ABSTRACT

Despite efforts by universities to curb the spread of COVID-19, evidence from a separate, yet surprisingly parallel, domain of research – sexual violence perpetration – suggests that many students violate policies that regulate individual behavior and prohibit non-consensual physical contact. With the theoretical similarities between sexual violence-related behaviors and COVID-19-related behaviors in mind, we conducted two studies to explore associations between students’ noncompliance with and attitudes toward COVID-19 safety regulations, their histories of harassment perpetration, and sexual violence-related attitudes. The first, an exploratory study (N = 309), revealed negative correlations between students’ compliance with and support for COVID-19 regulations and lifetime sexual harassment perpetration, hostile sexism, and rape myth acceptance, particularly among men. The negative relationship between harassment perpetration and compliance behaviors persisted, even when controlling for multiple covariates that explain variance in antisocial behaviors. The second study (N = 283) replicated this negative relationship, even when controlling for political beliefs. These results suggest that COVID-19 attitudes and behaviors may be a product of larger societal forces that underlie sexual violence perpetration.

During the summer of 2020, universities across the United States implemented several strategies for safely re-opening their institutions in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic (Cai et al., Citation2020), including the mandatory use of masks and social distancing by students. Although the implementation of these measures likely reduced transmission of COVID-19, such policies rested on an all-important assumption – that all students equally abide by and respect rules set forth by institutions that govern their behaviors toward and around others. The importance of interrogating this assumption is clear from research in the separate, yet surprisingly parallel, domain of campus sexual violence perpetration. For decades, researchers have consistently found high rates of sexual violence within universities (e.g., Muehlenhard et al., Citation2017), despite the development and adoption of sexual violence policies that mandate consent and respectful conduct. It is clear that student perpetrators of sexual violence continue to feel comfortable flouting university rules that emphasize the sexual boundaries of others and that prohibit nonconsensual sexual contact. Such a pattern raises the question – in what world would these same students suddenly respect university rules that emphasize the health-related boundaries of others and that prohibit unsafe health-related contact?

Feminist theories provide us with important frameworks for understanding the underlying similarities between students’ perpetration of sexual violence and students’ noncompliance with COVID-19 safety regulations. Feminist theories (e.g., Connell, Citation1987) have long identified how performances of masculinity – practices that communicate invulnerability, independence, or strength – operate to maintain systems of social power for White men, in particular. For decades, sexual violence perpetration has been linked to masculinity (e.g., Harway & Steel, Citation2015; De Heer et al., Citation2020), as well systems of sexism and gender inequality, via the emphasis on the dominance and power of men, at the neglect of women’s agency and well-being (Armstrong et al., Citation2018). A student’s refusal to comply with COVID-19 regulations, such as washing hands, maintaining distance, or wearing a mask, may simply be another manifestation of such power-laden beliefs; by not complying, one is demonstrating invulnerability and fearlessness to disease, often at the neglect of others’ health and well-being (caregiving, after all, is traditionally feminine). Indeed, initial research has found that men are less likely to wear masks than women (Hearne & Niño, Citation2021; Mahalik et al., Citation2022; Palmer & Peterson, Citation2020), and “completely masculine” men are three times more likely to report contracting COVID-19 than “less masculine” men (Cassino & Besen-Cassino, Citation2020).

We see additional similarities between sexual violence perpetration and COVID-19 noncompliance behaviors when we examine the unique interpersonal dynamics at play in both behaviors (Adams-Clark & Freyd, Citation2021a). In line with feminist theories regarding the allocation of and regulation of space and movement (i.e., who is allowed to take up space in public, who is able to move about freely, and who must adapt to and remain vigilant of others within a public space; e.g. Koskela, Citation1999; Valentine, Citation1989), both sexual violence perpetration and COVID-19 noncompliance behaviors involve a disregard of others’ interpersonal space and/or boundaries. When someone perpetrates sexual harassment or assault, they are violating another person’s space, comfort, and safety. When someone fails to comply with COVID-19 regulations (e.g., refusing to wear a mask within the grocery store, or failing to stay six feet away), they are similarly violating the space, comfort, and safety of others and the community; it could be argued that a flagrant disregard for COVID-19 safety protocols constitutes an act of social violence in and of itself. As such, these two violations may go hand in hand.

