Abstract

This article theorizes equality and inclusion in coproduction, from the perspective of public administrators. Coproduction may occur across the policy cycle and at the individual, group, and collective levels, and for reasons of both instrumentality (such as improved efficiency) and normativity (such as democracy). Participation of the disadvantaged in various modes of coproduction is essential if the solidarity principle (stipulating prioritization of those in greatest need) is to be taken seriously. However, their access may be hindered due to external exclusion (not having a place) and internal exclusion (not having a say). Whether inclusion of the disadvantaged is argued for in terms of sameness or difference, different reasons are addressed: justice (for the former) as well as additional perspectives and resources (for the latter). Policymakers and practitioners need to recognize that strategies of equality are likely to differ at various levels and modes of coproduction.

Introduction

The value of coproduction is well-recognized (Andersen, Boye, and Laursen Citation2018; Thomsen and Jakobsen Citation2015), and recent decades have seen the reemergence of coproduction in public administration and management literature (Isett and Miranda Citation2015). Coproduction offers an alternative to both traditional public administration, in which services are delivered by employees to laypeople who consume them (Bovaird Citation2007; Brandsen and Honingh Citation2016), and market-based models, in which patients, students, and citizens become customers (Ostrom Citation1996; Pestoff Citation2006). Moreover, lay engagement in general (Nabatchi Citation2010a), and coproduction in particular (Pestoff Citation2006), is considered important for addressing democracy deficits. Thus, “public administration scholarship should focus much more on the role of citizens and citizen-state interactions” (Jakobsen et al. Citation2019, 1).

Since the first developments over four decades ago (Ostrom Citation1972, Parks et al. Citation1981; Percy Citation1978), many researchers have contributed to coproduction knowledge. Initially, they did so from the standpoint that traditional citizen participation had reinforced traditional government–citizen relationships in which citizens were considered merely as consumers or evaluators of public services (Sharp Citation1980). By contrast, coproduction emphasized joint responsibility for the public service delivery, with citizens considered to be active and important resources (Percy Citation1984). Still, coproduction is often distinguished from citizen participation in that the intensity of citizen contribution in the latter is typically lower (Loeffler Citation2021). The traditional focus of coproduction on the delivery phase is still favored by some scholars (e.g., Brandsen and Honingh Citation2018; Voorberg, Bekkers, and Tummers Citation2015), but contemporary scholars more often argue that coproduction can occur in all phases of a policy cycle (Bovaird and Loeffler Citation2012; Jakobsen et al. Citation2019; Nabatchi, Sancino, and Sicilia Citation2017): planning, design/improvement, delivery, and assessment. Similarly, coproduction can cover activities from face-to-face interactions between individual clients and employees (Normann Citation2001) to deliberative forums involving many citizens and employees (Munno and Nabatchi Citation2014). Thus, coproduction must involve interactive efforts between citizens and employees in direct ways (Bovaird et al. Citation2016) with significant contributions from both parties (Parks et al. Citation1981). Following this logic, it is clear what should not be considered coproduction, for example; voting, paying taxes, self-care, community self-organization (Alford Citation2009; Ostrom Citation1996), as well as one-way information to laypeople without the real possibility of influence (Bovaird et al. Citation2016).

Lately, coproduction has often been confused with cocreation (Voorberg et al. Citation2015), a newcomer in the public sector, originating from the private sector (Brandsen and Honingh Citation2018; Strokosch and Osborne Citation2020). While there are many similarities between the concepts, the traditional definition of coproduction to address service delivery is narrower than that of cocreation, which also concerns the planning and design phases (Brandsen and Honingh Citation2018). To others, coproduction may be understood as one of many cocreation activities (Hardyman, Daunt, and Kitchener Citation2015). Osborne (Citation2018) argued that coproduction stems from a manufacturing industry (and goods) dominance and linear logic of service delivery, whereas cocreation emphasizes dynamic and interactive relationships. Whereas coproduction rarely focuses beyond the dyad of employees of public organizations and citizens, the developments of cocreation have increasingly focused on how value is cocreated among public, private, and third sectors actors in complex public service ecosystems (e.g., Eriksson and Hellström Citation2021; Petrescu Citation2019).

The present paper adopts the broader definition of coproduction, ranging from planning to assessing public services. The paper theorizes that coproduction must return to the worries raised in the 1980s about coproduction and equality (Brudney and England Citation1983; Rosentraub and Sharp Citation1981). Although equality has been considered equally important to efficiency and effectiveness in public administration for over 50 years (Gooden and Portillo Citation2011), little attention has been given to whether coproduction benefits groups in greatest need or those better off (Jakobsen Citation2013; Jakobsen and Andersen Citation2013).

By linking equality and empirical findings to previous models of coproduction – in particular, the Four Cos Model of Bovaird and Loeffler (Citation2013) and the developments of the model regarding the level of coproduction by Nabatchi et al. (Citation2017) – this article seeks to contribute to theory-building while at the same time addressing a claimed shortcoming of recent coproduction literature: “The cumulative effect of past research still remains relatively weak” (Brandsen and Honingh Citation2018, 9). The present paper theorizes public administrators’ beliefs and perceptions of citizen participation in coproduction. I ask: What meaning and purpose do public administrators attach to inclusion in coproduction? Inclusion needs to be twofold: (1) patient inclusion in participating with administrators to produce services, and (2) including the disadvantaged in coproduction. As mentioned, coproduction must involve efforts of both citizens and public administrators (e.g., Bovaird et al. Citation2016). However, like other studies on coproduction (e.g., Van Eijk and Steen Citation2014), I argue that data collected from one perspective only can make an important contribution to coproduction theory and practice. Increased knowledge from a public administrator’s perspective is essential, as they are in position to both enable and hinder equitable coproduction.

The next section presents coproduction theory, focusing on modes across the service delivery phase, levels of coproduction (as in who provides input and enjoys benefit), as well as reasons for including laypeople. In the following subsection I discuss the essential dimensions of equality (and the relation to the equity concept), presenting reasons to include the disadvantaged in decision-making. The next section provides methodological considerations and presents the empirical case, in which Swedish public administrators were interviewed. The findings of these interviews are presented, followed by a discussion of reasons and modes of coproduction based on the Four Cos of coproduction (Bovaird and Loeffler Citation2013) and developments of the model regarding levels of coproduction (Nabatchi et al. Citation2017); coproduction and equality; and an elaboration of inclusion focusing on equality in and of coproduction. The paper concludes by highlighting the potential to reduce inequalities by including disadvantaged in certain modes of coproduction.

Theory

Reasons, modes, and levels of coproduction

A common reason for coproduction is that it will improve the efficiency, effectiveness, and innovativeness of public services (Neshkova and Guo Citation2012; Vamstad Citation2012). Coproduction is seen as a means of also achieving the ends of the involved individual laypeople (satisfaction and empowerment) or group members (inclusion and equality) themselves (Vanleene, Voets, and Verschuere Citation2018), as well as contributing to the common good (Alford Citation2002, Citation2009; Nabatchi et al. Citation2017). Coproduction may also be argued for based on normative reasons and as a virtue in itself, such as addressing the democratic ideal (Michels Citation2011) or social capital (Nabatchi et al. Citation2017).

However, coproduction is not about a tradeoff between normative reasons based on democracy, bottom-up approaches and equality versus instrumentality based on hierarchy, top-down approaches, efficiency and effectiveness (Munno and Nabatchi Citation2014; Nabatchi Citation2010b; Denhardt and Denhardt Citation2006), as shown in Moynihan’s (Citation2003) empirical study of Washington DC’s citizen summits in which instrumental motives can address normative goals.

