ABSTRACT

Over the past three decades, research on the established linkages between solid waste management and psychological models has progressed rapidly. This informs statutory bodies that wish to design an effective solid waste management system. To further address this crucial task, this paper examined the existing literature on behavioral approaches applied to the study of solid waste. Through a systematic literature review approach, we identified, analyzed, and synthesized available literature across various geographical regions. Based on an analysis of 80 articles, we found that high-income countries (61%) are overrepresented in the existing literature, in which the USA (44%) has contributed the most. Most articles targeted recycling behavior (59%) by applying individual behavior theories (90%), in which the theory of planned behavior was widely tested (46%). In addition, 65% of the articles conducted model testing and 51% conducted empirical studies, revealing a dearth of evaluation studies in the literature. Cluster analyses revealed that psychological factors, comprising 34 variables, were extensively used, allowing future researchers to explore relevant variables from inter-disciplinary domains by adopting a pragmatic paradigm approach. In summary, this review identified four research gaps, recommended paths for future research, and concluded by highlighting the need of investigating social elements to tackle solid waste issues.

Implications: The systematic review presented in this paper is an original contribution to the aforementioned body of knowledge. It makes the case for more researchers, teachers, and students to undertake behavioral projects, thus creating awareness among citizens to participate in waste management activities. The research gaps identified here also highlight the scope for future studies in under-explored areas and in the implementation of pro-environmental models to build a clean and green environment. Furthermore, the findings facilitate the formulation of pro-environmental laws, regulations, and policies in developing countries, where there is a higher need for strict environmental regulations focused on sustainability.

Introduction

Technological advancement, economic growth, and urbanization have resulted in an exponential increase in waste quantities, creating significant health and safety hazards globally. The change in patterns of industrialization and consumer-based lifestyles have led to a dramatic increase in the quality and quantity of solid waste (SW), affecting our environment substantially. Several studies have highlighted that SW is mainly an urban affair (Oabaldiston anf Schott Citation2012: Sharholy et al. Citation2008; Stancu, Haugaard, and Liisa Citation2016; Swaim et al. Citation2014): as the process of global urbanization continues unabated, the combination of increasing living standards, insufficient infrastructure, and a lack of adequate sanitation facilities has overburdened the SW disposal system, causing a series of environmental ramifications. The World Health Organization reported that, in 1900, the world had 220 million urban residents who produced fewer than 300,000 tons of SW per day (Hoornweg and Bhada-Tata Citation2012); and, in 2000, 2.9 billion people lived in cities (49% of the world’s population) and generated 3 million tons of SW per day. The World Bank estimated that, by 2025, the amount of SW generated globally would increase from 1.3 billion tons to 2.2 billion tons per year. In addition, the waste produced by metropolitan cities in developing regions is extremely high, with Asia alone generating 790 million tons of waste (Pappu, Saxena, and Asolekar Citation2007) – four times the amount of SW it generated in 1997. These alarming statistics have prompted scientists from several countries to research effective SW management (SWM) strategies to achieve a sustainable ecosystem.

Most studies conducted in this field have focused on aspects of waste generation (Alwaeli Citation2015), waste disposal (Arıkan, Şimşit-Kalender, and Vayvay Citation2017), waste composition (Karak, Bhagat, and Bhattacharyya Citation2012), waste management (Kamaruddin et al. Citation2017), efficiency of municipalities (Guerrero, Maas, and Hogland Citation2013), technology (Urena et al. Citation2012), environmental sustainability (Menikpura et al. Citation2013), socio-economic conditions (Gordon-Wilson and Modi Citation2015), legal and policy implications (Moh and Manaf Citation2014), and stakeholders’ role (Soltani et al. Citation2015). These studies discussed mitigation of garbage issues and provided solutions to SW problems using a top-down approach in situations in which the waste had already been generated. However, waste is not produced in a vacuum (Hargreaves Citation2011); it is generated owing to human needs and desires in diverse scenarios (Stern Citation2000). The chain of waste generation, consumption, and disposal is under the volitional control of an individual who makes a conscious decision about waste production or waste reduction. Therefore, it is appropriate to adopt a root-cause analysis approach of environmental psychology and examine the interconnected nature of waste behaviors and their antecedents to reach a zero-waste goal. Exploring SWM behavior (SWMB) is imperative at this stage of globalization because the physical and social factors of competitive trade between countries have created great environmental risks.

Many studies have discussed the SWMB models that establish linkages between SWM and psychological models. Although most of these studies offer similar assessments of SW issues, all studies have reported different findings. Further, several studies have adopted diverse theories, research frameworks, tools, and techniques to test the antecedents of SWMB. Some studies have even utilized concepts from fields other than psychology, such as consumer culture (Izagirre‐Olaizola, Fernández‐Sainz, and Vicente‐Molina Citation2015), agriculture (Wang et al. Citation2018), biomass (Miafodzyeva and Brandt Citation2013), and economics and finance (Cecere, Mancinelli, and Mazzanti Citation2014). These attempts to comprehend SWMB concepts, research methodology, and theories have led to theoretical fragmentation and methodological inconsistencies. Moreover, most studies appear one-dimensional in nature, which is problematic since SWM is a multi-faceted issue affecting various levels of environment and society. The behavior that facilitates or impedes effective SWM among individuals requires a deeper understanding. In this context, it is vital to understand existing research on the theoretical frameworks that have contributed to addressing waste issues.

Therefore, this paper presents a systematic literature review (SLR) to answer specific behavioral questions within the domain of SWM. SLRs differ from other types of reviews by adopting a replicable, logical, and transparent process. The focus is on minimizing bias through an exhaustive method to identify extant published and unpublished research and then critically analyze and synthesize the literature to arrive at relevant procedures, decisions, and conclusions (Cook, Mulrow, and Brian Haynes Citation1997). Since progressive research depends upon past studies as well as on attempts to explore the strengths and weaknesses of experimental methods adopted in them, an SLR acts as a guide to the current knowledge within the domain of interest. Thus, we present this paper to identify and review studies that have contributed to mitigating SWM problems by adding to the body of knowledge within environmental protection.

Background

The most persisting avenue of research in SWM has explored the influence of cognitive, sociological, and psychological variables on environmental behavior. Several studies have examined the determinants of SWMB: waste separation (Ghani et al. Citation2013; Pakpour et al. Citation2014), recycling (Arı and Yılmaz Citation2016; Mahmud, Diyana, and Osman Citation2010), waste minimization (Radwan, Jones, and Minoli Citation2012), composting (Tih and Zainol Citation2012), waste prevention (Bortoleto, Kurisu, and Hanaki Citation2012; Stefan et al. Citation2008), social influences on the individual (Comber and Thieme Citation2013; Jones et al. Citation2010; Young et al. Citation2017), food separation (Mondéjar-Jiménez et al. Citation2016), and socio-economic characteristics of the environmental movement (Afroz et al., Citation2011; Swami et al. Citation2011). Traditionally, behavioral scientists have focused on theoretical frameworks and related methodologies to explore the antecedents of environmental behavior, which is considered an integrated and inter-disciplinary facet of environmental psychology (Vining and Ebreo Citation2002). Thus, there are clear advantages to applying psychological theories to pro-environmental behaviors.

According to Darley and Gilbert (Citation1985), environmental psychology is characterized by “mid-range theories” that aim to provide solutions for a wide range of socio-economic and environmental problems. Thus, there has been an increasing focus on interventions that investigate the parameters of behavior and its change. The Medical Research Council (Citation2000) mentions three phases of developing and evaluating complex interventions: (i) the theory phase (collection of evidence, formation of theory, and conceptual model development), (ii) the modeling phase (hypothesis formation and testing of target behavior through different research techniques), and (iii) the experimental phase (conducting trials and experiments and obtaining results). The theory phase is important because it provides a framework to understand the causal determinants of behavior (Eastman and Marzillier Citation1984; Schwartz Citation1968). It provides a mechanism that can be tested and evaluated to accomplish research objectives. Moreover, theory-based evaluations and analysis aid in understanding what works and how a situation could be improved by strengthening theory, across various ethnic backgrounds, diverse geographic regions, and different socio-economic conditions. Theory also provides a consolidated outline of the hypothesized causal processes of a particular behavior. Hence, theory-based studies are useful in understanding behavioral parameters by adopting an explicit causal pathway (Michie and Abraham Citation2004) and enabling the researcher to avoid implicit causal assumptions that may lack scientific evidence and evaluation.

