ABSTRACT

Violence metaphors for cancer can have undesirable implications. The metaphorical expression “She lost her battle with cancer,” for instance, is deemed inappropriate by some because of the implicit suggestions it would carry about patients’ responsibility to recover from the disease – if someone “lost” it is inferred they could also have “won” if only they had “fought harder.” The current study explores how language users may use a metaphor extension approach to argue against metaphorical implications they feel are harmful, offensive or otherwise inappropriate. More specifically, this paper will combine recent findings in metaphor research on metaphor extension with two case studies on argumentative resistance to violence metaphors for cancer to illustrate two ways in which these metaphors can be (re)interpreted in such a way that they are in line with language users’ (desired) perspective on the disease. Using analytical tools from Pragma-dialectics, the case studies will demonstrate how a close analysis of expressions of resistance to violence metaphors for cancer that extend these metaphors can 1) help pinpoint the precise metaphorical implications that are being contested in a given case of resistance, and 2) provide an insight into which alternative interpretations are deemed acceptable by the protagonists of resistance.

Introduction

The language of cancer is the language of war. But for everyone who won their battle, someone lost. For every survivor, there’s someone who didn’t make it. The implication being the ones who didn’t win their battle didn’t fight hard enough. They didn’t want it badly enough. They weren’t brave enough to go the extra mile to be the victor. And I call bullshit on that. Cancer is an unfair fight (Gortan, Citation2016).

Violence metaphors for cancer can have undesirable implications. The above excerpt, written by a cancer patient, illustrates how the metaphor of cancer as “battle” is understood to suggest that cancer can be overcome by those who “fight hard enough,” which in turn is taken to imply that patients who die from the disease did not manage to do so.Footnote1 The author of the excerpt explicitly resists this implication and argues instead that having cancer is in fact “an unfair fight.”

In the large body of studies on metaphors for cancer various shortcomings have been reported that can be related to the implications these metaphors may have for people who are affected by cancer (e.g., Byrne, Ellershaw, Holcombe, & Salmon, Citation2002; Demmen et al., Citation2015; Hendricks et al., Citation2018; Macmillan Cancer Support, Citation2018; Semino et al., Citation2015).Footnote2 Hendricks and colleagues (2018), for instance, found that when a cancer patient’s illness experience is described as a “battle” this can make people believe that the patient is more likely to feel guilty if they do not recover compared to when their situation would be described as a “journey.” The study’s findings were in line with the researchers’ predictions that the metaphor of “battle” suggests that the patient is responsible for the outcome of the disease.

Another example is a study by Byrne et al. (Citation2002), who analyzed the role language of effort and fighting in clinical communication with cancer patients in relation to patients’ experience of their disease. The study found that if patients perceive their clinicians as promoting “fighting” and keeping a positive attitude, patients can feel the need to conceal their own distress and suffering in order to avoid upsetting others. This emotional suppression adds to the physical and psychological burden patients are faced with already and might hinder their progress toward coping with the experience of cancer (p. 21).

For the purpose of circumventing any negative effects violence metaphors for cancer can have it is sometimes argued that these metaphors should be avoided altogether (e.g., Haines, Citation2014; Sontag, Citation2014; also see Wackers et al., 2021, on (prescriptive) resistance standpoints). But violence metaphors for cancer are highly conventionalized in discourse about cancer and will continue to be used in many communicative settings, including settings that cannot be controlled for. That is to say, particular stakeholder groups such as health practitioners can be made aware of the potentially harmful effects of violence metaphors for cancer so they can act on this in communication with (individual) cancer patients. For communication that is not one-to-one, however, recipients’ situation or emotions will not – cannot – always be accounted for in such a way. Violence metaphors in public discourse about cancer will inevitably confront some with, to them, undesirable implications about the metaphors’ target domain.

If we take a detailed look at public discussions on violence metaphors for cancer it can be seen that ordinary language users also explicitly criticize these metaphors – without rejecting the use of the metaphors altogether. Moreover, they sometimes offer alternative interpretations of these metaphors to replace more conventional and allegedly inappropriate ones. In this paper we will analyze two opinion articles in which arguments are advanced against particular implications of violence metaphors for cancer and for specific reinterpretations of said metaphors.

Put in different terms, our research focuses on two phenomena that can be observed in argumentative discussions on violence metaphors for cancer in public discourse, i.e., what we call “expressions of resistance” to these metaphors and the use of “metaphor extension” to counter certain metaphorical implications. By “resistance” we specifically mean argumentative resistance or resistance that is supported by argumentsFootnote3; following Landau, Keefer, and Swanson (Citation2017), the paper defines “metaphor extension” as a manner of endorsing a given metaphor in broad outlines while arguing that it has been applied incorrectly, thereby drawing attention “to other familiar features of the metaphor’s concrete concept, [encouraging observers] to apply that knowledge to interpret the target issue” (Landau, Keefer and Swanson, Citation2017, p. 64). Illustrative examples of both phenomena will be given further on in this paper.

The paper principally aims to demonstrate the added value of closely analyzing expressions of resistance to metaphor to identify the precise metaphorical implications that are being contested in a given case of resistance as well as the alternative interpretations that proposed by the protagonists of the resistance. The paper will make use of pragma-dialectical instruments for argumentation analysis (Van Eemeren, Citation2015; Van Eemeren & Grootendorst, Citation1992) to bring current and novel insights about metaphor extension and resistance to violence metaphors for cancer together. More specifically, two case studies will be conducted in which pragma-dialectical tools for argument reconstruction are used to analyze expressions of resistance to violence metaphors for cancer that are (partially) based on a form of metaphor extension. The case studies will provide valuable input in two important ways: Firstly, a detailed argumentative analysis of such expressions of resistance will help us pinpoint which metaphorical implications are contested in each given case, and why. Secondly, closely examining the different elements of resistance argumentation in which the contested metaphor is extended will help define which alternative interpretationsFootnote4 are deemed (more) acceptable instead.

