Abstract

Public services are often corporatized with the expectation that corporatization brings more business-like service delivery. However, the actual usage of business techniques is rarely studied as a factor that influences corporatization’s success. We study the mediating effect of business techniques on the autonomy-performance link among Dutch municipally owned corporations. We find that while the direct effect of autonomy on performance is statistically non-significant or negative, business techniques are both directly helpful for performance in MOCs and (partially) mediate the relationship between autonomy and performance.

Introduction

(Semi-)autonomous delivery of public services is a complex topic in the literature on public sector performance. While corporatization – the creation of companies for public service delivery – is a trend, especially in local government (Aars and Ringkjøb Citation2011; Bergh et al. Citation2018; Ferry et al. Citation2018; Grossi and Reichard Citation2008; Papenfuß et al. Citation2018; Voorn, Van Thiel, and Van Genugten Citation2018), we still have not fully assessed its effects (Cambini et al. Citation2011; Voorn, Van Genugten, and Van Thiel Citation2017). On the one hand, corporatization can bring out expert managers who can deliver services in a more efficacious manner than bureaucracies constrained by law and dominated by political interests (Bourdeaux Citation2007). On the other hand, political principals have difficulty monitoring and regulating corporatized services to ensure achievement of public objectives (Egeberg and Trondal Citation2009; Tavares and Camões Citation2007; Voorn, Van Genugten, and Van Thiel Citation2017). There remains no consensus about whether corporatization is in the end harmful or beneficial for public service delivery (Boardman and Vining Citation1989; Overman and Van Thiel Citation2016; Verhoest Citation2005; Verhoest et al. Citation2010).

In the face of this uncertainty, reasons for corporatizing are often pragmatic, or based in expectation rather than knowledge (Citroni, Lippi, and Profeti Citation2015; Grossi and Reichard Citation2008; Tavares Citation2017; Tavares and Camões Citation2007; Voorn, Van Thiel, and Van Genugten Citation2018). One such expectation is that corporatization can bring more business-like public service delivery, which might make public service delivery more effective. Yet research into whether corporatization is beneficial has rarely studied the usage of business techniques as a mediator of the autonomy-performance link. Consequently, we still do not know how, when, and why corporatization might be desirable, and what role use of business techniques play in this process.

Our aim in this article is to shed more light on the role of the use of business techniques in corporatization. Specifically, we study the mediating effect of business techniques on the autonomy-performance link among municipally owned corporations (MOCs) – public service organizations operating at arm’s length from the municipal bureaucracy. We address the Netherlands’ entire population of 799 MOCs with a questionnaire exploring their autonomy, self-perceived performance, and use of business techniques, along with background variables. We use measures previously validated in research among agencies by the Comparative Public Organization Data Base for Research and Analysis (COBRA) (Christensen and Laegreid Citation2006; Van Thiel and Yesilkagit Citation2011; Verhoest, Peters, et al. Citation2004; Verhoest et al. Citation2012; Verhoest, Van Thiel, et al. Citation2004; Verhoest, Verschuere, et al. 2004; Wettenhall Citation2005; Yesilkagit and Van Thiel Citation2008, Citation2012).

We find a partial mediation effect of the use of internal business techniques on the autonomy-performance link, indicating that (i) more frequent use of internal business techniques positively affects performance, while (ii) yet other facets of managerial autonomy affect performance beyond business techniques alone. We also find that not all managerial autonomy is created equal: autonomy in HRM helps bring about business-like service delivery, while financial autonomy prevents it. One explanation of this could be that corporations with extensive HRM autonomy are more likely to attract personnel from the private sector, creating a more business-like environment in the corporation that aids performance. In line with previous research (cf. Boardman and Vining Citation1989; Overman and Van Thiel Citation2016; Verhoest Citation2005; Verhoest et al. Citation2010; Voorn, Van Genugten, and Van Thiel Citation2020), we find no significant direct effect of managerial autonomy on performance in municipally owned corporations.

We organize the remainder as follows. Section 2 describes the background of this study. Section 3 describes the theory on managerial autonomy and business techniques, culminating in 5 hypotheses. Section 4 explains the methods utilized to test our hypotheses. Section 5 reports our results. Section 6 discusses implications and explores potential avenues for future research.

Background: municipally owned corporations

Municipally owned corporations (MOCs) are organizations “with independent corporate status, managed by an executive board appointed primarily by local government officials with majority public ownership” (Voorn, Van Genugten, and Van Thiel Citation2017). Since the start of the century, there has been an observable rise in the numbers and budgets of MOCs in many countries (Bergh et al. Citation2018; Ferry et al. Citation2018; Gradus and Budding Citation2018; Grossi and Reichard Citation2008; Papenfuß et al. Citation2018; Voorn, Van Thiel, and Van Genugten Citation2018). Understanding their performance is thus an increasing priority (Ferry et al. Citation2018; Voorn, Van Genugten, and Van Thiel Citation2017).

MOCs can be seen as a” middle road between privatization and bureaucratic service delivery. They allow public ownership, while introducing a measure of competition (Leavitt and Morris Citation2004; Voorn, Van Genugten, and Van Thiel Citation2019). Through corporatization, managers can be solicited from outside the public bureaucracy, and so, competition is introduced at executive board level, rather than at firm level (Van Genugten, Voorn, and Van Thiel Citation2020; Voorn, Van Genugten, and Van Thiel Citation2019). This competition may be absent within the public bureaucracy, and privatization and contracting-out may sometimes fail to bring the desired number of bidders; MOCs can be a pragmatic alternative balancing public ownership and competitive pressures for efficacy (Leavitt and Morris Citation2004; Voorn, Van Genugten, and Van Thiel Citation2019).

