Abstract

Objective

Emergency medical services (EMS) play a key role in access to prehospital emergency care. While EMS has defined levels of certification, the roles in the care paradigm fulfilled by these clinicians vary. The aim of this study is to describe the national differences between EMS clinicians with primary non-patient care vs. patient care roles.

Methods

We performed a cross sectional evaluation of nationally certified EMS clinicians in the United States who recertified in 2020. As part of the recertification process, applicants voluntarily complete profile questions regarding demographic, job, and service characteristics. We compared the characteristics between individuals self-reporting primary patient care roles vs. non-patient care roles. Using logistic regression, we determined independent predictors for having a non-patient care role.

Results

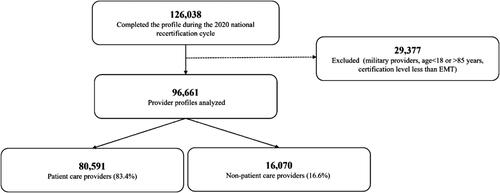

In 2020, 126,038 people completed recertification. Of the 96,661 completing the profile, 80,591 (83.4%) indicated that they provided patient care, and 16,070 (16.6%) did not provide patient care as a primary role. Non-patient care personnel were more likely to be older (median 43 years old vs 34 years old), and to have a higher level of education (bachelor’s degree or more: OR 2.25, 95%CI [2.13–2.38]) compared with patient care practitioners. Non-patient care personnel were less likely to be female (0.67 [0.64–0.70]) and minorities (OR 0.80 [0.76–0.84]). Non-patient care personnel reported longer work experience (16 years or more: OR 6.30 [5.98–6.64]), were less likely to hold part time positions (OR 0.62 [0.59–0.65]), and were less often attached to more than one agency (OR 0.83 [0.79–0.86]). Non-patient care personnel were less likely to work in rural settings (OR 0.81 [0.78–0.85]).

Conclusions

EMS clinicians in non-patient care roles account for 17% of the study population. The odds of performing as a non-patient care practitioner are associated with characteristics related to demographics and workforce experience. Future work will be necessary to identify mechanisms to encourage diversity within the patient care and non-patient care workforces.

Introduction

Emergency medical services (EMS) play a key role in access to care, often serving as first responders to acute and life-threatening emergencies (Citation1). In 2010, there were an estimated 17.4 million EMS emergency responses in the United States (US), demonstrating the large medical care network supported by EMS clinicians (Citation2, Citation3). Members of the EMS profession are well-known to provide direct care to patients, but others serve in non-patient care roles as educators, administrators, supervisors, or other leaders at their agencies.

While most studies focus on the demographics of the EMS population providing patient care, there is paucity of evidence on the characteristics of those not providing direct patient care. Though less emphasized in research, their roles are nevertheless essential within the EMS structure. These roles may provide several areas of EMS support including administrative structure, medical care coordination, continuing education infrastructure, and quality evaluation. As more attention is focused on the stability of the EMS workforce, understanding this population is essential to guide policy and workforce planning.

Another challenge in the US is the lack of diversity in the EMS workforce population (Citation4–6). The EMS Agenda 2050 recommended that “local EMS leadership, educators and clinicians reflect the diversity of their communities” (Citation7–12). Unfortunately, in the US, we know that the population of EMS personnel serving in primarily patient care roles is not diverse, being predominantly male (75%) and White (85%) (Citation8, Citation13–17). Enhanced diversity has been shown to reduce barriers in communication, increase culturally competent care, and improve overall quality of care delivery to minority patient populations (Citation4, Citation5). It is unclear if this disparity is also present in the non-patient care workforce.

There are few data concerning the demography of EMS personnel serving non-patient care roles or how they may differ from patient care practitioners. In this evaluation, our aim is to describe the population of EMS clinicians who function in primarily non-patient care roles.

Methods

Study Design and Setting

We performed a cross sectional evaluation of data from the National Registry of Emergency Medical Technicians recertification dataset from 2020. Accredited by the National Commission for Certifying Agencies, the National Registry is a nonprofit organization that provides certification of EMS clinicians at more than 46 states, territories, and federal agencies. EMS clinicians at all levels recertify with the National Registry on a biennial and voluntary basis, though 10 states require national EMS certification to maintain EMS licensure at one or more levels (Citation13, Citation18). This study was deemed exempt by the American Institutes of Research Institutional Review Board.

Population

Levels of EMS clinicians certified by the National Registry include emergency medical responder (EMR), emergency medical technician (EMT), advanced emergency medical technician (AEMT), and paramedic. This study included all civilian EMS clinicians ages 18–85 years old, who recertified their national certification in 2020, at the level of EMT or higher. Because of practice and organizational differences, we excluded military and EMR practitioners from the study.

