloxone distribution program was funded through the CDPH. Second, an electronic trigger and warm handoff program was established through CDPH for patients experiencing overdoses or at high risk of opioid-related overdoses. These patients receive phone outreach calls and referral to outpatient treatment from substance use navigators. Third, a hospital was designated as the overdose receiving center (ORC) as a preferred transport destination with resources and personnel specifically trained in the treatment of OUD (Citation17). The ORC has two full-time navigators, access to a DEA X waivered clinician at all times for follow-up prescriptions, and low-friction access to follow-up clinic appointments for OUD treatment. Fourth, 9-1-1 responding paramedics were trained to initiate MOUD with buprenorphine in the field for patients experiencing withdrawal symptoms either independently or following naloxone reversal. This program is known as the EMS Buprenorphine Use Pilot (EMSBUP) program (Citation18).

Setting

Contra Costa County in Northern California has a population of approximately 1.2 million individuals. The EMS system is a two-tiered service with first responder advanced life support (ALS) fire agencies and ALS transport agencies responding to 9-1-1 activations. There were over 100,000 9-1-1 activations in 2020, and over 1,500 were categorized as overdose/ingestion. There were 1,089 doses of naloxone administered by EMS in 2020.

Training in OUD and Buprenorphine

For the EMSBUP pilot program, we established a limited geographical region in the county and trained approximately 180 full- and part-time 9-1-1 paramedics in the treatment of OUD using buprenorphine. The training consisted of lectures, surveys, case scenarios, clinical opiate withdrawal scale (COWS) scoring, and training in motivational interviewing. Each paramedic received approximately four hours of training in small group settings. The training materials were developed in conjunction with the CA Bridge and are available online at www.cabridge.org.

Process to Implementation

Protocol Approval

The intervention in Contra Costa County had many challenges to address prior to implementation. In California, the paramedic scope of practice is determined by the state Emergency Medical Services Authority. It authorizes changes based on recommendations from the Emergency Medical Directors Association of California’s Scope of Practice Committee. New medications can be authorized in one of two ways. First, the Scope of Practice Committee can review an application from a local EMS agency (usually country-level administration) and determine if the new drug is appropriate to be added to the paramedic scope of practice. It then can recommend approval to the EMS Authority. If the Scope of Practice committee feels the medication is unproven or not appropriate for paramedics, it can refuse to approve and suggest a trial study. This “trial study” process is how the EMS buprenorphine pilot in Contra Costa County was initiated. It involved a separate application to the state EMS Authority for approval under trial study status and the results of the study will be reviewed after 18 months, at which time an extension or expansion may be considered. The study was approved by the Public Health Institute Institutional Review Board and by the California Health and Human Services Agency Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects.

Medication Process Approval

The national director for the 9-1-1 transport agency’s controlled substances program had to approve the protocol. This involved multiple discussions and forwarding the study protocol to the national research director for the 9-1-1 agency. In addition, the distribution company that provides all controlled substances to the 9-1-1 transport agency nationally had to be convinced of the utility and necessity of having buprenorphine in a 9-1-1 system. This also involved discussions and forwarding the sample protocols and the approval from the state EMS Authority to high-level executives at the pharmaceutical distribution company. Furthermore, tracking, storage, and distribution of a new pharmaceutical to patients required an additional investment of administrative time for paramedic education specialists and supervisors.

Protocol

Naloxone Administration

The established paramedic protocol in Contra Costa County for naloxone reversal is not to fully reverse all opioid effects. The protocol for naloxone states that reversal is “Titrated to effect of adequate ventilation and oxygenation (not administered to restore consciousness)” (Citation19). Therefore, not every patient with an overdose is a candidate for buprenorphine administration. However, if the paramedic or someone else (e.g., bystander or law enforcement) inadvertently reverses the overdose fully, the patient may become a candidate.

