Abstract

The study contributes to our knowledge of leadership in public organizations on three specific areas. First, it is a unique exploration of whether managers in publicly owned organizations perceive less job autonomy than managers in privately owned and hybrid organizations. Hybrid organizations are defined in two categories: shareholder companies with both public and private owners, and public companies (organizations selling their products or services, but publicly owned). Second, the study investigates possible mechanisms - more specifically formalization and professionalization - through which organizational ownership (public, private, and hybrid) is assumed to affect managerial autonomy. Finally, the study incorporates important confounding variables – first and foremost size (number of employees), task (technology), and hierarchical level - missing from many other comparisons of public and private organizations. The main findings support the notion that perceived managerial autonomy in publicly owned organizations is lower than in both hybrid and private organization. These differences are not, however, explained by differences in formalization and professionalization.

Introduction

One important idea in public management thinking over the last decades has been to let “the managers manage,” implicitly evoking a picture of managers in public organizations being less free to exert leadership than their private sector counterparts (Aucoin Citation1990; Bezes and Jeannot Citation2018; Kettl Citation1997, Citation2002). Managerial autonomy was regarded as a main element in increasing the innovation, flexibility, and the general performance of public sector organizations (Wynen et al. Citation2014), becoming an important argument driving a “[…] shift from a centralized and consolidated public sector to a decentralized, structurally devolved and “autonomizing” public sector […]” (Verhoest et al. Citation2010, 3). Granting managers more institutional autonomy was regarded as an important measure to increase and secure internal managerial autonomy, so that managers more freely could prioritize between tasks and choose how to perform them (Osborne and Gaebler Citation1992). This was mainly obtained was by creating organizational forms shielding mangers from direct political intervention, in the most radical form through privatizations, i.e., moving public tasks and responsibilities from public ownership, budget financing and direct political control to private ownership, market financing and more indirect political control through generic regulation (Megginson and Netter Citation2001).

Less radical, and thus more common, was an extensive use of delegation within the public sector through the creation of “quasi-autonomous independent agencies” (Flinders Citation2009), often termed “agencification” (Overman and van Thiel Citation2016). Such agencies are still units embedded in the public sector, objects to public law, and financed through public budgets, but are often granted institutional autonomy through structures granting own boards and separate statutes (Verhoest et al. Citation2012). Between the “pure” forms of market and public sector, a wide variety of institutional forms exist, partly aimed at providing wider frames for managerial autonomy. One such form could be termed “corporatization” (Andrews et al. Citation2020, 483), designing organizational forms to be more ‘business-like’ with separate legal status, own boards, and commercial responsibility. Corporatization may further be divided into several subtypes. One such subtype is publicly owned enterprise, describing an institutional form where the public sector—both state and local government—hold full ownership, either through direct ownership regulated by special laws or through stock companies where the public sector controls 100% of the shares (Krause and Van Thiel Citation2019). Another form is based on cooperation between the public and private sector though shared ownership, usually through the legal form of a stock company. Both types of corporatization can be termed as “hybrid types” as they include different institutional logics—both market and state—within the same institutional framework (Johanson and Vakkuri Citation2018).

Several studies have looked into the phenomenon of autonomy—including both the phenomenon itself, as well as its causes and consequences—of both agencies (Bilodeau, Laurin, and Vining Citation2006; Egeberg and Trondal Citation2009; Overman and van Thiel Citation2016; Verhoest et al. Citation2010; Verhoest et al. Citation2012) and hybrid or corporatized organizations (Rhys Andrews et al. Citation2020; Bel et al. Citation2021; Grossi and Reichard Citation2008; Lindlbauer, Winter, and Schreyogg Citation2016; Voorn, Borst, and Blom Citation2020). Still there are few studies at the micro-level, i.e., of internal managerial autonomy, in agencies and semipublic or public corporations (for notable exceptions see Krause and Van Thiel Citation2019; Verhoest et al. Citation2010; Voorn, Borst, and Blom Citation2020), and none of these provide direct comparisons of managerial autonomy in private, public and hybrid contexts.