The modes of coproduction are elaborated in the Four Cos Model (e.g., Bovaird and Loeffler Citation2013; Loeffler and Bovaird Citation2019). In cocommissioning, citizens work together with public administrators in deliberative processes to address policy planning, crowdfunding, procurement panels, prioritization of policies or budgets, and areas to prioritize for the police, schools, and so forth (Loeffler Citation2021; Loeffler and Bovaird Citation2019; Nabatchi et al. Citation2017). These issues have traditionally been the concern for politicians and top managers; through cocommissioning, however, questions about what needs to be delivered, to whom, and what outcomes are desirable are jointly considered with citizens, including prioritization of outcomes and groups in society prioritized to target (Bovaird and Loeffler Citation2013). Codesign includes user involvement in consultation, participation in design labs, mapping of journeys through the concerned public service, improvements of public authorities’ websites, as well as the application process for benefits and so forth (Loeffler and Bovaird Citation2019; Nabatchi et al. Citation2017). Regardless of the activity, the idea is to bring in the experience of citizens and their communities into the design and development of public services (Bovaird and Loeffler Citation2013). Codelivery is about delivering public services together. This includes sharing of knowledge and experiences to peers, promotion and support of selfcare, and participating as school governors (Bovaird and Loeffler Citation2013; Loeffler and Bovaird Citation2019) Finally, coassessment includes activities ranging from user online ratings to tenant inspectors. While surveys and focus groups are often used to coassess, more intense forms such as user inspection and participation in auditing are increasingly used to offer the user’s inside perspective (Bovaird and Loeffler Citation2013).

Apart from codelivery, all of the modes mainly involve citizen voice to engage with public administrators. Codelivery mainly concerns citizen action in improving a public service (Loeffler Citation2021). According to Loeffler and Bovaird (Citation2019), the possibilities to also engage through action are important, since not all citizens appreciate engagement through discussions. Nabatchi et al. (Citation2017) added the temporal nature to the four modes, in which cocommissioning is prospective, codelivery concurrent, codesign may be both prospective and concurrent, and coassessment is mainly retrospective.

Concerning levels, coproduction can be done by laypeople providing input individually or as a collective (Bovaird et al. Citation2016; Brudney and England Citation1983). Moreover, the output of coproduction activities can benefit the individuals themselves or collectives (Bovaird et al. Citation2016). Contrary to Bovaird et al. (Citation2016), others (Brudney and England Citation1983; Nabatchi et al. Citation2017) have separated the “collective level” into groups and the whole collective or community (henceforth, individual, group, and collective levels will be used). In practice, the benefit may “spill-over” to other levels (Nabatchi et al. Citation2017). Individuals may also experience stress, stigma, and loss of autonomy by coproducing (Thomsen, Baekgaard, and Jensen Citation2020).

Bovaird et al. (Citation2016) argued that the public administration literature in the 1970s regarded coproduction mainly as an individual practice. Alford (Citation2002, Citation2009) emphasized the individual level because the individual service user/client not only contributes with input, but also consumes the public service, something that volunteers (at the group level) or citizens (at the collective level) do not do. Nabatchi et al. (Citation2017) offered a similar distinction of roles, separating the individual level into clients (do not pay directly for the public service) and customers (pay directly for the public service). Alford (Citation2009) argued that individual coproduction should be favored when focusing on the individualization of services and customer needs, similar to the literature drawing mainly from private sector (Normann Citation2001; Ramirez Citation1999). During the 1980s, coproduction shifted toward a collective – group or public – practice (Brudney and England Citation1983). These collective levels have been emphasized as important because they have the potential to lead to a communality of benefits, which is important in public services that are not only to benefit the individual person (Brudney and England Citation1983; Rosentraub and Sharp Citation1981).

Collective coproduction requires more. For example, it may be challenging to achieve trust established and nurtured through relationships in collective forms (Fledderus, Brandsen, and Honingh Citation2015; Joshi and Moore Citation2004). Moreover, collective coproduction often requires formalized coordination mechanisms between staff and laypeople (Brudney and England Citation1983). The relatively complicated nature of collective forms may be a reason why laypeople seem to favor individual coproduction over collective (Bovaird and Loeffler Citation2009; Bovaird et al. Citation2016).

Pestoff (Citation2014) argued that each level has its own goals: individual coproduction often concerns ad hoc and spontaneous services, collective coproduction concerns sustainable welfare services, and group coproduction can impact both coproducing individuals and the addressed issues, and therefore the common good. Similarly, Nabatchi et al. (Citation2017) defined coproduction as an umbrella term covering multiple levels, actors, activities, and reasons – and what is “best” depends on the purpose.

According to Jakobsen (Citation2013) and Jakobsen and Andersen (Citation2013), little attention has been given to whether coproduction initiatives affect those in greatest need for the service or advantaged populations with less need for the service. A well-known risk of allowing laypeople to participate voluntarily is that they are often “better off” in terms of education, income, etc. (Fung Citation2003), particularly for collective forms (Brudney and England Citation1983; Warren, Rosentraub, and Harlow Citation1984). Thus, values of that privileged group will be highlighted and not mirror society (Church et al. Citation2002; Nabatchi Citation2012). Simultaneously, the disadvantaged risk to be excluded in coproduction (Brandsen and Honingh Citation2016; Cepiku and Giordano Citation2014), so coproduction may reinforce inequalities due to differences in resources and devotion of time between people (Van Ryzin, Riccucci, and Li Citation2017; Williams, Kang, and Johnson Citation2016). Thus, the worry raised by Rosentraub and Sharp (Citation1981, 517) remains highly relevant:

“Implicitly, coproduction appears to raise equity issues. Wealthier, better-educated, or non-minority citizens may be more willing or able to engage in coproduction activities. To the extent that coproduction raises the quality of services received, it may exacerbate gaps between the advantaged and disadvantaged classes.”

Various strategies to minimize inclusion bias have been suggested, including random selection (Nabatchi Citation2012); demographic recruitment to increase broad representativeness in the population (Fung Citation2003; Nabatchi Citation2012); lowering the barriers for participation for groups known not to do so (Brudney and England Citation1983; Williams et al. Citation2016); or using incentives such as payment, transportation, or meals (Fung Citation2003; Nabatchi Citation2012). Non-material motives to coproduce may be most important, such as social values by interacting with others as well as normative values based on democracy and citizenry (Eriksson Citation2019). Similarly, helping others and making a difference were important reasons for individuals (Bovaird and Loeffler Citation2009) and collectives (Bovaird et al. Citation2016) to coproduce.

Equality

The equity concept is often used within the context of this article: healthcare. The difference between the equity concept and the equality concept is often described as being that equity is value-based, fair and normative, whereas equality addresses being equal in opportunities, rights, status, and so forth (Braveman and Gruskin Citation2003; Carter-Pokras and Baquet Citation2002). From the standpoint of these definitions, the former is often favored in a healthcare context: “Equity does not mean that everybody should […] consume the same amount of health service resources irrespective of need” (Whitehead Citation1990, 15).

However, the concept of equality is more complex than described above, in which equality is more or less synonymous with sameness. In a broader public sector context, Le Grand (Citation1982) distinguished among five dimensions of equality fundamental to policy of public expenditure on the social services. Equality of public expenditure is similar to the “sameness” of the concept, as in the previous paragraph, in that individuals should receive the same amount of a particular public service. In equality of final income, expenditure on public services should be allocated to favor the poor so that their “final income” (private income plus values from received public services) becomes – through redistribution – less unequal to those better off. Le Grand (Citation1982) used an example from NHS (equally relevant in a Scandinavian healthcare context almost four decades later) of equal treatment for equal need to describe equality of use. In equality of cost, allocation should be done in a way that “all relevant individuals face the same cost per ‘unit’ of the service used” (Le Grand Citation1982, 15). For instance, the cost (moneywise, timewise) to consult a physician should be the same for all individuals. Finally, in equality of outcome, expenditures should be “allocated so as to promote equality in the ‘outcome’ associated with a particular service” (Le Grand Citation1982, 15). Naturally, the outcomes vary among services, but may be an individual’s health for healthcare services, or extra income as a consequence of education.

