ABSTRACT

This investigation reviews the University of Surrey’s School of Hospitality and Tourism Management (SHTM) attendance policy, requiring students to meet the Senior Personal Tutor (SPT) to determine reasons for absences and to provide support for the student. Research was conducted to achieve four objectives; to understand student and staff attitudes toward the attendance policy, to identify reasons for student absence, to evaluate the effectiveness of registers as a tool for wellbeing intervention and to evaluate the impact of the policy on staff wellbeing. A qualitative approach assessed staff and student views of the policy and findings connect student absences with staff and student wellbeing, indicating that attendance monitoring can improve a student’s sense of belonging. The study provides a framework for using learning analytics to support student and staff wellbeing, draws attention to the role of the SPT and contributes to literature connecting student attendance with staff and student wellbeing.

Introduction

Wellbeing has been described as “an abstract construct about feeling good and functioning well” (Kern et al., Citation2015, p. 262) and there is a consensus that wellbeing is multidimensional relating to both attitude and behavior (Hill et al., Citation2019). Although wellbeing within a higher educational (HE) setting is a specific context (Riva et al., Citation2020), to date there has been limited research on factors contributing to staff and student wellbeing and few empirical studies that examine student perspectives on how their wellbeing can be supported by the university (Baik et al., Citation2019). This is despite evidence of above average levels of poor wellbeing in students in HE across the globe, and although there may be institution, cultural or country variations in this issue, it has become an international crisis (Eloff et al., Citation2021) which suggests scope for research in this area.

Wellbeing and mental health are often discussed interrelatedly. The World Health Organization (Citation2022) describe mental health as “a state of mental well-being that enables people to cope with the stresses of life, realize their abilities, learn well and work well, and contribute to their community.” In a 2023 study, the number of students declaring a health condition (physical or mental) on entering university had climbed to 45% (Maxwell et al., Citation2023) and has been potentially linked to institutions focusing on widening participation which has changed the profile of students (Pollard et al., Citation2023). Furthermore, becoming a student in a post-compulsory setting and attending university has, in itself, become a contributing factor to poor mental health in approximately one fifth of students (FE News, Citation2023). As such, key bodies including the sector regulator, the Office for Students, and the mental health charity Student Minds, have lobbied for the mental health of students to be a key priority for all universities. This is a complex and sensitive area for institutions to tackle, yet without increasing support for students, students could fail to fulfill their academic potential, drop out, or even commit suicide (Pollard et al., Citation2023). As such, research in this area may be of great value.

Monitoring student attendance, as a form of learning analytics, has been cited by a leading wellbeing researcher as one way of collecting data on student behavior that is an “early alert mechanism for potential wellbeing issues” (Ahern, Citation2020, p. 2). Learning analytics is the collection and analysis of student data such as attendance and engagement with learning materials (Pollard et al., Citation2023). Although it can prove useful in achieving retention targets (Gray & Perkins, Citation2019) and assisting institutions in developing workflows to support students (Maxwell et al., Citation2023), collecting and using data can be burdensome to staff (Ahern, Citation2020) and as yet there is little training available on how to interpret such data (Gray & Perkins, Citation2019). Furthermore, it can be argued that attendance monitoring “infantilizes HE … and is anathema to student academic freedom” (Macfarlane, Citation2013, p. 366) and may prompt students to question how and why their behavior is being monitored.

As there has long been skepticism toward the importance of university students attending classes in person (Newman‐Ford et al., Citation2008), this raises the question as to what is the value of learning analytics? In response, some argue that there is a positive correlation between attendance and achievement (Sloan et al., Citation2020) and overwhelming evidence that student attendance is a predictor of engagement and the strongest predictor of achievement (high attendance leading to high performance in assessment) (Kassarnig et al., Citation2017). Attendance is also an indicator of wellbeing, as students that attend in person are more able to develop relationships with their peers and lecturers, leading to a sense of belonging in a new environment (Macfarlane, Citation2013). Additionally, absence from classes may be a strong indication of diminishing mental health and may indicate that a student is struggling to cope (Sahin, Citation2023). Therefore, attendance monitoring is a tool that may identify students experiencing low wellbeing, such as poor mental health.

The School of Hospitality and Tourism Management (SHTM) at the University of Surrey offers a range of management degrees that require students to engage in experiential learning and therefore, in person student attendance is essential. SHTM introduced a mandated student attendance policy in the 2022/23 academic year for all undergraduate and taught postgraduate students. Its implementation was largely in response to staff feedback on low student attendance at face-to-face timetabled classes (lectures, seminars and workshops) which had led to staff dissatisfaction, a reluctance to organize trips and guest lectures and issues with groupwork and group assessments. Staff were asked to monitor attendance through a paper or electronic register, and to refer absent students to the School’s Senior Personal Tutor (SPT) once they recorded three unexplained absences which initiated the collecting and scrutiny of learning analytics data. The SPT would then meet with the student to discuss underlying welfare issues that might relate to their absences and this is classed as a wellbeing intervention. If the SPT had ongoing concerns about the student following this intervention, extra support for them would be put in place. These actions align with the view that “there is a strong case for developing and implementing wellbeing initiatives at the faculty or school level” (Baik et al., Citation2019, p. 685).

