ABSTRACT

The appropriateness and persuasiveness of using metaphors has become subject of debate in both the academic and the public arena. Recent studies have shown that particular metaphors give rise to resistance, yet the nature of metaphor resistance is still hardly explored. This paper therefore examines the ways in which metaphors can be explicitly resisted, focusing on metaphors that are used in argumentative discourse. We propose an analytical tool, a typology of resistance to metaphor, to distinguish grounds for language users to reject unacceptable metaphors, based on the parameter of focus of the resistance and norms appealed to in the resistance. We applied the typology in a small corpus-analytical study using Twitter replies. Our results show that most resistance was based on discussion rules and focused on the proposition of metaphor, yet resistance focused on the situation, person or locution also occurred.

Introduction

Using metaphor is a common strategy in politics and other argumentative settings to support a particular claim or to promote behavioral change (e.g., Musolff, Citation2004). By painting a picture of the issue at hand, a metaphor may be a persuasive means of communication, in particular when this picture is new and fits the topic (e.g., Sopory & Dillard, Citation2002). Nevertheless, as Lakoff and Turner (Citation1989, p. 69) pointed out, language users may question conventional metaphorical representations based on their “inadequacy”. If the chosen metaphor is problematic to the audience for some reason, it may evoke resistance: people might object to or even attack the metaphor (e.g., Hauser & Schwarz, Citation2015).

An instance of an argumentative metaphor that triggered such resistance was used on September 15th, 2019 by former UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson in an interview with The Mail on Sunday on the UK negotiations about leaving the European Union. Johnson argued that he would manage to achieve a Brexit by comparing the UK with Marvel character Bruce Banner, who transforms into the powerful Hulk when emotionally stressed. “Banner might be bound in manacles, but when provoked he would explode out of them,” Johnson said. “Hulk always escaped, no matter how tightly bound in he seemed to be – and that is the case for this country. We will come out on October 31 and we will get it done.”

In the Hulk metaphor, words referring to the violent Hulk are used in the context of European politics. It can therefore be regarded as a cross-domain mapping (Lakoff & Johnson, Citation2003), in which the more abstract, complex topic of relations between the EU and the UK (from the target domain of politics), is thought and talked about in more concrete, familiar terms by referring to Bruce Banner and his manacles (from the source domain of Marvel comics). In this example, the metaphor directly links the two domains, resulting in a direct metaphor (cf. Steen et al., Citation2010). The use of the Hulk metaphor was publicly criticized in the (social) media, among others by American actor Mark Ruffalo, who played the character of Banner/the Hulk in several Marvel movies. Ruffalo posted a tweet that same day, including a picture of the interview with Johnson in the Mail on Sunday (MoS), and dismissed the metaphor. His resistance to the metaphor manifests itself in several ways: Ruffalo points at characteristics of the Hulk that do not apply to the UK by stating that “the Hulk only fights for the good of the whole,” but he also warns that being like the Hulk is not necessarily a good thing (“mad and strong can also be dense and destructive”). These reactions show that resistance can focus on different aspects of a metaphor.

In recent years, more and more attention has been given to problematic metaphor use and resistance to it. Gibbs and Siman (Citation2021), for instance, discuss a wide range of ways in which metaphor resistance unfolds, from individually to publicly, consciously to automatically, partly to completely, and can be addressed to the content of the metaphor, the linguistic instantiation of it, or the effects it has. Resistance becomes even more relevant when metaphors have a negative individual or social impact (e.g., Al-Saleem, Citation2007; Hauser & Schwarz, Citation2015; Reisfield & Wilson, Citation2004; Semino, Citation2021; Semino et al., Citation2017). It is therefore important to become aware of the downsides of using metaphor, and determine what aspects of metaphor use may evoke resistance of some sort. However, so far, the various manifestations of different types of resistance have not been systematically uncovered.

The present paper aims to fill this gap by proposing an analytical instrument, in the form of a typology of theoretically distinguishable types of resistance. We will specifically focus on the use of metaphor in argumentative discourse, where the metaphor is used in a discussion to persuade the interlocutors to change their attitude and/or behavior. Based on Steen’s (Citation2008, Citation2011) model of metaphor, the pragma-dialectical theory of argumentation (van Eemeren & Grootendorst, Citation2004) and Krabbe and van Laar’s (Citation2011) approach to critical reactions, we will outline the ways in which antagonists can, in theory, resist a metaphor by explicitly criticizing it. The typology we propose, helps to distinguish in what ways resistance to metaphor in argumentative discourse can manifest itself. To illustrate the types of resistance distinguished in the typology, we carried out a corpus analysis of resistance to metaphors in Twitter replies.

Section 2 will first elaborate on the concept of resistance and what resistance to metaphor amounts to. Section 3 introduces parameters for distinguishing critical reactions to metaphor. These will be illustrated with examples of Twitter replies. Section 4 contains the methodology of the corpus analysis. Section 5 discusses the results and Section 6 contains a conclusion and discussion of the ways in which metaphors can be explicitly resisted.

Resistance to metaphor

Metaphor in argumentative discourse

Johnson’s Hulk metaphor shows that metaphors are not just cross-domain mappings, functioning on a conceptual level and being expressed on a linguistic level (e.g., Johnson in the Mail on Sunday: “We’ll break free of the EU like the Incredible Hulk”), they are also used with a certain purpose in mind on a communicative level (e.g., persuasion). Steen (Citation2008) distinguishes these three functional levels as dimensions in his 3D-model of metaphor and analyzes how different types of metaphors can be distinguished on each of these dimensions (e.g., novel and conventional metaphors on the conceptual level, direct and indirect metaphors on the linguistic level, and deliberate and non-deliberate metaphors on the communicative level).

Here, we adopt a broad conception of metaphor. Following Steen (Citation2008, Citation2011), metaphor is conceptually seen as a cross-domain mapping that may be expressed linguistically in various ways: as an explicit simile that directly expresses how propositions belonging to distinct domains are connected through the use of comparison indicators such as “like” and “as” (as in Johnson stating that the UK “is like the Hulk”), but also as an indirect metaphor expressed through a single word that has a contextual meaning that differs from its more basic, concrete meaning (Johnson: “the manacles of the European Union”). Deliberate metaphors hold our specific interest, since they can have a clear argumentative purpose and are typically linguistically marked; therefore they may also be more prone to criticism and resistance.

The argumentative purpose of metaphors in general has been subject to earlier studies, both from the perspective of metaphor studies (Charteris-Black, Citation2013; Musolff, Citation2016) and argumentation studies (e.g., Oswald & Rihs, Citation2014; Pilgram & van Poppel, Citation2021; van Poppel, Citation2020a; Wackers, Plug, & Steen, Citation2021; Wagemans, Citation2016). Argumentative discourse emerges when two or more parties attempt to resolve an (anticipated) difference of opinion by advancing arguments to support their standpoint (van Eemeren & Grootendorst, Citation1992). Using the pragma-dialectical theory of argumentation developed by van Eemeren and Grootendorst (Citation1992), such discourse can be reconstructed as an argumentative discussion in which parties perform various moves, such as advancing arguments and critical reactions.