A major division in political philosophy and democratic theory is that between equality of outcome and equality of opportunity, or in the words of Phillips (Citation2004, 1): “equalizing where people end up rather than where or how they begin.” The opportunity approach, at its most basic, addresses issues such as equal opportunities through standardized public education in a society in order to offer equal opportunities independent of sex, class, ethnicity, and region in the society, and so forth (an example used in a similar way by Le Grand [Citation1982] to exemplify equality of use). Thus, all individuals within a group must have the same opportunities to achieve the same desirable goal, but also risk facing the same obstacles (Kymlicka Citation1995). A matter of debate in the equality of opportunity view is what one seeks to equalize. Rawls (Citation1971) focused on “primary goods” that are desirable and useful for all people, such as health, rights, income. Dworkin (Citation1981) focused on resources (as income and wealth) that are considered unequal when reflecting factors of bad luck, such as distribution of physical endowments, but not regarding ambition. Sen’s (Citation2005) capability approach focused on what people are capable of achieving rather than having the rights or freedoms to do, not least basic capabilities such as being clothed and sheltered, participating in the social life of their community, meeting nutritional requirements, and so on. Thus, some sources of inequalities are legitimate and others are illegitimate, within and, respectively, beyond people’s control. In healthcare, it becomes central to investigate whether sources explaining differences in access or use of healthcare services are justified. For instance, differences in access or use due to health status is a legitimate source of inequalities, whereas the same due to socioeconomic status is considered an illegitimate source of inequalities (Fleurbaey and Schokkaert Citation2011).

According to Phillips (Citation2004), the opportunity approach is often favored in both practice and policy since it is rather uncontroversial to claim that all should have the same opportunities to thrive. The outcome approach promotes that wealth and money should be equalized, as they are often a result of injustices. Consequently, the outcome approach is often accused of denying choice and responsibility (Phillips Citation2004). Criticism of the opportunity approach also includes an overly narrow definition of time, which often focuses exclusively on equal opportunities at birth and graduation (Therborn Citation2014). After that, individuals are left on their own and their outcome is solely their own responsibility. However, many events in life (after graduation) occur regardless of effort: for instance, divorce or stressful working life may lead to reduced income or sickness that may, at worst, lead to poverty (Therborn Citation2014) – so-called “bad luck” scenarios, as articulated by Phillips (Citation2004). Therborn (Citation2014) provided empirical examples illustrating that, regardless of offering equal opportunities, the equality of outcome (in terms of income) within a society will vary (and between societies with similar opportunities). Molander (Citation2015) illustrated that if two children play marbles – starting the game with the same number of marbles and the same level of skill – one of them will inevitably end with more marbles than the other. The income aspect was also emphasized by Le Grand (Citation1982), affecting inequalities in outcome. For instance, a child’s socioeconomic background may affect their educational achievement more than the education itself, and income may affect nutrition intake, and thus health, more than healthcare services do. Underpinned by empirical cases, Le Grand (Citation1982) concluded that greater public expenditure on individual public services has often failed to increase equality. Instead, equalizing income through redistribution offers a more promising way “of achieving equality of whatever kind” (Le Grand Citation1982, 140, italics in original).

Political philosophy and democratic theory include yet other dimensions of equality. An example is equality of representation, which often addresses formal decision-making institutions, such as equal gender representation (e.g., Hernes Citation1987) or ethnicity (e.g., Griffin and Newman Citation2007) in parliaments as well as within other organizations, such as associations (Fung Citation2003). If a certain sub-group’s preferences are not heard, or are suppressed even, representation is unequal “as it contrasts sharply with the principles of a fully democratic society” (Lefkofridi, Giger, and Kissau Citation2012, 1). Equality of influence may be expressed through individuals’ equal possibilities to vote, as well as other ways to participate in the public discourse to make their voices heard (Post Citation2006). This is a delicate issue since sources of influence are broad, or, as Dworkin put it (Citation2003, 196): “We want to eliminate, to the degree we can, extra influence that comes from money. But we certainly do not want to eliminate extra influence that comes from a powerful mind or infectious idealism, and that is why I reject equality of influence as a goal.”

In sum, equity in a healthcare context is often needs-based (Whitehead Citation1990) and in this sense often aligns with equality of opportunity (Kymlicka Citation1995) in which legitimate inequalities due to differences in health status are accepted (Fleurbaey and Schokkaert Citation2011). In cases in which people have the same needs, they should be offered equal treatment, as in equality of use (Le Grand Citation1982). However, equity is also about fairness (Braveman and Gruskin Citation2003) and, in this sense, aligns with the non-acceptance of illegitimate inequalities of equality of opportunity due to socioeconomic background and other factors (Fleurbaey and Schokkaert Citation2011). Because illegitimate inequalities due to such factors are empirically well-documented, equality of representation of the disadvantaged in formal decision-making in various forms of organizations, as well as equality of influence to make their voices heard (Post Citation2006), may be important for counteracting such realities. Thus, including the disadvantaged in various forums may be a way of improving the services that are relevant for the disadvantaged or those in greatest need (Jakobsen Citation2013) and, by so doing, may contribute to equality of outcome (Le Grand Citation1982), or health in a healthcare context.

Inclusion of the disadvantaged

Because oppression and domination are often structural and manifested in unconscious acts of well-meaning people in everyday interactions, inequalities cannot be legislated away (Young Citation1990). Young (Citation2000) distinguished between external exclusion (certain people are not included in the participating group at all) and internal exclusion (participants do not have equal opportunities to voice their opinions and raise questions). Terms such as “citizenry,” “diversity,” and “multiculturalism” have often served as normalization processes (Young Citation2006) in which some voices dominate and there is no room for differences – imitation of the dominant is seen as desirable (Kymlicka Citation1995). Similarly, Taylor (Citation1995) argued that equalizing may force people into uniformity. Consequently, dominant perspectives are “often taken as neutral and universal” (Young Citation2000, 144), but would be revealed as one of many (specific, partial) perspectives if excluded perspectives were also represented. Therefore, through public resources and institutional mechanisms, there should be “effective representation and recognition of the distinct voices and perspectives of those of its constituent groups that are oppressed or disadvantaged within it” (Young Citation2006, 254). Thus, there is a need for collective engagement focusing on groups rather than individuals; otherwise, coproduction and other deliberative models will not be able to visualize and bring inequalities and power asymmetries to the surface (Young Citation1990, Citation1997).

It is often argued that the disadvantaged should be included in decision-making because they have different interests or perspectives that will not be targeted otherwise: who is present (“politics of presence”) in decision-making will impact what is discussed (“politics of ideas”) (Phillips Citation2000). The traditional focus on ideas has proved to be largely blind of gender, ethnicity, etc. and is therefore unable to address exclusion from democratic processes of the disadvantaged (Phillips Citation2006). It is essential to focus on the “who” because the presence of women is needed to highlight issues (domestic violence, birth control, underpaid work) faced by their specific position in society – only if disadvantaged groups are present will alternatives to the dominant preferences and experiences be included (Hernes Citation1987; Phillips Citation2000; Young Citation2000). Not all groups can be included, so Young (Citation2006, 257) argued that it is relevant “whenever the group’s history and social situation provide a particular perspective on the issues, when the interest of its members are specifically affected.”

