ABSTRACT

Improving health and safety in our communities requires deliberate focus and commitment to equity. Inequities are differences in access, treatment, and outcomes between individuals and across populations that are systemic, avoidable, and unjust. Within health care in general, and Emergency Medical Services (EMS) in particular, there are demonstrated inequities in the quality of care provided to patients based on a number of characteristics linked to discrimination, exclusion, or bias. Given the critical role that EMS plays within the health care system, it is imperative that EMS systems reduce inequities by delivering evidence-based, high-quality care for the communities and patients we serve.

To achieve equity in EMS care delivery and patient outcomes, the National Association of EMS Physicians recommends that EMS systems and agencies:

make health equity a strategic priority and commit to improving equity at all levels.

assess and monitor clinical and safety quality measures through the lens of inequities as an integrated part of the quality management process.

ensure that data elements are structured to enable equity analysis at every level and routinely evaluate data for limitations hindering equity analysis and improvement.

involve patients and community stakeholders in determining data ownership and stewardship to ensure its ongoing evolution and fitness for use for measuring care inequities.

address biases as they translate into the quality of care and standards of respect for patients.

pursue equity through a framework rooted in the principles of improvement science.

Disclaimer

As a service to authors and researchers we are providing this version of an accepted manuscript (AM). Copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proofs will be undertaken on this manuscript before final publication of the Version of Record (VoR). During production and pre-press, errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal relate to these versions also.INTRODUCTION

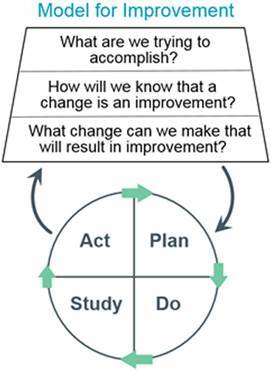

While there have been several publications describing the extent of inequities in Emergency Medical Services (EMS) care, there is little current evidence on effective strategies to address these gaps (1). The demonstrated pervasiveness of treatment inequities within prehospital care demands dedicated quality improvement efforts to reduce them. Using traditional methods of quality assurance that rely on chart review and individual clinician feedback (2) is insufficient to address system-based inequities. Making changes that result in improvement will require a process rooted in Improvement Science-based quality management systems that monitor and measurably improve the quality of care provided (3). The Model for Improvement (Figure 1) is one such framework that has been used to make demonstrable improvements in health care systems, including in EMS (4).

The Model for Improvement consists of three questions and a cycle of small-scale tests of change. The three questions focus quality improvement on Aim, Measurement and Change Ideas:

1. Aim: What are we trying to accomplish?

2. Measurement: How will we know that a change is an improvement?

3. Change Ideas: What change can we make that will result in improvement?

Change ideas are subsequently trialed through small-scale tests of change known as Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) Cycles, and successful changes are implemented system-wide.

Using the Model for Improvement as a framework, this document aims to provide a roadmap for EMS agencies to integrate a focus on equity into their existing quality management process with the explicit aim of achieving health care equity.

What are we trying to accomplish? Health equity in EMS

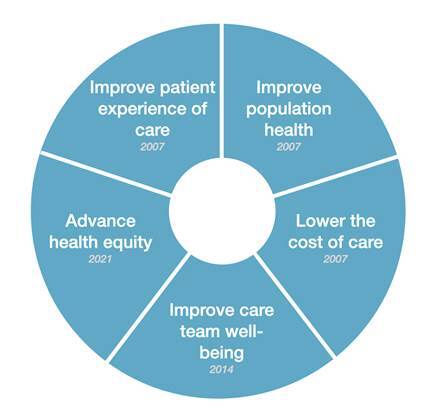

More than 20 years ago, the Institute of Medicine (now the National Academy of Medicine; NAM) called for health care to be safe, effective, patient-centered, timely, efficient, and equitable (5). While many quality improvement efforts have focused on the first five of these aims, little progress has been made in the provision of equitable care (6). Not only has progress on health care equity been elusive, but also some improvement efforts worsened disparities (7-9). This led the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) to add health care equity to their quadruple aim to form the quintuple aim in 2022, as improvement without equity is a “hollow victory” (Figure 2) (10). In EMS Agenda 2050, the EMS community also identified social equitability of care as an explicit aim (11).

Although often used interchangeably, the terms “disparities” and “inequities” have distinct meanings in health care. Health care disparity is defined as the “difference in health outcomes between groups within a population,” unjust or not. Health inequity, on the other hand, denotes differences in health outcomes that are “systematic, avoidable, and unjust.” Health equity refers to all populations having a fair opportunity to attain their full health potential and, more pragmatically, no one being disadvantaged from achieving this potential (6, 12, 13).

While there are some mixed results, the substantial weight of the evidence indicates that patients who are part of marginalized populations (i.e., racial and ethnic minorities, economically-disadvantaged, female, homosexual, transgender, immigrant, persons with language barriers, etc.) persistently receive inequitable care compared to white, cis-gendered, heterosexual men. This inequity is not restricted to a small corner of the health care system and has been observed and demonstrated in many areas of medicine, including cardiovascular care, oncology diagnostics and treatment, HIV treatment, diabetes and end-stage renal disease management, pain management, pediatric care, mental health services, and emergency care (9, 14-21). Therefore, it should come as no surprise that health care inequities also affect patients who interact with EMS systems.