This article will explore the impact of the actions taken by SHTM, after a full semester of applying the attendance policy, and as such this investigation was planned to achieve four objectives:

to understand student and staff attitudes toward the SHTM student attendance policy;

to identify reasons for student absence from timetabled classes;

to evaluate the effectiveness of registers as a tool for wellbeing intervention; and

to evaluate the impact of the SHTM student attendance policy on staff wellbeing.

This article therefore contributes to the important work that is being carried out in relation to student attendance and wellbeing and provides a novel student perspective on these issues. It proposes an empirically tested method and process for collecting student data to help universities develop a “data mindset” thus using data to inform initiatives to improve student retention, attainment and wellbeing (SolutionPath, Citation2023, p. 6). At a time when the mental health of students is becoming an increasing priority for HE providers and policy makers, this article provides a relevant and robust investigation into the key pedagogical topics of attendance monitoring and staff and student wellbeing and illustrates the benefits of adopting a simple attendance monitoring system. As the UK appears to be “lagging behind other nations when it comes to learning analytics” (SolutionPath, Citation2023) this could prove particularly useful to UK based institutions.

Literature Review

Several investigations on the impact of student absence on students themselves suggest many reasons for student absence. By comparison, there are few studies which have addressed the general wellbeing of academic staff, and fewer that have explored the impact of student attendance on the wellbeing of educators (McGaughey et al., Citation2019). As such, this review has looked at literature reporting on student absence in the context of a range of disciplines at HE level.

Reasons for Student Absence and the Impact of Absence

Commonly cited reasons for student absence include physical and mental health issues, having children or caring responsibilities (Advance HE, Citation2023) or living far from campus (Sahin, Citation2023). Some studies show that students will miss a class if they find the subject difficult (Sloan et al., Citation2020), if the teaching space is inadequate (i.e. poor ventilation) (Sahin, Citation2023) if the lectures are of poor quality (Bati et al., Citation2013) or if they are experiencing tiredness, apathy or a lack of motivation (Sloan et al., Citation2020). Some students are absent having chosen to spend the time on assignments or exam preparation (Newman‐Ford et al., Citation2008) or because they believe that they can catch up from recordings, other students’ notes or online resources (O’Callaghan et al., Citation2017). Timetabling is an issue for many students with most confirming that the demands of their timetable is a source of stress which adversely impacts their mental wellbeing (FE News, Citation2023). For example, some students skip classes scheduled before 10am or after 4pm, miss entire days when they have long gaps between lectures (Sloan et al., Citation2020) or when they have too many lectures and not enough breaks (Sahin, Citation2023). Being in full or part-time employment is a growing reason for student absence (Advance HE, Citation2023) and according to FE News (Citation2023) seven in ten students have considered dropping out of university due to their struggle to fit employment into their schedule.

McGaughey et al. (Citation2019, p. 712) indicate that students miss class because attending is “stressful and alienating” which is particularly true for undergraduates who experience leaving home, taking on financial responsibility and starting paid employment for the first time (Eloff et al., Citation2021). Eighteen-year-olds are already in a high-risk group for mental disorders (Baik et al., Citation2019) and undergraduates across all disciplines have lower wellbeing levels than the general population of the same age (Blackman, Citation2020). Students that attend classes in person are much less likely to experience stress (Leite et al., Citation2023), but those that are absent are more likely to experience poor cognitive wellbeing (how satisfied they are with life in general) and their stress levels are unlikely to reduce until after they have graduated (Jones et al., Citation2021). Such findings are concerning in light of reports linking poor student wellbeing to a lack of student engagement, poor retention rates and low achievement (Eloff et al., Citation2021) and once again, this points to a need for further research in this area.

The Impact of Student Absence on Staff Wellbeing

Studies of staff wellbeing in HE, point to high stress levels among academics caused by demands to publish, teach and take on administrative duties (Riva et al., Citation2020) while constantly adapting to evolving policies and practices which leave them feeling worn out and emotionally drained (Eloff et al., Citation2021). Academics face increasing expectations to support student wellbeing (Eloff et al., Citation2021), but are often under-supported by their managers, leading to high levels of anxiety, depression, sleeping difficulties and a poor work-life balance, in relation to other occupational groups (McGaughey et al., Citation2019).