Buprenorphine Administration and Referral

The protocol for opioid withdrawal treatment with buprenorphine begins with exclusion criteria (), including age under 18, pregnancy, any recent methadone use, altered mental status, severe medical illness, other intoxicants suspected, or the patient being unable to comprehend the risks and benefits of treatment. If the patient has no exclusions, the paramedic administers the COWS electronically, which records the score in a database. If the score is greater than 7, the paramedic then determines if the patient is interested in initiating buprenorphine, and if so, contacts the opioid withdrawal protocol physician. This physician is an “on-call” physician with knowledge of the project, and familiar with and experienced in buprenorphine administration. If the physician confirms the exclusion criteria and that there is chronic OUD, he or she approves administration. The paramedic then administers 16 mg of buprenorphine sublingually and reassesses the patient. After 10 minutes, if withdrawal symptoms persist, the paramedic may administer an additional 8 mg of buprenorphine. The paramedic then informs the patient that CDPH will initiate contact to offer additional outpatient treatment and further resources. Finally, the paramedic recommends transport to the designated ORC to provide further treatment, counseling, and resources specifically for patients with OUD. The “warm handoff” is accomplished via an electronic trigger from the EMS agency to the public health agency, and the navigator contacts the patient within 1 to 2 days. A patient handoff occurs for all overdose triggers, not just patients who receive buprenorphine. The navigator also monitors the patient retrospectively for acute clinical outcomes and 7- and 30-day engagement with treatment programs. The buprenorphine intervention was available to all patients served by the 9-1-1 transport agency. There was a phased rollout to one-third of the county in September 2020, and then the remainder of the county in February 2021.

Regulatory and Legal Considerations

The administration of buprenorphine does not require a Drug Addiction Treatment Act of 2000 X-waiver. Neither the paramedic nor the supervising physician requires additional regulatory certification, and buprenorphine can be administered similarly to other opioids commonly used by EMS. The X-waiver is required for the prescription of buprenorphine for the treatment of OUD only. The “3-day rule” (Title 21, Code of Federal Regulations, Part 1306.07) is normally applicable to ED practice and permits discharged hospital patients to return for repeat maintenance doses of buprenorphine for three consecutive days pending entry into a treatment program.

Quality Assurance

To ensure consistent application of the study protocol, a quality assurance team was assembled for weekly reviews of potential cases. This team consists of the navigator at the ORC (Citation17), the clinical education specialist at the 9-1-1 transport agency, the research associate for the EMSBUP project, and the EMS medical director for the 9-1-1 transport agency. This team met on a weekly basis and reviewed two distinct types of cases: potential overdose cases and actual buprenorphine administrations. All overdoses in the 9-1-1 system are flagged via an electronic data monitoring system (FirstWatch™, Carlsbad, CA) and sent to the quality assurance team once the 9-1-1 call has been dispatched. Additionally, all patient care reports (PCRs) with the word buprenorphine, fentanyl, heroin, and their common misspellings were also flagged and sent to the quality assurance team. The quality assurance team reviews each PCR to assess whether the patient was an appropriate candidate for buprenorphine administration, was appropriately eliminated from the protocol for protocol exclusions, or was a potential case that was not administered buprenorphine. The individual paramedics involved in each missed potential case are then educated by the clinical education specialist for future cases. Additionally, all buprenorphine cases are reviewed by the EMSBUP oversight team on a biweekly basis. The oversight team consists of the medical directors of the public health department, the local EMS agency, the 9-1-1 transport agency, the director of the California Bridge program, and program coordinators from the local EMS agency and other interested parties.

Results

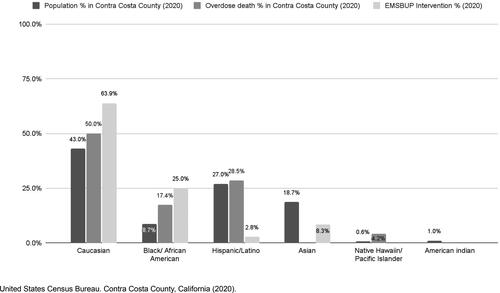

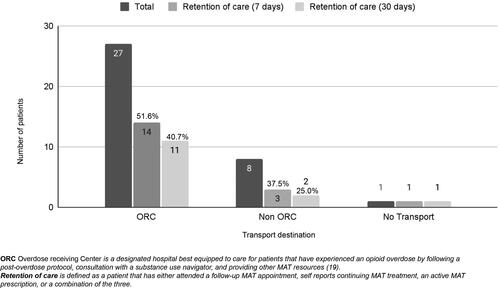

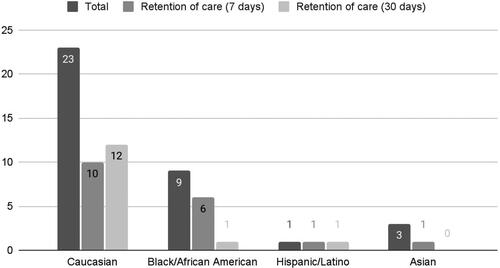

In the first year, 36 patients received buprenorphine (). Of patients receiving buprenorphine, 63.9% were White, 25% were African American, 2.8% were Latinx, and 8.3% were Asian (). Most patients who received buprenorphine were experiencing withdrawal symptoms because they had been abstinent from opioids for long enough to experience withdrawal symptoms (22/36, 61%) rather than experiencing withdrawal symptoms as a result of receiving naloxone. All patients were transported to the ED, except for one who declined transport against medical advice. Additionally, most patients (27/36, 75%) were willing to be transported to the designated ORC within the EMS service area.