Metaphors can be part of distinct argumentative moves that are aimed communicatively at resolving a difference of opinion. They can be used as part of the standpoint at hand (e.g., “We should launch a war on Covid-19”), in arguments (e.g., “Stricter measures against COVID-19 should be taken, because there is a tsunami of Covid-patients”), but can also be part of the starting points, the common ground, that underlie the discourse (using terms like “tsunami” to imply an analogy between immigration and disaster) (see Renardel de Lavalette, Andone, & Steen, Citation2019; van Poppel, Citation2020a; Wagemans, Citation2016). The different roles that metaphors can fulfill in argumentative discourse are important to keep in mind when analyzing resistance to metaphors in such discourse, as these different roles might result in different types of resistance and might have different consequences for the discussion. Before specifically going into resistance to metaphor, let us first discuss different conceptions of resistance and then clarify what we mean by it.

Resistance

“Resistance” is a common term in persuasion research and captures various phenomena. It is, for instance, seen as a property of an attitude, as counter-arguing, and as ineffective persuasion (Wegener, Petty, Smoak & Fabrigar, Citation2004, p. 18). In general, one could say that when persuasive messages are unsuccessful, this is due to the fact that they meet some kind of resistance.

Knowles and Linn (Citation2004, p. 5) make a distinction between outcome resistance (in which there is simply no persuasive effect) and motivational resistance (in which the persuadee avoids being persuaded). Outcome resistance thus entails a persuasion attempt that does not alter the target’s attitude or behavior. Motivational resistance happens when the persuasion attempt is met with strategies or reactions aimed at impeding or reducing attitudinal or behavioral change (e.g., counter-arguing, trying to avoid the message; see also Fransen, Smit, & Verlegh, Citation2015). These types of resistance are of course linked: motivational resistance could lead to outcome resistance. Yet, each can also occur separately, which is why it is useful to distinguish them analytically.

A resisted persuasion attempt does not always evoke resistance in the same way. Whether and in what way a recipient resists such an attempt depends on (i) the personal beliefs, values and qualities of the recipient (see Briñol, Rucker, Tormala, & Petty, Citation2004), (ii) the exact attitudinal or behavioral change called for in the persuasion attempt (see Brehm, Citation1966; Miron & Brehm, Citation2006), and (iii) the way in which the persuasion attempt is made (see Hakim, Kurman, & Eshel, Citation2017). This third factor is of primary interest to the present research.

In the remainder of this paper, we will focus on the ways in which metaphors in argumentative discourse are resisted. To determine the kinds of criticisms that are brought forward in reaction to metaphors, we will focus on motivational resistance that is explicitly expressed. This means that, in this study, resistance is understood as the individual, explicit utterance of non-acceptance or criticism of the interlocutor’s metaphor use. Our definition consequently excludes some forms of resistance as described by Gibbs and Siman (Citation2021), such as collective or unconscious metaphor resistance.

Possible triggers of resistance to metaphor

Up until now, it remains unknown what exactly triggers resistance to metaphor. Gibbs and Siman (Citation2021, p. 671) hint at several factors, “from their sensory-motor components to their emotional valence, cultural implications, or their metaphorical nature altogether (in preference for literal language).” Metaphors may also go against people’s moral values, as they may be based on diverging ideological frameworks (Lakoff, Citation2002).

From the extant persuasion literature, we can infer that certain aspects of a metaphor diminish its persuasiveness and thus may trigger resistance. In their meta-analysis, Sopory and Dillard (Citation2002) show that metaphors that were extended, conventional, and used unfamiliar target domains were less persuasive than their counterparts which were not extended, novel, or which used a target with which the audience was familiar. Especially the lack of persuasiveness of extended metaphor – i.e., the use of the same source domain in several metaphorical expressions – seems surprising (cf. Sopory & Dillard, Citation2002, p. 389). As Oswald and Rihs (Citation2014) for instance argue, each additional metaphorical expression in an extended metaphor validates the cross-domain mapping and could thus increase persuasiveness. Nevertheless, the meta-analysis did not confirm this expectation. However, in a more recent meta-analysis, van Stee (Citation2018), did not find any difference in persuasive effect of non-extended and extended metaphors, suggesting that metaphor extension might not play a role in resistance to metaphor either.

The same holds for the positive effect of novelty of metaphors on persuasiveness; in contrast to Sopory and Dillard (Citation2002), van Stee (Citation2018) did not find this effect. However, van Stee’s (Citation2018) meta-analysis did confirm the effect of familiarity with the target domain. This suggests that the use of an unfamiliar target domain in metaphor could trigger resistance to that metaphor.

Apart from factors that directly affect metaphor’s persuasiveness, there are also aspects of metaphor that are likely candidates to indirectly do so. One such indirect factor is metaphor aptness. Metaphor aptness refers to the extent to which the metaphor captures the key features of its target. This requires the selection from the source domain in the metaphor to be (i) a salient property of this source domain and, additionally, to be (ii) relevant to what the metaphor aims to convey about the target domain (Jones & Estes, Citation2006, p. 19). As such, the adequacy of a metaphor (cf. Lakoff & Turner, Citation1989) can be described in terms of aptness. Jones and Estes (Citation2006, pp. 24–27) show that apt metaphors are faster and more easily comprehended than less apt metaphors. Aptness is therefore said to mediate metaphor comprehension and can, by extension, be expected to affect metaphor’s persuasiveness. Related to aptness is the “fit” of the metaphor: Landau, Arndt, and Cameron (Citation2018) found that metaphor had a larger effect when both problem and solution were framed using the same metaphor. So, the use of an unfamiliar target domain and a metaphor’s limited aptness or fit might play a role in resistance to metaphor.

Types of explicit metaphor resistance

Resistance to metaphor as a critical reaction

Explicit motivational resistance to metaphor could show for what reasons metaphors are resisted. As we are focusing on metaphors in the context of an argumentative discussion, we interpret resistance in a specific way, namely as a critical reaction to a discussion move (see Renardel de Lavalette, Andone, & Steen, Citation2019). A critical reaction is defined by Krabbe and van Laar (Citation2011) as a verbal reaction expressing a negative evaluation of (part of) a move in a discussion. The reaction should contribute some content to the discussion; thus, slapping the opponent in the face could be interpreted as a negative evaluation, but does not add critical content. This concept of critical reaction fits our approach to resistance to metaphor as an explicit expression of non-acceptance very well.

Krabbe and van Laar (Citation2011) have proposed four parameters to characterize critical reactions in argumentative discourse, namely: the focus of a critical reaction, the norm to which it appeals, the particular illocutionary force of the speech act expressing the criticism, and the particular level of dialogue at which it occurs. The parameters of focus and norm describe in fact what part of the discourse the criticism responds to is problematic and for what reason. The parameters of illocutionary force and level characterize the way in which the criticism is expressed. Since the goal of the current paper is to shed more light on the potential problematic aspects of metaphor use and not on the way in which these problematic aspects are conveyed, we will direct our attention to the parameters of focus and norm.

