Abstract

Emergency medical services (EMS) systems are designed to provide care in the field and while transporting patients to a hospital; however, patients enrolled in hospice may not want invasive therapies nor benefit from hospitalization. For many reasons, encounters with hospice patients can be challenging for EMS systems, EMS clinicians, hospice clinicians, hospice patients, and their families.

NAEMSP Recommends

EMS clinicians should receive hospice-focused education that fosters a basic understanding of hospice, palliative therapies, and advance care planning documents (e.g., Physician Orders for Life Sustaining Treatment). This education should emphasize the ongoing development of end-of-life communication skills.

EMS medical directors and local hospice organizations should collaborate to develop hospice patient-centered EMS protocols that address symptom management and delineate appropriate and goal concordant clinical interventions, and that are within the agency-level scope of practice for local EMS clinicians. Partnerships between EMS and hospice organizations can facilitate access to hospice teams who can provide clear guidance on whether to treat-in-place with follow-up care or to transport hospice patients to the hospital.

EMS medical directors and local hospice organizations should collaborate to perform needs assessments of hospice patient EMS utilization.

EMS medical directors should consider including a focus on EMS care of hospice patients as part of their overall quality management program(s). Ideally these efforts should be collaborative with local hospice agencies in order to facilitate meaningful process improvement strategies that include both EMS and hospice stakeholders.

Reimbursement programs should reasonably compensate EMS agencies for scene treatment in place, as well as transport to alternative destinations such as in-patient hospice facilities.

Introduction

The emergency medical services (EMS) system was historically designed for resuscitation and transportation of critically ill patients (Citation1). However, invasive and aggressive life-sustaining care is not always appropriate for patients with serious illness, particularly those enrolled in hospice.

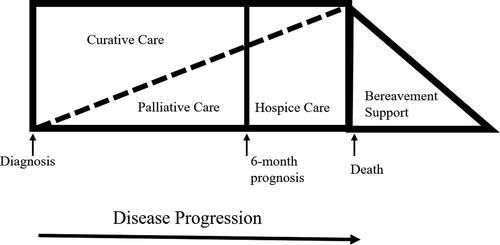

Hospice, a model for compassionate care for people facing the end stages of serious illness, provides medical care, pain management, and emotional and spiritual support expressly tailored to the needs and wishes of patients and families (Citation2). Palliative care and hospice share a focus on comfort and symptom management in patients with serious illness; however, adult patients receiving palliative services may simultaneously pursue curative treatment options, whereas these interventions are not consistent with hospice philosophy (). Although hospice overlaps significantly with palliative care, the focus of this joint position statement and resource document is limited to adult patients enrolled in hospice care.

Figure 1. Continuum of care (Citation41).

Since hospice treatment priorities differ from historical EMS goals of care, EMS care of hospice patients may require different interventions and clinical approaches than those defined in typical 9-1-1 clinical protocols. Unfortunately, there is a paucity of research and evidence to help define best practices for the EMS approach to hospice patients. In order to improve the care EMS systems provide to hospice patients, the National Association of EMS Physicians (NAEMSP) and American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine (AAHPM) have collaborated to perform a structured review of literature germane to EMS and hospice to inform the development of expert consensus recommendations supported by a summary of existing literature. These recommendations and supporting evidence are presented in this joint position statement and resource document.

Background about Hospice

In the United States, 1.6 million patients are enrolled in hospice annually. Patients are eligible for hospice services when they have a terminal diagnosis and an anticipated life expectancy of less than 6 months (Citation2). In 1982, Congress included a provision to create a Medicare hospice benefit, which has since become the standard for the provision of hospice care services. Hospice is a unique Medicare Part A benefit that pays for all associated costs of enrollees including staff, services, and equipment (e.g., medications, durable medical equipment) (Citation3–5). Hospice addresses physical, emotional, and spiritual distress for patients and caregivers. To achieve this whole-person support, hospice is provided by interdisciplinary teams typically including physicians, nurses, hospice aides, social workers, and bereavement and spiritual counselors. Hospice services also include use of durable medical equipment and medications for alleviation of pain and other symptoms associated with the patient’s underlying diagnosis. Though hospice care is usually focused on providing care outside of the hospital, hospice may also include short-term inpatient care when pain or symptoms become too difficult to manage at home or caregivers need respite. See for an incomplete list of example Medicare hospice benefits.