In the context of SWM, there is an association between past behaviors and the status of the environment (Sommer Citation2011). Without a theoretical basis, even an extensive literature review of behavioral interventions may not provide adequate guidance (Marteau et al. Citation2006) on how to frame a research design intervention for this global problem. Therefore, rather than reviewing SWMB literature, we examined social science theories relevant to this topic. We presented research constructs from these theories and studies that stand as examples of how they were applied to SWMB. We then investigated additional relevant approaches that could be used to study the behavioral aspects of SWM.

Theories of behavior and behavior change

The importance of understanding theories and their advantages has been highlighted by earlier researchers who suggested the adoption of combined behavior change techniques within interventions to allow synergistic effects and enhance their effectiveness (Citation1999; Davis et al. Citation2015; Mitchell and Biglan Citation1971). However, choosing a relevant theory can be challenging for researchers given the many theories within behavioral psychology and their similar or overlapping constructs (Michie and Abraham Citation2004). In addition, there is a lack of guidance in choosing an appropriate theory for a particular purpose, such as intervening the behavioral patterns of SWM.

Earlier studies have highlighted that theories may be applied to environmental and behavior change interventions, which generally emphasized individual and inter-personal relationships within society and the environment. Moreover, these theories often concluded that interventions are more effective when variables are targeted at different levels (Davis et al. 2014), such as individuals, communities, specific groups, and societies. They also stressed the benefits of considering a wide range of theories for reviewing a specific discipline, before the selection of a particular theory (Marx and Cronan-Hillix Citation1987). Thus, to improve the selection and application of theory, we need to consider those theories that may be beneficial in tackling specific questions within a particular discipline. In addition, by comprehending various theories, we can assess what theories may have potential applicability regarding environmental behavior and public health.

SWMB is an environmental sustainability issue that affects the quality of citizens’ surroundings, health, social well-being, economic status, and lifestyle. It is also a dynamic discipline encompassing cutting-edge technologies, techniques, methods, and processes. Considering all these factors, we undertook an elaborate review of theories within behavioral sciences, sociology, psychology, technology, and anthropology. We categorized theories as individual behavior theories, social behavior theories, and technology behavior theories. The scoping review exercise fundamentally aimed to address the following question: “What theories exist across the disciplines of behavioral sciences, sociology, psychology, technology, and anthropology that could be used as predictive tools to examine SWMB among citizens?” Thus, we examined the efficiency of those frameworks that promote environmental sustainability via behavioral changes.

Individual behavior theories

This category presents a set of theories that aid in understanding the nature and causes of individual WM behavior (IWMB) issues. It focused on human behavior and changes influenced by the social context.

Health belief model (HBM)

The HBM was originally developed during the 1950s as a cognitive framework to explain beliefs and threats regarding individual well-being and the effectiveness and outcomes of particular behaviors (Rosenstock Citation1974). It is an intervention model that has been applied in the behavioral analysis of pro-environment, resource conservation, and WM. Earlier research revealed similarities between behavior toward maintaining good health and behavior toward natural resource conservation, which suggests they may be related (Janz and Becker Citation1984). Both constitute volitional behavior performed to prevent negative states, poor health, and environmental degradation. Thus, psychologists have used the HBM to predict patterns of IWMB. Lindsay and Strathman (Citation1997) applied the HBM to study citizens’ recycling behavioral patterns. Their results were consistent with HBM – as perceived threats, probability of negative consequences, and self-efficacy were positively related to recycling behavior.

Although the HBM provides a useful framework for behavioral findings in the literature, the relationships between cognitive factors are not well explained. Jackson and Waters (Citation2005) argue that the model is inadequate to explain human behavior owing to its insufficient attention to social norms and habitual factors. Moreover, Lindsay and Strathman (Citation1997) stressed the importance of including variables such as social norms, which may prove useful in understanding SWMB.

Learning theory (LT)

In behavioral psychology, LT describes how individuals absorb, process, and retain knowledge, as well as the actions they exhibit during learning. According to LT, individual behavior is a learning process influenced by reward (such as lottery tickets, prizes, money, incentives, and coupons) or punishment (e.g., penalties or fines; Geller Citation1989). Thus, LT postulates that individuals behave pro-environmentally when they are exposed to environmental stimuli that serve as facilitators of target behaviors. Behaviorists argue that external factors have a significant influence on individual behavior (Diamond and Loewy Citation1991; Katzev and Johnson Citation1987; Katzev and Pardini Citation1988). In that context, Needleman and Scott Geller (Citation1992) found that a recycling rewards program could prompt changes in individual behavior. Similarly, Wang and Katzev (Citation1990) reported a significant improvement in paper recycling when incentives were introduced.

The approach of LT in establishing extrinsic motivation as the sole criterion for behavioral modification has drawn some criticism. Although extrinsic motivation is helpful for short-term behavioral goals, it is not a viable option for long-term behavioral goals (Schultz, Oskamp, and Mainieri Citation1995). This is because rewards are temporary and become obsolete as time goes by. Participants may lose interest after the termination of incentives, thus undoing any changes in behavior. In addition, not everyone would be attracted to an SWM reward program, and exploring a person’s environmental behavior from the standpoint of materialism may not be a feasible solution since SWMB is altruistic by nature. Thus, other ways of comprehending intrinsic motivational factors according to eco-friendly morals, values, attitudes, beliefs, and intentions should be emphasized by LT behaviorists.

Motivation crowding theory (MCT)

MCT, postulated in opposition to LT, posits that external incentives may affect the strength of an individual’s internal motivation for pro-social behavior (Frey and Jegen Citation2001). MCT is viewed by psychologists as relevant because external reward schemes and policy interactions may make certain policies less effective (crowd out) and others more effective (crowding in). Thus, MCT highlights that a person of high intrinsic motivation who does not expect external rewards will behave pro-environmentally. To evaluate this theory, Cecere, Mancinelli, and Mazzanti (Citation2014) conducted a study of 27 European countries to explore the association between the role of motivation and waste prevention. They reported that individual intrinsic motivation led to waste reduction. Comparative collaborative research from 10 European countries, Australia, Canada, and Korea, which examined the role of policy incentives and norms in recycling behavior, reported that monetary incentives had a negative impact on motivating individual pro-environmental behavior (Halvorsen Citation2012).

Environmental instruments play a major role in encouraging safe and eco-friendly waste disposal patterns among citizens. Deci and Ryan (Citation1985) found that external rewards hinder behavioral performance, reducing intrinsic motivation. In the case of SWM, higher subsidies, tax punishments, and an incompatible garbage fee system may reduce individual intrinsic motivation, leading to crowding-out effects. In addition, crowding out is more evident when a monetary element is introduced (Bowles Citation2008; Thøgersen and Folke Citation2003) since citizens may indulge in SWM activities to derive pleasure and satisfaction. Hence, the negative effect of an external intervention may affect the norms of an individual; thus, the hypothesis of MCT is questionable. Additional studies that evaluate and establish the usefulness of MCT in the context of SWM are required.

Norm activation theory (NAT)

NAT, derived from LT, describes the process and significance of examining altruistic behavior in the context of environmental protection. It endorses the idea that social norms are developed owing to the interactions of individuals within society and that personal norms develop from their moral obligations, guilt, and pride. According to Schwartz (Citation1977), norms are activated when two conditions are met: when people believe that their negative actions have hazardous repercussions on the environment (awareness of consequences), and when they are personally responsible for the ecological crisis (ascribed responsibility). NAT is a widely accepted model in environmental psychology, which emphasizes that the activation of personal norms takes place when individuals feel that their quality of life, health, and community well-being are threatened. Matthies, Selge, and Klöckner (Citation2012) used the NAT model to explore the role of parental behavior and investigate the development of recycling and reuse habits among children. They concluded that environmental knowledge and awareness played a major role in establishing personal norms among children. Behavioral strategists have expressed the practical desire to expand SWM participation among residents and have argued that people sometimes act because their personal norms override social norms. In that context, Hopper and McCarl Nielsen (Citation1991) explored the transformation process of norms; they argued that personal norms have a positive association with recycling behavior when awareness of consequences was high. The authors also reported that social norms could significantly transform a non-recycler into a recycler if an intervention took place. Though social norms are relevant in predicting altruistic behavior at a structural level, Oreg and Katz-Gerro (Citation2006) claim that pro-environmental behavior results from a set of beliefs that are under threat and that actions resulting from those beliefs relieve threat and reinstate personal values.