The results of our argumentative analyses will add to existing knowledge about resistance to metaphor, which has received increased attention over the last couple of years (Finsen, Steen, and Wagemans Citation2021; Renardel de Lavalette, Andone, and Steen Citation2019; Wackers, Plug, and Steen Citation2020, Citation2021). Furthermore, the paper adds new insights to the literature on metaphors of violence and their potential (dis)advantages for conceptualizing the target domain of cancer in particular. In the next section of this paper we will discuss previous studies on the diverging functions of violence metaphors for cancer. The sections thereafter will discuss the concepts of metaphor extension and resistance to metaphor in more detail. The final sections present the paper’s case studies and a discussion of the studies’ main findings.

Violence metaphors for cancer

The use of violence metaphors for cancer has received academic interest in a wide range of disciplines, from the fields of linguistics and communication studies to medicine and psychology (Fleischman, Citation2001).Footnote5 A number of studies have demonstrated that violence metaphors for cancer can have undesirable effects, some examples of which have been mentioned in the introduction of this paper (e.g., Byrne et al., Citation2002; Hendricks et al., Citation2018; Macmillan Cancer Support, Citation2018). But there are also positive functions that can be ascribed to these metaphors dependent on the ways in and purposes for which they are used.

Semino, Demmen, and Demjén (Citation2016), who conducted a corpus-based study of contributions to an online forum for people with cancer, found that a patient’s relationship with the disease can have an influence on the functions violence metaphors may have for them. Semino and colleagues also observed a connection between the diverging functions of violence metaphors for cancer and the different metaphor scenariosFootnote6 they were used for. In their data, for instance, the metaphor of “battle” was used for describing three main types of violent scenarios, i.e.: “preparing for battle,” “engaging in battle,” and “outcome of battle”; cancer patients who were going through potentially curative treatment used violence metaphors in empowering ways such as to express pride or determination to “fight” their cancer, while terminal patients for whom the outcome of the metaphorical battle had already been decided in favor of the disease used violence metaphors to express feelings of disempowerment or a negative sense of self.

Gustafsson, Hommerberg, and Sandgren (Citation2019) also conducted a corpus-based study on metaphor use by cancer patients. More specifically, they studied how patients with advanced cancer make use of metaphors in online blogs to make sense of and cope with the difficult aspects of living with their life-limiting disease. Gustafsson, Hommerberg and Sandgren’s research findings demonstrated that the use of metaphor can both articulate and function as part of a patient’s coping process and that the source domains of the different metaphors they examined offered “different flexibility and usefulness for the bloggers in relation to coping” (p. 8). Moreover, the researchers’ analysis of “battle metaphors”Footnote7 showed that patients did not only use these metaphors for describing their “battle” against the disease, but also for their figurative battle with their thoughts and emotions.Footnote8 Gustafsson and colleagues note how this particular use of metaphor enables patients to keep their fighting spirit intact and the perspective of “winning” still possible, independent of the question whether they can (physically) recover from cancer – i.e., “to change the object for the battle makes it possible to win” (p. 4). The researchers relate this particular use of metaphor to coping strategies of “Acceptance” and “Positive reinterpretation and growth.”

The research outcomes by Semino et al. (Citation2016) and Gustafsson et al. (Citation2019) form important starting points for the current study on resistance to violence metaphors for cancer, namely: 1) violence metaphors for cancer can reflect different (positive and negative) ways of understanding or evaluating a particular target domain situation; and 2) (even) if a target domain situation can be considered to concern a negative situation, e.g., if someone is faced with a terminal diagnosis and is no longer able to “defeat” their disease, violence metaphors for cancer can still be used in a positive, empowering way. The latter, involving the application of reinterpretation of a metaphor in a way so to make this metaphor fit with one’s (desired) perspective on a target domain situation, can be linked to the phenomenon of metaphor extension.

Countering implications of metaphor through metaphor extension

The notion of “metaphor extension” is used differently in the literature. Barnden (Citation2015) discusses the ambiguity of the notion and mentions two phenomena it is used to describe. One concerns a metaphorical view being used at more than one occasion throughout a stretch of discourse “rather than just locally within a short sentence” (Citation2015, p. 18).Footnote9 This particular form of metaphor extension will be left out of consideration here. The second type of metaphor extension Barnden describes concerns a form of conceptual extension, “exploiting some unusual aspect of the source subject matter of some familiar metaphorical view – unusual in the sense that that aspect is not normally exploited in uses of the view.” The latter corresponds with the phenomenon that is central to our study; moreover, in our study we are particularly interested in its occurrence in argumentation against (a) metaphor(s). Before we will go into the specifics of our argumentative analysis of metaphor extension in expressions of resistance to violence metaphors for cancer, we will discuss a recent study that has been conducted on the use of metaphor extension in argumentative discourse, done by Landau et al. (Citation2017).Footnote10

Starting from the premise that a metaphor can systematically influence people’s attitudes toward its target domain, Landau et al. (Citation2017) raised the “practically important but understudied” (p. 63) question of how a metaphor’s influence can be effectively undone once it has entered discourse. Their study focused on testing the effectiveness of metaphor extension as part of a rebuttal strategy. In this particular rebuttal strategy a metaphor is endorsed in broad outlines but is argued to have been applied incorrectly. We will briefly describe (part of) Landau and colleagues’ case study on the conventional household metaphor that compares the United States federal budget to a typical household budget in order to illustrate in more detail how metaphor extension can function as part of a rebuttal message.

In one of the studies’ experiments, Landau et al. (Citation2017) asked research participants to read an article in which the household metaphor was used to argue in favor of cutting funding for federal programs. The article argued, for instance, that “[families] often have to make sacrifices and cut spending to keep a budget and live within their means. When they cannot pay for things they want, like a new bike or a family vacation, they just have to wait or make sacrifices to get by. […] If a family doesn’t have the money to pay for stuff, it cuts back on its spending. Likewise, the government cannot afford all the federal programs we have, and so it should cut spending.” (Landau et al., Citation2017, p. 79).

