ABSTRACT

Bullying is a frequent, yet sometimes dismissed dynamic in school-aged youth, despite all the literature around its prevalence and detrimental effects. Around the world, prevalence estimates have demonstrated wide variability. In Colombia, between 22% and 49.9% of adolescents have experienced bullying. Much research on school bullying has focused on perpetrators and those victimized; less is known about those who witness it. The main objective of this cross-sectional study of 1224 Colombian public high school students was to determine if there is an association between the different types of involvement (victims, aggressors, witnesses) in bullying and the presence of symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). We measured individual sociodemographic factors, types of involvement in bullying, the presence of PTSD symptoms, and levels of family dysfunction. We found that verbal abuse was the most frequent behavior reported. Also, a high proportion of PTSD symptoms among victims, witnesses, and aggressors were identified. In the logistic regression analysis, presence of PTSD symptoms was associated with subjects identified as social victims (OR = 2.067; CI = 1.381– 3.095), verbal victims (OR = 2.779; CI = 1.599–4.828), victims by coercion (OR = 4.038; CI = 1.710–9.532), social aggressors (OR = 1.974; CI = 1.355–2.919), and in those with severe family dysfunction (OR = 3.372; CI = 1.744–6.520). Additional research is needed in the Colombian population to identify and explore appropriate options for prevention and intervention in those most vulnerable to bullying.

Bullying is a behavior intended to inflict injury or discomfort upon another individual, carried out repeatedly and over time, and with a certain imbalance of power or strength (Olweus, Citation2013), which has always been present in the relationships between schoolchildren (Andonegui & Líbano, Citation2005; Olweus, Citation1994). The earliest publications became available in the 1970s under the perspective of the study of aggression in adolescents. However, in the last two decades, investigations have increased, and this phenomenon has seen greater dissemination as a public health problem (Álvarez et al., Citation2006; Bonell et al., Citation2015; Gladden et al., Citation2014; Hamburger et al., Citation2011; Olweus, Citation1994, Citation2013). Worldwide, studies of bullying prevalence show results ranging from less than 10% to more than 70%, depending on the measurement method, the instrument used, the type of involvement, and the context of the population studied (Forero et al., Citation1999; Kaltiala-Heino et al., Citation1999; Malta, Porto, et al., Citation2014; Nansel et al., Citation2001). In Colombia, a prevalence of 22% to 49.9% has been reported (Cassiani-Miranda et al., Citation2014; Cepeda-Cuervo et al., Citation2008; Chaux et al., Citation2009; Cuevas Jaramillo et al., Citation2009; Paredes et al., Citation2008).

Colombian law has defined bullying as intentional and repetitive aggressive behaviors between peers due to an imbalance of power (such as differences in social status, age, or height), which results in an aggressor and victim dynamic (Congreso de Colombia, Citation2013). It can be expressed in physical aggression, such as hitting, pushing, stealing, and using weapons to attack; verbal intimidation, such as threats, insults, and use of pejorative nicknames; and relational (social) bullying, with the spread of comments and lies that can affect the victim’s relationship with their peers, exclusionary behaviors, indifference, and extortion (De Oliveira Pimentel et al., Citation2020). In a cross-sectional study of 2,000 schoolchildren (5th through 10th grade) from Colombia, Cuevas Jaramillo et al. (Citation2009) identified prevalence rates of various types of bullying including verbal intimidation (90.1%), social intimidation (86.2%,) physical intimidation (71.3%), and intimidation by coercion (29.6%).

Bullying is linked to negative psychological consequences not only for those who are victims, but also for those who exert aggression and those who witness it and can lead to psychiatric disorders for all three groups (Highland-Angelucci et al., Citation2015; Montañez-García & Ascensio-Martínez, Citation2015; Takizawa et al., Citation2014; Wolke & Lereya, Citation2015). Follow-up studies have found that perpetrators of bullying are at greater risk for antisocial and criminal behaviors in adulthood (Bender & Lösel, Citation2011; Lugones Botell & Ramírez Bermúdez, Citation2017; Salas Viloria & Combita Niño, Citation2017; Ttofi et al., Citation2011), increased risk of suicidal ideation and suicidal/self-harm behavior (Barker et al., Citation2008), and higher risk of illicit drug use in later life (Niemelä et al., Citation2011). Those aggressive toward others also were more likely to have trouble keeping a job and honoring financial obligations and were at higher risk of being unemployed and receiving social assistance in adulthood (Sigurdson et al., Citation2014).

A 50-year prospective cohort found that the impact of being a victim of bullying in childhood resulted in higher rates of depression, anxiety disorders, and suicidality compared to non-victimized peers. It was also associated with a lack of social relationships, economic hardship, and poor perceived quality of life at age 50 (Takizawa et al., Citation2014). Another cohort study found that victims of bullying were at increased risk of poor physical and mental health and reduced adaptation to adult roles including forming lasting relationships, integrating into the work force, and being economically independent, even after controlling for family hardship and childhood psychiatric disorders (Wolke & Lereya, Citation2015).

Human responses to experiencing or being exposed to traumatic events, such as family and social violence, rapes and assaults, disasters, wars, accidents, and predatory violence, force people to be confronted with horror and serious threat in a way that alters their capacity to cope. Traumatized individuals frequently develop posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Initially described as resulting from a one-time severe traumatic incident, PTSD has now been shown to be triggered by chronic multiple traumas as well (van der Kolk, Citation2000). According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders DSM-5, being bullied qualifies as a criterion of exposure when there is a credible threat of serious harm or sexual violence (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013).