Whether MOCs constitute a more efficacious form of local public service delivery than delivery through the public bureaucracy is yet unclear (Bourdeaux Citation2007; Cambini et al. Citation2011; Da Cruz and Marques Citation2011; Pérez-López, Prior, and Zafra-Gómez Citation2015; Swarts and Warner Citation2014; Voorn, Van Genugten, and Van Thiel Citation2017). In the absence of knowledge about effects, reasons for corporatizing have primarily been pragmatic or based in expectations (Bourdeaux Citation2005; Citroni, Lippi, and Profeti Citation2013, Citation2015; Grossi and Reichard Citation2008; Rodrigues, Tavares, and Araújo Citation2012; Tavares Citation2017; Tavares and Camões Citation2007). One such expectation is that corporatization can bring more business-like public service delivery, which can make it more efficient (Overman Citation2016). Corporatization can “replace politics by professionalism” (Bourdeaux Citation2007): MOCs can be managerially involved in many business activities, including marketing, retail, research and development, production, purchasing, and diversification practices (Krause and Van Thiel Citation2019; Lioukas, Bourantas, and Papadakis Citation1993). Yet the usage of business techniques is rarely studied as a reason why corporatization is more or less efficacious. Our objective in this article is to investigate this link.

Theory

Managerial autonomy and performance

Much has been written on the relationship between managerial autonomy and performance. On the one hand, according to public choice theory, managerial autonomy granted to experts hired for management in arm’s length organizations can increase performance, as it distances service delivery from the influence of politicians, who may have political incentives that discourage performance-maximizing decision-making (Bourdeaux Citation2007). On the other hand, following principal-agent theory, this increased distance between political principals and management creates information asymmetries that may create oversight difficulties. This, in turn, can result in increased (performance-reducing) principal-agent problems, such as rent-seeking (Egeberg and Trondal Citation2009; Tavares and Camões Citation2007; Voorn, Van Genugten, and Van Thiel Citation2017). The question whether we should expect managerial autonomy to be performance-enhancing is in the end an empirical question, and not a theoretical one. Unfortunately, research into the effects of corporatization is limited (Cambini et al. Citation2011; Torsteinsen Citation2019) and ambiguous (Pollitt and Dan Citation2013).

For MOCs specifically, the effects of managerial autonomy on performance seem to be either insignificant or small but positive. Torsteinsen et al. (Citation2018) find mixed effects of autonomy on performance of municipally owned corporations in five countries. Voorn, Van Genugten, and Van Thiel (Citation2020) find that the relationship between autonomy and performance in Dutch municipally owned corporations is positive but statistically insignificant. Cambini et al. (Citation2011) and Swarts and Warner (Citation2014) find that corporatization leads to cost savings. Pérez-López, Prior, and Zafra-Gómez (Citation2015) find that whether corporatization is successful depends on the sector where it takes place. Bourdeaux (Citation2007) finds that many corporatization projects fail, and Da Cruz and Marques (Citation2011) find that corporatization does not bring desired effects when autonomy is insufficiently granted. Summarizing, Voorn, Van Genugten, and Van Thiel (Citation2017) conclude in a systematic literature review that MOCs have the potential to increase efficiency compared to municipal bureaucracy, but that relatively many corporatization projects perform poorly.

Considering corporatization beyond the local level, evidence is almost exclusively limited to the literature on “agencification”, which occurs under public law (Egeberg and Trondal Citation2009; Overman and Van Thiel Citation2016; Van Thiel et al. Citation2012; Vining, Laurin, and Weimer Citation2015). Verhoest (Citation2005) finds that autonomy is performance-enhancing in Flemish public agencies in specific conditions. Overman and Van Thiel (Citation2016) find output losses as a result of agencification in a systematic comparison of 20 countries, and Overman (Citation2017) finds no evidence of satisfaction gains from agencification in a survey of 15 countries. Nelson and Nikolakis (Citation2012) find a positive link between autonomy and performance in state forest agencies in Australia. Vining, Laurin, and Weimer (Citation2015) find initial gains from autonomy among agencies in Quebec, but suggest that these may plateau over time. Wynen et al. (Citation2014), considering agencies in five countries, uncover a positive effect of autonomy on innovation, but argue that result control can stifle this innovation. Overall, the evidence of the effects of autonomy in public service delivery is mixed (Pollitt and Dan Citation2013), limited (Cambini et al. Citation2011), and not generalizable over multiple countries (Torsteinsen Citation2019).

One of the reasons why it is difficult to link managerial autonomy to performance is that managerial autonomy is difficult to study. The construct ‘managerial autonomy’ encapsulates many different types of discretion that corporations may have. The literature identifies three types of managerial autonomy in the public sector and among MOCs specifically (COBRA Citation2010; Verhoest, Peters, et al. Citation2004; Verhoest, Van Thiel, et al. Citation2004; Voorn, Van Genugten, and Van Thiel Citation2017, Citation2020). First, strategic autonomy determines who is generally in control of outlining the longer-term strategy and yearly targets for the corporations. Second, financial autonomy determines to what extent the corporations have control over their budget and expenses in the short term, and over investments in the long term. Third, HRM autonomy determines the discretion that corporations have over HRM matters. This is often a defining feature of the autonomy of corporations, given the relative strictness of public sector HRM rules in many countries. Yet while the literature distinguishes between these types of autonomy, it does not bring different expectations regarding how these factors affect performance. All types of managerial autonomy make it more difficult for the political principal to steer or monitor the corporation. Simultaneously, all three types of managerial autonomy allow greater freedom for MOCs to manage service delivery in a way that is potentially more efficient than the public bureaucracy would manage it.

Business techniques

Although it is often argued that managerial autonomy allows MOCs to perform better because they are able to behave in a business-like manner, this mediating mechanism is rarely researched empirically. Moreover, it is often left implicit what behaving in a business-like manner means. This inhibits our understanding of how autonomy affects performance, as it is likely (i) that not all facets of managerial autonomy help bring about business-like behavior and (ii) that not all types of business-like behavior are effective in increasing performance.

One way to define business-like behavior of MOCs is to examine the mechanisms by which they manage the internal organization – hereafter referred to as internal business techniques – and the service delivery toward their clients – hereafter referred to as external business techniques. In other words, while managerial autonomy measures what organizations can do, business techniques are about what they actually do in practice. Examples for internal business techniques include performance management systems, product quality standards, or multi-year planning. Examples for external business techniques include offering additional services for pay, developing innovative products and services, and refocusing the organization toward new target groups.