Table 1. Example of medicare hospice benefitsTable Footnote* (Citation42).

The most common diagnoses for hospice patients include dementia, pulmonary disease, cardiovascular disease, and cancer. The majority of hospice care is provided in private homes (51.5%), followed by nursing facilities (17.4%) (Citation2). Research has demonstrated that patients who receive hospice receive care that results in better symptom management, and palliative care services have demonstrated higher quality of life, leading to stabilization of the condition and prolonged survival (Citation6).

Although hospice care usually attempts to reduce the use of emergency care, sometimes EMS is called by the patient, family members, or hospice clinicians to assist in the care of hospice patients. Though the goal of hospice is to provide care for the patient where he or she resides, sometimes hospice clinicians are unable to manage certain aspects of a patient’s care in the residence and the patient may benefit from transfer to a hospital for symptom stabilization or care of injuries or illnesses that are not related to the patient’s hospice diagnosis (Citation3, Citation7). For example, if a hospice patient experiences a fall and sustains a large laceration or possible wrist fracture, he or she may need transport to a hospital for management of those acute conditions. Additionally, although hospice care primarily targets interventions focused on patient comfort, decisions are ultimately driven by the patient and family and what they feel capable of managing in the home. There are some scenarios where invasive treatment and transportation may be appropriate; however, when considering these interventions, the focus should be on what is in the best interest of the individual patient including respecting his or her overall care priorities.

Methods

To inform this position statement and resource document, we performed a structured rapid review of the literature relevant to EMS care of hospice patients. Structured rapid reviews provide a streamlined approach to synthesize evidence, based on the principles of a systematic review of the literature, albeit simplified, to produce information in a timely manner (Citation8). We searched PubMed (via National Library of Medicine) for articles published before June 2022 using the keywords [‘EMS’ OR ‘Prehospital’] AND ‘Hospice’. Non-English publications were excluded. The strategy identified 78 articles available for screening. We reviewed titles and abstracts relevant to hospice patients in the EMS setting, resulting in 23 articles for consideration by all authors to inform this position statement and resource document. Additional publications were identified by the authors, including through bibliography searches.

Discussion

Hospice Patients and 9-1-1

EMS clinicians often encounter hospice patients. In one survey of EMS clinicians in Michigan, over 96% reported encountering hospice patients, and the majority (66%) reported more than 10 professional encounters with hospice patients (Citation9). Similar survey results were seen from EMS clinicians in Georgia (Citation10). In an observational study of Alameda County (California) EMS response calls, 0.2% of calls were identified by EMS as hospice patients, 87.6% of whom were transported to the hospital. The frequency of calls involving hospice patients is likely underreported given methodological limitations of identifying hospice patients in the EMS system using electronic patient care report queries. In addition, there may be tremendous variation based on community demographics and local hospice involvement/enrollment. A qualitative study also performed in Alameda County found that paramedics who worked in communities with older patients with robust access to health care routinely saw patients enrolled in hospice. In contrast, paramedics saw fewer hospice patients in neighboring communities that may be younger and/or have less access to care (Citation11).

EMS clinicians can find interactions with hospice patients clinically and ethically challenging. One mixed methods study of EMS clinicians following encounters with hospice patients identified family-related challenges and the need for more EMS clinician education about end-of-life care as common themes (Citation10). A different qualitative study found that EMS clinicians reported responding to grief and emotion after death, and in-the-moment decision-making after acute clinical changes, as particularly challenging (Citation11).