Table 1. Demographic and treatment characteristics of EMSBUP patients.*

Data on clinical outcomes as well as 7- and 30-day follow-ups were obtained for all 36 patients. No precipitated withdrawal or other adverse outcomes were documented or observed in the immediate period after receiving buprenorphine. Among patients who received buprenorphine from EMS, there were no cases of precipitated withdrawal. All patients had improved COWS scores (29/36) or no change in their symptoms (7/36). Review of the PCRs from EMS and subsequent emergency department care revealed no cases of any worsening withdrawal symptoms or precipitated withdrawal.

The majority of patients were discharged from the ED (31/36, 86%). Of the five patients (14%) who were admitted, none were admitted for worsening withdrawal symptoms. One patient was admitted for opioid withdrawal symptoms of ongoing nausea and vomiting, but the clinical scenario did not indicate the symptoms were worse than when the patient activated the 9-1-1 system. Two patients were admitted to the psychiatric unit for suicidal ideation. One additional patient had cellulitis. The final admitted patient presented with hypoxia and an inability to walk with a steady gait.

All overdoses in the county were followed and the PCRs were evaluated to see if they were candidates for buprenorphine administration based on the protocol. Of the 587 total patients who had overdosed, 79 fit possible inclusion criteria established by the protocol, and 36 of those (45.6%) were included in the buprenorphine study protocol. Of the patients in the study, 23 of 36 reported known fentanyl usage to paramedics.

Patients who received buprenorphine were followed for 30 days by the navigator to see if they were in treatment for OUD and if they filled outpatient buprenorphine prescriptions. A patient was counted as “in treatment” if he or she had both a clinic visit and an outpatient prescription for buprenorphine filled. Half of the patients (18/36) were in treatment at 7 days and 36% (14/36) were in treatment at 30 days. Of the patients who were transported to the ORC, 11 of 27 (40.7%) were in treatment at 30 days, compared to the 2 of 8 (25%) who went to other receiving centers (). Some differences in retention by race were observed. Of the white patients who received buprenorphine, 12 of 23 were in care at 30 days but only 1 of 9 black patients was. Further stratification of the patients by age, ethnicity, amount of naloxone administered, and amount of buprenorphine administered as a function of whether they went to an ORC can be seen in .

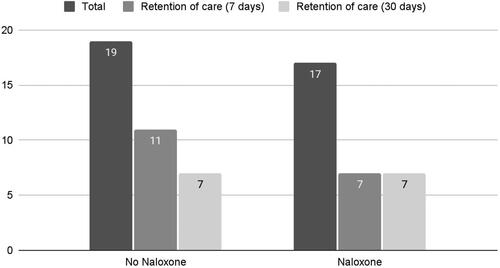

Patients were further stratified into naloxone exposure () and ethnicity () with respect to long-term treatment outcome. Of the 19 patients who did not receive naloxone as part of their EMS intervention, 7 were in care at 30 days. Of the 17 patients who did receive naloxone, 7 patients were in care at 30 days. The naloxone dosing and COWS scores as well as retention in treatment are shown in .

Table 2. Retention and outcomes by naloxone dose administration.

Based on navigator follow-up, all of the overdose patients enrolled in paramedic-initiated buprenorphine administration were still alive 30 days after the initial buprenorphine encounter.

Discussion

Our results add to the growing evidence that EMS-administered buprenorphine is a pragmatically feasible and well-tolerated intervention for OUD patients who were in withdrawal. Our findings should be considered in the context that most overdose survivors receive no interventions that promote the most effective treatment proven to reduce mortality—initiation of MOUD. Our pilot did not observe any clinical events to support potential concerns for safety. This is not surprising as buprenorphine has already established a strong safety record in the ED setting.