A second, similar argument is that the different positions, interests, and perspectives of the disadvantaged are important resources and that including the disadvantaged may bring new knowledge and experiences that may also benefit the greater good (Young Citation1997). Exclusion is therefore a waste of resources and the disadvantaged should be producers of important decisions, not just consumers (Hernes Citation1987).

A third, justice-based argument is that all groups in society should have a say about issues concerning them (Young Citation2000). Any skewed distribution among groups is evidence of intentional or unintentional structural discrimination and incomplete democracy (Hernes Citation1987; Phillips Citation2000), so no groups should be excluded, no matter if their inclusion would impact the agenda, policy, delivery or not (Hernes Citation1987).

However, an overly unilateral focus based on a substantial logic of people’s shared attributes (skin color, genitalia, etc.), as in “identity politics” (Young Citation2000, Citation2006), can promote a “solitarist approach” (Sen Citation2006) in which the contextual aspect of sense of group-belonging is neglected and in which the dynamic co-existence among intersecting social categories of a person may be important (Walby Citation2007). Such logic may force people into groups (Fraser Citation1995, Citation2007), which may increase intolerance and separatism between them (Gutmann Citation2003; Sen Citation2006). Arguing for a “diversity within unity approach,” Etzioni (Citation2011, 369) suggested “granting some discretion to member communities while also maintaining select values of the most encompassing conceptions of the common good.”

Young (Citation2000, Citation2006) suggested “social group” as a categorization, based on a relation logic that recognizes similarities with those in other groups as well as differences within the group, whereby “individuals construct their own identities on the basis of social group positioning” (Young Citation2000, 82). Their social positioning means that the disadvantaged often have different reasons and solutions for problems (Jónasdóttir Citation1991; Young Citation2000). Others have emphasized that identity recognition should stem from an individual or group’s differences in relation to others (Taylor Citation1995).

Methods

Setting and participants

This article draws from the healthcare system of Western Region of Sweden, the second-largest region in Sweden (2 million inhabitants). Sweden’s 20 regions are responsible for providing healthcare in local hospitals or primary care facilities or through private or third-sector actors. The Swedish Medical Act (SFS Citation2017), supplemented by national guidelines and recommendations, stipulates that everyone has a right to healthcare services, regardless of their background (human value principle); if two treatments or medications have the same effect, the cheaper should be chosen (cost-efficiency principle); and that those in greatest need should be prioritized, with particular care for the disadvantaged (solidarity principle) (SOSFS Citation2005; SOU Citation1995).

Twenty respondents were interviewed about coproduction and related concepts and areas such as person-/patient-centeredness, equality, and inclusion (). They were selected because they represented different levels of the healthcare system and had roles that involved direct contact with citizens. Twelve interviews were conducted with administrators working at an overarching regional level. Some worked mainly with equality in healthcare. Other officials at the regional level were responsible for “patient cocreation” – investigating enabling conditions, structuring and systematizing patient coproduction, etc. – and another administrator coordinated “person-centered care” across the region. Several interviewees worked with the national initiative of the knowledge-driven organization by developing, spreading, and using the best possible knowledge in healthcare (SKR Citation2020) – work that covered national, regional, and local levels of healthcare. Some worked as coordinators for specific process teams (explained in the findings section), while others worked across those teams to develop joint methods. Eight interviews were conducted with people working both at overarching regional level as members of a process team, as well as clinically active healthcare professionals (mainly physicians or nurses) at local primary care centers or hospitals.

Table 1. Interview respondents.

One interview in the “regional and local” group was conducted with a patient representative who was not employed as an administrator, so this interview is not included in the analysis.

This research project was approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (registration number 2019-02280).

Data collection and analysis

A qualitative approach was chosen in order to increase understanding of reasons and difficulties of coproduction from public administrators’ perspectives, and because of the potential to bridge the gap between practitioners and researchers (Ospina, Esteve, and Lee Citation2018). Before data collection began, the Swedish Ethical Review Authority approved the study. The 19 interviews with public administrators form the main empirical material for this article. Secondary data such as documents and other textual data, notes from meetings with managers, the interview with a coproducing patient, and field notes from workshops, was collected and used to look up points mentioned by the respondents, prepare interviews, etc. The interviews were semi-structured and questions were adjusted as the interviews went on. The respondents were provided information and consent when asked to participate in the interviews, and again before the interviews, when verbal and written consent were collected. All respondents agreed to the recording of interviews, which were transcribed verbatim before analysis.

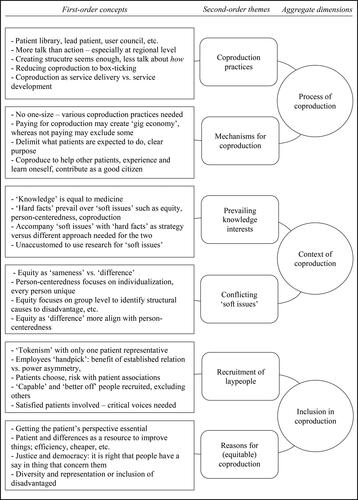

The interviews were analyzed inductively based on the procedure of Corley and Gioia (Citation2004) and Gioia, Corley, and Hamilton (Citation2013). First, data was sorted into first-order concepts, in which the respondents’ expressions and vocabulary were retained as much as possible. Second, analysis continued with second-order themes in which first-order concepts were sorted based on similarities. Third, overarching aggregate dimensions were constructed based on similarities among second-order themes. Saturation (Nowell and Albrecht Citation2019) gradually emerged halfway through the analysis and few new important findings were found in the last two or three interviews. See for the final coding structure.

In order to meet qualitative rigor (Nowell and Albrecht Citation2019) and to ensure that I had not misunderstood anything, the tentative categories were discussed with respondents (n = 8) as well as other stakeholders for validation and member checking (Lincoln and Guba Citation1985). Findings and interpretations were also discussed through peer debriefing with researchers, consultants, lead patients, and practitioners in the field (Lincoln and Guba Citation1985). Prior to the main interviews, I tried to develop a deep understanding of both context and phenomena (Nowell and Albrecht Citation2019) by facilitating a workshop on coproduction in which three regional administrators and four process team members (including an additional patient representative) participated. Three of them were then interviewed for this study. My aim in the preceding and following sections was to provide a thick description that enables readers to consider the transferability to their own contexts (Lincoln and Guba Citation1985).

Results

Process of coproduction

This dimension includes two themes: coproduction practices and the respondents’ experiences of what makes coproduction work or not.

The practices included dialogues with immigrant women, youths, and other groups to identify barriers and solutions to services. In some initiatives the laypeople informed their peers together with professionals. Selected patients were also included in a “patient library” to share their disease-specific or general patient experiences when staff requested them for activities such as developing services. “Lead patients,” who had profound knowledge of their situation living with a chronic disease, were involved with the organization to address how patients could collect their own health data, participate in board meetings and improvement projects, etc. Patients were also asked to provide a patient’s perspective at conferences, in information films, or developing written information. There were also citizen dialogues at various geographical areas, such as segregated areas with many immigrants, although these were considered more as the politicians’ arena. Also mentioned were user councils with association representatives, rather than citizens, discussing healthcare issues with both politicians and officials.

At a regional level, many of the respondents said that coproduction was much talked about and mentioned in official documents, not least because of the person-centered approach that required inclusion of the patients. However, little was done concretely: “We are more than 50,000 employees and there are an endless number of improvement projects going on, but few patients or their relatives are involved.” Some respondents said that the question of how to coproduce remained unanswered because “it seems enough to create a structure.” Interviewees requested opportunities to share good and bad coproduction experiences, bridge the local-regional gap, and to learn from each other within the large region.