This caveat is somewhat surprising as more general studies comparing public and private organizations mostly seem to conclude that public organizations represent a context imposing stronger constraints on managers than private organizations (Andrews, Boyne, and Walker Citation2011; Andrews and Esteve Citation2015; Boyne Citation2002; Pollitt Citation2013; Rainey Citation1989, Citation2014). These studies conclude, although not always supported by solid empirical evidence, that public organizations are more formalized and bureaucratic, more centralized, have more ambiguous goals and are more professionalized. At least three of these contextual elements are usually regarded as representing barriers to leadership, either in the sense that they neutralize, or function as a substitute for, leadership (Jermier and Kerr Citation1997). Even if these comparative studies conclude that the room for leadership and managerial discretion is more limited in public than in private organizations, no studies have investigated this directly.

Moreover, corporatization is one important key to understand the blurring of the distinction between the public and the private. While some elements like increased regulation of markets and businesses may have made private organizations more exposed to political authority and thus becoming more “public,” corporatization exposes public organizations stronger to the economic authority of the market by introducing private sector mechanisms like performance measures, pay-per-produced unit, and competition (Bosetzky Citation1980; Christensen and Laegreid Citation2011; Desmarais and de Chatillon Citation2010; Emery and Giauque Citation2005; Hall, Miller, and Millar Citation2016; Morales, Wittek, and Heyse Citation2013; Pollitt Citation2001; Pollitt and Bouckaert Citation2011; Poole, Mansfield, and Gould‐Williams Citation2006). Corporatization has resulted in hybrid organizations that combine public sector characteristics like public ownership with private sector characteristics like competition and market-based income (Bozeman Citation2013; Emery and Giauque Citation2005). As noted in the first paragraph, one of the main arguments behind the creation of such hybrid organizational forms has been to increase managerial autonomy. Still, empirical studies comparing managerial autonomy in hybrid organizations, with managerial autonomy in private and public organizations simply do not exist. Thus, we pose the following research question: Is perceived managerial autonomy greater in private and hybrid organizations than in public organizations?

The study contributes to our knowledge of management in public organizations on three specific areas. First, it is a unique test of whether managers in public organizations themselves perceive less autonomy than their colleagues in private and hybrid organizations. By doing so, we follow the advice to study “the perceptual nature of autonomy” (Maggetti and Verhoest Citation2014, 245). Using the classic concept of job autonomy (Hackman and Oldham Citation1980), we also extend the study of autonomy to how individual managers perceive their possibilities to prioritize between tasks and ways of doing them. Second, the study also scrutinizes possible mechanisms through which organizational form is assumed to affect managerial autonomy. More specifically it focuses on how organizational characteristics—perceived formalization and professionalization—that are assumed to vary significantly between public, hybrid, and private organizations, constrain managerial autonomy (Andrews, Boyne, and Walker Citation2011; Rainey Citation1989, Citation2014). Finally, the study, representing a national probability sample of public, private and hybrid organizations, incorporates important confounding variables—mainly size (number of employees) and task (technology)—missing from many other comparisons of public and private organizations, thus lowering the risk of reporting spurious relationships (Boyne Citation2002; Rainey Citation2011).

Managerial autonomy—the impact of institutional context

Focusing on managerial autonomy implies a focus on the freedom an individual manager within an organizational and institutional context has to make choices without conferring with others (Bezes and Jeannot Citation2018). It is thus different from organizational or institutional autonomy, defined as “[…] the degree to which sets of specialized corporate actors are structurally and symbolically independent of other sets of corporate actors” (Abrutyn Citation2009, 461; Olsen Citation2009). Institutional autonomy is, however, linked to individual managerial autonomy, as the institutional context will constitute what room a manager has for discretionary decisions.

Managerial autonomy can again be split into several subtypes. Verhoest et al. (Citation2010) distinguish between financial, Human Resource Management (HRM), and policy autonomy. Krause and Van Thiel (Citation2019) measure four: HRM, business, pricing and strategic. Hansen and Villadsen (Citation2010) distinguish between job autonomy, organizational autonomy, and decision autonomy. This study focuses on perceived job autonomy, more specifically managers’ perceived freedom to prioritize between tasks and decide on how and when they should be performed, and thus the degree to which a manager must confer with others in making decisions (Nutt and Backoff Citation1993).