While most research on national-level agencies examines the influence of managerial autonomy on the adoption of internal techniques such as performance management (Verhoest et al. Citation2010; Verhoest and Wynen Citation2018; Wynen, Verhoest, and Rübecksen Citation2014), some empirical research exists on external techniques, such as developing innovative products or services, as well (Wynen et al. Citation2014). The expected positive effect of managerial autonomy on the usage of these techniques is often based on the idea that managerial flexibility allows and motivates public managers to adopt techniques that are in line with the reasons for corporatization, i.e. to become more effective. However, according to Verhoest et al. (Citation2010), the relation between autonomy and internal business techniques in MOCs is not merely explained by economic rationality. Institutional mechanisms play a role as well, as business techniques provide a way to bridge information asymmetries, which makes political principals less likely to re-internalize the service. In this respect, Blom, Kruyen, Van Thiel et al. (Citation2020) found that the adoption of business-like personnel systems by national-level agencies was strongly influenced by both a need to achieve legitimacy with their parent ministry and a need to improve service delivery. Thus, managerial autonomy encourages business technique usage both because of increased managerial flexibility and because information asymmetries make managers more wanting to legitimize their autonomy. Building on these findings, it could be expected that, regardless of the type, managerial autonomy in general will lead to an increased use of business techniques. Therefore, the following hypotheses are formulated:

H1: Autonomy in Human Resource Management has a significant positive effect on the use of both internal and external business techniques.

H2: Autonomy in financial affairs has a significant positive effect on the use of both internal and external business techniques.

H3: An organization's own control over target setting has a significant positive effect on the use of both internal and external business techniques.

One main reason why internal and external business techniques have become popular in public organizations is their hypothesized effect on performance (Pollitt and Bouckaert Citation2011). Business administration scholars have consistently found that adoption of these techniques leads to higher performance outcomes, such as productivity, quality, and efficiency (Combs et al. Citation2006; Jiang et al. Citation2012). Although scholars have questioned if the same effects are witnessed in public organizations (Brown Citation2004; Burke, Noble, and Cooper Citation2013), a recent meta-analysis showed that business techniques can be equally effective in the public sector (Blom, Kruyen, Van der Heijden, et al. Citation2018). Thus, based on the idea that managerial autonomy leads to an increased use of business techniques and that these techniques are related to higher performance, the following hypotheses are formulated:

H4: The relationship between all forms of managerial autonomy and performance are partially mediated by the use of internal business techniques.

H5: The relationship between all forms of managerial autonomy and performance are partially mediated by the use of external business techniques.

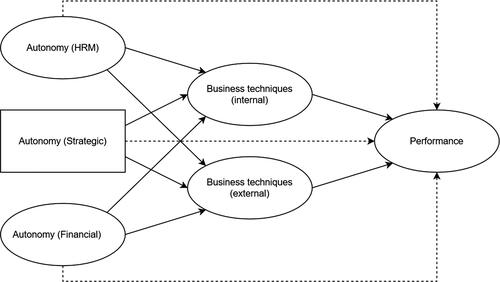

These hypotheses lead to the conceptual model as presented in .

Methods

Data collection

To test the hypotheses, we employed a survey carried out in February 2018 among the directors of all Dutch MOCs. From November 2017 to January 2018, the first author systematically went through the budgets of all 390 Dutch municipalities, which are obliged by law to list MOCs, and included all found MOCs in a database, omitting “empty” holding companies and organizations with no listed address. This yielded a database of 809 MOCs. Letters were sent requesting survey participation to this entire population. 10 letters were returned indicating inability to deliver. These MOCs were removed from the database, leaving a population of 799 MOCs.

243 of the 799 delivered surveys were returned (response rate 30.4%). 61 surveys were returned incomplete (all under 30% completion); these were excluded. 5 more respondents suggested they had no budget or no employees, and upon further reflection were not independent organizations and were excluded. After listwise deletion of respondents with missing values on one or more of the studied variables, 169 MOCs remained for analysis. We attempted to collect some information about the whole population; unfortunately, many descriptive data were inaccessible or outdated. However, we could compare our population and sample in sector and corporate status, and on those counts, we find that the sample is fairly representative of the population (see Appendix A).

Survey method

We based the items for our measures (constructs) partially on earlier surveys by the EU network ‘Comparative Public Organization Data Base for Research and Analysis’ (COBRA), sent to agencies and quasi-autonomous government organizations in various countries (COBRA Citation2010; Verhoest et al. Citation2012; Verhoest, Van Thiel, et al. Citation2004). For the purpose of this study, the original questions from the COBRA-questionnaire were translated from English into Dutch. It was possible to use existing Dutch translations of the COBRA-questionnaire, validated by Van Thiel and Yesilkagit (Citation2011), Yesilkagit and Van Thiel (Citation2008), and Yesilkagit and Van Thiel (Citation2012).

To ensure that our measures were applicable also at the local level, we adjusted our survey specifically to target municipally owned corporations in terminology, and conducted a pilot study of our survey among local government experts and former MOC directors. We also used this pilot study to test the terminology used in the survey. Multiple changes were made based on our findings in the pilot study, in particularly in the control variables (discussed in the next section); our measures for managerial autonomy, business techniques, and organizational performance were deemed also applicable at the local level by our pilot study respondents. We revisit the limitation of the COBRA survey in the conclusion.

Measures

The construct managerial autonomy included the measures financial autonomy, HRM autonomy, and strategic autonomy, validated in the original COBRA-survey (COBRA Citation2010). For financial and HRM autonomy, respondents were given a list of types of autonomy they could have (8 items for financial autonomy, 8 items for HRM autonomy), which they could answer as “yes,” “with consent of shareholders,” or “no.” For measuring strategic autonomy, respondents were asked to what extent they have a leading role in creating performance targets. Possible answers ranged from 1 (The shareholders set targets) to 5 (The MOC sets targets itself).