One way to decrease the regional-local gap was the process teams. At a regional level, a common idea was to involve a patient in day-long meetings with the other team members (physicians, nurses and other healthcare professionals); the patient would “represent the patient group” in discussions about developing information or improving services. The professional process team members had also asked their own patients questions about overall wellbeing and interactions with healthcare. According to an administrator, some professionals did it reluctantly, arguing that “I meet patients every day, I know what they think,” whereas others had “gotten information that they had never heard before.” However, when the team members sorted the clusters from the interviews, they prioritized the medical aspects rather than the patients’ prioritizations, similar to how input by patients in a workshop was handled. It was argued that the process teams sometimes seemed to “tick the box” of listening and including patients without really doing it.

Many of the professionals in the clinically active teams noted more action on “the front lines,” where staff and patients interacted. However, it was clear that coproduction on local and regional level differed. Rather than focus on service improvement of the latter, the former almost exclusively addressed service delivery such as developing and understanding treatment plans, medication, etc. As one physician said: “If the patient is not onboard, you will get no compliance.” Some clinicians struggled to see coproduction in service improvement; a physician noted that collaboration among various public organizations was essential for the aging patient group, but could not see how involving patients could be relevant because it was an “organizational matter.”

Overall, the regional approach seemed to be to find a best practice or model of how to coproduce, but the respondents highlighted that coproduction had to differ depending on purpose. For instance, lead patients could sit and discuss with managers in a way other patients could not, and their good knowledge of the healthcare system enabled them to act as translators between staff and other patients. User councils relied more on democratic principles, one respondent argued, and could highlight specific issues for the patient group. Moreover, depending on level – local, regional, national – coproduction had to have different foci, ranging from interactions to regulations, but coherence was needed across the levels.

While members felt having just one patient representative in the process teams was insufficient, it had been difficult to attract patients. The teams wanted at least two patients represented in each team so that patients could discuss with their peers during meetings, like staff could. Patients also found it difficult to participate in long meetings. Also, having patients in the room for the whole meeting meant that certain topics, such as palliative care, were avoided so as to not worry patients. It was somewhat unclear what was expected of the patient: “To develop? To comment? To update? To challenge?” According to one respondent, “we should not be afraid to delimit coproduction to a specific issue or task, but I think a lot of staff is uncomfortable doing that.”

A common reason why patients decided to coproduce was to benefit the patient group: “One wants to use one’s experience to improve things for others.” Also, coproduction often seemed to benefit the participating patients in terms of meeting others, and gaining knowledge about treatment and the organization. Patients said they had gained a sense of empowerment from talking in front of other patients and staff. For others, telling their story had been a good way to process the illness and to move forward. Others wanted to “return the favor” by contributing to tax-financed healthcare, and contributing to the common good by doing their duty as citizens.

Because the professionals participated in meetings during paid hours, there was a feeling that patients should also be paid, although the fee administration should be dealt with by somebody not in the same team to avoid reinforcing the skewed power balance. One respondent said that if patients were not paid, “we can only include those able to participate on their spare time, or those being on sick-leave […] not those with chronic diseases who may work and need to take days off to participate.” However, one respondent raised the risk of creating a “gig economy,” meaning that the income would be essential for the patient and affect their behavior during coproduction: “Is it possible to be a demanding patient if one gets paid or do one risk not to get new gigs?” Another respondent argued that payment could affect what the patients said: “I think one rather quickly learns what kinds of stories healthcare wants to hear.”

Context of coproduction

This dimension includes two themes: What type of knowledge prevails in the organization and the risk that “soft issues” may clash.

Many perceived that “knowledge” in the knowledge-driven organization was synonymous with medical knowledge and organizing healthcare based on “body parts” or “diagnoses,” and that this had always been the case as physicians’ interests prevailed. Consequently, some respondents sarcastically labeled equality, coproduction, trust, interactions, etc. as “soft issues” – the term that management used to contrast with the prevailing “hard facts” of medical quality and economy.

One attention-getting strategy was to connect “soft issues” with “hard facts,” such as embedding equality aspects in medical quality indicators. Another respondent argued that equality could not be managed or easily incorporated into templates and by quantification, and instead needed to be reflected upon and discussed continuously: “If we don’t work actively with equality, we in a way work actively with inequality because these are issues that are not solved by themselves.” Although many of the professionals in the organization were used to search information in scientific articles, this had not been done to any greater extent concerning coproduction. One physician said: “We have other things to focus on […] more hands-on things.” Another respondent argued that focus was often on what could be measured and registered.

Equality as a term was mainly used as “sameness” with focus on reducing differences among hospitals without any rationale, geographical areas, etc. Equality as “doing things differently” for different groups depending on needs was rarely mentioned – essential for “things to become equal in the end.” Therefore, administrators had to ensure that coproduction not only heard those strong in resources and abilities, but also “those who choose not to tell or are unable to tell.”

Some respondents thought that equality as “sameness” could conflict with the concept of person-centeredness. It was argued that person-centeredness was a sign of the times in that “society, and thus healthcare, is fixated with individualization and we are fixated with individuals and their stories.” To address inequalities, “it is crucial to lift up the problem at the group level to visualize the problem as a structural one.” Some equality specialists argued that proponents of person-centeredness – and healthcare professionals overall – claimed that they did not see groups, but met everybody as unique individuals. This was seen as an over-belief in the opportunity to “throw away one’s preunderstanding.” Norms that everyone carries, often unconsciously, affected interactions with patients. Equality as “doing differently” was more aligned with person-centeredness and individualization: “If equality is seen as doing differently depending on situation or need, then it is similar to person-centeredness.”

Inclusion in coproduction

This dimension covers recruitment of coproducing laypeople, as well as reasons to coproduce and, specifically, to do so addressing equality.

The typical patients for one process team often had low education, but the representatives were well-educated and therefore did “represent a very small group.” The professionals in the teams were supposed to come from different professions, geographical areas, and levels of care, but ironically “one individual person was supposed to represent the patient group;” one respondent labeled this as “tokenism.”

Some had no problem with professionals in the teams recruiting the patient representative. The established relation could make the patient relaxed and willing to talk openly. However, most respondents described this “handpicked” patient as an “alibi” or “hostage.” One respondent said, “You get a patient involved that you have chosen yourself and who says the things you want them to say. You don’t need to change yourself as much, but you have gain legitimacy for what you do because your patient says so.”

Some felt that patients should choose their own representative: “There is a democratic aspect in it. We cannot tell the union to only involve those that we approve of.” A benefit of letting patient associations pick their candidate was that the representative reported back to the association, reaching numerous patients. However, many patients, especially younger ones, were not involved with an association that, to some, was made up of “organization people […] who like to talk and be seen.” There was a risk that associations would send a “star” – a “semi-professional” patient and a good talker but an atypical patient. Other types of suggested patient representations included a reference group for administrators to visit to discuss issues; this larger group would allow diversity and, by changing numerical representation between staff and patients, would probably allow the latter to speak more freely.

One respondent stated that it was difficult to attract people suffering from lifestyle-related illnesses (such as alcoholism and addiction) because of the stigma: “It is some kind of shame associated to it.” Others said that non-Swedish-speaking people were often excluded for practical reasons despite people knowing it was a group that was important to reach. Others said these people were not interested in participating in coproduction. Another respondent argued that more effort should be put into attracting those hardest to reach, who were often suffering the most: “We would get a lot of things in return if we succeeded in involving them better.”

A risk of involving “better-off” patients was that “healthcare only will improve for certain patients with resources.” Another risk with letting people take over some of the staff tasks was that public healthcare would abdicate its responsibility, implying that other patients “can manage this themselves.” Healthcare sometimes needed to select “capable” patients because coproduction involved talking in front of people or a camera. This chance of selecting “better-off” patients – while excluding patients who speak poor Swedish, have psychiatric problems or intellectual disabilities, etc. – increased with public events, when administrators wanted to “play safe” and not let the patient “make a fool of themselves” or to make the situation awkward. One administrator said: “When we involve patients – because it is rarely done – we want them to say all the right things.” Another respondent feared that the patient’s subordinated position would show too clearly. However, as a consequence: “We contribute to the subordination because of our own anxiety about not doing so.”