The focus of a critical reaction refers to what move and which aspect of the move the reaction is aimed at. A critical reaction can address various aspects of a move. As Krabbe and van Laar (Citation2011) argue, an argumentative move has a particular propositional content that is expressed by means of a locution by a particular person in a particular context. Each of these aspects of a move can be addressed, so that the focus of a critical reaction can be propositional, locutional, personal or situational. The second parameter is the norm to which a critical reaction appeals.Footnote1

Krabbe and van Laar’s (Citation2011) parameters are generally applicable to all types of critical reactions to all types of argumentative moves, not just argumentatively used metaphors. In the following section, we will nonetheless take the theoretically distinguished parameters of focus and norms and use and specify them to distinguish types of critical reactions to metaphor.

Focus of resistance

Types of moves

Krabbe and van Laar (Citation2011, p. 204) explain that the focus of a critical reaction in general can be on elementary moves, such as standpoints or arguments, but also on combinations of moves, such as argumentation consisting of a series of interconnected arguments, or only on part of a move, such as a (string of) word(s). Metaphors can be part of a move when they are used indirectly, but they can also constitute entire moves in the form of an explicit metaphorical comparison or simile, and can even stretch over several moves when the metaphor is extended. We argue that, to get to the bottom of resistance to metaphor, analyzing a critical reaction to a metaphor should thus include determining at what type of move the resistance is directed: part of a move, one entire move, or a combination of moves.Footnote2 Apart from the type of move, the resistance can be either propositional, locational, personal or contextual.

Aspects of the move

Propositional resistance to metaphor

A propositional critical reaction entails that criticism is directed at the content of a proposition. Such criticism can be specified by using the so-called critical questions pertaining to the argument scheme in question, which are used to evaluate the appropriate and correct use of the argumentation (Krabbe & van Laar, Citation2011, p. 205).

In the case of a metaphor conveying a proposition that functions as a premise in an argument, the type of argumentation, or argument scheme, that can be used is that of figurative analogy argumentation. This argument is used to defend a standpoint by comparing the situation in the standpoint with a situation in the argument that stems from a different domain than the one in the standpoint (Garssen & Kienpointner, Citation2011, p. 40). Especially metaphors that are used deliberately, that is, to be taken up as a metaphor by the opponent, are likely to be used in analogy arguments (van Poppel, Citation2020b).

Various argument typologies include the analogy argument and propose a set of critical questions for it (e.g., Garssen & Kienpointner, Citation2011; Schellens, Citation1985; Walton et al., Citation2008). If a metaphor is used as an analogy argument, criticism could focus on the material (or minor) premise or the connecting (or maior) premise of the argument. The material premise tends to describe a particular state in the source domain while the connecting premise expresses the relation between source and target domain (van Poppel, Citation2018). Critical questions focusing on the material premise address its acceptability, while those focusing on the connecting premise address the comparability of the cases introduced in the standpoint and the argument (Garssen & Kienpointner, Citation2011).Footnote3

These questions are at the heart of determining a metaphor’s aptness in argumentation. Recall that aptness of a metaphor depends on two factors: the salience of the elements from the source domain in the recipients’ mind and the relevance of these elements to what is being said about the target domain (see Section 2.3).

The distinction between resistance to metaphor focusing on the material and connecting premise can be illustrated as follows. Imagine that someone tries to comfort a cancer patient with “You will be okay, because fighters defeat anything.” The speaker can be regarded to support “You will be okay” (standpoint 1) by means of “Fighters will defeat anything” (argument 1.1) and “You are a fighter” (connecting premise 1.1’). To evaluate this, one should ask whether fighters will indeed defeat anything (about material premise 1.1), and whether the addressee is really a fighter (about connecting premise 1.1’). Although violence metaphors are quite abundant in discourse about cancer (see Hauser & Scharwz, Citation2019), these have also been criticized (cf. Semino et al., Citation2017). Indeed, Grainger (Citation2014), a geriatrician who suffered from cancer, states: “In my world, having cancer is not a fight at all. It is almost a symbiosis where I am forced to live with my disease day in, day out.” Grainger’s resistance would amount to negatively answering the critical question about the connecting premise. This is distinct from focusing on the material premise, which could be questioned through something like: “But fighters do not always win, do they?”

Locutional resistance to metaphor

Critical reactions can also focus on its locution, i.e., the formulation of the propositional content or its illocutionary force (Krabbe & van Laar, Citation2011). When this is a move involving a metaphor, such criticism mainly concerns the understandability of the metaphor; its formulation can be considered unclear, but also biased, or distasteful. A locutional critical reaction could thus involve criticism regarding the use of certain words which are unclear (e.g., “What does he mean by ‘wrestle to the floor’?”) or inappropriate (e.g., ‘You shouldn’t call women “girls”).

Personal resistance to metaphor

A critical reaction can also focus on the person presenting the move. If a person uses a metaphor, they could, for instance, be accused of not being in the position to use that particular metaphorical expression because of a personal flaw or bias. An example of such a reaction would be: “You shouldn’t refer to war; you have no idea what that’s like.” In terms of the pragma-dialectical discussion rules, such a critical reaction leveled at the person could be evaluated as an ad hominem fallacy (of the tu quoque variant), because the character or previous behavior of the one advancing a standpoint is not relevant for determining the acceptability of that standpoint (Garssen, Citation2009).Footnote4 Although such criticism is unreasonable according to pragma-dialectical norms, in day-to-day discourse, people do expect people’s utterances and behavior to be consistent with one another.

Situational resistance to metaphor

A situational critical reaction addresses circumstances within or outside of the discussion which make the proponent’s move inappropriate (Krabbe & van Laar, Citation2011). A metaphor could be judged inappropriate at a particular moment in the discussion, for instance, when presenting a war metaphor in the current political context may lead to a division in society or even violence. A critical reaction could then refer to the external circumstances to resist the metaphor at hand.

Norms appealed to in resistance

The second parameter proposed by Krabbe and van Laar (Citation2011) is the norm to which a critical reaction appeals. As a critical reaction focusing on a metaphor involves a negative evaluation of it, there is always some kind of norm or criterion appealed to. Krabbe and van Laar (Citation2011) distinguish three different types of norms, namely norms expressed in the rules for a critical discussion, norms for optimality, and institutional norms. Again, we will specify what these mean for moves involving metaphor.