A study of primary school children in New York found that peer victimization accounted for 14.1% of PTSD symptom severity among boys and 10.1% among girls (Litman et al., Citation2015). Another study in German children and adolescents found that scores for symptoms of PTSD were significantly higher in bullied versus non-bullied students and that there were no significant differences in students who experienced severe bullying when compared to patients from an outpatient clinic for PTSD (Ossa et al., Citation2019). A retrospective study among Greek university students investigated the association between bullying victimization experiences at school and PTSD and showed that duration and frequency of victimization by school bullying were found to have a significant effect on PTSD severity (Andreou et al., Citation2020).

In a study of the role of families in promoting resilience in children exposed to bullying, it was found that warm family relationships and positive home environments help to buffer children from the negative outcomes associated with bullying victimization (Bowes et al., Citation2010). On the other hand, scientific evidence has indicated a link between family violence and aggression in school. Children and adolescents who have experienced parental aggression tend to view violence as acceptable and are more likely to engage in aggressive behavior, including bullying and school violence. Cross-sectional research in different countries, including Brazil (Malta, Do Prado, et al., Citation2014), Spain (Gómez-Ortiz et al., Citation2016), Sweden (Lucas et al., Citation2016), Taiwan (Chen et al., Citation2021), and China (Liu et al., Citation2022), suggests a link between parental corporal punishment, school violence, and bullying among adolescents. This link was also confirmed by a longitudinal study of adolescents in Taiwan (Chen et al., Citation2023).

In Colombia, a large cross-sectional study carried out with 12,302 adolescents in 12 public schools revealed a relationship between severe family dysfunction and violent behavior (González-Quiñones & De la Hoz-Restrepo, Citation2011). Additionally, a Colombian case-control study that investigated the risk factors associated with school bullying found that schoolchildren living in a family with verbal and physical violence were more vulnerable to bullying. The risk factors associated were family dysfunction, verbal aggression at home, physically punishing parents, and physically aggressive neighbors (Hernández & Gutiérrez, Citation2013).

While most of the studies on bullying focus on victims and aggressors, much less is known about those who witness incidents of bullying. Research on the association between bullying and PTSD symptoms focuses on victims, but not on other types of involvement, such as those who witness it. Therefore, the primary objective of this study was to determine whether there is a differential association between types of bullying involvement (aggressors, victims, witnesses) and the presence of PTSD symptoms. Secondarily, the study aimed to explore the influence of family dysfunction and other factors among adolescents from two public high schools in Colombia.

Materials and method

Design

This is a cross-sectional study carried out with students from two public high schools located in a municipality near the city of Bogotá, Colombia. Data collection was performed in each institution during school days in October 2015.

Participants

Subjects were identified through the lists of enrolled students for the academic year, provided to the investigators by the educational institutions. Inclusion criteria were students between 11 and 18 years old, enrolled in 7th through 11th grades. Since the study utilized a self-report measure, subjects with intellectual disability or physical disability (identified by their teachers) that prevented them from completing the questionnaire were not included. Written informed assent and written parental consent were obtained before subjects were enrolled in the study. Because school directors requested that all students be included in completing the survey, no sample size was calculated; of the approximately 1400 students enrolled in 7th to 11th grade in both schools at the time of the study, 1224 students were ultimately included. Losses were due to the absence of those students on the day of study implementation or the inability to obtain informed consent for study participation. Of the 1224 surveys reviewed, 5 were excluded from the analysis due to the lack of information on bullying measures, for a total of 1219 surveys analyzed.

Evaluation instruments

A single questionnaire was designed to collect data regarding sociodemographic variables, the presence of bullying, symptoms of PTSD, and perception of family dysfunction.

The Cuevas School Bullying Questionnaire, (Cuestionario de Intimidación Escolar-Reducido;CIE-R) was used to estimate the prevalence of bullying (Cuevas Jaramillo et al., Citation2009). This is a self-administered survey consisting of 105 questions to measure bullying in students between 8 and 18 years old. This instrument identifies three types of involvement: aggressors, victims, and witnesses. It was developed based on the previous CIE-A and CIE-B questionnaires (Cuevas Jaramillo et al., Citation2009), and adapted from other instruments that assess the magnitude and characteristics of school bullying (Olweus, Citation1994; Piñuel & Oñate, Citation2006). The CIE-R was validated in the Colombian population and has been utilized in other national studies (Moratto Vásquez et al., Citation2012; Springer et al., Citation2016).

Family dysfunction was assessed using the Family APGAR Scale (Smilkstein et al., Citation1982). This self-administered instrument, which measures the adaptability, partnership, growth, affection, and resolve (APGAR) of a family, identifies family functioning levels where dysfunction may be mild, moderate, or severe. The questionnaire contains five Likert response questions to assess the perception of family functioning (Smilkstein, Citation1978; Smilkstein et al., Citation1982). It was validated for the Colombian population demonstrating good internal consistency (α = .793) (Bellón Saameño et al., Citation1996; Forero-Ariza et al., Citation2006; Hernández & Gutiérrez, Citation2013).

Procedures

A pilot test was carried out on 30 subjects from one of the educational institutions one month before the application to the whole sample. The purpose was to evaluate the completion time of the questionnaire and identify possible difficulties in administration. Based on this information, logistical adjustments were made before applying to the study sample. One month after this pilot test, in a single-day session for each educational institution. Responses were provided on paper and later digitized.