A recent scoping review identified 145 articles that reported inequitable care for marginalized communities in every phase of the EMS patient encounter, including access, pre-arrival care, diagnosis, treatment, and transport decisions (1). Specific and noteworthy inequities include: female OHCA patients were less likely to have an AED applied or used prior to EMS arrival; bystander CPR was performed more often in White neighborhoods than non-White neighborhoods; racial minorities received sub-standard treatment for pain; Black patients with trauma were less likely to be transported overall, and, when transported, were more likely to be transported to a safety net hospital; and female patients with acute coronary syndrome or stroke experienced longer on-scene times compared to clinically similar male patients.

Deciding where to start the process of making changes to advance health equity represents an important challenge for EMS systems. The temptation may be to start with patients who have less complex needs as an easier way to begin the process, but this can have the paradoxical effect of worsening inequities. Improvement strategies that are effective for more advantaged populations are not necessarily effective for less advantaged populations (6). As recommended by the IHI, “Improvement work needs to be designed from the start to meet the needs of marginalized populations - focused, targeted, and culturally tailored” (6). In addition, any improvement work to advance health equity must engage the population affected by the change at all stages, which has been summarized with the simple mantra of “Do nothing for me without me” (22). Achieving health equity will require explicit measurement of and focus on reduction of inequity that should be integrated into the overall quality management system like it has been integrated into the IHI quintuple aim.

How will we know that change is an improvement? Measuring EMS inequities

Measurement is a cornerstone of meaningful improvement. The goal of measuring care inequities is not an end itself but rather merely the beginning of the improvement process. Closing gaps in health equity requires first understanding where disparities exist. Without this deliberate focus, efforts to improve care can unintentionally worsen the gaps (23, 24). For example, it is not uncommon that improvement efforts work at a faster rate in a group that was already experiencing better outcomes than others. Simply focusing on the overall population can hide the fact that inequities for some subpopulations become worse than before. To avoid unintentionally worsening outcomes, measures should be stratified to provide detailed insight into comparisons between groups.

Stratifying measures to quantify inequities requires accurate collection of patient characteristics, such as but not limited to race, ethnicity, and language (also known as REaL data (25)); and sexual orientation and gender identity (also known as SOGI data). Effectively collecting and analyzing these data in EMS represents important challenges. In general, an estimated 10-20% of EMS records are lacking information about the patient’s race and ethnicity (26-28); this information is less likely to be documented in patients of color, male patients, and younger patients (29). When this information is documented, there is a lack of consistency with how it is acquired. For instance, prehospital patient care report datasets do not indicate whether patient sociodemographic information is self-reported or based on EMS clinician perception (30). Clinician documentation of patient race has shown high rates of correlation with hospital documentation, though hospital documentation does not always match with patient self-report and may underrepresent patients belonging to racial and ethnic minorities (26, 28, 31). This is not to say that clinician-reported race and ethnicity data have no value. Given that race and ethnicity largely represent social constructs rather than biological differences, recorded clinician perception can provide important insight into inequities, particularly as they relate to biases. Nevertheless, understanding the needs of racial and ethnic groups within communities is better served through patient self-identification.

Many patient characteristics essential for measuring disparities are not consistently collected by EMS clinicians, as these elements are not part of the National EMS Information System (NEMSIS) data standard. For example, while language may be indicated as a barrier to care, there is no national data element to routinely collect the patient’s preferred language or to indicate professional medical interpreter use. While gender recording became more inclusive with the addition of the recently released values in NEMSIS version 3.5, there is not a national data element to capture sexual orientation. There is a need for improved measures and data collection within the NEMSIS data standard for marginalized populations in order to improve health equity measures.

Structural (or social) drivers of health (SDH) determine whether the resources necessary for optimal health are distributed equitably, and understanding the SDH that exist within a population is a key component to diminishing health care inequities. Research in EMS in the area of SDH has been impeded by the lack of national standards for collecting data relating to SDH. Several expert groups, including the NAM and the National Quality Forum, have noted that a lack of standardization is an obstacle to both scaling and studying SDH interventions. In an effort to facilitate the systematic collection, standardization, and interoperability of SDH data, NAM published two reports that outline the recommendations for capturing and measuring SDH in the EHR (32). This approach should be a consideration for EMS. Currently, assessing structural drivers of health within EMS medical records can be accomplished through rudimentary text mining, which can also aid in increasing health equity (33, 34), but text mining is not enough to gain quality data on this topic.

Collecting patient sociodemographic characteristics must be done in a patient-centered manner that minimizes patient burden and potential harms. In the hospital setting, the “We Ask Because We Care” approach has shown success across multiple facilities (35). While no standard best practice for collecting prehospital patient information has been established, simply enabling the electronic health record to allow entry of this information is insufficient. Collecting patient information related to marginalized groups requires careful examination of confidentiality, information collection standardization, the method of data collection, and cultural competency and training (36, 37). In the emergency department (ED), sexual and gender minority patients reported greater comfort and improved communication when information was collected through non-verbal self-report (38). Reducing the number of times patients are asked for personal information represents another way to lower the burden and risk to patients. Whereas hospital systems often have patient portals where patient information can be accessed without the need to re-ask the patient, EMS records are often episodic. Advances in data interoperability and exchange of data with hospital systems may potentially increase completeness of documentation related to patient characteristics without placing additional burden on the patient. Accuracy, completeness, and timeliness of patient sociodemographic data should be assessed and validated on a continual basis (39).