In terms of the pragma-dialectical argumentation theory, the rules for a critical discussion are norms for conducting a reasonable, constructive discussion (see van Eemeren & Grootendorst, Citation1992). They are used to differentiate between reasonable and fallacious moves (e.g., shifting the burden of proof, using invalid arguments, committing ad hominem fallacies, etc.). When applied to the use of metaphors in argumentative discourse, we propose to interpret these rules as general norms to determine whether a metaphor in a discussion move could, in principle, contribute to the resolution of a difference of opinion, or hinder (or even obstruct) such a resolution. These norms are not typically referred to explicitly in the discourse. For example, people responding to a metaphor with remarks like “That doesn’t hold” or “That’s completely different” only implicitly appeal to some norm for argumentation, namely that the compared cases are sufficiently similar. Such reactions appeal to an argument scheme rule, which prescribes that a standpoint should be defended by means of an appropriate and acceptable argument scheme (see van Eemeren & Grootendorst, Citation2004).

Norms of optimality can be interpreted as rules differentiating between metaphors that are used well and unsatisfactorily; the latter being metaphors that are not regarded as fallacious moves, but as blunders, because they are not as effective as they could have been in reaching the speaker’s goals. Unsatisfactory metaphors for instance use an unfamiliar source domain or have limited aptness or fit (see Section 2.3). According to Garssen and Kienpointner (Citation2011, p. 47), an effective figurative analogy makes use of a source domain (or “phoros”) that is easy to grasp and that is familiar to the intended audience, and acceptable at first sight.

Lastly, we take institutional norms to differentiate between metaphors that are appropriate in the particular context in which the discussion takes place and those that are not. In general, inappropriate moves (e.g., introducing illegally obtained evidence as a starting point in a legal discussion) are regarded as faults (Krabbe & van Laar, Citation2011, p. 206). In certain contexts, it could be inappropriate to use source domains that are sensitive or use metaphors at all (e.g., the source domain of WAR when talking about cancer, see Hauser and Schwarz (Citation2015)).

Using these parameters, a critical reaction can for instance be described as appealing to rules for a critical discussion and as being focused on the discussion situation in which a metaphor is used, while another critical reaction may appeal to institutional norms and may focus on the locution of a particular metaphor.

A typology of resistance to metaphor

The parameters of focus and norms, as distinguished in general by Krabbe and van Laar (Citation2011), are the basis for our typology specified for resistance to metaphor presented as .

Table 1. Typology of resistance to metaphor.

Methodology

The corpus: reactions to Johnson’s ‘Virus is a Mugger’ Metaphor

To illustrate what types of resistance to metaphor actually occur, we used our typology of resistance (see Section 3.4) to analyze a corpus of twitter posts. We have collected all 196 direct replies, all from the same day, to one tweet from Channel 4 News (@Channel4News) from April 27, 2020 (see example 1).Footnote5 This tweet reported on a public statement by former UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson about the COVID-19 pandemic. It was selected because it reported on a very clear metaphor used by Johnson, which was widely taken up as metaphor and commented upon in the media (Kirkup, Citation2020; Peck, Citation2020; Shariatmadari, Citation2020) and in the replies on Twitter. The tweet quoted the metaphor and included a link to the video recording of the statement. The replies did not only address the short fragment cited in the tweet, but also other parts of Johnson’s statement, implying that at least some of the Twitter users indeed looked at the statement. For convenience’s sake, we added a full transcript of the excerpt that is partly cited in the tweet next to the depiction of the tweet itself.

The tweet reports on Johnson’s public statement made on April 27th 2020 in front of Downing Street 10. At that point, Johnson had been absent for three weeks due to a serious Covid infection for which he needed treatment in hospital. The statement was made during the first phase of the COVID-19 pandemic when the UK had imposed strict regulations, such as a lockdown and social distancing rules. In the statement, Johnson urged the public to keep on adhering to the implemented regulations. To justify this call, Johnson used a metaphor in which he compared the COVID-19 virus to an assailant, an “invisible mugger.” Based on MIPVU, this can be seen as an instance of (extended, direct) metaphor, as two concepts from distinct domains are compared (Steen et al., Citation2010, pp. 14–15): several elements from the source domain of violence (“physical assailant,” “mugger,” “wrestle”) are presented as analogous to COVID-19 and containing the virus.

(1)

To be able to distinguish the focus of the resistance to Johnson’s metaphor and the norms appealed to, we first need to reconstruct how the metaphor is instantiated by Johnson and in what types of moves (e.g., standpoint or supporting arguments) the metaphor is used. This is done by using the pragma-dialectical method of argument analysis (van Eemeren & Grootendorst, Citation1992, Citation2004).

The standpoint that can be extracted from the speech fragment is “This is the moment of opportunity to beat COVID-19 together.” It can be inferred from the conditional statement in the speech that this standpoint is supported by the argument “This is the moment when we have begun together to wrestle COVID-19 to the floor.” This implicit argument follows from the conditional argument “If this virus were a physical assailant, an unexpected and invisible mugger, then this is the moment when we have begun together to wrestle it to the floor” and the statement which confirms the condition that the “virus indeed is an invisible mugger.” This last argument is subordinately supported by Johnson’s personal assurance, based on his experience with being ill with Covid. This part of Johnson’s argumentation can be represented in an argumentation structure, as depicted in .

Analysis of resistance to metaphor

To describe the types of resistance in our corpus, each of the authors has coded the replies on the two parameters of focus and norms. First, we determined for each reply whether it focused on part of one of Johnson’s moves, on a single move or on a constellation of moves (as represented in ). Then, we determined whether the resistance was focused on the proposition, the locution, the person (i.e., Johnson) or the situation (i.e., the time and place the public statement was held). Additionally, we coded for the norms that the resistance appealed to: discussion rules, optimality norms or institutional norms. Note that each Twitter reply could contain various critical comments and could therefore be coded for multiple categories (for instance focusing on both proposition and location, or appealing to both discussion rules and optimality norms).

The entire corpus was coded in two rounds by the two coders. After the first coding round, a number of diverging analyses were discussed. For example, since norms are often only implicitly assumed, we decided that replies that commented on the truth or acceptability of (part of) Johnson’s metaphorical statements, or the comparability of the source and target, should be considered as appeals to discussion rules. In addition, we encountered several replies in which criticism toward metaphors in general was expressed. Therefore, we included general criticism as a separate category. Subsequently, a second round of independent coding of the data was performed, resulting in substantial agreement between the two coders (κ = 0.80).

Results of the analysis

Metaphor resistance in the Twitter data

All the direct replies to the Channel 4 News’s tweet reporting on Johnson’s public statement on April 27, 2020 included some form of resistance. Given the rather antagonistic nature of Twitter, this might not come as a surprise. More interestingly for our paper is the part of the tweet that the resistance is aimed at. In the majority of the cases (76.5%, see ), this resistance is not aimed at Johnson’s metaphor use. In those tweets, Johnson’s policies are, for example, criticized (“He also said, ‘many people will be looking at our apparent success’ with #Covid19. This is at best #Bollocks”) or Johnson himself is under attack (“Aah. How I’ve missed Bodger chatting shit”). In the remainder of the tweets (23.5%, see ), the resistance is aimed at Johnson’s use of the “mugger metaphor.”