Guided by the broad, theoretical commonalities between sexual violence perpetration and noncompliance with COVID-19 safety regulations, we pursued two studies (one exploratory; one replication) examining their relationship with one another among college students. Given the dearth of literature linking feminist theories of sexual violence and gender inequality with COVID-19, the purpose of our first study was to determine if any associations exist between variables related to the constructs of sexual violence and COVID-19 compliance. In other words, Study 1 served as an exploratory examination of our original query – are the students who violate sexual boundaries (and hold beliefs underlying the violation of sexual boundaries) the same students who disregard COVID-19 rules? As COVID-19 infection rates and campus policies proved to be dynamic throughout the 2020–2021 academic year, we conducted Study 2 to determine the replicability and variance of the associations found in Study 1.

Because of the exploratory nature of our research question, we cast a wide net regarding our measured variables. We measured students’ supportive attitudes toward and behavioral compliance with COVID-19-related university policies (e.g., social distancing, mask-wearing). We also measured students’ self-reported lifetime sexual harassment perpetration, as well as their endorsement of hostile sexism (misogyny; Glick & Fiske, Citation2001), benevolent sexism (paternalism; Glick & Fiske, Citation2001), and rape myths (Payne et al., Citation1999). Such beliefs are highly correlated with sexual violence perpetration and thus serve as additional proxies through which to measure sexual violence (e.g., Abrams et al., Citation2003; Begany & Milburn, Citation2002). In order to examine the unique predictive utility of our sexual violence-related variables on COVID-19 compliance behaviors, we also measured several covariates that could confound or artificially inflate our hypothesized relationships. Such covariates included history of general rule-breaking behavior, general physical aggression, and general social aggression (not sexual in nature), as well as antisocial personality traits and political beliefs (Study 2 only). The inclusion of these covariates was important to control for general aggressive behaviors and isolate the relationship between sexual violence and COVID-19-related attitudes and behaviors that is consistent with our feminist theoretical framework.

Study 1

In Study 1, we had three specific hypotheses: 1) Sexual violence-related predictors, including lifetime sexual harassment perpetration, hostile sexism, benevolent sexism, and rape myth acceptance, would negatively correlate with support for and compliance with COVID-19 safety regulations; 2) In separate models, lifetime sexual harassment perpetration, endorsement of sexist beliefs, and endorsement of rape myths would uniquely and negatively predict compliance scores, even when controlling for covariates that may explain additional variance in these behaviors, including support for COVID-19 regulations, gender, history of antisocial behavior (rule-breaking, physical aggression, and social aggression), and antisocial personality characteristics; and 3) In each model, there would be a significant interaction between gender and the sexual violence predictor, such that the negative association between each sexual violence predictor and the compliance outcome would be stronger for men than women.

Study 1 method

Participants

Participants were recruited through the Human Subjects Pool housed at a large public university located in the Pacific Northwest of the United States. This pool consists of students enrolled in undergraduate courses in psychology and linguistics. Students complete research through this pool as a course requirement (but can opt out of this requirement). To protect against self-selection, participants are unaware of the topic under investigation when signing up to participate, although they are offered this information during informed consent. This sample has been previously described in the context of a different set of research questions (Adams-Clark & Freyd, Citation2021b). Data was collected during the fall quarter of the academic year (October 26 – December 4, 2020), during which most courses were held remotely.

In Study 1, 346 undergraduate students were recruited and provided their consent to participate. From that sample, 37 participants were excluded if they incorrectly answered more than one of five “attention check” questions (e.g., “please choose ‘strongly agree’ if you are paying attention”), and one participant was excluded for haphazardly “straight-lining” responses. This left 308 participants for data analysis. The final sample consisted of predominantly emerging adults (Mage = 19.39; SDage = 1.45) who were disproportionately woman-identifying (71.8%), white (75.3%), and in their first (40.6%) or second (26.6%) years of study (see, ). This is consistent with the demographics of students enrolled in the Human Subject Pool.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of samples in a) Study 1 and b) Study 2

Measures

Compliance with COVID-19 safety behaviors

Compliance with COVID-19 safety regulations was measured using an author-created measure (see Appendix A). Participants rated the frequency with which they engaged in 10 behaviors in the past seven days, such as “wearing a mask over nose and mouth,” from 1 (“Never”) to 6 (“Multiple times each day”). Items were averaged, and higher scores reflect greater compliance. Although 10 items were used to create this score, an additional item asked about COVID-19 testing. Due to the low rate of endorsement, it was removed. Cronbach’s alpha was calculated to examine reliability (α = .62). Although moderate, this statistic is within an acceptable range for exploratory studies with a modest number of items (Hinton et al., Citation2004), and items on this scale may be better understood as causal indicators, rather than traditional effect indicators (Bollen & Bauldry, Citation2011).