Research connecting the wellbeing of academic staff and student absenteeism is limited thus McGaughey et al. (Citation2019) investigation in this area has been valuable and illustrates that academics may react strongly to student absence and see it as a poor reflection on their popularity or teaching style. Furthermore, student absenteeism can substantially undermine staff wellbeing (Offer et al., Citation2020) and creates pressure on staff to reward students that do attend by adding extra value to their classes (O’Callaghan et al., Citation2017). Despite such efforts, low attendance can negatively influence the atmosphere in the classroom and can reduce the lecturer’s engagement with students, thus diminishing the quality of teaching and the enjoyment staff derive from teaching (McGaughey et al., Citation2019). Furthermore, absent students may require additional staff time to catch up, thus adding to an already heavy workload (Sloan et al., Citation2020). Low attendance will impact other learning activities as, for example, lecturers experiencing absenteeism are less likely to invite guest speakers into lectures which also impacts relationships that academics have with industry professionals (McGaughey et al., Citation2019). Therefore, there is a pressing need for research which explores staff wellbeing, which this article will begin to address.

Student Wellbeing and Wellbeing Theory

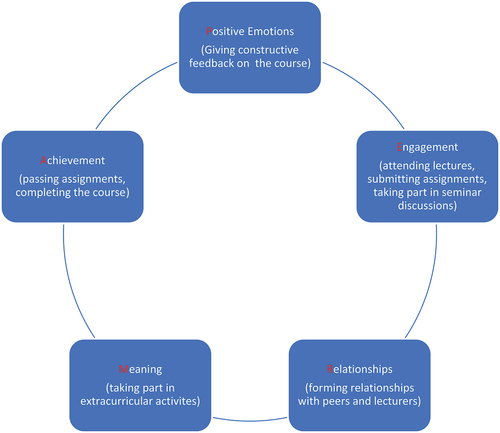

Wellbeing theory identifies five, empirically tested domains of wellbeing which together predict how humans can flourish which are illustrated on Seligman’s (Citation2011) seminal PERMA model of flourishing which are: positive emotions (P), engagement (E), relationships (R), meaning (M) and accomplishment (A). These domains deliver intrinsic rewards and include both eudemonic (having purpose in life) and hedonic (enjoying life) elements (Coffey et al., Citation2016). Eudaimonism can be experienced through personal growth, engaging in fulfilling activities (Hamilton Bailey & Phillips, Citation2016) and feeling valued by others (Seligman, Citation2011). Wellbeing theory has been applied to an educational setting by Hamilton Bailey and Phillips (Citation2016) who confirm that higher intrinsic motivational orientation toward university is associated with greater wellbeing in students and higher academic performance. Ahern (Citation2020, p. 7) also applies the domains of the PERMA model to a HE context and describes them in further detail as illustrated in .

Table 1. An explanation of Seligman’s (Citation2011) PERMA model of flourishing (Ahern, Citation2020, p. 7).

It is widely acknowledged that student wellbeing is a multidimensional concept (Ahern, Citation2020; Kern et al., Citation2015) which is described as relating to students’ behavioral, emotional and cognitive connection to their learning environment (Picton et al., Citation2018). Bowyer and Chambers (Citation2017, p. 20) apply these terms to an educational setting and suggest that behavior is evidenced in student attendance, submission of work and contribution to class discussions while emotions are demonstrated in student interest in a course and their enjoyment of learning and cognition is demonstrated through student desire to go beyond the requirements of the class.

One issue, which may underpin all of these indicators, is whether a student feels a sense of belonging within an institution (Allison et al., Citation2022). For students, belonging can mean having a positive connection to staff, other students and to the discipline itself (Picton et al., Citation2018). Relationships with lecturers are particularly influential on student wellbeing due to the regularity of their interactions (Eloff et al., Citation2021) and in-person attendance is essential to form bonds with staff and students (McGaughey et al., Citation2019). Both O’Keeffe (Citation2013) and Eloff et al. (Citation2021) suggest that student achievement and wellbeing can improve when a student develops a relationship with one key staff member, as what matters to the student is feeling cared for by the institution, which can be achieved through the actions of one person. However, a sense of belonging can be elusive for many students (O’Keeffe, Citation2013) and wellbeing can be compromised if the university is unable to create a caring environment (Ahern, Citation2020). This raises the question of how HE institutions can engender such an environment and monitor student wellbeing to know if it is effective?

blends Seligman’s (Citation2011) PERMA model of flourishing with Bowyer and Chambers’s (Citation2017) definitions of student engagement to illustrate how wellbeing theory can be measured within an educational setting.

Figure 1. Indicators of student wellbeing (Adapted from Seligman (Citation2011) and Bowyer and Chambers (Citation2017)).

As demonstrates, the multidimensional nature of student wellbeing presents a challenge in identifying students that may be struggling, particularly in a large setting such as a university. This need to identify and support students struggling to adapt to their new environment or experiencing poor mental health has led to the rapid adoption of data analytics within education (Solutionpath, Citation2023) and in particular, to monitoring attendance. As such, provides a theoretical framework for this research and allows further testing of Seligman’s (Citation2011) PERMA model, which requires application in a wide range of populations to lead to a better understanding of how flourishing can be achieved (Coffey et al., Citation2016). This investigation will focus on one element of the PERMA model, engagement, as measured through attendance.

