ABSTRACT

This study explores how the fear of missing out (FOMO) affects the flow experience, festival satisfaction, and revisitation intention of attendees at a country music festival. Based on the cognitive appraisal theory, the study surveyed 317 participants and found that several factors contribute to the flow experience, which in turn impacts festival satisfaction and revisitation intention. The results reveal that participants with higher FOMO levels have a higher intention to revisit, with festival satisfaction mediating the relationship. This research repositions FOMO as the fear of missing out on the same event that individuals are attending. By highlighting this alternative understanding, the study suggests that FOMO can be leveraged as a resource for event organizers, potentially providing opportunities for engagement and enhancing attendee experiences. The proposed conceptual model and the insights gained from this research offer valuable contributions to the field and provide a foundation for further investigation and theoretical development.

Introduction

The study of events has become one of the most prolific areas in tourism research in recent decades owing to their contribution to tourism development (Getz & Page, Citation2016). Specifically, event tourism attracts tourists to hosting destinations during off-peak season, helps the destinations to build a positive image and creates employment opportunities for the local communities (Li et al., Citation2021). Among the various types of events, music festivals, which are distinct from other types of events due to their focus on themed celebrations (Getz & Page, Citation2016), have occupied a significant status (Lee & Kyle, Citation2014). Notably, the demand for festival tourism has been surging exponentially since the early 2000s with a £313 million economic impact recorded for a single event held in the UK (BBC, Citation2018). For destinations, there appear to be significant benefits to hosting music festivals of different scales, thereby indicating the importance of managing and handling music festivals in a competitive business manner. Given the value of event tourism, much research has been conducted to create an event knowledge base. Yet, a few research gaps remain.

Firstly, the common focus of research into festival and event tourism has been predominantly associated with operational issues of events, but overlooking the impact of these issues on participants’ experiences (Laing, Citation2018). One cogent example is the work on flow experience. As music festivals can be seen as an experiential tourism product, it is critical for event organizers to understand and manage the different aspects of a festival so that they can create an immersive environment that encourages repeat participation. The optimal state of flow hinges on several antecedents such as skill performance, ambience, attendees’ self-congruence, other consumers’ passion, and consumer-to-consumer interaction (Ding & Hung, Citation2021). When the individuals feel in harmony with the service setting and their skills and knowledge match the experience, they will be in the flow state that can ultimately lead to high involvement and total absorption (Fu et al., Citation2017). Even though there have been calls for more research on understanding how flow experience can be obtained in different research contexts, flow studies are centered on physical activities and sports (deMatos et al., Citation2021) and few studies have been conducted on visitors’ flow experience when attending music festivals (Ding & Hung, Citation2021).

Alongside the concept of flow experience is the fear of missing out (FOMO). FOMO can be seen as an anxiety condition caused when an individual perceives he/she may miss out on something rather than gain something (Kim, Lee, et al., Citation2020). It is also a phenomenon arising from the human need for belongingness and popularity (Hayran et al., Citation2020). Previous studies such as Al Rousan et al. (Citation2023) have found that many attendees participate in music festivals not only to satisfy functional needs but also to foster social connectedness. Following this line of thought, in the context of festival tourism, visitors may gravitate towards festival participation only if the festival is perceived as a resource to connect with others, a tool to develop social competence, and a chance to develop social ties (Przybylski et al., Citation2013). Unlike other forms of definition of FOMO, this study reconceptualize FOMO as the fear of missing out on the same event that individuals are attending. Traditionally, FOMO refers to the anxiety or apprehension that arises from the fear of missing out on enjoyable experiences or opportunities in general. Many of the studies such as Kim, Lee, et al. (Citation2020) conceptualize FOMO as the idea that others are having exciting or fulfilling experiences that one is not a part of. Differentiating this reconceptualization from the traditional definition of FOMO highlights the contextual specificity of fear, suggesting that the fear is not just about missing out on any experience but about missing out on a particular event that others are actively engaged in. This narrower definition would address a gap in literature that would potentially advance our understanding of the complex dynamics involved in event experiences and provide valuable insights for both theory development and practical applications in the field of event management.

In addition, there is a limited understanding of festival tourism. Despite festival tourism being termed “an emerging giant” a few decades ago, empirical literature on the subject is not substantial in quantity (Laing, Citation2018). Meanwhile, existing studies primarily deal with events organized in developed or emerging countries, including the USA, the UK, Australia and China (Özdipçiner et al., Citation2020). As such, this study responds to call by Özdipçiner et al. (Citation2020) to further research into the behavior of festival attendees participating in festivals held in the context of different countries, especially developing countries in Asia. Finally, while festival tourism is gaining momentum again in the post-COVID era, it is important to highlight that the pandemic has significantly altered consumers’ mindset (Tan et al., Citation2023). While there are papers such as Ding and Hung (Citation2021) that examine factors influencing revisit intention of festivals, our study differentiates as this is the first few papers that focus on the resumption of face-to-face events after the COVID-19 pandemic. Earlier papers such as Ding and Hung (Citation2021) predominantly focus on events before the pandemic. While it provides good insight, its relevancy is questionable. After all, the pandemic has significantly impacted the music festival industry, leading to changes in attendee expectations, experiences, and overall satisfaction (Chi et al., Citation2021). In other words, it reshaped people's attitudes and expectations towards public gatherings and events. Factors like crowd size, health and safety measures, lineup diversity, and overall festival organization may have gained or lost importance. Therefore, the theoretical and practical significance of this study cannot be underestimated. Due to the novelty of COVID-19, the implications of the pandemic on event tourism as well as the research conducted on events held post-COVID remain understudied thereby creating grounds for further research.

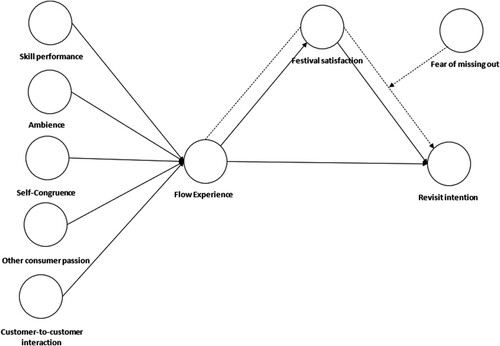

Based on the aforesaid, this present study aims to ascertain the antecedents (skill performance, ambience, self-congruence, other consumers’ passion and consumer-to-consumer interaction) that contribute to festival attendees’ flow experience when attending a music festival in Malaysia post pandemic and the subsequent effects on their satisfaction and revisit intention. To better understand the interrelationship of the different constructs, we also propose a moderated mediation model in which flow experience influences revisit intention, with satisfaction as a mediator and FOMO as a moderator.