Examination for inequities should be built into existing EMS quality measures rather than treated as a separate area for improvement. Historically, there has been much debate surrounding the definition of performance measures for EMS. Early measures were heavily focused on operational aspects that may not directly relate to the care provided or patient outcome (40). As a result, experts in EMS medicine began developing clinical quality measures (41). Further national quality measures for EMS systems were first developed beginning in 2002 with the EMS Compass program funded by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) Office of EMS and directed by the National Association of State EMS Officials (NASEMSO). This task force, along with several stakeholders, developed standardized clinical and non-clinical performance measures for EMS systems that reflected data fields used within the NEMSIS dataset. The work completed by EMS Compass was then transitioned to the National EMS Quality Alliance (NEMSQA) in 2018. Further work has since been done to grow the number of quality measures to assess functionality (42). Currently, the suite of national EMS quality measures includes the appropriate and timely treatment and transport of pediatric respiratory distress, hypoglycemia, seizure, stroke, trauma, and pain, among others (Online Supplemental Table). This list of national quality measures is by no means exhaustive. For example, no measures in the national set address access to care, which has a major effect on patient outcomes for time-sensitive conditions like ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) and stroke. Emergency Medical Services systems should develop quality measures that reflect the most current evidence and the community need.

As part of EMS quality management programs, performance measures should be routinely examined by patient subgroups to identify and understand actionable drivers underlying inequities. When it comes to stratifying quality measures into patient subgroups, pairwise comparisons are often a starting point, but these comparisons do not capture the intersectionality of characteristics (e.g., a patient who is Hispanic, Black, female, low-income, and underinsured). EMS systems should incorporate a structured process for stratifying quality measures using REaL and SOGI data into their normal operations of quality management programs and ensure commitment from leadership so that inequities can be targeted and addressed (43).

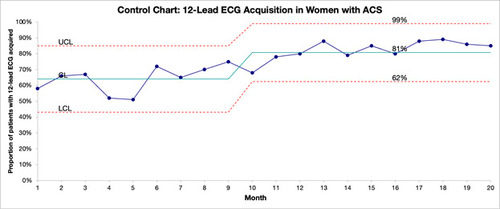

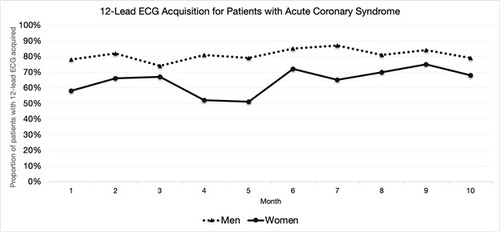

Emergency Medical Services systems should track the effects of their improvement strategies for health equity over time. Plotting data over time using a run chart is a simple and effective way to visualize inequities in care (Figure 3). Focusing on the subgroup targeted for improvement and adding limits is an effective way to evaluate whether the changes an organization makes are having the intended effect on inequities (Figure 4). Annotating these charts with changes as they are made provides even more information on how the interventions are working or not working to generate improvement. A well-defined measurement strategy and visualization of data over time are key to quantifying current inequities, identifying when improvement occurs, and ensuring that improvement sustains over time.

What changes can we make that will result in improvement? Designing and testing change packages to close equity gaps

While EMS organizations alone do not have the power to improve all of the social drivers that lead to outcome disparities, these systems can address inequities that occur at the point of care and can impact many of the drivers that lead to these inequities (6, 44). The central law of improvement is that “every system is perfectly designed to achieve the results it achieves” (45). This means that decreasing health inequities will require more than superficial or reactive changes that keep the system running at its current level of performance; it will require tested changes that fundamentally alter how the system works (4). When developing change, the focus should be on changes that alter the actual workflow process or actively interrupt behaviors and existing attitudes. Having an appreciation of the EMS system and its nuances, including what might fuel the process and what may cause friction, is critical to making meaningful change.

While change ideas that involve training or education can be tempting, they are usually unsuccessful at making sustainable change without further interventions (46, 47). Interventions that are solely based in education are best reserved for when there are known gaps in knowledge, skills, or abilities (46, 47). With regard to care inequities, research suggests that clinician bias plays a role in inequities in patient care and outcomes (48), implying an associated clinician knowledge gap in recognition of how biases and microaggressions (defined in Table 1) impact patient-clinician interactions, treatment decisions, treatment adherence, and patient health outcomes (49-51). Therefore, acknowledgement and comprehension of bias and microaggressions are key components of improvement strategies for equitable patient care and outcomes. Training and educational strategies aimed at measuring (52) and mitigating implicit bias and microaggressions (50) are continuing to be developed, though further research is needed to evaluate the effectiveness and impact of these trainings in clinical care settings and longitudinally upon patient outcomes.

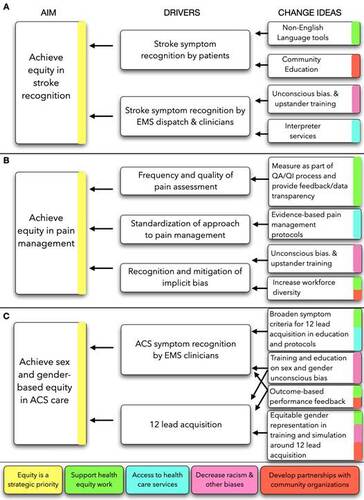

There are a number of approaches to developing change ideas, including detailed analysis of the work process and systems, adapting known good ideas, and creative thinking (4). These approaches include formal tools such as driver diagrams, which illustrate what structures and processes may require change in the system and specific ideas to make those changes (Figure 5) (4, 53). Most importantly, unproven change ideas must be tested through a Plan-Do-Study-Act cycle to determine whether they lead to improvement.

In 2016, the IHI published the white paper, “Achieving Health Equity: A Guide for Health Care Organizations,” which shared a framework for health care organizations to improve health equity in the communities they serve (Table 2) (6). This framework provides a useful starting point around key drivers of achieving health equity, which in turn can be used to develop change ideas for improvement. While a significant amount of work has been done to identify care inequities, there are few if any EMS quality improvement projects effective in reducing or eliminating them. As such, the next section will discuss current knowledge about the drivers of EMS care inequities to provide a starting point - and a call to action - to develop, test, and implement changes that lead to improvement. This discussion takes place through the analysis of three examples: ethnic inequities in stroke care, racial inequities in pain management, and sex and gender-based inequities in assessment of patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS).