Methodology

The study utilized a qualitative approach to explore the wellbeing experiences of students and staff within the case study of a specific hospitality and tourism education setting. Qualitative research provides a comprehensive, multi-faceted understanding of complex phenomena, often revealing the nuanced subjective experiences, perceptions, and attitudes that can go unnoticed in more quantitative approaches (Creswell & Plano Clark, Citation2011). This is particularly relevant to wellbeing research, where the personal and multifaceted nature of mental health and wellbeing necessitates an exploration of personal experiences (Denovan & Macaskill, Citation2017).

Three focus groups (two with students n = 9, and one with staff n = 4 – see ) took place with self-selecting undergraduate and postgraduate taught students (c 600) and all academic staff with teaching responsibilities (c 47). Focus groups took place online, lasted one hour and were facilitated by both members of the research team. Questions for the focus groups, and subsequent interviews can be found in appendix and were drawn from literature and in particular, studies of student absence (McGaughey et al., Citation2019; Sahin, Citation2023; Sloan et al., Citation2020), the impact of this on staff wellbeing (Eloff et al., Citation2021; Riva et al., Citation2020) and wellbeing theory (O’Keeffe, Citation2013; Seligman, Citation2011). Questions were designed to draw out reasons for and against attendance monitoring, reasons for student absence and the impact of student absence. The discussions were recorded, transcribed and then coded manually. Thematic coding and analysis was conducted in two cycles in accordance with Sa’sldaña (Citation2016) method for analyzing qualitative data as illustrated in . In vivo analysis drew out verbatim quotes and key phrases, while thematic, pattern and axial coding clustered and categorized the results to identify dominant or notable themes which include reasons for student absence, the impact of these absences on students and the impact of student absence on staff wellbeing.

Table 2. First and second cycle coding, adapted from Saldaña (Citation2016).

As outlined by Kitzinger (Citation1995), focus groups are conducive to interactive discussions, often revealing group norms, shared beliefs, and emotional reactions toward the research topic, in addition to providing a rich understanding of participants’ experiences and attitudes. In the context of wellbeing research within an educational setting, these group discussions were used primarily to elucidate collective narratives and common practices that might influence individual and group wellbeing.

Seven semi-structured interviews () took place with students who had been referred to and met with the Senior Personal Tutor (SPT) for some form of intervention. All of these students (c 88) were invited to take part in an online or in person interview with the SPT (one of the research team), lasting approximately 20 minutes. Given the existing relationship between the SPT and interviewees, a level of trust had already been established with participants, which is integral to gathering valid data and minimizing bias (Cohen et al., Citation2018). Nonetheless, in order to uphold ethical protocols, participants were self-selecting and able to choose an alternative interviewer. The interviews were recorded, transcribed and then coded manually, also using in vivo, pattern and axial coding to identify the dominant themes which was their patterns of absence and attendance and their relief at experiencing a wellbeing intervention (being contacted by the SPT). As a secondary approach, the interviews offered flexibility and depth in capturing personal narratives. They allow researchers to customize interviews based on each respondent’s unique responses, thereby gaining a more in-depth understanding of their experiences. When examining wellbeing in education, the environment must allow participants to share personal stories, challenges, and coping strategies, thereby revealing multi-dimensional aspects of wellbeing that may be unique to each individual (Smith, Citation2005).

Table 3. Participant data, Authors Own.

Results and Discussion

The results of the focus groups and interviews revealed alignment with previous studies of student absence, insight into how absence impacts staff and raises questions about how best to use learning analytics to support students. The key themes were a consensus on the need for attendance monitoring, the impact of student absence on staff wellbeing, attendance monitoring demonstrating institutional care toward students and the relationship between attendance monitoring and a student’s sense of belonging leading to improved wellbeing. The following abbreviations are used in the discussion:

Student FG: student focus group participant

Student I: student interview participant

Staff FG: staff focus group participant

Reasons for Student Absence and the Impact of Absence

In terms of participant attitudes toward attendance monitoring, the majority of staff and students agreed that monitoring is needed with staff pointing out:

I think that it’s justifiable and particularly with the modules that require very strong teamwork and very strong team engagement. (student FG 4)

I think taking the attendance itself is necessary, so that we have a record, and then they (students) have a sense of responsibility of their own learning. (student FG 3)

However, compulsory attendance was not universally favored as most students, and some staff, suggested that there should be some choice involved. When discussing why students are absent, several responses were recorded that align with previous studies, and in particular students identified illness, tiredness, work commitments and uninspiring lecturers as reasons for missing classes. This was also confirmed by staff who commented:

I know so many students are working exceptionally long hours … the cost of living is not helping. We live in a very expensive part of the world. I think the reality of life is also quite tough for a lot of people. Some of the students also have caring responsibilities, and sometimes timetabling doesn’t help. (staff FG 2)

The ability to catch up afterward and the timetabling of classes (too early, too late, too long a gap between classes) were repeatedly cited. By contrast, students noted that they are motivated to attend when classes relate to assessment, which was confirmed by staff.

