ABSTRACT

Drawing on the appraisal theory of emotions and based on an online Qualtrics survey conducted among members of the Australian consumer panel (n = 357), this study examined destination equity considering the changing travel preferences in the post COVID-19 pandemic era. The findings empirically support that in addition to conventional destination equity drivers, tourists in the post-pandemic era consider the internal environment when deciding on a travel destination. Peace of mind was identified as a key manoeuvring factor influencing tourists’ behaviours such as higher payment and share-of-wallet. Theoretical and managerial implications of the findings are presented.

Introduction

Tourism is highly prone to epidemics and pandemics (Ugur & Akbiyik, Citation2020), with the COVID-19 pandemic being one of the hardest to hit the tourism and hospitality industry (Dolnicar & Zare, Citation2020; Fang et al., Citation2021; Kourtit et al., Citation2022). During 2020–2021, over 100 million direct tourism jobs were at risk, and the industry suffered a loss exceeding US$ 2 trillion (UNWTO, Citation2022). This downturn in tourism numbers and revenue was largely due to global lock-down rules, consumers’ motive to avoid the pandemic, vaccine laws and regulations in tourism destinations, and misinformation about COVID-19 pandemic influencing travel behavioural intentions (Davras et al., Citation2022; Gursoy et al., Citation2022; Williams et al., Citation2022). While the global tourism industry has started to rebound and tourists are mediating the risks associated with travel and the COVID-19 pandemic in the new-normal era of travel and tourism, there is an urgent need to understand visitor requirements and rebuild their confidence.

Chien et al. (Citation2017, pp. 744–745) note that “One area where there is a clear need for greater understanding relates to a traveller’s risk perception with respect to personal health and well-being, and its downstream consequences on health-preventative and protective behaviour”. As the negative impact of the COVID-19 pandemic is expected to be felt for a prolonged period without a well-formulated recovery plan (Roxas et al., Citation2022), it is recommended that researchers focus on how the pandemic alters tourists’ perceptions of destinations and influence on their behaviour (Zenker & Kock, Citation2020). Within this context, Shin et al. (Citation2022, p. 1) call for tourism researchers to “work with an anticipated ‘new normal’ of the tourism industry and build on their collective knowledge to help tourism organisations overcome the worldwide crisis”.

Selecting a travel destination is a very more complex decision, especially during the post-COVID era when the COVID challenges are still fresh in the tourists’ mind. Health risk is considered to be a crucial factor influencing travel intentions due to the adverse impact of COVID-19 (Ugur & Akbiyik, Citation2020). COVID-19 related risk perceptions are also linked to various service providers, such as airlines (Garaus & Hudáková, Citation2022; Wang et al., Citation2023), accommodation (Kourtit et al., Citation2022; Srivastava et al., Citation2022; Xiang et al., Citation2022), and restaurants (Kim & Lee, Citation2020). Perceived risks, trust in destinations’ pandemic control measures, and other travellers’ safety behaviours (Shin et al., Citation2022) can significantly influence tourists’ destination decisions and destination brand choices.

Cognitive and behavioural theories discussing risk-taking and risk acceptance allude that under uncertainty, the decision-making process is often complicated. Applying a rational decision-making approach, LazAroiu et al. (Citation2020) found that consumers’ decision-making process is linked to perceived risks. Furthermore, trust was considered as an instrumental factor influencing consumer purchases. Personal value systems have biases (Bhaskar et al., Citation2018), whereby overconfident people choose a different anchor value (Gershman, Citation2021). For example, some travellers’ actively engage in thrill-seeking risky behaviours, while avoiding negatively perceived risks (Pizam & Reichel, Citation2004). Reisinger and Mavondo (Citation2005) also found that intentions to travel internationally were determined by lower anxiety levels and a higher degree of perceived safety. In contrast, Hajibaba et al. (Citation2015) theorised that crisis-resistant tourists would follow their travel plans regardless of unexpected internal or external events.

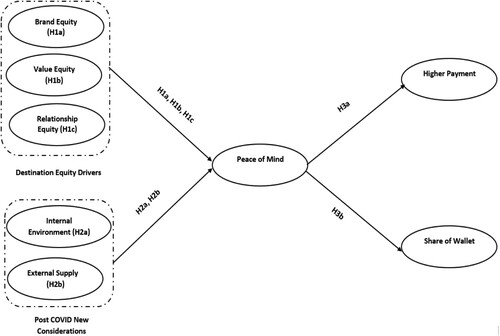

Existing research has focused on different destination attributes on tourists’ perceptions and experiences. However, the concept of peace-of-mind, a crucial element in the post COVID-19 new-normal era, has remained unexplored. Peace-of-mind, an affective experience characterised by low-arousal positive affect (Lee et al., Citation2013), is particularly relevant when the COVID-19 risks are still fresh in the tourist mindset. Although customer equity (CE) has been prominently applied in different industries, little is known about CE in the tourism context (Kim, Boo and Qu, Citation2018). The extant tourism literature largely explored customer-based brand-equity (e.g. Bianchi et al., Citation2014; Tasci, Citation2018, Citation2018); however, CE is an umbrella concept that captures brand, value, and relationship equity (Rust et al., Citation2004) warrants more attention from the researchers to better understand about customer management in the tourism industry. The current study addresses these research gaps by applying the CE model in the tourism destination context and examines the effects of the CE drivers on peace-of-mind en-route to tourists’ behaviours such as higher payments and share-of-wallet. Moreover, the study examines the effects of two additional COVID-19 related considerations such as internal environment and external supply on tourists’ peace-of-mind and behavioural responses. This study argues that destination managers should adopt these renewed approaches to destination equity by exploring tourists’ changing preferences, and conventional destination equity drivers that influence their travel behaviour in the post COVID-19 era.

This study makes several contributions to the growing body of destination equity literature and industry practice. First, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first investigation to explore the mechanism between two post COVID-19 considerations (internal supply and external environment) and tourists’ emotions and behaviours. Furthermore, apart from examining conventional destination equity drivers, this study considers the health and safety requirements related to COVID-19 for tourism operators. Second, this study introduces and investigates two newly identified constructs that help understand the impact of post COVID-19 tourists’ perceptions on their experiences. Third, by applying the destination brand equity model, this study presents a framework that enhances our understanding of tourists’ risk-taking behaviours in the post COVID-19 new-normal era. Fourth, from an industry practice perspective, destination managers can use insights from this study to track the various touchpoints that have an influence tourists’ peace-of-mind and their spending. Finally, this study provides strategic knowledge that can help practitioners enhance customer services in the tourism sector.

Literature review and hypotheses development

Travel considerations in the COVID-19 new-normal era

Past research has extensively explored various factors associated with tourism destinations. For instance, studies have examined brand equity (Gómez et al., Citation2015; Shi et al., Citation2022), service quality (Dedeoğlu & Küçükergin, Citation2020), and brand image (Ashton, Citation2014; Vogel et al., Citation2008). Other related research has focused on destination brand awareness, image, consumer attitude, loyalty, and self-congruity (Majeed et al., Citation2022; Yang et al., Citation2022), and the value associated with price-quality ratio (Prayag & Ryan, Citation2012; Vogel et al., Citation2008). Additionally, research has examined proactive and welcoming communications and drivers influencing tourists’ overall cumulative lifetime value and future repeat visits to specific destinations (Boopen & Viraiyan, Citation2020; Foroudi et al., Citation2019; Hennig-Thurau et al., Citation2002; Hyun, Citation2009).

