Abstract

The management of gastrointestinal (GI) hemorrhage in a prehospital setting presents significant challenges, particularly in arresting the hemorrhage and initiating resuscitation. This case report introduces a novel instance of prehospital whole blood transfusion to an 8-year-old male with severe lower GI hemorrhage, marking a shift in prehospital pediatric care. The patient, with no previous significant medical history, presented with acute rectal bleeding, severe hypotension (systolic/diastolic blood pressure [BP] 50/30 mmHg), and tachycardia (148 bpm). Early intervention by Emergency Medical Services (EMS), including the administration of 500 mL (16 mL/kg) of whole blood, led to marked improvement in vital signs (BP 97/64 mmHg and heart rate 93 bpm), physiology, and physical appearance, underscoring the potential effectiveness of prehospital whole blood transfusion in pediatric GI hemorrhage. Upon hospital admission, a Meckel’s diverticulum was identified as the bleeding source, and it was successfully surgically resected. The patient’s recovery was ultimately favorable, highlighting the importance of rapid, prehospital intervention and the potential role of whole blood transfusion in managing acute pediatric GI hemorrhage. This case supports the notion of advancing EMS protocols to include interventions historically reserved for the hospital setting that may significantly impact patient outcomes from the field.

Introduction

Pediatric gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding leading to hemorrhagic shock is a life-threatening condition that demands immediate medical intervention (Citation1–5). However, in the United States, lower GI bleeding of all severities results in only 0.3% of pediatric emergency department presentations (Citation6). Traditionally, stabilization and resuscitation of such patients has been reserved for in-hospital settings, with prehospital care focusing on maintaining vital functions and transportation to definitive care. Additionally, the advent of blood product transfusion performance by emergency medical services (EMS) clinicians has slowly shifted the paradigm toward initiating hemorrhagic shock resuscitation in the prehospital setting over the past two decades (Citation7–9). This case report describes what the authors believe to be is the first ever instance of managing a pediatric patient with severe gastrointestinal hemorrhage leading to hemorrhagic shock through the administration of whole blood in the prehospital setting.

Case Presentation

An 8-year-old 30.4 kg male with no significant past medical history was found at home by his mother to have collapsed onto the floor, lethargic, and actively bleeding bright-red blood from his rectum. He had been complaining of generally feeling unwell and fatigued for three days, and the morning prior to his collapse, he had been experiencing non-bilious, non-bloody vomiting and diarrhea. Local EMS was called for, and upon arrival, the patient was found to have extreme pallor with weak radial pulses and delayed capillary refill. Vital signs demonstrated the patient to have been hypotensive (BP 50/30 mmHg), tachycardic (148 bpm), with a blood glucose level of 272 mg/dL, oxygen saturation of 97%, and end-tidal CO2 of 25 mmHg.

The patient’s bleeding was so brisk that an on-scene EMS clinician attempted tamponade via direct pressure while an intravenous (IV) catheter was placed, and a consultation to direct medical oversight was made, approving administration of whole blood. Medical oversight recommended giving half of a unit of whole blood to the patient as the whole blood container was non-graduated, and half of the unit equates to roughly 250 mL. After the first half was administered, treating clinicians determined that although the patient demonstrated improvement in vital signs, blood loss continued, and vital signs had yet to normalize. Therefore, the second half of the unit was administered. A total of 500 mL (16 mL/kg) low-titer O+ whole blood was administered enroute, yielding a marked improvement in patient’s lethargy, pallor, BP (97/64 mmHg), heart rate (93 bpm), and end-tidal CO2 (34 mmHg) before care was transferred to the emergency department (ED) team.

Within the ED, the patient was complaining of abdominal pain, and he was in hemorrhagic shock. His blood pressure began to decrease from 107/66 mmHg to 93/50 mmHg, prompting further transfusion; 300 mL (10 mL/kg) packed red blood cells were administered with repeated improvement in vital signs (BP 104/61 mmHg). His initial hemoglobin level was noted to be 10.9 g/dL with a hematocrit of 32%, a base deficit of 6, and his venous pH was 7.27. His platelet count was 206 K/µl, prothrombin time was 17.6 s with an international normalized ratio (INR) of 1.43, and his activated partial thromboplastin time was 33.4 s. Thus, supplemental Vitamin K was administered, and computed tomographic angiogram of the abdomen and pelvis was executed, demonstrating an acute gastrointestinal bleed arising from a Meckel’s diverticulum with active hemorrhage within the right pelvic ileal loop.