Students indicated that when modules involve group work, and when some of this will be conducted in class, they are more inclined to attend. These motivations echo the literature on student views on attendance, particularly studies undertaken by Sloan et al. (Citation2020), Bati et al. (Citation2013) and Sahin (Citation2023).

The Impact of Student Absence on Staff Wellbeing

The results from the staff focus group were mixed in terms of linking attendance to the energy of classroom, with some staff suggesting a positive correlation:

Good attendance brings in its own energy. It brings in a lot of enthusiasm, and you see a class that’s full and vibrant, it adds to the atmosphere, and it makes more people want to get involved. (staff FG 2)

While others indicated that absence doesn’t necessarily negatively impact the atmosphere in the classroom nor the quality of teaching:

The low attenders are probably the ones without any energy, anyway. So, the energy in the classroom comes from the students that participate. (staff FG 1)

However, the negative impact of absence on students and staff were very evident in the data. Staff were concerned and frustrated about the impact of absence on attending students and had taken action in response to, or in anticipation of, poor attendance:

it [absence] has a real impact on seminars with peer-to-peer learning, and the interaction is lost when you don’t have the numbers. (staff FG 2)

It’s quite obvious … that [absence] … has contributed to lots of challenges in that it is unfair to other students. (staff FG 4)

It affects our reputation externally, especially when we take the effort to bring in esteemed guest speakers. We take students on field trips, and that lack of attendance really shows and has a long-term impact for future cohorts as well. (staff FG 2)

I have not yet cancelled anything because of the poor low attendance, but I have decided to not run a guest lecture because [I’m] … anticipating a low attendance. (staff FG 4)

When discussing the impacts of student absence, staff spent more time on how this impacts students than staff, thus demonstrating a clear concern for students. However, the impact of student absence on staff wellbeing was also evident:

it’s quite demotivating. You put in a lot of effort [into] planning the lessons and thinking about group activities … seminars particularly are hugely disadvantaged. (staff FG 2)

Thus, although this shows congruence with McGaughey et al. (Citation2019) assertion that student absence impacts staff wellbeing, this was not a strong theme in this research.

The most insightful and revealing insights on the connections between student attendance and wellbeing came from the interviews. Five of the seven students interviewed, referred to being contacted by the SPT about their absences, as feeling cared for which participant 15 described as “heartwarming”. SI 10 likened it to “a hand reaching out” and confirmed relief that it meant that “someone is aware of the situation.” This sense of relief was echoed by SI 15 who’s absence was caused by several issues. She described how she was “rejecting every kind of kindness” and having to “deal with this myself” until she was contacted by the SPT which she identified as the point when “things started to change.” Similarly, SI 16 confirmed that she was finding it “hard to reach out” for support with the circumstances that were causing her absences but being contacted directly by the SPT began to alleviate her depression, largely because she “didn’t have anyone [else] at all to talk to.” All of the interviewees, except SI 10, confirmed that their attendance improved after meeting with the SPT. These results strongly suggest that for these students, absence from class was related to their poor wellbeing. Thus, confirming that absence can be a sign of a lack of engagement and prevents flourishing as illustrated on the PERMA model.

SI 15 pointed to the importance of personalized contact over an automated intervention. She confirmed that she felt “happy” to talk to the SPT, as she already knew (and was taught by) this person and could trust them. This aligns with the view that relationships with lecturers are particularly influential over student wellbeing (Eloff et al., Citation2021; O’Keeffe, Citation2013). This student felt that it was important that someone contacting her about her attendance knew her name and situation as she would not engage with someone unfamiliar who she felt “doesn’t really care about what’s going on in my life”. By contrast, SI 12, who is not taught by the SPT, felt “just happy that … okay … somebody is keeping tabs on me”.

SI 10 was the only person to express frustration at being contacted by the SPT and at having to explain her absences. Nonetheless, she did admit that the intervention made her feel cared for, and this led her to seeing her doctor much earlier than she would otherwise have done. Participant 10 also confirmed her belief that “they go together hand in hand, wellbeing and attendance.” Both SI10 and SI 11 discussed their wellbeing and confirmed that as a student struggling with poor mental health, it is common to feel isolated and alone. Many of the students interviewed pointed to the intervention as helping them to feel part of the university community:

[after the intervention] I did feel included because … if there’s mental health situation you can feel very alone and it was like … . I feel good … I feel like part of it [the community]. (SI 12)

This strongly aligns with previous studies which have demonstrated the connection between a student’s sense of belonging with their wellbeing and in particular the work of Allison et al. (Citation2022) and McGaughey et al. (Citation2019).