Table 2. Overview of the direction of the resistance in the tweets directly reacting to the Channel 4 News tweet reporting on Johnson’s statement on April 27, 2020.

provides an overview of the 46 tweets that resist Johnson’s mugger metaphor on the parameters as distinguished in our typology (see Section 3.4). We will discuss these outcomes in more detail in the subsequent sections.

Table 3. Overview of the types of resistance to metaphor in the tweets resisting Johnson’s “mugger metaphor”.

Resistance to metaphor: Type of move

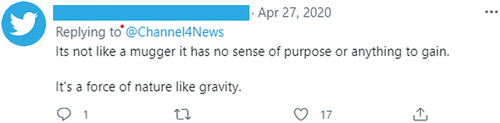

The corpus contained resistance to metaphor focused on parts of moves (8.5%), single moves (66.0%) and constellations of moves (25.5%). The following response to Johnson’s speech, example (2), contains a critical reaction focused on argument (1.1).1, thus focusing on a single move presented by means of Johnson’s argumentatively used metaphor. In this reaction, the twitterer denies that the virus is a mugger and provides an explanation for this denial.

(2)

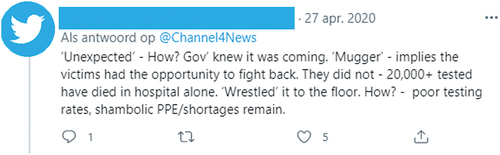

In other cases, a particular part or parts of a move can be subject to criticism. In example (3), the author in fact criticizes multiple parts of several of Johnson’s moves.

(3)

In example (3), the author mainly criticizes the argument (1.1).1: the twitterer expresses resistance toward Johnson calling the mugger “unexpected” and argues why this is incorrect. In addition, the twitterer resists the use of the words “mugger” and “wrestled.” As can be seen here, the criticism does not attack the complete cross-domain mapping, i.e., the metaphor “the virus is a physical assailant, an unexpected and invisible mugger,” but rather only some aspects of the way in which Johnson describes the situation.

Other Twitter reactions may also contain criticism regarding Johnson’s metaphor use in general, for instance in example (11), discussed in Section 5, which questions the effectiveness of metaphors at large. In such cases, the critical reactions address a complex of moves.

Resistance to metaphor: Aspect of the move

Replies with propositional resistance

In the majority of cases (80.5%), the critical reaction was propositional, i.e., the criticism is directed at the content of a proposition. Example (2) above illustrates a clear case of such resistance: it negates the analogical relation that was drawn by Johnson between the virus and a mugger by stating that the virus lacks a crucial correspondence with a mugger, namely “a sense of purpose.” More specifically, the critical reaction focuses on the propositional content of Johnson’s move in which the metaphorical comparison between the virus and a mugger is introduced (argument (1.1).1). This type of reaction is perhaps the most straightforward criticism of a metaphor: it questions the analogy relation between two domains the metaphor is based on (and, in this case, also introduces an alternative perspective on the virus as “a force of nature like gravity”). Johnson’s analogy between the virus and a mugger involves certain correspondences, such as a threat, someone confronting the threat, possible harm to the body, and a need for action. If crucial elements are missing in either domain, the analogy becomes problematic and may be called out, as is done in the critical reaction in example (4).Footnote6 Overall, this kind of resistance to the analogy relation occurred in 19.6% of all cases of metaphor resistance.

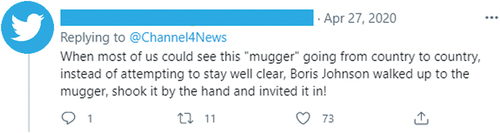

Most propositional critical reactions to metaphor were aimed at the representation of the source domain itself (60.9% of all metaphor resistance cases). For instance, in example (4), the mapping between the virus and a mugger itself is not questioned, but the scenario selected from the source domain is, implying that the twitterer did not agree with Johnson’s original metaphor use.

(4)

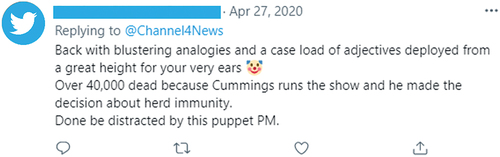

Replies with locutional resistance

Locutional resistance, focusing on the formulation of propositions, did not occur very frequently in our data; only 10.9% of the metaphor resistance in the tweets was focussed on the locution. One case of locutional criticism responding to Johnson’s speech is presented as example (5). In this Twitter reaction, Johnson is criticized for using “blustering analogies and a case load of adjectives.” The criticism clearly focuses on the choice of words, and in particular the fact that metaphors are chosen, instead of on the content of Johnson’s speech.

(5)

Resistance regarding the locution is also hard to disentangle from propositional criticism. Some reactions, for instance, accused Johnson of using “inappropriate” or “strangled” metaphors. Such negative evaluative terms could imply that the chosen wording is not optimal, but also that the chosen source domain is not apt for drawing conclusions on the selected target domain.

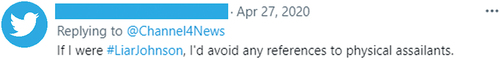

Replies with personal resistance

Personal resistance was observed in even fewer cases (4.3%). Such resistance occurs in example (6), in which Boris Johnson is indirectly accused of being in no position to use his “mugger metaphor.” The tweet indicates that Johnson should not refer to “physical assailants,” such as a mugger. The tweet was accompanied by an image (which is no longer available on Twitter) of Johnson knocking over a 10-year old boy in a friendly rugby match during a trade visit to Japan in 2015 when he was the Mayor of London. In combination with the image, the twitterer implies that Johnson is a physical assailant himself and thus should not describe the virus as such.

(6)

Replies with situational resistance

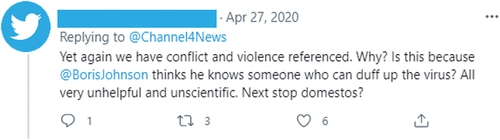

Lastly, the focus of a critical reaction can be on the situation, which occurred in only 4.3% of cases of resistance to Johnson’s mugger metaphor. The tweet in example (7) illustrates a reaction with a situational focus, as it addresses possible problematic consequences of using the mugger metaphor. The tweet seems to imply, via a rhetorical question, that the “bellicose, bombastic call to arms” may be ineffective, or perhaps even counterproductive. This criticism thus seems to appeal to norms of optimality in the particular situation of Johnson’s address to the public.

(7)

In the reply in example (8), the conflict and violence language is questioned. Here, it is argued that the violence metaphor is “very unhelpful and unscientific,” which implies that in the particular situation of a public address during a pandemic, the language used should be helpful and scientific. Interestingly, the reply ends with the remark “Next stop domestos?.” “Domestos” is a brand of bleach, so this tweet presumably alludes to former US president Donald Trump’s suggestion to use bleach to combat a COVID-19 infection. The language of violence may thus lead to further unscientific proposals.