All patients were followed for clinical outcomes by the navigator, including the patient who had signed out against medical advice. In no case did a patient experience any precipitated withdrawal or worsening of symptoms due to paramedic-administered buprenorphine. Six patients did not have improvement of their COWS score while still in the paramedic’s care, but no patient appeared to experience an adverse event attributable to buprenorphine treatment. Importantly, the majority (23 of 36, 64%) of the treated patients reported primarily using fentanyl.

Either abstinence from opioids or naloxone administration after an opioid overdose can cause withdrawal symptoms. In this study, over 60% of patients were in withdrawal and received buprenorphine as a result of abstinence, rather than naloxone-induced withdrawal symptoms. This was an unexpected finding and signals the high community demand for emergency treatment of opioid withdrawal. This finding is unique to this pilot intervention as it is the only EMS project of which we are aware to include non-naloxone associated withdrawal in the eligibility criteria. This finding highlights the persistence of barriers to access and the frequency of withdrawal crises in the OUD population. Interestingly, this occurred before widespread community knowledge that EMS buprenorphine was available. Public education campaigns could dramatically increase utilization, which, given the value of a single buprenorphine start, could potentially further expand the use of EMS in reducing overdose deaths. The first EMS system to implement an MOUD treatment option for patients in withdrawal allows paramedics to administer buprenorphine to patients but only if in withdrawal due to post naloxone administration (Citation14). Our intervention allows for the alleviation of withdrawal symptoms and pain through buprenorphine administration regardless of the cause of withdrawal. The current EMS protocol suggests titrating low doses of naloxone to minimal sustainment of sufficient respiratory function. There is widespread debate on the risks and benefits of alternative naloxone dosing protocols that also target reversal of sedation. Having a viable rescue medication (buprenorphine) for unpleasant withdrawal symptoms is an interesting new component of this discussion.

Long Term Treatment Retention

Contrary to some existing perceptions in the treatment community that overdose victims are “not ready” to engage in treatment, we found a remarkably high 30-day retention rate in treatment of 36%, consistent with similar real-world MOUD programs in the ED and ambulatory setting. This finding in an EMS system is remarkable in that, if confirmed, it could potentially lead to earlier buprenorphine administrations, shortened ED length of stays, larger catchment areas, and reaching patients who might not go to EDs with established OUD and substance use navigator programs. Of note, the percentage achieved in the published literature for outpatient clinics with motivated, potentially more resourced patients is 52.6% at 1 year (Citation20). Subsequent studies are urgently needed to confirm the finding that for every three EMS patients treated with buprenorphine, one remains in treatment at 30 days.

Addressing Racial Inequities in Overdose Deaths

While affecting all racial and social boundaries, overdose deaths have disproportionately affected some racial and ethnic groups. The growing racial disparity has been well-documented with one recent study noting the majority of the increase in overdose visits to EDs in 2020 was among African American and Latinx patients (Citation21). In Contra Costa County, African Americans make up 9.3% of the county population but 21.5% of the overdose deaths (Citation22) (). Remarkably, African Americans accounted for 25% of the buprenorphine pilot program patients, which might be an indication EMS is an effective means of reaching these patients. These findings suggest that this EMS intervention has potential to effectively engage with high-risk patients and reduce disparities in OD for some communities.

Overdose Center Destination Decision

It is not clear which factors influenced the destination decision to go to an ORC. Transport to an ORC was not a requirement but a suggestion for both EMS clinicians and patients. It may be that EMS clinicians who thought the patient was willing to accept treatment would be a good candidate for the ORC. It may also be that patients who had been in treatment already and had accepted buprenorphine were also willing to accept the destination decision where more treatment and counseling would be available, as described by the paramedic. While the ORC is centrally located in the county, some patients would have to bypass the closest facility to arrive at the ORC.

EMS System of Care for OUD

The intervention collaborators decided early in the process that an EMS-initiated buprenorphine program would only be successful with the additional outreach processes in place. The results shown in the buprenorphine intervention must not be taken out of context as there were four overlapping pilots (including buprenorphine) occurring at the same time. The additional interventions included a leave-behind naloxone program, a designation of an ED as an ORC, and a warm data handoff between the EMS agency and the public health substance use navigator counseling program. This multifaceted approach was necessary to ensure adequate patient follow-up and linkage to additional outpatient care. It may not always be possible to have a multifaceted program, but such integration in this setting achieved remarkable results. However, it is possible that such results are only possible with all four pilot projects in place. More study is needed to understand the isolated effects of EMSBUP from the other components.