Ethnic Inequities in Stroke Care Delivery

In comparison to non-Hispanic White individuals, Mexican American individuals have a higher incidence of both ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke (53). While arrival by EMS is associated with a decrease in time to treatment for patients experiencing stroke (54), Hispanic and Asian patients are less likely to arrive to the ED by EMS (55-58). In part, decreased utilization of EMS for stroke is likely related to inequities in stroke recognition. In one survey of individuals with a previous history of stroke, Hispanic, Asian, Pacific Islander, and Alaska Native respondents were significantly less likely to recognize all five warning signs of stroke and call 9-1-1 as the first action if someone was having a stroke compared to White and Black respondents (59). Moreover, Hispanic patients were less likely to be recognized as having a stroke by EMS (60).

Given the work that has been done in identifying these care inequities, a key focus for improvement in achieving equity in prehospital stroke care is to increase stroke recognition (Figure 5A). Strokes must be recognized by both lay community members and clinicians, giving rise to change ideas such as development of non-English Language tools for community stroke recognition (61), community engagement and education initiatives (62, 63), and EMS commitment to access and use of interpreter services. The compilation of this aim, drivers, and change ideas all build upon the IHI Framework for achieving health equity (Figure 5A).

Reducing Racial Inequities in Pain Management

Racial and ethnic minority patients experience inequities in pain assessment and treatment compared to their White counterparts. Studies have found that Black patients are more likely to be undertreated for pain, receive lower doses of pain medication, and experience longer waiting times for pain relief in EMS settings compared to White, non-Hispanic patients (9, 64, 65). These inequities are not explained by differences in pain severity, patient preferences, or community socioeconomic resources (9), suggesting that racism and bias are drivers of observed inequities in pain management. This is further substantiated by work documenting the persistence of false beliefs among clinicians about biological differences between Black and White individuals as a driver of inaccurate patient assessment and management (66). Therefore, increasing recognition and mitigation of unconscious bias will be an essential component of any improvement effort to reduce inequities in pain management (50). Given knowledge gaps exist regarding implicit and explicit bias, education aimed at teaching skills on how to intervene when witnessing implicit bias or microaggressions that interfere with appropriate care, communication, and treatment of others certainly have an important role in these improvement efforts (67). However, achieving equity will likely require more than education and training alone (50); change ideas integrating measurement and feedback on pain assessment and management, transparency of system performance with respect to equity, and protocolized integration of current evidence-based guidelines on pain management (68) should also be pursued (Figure 5B). Finally, underrepresentation of non-White personnel in the EMS workforce continues to contribute to care inequities (69, 70). Beyond impact on treatments rendered, there may be impact of receiving care from a racially-concordant clinician on expression and perception of pain (71). Therefore, the active pursuit of an EMS workforce that reflects the diversity of the community it serves may further decrease care inequities, including in pain management.

Sex and Gender Inequities in Assessment of Patients with Suspected ACS

Sex and gender-based inequities in ACS care are well documented in the literature. In comparison to male patients, female patients are less likely to be diagnosed with heart disease, less likely to receive standard care once diagnosed, and more likely to experience adverse events or death after diagnosis (72-76). In the prehospital setting, sex and gender-based inequities exist in rates of 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) acquisition, aspirin administration, scene time delay, and dispatch priority (77-82). Hypothesized explanations for cardiac care inequities have historically included both sex- and gender-based differences, where sex refers to a person’s biological make-up and gender encompasses an individual’s self-identity and expression (83). Despite evidence that both sex and gender matter to health outcomes, significant data quality challenges remain that limit sex and gender analysis, not the least of which is the availability and reliability of sex and gender differentiating data (84).

Among the prehospital interventions related to ACS, ECG acquisition is a key step in the diagnostic process, and missed opportunities can delay diagnosis or derail definitive care (85-87). Two of the steps associated with timely ECG acquisition are drivers of missed opportunities for obtaining ECG in female patients specifically: Acute Coronary Syndrome symptom recognition and time to ECG acquisition (88).

With respect to ACS symptom recognition, some explanations have oversimplified the inequities female patients experience with inaccurate assertions that women do not present with “typical” signs and symptoms, leaving clinicians and patients themselves to associate “typical” signs as being reserved for males when, in fact, chest pain or discomfort is the most common presentation for female patients with ACS (89, 90). However, female patients with STEMI are more likely than male patients to present with non-chest pain symptoms (such as shoulder pain, throat/neck pain, back pain, and nausea (89); this highlights the need for a more standardized approach to symptom assessment for ACS rather than a narrow focus on chest pain (82, 90). Differences in and biases regarding sex and gender must be explicitly acknowledged to begin the process of eliminating inequities in prehospital evaluation and management of ACS (91). Furthermore, symptom recognition and appropriate self-advocacy for concerning symptoms are important in the trajectory of ACS diagnosis, and a key focus for improvement in achieving sex and gender equity in prehospital ACS care is to increase ACS symptom recognition in female patients (92).

With respect to time to ECG performance, recent research exploring EMS clinician perspectives offers insight into addressing inequities (91). Barriers to ECG acquisition identified by clinicians included themes of safety (respect for patient privacy, sex/gender discordance, liability in exposure/assessment), training and learning (lack of opportunities to perform the skill on female mannequins or patients during training), and professionalism (ability to communicate with the patient regarding the procedure and to self-recognize bias). It is imperative to consider how to provide adequate education and training opportunities to enforce sex and gender equity in care, both in procedural skills (93) and in therapeutic and effective patient communication (Figure 5C).

