ABSTRACT

This study investigates the influence of service, political, governance, and financial characteristics on municipalities’ choices of four service delivery modes (in-house, inter-municipal cooperation, municipality-owned firm, and private firm) in the Dutch local government setting. The results show that as a service involves more asset specificity and more measurement difficulty, the likelihood that municipalities contract this service out is lower. Also, although some differences in preferences are found between boards of aldermen and municipal councils, for both political bodies a more right-wing political orientation is shown to be positively related to privatization of services. Furthermore, contracting out is also shown to be related to the governance model of municipalities, as services of municipalities that (in general) put relatively less emphasis on input, process, and output performance indicators, and more on outcome performance indicators, are more likely to be privatized. Finally, the results also show that services of municipalities that have a better financial position are less likely to be contracted out to a private firm.

INTRODUCTION

The delivery of public services has recently been the subject of major reforms, in particular at the local government level. Recent research in the Netherlands, the country on which this study focuses, has, for example, shown that half of the municipalities have switched their mode of garbage collection between 1998 and 2010, with two-thirds of the switches being towards outside production, mostly by contracting out (Gradus et al. Citation2014). Furthermore, research has also shown that municipalities are increasingly using other ways of delivering local services (Pérez-López et al. Citation2015). Whereas the main distinction made was traditionally between in-house and out-house (privatized) service delivery modes, other forms, such as inter-municipal cooperation and municipality-owned firms, can now be commonly observed. Research shows that a constellation of factors seems to be relevant to explain municipalities’ choices of service delivery modes. The focus in this literature is increasingly taking a broader perspective where, in addition to transaction cost theory, other theoretical approaches, such as public choice and political patronage, are chosen for investigating the determinants of these choices and their effectiveness (e.g., López-de-Silanes et al. Citation1997; Dijkgraaf et al. Citation2003; Levin and Tadelis Citation2010). More recent studies, such as Warner and Hefetz (Citation2012), not only take service characteristics into account, but also characteristics of the municipality and its environment, such as management, market, and socio-economic factors. Whereas empirical findings from studies using a transaction cost theory approach seem to be relatively consistent in that asset specificity is negatively and ease of measurement is positively related to the level of contracting out, findings on other aspects seem to be less consistent.

In this article, we aim to add to this literature by analyzing the influence of a number of complementary, theory-based factors that may explain the differences in choices of service delivery modes in the Dutch local government setting. We distinguish between four service delivery modes (in-house, inter-municipal cooperation, municipality-owned firm, and private firm) and focus on 12 municipal services. For our analysis, we use data that have been collected from multiple sources and take both service and municipal characteristics into account. For the service characteristics, we follow transaction cost theory and expect that the specificity of assets used for providing services as well as ease of measurement are potentially important for explaining differences in service delivery modes. Our analysis reveals that, as a service involves more asset specificity and more measurement difficulty, the likelihood that municipalities contract this service out is lower (cf. Brown and Potoski Citation2003; Citation2005). For the municipal characteristics, we focus on political, governance, and financial factors, but also control for socio-economic factors. Following Elinder and Jordahl (Citation2013), we distinguish between general political preferences as expressed by the voters (in our case, represented by the members of the municipal council) and those of the ruling parties (in our analysis, the aldermen). Although we find some differences in preferences between boards of aldermen and municipal councils, for both political bodies a more right-wing political orientation is shown to be positively related to privatization of services. For the governance characteristics, we analyze the relative emphasis that is put on different types of performance indicators, where we distinguish between input, process, output, and outcome indicators. We expect that, when a municipality puts more emphasis on the use of output and outcome indicators, it may be more willing to contract services out to an outside provider, as the use of these indicators signals that a municipality has moved beyond its own administrative system and makes use of markets and networks for policy execution. Our analysis provides some evidence that contracting out is indeed related to the governance model of municipalities, as services of municipalities that (in general) put relatively less emphasis on input, process, and output indicators, and more on outcome indicators, are more likely to be privatized. Finally, for the financial characteristics, the results show that services of municipalities that have a better financial position are less likely to be contracted out to a private firm.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows. The next section reviews recent literature on determinants of municipalities’ choices of service delivery modes. Next, the research methods used are described. This is followed by a section in which the results are presented and discussed. The final section summarizes and concludes.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

Municipalities’ Choices of Service Delivery Modes and Service Characteristics

From the late 1970s and early 1980s onwards, the privatization of local service delivery has become an issue in many OECD (and other) countries (Pollitt and Bouckaert Citation2004).Footnote1 This measure was often part of a package of reforms, which, in the literature, is labelled “New Public Management” or its abbreviation, NPM (Hood 1995). NPM proposes, among other things, to make relationships between and within units more contract-based and to hold managers more explicitly accountable for realized outputs and outcomes.

Contracting out of local services has been discussed and researched considerably in academia since the 1980s. The first studies were inspired by public choice theory. According to this theory, monopolization of services will result in overproduction and inefficiencies, whereas contracting out will lead to lower spending (Boyne Citation1998). There has been some empirical evidence for these hypotheses; for example, for Italian local utilities where (partial) privatization has been shown to (significantly) decrease total costs (Garrone et al. Citation2013). Transaction cost theory relaxed this positive view on contracting out and basically argues that, in some cases, the cost savings of contracting out may be less than the costs that are associated with contracting, which are called the transaction costs. These costs not only include administrative costs, but also the costs from incomplete contracts stemming from monitoring and control activities (Williamson 1997). Using data from 1,586 U.S. municipal and county governments, Brown and Potoski (Citation2003) showed that service characteristics are important for understanding the nature of transaction costs and the contracting-out process.Footnote2 Following Williamson (Citation1981), they analyzed two types of service characteristics—asset specificity and service measurability. Asset specificity refers to whether specialized investments are required to produce the service (Brown and Potoski Citation2003, 444). Transaction cost theory hypothesizes that if a service requires high asset specific investments, this will create a barrier for service providers. Service measurability refers to how difficult it is for the contracting organization to measure the outcomes of the service, to monitor the activities required to deliver the service, or both (Brown and Potoski Citation2003, 445). If services can be easily and accurately measured, the risk of unseen vendor non-performance or negligence is lower than under the opposite condition. Brown and Potoski (Citation2003) found that higher asset specific investments are associated with more in-house production and less contracting out.Footnote3 Furthermore, they found that service measurability is positively associated with outside contracting. Based on their arguments, we hypothesize that:

Services involving more asset specificity are less likely to be contracted out to a private or a municipality-owned firm.

Services involving more measurement difficulty are less likely to be contracted out to a private or a municipality-owned firm.

Political Characteristics

The influence of political characteristics on contracting-out decisions is one of the most researched, but also most inconclusive, issues in this area. The common theoretical expectation is that conservative parties are more in favor of privately delivered services than those of socialist or social democratic ideologies (Petersen et al. Citation2015).Footnote4 However, this hypothesis is not confirmed in all empirical studies (Bel and Fageda Citation2007), where most of these studies focus on garbage collection. Based on a meta-regression, Bel and Fageda (Citation2009) have shown that the influence of political ideology may be context specific, in that they found that ideology plays a larger role in bigger U.S. cities as well as (to a lesser extent) in European cases. Cuadrado Ballesteros et al. (Citation2013) showed, in Spain, that special forms of contracting out, such as corporatization and foundations, are more likely to be initiated by right-wing politicians. For Spanish waste collection, Plata-Díaz et al. (Citation2014) confirmed the view that left-wing political parties prefer to use public rather than private waste management forms. Rodrigues et al. (Citation2012) extend this analysis by incorporating the issue of political instability. They showed that higher political instability leads to the externalization of services, thereby shifting responsibility to external agents. For the Netherlands, Dijkgraaf et al. (Citation2003) found only weak evidence for ideological motivation of choices between public and private waste collectors. Analyzing changes in service delivery modes for garbage collection in Dutch municipalities, Gradus et al. (Citation2014) found that ideology indeed matters: conservative liberals and orthodox Protestants are in favor of changing, particularly towards the market and privatization, whereas social democrats are against change, interestingly also towards privatization and reverse privatization.

