ABSTRACT

This study examines the dynamic between organisational culture and effectiveness within World-Wide Opportunities on Organic Farms (WWOOF) Australia as a case study in ecotourism. It extends current understanding of the intricate relationships among key stakeholders within ecotourism. Taking the interpretivist approach where reality is a composite of multiple perspectives, qualitative data was collected from a sample of 22 key stakeholders in WWOOF Australia through semi-structured interviews. The results indicate that WWOOF Australia operates using a clan culture and that this cultural typology generates efficacious outcomes for all stakeholders to differing degrees while simultaneously enabling environmentally sustainable and socially inclusive operations. The study findings make theoretical contributions to better understand the complex dynamics of relationships between key stakeholders in a non-traditional organisational culture, and practical implications for the successful operation of ecotourism.

Introduction

Ecotourism, a subsector of the mainstream tourism industry, is the fastest-growing tourism sector worldwide, growing at 20–25% annually (Ecotourism Australia, Citation2020). It represents a high-growth sector within the Australian tourism industry with a 14% increase (Ecotourism Australia, Citation2020) compared to mainstream tourism with a 2.5% increase (Austrade, Citation2020) in the same 2019–2020 financial period. Considered a crucial strategy in response to tourists’ demand for authentic, de-commodified experiences in nature and culture (Deville et al., Citation2016), and departing from commercial systems of tourism (Everingham et al., Citation2022), ecotourism continues to expand as a global movement (DeLorenzo & Techera, Citation2019). Ecotourism differs profoundly from mass tourism both ethically and operationally (Garrod & Fennell, Citation2023, Citation2022), in that it promotes nature-based tourist activities, meaningful cross-cultural experiences, ecological and cultural conservation, and sustainability by educating tourists and maximising benefits for local stakeholders (Fennell, Citation2014).

As a distinctive form of tourism, ecotourism is an important economic generator for rural and remote communities, creating community benefits, resilience, strong social outcomes, and sustainable employment opportunities (Ecotourism Australia, Citation2020). Significantly, in March 2020, 90% of Australian certified ecotourism businesses closed due to COVID-19 (Ecotourism Australia, Citation2020). As of September 2020, 26.8% of those businesses were once again fully operational, 46.4% offered limited services, and 26.9% remain closed (Ecotourism Australia, Citation2020). According to the UN Pacific Strategy 2018–2022 (United Nations, Citation2017), it has the potential to be a catalyst for the preservation of the natural environment and indigenous culture (Montes & Kafley, Citation2019), such as Australian indigenous cultures. As a non-mainstream form of tourism that attempts to reduce the negative externalities and enhance the beneficial tourism activity that could be engendered for local ecosystems, host communities, and industry (Beall et al., Citation2021), ecotourism embodies the ethics of environmental conservation and the prosperity of people, as opposed to the neoliberal economics associated with commercial tourism (United Nations, Citation2017). Moreover, it engenders political empowerment of local communities, and nurtures respect for diverse cultures and for human rights (Montes & Kafley, Citation2019).

Previous studies have established that certain cultures have a positive effect on organisational outcomes, but the relationship between organisational cultures and outcomes in the tourism industry has attracted little research attention (Yusof, Jamil, Said, et al., Citation2012). Notwithstanding its steady expansion as a global movement, ecotourism is largely under-researched (Lee & Son, Citation2016). Academic studies are limited on how its business model operates and contributes to assessments of organisational success (Weaver & Lawton, Citation2007). Thus, this study aims to bridge this gap in existing knowledge by providing new knowledge regarding the cultural characteristics of small businesses in ecotourism.

Given the strategic importance of ecotourism and the lack of studies on its organisational culture, the purpose of the current study is to examine the organisational culture and effectiveness dynamic in the context of World-Wide Opportunities on Organic Farms (WWOOF) Australia as a case study in ecotourism. Gregory et al. (Citation2009) argue that studies on how organisational culture impacts effectiveness are needed in non-mainstream ecotourism sectors that are rapidly growing within the Australian ecotourism market. Although pivotal for effectiveness, organisational culture has been neglected in ecotourism management studies (Kassim & Yusof, Citationn.d.), specifically in volunteer-based ecotourism which is a key organisational characteristic of WWOOF. Little attention has also been given to the development of the conceptualisation of organisational cultures in the context of ecotourism (Yusof, Jamil, and Jayaraman, Citation2012). This study addresses this knowledge gap and contributes to ecotourism and organisational research by examining the organising of WWOOF Australia as a member of an emerging global alternative ecotourism phenomenon (Deville, Citation2011).

This study has a broader scope than has been attempted previously, in that it incorporates an analysis encompassing four groups of participants’ perspectives at WWOOF Australia (owner, employees, hosts, volunteers). Using post-critically framed qualitative research, the study draws on review of the literature and lived experiences of 22 members of WWOOF Australia. Data triangulation, using documents, pictorial/visual representations, and in-depth semi-structured interviews with four levels of stakeholders, enables comparison of their perspectives and narratives, providing novel insights into the dynamic relationships in a non-traditional way of working.

As such, the study makes a number of theoretical and practical contributions. First, it extends the application of organisational culture theory in a new setting by exploring the unique dynamic between organisational culture and organisational effectiveness in ecotourism. Second, it contributes specifically to the literature on ecotourism by investigating the organisational culture of WWOOF Australia as a voluntary-based ecotourism operator. To better comprehend the effective operation of WWOOF Australia, the study integrates organisational culture theory with tourism and ecotourism theories (see McGehee, Citation2012). Third, our study findings provide recommendations for future research to ecotourism scholars, and more practically inform both policy makers and key stakeholders (owner, employees, hosts, volunteers) on key practices that enhance organisational effectiveness of WWOOF Australia and by extension of similar organisations. Specifically, these insights will be useful in the development of efficacious strategies for the success of the ecotourism industry.

Case study organisation: WWOOF Australia

WWOOF Australia is appropriated as a case study organisation for a two-fold rationale. First, it is a member of the international WWOOF movement which implies it has an established organisational apparatus (e.g. values, vision, policies, practices) required for the study of organisational culture. From a modest start in the UK in 1972, WWOOF has developed into 61 national organisations that share a common philosophy of promoting the organic food movement (Nordbo et al., Citation2020). The philosophy developed as a moral ideal, incorporating values of environmentalism, sustainability, and social justice (Kosnik, Citation2014). WWOOF as volunteer ecotourism contributes to the overall growth of ecotourism and has the potential to fulfil the criteria of “ideal” ecotourism (Wearing, Citation2003). The membership of WWOOF Australia, which has yet to return to pre-COVID-19 levels, consists of host-site owners and volunteers. Host-sites which operate across Australia must include an organic feature in their offering. Prior to COVID-19 WWOOF Australia was comprised of a combination of over 4000 hosts and volunteers with up to six part-time employees. As of October 2020, there were 892 hosts and 2,040 Australian and international volunteers.