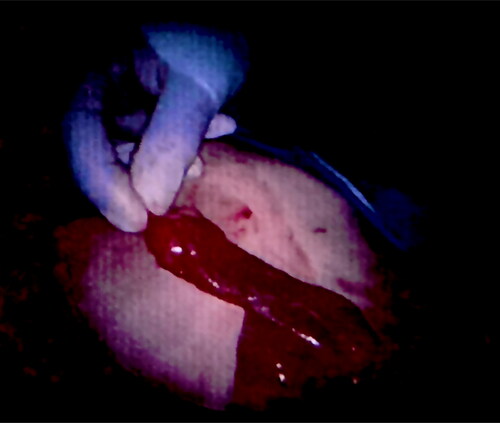

However, while undergoing imaging, patient’s BP decreased from 102/60 mmHg to 97/57 mmHg, prompting transfusion of another 300 mL (10 mL/kg) packed red blood cells over 3 h. During this time, vital signs normalized, no further rectal bleeding was observed, and no more blood products were required. The patient subsequently underwent successful laparoscopic surgery 3.5 h later to resect the diverticulum and the affected adjacent 4 cm segment of the small bowel with admission to the pediatric intensive care unit (). He was discharged to his home on post-operative day four after recovering from his anemia, regaining bowel function, tolerating a regular diet, and having no continued bleeding or uncontrollable pain. He has since remained asymptomatic.

Discussion

The differential diagnosis of acute lower GI bleeding in pediatric patients includes a variety of conditions, the most common of which may be differentiated by their clinical and diagnostic features. Infectious enteritis, such as that caused by Salmonella, Shigella, Campylobacter, or certain Enterococcus species often presents with hematochezia accompanied by abdominal pain and diarrhea (Citation2). Hemolytic uremic syndrome may clinically present similarly to infectious enteritis, but it follows infection with enterohemorrhagic E. coli and is accompanied by acute renal failure, thrombocytopenia, and its sequelae (Citation2). Intussusception is the prolapse of a segment of bowel that invaginates into another, typically at the ileocolic junction, that most commonly manifests in infants and toddlers with intermittent abdominal pain and “currant jelly” stools due to bowel ischemia (Citation6).

Juvenile polyps, benign hamartomatous growths and the most common cause of pediatric painless lower GI bleeding, are typically found in the recto-sigmoid region and are both diagnosed and treated endoscopically (5). Vascular malformations, such as venous malformations, arteriovenous malformations, and hemangiomas, present, are diagnosed, and are treated similarly to hamartomatous polyps but may be found anywhere along the GI tract and rarely occur in children (Citation5). Anorectal fissures, the most common cause of painful pediatric lower GI bleeding, are diagnosed by examination and frequently associated with constipation and blood-streaked, hard stool (Citation5). Ulcerative Colitis, Crohn Disease, and Indeterminant Colitis comprise Inflammatory Bowel Disease, which thus has a variable, chronic presentation but frequently occurs with extraintestinal manifestations, weight loss, and hematochezia (Citation5).

On the other hand, Meckel’s Diverticulum is a congenital anomaly resulting from the persistence of the omphalomesenteric duct, commonly presenting with painless lower GI bleeding due to ulceration of ileal mucosa adjacent to acid-producing ectopic gastric mucosa within the diverticulum, which is most commonly found on the terminal ileum adjacent to the ileocecal valve (Citation10). The occurrence of Meckel’s Diverticulum is uncommon, occurring in 1-2% of the population; its embryology has been previously described (Citation10–14). However, pediatric GI bleeding is also not a common occurrence, especially that which results in hemorrhagic shock as in the case of this patient (Citation1–4,Citation13,Citation15). The use of whole blood transfusions in the prehospital setting is not widely reported in pediatric emergencies, making this case a significant contribution to the body of literature on pediatric emergency medical care (Citation9,Citation16). Thus, the authors believe that this case describes the first ever documented instance in which whole blood has been administered for a pediatric patient experiencing GI hemorrhage in a prehospital setting. Packed red blood cell transfusion has been used in the prehospital environment for a pediatric patient with gastrointestinal hemorrhage in the past but very rarely (Citation1).