After having read this article, half of the participants were asked to read a rebuttal of the article arguing in favor of spending cuts that contained direct arguments against spending cuts and ignored the household metaphor, while the other half of the participants read a rebuttal that extended the household metaphor. In this latter rebuttal the household metaphor was used to highlight features of the source domain that legitimized spending. Instead of focusing on the strategy that is based living within one’s means, the rebuttal pointed out that families also frequently (and justifiably) take on large debts. The rebuttal argued, for instance that “[families] make long-term investments all the time, and for good reasons: taking out big loans can help kids go to college, provide a family with a new car, […] Loans like these are investments that are costly at first, but they pay off in the long run. In fact, they are necessary for families to succeed. The government should take the same approach to spending that successful families do […]” (Landau et al., Citation2017, p. 81).Footnote11

In the experiment described above, participants who read the extension rebuttal of the article arguing in favor of spending cuts were encouraged to view the target issue in another way without giving up the metaphor’s source domain.Footnote12 Inspired by this mechanism, in this paper we examine how language users (in actual practice) may use a form of metaphor extension in order to argue against undesirable implications of metaphors without rejecting the metaphors’ source. Here the extension is principally aimed at refuting what a particular metaphor is taken to mean or imply – i.e., instead of a claim or standpoint in which a given metaphor is used – and an alternative meaning is proposed. To our knowledge, no study to date has examined this specific use of metaphor extension yet. The current paper moreover provides a novel angle on metaphor extension by carrying out a systematic (pragma-dialectical) analysis of the arguments that are advanced to motivate the extension in a given case of resistance. In the next section we will demonstrate how an analysis according to the pragma-dialectical approach gives a clear overview of the precise metaphorical implications that are being contested in each given case of resistance as well as the alternative interpretations that are proposed by the protagonists of the resistance.

An argumentative analysis of resistance to violence metaphors for cancer

The argumentation that is advanced in expressions of resistance to violence metaphors for cancer can be analyzed through a close analysis of the different argumentative elements the resistance consists of and what the relations between these different elements are. Pragma-dialectics, founded by van Eemeren and Grootendorst (Van Eemeren, Citation2015; Van Eemeren & Grootendorst, Citation1992), offers a set of analytical tools to map the structure argumentation is made up of. These are based on cues in the verbal presentation of a proposition that indicate which role(s) this proposition plays in the argumentation as a whole.

An example of an argumentation structure that consists of different forms of argumentation is shown in below:

Figure 1. Example of an argumentation structure containing multiple, subordinative and coordinative argumentation.

The structure of this made-up example can be read as follows: According to the pragma-dialectical notation system, a standpoint is indicated by a number followed by a full stop, such as 1.; if there are multiple standpoints at issue, the next standpoint receives the number “2.,” et cetera. The first argument that is provided in support of a standpoint is mentioned directly under the standpoint and repeats the number of the standpoint followed by the number “1”: “1.1”. Arguments that are provided in support of arguments form a chain of subordinately compound argumentation and are numbered according to the same principle (“1.1.1”; “1.1.1.1”; et cetera). Additional indices “a,” “b” (et cetera) are added if the arguments form coordinatively compound argumentation, which is the case if they can only provide sufficient support for the standpoint when taken together. Lastly, argumentation that is called “multiple” consists of alternative defenses of a proposition that are unrelated; arguments that make up multiple argumentation each receive a different number at the same level (e.g., “1.2”, “1.3”, et cetera.).

Pragma-dialectics uses insights from linguistic pragmatics to decide which utterances can be reconstructed as (which type of) standpoints or arguments and which commitments arguers may be held accountable for on the basis of what they have said;Footnote13in our case studies below, we will point out some examples of how contextual and other pragmatic factors are taken into account in a pragma-dialectical reconstruction. Most importantly, however, the case studies in the next two subsections will illustrate how a reconstruction of argumentation that is provided in support of resistance to violence metaphors for cancer enables us to gain a more detailed insight into actual language users’ reasons for resisting particular implications of violence metaphors for cancer as well as their grounds for considering alternative interpretations of these metaphors more appropriate. I.e., in contrast to the example in , the examples in the case studies do not reject the use of violence metaphors for cancer entirely but offer a more nuanced view on these metaphors by assigning novel interpretations to particular mappings that elicit resistance.

Data selection and analysis

The instances of resistance that are the focus of the case studies are from two opinion articles. The articles have been selected from a larger corpus of texts featuring instances of resistance to violence metaphors for cancer. This corpus was manually compiled by one of the authors and has been stored in the UvA/HvA figshare database at The University of Amsterdam. The analysis of the data proceeded as follows: The authors first analyzed the instances of resistance individually according to the pragma-dialectical method for argument analysis. Then, different reconstructions of the same data were discussed and a joint decision was made about which reconstruction could be considered the most beneficial to the author of the text.Footnote14

The selected articles were considered to be illustrative examples of how metaphor extension can occur in resistance to violence metaphors for cancer. In the next sections it will be shown how each of the articles discusses arguments against particular violence metaphors for cancer without claiming that these metaphors should be abandoned altogether; instead, attention is drawn to aspects of the source domain that are less commonly considered in the context of cancer.

Case study 1

Our first case study concerns an opinion article in which a cancer research expresses resistance to the metaphor that people who die from cancer have “lost their battle against cancer” (Wosnick, Citation2013).Footnote15Footnote16Footnote17 demonstrates a reconstruction of the resistance standpoint and supporting arguments:

The structure shows the different lines of argumentation put forward by the author of the article. Argument1.1 concerns the assertion that “[cancer] is not a game of winners and losers”. The next two sentences in the structure illustrate that not all arguments take the shape of explicit statements: Asking “If you live you “win” and if you die you “lose”? How inappropriate is that?” the author further motivates his criticism of the metaphorical analogy between cancer and “a game of winners and losers” by pointing the readers’ attention to the fact that this comparison can be considered inappropriate. That is to say, in the context of the author’s further remarks about the mapping between cancer and a game that can be won or lost, this question can be considered redundant if taken literally.Footnote18 Instead, it can be interpreted as a rhetorical question functioning as an argument.

In 1.2a-1.2b the author narrows down his resistance to one metaphorical mapping in particular: the mapping between dying from cancer and “losing (the battle)” against the disease. The arguments the author provides in support of this standpoint can be grouped into three main lines of coordinative argumentation.