In this article, we extend this analysis for the Netherlands by using a different operationalization of the political variables and by capturing both the political preferences of the voters (represented by the (weighted) share of different parties in the municipal council) and those of the ruling political parties (represented by those of the aldermen) in this contracting-out decision.Footnote5 In a sense, we follow Elinder and Jordahl (Citation2013), who distinguish three models of how political ideology influences contracting-out decisions.Footnote6 The Citizen Candidate model hypothesizes that politicians are motivated to run for office by a desire to implement their own preferred policy, and that citizens vote for the party to whom they wish to entrust the power to govern for the upcoming electoral period. Therefore, this assumes that policy choices will depend on the preferences of the ruling parties; in our case, the political parties that provide the aldermen. Here, the expectation is that right-wing aldermen will use contracting out to a larger extent than left-wing aldermen. The Downsian model predicts that policy outcomes will be determined by the preferences of the median voter, represented in our research setting by the members of the municipal council, and not by the preferences of the ruling parties. Finally, the Patronage model basically argues that there may be a distance between voters’ and politicians’ preferences as support for political decisions may play a role.

As far as contracting out is concerned, politicians may derive significant benefits from in-house production, such as using local employees. This also leads to increased support from public employee unions (López-de-Silanes et al. Citation1997).Footnote7 Using this political framework, Elinder and Jordahl (Citation2013) analyzed the local use of private contractors for primary education in Sweden. They found that municipalities with a right-wing majority have a higher preference for contracting out than municipalities with a left-wing majority, supporting the Citizen Candidate model. The other models were not supported.

Gradus and Budding (2016) found some evidence for an ideological motivation for changing the mode of garbage collection by Dutch municipal councils and aldermen. Conservative liberal councilmembers are in favor of change, particularly towards the market and privatization, whereas social democrat councilmembers are against change. For conservative liberal aldermen, they also found negative effects for changing from the market and reverse privatization, whereas for other political parties there were no or only weak effects. In sum, although not entirely conclusive, most studies have found that political bodies dominated by right-wing politicians prefer contracting out to a private firm more than political bodies dominated by left-wing politicians. Accordingly, we expect that:

Services of municipalities of which the political bodies (i.e., the board of aldermen and the municipal council) have a more right-wing political orientation are more likely to be contracted out to a private firm.

Governance Characteristics

As argued earlier, from the late 1970s and early 1980s onwards, the privatization of local service provision has become an issue in many countries (Pollitt and Bouckaert Citation2004), often labeled under the umbrella of “New Public Management” or NPM. NPM embraces a large number of reforms. For Dutch municipalities, the transition from input to output control and the autonomization of departments are among the most important changes (Van Helden and Jansen Citation2003). As previous research has shown that NPM reforms are often implemented in a specific sector in the form of a package, we expect these reforms to be interrelated. Also, following Girth (Citation2014), we expect that privatization decisions may be partly driven by earlier experiences with or preference for market-based approaches. We capture this relationship between privatization and other management reforms by looking at the governance logic of the municipalities in our study. With governance we refer to “the processes by which organizations are directed, controlled, and held to account” (IFAC Citation2001, 1).

Wiesel and Modell (Citation2014) describe three governance logics that are visible in public sector organizations: the Progressive Public Administration (PPA), New Public Management (NPM), and New Public Governance (NPG) logics. Under the traditional Progressive Public Administration (PPA), the focus is on compliance with rules and regulations. The preferred system for service delivery is by using one’s own unified government departments. Control is exercised by focusing on the inputs and the intra-organizational processes. In the (late) 1980s, a shift was made (in the Netherlands, but also elsewhere) from PPA to New Public Management (NPM), but the specific elements of NPM varied among (government levels of) countries (Groot and Budding Citation2008). NPM proposes to put service delivery more at a distance by contracting out activities. Under this governance logic, competitive markets are used for service delivery and the control focus is on outputs. From the second half of the 1990s onwards, new developments can be observed which are represented by names such as “Public Value” (PV) and “New Public Governance” (NPG), which (among others) propose that government activities should be performed in a network of actors. Here, the control focus is more on outcomes (Wiesel and Modell Citation2014). A recent empirical study among several large Dutch municipalities provides some evidence that municipalities differ in the extent to which they have implemented elements of PPA, NPM, and NPG (see Blokker et al. Citation2014).Footnote8

We will operationalize the differences in control focus by analyzing the types of performance indicators (input, process, output, and outcome) as reported in the annual reports of the municipalities. We expect that, when more emphasis is put on output and outcome indicators, municipalities are more experienced with and willing to move beyond their own administrative system—in our case, to contract out services. Therefore, we hypothesize that:

Services of municipalities that (in general) put relatively less emphasis on input and process performance indicators, and more on output and outcome performance indicators, are more likely to be contracted out to a private or a municipality-owned firm.

Financial Characteristics

The relationship between financial conditions and the decision to contract out the delivery of public services has been a matter of strong contention in the literature. The dominant view in public administration literature is that adverse financial situations lead to the adoption of external arrangements rather than in-house hierarchical solutions (López-de-Silanes et al. Citation1997; Dijkgraaf et al. Citation2003; Brown et al. Citation2006, Levin and Tadelis Citation2010). However, some empirical findings suggest that contracting out at the local level may actually be less prevalent if there is financial stress (Warner and Hefetz Citation2012; Rodrigues et al. Citation2012). Rodrigues et al. (Citation2012) point out that local public sector unions or other interest groups may be especially vigorously opposed to contracting out during economic decline in fiscal crises. So, this issue is still debated from a theoretical point of view. As for the Netherlands, a recent study by Gradus and Budding (Citation2016) also showed some evidence that municipalities with high debt have a higher probability to contract out. Overall, it seems that municipalities with a weak financial position are more likely to choose the most market-based solutions. Accordingly, we hypothesize that:

Services of municipalities that have a better financial position are less likely to be contracted out to a private firm.

RESEARCH METHODS

Research Setting

Local government in the Netherlands is considered the most important and visible level of sub-national government in the Dutch decentralized unitary state (Hendriks and Tops Citation2003). It has an autonomous position and can initiate local policies it considers important for the local community. This freedom is constrained by general rules and requirements set by national and regional governments. However, as Breeman et al. (Citation2015) have shown, municipalities are mainly busy with executing policies that are delegated by higher levels of government. This is not simply blind implementation, however, but co-governance as, according to Breeman et al. (Citation2015, 27), “municipalities have a certain leeway to translate and shape a policy to the specific needs of the municipality.” This setting provides us the opportunity to analyze differences in service delivery modes while the activities to be performed are more or less comparable among the municipalities.

The political system in Dutch municipalities can be described as a multiparty political system. Its main elements are the municipal council and the board of mayor and aldermen. The board of mayor and aldermen is expected to focus its attention on the daily management of the municipality and the bureaucracy; for the empirical setting on which we are focusing, the executive power of the mayor is limited.Footnote9 The composition of the municipal council directly depends on the results of the municipal election; there are no formal election thresholds. The number of aldermen varies according to the number of inhabitants. Since 2002, aldermen do not have to be members of the municipal council, although they need the support of a council majority. Fleurke and Willemse (Citation2006, 75) remark that “it is widely believed that the Dutch boards are the prime municipal decision bodies” because “It is there that strategic and operational decision-making takes place and bureaucratic spheres of influence converge.”