As described, the rapid administration of whole blood in this case appears to have effectively initiated the patient’s resuscitation as evidenced by his clinical findings and vital sign improvements. Without such action, there is a greater probability that the patient would have expired before arriving at the hospital due to the briskness of his hemorrhage yielding evidenced hypovolemia and acidosis. Whole blood offers several advantages over component therapy (e.g., packed red blood cells, platelets, plasma, or cryoprecipitate) administration for hemorrhagic shock, including the presence of clotting factors, platelets, and plasma proteins, which are crucial for maintaining hemostasis and ensuring effective volume replacement but cannot collectively be found within each blood component (Citation1,Citation7–9,Citation15–23). Likewise, logistically, whole blood is easier to carry, store, and administer as it is maintained in a single bag, requires no time for thawing, guarantees a balanced resuscitation, and it is associated with a lower transfusion volume required when compared to component therapy (Citation8).

Although EMS clinicians began prehospital blood product administration for hemorrhagic shock patients over the last two decades, this has only been possible when in tandem with supportive patient treatment protocols such as those that allowed this patient to receive whole blood in the field (Citation7–9). Within the large urban EMS system that treated the patient, EMS clinicians credentialed at the paramedic level who have received specific training in the maintenance, storage, transportation, and administration of whole blood may administer whole blood to pediatric medical and trauma patients in hemorrhagic shock as indicated by a systolic BP below 70 mmHg, a systolic BP below 90 mmHg accompanied by a heart rate of at least 110 bpm, an end-tidal CO2 level below 25 mmHg, or a witnessed cardiac arrest due to hemorrhagic shock occurring within five minutes prior to EMS arrival with continuous cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) performed throughout. Patients aged 5-10 years may receive 1 unit, those aged 11-13 years may receive 2 units, and patients older than 13 years may receive more than 2 units. Calls to medical oversight must be made for hemorrhagic shock patients younger than 6 years old or whenever treating clinicians feel it is necessary or need assistance.

Conclusion

This case report demonstrates successful management of severe pediatric GI hemorrhage in the prehospital setting through transfusion of whole blood; as such, it represents a significant shift in prehospital emergency medical care. Thus, such a case supports the growing potential for EMS protocols to evolve beyond traditional boundaries, incorporating advanced interventions that can significantly impact patient outcomes from the prehospital arena.

Declaration of Generative AI in Scientific Writing

The authors did not use a generative artificial intelligence (AI) tool or service to assist with preparation or editing of this work. The author(s) take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank The San Antonio Fire Department for its commitment to excellent prehospital care and for its commitment to advancing EMS protocols.

Disclosure Statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare. The views expressed in this manuscript reflect the results of research conducted by the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Defense Health Agency, Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Fahy AS, Thiels CA, Polites SF, Parker M, Ishitani MB, Moir CR, Berns K, Stubbs JR, Jenkins DH, Zietlow SP, et al. Prehospital blood transfusions in pediatric trauma and nontrauma patients: a single-center review of safety and outcomes. Pediatr Surg Int. 2017;33(7):787–92. doi:10.1007/s00383-017-4092-5.

- Padilla BE, Moses W. Lower gastrointestinal bleeding & intussusception. Surg Clin North Am. 2017;97(1):173–88. doi:10.1016/j.suc.2016.08.015.

- Novak I, Bass LM. Gastrointestinal bleeding in children: current management, controversies, and advances. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2023;33(2):401–21. doi:10.1016/j.giec.2022.11.003.

- Romano C, Oliva S, Martellossi S, Miele E, Arrigo S, Graziani MG, Cardile S, Gaiani F, de’Angelis GL, Torroni F, et al. Pediatric gastrointestinal bleeding: perspectives from the Italian society of pediatric gastroenterology. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23(8):1328–37. doi:10.3748/wjg.v23.i8.1328.

- Baker RD, Baker SS. Gastrointestinal bleeds. Pediatr Rev. 2021;42(10):546–57. doi:10.1542/pir.2020-000554.

- Saliakellis E, Borrelli O, Thapar N. Paediatric GI emergencies. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2013;27(5):799–817. doi:10.1016/j.bpg.2013.08.013.

- Ciaraglia A, Brigmon E, Braverman M, Kidd E, Winckler CJ, Epley E, Flores J, Barry J, DeLeon D, Waltman E, et al. Use of whole blood deployment programs for mass casualty incidents: south Texas experience in regional response and preparedness. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2022;93(6):E182–E184. doi:10.1097/TA.0000000000003762.