CONCLUSION

Despite equity being named as a stated aim of health care quality more than 20 years ago (5), care inequities not only persist but efforts at improving quality overall have at times worsened inequities. All segments of the health care system, including EMS, must accept that there is no quality without equity (94). As inequities are driven by system factors, achieving equity will require systemic change. This paper describes an improvement science framework to begin the process of measuring and reducing care inequities in EMS. However, as there are not examples of successful frameworks that improved equity in EMS, the proposed change theories represent untested ideas. Thus, above all else, this paper is a call to action to collectively go forth and test, build knowledge, and relentlessly pursue excellent and equitable outcomes for communities.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: None

DECLARATION OF INTEREST STATEMENT: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Author Contributions Statement: AF, RPC, MT, RT, SO, BB, DIP, MD developed the project idea. AF, RPC, JK, JMG, MT, NL, JU, TP, RT, JK, SO, AH, BB, MD wrote the position statement. AF, RPC, JK, JMG, SA, JCI, NL, TP, RT, JK, APJ, MAC, SO, AH, BB, MD wrote the resource document.

Declarations of interest statement: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Table 1: Definitions of implicit bias, explicit bias and microaggressions

Table 2: Institute for Healthcare Improvement Framework for Achieving Health Equity (6)

Figure 1: The Institute for Healthcare Improvement Model for Improvement; reproduced with permission (4).

Figure 3: An example of a run chart displaying a quality measure (12-lead ECG acquisition for patients with Acute Coronary Syndrome) disaggregated by sex as documented in the ePCR.

REFERENCES:

- Farcas AM, Joiner AP, Rudman JS, Ramesh K, Torres G, Crowe RP, Curtis T, Tripp R, Bowers K, von Isenburg M, et al. Disparities in Emergency Medical Services Care Delivery in the United States: A Scoping Review. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2023;27(8):1058-71.

- Powers RJ, Taigman M. Debating quality assurance vs. quality improvement. Jems. 1992;17(1):65, 7-70.

- Taigman M. Implementing Patient Centered Quality Management. Best Practices in Emergency Services. 2014.

- Langley GL MR, Nolan KM, Nolan TW, Norman CL, Provost LP. The improvement guide: a practical approach to enhancing organizational performance. 2nd ed.: Jossey-Bass; 2009. 490 p.

- Institute of Medicine Committee on Quality of Health Care in A. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US)

- Copyright 2001 by the National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.; 2001.

- Wyatt R LM, Botwinick L, Mate K, Whittington J. Achieving Health Equity: A Guide for Health Care

- Organizations. IHI White Paper. Institute for Healthcare Improvement. 2016.

- Mueller M, Purnell TS, Mensah GA, Cooper LA. Reducing racial and ethnic disparities in hypertension prevention and control: what will it take to translate research into practice and policy? Am J Hypertens. 2015;28(6):699-716.

- Pollack CE, Armstrong K. Accountable care organizations and health care disparities. Jama. 2011;305(16):1706-7.

- Crowe RP, Kennel J, Fernandez AR, Burton BA, Wang HE, Van Vleet L, Bourn SS, Myers B. Racial, Ethnic, and Socioeconomic Disparities in Out-of-Hospital Pain Management for Patients With Long Bone Fractures. Ann Emerg Med. 2023;82(5):535-45.

- Nundy S, Cooper LA, Mate KS. The Quintuple Aim for Health Care Improvement: A New Imperative to Advance Health Equity. Jama. 2022;327(6):521-2.

- Panel EATE. EMS Agenda 2050: A People-Centered Vision for the Future of Emergency Medical Services (Report No. DOT HS 812 664). National Highway Traffic Safety Administration; 2019.

- Goldberg A. It matters how we define health care equity. Commentary, Institute of Medicine, Washington, DC. 2012.

- Braveman P, Gruskin S. Defining equity in health. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003;57(4):254-8.

- Institute of Medicine Committee on U, Eliminating R, Ethnic Disparities in Health C. In: Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, editors. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US)

- Copyright 2002 by the National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.; 2003.

- Budd GM, Mariotti M, Graff D, Falkenstein K. Health care professionals' attitudes about obesity: an integrative review. Appl Nurs Res. 2011;24(3):127-37.

- Phelan SM, Burgess DJ, Yeazel MW, Hellerstedt WL, Griffin JM, van Ryn M. Impact of weight bias and stigma on quality of care and outcomes for patients with obesity. Obes Rev. 2015;16(4):319-26.

- Teachman BA, Brownell KD. Implicit anti-fat bias among health professionals: is anyone immune? Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001;25(10):1525-31.

- Wee CC, Phillips RS, McCarthy EP. BMI and cervical cancer screening among white, African-American, and Hispanic women in the United States. Obes Res. 2005;13(7):1275-80.

- Gandhi TK, Burstin HR, Cook EF, Puopolo AL, Haas JS, Brennan TA, Bates DW. Drug complications in outpatients. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15(3):149-54.

- Marcos LR, Uruyo L, Kesselman M, Alpert M. The language barrier in evaluating Spanish-American patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1973;29(5):655-9.

- DuBard CA, Gizlice Z. Language spoken and differences in health status, access to care, and receipt of preventive services among US Hispanics. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(11):2021-8.

- Berwick DM. Berwick On Patient-Centered Care: Comments And Responses Health Affairs Blog2009 [Available from: https://www.healthaffairs.org/content/forefront/berwick-patient-centered-care-comments-and-responses.