As a control measure for response bias, students completed their surveys anonymously to minimize potential bias in their answers. To address measurement biases, self-response, and validated instruments were used, with prior training for the personnel who supervised the exercise. The survey was applied synchronously to all subjects to reduce comments between them about the questions, and thus avoid a magnification of the problem.

Statistical analysis

The main variable evaluated was bullying and it was measured using the CIE-R instrument. To determine the presence or absence of bullying, the variable was recategorized according to the procedure recommended by the authors of the questionnaire (Cuevas Jaramillo et al., Citation2009).

The numerical scores of the Family APGAR Scale were classified according to the established cutoff points of dysfunction: severe (0–9 points), moderate (10–13 points), mild (14–17 points), and functional (≥18 points). This variable was also recategorized to determine the presence (0–17 points) or absence (≥18 points) of family dysfunction.

The statistical analysis was divided into a descriptive phase and an analytical phase. Statistical Software RStudio (v4.0.3; 2020) was used to perform the analyses. In the descriptive phase, frequencies and proportions were determined for the categorical variables. In continuous variables, means and medians were used as central tendency measures, and standard deviations and interquartile ranges were used as dispersion measures according to the distribution of the data. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to determine the distribution of the data.

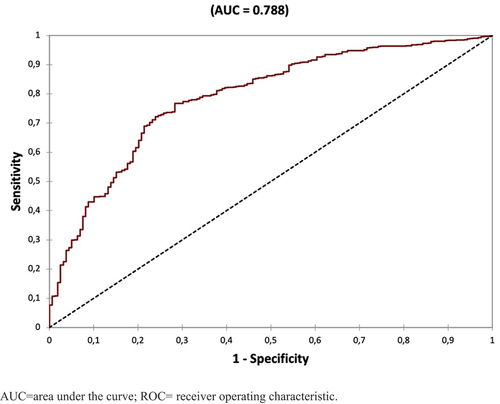

A simple logistic regression was performed to determine the association between different types of involvement in bullying and the presence of PTSD symptoms. The goodness of fit statistics and hypothesis testing (Wald’s test) were performed with statistical significance established at p < .0001. In addition, we calculated the odds ratio (OR) between variables included in the regression model. Sensitivity and specificity analyses, contingency tables, and a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve were performed based on the variables included. Correlation coefficients between categorical variables were calculated using Chi-square tests, and statistical tests were used to assess the dependence between them. Finally, a multiple correspondence analysis was performed to group variables by dimensions.

Ethical considerations

This study was conducted in accordance with national and international regulations regarding the protection of human participants in biomedical research (Resolution 8430 of the Ministry of Health) (Ministerio de Salud, Citation1993) and the Declaration of Helsinki (World Medical Association, Citation2013). The research protocol and informed consent were approved by an independent research ethics committee (Acta 083, C.E.I. Campo Abierto, Bogotá D.C., Colombia). Considering that the questionnaires were applied to subjects under 18 years old, a signed assent by the student and a signed informed consent by the student’s parents were required and obtained.

Results

A total of 1,219 subjects were analyzed. The mean age of the subjects was 14.46 years. The sample was similarly distributed between those identifying as male and female, and most subjects denied any diagnosed physical or mental health comorbidities. Substance use was similarly distributed between those who consumed and those who did not. Among those who reported consuming any substance, the most consumed substances were cigarettes and alcohol. More than 70% of subjects reported some level of family dysfunction. summarizes the main sociodemographic characteristics.

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics.

The overall prevalence of bullying was 43.9%. All three groups (victims, aggressors, and witnesses) reported verbal offenses as the most frequent type of bullying, followed by physical aggression. The proportion of PTSD symptoms was high in both victims and witnesses, and some subjects reported having more than one type of involvement in bullying ().

Table 2. Prevalence of bullying (per role) and presence of PTSD symptoms.

For those who were victims, verbal offenses were the most frequently reported type of bullying, followed by physical aggression and social bullying. In this group, the presence of PTSD symptoms was higher for verbal offense victims followed by those who experienced physical aggression ().

Among the aggressors, most subjects reported perpetrating verbal offenses, followed by physical aggression, and social bullying. PTSD symptoms were reported by those who participated in verbal offenses and physical aggression, although the overall presence of PTSD symptoms was lower in aggressors than that of the other groups ().

Within the witnesses group, most subjects reported observing verbal offenses, followed by physical aggression, and social bullying. PTSD symptoms were reported to be highest by those who witnessed all three types of bullying (verbal, physical, and social) ().

The logistic regression model showed that the variables that best describe the presence of symptoms of PTSD are age (categorized), sex, living with mother only, alcohol consumption, family dysfunction, verbal abuse victim, social bullying victim, victim by coercion, and social bullying aggressor (). It had a Nagelkerke R2 goodness of fit of .223, which indicated that the variables included explained 22.3% of the presence of PTSD symptoms.

Table 3. Logistic regression analysis of PTSD symptoms.

It was found that in subjects with severe family dysfunction, the presence of PTSD symptoms was 3.372 times greater compared with those without family dysfunction. Likewise, the presence of PTSD symptoms in social and verbal abuse victims was 2.067 and 2.779 times greater, respectively, as compared to those who did not report social or verbal victimization. In victims by coercion, the presence of PTSD symptoms was 4.038 times greater than in those who did not experience it. Finally, in social aggressors, the presence of PTSD symptoms was 1.974 times greater than that of subjects who did not use this type of bullying (). The model showed a 78% probability of accurately identifying symptoms of PTSD, with a sensitivity of 98.2% and a specificity of 10.69% ().