Second, WWOOF Australia has a unique feature relative to its counterparts in other parts of the world (i.e. a for-profit entity), which might help explain its significant growth outstripping that of other operators and “backpackers” since the mid-1990s (Deville et al., Citation2016). Established in 1982 with the current headquarter located in East Gippsland, Victoria, it is as a single-person owned business, similar to other international WWOOF groups. As a member of the Federation of WWOOF (FoWo), WWOOF Australia operates according to the Federation’s guidelines, reflective of the values embodied within the WWOOF ethos. A crucial distinctive difference that makes WWOOF Australia a salient organisation for studying organisational culture, however, is its for-profit rather than a not-for-profit status in Australia. That is, hosts and volunteers have to pay membership fees to be able for their participation in the organisation. The for-profit status places a greater priority on its effective running of the organisation, hence underscoring the importance of its organisational culture and its effects on effectiveness.

While research into WWOOF as a global ecotourism organisation has gradually expanded within tourism studies since 2000, little research has been undertaken on WWOOF Australia. Research on WWOOF Australia has also has predominantly been undertaken using ethnography (see Kosnik, Citation2014; Nakagawa, Citation2017). In some cases, it has been interdisciplinary (see Nakagawa, Citation2020), often involving field work. In these studies, WWOOF Australia is typically presented as a notable example of a de-commodification of tourism that runs counter to the structures and consequences of free-market forces and neoliberalism (e.g. Deville, Citation2011; Deville et al., Citation2016; Kosnik, Citation2015; Nakagawa, Citation2017). The dominant discourse, however, is limited to WWOOF’s conceptualisation and construction as an alternative tourism experience with a focus on the host-volunteer relationship at the micro-social level. While WWOOF Australia is a for-profit entity, as aforementioned, no studies have looked at its commercial aspect.

As such, this present study focuses on the dynamic between the organising culture of WWOOF Australia and its operational effectiveness by examining the perspectives and narratives of four dominant players in the organisation – owners, employees, hosts and volunteers. To that end, we are guided by the following questions: (a) What are the cultural characteristics of an ecotourism organisation? and (b) How is the culture and effectiveness dynamic represented in an ecotourism organisation? The next section briefly reviews pertinent literature on volunteer-based ecotourism and organisational culture and effectiveness in volunteer-based ecotourism.

Literature review

Volunteer-based ecotourism

An increasingly important sector in tourism, ecotourism is typically predicated upon three definitional dimensions – nature-based, environmentally educated, and sustainably managed (DeLorenzo & Techera, Citation2019), though there is a higher emphasis recently on a fourth dimension, i.e. the ethical dimension (Fennell, Citation2021). The four dimensions have underpinned many ecotourism operators, particularly the voluntary ecotourism. Volunteerism in promoting environmental stewardship makes up the tourism modalities that are directly opposite to modes of exploitation and profiteering that are pervasive in commercial tourism (Miller et al., Citation2015; Mostafanezhad, Citation2013). However, they are under-represented and under-researched in the literature (Fennell & Garrod 2021).

The volunteer-based economic ecotourism practice is founded on the ideal of non-monetary exchange, avoiding capitalist notions of profit-making (Kosnik, Citation2014). It is embedded within the collaborative economy (Botsman & Rogers, Citation2010), allowing people to engage in a range of human-human and human-environment interactive exchanges in different spatial and temporal dimensions. The exchange encompasses equalising, non-exploitative, community-oriented and sustainability principles, which in combination provide a compelling alternative commitment to non-market ethical principles (Mostafanezhad & Hannam, Citation2014). Through their fee-based membership, volunteers make a mutually agreed arrangement for specified types of work (typically between four to six hours of work over 38 h) in exchange of food and accommodation provided by the host-site owner. Such interactive exchange is presumed to be equally beneficial for both parties and premised on micro-social relationships central to the operation of organisations like WWOOF Australia (Deville et al., Citation2016).

The voluntary and exchange-based nature of organisations like WWOOF Australia is what makes its organisational culture worth studying. On the one-hand, as a member of the expanding international WWOOF movement, WWOOF Australia provides people with the ability to combine travelling, volunteering, and sharing sustainable agricultural practices with compatible peers (i.e. as evident in the official three aims of WWOOF Australia are to: promote an educational exchange; promote a cultural exchange; and build a sustainable global community). On the other hand, however, it involves fee-based structure for individuals who want to volunteer their time and energy as members. In other words, since they are neither volunteers nor employees in the strictest sense of the words, its organisational culture would be distinct from that observed in typical not-for-profit and commercial organisations, respectively. The extent to which its organisational culture needs to be fine-tuned to ensure organisational effectiveness is the focus of the current study.

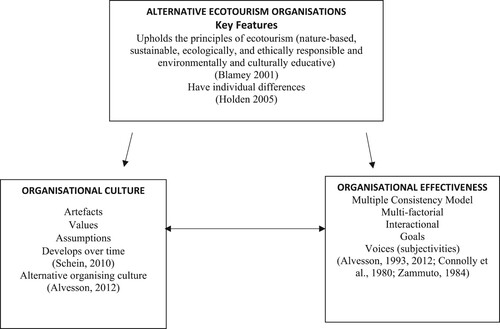

Organisational culture of voluntary-based ecotourism organisation

Organisational culture has been a key research topic in organisational research, and more recently has been increasingly associated with qualitative research as culture and its corollaries (e.g. symbol, myth, story, ritual, rite) have sparked scholarly interest within among organisational theorists (Alvesson, Citation2012). For the purpose of our qualitative study, we draw on Schein’s (Citation1985, p. 6) oft-quoted definition of organisational culture as “the pattern of basic assumptions that a group has invented, discovered, or developed in learning to cope with its problems of external adaption or internal integration” (Schein Citation1985, p. 6). As shared values, assumptions, expectations, and norms that knit a group of individuals together, organisational culture comprises of three dimensions (artefacts, values, and assumptions) and three generic subcultures (operator, engineering and executive, and micro-cultures) (Schein, Citation1983). Culture in this theoretical perspective also acknowledges the role of many different and nuanced historical, social, and political factors in creating and maintaining culture (Alvesson, Citation2012),

In contrast to the structural-functionalist perspective that assumes a common, dominant experiences of organisational members in the construction of its culture, we employ the interpretivist, process perspective that incorporates analyses sub-cultures and micro-cultures that make up an organisational culture. The interpretivist perspective is fitting for the current study as it accounts for the geographical, educational, and cultural differences that each host and volunteer brings to the voluntary-based ecotourism organisation under study (i.e. WWOOF Australia). According to Schein (Citation2019), at least three subcultures exist as manifestations of different subgroups in an organisation, namely (1) the operator subculture, which is based on human interaction with high levels of communication, trust and team work, (2) the engineering design subculture, which based on the common education, work experience and job requirements of its members and abstraction, and (3) the executive subculture, which is based on the fact that top managers share a similar view and concerns regarding the operation of the organisation and decision-making responsibilities. As distinct from subcultures, micro-cultures tend to be project-based and more dynamic as they evolve in small groups that share common tasks and histories (e.g. a distinct dialect within a language sub-group) (Schein, Citation2019).