Sample and Data Collection

The data used in this study have been collected from multiple sources. First, we conducted a multi-purpose survey among 426 Dutch municipalities in the period from December 2010 to February 2011.Footnote10 In this survey, we asked the respondents, who all occupy a senior-level financial management position, how their municipality has organized 12 municipal services. A total of 87 municipalities returned the questionnaire, of which one was unusable, providing a usable response rate of 20.2%. Tests show that the responding municipalities are representative for our survey population, since they have a similar number of inhabitants and are from similar regions as the non-responding municipalities.Footnote11 Second, we conducted an additional survey among an expert panel of 30 municipal financial managers in the period December 2013 to January 2014, in which we asked them to rate the 12 municipal services on two important transaction cost characteristics—asset specificity and measurement difficulty—similar to the approach followed by Brown and Potoski (Citation2003; Citation2005). In total, 24 (80.0%) of these managers responded to this second survey. Third, we collected data on the political, financial, and socio-economic characteristics from public archival sources. Finally, we collected data on the reported number of formulated objectives and used performance indicators, which we use to measure the governance characteristics, from the annual reports for 2010 of the 86 municipalities that responded to our initial survey. After removing observations with missing values for one or more of the variables, we had a dataset of 868 municipality-service observations available for the analyses reported in this article.Footnote12

Measures

Institutional Forms

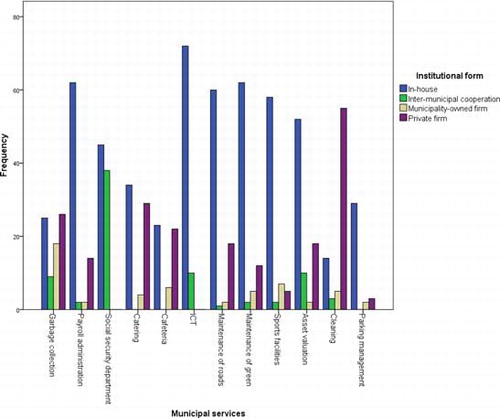

In this study, we focus on 12 municipal services, ranging from “garbage collection” to “parking management” (see Figure ).Footnote13 These services are mainly internal facilitating tasks and external service delivery tasks. We choose these particular services as previous studies have shown that these are most often subject of contracting-out decisions in the Dutch context (Ter Bogt Citation2008; Wassenaar 2011).Footnote14 As Ter Bogt (1999) indicates, a spectrum of organizational forms for public services delivery can be observed. In this study, we are interested in whether Dutch municipalities provide these services themselves, in cooperation with neighboring municipalities,Footnote15 or whether they contract them out to outside (municipality-owned or private) firms.Footnote16 Consistent with Ter Bogt (1999), we believe that autonomization is not a unidimensional construct, in that different factors (e.g., legal, public administrative, and economic factors) play a role in distinguishing levels of autonomization. From a legal perspective, in-house production and inter-municipal cooperation are subject to public law, whereas a municipality-owned firm and a private firm are subject to private law (e.g., Gradus et al. Citation2014). Municipal-owned firms thus operate under Dutch private law, while their shares are fully owned by municipalities.

The data show that, on average, 61.8% of the 12 services is organized in-house, 8.9% carried out within an inter-municipal cooperation, 6.1% contracted out to a municipality-owned firm, and 23.3% contracted out to a private firm (see also Table ). Figure shows remarkable differences among the 12 services. For example, for garbage collection, all four forms are used to a considerable extent. Contracting out to a private firm is, with 33.3%, the most common institutional form,Footnote17 but contracting out to a municipality-owned firmFootnote18 and inter-municipal cooperation are also often used. For the other municipal services, contracting out to a private firm is less common. Only catering, cafeteria, and cleaning are relatively more frequently contracted out to a private firm than garbage collection. Remarkably, 71.4% of the municipalities contract out their cleaning services to a private firm.

TABLE 1 Cross-Tabulation of Municipal Service by Institutional Form, and Average Asset Specificity and Measurement Difficulty Ratings

Service Characteristics

In US-based studies, the information that relates to transaction cost theory explanations for contracting out was collected by surveying municipal managers (e.g., Brown and Potoski Citation2005; Levin and Tadelis Citation2010). Similar to Brown and Potoski (Citation2005), we are interested in two characteristics: asset specificity and measurement difficulty.Footnote19 In December 2013 to January 2014,Footnote20 we sent a questionnaire to an expert panel of 30 municipal financial managers.Footnote21 In total, 24 (80.0%) of these managers responded to this survey. In the questionnaire, we provided an extensive definition of the two transaction cost characteristics, which we based on those used by Brown and Potoski (Citation2005), and asked respondents to rate each service on a five-point Likert scale for both asset specificity and measurement difficulty. The measurement difficulty scale was anchored by the words very easy (scored 1) and very difficult (scored 5). Similarly, the asset specificity scale was anchored by the words very low (scored 1) and very high (scored 5). We averaged the ratings across respondents to create an overall score for asset specificity and measurement difficulty for each service. Table reports the average service characteristic ratings for each of the 12 services.

As Table indicates, there is considerable dispersion on the average service characteristic ratings among the 12 services. Interestingly, at the high end, “garbage collection” received the highest asset specificity rating (4.04), whereas “Information and Communication Technology (ICT)” received the highest measurement difficulty rating (3.04). In Dutch local government, there is much discussion about the cost-effectiveness of ICT, implying that municipalities find it hard to assess whether invested money pays out dividend. At the low end are cleaning, with a score of 1.50 for asset specificity and 1.71 for measurement difficulty, and cafeteria, with a score of 1.91 for asset specificity and 1.55 for measurement difficulty. Overall, consistent with Brown and Potoski (Citation2005), the two service characteristics are positively correlated (r = 0.426), indicating that services that are relatively difficult to measure also tend to involve more asset specificity.Footnote22

Political Characteristics

As political characteristics, we focus on the ideological (left-right) orientation of both the aldermen (who, together with the mayor, form the board of mayor and aldermen; BMA) and the municipal council (MC) of the municipalities. Data about these political characteristics were collected from the Gids Gemeentebesturen (Guide Municipal Boards), which is yearly published by the Vereniging van Nederlandse Gemeenten (Association of Dutch Municipalities), as well as by an Internet search. To measure the ideological (left-right) orientation of the municipalities’ aldermen and municipal council, we used the 2010 Chapel Hill Expert Survey (CHES) dataset (www.chesdata.eu), which provided us with ratings on a scale ranging from “extreme left” to “extreme right” for all Dutch national political parties.Footnote23 For each municipality, we calculated the left-right orientation of the aldermen and the municipal council by weighting the proportion of members from the different political parties that are part of these local political bodies by these Chapel Hill ratings. Aldermen from so-called independent local parties were excluded from the calculations because it is difficult to rate them on a left-right scale (Boogers and Voerman Citation2010).

Governance Characteristics

As argued earlier, given that the governance model of a municipality cannot be observed directly and, as far as we know, an appropriate measurement instrument has not yet been developed, we proxy for this model by analyzing the (relative) emphasis that municipalities put on different types of performance indicators. Also, in additional analyses, we also use an alternative proxy by analyzing the (absolute) number of formulated objectives and used performance indicators (of different types). Performance indicators can be divided into different categories, such as input, process, output, and outcome indicators. This classification is based on a model that assumes that institutions and/or programs are set up to address some specific socio-economic need(s) (Pollitt and Bouckaert Citation2004). In accordance with this model, objectives concerned with these needs are established, and inputs (staff, buildings, resources) with which to conduct activities in pursuit of those objectives are acquired. These activities are part of processes that take place inside institutions in order to generate outputs (“products”), which then interact with the environment (in particular, with those individuals and groups to whom they are specifically aimed), leading to (intermediate and final) outcomes. Traditionally, public sector organizations have mainly focused on input and process indicators. However, with the widespread adoption of the NPM and NPG governance logics, many of these organizations have increasingly shifted their focus towards using output and (especially under NPG) outcome indicators.