Even if hospice patients and their families are logistically aware and prepared for death in the home, they may call 9-1-1 for a variety of reasons. In a qualitative interview of hospice caregivers, over half reported calling 9-1-1 before calling their hospice clinicians (Citation12). Common themes identified from caregivers who called 9-1-1 included an incomplete understanding of hospice care, the presence of distressing symptoms, caregiver reluctance to give morphine, faster 9-1-1 response compared to hospice clinician response, and families’ difficulty accepting patient mortality (Citation13). Though many reasons for calling 9-1-1 are justified, delivery of compassionate care and aggressive symptom management delivered by EMS personnel does not obligate transport to a hospital.

When EMS clinicians encounter patients enrolled in hospice, advance care planning documents such as physician orders for life sustaining treatment (POLST) can be helpful for guiding care and making treatment decisions. A meta-analysis of POLST utilization demonstrated that treatment limitations on a POLST form were associated with decreased in-hospital death and reduced amounts of high-intensity treatment, particularly in the EMS setting (Citation14). However surveys of EMS clinicians in several states also demonstrated confusion regarding POLST interpretation and application, particularly when patients were not in cardiopulmonary arrest (Citation15). Misinterpreting the POLST can result in EMS clinicians providing or withholding interventions in a manner that is discordant with the patient’s care goals. It is important to note that although most hospice patients will have a do not resuscitate (DNR)/do not attempt resuscitation (DNAR) order, such orders are not required for hospice enrollment. It is critical for EMS clinicians to recognize that although hospice patients usually have advanced care documents indicating DNR/DNAR status, DNR/DNAR does not mean the EMS clinician should not provide appropriate symptom-focused care. This is especially true in the initial phase of hospice care when patients and families may have a difficult time accepting the terminal nature of the disease (Citation3). Although the topic of interpreting advance care planning documents such as POLSTs and DNR/DNAR forms is relevant to EMS care of hospice patients, a robust discussion of these documents is outside the scope of this resource document.

End of Life Care Training for EMS

In hospital-based emergency medicine, primary palliative care skills including hospice knowledge, referral, and patient management has become a growing part of the emergency medicine educational curriculum (Citation16–21), and the focus of structured improvement efforts (Citation22, Citation23). It is important that EMS physicians are familiar with these skills and knowledge base, if it is expected that EMS clinicians should be as well. In addition, EMS might be able to translate and apply emergency medicine educational curricula and structured improvement experiences to EMS.

Despite the frequency of EMS clinician encounters with hospice patients, there is a dearth of formal training for EMS clinicians. In Michigan, only 24% of EMS clinicians reported formal hospice education (Citation9). Although variable, there is also minimal initial or continuing EMS education on the related subjects of palliative care, death notification, advance care planning documents/POLST, and communication training. Current National EMS Education Standards outline the following standard for hospice patient care: emergency medical technicians(EMT) should have a basic knowledge and be able to provide basic care, advanced EMT should have a foundational and fundamental depth of knowledge, and paramedics should have a comprehensive and complex breadth of knowledge of pathophysiology and psychosocial needs and be able to implement a treatment/disposition (Citation24).

With the exception of some mobile integrated health programs, there is limited research on effective EMS hospice curriculum (Citation25). However, one area relevant to the care of hospice patients that has been studied in the EMS setting is death notification. In one study a structured framework for delivering death notification (the GRIEV_ING protocol, see ) successfully improved confidence and competence of EMS clinicians performing death notifications (Citation26). Moreover, training in delivering death notification is associated with 29% reduced risk of burnout (Citation27). When empowered with the skills to care for patients and their families near the end of life, potentially distressing situations can become professionally rewarding interactions. Education priorities should include communications curriculum development and research into the effectiveness of different types of training formats (e.g., simulation based, synchronous versus asynchronous), frequency and timing of training, and effect on EMS clinicians and patients’ families, should be a research priority.

Table 2. Modified GRIEV_ING Protocol (Citation26).

Table 3. Recommended features of hospice EMS protocols.