The construct business techniques included the measures internal business techniques and external business techniques following the original COBRA-survey (COBRA Citation2010). Respondents answered questions about the extent to which they applied several business techniques (5 internal business techniques and 3 external techniques) on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 ((almost) never) to 4 ((almost) always).

The constructs autonomy and business techniques thus regard the presence (or absence) of specific elements of firm behavior. Since these are objectively verifiable indicators, which do not evoke the subjective opinion of the respondent, answers are not expected to be subject to (positive or negative) affectivity and social desirability bias. The correlation between these constructs and the performance construct is therefore not expected to be influenced by common method bias (see also Jakobsen and Jensen, Citation2015, p.14).

The construct organizational performance was measured with 9 items from the validated performance scale of the COBRA-survey (COBRA Citation2010). The respondents answered questions about the extent to which they perceived that their organization performed well in several areas on a 10-point scale. The questions cover various aspects of organizational performance: goal performance, process performance, personnel performance, and system performance. We emphasize that these items are self-evaluated. However, respondents were surveyed online, and were given clear notice that their responses were anonymized in compliance with EU-GDPR regulation, reducing social desirability bias. Moreover, performance questions tightly focused on specific indicators of performance, which mitigates the risk of upward reporting (Brannick et al. Citation2010; Meier & O'Toole, Citation2013a) and limits possibilities for common source bias (Jakobsen & Jensen, Citation2015) by reducing their subjectivity. We therefore do not expect substantial upward reporting for our dependent variable. To the extent that upward reporting exists for our dependent variables, we expect it to be uncorrelated with the independent variables, because the latter are not expected to be subject to affectivity or social desirability bias either.

Finally, several control variables were included. The number of municipal owners was included as a continuous variable. Whether the MOC has public and/or private shareholders was measured using two dummy variables (“yes” or “no” for public shareholders; “yes” or “no” for private shareholders). Furthermore, the number of employees, the size of the budget (in thousands) and the age of the organization were included as continuous variables. To measure the impact of sector, we measured labor intensity, the extent to which organizations depend on labor measured through the division of the square root of the number of employees over the square root of the size of the budget, and industry, a dummy variable as to whether performance indicators primarily involved the MOC’s financial results (rather than service quality). All items of the used constructs can be found in Appendix B.

Strategy of analysis

Our five hypotheses were tested using structural equation modeling performed in Mplus version 7.4 (Muthén, Muthén, and Asparouhov Citation2016). A two-step approach was adopted where, first, we examined the measurement model, followed by analysis of the structural model (cf. Anderson and Gerbing Citation1988). Since the measurement model included some categorical variables with skewed answer distributions (floor and ceiling effects), we applied the Weighted Least Squares Means and Variance-adjusted (WLSMV) estimation method. The WLSMV estimation method does not assume normally distributed variables and provides the best option for modeling categorical data (Brown Citation2006). After developing the measurement model, factors for the structural model were automatically corrected for skewedness and made continuous.

To test the measurement model, several fit measures were analyzed. In line with common practice, the comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), and root mean square of approximation (RMSEA) were used to assess whether the model fits the data. The CFI and TLI measures indicate fit with a threshold above .90 and excellent fit above .95. The RMSEA value indicates good fit below .08 and excellent fit below .05 (Byrne Citation2012; Hu and Bentler Citation1999; Kline Citation2010). In addition, construct reliability (C.R.) and Average Variance Extracted (AVE) were calculated to test the reliability and validity of our variables respectively.

To analyze relationships between the constructs, we developed a mediated SEM. To test mediating effects, we applied the “Delta method” included in Mplus. This method utilizes the Sobel method (Sobel Citation1982) which is a commonly applied conservative method to test latent models with two or more mediators (MacKinnon Citation2008; Taylor, MacKinnon, and Tein Citation2008). Since we incorporate two mediators, this method appears the most viable to test mediation.

Results

In this section, we present the results of the study. First, we construct a measurement model of the study’s central variables, in order to assess its measurement quality and convergent and discriminant validity. Next, we report correlations. Finally, we examine our hypotheses through the structural equation model.

Measurement model

The measurement model consisted of five latent variables – financial autonomy, HRM autonomy, internal business techniques, external business techniques, performance – and one non-latent, single-item variable – strategic autonomy. As these measures from the COBRA-questionnaire are applied to MOCs for the first time, we assessed the data structure of the measurement through a series of model comparisons (e.g. Luu Citation2018). As shown in , we combined several antecedents of performance. The results showed a good fit between the hypothesized five-factor model and the data (CFI = 0.95, TFI = 0.95, RMSEA = 0.05).

Table 1. Comparison of measurement models.

All items loaded significantly onto their appropriate factor. While one internal technique (steering of the organizational sub-units and lower management levels in financial and human resource management) had a loading of only 0.41, lowering the AVE to 0.3, C.R. was good and no double loadings were detected. To stay in line with the already validated scale, we opted to retain the item. For external techniques, too, there was one low loading of 0.47 (extension of service delivery for pay), lowering the AVE to 0.4, but C.R. was good. Due to the mixed reliability statistics, we chose to retain the low scoring techniques in the factors. For all other constructs, C.R.s exceeded 0.6 and AVEs exceeded 0.5, satisfying the rules of thumb (Fornell and Larcker Citation1981). presents the means, standard deviations (S.D.), and correlations of the studied variables.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics and correlations.

The AVE of 3 of the 5 constructs exceeds the squared correlations between the other constructs, so discriminant validity is sufficiently warranted. As mentioned, the AVE of internal and external techniques are low; lower than the squared correlation with each other. Although the correlation between the two techniques is 0.75, the Variance Inflation Factor between the constructs is within the acceptable range (VIF = 1.22), indicating the absence of multicollinearity (Bowerman and O'Connell Citation1990). Furthermore, Cronbach alphas of both constructs are acceptable (respectively internal α = 0.61, and external α = 0.61), and, as shown in , the fit of the five-factor model is better than the model in which the two techniques are combined. While this difference is marginal, it demonstrates discriminant validity. Interestingly, the techniques have higher reliabilities among semi-autonomous agencies (COBRA Citation2010). These findings will be discussed in the final section.