More recently, research has focused on factors influencing tourists’ destination choices in the post COVID-19 travel context. These factors include assessments of anxiety to travel (Quintal et al., Citation2022; Zenker et al., Citation2021), perceived travel risks (Akritidis et al., Citation2023; Neuburger & Egger, Citation2021; Rahman et al., Citation2021; Ren et al., Citation2022; Su & Tran, Citation2022), and the relationship between perceived vaccination risk and travel intentions (Ekinci et al., Citation2022; Gursoy et al., Citation2022; Seçilmiş et al., Citation2022; Williams et al., Citation2022). To address these risk perceptions and comply with government regulations during the pandemic, tourism destinations reshaped their product and service offerings. This included providing high-quality quarantine facilities, masks, disinfectants, hand sanitisers, air filters and purifiers in bedrooms and other enclosed areas, implementing social-distancing measures, and conducting deep cleaning of customer contact areas (Davras et al., Citation2022; Geisler et al., Citation2022; Kim & Pomirleanu, Citation2021). Furthermore, McKercher and Ho (Citation2021) argue that a destination’s crisis preparedness and sensitivity directly influence consumer perception and destination competitiveness. Therefore, health and safety considerations remain of utmost importance for travellers amidst the COVID-19 pandemic.

Destination credibility, in terms of adherence to COVID-19 health and safety regulations, has a significant impact on potential tourists’ motivations and confidence. Wen et al. (Citation2021) found that following a COVID-19 outbreak, tourists were more inclined to choose destinations with well-established infrastructure and high-quality medical facilities. Research also indicates that tourism industry operators who conform to COVID-19 preventive measures help reduce consumers’ perceived affective and cognitive risks associated with a destination (Bae & Chang, Citation2020; Ugur & Akbiyik, Citation2020). Thus, destinations should emphasise their ability to minimise tourists’ exposure risks to COVID-19 while travelling within a destination.

While the tourism industry thrives by encouraging increased visitor numbers, COVID-19 regulatory guidelines enforced by the governments to protect tourists and locals present significant limitation on tourism operations. Post COVID-19 tourism recommendations include promoting mental health through restricted travel (Karl et al., Citation2020), travelling in smaller groups (Chua et al., Citation2021), avoiding crowded sites (Wen et al., Citation2021), offering contactless tourism and hospitality service experiences (Hao, Citation2021), and engaging with public parks (Buckley & Cooper, Citation2022). Avoiding risks and anxiety associated with potentially contracting COVID-19 and having peace-of-mind while travelling are highly desired in the new-normal era of travel and tourism. Next, we discuss more on “peace of mind” as a construct and its relevance in the post-COVID era.

Peace-of-mind

Peace-of-mind refers to an affective state of mind containing internal peace that captures low arousal positive emotion such as peaceful, calm and serenity (Lee et al., Citation2013). Peace-of-mind in the context of travel refers to the sense of security and safety experienced by the traveller, leading to a lack of anxiety and a positive state of mind (Traskevich & Fontanari, Citation2018; Yousaf et al., Citation2018). Peace-of-mind is dependent on tourists’ responses to the psychological benefits that they receive from their experiences (Chan & Baum, Citation2007). These include comfort, personal security, privacy, and safety of belonging (Schlesinger et al., Citation2020). These positive states often serve as motivation to travel. Otto and Ritchie (Citation1996) found that peace-of-mind ranked as the second most important factor in a tourism destination service experience, following the hedonic aspects that tourists loved or enjoyed.

In addition to the above, we argue that the conventional drivers of customer equity (CE) that influence travellers’ perceptions and travel behaviour remain relevant. We examine both the conventional CE perspectives and new considerations in this study to offer a holistic model of destination equity in the post COVID-19 new-normal era.

Destination equity drivers

The concept of CE is an overall measure of marketing success and refers to the total discounted lifetime value of a customer (Blattberg & Deighton, Citation1996). It is linked to shareholder value as it considers the current and long-term profitability of customers (Rust et al., Citation2004; Rust et al., Citation2000). Maximising CE is important to business success due to its direct financial impacts (Rust et al., Citation2004). The three components of CE drivers – brand equity, value equity, and relationship equity – have been applied in various sectors, including restaurants (Hyun, Citation2009), and professional sports management (Yoshida & Gordon, Citation2012). CE drivers have a positive impact on loyalty and behavioural intentions, satisfaction, and future sales. Therefore, CE drivers are relevant in the tourism destination context as they enable industry practitioners to predict the total value generated by current, repeat, and potential tourists. Furthermore, this understanding allows us to recognise the importance of the CE components in building long-term relationships with customers (Hyun, Citation2009).

Brand equity and peace-of-mind

Brand equity refers to “the customer’s subjective and intangible assessment of a brand, above and beyond its objectively perceived value” (Rust et al., Citation2000, p. 57). It includes the brands’ affective attributes that evoke emotions in individuals (Kang et al., Citation2017). Brand equity examines the emotional connection between the brand and its users (Chiou et al., Citation2013). Research has established that people travel to places that provide them with memorable experiences and satisfaction (Gohary et al., Citation2020; Manosuthi et al., Citation2021). They also prefer to travel to destinations that are considered strong brands, which are attractive, unique, and likable (Chi et al., Citation2020). As such, brand equity plays a vital role in the functioning of the tourism industry.

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to numerous psychological and mental health issues (Buckley & Cooper, Citation2022; Çolakoğlu et al., Citation2021). This is because some destinations are perceived as having a higher risk of contracting COVID-19. As “health concerns are likely to linger in the minds of many” (Shin et al., Citation2022, p. 1), it dampens potential motivations and willingness of potential tourists to travel (Demirović Bajrami et al., Citation2021; Shin et al., Citation2022). Thus, peace-of-mind becomes one of the most crucial factors to consider in the post COVID-19 new-normal era.

Customers evaluate and value features positively if the service provider aims to achieve brand equity, resulting in an emotional brand connection with a specific destination (Castañeda García et al., Citation2018). Moreover, research shows that brand equity enhances the quality of customer experiences. For example, Gao et al. (Citation2019) demonstrated that branding is the primary resource to create rewarding and satisfying brand experiences for customers. Furthermore, Gentile et al. (Citation2007) argued that a good brand establishes a powerful emotional bond with customers by evoking positive moods, emotions, and feelings of happiness. Therefore, it can be argued that if the perceived brand equity is strong, tourists will experience peace-of-mind due to their superior quality experiences. Based on these arguments, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1a: Brand equity has a positive relation with peace-of-mind.