Institutional and organizational contexts will always represent constraints on managers, even at the top management level (Yukl Citation2013, chapter 2). The more constraints imposed on the manager in her or his position, the less autonomy and consequently less job autonomy at the individual level. It seems to be a general assumption that the context of a public organization provides less room for managerial discretion than that of a private organization (Meier and O'Toole Citation2011; Nutt Citation2000; Rainey Citation2014; Scott and Falcone Citation1998; Williamson Citation2011). Managers who have worked in both private and public organizations tend to report stronger constraints on their behavior in the public sector (see Rainey Citation2014, 364). In their study of public and private managers, Poole, Mansfield, and Gould‐Williams (Citation2006, 1065) find that managers in public organizations report less “scope for managerial action and initiative” than their colleagues in the private sector. However, findings are not clear, and a study of Danish managers (Hansen and Villadsen Citation2010) reports a contrasting finding where managers in public organizations in fact report higher job autonomy than private sector managers.

All studies referred to above are based on a dichotomous distinction between the public and the private sector, ignoring the fact that the two sectors encompass a wide variety of organizational forms (Andersen Citation2010; Desmarais and de Chatillon Citation2010). Some of these forms can be labeled as “hybrids,” as they combine two or more institutional logics, or “[…] taken-for-granted social prescriptions that represent shared understandings of what constitutes legitimate goals and how they may be pursued” (Battilana and Dorado Citation2010, 1420). Examples may include combinations of nonprofit with for-profit organizations (Doherty, Haugh, and Lyon Citation2014), public organizations and voluntary sector (Edelenbos, Van Buuren, and Klijn Citation2013), or—as the focus in this study—a mix of public and private sector logics (Bruton, Peng, Ahlstrom, Stan, and Xu Citation2015).

“Corporatization” represents a hybridization as it combines the logics of public sector ownership with the market logic of the private sector (Andrews et al. Citation2020). One common form is public company, an organization that is fully owned by a public institution (either state, regional, local, or intermunicipal), but still strongly exposed to market mechanisms as most or all the organization’s income is expected to be generated through sales of goods and/or services. Such companies are mostly regulated by specific laws. Another common form is shared ownership, organizations regarded as private (for instance banks or producers of energy or transport) and being subjects to private law (joint stock company), but partly owned by public institutions. Representatives of public institutions are thus represented in the governing organs (i.e., boards as most of them are shareholder companies), reflecting their ownership share, while income is generated through the market. These are organizations that must balance and combine two logics: on the one hand as a provider of a central public service and thus of public value, while on the other hand complying with the market logic of sales, competition, and income generation.

One main reason for corporatization is to create an organizational context that creates space for more managerial autonomy (Andrews et al. Citation2020), as the focus is set less on the daily activities of the manager, but rather on the results and outcomes (Wynen et al. Citation2014). Still, corporatized companies will be subjects to political control, so one may reasonably assume that managerial job autonomy will be somewhat lower in these types of organizations compared to purely privately owned companies. This leads to the first hypothesis:

H1: Compared to private and corporatized organizations, perceived managerial job autonomy will be lower in public organizations.

Formalization

The probably most assumed structural characteristic of public organizations constraining managerial autonomy is the number of rules regulating work in the organization, somewhat interchangeably called bureaucratization or formalization (Boyne Citation2002; Feeney and Rainey Citation2010; Holdaway et al. Citation1975; Rainey Citation2014; Rainey and Chun Citation2005). The basic element of formalization is “[…] how many written rules are in existence” (Kaufmann and Feeney Citation2012, 1197), or—as Mintzberg (Citation1979) coins it—“standardization of behavior.” Indeed, the whole idea of formal rules is to limit discretion to produce as predictable processes, outputs, and outcomes as possible (Reimann Citation1973; Whitford Citation2002). Formalization is a structural element that will limit a manager’s job autonomy. In the leadership literature, formalization has even been labeled a “substitute for leadership” as it tends “[…] to negate the leader’s ability to either improve or impair subordinate satisfaction and performance” (Kerr and Jermier Citation1978, 377).