Structural equation model

We created a structural model to test our hypotheses. The structural path model is shown in above and without control variables, as only the control variable related to the private shareholders has a significant relationship with performance (β = 0.185, p < .05).

Table 3. Structural path analyses.

Fit measures of the model for indicated good fit (CFI = .95, TLI = .94, RMSEA = 0.04). Based on the findings, we can accept hypothesis 1: HRM autonomy has a significant positive effect on the use of both internal business techniques (β = 0.75, p < .001) and external business techniques (β = 1.04, p < .001) in MOCs. In contrast, we reject hypothesis 2: financial autonomy has a significant negative effect on the use of both internal and external business techniques (respectively β = −0.32, p < .001 and β = −0.73, p < .001) by MOCs. We also (partially) reject hypothesis 3. While strategic autonomy has a positive significant effect on MOCs’ usage of internal business techniques (β = 0.27, p < .001), it has a (non-significant) negative effect on MOCs’ usage of external business techniques (β = −0.09, p = ns).

Relating these forms of managerial autonomy and business techniques to MOCs’ performance, we find that the usage of internal business techniques is a partial mediator between all three forms of managerial autonomy and MOCs’ performance (hypothesis 4), as demonstrated in . Noteworthy is that while internal business techniques mediate HRM autonomy (β = 0.58, p < .001) and strategic autonomy (β = 0.21, p < .01) on MOCs’ performance, the total effect on performance remains insignificant.

In contrast, hypothesis 5 should be rejected. shows that the external business techniques are non-significant partial mediators between the three forms of managerial autonomy and performance. Thus, while internal and external business techniques have positive significant direct effects on performance, their mediating effects between the HRM, financial, and strategic autonomy of MOCs on the one hand and the performance of MOCs on the other hand are not strong enough to positively link managerial autonomy to performance.

Discussion

Our finding that managerial autonomy has an ambiguous effect on performance in municipally owned corporations (MOCs) is in line with the conflicting evidence found in the literature on local corporatization (cf. Bourdeaux Citation2007; Cambini et al. Citation2011; Da Cruz and Marques Citation2011; Pérez-López, Prior, and Zafra-Gómez Citation2015; Swarts and Warner Citation2014; Torsteinsen et al. Citation2018; Voorn, Van Genugten, and Van Thiel Citation2017, Citation2020) and on agencification (Egeberg and Trondal Citation2009; Nelson and Nikolakis Citation2012; Overman Citation2017; Overman and Van Thiel Citation2016; Van Thiel et al. Citation2012; Verhoest Citation2005; Vining, Laurin, and Weimer Citation2015; Wynen et al. Citation2014). Also in MOCs, there might be a tradeoff between the potential efficacy gain provided by avoiding the politicization of service delivery and the performance loss that may result from increased information asymmetries in the steering relationship between the political principal and the corporation.

Our main contribution in this article is to show that, while the direct effect of all types of managerial autonomy on performance is non-significant or even negative, business techniques are both directly helpful for performance in MOCs and (partially) mediate the relationship between managerial autonomy and performance. To the best of our knowledge, this mediating relationship of business techniques on the autonomy-performance link in MOCs has not previously been demonstrated in the literature. Future studies investigating the effects of corporatization should take this mediating effect of business techniques into consideration to fully understand corporatization’s effects.

For practitioners, the main message is that corporatizing public service delivery is no panacea to improve the performance of public service delivery, and might, when no business-like service delivery is implemented, even have a direct negative effect on the performance of public service delivery. In fact, it is possible that corporatization is not even required, and that the introduction of business techniques alone may be sufficient to improve performance. We suggest that corporatization should not be a goal, but rather a means to introduce business techniques into public service delivery. HRM autonomy seems to encourage the use of these business techniques. A reason for this could be that corporations with larger HRM autonomy are more likely to attract personnel from the private sector.

It is important here to emphasize that we have considered the effects of these business techniques on the autonomy-performance link, but introducing such business techniques may have other consequences for MOCs. For instance, business techniques may or may not negatively affect accountability, may or may not erode the “democratic nature” of public service provision, and may or may not make political steering and governance more difficult. Further research should look into the effects of business techniques on the “stewardship” and governance of MOCs.

A few additional limitations of this study should be addressed. First, many business techniques are possible, and our selection, following COBRA research, is plausibly incomplete. This is not a strong limitation, as it is plausible that the mediating effect of business techniques on the autonomy-performance link becomes stronger if more business techniques are added, but we had no strong methodological reason for doing so. The same is true for performance measures: adding other performance measures may affect outcomes, but we decided to retain the performance measures from the COBRA survey. Next, factor loadings of the measures of the COBRA-survey remained sufficient at the lower government level among MOCs, but did lose some strength. The COBRA-survey thus seems applicable at the local level among MOCs, which we tried to ensure through our pilot study, but it does not transfer fully. Next, our sample size was moderately small, but we still found significance, and our sample size is similar to other research among MOCs (Krause and Van Thiel Citation2019) and cannot be improved by virtue of the small populations of MOCs. Nonetheless, if our respondents are not fully representative of the population, there may be non-response bias in our findings, and we cannot prove the nonexistence of this bias. Finally, this study used self-reported measures, which may be subject to desirability bias, although this was mitigated by using very specific (and in the case of our independent variables objectively verifiable) indicators and informing our respondents clearly of the anonymity of their responses following EU GDPR regulation. We note that even if common-method bias increases the likelihood of false positives (see Meier & O’Toole, Citation2013b, 447), nearly all our findings remain significant under very conservative p-values.

Overall, we found evidence that the introduction of business-like service delivery is critical for making corporatization work effectively, and that autonomy in human resources helps create an environment where such business-like service delivery flourishes. We encourage academics to take into account business techniques’ mediating effect on the autonomy-performance link for corporatization, and encourage practitioners to account for the fact that corporatization may not drive performance by itself, but requires active policy to induce business-like delivery of public services. In addition, it might be fruitful to study in the future if corporatization is required to induce business techniques in public service delivery.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Bart Voorn

Bart Voorn is a PhD researcher at the Institute for Management Research at Radboud University, Nijmegen, the Netherlands. His research focuses on the internal and external management of municipally owned corporations and on their societal effects.