Value equity and peace-of-mind

Value equity refers to “the customers’ objective assessment of the utility of a brand based on perceptions of what is given up for what is received” (Vogel et al., Citation2008, p. 99). Holbrook (Citation1994) argued that value equity is the most significant foundation for marketing, as customers evaluate and establish a relationship with the service provider based on the value they receive. Previous research has also shown that perceived value equity develops customers’ positive emotional state, leading to a favourable attitude toward the service provider (e.g. Gao et al., Citation2019). Moreover, internal fairness is achieved when customers perceive a favourable input-outcome ratio (Oliver & Swan, Citation1989). Consequently, enhanced value equity leads to higher satisfaction with the service provider (Ou et al., Citation2014) and contributes to peace-of-mind. Therefore, we argue that if the price-quality ratio of travel is favourable and the destination offers good value for money, tourists will feel content, peaceful, and comfortable.

H1b: Value equity has a positive relation with peace-of-mind.

Relationship equity and peace-of-mind

Relationship equity refers to the “customer’s view of the strength of the relationship between the customer and the firm” (Rust et al., Citation2000, pp. 55–56). When customers have positive perceptions of their relationships with the service provider, they develop positive feelings and attitudes toward the provider (Gong & Wang, Citation2021; Lee et al., Citation2022). Customers who are treated with care, experience psychosocial benefits due to increased familiarity with service provisions (Vogel et al., Citation2008). Similarly, potential tourists prefer to visit destinations to which they feel emotionally connected and perceive service providers as trustworthy, honest, and truthful (Han et al., Citation2019). Thus, the perceived value and their relationship within a destination further influence their satisfaction (Alananzeh et al., Citation2018), and strong relationship equity increases customers’ peace-of-mind. Based on these arguments, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1c: Relationship equity has a positive relation with peace-of-mind.

Internal environment and peace-of-mind

Research has shown that willingness to travel is influenced by perceived risk events associated with a particular travel destination, with personal safety being a major concern for travellers (Liu & Pratt, Citation2017). Recent studies indicate that anxiety related to COVID-19 has a negative impact on tourists’ travel decisions (Holland et al., Citation2021; Quintal et al., Citation2022; Zenker et al., Citation2021). Since COVID-19 can be prevented by avoiding exposure to the virus (WHO, Citation2022); tourists tend to switch to safer alternatives if they perceive a high risk of exposure at a particular destination (Neuburger & Egger, Citation2021). Tourists consciously avoid destinations with risks related to terrorism, pandemics, and natural disasters (Wu & Shimizu, Citation2020). The features and attributes attached to a destination have a meaningful impact on destination image formation and tourist satisfaction (Schlesinger et al., Citation2020). Therefore, we argue that if the destination has adequate health hygiene, cleanliness, and safety measures, it will enhance customers’ peace-of-mind.

H2a: Internal environment has a positive relation with peace-of-mind.

External supply and peace-of-mind

Zenker et al. (Citation2021) found that COVID-19 related health risks increased travel anxiety. To alleviate travel anxiety, destination trust will be increasingly critical, as potential tourists are less likely to travel if they distrust the destination’s COVID-19 related safety management (Shin et al., Citation2022). This is because fear enhances tourists’ perceptions of COVID-19 related risks, which reinforces their motivation for self-protection (Bhati et al., Citation2022). Furthermore, inadequate hygiene and safety measures will result in negative associations with the destination. A study conducted in six global cities (Kourtit et al., Citation2022) illustrated that Airbnb’s implementation of COVID-19 hygiene and health safety measures led to increased demand despite higher prices. In the same vein, Yu et al. (Citation2022) discovered that crisis response strategies adopted by hotels moderated the effects of affective evaluation and cognitive effort on customer satisfaction. This demonstrates that potential tourists’ peace-of-mind regarding COVID-19 safety is contingent on their perceived risk of contracting the virus while at the destination and their trust in the destination’s COVID-19 safety management procedures in the event of infection. Thus, external supply is a new post COVID-19 consideration for tourists when selecting a destination. External supply refers to the availability of sufficient health and medical supplies, including disinfection control, hand sanitisers, and takeaway food within the destination. Thus, we argue that tourist satisfaction with the health and safety measures of a destination will lead to a sense of peace-of-mind.

H2b: External supply has a positive relation with peace-of-mind.

Outcomes of peace-of-mind

Customers perceive a higher level of service outcome when they are highly satisfied, which subsequently leads to an increased willingness to pay (WTP) (Durán-Román et al., Citation2021; Homburg et al., Citation2005). Furthermore, customers who experience a sense of peace in a particular place exhibit greater WTP (Chang-Young & Yang, Citation2022; Lee et al., Citation2013) compared to less satisfied customers. As such, there exists a positive correlation between service quality dimensions, customer behaviour, WTP for services (Román & Martín, Citation2016), and WTP for the same brand (Dean et al., Citation2002; Suess & Mody, Citation2018). Additionally, customers develop positive perceptions of service delivery when the service performance aligns with the price that they pay (Calabrese, Citation2014). Thus, it is hypothesised that WTP may vary based on perceived satisfaction and peace-of-mind.

H3a: Peace-of-mind has a positive relation with paying more.

H3b: Peace-of-mind has a positive relation with tourists’ share-of-wallet.

Methodology

Data collection

Data were collected using an online Qualtrics survey instrument, facilitated by a third-party vendor. The vendor distributed the survey link to its consumer panel members who voluntarily opted to participate in the survey in exchange for monetary benefits. The survey instrument consisted of three sections. The first section focused on introductory questions, including whether the respondents travelled during the holiday season from December 2020-January 2021. For those who answered affirmatively, subsequent questions were posed to gather information about their travel destination, travel companions, travel mode, motivation for selecting the destination, type of accommodation, budget spent, and the percentage of the total budget allocated to the specified location. The second section contained a series of questions pertaining to established scale items measuring constructs such as brand equity, value equity, relationship equity, peace-of-mind, higher payment, and share-of-wallet (see ). Additionally, the instrument included scale items to assess constructs related to the post COVID-19 context, namely internal environment and external supply. Finally, the questionnaire included demographic variables of the respondents for classification purposes.

Figure 1. Conceptual framework.

The survey instrument was pre-tested among 56 respondents who received the survey link from the third-party vendor. We analysed the pre-test data to ensure the proper functioning of the survey settings in Qualtrics, such as filters and other conditions, and to verify that participants’ responses were accurately recorded in the spreadsheet. Finally, the online survey link was sent to 1,654 members (excluding the 56 pre-test participants). Respondents were filtered based on whether they travelled during the last holiday season and mentioned at least one travel destination. A total of 357 valid responses were included in the data analysis.

Measures

Most of the construct measures were adopted from previous research discussed earlier. For instance, brand equity is based on the destination’s brand image, using items adapted from Vogel et al. (Citation2008). Similarly, value equity was measured by capturing the perception of price-quality in visiting the target destination, with adapted from the same study. Relationship equity was evaluated through satisfaction, trust, and commitment towards the destinations utilising items from Hennig-Thurau et al. (Citation2002) and Hyun (Citation2009).