Although NAT is a well-recognized model, researchers have criticized it as a non-predictor of behavior since people do not always report their norms (Darley and Latane Citation1970). Further, the functions of pride and guilt, and their association with NAT, are not well understood. For instance, a non-working individual who always separates kitchen waste does not necessarily separate it owing to pride or guilt; he/she may separate kitchen waste to make better use of organic waste. In this case, personal norms are activated purely owing to economic factors. Similarly, a pro-environmental traveler may be forced to dispose of waste on the roadside owing to the non-provision of trash bins. Thus, norms may not always be useful in assessing behavior.

Self-determination theory (SDT)

SDT explains two main types of human motivation: intrinsic and extrinsic. SDT sources these motivations within a broad description of their roles in the field of cognitive psychology and proposes that the mind mediates individual behavior (Ryan and Deci Citation2000).

Skinner and Chi (Citation2012) examined student motivation and engagement in garden-based school programs, revealing that autonomy, competence, and intrinsic motivation had a significant role in garden learning methods. SDT, unlike LT, posits that intrinsic motivation is a potential predictor of human behavior. However, intrinsic motivation represents the internal characteristics of a person and is subjected to external stimuli. In the case of SWM, the core concepts of SDT – autonomy, competence, and relatedness – are not sufficient to predict the role of motivation (Thøgersen and Folke Citation2003). For instance, a person walking on the road might see a poster of a child with a skin disease owing to unhealthy waste disposal methods, and this may motivate them to separate waste. Hence, other external elements such as community groups; opportunities; convenience factors; provision of WM maps; WM hoardings; and internal potential elements such as environmental knowledge, feel-good factors, heritage, tradition, and culture may play a vital role in defining motivation. As existent literature lacks empirical examination, more cross-cultural studies are needed to reiterate the concepts of SDT.

Self-efficacy theory (SET)

SET posits that actions are determined primarily by individual judgments and expectations of outcomes, and the opportunity to successfully master a skill or cope with a given situation to produce positive results in attaining a goal. According to Bandura and Schunk (Citation1981), people process and weigh various sources of information regarding their ability to manage their behavior. Thus, SET conceptualizes that individuals are capable of self-regulation and of being active participants in environmental protection. Although researchers have not tested this theory, the concept of self-efficacy is incorporated in household WM such as garbage reduction (Taylor and Todd Citation1995), waste prevention (Karbalaei et al. Citation2013), composting (Taylor and Todd Citation1997), WM participation (Åberg et al. Citation1996), and recycling (Chu and Chiu Citation2003; De Young Citation1986; Seacat and Northrup Citation2010; Thøgersen, 2003). Furthermore, Geller (Citation1995) proposed an altruistic behavior framework – the “actively caring model” – and included self-efficacy as an important part of environmental empowerment among the public.

Although Bandura (Citation1977) claims SET is a unifying theory, it has drawn criticisms for being unclear about the differential concepts of self-efficacy. Some researchers claim the conceptual framework is unclear, as the association between self-efficacy and outcome expectations is problematic (Eastman and Marzillier Citation1984; Teasdale Citation1978). This is because the outcome expectation varies across tasks and situations for each person. Some researchers noted that individuals with high self-efficacy can become over-confident and may set themselves up for failure in a particular task (Teresa and Ormron Citation2008). Furthermore, in a complex problem like SWM, potential outcomes are far more complex. For example, if a person who believes that recycling helps improve environmental quality cannot find a way to do so because office authorities have not provided recycling bins, he/she may dispose of all items in the common bin. Hence, high individual self-efficacy may not guarantee positive outcomes.

Self-regulation theory (SRT)

SRT primarily focuses on controlling the ability of an individual to exhibit a behavior through self-evaluation, motivation, and modification of emotions and perceptions of those behaviors. According to SRT, individuals who resist mundane tasks will create ways to make their tasks more interesting and positive. To date, only two studies have applied this theory to SWM. Werner and Makela (Citation1998) applied this model to the study of recycling behavior and found that, although residents found SWM to be an uninteresting task, they continued recycling for personal and societal benefit by adopting creative ways of engagement. Zimmerman (Citation1989) conducted a quantitative study and concluded that individuals should find a way to organize themselves to support recycling behavior.

Although SRT offers a powerful psychological tool for controlling and altering behaviors, it has a major limitation of operationalization, since it comprises a set of functions, decision processes, constant monitoring, and cognitive approaches that are debated among researchers. Higgins (Citation1996) asserted that consecutive self-regulation processes deplete further regulation, making individuals act unfavorably in certain situations. In addition, certain behaviors cannot be controlled as they are beyond conscious control, stemming from irresistible impulses. For example, some people indicate they spend too much time and money on clothes and personal items simply because they cannot resist shopping. Thus, there is debate concerning the extent that self-regulation can be established as a main factor of SWM.

Theory of reasoned action (TRA)

TRA posits that behavioral performance can be best predicted from an individual’s intention or willingness (e.g., “I intend to separate waste before disposal”), which is the most immediate and significant predictor of that behavior (Ajzen Citation1985, Citation1991). According to TRA, intention is determined by two independent components: (1) attitude and (2) subjective norms (SNs). Environmental psychologists have studied the relationship between attitude, intention, and SNs regarding waste behaviors. Goldenhar and Connell (Citation1993) conducted a test on the TRA model and emphasized that TRA is a rational decision-making model since socially relevant recycling behaviors are under individuals’ volitional control. Similarly, Jones (Citation1989) studied the determinants of recycling behavior and concluded that intention is the immediate antecedent of behavior since the individual considers the implications of actions before engaging in recycling activities. In addition, support for SNs has been seen as relatively weak by some researchers (Ajzen Citation1991; Taylor and Todd Citation1997; Terry and Hogg Citation1996). Thøgersen (Citation1994) integrated some variables with the TRA model and concluded that ability and opportunity significantly influence intention. However, a positive attitude had a significant influence on waste separation behavior, in comparison with intention Thøgersen (Citation1994). TRA has been extensively studied and has received support from various researchers (Ajzen Citation1991, Citation2005).

While applying TRA to predict behavior, it has been argued that intention cannot be the immediate determinant as there is a gap between measured intention-behavior and actual intention-behavior. While explaining variance in behavior, several meta-analyses question the predictability power of this model, since TRA can only predict behavior 19–38% of the time (Sutton Citation1998). Further, Couraeya and Edward (Citation1993) addressed the unpredictability of Likert-type scale results while implementing this model for repeated behaviors. Behaviors such as recycling, reusing, and waste composting are monotonous and simply cannot be exhibited at the will of an individual. Skills, resources, suitable planning, and convenience can directly influence a person’s will. In such contexts, intention may act as a mediating factor, while other parameters may directly influence behavior. These barriers specifically apply to contexts where poor infrastructures, shortage of government funds, and lack of resources exist. Hence, lack of exploring more parameters could be one of the reasons for the less predictable nature of TRA.

Theory of planned behavior (TPB)

TPB is a continuation of the TRA model, intended to improve its predictive power with the addition of a new determinant factor: perceived behavioral control (PBC). Similar to TRA, TPB hypothesizes that behavioral intention is the immediate antecedent of behavior. Researchers have highlighted that the type of individual behavior (Davis et al. Citation2006; Sheeran Citation2002) governs the degree of intention-behavior stability; therefore, for an intention to be translated into action, some degree of behavioral control (or control factors like knowledge, awareness, and resources) is a pre-requisite. This control is integrated as PBC by Ajzen (Citation1991). TPB establishes PBC as a second determinant and posits that PBC produces mediating effects on behavior. Ajzen (Citation2005) suggests that the addition of more variables to TPB may increase its predictive power of behavioral antecedents. The transition from goal intention to implementation intention is cognitive in nature; hence, behavioral intention is guided by control beliefs such as the perceived difficulty of performing a behavior and the perceived power of one’s research constructs to complete a task (e.g., “waste separation is easy for me;” Ajzen Citation2005). Zhang et al. (Citation2012) conducted a study at a public university of Hong Kong and found that attitude, SNs, and PBC were significantly associated with intention. Those findings were consistent with Cheung, Chan, and Wong (Citation1999), who revealed that variables such as awareness of consequences and convenience factors play an important role in intention. Ramayah, Wai Chow Lee, and Mohamad (Citation2010) examined recycling behavior among students and found that attitude and social norms were positively associated with behavior. In addition, to understand the significance of environmental awareness on attitude, Chu and Chiu (Citation2003) conducted a test on TPB to understand the behavioral determinants of recycling. They found that SWMB was influenced positively by intention; however, SNs, PBC, and attitude were weakly associated with behavior. Those findings were inconsistent with those of Taylor and Todd (Citation1995), in which attitude was the strongest determinant factor of intention.