Comprising of these sub-cultures and micro-cultures, ecotourism organisations have developed specific cultural characteristics that precipitate the achievement of ecotourism goals (Saurombe et al., Citation2018). As such, the limited literature regarding culture in ecotourism generally views culture as being ethical, responsible, and principled (Fennell & Garrod Citation2022). The development of an ethical culture produces more efficient, effective, and productive outcomes for stakeholders – internal and external (Nakagawa, Citation2020) relative to those organisations whose ethical practices are questionable (Malloy & Fennell, Citation1998). Furthermore, establishing a supportive organisational culture in ecotourism can provide useful insight to the policy makers and emerging economies regarding the culture of these businesses (Yusof, Jamil, and Jayaraman, Citation2012).

Organisational culture and effectiveness

To facilitate our analysis of organisational culture and effectiveness in WWOOF Australia, we employ a well validated cultural framework called the Competing Values Framework (CVF) (Quinn & Rohrbaugh, Citation1983a). The CVF is a robust mapping framework to understand how non-traditional organisational culture can affect organisational effectiveness, considering that effectiveness is a multidimensional concept that is typically understood differently by each stakeholder (Martin, Citation2002). Few studies have been undertaken to assess effectiveness in small to medium ecotourism (Yusof, Jamil, & Jayaraman, Citation2012) where effectiveness is generally associated with environmental and sustainability outcomes (Miller & Mair, Citation2015; Yusof, Jamil, & Jayaraman, Citation2012). More predominantly studies have portrayed effectiveness as a profit-orientated outcome that excludes other stakeholder priorities (Yusof, Jamil, & Jayaraman, Citation2012). This study encapsulates a process approach that takes a multiple constituency perspective to better capture the salient, distinctive features of ecotourism.

The organisational culture and effectiveness dynamic has been described as highly nuanced, incomplete, diverse, and contested (Seihl & Martin, Citation1990). Since there is no unanimous perspective on effectiveness and culture adopted by all researchers, different approaches to this dynamic have emerged (Wilderon, Glunk & Maslowski, in Ashkanasy et al., Citation2000). The dynamic is characterised by agreements, disagreements, ambiguities, and areas of fluidity that underpin subtle expressions of unity, disunity, and harmony (Seihl & Martin, Citation1990). For example, epistemological arguments formulated around how and why this linkage should or should not be examined (Denison & Mishra, Citation1995). Although the organisational theory literature indicates a nexus between culture and effectiveness, theoretical gaps exist in the literature on this dynamic (Gregory et al., Citation2009), particularly in the ecotourism realm (Yusof, Jamil, & Jayaraman, Citation2012: Yusof, Jamil, & Jayaraman, Citation2012). In order to bridge this gap in the literature and highlight the importance of the ethical and sustainable culture towards organisational effectiveness (Saurombe et al., Citation2018), the current study employs the CVF to allow multiple criteria associated with assessing organisational effectiveness, acknowledging that multiple constituencies will prefer certain values over others according to their organisational perspective and the interests they represent between culture types and effectiveness (Gregory et al., Citation2009; Hartnell et al., Citation2011).

The CVF provides a potentially more useful organising taxonomy for analysing the link between cultural types and organisational effectiveness in the organisation under study, because it includes a multi-consistency approach. Specifically, it encompasses an orthogonal three-dimensional taxonomy of the relationship – focus, structure, and means-ends – which represents competing core values held by different stakeholders in an organisation. These dimensions “represent what people value about an organisation’s performance” and they were pertinent to the construction of the culture-effectiveness dynamic in this case study. This framework also attempts to capture the culture and effectiveness across common dimensions and has accordingly been applied here.

The two structure and focus dimensions within the CVF overlay to delineate four cultural types: clan, adhocracy, market, and hierarchy. These types are internally or externally oriented. The clan type, also referred to as the collaborative culture, is internally oriented based on the assumption that human affiliation produces positive affective employee attitudes directed toward the organisation. It is supportive and co-operative, characterised by warmth, trust, safety and a supportive environment contributing to cohesive relationships in work settings (Berson et al., Citation2008; Cameron & Quinn, Citation2011). Further, it is reinforced by a flexible organisational structure, useful for the construction of effectiveness in this study. The adhocracy type is externally oriented and supported by a flexible organisational structure. The market culture type is externally oriented; clear goals and contingent rewards motivate employees to aggressively perform and meet stakeholders’ expectations. The hierarchy type is internally oriented and is supported by an organisational structure driven by control mechanisms. The adoption of the CVF enables the identification of the cultural type operating in WWOOF Australia and the assessment of its relationship with effectiveness as perceived by all constituent groups.

Methodology

To achieve the purpose of this paper, a single case study approach was used to interrogate the culture and effectiveness dynamic in ecotourism. This form of case study was deemed appropriate because it facilitated an in-depth inquiry that investigated a contemporary phenomenon within its real-life context (Yin, Citation2009). In addition, it employs multiple data-gathering techniques to ensure they are as rich and realistic (Denzin & Lincoln Citation2011). In this study data were collected from semi-structured interviews and organisational documents. As such, multiple perspectives and points of view can be captured to construct a complex and holistic depiction of a phenomenon of inquiry. Significantly, this methodology is commonly employed in ecotourism and environmental education research (Walter & Reimer, Citation2012) and using the interpretivist lens, it is especially fitting for exploring a topic devoid of much research (Merriam, Citation1998), such as the organisational culture-effectiveness dynamic in WWOOF Australia.

Once approval was obtained from the owner of WWOOF Australia, interview participants were recruited through advertisement posted on the WWOOF Australia forum and Facebook page. The final study sample comprised 22 participants who are current or past WWOOF Australia members over the age of eighteen (i.e. the WWOOF Australia owner, two employees, ten hosts and nine volunteers). The owner and employees were over the age of fifty; the host-sites consisting of farm and non-farm entities, were based in Queensland, New South Wales and Victoria, and the volunteers were from Australia and Germany. Other demographic details were not collected for this study. This limited sample size is not unusual for qualitative research where the focus is the data richness, rather than sample size, as evident in the detailed analysis and interpretation of participants’ accounts (Tomassini & Baggio, Citation2022). More importantly, data saturation was achieved.