In addition, the survey instrument included items to reflect the COVID-19 related requirements for tourism operators. Through exploratory factor analysis, these items were categorised into two groups: internal environment and external supply. The internal environment focused on the health, hygiene, and cleanliness precautions taken by the respondents, as well as avoidance of crowds, which have been identified in the literature as key considerations for travel, as discussed earlier. On the other hand, external supply focused on the availability of sufficient health and medical supplies, as well as disinfection control facilities like sanitisers, and the availability of takeaway food.

The measures of peace-of-mind focused on the feelings of freedom, ease, comfortable harmony, and peace experienced while travelling to the respective destination. The scale items for peace-of-mind were adapted from Lee et al. (Citation2013). The dependent variable, higher payment, was assessed using two items that reflected the additional payments paid by respondents due to the extra travel considerations during the pandemic. Share-of-wallet was measured using two items that captured the amount of money spent in the targeted destination relative to the total travel budget, as well as considerations over other travel destinations. All the measures were rated on a seven-point Likert scale, ranging from “Strongly disagree-1” and “Strongly agree-7”.

Empirical results

Sample description

Out of the 357 valid respondents, 46.80% were male and 53.20% were female. The majority of respondents were Australians (84.90%), with an average fortnightly income of $3,600. More than three-quarters (78.4%) of the respondents held at least a diploma, bachelor’s, or master’s degree qualification. A summary of the demographic characteristics of the respondents is presented in .

Table 1. Descriptive characteristics of the respondents (N = 357).

Common method bias

Both procedural and statistical measures were implemented to mitigate the potential effects of common method bias. As a procedural measure, a meticulously crafted cover letter was utilised during data collection to provide clear survey instructions. The cover letter also assured respondents of their anonymity and emphasised the importance of providing honest responses. Additionally, pre-validated scales were employed to measure the constructs of interest. To further minimise common method bias, the items measuring predictor and criterion variables were placed in separate sections, promoting psychological separation (Podsakoff et al., Citation2003).

Under the statistical measure, Harman’s single-factor test was conducted to assess whether a single dominant factor accounted for most of the variances among the measurement items. The exploratory factor analysis revealed the presence of six factors, with the first factor explaining 15.33% of the variance. This outcome indicates that no single factor accounted for a substantial portion of the variances explained by the items. Therefore, common method bias was not identified as a significant issue in this study.

Measurement model

All the scale items used in this study underwent assessment of their uni-dimensionality, reliability, and validity. Initially, an exploratory factor analysis was conducted, confirming that the constructs employed in the model are unidimensional. Subsequently, a confirmatory factor analysis was performed (Anderson & Gerbing, Citation1982) to examine the measurement model using AMOS 26.0. The convergent validity of the constructs, including the first-order dimensions of CE, was established as all items exhibited factor loadings higher than 0.50 and loaded significantly (at the 0.01 level) onto the corresponding latent construct (Hair, Citation2010) (see ).

Table 2. Descriptive statistics and factor loadings of the scale items.

The correlations among the various constructs, including the first-order dimensions of CE, were within the acceptable range (see ), confirming discriminant validity (Kline, Citation2011). The composite reliability (CR) values, which indicate the reliability and internal consistency of a latent construct, ranged between 0.81 and 0.92. These values exceeded the recommended threshold of 0.60 as suggested by Bagozzi and Yi (Citation1988). The minimum average variance extracted (AVE) value exceeded 0.50 (see ), providing further evidence of the discriminant validity of the constructs (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981).

Table 3. Psychometric properties and correlations.

The goodness-of-fit measures for the measurement model demonstrated satisfactory fit indices with the data (χ2 = 819.34; df = 377; χ2/df = 2.17; RMSEA = 0.05; CFI = 0.94; TLI = 0.93; NFI = 0.90), indicating that the constructs were different from each other.

Structural model

We conducted a structural model analysis using AMOS software. The fit indices indicated satisfactory fit (χ2 = 872.61; df = 387; χ2/df = 2.25; RMSEA = 0.05; CFI = 0.93; TLI = 0.92; NFI = 0.90), indicating that the model fit the data well. The structural paths, along with their respective coefficients and significance levels, are presented in .

Table 4. Standardised coefficients and p-value of the structural model.

illustrates that value equity (β = 0.10; p = 0.04) and relationship equity (β = 0.69; p = 0.001) have a positive influence on travellers’ peace-of-mind, whereas brand equity (β = −0.08; p = 0.19) does not show a significant effect. Regarding the COVID related factors, the internal environment (β = 0.18; p = 0.035) significantly influences travellers’ peace-of-mind, while external supply (β = −0.12; p = 0.19) does not exhibit a significant impact. This research shows that peace-of-mind positively has a positive influence on both higher payment (β = 0.15; p = 0.01) and share-of-wallet (β = 0.17; p = 0.006).

Based on the findings (), it is evident that the constructs of value equity, relationship equity, and internal environment significantly influence travellers’ peace-of-mind, which subsequently affects higher payment and share-of-wallet. This suggests that peace-of-mind may act as a mediator in the relationships between value equity, relationship equity, and internal environment with higher payment and share-of-wallet. To test this a post-hoc analysis was conducted using Hayes’ (Citation2013) Process Macro-Model 4 with 5,000 bootstrapped samples. The SPSS Process Macro employs ordinary least squares regression to estimate the parameters of each equation separately, enabling the examination of indirect effects (Hayes et al., Citation2017).

In the analysis, value equity, relationship equity, and internal environment were treated as independent variables (X), while higher payment and share-of-wallet were considered as dependent variables (Y). Peace-of-mind served as the mediating variable (M). Six mediating tests were conducted (3 independent variables x 2 dependent variables). The results are presented in . Specifically, (a), (b), and (c) indicate that the indirect effects of value equity on share-of-wallet (b = 0.04; BootLLCI 0.005 – BootULCI 0.07) and higher payment (b = 0.04; BootLLCI 0.004 – BootULCI 0.08) through peace-of-mind are statistically significant. This supports the mediating role of peace-of-mind in the relationships between value equity and share-of-wallet, as well as higher pay. However, the indirect effects of relationship equity and internal environment on share-of-wallet and higher payment through peace-of-mind were found to be non-significant. This suggests that peace-of-mind does not mediate the relationships between relationship equity and the internal environment with share-of-wallet and higher payment.

Table 5. Mediation analysis through process macro using Hayes (Citation2013) Model 4.

Discussion and conclusion

This study explored factors that influence tourists’ travel behaviour in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Specifically, it focuses on two travel behaviours: the share-of-wallet spent in a particular destination and the higher payment made by tourists for additional safety measures during travel. This study places particular emphasis on peace-of-mind, a psychological construct that plays a crucial role in influencing tourists’ travel behaviours. It argues that both conventional destination equity drivers (brand, value, and relationship) and COVID-19 related factors influence tourists’ peace-of-mind and subsequently impact higher payment and share-of-wallet.