Although formalization is a phenomenon occurring in all organizations (Meyer Citation1987), there are several arguments for a higher degree of formalization of public organizations. Order, stability, and predictability are basic requirements for a legitimate “rule of law” (Terry Citation2003; March and Olsen Citation1989). One of Max Weber’s main arguments for bureaucracy was that it was important to limit the discretionary power of bureaucrats in the sense that all decisions should be grounded in a set of written, formal rules. Furthermore, it is essential to a democracy that elected representative can be held accountable to the public. As many of the decisions made within the public sector concern areas and tasks where it is difficult to establish clear means-ends-connections, output accountability is complicated. Thus, process and input accountability must be vied more attention. On the one hand, this will put stronger requirements on openness, and procedures for documenting how tasks have been performed. All this will require elaborate sets of rules for guaranteeing openness and documentation. On the input side, stronger demands are set on how personnel is selected and promoted than is the case of business organizations (Chen and Rainey Citation2014; Zibarras and Woods Citation2010). Thus, one should expect public organizations to be more formalized than private ones (Bozeman, Reed, and Scott Citation1992; Chen Citation2012; Rainey Citation2014).

A few large surveys (i.e., Marsden, Cook, and Kalleberg Citation1994) tend to support the notion that public organizations are more formalized than private organizations. Formalization may thus function as a mediator between organizational form—public, private, hybrid—and managerial job autonomy, leading us to formulate the following three hypotheses:

H2a: Compared to private and corporatized organizations, formalization will be stronger in pure public organizations.

H2b: The stronger the formalization, the lower the managerial job autonomy.

H2c: Formalization will mediate a negative indirect effect from pure public organization to managerial job autonomy.

Professionalization

A second characteristic distinguishing public organizations from private organizations is to what degree employees are professionalized. A professional is here defined as a person with a specific skill acquired through higher education and formal training, qualifying the person to enter a specific position (Abbott Citation1988; Ritzer Citation1975). In their daily work, professionals will evaluate their work according to standards elaborated by the profession rather than the organization. Their ability to analyze and diagnose complex problems, and to make inferences and suggest practical action (treatment) give them control over day-to-day decision making, and consequently over defining the quality of work (Dickinson et al. Citation2017).

Professionalization of public organizations is tightly linked to the tasks defined to the public sphere. Some goods—collective goods—will not necessarily be produced in a market. Examples are general courts, military defence, police, and administration of common resources like nature and water. Most of these tasks are regulatory tasks, a fact mirrored in early professionalization being intimately linked to the legal profession (Ritzer Citation1975). Less obvious than collective goods, is the phenomenon of merit goods, or goods that the market will produce, but where other considerations—usually distributive effects—result in situating the task in the public sector. Examples of this could be general schooling and health services. These tasks are highly professionalized as they are staffed by highly educated teachers, doctors or nurses, all prominent examples of modern-day public service professions (DiPrete Citation1987; Larson Citation1977).

Professionalization is tightly linked to autonomy, and thus to a possible conflict between employees claiming professional freedom and managers representing hierarchical control (Freidson Citation1970; Leicht and Fennell Citation1997). While managers are responsible for the overall results and use of resources in the organization or the organizational unit, professionals will more likely devote their loyalty to professional standards and the well-being of clients. Leading professionals is thus a challenging task (Mintzberg Citation1979), as they are difficult to monitor and control due to the complexity of their work, and the professionals’ superior knowledge of how to perform it. Most studies of professional organizations end up with the conclusion that professionalization of employees limits the discretionary autonomy of formal, hierarchical leaders (Abbott Citation1988; Currie and Procter Citation2005; de Bruijn Citation2011; Empson Citation2017; Evans Citation2011; Mintzberg Citation1998; Raelin Citation1989). Kerr and Jermier (Citation1978) file professionalization as a substitute for leadership that will neutralize most leader activities vis-à-vis their professional employees (see also Podsakoff et al. Citation1993; Yu-Chi Citation2010). As it is assumed that public organization will be associated with higher professionalization, one may also expect stronger limitation on managerial autonomy in public organizations. Even though the argument above is rather crude, and managerial loss of job autonomy through professionalized staff will surely depend on the professional level of the manager (Hwang and Powell Citation2009) and on the type of profession, we propose the following three hypotheses:

H3a: Compared to private and corporatized organizations, professionalization will be stronger in pure public organizations.

H3b: The stronger the professionalization among employees, the lower the managerial job autonomy.