Support for COVID-19 safety regulations

Attitudinal support for COVID-19 safety regulations was measured using a four-item scale (Kachanoff et al., Citation2020). Participants rated their agreement with several statements regarding COVID-19 regulations (e.g., “It is essential that we strictly practice social distancing as a nation”) from 1 (“Strongly disagree”) to 7 (“Strongly agree”). Items were averaged for each participant, and higher scores reflect higher support. The scale in the current study demonstrated acceptable reliability (α = .87).

Sexual harassment perpetration

Lifetime sexual harassment perpetration was measured using the 16-item Sexual Experiences Questionnaire – Department of Defense version (SES-DOD; Stark et al., Citation2002) that has been previously adapted to include three additional items about virtual harassment (Rosenthal et al., Citation2016). Participants rated the frequency with which they engaged in 19 behaviors in their lifetime (e.g., “told sexual stories or jokes that may have been offensive to others”) from 1 (“Never”) to 5 (“Many times”). Items were averaged, and higher scores reflect higher perpetration. The scale in the current study demonstrated satisfactory reliability (α = .91).

Hostile and benevolent sexism

Hostile and benevolent sexism were measured using the the Ambivalent Sexism Inventory (Glick & Fiske, Citation1996). Participants rated 22 statements (11 for each subscale) from 1 (“Strongly disagree”) to 7 (“Strongly agree”). Items were averaged to create two scores representing hostile sexism (e.g., “Women are too easily offended”) and benevolent sexism (e.g., “Women should be cherished and protected by men”). Higher scores reflect higher sexist beliefs. Both subscales demonstrated acceptable reliability (α’s = .75-.91).

Rape myth acceptance

Rape myth acceptance was measured using the Illinois Rape Myth Acceptance Scale (IRMA; Payne et al., Citation1999). This scale consists of 45 items (e.g., “If a girl doesn’t say ‘no,’ she can’t claim rape”) that are rated from 1 (“Not at all agree”) to 7 (“Very much agree”). Items were averaged, and higher scores reflect higher rape myth acceptance. The scale in the current study demonstrated excellent reliability (α = .95).

Antisocial behavior

Lifetime antisocial behavior (used as covariate) was measured using the Antisocial Behavior Scale (ABS; Burt & Donnellan, Citation2009). It consists of 32 items, and participants rated the frequency with which they have ever engaged in behaviors that constitute rule-breaking (“broke into a store, mall, or warehouse”), social aggression (“made fun of someone behind their back”), and physical aggression (“hit others when provoked”). Response options ranged from 1 (“Never”) to 5 (“All the time”). Item scores were averaged to yield three subscale scores (rule-breaking, social aggression, and physical aggression), where higher scores indicate greater antisocial behavior. In this study, reliability was acceptable (α’s = .69-.86).

Antisocial personality

Antisocial (dark triad) personality traits (used as a covariate) were measured using an abbreviated version of the Dirty Dozen (Jonason & Webster, Citation2010) that contains three subscales (narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy). The scale consists of 12 statements, and participants rated each statement on a scale of 1 (“Strongly agree”) to 5 (“Strongly agree”). Although items load onto separate subscales, a total score can also be calculated to represent general antisocial personality; this method was used in the current study. Item scores were averaged for each participant, where higher scores indicate greater antisocial personality traits. In the current study, this scale demonstrated acceptable reliability (α = .88).

Procedure

Study procedures were approved by the Office of Research Compliance at the University of Oregon. After indicating their consent to participate on an online informed consent form, participants were presented with a series of questionnaires via an online survey hosted on Qualtrics. Participants completed these questionnaires on an electronic device in a private location. Participants were informed that they could discontinue the survey or leave items blank without penalty. After completing the survey, participated read an online debriefing form.

Data analysis

Statistical software

We used R (Version 4.0.2; R Core Team, Citation2018) and R packages psych (Version 2.0.7; Revelle, Citation2020) and tidyverse (Version 1.3.0; Wickham, Citation2017).

Missing data

Out of 49,588 individual data points collected for analysis, 79 were missing (0.16%). No individual item had a missing rate higher than 1.6%. Due to the low rate of missing data, we opted to not impute missing data. For participants who completed >80% of the items on each scale, average scores were calculated across completed items (Parent, Citation2013).