Study context

Malaysia has a thriving music festival scene, with several annual events that attract both local and international audiences. Some of the most notable music festivals in Malaysia include the Good Vibes Festival, an annual music festival that has been held in Kuala Lumpur since 2013. The festival showcases a mix of local and international artists across various genres, including indie, electronic, and hip-hop. Another would be the Rainforest World Music Festival (RWMF). This is a three-day music festival that takes place in Sarawak, Borneo. The festival features traditional and contemporary music from around the world, with a particular focus on world music and indigenous music (Ho et al., Citation2022). Similarly, the Miri Country Music Festival (MCMF) is renowned as one of the most prominent country music festivals in Southeast Asia, with its distinct feature of offering a diverse range of activities throughout the occasion, making it a lifestyle and social gathering that caters to people of all ages and suitable for families (Tan, Sim, Chai, et al., Citation2020).

The impact of these music festivals on Malaysia's culture and economy has been significant (Chen & Lei, Citation2021; Ding & Hung, Citation2021). First, music festivals provide a platform for local artists to showcase their talent and gain exposure, while also bringing in international acts and audiences. This helps to promote Malaysia's music scene and boost the country's cultural profile (Sia et al., Citation2015; Tan, Sim, Chai, et al., Citation2020). Additionally, music festivals generate significant revenue for the local economy, with tourists traveling from all over the world to attend these events. According to a report by the Malaysian Association of Tour and Travel Agents (MATTA), the music festival industry in Malaysia is estimated to be worth around RM$2.2 billion (approximately US$540 million) annually (MATTA, Citation2021). This includes revenue generated from ticket sales, merchandise, food and beverage, accommodation, transportation, and other related industries.

One such festival is the MCMF. Miri, an eastern Malaysian city, has gained its fame, due to its discovery of oil-fields that attracted attention from international oil and gas investors. This has turned the city into a multicultural hub (Tan, Sim, Chai, et al., Citation2020). As stated by Then (Citation2017), the city also housed numerous UNESCO heritage sites such as the Niah National Park. Due to its rich social, cultural, and economic history, Miri has become a popular destination for tourists and expatriates from different countries. The city has earned a reputation for organizing events that display its multi-ethnic and multi-religious identity, such as the MCMF. This festival features country music acts from around the world and offers a range of activities suitable for the whole family, making it a unique and popular event in Southeast Asia (Tan, Sim, Chai, et al., Citation2020). It is natural that this study focus on MCMF, given its distinctive features and popularity.

Literature review

Theoretical foundation

The cognitive appraisal theory may provide insights into an individual's perception on the environment, the reaction of emotional state as well as his/her subsequent behaviors. To explain further, emotions are thought to be rooted in the evaluation of stimuli of an experience (Peng & Kim, Citation2014). According to Lazarus (Citation1991), a person's emotional responses to a situation are directly tied to his/ her personal interpretation of the situation as it unfolds. Hence, when applied to a tourism product such as festival participation, visitors are likely to interpret the same stimulus experience differently, resulting in distinctive emotional responses (Chi et al., Citation2021). Similar to other tourism products, festival participation possesses a combination of tangible and intangible attributes in which festival participants would ascribe meaning or develop connections with through the emotions elicited towards their immediate environment (Armbrecht & Andersson, Citation2020). As visitors’ service encounters with a festival evoke emotions through cognitive appraisal stimuli, it is crucial for event organizers to identify the unique characteristics of festival experience that can elicit positive emotions (Nguyen et al., Citation2020). Once the service providers distinguish their offerings and positive emotions are achieved among consumers, consumers would go beyond purchase transactions (Choi & Park, Citation2020). For example, tourists who develop a high level of positive emotional response may be engage in positive behaviors including revisiting, buying souvenirs or sharing experiences through social media in order to make their experience tangible (Kim & Hall, Citation2022; Loi et al., Citation2017; Tolls & Carr, Citation2021). It is also evident that the cognitive appraisals approach is appropriate in capturing the subtle nuances of emotions, thereby allowing better understanding on how emotions can affect consumption related behaviors (Krause et al., Citation2019). Drawing references from Kim and Thapa (Citation2018), the flow experience can be considered as an emotional state, which would, in turn, affect visitors’ behavioral responses including satisfaction and revisit intention. summarizes the conceptual model of this study.

Figure 1. Conceptual model.

Antecedents of flow experience

Flow experience can be described as an individual's psychological state when he/ she is fully engaged in an activity, ignoring the existence of other things as well as feeling pleasure and content (Kim & Thapa, Citation2018). The concept of flow was first coined by Csikszentmihalyi (Citation1991) that discovered individuals experienced enjoyment and got carried by a current like a river flows when performing activities that they preferred. Since flow experience corresponds to an optimal physiological state, the concept has been widely regarded as a key element to achieve optimal experience (Amatulli et al., Citation2021). To understand how flow experience can be achieved, Fu et al. (Citation2017) posit that flow experience may be in relation to self-congruity, as an optimal experience is likely to be obtained when there is a parallel between visitors’ self-concept and the festival personality. This is in line with scholars’ definition explaining flow experience as a unified flowing from one moment to the next, in which we feel in control of our actions, and in which there is little distinction between self and environment; between stimulus and response; or between past, present, and future (deMatos et al., Citation2021; Ding & Hung, Citation2021). Recognizing the importance of eliciting positive experience when consuming tourism products, scholars have studied tourists’ flow experience in different tourism scenarios such as participating in VR tourism (Huang et al., Citation2021), nature-based tourism (Kim & Thapa, Citation2018), golf tourism (Swann et al., Citation2015), adventure tourism (Wu & Liang, Citation2011), art performance tourism (Zhang et al., Citation2021) as well as festival participation (Ding & Hung, Citation2021). Although the application of the concept of flow experience to the tourism context is promising and the research interest is evident, the connection between flow and tourists’ experience in a music festival remain understudied (deMatos et al., Citation2021). To the best of the authors’ knowledge, Ding and Hung (Citation2021) is the only study that empirically studied festival attendees’ flow experience. Following Ding and Hung (Citation2021), there are five antecedents of music festival attendees’ flow experience: skill performance, ambience, self-congruence, other consumers’ passion, consumer-to consumer interaction.