A common reason to coproduce with patients was to get the patient’s perspective, often on new things that staff had not considered before. Involving patients was unavoidable if one wanted to understand the problem: “First of all, it is the patient’s disease, illness, situation. It’s not ours.” Others argued that just being present was important, while others called it “a question of human rights.” Coproduction was also seen as a resource for improving things: “We work for them, and if things do not improve for them, they have not improved for anyone […] if we cannot focus to work on the right things it is a waste.”

Involving patients equitably was “first and foremost a matter of justice and regulated in a number of laws.” Many respondents argued that everybody should have access to healthcare services based on their needs, including possibilities to participate in healthcare development. Therefore, it was important to find appropriate representatives, including “voices that are often not heard.” Although equality was mentioned as a means of achieving something, equality as a goal in itself was more commonly mentioned: “The democratic perspective, or maybe justice perspective, must be the main reason to work with equality […] but it should also be mirrored in quality parameters addressing things like economy and medical results.” Another respondent said: “There is evidence that quality is improved through inclusion.” The group level was considered essential because that is where structural injustices showed and entailed that people on individual level had different prerequisites and needs and for different reasons. This level was important not only to identify problems, but also to address solutions – and an important complement to the predominant standardizations of things in healthcare, guidelines, etc.: “One way to do things does not work for all patients.”

Several respondents noted that within the disadvantaged population it was likely to be the well-spoken, talkative people who represent the wider group in coproduction: “That is often the case, that it is a sub-group with strong opinions within the group.” One respondent said that to ensure the representative represented the whole group, representatives of associations for disabled, LGBTQ, etc. needed to establish what was to be said in the councils. However, a potential consequence of creating a strong “group will” was that these group representatives could often have difficulties rising above the group’s particularity – disability, sexual orientation, etc. – and see common patterns for the disadvantaged overall.

Discussion

Based on the public administrators’ accounts above, this section theorizes coproduction based on modes, levels, and reasons; coproduction and equality; and equality in and of coproduction.

Coproduction: Modes, reasons, and levels

In , the empirical material is situated in the typology by Nabatchi et al. (Citation2017), who in turn added levels to the Four Cos Model of Bovaird and Loeffler (Citation2013).

Table 2. Modes and levels of coproduction.

At the individual level, input is provided by individual laypeople (Bovaird et al. Citation2016; Brudney and England Citation1983). This type of coproduction is particularly important because input is provided individually and because benefit is enjoyed by the coproducing individual (Alford Citation2002, Citation2009). Overall, the individual level was particularly emphasized by clinically active employees in the disease-specific process teams. An interactive form of coproduction (Osborne and Strokosch Citation2013) or coproduction through citizen voice (Loeffler Citation2021) was often essential for developing a treatment plan with the patient and getting them to exercise and so on to benefit their own health and well-being. Thus, the benefit of coproduction was to achieve individualization in treatment (Alford Citation2009) and the reason for coproducing was mainly an instrumental one, emphasizing coproduction as a means rather than a goal. One physician described all the modes of coproduction for his patient group, starting with “micro-commissioning” (Loeffler and Bovaird Citation2019) through personalization being achieved of prioritization of health needs, followed by developing a treatment plan together, which was carried out jointly in codelivery at the gym, and finally the joint assessment of the treatment plan and improved health status (or not).

At the group level, public administrators work “directly and simultaneously with a specific cluster or category of lay actors who share common characteristics or interests” (Nabatchi et al. (Citation2017, 770). Here, input is provided by a group for other members of that group to benefit. Other than patient groups, the empirical material shows that such a group could be based on a segregated area, age group, or disability. Patients in process teams, lead patients, or from patient associations could contribute with knowledge and experiences to coproduce through citizen voice (Loeffler Citation2021) in order to provide their points of views in jointly identifying, design, and assessing healthcare services. Through coproduction through action, they could also codeliver services together with healthcare professionals (e.g., patient education), to benefit members of the particular patient group rather than themselves (Bovaird and Loeffler Citation2009, Bovaird et al. Citation2016). Here too, the instrumental argument was mainly heard (Neshkova and Guo Citation2012; Vamstad Citation2012): to improve services as revealed by respondents’ vocabulary such as “efficiency” and “waste.” However, inclusion of the disadvantaged for reasons of equality (Vanleene et al. Citation2018) was mentioned as an important end in itself.

At the collective level, input is provided by a group, but the group is more diverse group (as “citizens”) than in group coproduction. This level is important because the benefit should be enjoyed by all, not just individuals (Brudney and England Citation1983; Rosentraub and Sharp Citation1981). Services are contributed to and enjoyed by citizens as members of a political or geographical community (Nabatchi et al. Citation2017). Again, arguments to coproduce were both instrumental (improving services and deliberation as a mean) and normative, as in contributing to the common good (Alford Citation2002, Citation2009; Nabatchi et al. Citation2017) and deliberation as a democratic ideal in itself (Michels Citation2011). This level was found less than the previous two levels in the empirical material, perhaps because some respondents considered citizen dialogs and the like to be “the politicians’ arena.” Moreover, collective forms require more effort, such as coordination (Brudney and England Citation1983), than individual coproduction (Fledderus et al. Citation2015). This may also be relevant concerning recruitment and may be a reason why some respondents argued it was difficult to attract more than just one patient representative. Another reason could be that laypeople seem to favor individual and less demanding forms of coproduction (Bovaird and Loeffler Citation2009; Bovaird et al. Citation2016). Involving their own patients solved the coproduction recruitment issue and also brought established trust and relationships (Bovaird Citation2007; Joshi and Moore Citation2004). Many respondents questioned the handpicked strategy, for other reasons.

In practice, benefits are likely to “spill over” to other levels (Nabatchi et al. Citation2017); group or collective levels may not only benefit group members or citizens as collective, but also the coproducing individual (gained knowledge, empowerment [Jo and Nabatchi Citation2019]). Similar to Nabatchi et al. (Citation2017) and Pestoff (Citation2014), I do not favor a particular level or modes of coproduction. Instead, all may be important for different purposes, as respondents expressed in the empirical material.

Coproduction and equality

This section expands the typology in by discussing the relevance of the respective modes for equality, which is important for policy purposes (Bovaird et al. Citation2016), as well as recognizing the risk and possibilities of certain issues important to public administrations in practice.

Cocommissioning (Bovaird and Loeffler Citation2013) is relevant in terms of equality at all three levels because of the focus on prioritization. At the individual level, individualization in coproduction activities has been highlighted as particularly important (Alford Citation2009). In a healthcare context, this entails personalization through joint prioritizations of the patient’s specific health needs, not based on unjustified differences based on sex, ethnicity, etc. (Olsson Citation2016). The potential to reveal such structural barriers is even greater for the group level of cocommissioning, offering opportunities to deliberate based on a relational approach on basis of social group positioning (Young Citation2000, Citation2006) and to prioritize issues of pressing concern to the disadvantaged. Specifically, it was mentioned in the interviews that patient associations in segregated areas with many immigrants may help prioritize areas in need of improvement in the local context. Finally, the collective level is essential for equality in cocommissioning, not least cause a large number of citizens in itself may balance power asymmetries in relation to public employees, as mentioned in the interviews, but also because this broad approach may be required to address unfair distribution of public services and resources and to prioritize what needs to be delivered, what desirable outcomes need to be addressed, and groups in society that are particularly important to target (Bovaird and Loeffler Citation2013; Loeffler Citation2021).