Outlier analysis

We assessed scores for outliers (defined as 1.5 x the interquartile range). We ran analyses without removing outliers to retain raw data. Although not reported, analyses were conducted using values winsorized at the 99th percentile of their respective distributions. Statistical conclusions did not differ. We examined scores for normality, using cutoffs scores of < |3| for skewness and < |10| for kurtosis. All scores met these assumptions, except harassment perpetration. A square root transformation was applied to adjust for high kurtosis. Statistical conclusions did not differ, so results reflecting raw data are presented.

Study 1 results

Descriptive and correlational results

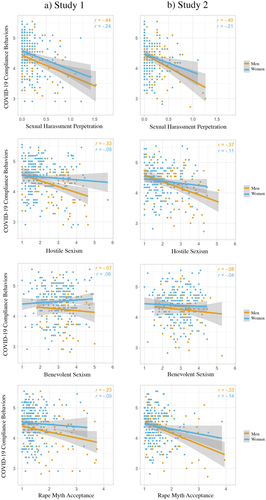

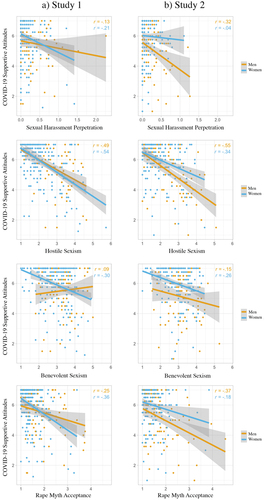

Descriptive statistics were calculated for each of the measured variables (see, ). Overall, students reported high rates of both compliance with COVID-19 safety regulations and supportive attitudes toward COVID-19 safety regulations. Women reported more frequent compliance, t(305) = 3.58, p < .001, and stronger support for safety regulations, t(305) = 2.54, p = .012, than men. Non-binary participants also reported stronger support for safety regulations, t(305) = 2.08, p = .039, but not more frequent compliance, t(305) = 0.73, p = .47, than men. Pearson’s r correlation coefficients were calculated between variables (see, ). Sexual harassment perpetration (r = −.35), hostile sexism (r = −.20), and rape myth acceptance (r = −.18) were negatively correlated with compliance, but benevolent sexism was not (r = −.02). Sexual harassment perpetration (r = −.20), hostile sexism (r = −.54), benevolent sexism (r = −.23), and rape myth acceptance (r = −.34) were negatively correlated with support. Relationships, separated by binary gender, are depicted in .

Figure 1. Scatterplots of the relationship between COVID-19 compliance behaviors and sexual harassment perpetration, hostile sexism, benevolent sexism, and rape myth acceptance in a) Study 1 (N = 302) and b) Study 2 (N = 277).

Figure 2. Scatterplots of the relationship between COVID-19 supportive attitudes and sexual harassment perpetration, hostile sexism, benevolent sexism, and rape myth acceptance in a) Study 1 (N = 302) and b) Study 2 (N = 277).

Table 2. Means, standard deviations, and correlations with 95% confidence intervals for Study 1 (S1 below the diagonal; N = 308) and Study 2 (S2; above the diagonal; N = 283)

Regression results

To test the unique association between each of our sexual violence-related predictors (sexual harassment perpetration, sexism, and rape myth acceptance) and our COVID-19 compliance outcome, we ran three separate regression models, controlling for our hypothesized covariates. Because benevolent sexism was not correlated with compliance behaviors, we did not run a regression model. We included binary gender (0 = men, 1 = women), rule-breaking history, physical aggression history, social aggression history, dark triad characteristics, and attitudinal support for COVID-19 regulations as covariates in each regression model, as these variables were all significantly correlated with the compliance outcome. Finally, we included an interaction term between binary gender and the sexual violence-related predictor of interest in each model. Because of low cell sizes, non-binary (n = 6) participants were not included in these gender-stratified regression analyses. Continuous variables were mean centered.

Regression results indicated that sexual harassment perpetration predicted unique variance in the compliance outcome (see, ), with the full model (including covariates) explaining 21% of the variance. There was no significant interaction between gender and sexual harassment perpetration. Neither hostile sexism nor rape myth acceptance alone predicted unique variance in the compliance outcome after controlling for covariates (see, ), and there were no significant interactions by gender.