The semi-structured interviews were conducted during 2020 and guided by an interview schedule comprising general and cohort-specific questions. The general questions relate to WWOOF Australia involvement and perceptions of culture and effectiveness, whereas the specific questions pertain to each cohort (e.g. the owner, management style; employees, cultural characteristics of WWOOF Australia’s headquarters; hosts, structuring the day; and volunteers, advantages and disadvantages of volunteering). Pilot testing of interview questions was not always necessary (Patton, Citation2002), and which was the case in our study as the principal researcher has had an experience and insight as a volunteer in WWOOF Australia. Participants were initially offered the opportunity to make a general remark relating to their history and/or involvement and experiences with WWOOF Australia before proceeding to the more substantial questions. The audio-recorded interviews lasted between 60 and 75 min and were transcribed as soon as possible. Each participant was assigned a consecutive number to ensure anonymity and confidentiality.

To supplement the interview data, relevant organisational documents were sourced from the WWOOF Australia book, websites, emails, and Facebook posts created by all stakeholders. Participants also gave consent to use these documents, and they permitted identifiable authorship. The non-organisational documents comprised a diverse range of forms, including books published about the organisation and the WWOOF movement, archival material, magazine articles and other media and art products. Data triangulation, drawing on a variety of sources such as written and electronic, enabled a nuanced comparison of participants’ perspectives and narratives, confirming or disconfirming information from other sources. This approach provided novel, valid, and rich insights and contextual information about the dynamic relationships between participant groups in a non-traditional way of working that cannot be directly observed.

Data analyses of both forms of data were conducted using NVivo 12. The process involved scrutinising textual and visual data collected, identifying, coding and themes. Member checking of the entire sample was undertaken almost one year after the initial interviews and during a complete COVID-19 lockdown in Melbourne, a partial lockdown in regional Victoria, and regional floods and power outages across Australia, to ensure trustworthiness (Senbeto & Hon, Citation2021). The member checking consisting of synthesised, analysed data from the whole sample (Birt et al. Citation2016), allowed participants to affirm if the results resonated with them. This interview process focused on confirming, modifying and verifying the interpretation of the data collected with all the participants through email.

Findings

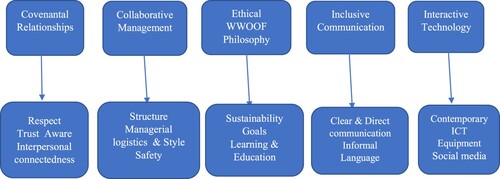

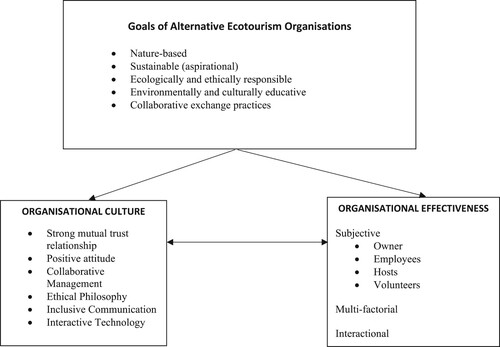

Content analysis of the interview data and documents/artefacts led to the identification of five coding schemes that represent five distinct themes characterising the culture of WWOOF Australia. Two levels of analytical categories were observed across the four levels of the owner, employees, host-site owners, and volunteers, resulting in the five themes of culture and their four respective sub-themes. The five themes are covenantal relationships, collaborative management, ethical WWOOF Philosophy, inclusive communication, and interactive technology. The main themes and subthemes relevant to the culture of WWOOF Australia are shown in .

Figure 1. Culture and effectiveness in alternative ecotourism organisations: A theoretically grounded conceptual framework.

The themes and sub-themes identified above signify a unique culture of WWOOF Australia that mostly resembles a clan culture, as defined within the CVF culture model. It is clearly distinct from the transactional and commodified culture associated with commercial tourism, or from that found in traditional organisations that is considered unitary, instrumental, centralised (Alvesson, Citation2012) and managerial (Alvesson & Due Billing, Citation2009). Consequently, this culture generates nuanced outcomes for each participant group.

The next section will elaborate on each theme in light of extant literature and illustrated by select participants’ quotes that best represent the theme. The verbatim quotes assist in establishing logical relationships between findings, analysis, and conclusions, and contribute to validity by affording diverse voices and guaranteeing a balance of views.

Covenantal relationships

The findings show that WWOOF Australia’s main cultural characteristics are relational, which aligns with other WWOOF Australia studies (e.g. Kosnik, Citation2014). This type of relationship can be categorised as covenantal, which is in opposition to contractual. Covenantal relationships have a primary concern for human relations and are based on mutual intimacy between people with a shared commitment to values, ideas, and goals, which is consistent with relationships in alternative ecotourism and intrinsic to the clan culture. Conversely, contractual relationships are commodifying not mutually beneficial and can be interpreted as formed on the basis of expectations, objectives, compensation, working conditions, benefits, timetables or constraints (Sendjaya, Citation2015). Covenantal relationships in this study consist of inter- and intra-relations between participant groups.

Relationships can generally be conceptualised as states of being connected: they can be associative, personal, organisational, causal, and temporal, and are processual. Relationality in WWOOF Australia can be referred to as the lived relationship maintained with others in the shared interpersonal space (Nakagawa, Citation2020), and therefore the relational dimensions as outlined can be applied to this organisation. Fundamentally, relationships in WWOOF Australia are premised on a social exchange (Mostafanezhad, Citation2013) comprising three fundamental aspects: reciprocity, relationships, and exchange (Coyle-Shapiro & Schor, Citation2007). This is evocative of the covenantal relationship type, in contrast to transactional and contractual relationships that are associated with traditional organisations (Schein, Citation2019) and Western managerial culture (Alvesson, Citation1993), which focus more on outcomes.

The results reveal that relationality constituted by the main four subthemes (i.e. trust, respect, understanding, personal connectedness) are meaningful in the construction of a relationship culture incorporating inter- and intra-participant group dimensions. This study reveals the different types of relationships existing in this alternative ecotourism organisation across the cohorts (symmetrical and associative), with the symmetrical type predominating. The results on the inter-group relationships demonstrate the complexities in the construction of the relationship theme. These findings provide understanding of the formation of relationships in the creation of a relationship culture within the case under study. A host offered understanding of relationships thus:

Relationships should be based on mutual respect and understanding … there should also be cooperation and courtesy (Host #20, male).

Volunteers should be respectful … Relationships should be based on mutual respect and understanding (Volunteer #5, male).