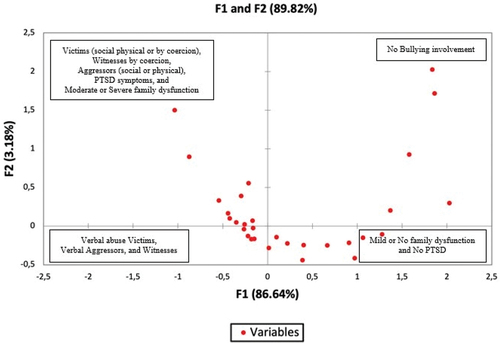

Using a multiple correspondence analysis for the categorical variables, a model that grouped the records into 4 dimensions (F1 to F4) was obtained. This model explained 90,611% of the total variance of the records included in the database. The upper right quadrant displays the subjects who did not have any kind of involvement in bullying (). The lower right quadrant shows those subjects who reported mild or no family dysfunction, and those who did not express the presence of PTSD symptoms (). The upper left quadrant displays those who reported the following: moderate or severe family dysfunction, being victims (social, physical, or by coercion), witnesses of coercion, aggressors (social or physical), and the presence of PTSD symptoms (). Finally, the lower left quadrant shows verbal abuse victims, verbal aggressors, and witnesses (physical, social, or verbal) ().

Discussion

We examined adolescent students from two public high schools in Colombia with different types of involvement in bullying, including those who were aggressors, victims, and witnesses, and the association between them and the presence of PTSD symptoms. While other studies have examined the association between post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adolescents and school bullying, to our knowledge, this is the first study to seek links between symptoms of PTSD and different types of involvement in bullying (aggressors, victims, witnesses).

In our study, the most frequent type of bullying reported by aggressors, victims, and witnesses of bullying was verbal aggression, which is consistent with the findings of Cuevas Jaramillo et al. (Citation2009). In a similar Colombian population, they similarly identified verbal aggression as the most frequent type of bullying. Likewise, various other studies have shown that verbal harassment (insults, threats, intimidation, and discrediting) is a more frequent type of bullying than physical aggression (Alavi et al., Citation2017; Bandeira & Hutz, Citation2012; Garbin et al., Citation2016; Vieira et al., Citation2016).

Based on our results, verbal harassment was found to be more frequent than physical aggression as a form of bullying. While being victimized and being the aggressor were correlated with symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress, witnesses of bullying had increased symptoms of depression, anxiety, and PTSD. Family dysfunction was found to be frequent, and it is statistically associated with bullying. Additionally, we found that how adolescents are involved with bullying is not necessarily discrete, meaning that some victims and witnesses of bullying endorsed similar characteristics of the aggressors. This finding corroborates what was found in the investigation by Bandeira and Hutz (Citation2012), where 54.7% of the victims reported identifying with the aggressors. Our study demonstrated that both being a victim and an aggressor were similarly associated with symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress. According to Klomek et al. (Citation2013), bullying is one of the most important risk factors for future psychiatric problems in the context of high school education and is associated with depression and suicide. In the research by Leader et al. (Citation2018), it was found that there is a significant association between victimization by bullying and psychiatric hospital admissions. These findings are of great importance, as they indicate the need to prevent bullying due to its consequences for those involved (De Oliveira Pimentel et al., Citation2020).

Most of the published studies have focused on the emotional consequences of bullying in the victims, some in the aggressors, and others on the victim-aggressor dynamic (Álvarez et al., Citation2006; Gladden et al., Citation2014; Hamburger et al., Citation2011; Olweus, Citation2013; Twemlow et al., Citation2006). In our study, special attention was paid to all types of involvement: aggressors, victims, and witnesses. Contrary to our expectations, we found greater symptoms of depression, anxiety, and PTSD in those who were not directly receiving nor perpetrating aggression (witnesses). This phenomenon could be explained by the impact of these affective symptoms on social functioning, leading to dynamics of school detachment, rather than a consequence of bullying itself. It has been reported that witnesses are crucial to bullying dynamics since their passive observational behavior stimulates the aggressor and perpetuates the dynamic (Rivers et al., Citation2009; Twemlow et al., Citation2006). However, this is a hypothesis that should be further investigated.

Research on bullying and victimization has described several individual, family, and school parameters that act as risk factors for psychosocial and psychopathological issues. The study by Mynard et al. (Citation2000) revealed that 37% of bullying victims reported significant PTSD symptoms, which was consistent with the study of Ossa et al. (Citation2019) that found no differences between students with severe bullying and PTSD outpatients and confirmed that bullying at school is highly associated with symptoms of PTSD. According to the findings of Stapinski et al. (Citation2015), being a victim of bullying is significantly related to an increase in depressive and anxiety symptoms. Our results are consistent with these findings since being a social victim, a verbal victim, or a victim by coercion showed significant statistical association with endorsed PTSD symptoms. In the study conducted by Forlim et al. (Citation2014), depressive symptoms were found in both victims and aggressors. Similarly, in our study we also found a statistically significant association between being a social aggressor and the endorsement of PTSD symptoms. We also found high rates of PTSD symptoms in witnesses with similar frequencies reported by victims. To our knowledge, these findings have not been reported elsewhere since most studies on PTSD and bullying focus on victims’ experiences (Yang et al., Citation2023).