In the first line of argumentation (1.2b.1(n)) it is specified why the author deems the metaphorical comparison between dying from cancer and “losing (the battle)” against the disease problematic – it is the implication that a cancer patient might have “won” if they had done something else differently (1.2b.1) the author disagrees with. The coordinative arguments 1.2b.1.1a and 1.2b.1.1b clarify where the author thinks these implications stem from: according to him, if someone loses this automatically means someone (something) else wins; for the metaphor that compares having cancer to a “battle,” this would mean that if a patient “loses,” cancer is the figurative winner. Such “power” is never “ceded” to other diseases (1.2b.1 c.1b.1; 1.2b.1 c.1b.1.1; 1.2b.1 c.1b.1.2). Furthermore, the undesirable consequence of this metaphorical mapping would be its underlying suggestion that the “ultimate responsibility” for dying from cancer lies with the cancer patient him- or herself (1.2b.1 c.1b.2).

In the second main line of argumentation (1.2b.2(n)) the author puts forward an argument that may at first glance seem a counterargument to his own case. He mentions that many people may “disagree totally with [him] and feel that the battle analogy empowers them somehow” (1.1b.2a). However, while the author thinks there is a problematic aspect to comparing cancer to a “battle,” he does not argue that this comparison is entirely problematic or should be gotten rid of completely (also see 1.2a). He specifically resists the notion that people who die from cancer have “lost the battle.” In other words, even though there may be many people who find the battle analogy empowering and thus see positive aspects to using this analogy, the author’s resistance does not contradict or reject this.Footnote19 Nevertheless, the author ends the paragraph in which this line of argumentation is put forward with the conclusion that no one should be “blamed” if they do not recover from their disease (1.1b.2b). This is in line with his previous arguments that cancer patients cannot and should not be held responsible for the outcome of the metaphorical battle against cancer should they ultimately die from the disease (also see 1.2b.1 and 1.2b.1 c.1b.2 in particular).

In the third and last main line of argumentation (1.2b.3(n)) the then recent death of American film critic Roger Ebert functions as argumentation by example. The author’s observation that many of the obituaries and tributes on Roger Ebert mentioned how Ebert “lost his battle with cancer” is what prompted the author to write this piece about “lost battle language.” In these last arguments the author argues why Ebert did not “lose” his battle with cancer but can be said to have “won” instead even though he died from the disease (1.1b.3). In other words, the author mentions a number of arguments why “winning the battle against cancer” can also be understood to mean something else than surviving (or not succumbing to) the disease (1.2b.3.1). For Roger Ebert specifically it was living “graciously and courageously with [cancer] until the very end [of his life]” (1.2b.3.1.1) and being “a wonderful role model right to the end” (1.2b.3.1.2).

In sum, the author of example 1 argues that dying from cancer should not be equated with “losing the battle.” One important reason is that this metaphor seems to place the responsibility for living or dying in the hands of the patient. Furthermore, while some patients may feel the metaphor is empowering and helps them through this difficult process that can indeed be called a “battle,” the author still holds that saying they “have lost their battle” after they have deceased is inappropriate. Another important reason for the author to resist the “lost battle metaphor” lies in his view that cancer can be overcome – or “won from” – in different ways.

In this last line of argumentation metaphor extension takes place. The author retains the battle metaphor as well as the metaphor of “winning” this figurative fight, but he gives a novel interpretation to these metaphors relative to their (allegedly) more conventional meanings. The story of Roger Ebert functions as an argument by example: even though Ebert died, he can be said to have defeated cancer in another way, namely by, among other things, having “lived graciously and courageously with [cancer] until the very end [of his life]” (1.2b.3.1.1). In other words, the metaphor of “winning the fight against cancer” is given a novel meaning by applying it to another target domain situation (e.g., “living graciously and courageously with cancer until the very end”); as a result, interpretations of what this means in the context of the target domain of cancer, change.

The argumentation structure helps to gain detailed insight into the author’s resistance standpoint and the arguments that are provided in support of it, as well as the application of a metaphor extension approach in one of the lines of argumentation to counter an undesirable implication of the contested metaphor. More specifically, the different main lines and subordinate levels of argumentation lay bare a) the author’s arguments for resisting a particular metaphorical mapping (1.2a – 1.2b.1 c.1b.2); b) his arguments for retaining other mappings (1.2a and 1.2a.1; 1.2b.2a-b); and c) his “solution” to counter the implications of the contested mapping by extending it (1.2b.3– 1.2b.3.1.2).

Case study 2

The example of our next case study concerns an opinion article by a writer who has been diagnosed with cancer (Gortan, Citation2016).Footnote20 The structure of the standpoint and arguments against violence metaphors for cancer is shown in .Footnote21

As the structure shows, the article states that we need to change the language that we use to talk about cancer (1.). This standpoint is supported by two main lines of argumentation, 1.1(n) and 1.2(n). In the former the author expresses her disapproval of “the language of war” that is so commonly used in relation to cancer, arguing that the implications that underlie this language use are nonsensical (“bullshit”). In 1.2(n)Footnote22 it is argued that people need to stop using the word “brave” and “the euphemistic journey [metaphor]” that abound in conversations about cancer (1.2(n)).Footnote23 We will first go into the arguments that are provided in support of 1.1.

Propositions 1.1– 1.1.1.1.1.1.1 discuss the metaphor that compares having cancer to a battle. According to the author, this particular metaphor implies that “the ones who didn’t win their battle didn’t fight hard enough,” which she judges to be untrue. The chain of subordinate arguments 1.1.1 through 1.1.1.1.1.1.1 demonstrate exactly why she disagrees with this implication. Essentially, the author argues that having cancer is an “unfair fight” (1.1.1). She compares the metaphorical fight against cancer to the biblical story of David against Goliath, the story that describes the archetypal fight between two seemingly unequal opponents. The author contends that “fighting” cancer is not analogous to the biblical underdog story as “[it] is so much more than [that]” (1.1.1.1): against cancer, we are “flying blind” (1.1.1.1.1) – patients can try and “fight” their disease with the help of modern medicine, doctors, and drugs (1.1.1.1.1.1), but there is no definitive cure that can “guarantee a win” (1.1.1.1.1.1.1). Faced with a physically stronger opponent, David relied on other means to achieve his victory on the giant. Cancer patients, on the contrary, are not able to outwit or trick cancer into defeat. Unlike David they have no control over their recovery – modern medicine, doctors and drugs “up [their] chances yes, but won’t deliver a definitive cure” (1.1.1.1.1.1.1).