Table 3. Regression models predicting compliance with COVID-19 regulations from a) Sexual harassment perpetration b) Hostile sexism and c) Rape myth acceptance (Study 1; N = 302)

Study 1 discussion

This study investigated the link between compliance with and support for COVID-19 safety regulations and multiple variables commonly studied in sexual violence literature – harassment perpetration, hostile and benevolent sexist beliefs, and rape myth acceptance. Our hypotheses were partially supported. Individually, each of these variables were correlated with one another, with the exception of benevolent sexism and COVID-19 compliance behaviors, in a college student sample. Higher sexual harassment perpetration, hostile sexism, and rape myth acceptance were related to lower compliance. Notably, variables that generally represent hostility toward women – perpetration, hostile sexism, and rape myth acceptance – were linked to COVID-19 behaviors. In contrast, benevolent sexism, which is often accompanied by fragilization of women and efforts to “protect” women from harm, was not associated with COVID-19 behaviors. Higher sexual harassment perpetration, hostile sexism, benevolent sexism, and rape myth acceptance were related to lower support for safety regulations.

In regression analyses, sexual harassment remained a significant predictor of compliance behaviors, even when covarying for factors associated with both sexual violence and COVID-19 behaviors, including gender, antisocial behaviors and personality characteristics, and attitudinal support for COVID-19 regulations. However, inconsistent with our hypotheses and our bivariate correlational results, there was no significant interaction between gender and sexual violence-related variables in these regression models. It is likely that, after controlling for our covariates, the gendered influence of sexual violence attitudes and behaviors was diluted.

Overall, these results reveal compelling similarities between sexual violence-related and COVID-19-related variables – realms of behavior that, throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, have seemingly been considered in isolation from one another. These preliminary results suggest that sexual violence perpetration and related attitudes, at least on college campuses, may tell us more information about societal dynamics than is traditionally thought and are consistent with feminist theory regarding the pervasive and systemic nature of sexual violence and boundary violations. Rather than siloed as a specialty issue, sexual violence behaviors and attitudes should be used to inform prevention and intervention efforts in multiple domains of problematic behaviors, particularly among men, who are the most common perpetrators of sexual violence.

Although this study has several important limitations, a major limitation that we initially highlight is the lack of information collected about participants’ political beliefs, which has been found to be a significant predictor of both sexual violence (Jose et al., Citation2019) and COVID-19 behaviors (Painter & Qiu, Citation2021). It is possible that the significant associations that we found in this study may be elucidated by examining the role of political ideology.

Study 2

Study 2 was designed to replicate and extend Study 1. In Study 2, we had two specific hypotheses: 1) Similar to Study 1, lifetime sexual harassment perpetration, hostile sexism, and rape myth acceptance would negatively correlate with support for and compliance with COVID-19 safety behaviors; and 2) In separate models, sexual harassment perpetration, hostile sexism, and rape myth acceptance would uniquely and negatively predict scores on the compliance outcome, even when controlling for covariates, including support for COVID-19 regulations, gender, history of antisocial behavior (rule-breaking, physical aggression, and social aggression), antisocial personality characteristics, and political beliefs.

Study 2 method

Participants

Participants in Study 2 were recruited using similar procedures as Study 1. Data were collected during the winter quarter of the academic year (February 10 – March 24, 2021), during which COVID-19 continued to spread across the campus, and academic courses remained in a virtual format. In Study 2, 324 undergraduate students provided their consent to participate. From that sample, 41 participants were excluded because they incorrectly answered more than one out of five “attention check” questions, which left 283 participants for final data analysis. Participant demographics in Study 2 were similar to Study 1 (see, ).

Measures

Study 1 measures were also used in Study 2. Participants were also asked to rate their current political beliefs on a scale ranging from 1 (“Very Conservative”) to 7 (“Very Liberal”).

Procedure

All Study 2 procedures were the same as Study 1.

Data analysis

Missing data

Out of 45,846 individual data points collected for analysis, 118 were missing (0.26%). No individual item had a missing rate higher than 1.4%. Due to the low rate of missing data, we opted to not impute, and we used the same missing data procedures as Study 1.

Outlier analysis

Like Study 1, we assessed scores for outliers. Univariate outliers were identified on each variable. Although not reported in detail in this manuscript, analyses were conducted using outlier procedures described above in Study 1, and statistical conclusions did not differ. We also examined variables for normality. All variables met these assumptions.