Skill performance. Skill performance has been more commonly studied in the context of sports events in which it investigates spectators’ perception of athletes’ performance quality in sporting activities (Ko et al., Citation2021). Previous studies such as Armbrecht and Andersson (Citation2020) also noted that athletes’ skill performance was associated with the spectators’ immersive experience, excitement and positive emotional experience. Hence, in this study, skill performance can be defined as festival attendees’ perception towards the quality of the performance of singers/ bands in the music festival. Along the same line, the performance of the music festival will likely shape consumers’ experience given that in service consumption involving performances and music, visitors see the performance of the related shows as the core service component (Uhrich & Benkenstein, Citation2012). In other words, the need to enjoy a music performance can be seen as a motivator to people attending a music festival, hence making it an important element that shapes visitors’ experience (Vinnicombe & Sou, Citation2017). Following this rationale, when music festival attendees evaluate the performance favorably, they are more likely to have fun and gain a positive emotional experience, which would ultimately result in flow (Ding & Hung, Citation2021). Based on the above discussion, it is hypothesized that:

H1a: Skill performance has a positive influence on festival attendees’ flow experience.

H1b: Ambience has a positive influence on festival attendees’ flow experience.

H1c: Self-congruity has a positive influence on festival attendees’ flow experience.

H1d: Other consumers’ passion has a positive influence on festival attendees’ flow experience.

H1e: Consumer-to-consumer interaction has a positive influence on festival attendees’ flow experience.

Flow experience and festival satisfaction

As highlighted earlier, the experience of flow is related to satisfaction as an uninterrupted flow of action and awareness tends to lead to pleasant experience (Huang et al., Citation2021). When a person is experiencing flow, it means that he or she is emotionally charged with a sense of energized focus and enjoyment. Such emotion is characterized by a loss of self-consciousness and a deep sense of satisfaction and fulfillment. Naturally, a continuous flow of experience can lead to positive evaluation of the activity or satisfaction (deMatos et al., Citation2021). Research on the relationship between flow experience and satisfaction has been confirmed in different tourism settings, such as cultural heritage tourism (Liu et al., Citation2022), smart tourism (Zhang & Abd Rahman, Citation2022), adventure tourism (Amatulli et al., Citation2021), virtual tourism (Huang et al., Citation2021), and eco-tourism (Kim & Thapa, Citation2018). These papers generate a common conclusion that experiencing flow can be a highly positive and rewarding state of consciousness, both in terms of the enjoyment and satisfaction it brings, as well as the potential benefits it can have for personal and professional success. Based on the above arguments, it is speculated that a similar phenomenon may be expected in the context of festival tourism. Accordingly, it is hypothesized that:

H2: Flow experience has a positive influence on festival attendees’ festival satisfaction.

Flow experience and revisit intention

Apart from eliciting positive emotions (such as feeling joyful and satisfied), flow experience also has a significant impact on an individual's behavioral desire or actual behavior (Zhang & Abd Rahman, Citation2022). Being in the state of flow and obtaining a high level of gratification from an experience is likely to lead an individual to grow an inclination to repeat the conduct (Wu & Liang, Citation2011). Such behavior can be explained from the perspective that when individuals experience flow during an activity, they feel a strong sense of enjoyment and satisfaction, where they feel that their time and effort were well-spent, leading to revisitation intention (Amatulli et al., Citation2021). While not much has been studied in the festival tourism context, earlier arguments offer insights that when participants who are in the state of flow (immersing themselves in the activities and feeling pleasure) they may also gravitate towards revisit intention. Based on the discussion, it is hypothesized that:

H3: Flow experience has a positive influence on festival attendees’ revisit intention.

Festival satisfaction and revisit intention

An individual's satisfaction level may have a critical influence on the decision to repurchase a product or revisit to a certain place. In the consumer decision-making process, consumers tend to evaluate the viability of different alternative products or services based on past purchasing and consumption experience (Zhong et al., Citation2022). If the consumers were satisfied with their last purchase, the past reinforcement in learning experiences can then lead to repurchasing the same products/ services (Liu & Tang, Citation2018). It has also been found that the quality of a consumption experience positively affects consumers’ intention to repurchase while a pleasurable experience is connected to their continuous support (Liang & Shiau, Citation2018; Wen et al., Citation2011). Along the same line of arguments, numerous tourism and hospitality studies also support the fact that tourists’ satisfaction is directly related to revisit intention (Huang et al., Citation2015; Wang & Wu, Citation2011). Based on these arguments, it is natural that we expect a participant’s festival satisfaction would have a positive influence on their revisiting intention.

H4: Festival satisfaction has a positive influence on festival attendees’ revisit intention.

Festival satisfaction as a potential mediator

The discussion above further evidenced that festival satisfaction is more than just an outcome of a service experience; it is also an indicator of consumers’ behavioral intention. We believe that festival satisfaction may mediate the relations between festival attendees’ flow experience and revisit intention. To support this claim, it can be said that when individuals experience the state of flow, they eliminate all extraneous thoughts and feel content and joyful. As a result, this positive experience can enhance their motivation to participate in the same activity again in the future (Ding & Hung, Citation2021). The mediating role of customer satisfaction is further confirmed in different tourism and hospitality works, such as the relations between perceived value and revisit intention in Yogyakarta (Thipsingh et al., Citation2022); between service quality and revisit intention in the KTV context (Khoo, Citation2022); between destination image and intention to revisit Macao (Loi et al., Citation2017); between image congruence and intention to revisit in marathon tourism (Huang et al., Citation2015); and between brand attitude and revisit intention to coffee chain stores (Ko & Chiu, Citation2008). Putting these arguments together, the next hypothesis is:

H5: Festival satisfaction mediates the relationship between festival attendees’ flow experience and revisit intention.

Fear of missing out (FOMO) as a potential moderator

With the advent of social media, the fear of missing out (FOMO) may play a role in affecting the strength of relationships. FOMO is characterized by the “desire to stay continually connected with what others are doing.” (Przybylski et al., Citation2013, p. 1841). In sum, FOMO would motivate an individual to act accordingly so he/she could stay in touch with the social environment in order not to miss out on anything, and eventually addressing emotions of fear, anxiety, depression, and loneliness (Duman & Ozkara, Citation2021; Hayran et al., Citation2020)

Accordingly, festival participation may be a context where FOMO can affect an individual's behavioral intentions as events can facilitate social connectedness and in-group formation (Kim, Lee, et al., Citation2020). As such, it is not unreasonable to argue that missing out on a festival in town could trigger concerns of not being part of a society, thereby resulting in FOMO. In the present study, despite having a decent flow experience and being satisfied with the festival participation, the intention to revisit may not be necessarily the outcome as performing a leisure behavior requires one to overcome intrapersonal (attributes related to oneself or mind, e.g. lack of interest), interpersonal (related to relations with others, e.g. lack of acquaintance) and structural (related to situations, e.g. insufficient financial resource) constraints (Samdahl & Jekubovich, Citation1997). Hodkinson (Citation2019, p. 66) has mentioned that FOMO is a key component that “calls on consumers to directly address their internal hesitancy, or resistance, to assent to an action.” FOMO can, therefore, be viewed as a motive to stimulate one's behavioral intention as it facilitates the overcoming of the intrapersonal and structural constraints (Kim, Lee, et al., Citation2020). Applying this to the present context, it is speculated that for festival participants reporting high FOMO, the indirect effect of flow experience on revisit intention will be higher than those with low FOMO. As far as we are concerned, no existing study has empirically examined the moderating role of FOMO concerning revisiting the festival, indicating an unaddressed research gap. Hence, it is hypothesized that:

H6: FOMO MCMF moderates the mediating relationship among festival attendees’ flow experience, revisit intention and festival satisfaction.