Among the conventional destination equity drivers, the study found that value equity and relationship equity have a positive influence on travellers’ peace-of-mind, whereas brand equity does not. Notably, the impact of relationship equity on peace-of-mind is stronger than other paths and the beta value is stronger for relationship equity than that of other paths, suggesting that travellers prioritised destinations they were familiar with and trust. This study also highlights the importance of value equity, indicating that travellers consider the value for money aspect when deciding on a destination. This finding aligns with Durán-Román et al. (Citation2021) that tourists’ enjoyment is contingent on the quality of service they receive which ultimately contributes to building a relationship with the destination. Therefore, this study’s finding underscores the significance of value equity in travellers’ decision-making process and their perception of receiving value for money, which ultimately influences their destination selection and peace-of-mind.

However, this study reveals that brand equity does not have an impact on consumers’ peace-of-mind. This suggests that potential travellers during the COVID-19 pandemic did not prioritise the brand aspect when selecting a travel destination. This finding aligns with the research conducted by Awan et al. (Citation2021), who found that tourists prioritise health and safety considerations over the brand aspect when choosing a destination to visit. Given the multiple waves of COVID-19 experienced by destinations, tourists may question the reliability and credibility of destination brands. Therefore, it can be argued that tourists’ decision-making is more influenced by the availability of health and safety measures within the destination rather than branding aspects.

Additionally, this study demonstrates that the internal environment significantly influences tourists’ peace-of-mind, whereas no significant effect of external supply on peace-of-mind is observed. Furthermore, peace-of-mind is found to have a significant impact on both higher payment and share-of-wallet, indicating that travellers are willing to allocate a significant portion of their travel budget to a destination where they feel satisfied and at peace. This finding aligns with the research conducted by Lee et al. (Citation2013) and Chang-Young and Yang (Citation2022), highlighting that tourists are willing to spend more money if they feel experience satisfaction and peace in a particular place. Moreover, the results of the post-hoc mediation tests suggest that peace-of-mind acts as a mediator in the relationships between value equity and both share-of-wallet and higher payment. This finding underscores the crucial role of peace-of-mind on travellers’ destination decision-making process, particularly in this post-COVID era. This is supported by the extant literature such as Traskevich and Fontanari (Citation2018) and Yousaf et al., (Citation2018) who found that peace-of-mind serves as a mediator between travel stressors and travel satisfaction.

Implications

Theoretical implications

The theoretical implications of the current research are manifold. Firstly, while past research predominantly focused on the customer-based destination brand equity, the current study makes a significant contribution to the tourism literature by providing a holistic framework for measuring destination equity that includes all the three CE drivers – brand, value, and relationship equity. Secondly, by shedding light on the internal environment considerations and their effects on tourists’ behaviours such as share-of-wallet and higher payment, this study offers new insight into tourists’ responses to equity drivers. The findings emphasises on the significance of value equity, relationship equity, and the maintenance of internal environmental conditions in a destination. These factors play a crucial role in driving tourists’ peace-of-mind, share-of-wallet, and payments. Finally, the study offers a parsimonious model of destination equity drivers to predict tourists’ behavioural responses where peace-of-mind plays a centre role. The mediating role of peace-of-mind in relationships between value equity and behavioural responses (higher payment and share-of-wallet) is a unique contribution of the current study that reconceptualises the destination equity model and extends its dimensions in the post-COVID context.

Managerial implications

The findings of the study offer useful managerial implications. The results highlight that value equity and relationship equity have a positive impact on travellers’ peace-of-mind. This finding underscores the significance of positioning value equity and relationship equity in the minds of tourists. Therefore, tourism and hospitality operators need to assess how the COVID-19 pandemic has influenced the perceptions images of destinations. As demonstrated in this study, the internal environment plays a significant role in shaping tourists’ peace-of-mind. Therefore, operators must ensure the implementation of proper cleanliness, health hygiene, and safety measures. Destination operators should also strive to understand and meet the emerging needs of tourists regarding safety and hygiene factors. Aligning marketing strategies with these needs is essential for restoring consumer confidence.

Tourism operators should consider promoting travel motives that satisfy the socio-psychological needs of visitors, aligning with their mental wellbeing and peace-of-mind requirements. Additionally, providing up-to-date, transparent, and easily accessible information about health conditions and regulations in destinations, including health and safety facilities, hygiene standards is crucial. Utilising health and safety labels alongside marketing campaigns can serve as an additional means to fulfil tourists’ needs for hygiene factors and foster their confidence and peace-of-mind.

Furthermore, the findings suggest that peace-of-mind mediates the link between value equity and behavioural responses such as higher payment and share-of-wallet. Therefore, tourism destinations should prioritise creating an environment of peace and harmony by ensuring safety, security and by offering enhanced tourism offerings. With a key focus on tourists’ peace-of-mind, destination managers can potentially increase the number of tourists who will be willing to visit and spend a higher proportion of their trip budget on that destination.

Limitations and future research directions

This study has several limitations. Firstly, the findings of this study are based on the Australian context, and cultural variations can significantly influence individual perceptions and behaviours. Therefore, future researchers could conduct cross-cultural comparisons between Australia and other tourism destination contexts to examine the generalisability of the model. Considering cultural variables in the research design would provide valuable insights into how the model operates in diverse cultural settings.

Secondly, this study focused on the outcomes of tourists’ higher payment and share-of-wallet. While these outcomes are important indicators of tourists’ behaviour, future researchers may explore additional behavioural outcomes that can shed further light on the effects of destination equity drivers and the mediating role of peace-of-mind.

Furthermore, this study had limitations in terms of the demographic data collected. Future researchers could incorporate a more comprehensive range of demographic variables, such as considering specific segments of the population, including individuals with special needs or different age groups, to gain deeper insights into their perceptions and behaviours within the context of destination equity.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Akritidis, J., McGuinness, S., & Leder, K. (2023). University students’ travel risk perceptions and risk-taking willingness during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease, 51, 102486. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmaid.2022.102486

- Alananzeh, O., Masa’Deh, R., Jawabreh, O., Mahmoud, A., & Hamada, R. (2018). The impact of customer relationship management on tourist satisfaction: The case of Radisson Blue resort in Aqaba city. Journal of Environmental Management and Tourism, 9(2), 227. https://doi.org/10.14505//jemt.v9.2(26).02

- Anderson, J., & Gerbing, D. (1982). Some methods for respecifying measurement models to obtain unidimensional construct measurement. Journal of Marketing Research, 19(4), 453–460. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378201900407

- Ashton, A. (2014). Tourist destination brand image development - an analysis based on stakeholders’ perception: A case study from southland, New Zealand. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 20(3), 279. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356766713518061

- Awan, M., Shamim, A., & Ahn, J. (2021). Implementing ‘cleanliness is half of faith’ in re-designing tourists, experiences and salvaging the hotel industry in Malaysia during COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Islamic Marketing, 12(3), 543–557. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIMA-08-2020-0229

- Bae, S., & Chang, P.-J. (2020). The effect of coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19) risk perception on behavioural intention towards ‘untact’ tourism in South Korea during the first wave of the pandemic. Current Issues in Tourism, 24(7), 1017–1035. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2020.1798895

- Bagozzi, R., & Yi, Y. (1988). On the evaluation of structural equation models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 16(1), 74–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02723327

- Bhaskar, V., & Thomas, C. (2018). The culture of overconfidence. American Economic Review: Insights, 1(1), 95–110. https://doi.org/10.1257/aeri.20180200

- Bhati, A., Mohammadi, Z., Agarwal, M., Kamble, Z., & Donough-Tan, G. (2022). Post COVID-19: Cautious or courageous travel behaviour? Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 27(6), 581–600. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2022.2091944

- Bianchi, C., Pike, S., & Lings, I. (2014). Investigating attitudes towards three south American destinations in an emerging long haul market using a model of consumer based brand equity (CBBE). Tourism Management, 42, 215–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2013.11.014

- Blattberg, R., & Deighton, J. (1996). Manage marketing by the customer equity test. Harvard Business Review, 74(4), 136.