In order to obtain the necessary data for this study, we gathered the annual reports for 2010 of the 86 municipalities that responded to our initial survey. Two research assistants identified the reported number of formulated objectives and used performance indicators in these annual reports, distinguishing between input, process, output, and outcome indicators (e.g., Hatry Citation2006; Bouckaert and Halligan Citation2008). In order to secure inter-rater reliability, the coding took place in multiple rounds; after each round, a session was held between the research assistants and one of the authors of this article in order to discuss the operationalization of the variables and the coding decisions. Next, in addition to, and based on, the number of formulated objectives and used performance indicators (of the four types), we calculated the (relative) emphasis put on the four types of performance indicators by dividing the number of indicators for each of these types by the total number of indicators (irrespective of their type). For the (absolute) number of formulated objectives and used performance indicators (of the four types), we calculated the natural log in order to improve their distribution.Footnote24

Financial Characteristics

We measure the financial position of the municipalities as the natural log of unreserved fund balance scaled by total assets where, before calculating the natural log, we added 1.0 in order to produce positive values for this variable.

Control Variables

In our empirical analyses, we control for a number of socio-economic characteristics: number of inhabitants, population density, number of people with unemployment benefits (per 1,000 inhabitants), and average income per household. We include number of people with unemployment benefits as a measure of labor market conditions. In general, we expect municipalities to be more inclined to provide services themselves if unemployment in a municipality is high, because choosing another institutional form would make it less likely that workers would be hired locally (cf. Gradus et al. Citation2014). The data for these variables are obtained from Statistics Netherlands. For the number of inhabitants and population density, we calculated the natural log in order to improve their distribution.

RESULTS

Descriptive Statistics

Table presents the descriptive statistics for the independent variables, both in total and per institutional form.Footnote25

TABLE 2 Descriptive Statistics Per Institutional Form

As observed in Table , the average scores for asset specificity and measurement difficulty are 2.572 and 2.281, respectively, which indicates that, on average, these variables both score between “low” and “average.” For both the aldermen (BMA) and the municipal council (MC), the average ideological (left-right) orientation score is about 0.57, which indicates that, on average, these local political bodies are somewhat more right-wing than left-wing oriented. The average emphasis that the municipalities put on the different types of performance indicators is 28.3% on input, 23.3% on process, 32.4% on output, and 15.9% on outcome indicators, respectively. As reflected by the large SDs, however, there are large differences among the municipalities in terms of these percentages. The average number of formulated objectives is about 56, and the average number of used input, process, output, and outcome indicators is about 11, 17, 21, and 11, respectively. Also, the average financial position score is 0.140. Finally, the average number of inhabitants is somewhat less than 42,500, the average population density is about 550 inhabitants per square kilometer, the average percentage of people with unemployment benefits is about 1.4%, and the average income per household is €34,709. Overall, the unconditional means per institutional form show no clear pattern (order), in that all forms score highest on at least one variable and lowest on another. In addition, for all but five of these variables, both the ANOVA and the Welch testFootnote26 show that the differences in unconditional mean scores among the four groups (institutional forms) are significant.

Model Estimation Results

We analyze the relationships between the service, political, governance, and financial characteristics and municipalities’ choices of the four service delivery modes (in-house, inter-municipal cooperation, municipality-owned firm, and private firm) by estimating a multinomial logit model (MNLM). In this analysis, we control for the four socio-economic characteristics and cluster standard errors by municipality based on the assumption that their choices of service delivery modes are independent across municipalities but not within them (cf. Carr et al. Citation2009; Levin and Tadelis Citation2010). Also, we conduct separate analyses for the two political variables because they have a common cause (the outcomes of an election) and are therefore inherently correlated. Table reports the results from the MNLM estimation and Table reports estimates of the marginal effects.Footnote27

TABLE 3 Multinomial Logit Model Results

TABLE 4 Marginal Effects

For the service characteristics, reported in Table , the results show that, as a service involves more asset specificity, the likelihood increases that municipalities choose to perform this service within a municipality-owned firm (as opposed to in-house), and the likelihood decreases that municipalities choose to perform this service within a private firm (as opposed to within a municipality-owned firm). The marginal effects, reported in Table , indicate that, compared to the other institutional forms, on average, a standard deviation increase in asset specificity increases the probability of performing the service within a municipality-owned firm by 0.035, while decreasing the probability of performing the service within a private firm by 0.039. This latter effect supports our first hypothesis (H1) and is consistent with the argument that municipalities are reluctant to externalize high asset-specific services to a private firm in order to mitigate opportunistic behavior and path dependency (e.g., Brown and Potoksi Citation2005; Levin and Tadelis Citation2010). The effect for municipality-owned firms is somewhat different from what we expected, but could be explained by the relatively close relationship between such a firm and the municipality(ies) as its (their) owner(s). The results also show that, as a service involves more measurement difficulty, the likelihood increases that municipalities choose to perform it publicly, either in-house or within an inter-municipal cooperation. The marginal effects substantiate these findings and indicate that, on average, a standard deviation increase in measurement difficulty decreases the probability of performing the service within a municipality-owned firm or a private firm by, respectively, 0.030 and 0.117, hereby supporting our second hypothesis (H2). As the quantity and quality of a service can be measured less easily, contracting it out to either a municipality-owned or a private firm is less obvious.

For the political variables, the results show that municipalities with a more right-wing orientation of their aldermen prefer contracting out to a private firm above performing a service in-house, within an inter-municipal cooperation or within a municipality-owned firm. In a separate analysis, the results show that municipalities with a more left-wing orientation of their municipal council prefer inter-municipal cooperation above performing a service in-house, within a municipality-owned firm, or within a private firm.Footnote28 Overall, these results support those of earlier studies that have also shown that relatively left-wing-oriented municipalities seem to have a natural preference to perform municipal services in a public cooperation with other municipalities, whereas relatively right-wing-oriented municipalities have a natural preference to contract them out to a private party (Sundell and Lapuente Citation2012). Interestingly, however, the two political bodies are shown to have different preferences, which seems to be due to their different responsibilities. As the aldermen are the daily managers of the municipality, they may have a preference for either contracting out an activity completely, or doing this activity completely in-house. Municipal council members, on the other hand, may consider inter-municipal cooperation as a valuable alternative to contracting out, hereby maintaining political control and employment within the public sector. The marginal effects indicate that, on average, a standard deviation increase in the left-right orientation of aldermen increases the probability of performing the service within a private firm by 0.038, while decreasing the probability of performing the service in-house by 0.033.Footnote29 These findings support our third hypothesis (H3).

For the governance characteristics, the results indicate that the governance model of the municipalities, as proxied by the (relative) emphasis that they put on different types of performance indicators, is also related to their choices of service delivery modes. The likelihood that a service is performed within an inter-municipal cooperation or a private firm (as opposed to in-house) decreases as a municipality (in general) puts more emphasis on input, process, and output indicators, while this likelihood increases as the municipality (in general) puts more emphasis on outcome indicators. If this is the case, municipalities apparently require less direct control over the performance of the service and instead are mainly interested in its (intermediate and final) outcomes. Similarly, the likelihood that a service is performed within a municipality-owned firm (as opposed to in-house) decreases as a municipality (in general) puts more emphasis on input indicators, while the likelihood that a service is performed within a private firm (as opposed to a municipality-owned firm) decreases as a municipality (in general) puts more emphasis on process indicators. The marginal effects substantiate these findings and indicate that, on average and compared to the reference category (i.e., at the expense of the emphasis put on outcome indicators), a standard deviation increase in emphasis on input, process, and output indicators increases the probability of performing the service in-house by, respectively, 0.108, 0.075, and 0.050. Similarly, on average and compared to the reference category (i.e., at the expense of the emphasis put on outcome indicators), a standard deviation increase in emphasis on input, process, and output indicators decreases the probability of performing the service within an inter-municipal cooperation by, respectively, 0.029, 0.019, and 0.010. Finally, on average and compared to the reference category (i.e., at the expense of the emphasis put on outcome indicators), a standard deviation increase in emphasis on input, process, and output indicators decreases the probability of performing the service within a private firm by, respectively, 0.065, 0.059, and 0.044. These latter effects partly support our fourth hypothesis (H4) and show that municipalities that focus on outcomes seem to prefer the most market-based production. For a municipality-owned firm, we do not find results. Remarkably, however, we do not find this association for output indicators. This suggests that municipalities (in general) do not show a preference for the NPM governance logic, but rather show a greater preference for the NPG governance logic, which is in line with the results of Blokker et al. (Citation2014), who have shown that large Dutch municipalities seem to be focused more towards NPG than towards NPM.