- Weinick RM, Hasnain-Wynia R. Quality improvement efforts under health reform: how to ensure that they help reduce disparities–not increase them. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(10):1837-43.

- Lion KC, Faro EZ, Coker TR. All Quality Improvement Is Health Equity Work: Designing Improvement to Reduce Disparities. Pediatrics. 2022;149(Suppl 3).

- Association AH. Equity of Care: A Toolkit for Eliminating Health Care Disparities. 2015.

- Rykulski NS, Berger DA, Paxton JH, Klausner H, Smith G, Swor RA. The Effect of Missing Data on the Measurement of Cardiac Arrest Outcomes According to Race. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2023;27(8):1054-7.

- Chan PS, Merritt R, Chang A, Girotra S, Kotini-Shah P, Al-Araji R, McNally B. Race and ethnicity data in the cardiac arrest registry to enhance survival: Insights from medicare self-reported data. Resuscitation. 2022;180:64-7.

- Lupton JR, Schmicker RH, Aufderheide TP, Blewer A, Callaway C, Carlson JN, Ricardo Colella M, Hansen M, Herren H, Nichol G, et al. Racial disparities in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest interventions and survival in the Pragmatic Airway Resuscitation Trial. Resuscitation. 2020;155:152-8.

- Weston BW. Blind Spots: Biases in Prehospital Race and Ethnicity Recording. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2023;27(8):1072-5.

- Kennel J, Withers E, Parsons N, Woo H. Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Pain Treatment: Evidence From Oregon Emergency Medical Services Agencies. Med Care. 2019;57(12):924-9.

- Samalik JM, Goldberg CS, Modi ZJ, Fredericks EM, Gadepalli SK, Eder SJ, Adler J. Discrepancies in Race and Ethnicity in the Electronic Health Record Compared to Self-report. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2023;10(6):2670-5.

- Medicine NAo. Perspectives on Health Equity & Social Determinants of Health 2018.

- Hollister BM, Restrepo NA, Farber-Eger E, Crawford DC, Aldrich MC, Non A. DEVELOPMENT AND PERFORMANCE OF TEXT-MINING ALGORITHMS TO EXTRACT SOCIOECONOMIC STATUS FROM DE-IDENTIFIED ELECTRONIC HEALTH RECORDS. Pac Symp Biocomput. 2017;22:230-41.

- Bejan CA, Angiolillo J, Conway D, Nash R, Shirey-Rice JK, Lipworth L, Cronin RM, Pulley J, Kripalani S, Barkin S, et al. Mining 100 million notes to find homelessness and adverse childhood experiences: 2 case studies of rare and severe social determinants of health in electronic health records. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2018;25(1):61-71.

- Medicine S. We Ask Because We Care 2023 [Available from: https://med.stanford.edu/healthequity/WABWC.html?tab=proxy.

- German D, Kodadek L, Shields R, Peterson S, Snyder C, Schneider E, Vail L, Ranjit A, Torain M, Schuur J, et al. Implementing Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Data Collection in Emergency Departments: Patient and Staff Perspectives. LGBT Health. 2016;3(6):416-23.

- Haider AH, Schneider EB, Kodadek LM, Adler RR, Ranjit A, Torain M, Shields RY, Snyder C, Schuur JD, Vail L, et al. Emergency Department Query for Patient-Centered Approaches to Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity: The EQUALITY Study. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(6):819-28.

- Haider A, Adler RR, Schneider E, Uribe Leitz T, Ranjit A, Ta C, Levine A, Harfouch O, Pelaez D, Kodadek L, et al. Assessment of Patient-Centered Approaches to Collect Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Information in the Emergency Department: The EQUALITY Study. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(8):e186506.

- Improvement TIfH. Create the Data Infrastructure to Improve Health Equity 2019 [Available from: https://www.ihi.org/insights/create-data-infrastructure-improve-health-equity.

- Association NFP. Standard for the Organization and Deployment of Fire Suppression, Emergency Medical Administration Operations, and Special Operations to the Public by Career Fire Departments. National Fire Protection Association, Document No. 1710. 2020.

- Myers JB, Slovis CM, Eckstein M, Goodloe JM, Isaacs SM, Loflin JR, Mechem CC, Richmond NJ, Pepe PE. Evidence-based performance measures for emergency medical services systems: a model for expanded EMS benchmarking. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2008;12(2):141-51.

- Alliance NEQ. National EMS Quality Alliance Measure Set 2023 [Available from: https://www.nemsqa.org/nemsqa-measures.

- Association AH. A Framework for Stratifying Race, Ethnicity and Language Data. 2014.

- Wong WF, LaVeist TA, Sharfstein JM. Achieving health equity by design. Jama. 2015;313(14):1417-8.

- Berwick DM. A primer on leading the improvement of systems. Bmj. 1996;312(7031):619-22.

- Soong C, Shojania KG. Education as a low-value improvement intervention: often necessary but rarely sufficient. BMJ Qual Saf. 2020;29(5):353-7.

- Beach MC, Gary TL, Price EG, Robinson K, Gozu A, Palacio A, Smarth C, Jenckes M, Feuerstein C, Bass EB, et al. Improving health care quality for racial/ethnic minorities: a systematic review of the best evidence regarding provider and organization interventions. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:104.

- Maina IW, Belton TD, Ginzberg S, Singh A, Johnson TJ. A decade of studying implicit racial/ethnic bias in healthcare providers using the implicit association test. Soc Sci Med. 2018;199:219-29.

- Hall WJ, Chapman MV, Lee KM, Merino YM, Thomas TW, Payne BK, Eng E, Day SH, Coyne-Beasley T. Implicit Racial/Ethnic Bias Among Health Care Professionals and Its Influence on Health Care Outcomes: A Systematic Review. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(12):e60-76.