Identification of Job Role

We divided the cohort into two major groups: (1) those who reported providing regular direct patient care duties, and (2) those who reported being non-patient care personnel. As part of the recertification process, registry applicants voluntarily complete profile questions regarding demographic, job, and service characteristics (Citation19–21). The role was therefore self-declared by each respondent. In case the respondent had several roles in EMS, only the first was included, considering this first role as the main EMS role. Primary patient care job roles included positions where the main duty was the provision of direct clinical EMS care. Non-patient care roles included duties falling outside of primary patient care duties, including but not limited to leadership, administration, support, or education. The non-patient care roles were further defined as the following: supervisor (direct supervision of individuals providing EMS), administrator (management and direction of an organization providing EMS), educator (train individuals enrolled in an approved or accredited EMS training course or continuing education), telecommunicator (answer emergency and nonemergency calls and provide resources to assist those in need), or other (primary EMS role not listed above) (Citation10, Citation15).

Measures

The demographic characteristics included sex (designated as male or female), minority status, and education level. Due to the small proportion of minority EMS clinicians, minority status was dichotomized to non-minority (White, non-Hispanic) or minority. The minority category included any person who self-identified as Black or African American, Asian, Hispanic, or Latino, Native Hawaiian, or Pacific Islander. Education level was categorized as high school or general educational development or less, some college experience, associate’s degree, or bachelor’s degree or more.

Job information provided by respondents included years of experience in EMS (2 years or less; 3–7 years; 8–15 years; 16 years or more), working time (full-time/part-time), and number of organizations (the number of EMS jobs held categorized as none, 1, 2, or more). Agency characteristics included main agency (defined as the agency for which someone did most of his or her EMS work), service type (e.g., primarily 9-1-1, medical transport, combination of 9-1-1/medical transport, clinical service, mobile integrated health/community paramedicine), and urbanicity (rural defined as <25,000 people and urban as ≥25,000 people).

Analysis

We compared differences between EMS clinicians with primary non-patient care and patient care duties. Our primary outcome was the comparison of demographic and job characteristics of those who provided and those who did not provide patient care. A subgroup analysis was also conducted examining the differences between EMS clinicians with primary non-patient care leadership duties (specifically administrator, supervisor, and educator) and primarily patient care roles. We restricted the non-patient care population in this analysis to these groups to focus on the common non-patient care roles (77% of all non-patient care personnel).

All analyses were completed using STATA IC version 17 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX). Age was analyzed as a continuous variable and all other variables were treated categorically. Continuous variables were described with median and interquartile range (median (IQR)). Categorial variables were collected and expressed as percentage (%) of the total for each group. Odds ratios (OR) for associations were calculated using univariable logistic regression. The 95% confidence interval and p-value for each OR were tabulated, with p < 0.05 deemed significant.

Results

A total of 126,038 participants completed the recertification profile during the 2020 national recertification cycle. Of those who completed the profile, 96,661 satisfied inclusion criteria (77%). Among included respondents, 80,591 reported a primary patient care role (83.4%) while 16,070 reported a primary non-patient care role (16.6%) (). The most common non-patient care roles were supervisors, administrators, and educators ().

Figure 1. Flow chart study participants who provided profile data during the 2020 national recertification cycle.

Table 1. Non-patient care roles reported during the 2020 national recertification cycle.

An evaluation of the demographic differences between patient care and non-patient care personnel are noted in . Females were less likely to report non-patient care roles than males (OR = 0.67, 95%CI [0.64–0.70]). The likelihood of reporting a non-patient care role increased with age (30–35 years OR = 2.02 [1.89–2.16]; 36–44 years OR = 4.13 [3.88–4.39]; 45–85 years OR = 6.08 [5.72–6.45]; referent 18–29 years). Minority EMS clinicians were less likely to report non-patient care roles (OR = 0.80 [0.76 to 0.84]). The odds of a reported non-patient care role increased with education and years of EMS experience.

Table 2. Demographic characteristics, work experience, agency characteristics, and their association with the odds of having a non-patient care role reported during the 2020 national recertification cycle.

Non-patient care personnel were less likely to work part-time or to work in more than one organization (). Almost half of non-patient care personnel worked for fire departments. Non-patient care personnel were more likely to work for non-governmental agencies, compared to fire agencies. Those working for medical transport or combination of medical transport with 9-1-1 were less likely to be non-patient care personnel, compared to primarily 9-1-1. Non-patient care personnel were more likely to work for clinical services and mobile integrated health/community paramedicine, compared to primarily 9-1-1. Non-patient care personnel were less likely to work in rural communities.