- Boopen, S., & Viraiyan, T. (2020). Destination satisfaction and revisit intention of tourists: Does the quality of airport services matter? Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 44(1), 134–148. https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348018798446

- Buckley, R., & Cooper, M.-A. (2022). Tourism as a tool in nature-based mental health: Progress and prospects post-pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(20), 13112. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013112

- Calabrese, A. (2014). A pricing approach for service companies: Service blueprint as a tool of demand-based pricing. Business Process Management Journal, 20(6), 906–921. https://doi.org/10.1108/BPMJ-07-2013-0087

- Castañeda García, J., Del Valle Galindo, A., & Suárez, R. (2018). The effect of online and offline experiential marketing on brand equity in the hotel sector. Spanish Journal of Marketing, 22(1), 22–41. https://doi.org/10.1108/SJME-03-2018-003

- Chan, J., & Baum, T. (2007). Ecotourists’ perception of ecotourism experience in lower Kinabatangan, Sabah, Malaysia. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 15(5), 574–590. https://doi.org/10.2167/jost679.0

- Chang-Young, J., & Yang, H. (2022). Process of forming tourists’ pro-social tourism behavior intentions that affect willingness to pay for safety tourism during the COVID-19 pandemic: A comparative analysis of South Korea and China. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 27(4), 357–373. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2022.2075774

- Chi, H.-K., Huang, K.-C., & Nguyen, H. (2020). Elements of destination brand equity and destination familiarity regarding travel intention. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 52, 101728. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2018.12.012

- Chien, P., Sharifpour, M., Ritchie, B., & Watson, B. (2017). Travelers’ health risk perceptions and protective behavior: A psychological approach. Journal of Travel Research, 56(6), 744–759. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287516665479

- Chiou, J. S., Chi-Fen Hsu, A., & Hsieh, C. H. (2013). How negative online information affects consumers’ brand evaluation: The moderating effects of brand attachment and source credibility. Online Information Review, 37(6), 910–926. https://doi.org/10.1108/OIR-02-2012-0014

- Chiu, W., Wang, F., & Cho, H. (2023). Satellite fans’ team identification, nostalgia, customer equity and revisit intention: Symmetric and asymmetric analysis. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 40(2), 91–108. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2023.2215264

- Chua, B.-L., Al-Ansi, A., Lee, M., & Han, H. (2021). Impact of health risk perception on avoidance of international travel in the wake of a pandemic. Current Issues in Tourism, 24(7), 985–1002. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2020.1829570

- Çolakoğlu, Ü, Yurcu, G., & Avşar, M. (2021). Social isolation, anxiety, mental well-being and push travel motivation: The case of COVID-19 in Turkey. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 26(11), 1173–1188. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2021.1981415

- Davras, Ö, Durgun, S., & Demircioğlu, A. (2022). Examining relationships between precautionary measures taken for COVID-19 at the destination, service quality, brand equity and behavioral intention: A comparison market segments. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 27(10), 1013–1030. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2022.2152355

- Dean, A., Morgan, D., & Tan, T. (2002). Service quality and customers’ willingness to pay more for travel services. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 12(2/3), 95–110. https://doi.org/10.1300/J073v12n02_06

- Dedeoğlu, B., & Küçükergin, K. (2020). Effect of social media sharing on destination brand awareness and destination quality. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 26(1), 33–56. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356766719858644

- Demirović Bajrami, D., Terzić, A., Petrović, M. D., Radovanović, M., Tretiakova, T. N., & Hadoud, A. (2021). Will we have the same employees in hospitality after all? The impact of COVID-19 on employees’ work attitudes and turnover intentions. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 94, 102754. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102754

- Dolnicar, S., & Zare, S. (2020). COVID19 and Airbnb - disrupting the disruptor. Annals of Tourism Research, 83(2), 102961. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.102961

- Durán-Román, J., Cárdenas-García, P., & Pulido-Fernández, J. (2021). Tourists’ willingness to pay to improve sustainability and experience at destination. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 19(100540), 1–12.

- Ekinci, Y., Gursoy, D., Can, A., & Williams, N. (2022). Does travel desire influence COVID-19 vaccination intentions? Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 31(4), 413–430. https://doi.org/10.1080/19368623.2022.2020701

- Fang, Y., Zhu, L., Jiang, Y., & Wu, B. (2021). The immediate and subsequent effects of public health interventions for COVID-19 on the leisure and recreation industry. Tourism Management, 87, 104393. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2021.104393

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

- Foroudi, P., Mauri, C., Dennis, C., & Melewar, T. (2019). Place branding: Connecting tourist experiences to places. Routledge.

- Gao, L., Melero-Polo, I., & Sese, F. J. (2019). Customer equity drivers, customer experience quality, and customer profitability in banking services: The moderating role of social influence. Journal of Service Research, 23(2), 174–193. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670519856119

- Garaus, M., & Hudáková, M. (2022). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on tourists’ air travel intentions: The role of perceived health risk and trust in the airline. Journal of Air Transport Management, 103, 102249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jairtraman.2022.102249

- Geisler, S., Senftleben, K., Hartmann, C., & Moritz, S. (2022). Evaluation of hygiene measures at a series of mass gathering events during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Sport & Tourism, 26(3), 285–296. https://doi.org/10.1080/14775085.2022.2086162

- Gentile, C., Spiller, N., & Noci, G. (2007). How to sustain the customer experience: An overview of experience components that co-create value with the customer. European Management Journal, 25(5), 395. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2007.08.005

- Gershman, S. (2021). What makes us smart: The computational logic of human cognition. Princeton University Press.