Codesign is also important for equality. At the individual level it is essential to develop treatment plans relevant to the individual, regardless of sex, ethnicity and other factors. In the interviews, many clinically active employees said that this was achieved by working in a person- or patient-centered manner. At the group level, mapping a typical journey for the disadvantaged (including barriers and enablers, as mentioned in the interviews) through the healthcare process offered possibilities to (re)design processes and make them more relevant for those who were often in the greatest need (Jakobsen Citation2013). Despite being absent in the empirical material, at the collective level too it would be possible for citizens to (re)design services together with administrators for the same purpose. At individual level, codelivery is important to enable persons regardless background to realize their treatment plans – however, a physician mentioned that the stigma of a lifestyle-related illness posed a barrier for some patients to exercise in public, such as training at a gym (Thomsen et al. Citation2020). At the group level, codelivery may occur as the disadvantaged may educate peers together with healthcare staff at associations or public places, as mentioned in the interviews. The collective level is missing in the empirical material for codelivery. Coassessment in terms of equality for the individual and group is mentioned in terms of improved health (or not) for the individual or patient group, with the potential to identify differences at the individual or group level that are unfair. Similarly, surveys to the population at the collective level may identify areas or groups to prioritize in the cocommissioning mode.

Addressing the issue of distribution of public services and discussions of prioritizations, cocommissioning is essential for equality. In the empirical material, some of the respondents mentioned prioritizing those in the greatest need. Such statements are aligned with equality of opportunity, in which differences in needs are based on health status (regardless of whether they are considered primary goods (Rawls Citation1971) or basic capabilities (Sen Citation2005) and constitute legitime inequalities. Following this logic, those worst off should be prioritized use and access to healthcare services (Fleurbaey and Schokkaert Citation2011), similar to the solidarity principle in Swedish legislation (SOSFS Citation2005; SOU Citation1995). Indeed, managing to address the disadvantaged would be an important gain for everyone, as one respondent argued. At the same time, many respondents thought that in cases where needs or health status are the same, equal treatment should be offered, as in equality of use (Le Grand Citation1982).

Moreover, the illegitimate sources of inequality of equality of opportunity (Fleurbaey and Schokkaert Citation2011) concerns differences in access or use due to socioeconomic status, sex, ethnicity, or other factors, and have been highlighted in the empirical material as important to address. In some cases, they are de facto addressed in various quality improvement projects, such as developing tools to counteract unwanted gender bias in healthcare. Empirically, it may not be easy to draw the line between legitimate and illegitimate sources of inequality. For instance, there are various “bad luck” scenarios (Phillips Citation2004) that are beyond the control of individuals. Moreover, not developing lifestyle-related illness is, to a certain extent, within individuals’ control (eating healthily, exercising, not smoking, etc.), but should this fact disqualify them from being prioritized in terms of use and access to healthcare services due to their health status? As witnessed by the physician, the stigma of some diseases may cause inequalities in use and access to healthcare services, in which social context prevents the individual from visiting gyms and so forth (Eriksson Citation2019).

During the interviews, many of the respondents mentioned illegitimate sources of inequalities (Fleurbaey and Schokkaert Citation2011) in healthcare in the local context, and some gave account to the research in the field. Against this background, many argued for the importance of having the disadvantaged represented in various organizations (Fung Citation2003), as well as having the opportunity to make their voices heard in the public discourse (Post Citation2006), addressing equality of representation and equality of influence, respectively. Both these dimensions of equality are important in order to include the disadvantaged in coproduction – and, in so doing, improve services for their peers in the greatest need (Jakobsen Citation2013) and thus contribute to equality of outcome (Le Grand Citation1982), or health in a healthcare context. This point will be addressed in the next subsection.

Coproduction and inclusion

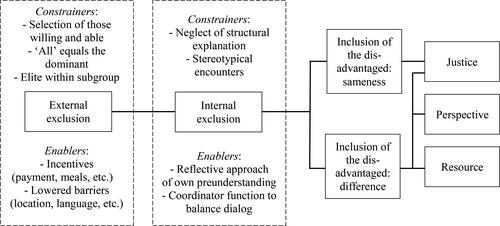

The equality aspect is particularly relevant in the context of this article: public healthcare. Poor health is recognized as being closely associated with inequalities (WHO Citation2008; Wilkinson and Pickett Citation2010), which are consequences of exclusion and marginalization from decision-making (Therborn Citation2014); that is, a failure to fulfill democratic promises of equal opportunities (Young Citation2000). To reduce inequalities, it is essential to include the disadvantaged in decision-making (Marmot Citation2015) and to address the causes of and solutions to structural inequalities (Young Citation2000). The World Health Organization’s (Citation2008) report entitled Closing the Gap in a Generation and the United Nation’s (Citation2019) report entitled Global Sustainable Development Report emphasize the involvement of people – particularly the disadvantaged – in addressing issues important for them as a strategy to reduce inequalities. I believe coproduction can play an important role here, both as an input (equality in) and a consequence of (equality of) coproduction. This observation was made back in the 1980s (Brudney and England Citation1983; Rosentraub and Sharp Citation1981), but little attention has been given to coproduction with regard to disadvantaged groups (Jakobsen Citation2013; Jakobsen and Andersen Citation2013). offers a way to visualize how equality can be understood within coproduction theory by incorporating theories addressing the inclusion of the disadvantaged.

The first box, external exclusion (Young Citation2000), addresses the important phase of inclusion in the coproduction activity itself, in user councils, process teams, etc. Here, disadvantaged groups may be excluded from being invited in the first place (Brandsen and Honingh Citation2016). In the empirical material, non-Swedish-speakers, the disabled, etc. were excluded in some types of coproduction. The handpicked patient representative of the process teams was described as better-educated and well-read about the disease, suggesting public administrators may be likely to (unconsciously) pick someone with backgrounds similar to theirs to coproduce with (Mifune, Hashimoto, and Yamagishi Citation2010; Riccucci, Van Ryzin, and Li Citation2016; Williams et al. Citation2016). Thus, it is mainly those who are willing and able who will be invited to participate (Jakobsen Citation2013). There is also a risk of recruiting better-off citizens who do not mirror the group. Despite awareness of this bias, the typical justification in the interviews is that including atypical patients is better than nothing because it is likely to narrow the professional–patient gap. However, involving better-off patients in coproduction may risk increasing the gap between advantaged and the disadvantaged (Brudney and England Citation1983; Rosentraub and Sharp Citation1981). Therefore, other recruitment strategies may be needed, such as random selection to involve laypeople (Fung Citation2003; Nabatchi Citation2012), although this was not mentioned by the respondents. Inviting “everyone” was exemplified by citizen dialogs in the interviews, but again it may mainly be dominant groups that are better off participating (Rosentraub and Sharpe Citation1981; Van Ryzin et al. Citation2017; Williams et al. Citation2016). A risk for group coproduction is that an “elite” within the disadvantaged are recruited, resulting in skewed representation (Olsson and Lau Citation2015).

Various incentives found in the literature (Jakobsen and Andersen Citation2013) are also found in the empirical material. For instance, inclusion of the disadvantaged can be promoted by payment for their participation, offering meals or covering transportation costs (Fung Citation2003; Nabatchi Citation2012), or reducing barriers to participate for groups known not to do so (Brudney and England Citation1983; Williams et al. Citation2016), by adapting location and language for coproduction.