The literature indicates that buprenorphine has a clear mortality benefit (Citation23). Often the challenge for patients with OUD is access to outpatient clinics and other resources. The use of EMS in this pilot system allows for the expansion of access for patients who might otherwise not engage w with the health care system. These patients are traditionally disadvantaged, marginalized, and face significant hurdles to access clinic and treatment resources (Citation24). This program allows EMS clinicians to not only treat these patients for OUD but connect them to services and counseling resources.

The multi-pronged intervention described here to help reduce opioid-related overdose and death is an example of integrating the EMS workforce with public health efforts. Looking toward the future, EMS systems may be uniquely positioned to form a similar bridge between traditional EMS and hospital system interventions like trauma, stroke, or myocardial infarction care and more public health-based measures such as pediatric safety and elder health issues, as well as broader social themes such as harm reduction and hospice awareness (Citation25). EMS can reach almost all patients; its reach extends across racial, social, political, insurance, and economic divides. A joint partnership of EMS and public health colleagues can form the foundation for a host of novel interventions with lasting health effects across societal domains, with a large potential to reduce health disparities.

Limitations

The findings reflect results from one site over a limited period of time, thus generalizability may be limited until further research is performed. It is not clear if the results found are the result of the four projects implemented at the same time, or just the buprenorphine intervention. Treatment retention rates are possibly affected by high motivation for patients who agreed to buprenorphine treatment. Additionally, while no adverse outcomes or precipitated withdrawal events were observed in this limited study, instances of buprenorphine-induced withdrawal or other side effects may be observed in larger scale implementation.

Conclusions

These results after one year of study implementation and the evolving literature on alternative settings for buprenorphine treatment provide opportunities for further research. Future trials might use the controlled implementation protocols piloted in this intervention to assess for sustained engagement in treatment services and determine any mortality benefit for EMS-based encounters with patients who have OUD. EMS administered buprenorphine is possible, safe, and results in significant retention in care at 30 days. A future multi-center randomized controlled trial comparing buprenorphine to standard care (no buprenorphine) and measuring treatment retention and mortality would provide further insight into this novel treatment modality for EMS.

Disclosure Statement

All authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Rock P, Singleton M. EMS heroin overdoses with refusal to transport & impacts on ED overdose surveillance. Online J Public Health Inform. 2019;11(1):e430. doi:10.5210/ojphi.v11i1.9917.

- Zozula A, Neth MR, Hogan AN, Stolz U, McMullan J. Non-transport after Prehospital Naloxone Administration Is Associated with Higher Risk of Subsequent Non-fatal Overdose. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2022;26(2):272–279. doi: 10.1080/10903127.2021.1884324.

- Glenn MJ, Rice AD, Primeau K, Hollen A, Jado I, Hannan P, McDonough S, Arcaris B, Spaite DW, Gaither JB, et al. Refusals after prehospital administration of naloxone during the COVID-19 pandemic. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2021;25(1):46–54. doi:10.1080/10903127.2020.1834656.

- Hawk KF, D'Onofrio G, Chawarski MC, O'Connor PG, Cowan E, Lyons MS, Richardson L, Rothman RE, Whiteside LK, Owens PH, et al. Barriers and facilitators to clinician readiness to provide emergency department-initiated buprenorphine. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(5):e204561. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.4561.

- Leading causes of death and injury—PDFs|injury center|CDC. Cdc.gov.; 2020 Jul 10 [accessed 2019 Oct 1] https://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/LeadingCauses.html.

- Scholl L. Drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths—United States, 2013–2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;67(5152);1419–1427. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6751521e1.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Products—vital statistics rapid release—provision drug overdose data. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2022 Jan 12 [accessed 2020 May 21]. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/drug-overdose-data.htm.

- Han Y, Yan W, Zheng Y, Khan MZ, Yuan K, Lu L. The rising crisis of illicit fentanyl use, overdose, and potential therapeutic strategies. Transl Psychiatry. 2019;9(1):282. doi:10.1038/s41398-019-0625-0.

- Somerville NJ, O'Donnell J, Gladden RM, Zibbell JE, Green TC, Younkin M, Ruiz S, Babakhanlou-Chase H, Chan M, Callis BP, et al. Characteristics of fentanyl overdose—Massachusetts, 2014-2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(14):382–6. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6614a2.