Study 2 results

Descriptive and correlational results

Descriptive statistics were calculated for each of the measured variables (see, ). Like Study 1, students reported high rates of compliance with and support for COVID-19 safety regulations; mean scores on these variables did not significantly differ from mean scores in Study 1. Women reported more frequent compliance with, t(280) = 2.04, p = .042, and stronger support for safety regulations, t(280) = 5.08, p < .001, than men. Non-binary participants also reported more frequent compliance with, t(280) = 2.14, p = .033, and stronger support for regulations, t(280) = 3.26, p = .001, than men. Pearson’s r correlation coefficients were calculated between measured variables (see, ). Sexual harassment perpetration (r = −.30), hostile sexism (r = −.24), and rape myth acceptance (r = −.24) were negatively correlated with compliance, but benevolent sexism was not (r = −.08). Sexual harassment perpetration (r = −.22), hostile sexism (r = −.49), benevolent sexism (r = −.26), and rape myth acceptance (r = −.33) were negatively correlated with support for regulations. Political beliefs were significantly correlated with COVID-19 variables (r = .26 for compliance; r = .61 for support).

Regression results

In Study 2, we ran the same regression models from Study 1, with the inclusion of a political beliefs covariate (see, ). Like Study 2, regression results indicated that sexual harassment perpetration uniquely predicted variance in compliance scores, with the whole model accounting for 26% of the variance. However, neither hostile sexism nor rape myth acceptance uniquely predicted variance in compliance, and political beliefs were not a significant unique predictor in any model. Like Study 2, there were no significant interactions.

Table 4. Regression models predicting compliance with COVID-19 regulations from a) Sexual harassment perpetration b) Hostile sexism and c) Rape myth acceptance (Study 2; N = 277)

Study 2 discussion

This additional study was conducted to examine the replicability of the associations found in Study 1 and to include an important additional covariate in regression models – political beliefs. Overall, the patterns of correlations in Study 2 were similar to Study 1, suggesting that both COVID-19 and sexual violence attitudes and behaviors consistently hang together to a moderate extent among college students. Although political beliefs correlated with both COVID-19 attitudes and behaviors and sexual violence attitudes and behaviors, they did not uniquely predict our compliance outcome, most likely due to their high correlation with supportive attitudes toward COVID-19 compliance behaviors. This may also be because, although liberal-identifying politicians tend to support mask wearing and compliance behaviors, there are several public accounts of safety violations that cross the political aisle (e.g., Gorman, Citation2021).

Study 2 regression results replicated Study 1. Like Study 1, sexual harassment perpetration was a unique predictor of compliance behaviors. However, sexual violence attitudes (hostile sexism and rape myth acceptance) were not significant predictors, and there were no gendered interaction effects. Given that general attitudes are not always perfect predictors of behavior (e.g., Ajzen et al., Citation2018), this result is not surprising.

Discussion

Results from exploratory Study 1 and replication Study 2 provide evidence for the interrelationship of sexual violence-related attitudes and behaviors and pandemic-related attitudes and behaviors. Importantly, both studies support the notion that sexual violence perpetration history is uniquely associated with compliance with COVID-19 safety regulations, above and beyond having supportive attitudes toward these policies and other behaviors and personality characteristics. Although a novel area of research, these results are consistent with literature linking COVID-19 behaviors and attitudes to gender and masculinity (e.g., Cassino & Besen-Cassino, Citation2020; Mahalik et al., Citation2022; Palmer & Peterson, Citation2020).

Overall, these results have several implications for both the university institution and the management of future public health crises. In particular, universities must examine how the policies used to curb harmful student behaviors in various different domains (e.g., sexual violence, bullying, discrimination, public health) may intersect and be informed by one another. Issues such as sexual violence prevention or the COVID-19 pandemic response are often treated by university institutions and society more generally as “specialized” or marginalized issues, yet, according to our data, they may share a marked number of similarities. These similarities are likely due to underlying psychological and societal factors that deserve research attention and practical intervention and that have been eloquently explicated by feminist theorists for decades.

The present studies also have several limitations that constrain our conclusions. First, these studies included only cross-sectional data, which does not allow for the interpretation of cause and effect. In addition, our studies did not explore the larger mechanisms that may underlie these initial associations, such as perceptions of entitlement, power, or privilege, which may cause some students to be more likely to engage in both sexual violence and pandemic safety violations than others. Future research may benefit from examining such constructs in a more complex model over time. Relatedly, our sample was limited to solely college-aged students located at one specific university, and the results may not generalize to other segments of the United States population. Because young adults were not believed to be at high risk for death or major complications from COVID-19 during the time of the data collection, COVID-19 attitudes and behaviors may be more influenced by students’ desire to protect others in the community than themselves. On the other hand, older adults’ COVID-19 attitudes and behaviors may be related to their perceptions of the risk to themselves and their desire to protect themselves.