For the financial characteristics, the results show that municipalities with a better financial position have a smaller likelihood to contract a service out to a private firm (rather than perform it either in-house or within a municipality-owned firm), while such firms have a greater likelihood to perform a service within a municipality-owned firm (rather than in-house). The marginal effects indicate that, on average, a standard deviation increase in financial position increases the probability of performing the service in-house or within a municipality-owned firm by, respectively, 0.020 and 0.015, while decreasing the probability of performing the service within a private firm by 0.032. Municipalities with more financial concerns are apparently more inclined to contract out to a private firm, supporting our fifth hypothesis (H5), and seem to have fewer opportunities to initiate municipality-owned firms. Overall, these results concur with those obtained earlier by Zafra-Gómez et al. (Citation2014).

Finally, for the socio-economic characteristics, the results show that there is a greater likelihood for smaller municipalities to perform a service within either an inter-municipal cooperation or a private firm rather than in-house, while, in larger municipalities, the likelihood of contracting it out to a private firm is greater than performing it within an inter-municipal cooperation, and the likelihood of contracting it out to a municipality-owned firm is greater (compared to the other three institutional forms). It seems that smaller municipalities can take advantage of economies of scale by inter-municipal cooperation (see also Dijkgraaf and Gradus Citation2013) or by contracting out to a private firm, while larger municipalities are typically more innovative and have more bureaucratic capacity to handle the technical and judicial complexities involved in municipality-owned firms. The marginal effects indicate that, on average, a standard deviation increase in the number of inhabitants increases the probability of performing the service within a municipality-owned firm by 0.097, while decreasing the probability of performing the service within an inter-municipal cooperation or within a private firm by 0.031 and 0.061, respectively. Table also shows that (compared to the other three institutional forms) contracting a service out to a private firm is more likely if there is a higher population density and if, as a consequence, there is some indication for economies of scope. Here, the marginal effects indicate that, on average, a standard deviation increase in population density increases the probability of performing the service within a private firm by 0.050, while decreasing the probability of performing the service in-house or within a municipality-owned firm by 0.032 and 0.012, respectively. Also, municipalities with more unemployment benefits have a smaller likelihood to perform a service within either an inter-municipal cooperation or a municipality-owned firm (rather than in-house) and a greater likelihood to contract out it to a private firm (rather than to perform it within either an inter-municipal cooperation or a municipality-owned firm). Municipalities with worse labor market conditions apparently are more inclined to provide services themselves (so that they themselves can decide which workers to hire)Footnote30 or to contract them out to a private firm (possibly after making contractual arrangements about which workers to hire). The marginal effects indicate that, on average, a standard deviation increase in unemployment benefits increases the probability of performing the service in-house or within a private firm by 0.036 and 0.011, respectively, while decreasing the probability of performing it within an inter-municipal cooperation or within a municipality-owned firm by 0.017 and 0.030, respectively. Finally, municipalities with a higher average income per household have a greater likelihood to contract a service out to a municipality-owned firm (rather than perform it either in-house or within a private firm). The marginal effects indicate that, on average, a standard deviation increase in average income per household increases the probability of performing the service within a municipality-owned firm by 0.028, while decreasing the probability of performing the service within a private firm by 0.027.

TABLE 5 Multinomial Logit Model Results Based on the Absolute Numbers

Additional Analyses

Given that municipalities may not only differ in the (relative) emphasis that they put on different types of performance indicators, but also in the (absolute) number of formulated objectives and used performance indicators, we have also estimated our model based on these characteristics to proxy for municipalities’ governance model (see Tables and ).Footnote31 Overall, we expect that, as municipalities (in general) formulate more objectives and use more output and outcome indicators, they are more oriented towards using governance principles as recommended by the NPM and NPG paradigms, rather than those recommended by the PPA paradigm. As discussed earlier, for this additional analysis, we measure these characteristics based on the natural log of the number of objectives and performance indicators as identified in the annual reports for 2010 of the municipalities.

TABLE 6 Marginal Effects Based on the Absolute Numbers

For all service, political, financial, and socio-economic characteristics, the results are similar to those of our main analysis, and all conclusions concerning the related hypotheses remain the same. For the governance characteristics, the results show that the likelihood that a service is performed within a municipality-owned firm (as opposed to the other three institutional forms) increases as a municipality (in general) formulates more objectives. Similarly, the likelihood that a service is performed within an inter-municipal cooperation (as opposed to either in-house or within a private firm) decreases as a municipality (in general) uses more input indicators. Furthermore, the likelihood that a service is performed within a private firm (as opposed to in-house or within an inter-municipal cooperation) increases as a municipality (in general) uses less process and more outcome indicators, while the likelihood that a service is performed within an inter-municipal cooperation (as opposed to in-house) also increases as a municipality (in general) uses more outcome indicators. The marginal effects indicate that, on average, a standard deviation increase in the number of objectives and outcome indicators decreases the probability of performing the service in-house by 0.041 and 0.073, respectively, whereas a standard deviation increase in the number of input and process indictors increases this probability by 0.031 and 0.063, respectively. Similarly, on average, a standard deviation increase in the number of input indicators decreases the probability of performing the service within an inter-municipal cooperation by 0.023, whereas a standard deviation increase in the number of outcome indictors increases this probability by 0.008. Also, on average, a standard deviation increase in the number of objectives increases the probability of performing the service within a municipality-owned firm by 0.044. Finally, on average, a standard deviation increase in the number of process indictors decreases the probability of performing the service within a private firm by 0.043, whereas a standard deviation increase in the number of outcome indictors increases this probability by 0.069. Overall, these findings are in line with those of the analyses based on the (relative) emphasis that municipalities put on the different types of performance indicators, and therefore also partly support our fourth hypothesis (H4).