Methodology

Sampling and data collection

We conducted the data collection onsite at the 2022 MCMF, which took place on November 25–26, 2022. The study was conducted by a research team consisting of two groups, with ten undergraduate and postgraduate students in each group. Before collecting data, the study investigators briefed the researchers on the expected research integrity standards. Furthermore, each day of data collection started with a short briefing session reminding the field researchers of what they should and should not be doing. During the data collection period, study investigators were present on-site to address questions related to the study protocol and help with any queries from the participants. Convenience sampling was used since the population of festival participants was unknown. The field researchers were stationed at various locations within the festival area and approached participants to explain the purpose of the study and request their consent. The participants were then given the survey form to complete independently or with guidance from the researchers. A total of 317 survey forms were completed.

Following Cohen’s (Citation1988) suggestion, the G*power analysis with 80% power, a 15% effect size with five predictors revealed that the recommended number of respondents is 98. With 317 valid responses, the study has a 99.99% power, indicating that the analysis can be conducted. The power analytic method is considered a more robust technique because it can determine if a study has insufficient or excessive power. This method is also useful for determining sample sizes for an unknown population, which applies to this study. Additionally, the total number of respondents exceeded Kock's (Citation2018) recommended minimum sample size of 160. provides a summary of the respondents’ profile.

Table 1. Respondents profile.

Instrument

All constructs were measured with items that have been tested in previous studies. The constructs for skill performance (3 items), ambience (3 items), self-congruence (4 items), other consumers’ passion (3 items), consumer-to-consumer interaction (3 items) and flow experience (3 items) are adapted from Ding and Hung (Citation2021). Items for revisiting intention (4 items) and festival satisfaction (4 items) are adapted from Tan, Sim, Chai, et al. (Citation2020). Finally, FOMO (6 items) is adapted from Kim, Lee, et al. (Citation2020). All items are measured on a five-point Likert scale. provides the details of the items.

Table 2. Measurement model.

Analytical method

The study employs the partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) to analyze the data, which is deemed more suitable for information science and social science studies as the constructs tend to form a composite measurement model (Hair et al., Citation2017). PLS-SEM also allows for formatively specified measurement models that can be estimated without restrictions and permits the modeling of constructs at different levels of abstraction simultaneously. Furthermore, PLS-SEM is a useful and efficient approach when the aim is to explain and predict outcomes (Hair et al., Citation2017). An advantage of PLS-SEM is that it does not make assumptions about the distribution of the data, and it has been widely used in various fields, including human resources (Tan, Sim, Goh, et al., Citation2020), tourism (Tan et al., Citation2023), education (Sim et al., Citation2020), technology adoption (Leong et al., Citation2021) and consumer behavior (Le et al., Citation2022).

Results

Common method variance

To prevent any potential bias in the results caused by common method variance (CMV), this study, which is cross-sectional, takes steps to control it. The approach used to control CMV is based on the recommendations of Podsakoff et al. (Citation2003). First, the study introduces temporal separation by including demographic questions between the predictor and criterion variables. Second, the survey was pretested by sending it to tourism researchers to eliminate any ambiguity in the wording or unclear instructions. Third, throughout the data collection process, the participants were repeatedly assured of their anonymity and encouraged to provide honest answers. Finally, Harman's one-factor test was conducted, which showed that the largest factor explained only 44.39% of the variance, which is below the threshold value of 50% suggested by Podsakoff et al. (Citation2003). This finding suggests that CMV is not a significant concern for this study.

Measurement model

The first step, in accordance with Hair et al. (Citation2017), is to test the measurement model. Following Hair et al. (Citation2017) and Ramayah et al. (Citation2018), all items have a loading of 0.7 or higher, indicating that indicator reliability is established (refer to ). Furthermore, we can confirm that the model has achieved both convergent validity and internal reliability, as the Cronbach’s alpha score, average variance extracted and composite reliability values exceed the cutoff values of 0.7, 0.5 and 0.7, respectively (refer to ). Using the heterotrait-monotrait (HTMT) ratio of correlations, as demonstrated in , it is established that discriminant validity has been achieved, as the HTMT values are less than 0.85 (Henseler et al., Citation2015).

Table 3. Discriminant validity.

Structural model

Prior to assessing the structural model, we first examine the variance inflation factor (VIF) for possible multicollinearity. As demonstrated in , the VIF scores are less than 3.3 demonstrating that multicollinearity is not a serious consideration in this model (Hair et al., Citation2017). Thereafter, we proceed with the analysis using bootstrapping resampling procedures of 5,000 iterations. shows that among the different antecedents, only ambience (H1b: β = 0.136, p < 0.05), self-congruity (H1c: β = 0.384, p < 0.001) and customer-to-customer interaction (H1e: β = 0.157, p < 0.05) have a significant positive effect on flow experience, but not skill performance (H1a: β = 0.079, p = 0.156) and other consumers’ passion (H1d: β = 0.104, p < 0.090). Hence, only H1b, H1c and H1e are supported. Additionally, flow experiences are found to significantly influence festival satisfaction (H2: β = 0.493, p < 0.001) and revisit intention (H3: β = 0.188, p < 0.001). At the same time, festival satisfaction has a significant positive effect on revisit intention (H4: β = 0.709, p < 0.001). Owing to the results in H2, H3, and H4, it is expected festival satisfaction partially mediates the relationship between flow experience and revisit intention (H5: β = 0.350, p < 0.001). In sum, H2 to H5 are all supported.

Table 4. Structural model.