H3c: Professionalization will mediate a negative indirect effect from pure public organization to managerial job autonomy.

Confounders—size, task, and hierarchical level

Several factors other than sector may be correlated to both managerial autonomy and organizational form, increasing the danger of establishing spurious relationships (Andrews, Boyne, and Walker Citation2011). In most countries, public organizations are assigned specific tasks, either because of market failures or political decisions (merit goods) (Pesch Citation2008), making it difficult to isolate the effect of organizational form. For instance, in Norway and many other countries, basic schooling, health services and social services are carried out almost completely by public organizations. Thus, the visible differences in organizational form—i.e., funding and ownership—may only reflect differences in tasks and their technology. A classic argument from contingency theory (Donaldson Citation2001) is that structure will be formed by task in the sense that task uncertainty and complexity will correlate with both formalization and professionalization. Thus, in this study, we open for the possibility that organizational form as well as formalization and professionalization will vary systematically with the task of the organization.

Second, there is the challenge of organizational size. In his much-cited review of differences between public and private organizations, Boyne (Citation2002, 109) airs the worry that “[…] doubts remain about the relative bureaucratization of the two sectors. Furthermore, a shadow is cast over much of the evidence by the failure to include statistical controls for organizational size. If public agencies tend to be larger than private firms, then the correlations between organizational form and bureaucracy may be spurious.” As noted by Boyne, several empirical studies support the notion that size—defined as number of employees in the organization—is strongly and positively correlated with formalization (Donaldson Citation2001; Donaldson and Luo Citation2014; Rutherford Citation2016).

Third, as there are differences in size between organizations, one should also expect differences in hierarchical differentiation within each organization. As it is highly likely that job autonomy will differ between hierarchical levels (Psychogios, Wilkinson, and Szamosi Citation2009), we also control for managerial level.

The empirical study

A survey was distributed on behalf of the Norwegian School of Economics by the market research firm Synovate (now Ipsos) to 4108 leaders in Norwegian organizations with more than ten employees, representing 1716 different organizations during the spring of 2013. Starting with a population list of all registered organizations in Norway, the sample was stratified proportionally according to business and size. All selected organizations were contacted by telephone, and the questionnaire was distributed in paper form to all persons defined as managers by the organization itself (usually all those with personnel responsibility). No incentives were provided. Two follow ups were conducted, the first by mail, the second by phone. A total of 2910 responded (response rate 71%). Managers of trade associations, voluntary organizations and foundations were discarded from this analysis, leaving a total of 2488 respondents. As this is a study comparing perceived individual managerial autonomy between sectorial contexts, four broad types of organizations were defined: (1) privately owned businesses, (2) shared ownership (both private and public sector owners), (3) public companies, and (4) publicly owned and financed organizations. displays more detailed information about these organizational forms.

Table 1. Description of organizational forms and response rates.

The representation of organizations from the four types is very close to the distribution in the Norwegian population of registered organizations. There are no large biases in the response rates across hierarchical levels (top managers = 72, other managers = 70) or gender. There is some variation in response rates between businesses (ranging from 63 in building and construction to 86 in education), but still not to the extent that any types of businesses are missing from the analysis. The coverage error, sampling error and nonresponse error seem to be small, justifying a conclusion that this is a highly representative sample of Norwegian managers. 47% of the organizations are represented by one top manager only, 15% by two managers, another 12% by 3–4 managers, and the rest (26%) by more than 5 managers. The sample thus consists partly of multilevel data with individual managers embedded in organizations. It is a weakness that almost half of the organizations in the study are represented by only one respondent, so it was decided to run two analyses: one on the full sample, and one of the sub-sample of organization represented by two or more managers (Wagner, Rau, and Lindemann Citation2010).

This study is based on measures of the perceived job autonomy of a leader (Boon and Wynen Citation2017). In general, job autonomy can be defined as independence “[…] in formulating tasks or in carrying through courses of actions.” (Dill Citation1958, 411). This definition is close to a highly validated measurement instrument on job autonomy elaborated by Hackman and Oldham (Citation1980), used in the Danish study by Hansen and Villadsen (Citation2010). This is a scale consisting of three items: (1) “In my job I can choose which tasks to conduct,” (2) “In my job I can choose the way to do tasks independently of others,” and (3) “In my job I can act independently of others.”