The arguments that are provided in support of 1.2 concern a more personal account of the author on why she also specifically resists the word “brave” and the “euphemistic journey [metaphor]” that are commonly used in discourse about cancer. The first line of supporting arguments for 1.2 form a coordinative argumentation of which (1.2.1.)1a – (1.2.1.)1a.1 make up the first part and (1.2.1).1b – (1.2.1).1b.1 the second part. The implicit argument (1.2.1) and arguments (1.2.1.)1a – (1.2.1.)1a.1 discuss the author’s chances that her cancer will return in relation to her efforts to prevent that from happening: Even though she has done everything that lies within her power to reduce the chance of relapse ((1.2.1.)1a.1), there is still more than a ten percent chance the cancer may recur within ten years ((1.2.1.)1a). In (1.2.1).1b the author adds that she does not feel “brave” even though many people call her that; the reason why she does not feel braver than anyone else is because she considers what she is doing is “just [what she needs] to do to ensure [she lives] a long healthy life” ((1.2.1).1b.1).

Propositions 1.2.2(n) and 1.2.3 provide further arguments why we should lose the word “brave” in conversations about cancer. In 1.2.2(n) it is stated that a consequence of using this word is that it can make patients feel guilty for feeling fear, feelings they are bound to experience because having cancer “instils fear, terror and the desire to run far, far away, stick your head in the sand and pretend nothing is wrong so you won’t have to face it.” Lastly, the author feels the word “brave” does not apply to her experience with the disease because having cancer was never a choice or a wish for her to prove her bravery (1.2.3).

In conclusion, the article provides a number of reasons why the language we use to talk about cancer needs to be changed. The second part of the article mainly argues why we stop using the word “brave”Footnote24 for cancer patients; the first part of the article principally expresses resistance to the metaphors of “battle” and “fight” and the specific implications these metaphors are argued have. The author supports her resistance in support of 1.1 as well as 1.2 partly by arguing that cancer is not just a “fight” – it is an “unfair fight.” Here the author can be said to be extending the metaphor by drawing attention to the fact that fights are not always fair: If one party wins, this does not necessarily mean they fought hard enough or tried hard enough – other factors can play a role too (also see 1.1.1.1.1(n) and (1.2.1.)1a(n)); in the case of cancer the fact that patients or their healthcare providers do not have the means (or “arms”) to stand up to cancer and defeat it completely makes this metaphorical fight a fight between unequal combatants. I.e., addressees are asked to consider other features of the source domain to reinterpret the target issue at hand.

Discussion

The above case studies demonstrated how a detailed argumentative analysis offers a nuanced understanding of how metaphors can be extended in expressions of resistance to these metaphors. The argumentation structures provide detailed insight into the authors’ standpoints and arguments for resisting particular mappings, their arguments for retaining other mappings, and their arguments for interpreting the contested metaphor differently within the same source domain. The analyses also bring to light differences between the two cases when it comes to which parts of the contested metaphors are extended.

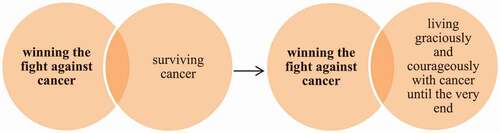

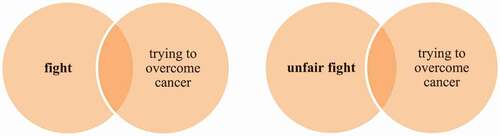

In case study 1, the author of the article reflects on what it means to “win” or “lose” the metaphorical fight against cancer. His arguments relate to the fact that participants in a fight can have different objectives – i.e., according to the author, contrary to what the “fight” metaphor implies, quite literally “surviving” is not the only way in which a fight can be won. below is a visual representation of how the metaphor of “winning the fight against cancer” is given a novel interpretation by applying it to another target domain situation (“living graciously and courageously with cancer until the very end”)

Figure 4. Source domain term (“winning the fight against cancer”) remains the same; interpretation of what this means in the context of the target domain situation is altered (“surviving cancer” > “living graciously and courageously with cancer until the very end”)

Figure 5. Source domain term is modified “‘fight” > “unfair fight”), target domain situation (“trying to overcome cancer”) remains the same

In the second case study readers of the article are also encouraged to understand the contested metaphor differently. In 2, attention is drawn to the fact that fights are not always fair; moreover, according to the author, the metaphorical fight against cancer should by definition be considered unfair. This is represented visually in .

In other words, both case studies draw attention to aspects of the metaphors’ source domain that are less commonly considered in the context of cancer. In case study 1, “winning the fight against cancer” is given a new meaning by applying it to another target domain situation; this example resembles the example of the household metaphor extension used in the experiments by Landau et al. (Citation2017). In case study 2 attention is drawn to an aspect of the source domain of violence that is less often foregrounded in the context of cancer through a specification of the (source domain) term “fight.” An example that is similar to the one in 2 is discussed in a paper by Barnden (Citation2016). It reads: “The Jerusalem Post … states that maintaining the delicate economic equilibrium isn’t merely like walking a tightrope, it’s like walking an invisible one” (p. 448 italics in original). Barnden discusses this as a very specific form of metaphor elaboration or extensionFootnote25 that he calls “elaborative correction” of metaphor. He notes how such an elaborative correction can be used to strengthen or cancel features of a metaphor’s source concept (p. 456). In the example of the tightrope the addition of the adjective “invisible” intensifies the picture of a difficult situation; in our second case study the addition of the adjective “unfair” can be said to (be meant to) undo implications of the initial metaphor about “losing the fight” and “not having fought hard enough” (see e.g. argument 1.1.1).