Regarding the role of FOMO as a moderator on the mediated relationship, this study based on the recommendations of Cheah et al. (Citation2021). Traditionally, obtaining results of a moderated-mediation relationships can be done using a PROCESS macro. However, Sarstedt et al. (Citation2020) has highlighted that such combination is not desirable, with them further stressing that the simultaneous estimations in a nomological network, in contrast to conducting a supplementary regression analysis, are necessary to produce reliable and valid results, especially in the case of multi-item construct measurements. Hence, the sole use of PLS-SEM for estimating a conditional mediation (CoMe) model offers several benefits of (1) overcoming the limitations of conventional sequential approaches by allowing researchers to analyze complex interrelationships among latent variables simultaneously, and (2) taking into account the inherent measurement error present in multi-item measurements (Cheah et al., Citation2021). In this regard, the initial step is to establish whether a mediating relationship exists, which demonstrated that there is a significant indirect relationship from flow experience to revisit intention, through festival satisfaction. Following that, we would develop the CoMe index which our results in indicates that the CoMe index of FOMO for moderated mediation effect is significant (index = 0.040, p < 0.01). According to Cheah et al. (Citation2021), this indicates that the mediated effect of flow experience on revisit intention through festival satisfaction indeed depends on FOMO. The results also revealed that at higher level of FOMO, the indirect effect of flow experience on revisit intention through festival satisfaction (β = 0.337, p < 0.001) is higher comparing to the indirect effect at lower FOMO (β = 0.285, p < 0.001), showing that with increase in FOMO, the indirect effect is increased. Hence, H6 is supported.

Table 5. Moderated mediation results.

Falling back to , PLS-SEM also provides information of the model’s explanatory power by examining all the endogenous variables’ via measures such as R2 and f2. In this regard, the R2 of the various endogenous constructs ranges from 0.243 to 0.670, indicating a moderate to substantial model. On the effect sizes (f2), we would consider effect size of festival experience on revisit intention as being large (f2 = 1.154), while the effect size of flow experience on revisit intention as being small (f2 = 0.081). In the same vein, flow experience exhibit a medium effect on festival satisfaction at f2 = 0.322. Finally, the various antecedents to flow experience exhibits small to medium effect sizes that ranges from 0.005 to 0.167.

Discussion

Our findings suggest that certain factors are necessary for flow experience to occur, namely ambience, self-congruity, and customer-to-customer interactions. In a music festival setting, the ambiance is crucial in creating an immersive environment that engages all the senses, thus allowing participants to be fully present in the moment. This can include elements such as lighting, decorations, stage design, and the overall atmosphere, which work together to create a cohesive and engaging experience. Such an immersive environment can lead to a state of flow characterized by deep concentration, a loss of self-awareness, and a feeling of being fully absorbed in the present moment (Ding & Hung, Citation2021; Tan, Sim, Chai, et al., Citation2020).

Self-congruity also plays a significant role in facilitating flow experience, as it provides a sense of belonging and identification with the festival and its culture. This psychological harmony and coherence encourage engagement and immersion in the festival experience. Moreover, customer-to-customer interactions increase participants’ sense of shared experience and unity, leading to greater enjoyment of the event (Ding & Hung, Citation2021). Flow is characterized by a state of mind where individuals are fully engaged and immersed in the festival experience. This emotional state is characterized by intense focus, a sense of control, and a loss of self-awareness (deMatos et al., Citation2021; Zhao et al., Citation2021). Our study found that flow experience leads to increased satisfaction and revisit intention to music festivals, a finding supported by previous studies (see deMatos et al., Citation2021; Ding & Hung, Citation2021; Zhao et al., Citation2021). Memorable and positive festival experiences can leave lasting impressions on individuals, leading them to revisit the event in the future.

Additionally, our results indicate that FOMO strengthens the relationship between flow and revisit intention. FOMO is a social anxiety that arises from the fear of missing out on enjoyable experiences that others are participating in. When individuals fear missing out on future events at the same festival, they may feel motivated to attend the next festival to avoid missing out. In summary, our study highlights the importance of certain factors in facilitating flow experience and how it relates to satisfaction and revisit intention to music festivals.

Implications

Theoretical implications

In various ways, this research adds to the existing literature. Firstly, numerous studies have examined and assessed the economic effects produced by holding events in various regions. However, not much research has focused on the antecedents to flow experience, and how this translates to revisit intention. Thus, this study enhances the existing knowledge by proposing a conceptual model to gain a better comprehension from the insights of the participants. Secondly, our study has addressed another research gap by demonstrating that FOMO is a crucial construct showing that FOMO is an essential factor that influences the likelihood of revisiting a music festival. The study found that by participating in a music festival, individuals can experience FOMO, which can motivate them to attend the event again in the future. This contribution is especially crucial since there is a lack of literature in this area (Kim, Lee, et al., Citation2020). Seen from this light, our work contributes to the growing academic literature on FOMO by suggesting novel behavioral consequences. For one, many of the previous studies mostly focused on investigating FOMO as a trait variable (Hayran et al., Citation2020).

We took a different approach by examining FOMO as a momentary feeling that arises from attending a music festival. This approach enables us to investigate FOMO in a wider population and determine how it influences decisions and behaviors in different situations. Second, we have also provided a different appreciation of the role of FOMO. In much of the existing literature such as Hayran et al. (Citation2020), FOMO has always been operationalized as knowledge of another event, which is seen as a distraction to existing ones. However, we repositioned FOMO as fearing to miss out the same event as they are attending, and because of this, it can be leveraged as a form of resource for event organizers. By narrowing the scope of FOMO on a specific event that others are attending, we are focusing on a more specific context. This reframing suggests that individuals may experience anxiety or fear specifically when they are aware of an event and know that others are participating in it, but they are unable to join for some reason. Differentiating this reconceptualization from the traditional definition of FOMO highlights the contextual specificity of the fear. It suggests that the fear is not just about missing out on any experience but about missing out on a particular event that others are actively engaged in. This narrower definition may help individuals understand and address their feelings more specifically in relation to a particular event or occasion.

Managerial implications

Our studies have important implications for managers. Event organizers, particularly those organizing music festivals like MCMF, can leverage FOMO as a strategy to increase attendee engagement and repeat behavior. By creating a sense of urgency and scarcity through social media platforms, organizers can offer time-limited discounts or exclusive offers to create the fear of missing out. Additionally, user-generated content such as reviews and testimonials can be utilized to provide social proof and encourage conversions. Strategic use of social media can amplify the FOMO effect and drive attendance and participation.

Considering that flow experience is essential in creating festival satisfaction and revisit intention, MCMF organizers can consider developing targeted marketing strategies to emphasize the fit between the event and the attendee's self-concept. This can be achieved by using language, visuals, and messages that are consistent with the target audience's self-image. At the same time, MCMF organizers can create a more personalized participants’ experience by offering products and services that align with the customer's self-concept. For example, the MCMF organizers can offer country tour programs to further support their affiliation to country music. Similarly, the ambience must complement the theme of the music festival. For the case of MCMF, organizers should plan for ambience as part of the overall festival planning process. This could include considering factors such as lighting, sound, and decor, as well as the placement of different stages and areas within the festival grounds. Music festivals are an excellent opportunity for people to meet and socialize with others who share similar interests. MCMF organizers can facilitate this by providing designated areas for people to congregate and mingle, such as lounge areas or community spaces. By implementing these managerial implications, MCMF organizers can effectively engage attendees, enhance their festival experience, and cultivate revisit intention, leading to long-term success and sustainability of the music festival.