Although it was not the main objective of the study, the proportion of the sample that reported family dysfunction is striking; almost 80% endorsed mild, moderate, or severe family dysfunction. We found a statistically significant association between family dysfunction and bullying, which is consistent with previous studies (Briceño & García, Citation2017; Cassiani-Miranda et al., Citation2014; Hernández & Gutiérrez, Citation2013). Due to the cross-sectional design of this study, further research using prospective methods is needed to establish causality.

Our results suggest that adolescents who are victims of verbal, social, and coercive bullying, as well as those who socially bully may be more susceptible to PTSD symptoms. Although we found high frequencies of PTSD symptoms in witnesses similar to those of victims, no association was found between the reporting of these symptoms and being a witness of bullying. Secondarily, we explored the influence of additional factors on PTSD symptoms, finding only an association with family dysfunction. As mentioned before, an association between school bullying and family dysfunction has been demonstrated previously, but not specifically with PTSD symptoms in adolescents and different types of bullying.

In this study, there are limitations that may have impacted the results of our analyses that must be considered. As with other cross-sectional studies, these outcomes should be regarded as hypotheses and subject to further investigation with prospective observational studies. Also, given the sample consisted of adolescents from public schools the results may not be generalizable to the full adolescent population in Colombia due to their specific sociodemographic characteristics. Finally, another limitation of this study is the use of self-report measures for symptom identification. It is impossible to know if any of the self-reported symptoms of PTSD represent formal diagnoses, which could provide more declarative information about the variables being studied.

Regardless, this study provides further insight into the potential negative outcomes to adolescents involved in different types of bullying, which can assist educational institutions and inform public policy around designing more specific, targeted interventions to prevent and mitigate the impact of school bullying. Studies on the association between emotional symptoms, such as those related to PTSD, and bullying show the importance of prevention and intervention efforts at the school level as well as in the home for victims, aggressors, and witnesses. Evidence strongly suggests that bullying should be addressed through such initiatives due to the negative emotional and behavioral impact it has on the lives of adolescents (De Oliveira Pimentel et al., Citation2020).

Ethical standards and informed consent

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation research (Resolution 8430 of the Colombian Ministry of Health) (Ministerio de Salud, Citation1993) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Municipality, the Secretary of Health, and the Secretary of Education of Mosquera, Colombia for their support in collecting information and facilitating access to the educational institutions. We remember the impetus and appreciate the encouragement of Professor Ember Estefenn (RIP). We also thank ODDS Epidemiology (statistical and epidemiological consulting services) and Julián Barrera (writing and proofreading of the manuscript).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alavi, N., Reshetukha, T., Prost, E., Antoniak, K., Patel, C., Sajid, S., & Groll, D. (2017). Relationship between bullying and suicidal behaviour in youth presenting to the emergency department. Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry = Journal de l’Academie Canadienne de Psychiatrie de l’enfant Et de l’adolescent, 26(2), 70–77.

- Álvarez, L., Álvarez, D., González-Castro, P., Núñez, J. C., & González-Pienda, J. A. (2006). Evaluación de los comportamientos violentos en los centros educativos [Evaluation of violent behaviors in secondary school]. Psicothema, 18(4), 686–695. http://www.psicothema.com/pdf/3295.pdf

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Cautionary statement for forensic use of DSM-5. In Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596.cautionarystatement

- Andonegui, M. G., & Líbano, R. U. (2005). Maltrato entre iguales (Bullying)en la escuela. ¿Cuál es el papel de los pediatras de Atención Primaria? [peer aggression (Bullying) at school. What is the role of Primary Care pediatricians?]. Pediatría Atención Primaria, VII(25), 165–166. http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=366638654015

- Andreou, E., Tsermentseli, S., Anastasiou, O., & Kouklari, E. C. (2020). Retrospective accounts of bullying victimization at school: Associations with post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms and post-traumatic growth among university students. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 14(1), 9–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/S40653-020-00302-4

- Bandeira, C. D. M., & Hutz, C. S. (2012). Bullying: prevalência, implicações e diferenças entre os gêneros [Bullying: Prevalence, implications and gender differences]. Psicologia Escolar e Educacional, 16(1), 35–44. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1413-85572012000100004

- Barker, E. D., Arseneault, L., Brendgen, M., Fontaine, N., & Maughan, B. (2008). Joint development of bullying and victimization in adolescence: Relations to delinquency and self-harm. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 47(9), 1030–1038. https://doi.org/10.1097/CHI.OBO13E31817EEC98

- Bellón Saameño, J. A., Delgado Sánchez, A., Luna Del Castillo, J. D., & Lardelli Claret, P. (1996). Validez y fiabilidad del cuestionario de función familiar Apgar-familiar [Validity and reliability of the Apgar-family questionnaire on family function]. Atención Primaria, 18(6), 289–296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aprim.2015.02.015

- Bender, D., & Lösel, F. (2011). Bullying at school as a predictor of delinquency, violence and other anti-social behaviour in adulthood. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, 21(2), 99–106. https://doi.org/10.1002/CBM.799

- Bonell, C., Fletcher, A., Fitzgerald-Yau, N., Hale, D., Allen, E., Elbourne, D., Jones, R., Bond, L., Wiggins, M., Miners, A., Legood, R., Scott, S., Christie, D., & Viner, R. (2015). Initiating change locally in bullying and aggression through the school environment (INCLUSIVE): A pilot randomised controlled trial. Health Technology Assessment, 19(53), 1–110. https://doi.org/10.3310/hta19530

- Bowes, L., Maughan, B., Caspi, A., Moffitt, T. E., & Arseneault, L. (2010). Families promote emotional and behavioural resilience to bullying: Evidence of an environmental effect. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 51(7), 809–817. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1469-7610.2010.02216.X

- Briceño, A., & García, M. (2017). Relación entre disfunción familiar y conductas de agresión entre pares: Colegio Municipal Nueve de Octubre [Relationship between family dysfunction and aggressive behavior among peers].