It is beyond the purpose of the current paper to delve deeper into all (theoretically) possible variants or patterns of metaphor extension and how they may function as ways to undo undesirable implications of a given metaphor. Comparative analyses of other occurrences of metaphor extension may give further insight into the different variants that may exist; as the current paper has shown, argumentative analyses of such occurrences in resistance to metaphor can improve our understanding of the reasons why metaphors are extended to replace particular implications by alternative ones. Our case studies provided two examples in which extensions of particular violence metaphors for cancer enabled the authors of the texts to replace (allegedly) inappropriate meanings of the contested metaphors by alternative ones.

Conclusion

This paper sought to examine how language users can use a metaphor extension approach to counter undesirable implications of violence metaphors for cancer without getting rid of these metaphors completely. The paper combined recent findings in metaphor research with two case studies on argumentative resistance to violence metaphors for cancer to explore how these metaphors can be interpreted in such a way that they are in line with language users’ (desired) perspective on the disease.

The two case studies examined expressions of resistance to violence metaphors for cancer that demonstrated features of metaphor extension: in both cases violence metaphors for cancer were criticized for implications about the metaphors’ target domain, and alternative interpretations were suggested that focused on other, less-considered aspects of the contested metaphors’ source domain. Instruments from the pragma-dialectical approach to argumentation analysis were used to gain a detailed insight into the precise arguments against particular implications of violence metaphors for cancer as well as the arguments in favor of alternative interpretations of the contested metaphors. The reconstruction of the argumentation structure in case study 1, for instance, demonstrated different main lines and subordinate levels of argumentation concerning a) the author’s arguments for resisting a particular metaphorical mapping; b) his arguments for retaining other mappings; and c) his “solution” to counter the implications of the contested mapping by extending it.

In sum, the close argumentative analyses in the two case studies provided novel insights about how language users can make use of metaphor extension to try and counteract allegedly undesirable implications of metaphor. Furthermore, the analyses in the two case studies revealed differences in the ways in which the contested metaphors were extended. We argued that these differences might point to different variants of metaphor extension, and that future research might look into this further by comparing different examples of extension in detail.

The current paper first and foremost aimed to demonstrate the added value of closely examining expressions of resistance to metaphor to pinpoint the precise metaphorical implications that are being contested in a given case of resistance as well as the alternative interpretations that proposed by the protagonists of the resistance. The study’s findings add to existing knowledge on argumentation about metaphor and resistance argumentation to metaphor in particular. The latter has recently received increased attention in studies examining how and when language users argue against the use of (particular) metaphor(s), and why (Finsen et al. Citation2021; Renardel de Lavalette et al. Citation2019; Wackers et al. Citation2020, Citation2021).

The study’s findings also add to the body of research on violence metaphors for cancer. Previous research has shown that violence metaphors for cancer can have different (positive or negative) effects on people who are faced with a cancer diagnosis. For terminal patients, for instance, metaphors to do with “losing the battle” can reflect or reinforce feelings of disempowerment or a negative sense of self (Semino et al., Citation2016). The current paper has demonstrated how language users can give novel interpretations to metaphors to replace more conventional interpretations they consider to be inappropriate. The findings can be used as a basis for further research on potential practical applications of metaphor extension as a means to counteract undesirable implications of violence metaphors for cancer.

One potential application may lie in methods for coping with cancer. As Gustafsson et al. (Citation2019) research findings demonstrated, the use of metaphor can both articulate and function as part of one’s coping process, the latter also including reinterpretation of what a metaphor means to the person in question. A possible, to be developed method aimed at helping people assign their own meanings to violence metaphors for cancer might be helpful for people those who experience negative effects of the more conventional implications of violence metaphors for cancer.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 In this paper we are not concerned with the question whether these implications are “true” or logically valid – the fact that they are drawn or felt to be drawn in communication about cancer forms the starting point of this study’s examination of expressions of resistance to violence metaphors for cancer.

2 Metaphorical expressions such as “she is fighting cancer”, “he lost his battle against cancer” or “we are at war with cancer” have been defined and labeled in different ways. They are sometimes referred to as “bellicose metaphors” (e.g., Hauser & Schwarz, Citation2015), “martial metaphors” (Reisfield & Wilson, Citation2004) or “violence metaphors” (e.g., Semino et al., Citation2015), to mention a few examples. In this paper we will make use of Semino and colleagues’ definition of violence metaphors for cancer as “any metaphorical expressions or similes whose literal meanings suggest scenarios in which, prototypically, a human agent intentionally causes physical harm to another human, with or without weapons” (Demmen et al., Citation2015, pp. 211–212).

3 Refusing to pick up on a metaphor used by someone else could be considered an example of resistance to metaphor too. This and other forms of criticism that are not expressed by means of (counter)argumentation will be left out of consideration here.

4 I.e., alternative as opposed to more conventional interpretations of violence metaphors for cancer. In our case studies start from the premise that what resisters argue (they think) are common interpretations of the metaphors in question can be considered more conventional than the alternative interpretations they propose. This means differences may exist among resisters about which interpretation of a metaphor counts as the most common or usual one and which interpretation is potentially novel.

5 Many studies have focused on violence metaphors for cancer in the English language, but research has also been done on the (common) use of these metaphors in languages other than English, including for instance Swedish (e.g., Gustafsson et al., Citation2019) and Spanish (Magaña & Matlock, Citation2018).

6 Semino et al. borrow the term scenario from Musolff (Citation2006) to refer to “(knowledge about) a specific setting, which includes: entities/participants, roles and relationships, possible goals, actions and events, and evaluations, attitudes, emotions, and the like” (Semino et al., Citation2016, p. 12).

7 As mentioned above, metaphorical expressions such as “fight” and “battle” have been defined and labeled in different ways in previous studies. What Gustafsson et al. (Citation2019) refer to as “battle metaphors” appear to match, to a great extent at least, with our definition of violence metaphors for cancer.

8 Similar observations have been reported in other studies, including the studies by Byrne et al. (Citation2002) and Demmen et al. (Citation2015). Byrne and colleagues found that cancer patients who used “language of effort, struggle or fighting” often used such language to express their “resistance […] to [their] emotional response to cancer” (Citation2002, p. 18). Demmen and colleagues also discuss a number of instances of metaphor use that describe a violent confrontation between the cancer patient and their emotions.