- Gohary, A., Pourazizi, L., Madani, F., & Chan, E. (2020). Examining Iranian tourists’ memorable experiences on destination satisfaction and behavioral intentions. Current Issues in Tourism, 23(2), 131–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2018.1560397

- Gong, T., & Wang, C.-Y. (2021). The effects of a psychological brand contract breach on customers’ dysfunctional behavior toward a brand. Journal of Service Theory and Practice, 31(4), 607–637. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSTP-09-2020-0217

- Gómez, M., Lopez, C., & Molina, A. (2015). A model of tourism destination brand equity: The case of wine tourism destinations in Spain. Tourism Management, 51, 210–222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2015.05.019

- Gursoy, D., Ekinci, Y., Can, A., & Murray, J. (2022). Effectiveness of message framing in changing COVID-19 vaccination intentions: Moderating role of travel desire. Tourism Management, 90, 104468. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2021.104468

- Hair, J. (2010). Multivariate data analysis: A global perspective (7th / ed.). Pearson Education.

- Hajibaba, H., Gretzel, U., Leisch, F., & Dolnicar, S. (2015). Crisis-resistant tourists. Annals of Tourism Research, 53, 46–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2015.04.001

- Han, H., Yu, J., Lee, S., & Kim, W. (2019). Impact of core-product and service-encounter quality, attitude, image, trust and love on repurchase. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 31(4), 1588–1608. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-05-2018-0376

- Hao, F. (2021). Acceptance of contactless technology in the hospitality industry: Extending the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology 2. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 26(12), 1386–1401. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2021.1984264

- Hayes, A., Montoya, A., & Rockwood, N. (2017). The analysis of mechanisms and their contingencies: Process versus structural equation modeling. Australasian Marketing Journal (AMJ), 25(1), 76–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ausmj.2017.02.001

- Hayes, A., & Preacher, K. (2013). Conditional process modeling: Using structural equation modeling to examine contingent causal processes. In G. R. Hancock, & R. O. Mueller (Eds.), Structural equation modeling: A second course (pp. 219–266). IAP Information Age Publishing.

- Hennig-Thurau, T., Gwinner, K., & Gremler, D. (2002). Understanding relationship marketing outcomes: An integration of relational benefits and relationship quality. Journal of Service Research, 4(3), 230–247. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670502004003006

- Holbrook, M. (1994). The nature of customer value. In R. T. Rust, & R. L. Oliver (Eds.), Service quality: New directions in theory and practice (pp. 21–71). Sage Publications.

- Holland, J., Mazzarol, T., Soutar, G., Tapsall, S., & Elliott, W. (2021). Cruise passengers’ risk reduction strategies in the wake of COVID-19. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 26(11), 1189–1206. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2021.1962376

- Homburg, C., Koschate, N., & Hoyer, W. (2005). Do satisfied customers really pay more? A study of the relationship between customer satisfaction and willingness to pay. Journal of Marketing, 69(2), 84–96. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.69.2.84.60760

- Hyun, S. (2009). Creating a model of customer equity for chain restaurant brand formation. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 28(4), 529–539. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2009.02.006

- Kang, J., Manthiou, A., Sumarjan, N., & Tang, L. (2017). An investigation of brand experience on brand attachment, knowledge, and trust in the lodging industry. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 26(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/19368623.2016.1172534

- Karl, M., Muskat, B., & Ritchie, B. (2020). Which travel risks are more salient for destination choice? An examination of the tourist’s decision-making process. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 18(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2020.100487

- Keiningham, T., Perkins-Munn, T., & Evans, H. (2003). The impact of customer satisfaction on share-of-wallet in a business-to-business environment. Journal of Service Research, 6(1), 37–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670503254275

- Kim, E., & Pomirleanu, N. (2021). Effective redesign strategies for tourism management in a crisis context: A theory-in-use approach. Tourism Management, 87(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2021.104359

- Kim, J., & Lee, J. (2020). Effects of COVID-19 on preferences for private dining facilities in restaurants. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 45, 67–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2020.07.008

- Kim, Y., Boo, S., & Qu, H. (2018). Calculating tourists’ customer equity and maximizing the hotel’s ROI. Tourism Management, 69, 408–421. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2018.05.001

- Kline, R. (2011). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (3 ed.). Guilford Press.

- Kourtit, K., Nijkamp, P., Östh, J., & Turk, U. (2022). Airbnb and COVID-19: SPACE-TIME vulnerability effects in six world-cities. Tourism Management, 93, 104569. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2022.104569

- Lazarus, R. (1991). Cognition and motivation in emotion. The American Psychologist, 46(4), 352–367. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.46.4.352

- Lăzăroiu, G., Neguriţă, O., Grecu, I., Grecu, G., & Mitran, P. C. (2020). Consumers’ decision-making process on social commerce platforms: Online trust, perceived risk, and purchase intentions. Frontiers in Psychology, 11(1), 1–7.

- Lee, I.-T., Choi, J., & Kim, S. (2022). Effect of benefits and risks on customer’s psychological ownership in the service industry. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 34(2), 401–417. https://doi.org/10.1108/APJML-08-2020-0608

- Lee, Y. C., Lin, Y. C., Huang, C. L., & Fredrickson, B. L. (2013). The construct and measurement of peace of mind. Journal of Happiness Studies, 14(2), 571–590. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-012-9343-5

- Liu, A., & Pratt, S. (2017). Tourism’s vulnerability and resilience to terrorism. Tourism Management, 60, 404–417. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2017.01.001

- Majeed, S., Zhou, Z., & Kim, W. (2022). Destination brand image and destination brand choice in the context of health crisis: Scale development. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 0(0), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/14673584221126798

- Manosuthi, N., Lee, J. S., & Han, H. (2021). Causal-predictive model of customer lifetime/influence value: Mediating roles of memorable experiences and customer engagement in hotels and airlines. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 38(5), 461–477. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2021.1940422

- Moors, A., Ellsworth, P., Scherer, K., & Frijda, N. (2013). Appraisal theories of emotion: State of the art and future development. Emotion Review, 5(2), 119–124. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073912468165

- Neuburger, L., & Egger, R. (2021). Travel risk perception and travel behaviour during the COVID-19 pandemic 2020: A case study of the DACH region. Current Issues in Tourism, 24(7), 1003–1016. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2020.1803807

- Oliver, R., & Swan, J. (1989). Consumer perceptions of interpersonal equity and satisfaction in transactions: A field survey approach. Journal of Marketing, 53(2), 21–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224298905300202

- Otto, J., & Ritchie, J. (1996). The service experience in tourism. Tourism Management, 17(3), 165–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/0261-5177(96)00003-9

- Ou, Y.-C., de Vries, L., Wiesel, T., & Verhoef, P. (2014). The role of consumer confidence in creating customer loyalty. Journal of Service Research, 17(3), 339–354. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670513513925

- Pizam, A., & Reichel, A. (2004). The relationship between risk-taking, sensation-seeking, and the tourist behavior of young adults: A cross-cultural study. Journal of Travel Research, 42(3), 251–260. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287503258837

- Podsakoff, P., MacKenzie, S., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

- Prayag, G., & Ryan, C. (2012). Antecedents of Tourists’ Loyalty to Mauritius: The Role and Influence of Destination Image, Place Attachment, Personal Involvement, and Satisfaction. Journal of Travel Research, 51(3), 342–356. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287511410321