CONCLUSIONS

This study investigates the influence of service, political, governance, and financial characteristics on municipalities’ choices of four service delivery modes (in-house, inter-municipal cooperation, municipality-owned firm, and private firm). The debate about privatization of municipal services such as garbage collection, cleaning, and parking management is shifting from an ideological debate to a more proper discussion of the institutional and economic factors that determine the mode of delivery (see also Hefetz et al. Citation2012). This study confirms this for the Netherlands, which is important, as the current fiscal crisis puts local services under further pressure. In addition, we discuss the feature of municipality-owned firms, which, compared to many other countries, are a relatively common institutional form in the Netherlands. Our analysis suggests an important role for transaction costs, due to asset specificity and measurement difficulty, in contracting-out decisions for Dutch municipal services, although, contrary to what we expected, we find that more asset specificity increases the likelihood of choices for municipality-owned firms. There can be some reasoning for this, as these public enterprises will have easy access to (public) funds, despite the fact that they are organized as firms (see also Gradus et al. Citation2014). In addition, political, governance, and financial characteristics also seem to play a role in choices of service delivery modes. We find that services of municipalities of which the political bodies (i.e., the board of aldermen and the municipal council) have a more right-wing political orientation are more likely to be contracted out to a private firm, whereas municipalities with a more left-wing orientation of these political bodies seem to prefer public forms. Moreover, we also find evidence that the governance model of municipalities, as proxied by the (relative) emphasis that they put on different types of performance indicators and the (absolute) number of such indicators that they use, is related to choices of service delivery modes. Municipalities that focus more on outcome indicators seem to prefer either inter-municipal cooperation or (even more so) contracting out to a private firm, whereas those that focus more on input or process indicators seem to prefer in-house production. For output indicators, we get some mixed results. Interestingly, municipalities that focus more on output indicators (in relative but not in absolute terms) are less likely to privatize. We provide some reasoning for this, based on a study by Blokker et al. (Citation2014), which shows that large Dutch municipalities (in general) seem to be focused more towards NPG than towards NPM, but we also leave this as a topic for future research. For the financial characteristics, we take the unreserved fund ratio and show that services of municipalities with a better financial position are less likely to be contracted out to a private firm. Finally, for the socio-economic characteristics, we find, among others, that smaller municipalities have a greater probability to perform a service within an inter-municipal cooperation or a private firm, and that higher local unemployment increases the likelihood of choices for in-house production, which is in line with the literature.

There are some limitations and thus also some avenues for future research that we would like to mention. First, we used cross-sectional data in our study, whereas longitudinal data would be preferable to be able to understand the dynamic nature of contracting-out decisions. Second, cost functions can be evaluated. In the literature, mainly costs of garbage collection are analyzed, but it is interesting to have a broader picture. Third, we did not take local (market) conditions into account, such as the service delivery mode used by neighboring municipalities (e.g., contracting out may be easier if neighboring municipalities also use out-house providers) and market concentration of private firms. Earlier research on Dutch garbage collection has shown that high concentration in regions increases costs and therefore (partly) offsets the advantage of contracting out (see Dijkgraaf and Gradus Citation2007; Gradus et al. 2016). Fourth, we proxy for the governance logics by analyzing the emphasis that is put on different types of performance indicators. Future research can also take additional proxies for embracing a certain governance logic into account, such as (for example) the elements of PPA, NPM, and NPG that Blokker et al. (Citation2014) have focused on. Fifth, other local services can be analyzed, as it would be interesting to investigate the issue of mixed and hybrid delivery modes, where organizations are owned jointly by a municipality and a private firm (Bel et al. Citation2014). As far as we know, however, empirical information on these delivery modes is currently lacking for the Netherlands, but they can be important for complex contracts in construction and infrastructure, as shown by Brown et al. (Citation2016). Despite these limitations, we believe that our study provides additional insight into the factors underlying municipalities’ choices of service delivery modes.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Martijn Schoute

Martijn Schoute ([email protected]) is assistant professor in the Department of Accounting at VU University Amsterdam. His research focuses on a wide variety of management accounting and public administration topics, and has been published in journals such as Behavioral Research in Accounting, The British Accounting Review, Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, and Journal of Management Accounting Research.

Tjerk Budding

Tjerk Budding ([email protected]) is senior lecturer in Public Sector Accounting at VU University Amsterdam. He is co-author of the book Public Sector Accounting, which was published by Routledge in 2014. Tjerk Budding is a member of the scientific committee of the International EIASM Public Sector Conferences and member of the CIGAR Board. His research interests are cost analysis, cost accounting, performance management, and financial reporting.

Raymond Gradus

Raymond Gradus ([email protected]) is professor of Public Economics and Administration at VU University Amsterdam. In addition, he is a fellow of Tinbergen Institute, Netspar (Network for Studies on Pensions, Aging and Retirement) and Talma Institute for Work, Care and Welfare. He was Director of the Research Institute for the CDA. He was also affiliated at the Erasmus University Rotterdam and Tilburg University and at the different ministries. His research interests are public administration, local government, industrial organization, and social security.

Notes

Privatization means the contracting out of government services or functions to private firms.

Feiock et al. (Citation2003; Citation2007) have focused on different characteristics of goods as an indicator of the type of transaction costs that may be present. They suggested that, for certain kinds of municipal services, especially collective goods and common property goods, directly provided services are more common, whereas for services resembling toll and private goods, the opposite applies.

As they assume a quadratic relation, this does not hold for high levels of asset specificity. In addition, Carr et al. (Citation2009) also show, for the U.S. context, that nonlinear effects of service characteristics are important.

See also Sundell and Lapuente (Citation2012) for an extensive discussion of these expectations.

It should be noted that the municipal council in the Netherlands is expected to focus its attention on policymaking and evaluation of policy execution, whereas the board of mayor and aldermen is expected to focus its attention on the daily management of the municipality. It should also be noted that Dutch mayors are appointed by the central government, and their executive powers are limited (see also Bel et al. Citation2010).

Our research setting differs considerably from that of Elinder and Jordahl (Citation2013) in terms of: (1) the outcome of the political system (in their (Swedish) setting, political parties are often seen as belonging to either the left block or the right block, whereas such a sharp demarcation cannot be made for the Dutch case); (2) the types of service delivery modes that are available (in their setting, only a choice between in-house and private service delivery modes is available, whereas we distinguish four different modes); and (3) we investigate 12 municipal services, whereas they only investigate one (primary education).

As we have no data for the local number of public employees in the Netherlands, we will not formally test this model.

More specifically, based on survey responses from 16 large Dutch municipalities with regard to the goal and structure of the organization, the role of management, and societal responsibility, Blokker et al. (Citation2014) analyzed to what extent these municipalities have characteristics of PPA, NPM, and NPG. Overall, they categorized 46% of these municipalities as being mainly focused towards NPG, 32% as being mainly focused towards NPM, and 22% as being mainly focused towards PPA.

There is currently a discussion in the Netherlands about whether the executive powers of the mayor should be strengthened by a direct election.

This included all 430 municipalities at the time of research, except the four largest. These municipalities were excluded because they have special legal, administrative, and financial arrangements with the central government which do not apply to other Dutch municipalities (cf. Groot and Budding Citation2004).

A t-test for two independent samples shows no significant difference in size (measured as the natural log of the number of inhabitants) between the respondents and the non-respondents (t(422) = −1.582, p = 0.114). A one-sample Chi-Square test shows no significant difference in regional representation between the respondents and the survey population (χ2(11, 86) = 5.89, p = 0.880).

In total, we have 86 (municipalities) * 12 (services) = 1032–164 (missing values) = 868 municipality-service observations. The missing values are on either the institutional forms variable (due to the fact that some municipalities do not perform all 12 services) and/or the left-right orientation BMA variable (due to the fact that some municipalities only have aldermen coming from local parties, in which case no score for this variable could be calculated). Concerning the latter, there does not seem to be reason for concern for selection bias, given that local parties are quite heterogeneous in terms of left-right orientation.

More specifically, these 12 municipal services are: garbage collection (residential solid waste collection); payroll administration (tasks involved in paying personnel); social security department (paying social benefits and providing help in finding a job); catering (food provision outside the canteen (in meeting rooms, etc.)); cafeteria (food provision inside the canteen); ICT (IT services); maintenance of roads (small infrastructural works, including street repair); green maintenance (maintenance of green areas, including tree trimming and planting); sport facilities (taking care of physical buildings for sport activities); asset valuation (the valuation of real estate, especially for tax assessing); cleaning (cleaning the municipal building(s)); parking management (management of parking facilities, including parking lots and parking areas).

We used the services identified by Wassenaar (Citation2011) as a starting point for our selection of municipal services. However, we did not include the service “security.” Furthermore, we extended his list by adding the services “cafeteria,” “maintenance of roads” (as a replacement for “infrastructural works”), “maintenance of green,” “sports facilities,” and “parking management.”.