According to TPB, the more favorable the attitude, SNs, and PBC, the stronger is the relationship between intention and behavior. However, this thesis has varied significantly across several studies. Moreover, considering the role of each variable across different population groups and behaviors, the combination of all three components does not necessarily predict intention-behavior, as only one or two variables may be required; thus, their relative importance remains unclear. Sutton (Citation1998) conducted a meta-analysis to evaluate the performance of TRA and TPB and concluded that both models do not always predict behavior owing to nine possible reasons. Researchers argued that TPB applies to logical behavior and does not address group behaviors (Bagozzi, Dholakia, and Mookerjee Citation2006) such as recycling rallies, SWM debates and community gatherings, and their influence on the individual. Manstead (Citation1999) argued that TPB has overlooked moral concerns. Similarly, Harland, Staats, and Wilke (Citation1999) reported that the inclusion of moral norms increased the variance proportion of intention from 1% to 10%. However, evidence shows that moral norms are not predictive variables since they are represented within the attitudes of an individual (Kaiser et al., Citation2005). Although questions and challenges have led to improvements in the model, the predictive power of this model is of limited scope since it ignores emotional components, such as environmental threats, sustainability fear, and recycling satisfaction that set the tone for cognitive reactions.

Value belief norm (VBN) theory

VBN theory, an integrated model of Schwartz’s NAT model, establishes a link between individual values, beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors. VBN theory assumes that environmental values guide actions in developing beliefs and play a key role in attitude formation (Stern Citation2000). In the process of behavior formation, a person’s beliefs act as a mediator between attitude and values (Daneshvary, Daneshvary, and Keith Schwer Citation1998), leading toward behavior. Therefore, someone who values the reuse of items above their desire to buy new things may not compromise on environmental values, since they accept the information that reusing methods reduce stress on the environment and they support the belief that unnecessary waste disposal is environmentally harmful. Finally, according to VBN theory, value orientation contributes to moral norms; thus, individuals who possess environmentally conscious beliefs and an awareness of the consequences of pollution, and feel responsible in this process, behave in an eco-friendly manner for the benefit of themselves and others.

The key concept of VBN theory is the relationship between values and behavior. Researchers have conducted studies on SWM by focusing on waste separation (Daneshvary, Daneshvary, and Keith Schwer Citation1998; Izagirre‐Olaizola, Fernández‐Sainz, and Vicente‐Molina Citation2015) and waste minimization behavior (Xu et al. Citation2017). A study conducted in Sweden by Nordlund and Garvill (Citation2002), which explored environmental behavior among householders, reported that personal norms mediated general values and environmental values. The same study concluded that personal norms are activated by public awareness, since awareness triggers guilt, self-respect, and self-accomplishment, thus allowing the public to develop pro-environmental values. To understand the waste generation patterns among American students, McCarty and Shrum (Citation1994) hypothesized that attitude and beliefs mediate values and recycling behaviors. They found that beliefs about recycling were non-significantly associated with recycling behavior; however, inconvenience had a significant impact on recycling behavior.

Typically, just like TPB, a major limitation associated with VBN theory is that it performs poorly for repeated behaviors. This is because behaviors which demand repetition – influenced by intention – become weaker and weaker (Klöckner & Oppedal Citation2011), whereas the influence of habit – which tends to occur subconsciously – can affect individuals’ behavioral patterns (Stern Citation2000; Verplanken and Aarts Citation1999). Additional empirical studies should explore causal variables and their interaction effects, which may have explanatory powers to predict SWMB among citizens.

Social behavior theories

Social scientists argue that there is a link between society and IWMB; thus, social influence (Twigger-Ross, Bonaiuto, and Breakwell Citation2003) has a major role in SWMB. As such, SWMB is a complex and challenging socio-environmental issue that demands a multitude of cognitive approaches. This section discusses related theories in sociology.

Rational choice theory (RCT)

In RCT, mere imitational influence from other individuals is not a social action – it is a rational choice of a person through careful and logical consideration of their own acts (Cockerham, Abel, and Günther Citation1993). Roth and Weber (Citation1976) believe that every action has meaning, and that action without thinking cannot be considered a social action. They endorse the view that rational action is the key concept of RCT and identify three distinguishable factors to explain actions: (1) long-standing traditions, which influence a person’s judgment when they perform a task (e.g., handing down baby clothes between family members); (2) the emotional state of an individual, which can be characterized by love, hatred, sympathy, or compassion (e.g., compassionate feelings toward other beings cultivate eco-friendly waste disposal habits); and (3) personal values and actions rationally influencing SWMB (e.g., the belief that waste reduction is a moral obligation to conserve natural resources). In the context of SWM, where individual actions play a vital role, RCT explains the interconnection between emotions and rationality of an individual within society.

Theorists argue that RCT ignores the wider social structure by providing importance to subjective cases (Boudon and Viale Citation2000). Since subjective cases yield bias and imaginary results, the applicability of this theory in a larger context has been subject to debate. However, since waste is generated by individuals, and their behavior counts toward ecological preservation, environmental psychologists do not consider the subjective focus of RCT as a limitation (Yau Citation2010). RCT assumes that every action is rational in nature; however, we argue against this. For instance, some individuals feel relaxed when they undertake waste composting, others when stitching reused, and some may attend community meetings as a pastime. Hence, not all actions stem from logical thinking. Furthermore, this theory fails to explain the role of social norms that motivate some individuals to act in an altruistic way.

Social cognitive theory (SCT)

SCT is a learning-based theory that states that continuous social learning complements real-life experience and that people learn and behave by observing others in society (Bandura Citation1977). Conceptualizing that social interactions can influence a person’s thoughts, feelings, goals, and behaviors. Social scientists have argued that behavioral change of a person is possible when a person can be both an agent for change and a responder for change (Phipps et al. Citation2013). Haldeman and Turner (Citation2009) conducted a study to investigate the effectiveness of a social marketing program within a community to increase the recycling rate. They applied a mixed-methods approach by distributing recycling containers to householders; data were collected through focus-group interviews and telephone surveys. They revealed a 24% increase in the weight of recyclable materials and concluded that face-to-face contact and distribution of recycling containers had a positive impact on recycling rates. Moreover, their results highlighted that observational learning impacts public recycling behavior. Another study by Lin and Hsu (Citation2015) in Taiwan found that self-concepts, personal outcome expectations, and social sanction were significantly associated with the transition into eco-friendly waste disposal.

SCT states that humans learn and make decisions based on rational thought and there is no room for emotions (Nabi et al. Citation2008; Rhee and Waldman Citation2002). According to this theory, although a learning process may motivate individuals to recycle, antisocial behaviors (e.g., littering in public places, throwing stones on environmental hoardings, and damaging public bins and municipal offices) are the result of emotional responses determined by evolution (Rhee and Waldman Citation2002). Thus, mere observation and learning cannot explain a particular behavior (Labuhn, Zimmerman, and Hasselhorn Citation2010; Pinker Citation2010). Thus, pro-environmental behavior is a complex interactive process with social, motivational, behavioral, and emotional components. To learn a new behavior, an individual’s self-interest, awareness, and knowledge become vital to self-control. What we can learn from this theory is that observation and learning processes are more than the psychological functioning of knowledge and skill.