EMS Hospice Protocols

Many of the clinical aspects of hospice care focus on symptom management and use medications and skills that are already part of routine EMS training including use of opioid analgesics for pain control, antiemetics for nausea reduction, suctioning of oral secretions, delivering supplemental oxygen, and repositioning patients for comfort. However, the application of these interventions to hospice patients are often not fully covered by typical 9-1-1 protocols that guide care for non-hospice patients. See for recommended features of hospice EMS protocols.

When combined with end-of-life skills training, the creation of specific EMS-focused hospice protocols can provide EMS clinicians with guidance regarding the appropriateness of providing treatment in place without transport vs. providing treatment on scene followed by care in transit if/when transport to a hospital is reasonable. When EMS medical directors develop such protocols, they should engage local hospice clinicians and services. Hospice clinicians are familiar with which symptom management techniques may work best for hospice patients and they can help inform whether attempting treatment in place instead of treatment and transportation to the hospital would best serve the patient’s needs. EMS medical directors can contribute knowledge about local scope of practice limitations for the EMS clinicians they oversee and can help navigate how those limitations intersect with the symptom management techniques recommended by the hospice clinicians.

EMS-focused hospice care guidelines have been developed at several jurisdictional levels.

In a recent review of 37 states with statewide EMS protocols, only four states (Maine, New Hampshire, North Carolina, and Vermont) had specific EMS protocols for hospice patients (Citation28). Many of these protocols outline specific medications or treatments for symptom management near the end of life. Some of these specific hospice protocols recommend or require contacting the local hospice agencies. Hospice agencies provide 24-hour phone support for patients and when local hospice agencies are contacted, they can help make treatment recommendations for symptom control, communicate with family about their end of life concerns, and facilitate a treatment plan collaboratively with EMS whether that be treat in place, assess and refer to hospice, or transportation to the hospital. Recent National Model EMS Clinical Guidelines v3.0 does include a sample guideline addressing “End of Life Care/Hospice Care”, however contacting hospice organizations is not included. We recommend that local hospice EMS protocols should be developed collaboratively with local hospice services to ensure they reflect local EMS scope of practice and hospice stakeholder care preferences (Citation29).

Innovation and Collaboration with Hospice Programs

To address the gaps in care of hospice patients, several EMS systems have collaborated with local hospice agencies and piloted mobile integrated health programs specifically for hospice patients. Such programs provide EMS clinicians with additional hospice, end-of-life care, and communications training. Several examples exist of the tangible benefits of such collaborative programs. Following adoption of such a mobile integrated health program, Ventura County, CA reduced transportation of hospice patients to the hospital from 80% to 25% (Citation25). A similar program in New York City demonstrated that when specially trained hospice paramedics were on scene, 62% of patients were treated in place, 17% were transported to inpatient hospice, and only 21% were transported to the hospital (Citation32). In Fort Worth, TX, a hospice agency subcontracted with an EMS agency on a per-member-per-month basis to respond to their patients in distress, resulting in a low voluntary hospice disenrollment rate of 10% (Citation33). In Florida, a mobile integrated health program trained paramedics to assess hospice eligibility and conduct an introductory conversation to explore hospice interest. The program resulted in a 96% reduction in EMS resource utilization (Citation34). In Canada, where hospice is structured and funded differently than in the United States, there has been a successful national campaign to build a paramedic hospice palliative care program. This novel program included a new clinical practice guideline, and a database to manage and share goals of care and palliative care training. A key success to the program has been adapting training to local needs (Citation35, Citation36).

Local Gap Assessments and Quality Management Programs

EMS and hospice agencies share the same patients and often the same common goals of reducing unnecessary resource utilization and respecting patient preferences for care. EMS medical directors are encouraged to collaborate with local hospice agencies to perform needs assessments and develop quality management programs that include a focus on the EMS care delivered to hospice patients. Needs assessments may include identifying EMS clinician knowledge gaps regarding hospice services, palliative therapies, advance care planning documents, and/or communication training. Alternatively, a needs assessment might determine how hospice patients are identified by EMS and determining the frequency of and reasons for transport to a hospital. A quality management program that follows the cycle of “plan, do, study, and act” can document and guide collaborative progress (Citation37). Additionally, a quality management program that assesses EMS-hospice care using benchmarking strategies linked to National EMS Information Systems data elements, such as those benchmarking metrics developed by the National EMS Quality Alliance, may be of use (Citation38, Citation39).