Limitations and future research

The study presented in the article has certain limitations. Firstly, the research was carried out in a single festival in Malaysia, and therefore, the results should be viewed within the context of the limited sample population. The authors suggest that future research should expand on this by validating their findings in other nations that host festivals and comparing them with samples outside Malaysia. Future research should aim to replicate this model across various music festivals in different countries.

Secondly, the data collection method relied on a single source, which could be subject to common method bias (CMB) and socially desirable answers. Although statistical remedies indicated that CMB was not a significant threat, researchers should still consider using multi-source data or performing a longitudinal study in future studies.

Thirdly, the study utilized a moderated mediation model to understand the interrelationship of different constructs, including festival satisfaction as a mediator and FOMO as a moderator. However, the model could be improved by exploring other theoretical mediators and moderators such as use of AI, quality of life, as well as other non-economic tourism benefits.

The task of collecting survey responses from visitors during the event was difficult due to their enjoyment of the performances. The researchers were only able to gather data when the visitors were eating, drinking, or engaging in conversations. Consequently, the study could only obtain responses from a small percentage of the international tourists attending the event. To address this issue, future research could potentially send out survey forms to attendees who have registered their email addresses before the event.

Conclusion

In conclusion, event tourism has become an important area of research, particularly with respect to music festivals due to their ability to attract tourists to hosting destinations, create employment opportunities, and build a positive image for the destination. However, there are still research gaps that need to be addressed, such as the management, operation, and governance of festivals, visitors’ flow experience and FOMO, limited understanding of festival tourism in different countries, and the impact of the pandemic on event tourism. The present study aims to address some of these gaps by exploring the antecedents of festival attendees’ flow experience, their satisfaction and revisit intention in the post-pandemic era in Malaysia. The study proposes a moderated mediation model to understand the interrelationship of different constructs, including FOMO as a moderator. The findings from this study can provide insights to event organizers and tourism stakeholders in managing and promoting festival tourism in Malaysia and other developing countries.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by Curtin University Human Research Ethics Office (HRE2022-0550).

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Al Rousan, R., Khasawneh, N., Sujood, S., & Bano, N. (2023). Post-pandemic intention to participate in the tourism and hospitality (T&H) events: An integrated investigation through the lens of the theory of planned behavior and perception of Covid-19. International Journal of Event and Festival Management, 14, 237–258. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijefm-04-2022-0036

- Amatulli, C., Peluso, A. M., Sestino, A., Petruzzellis, L., & Guido, G. (2021). The role of psychological flow in adventure tourism: Sociodemographic antecedents and consequences on word-of-mouth and life satisfaction. Journal of Sport & Tourism, 25(4), 353–369. https://doi.org/10.1080/14775085.2021.1994448

- Armbrecht, J., & Andersson, T. D. (2020). The event experience, hedonic and eudaimonic satisfaction and subjective well-being among sport event participants. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, 12, 457–477. https://doi.org/10.1080/19407963.2019.1695346

- Aubert-Gamet, V. (1997). Twisting servicescapes: Diversion of the physical environment in a re-appropriation process. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 8(1), 26–41. https://doi.org/10.1108/09564239710161060

- BBC. (2018). Music festivals: What's the world's biggest? Retrieved July 27, from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-44697302

- Cheah, J.-H., Nitzl, C., Roldán, J. L., Cepeda-Carrion, G., & Gudergan, S. P. (2021). A primer on the conditional mediation analysis in PLS-SEM. ACM SIGMIS Database: The DATABASE for Advances in Information Systems, 52(SI), 43–100. https://doi.org/10.1145/3505639.3505645

- Chen, Y., & Lei, W. S. (2021). Behavioral study of social media followers of a music event: A case study of a Chinese music festival. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights, 4(2), 163–182. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHTI-09-2020-0168

- Chi, X., Cai, G., & Han, H. (2021). Festival travellers’ pro-social and protective behaviours against COVID-19 in the time of pandemic. Current Issues in Tourism, 24(22), 3256–3270. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2021.1908968

- Choi, Y.-J., & Park, J.-W. (2020). Investigating factors influencing the behavioral intention of online duty-free shop users. Sustainability, 12(17), 7108. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12177108

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Confente, I., Scarpi, D., & Russo, I. (2020). Marketing a new generation of bio-plastics products for a circular economy: The role of green self-identity, self-congruity, and perceived value. Journal of Business Research, 112, 431–439. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.10.030

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1991). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience (1st. Harper Perennial ed.). Harper Collins.

- deMatos, N. M. d. S., Sá, E. S. d., & Duarte, P. A. d. O. (2021). A review and extension of the flow experience concept. Insights and directions for Tourism research. Tourism Management Perspectives, 38, 100802. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2021.100802

- Ding, H.-M., & Hung, K.-P. (2021). The antecedents of visitors’ flow experience and its influence on memory and behavioral intentions in the music festival context. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 19, 100551. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2020.100551

- D’souza, D. J., Harisha, G., & Raghavendra, P. (2021). Assessment of consumers acceptance of E-commerce to purchase geographical indication based crop using technology acceptance model (TAM). AGRIS On-line Papers in Economics and Informatics, 13(3), 25–33. https://doi.org/10.7160/aol.2021.130303

- Duman, H., & Ozkara, B. Y. (2021). The impact of social identity on online game addiction: The mediating role of the fear of missing out (FoMO) and the moderating role of the need to belong. Current Psychology, 40(9), 4571–4580. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00392-w

- Fu, X., Kang, J., & Tasci, A. (2017). Self-congruity and flow as antecedents of attitude and loyalty towards a theme park brand. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 34(9), 1261–1273. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2017.1343704

- Getz, D., & Page, S. J. (2016). Progress and prospects for event tourism research. Tourism Management, 52, 593–631. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2015.03.007

- Gilstrap, C., Teggart, A., Cabodi, K., Hills, J., & Price, S. (2021). Social music festival brandscapes: A lexical analysis of music festival social conversations. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 20, 100567. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2021.100567

- Gupta, S., & Priyanka, P. (2022). Gamification and e-learning adoption: A sequential mediation analysis of flow and engagement. VINE Journal of Information and Knowledge Management Systems, https://doi.org/10.1108/vjikms-04-2022-0131

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (2nd ed.). Sage Publications Ltd.