Social practice theory (SPT)

SPT is one of the most popular sociological and anthropological theories (Holland and Lave Citation2009). According to SPT, practice is a routinized type of behavior that is the culmination of several physical and mental activities (Reckwitz Citation2002). Thus, SPT is an umbrella approach under which various theories are pursued and in which practice itself (rather than individuals within social structures) becomes the core unit of analysis. In this view, SWM activities are not perceived as the result of psychological factors; rather, they are owing to social practices embedded within individuals’ behaviors (Warde Citation2005). SPT thus diverts attention from individuals’ rational choice of “doing” various social practices to “choices” of individuals, emphasizing why certain practices are produced/reproduced, prevented, or cultivated. Therefore, SPT recognizes the role of social practices in accomplishing tasks (Shove Citation2010). According to Reckwitz (Citation2002), SPT provides a plethora of new routes for exploring sustainable behaviors related to social order and human action. SPT has been applied to general environmental behavioral studies, such as climate change, sustainability, and energy conservation; however, the association between SPT and SWM remains unexplored. Nonetheless, research into the interaction between social practices and material contexts (emphasized by SPT) has allowed psychologists to explore the role of individual psychological elements in specific social practices.

SWM is often considered an uninteresting routine that demands lifetime discipline, which leads some to see SWM as an irritating and boring affair. For a habitual practice to develop in an individual, certain internal parameters and external infrastructures are required to stimulate and strengthen safe disposal practices. Furthermore, most practices become habits because of personal experience; e.g., when an individual makes a habit of disposing of dry and wet waste separately after having dengue fever, or a parent reusing cotton clothes as diapers if their baby has developed rashes in the past. SPT focuses on social structure but fails to describe the origin of social practices and their antecedents within individuals. Hence, in future research, a holistic approach might be useful to identify the antecedents of the social practices of an individual.

Technology behavior theories

Our time is characterized by scientific innovation and technological advancement. Staying updated with the latest technological advances and keeping a positive attitude toward SWM are essential to improve our environment. According to Tomlinson (Citation2012), citizens should adopt new technologies to attain environmental sustainability. Regarding waste reduction, information technologies will be a useful tool in the future.

Diffusion of innovation (DOI) theory

DOI theory is a widely accepted model that describes how, why, and at what rate new technologies spread within a social system. The focus of DOI theory is to explore the communication process of spreading information and the time it takes individuals to adopt new technologies, characterizing innovation as a mediating factor of behavior. Rogers (Citation2002) defines innovation as an idea or practice that is perceived and adopted as new by individuals through several stages. The principal method of innovation diffusion is communication. Few researchers have acknowledged the role of technology in WM and applied this model to test the diffusion of SWM policies and programs among citizens. Chen and Chang (Citation2010) researched the effect of DOI theory on recycling methods. They found that environmental policy and diffusion effects had a significant impact on SWM, which led to the accelerating process of recycling among Taiwanese people.

DOI theory may have applicability in places with adequate infrastructure to promote and adopt new technologies. However, societies deprived of basic needs cannot access new technologies. Furthermore, many of the elements of DOI theory are more suitable for Western nations and less relevant to developing countries. These economic and socio-cultural differences between societies act as a barrier to apply this model globally. DOI theory is more of a business model and hence utilized more in management, technology, and economic innovation (Salhofer et al., Citation2008). However, specific behaviors such as waste separation depend on psychological factors, resources, and social systems, which are not addressed by DOI theory. Furthermore, when government bodies initiate innovations and programs, diffusion of external elements may not be uniform owing to physical and social factors that may influence the flow of innovation among citizens. Since social norms and the rate of acceptance within society determine innovation, the application of this model in developing countries cannot be generalized.

Technology acceptance model (TAM)

TAM, derived from TRA, is one of the most widely accepted models in predicting user adoption of information systems. Davis (Citation1989) and Venkatesh and Davis (Citation2000) considered perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use to be the two primary determinants which determine technology adoption and actual system use.

SWM is a dynamic field that seeks transformation through technology, tools, and techniques in improving recycling rates, automated waste collection, composting methods, and landfill modernization. The success of these technologies depends on individuals who accept or reject them. SWMB studies that apply this model are lacking. In the context of SWM, this model is not applicable to all ages and groups (e.g., elderly people in rural areas may not understand how to use new technologies). Furthermore, some might argue that technology worsens the relationship between humans and the environment. Thus, TAM application among the general population requires further research.

Research method

We conducted an SLR to map out critical areas where further scientific research is required. Since an SLR is a synthesis of past research to address specific questions, it helps researchers summarize ample evidence by explaining differences among studies, which is a critical objective in framing and establishing theories (Bower and Gilbody Citation2005). The questions subjected to methodical and scientific analysis in SLRs can pave the way for further research by investigating the consistency and generalization of evidence within the field of SWM. It is also advantageous in building hypotheses that can be subjected to empirical investigations. Therefore, the findings obtained from these research aid practical applications where future researchers can conduct more studies to explore why some individuals participate in SWM activities and some do not.

The following steps were undertaken during our systematic research process:

Defining research questions (RQs)

To obtain an overview of current research on the antecedents of SWMB, we formulated the following four RQs:

RQ1: What current theories contribute to the prediction of SWMB?

We included behavioral theories from several fields that could aid in investigating SWMB.

RQ2: What theory pertaining to SWMB is the most examined in the literature?

This question was defined to investigate the most examined theory in exploring SWMB.

RQ3: What are the focal research themes used in SWMB studies concerning research type and contribution?

This question explored the themes adopted in SWM theories to identify possible research gaps.

RQ4: What variables that influence SWMB were identified by earlier researchers?

This question explored current knowledge of SWMB aspects that might lead to the formation of a hypothesis.

Identifying keywords and search strategy

A literature search was conducted to identify the behavioral determinants of SWM. We applied a simple search string – “solid waste management behavior AND theories.” We identified 10 electronic databases with SWMB-specific publications, which included peer-reviewed journals. Our search included articles published between January 1, 1968 and May 30, 2020 from the following sources: American Psychological Association (APA), Association of Consumer Research, Clocks, EBSCO Host, Emerald Insight, Google Scholar, JSTOR, Open Access Research Database, SAGE, SpringerLink, Taylor & Francis, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, University of Massachusetts Press, University of Wisconsin Press, and Wiley Online. Databases that did not allow the search items along with Boolean operators or databases that denied access to full articles were not included. Although we did not limit the publication period to a specified year/date, it eventually turned into January 1968 to May 2018. The selected, “Words, deeds, and the perception of consequences and responsibility in action situations” from the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology (Schwartz Citation1968) was the first article selected from APA. Similarly, the last paper, “Food waste behavior at the household level: A conceptual framework” was from the Journal of Waste Management (Abdelradi Citation2018).

The search was conducted using standard filters and sensitivity analysis. We accounted for diversified theories and their complex bodies of evidence in volume and breadth. The search was restricted to titles and abstracts to retrieve content relevant to this research. Because our research focused on SWMB and related theories, we conducted a separate search for each theory related to SWM in all databases to retrieve the maximum number of published articles. Thus, the search strategy included three sets of search items: (1) list of theories (e.g., behavior change theories), (2) theories and their relevance in understanding behavior change in general (e.g., NAT), and (3) discipline-specific terms combined with the name of a theory (e.g., SWM and SPT). We identified 10 theories related to individual behavioral theories, three theories related to social behavioral theories, and two theories related to technology behavioral theories.

We used a wide variety of search strings for each database. This is because each database is different and using a single search string did not provide the desired results. Hence, multiple searches were conducted with different combinations of words and search strings. A list of search strings and how these search items were combined is shown in . In addition, potentially relevant behavior change theories were searched through web searches and key information was obtained from web-based resources such as the National Institute of Health, USA, and Government Social Research Unit, UK.