Results of the subgroup analysis comparing primary non-patient care leadership duties (specifically administrator, supervisor, and educator) and primarily patient care roles are noted in . The effects of the previous analysis were more pronounced for sex (OR = 0.56 [0.53 to 0.59]), age (30–35 years OR = 3.36 [3.06–3.70]; 36–44 years OR = 8.15, [7.45–8.91]; 45–85 years OR = 12.81, [11.74–13.99]; referent 18–29 years), and minority status (OR = 0.65 [0.62 to 0.69]). Similarly, compared to the previous analysis, odds of being a non-patient care practitioner increased with years of experience (3–7 years OR = 1.92 [1.79–2.07]; 8–15 years OR = 4.65 [4.34–4.98]; 16 years or more OR = 11.08 [10.36–11.83]; referent 2 years or less).

Table 3. Subgroup analysis of specific non-patient care roles (supervision, administration, and education) with demographic characteristics, work experience, agency characteristics, and their association with the odds of being in the subgroup.

Discussion

The majority of EMS clinicians in the United States serve as patient care practitioners, with a smaller fraction functioning in primarily non-patient care roles (Citation13, Citation14). These roles are particularly critical in that many of them assist in the supervision of EMS care, education of future and current EMS clinicians, and management of EMS agencies. This cross-sectional study highlights the diversity of practice within EMS. In this evaluation, 17% of the study population identified themselves as non-patient care personnel and many of the trends noted in patient care practitioners are more pronounced in the non-patient care personnel population, including low numbers of females and minority groups in these positions (Citation6). Compared to patient care practitioners, as EMS clinicians age, gain experience in the field, and enhance their education, they have higher odds of functioning as in non-patient care roles, which typically consist of leadership positions including supervision, administration, and education. Non-patient care personnel work predominantly in public agencies, and in fire departments for more than half.

One important concept for clinicians considering moving to these types of roles is that non-patient care positions are preferably occupied by staff with more experience, suggesting positive prospects for career development within EMS. EMS career development pathways are often not as clearly delineated as are the chain of command structures common in fire safety. This study demonstrates that there are inherent opportunities for advancement in EMS that should be clarified to support training and retention in the profession (Citation22). Unfortunately, these opportunities may be challenging for many front-line personnel since they are sometimes difficult to satisfy without additional attainment (e.g., bachelor’s education). Further work is necessary to better define these pathways and identify mechanisms to facilitate advancement and retention.

While non-patient care personnel play a critical role in EMS, there have been very few studies defining this population or the characteristics of those serving in these roles. This evaluation defines this population but also identifies areas to be addressed. Specifically, we noted that the odds of reaching these positions may be lower in gender and racial minority populations () reflecting the diversity challenges in EMS (Citation6, Citation23). The overall goal set in the EMS Workforce Agenda emphasized that local EMS leadership, educators, and clinicians should reflect the diversity of their communities to provide more culturally sensitive health care and access largely untapped sources of potential workforce (Citation9). Unfortunately, the larger patient care practitioner population, graduates from programs, and EMS instructors do not reflect the diversity in the US (Citation21, Citation23, Citation24). Our subgroup analysis noted that these effects were even more pronounced when restricting our non-patient care roles to only leadership positions (supervision, administration, or education). Future work is needed to develop best practices in EMS recruitment to assist education programs and EMS systems in the recruitment of gender and racial minorities (Citation10).

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, there is potential for classification bias by the fact that the role is self-reported. An EMS clinician can perform several roles at the same time, and we only focused on the first declared, or main role. In this analysis, we do not account for patient care practitioners serving in secondary non-patient care roles or having second jobs as non-patient care personnel. This is an important nuance and a complicated issue that requires further study based on our results. Second, we suggest that missing data may be more common among minority groups, potentially magnifying this bias in affected groups (Citation25). Third, the use of the national EMS certification database as a sample for the EMS workforce may result in selection bias since not all EMS clinicians are required to obtain or maintain national certification. Individuals who recertified their national EMS certification may have different motivations for gaining certification and continuing to practice in EMS. Further investigations are needed to better understand these issues.

Conclusion

There is a wide range of non-patient care related jobs within EMS systems, including those with care-focused missions, such as education, and those with more administrative or leadership focused tasks. Odds of performing as one of these non-patient care personnel are associated with characteristics related to demographics and workforce experience. Encouraging diversity and equity will require efforts to promote underrepresented groups to pursue careers in EMS among all job categories.

Author Contributions

ADF, HW, ARP conceived and designed the study. ARP, JRP, and JDK completed data collection. Data analysis was performed by ADF, ARP, and JRP. ADF drafted the manuscript. ADF, ARP, HW, JRP, and JDK made interpretations/revisions. ADF takes responsibility for the paper as a whole.

Disclosure Statement

The authors report no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- Pozner CN, Zane R, Nelson SJ, Levine M. International EMS systems: the United States: past, present, and future. Resuscitation. 2004;60(3):239–44. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2003.11.004.

- Wang HE, Mann NC, Jacobson KE, MS MD, Mears G, Smyrski K, Yealy DM. National characteristics of emergency medical services responses in the United States. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2013;17(1):8–14. doi:10.3109/10903127.2012.722178.