- FitzGerald C, Hurst S. Implicit bias in healthcare professionals: a systematic review. BMC Med Ethics. 2017;18(1):19.

- Dehon E, Weiss N, Jones J, Faulconer W, Hinton E, Sterling S. A Systematic Review of the Impact of Physician Implicit Racial Bias on Clinical Decision Making. Acad Emerg Med. 2017;24(8):895-904.

- Sue DW, Capodilupo CM, Torino GC, Bucceri JM, Holder AM, Nadal KL, Esquilin M. Racial microaggressions in everyday life: implications for clinical practice. Am Psychol. 2007;62(4):271-86.

- Morgenstern LB, Smith MA, Lisabeth LD, Risser JM, Uchino K, Garcia N, Longwell PJ, McFarling DA, Akuwumi O, Al-Wabil A, et al. Excess stroke in Mexican Americans compared with non-Hispanic Whites: the Brain Attack Surveillance in Corpus Christi Project. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160(4):376-83.

- Jauch EC, Schwamm LH, Panagos PD, Barbazzeni J, Dickson R, Dunne R, Foley J, Fraser JF, Lassers G, Martin-Gill C, et al. Recommendations for Regional Stroke Destination Plans in Rural, Suburban, and Urban Communities From the Prehospital Stroke System of Care Consensus Conference: A Consensus Statement From the American Academy of Neurology, American Heart Association/American Stroke Association, American Society of Neuroradiology, National Association of EMS Physicians, National Association of State EMS Officials, Society of NeuroInterventional Surgery, and Society of Vascular and Interventional Neurology: Endorsed by the Neurocritical Care Society. Stroke. 2021;52(5):e133-e52.

- Ekundayo OJ, Saver JL, Fonarow GC, Schwamm LH, Xian Y, Zhao X, Hernandez AF, Peterson ED, Cheng EM. Patterns of emergency medical services use and its association with timely stroke treatment: findings from Get With the Guidelines-Stroke. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2013;6(3):262-9.

- Ikeme S, Kottenmeier E, Uzochukwu G, Brinjikji W. Evidence-Based Disparities in Stroke Care Metrics and Outcomes in the United States: A Systematic Review. Stroke. 2022;53(3):670-9.

- Mochari-Greenberger H, Xian Y, Hellkamp AS, Schulte PJ, Bhatt DL, Fonarow GC, Saver JL, Reeves MJ, Schwamm LH, Smith EE. Racial/Ethnic and Sex Differences in Emergency Medical Services Transport Among Hospitalized US Stroke Patients: Analysis of the National Get With The Guidelines-Stroke Registry. J Am Heart Assoc. 2015;4(8):e002099.

- Smith MA, Lisabeth LD, Bonikowski F, Morgenstern LB. The role of ethnicity, sex, and language on delay to hospital arrival for acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2010;41(5):905-9.

- Ellis C, Egede LE. Ethnic disparities in stroke recognition in individuals with prior stroke. Public Health Rep. 2008;123(4):514-22.

- Govindarajan P, Lin L, Landman A, McMullan JT, McNally BF, Crouch AJ, Sasson C. Practice variability among the EMS systems participating in Cardiac Arrest Registry to Enhance Survival (CARES). Resuscitation. 2012;83(1):76-80.

- Banerjee P, Koumans H, Weech MD, Wilson M, Rivera-Morales M, Ganti L. AHORA: a Spanish language tool to identify acute stroke symptoms. Stroke Vasc Neurol. 2022;7(2):176-8.

- Skolarus LE, Sharrief A, Gardener H, Jenkins C, Boden-Albala B. Considerations in Addressing Social Determinants of Health to Reduce Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Stroke Outcomes in the United States. Stroke. 2020;51(11):3433-9.

- Boden-Albala B, Quarles LW. Education strategies for stroke prevention. Stroke. 2013;44(6 Suppl 1):S48-51.

- Hewes HA, Dai M, Mann NC, Baca T, Taillac P. Prehospital Pain Management: Disparity By Age and Race. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2018;22(2):189-97.

- Aceves A, Crowe RP, Zaidi HQ, Gill J, Johnson R, Vithalani V, Fairbrother H, Huebinger R. Disparities in Prehospital Non-Traumatic Pain Management. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2023;27(6):794-9.

- Hoffman KM, Trawalter S, Axt JR, Oliver MN. Racial bias in pain assessment and treatment recommendations, and false beliefs about biological differences between blacks and whites. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(16):4296-301.

- Owusu-Ansah S, Tripp R, S NW, M PM, Whitten-Chung K. Essential Principles to Create an Equitable, Inclusive, and Diverse EMS Workforce and Work Environment: A Position Statement and Resource Document. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2023;27(5):552-6.

- Lindbeck G, Shah MI, Braithwaite S, Powell JR, Panchal AR, Browne LR, Lang ES, Burton B, Coughenor J, Crowe RP, et al. Evidence-Based Guidelines for Prehospital Pain Management: Recommendations. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2023;27(2):144-53.

- Crowe RP, Krebs W, Cash RE, Rivard MK, Lincoln EW, Panchal AR. Females and Minority Racial/Ethnic Groups Remain Underrepresented in Emergency Medical Services: A Ten-Year Assessment, 2008-2017. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2020;24(2):180-7.

- Rudman JS, Farcas A, Salazar GA, Hoff JJ, Crowe RP, Whitten-Chung K, Torres G, Pereira C, Hill E, Jafri S, et al. Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion in the United States Emergency Medical Services Workforce: A Scoping Review. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2023;27(4):385-97.