Rick T. Borst

Dr. Rick Borst is an assistant professor at the School of Governance at the Universiteit Utrecht, the Netherlands. He studies the behavior, attitudes, and psychological characteristics of public (i.e. central and local government), and semipublic sector (i.e. healthcare and education) employees and what role (differences and changes in) institutional contexts play.

Rutger Blom

Rutger Blom is a PhD researcher at the Institute of Management Research at the Radboud University, Nijmegen, the Netherlands. His research interests include the influence of context on strategic human resource management and the impact of HRM on employee attitudes and behavior in government agencies.

References

- Aars, Jacob, and Hans-Erik Ringkjøb. 2011. “Local Democracy Ltd: The Political Control of Local Government Enterprises in Norway.” Public Management Review 13 (6):825–44. doi: 10.1080/14719037.2010.539110.

- Anderson, James C., and David W. Gerbing. 1988. “Structural Equation Modeling in Practice: A Review and Recommended Two-Step Approach.” Psychological Bulletin 103 (3):411–23. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411.

- Bergh, Andreas, Gissur Erlingsson, Anders Gustafsson, and Emanuel Wittberg. 2018. “Municipally Owned Enterprises as Danger Zones for Corruption? How Politicians Having Feet in Two Camps May Undermine Conditions for Accountability.” Public Integrity. doi: 10.1080/10999922.2018.1522182.

- Blom, Rutger, Peter M. Kruyen, Beatrice I. J. M. Van der Heijden, and Sandra Van Thiel. 2018. “One HRM Fits All? A Meta-Analysis of the Effects of HRM Practices in the Public, Semipublic, and Private Sector.” Review of Public Personnel Administration 40 (1):3–35. doi: 10.1177/0734371X18773492.

- Blom, Rutger, Peter M. Kruyen, Sandra Van Thiel, and Beatrice I. J. M. Van der Heijden. 2020. "HRM Philosophies and Policies in Semi-Autonomous Agencies: Identification of Important Contextual Factors." The International Journal of Human Resource Management. online first. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2019.1640768

- Boardman, Anthony E., and Aidan R. Vining. 1989. “Ownership and Performance in Competitive Environments: A Comparison of the Performance of Private, Mixed, and State-Owned Enterprises.” The Journal of Law and Economics 32 (1):1–33. doi: 10.1086/467167.

- Bourdeaux, Carolyn. 2005. “A Question of Genesis: An Analysis of the Determinants of Public Authorities.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 15 (3):441–62. doi: 10.1093/jopart/mui020.

- Bourdeaux, Carolyn. 2007. “Reexamining the Claim of Public Authority Efficacy.” Administration & Society 39 (1):77–106.

- Bourdeaux, Carolyn. 2007. “Politics versus Professionalism: The Effect of Institutional Structure on Democratic Decision Making in a Contested Policy Arena.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 18 (3):349–73. doi: 10.1093/jopart/mum010.

- Bowerman, Bruce L., and Richard T. O'Connell. 1990. Linear Statistical Models: An Applied Approach. Belmont, CA: Duxbury.

- Brannick, Michael T., David Chan, James M. Conway, Charles E. Lance, and Paul E. Spector. 2010. “What is Method Variance and How Can we Cope with It? a Panel Discussion.” Organizational Research Methods 13 (3):407–20. doi: 10.1177/1094428109360993.

- Brown, Kerry. 2004. “Human Resource Management in the Public Sector.” Public Management Review 6 (3):303–9. doi: 10.1080/1471903042000256501.

- Brown, Timothy A. 2006. Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Burke, Ronald J., Andrew T. Noble, and CaryL. Cooper. 2013. Human Resource Management in the Public Sector. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Byrne, Barbara M. 2012. Structural Equation Modeling with Mplus. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis.

- Cambini, Carlo, Massimo Filippini, Massimiliano Piacenza, and Davide Vannoni. 2011. “Corporatization and Firm Performance: evidence from Publicly-Provided Local Utilities.” Review of Law & Economics 7 (1):191–213. doi: 10.2202/1555-5879.1428.

- Tom, Christensen, and Per Laegreid. 2006. Autonomy and Regulation: Coping with Agencies in the Modern State. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Citroni, Giulio, Andrea Lippi, and Stefania Profeti. 2013. “Remapping the State: Inter-Municipal Cooperation through Corporatisation and Public-Private Governance Structures.” Local Government Studies 39 (2):208–34. doi: 10.1080/03003930.2012.707615.

- Citroni, Giulio, Andrea Lippi, and Stefania Profeti. 2015. “Representation through Corporatisation: Municipal Corporations in Italy as Arenas for Local Democracy.” European Political Science Review 7 (1):63–92. doi: 10.1017/S1755773914000058.

- COBRA. 2010. "Common data in the COBRA-research: An outline." COBRA. https://soc.kuleuven.be/io/cost/survey/surv_core.pdf.

- Combs, James, Yongmei Liu, Angela Hall, and David Ketchen. 2006. “How Much Do High‐Performance Work Practices Matter? A Meta‐Analysis of Their Effects on Organizational Performance.” Personnel Psychology 59 (3):501–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.2006.00045.x.

- Da Cruz, Nuno F., and Rui C. Marques. 2011. “Viability of Municipal Companies in the Provision of Urban Infrastructure Services.” Local Government Studies 37 (1):93–110. doi: 10.1080/03003930.2010.548551.

- Egeberg, Morten, and Jarle Trondal. 2009. “Political Leadership and Bureaucratic Autonomy: Effects of Agencification.” Governance 22 (4):673–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0491.2009.01458.x.

- Ferry, Laurence, Rhys Andrews, Chris Skelcher, and Piotr Wegorowski. 2018. “New Development: Corporatization of Local Authorities in England in the Wake of Austerity 2010–2016.” Public Money & Management 38 (6):477–80.