The interview data suggests that using data analytics to prompt an intervention is very positive and can alleviate student anxiety. One student confirmed that being contacted by the SPT:

gave me this assurance of … OK actually … Things can still work out. There’s a solution … . then I’m more relaxed … . I don’t feel that I’m a complete mess, I can still graduate this year. (SI 14)

Similarly, SI 11 described the intervention by the SPT as creating “a bridge … to alleviate the stress that was going on.” He went on to describe how the intervention led to a sharing of his information across departments, which alleviated some of his stress. This led to cross institutional staff being “on the same page and we can create a plan to get through this.” Similarly, SI 10 described the relief she felt at only having to explain her situation to one person. She commented:

If you have 4 lecturers all asking you where you’ve been and why you’ve not been there … . it’s pressure … .but you don’t really want to tell four random people, that you’re not friends with, why you’re not there.

She also expressed gratitude that the SPT would put in place a cross institutional action plan to support her, confirming “people are now aware of my mental health situation.”

However, two of the interviewees indicated that the use of data analytics to prompt a wellbeing intervention, could be a negative experience for students. SI 11 called it “almost … a double attack,” referring to the automated messages she received from data analytics software generated by the SPT when the SPT invited her to attend a meeting to discuss her poor attendance. Similarly, SI 14 commented on the “constant emails” she receives each time she misses a class. She described them as “aggravating” and questioned the need for e-mails generated by attendance data which is available to staff and students, concluding that acting upon the data generates “too much pressure [on students].”

This suggests that as the use of learning analytics becomes more widely used, attention should be drawn to student attitudes toward the use of their data and how it is acted upon.

In summary, the most notable theme from the interviews was that students overwhelmingly feel cared for when their attendance is monitored, and their poor attendance is acted upon, as illustrated by one student who now receives support for a mental health condition:

[it meant that] someone is aware of the situation … .it really did help, it created a bridge … to alleviate the stress that was going on … . I felt supported not singled out. I felt included. (SI 11)

This would once again suggest that student absence, which is an example of lack of engagement on the PERMA model, can indicate that a student is experiencing poor wellbeing.

Practical and Theoretical Implications

In terms of the theoretical implications of this investigation, the data collected forms the basis of what will become a replicable and longitudinal study on the effects of an attendance policy, and associated interventions, on student attendance, referrals, and attainment. It confirms that, as wellbeing theory suggests, student attendance is a sign of engagement, and absence can mean a lack of engagement which can impact student wellbeing. The interviews demonstrated that for students experiencing poor wellbeing, this was impacting their eudemonic and hedonic experiences and thus prevented flourishing. This investigation confirms that attendance is an example of engagement, as suggested on the PERMA model. Thus, attendance monitoring is a way to identify students that may be struggling with an issue, such as their mental health, which prevents them from flourishing. Additionally, it illustrates the benefits and some of the challenges of collecting, analyzing, and acting upon student data, and confirms the value of learning analytics in a HE context.

In terms of practical implications, this study has demonstrated that learning analytics can be conducted through a simple process of data collection from paper registers and how qualitative data combined with attendance data provides a more holistic and insightful picture of student performance. The interviews demonstrate that attendance data may indicate that a student is struggling but human intervention, such as a tutorial, can improve student wellbeing. Thus, this investigation has clearly shown that collecting and analyzing attendance data and using it to prompt a wellbeing intervention can have a significant and positive impact on student wellbeing. It suggests that attendance monitoring encourages student attendance which in turn positively impacts staff and student wellbeing and as such, should be implemented across the sector.

The limitations of this investigation are the size of the sample and the profile of participants as it was conducted within one specific school with a distinct profile of students and with experienced staff. For example, this has meant that most of the participants are female and none are care leavers. Therefore, future studies are recommended to draw on a wider range of participants to enable further exploration of the PERMA model within different contexts. Future studies could also explore additional elements of the PERMA model, such as student achievement (assignment grades), positive emotions (student participation in course feedback) or meaning (student involvement in extracurricular activities). Additionally, future studies could be conducted by researchers that do not have an existing relationship with participants, as this power dynamic may have affected responses in this study.

Conclusion

The first objective of this investigation was to understand student and staff attitudes toward the SHTM student attendance policy which has been achieved through analyzing data from staff and student focus groups, and interviews with students known to the SPT due to their high absence rate. The second objective, to identify reasons for student absences, has been met through a review of literature and an analysis of the research data which largely confirms that students miss classes for many reasons including tiredness, uninspiring lecturers and childcare responsibilities. The data from this investigation suggests that work commitments, timetabling and the belief that students can catch up are the most common reasons for being absent. The impact of student absence was felt by students and staff in several ways, but notably how it impacts group work and group assessment, and leads to staff feeling unmotivated and reluctant to invite guest speakers to lectures.