Inter-municipal cooperation among Dutch municipalities can be organized in the form of a public WGR (Law on Common Arrangements) entity, where the executive board is directed by the mayors and aldermen of the participating municipalities. However, this cooperation can also take place through contracting out the execution of a service to another (mostly neighboring) municipality (e.g., Gradus et al. Citation2014).

Similar to Brown and Potoski (Citation2005), we assume that a municipality contracts for a service only if (almost) all of the delivery is by a municipality-owned or private firm and not if there is only some contracting with a firm.

This is consistent with archival (administrative) data (see also Gradus et al. Citation2014). Gradus et al. (Citation2014) showed that the number of municipalities with a private firm collecting garbage is decreasing over time, however, mostly due to mergers of small municipalities.

For garbage collection, the number of municipalities with a municipality-owned firm is increasing over time in the Netherlands (Gradus et al. Citation2014). In other countries, such as Portugal, such a phenomenon also exists (e.g., Tavares and Camöes Citation2007).

Levin and Tadelis (Citation2010) used a slightly different approach. In their survey, several obstacles to successful contracting were ranked by city managers. As some of them were correlated, two (normalized) variables were constructed (contracting difficulty and resident sensitivity), which have much in common with those used by Brown and Potoski (Citation2005).

Although this survey was conducted about three years after our initial survey, we believe we may use these data in one analysis, as the characteristics of, and the legal regulations for, the studied services have not changed.

We specifically approached these municipal financial managers as they are supposed to have a broad overview of the municipal services and the motives behind contracting-out decisions. Our respondents all have a degree as Certified Public Controllers or are studying to obtain this degree. Most of them also have had prior academic education.

Half of the municipal services that we focus on (garbage collection, payroll administration, ICT, maintenance of roads, asset valuation, parking management) are also studied by Brown and Potoski (Citation2005; Table ). It should be noted that these services are perceived rather similarly among Dutch and U.S. administrators. In both studies, garbage collection and ICT have a relatively high score for asset specificity and a relatively low score for ease of measurement. Maintenance of roads and parking management also score quite similarly on both characteristics. Similarly, in both the United States and the Netherlands, payroll administration is seen as easy to measure and as requiring little asset-specific investments. Finally, for asset valuation (tax assessing), we notice some differences, but these are probably due to differences in the institutional structure of both countries.

Specifically, we used the scores on the item concerning general party positioning on the left-right dimension of the CHES questionnaire (see Bakker et al. Citation2015 for an assessment of the reliability and validity of this questionnaire). This item is formulated as follows: “Please tick the box that best describes each party’s overall ideology on a scale ranging from 0 (extreme left) to 10 (extreme right).” For the Dutch national political parties, the following scores were provided by the (14) experts: SP (0.16) – GL (0.26) – PvdA (0.39) – D66 (0.50) – CU (0.54) – CDA (0.63) – SGP (0.78) – VVD (0.79) – PVV (0.86). Local parties (LCG, LPG, LOG, and OLG) are not analyzed in the CHES. Accordingly, the theoretical range of our two variables is between 0.16 and 0.86. It should be noted that the populistic Party for Freedom (PVV) of Geert Wilders is almost non-existing on the local level. In the 2010 local election, PVV has only seats and no aldermen in the cities of The Hague and Almere, whereas, on a national level, the PVV got 15% of the votes in parliamentary elections.

Before calculating the natural log of these variables, we have anchored the minimum value in their distribution at exactly 1.0 in order to deal with the issue that the logarithm of a number equal to 0 is undefined.

The Pearson correlations can be obtained from the authors upon request.

The Welch test is reported in addition to the ANOVA test because, for several variables, the homogeneity of variance assumption is not met. Note that both tests provide similar results.

Because the estimated VCE is not of sufficient rank to perform the model test, Stata (as a warning) does not report the model Chi-Square statistic based on the Wald test, which is the most appropriate model test when clustered standard errors are used (e.g., Long and Freese 2014). The Wald tests for the independent variables are all highly significant (all p < 0.01), however, indicating that inclusion of all independent variables significantly reduces the “error variance” of the model(s), and careful inspection of all other MNLM output also suggests that there is nothing wrong with the model (nor with any of our other models). Variance inflation factors (VIFs) indicate that multicollinearity is not a problem in this analysis (average VIF = 2.00; range between 1.12 (for left-right orientation BMA) and 3.47 (for emphasis on input indicators)), nor in the analysis including left-right orientation MC (average VIF = 2.13; range between 1.20 (for asset specificity) and 3.55 (for emphasis on input indicators)). Based on a series of binary logistic regression analyses, we have extensively checked the dataset for potentially influential data points by carefully examining the leverage, discrepancy, and influence of all cases, using the measures and cut-offs suggested by Cohen et al. (Citation2003), Menard (Citation2001), and Pregibon (Citation1981). Overall, this examination gave us little reason to eliminate cases from our analyses. If we would eliminate the most influential data points, however, all relationships that we find in our main analyses are still significant.

Given that, for all service, governance, financial, and socio-economic characteristics the results are quite similar to those reported in Tables and , we do not present these results. These results are available upon request.

Similarly, on average, a standard deviation increase in the left-right orientation of a municipal council increases the probability of performing the service within a private firm by 0.019, while decreasing the probability of performing the service within an inter-municipal cooperation by 0.024. These marginal effects are available upon request.

This finding is consistent with the Patronage model, which states that politicians may prefer in-house delivery above contracting out, as the former gives more opportunities to employ local personnel and may also increase support from public employee unions. These elements are even more important in case of worse labor market conditions (see also Dijkgraaf et al. Citation2003).

Similar to the analyses based on the (relative) emphasis that is put on the different types of performance indicators, variance inflation factors (VIFs) indicate that multicollinearity is not a problem in this analysis (average VIF = 2.43; range between 1.13 (for left-right orientation BMA) and 4.87 (for number of objectives)), nor in the analysis including left-right orientation MC (average VIF = 2.53; range between 1.20 (for asset specificity) and 4.85 (for number of objectives)). We have also estimated these models focusing only on the (absolute) number of used performance indicators (i.e., excluding the number of formulated objectives). These alternative analyses show similar results for all remaining variables.

REFERENCES

- Bakker, R., C. de Vries, E. Edwards, L. Hooghe, S. Jolly, G. Marks, J. Polk, J. Rovny, M. Steenbergen, and M. A. Vachudova. 2015. “Measuring Party Positions in Europe: The Chapel Hill Expert Survey Trend File, 1999–2010.” Party Politics 21(1): 143–152.

- Bel, G. and X. Fageda. 2007. “Why Do Local Governments Privatise Public Services? A Survey of Empirical Studies.” Local Government Studies 33(4): 517–534.

- Bel, G. and X. Fageda. 2009. “Factors Explaining Local Privatization: A Meta-Regression Analysis.” Public Choice 139(1–2): 105–119.

- Bel, G., T. L. Brown, and M. E. Warner. 2014. “Editorial Overview: Symposium on Mixed and Hybrid Models of Public Service Delivery.” International Public Management Journal 17(3): 297–307.

- Bel, G., X. Fageda, and M. E. Warner. 2010. “Is Private Production of Public Services Cheaper than Public Production? A Meta-Regression Analysis of Solid Waste and Water Services.” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 29(3): 553–577.

- Blokker, K., S. Hamersma, K. Kalez, and M. Kruijff. 2014. “Public Controller: ‘Netwerker’ van de Toekomst?” Tijdschrift voor Public Governance, Audit & Control 12(6): 11–16.

- Boogers, M. and G. Voerman. 2010. “Independent Local Political Parties in the Netherlands.” Local Government Studies 36(1): 75–90.

- Bouckaert, G. and J. Halligan. 2008. Managing Performance: International Comparisons. London, UK: Routledge.