- Cassiani-Miranda, C. A., Gómez-Alhach, J., Cubides-Munévar, A. M., & Hernández-Carrillo, M. (2014). Bullying and its related factors amongst high school students from a school in Cali, Colombia. Revista de Salud Pública, 16(1), 14–26. https://doi.org/10.15446/RSAP.V16N1.43490

- Cepeda-Cuervo, E., Pacheco-Durán, P. N., García-Barco, L., & Piraquive-Peña, C. J. (2008). Acoso Escolar a Estudiantes de Educación Básica y Media [Bullying amongst students attending state basic and middle schools]. Revista de Salud Pública (Bogotá, Colombia), 10(4), 517–528. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0124-00642008000400002

- Chaux, E., Molano, A., & Podlesky, P. (2009). Socio-economic, socio-political and socio-emotional variables explaining school bullying: A country-wide multilevel analysis. Aggressive Behavior, 35(6), 520–529. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.20320

- Chen, J. K., Lin, L., Hong, J. S., & Wang, L. C. (2023). Temporal association of parental corporal punishment with violence in school and cyberbullying among adolescents. Child Abuse & Neglect, 143, 106251. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CHIABU.2023.106251

- Chen, J. K., Pan, Z., & Wang, L. C. (2021). Parental beliefs and actual use of Corporal punishment, school violence and bullying, and depression in early adolescence. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(12), 6270. https://doi.org/10.3390/IJERPH18126270

- Congreso de Colombia. (2013, March 15). Ley 1620 de 2013, Sistema Nacional de Convivencia Escolar y Formación para el Ejercicio de los Derechos Humanos, la Educación para la Sexualidad y la Prevención y Mitigación de la Violencia Escolar [National System of School Coexistence and Training for the Exercise of Human Rights, Education for Sexuality and the Prevention and Mitigation of School Violence] (1630 de 2013). Ministerio de Educación Nacional.

- Cuevas Jaramillo, M., Hoyos Hernández, P., & Ortiz Gómez, Y. (2009). Prevalencia de intimidación en dos instituciones educativas del departamento del valle del Cauca, 2009 [prevalence of bullying in two educational institutions of the department of valle del Cauca, 2009]. Pensamiento Psicológico, 6(13), 153–172.

- De Oliveira Pimentel, F., Della Méa, C. P., & Dapieve Patias, N. (2020). Víctimas de bullying, síntomas depresivos, ansiedad, estrés e ideación suicida en adolescentes [Victims of bullying, depressive symptoms, anxiety, stress and suicidal ideation in adolescents]. Acta Colombiana de Psicología, 23(2), 205–240. https://doi.org/10.14718/ACP.2020.23.2.9

- Forero-Ariza, L. M., Avendaño Durán, M. C., Duarte Cubillos, Z. J., & Campo-Arias, A. (2006). Consistencia interna y análisis de factores de la escala APGAR para evaluar el funcionamiento familiar en estudiantes de básica secundaria [Internal consistency and factor analysis of the APGAR scale to evaluate family functioning in high school students]. Revista Colombiana de Psiquiatría, 35(1), 23–29. http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0034-74502006000100003&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=es

- Forero, R., McLellan, L., Rissel, C., & Bauman, A. (1999). Bullying behaviour and psychosocial health among school students in New South Wales, Australia: Cross sectional survey. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed), 319(7206), 344–348. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.319.7206.344

- Forlim, B. G., Stelko-Pereira, A. C., & Williams, L. C. D. A. (2014). Relação entre bullying e sintomas depressivos em estudantes do ensino fundamental [Associations between bullying and depressive symptoms in elementary students]. Estudos de Psicologia (Campinas), 31(3), 367–375. https://doi.org/10.1590/0103-166x2014000300005

- Garbin, C. A. S., Gatto, R. C. J., & Garbin, A. J. Í. (2016). Prevalência de bullying em uma amostra representativa de adolescentes [Bullying prevalence in a representative sample of Brazilian adolescents]. Archives of Health Investigation, 5(5), 256–261. https://doi.org/10.21270/archi.v5i5.1701

- Gladden, R. M., Vivolo-Kantor, A. M., Hamburger, M. E., & Lumpkin, C. D. (2014). Bullying surveillance among youths: Uniform definitions for public health and recommended data elements, version 1.0. In Centers for disease control and prevention atlanta. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/bullying-definitions-final-a.pdf

- Gómez-Ortiz, O., Romera, E. M., & Ortega-Ruiz, R. (2016). Parenting styles and bullying. The mediating role of parental psychological aggression and physical punishment. Child Abuse & Neglect, 51, 132–143. 10.1016/J.CHIABU.2015.10.025