The data did not indicate that absence leads to staff feeling unliked, lonely or lacking in confidence which has been suggested by Macfarlane (Citation2013). However, as a small number of experienced staff took part, this is likely to have influenced the results and future studies with less experienced staff may provide more wide-ranging outcomes. Nonetheless, the results do indicate that staff and students are strongly in favor of attendance monitoring which demonstrates a partial achievement of the fourth objective of this research project (to evaluate the impact of the SHTM student attendance policy on staff wellbeing). The interview data contributes to the third objective (to evaluate the effectiveness of registers as a tool for wellbeing intervention) as it demonstrates the effectiveness of using registers to identify students that may be struggling. All of the interviewees were students that had been referred to and met with the SPT to discuss their absence and all confirmed that this was at least in part, a positive and welcome intervention. Most interviewees discussed how the intervention made them feel cared for, with some stating that this contributed to their feeling of belonging to the university community. Some interviewees described how the intervention led to positive changes to their academic experience, in the form of feeling supported, less isolated, less anxious and having an improved sense of wellbeing. The data raises questions about students attitudes toward surveillance and how learning analytics are used to support them, and it suggests that personalized and streamlined communication is key to student engagement.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Advance HE. (2023). Students’ engagement with their studies has largely bounced back to pre-pandemic levels, says new report. Retrieved July 31, 2023, from https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/news-and-views/students-engagement-their-studies-has-largely-bounced-back-pre-pandemic-levels-says

- Ahern, S. J. (2020). Making a #Stepchange? Investigating the alignment of learning analytics and student wellbeing in United Kingdom Higher Education Institutions. Frontiers in Education, 5. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2020.531424

- Allison, L., Bassnett, S., & Yale, A. (2022). Are Personal Tutors an Anachronism? Retrieved July 31, 2023, fromhttps://www.timeshighereducation.com/depth/are-personal-tutors-anachronism

- Baik, C., Larcombe, W., & Brooker, A. (2019). How universities can enhance student mental wellbeing: The student perspective. Higher Education Research & Development, 38(4), 674–687. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2019.1576596

- Bati, A. H., Mandiracioglu, A., Orgun, F., & Govsa, F. (2013). Why do students miss lectures? A study of lecture attendance amongst students of health science. Nurse Education Today, 33(6), 596–601. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2012.07.010

- Blackman, T. (2020). What affects student wellbeing?. Higher Education Policy Institute. Retrieved July 31, 2023, from https://www.hepi.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/HEPI-Policy-Note-21-What-affects-student-wellbeing-13_02_20.pdf

- Bowyer, J., & Chambers, L. (2017). Evaluating blended learning: Bringing the elements together. Research Matters: Cambridge University Press & Assessment.

- Coffey, J. K., Wray-Lake, L., Mashek, D., & Branand, B. (2016). A multi-study examination of well-being theory in college and community samples. Journal of Happiness Studies, 17(1), 187–211. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-014-9590-8

- Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2018). Research methods in education. Routledge.

- Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2011). Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Sage Publications.

- Denovan, A., & Macaskill, A. (2017). Stress and subjective well-being among first year UK undergraduate students. Journal of Happiness Studies, 18(2), 505–525. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-016-9736-y

- Eloff, I., O’Neil, S., & Kanengoni, H. (2021). Students’ well-being in tertiary environments: Insights into the (unrecognised) role of lecturers. Teaching in Higher Education, 28(7), 1777–1797. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2021.1931836

- FE News. (2023). 30% of students unable to secure part-time jobs due to poor university timetable. Retrieved July 31, 2023, from https://www.fenews.co.uk/student-view/30-of-students-unable-to-secure-part-time-jobs-due-to-poor-university-timetable

- Gray, C. C., & Perkins, D. (2019). Utilizing early engagement and machine learning to predict student outcomes. Computers & Education, 131, 22–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2018.12.006

- Hamilton Bailey, T., & Phillips, L. J. (2016). The influence of motivation and adaptation on students’ subjective well-being, meaning in life and academic performance. Higher Education Research & Development, 35(2), 201–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2015.1087474

- Hill, J., Healey, R. L., West, H., & Dery, C. (2019). Pedagogic partnership in higher education: Encountering emotion in learning and enhancing student wellbeing. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 45(2), 167–185. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098265.2019.1661366

- Jones, E., Priestly, M., Brewster, L., Wilbraham, S. J., Hughes, G., & Spanner, L. (2021). Student wellbeing and assessment in higher education: The balancing act. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 46(3), 438–450. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2020.1782344

- Kassarnig, V., Bjerre-Nielsen, A., Mones, E., Lehmann, S., Lassen, D. D., & Andrade, P. B. (2017). Class attendance, peer similarity, and academic performance in a large field study. PLOS ONE, 12(11), e0187078. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0187078

- Kern, M. L., Waters, L. E., Adler, A., & White, M. A. (2015). A multidimensional approach to measuring well-being in students: Application of the PERMA framework. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 10(3), 262–271. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2014.936962

- Kitzinger, J. (1995). Qualitative research: Introducing focus groups. British Medical Journal, 311(7000), 299–302. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.311.7000.299

- Leite, M., Fernandes, J., Carvalho, K., Pina-Zallio, M., Piccolo Verza, R., & Prazeres Goncalves, M. (2023). Fear of returning to face-to-face classes in times of Covid-19: A Cross country comparison. Journal of School and Educational Psychology, 3(1), 49–65. https://doi.org/10.47602/josep.v3i1.25

- Macfarlane, B. (2013). The surveillance of learning: A critical analysis of university attendance policies. Higher Education Quarterly, 67(4), 358–373. https://doi.org/10.1111/hequ.12016

- Maxwell, R., Draper, M., & Morris, I. (2023). Current challenges in personal tutoring and the role of data as part of the solution. Roundtable discussion UK Advising and Tutoring (UKAT) Annual Conference 2023, Swansea University, UK.