Further, because of the limitations of our sample and recruitment strategy, we were also unable to investigate how the intersections of gender, race, and other identities may differentially influence not only attitudes toward and compliance with safety regulations, but also their relationship with sexual violence-related variables. Prior research suggests that understandings of both gender and race are needed to provide comprehensive picture of both COVID-19 and sexual violence. For instance, white men are the least likely group to wear masks (Hearne & Niño, Citation2021), and analogously, white college men are more likely to indicate a proclivity to rape than both Black and Latino men (Palmer et al., Citation2021). Additional research in this area is much needed.

The COVID-19 pandemic will – hopefully – come to an end, but it will very likely not be the last pandemic. Successful response to future pandemics and other public health emergencies may depend on pro-social behaviors and attitudes similar to those we have measured. We urge researchers to continue to probe the associations between sexual violence harassment, sexist attitudes, and behaviors and attitudes in other domains that put the community in danger.

Ethical Standards and Informed Consent

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation [institutional and national] and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study. No identifying information was collected.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Abrams, D., Viki, G. T., Masser, B., & Bohner, G. (2003). Perceptions of stranger and acquaintance rape: The role of benevolent and hostile sexism in victim blame and rape proclivity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(1), 111–125. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.84.1.111

- Adams-Clark, A. A., & Freyd, J. J. (2021a, November 8). What does COVID-19 transmission have in common with sexism and harassment? As it turns out, quite a bit. Stanford University Clayman Institute for Gender Research. https://gender.stanford.edu/news-publications/gender-news/what-does-covid-19-transmission-have-common-sexism-and-harassment-it

- Adams-Clark, A. A., & Freyd, J. J. (2021b). COVID-19-related institutional betrayal associated with trauma symptoms among undergraduate students. PLOS one, 16(10), e0258294. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0258294

- Ajzen, I., Fishbein, M., Lohmann, S., & Albarracín, D. (2018). The influence of attitudes on behavior. In D. Albarracín & B. Johnson (Eds.), The handbook of attitudes (pp. 197–255). Routledge.

- Armstrong, E. A., Gleckman-Krut, M., & Johnson, L. (2018). Silence, power, and inequality: An intersectional approach to sexual violence. Annual Review of Sociology, 44(1), 99–122. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-073117-041410

- Begany, J. J., & Milburn, M. A. (2002). Psychological predictors of sexual harassment:Authoritarianism, hostile sexism, and rape myths. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 3(2), 119–126. https://doi.org/10.1037/1524-9220.3.2.119

- Bollen, K. A., & Bauldry, S. (2011). Three Cs in measurement models: Causal indicators, composite indicators, and covariates. Psychological Methods, 16(3), 265–284. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024448

- Burt, S. A., & Donnellan, M. B. (2009). Development and validation of the subtypes ofAntisocial Behavior Questionnaire. Aggressive Behavior, 35(5), 376–398. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.20314

- Cai, W., Ivory, D., Smith, M., Lemonides, A., & Higgins, L. (2020, July 28). What we know about Coronavirus cases on campus. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/07/28/us/covid-19-colleges-universities.html

- Cassino, D., & Besen-Cassino, Y. (2020). Of masks and men? Gender, sex, and protective measures during COVID-19. Politics & Gender, 16(4), 1052–1062. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X20000616

- Connell, R. (1987). Gender and power. Allen and Unwin.

- de Heer, B. A., Prior, S., & Hoegh, G. (2020). Pornography, masculinity, and sexual aggression on college campuses. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 36(23–24), NP13582–NP13605. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260520906186

- Glick, P., & Fiske, S. T. (1996). The ambivalent sexism inventory: Differentiating hostile and benevolent sexism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70(3), 491–512. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.70.3.491

- Glick, P., & Fiske, S. T. (2001). An ambivalent alliance: Hostile and benevolent sexism as complementary justifications for gender inequality. American Psychologist, 56(2), 109–118. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.56.2.109

- Gorman, J. (2021, January 20). Is mask-slipping the new man-spreading? The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/20/well/mind/masks-men-manspreading.html

- Harway, M., & Steel, J. H. (2015). Studying masculinity and sexual assault across organizational culture groups: Understanding perpetrators. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 16(4), 374–378. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039694

- Hearne, B. N., & Niño, M. D. (2021). Understanding how race, ethnicity, and gender shape mask-wearing adherence during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from the COVID impact survey. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 8(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-020-00941-1