Future Directions for EMS Care of Hospice Patients

In order for EMS clinicians to best care for hospice patients a paradigm shift is required from the EMS systems’ historical design for resuscitation and transportation. Unfortunately, the traditional model of EMS reimbursement incentivizes transport of the patient even if transport to the hospital is not in the best interest of the patient. The National EMS Agenda for 2050 calls for “reimbursement policies that incentivize EMS clinicians to provide appropriate, safest, and cost-effective care (Citation40).” There are ongoing efforts to improve EMS system reimbursement to become more patient-centered (such as ET3) and may allow for transportation to alternate destinations (e.g., inpatient hospice units) (Citation36). EMS system reimbursement should encourage patient-centered care for those patients who prefer to die at home and should value the nuanced end-of-life care skills that EMS clinicians must have to care for hospice patients.

Conclusion

EMS care of hospice patients needs to be supported by education of EMS and hospice clinicians alike, collaborative development of specific hospice-focused care protocols, integration of EMS with the hospice infrastructure, and development of reimbursement strategies for EMS care that are not based on transport of the hospice patient. Additional research focusing on development of clinician end-of-life communication skills, assessment of clinician understanding and application of advance care planning documents, development of quality management practices that seek to improve patient-centered care outcomes, and models of non-transport-based financial compensation for EMS agencies will help address current knowledge gaps. EMS-based treatment of hospice patients should emphasize demonstration of compassion during moments of acute crisis, distress, and grief as well as respect for the patients’ care preferences during the natural process of death.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Krohmer JR. History of emergency medical services. In: Cone DC, Brice JH, Delbridge TR, Myers JB, editors. Emergency medical services: Clinical practice and systems oversight. 3rd ed. West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2021.

- National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. NHPCO Facts and Figures; 2020. Edition. https://www.nhpco.org/wp-content/uploads/NHPCO-Facts-Figures-2020-edition.pdf.

- Lamba S, Quest TE. Hospice care and the emergency department: rules, regulations, and referrals. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;57(3):282–90. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.06.569.

- Hoyer T. A history of the Medicare hospice benefit. Hosp J. 1998;13(1–2):61–9. doi:10.1080/0742-969x.1998.11882888.

- Correoso-Thomas LJ, Cote T, Cote TR. Hospice medical director manual. 3rd ed. Chicago, IL: American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine; 2016.

- Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, Gallagher ER, Admane S, Jackson VA, Dahlin CM, Blinderman CD, Jacobsen J, Pirl WF, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):733–42. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1000678.

- Evans WG, Cutson TM, Steinhauser KE, Tulsky JA. Is there no place like home? Caregivers recall reasons for and experience upon transfer from home hospice to inpatient facilities. J Palliat Med. 2006;9(1):100–10. doi:10.1089/jpm.2006.9.100.

- Khangura S, Konnyu K, Cushman R, Grimshaw J, Moher D. Evidence summaries: the evolution of a rapid review approach. Syst Rev. 2012;1:10. doi:10.1186/2046-4053-1-10.

- Wenger A, Potilechio M, Redinger K, Billian J, Aguilar J, Mastenbrook J. Care for a dying patient: EMS perspectives on caring for hospice patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2022;64(2):e71–e76. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2022.04.175.

- Barnette Donnelly C, Armstrong KA, Perkins MM, Moulia D, Quest TE, Yancey AH. Emergency medical services provider experiences of hospice care. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2018;22(2):237–43. doi:10.1080/10903127.2017.1358781.

- Breyre AM, Benesch T, Glomb NW, Sporer KA, Anderson WG. EMS experience caring and communicating with patients and families with a life-limiting-illness. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2022;26(5):708–15. doi:10.1080/10903127.2021.1994674.