- McGaughey, F., Skead, N., Elphick, L., Wesson, M., & Offer, K. (2019). What have we here? The relationship between law student attendance and wellbeing. Monash University Law Review, 45(3), 695–720.

- Newman‐Ford, L., Fitzgibbon, K., Lloyd, S., & Thomas, S. (2008). A large‐scale investigation into the relationship between attendance and attainment: A study using an innovative, electronic attendance monitoring system. Studies in Higher Education, 33(6), 699–671. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070802457066

- O’Callaghan, F. V., Neumann, D. L., Jones, L., & Creed, P. A. (2017). The use of lecture recordings in higher education: A review of institutional, student, and lecturer issues. Education and Information Technologies, 22(1), 399–415. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-015-9451-z

- Offer, K., Wesson, M., McGaughey, F., Skead, N., & Elphick, L. (2020). “Why bother if the students don’t” the impact of declining student attendance at lectures on law teacher wellbeing. In A. Sifris & J. Marychurch (Eds.), Wellness for law: Making wellness core business (pp. 65–76). LexisNexis Butterworths.

- O’Keeffe, P. (2013). A sense of belonging: Improving student retention. College Student Journal, 47(4), 605–613.

- Picton, C., Kahu, E. R., & Nelson, K. (2018). “Hardworking, determined and happy”: First-year students’ understanding and experience of success. Higher Education Research & Development, 37(6), 1260–1273. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2018.1478803

- Pollard, E., Vanderlayden, J., Alexander, K., Borkin, H., & O’Mahony, J. (2023). Student mental health and wellbeing: Insights from higher education providers and sector experts. Department for education. Retrieved July 31, 2023, from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/996478/Survey_of_HE_Providers_Student_Mental_Health.pdf

- Riva, R., Freeman, R., Schrock, L., Jelicic, V., Ozer, C.-T., & Caleb, R. (2020). Student wellbeing in the teaching and learning environment: A study exploring student and staff perspectives. Higher Education Studies, 10(4), 103–115. https://doi.org/10.5539/hes.v10n4p103

- Sahin, M. (2023). A Study in absenteeism of university students. International E-Journal of Educational Studies, 7(13), 75–88. https://doi.org/10.31458/iejes.1223043

- Saldaña, J. (2016). The coding manual for qualitative researchers (3rd ed.). Sage.

- Seligman, M. E. P. (2011). Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. Free Press.

- Sloan, D., Manns, H., Mellor, A., & Jeffries, M. (2020). Factors influencing student non-attendance at formal teaching sessions. Studies in Higher Education, 45(11), 2203–2216. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1599849

- Smith, K. (2005). Measuring the impact of tourism on resident well-being: The role of social capital. Annals of Tourism Research, 32(3), 589–608. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2004.10.001

- Solutionpath. (2023). Learning analytics: Adopting a data mindset and an institutional approach to student success using student engagement analytics [white paper]. Retrieved February 13, 2024, from https://www.solutionpath.co.uk/insights/adopting-a-data-mindset-to-student-success-using-student-engagement-analytics/

- World Health Organization. (2022). Mental health. Retrieved March 6, 2023, from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-strengthening-our-response#:~:text=Mental%20health%20is%20a%20state,and%20contribute%20to%20their%20community

Appendix.

Focus Group and Interview Questions

Focus Group Questions (students)

Are you a carer/care leaver?

Do you have a full or part time job?

Do you live on campus?

Is attendance monitoring needed?

Should attendance be voluntary?

Why do you attend classes?

Why have you missed classes?

Has your learning been impacted by the nonattendance of other students?

Focus Group Questions (staff)

Should student attendance be voluntary?

Attendance monitoring means treating students as children who are incapable of independence of thought, judgment or maturity – do you agree?

I don’t see the need for students to attend in person when we can use lecture recording – do you agree?

Is taking a register a burden?

Have you experienced low attendance at your classes?

If so, why do you think this was?

How did this make you feel?

Low attendance impacts upon the energy in the classroom – do you agree?

Low attendance impacts the lecturer’s ability to engage with students – do you agree?

Low attendance diminishes the quality of teaching – do you agree?

Low attendance diminishes the enjoyment the lecturer gets from teaching – do you agree?

Have you ever canceled or changed plans for trips or guest lecturers due to concerns about low attendance?

Student Interview Questions

Why did you not attend classes?

Has not attending negatively impacted your wellbeing or mental health?

When you were referred to the SPT, how did this make you feel?

Did anything change after meeting the SPT?