- González-Quiñones, J. C., & De la Hoz-Restrepo, F. (2011). Relaciones entre los comportamientos de riesgo psicosociales y la familia en adolescentes de Suba, Bogotá [Relationships between psychosocial risk behavior and the family in adolescents’ from Suba, an urban area in Bogotá]. Revista de Salud Pública, 13(1), 67–78. http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?pid=S0124-00642011000100006&script=sci_abstract&tlng=pt

- Hamburger, M., Basile, K., & Vivolo, A. (2011). Measuring Bullying Victimization, Perpetration, and Bystander Experiences: A Compendium of Assessment Tools. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/bullycompendium-a.pdf

- Hernández, M., & Gutiérrez, M. I. (2013). Factores de riesgo asociados a la intimidación escolar en instituciones educativas públicas de cuatro municipios del departamento del Valle del Cauca. Año 2009 [risk factors associated with school bullying in Local Authority Schools in four municipalities of Valle del Cauca, Colombia. Year 2009]. Revista Colombiana de Psiquiatría, 42(3), 238–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0034-7450(13)70016-7

- Highland-Angelucci, L., Valadez-Sierra, M. D., & Pedroza-Cabrera, F. (2015). La victimización producto del bulling escolar y su impacto en el desarrollo del niño desde una perspectiva neuropsicológica [Impact of Bullying Victimization on Children Development from a Neuropsychological Perspective]. Revista de Educación y Desarrollo, 32, 21–28. https://www.cucs.udg.mx/revistas/edu_desarrollo/anteriores/32/32_Highland.pdf

- Kaltiala-Heino, R., Rimpelä, A., Marttunen, M., & Rantanen, P. (1999). Bullying, depression, and suicidal ideation in Finnish adolescents: School survey. British Medical Journal, 319(7206), 348–351. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.319.7206.348

- Klomek, A. B., Kleinman, M., Altschuler, E., Marrocco, F., Amakawa, L., & Gould, M. S. (2013). Suicidal adolescents’ experiences with bullying perpetration and victimization during high school as risk factors for later depression and suicidality. Journal of Adolescent Health, 53(1), S37–S42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.12.008

- Leader, H., Singh, J., Ghaffar, A., & De Silva, C. (2018). Association between bullying and pediatric psychiatric hospitalizations. SAGE Open Medicine, 6, 6. https://doi.org/10.1177/2050312117750808

- Litman, L., Costantino, G., Waxman, R., Sanabria-Velez, C., Rodriguez-Guzman, V. M., Lampon-Velez, A., Brown, R., & Cruz, T. (2015). Relationship between peer victimization and posttraumatic stress among primary school children. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 28(4), 348–354. https://doi.org/10.1002/JTS.22031

- Liu, W., Qiu, G., Zhang, S. X., & Fan, Q. (2022). Corporal punishment, self-control, parenting style, and school bullying among Chinese adolescents: A conditional process analysis. Journal of School Violence, 21(1), 4–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220.2021.1985323

- Lucas, S., Jernbro, C., Tindberg, Y., & Janson, S. (2016). Bully, bullied and abused. Associations between violence at home and bullying in childhood. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 44(1), 27–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494815610238

- Lugones Botell, M., & Ramírez Bermúdez, M. (2017). Bullying: Aspectos históricos, culturales y sus consecuencias para la salud [Bullying: historical and cultural aspects and their consequences for health]. Revista Cubana de Medicina General Integral, 33(1), 154–162.

- Malta, D. C., Do Prado, R. R., Ribeiro Dias, A. J., Mello, F. C. M., Silva, M. A. I., da Costa, M. R., & Caiafa, W. T. (2014). Bullying and associated factors among Brazilian adolescents: Analysis of the national adolescent school-based health survey (PeNSE 2012). Revista Brasileira de Epidemiologia, 17(Suppl 1), 131–145. https://doi.org/10.1590/1809-4503201400050011

- Malta, D. C., Porto, D. L., Crespo, C. D., Silva, M. M. A., Andrade, S. S. C. D., Mello, F. C. M. D., Monteiro, R., & Silva, M. A. I. (2014). Bullying in Brazilian school children: Analysis of the national adolescent school-based health survey (PeNSE 2012). Revista Brasileira de Epidemiologia, 17(suppl 1), 92–105. https://doi.org/10.1590/1809-4503201400050008

- Ministerio de Salud. (1993, October 4). Resolución 8430 de 1993, Normas científicas, técnicas y administrativas para la investigación en salud [Scientific, technical and administrative standards for health research are established] (8430 de 1993).

- Montañez-García, M. V., & Ascensio-Martínez, C. A. (2015). Bullying y violencia escolar: diferencias, similitudes, actores, consecuencias y origen [Bullying and school violence: differences, similarities, actors, consequences and origin]. Revista Intercontinental de Psicología y Educación, 17(2), 9–38. https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=80247939002

- Moratto Vásquez, N., Cárdenas Zuluaga, N., & Berbesí Fernández, Y. D. (2012). Validación de un cuestionario breve para detectar intimidación escolar [Validation of a Short Questionnaire to detect School Bullying]. Revista CES Psicología, 5(2), 70–78.