- Phongtankuel V, Paustian S, Reid MC, Finley A, Martin A, Delfs J, Baughn R, Adelman RD. Events leading to hospital-related disenrollment of home hospice patients: A study of primary caregivers’ perspectives. J Palliat Med. 2017;20(3):260–5. doi:10.1089/jpm.2015.0550.

- Phongtankuel V, Scherban BA, Reid MC, Finley A, Martin A, Dennis J, Adelman RD. Why do home hospice patients return to the hospital? a study of hospice provider perspectives. J Palliat Med. 2016;19(1):51–6. doi:10.1089/jpm.2015.0178.

- Vranas KC, Plinke W, Bourne D, Kansagara D, Lee RY, Kross EK, Slatore CG, Sullivan DR. The influence of POLST on treatment intensity at the end of life: A systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69(12):3661–74. doi:10.1111/jgs.17447.

- Mirarchi FL, Cammarata C, Zerkle SW, Cooney TE, Chenault J, Basnak D. TRIAD VII: do prehospital providers understand Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment documents? J Patient Saf. 2015;11(1):9–17. doi:10.1097/PTS.0000000000000164.

- Shoenberger J, Lamba S, Goett R, DeSandre P, Aberger K, Bigelow S, Brandtman T, Chan GK, Zalenski R, Wang D, et al. Development of hospice and palliative medicine knowledge and skills for emergency medicine residents: Using the accreditation council for graduate medical education milestone framework. AEM Educ Train. 2018;2(2):130–45. doi:10.1002/aet2.10088.

- Chung FR, Turecamo S, Cuthel AM, Grudzen CR, Investigators P-E Effectiveness and reach of the primary palliative care for emergency medicine (PRIM-ER) pilot study: a qualitative analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(2):296–304. doi:10.1007/s11606-020-06302-2.

- Grudzen CR, Brody AA, Chung FR, Cuthel AM, Mann D, McQuilkin JA, Rubin AL, Swartz J, Tan A, Goldfeld KS, PRIM-ER Investigators, et al. Primary palliative care for emergency medicine (PRIM-ER): Protocol for a pragmatic, cluster-randomised, stepped wedge design to test the effectiveness of primary palliative care education, training and technical support for emergency medicine. BMJ Open. 2019;9(7):e030099. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030099.

- Friedrichsdorf SJ, Remke S, Hauser J, Foster L, Postier A, Kolste A, Wolfe J. Development of a pediatric palliative care curriculum and dissemination model: education in palliative and end-of-life care (EPEC) pediatrics. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2019;58(4):707–20 e3. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2019.06.008.

- Hauser JM, Preodor M, Roman E, Jarvis DM, Emanuel L. The evolution and dissemination of the education in palliative and end-of-life care program. J Palliat Med. 2015;18(9):765–70. doi:10.1089/jpm.2014.0396.

- Grudzen CR, Emlet LL, Kuntz J, Shreves A, Zimny E, Gang M, Schaulis M, Schmidt S, Isaacs E, Arnold R, et al. EM Talk: communication skills training for emergency medicine patients with serious illness. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2016;6(2):219–24. doi:10.1136/bmjspcare-2015-000993.

- Lamba S, DeSandre PL, Todd KH, Bryant EN, Chan GK, Grudzen CR, Weissman DE, Quest TE, Improving Palliative Care in Emergency Medicine Board. Integration of palliative care into emergency medicine: the Improving Palliative Care in Emergency Medicine (IPAL-EM) collaboration. J Emerg Med. 2014;46(2):264–70. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2013.08.087.

- Tan A, Durbin M, Chung FR, Rubin AL, Cuthel AM, McQuilkin JA, Modrek AS, Jamin C, Gavin N, Mann D, Group Authorship: Corita R. Grudzen on behalf of the PRIM-ER Clinical Informatics Advisory Board, et al. Design and implementation of a clinical decision support tool for primary palliative Care for Emergency Medicine (PRIM-ER). BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2020;20(1):13. doi:10.1186/s12911-020-1021-7.