Collaborative management

Ecotourism will not be successful without effective management (Boo, Citation1990), and so this study’s findings indicate that management is significant in developing an ethical ecotourism culture in WWOOF Australia. This type of management can be categorised as collaborative, which is more participatory and inclusive (Cseh, Citation2016). This style better enables the attainment of WWOOF Australia’s goals, influences the development of alternative culture, and is aligned with WWOOF philosophy. This is in opposition to a managerial style that is more corporate and diminishes collaboration and inclusivity (Alvesson, Citation2012) and is based on conventional management logic. This is exemplified by the following employee quote:

It’s a completely different style of management than I’ve ever come across and a very positive one, and what I mean by that is, as people we need to be able to be creative … because this business model is very different from your normal product, you know, a company. (Employee # 3, female)

Ecotourism management, as a complex and multifaceted undertaking, requires a continuing process of action-based planning, assessment, monitoring, research, and adjustment to improve implementation and achieve desired goals (Weaver, Citation2001). Moreover, the findings on this theme reveal that management that incorporates inclusivity, and is adaptive, participatory, and collaborative, will be more effective in generating more sustainable outcomes. However, two hosts did comment on the need for more assertive management practices in relation to volunteers’ completion of tasks. Overall, the findings are congruent with Cseh’s (Citation2016) findings in nature-based tourism organisations and are emblematic of a social enterprise in ecotourism. The owner’s quote exemplifies elements of these observations:

I’d been given a tremendous opportunity and I had really good staff, and I learnt to delegate really quickly when it grew so quick, because I simply couldn’t do it all. (Owner #1, male)

The ethical WWOOF philosophy

The results identify that WWOOF Australia’s philosophy is ethical and aligned with the philosophy underpinning the human relations model of culture incorporating the clan culture. This philosophy is influenced by Aristotelian ethics that positions virtue above the economy, and in “doing good,” as reported in Tomassini and Baggio’s (Citation2022) findings on the organisational effectiveness construct in ethically driven small tourism firms. As such, an ethical philosophy underpins the guidelines, aims, ethics, objectives, ideology, mission, and operationalisation of WWOOF Australia (Deville et al., Citation2016). The results show that WWOOF Australia’s main principles incorporate sharing, sustainability and respect for nature that facilitate effectiveness.

The findings correspond with in studies of alternative ecotourism by Deville et al. (Citation2016) and volunteer tourism by Miller and Mair (Citation2015). Broadly, this philosophy is altruistic and implicit, in that its ethical soundness has more correspondence with collaborative practices associated with ecotourism (Khalid et al., Citation2010). Aspects of these philosophic observations are evidenced in the following employee quote:

Partly because it’s kind of an amazing [thing], having a job that is sustainable, good for the planet, and I feel really, good about going to work each day, you know, sometimes it’s hard to stop. (Employee # 2, female).

The host site’s natural environment should represent the principles of sustainability and organics if it can (Volunteer #14, female)

The key main finding under this theme is that an eco-centric code of ethics fashions WWOOF Australia’s culture and operations, and that this form of culture is co-created. There is an Aristotelean praxis-orientated applied and demonstrable aspect to the philosophy, implying a concrete and measurable “in-action” or technical dimension to the WWOOF philosophy, such as the degree of sustainable practices at host sites.

Inclusive communication

Communication has been identified as instrumental in the culture of WWOOF Australia. This finding has been reinforced by Aydin and Ceylan (Citation2009), who argue that communication is essential to the clan culture. Inclusiveness in de-commodified ecotourism can engender inter-cultural communication (Everingham et al., Citation2022) and can be ascribed to the communicative style in this study. Inclusive communication with a human-relations outlook is constituted by open-minded communication and empowering communicative practices (Horst, Citation2016) and was found to be present in the findings. A mutuality and affinity to the construction and conceptualisation of an inclusive communicative culture is evident in the following volunteer quote:

There seems to be no barriers, we can all talk about anything and how we feel. (Volunteer #17. male)

Perhaps having some information printed in a few languages so that we could understand better and feel a part of everything. (Volunteer #17, male)

Well sometimes when their English was low … they would say they knew what they had to do but they didn’t because mistakes were made. (Host # 14, male)

Interactive technology

Technology can be conceptualised as the organisation of knowledge to achieve outcomes. It is a product of human action with observable characteristics; it has been invented to meet a need; it is a physical presence; it can indicate much about basic human relationships; and it is a mechanism of cultural change (Brown, Citation2008). The technological culture established at WWOOF Australia symbolises these characteristics and denotes the essence of the organisation. The findings indicate that technology is influential in cultural construction. The use of technology reflects values and assumptions through operations, materials, and knowledge. More pertinently, the type of technology in WWOOF Australia can be categorised as interactive, which implies a shared interactive and collaborative dimension in the use of technology, such as the organisation’s Facebook page.

In contrast to conventional tourism, alternative ecotourism has embraced new interactive and digital technologies to perpetuate its aims, goals and objectives for the enhancement of greater involvement in this tourism typology, as illustrated in this case and in the case study by von der Weppen and Cochrane (Citation2012). This promotes a more sustainable and ecologically and socially responsible form of tourism engagement (Khalid et al., Citation2010), which concurs with an eco-centric philosophy.

Digitised technology, as applied in this case, has transformational power and is an enabler of sustainable development (Insensee et al., Citation2020). It is a way of enriching the environmental performance of an organisation and shows a better environmental performance than previous technologies (Insensee et al., Citation2020). It is also a technology that enhances mutual understanding, is emancipatory (Botsman & Rogers, Citation2010), and is instrumental for promoting more effective communications for all participant groups to differing degrees. This is in contrast to technology that develops prediction and control (a contemporary command and control technique) (Schein & Schein, Citation2016).

The interview data and suggest that the use of interactive technology in WWOOF is predominantly for worthy purposes, which concurs with Deville’s (Citation2011) and Cseh’s (Citation2016) WWOOF studies. This type of technological use facilitates change and shapes interactions at different WWOOF Australia sites as evident in pictorial representation. It is a driving force of change for the development of the business and a means to escape capitalist production and consumption similarly found by McGehee (Citation2012) in a volunteer tourism study. One volunteer in this present study did, however, report that it was not essential for all technological sources to be interactive; it would be preferable for them all to be functional, stable, and reliable.