Table 1. Search strings and Boolean operators

Selection and quality assessment

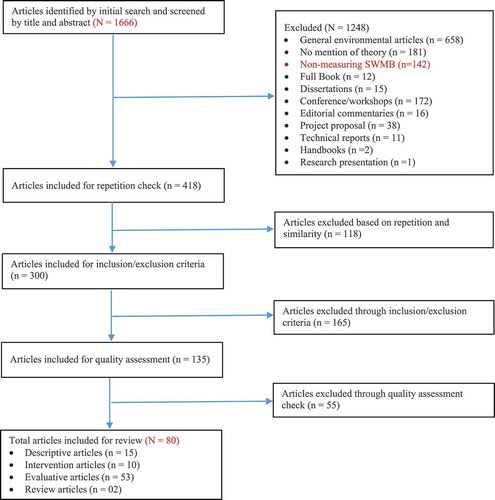

Search strings were used consecutively for selected theories. In the first stage, 1,666 articles were retrieved. We screened for relevant studies by title. If the title was deemed relevant, we analyzed the abstract; at this stage, 1,229 studies were excluded (including conferences, workshops, books, editorial reviews, dissertations, and book reviews). Thus, articles were narrowed to 418 relevant studies, which were further reduced to 300. We excluded those 118 studies after checking for repetition and similarity among multiple databases. In the next step, inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied to each study by examining their introductions, literature reviews, results, and conclusions. Consequently, 165 studies were removed, and we identified 135 studies related to SWMB aspects. These studies were subjected to quality assessment, and 55 did not meet our specific criteria. Thus, the sample was reduced to 80 studies (). Discarded articles at each stage were meticulously assessed and recorded to uphold research quality and for documentation. After completion of the selection process, articles were placed into one of four categories:

Descriptive articles: Those that contained the original description of a theory or extension of that theory written by authors who conceived said theory originally (primary theory sources).

Intervention articles: Those that stated in their methods that they used a particular theory to improve SWM and measured behavior as an outcome.

Evaluative articles: Those in which a theory was tested empirically and longitudinally.

Review articles: Those that systematically reviewed a theory by adopting a clear methodology, describing search strategy, inclusion/exclusion criteria, quality assessment criteria, data extraction, data synthesis, and results.

Inclusion criteria for theories

Theories were incorporated if they (i) met the definition of theory and behavior; (ii) considered behavior as an outcome (e.g., TPB); (iii) referred to individual behavior as the focal point of a social structure (e.g., SCT); (iv) possessed a distinguished framework that explained how systems (e.g., health, environment, and society) relate to each other in the prediction of behavioral outcomes (e.g., HBM); (v) presented applicability in changing behavior; and (vi) referred to implementation values in SWM research, policy, and practice.

Inclusion criteria for articles

Articles were included if they (i) provided clear research constructs of SWMB, using the aforementioned theories; (ii) incorporated theories and methods for the evaluation of behavior change interventions and measured behavior as an outcome; (iii) tested a theory through empirical methods by providing a clear description of sampling, instrument development, data collection, data analysis, and reported the results of their studies; (iv) addressed theory comparisons to explore behavioral outcomes regarding research constructs; (v) addressed studies through the philosophical aspects of SWMB; (vi) evaluated hypothetical models by providing linkages to core models and adding variables to the core model; (vii) tested a theory by focusing on SWMB in the context of waste separation, composting, reduce, reuse, and recycling; (viii) were related to theory and SWMB strategies, practice, and policy; and (ix) criticized or proposed solutions and presented new models or theories to develop contemporary behavioral outcome models.

Exclusion criteria for theories

Theories were excluded if (i) their application did not provide a clear benefit to research behavioral change regarding SWM, (ii) they focused on group behaviors in which individual behavior was not referred within units/corporations (e.g., organizational behavior, and contingency theory), or (iii) they focused on cognition but were not behavior-specific (e.g., social comparison theory).

Exclusion criteria for articles

Articles were excluded if they (i) mentioned WM behavior in titles and abstracts but focused on other forms of waste (e.g., bio-waste, hazardous waste, and animal waste); (ii) discussed general environmental issues (e.g., global warming, climate change, and energy conservation) along with SWMB; (iii) addressed environmental degradation issues where the primary focus was other than SWM; (iv) lacked focus in linking the selected theories and SWMB; (v) tested theoretical models as part of comparison studies where pure cognition was the core determinant (e.g., attitude–intention) rather than actual behavior (e.g., attitude–intention-behavior); (vi) proposed program development, cost-effectiveness, and policy incorporation models without any solid evidence of behavioral theories; (vii) fell into the following categories: full books, handbooks, dissertations, conference posters, presentations, technical reports, proposal reports, keynotes, tutorial course works, workshop summaries, non-peer-reviewed journal publications, non-English publications, and editorial commentaries; or (viii) were repeated articles from different sources.

Quality assessment

A challenging component in SLRs is the selection of high-quality papers for study (Davis et al. Citation2015; Tranfield, Denyer, and Smart Citation2003). Although there are no standard definitions for choosing a high-quality paper, researchers express that high-quality papers include context-based research (Verhagen et al., Citation1998; Whiting et al. Citation2003), appropriate research design to minimize bias, theory applicability, relevant RQs, visibility in peer-reviewed journals and key sources, accurate definitions of key terms, and innovation to the body of knowledge (Oxman Citation1994; Tranfield, Denyer, and Smart Citation2003). Since this study was an evidence-based systematic review, only the definitions of quality in connection to this research were considered. Apart from adopting a rigorous process of scrutinizing the articles by reading selected studies back and forth several times, a significant part of this process was the consideration of inclusion criteria from peer-reviewed journals. In addition, we reviewed key literature that emphasized the synthesis of scientific and philosophical aspects of theories, which are reproducible for experimentations and contribute to understanding the determinants of SWMB and behavior change.

Data extraction

Data extraction was undertaken based on the results of previous steps. Since data extraction also aids in data synthesis, we divided this section into three distinct parts: (i) general characteristics of included studies, (ii) classification scheme, and (iii) identification of variables.

General characteristics

This segment presents the analysis that answers RQ1 and RQ2. The extracted data contained features such as (i) country where the research was conducted, (ii) database, (iii) journal that published the study, (iv) article type (descriptive, intervention, evaluative, review, etc.), (v) source type (primary or secondary), (vi) theory used (HBM, MCT, TPB, etc.), (vii) research techniques (qualitative, quantitative, or mixed-methods), (viii) sampling type (probability and non-probability), (ix) sampling frame (householders, students, university graduates, employees, parents, and public), (x) measurement of behavior (self-report, objective, or both), (xi) target behavior (waste separation, composting, reduce, reuse, and recycle), and (xii) target behavior specification (food, plastic, paper, composting, garden activity, etc.). We also recorded the primary information about selected studies such as author name, study title, and year of the study. We specifically chose this approach to present specific and clear results to overcome the ambiguity of research in this field. The detailed analysis of data extraction will be presented in the following sections.

Classification scheme

We classified the included studies according to three perspectives: research contribution, research focus, and research type. Each item will be discussed in the following sections.

Contribution type

We identified theories related to SWMB from the fields of psychology, anthropology, sociology, and technology; we categorized the selected articles (including descriptive, intervention, evaluative, and review articles) into three disciplines: (i) individual behavior theories, (ii) social behavior theories, and (iii) technology behavior theories.

Research focus

Based on topic orientation and problems addressed in the selected studies, we developed four categories of research focus areas to answer RQ3:

Model development: This category included studies that attempted to develop a model to describe the research constructs of a particular theory.

Model testing: These studies made attempts to test theoretical models to explore the antecedents of SWMB.

Model advancement: These studies contributed to introducing new concepts, propose theoretical frameworks, or report contemporary developments.

Model comparison: These studies compared two or more models by testing them empirically.

Research type

Based on the analysis and the type of included studies, we identified seven types of research ().

Table 2. Research type and description

Identification of variables using cluster analysis

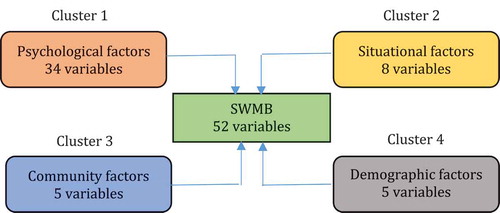

This section provides insights on influential factors that were developed by earlier researchers to investigate the parameters of SWMB. Thus, we performed cluster analysis in multiple steps. First, during data extraction, each article was meticulously studied, and variables identified by earlier authors were captured in Microsoft Excel. Following this, to identify distinguishing concepts and code the texts, we formed single-linkage clusters. Based on the broad spectrum of constructs and operational definitions of concept codes, four clusters were developed (). Once the clusters were formed, each code was scrutinized thoroughly and placed in their relative cluster after careful examination. This exercise was crucial because the organization and consolidation of variables not only illustrates the perception of previous theoretical underpinnings and their research constructs, but also aids in mapping the intellectual territory and the gaps that require further exploration. Thus, we deemed it appropriate to capture separately each measured variable that forms the knowledge stock to build hypotheses for future SWMB studies.