(8)

Resistance to metaphor: Norms

In our data, the type of norms that was (indirectly) appealed to most in tweets resisting Johnson’s mugger metaphor is discussion rules (83%). We observe such indirect appeals to argumentative norms in example (3), for instance in the fragment “’Unexpected’ – How?.” Here, the author of the tweet questions the acceptability of one of Johnson’s statements and rhetorically requests further justification of this point.

Optimality norms, which distinguish between successful and unsuccessful arguments, are appealed to 8 times (17%). Example (8) reflects a critical reaction that appeals to optimality norms as the tweet points out that the chosen source domain of violence/war is not helpful and does not meet assumed optimality norms.

The third type of norms, institutional norms, was not appealed to in our data of resistance to metaphor. Some critical replies did refer to such norms, but these were not replies directly attacking Johnson’s metaphor, so these cases were not taken into account. These replies for instance referred to certain rules that politicians would need to abide by in their role as participants in public discussions, such as speaking clearly and not using “rhetoric.”

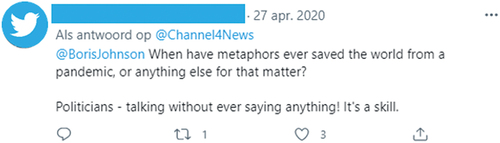

General criticism of metaphor

Lastly, in 7 cases (15.2%), not just Johnson’s “mugger metaphor” is resisted, but metaphors in general (including his “mugger metaphor”): they are supposedly ineffective (an indirect appeal to an optimality norm) (see also Gibbs & Siman, Citation2021). In contrast with more specific forms of resistance, such as in examples (7) and (8), example (9) shows that the strategy of using metaphors argumentatively is called into question, rather than just the particular metaphor at hand.

(9)

Discussion of the results

The examples discussed in the previous chapter illustrate that resistance to metaphor can focus on the premise, formulation, person, or circumstances in which this metaphor is used. Twitter users reacting to Johnson’s metaphor, for instance, criticized the comparison made between the domains of criminality and disease (a focus on the proposition), but also attacked Johnson for using this particular metaphor (a focus on the person).

Additionally, the examples show that different types of norms, based on Krabbe and van Laar (Citation2011), can be appealed to in resistance to metaphor in practice. Most of the resistance to metaphor in our corpus appealed to argumentative norms, as twitterers, for instance, require statements to be truthful or that there should be enough similarities between the domains compared, while others appeal to more practical norms of optimality, such as the helpfulness of a metaphor and the suitability of Johnson. Furthermore, some resistance also appealed to specific norms for politicians in this public debate on pandemic measures.

However, the critical reactions to Johnson’s metaphor were not always (easily) categorized into one of the types of resistance. Firstly, this is because they could contain several moves at once, each addressing a different aspect of Johnson’s tweet, resulting in a reply that would both contain, for instance, a propositional reaction and a personal reaction (see example (3)).

Secondly, in some cases it was unclear what the criticism was aimed at. For instance, example (8) contains the following: “Yet again we have conflict and violence referenced. Why?.” The question “Why?” here could be interpreted as an informative question, implying that the author of the tweet does not understand the use of this type of language. In that case, one could categorize the critical reaction as locutional. However, the question could also be interpreted as a challenge (see Koshik, Citation2003): it could function as a rhetorical question right after a negative evaluation (“yet again”) of referencing to conflict and violence, implying that the author disagrees with the chosen reference to violence – for instance, because of the incomparability with the domain of disease. In that last case, one would label the reaction as propositional.

What is more, we are well aware that, with respect to the focus of the resistance, more distinctions might be made within this parameter. Following Krabbe and van Laar (Citation2011), we only focused on the type and aspect of the move that is criticized in the present paper. However, the analysis showed that there seems to be a difference in specificity of resistance in a number of tweets. That is why we included an extra category of “general criticism to metaphor.”

With respect to the kind of norms that are applied or appealed to, identification of these norms is no easy endeavor either. Oftentimes, arguers only implicitly apply such rules, so clear references are hard to identify. What is more, the different norms proposed by Krabbe and van Laar (Citation2011) might overlap or depend on each other. For example, a metaphor could be resisted for its lack of effectiveness (an optimality norm) in the specific context at hand (an institutional norm).

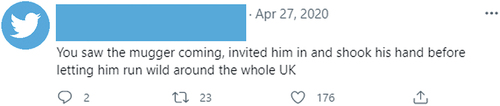

The corpus study also revealed a specific form of resistance: in 15.2% of replies Johnson’s original metaphor was re-used to criticize his speech. Example (10), for instance, adopts Johnson’s depiction of the virus as a mugger, but instead of adopting the scenario Johnson introduced, of the mugger wrestled to the floor, the tweet offers an alternative scenario which paints a negative picture of Johnson’s politics. The reply could thus be seen as resistance focused on the person which is expressed by exploiting the original metaphor (see van Poppel & Pilgram, Citationin press).

(10)

Conclusion

In this paper, we propose a typology of resistance to metaphor. We argue that metaphors can be resisted by focusing on different types of moves (single, constellation of moves and part of moves) and aspects of moves (the proposition, locution, person or situation), and we have specified what types of norms an interlocutor could appeal to in this resistance (discussion rules, optimality norms, and institutional rules).

The typology of resistance to metaphor has been illustrated by means of a corpus analysis of critical reactions on Twitter to former UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s “mugger metaphor.” The study showed that most resistance was based on norms that can function as discussion rules, while focusing on the proposition, thus questioning the way the domains were represented by Johnson and the level of similarity between the domains compared. This result indicates that, in this particular data set, the lack of aptness of the metaphor is an important trigger for resistance. However, the corpus analysis has also revealed that other types of resistance, focused on the situation, person or locution, which we distinguished theoretically and which have been hardly addressed in the literature thus far, occur as well – albeit with lower frequency.

In our view, the proposed typology of resistance to metaphor could have both theoretical and practical implications. Theoretically speaking, it can be the first step in systematically analyzing how metaphors are resisted in discourse, as it shows to be a reliable tool for analysis. Practically speaking, the typology might help in anticipating different types of resistance to metaphor when using metaphors in argumentation on the one hand, and pinpointing exactly what is so problematic about metaphors on the other hand.

Having said that, we do realize that the proposed typology still leaves room for discussion, for instance because it is tested on reactions to one specific deliberate metaphor in one context. Using Twitter has the advantage that many antagonistic reactions can be observed, which allows studying a variety of forms of resistance. Our typology is theoretically grounded, irrespective of specific metaphors, allowing general application, and was found fruitful and reliable in distinguishing the types of resistance that occurred in our corpus. However, this Twitter corpus is obviously not representative for discourse in general so other instantiations and frequencies of resistance to metaphor are expected to occur in other contexts, for instance when different source or target domains are used or more indirect and non-deliberate metaphors. Future research should therefore include a broader application of the typology on different cases of metaphor in distinct contexts.