The findings suggest that technologies in the present case usually resonate with the WWOOF philosophy and are often alternatives, underpinning sustainable practices and lifestyles associated with the WWOOF movement. Such technologies are interactive, multi-dimensional, multi-functional, and sub-culturally differentiated, depending on the technological modality’s type, usage, and functionality. Additionally, they are constituted by situational, environmental, spatial, and temporal dimensions. Volunteer’s offered understanding of interactive technology:

The possibilities to connect digitally weren’t advanced but many hosts didn’t have the internet or weren’t familiar with it. (Volunteer #19, female)

I also needed to be able to show and explain to my sons how to use the equipment, so it had to be versatile and adaptable. (Volunteer #12, male)

This section has discussed the five key themes relevant to the culture of WWOOF Australia. The findings reflect the complex and multi-dimensional nature of the key themes and interconnectedness to varying degrees between and within each participant group. The identified key themes aid the determination that, in general, consistency of themes, rather than inconsistency, prevails. The findings have enabled the development of a model to represent the dynamic as pertinent to alternative ecotourism. Two quotes to represent the unique culture of WWOOF Australia is presented:

… WWOOF Australia is fairly unique in the way it operates … we support young families and single dads like mine was when we WWOOF-ed as a family (Host # 22, male)

I enjoy the laid-back-ness of the organisation … I could ask for more time to complete a task and they’d say yes (Volunteer #16, male)

Discussion

The primary aim of this study was to explore the culture-effectiveness dynamic in ecotourism organisations. In-depth interviews with four different stakeholder groups in WWOOF Australia and examination of relevant organisational documents shows that WWOOF Australia has a strong clan culture which influences its effectiveness. There is data and clan congruence between the study findings and reality in the field. In addition, the process of member checking to verify our interpretations of data provided further evidence of credibility of the key study finding on how the clan culture shapes the effective running of WWOOF Australia. Importantly, underlying the attainment of key stakeholder outcomes is a strong commitment to upholding WWOOF’s ethical philosophy that revolves around eco-centrism. Our finding provides qualitative evidence in support of prior theorising on the positive relationship between the clan culture and effectiveness in ecotourism.

Specifically, we found that across WWOOF Australia the clan culture as a non-traditional cultural type comprises five main themes that underpin their understanding and operationalisation of effectiveness. Combined these five themes are valuable for stakeholders in obtaining the three goals of WWOOF Australia as they encompass inter-actional and inter-relational dimensions. Indicated by this thematic combination is that organisational practices that sustain the unique cultural dimensions of volunteer ecotourism enact efficacious outcomes as perceived by participant cohorts.

The identification of this alternative culture alludes to the type of values, value judgements beliefs and assumptions underlying each theme consistent with Schein’s (Citation1983) model of culture. These value dimensions as adopted by WWOOF Australia, have afforded meaningful and productive outcomes for stakeholders. This collaborative cultural type has also been found to be nuanced, co-created and fluid which enables the prosecution of effectiveness at differing levels of the organisation. It is based on interrelationships and premised on internalities and externalities. This culture values membership participation and decision-making leading to empowerment and inclusivity, which are determinants of efficaciousness as practised in WWOOF Australia. This cultural typology also elicits an expeditious response to difficult and uncertain situations (Senbeto & Hon, Citation2021) such as COVID-19 as was experienced in WWOOF Australia.

Significantly, the clan culture in this study is differentiated at levels of the organisation, between participant cohorts, and contains sub-cultural and micro-cultural dimensions. In addition, key stakeholders have varying degrees of agency in culture creation, in contrast to the minimal agency associated with a subject culture (Denison & Mishra, Citation1995) and commercial tourism. Importantly, the multiple constituent approach has allowed effectiveness to be conceptualised differently by each stakeholder group, facilitating nuanced evaluations of effectiveness. Furthermore, the subcultural nature of the organisation under study, as represented by a combination of Schein’s three subcultural types (operator, engineering and executive), has allowed the development of synergistic interactions in the culture and effectiveness dynamic. Micro-cultures have been identified to a lesser degree, using the cultural theory of Schein (Citation2004). These are differentiated depending on the subcultural construction they naturally associate with.

The non-traditional culture at WWOOF Australia, consistent with Schein’s (Citation1983) organisational and general cultural theorising, is notable for being inter-relational, characterised by internalities and externalities, differentiated at levels of the organisation and between participant groups; and maintaining sub- and micro-cultural dimensionality. By demonstrating that the clan culture of WWOOF Australia shapes key stakeholder outcomes in the organisation, this study addresses the research gap in the culture-effectiveness dynamic in alternative volunteer ecotourism.

The findings provide contributions to existing theoretical and practical knowledge in the field of alternative ecotourism, ecotourism, and sustainable tourism. It extends the knowledge of the creation of an ethical, authentic, and inclusive ecotourism culture that precipitates efficacious outcomes in the Australian context. These contributions are outlined as follows.

Contribution to theory

The study has several important theoretical implications. First, it extends organisational culture theory in a new setting by exploring the unique dynamic between culture and effectiveness in alternative ecotourism. Findings confirm the intricate link between culture and effectiveness, thus providing further qualitative evidence to support prior and more general theorising (e.g. Denison & Mishra, Citation1995). To better understand the operation of WWOOF Australia, the study integrates organisational culture theory with tourism and ecotourism theories.

Second, this is the first study to develop a comprehensive model describing and explaining, in qualitative terms, the dynamic between culture and effectiveness in alternative ecotourism. It enhances the scope of alternative organisational culture literature by presenting an understanding of culture and effectiveness at all levels of alternative ecotourism organisation.

Third, the study confirms a strong prevalence of the clan culture at WWOOF Australia. This culture influences how different actors relate to each other and how stakeholders achieve key outcomes (i.e. global sustainability, cultural exchange, education exchange).

Fourth, the findings suggest that the operational effectiveness in WWOOF Australia is perceived differently by participant cohorts (i.e. the owner, employees, hosts and volunteers), and at different locations. It confirms that organisational effectiveness is a matter of contextualised and subjective perception, and hence is multi-dimensional, which is congruent with Schein’s (Citation1983) organisational theory. The inclusion of multi-vocality in this study has broadened representation and presented a more complex and comprehensive analysis of the culture-effectiveness dynamic in WWOOF Australia.

Practical contributions

The practical implications relating to participant groups and policy development are as follows. The clan cultural characteristics identified a need for group members to be acknowledged and continually shaped and nurtured to produce efficacious organisational outcomes across all levels of an organisation. Cultivation of context-specific cognitive and ingenious technological skills is essential for the smooth running of a business at the ownership level and ensuring sustained success and growth.

The study highlights the importance of participation strategies that are characterised by versatility, adaptability, and resilience. To support the business, employees should model the philosophical tenets of the WWOOF movement to instil an alternative culture. Hosts need to adopt and develop strategies and mechanisms for establishing and maintaining a functioning host site that concurs with WWOOF Australia’s policies and the ethical WWOOF philosophy. The application of this knowledge will help implement suitable conditions for the development of a clan culture at the host site, facilitating the attainment of organisational goals. The acquisition of membership knowledge will lessen perceived uncertainty and allow readiness for full inclusion of volunteers in the exchange process and for the cocreation of a clan culture.