- Hayran, C., Anik, L., & Gurhan-Canli, Z. (2020). A threat to loyalty: Fear of missing out (FOMO) leads to reluctance to repeat current experiences. PLoS ONE, 15(4), e0232318. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0232318

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

- Ho, J. M., Tiew, F., & Adamu, A. A. (2022). The determinants of festival participants’ event loyalty: A focus on millennial participants. International Journal of Event and Festival Management, 13(4), 422–439. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEFM-01-2022-0006

- Hodkinson, C. (2019). ‘Fear of missing out’ (FOMO) marketing appeals: A conceptual model. Journal of Marketing Communications, 25(1), 65–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527266.2016.1234504

- Huang, H., Mao, L., Wang, J., & Zhang, J. J. (2015). Assessing the relationships between image congruence, tourist satisfaction and intention to revisit in marathon tourism: The Shanghai International Marathon. International Journal of Sports Marketing and Sponsorship, 16(4), 46–66. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSMS-16-04-2015-B005

- Huang, X., Liu, C., Liu, C., Wei, Z., & Y. Leung, X. (2021). How children experience virtual reality travel: A psycho-physiological study based on flow theory. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Technology, 12(4), 777–790. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHTT-07-2020-0186

- Jamshidi, D., Keshavarz, Y., Kazemi, F., & Mohammadian, M. (2018). Mobile banking behavior and flow experience. International Journal of Social Economics, 45(1), 57–81. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSE-10-2016-0283

- Khoo, K. L. (2022). A study of service quality, corporate image, customer satisfaction, revisit intention and word-of-mouth: Evidence from the KTV industry. PSU Research Review, 6(2), 105–119. https://doi.org/10.1108/PRR-08-2019-0029

- Kim, J., Lee, Y., & Kim, M.-L. (2020). Investigating ‘fear of missing out’ (FOMO) as an extrinsic motive affecting sport event consumer's behavioral intention and FOMO-driven consumption's influence on intrinsic rewards, extrinsic rewards, and consumer satisfaction. PLoS ONE, 15(12), e0243744. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0243744

- Kim, K., Byon, K. K., & Baek, W. (2020). Customer-to-customer value co-creation and co-destruction in sporting events. The Service Industries Journal, 40(9), 633–655. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069.2019.1586887

- Kim, M., & Thapa, B. (2018). Perceived value and flow experience: Application in a nature-based tourism context. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 8, 373–384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2017.08.002

- Kim, M. J., & Hall, C. M. (2022). Do smart apps encourage tourists to walk and cycle? Comparing heavy versus non-heavy users of smart apps. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 27(7), 763–779. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2022.2119423

- Ko, W.-H., & Chiu, C. P. (2008). The relationships between brand attitude, customers’ satisfaction and revisiting intentions of the university students–a case study of coffee chain stores in Taiwan. Journal of Foodservice Business Research, 11(1), 79–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/15378020801926791

- Ko, Y. J., Kwon, H. H., Kim, T., Park, C., & Song, K. (2021). Assessment of event quality in major spectator sports: Single-item measures. Journal of Global Sport Management, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/24704067.2021.2001353

- Kock, N. (2018). Minimum sample size estimation in PLS-SEM: An application in tourism and hospitality research. In A. Faizan, S. M. Rasoolimanesh, & C. Cihan (Eds.), Applying partial least squares in tourism and hospitality research (pp. 1–16). Emerald Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/978-1-78756-699-620181001

- Krause, A. E., North, A. C., & Davidson, J. W. (2019). Using self-determination theory to examine musical participation and well-being. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 405. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00405

- Laing, J. (2018). Festival and event tourism research: Current and future perspectives. Tourism Management Perspectives, 25, 165–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2017.11.024

- Latané, B. (1981). The psychology of social impact. American Psychologist, 36(4), 343–356. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.36.4.343

- Lazarus, R. S. (1991). Progress on a cognitive-motivational-relational theory of emotion. American Psychologist, 46(8), 819–834. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.46.8.819

- Le, A., Tan, K.-L., Yong, S.-S., Soonsap, P., Lipa, C. J., & Ting, H. (2022). Perceptions towards green image of trendy coffee cafés and intention to re-patronage: The mediating role of customer citizenship behavior. Young Consumers, 23(2), 165–178. https://doi.org/10.1108/YC-03-2021-1291

- Lee, J., & Kyle, G. T. (2014). Segmenting festival visitors using psychological commitment. Journal of Travel Research, 53(5), 656–669. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287513513168

- Lee, Y.-K., Lee, C.-K., Lee, W., & Ahmad, M. S. (2021). Do hedonic and utilitarian values increase pro-environmental behavior and support for festivals? Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 26(8), 921–934. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2021.1927122

- Leong, C.-M., Tan, K.-L., Puah, C.-H., & Chong, S.-M. (2021). Predicting mobile network operators users m-payment intention. European Business Review, 33(1), 104–126. https://doi.org/10.1108/ebr-10-2019-0263

- Li, X., Kim, J. S., & Lee, T. J. (2021). Contribution of supportive local communities to sustainable event tourism. Sustainability, 13(14), 7853. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147853

- Liang, C.-C., & Shiau, W.-L. (2018). Moderating effect of privacy concerns and subjective norms between satisfaction and repurchase of airline e-ticket through airline-ticket vendors. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 23(12), 1142–1159. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2018.1528290

- Lin, J. S. C., Fisk, R. P., & Liang, H. Y. (2011). The influence of service environments on customer emotion and service outcomes. Managing Service Quality: An International Journal, 21(4), 350–372. https://doi.org/10.1108/09604521111146243

- Liu, H., Chu, H., Huang, Q., & Chen, X. (2016). Enhancing the flow experience of consumers in China through interpersonal interaction in social commerce. Computers in Human Behavior, 58, 306–314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.01.012

- Liu, H., Park, K.-S., & Wei, Y. (2022). An extended stimulus-organism-response model of Hanfu experience in cultural heritage tourism. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 135676672211351. https://doi.org/10.1177/13567667221135197

- Liu, Y., & Tang, X. (2018). The effects of online trust-building mechanisms on trust and repurchase intentions. Information Technology & People, 31(3), 666–687. https://doi.org/10.1108/ITP-10-2016-0242

- Loi, L. T. I., So, A. S. I., Lo, I. S., & Fong, L. H. N. (2017). Does the quality of tourist shuttles influence revisit intention through destination image and satisfaction? The case of Macao. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 32, 115–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2017.06.002

- MATTA. (2021). Four key tourism and travel players join hands towards industry preparedness and reopening of tourism and business event. Retrieved April 1, from www.matta.org.my

- Nguyen, T., Lee, K., Chung, N., & Koo, C. (2020). The way of generation Y enjoying Jazz festival: A case of the Korea (Jarasum) music festival. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 25(1), 52–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2019.1580755

- Özdipçiner, N. S., Aktaş, E., & Ceylan, S. (2020). A comprehensive review of the development of event tourism impact studies over the years. In D. Gursoy, R. Nunkoo, & M. Yolal (Eds.), Festival and event tourism impacts (pp. 3–17). Routledge.