Also, we have developed the typology based on a specific conception of resistance, namely explicit resistance in reaction to an argumentatively used metaphor, thereby disregarding other types for resistance, such as unexpressed or unconscious resistance (cf. Gibbs & Siman, Citation2021). Our corpus analysis did lay bare an additional explicit form of resistance, which involves rejection of metaphors (or even rhetoric or figurative language) in general.

Additionally, in this paper, we have only shortly mentioned some possible norms that could play a role in argumentative exchanges, such as argumentation rules, but a complete overview of such rules does not exist (resistance might, for example, also be based on stylistic or creative norms). Despite these potential difficulties, we nevertheless believe that trying to distinguish analytically between the norms appealed to might help in pinpointing what exactly triggered the resistance to metaphor.

We should also stress that we only focused on how Johnson’s “mugger metaphor” was received and we do not offer an evaluation of it. The negative reactions on Twitter, a rather antagonistic medium, might not be representative for the general reception of Johnson’s “mugger metaphor.”Footnote7 For an adequate evaluation, one thus needs to take into account the intended audience, goal and context of Johnson’s public statement – which is beyond the scope of this study.

With the proposed typology of resistance to metaphor, we hope to have offered a useful contribution to both argumentation and metaphor studies. While argumentation theorists may be generally interested in critical reactions that appeal to argumentation rules, it is crucial to acknowledge that violations of other rules may impede persuasion as well, as is illustrated by this corpus study. From the perspective of metaphor studies, the typology can be used to systematically analyze the kind of resistance that occurs when people are confronted with different kinds of argumentative use of metaphor. Last, it should also be noted that metaphor plays a role in all kinds of vital types of discourse, such as health communication or political negotiations, so people in general should be critical to problematic metaphor use and could even use our typology as a heuristic in formulating their resistance to a particular metaphor.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 Krabbe and van Laar (Citation2011, p. 206) distinguish between reactions that appeal to norms implicitly, e.g., by questioning the acceptability of an argument, and those that appeal to norms explicitly by calling out the rule that is supposedly violated.

2 If an extended metaphor is used, it could stretch over several moves from multiple discussion stages, such as starting points, arguments and standpoint. In that case, criticism regarding the used metaphor focuses on several moves. However, this is not completely in line with what Krabbe and van Laar (Citation2011) seem to envision by “combination of moves,” as they refer to complex argumentation, which is a series of moves limited to the argumentation stage and extended metaphors can also be used in standpoints and starting points.

3 According to Garssen and Kienpointner (Citation2011, p. 46), the critical questions for the argument from analogy are: (1) Is A true (false)/right/wrong in C1? (2) Are C1 and C2 similar, in the respects cited? (3) Are the important differences (dissimilarities) between C1 and C2 too overwhelming for allowing a conclusion which crosses the different domains of reality to which C1 and C2 belong, thus allowing a conclusion that C1 and C2 are analogically equivalent? And (4) Is there some other case C3 that is similar to C1 except that A′ is false (true)/to do A′ is wrong (right) in C3?

4 Unless the performance or character of the discussion party is actually the issue under discussion (Garssen, Citation2009).

5 The direct replies were included in our dataset in July 2021. Ever since, some tweets have been removed from Twitter. Additionally, it should be noted that only direct reactions have been included in the dataset; tweets reacting to reactions to the tweet by Channel 4 News or retweets of the Channel 4-tweet have not been incorporated.

6 Not all metaphors in argumentative discourse are explicit metaphorical comparisons that are part of an analogy argument (see van Poppel, Citation2020a). Some metaphors are indirectly expressed via metaphor-related words (such as “wrestled” in example (1)) which only imply a cross-domain mapping (Steen, Citation2017). Such metaphors can be part of any type of move, not just analogy argumentation. Resistance to metaphor could also address such indirect metaphors and the implied mappings between the source and target domain (cf. Wackers, Plug, & Steen, Citation2021). Such criticism resembles the critical question focusing on the connecting premise of an analogy argument, as it may point to significant differences between the domains that are connected to each other through metaphorical language use.

7 Interestingly, James Kirkup, commentator from the Spectator (2020, April 27), in fact argues that the mugger metaphor was highly appropriate for the audience the Government was trying to reach: young males who “dream of fighting off muggers with their bare hands” and not the men you find on “political Twitter.”

References

- Al-Saleem, T. (2007). Let’s find another metaphor for “The war on cancer. Oncology Times, 29(6), 9. doi:10.1097/01.COT.0000267768.81458.6c

- Brehm, J. W. (1966). A theory of psychological reactance. New York, NY: Academic Press.

- Briñol, P., Rucker, D. D., Tormala, Z. L., & Petty, R. E. (2004). Individual differences in resistance to persuasion: The role of beliefs and meta-beliefs. In E. S. Knowles & J. A. Linn (Eds.), Resistance and Persuasion (pp. 83–104). New Jersey: Psychology Press.

- Charteris-Black, J. (2013). Analysing political speeches: Rhetoric, discourse and metaphor. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Fransen, M. L., Smit, E. G., & Verlegh, P. W. J. (2015). Strategies and motives for resistance to persuasion: An integrative framework. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1201. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01201

- Garssen, B. (2009). Ad hominem in disguise: Strategic manoeuvring with direct personal attacks. Argumentation & Advocacy, 45(4), 207–213. doi:10.1080/00028533.2009.11821709

- Garssen, B., & Kienpointner, M. (2011). Figurative analogy in political argumentation. In E. T. Feteris, B. Garssen, & A. F. S. Henkemans (Eds.), Keeping in touch with pragma-dialectics: In honor of Frans H. van Eemeren (pp. 39–58). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Gibbs, R. W., & Siman, J. (2021). How we resist metaphors. Language and Cognition, 13(4), 670–692. doi:10.1017/langcog.2021.18

- Grainger, K. (2014). Having cancer is not a fight or a battle. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/society/2014/apr/25/having-cancer-not-fight-or-battle on April 25, 2023.

- Hakim, C., Kurman, J., & Eshel, Y. (2017). Stereotype threat and stereotype reactance: The effect of direct and indirect stereotype manipulations on performance of Palestinian citizens of Israel on achievement tests. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 48(5), 667–681. doi:10.1177/0022022117698040

- Hauser, D., & Scharwz, N. (2019). The war on prevention II: Battle metaphors undermine cancer treatment and prevention and do not increase vigilance. Health Communication, 35(13), 1698–1704. doi:10.1080/10410236.2019.1663465

- Hauser, D. J., & Schwarz, N. (2015). The war on prevention: Bellicose cancer metaphors hurt (some) prevention intentions. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 41(1), 66–77. doi:10.1177/0146167214557006

- Jones, L. L., & Estes, Z. (2006). Roosters, robins, and alarm clocks: Aptness and conventionality in metaphor comprehension. Journal of Memory and Language, 55(1), 18–32. doi:10.1016/j.jml.2006.02.004

- Kirkup, J. (2020, April 27). Boris is right to talk about the coronavirus as a mugger. The Spectator. Retrieved from https://www.spectator.co.uk/article/boris-is-right-to-talk-about-the-coronavirus-as-a-mugger on September 3, 2021.