- Dawson DE. National Emergency Medical Services Information System (NEMSIS). Prehosp Emerg Care. 2006;10(3):314–6. doi:10.1080/10903120600724200.

- Jackson CS, Gracia JN. Addressing health and health-care disparities: the role of a diverse workforce and the social determinants of health. Public Health Rep. 2014;129(1_suppl2):57–61. doi:10.1177/00333549141291S211.

- Betancourt J. Improving quality and achieving equity: the role of cultural competence in reducing racial and ethnic disparities in health care. New York (NY): Commonwealth Fund; 2006.

- Crowe RP, Krebs W, Cash RE, Rivard MK, Lincoln EW, Panchal AR. Females and minority racial/ethnic groups remain underrepresented in emergency medical services: a ten-year assessment, 2008-2017. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2020;24(2):180–7. doi:10.1080/10903127.2019.1634167.

- Marrast LM, Zallman L, Woolhandler S, Bor DH, McCormick D. Minority physicians’ role in the care of underserved patients: diversifying the physician workforce may be key in addressing health disparities. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(2):289–91. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.12756.

- Cohen JJ, Gabriel BA, Terrell C. The case for diversity in the health care workforce. Health Aff (Millwood). 2002;21(5):90–102. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.21.5.90.

- EMS Agenda 2050. A people-centered vision for the future of emergency medical services; 2011 May [accessed 2021 Dec 1]. https://www.ems.gov/pdf/EMS-Agenda-2050.pdf.

- EMS Workforce Initiatives [Internet]; 2021 [accessed 2022 Jan 27]. https://www.ems.gov/workforce.html.

- EMS Update—Collaborating to Improve Care [Internet]; 2019 [accessed 2022 Jan 27]. https://www.ems.gov/newsletter/may2019/EMS-scope-of-practice.html.

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Institutional and Policy-Level Strategies for Increasing the Diversity of the U.S. Healthcare Workforce. In the nation’s compelling interest: ensuring diversity in the health-care workforce. Smedley BD, Stith Butler A, Bristow LR, editors. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2004 [accessed 2021 Dec 10]. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK216009/.

- Rivard MK, Cash RE, Mercer CB, Chrzan K, Panchal AR. Demography of the national emergency medical services workforce: a description of those providing patient care in the prehospital setting. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2021;25(2):213–20. doi:10.1080/10903127.2020.1737282.

- Levine R. Longitudinal Emergency Medical Technician Attributes and Demographic Study (LEADS) design and methodology. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2016;31(S1):S7–S17. doi:10.1017/S1049023X16001059.

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics [Internet]; 2021. [cited 2021 Dec 9]. https://www.bls.gov/.

- Bentley MA, Shoben A, Levine R. The demographics and education of emergency medical services (EMS) professionals: a national longitudinal investigation. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2016;31(S1):S18–S29. doi:10.1017/S1049023X16001060.

- Chapman SA, Crowe RP, Bentley MA. Recruitment and retention of new emergency medical technician (EMT)-basics and paramedics. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2016;31(S1):S70–S86. doi:10.1017/S1049023X16001084.

- About the National Registry | National Registry of Emergency Medical Technicians [Internet]. [accessed 2022 Apr 4]. https://nremt.org.

- Rivard MK, Cash RE, Chrzan K, Panchal AR. The impact of working overtime or multiple jobs in emergency medical services. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2020;24(5):657–64. doi:10.1080/10903127.2019.1695301.

- Cash RE, Rivard MK, Chrzan K, Mercer CB, Camargo CA, Panchal AR. Comparison of volunteer and paid EMS professionals in the United States. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2021;25(2):205–12. doi:10.1080/10903127.2020.1752867.

- Crowe RP, Levine R, Eggerichs JJ, Bentley MA. A longitudinal description of emergency medical services professionals by race/ethnicity. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2016;31(S1):S30–S69. doi:10.1017/S1049023X16001072.

- Crowe RP, Bower JK, Cash RE, Panchal AR, Rodriguez SA, Olivo-Marston SE. Association of burnout with workforce-reducing factors among EMS professionals. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2018;22(2):229–36. doi:10.1080/10903127.2017.1356411.

- Ruple JA, Frazer GH, Hsieh AB, Bake W, Freel J. The state of EMS education research project: characteristics of EMS educators. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2005;9(2):203–12. doi:10.1080/10903120590924807.

- Ruple JA, Frazer GH, Bake W. Commonalities of the EMS Education Workforce (2004) in the United States. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2006;10(2):229–38. doi:10.1080/10903120500541316.

- Bilheimer LT, Klein RJ. Data and measurement issues in the analysis of health disparities. Health Serv Res. 2010;45(5 Pt 2):1489–507. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01143.x.