- Mynard, H., Joseph, S., & Alexander, J. (2000). Peer-victimisation and posttraumatic stress in adolescents. Personality and Individual Differences, 29(5), 815–821. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(99)00234-2

- Nansel, T. R., Overpeck, M., Pilla, R. S., Ruan, W. J., Simons-Morton, B., & Scheidt, P. (2001). Bullying behaviors among US youth: Prevalence and association with psychosocial adjustment. JAMA, 285(16), 2094–2100. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.285.16.2094

- Niemelä, S., Brunstein-Klomek, A., Sillanmäki, L., Helenius, H., Piha, J., Kumpulainen, K., Moilanen, I., Tamminen, T., Almqvist, F., & Sourander, A. (2011). Childhood bullying behaviors at age eight and substance use at age 18 among males. A nationwide prospective study. Addictive Behaviors, 36(3), 256–260. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ADDBEH.2010.10.012

- Olweus, D. (1994). Bullying at school: Basic facts and effects of a school based intervention program. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 35(7), 1171–1190. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1469-7610.1994.TB01229.X

- Olweus, D. (2013). School bullying: Development and some important challenges. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 9(1), 751–780. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185516

- Ossa, F. C., Pietrowsky, R., Bering, R., & Kaess, M. (2019). Symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder among targets of school bullying. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 13(43), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/S13034-019-0304-1

- Paredes, M. T., Álvarez, M. C., Lega, L. I., & Vernon, A. (2008). Estudio exploratorio sobre el fenómeno del “bullying” en la ciudad de Cali, Colombia [An exploratory study on the phenomenon of “bullying” in the city of Cali, Colombia]. Revista Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales, Niñez y Juventud, 6(1), 295–317.

- Piñuel, I., & Oñate, A. (2006). AVE: Acoso y violencia escolar [Bullying and school violence]. TEA Ediciones. https://pseaconsultores.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/AVE.-Acoso-y-Violencia-Escolar.pdf

- Rivers, I., Poteat, V. P., Noret, N., & Ashurst, N. (2009). Observing bullying at school: The mental health implications of witness status. School Psychology Quarterly, 24(4), 211–223. https://doi.org/10.1037/A0018164

- Salas Viloria, K. E., & Combita Niño, H. A. (2017). Análisis de la convivencia escolar desde la perspectiva psicológica, legal y pedagógica en Colombia [Analysis of school coexistence from the psychological, legal and pedagogical perspective in Colombia]. Cultura Educación Y Sociedad, 8(2), 79–92. https://doi.org/10.17981/cultedusoc.8.2.2017.06

- Sigurdson, J. F., Wallander, J., & Sund, A. M. (2014). Is involvement in school bullying associated with general health and psychosocial adjustment outcomes in adulthood? Child Abuse & Neglect, 38(10), 1607–1617. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CHIABU.2014.06.001

- Smilkstein, G. (1978). The family APGAR: A proposal for a family function test and its use by physicians. Journal of Family Practice, 6(6), 1231–1239.

- Smilkstein, G., Ashworth, C., & Montano, D. (1982). Validity and reliability of the family APGAR as a test of family function. The Journal of Family Practice, 15(2), 303–311. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7097168

- Springer, A. E., Cuevas Jaramillo, M. C., Ortiz Gómez, Y., Case, K., & Wilkinson, A. (2016). School social cohesion, student-school connectedness, and bullying in Colombian adolescents. Global Health Promotion, 23(4), 37–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/1757975915576305

- Stapinski, L. A., Araya, R., Heron, J., Montgomery, A. A., & Stallard, P. (2015). Peer victimization during adolescence: Concurrent and prospective impact on symptoms of depression and anxiety. Anxiety, Stress and Coping, 28(1), 105–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2014.962023

- Takizawa, R., Maughan, B., & Arseneault, L. (2014). Adult health outcomes of childhood bullying victimization: Evidence from a five-decade longitudinal British birth cohort. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 171(7), 777–784. https://doi.org/10.1176/APPI.AJP.2014.13101401

- Ttofi, M. M., Farrington, D. P., Lösel, F., & Loeber, R. (2011). The predictive efficiency of school bullying versus later offending: A systematic/meta-analytic review of longitudinal studies. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, 21(2), 80–89. https://doi.org/10.1002/CBM.808

- Twemlow, S. W., Fonagy, P., & Sacco, F. C. (2006). The role of the bystander in the social architecture of bullying and violence in schools and communities. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1036(1), 215–232. https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1330.014

- van der Kolk, B. (2000). Posttraumatic stress disorder and the nature of trauma. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 2(1), 7–22. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2000.2.1/BVDKOLK

- Vieira, I. S., Torales, A. P. B., Vargas, M. M., & Oliveira, C. C. D. C. (2016). Atitudes de alunos expectadores de práticas de bullyng na escola [attitudes of bullying practices bystanders students at school]. Ciência, Cuidado e Saúde, 15(1), 163–170. https://doi.org/10.4025/cienccuidsaude.v15i1.29403

- Wolke, D., & Lereya, S. T. (2015). Long-term effects of bullying. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 100(9), 879–885. https://doi.org/10.1136/ARCHDISCHILD-2014-306667

- World Medical Association. (2013). World medical association declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association, 310(20), 2191–2194. https://doi.org/10.1001/JAMA.2013.281053

- Yang, X., Zhen, R., Liu, Z., Wu, X., Xu, Y., Ma, R., & Zhou, X. (2023). Bullying victimization and comorbid patterns of PTSD and depressive symptoms in adolescents: Random intercept latent transition analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 52(11), 2314–2327. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10964-023-01826-2