- Jonason, P. K., & Webster, G. D. (2010). The dirty dozen: A concise measure of the dark triad. Psychological Assessment, 22(2), 420–432. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019265

- Jose, R., Fowler, J. H., & Raj, A. (2019). Political differences in American reports of sexual harassment and assault. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(15–16), 7695–7721. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260519835003

- Kachanoff, F. J., Bigman, Y. E., Kapsaskis, K., & Gray, K. (2020). Measuring realistic and symbolic threats of COVID-19 and their unique impacts on well-being and adherence to public health behaviors. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 12(5), 603–616. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550620931634

- Koskela, H. (1999). “Gendered exclusions:” Women’s fear of violence and changing relations to space. Geografiska Annaler, Series B: Human Geography, 81(3), 111–124. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0435-3684.1999.00052.x

- Mahalik, J. R., Bianca, M. D., & Harris, M. P. (2022). Men’s attitudes toward mask-wearing during COVID-19: Understanding the complexities of mask-ulinity. Journal of Health Psychology, 27(5), 1187–1204. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105321990793

- Muehlenhard, C. L., Peterson, Z. D., Humphreys, T. P., & Jozkowski, K. N. (2017). Evaluating the one-in-five statistic: Women’s risk of sexual assault while in college. The Journal of Sex Research, 54(4–5), 549–576. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2017.1295014

- Painter, M., & Qiu, T. (2021). Political beliefs affect compliance with government mandates. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 185, 688–701. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2021.03.019

- Palmer, J. E., McMahon, S., & Fissel, E. (2021). Correlates of incoming male college students’ proclivity to perpetrate sexual assault. Violence Against Women, 27(3–4), 507–528. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801220905663

- Palmer, C. L., & Peterson, R. D. (2020). Toxic Mask-ulinity: The link between masculine toughness and affective reactions to mask wearing in the COVID-19 era. Politics & Gender, 16(4), 1044–1051. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X20000422

- Parent, M. C. (2013). Handling item-level missing data: Simpler is just as good. The Counseling Psychologist, 41(4), 568–600. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000012445176

- Payne, D. L., Lonsway, K. A., & Fitzgerald, L. F. (1999). Rape myth acceptance: Exploration of its structure and its measurement using the Illinois rape myth acceptance scale. Journal of Research in Personality, 33(1), 27–68. https://doi.org/10.1006/jrpe.1998.2238

- Perry Hinton, D., Hinton, P. R., McMurray, I., & Brownlow, C. (2004). SPSS explained. Routledge.

- R Core Team. 2018. R: A language and environment for statistical computing [Internet]. Available from https://www.R-project.org/

- Revelle, W. (2020). psych: Procedures for psychological, psychometric, and personality research[Internet]. Available from https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=psych

- Rosenthal, M. N., Smidt, A. M., & Freyd, J. J. (2016). Still second class: Sexual harassment of graduate students. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 40(3), 364–377. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684316644838

- Stark, S., Chernyshenko, O. S., Lancaster, A. R., Drasgow, F., & Fitzgerald, L. F. (2002). Toward standardized measurement of sexual harassment: Shortening the SEQ-DoD using item response theory. Military Psychology, 14(1), 49–72. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327876MP1401_03

- Valentine, G. (1989). The geography of women’s fear. Area, 21(4), 385–395. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20000063

- Wickham, H. (2017). tidyverse: Easily install and load the “tidyverse” [Internet]. Available from: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=tidyverse

Appendix A

COVID-19 Compliance Behavior Measure

In the past 7 days, how frequently have you … .

Gone inside a store to shop for non-essential items?^

Been within 6 feet of someone (who you’re not living with) for more than 15 minutes?^

Worn a mask over your nose and mouth when leaving your house, apartment, or dorm room?

Disinfected frequently used items and/or shared living spaces?

Completed a COVID-19 symptom self-check?

Attended a campus party or social event with more than 10 people?^

Ate or drank inside a restaurant or bar?^

Washed your hands thoroughly for 20+ seconds, especially after touching any frequently used item or surface?

Been tested for COVID-19?*

Been around other people outside your house, apartment, or dorm room without a mask on?^

Skipped disinfecting frequently used items and/or shared living spaces?^

*indicates removed prior to analyses, as it had a very small rate of endorsement

^indicates reverse scored item

Options items include: Never, 1 time in the last week, 2–3 times in the last week, 4–5 times in the last week, once each day, multiple times each day.