- Peng, C., & Kim, Y. G. (2014). Application of the stimuli-organism-response (S-O-R) framework to online shopping behavior. Journal of Internet Commerce, 13(3-4), 159–176. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332861.2014.944437

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

- Przybylski, A. K., Murayama, K., DeHaan, C. R., & Gladwell, V. (2013). Motivational, emotional, and behavioral correlates of fear of missing out. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(4), 1841–1848. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.02.014

- Ramayah, T., Cheah, J. H., Chuan, F., Ting, H., & Memon, A. M. (2018). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) using SmartPLS 3.0: An updated and practical guide to statistical analysis (2nd ed.). Pearson Limited.

- Samdahl, D. M., & Jekubovich, N. J. (1997). A critique of leisure constraints: Comparative analyses and understandings. Journal of Leisure Research, 29(4), 430–452. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222216.1997.11949807

- Sarstedt, M., Hair, J. F., Nitzl, C., Ringle, C. M., & Howard, M. C. (2020). Beyond a tandem analysis of SEM and PROCESS: Use of PLS-SEM for mediation analyses!. International Journal of Market Research, 62, 288–299. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470785320915686

- Šegota, T., Chen, N., & Golja, T. (2022). The impact of self-congruity and evaluation of the place on WOM: Perspectives of tourism destination residents. Journal of Travel Research, 61(4), 800–817. https://doi.org/10.1177/00472875211008237

- Sia, J. K. M., Lew, T. Y., & Sim, A. K. S. (2015). Miri city as a festival destination image in the context of Miri country music festival. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 172, 68–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.01.337

- Silva, R., Rodrigues, R., & Leal, C. (2019). Play it again: How game-based learning improves flow in Accounting and Marketing education. Accounting Education, 28(5), 484–507. https://doi.org/10.1080/09639284.2019.1647859

- Sim, A. K. S., Tan, K.-L., Sia, J. K.-M., & Hii, I. S. H. (2020). Students’ choice of international branch campus in Malaysia: A gender comparative study. International Journal of Educational Management, 35(1), 87–107. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEM-01-2020-0027

- Sirgy, M. J., & Su, C. (2000). Destination image, self-congruity, and travel behavior: Toward an integrative model. Journal of Travel Research, 38(4), 340–352. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728750003800402

- Swann, C., Crust, L., Keegan, R., Piggott, D., & Hemmings, B. (2015). An inductive exploration into the flow experiences of European Tour golfers. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 7(2), 210–234. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2014.926969

- Tan, K.-L., Hii, I. S. H., Zhu, W., Leong, C.-M., & Lin, E. (2023). The borders are re-opening! Has virtual reality been a friend or a foe to the tourism industry so far? Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 35(7), 1639–1662. https://doi.org/10.1108/APJML-05-2022-0417

- Tan, K.-L., Sim, A. K. S., Chai, D., & Beck, L. (2020). Participant well-being and local festivals: The case of the Miri country music festival, Malaysia. International Journal of Event and Festival Management, 11(4), 433–451. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEFM-02-2020-0007

- Tan, K.-L., Sim, P.-L., Goh, F.-Q., Leong, C.-M., & Ting, H. (2020). Overwork and overtime on turnover intention in non-luxury hotels: Do incentives matter? Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights, 3(4), 397–414. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHTI-09-2019-0104

- Then, S. (2017). The many marvels of Miri. Retrieved December 9, from thestar.com.my.

- Thipsingh, S., Srisathan, W. A., Wongsaichia, S., Ketkaew, C., Naruetharadhol, P., Hengboriboon, L., & Wong, J. (2022). Social and sustainable determinants of the tourist satisfaction and temporal revisit intention: A case of Yogyakarta, Indonesia. Cogent Social Sciences, 8(1), https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2022.2068269

- Tolls, C., & Carr, N. (2021). Horses on trail rides: Tourist expectations. Tourism Recreation Research, 46(1), 132–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2020.1800201

- Uhrich, S., & Benkenstein, M. (2012). Physical and social atmospheric effects in hedonic service consumption: Customers’ roles at sporting events. The Service Industries Journal, 32(11), 1741–1757. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069.2011.556190

- Vinnicombe, T., & Sou, P. U. J. (2017). Socialization or genre appreciation: The motives of music festival participants. International Journal of Event and Festival Management, 8(3), 274–291. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEFM-05-2016-0034

- Wang, C.-Y., & Wu, L.-W. (2011). Reference effects on revisit intention: Involvement as a moderator. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 28(8), 817–827. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2011.623041

- Wang, X., & Wu, D. (2019). Understanding user engagement mechanisms on a live streaming platform. In F. F.-H. Nah & K. Siau (Eds.), HCI in business, government and organizations. Information systems and analytics. (pp. 266–275). Springer International Publishing.

- Wen, C., Prybutok, V. R., & Xu, C. (2011). An integrated model for customer online repurchase intention. Journal of Computer Information Systems, 52(1), 14–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/08874417.2011.11645518

- Wu, C. H.-J., & Liang, R.-D. (2011). The relationship between white-water rafting experience formation and customer reaction: A flow theory perspective. Tourism Management, 32(2), 317–325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2010.03.001

- Yuan, Y., Liu, G., Dang, R., Lau, S. S. Y., & Qu, G. (2021). Architectural design and consumer experience: An investigation of shopping malls throughout the design process. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 33(9), 1934–1951. https://doi.org/10.1108/APJML-06-2020-0408

- Zhang, Q., Liu, X., Li, Z., & Tan, Z. (2021). Multi-experiences in the art performance tourism: Integrating experience economy model with flow theory. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 38(5), 491–510. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2021.1952148

- Zhang, R., & Abd Rahman, A. (2022). Dive in the flow experience: Millennials’ tech-savvy, satisfaction and loyalty in the smart museum. Current Issues in Tourism, 25(22), 3694–3708. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2022.2070459

- Zhao, Y., Srite, M., Kim, S., & Lee, J. (2021). Effect of team cohesion on flow: An empirical study of team-based gamification for enterprise resource planning systems in online classes. Decision Sciences Journal of Innovative Education, 19(3), 173–184. https://doi.org/10.1111/dsji.12240

- Zhong, Y., Zhang, Y., Luo, M., Wei, J., Liao, S., Tan, K.-L., & Yap, S. S.-N. (2022). I give discounts, I share information, I interact with viewers: A predictive analysis on factors enhancing college students’ purchase intention in a live-streaming shopping environment. Young Consumers, 23(3), 449–467. doi:10.1108/YC-08-2021-1367