- Quintal, V., Sung, B., & Lee, S. (2022). Is the coast clear? Trust, risk-reducing behaviours and anxiety toward cruise travel in the wake of COVID-19. Current Issues in Tourism, 25(2), 206–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2021.1880377

- Rahman, M., Gazi, M., Bhuiyan, M., & Rahaman, M. (2021). Effect of COVID-19 pandemic on tourist travel risk and management perceptions. PLOS One, 16(9), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0256486

- Reisinger, Y., & Mavondo, F. (2005). Travel anxiety and intentions to travel internationally: Implications of travel risk perception. Journal of Travel Research, 43(3), 212–225. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287504272017

- Ren, M., Park, S., Xu, Y., Huang, X., Zou, L., Wong, M., & Koh, S.-Y. (2022). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on travel behavior: A case study of domestic inbound travelers in Jeju, Korea. Tourism Management, 92, 104533. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2022.104533

- Román, C., & Martín, J. (2016). Hotel attributes: Asymmetries in guest payments and gains - a stated preference approach. Tourism Management, 52, 488–497. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2015.08.001

- Roxas, F., Rivera, J., & Gutierrez, E. (2022). Bootstrapping tourism post-COVID-19: A systems thinking approach. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 22(1), 86–101. https://doi.org/10.1177/14673584211038859

- Rust, R., Lemon, K., & Zeithaml, V. (2004). Return on marketing: Using customer equity to focus marketing strategy. Journal of Marketing, 68(1), 109–127. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.68.1.109.24030

- Rust, R., Zeithaml, V., & Lemon, K. (2000). Driving customer equity: How customer lifetime value is reshaping corporate strategy. The Free Press.

- Schlesinger, W., Cervera-Taulet, A., & Pérez-Cabañero, C. (2020). Exploring the links between destination attributes, quality of service experience and loyalty in emerging Mediterranean destinations. Tourism Management Perspectives, 35, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2020.100699

- Seçilmiş, C., Özdemir, C., & Kılıç, İ. (2022). How travel influencers affect visit intention? The roles of cognitive response, trust, COVID-19 fear and confidence in vaccine. Current Issues in Tourism, 25(17), 2789–2804. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2021.1994528

- Shi, H., Liu, Y., Kumail, T., & Pan, L. (2022). Tourism destination brand equity, brand authenticity and revisit intention: The mediating role of tourist satisfaction and the moderating role of destination familiarity. Tourism Review, 77(3), 751–779. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-08-2021-0371

- Shin, H., Nicolau, J., Kang, J., Sharma, A., & Lee, H. (2022). Travel decision determinants during and after COVID-19: The role of tourist trust, travel constraints, and attitudinal factors. Tourism Management, 88, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2021.104428

- Srivastava, P., Sengupta, K., Kumar, A., Biswas, B., & Ishizaka, A. (2022). Post-epidemic factors influencing customer’s booking intent for a hotel or leisure spot: An empirical study. Journal of Enterprise Information Management, 35(1), 78–99. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEIM-03-2021-0137

- Su, D., & Tran, V. (2022). Modeling behavioral intention toward traveling in times of a health-related crisis. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 28(2), 135–151. https://doi.org/10.1177/13567667211024703

- Suess, C., & Mody, M. (2018). Hotel-like hospital rooms’ impact on patient well-being and willingness to pay. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 30(10), 3006–3025. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-04-2017-0231

- Tasci, A. (2018). Testing the cross-brand and cross-market validity of a consumer based brand equity (CBBE) model for destination brands. Tourism Management, 65, 143–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2017.09.020

- Traskevich, A., & Fontanari, M. (2018). Mental wellness in resilient destinations. International Journal of Spa and Wellness, 1(3), 193–217. https://doi.org/10.1080/24721735.2019.1596656

- Ugur, N., & Akbiyik, A. (2020). Impacts of COVID-19 on global tourism industry: A cross-regional comparison. Tourism Management Perspectives, 36, 100744. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2020.100744

- UNWTO. (2022). Impact assessment of the COVID-19 outbreak on international tourism. Retrieved 22 October from https://www.unwto.org/impact-assessment-of-the-covid-19-outbreak-on-international-tourism#:~:text = The%20coronavirus%20pandemic%20caused%20a,in%202021%2C%20compared%20to%202019

- Vogel, V., Evanschitzky, H., & Ramaseshan, B. (2008). Customer equity drivers and future sales. Journal of Marketing, 72(6), 98. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.72.6.098

- Wang, X., Zheng, J., Tang, L., & Luo, Y. (2023). Recommend or not? The influence of emotions on passengers’ intention of airline recommendation during COVID-19. Tourism Management, 95, 104675. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2022.104675

- Wen, J., Kozak, M., Yang, S., & Liu, F. (2021). COVID-19: Potential effects on Chinese citizens’ lifestyle and travel. Tourism Review, 76(1), 74–87. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-03-2020-0110

- WHO. (2022). I like to be safe: The COVID-19 pandemic is not over yet. Retrieved 10 October from https://www.who.int/southeastasia/outbreaks-and-emergencies/covid-19/What-can-we-do-to-keep-safe/protective-measures/pandemic-not-over

- Williams, N., Wassler, P., & Ferdinand, N. (2022). Tourism and the COVID-(Mis)infodemic. Journal of Travel Research, 61(1), 214–218. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287520981135

- Wu, L., & Shimizu, T. (2020). Analyzing dynamic change of tourism destination image under the occurrence of a natural disaster: Evidence from Japan. Current Issues in Tourism, 23(16), 2042–2058. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2020.1747993

- Xiang, K., Huang, W.-J., Gao, F., & Lai, Q. (2022). COVID-19 prevention in hotels: Ritualized host-guest interactions. Annals of Tourism Research, 93, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2022.103376

- Xu, J., McKercher, B., & Ho, P. S. Y. (2021). Post-COVID destination competitiveness. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 26(11), 1244–1254. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2021.1960872

- Yang, F. X., Li, X., & Choe, Y. (2022). What constitutes a favorable destination brand portfolio? Through the lens of coherence. Tourism Management, 90, 104480. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2021.104480

- Yoshida, M., & Gordon, B. (2012). Who is more influenced by customer equity drivers? A moderator analysis in a professional soccer context. Sport Management Review, 15(4), 389. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2012.03.001

- Yousaf, A., Amin, I., & Santos, J. (2018). Tourists’ motivations to travel: A theoretical perspective on the existing literature. Tourism and Hospitality Management, 24(1), 197–211. https://doi.org/10.20867/thm.24.1.8

- Yu, M., Cheng, M., Yang, L., & Yu, Z. (2022). Hotel guest satisfaction during COVID-19 outbreak: The moderating role of crisis response strategy. Tourism Management, 93, 104618. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2022.104618

- Zenker, S., Braun, E., & Gyimóthy, S. (2021). Too afraid to travel? Development of a pandemic (COVID-19) anxiety travel scale (PATS). Tourism Management, 84, 104286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2021.104286

- Zenker, S., & Kock, F. (2020). The coronavirus pandemic – a critical discussion of a tourism research agenda. Tourism Management, 81, 104164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2020.104164