Table 3. Cluster type

Results and discussion

General characteristics

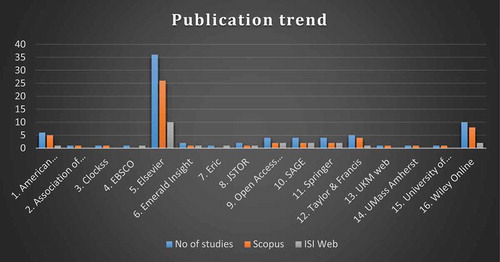

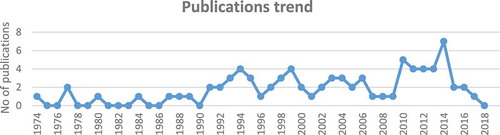

Based on database publication trends, most articles were published by Elsevier (n = 39; 40%). Furthermore, the number of studies published in Scopus-indexed journals was higher (n = 56; 78%), in comparison with ISI Web of Science-indexed journals (n = 27; 22%; ). Regarding the distribution of SWMB articles, there was a peak in field-related research and publications between 2010 and 2014, with seven studies (n = 7; 9%) published in 2014 alone (). Eventually, the trend appeared to follow a normal distribution during this period, which indicates the growing interest among researchers to conduct more studies in developing countries, owing to the increase in population and consumerism. Results indicated that developed countries researched this field mostly from 1990 to 2005.

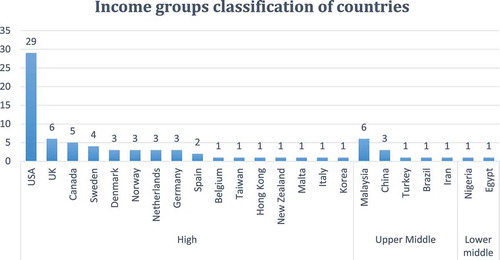

Regarding the distribution of country classification, World Bank classifies all countries based on their gross domestic product – a monetary measure of goods produced annually (https://www.worldbank.org). Considering this, we classified the selected studies as high-, middle-, and low-income countries. Results revealed that most SWMB studies were conducted in high-income countries (n = 66, 83%), in which the USA was the highest contributor (n = 29; 44%; ) as compared to other countries.

Theory identification and frequency of use

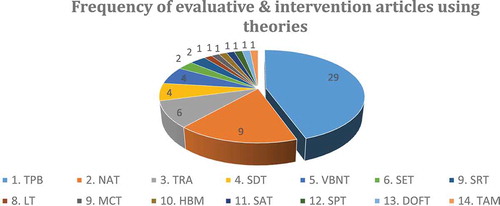

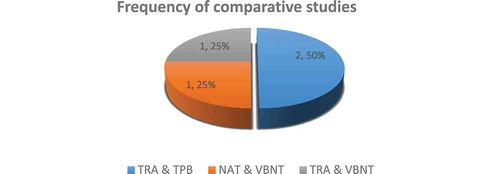

Fifteen theories were identified to potentially predict the determinants of SWMB (RQ1), including 10 theories in the category of individual behavior theories, three in the social behavior theories category, and two in the technology behavior theories category (). Concerning the frequency of use of behavioral theories, TPB was the most frequently used (n = 29; 46%; ; RQ2). Moreover, out of 63 evaluation and intervention articles, four articles addressed comparative analysis, in which TRA and TPB were most common (n = 2; 50%), followed by NAT and VBN theory (n = 1, 25%), and TRA and TPB (n = 1, 25%; ). A description of selected theories has been discussed in previous sections and a list of lead authors, date of publication of papers that originally describes the theory, and the number of articles that used said theory is provided in .

Table 4. Theories identified along with first author, date of primary theory source, and the number of articles identified for the individual, social, and technology behavior theory review

Research design

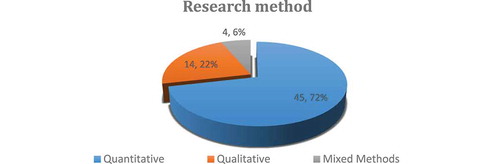

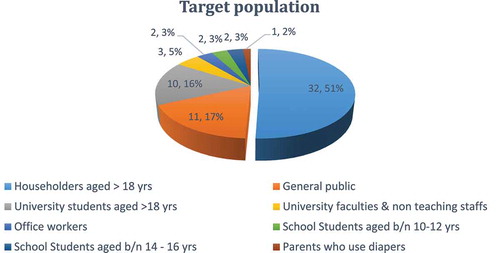

Most evaluation and intervention studies used quantitative techniques (n = 45; 72%), followed by qualitative methods (n = 14; 22%) and mixed-methods (n = 4; 6%; ). Of these, 32 studies used exploratory factor analysis, 39 selected probability sampling, and 49 used self-report measures. Regarding the target population, householders were considered as the highest sampling frame, with representation in 32 studies (mentioned as residents in few studies) that included retirees, homemakers, teenagers, and work-from-home officials aged ≥18 years (). Researchers may have focused on this particular sampling frame because this category often includes people from different groups, which minimizes bias and provides generalizable results. A detailed summary of the research design characteristics of the articles selected for this study is provided in .

Table 5. Research design characteristics of studies included in the systematic review

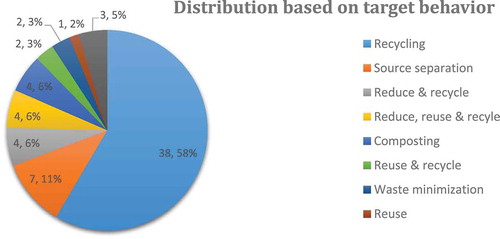

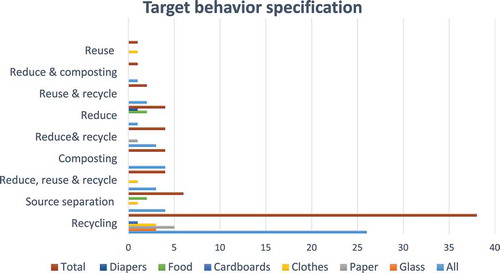

Target behavior

Data extraction yielded nine target behavior categories. Of these, recycling of all items (e.g., plastic, glass, paper, and metal) among householders has been amply studied, accounting for 59% (n = 37) of all studies. A primary reason for researchers to examine this specific behavior could be that recycling is a key activity to convert waste into useful material. With the increase in consumerism and urbanization, people produce considerable waste; however, they can participate in SWM programs and related activities through source separation. Understanding residents’ perception of recycling allows statutory policymakers to take productive actions in policy framing and market provisions, which could be the chief reason behind the vast amount of studies on these recycling behaviors. A high-level summary and a chart detailing the target behavior category () and specification () for each category is provided in .

Table 6. Target behavior category, target behavior specification, and number of articles included in the review

Classification scheme

The classification scheme of the literature reviewed in this research makes it imperative to focus on their contribution type, research focus, and research type in connection to SWMB. A detailed account of this is explained in the following paragraphs.

Model development

This section discusses studies that developed theoretic models based on particular phenomena; we identified 10 studies that fit this criterion (). These studies are exploratory in attempting to link research constructs. Bandura (Citation1977) proposed an integrative model and hypothesized that personal efficacy (their degree of persistence) determines an individual’s behavior. Furthermore, Bandura (Citation1991) calls for cultivating proximal sub-goals to attain a target behavior. For example, if composting is the target behavior, separation, and collection of kitchen biodegradable waste could be a sub-goal. Cognitive theorists are more interested in establishing the determining factors of the target behavior. For example, Rosenstock, Strecher, and Becker (Citation1988) incorporated self-efficacy into the HBM and concluded that a target behavior can be achieved when an individual possesses outcome expectations and efficacy expectations, both of which are required to perform a behavior. However, according to Deci and Ryan (1980) model, the performance of a specific behavior depends on information received externally, from the environment, and internally, from within the individual. Thus, these authors argued that motive plays a pivotal role in deciding a person’s behavior.