- Fornell, Claes, and David F. Larcker. 1981. “Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error.” Journal of Marketing Research 18(3):382–8. doi: 10.1177/002224378101800313.

- Gradus, Raymond H. J. M., and Tjerk Budding. 2018. “Political and Institutional Explanations for Increasing Re-Municipalization.” Urban Affairs Review 56 (2):538–64. doi: 10.1177/1078087418787907.

- Grossi, Giuseppe, and Christoph Reichard. 2008. “Municipal Corporatization in Germany and Italy.” Public Management Review 10 (5):597–617. doi: 10.1080/14719030802264275.

- Hu, Li-tze, and Peter M. Bentler. 1999. “Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria versus New Alternatives.” Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 6(1):1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118.

- Jakobsen, Morten, and Rasmus Jensen. 2015. “Common Method Bias in Public Management Studies.” International Public Management Journal 18 (1):3–30. doi: 10.1080/10967494.2014.997906.

- Jiang, Kaifeng, David P. Lepak, Jia Hu, and Judith C. Baer. 2012. “How Does Human Resource Management Influence Organizational Outcomes? A Meta-Analytic Investigation of Mediating Mechanisms.” Academy of Management Journal 55 (6):1264–94. doi: 10.5465/amj.2011.0088.

- Kline, RexB. 2010. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Krause, Tobias, and Sandra Van Thiel. 2019. “Perceived Managerial Autonomy in Municipally Owned Corporations: Disentangling the Impact of Output Control, Process Control, and Policy-Profession Conflict.” Public Management Review 21 (2):187–211. doi: 10.1080/14719037.2018.1473472.

- Leavitt, William M., and John C. Morris. 2004. “In Search of Middle Ground: The Public Authority as an Alternative to Privatization.” Public Works Management & Policy 9 (2):154–63.

- Lioukas, Spyros, Dimitris Bourantas, and Vassilis Papadakis. 1993. “Managerial Autonomy of State-Owned Enterprises: Determining Factors.” Organization Science 4 (4):645–66. doi: 10.1287/orsc.4.4.645.

- Luu, Tuan. 2018. “Discretionary HR Practices and Proactive Work Behaviour: The Mediation Role of Affective Commitment and the Moderation Roles of PSM and Abusive Supervision.” Public Management Review 20 (6):789–823. doi: 10.1080/14719037.2017.1335342.

- MacKinnon, DavidP. 2008. Introduction to Statistical Mediation Analysis, Multivariate Applications Series. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis Group/Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Meier, Kenneth J., and Laurence J. O'Toole Jr. 2013a. “I Think (I am Doing Well), Therefore I am: Assessing the Validity of Administrators' Self-Assessments of Performance.” International Public Management Journal 16 (1):1–27. doi: 10.1080/10967494.2013.796253.

- Meier, Kenneth J., and Laurence J. O'Toole. 2013b. “Subjective Organizational Performance and Measurement Error: Common Source Bias and Spurious Relationships.” Journal of Public Administr ation Research and Theory 23 (2):429–56. doi: 10.1093/jopart/mus057.

- Muthén, Bengt O., Linda K. Muthén, and Tihomir Asparouhov. 2016. Regression and Mediation Analysis Using Mplus. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén.

- Nelson, Harry W., and William Nikolakis. 2012. “How Does Corporatization Improve the Performance of Government Agencies? Lessons from the Restructuring of State-Owned Forest Agencies in Australia.” International Public Management Journal 15 (3):364–91. doi: 10.1080/10967494.2012.725323.

- Overman, Sjors. 2016. “Great Expectations of Public Service Delegation: A Systematic Review.” Public Management Review 18 (8):1238–62. doi: 10.1080/14719037.2015.1103891.

- Overman, Sjors. 2017. “Autonomous Agencies, Happy Citizens? Challenging the Satisfaction Claim.” Governance 30 (2):211–27. doi: 10.1111/gove.12207.

- Overman, Sjors, and Sandra Van Thiel. 2016. “Agencification and Public Sector Performance: A Systematic Comparison in 20 Countries.” Public Management Review 18 (4):611–35. doi: 10.1080/14719037.2015.1028973.

- Papenfuß, Ulf, Marieke Van Genugten, Johan De Kruijf, and Sandra Van Thiel. 2018. “Implementation of EU Initiatives on Gender Diversity and Executive Directors’ Pay in Municipally-Owned Enterprises in Germany and The Netherlands.” Public Money & Management 38 (2):87–96.

- Pérez-López, Gemma, Diego Prior, and José L. Zafra-Gómez. 2015. “Rethinking New Public Management Delivery Forms and Efficiency: Long-Term Effects in Spanish Local Government.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 25 (4):1157–83. doi: 10.1093/jopart/muu088.

- Pollitt, Christopher, and Geert Bouckaert. 2011. Public Management Reform: A Comparative Analysis: New Public Management, Governance, and the Neo-Weberian State. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Pollitt, Christopher, and Sorin Dan. 2013. “Searching for Impacts in Performance-Oriented Management Reform: A Review of the European Literature.” Public Performance & Management Review 37 (1):7–32.

- Rodrigues, Miguel, António F. Tavares, and J. Filipe Araújo. 2012. “Municipal Service Delivery: The Role of Transaction Costs in the Choice between Alternative Governance Mechanisms.” Local Government Studies 38 (5):615–38. doi: 10.1080/03003930.2012.666211.

- Sobel, Michael E. 1982. “Asymptotic Confidence Intervals for Indirect Effects in Structural Equation Models.” Sociological Methodology 13:290–312. doi: 10.2307/270723.

- Swarts, Douglas, and Mildred E. Warner. 2014. “Hybrid Firms and Transit Delivery: The Case of Berlin.” Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics 85 (1):127–46. doi: 10.1111/apce.12026.

- Tavares, António F. 2017. “Ten Years after: Revisiting the Determinants of the Adoption of Municipal Corporations for Local Service Delivery.” Local Government Studies 43 (5):697–706. doi: 10.1080/03003930.2017.1356723.