- National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. National Emergency Medical Services Education Standards; 2021. [accessed 2022 Oct 20]. https://www.ems.gov/pdf/EMS_Education%20Standards_2021_FNL.pdf.

- Breyre A, Taigman M, Salvucci A, Sporer K. Effect of a mobile integrated hospice healthcare program on emergency medical services transport to the emergency department. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2022;26(3):364–9. doi:10.1080/10903127.2021.1900474.

- Hobgood C, Mathew D, Woodyard DJ, Shofer FS, Brice JH. Death in the field: teaching paramedics to deliver effective death notifications using the educational intervention "GRIEV_ING. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2013;17(4):501–10. doi:10.3109/10903127.2013.804135.

- Campos A, Ernest EV, Cash RE, Rivard MK, Panchal AR, Clemency BM, et al. The association of death notification and related training with burnout among emergency medical services professionals. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2021;25(4):539–48. doi:10.1080/10903127.2020.1785599.

- Hanson KC, Kramp D. Hospice patient and end-of-life care focused emergency medical services protocols: Lessons learned form a national review in the United States. Prehospital Emerg Care (under Review). 2022.

- National Association of State EMS Officials. National Model EMS Clinical Guidelines v3.0; 2022. [accessed 2022 Nov 1]. https://nasemso.org/wp-content/uploads/National-Model-EMS-Clinical-Guidelines_2022.pdf.

- Grudzen CR, Koenig WJ, Hoffman JR, Boscardin WJ, Lorenz KA, Asch SM. Potential impact of a verbal prehospital DNR policy. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2009;13(2):169–72. doi:10.1080/10903120802471923.

- Mengual RP, Feldman MJ, Jones GR. Implementation of a novel prehospital advance directive protocol in southeastern Ontario. CJEM. 2007;9(4):250–9. doi:10.1017/s148180350001513x.

- Ramjit A, et al. Hospice at Home: Paramedics as part of the team. Poster Presentation American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine; 2022.

- Anastasio M. Mobile integrated healthcare Part 4: Integrating home care, hospice & EMS. EMS World. 2015.

- Antevy P, Scheppke K, Cardona J, Toolan S, Maraj S, Babinec F, et al. Reducing 9-1-1 over-utilization through a targeted community paramedic hospice referral program. Washington (DC): Abstract for National Emergency Medical Services Physician Scientific Assesmbly; 2018.

- Carter AJE, Arab M, Harrison M, Goldstein J, Stewart B, Lecours M, Sullivan J, Villard C, Crowell W, Houde K, et al. Paramedics providing palliative care at home: A mixed-methods exploration of patient and family satisfaction and paramedic comfort and confidence. CJEM. 2019;21(4):513–22. doi:10.1017/cem.2018.497.

- Carter AJE, Harrison M, Kryworuchko J, Kekwaletswe T, Wong ST, Goldstein J, et al. Essential elements to implementing a paramedic palliative model of care: An application of the consolidated framework for implementation research. J Palliat Med. 2022;25(9):1345–54. doi:10.1089/jpm.2021.0459.

- Defining quality in EMS. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2018;22(6):782–3.

- National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. National emergency medical services information system (NEMSIS); 2022. https://nemsis.org.

- National EMS Quality Alliance (NEMSQA). 2022. [10/21/2022]. http://www.nemsqa.org.

- EMS Agenda 2050 Technical Expert Panel. EMS Agenda 2050: A people-centered vision for the future of emergency medical services. In: Administration NHTS. editor. Washington (DC): National Highway Traffic Safety Administration; 2019. [accessed 2022 Oct 1]. https://www.ems.gov/pdf/EMS-Agenda-2050.pdf

- National Quality Forum. A national framework and preferred practices for palliative and hospice care quality: A consensus report; 2006.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare hospice benefits. In: Services USDoHaH. editor. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2022. [accessed 2022 Oct 24]. https://www.medicare.gov/Pubs/pdf/02154-medicare-hospice-benefits.pdf