- Anderson SR, Gianola M, Perry JM, Losin EAR. Clinician-Patient Racial/Ethnic Concordance Influences Racial/Ethnic Minority Pain: Evidence from Simulated Clinical Interactions. Pain Med. 2020;21(11):3109-25.

- Araújo C, Pereira M, Laszczyńska O, Dias P, Azevedo A. Sex-related inequalities in management of patients with acute coronary syndrome-results from the EURHOBOP study. Int J Clin Pract. 2018;72(1).

- Garcia M, Mulvagh SL, Merz CN, Buring JE, Manson JE. Cardiovascular Disease in Women: Clinical Perspectives. Circ Res. 2016;118(8):1273-93.

- Guo Y, Yin F, Fan C, Wang Z. Gender difference in clinical outcomes of the patients with coronary artery disease after percutaneous coronary intervention: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97(30):e11644.

- Udell JA, Fonarow GC, Maddox TM, Cannon CP, Frank Peacock W, Laskey WK, Grau-Sepulveda MV, Smith EE, Hernandez AF, Peterson ED, et al. Sustained sex-based treatment differences in acute coronary syndrome care: Insights from the American Heart Association Get With The Guidelines Coronary Artery Disease Registry. Clin Cardiol. 2018;41(6):758-68.

- Jackson AM, Zhang R, Findlay I, Robertson K, Lindsay M, Morris T, Forbes B, Papworth B, McConnachie A, Mangion K, et al. Healthcare disparities for women hospitalized with myocardial infarction and angina. Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes. 2020;6(2):156-65.

- Cui ER, Fernandez AR, Zegre-Hemsey JK, Grover JM, Honvoh G, Brice JH, Rossi JS, Patel MD. Disparities in Emergency Medical Services Time Intervals for Patients with Suspected Acute Coronary Syndrome: Findings from the North Carolina Prehospital Medical Information System. J Am Heart Assoc. 2021;10(15):e019305.

- Lewis JF, Zeger SL, Li X, Mann NC, Newgard CD, Haynes S, Wood SF, Dai M, Simon AE, McCarthy ML. Gender Differences in the Quality of EMS Care Nationwide for Chest Pain and Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest. Womens Health Issues. 2019;29(2):116-24.

- Meisel ZF, Armstrong K, Mechem CC, Shofer FS, Peacock N, Facenda K, Pollack CV. Influence of sex on the out-of-hospital management of chest pain. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17(1):80-7.

- Dawson LP, Nehme E, Nehme Z, Davis E, Bloom J, Cox S, Nelson AJ, Okyere D, Anderson D, Stephenson M, et al. Sex Differences in Epidemiology, Care, and Outcomes in Patients With Acute Chest Pain. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2023;81(10):933-45.

- Melberg T, Kindervaag B, Rosland J. Gender-specific ambulance priority and delays to primary percutaneous coronary intervention: a consequence of the patients' presentation or the management at the emergency medical communications center? Am Heart J. 2013;166(5):839-45.

- McDonald N, Little N, Grierson R, Weldon E. Sex and Gender Equity in Prehospital Electrocardiogram Acquisition. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2022;37(2):1-7.

- O'Neil A, Scovelle AJ, Milner AJ, Kavanagh A. Gender/Sex as a Social Determinant of Cardiovascular Risk. Circulation. 2018;137(8):854-64.

- Runnels V, Tudiver S, Doull M, Boscoe M. The challenges of including sex/gender analysis in systematic reviews: a qualitative survey. Syst Rev. 2014;3:33.

- Singh H. Editorial: Helping health care organizations to define diagnostic errors as missed opportunities in diagnosis. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2014;40(3):99-101.

- Quinn T, Johnsen S, Gale CP, Snooks H, McLean S, Woollard M, Weston C. Effects of prehospital 12-lead ECG on processes of care and mortality in acute coronary syndrome: a linked cohort study from the Myocardial Ischaemia National Audit Project. Heart. 2014;100(12):944-50.

- Nam J, Caners K, Bowen JM, Welsford M, O'Reilly D. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the benefits of out-of-hospital 12-lead ECG and advance notification in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction patients. Ann Emerg Med. 2014;64(2):176-86, 86.e1-9.

- Zègre-Hemsey J, Sommargren CE, Drew BJ. Initial ECG acquisition within 10 minutes of arrival at the emergency department in persons with chest pain: time and gender differences. J Emerg Nurs. 2011;37(1):109-12.

- Sederholm Lawesson S, Isaksson RM, Thylén I, Ericsson M, Ängerud K, Swahn E. Gender differences in symptom presentation of ST-elevation myocardial infarction - An observational multicenter survey study. Int J Cardiol. 2018;264:7-11.

- DeVon HA, Mirzaei S, Zègre-Hemsey J. Typical and Atypical Symptoms of Acute Coronary Syndrome: Time to Retire the Terms? J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9(7):e015539.

- Hussain A, McDonald N, Little N, Weldon E. Paramedic perspectives on sex and gender equity in prehospital electrocardiogram acquisition. Paramedicine. 2023;20(1):23-34.

- Asghari E, Gholizadeh L, Kazami L, Taban Sadeghi M, Separham A, Khezerloy-Aghdam N. Symptom recognition and treatment-seeking behaviors in women experiencing acute coronary syndrome for the first time: a qualitative study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2022;22(1):508.

- Politis M, El Brown M, Huser CA, Crawford L, Pope L. 'I wouldn't know what to do with the breasts': the impact of patient gender on medical student confidence and comfort in clinical skills. Educ Prim Care. 2022;33(6):316-26.

- Feeley D. There can be no quality without equity. Aust Health Rev. 2020;44(4):503.