- Tavares, António F., and Pedro J. Camões. 2007. “Local Service Delivery Choices in Portugal: A Political Transaction Costs Framework.” Local Government Studies 33 (4):535–53. doi: 10.1080/03003930701417544.

- Taylor, Aaron B., David P. MacKinnon, and Jenn-Yun Tein. 2008. “Tests of the Three-Path Mediated Effect.” Organizational Research Methods 11 (2):241–69. doi: 10.1177/1094428107300344.

- Torsteinsen, Harald. 2019. “Debate: Corporatization in Local government - The Need for a Comparative and Multi-Disciplinary Research Approach.” Public Money & Management 39 (1):5–8. doi: 10.1080/09540962.2019.1537702.

- Torsteinsen, Harald, Marieke Van Genugten, Łukasz Mikuła, Carla P. Mussons, and Esther P. Puey. 2018. “Effects of External Agentification in Local Government: A European Comparison of Municipal Waste Management.” In Evaluating Reforms of Local Public and Social Services in Europe, edited by Ivan Koprić and Hellmut Wollmann, 171–89. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Van Genugten, Marieke, Bart Voorn, and Sandra Van Thiel. 2020. “Local Governments and Their Arm’s Length Bodies.” Local Government Studies 46 (1):1–21. doi: 10.1080/03003930.2019.1667774.

- Van Thiel, Sandra, Koen Verhoest, Geert Bouckaert, and Per Loegreid. 2012. “Lessons and Recommendations for the Practice of Agencification.” In Government Agencies, 413–39. London: Springer.

- Van Thiel, Sandra, and Kutsal Yesilkagit. 2011. “Good Neighbours or Distant Friends? Trust between Dutch Ministries and Their Executive Agencies.” Public Management Review 13 (6):783–802. doi: 10.1080/14719037.2010.539111.

- Verhoest, Koen. 2005. “Effects of Autonomy, Performance Contracting, and Competition on the Performance of a Public Agency: A Case Study.” Policy Studies Journal 33 (2):235–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0072.2005.00104.x.

- Verhoest, Koen, B. Guy Peters, Geert Bouckaert, and Bram Verschuere. 2004. “The Study of Organisational Autonomy: A Conceptual Review.” Public Administration and Development 24 (2):101–18. doi: 10.1002/pad.316.

- Verhoest, Koen, PaulG. Roness, Bram Verschuere, Kristin Rubecksen, and Muiris MacCarthaigh. 2010. Autonomy and Control of State Agencies: Comparing States and Agencies. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Verhoest, Koen, Sandra Van Thiel, Geert Bouckaert, and Per Laegreid. 2012. Government Agencies: Practices and Lessons from 30 Countries. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Verhoest, Koen, Sandra Van Thiel, Per Laegreid, Geert Bouckaert, Guy Peters, Tobias Bach, and Dario Barbieri. 2004. "Joint COBRA database on autonomy, control and internal features of public sector organizations (open version)." Collected and built by the Comparative Public Organization Data Base for Research and Analysis – network. Accessible through https://soc.kuleuven.be/io/cost/survey/index.htm.

- Verhoest, Koen, Bram Verschuere, and Geert Bouckaert. 2007. “Pressure, Legitimacy, and Innovative Behavior by Public Organizations.” Governance 20 (3):469–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0491.2007.00367.x.

- Verhoest, Koen, and Jan Wynen. 2018. “Why Do Autonomous Public Agencies Use Performance Management Techniques? Revisiting the Role of Basic Organizational Characteristics.” International Public Management Journal 21 (4):619–49. doi: 10.1080/10967494.2016.1199448.

- Vining, Aiden R., Claude Laurin, and David Weimer. 2015. “The Longer-Run Performance Effects of Agencification: Theory and Evidence from Québec Agencies.” Journal of Public Policy 35 (2):193–222. doi: 10.1017/S0143814X14000245.

- Voorn, Bart, Marieke Van Genugten, and Sandra Van Thiel. 2017. “The Efficiency and Effectiveness of Municipally Owned Corporations: A Systematic Review.” Local Government Studies 43 (5):820–41. doi: 10.1080/03003930.2017.1319360.

- Voorn, Bart, Marieke Van Genugten, and Sandra Van Thiel. 2019. “Re-Interpreting Re-Municipalization: Finding Equilibrium.” Journal of Economic Policy Reform. Online First. doi: 10.1080/17487870.2019.1701455.

- Voorn, Bart, Marieke Van Genugten, and Sandra Van Thiel. 2020. “Performance of Municipally Owned Corporations: Determinants and Mechanisms.” Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics 91 (2):191–212. doi: 10.1111/apce.12268.

- Voorn, Bart, Sandra Van Thiel, and Marieke Van Genugten. 2018. “Debate: Corporatization as More than a Recent Crisis-Driven Development.” Public Money & Management 38 (7):481–2. doi: 10.1080/09540962.2018.1527533.

- Wettenhall, Roger. 2005. “Agencies and Non-Departmental Public Bodies: The Hard and Soft Lenses of Agencification Theory.” Public Management Review 7 (4):615–35. doi: 10.1080/14719030500362827.

- Wynen, Jan, Koen Verhoest, Edoardo Ongaro, and Sandra Van Thiel. 2014. “Innovation-Oriented Culture in the Public Sector: Do Managerial Autonomy and Result Control Lead to Innovation?” Public Management Review 16 (1):45–66.

- Wynen, Jan, Koen Verhoest, and Kristin Rübecksen. 2014. “Decentralization in Public Sector Organizations: Do Organizational Autonomy and Result Control Lead to Decentralization toward Lower Hierarchical Levels?” Public Performance & Management Review 37 (3):496–520.

- Yesilkagit, Kutsal, and Sandra Van Thiel. 2008. “Political Influence and Bureaucratic Autonomy.” Public Organization Review 8 (2):137–53. doi: 10.1007/s11115-008-0054-7.

- Yesilkagit, Kutsal, and Sandra Van Thiel. 2012. “Autonomous Agencies and Perceptions of Stakeholder Influence in Parliamentary Democracies.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 22(1):101–19. doi: 10.1093/jopart/mur001.