- Boyne, G. A. 1998. “Bureaucratic Theory Meets Reality: Public Choice and Service Contracting in U.S. Local Government.” Public Administration Review 58(6): 474–484.

- Breeman, G., P. Scholten, and A. Timmermans. 2015. “Analysing Local Policy Agendas: How Dutch Executive Coalitions Allocate Attention.” Local Government Studies 41(1): 20–43.

- Brown, T. L. and M. Potoski. 2003. “Transaction Costs and Institutional Explanations for Government Service Production Decisions.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 13(4): 441–468.

- Brown, T. L. and M. Potoksi. 2005. “Transaction Costs and Contracting: The Practitioner Perspective.” Public Performance and Management Review 28(3): 326–351.

- Brown, T. L., M. Potoski, and D. Slyke. 2006. “Managing Public Service Contracts: Aligning Values, Institutions, and Markets.” Public Administration Review 66(3): 323–331.

- Brown, T. L., M. Potoski, and D. Slyke. 2016. “Managing Complex Contracts: A Theoretical Approach.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 26(2): 294–308.

- Carr, J. B., K. LeRoux, and M. Shrestha. 2009. “Institutional Ties, Transaction Costs and External Service Production.” Urban Affairs Review 44(3): 403–427.

- Cohen, J., P. Cohen, S. G. West, and L. S. Aiken. 2003. Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 3rd ed. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Cuadrado Ballesteros, B. C., I. M. García Sánchez, and J. M. Prado Lorenzo. 2013. “The Impact of Political Factors on Local Government Decentralisation.” International Public Management Journal 16(1): 53–84.

- Dijkgraaf, E. and R. H. J. M. Gradus. 2007. “Collusion in the Dutch Waste Collection Market.” Local Government Studies 33(4): 573–588.

- Dijkgraaf, E. and R. H. J. M. Gradus. 2013. “Cost Advantage Cooperations Larger than Private Waste Collectors.” Applied Economic Letters 20(7): 702–705.

- Dijkgraaf, E., R. H. J. M. Gradus, and B. Melenberg. 2003. “Contracting Out Refuse Collection.” Empirical Economics 28(3): 553–570.

- Elinder, M. and H. Jordahl. 2013. “Political Preferences and Public Sector Outsourcing.” European Journal of Political Economy 30: 43–57.

- Feiock, R. C., J. C. Clinger, M. Shrestha, and C. Dasse. 2007. “Contracting and Sector Choice across Municipal Services.” State and Local Government Review 39(2): 72–83.

- Feiock, R. J. C., Clingermayer, and C. Dasse. 2003. “Sector Choices for Public Service Delivery: The Transaction Cost Implications of Executive Turnover.” Public Management Review 5(2): 163–176.

- Fleurke, F. and R. Willemse. 2006. “Measuring Local Autonomy: A Decision-Making Approach.” Local Government Studies 32(1): 71–87.

- Garrone, P., L. Grilli, and X. Rousseau. 2013. “Management Discretion and Political Interference in Municipal Enterprises: Evidence from Italian Utilities.” Local Government Studies 39(4): 514–540.

- Girth, A. M. 2014. “What Drives the Partnership Decision? Examining Structural Factors Influencing Public-Private Partnerships for Municipal Wireless Broadband.” International Public Management Journal 17(3): 344–364.

- Gradus, R. H. J. M. and G. T. Budding. 2016. “Re-municipalisation is Becoming More and More Important in the Netherlands: Some Explanations.” Paper presented at EPCS Meeting, Freiburg, Germany, April 2.

- Gradus, R. H. J. M., E. Dijkgraaf, and M. Schoute. 2016. “Is There Still Collusion in the Dutch Waste Market?” Local Government Studies 42(5): 689–697.

- Gradus, R. H. J. M., E. Dijkgraaf, and M. Wassenaar. 2014. “Understanding Mixed Forms of Refuse Collection, Privatisation and its Reverse in the Netherlands.” International Public Management Journal 17(3): 328–343.

- Groot, T. L. C. M. and G. T. Budding. 2004. “The Influence of New Public Management Practices on Product Costing and Service Pricing Decisions in Dutch Municipalities.” Financial Accountability & Management 20(4): 421–443.

- Groot, T. L. C. M. and G. T. Budding. 2008. “New Public Management’s Current Issues and Future Prospects.” Financial Accountability & Management 24(1): 1–13.

- Hatry, H. P. 2006. Performance Measurement: Getting Results. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute Press.

- Hefetz, A., M. E. Warner, and E. Vigoda-Gadot. 2012. “Privatization and Intermunicipal Contracting: The U.S. Local Government Experience 1992–2007.” Environmental and Planning C: Government and Policy 30(4): 675–692.

- Helden, G. J. van and E. P. Jansen. 2003. “New Public Management in Dutch Local Government.” Local Government Studies 29(2): 68–88.

- Hendriks, F. and P. Tops. 2003. “Local Public Management Reforms in the Netherlands: Fads, Fashions and Winds of Change.” Public Administration 81(2): 301–323.

- Hood, C. 1995. “The ‘New Public Management’ in the 1980s: Variations on a Theme.” Accounting, Organizations & Society 20(2/3): 93–109.

- IFAC. 2001. Governance in the Public Sector: A Governing Body Perspective. New York, NY: International Federation of Accountants.

- Levin, J. and S. Tadelis. 2010. “Contracting for Government Services: Theory and Evidence for U.S. Cities.” Journal of Industrial Economics 58(3): 507–541.

- Long, J. S. and J. Freese. 2014. Regression Models for Categorical Dependent Variables Using Stata, 3rd ed. College Station, TX: Stata Press.

- López-de-Silanes, A., F. A. Shleifer, and R. W. Vishny. 1997. “Privatization in the United States.” Rand Journal of Economics 28(3): 447–471.

- Menard, S. 2001. Applied Logistic Regression Analysis, 2nd ed. Sage University Papers Series on Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences, 07–106. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Pérez-López, G., D. Prior, and J. L. Zafra-Gómez. 2015. “Rethinking New Public Management Delivery Forms and Efficiency: Long-Term Effects in Spanish Local Government.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 25(4): 1157–1183.

- Petersen, O. H., K. Houlberg, and L. R. Christensen. 2015. “Contracting Out Local Services: A Tale of Technical and Social Services.” Public Administration Review 75(4): 560–570.

- Plata-Díaz, A. M., J. L. Zafra-Gómez, G. Pérez-López, and A. M. López-Hernández. 2014. “Alternative Management Structures for Municipal Waste Collection Services: The Influence of Economic and Political Factors.” Waste Management 34: 1967–1976.

- Pollitt, C. and G. Bouckaert. 2004. Public Management Reform: A Comparative Analysis, 2nd ed. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Pregibon, D. 1981. “Logistic Regression Diagnostics.” Annals of Statistics 9(4): 705–724.

- Rodrigues, M., A. F. Tavares, and J. F. Araújo. 2012. “Municipal Service Delivery: The Role of Transaction Cost in the Choice between Alternative Governance Mechanisms.” Local Government Studies 38(5): 615–638.

- Sundell, A. and V. Lapuente. 2012. “Adam Smith or Machiavelli? Political Incentives for Contracting Out Local Public Services.” Public Choice 153(3): 469–485.

- Tavares, A. F. and P. J. Camöes. 2007. “Local Service Delivery Choices in Portugal: A Political Transaction Costs Framework.” Local Government Studies 33(4): 535–553.

- Ter Bogt, H. 1999. “Financial and Economic Management in Autonomized Dutch Public Organizations.” Financial Accountability & Management 15(3&4): 329–351.

- Ter Bogt, H. 2008. “Management Accounting Change and New Public Management in Local Government: A Reassessment of Ambitions and Results—An Institutionalist Approach to Accounting Change in the Dutch Public Sector.” Financial Accountability & Management 24(3): 209–241.