Policy contributions

Effective policy development and appropriate implementation strategies will enable WWOOF Australia as a small business, to advance, prosper and progress in an assured, adaptable, and ethical manner. This will facilitate certainty, reduce misunderstandings, and increase participation in the organisation, thereby enhancing participation in Australian ecotourism. The results of this study can be used by the owner of WWOOF Australia and host-site owners to design effective policies that encourage the development of a clan culture across all levels of the organisation. These policies should be influenced by the primary focus on the five key themes and their respective four subthemes identified in this study. The policies will facilitate the acquisition of goals at the micro and meso levels of the organisation.

Conclusion

This is the first study to investigate the culture-effectiveness dynamic using an ecotourism organisation (such as WWOOF Australia). Consequently, the findings have enriched and deepened the hitherto scarce literature on this type of organisation and have enabled a more complex appreciation of its culture-effectiveness dynamic. The contributions proposed here enable ecotourism organisations to improve their practices, and the implications discussed provide insight into the potential impacts of these improvements on the organisation’s future development.

The overall results from this case study highlight the depth of knowledge required for an adequate understanding of the culture and goal attainment practices of non-traditional tourism organisations. This depth of knowledge was facilitated by applying Schein (Citation1983) and Alvesson’s (Citation2012) cultural analysis, as well as Quinn and Rohrbaugh’s (Citation1983) CVF. Based on our findings, it can be concluded that the CVF was the most productive way to examine the culture-effectiveness dynamic in an ecotourism organisation. As such, it proved a useful and instructive model to identify and explore clan-cultural characteristics in WWOOF Australia and their relationship with effectiveness.

Further conclusions indicate that underlying the successful attainment of planned outcomes is a commitment to upholding WWOOF’s ethical philosophy and its eco-centrism. They also indicate an important contribution of collaborative economic practices to faster successful attainment of planned outcomes. Further research is needed to confirm and extend these findings.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Alvesson, M. (1993). Cultural perspectives on organizations. Cambridge University Press.

- Alvesson, M. (2012). The culture of organisations. Sage.

- Alvesson, M., & Due Billing, Y. (2009). Understanding gender and organisations. Sage.

- Ashkanasy, N., Wilderom, C., & Peterson, M. (2000). Handbook of organizational culture and climate. Sage.

- Austrade. (2020). Department of trade and tourism.

- Aydin, B., & Ceylan, A. (2009). Does learning capacity impact on organisational effectiveness? Research analysis of the metal industry: Development and learning, organisation. International Journal, 23(3), 21–23. https://doi.org/10.1108/14777280910951577

- Beall, J., Boley, B., Landon, A., & Woosnam, K. (2021). What drives ecotourism:Environmental values or symbolic conspicuous consumption? Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29(8), 1215–1234. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1825458

- Berson, Y., Oreg, S., & Dvir, T. (2008). CEO values, organizational culture and firm outcomes. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 29(5), 615–633. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.499

- Birt, L., Scott, S., Cavers, D., Campbell, C., & Walter, F. (2016). Member Checking. Qualitative Health Research, 26(13), 1802–1811. http://doi.org/10.1177/1049732316654870

- Boo, E. (1990). Ecotourism: The potentials and pitfalls. Worldwide Fund for Nature.

- Botsman, R., & Rogers, R. (2010). What’s mine is yours: How collaborative consumption is changing the Way We live. Harper Collins.

- Brown, L. (2008). A review of the literature on case study research. Canadian Journal for New Scholars in Education, 1(1), 1–13.iPa©.

- Cameron, K. S., & Quinn, R. E. (2011). Diagnosing and changing organizational culture based on competing values framework (3rd ed.). Jossey-Bass.

- Coyle-Shapiro, J., & Schor, J. (2007). Employee-organization relationship: Where do we go from here? Human Resource Management Review, 17(2), 166–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2007.03.008

- Cseh, G. (2016). Practicing sustainability and change in nature-based tourism. Unpublished Master Thesis, University of Graz (Austria), viewed October 2020, http://Hochschulschrift/ Practicing sustainability and change in nature-based tourism (uni-graz.at)

- DeLorenzo, J., & Techera, E. (2019). Ensuring good governance of marine wildlife tourism: A case study of ray-based tourism at hamelin Bay, western Australia. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 24(2), 121–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2018.1541186

- Denison, D., & Mishra, K. (1995). Toward a theory of organisational culture and effectiveness. Organization Science, 6(2), 204–223. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.6.2.204

- Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2011). The Sage handbook of qualitative research (4th edition). Sage.

- Deville, A. (2011). Alice in WWOOF-erland: Exploring symbiotic worlds beyond tourism. Doctor of philosophy thesis. University of Technology.

- Deville, A., Wearing, S., & McDonald, M. (2016). Diverse economies approach for promoting peace and justice in volunteer tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 24(1), 91–113. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2015.1049607

- Dillette, A., Douglas, A., & Martin, D. (2017). Residents’ perceptions on cross-cultural understandings as an outcome of volunteer tourism programmes: The Bahamian family island perspective. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 25(9), 1222–1239. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2016.1257631

- Ecotourism Australia Ltd. (2020). State of the industry report ecotourism in Australia (2019-2020), September 2020. https/www.ecotourism.org.au

- Everingham, P., Young, T., Wearing, S., & Lyons, L. (2022). A diverse economy approach for promoting peace and justice in volunteer tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 30(2-3), 618–636. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2021.1924179

- Fennell, D. (2014). Ecotourism. Routledge.

- Fennell, D., & Garrod, B (2022). Seeking a deeper level of responsibility for inclusive (eco)tourism duty and the pinnacle of practice. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 30(6), 1403–1422. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2021.1951278

- Fennell, D. A. (2021). Ecotourism and accessibility for persons with disabilities. In Ecotourism and accessibility for persons with disabilities. Taylor & Francis Group.

- Garrod, B., & Fennell, D. (2023). Strategic approaches to accessible ecotourism: Small steps, the domino effect and not paving paradise. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 31(3), 760–777. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669.582.2021.2016778

- Gregory, B., Harris, S., Armenakis, A., & Shook, A. (2009). Organisational culture and effectiveness: A study of values, attitudes, and organisational outcomes. Journal of Business, 62(7), 673–679. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2008.05.021

- Habermas, J. (1991). Communication, and the evolution of society. Pluto Press.

- Hartnell, C., Yi Ouchi, A., & Kinicki, A. (2011). Organizational culture and organizational effectiveness: A meta-analytic investigation of theoretical suppositions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(4), 677–694. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021987

- Horst, M. (2016). Spirituality, nature, and self-transformation on the WWOOF farm. Unpublished Master thesis, University of Wageningen (Germany), viewed July 2019, http://edepot.wur.ni/386460

- Insensee, C., Teuteberg, F., Griese, K. M., & Topi, C. (2020). The relationship between organizational culture, sustainability, and digitalization in SMEs: A systematic review. Journal of Cleaner Production, 275, ), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.122944

- Kant, I. (1970). Kant’s political writings. Hans Reiss. (Ed.) Cambridge University Press.