9 Also see Oswald & Rihs (Citation2014) for a study on the rhetorical and epistemic advantages as a result of metaphor extension.

10 Landau et al. (Citation2017) were inspired by a study done by Mio (Citation1996). In his (2006) study, Mio asked how one can effectively respond to a “[an] argument [that is built] around an incisive metaphor that has the potential of convincing the audience of [a particular standpoint]” (p. 127). In two experiments, he tested which response was more persuasive – one ignoring the metaphor, one using another metaphor in response, or one extending the metaphor that had been used in the initial argument. The study’s experiments provided overall support to Mio’s hypothesis that the extended metaphors were more effective persuasive devices compared to rebuttals based on literal statements or non-extending metaphorical ones (Ibid, p. 136). Taking Mio (Citation1996) findings into account, Landau et al. (Citation2017) raised the question under what conditions a metaphor extension strategy is particularly effective.

11 According to Landau et al. (Citation2017), this latter metaphor, legitimizing spending, is in line with recommendations of influential economists “[urging] stimulus spending to revive a flagging economy” (p. 77) and can therefore be seen as a more correct way of conceptualizing the federal budget; the metaphor extension offers a way to “undo” the allegedly inaccurate implication of the household metaphor that just as a family has to make sacrifices and cut spending to live within their means, the government should cut back on spending for federal programs.

12 This experiment formed but one part of Landau and colleagues’ study that sought to determine under what conditions a metaphor extension strategy is effective. The study ultimately concluded that the persuasiveness of the strategy is dependent on the epistemic benefit and saliency of the initial metaphor. If the metaphor in question is salient and increases the epistemic benefit of the metaphor by making the target issue easier to grasp, participants in Landau et al.’s study turned out to be more persuaded by a rebuttal that extended the household metaphor compared with a rebuttal that ignored that metaphor.

13 A detailed account of how the pragma-dialectical method for argument reconstruction deals with pragmatic phenomena such as presuppositions and implicatures is provided in A Systematic Theory of Argumentation. The pragma-dialectical approach (Van Eemeren & Grootendorst, Citation2004).

14 Pragma-dialectics adheres to the “principle of charity” in order to decide on one favored reconstruction when multiple reconstructions are plausible. According to this principle a reconstruction should not just be plausible but also the most likely to be successfully defended by the arguer. This principle is further specified into three practical strategies that can be followed by the argumentation analyst. These are the pragma-dialectical strategies of “maximally argumentative interpretation”, “maximally dialectical analysis”, and “maximally argumentative analysis” (Van Eemeren & Grootendorst, Citation1992). With the help of these strategies it can be determined whether a speech act can be interpreted as argumentatively relevant, whether a speech act can be considered a constructive move in a critical discussion, and whether an argument is to be reconstructed as multiple rather than coordinative, respectively (Ibid.).

15 The article has been published on the weblog Cancer Research 101 (http://www.michaelwosnick.com/blog/).

16 Only the parts of the original article that form part of the argumentation stage of the discussion (Van Eemeren & Grootendorst (2004) are included in the argumentation structure. For instance, the introductory paragraph in which the author discusses the occasion for his article has not been included.

17 For this structure as well as the structure in case study 2, some parts of the original text that could be split up further into different propositions have been (kept) grouped together under one larger, main proposition so to keep the structures more easy and clear to read.

18 See Van Eemeren and Grootendorst (Citation2004, p. 75 ff) about the “redundancy rule”, one of five rules Pragma-dialectics uses to determine the communicative intention of an utterance.

19 While it is not mentioned explicitly in the article, it is possible that the author means that some people may actually disagree with him here because they feel that they are in fact able to steer the outcome of their disease and “win the battle” according to the more conventional meaning of the metaphor – i.e., some people may hold the view that they can (and can be held responsible) to “win the battle against cancer” with the specific meaning of surviving the disease. This would not necessarily contradict the author’s reasons for resistance, but these people might not identify with the author’s wish to change the interpretation of what it means to “win” mentioned later on in the article. (I.e., in 1.2b.3(n) the author argues for a reinterpretation of “winning the battle against cancer” to include target domain situations in which people have died from cancer but have withstood other challenging aspects of the “battle” that having cancer brings on.)

20 The article has been published on the weblog When Life Goes Tits Up (https://whenlifegoestitsup.com/).

21 Similarly to case study 1 and in line with the pragma-dialectical approach to argument reconstruction, left out of the reconstruction are parts of the article that do not strictly form part of the argumentation, such as a non-argumentative introduction to the topic of the article or a repetition of its main ideas. In the reconstruction of case study 2 we omitted the lead paragraph that provides a brief summary of the main idea of the article.

22 In the pragma-dialectical approach to argument reconstruction, premises that have been left implicit in the original text but are relevant to the resolution of a difference opinion are added to the structure within parentheses For more information about the (pragma-dialectical) reconstruction of implicit premises, see Van Eemeren et al. (Citation2014) and Gerritsen (Citation2001).

23 While the word “brave” can apply to many situations in which people withstand adversity, it may be considered to be the epithet of a soldier in war (Annas, Citation1995, p. 745). The author of the article also considers “brave” to be part of the “language of war”. The word “journey”, on the other hand is another commonly used metaphor for cancer that has a different source domain than the domain of violence (see e.g., Semino et al. (Citation2015).

24 In addition, a few references are made to (the inaptness or inappropriateness) of using journey metaphors for cancer.

25 Barnden (Citation2016) discusses (relations between) different phenomena of metaphor use such as metaphor compounding, metaphor replacement, metaphor strength-modification, unrealistic source-domain situations, and metaphor elaboration. He notes that the latter phenomenon is often referred to as “metaphor extension” by others.

References

- Annas, G. (1995). Reframing the debate on health care reform by replacing our metaphors. New England Journal of Medicine, 332(11), 744–747

- Barnden, J. A. (2015). Open-ended elaborations in creative metaphor. In T. R. Besold, M. Schorlemmer, & A. Smaill (Eds.), Computational creativity research: Towards creative machines (pp. 217–242). Berlin: Springer.