Exclusion can also be manifested during interactions in which the disadvantaged voices may not be listened to – internal exclusion (Young Citation2000). Despite mirroring society in representation, social structures are mirrored when people deliberate in collectives: “When Americans assemble in juries, they do not leave behind the status, power, and privileges that they hold in the outside world” (Sanders Citation1997, 364). Thus, if structural explanations are ignored, power structures, stereotypes and so forth will remain, which may be particularly relevant in individual coproduction occurring during interactions (Olsson Citation2016). As mentioned, in attempts to give everyone the same opportunities, the dominant are likely to take over (Kymlicka Citation1995) or disadvantaged voices may be ignored or incorporated into the dominant identity (Taylor Citation1995). Similarly, focusing on the common good – as a benefit enjoyed by all – is also likely to benefit dominant groups (Young Citation2000). Therefore, even if the disadvantaged are involved in coproduction, both group and collective coproduction may increase inequalities during participation (Brudney and England Citation1983; Rosentraub and Sharpe 1981; Warren et al. Citation1984).

In group and collective coproduction, a formalized coordinator function may be a way to let everybody speak (Brudney and England Citation1983). To avoid addressing people stereotypically, it may be important to nurture a reflexive approach among employees to question their own norms and prejudices that they may be unaware of (Olsson Citation2016). The empirical material shows strong beliefs in treating each patient as unique and in not treating laypeople stereotypically. A contributing factor could be increased individualization, such as person-centeredness.

The external (having a place) and internal (having a say) reasons for including the disadvantaged may differ. Viewing equality as sameness means that the disadvantaged are to be represented on equal terms as everybody else. Thus, the focus is not on their unique position or particularity (Martin Citation2008), but on the ideas they raise (“politics of ideas”) (Phillips Citation2000). However, as noted, this entails a uniformity blind of differences (Taylor Citation1995) and privileged groups’ experiences will appear as universal and disadvantaged groups experiences may not be seen (Young Citation1990).

However, the disadvantaged may also be included for their particularity (Martin Citation2008). Their presence in coproduction is more in line with who they are (“politics of differences”) (Phillips Citation2000) as equality is about difference rather than sameness. The inclusion of the disadvantaged could be argued for based on normative ideals such as justice, as well as arguments based on perspectives and resources. Issues of pressing concern to marginalized groups would be unlikely to be brought to agenda unless the issue was raised by individuals from that particular group (Smith Citation1998). Knowledge of languages, and of experiences of healthcare services in other countries, have been beneficial resources in designing information and activities and in delivering them in coproduction (Bullock and McGraw Citation2006). Thus, for both arguments, including the disadvantaged in coproduction is a means of achieving some kind of change, such as better services, by incorporating unique perspectives and resources. As resources, it is important to include cultural background, language skills, etc. when improving services and reaching people with the same background, who often refrain from visiting healthcare facilities. Thus, the coproducer’s background is seen as an asset for the organization.

Conclusion

This article has contributed to citizens’ inclusion in coproduction from the perspectives of public administrators. I found that reasons for including citizens in coproduction are both instrumental, such as improved efficiency, and normative, such as democracy. Building on existing research of modes and levels of coproduction, individual, groups, and collectives were all found to be important for coproduction across the policy cycle of cocommissioning, codesign, codelivery, and coassessment. From an equality perspective, cocommissioning at the collective level is essential for addressing the overall issue of distribution of public services and prioritizations of targeting those in the greatest need. Priority based on need accepts legitimate sources of inequalities that entail different use and access to healthcare services because of different health status.

However, illegitimate sources of inequality based on non-rational differences in access and use due to socioeconomic background, sex, ethnicity and so on may be counteracted by involving the disadvantaged in coproduction in the various phases of coproduction. Not least, members of a certain group may co-design services with public employees and, in so doing, contribute to equality in outcome, by improving health for their peers.

Inclusion of the disadvantaged in coproduction is important for democratic reasons, as it places those who are often worst off at the center of the decision-making process. For adequate participation, the disadvantaged need to thread the needle of external (being invited) and internal (having an equal say) inclusion. The disadvantaged may be included for various reasons depending on whether equality is understood as sameness or differences. Thus, the disadvantaged may be involved for reasons of justice, perspective, or as a resource. Accordingly, coproduction – and the inclusion of the disadvantaged in particular – is not an either/or issue between normative and instrumental reason: both need to be addressed.

The paper contributes to coproduction theory by applying empirical material from public administrators’ perspective, and highlights equality aspects by incorporating theories from political philosophy and democratic theory. More specifically, modes and levels of coproduction may vary in relevance depending on what one seeks to equalize. Naturally, these aspects are also important to policy and practice, as it has been shown that addressing equality through cocommissioning at the collective level, codesign at the group level, or codelivery at the individual level require different strategies and practices.

This article has focused on administrators’ experiences and perceptions of coproduction. Future research should highlight the citizen perspective and/or the interface between the two co-parties.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank all involved actors in the study and the anonymous reviewers for valuable comments on earlier versions of this article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Erik Eriksson

Erik Eriksson is a Researcher at Chalmers University of Technology, Sweden. He has a PhD in management and economics and a master’s degree focused on political science in public administration. His research focuses on co-production, collaborative governance, and value creation.

References

- Alford, J. 2002. “Why do Public-sector Clients Coproduce? Toward a Contingency Theory.” Administration & Society 34(1):32–56. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0095399702034001004.

- Alford, J. 2009. “Public Value from Co-Production by Clients: What Induces Clients to Co-Produce.” Public Sector 32(4):11–2.

- Andersen, L. B., S. Boye, and R. Laursen. 2018. “How to Increase Citizen Coproduction: Replication and Extension of Existing Research.” International Public Management Journal 21(1):1–21. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/10967494.2017.1329761.

- Bovaird, T. 2007. “Beyond Engagement and Participation: User and Community Coproduction of Public Services.” Public Administration Review 67(5):846–60. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2007.00773.x.

- Bovaird, T., and E. Loeffler. 2009. “User and Community Co-Production of Public Services and Public Policies through Collaborative Decision-making: The Role of Emerging Technologies.” 5STAD – EGPA/ASPA Transatlantic Dialogue, the future of governance in Europe and the U.S.

- Bovaird, T., and E. Loeffler. 2012. “From Engagement to Co-production: The Contribution of Users and Communities to Outcomes and Public Value.” VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 23(4):1119–38. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-012-9309-6.

- Bovaird, T., and E. Loeffler. 2013. “We’re All in this Together: Harnessing User and Community Co-production of Public Outcomes.” Pp. 1–13 in Making Sense of the Future: Do we Need a New Model of Public Services?, edited by C. Staite. Birmingham, UK: University of Birmingham.

- Bovaird, T., G. Stoker, T. Jones, E. Loeffler, and M. Pinilla Roncancio. 2016. “Activating Collective Co-Production of Public Services: Influencing Citizens to Participate in Complex Governance Mechanisms in the UK.” International Review of Administrative Sciences 82(1):47–68. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0020852314566009.

- Brandsen, T., and M. Honingh. 2016. “Distinguishing Different Types of Coproduction: A Conceptual Analysis Based on the Classical Definitions.” Public Administration Review 76(3):427–35. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12465.

- Brandsen, T., and M. Honingh. 2018. “Definitions of Co-Production and Co-Creation.” Pp. 9–17 in Co-Production and Co-Creation. Engaging Citizens in Public Services, edited by T. Brandsen, T. Steen, and B. Verschuere. Milton Parks: Routledge.

- Braveman, P., and S. Gruskin. 2003. “Defining Equity in Health.” Journal of epidemiology and community health 57(4):254–8. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.57.4.254.

- Brudney, J., and R. England. 1983. “Toward a Definition of the Coproduction Concept.” Public Administration Review 43(1):59–65. doi: https://doi.org/10.2307/975300.

- Bullock, K., and S. McGraw. 2006. “A Community Capacity-Enhancement Approach to Breast and Cervical Cancer Screening among Older Women of Color.” Health & Social Work 31(1):16–25. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/hsw/31.1.16.