Table 7. Contribution and research types presented in 10 papers on model development

Model testing

We identified 53 studies in the model-testing category of research contribution. Of these, 39 studies were empirical, and we categorized 14 papers as evaluation research (). Zhang et al. (Citation2015) tested TPB by ascertaining the antecedents of waste separation behavior among residents of China. They found that SNs, situational factors, and PBC were positively associated with intention. They also found that moral obligations had a positive influence on attitude and concluded that TPB is a powerful model to predict waste behaviors. In a collaborative study that compared waste sorting behavior between Lithuanian and Swedish people, Miliute-Plepiene et al. (Citation2016) reported that Sweden was a “matured recycler” because their waste collection system was accessible. Similarly, Joung and Park‐Poaps (Citation2013) examined the factors that motivate various clothing disposal behaviors by using the TRA model; they found that charity concerns motivate an individual to undertake recycling activities. They also concluded that donation behaviors and situational factors motivate disposal behaviors. Hargreaves (Citation2011) conducted a qualitative study in the UK using semi-structured interviews and observation. They reported a 29% reduction in waste through the application of social practices and material infrastructure and concluded that these strategies can convert a waste-filled society into a resourceful one. Similarly, Akman and Mishra (Citation2015) explored employees’ behavior toward green information technology by testing TAM and concluded that perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness play a critical role in employees’ workplace attitudes. It is thus evident from previous literature that each study has reported different results that exhibit variance. The dynamics of said studies also explain the nature of certain waste behaviors that vary across a range of target populations at different scenarios that are likely to change over time. These results need to be verified in other contexts – an aim of the current review.

Table 8. Contribution and research types presented in 53 papers on model testing

Model advancement

We included 13 studies in the model advancement category of SWMB. Of these, two studies were analytical, six were conceptual, one was a viewpoint, and four were literature reviews (). None of these studies were comparative. Studies that proposed new concepts or added new variables to the basic models but did not test said models were placed in this category. Ajzen (Citation1991) analyzed the status of TPB and argued that a model should contain all important variables to obtain non-error variance results for target behavior. Hence, he proposed the addition of past behavior as the best predictor of the future behavior of an individual. Bandura (Citation1991) proposed an advanced model of SCT and emphasized that human behavior cannot be solely regulated by external factors. He theorized that human behavior operates at three sub-functions at internal levels: self-monitoring, judgment, and self-reaction. He also emphasized self-observation to set achievable goals through self-evaluation process among individuals. This study is significant because it provides insight into how self-regulation evolves in the context of cognitive behavior.

Table 9. Contribution and research types presented in 13 papers on model advancement

Model comparison

Although researchers have compared various theoretical models and integrated two or more frameworks (Kaiser Citation2005; Oreg and Katz-Gerro Citation2006), scant studies have compared two or more basic models (intra-model comparison) or made comparisons within a single model (inter-model comparison) to predict SWMB. We found only four such studies: one was a comparative analysis, one was empirical, one was an evaluation, and one was a literature review (). We identified no studies addressing social and technology behavior theories. Terry, Hogg, and White (Citation1999) conducted an inter-model comparison of TPB to explore the role of self-identity in one model, and to explore the role of self-identity and social identity within the attitude–intention relationship in another model. TPB was used in both models and self-identity appeared as the main predictor of intention. This research was significant as the study revealed the relationship between self-identity and behavior, indirectly through intention. Thøgersen et al. (Citation1996) undertook a review by comparing TRA and VBN theory and concluded that Schwartz’s model of altruistic behavior offers realistic results in targeting recycling behavior.

Table 10. Contribution and research types presented in four papers on model comparison

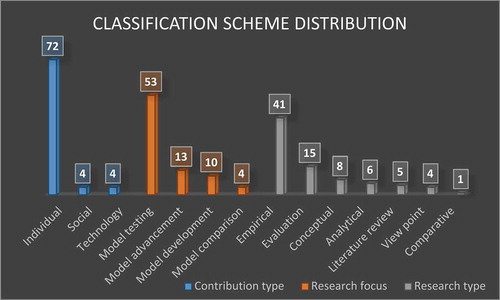

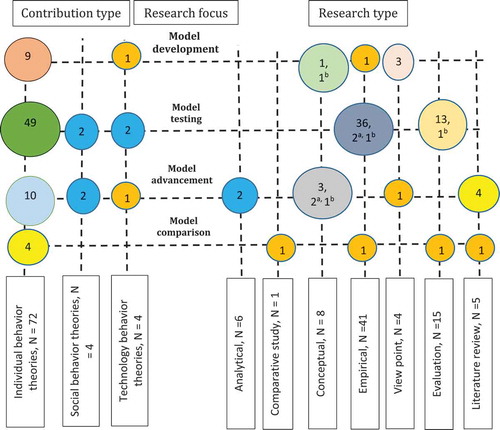

The analysis of the contribution type of each study revealed that individual behavior theories were widely used to determine the antecedents of SWMB (n = 72; 90%). In the distribution of research focus, researchers targeted model testing in maximum articles (n = 53; 66%). The main reason for the predilection toward model testing and empirical research may be to bring waste behavioral changes among citizens through evaluations and interventions using multiple approaches. Moreover, SWMB is entangled within the layers of antecedents that influence its behavioral outcome. The difficulty of its measurability has kindled interest among researchers to add and assess more variables. Although few researchers have conducted comparative analyses using different postulations, model testing is the main method to explore the cognitive and altruistic facets of SWMB. In distribution of research type, empirical studies were the most common (n = 41; 51%). This evidenced a dearth in evaluation studies ().

Based on the classification scheme discussed above, we developed a manual research focus map to avail for an overall view of seven research types and four research contribution types (). This map was primarily developed to gain insight into the nature of studies in the field to date and to identify unexplored research areas that need to be researched in the future.

Identification of variables using cluster analysis

The central part of this systematic process was to summarize the variables utilized from diverse disciplines that may aid in theoretical and methodological SWMB predictions. Thus, we identified 52 variables: 34 belonged to cluster 1 (psychological factors), eight to cluster 2 (situational factors), five to cluster 3 (community factors), and five to cluster 4 (demographic factors; RQ4; ). In addition, attitude was measured most often (n = 43) for cluster 1, opportunities were measured most often (n = 5) for cluster 2, each community variable was measured (n = 1 each) for cluster 3, and age was measured most often (n = 41) for cluster 4 (RQ4). The rationale behind applying psychological factors in most of the studies could be that waste production is closely associated with an individual’s psychological functioning, since it involves the constant conflict of environmental construction and environmental destruction traits in a person. Moreover, unless individuals develop a strong affinity for environmental causes, achieving the eradication of landfills is highly unlikely (Lauren et al. Citation2016). According to some scholars, waste handling demands a high-level of selflessness and commitment to overcome barriers. Although extrinsic motivation such as recycling markets, community education, and incentives may favor SWM actions, most studies highlighted that those activities may not translate into long-established behaviors since SWM is purely altruistic. presents the identified variables for each cluster.

Table 11. Number of variables cited in the review

Though each study offers its own scholarship, considering the space restriction, we present a summarized analysis that highlights salient features that contributed to SWM research and solutions in the past few years ().

Table 12. Summarized analysis and salient features of few studies selected for this review

Study implications

This endeavor to explore the principles of core theoretical constructs and the applicability and limitations of the frameworks revealed an array of 15 theories potentially relevant to mitigating SWM issues. This study sheds light on the methods of evaluating the complex and diverse issues of SWM from both theoretical and practical perspectives. First, from a theoretical angle, the findings imply that the constructs of social and technological theories are under-explored. Since behavioral tendencies develop in a social context, utilization of social elements is key in assessing individual behavior. Second, the existing works on theoretical frameworks for SWMB issues have produced a large pool of publications from different geographical regions of the world – covering a range of research methods, research design, conceptualization of models, dataset formats, application of theories, and addition of extra variables to the core constructs, and so on. Although the researchers have a common objective; i.e., to increase the predictive validity and measurability of proposed SWMB models, this study revealed that such attempts have led to saturation in which common variables are frequently used within the frame of attitude–intention linkages. As it is possible to challenge the reasons for pro-social and pro-environmental behavioral adoption, expansion of regular intention–based linkages may elucidate value-action, social practice-action, and other links promoting SWMB that may be formed owing to different contexts including community, situational, and socio-demographic.