- Mars SG, Rosenblum D, Ciccarone D. Illicit fentanyls in the opioid street market: desired or imposed? Addiction. 2019;114(5):774–80. doi:10.1111/add.14474.

- Weiner SG, Baker O, Bernson D, Schuur JD. One-year mortality of patients after emergency department treatment for nonfatal opioid overdose. Ann Emerg Med. 2020;75(1):13–7. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2019.04.020.

- Barefoot EH, Cyr JM, Brice JH, Bachman MW, Williams JG, Cabanas JG, Herbert KM. Opportunities for emergency medical services intervention to prevent opioid overdose mortality. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2021;25(2):182–90. doi:10.1080/10903127.2020.1740363.

- Chua K-P, Dahlem CH, Nguyen TD, Brummet CM, Conti RM, Bohnert AS, Dora-Laskey AD, Kocher KE. Naloxone and buprenorphine prescribing following US emergency department visits for suspected opioid overdose: August 2019 to April. Ann Emerg Med. 2022;79(3):225–236. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2021.10.005.

- Carroll GG, Wasserman DD, Shah AA, Salzman MS, Baston KE, Rohrbach RA, Jones IL, Haroz R. Buprenorphine Field Initiation of ReScue Treatment by Emergency Medical Services (Bupe FIRST EMS). A case series. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2020;25:289–293. doi:10.1080/10903127.2020.1747579.

- D’Onofrio G, O’Connor PG, Pantalon MV, Chawarski MC, Busch SH, Owens PH, Bernstein SL, Fiellin DA. Emergency department-initiated buprenorphine/naloxone treatment for opioid dependence: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;313(16):1636–44. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.3474.

- Snyder H, Kalmin MM, Moulin A, Campbell A, Goodman-Meza D, Padwa H, Clayton S, Speener M, Shoptaw S, Herring AA. Rapid adoption of low-threshold buprenorphine treatment at California Emergency Departments participating in the CA Bridge Program. Ann Emerg Med. 2021;78(6):759–772.

- Hern HG, Goldstein D, Tzvieli O, Mercer M, Sporer K, Herring AA. Overdose receiving centers—an idea whose time has come? Prehosp Emerg Care. 2021;2:1–4. doi:10.1080/10903127.2020.1864073.

- Hern HG, Goldstein D, Kalmin M, Kidane S, Shoptaw S, Tzvieli O, Herring AA. Prehospital initiation of buprenorphine treatment for opioid use disorder by paramedics. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2021;22:1–7. doi:10.1080/10903127.2021.1977440.

- Contra Costa County Emergency Medical Services. Suspected opioid overdose; [accessed 2021 Jun 4] 2020. https://cchealth.org/ems/pdf/2021-tg/4A13aSuspectedOpioidOverdose.pdf.

- Montalvo C, Stankiewicz B, Brochier A, Henderson DC, Borba CPC. Long-term retention in an outpatient behavioral health clinic with buprenorphine. Am J Addict. 2019;28(5):339–46. doi:10.1111/ajad.12896.

- Soares WE, 3rd, Melnick ER, Nath B, D'Onofrio G, Paek H, Skains RM, Walter LA, Casey MF, Napoli A, Hoppe JA, et al. Emergency department visits for nonfatal opioid overdose during the COVID-19 pandemic across six US health care systems. Ann Emerg Med. 2022;79(2):158–67. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2021.03.013.

- California Department of Public Health. California Overdose Surveillance Dashboard—Contra Costa County, 2021; [accessed 2021 Oct 1]. https://skylab.cdph.ca.gov/ODdash/.

- Wakeman SE, Larochelle MR, Ameli O, Chaisson CE, McPheeters JT, Crown WH, Azocar F, Sanghavi DM. Comparative effectiveness of different treatment pathways for opioid use disorder. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(2):e1920622. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.20622.

- Kalmin MM, Goodman-Meza D, Anderson E, Abid A, Speener M, Snyder H, Campbell A, Moulin A, Shoptaw S, Herring AA. Voting with their feet: social factors linked with treatment for opioid use disorder using same-day buprenorphine delivered in California hospitals. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021;222:108673. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.108673.

- Breyre AM, Bains G, Moore J, Siegel L, Sporer KA. Hospice and comfort care patient utilization of emergency medical services. J Palliat Med. 2022;25(2):259–264. doi:10.1089/jpm.2021.0143.