- Braverman MA, Smith AA, Ciaraglia AV, Radowsky JS, Schauer SG, Sams VG, Greebon LJ, Shiels MD, Jonas RB, Ngamsuntikul S, et al. The regional whole blood program in San Antonio, TX: a 3-year update on prehospital and in-hospital transfusion practices for traumatic and non-traumatic hemorrhage. Transfusion (Paris). 2022;62(S1):S80–S89. doi:10.1111/trf.16964.

- Spinella PC, Gurney J, Yazer MH. Low titer group O whole blood for prehospital hemorrhagic shock: it is an offer we cannot refuse. Transfusion (Paris). 2019;59(7):2177–9. doi:10.1111/trf.15408.

- Brown CK, Olshaker JS. Meckel’s diverticulum. 1987.

- Kuru S, Kismet K. Meckel’s diverticulum: clinical features, diagnosis and management. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2018;110(11):726–32. doi:10.17235/reed.2018.5628/2018.

- Choi SY, Hong SS, Park HJ, Lee HK, Shin HC, Choi GC. The many faces of Meckel’s diverticulum and its complications. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2017;61(2):225–31. doi:10.1111/1754-9485.12505.

- Lindeman RJ, Søreide K. The many faces of Meckel’s diverticulum: update on management in incidental and symptomatic patients. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2020;22(1):3. doi:10.1007/s11894-019-0742-1.

- Hansen CC, Søreide K. Systematic review of epidemiology, presentation, and management of Meckel’s diverticulum in the 21st century. Medicine. 2018;97(35):e12154. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000012154.

- McQuilten ZK, Crighton G, Brunskill S, Morison JK, Richter TH, Waters N, Murphy MF, Wood EM. Optimal dose, timing and ratio of blood products in massive transfusion: results from a systematic review. Transfus Med Rev. 2018;32(1):6–15. doi:10.1016/j.tmrv.2017.06.003.

- Neff LP, Beckwith MA, Russell RT, Cannon JW, Spinella PC. Massive transfusion in pediatric patients. Clin Lab Med. 2021;41(1):35–49. doi:10.1016/j.cll.2020.10.003.

- Spinella PC, Cap AP. Whole blood: back to the future. Curr Opin Hematol. 2016;23(6):536–42. doi:10.1097/MOH.0000000000000284.

- Brill JB, Mueck KM, Tang B, Sandoval M, Cotton ME, Cameron McCoy C, Cotton BA. Is low-titer group O whole blood truly a universal blood product? J Am Coll Surg. 2023;236(3):506–13. doi:10.1097/XCS.0000000000000489.

- Anand T, Obaid O, Nelson A, Chehab M, Ditillo M, Hammad A, Douglas M, Bible L, Joseph B. Whole blood hemostatic resuscitation in pediatric trauma: a nationwide propensity-matched analysis. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2021;91(4):573–8. doi:10.1097/TA.0000000000003306.

- Brill JB, Tang B, Hatton G, Mueck KM, McCoy CC, Kao LS, Cotton BA. Impact of incorporating whole blood into hemorrhagic shock resuscitation: analysis of 1,377 consecutive trauma patients receiving emergency-release uncrossmatched blood products. J Am Coll Surg. 2022;234(4):408–18. doi:10.1097/XCS.0000000000000086.

- Hatton GE, Brill JB, Tang B, Mueck KM, McCoy CC, Kao LS, Cotton BA. Patients with both traumatic brain injury and hemorrhagic shock benefit from resuscitation with whole blood. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2023;95(6):918–24. doi:10.1097/TA.0000000000004110.

- Morgan KM, Leeper CM, Yazer MH, Spinella PC, Gaines BA. Resuscitative practices and the use of low-titer group O whole blood in pediatric trauma. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2023;94(1S Suppl 1):S29–S35. doi:10.1097/TA.0000000000003801.

- Lauby RS, Cuenca CM, Borgman MA, Fisher AD, Bebarta VS, Moore EE, Spinella PC, Bynum J, Schauer SG. An analysis of outcomes for pediatric trauma warm fresh whole blood recipients in Iraq and Afghanistan. Transfusion. 2021;61(S1):S2–S7. doi:10.1111/trf.16504.