- Knowles, E. S., & Linn, J. A. (2004). Resistance and persuasion. New Jersey: Psychology Press.

- Koshik, I. (2003). Wh-questions used as challenges. Discourse Studies, 5(1), 51–77. doi:10.1177/14614456030050010301

- Krabbe, E. C. W., & van Laar, J. A. (2011). The ways of criticism. Argumentation, 25(2), 199. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10503-011-9209-8

- Lakoff, G. (2002). Moral politics: How liberals and conservatives think (2nd ed.). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (2003). Metaphors we live by. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Lakoff, G., & Turner, M. (1989). More than cool reason : A field guide to poetic metaphor. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Landau, M. J., Arndt, J., & Cameron, L. D. (2018). Do metaphors in health messages work? Exploring emotional and cognitive factors. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 74, 135–149. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2017.09.006

- Miron, A. M., & Brehm, J. W. (2006). Reactance Theory - 40 Years Later. Zeitschrift Für Sozialpsychologie, 37(1), 9–18. doi:https://doi.org/10.1024/0044-3514.37.1.9

- Musolff, A. (2004). Metaphor and political discourse. Analogical reasoning in debates about Europe. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Musolff, A. (2016). Metaphor and persuasion in politics. In E. Semino & S. Demjén (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of metaphor and language (pp. 309–322). London: Routledge.

- Oswald, S., & Rihs, A. (2014). Metaphor as argument: Rhetorical and epistemic advantages of extended metaphors. Argumentation, 28(2), 133–159. doi:10.1007/s10503-013-9304-0

- Peck, T. (2020, April 27). Boris Johnson just showed that his idea of his government’s ‘success’ is as skewed as it ever was. The Independent. Retrieved from https://www.independent.co.uk/voices/boris-johnson-coronavirus-deaths-uk-success-social-distancing-a9485846.html on September 3, 2021.

- Pilgram, R., & van Poppel, L. (2021). The strategic use of metaphor in argumentation. In R. Boogaart, H. Jansen, & M. van Leeuwen(Eds.), The language of argumentation (Vol. 36, pp. 191–212). Argumentation LibrarySpringer Nature doi:10.1007/978-3-030-52907-9_10

- Reisfield, G. M., & Wilson, G. R. (2004). Use of metaphor in the discourse on cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 22(19), 40244027. doi:10.1200/JCO.2004.03.136

- Renardel de Lavalette, K. Y., Andone, C., & Steen, G. J. (2019). I did not say that the government should be plundering anybody’s savings: Resistance to metaphors expressing starting points in parliamentary debates. Journal of Language and Politics, 18(5), 718–738. doi:10.1075/jlp.18066.ren

- Schellens, P. J. (1985). Redelijke argumenten: Een onderzoek naar normen voor kritische lezers. Dordrecht: Foris.

- Semino, E. (2021). “Not soldiers but fire-fighters” – Metaphors and Covid-19. Health Communication, 36(1), 50–58. doi:10.1080/10410236.2020.1844989

- Semino, E., Demjén, Z., Demmen, J., Koller, V., Payne, S., Hardie, A., & Rayson, P. (2017). The online use of violence and journey metaphors by patients with cancer, as compared with health professionals: A mixed methods study. BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care, 7(1), 60–66. doi:10.1136/bmjspcare-2014-000785

- Shariatmadari, D. (2020, April 27). ‘Invisible mugger’: How Boris Johnson’s language hints at his thinking. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2020/apr/27/muggers-and-invisible-enemies-how-boris-johnsons-metaphors-reveals-his-thinking on September 3, 2021.

- Sopory, P., & Dillard, J. P. (2002). The persuasive effects of metaphor: A meta-analysis. Human Communication Research, 28(3), 82–419. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2958.2002.tb00813.x

- Steen, G. J. (2008). The paradox of metaphor: why we need a three-dimensional model of metaphor. Metaphor & Symbol, 23(4), 213–241. doi:10.1080/10926480802426753

- Steen, G. J. (2011). From three dimensions to five steps: the value of deliberate metaphor. Metaphorik de, 21, 83–110.

- Steen, G. J. (2017). Deliberate Metaphor Theory: Basic assumptions, main tenets, urgent issues. Intercultural Pragmatics, 14(1), 1–24. doi:10.1515/ip-2017-0001

- Steen, G., Dorst, L., Herrmann, B., Kaal, A., Krennmayr, T., & Pasma, T. (2010). A method for linguistic metaphor identification: From MIP to MIPVU. Amsterdam, Philadelphia: John Benjamins Pub. Co.

- van Eemeren, F. H., & Grootendorst, R. (1992). Argumentation, communication, and fallacies: A pragma-dialectical perspective. Hillsdale, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

- van Eemeren, F. H., & Grootendorst, R. (2004). A systematic theory of argumentation: The pragma-dialectical approach. Cambridge: Cambridge UP.

- van Poppel, L. (2018). Argumentative functions of metaphors: How can metaphors trigger resistance? In S. Oswald & D. Maillat (Eds.), Argument and Inference. Proceedings of the 2nd European Conference on Argumentation volume II, Fribourg 2017.

- van Poppel, L. (2020a). The relevance of metaphor in argumentation: Uniting pragma-dialectics and deliberate metaphor theory. Journal of pragmatics, 170, 245–252. doi:10.1016/j.pragma.2020.09.007

- van Poppel, L. (2020b). The study of metaphor in argumentation theory. Journal of Argumentation. doi:10.1007/s10503-020-09523-1

- van Poppel, L., & Pilgram, R. (in press). Exploiting metaphor in disagreement. Journal of Language Agression and Conflict.

- van Stee, S. K. (2018). Meta-analysis of the persuasive effects of metaphorical vs. literal messages. Communication Studies, 69(5), 554–566. doi:10.1080/10510974.2018.1457553

- Wackers, D. Y. M., Plug, H. J., & Steen, G. J. (2021). “For crying out loud, don’t call me a warrior”: Standpoints of resistance against violence metaphors for cancer. Journal of pragmatics, 174, 68–77. doi:10.1016/j.pragma.2020.12.021

- Wagemans, J. H. M. (2016). Analyzing metaphor in argumentative discourse. Rivista Italiana di Filosofia del Linguaggio, 10(2), 79–94.

- Walton, D. N., Reed, C., & Macagno, F. (2008). Argumentation schemes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Wegener, D., Petty, R. E., Smoak, N. D., & Fabrigar L. R. (2004). Multiple routes to resisting attitude change. In E. S. Knowles & J. A. Linn (Eds.), Resistance and Persuasion (pp. 13–38). New Jersey: Psychology Press.