- Kassim, M., & Yusof, N. (n.d.). Organisational culture of a lake-based eco-tourism resort: Case study of Tasik Kenyir, Malaysia. https://doi;10.51762251-3426_THoR13.19

- Khalid, S., George, R. A., Wahid, N., Amran, A., & Abustan, I. (2010). Balancing between profitability and conservation: The case of an eco-tourism resort in Malaysia. In Proceedings of the Regional Conference on Tourism Research, 13-14 December, Penang, Social Transformation Platform, 123-135. Kuala Lumpur.

- Kosnik, E. (2014). Work for food and accommodation: Negotiating socio-economic relationships in non-commercial work-exchange encounters. Hospitality & Society, 4(3), 275–291. https://doi.org/10.1386/hosp.4.3.275_1

- Kosnik, E. (2015). The community economy of the extended farm household of WWOOF hosts and volunteers. ÖZV 69/118, l3(4), 234–254.

- Lee, J., & Son, Y. (2016). Stakeholder subjectives toward ecotourism development using Q methodology: The case of Maha ecotourism site in Pyeongchang, Korea. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 21(8), 931–951. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2015.1084347

- Malloy, C., & Fennell, A. (1998). Codes of ethics and tourism: An exploratory content analysis. Tourism Management, 19(5), 453–461. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(98)00042-9

- Martin, J. (2002). Cultures in organizations: Mapping the terrain. Sage.

- McGehee, N. (2012). Oppression, emancipation, and volunteer tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 39(1), 84–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2011.05.001

- Merriam, S. B. (1998). Case study research in education: A qualitative approach. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Miller, C., & Mair, H. (2015). Organic farm volunteering as a de-commodified tourist experience. Tourist Studies, 15(2), 191–204. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468797614563436

- Miller, D., Merrilees, B., & Coghlan, A. (2015). Sustainable urban tourism: Understanding and developing visitor pro-environmental behaviours. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 23(1), 26–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2014.912219

- Montes, J., & Kafley, B. (2019). Ecotourism discourses in Bhutan: Contested perceptions and values. Tourism Geographies, 24(6-7), 1173–1196https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2019.1618905.

- Mostafanezhad, M. (2013). The geography of compassion in volunteer tourism. Tourism Geographies, 15(2), 318–337. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2012.675579

- Mostafanezhad, M., & Hannam, K. (2014). Moral encounters in tourism. Ashgate.

- Nakagawa, Y. (2017). WWOOFING nature: A post-critical ethnographic study. (Doctor of Philosophy), Monash University.

- Nakagawa, Y. (2020). WWOOF ecopedagogy: Linking ‘doing’ to ‘learning’. Australian Journal of Environmental Education, 33(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1017/aee.2016.30

- Nordbo, I., Sergovia-Perez, M., & Mykletun, R. (2020). WWOOF-ers in Norway - Who are they? Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 20(5), 419–437. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2020.1766559

- Patton, M. Q. (2002). Designing qualitative studies. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods, 3, 230–246.

- Quinn, R., & Rohrbaugh, J. (1983a). A competing values approach to organisational effectiveness. Public Productivity Review, 5(2), 122–144. https://doi.org/10.2307/3380029

- Quinn, R. E., & Rohrbaugh, J. (1983). A Spatial Model of Effectiveness Criteria: Towards a Competing Values Approach to Organizational Analysis. Management Science, 29(3), 363–377. http://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.29.3.363

- Saurombe, H., du Plessis, Y., & Swanepoel, S. (2018). An integrated managerial framework towards implementing an ecotourism culture in Zimbabwe. Journal of Ecotourism, 17(2), 107–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/14724049.2017.1293066

- Schein, E. (1983). Organisational culture and leadership. Jossey-Bass.

- Schein, E. (2019). New Era for culture, change and leadership. Sloan Management, 60(4), 52–58.

- Schein, E. H. (1985). Organizational culture and leadership. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Schein, E. H. (2004). Organizational culture and leadership (3rd edition). Jossey-Bass.

- Schein, E. H., & Schein, P. (2016). Organizational culture and leadership (5th ed.). Jossey-Bass/John Wiley & Sons.

- Seihl, C., & Martin, J. (1990). Organizational culture: A key to financial performance? In B. Schneider (Ed.), Organizational climate and culture (pp. 241–281). Jossey-Bass.

- Senbeto, D., & Hon, A. (2021). Shaping organizational culture in response to tourism season- ality: A qualitative approach. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 27(4), 466–478. https://doi.org/10.1177/13567667211006759

- Sendjaya, S. (2015). Personal and organizational excellence through servant leadership. Springer International.

- Steers, R. (1976). When is an organization effective? A process approach to understanding effectiveness. Organisational Dynamics, 5(2), 50–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/0090-2616(76)90054-1

- Tomassini, L., & Baggio, R. (2022). Organisational effectiveness for ethical tourism action: A phronetic perspective. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 30(8), 2013–2028. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2021.1963974

- United Nations. (2017). United Nations Pacific Strategy 2018-2022. http://www.unicef.org/about/execboard/files/Final_UNPS_2018-2022_Pacific.pdf

- von der Weppen, J., & Cochrane, J. (2012). Social enterprises in tourism: An exploratory study of operational models and success factors. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 20(3), 497–511. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2012.663377

- Walter, P., & Reimer, J. K. (2012). The “ecotourism curriculum” and visitor learning in community-based ecotourism: Case studies from Thailand and Cambodia. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 17(5), 551–561. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2011.627930

- Wearing, S. (2003). Volunteer tourism: Experiences that make a difference. CABI.

- Weaver, D. (2001). The encyclopedia of Eco tourism. CABI International.

- Weaver, D. B., & Lawton, L. J. (2007). Twenty years on: The state of contemporary ecotourism research. Tourism Management, 28(5), 1168–1179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2007.03.004

- Yin, R. K. (2009). Case study research: Design and methods (4th ed.). Sage.

- Yusof, N., Jamil, M., & Jayaraman, K. (2012). Exploring the organisational culture construct for small and medium enterprises in the ecotourism of emerging economies. Development Planning, 7(4), 457–471.

- Yusof, N., Jamil, M., Said, I., & Ali, A. (2012). Organizational culture and tourist satisfaction in a lake-based tourism area. American Journal of Applied Sciences, 9(3), 417–424. https://doi.org/10.3844/ajassp.2012.417.424