- Barnden, J. A. (2016). Communicating flexibly with metaphor: A complex of strengthening, elaboration, replacement, compounding and unrealism. Review of Cognitive Linguistics, 14(2), 442–473. doi:https://doi.org/10.1075/rcl.14.2.07bar

- Byrne, A., Ellershaw, J., Holcombe, C., & Salmon, P. (2002). Patients’ experience of cancer: Evidence of the role of “fighting” in collusive clinical communication. Patient Education and Counseling, 48(1), 15–21. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0738-3991(02)00094-0

- Demmen, J., Semino, E., Demjén, Z., Koller, V., Hardie, H., Rayson, P., & Payne, S. (2015). A computer-assisted study of the use of violence metaphors for cancer and end of life by patients, family carers and health professionals. International Journal of Corpus Linguistics, 22(2), 205–231. doi:https://doi.org/10.1075/ijcl.20.2.03dem

- Finsen, A. B., Steen, G. J., & Wagemans, J. H. M. (2021). How do scientists criticize the computer metaphor of the brain? Using an argumentative pattern for reconstructing resistance to metaphor. Journal of Argumentation in Context, 10(2), 171–201.

- Fleischman, S. (2001). Language and medicine. In D. Schiffrin, D. Tannen, & H. E. Hamilton (Eds.), The handbook of discourse analysis (pp. 470–502). Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

- Gerritsen, S. (2001). Unexpressed premises. In F. H. van Eemeren (Ed.), Crucial concepts in argumentation theory (pp. 51–79). Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Gortan, R. (2016, March 9). Cancer doesn’t make you brave. Retrieved from https://whenlifegoestitsup.com/2016/03/

- Gustafsson, A. W., Hommerberg, C., & Sandgren, A. (2019). Coping by metaphor. The versatile function of metaphors in blogs about living with advanced cancer. Medical Humanities, 2019, 1–11.

- Haines, I. (2014). The war on cancer: Time for a new terminology. The Lancet, 383(9932), 1883. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60907-7

- Hauser, D., & Schwarz, N. (2015). The war on prevention: Bellicose cancer metaphors hurt (some) prevention intentions. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 41(1), 66–77. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167214557006

- Hendricks, R.K., Demjén, Z., Semino, E. & Boroditsky, L. (2018). Emotional Implications of Metaphor: Consequences of Metaphor Framing for Mindset about Cancer, Metaphor and Symbol, 33(4), 267–279, https://doi.org/10.1080/10926488.2018.1549835

- Landau, M. J., Keefer, L. A., & Swanson, T. J. (2017). “Undoing” a rhetorical metaphor: Testing the metaphor extension strategy. Metaphor and Symbol, 32(2), 63–83. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10926488.2017.1297619

- Macmillan Cancer Support. (2018). Missed opportunities. Advance care planning report. Retrieved from https://www.macmillan.org.uk/_images/missed-opportunities-end-of-lifeadvancecareplanning_tcm9-326204.pdf

- Magaña, D., & Matlock, T. (2018). How Spanish speakers use metaphor to describe their experiences with cancer. Discourse & Communication, 2(6), 627–644. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1750481318771446

- Mio, J. S. (1996). Metaphor, politics, and persuasion. In J. S. Mio & A. N. Katz (Eds.), Metaphor: Implications and applications (pp. 127–146). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Musolff, A. (2006). Metaphor scenarios in public discourse. Metaphor and Symbol, 21(1), 23–38. doi:https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327868ms2101_2

- Oswald, S., & Rihs, A. (2014). Metaphor as argument: Rhetorical and epistemic advantages of extended metaphors. Argumentation, 28(2), 133–159. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10503-013-9304-0

- Reisfield, G. M., & Wilson, G. R. (2004). Use of metaphor in the discourse on cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 22(19), 4024–4027. doi:https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2004.03.136

- Renardel de Lavalette, K. Y., Andone, C., & Steen, G. J. (2019). I did not say that the government should be plundering anybody’s savings: Resistance to metaphors expressing starting points in parliamentary debates. Journal of Language and Politics, 18(5), 718–738. doi:https://doi.org/10.1075/jlp.18066.ren

- Semino, E., Demjén, Z., Demmen, J., Koller, V., Payne, S., Hardie, A., & Rayson, P. (2015). The online use of violence and journey metaphors by patients with cancer, as compared with health professionals: A mixed methods study. BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care, 7(1), 60–66. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2014-000785

- Semino, E., Demmen, J., & Demjén, Z. (2016). An integrated approach to metaphor and framing in cognition, discourse, and practice, with an application to metaphors for cancer. Applied Linguistics, 39(5), 1–22.

- Sontag, S. (1989). AIDS and Its Metaphors. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux

- Van Eemeren, F. H. (2015). Reasonableness and effectiveness in argumentative discourse: Fifty contributions to the development of pragma-dialectics. Cham: Springer.

- Van Eemeren, F. H., Garssen, B., Krabbe, E. C. W., Snoeck Henkemans, A. F., Verheij, B., & Wagemans, J. H. M. (2014). Handbook of argumentation theory. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Van Eemeren, F. H., & Grootendorst, R. (1992). Argumentation, communication, and fallacies: A pragma-dialectical perspective. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Van Eemeren, F. H., & Grootendorst, R. (2004). A systematic theory of argumentation. The pragma-dialectical approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Wackers, D. Y. M., Plug, H. J., & Steen, G. J. (2020). Violence metaphors for cancer: Pragmatic and symptomatic arguments against. Metaphor and the Social World, 10(1), 121-140. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1075/msw.19005.wac

- Wackers, D. Y. M., Plug, H. J., & Steen, G. J. (2021). “For crying out loud, don’t call me a warrior”: Standpoints of resistance against violence metaphors for cancer. Journal of Pragmatics, 174, 68-77. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2020.12.021

- Wosnick, M. A. (2013, April 15). When Dealing With Cancer, “Loser” Language Doesn’t Work. Retrieved from https://www.michaelwosnick.com/when-dealing-with-cancer-loser-language-doesnt-work/