Five items were used to measure formalization: (1) “This organization has a large number of written rules and procedures,” (2) “A manual with rules and procedures exist and is easily accessible,” (3) “There are complete descriptions for all positions in this organization,” (4) “The organization has a written document for performance of almost all employees,” and (5) “There is a formally organized introduction program for all newcomers in the organization.” All items measuring formalization and job autonomy had response alternatives ranging from 1 (totally disagree) to 5 (totally agree). Degree of professionalization was measured through the question ‘Approximately how large a proportion of your employees have higher academic education’ and is measured in per cent (M = 38.7, STD = 38.8). Even though this is far from a perfect measure of professionalization, it contains what most studies highlight as one of the main characteristics, namely “higher academic education” (Abbott Citation1988; Hwang and Powell Citation2009). also shows that this item is correlating as expected with task or technology (for instance significantly and negatively for tasks like agriculture, industry, and construction where we would expect low professionalization, and positive for financial services, education, and health service where we would expect high professionalization), indicating a predictive validity for the measure of professionalization. The same can be said for measures on formalization as it is significantly correlated with sectors where we would expect so (positively with energy, industry, and health, and negative in for instance higher education).

As indicators of formalization and managerial autonomy are reflective composites originating from the same source, common method bias may be threat to the reliability of the findings. Several steps were taken to reduce this problem, following the advice of Jakobsen and Jensen (Citation2015). Overall, several measures were taken ex-ante, during the design of the questionnaire to separate the two conceptually different items empirically. First, the items used are mainly descriptive, reducing the risk of social desirability responses. Second, items refer explicitly to different contexts (“my job” versus “this organization”) so that the respondent was provided with clearly different clues to what the items were supposed to measure. Third, items tapping the two constructs were widely separated in the questionnaire. In the extensive questionnaire, items measuring formalization were placed in section 22 while items measuring autonomy were placed in section 51. This assures that responses were given with a substantial time lag between them. We also conducted several empirical tests ex-post. First, we conducted a Harman’s single factor test for common method variance. The one-factor solution explained 35% of the variation, well below the 50% threshold often applied. In addition, we conducted a confirmatory factor analysis with the two reflective scales (formalization and job autonomy), resulting in a rather good model fit (RMSEA = .073, CFI = .936, SRMR = .035). Second, a marker variable approach was used (Lindell and Whitney Citation2001). Four items measuring prosocial motivation occurred in between the items measuring formalization and autonomy. As prosocial motivation is an individual-level characteristic, it is theoretically and conceptually unrelated to organization characteristics like formalization and autonomy. The scale measuring prosocial motivation showed good internal consistency (alpha = .86, see Jacobsen Citation2021). The zero-order correlations between the scale measuring prosocial motivation, and the scales measuring formalization and autonomy were respectively .01 and −.05, none of them significant at the −05-level. As noted by Lindell and Whitney (Citation2001, 115), “the smallest correlation among the manifest variables provides a reasonable proxy for CMV (common method variance),” again indicating low CMV in this dataset. Finally, as noted above, the measures on formalization and autonomy differ significantly on their zero-order correlations with sector/industry where data is collected from another source. If there was a clear CMV in the data, the correlations should have displayed a higher degree of similarity. Although these tests never can be a guarantee against common factors, the results indicate that the two phenomena are empirically distinct from each other.

Task/technology was controlled for using the sectorial categorization utilized by the national statistical bureau. Agriculture/forestry/primary goods were selected as base category. We also split health institutions (hospitals) from social services and institutions for care to account for different professional composition of staff. A similar split was made between basic (primary and secondary) education and higher education (universities/colleges), again based on the notion of different professionalization. Organizational size was measured through the number of employees (full time equivalents from public register data). Since there are relatively many small organizations in Norway, particularly among purely private firms, size was logarithmically transformed (M = 4.7, STD = 1.8). Hierarchical level of the manager was measured on two levels: 1 = top manager, 0 = lower-level managers.

Analysis

First, zero-order correlations between the variables were estimated to check for possibilities of collinearity. None of the correlations are so high as to fear for collinearity (highest Pearson’s r = 0.53) (full bivariate correlations between control variables are available on request to the author).

Second, to investigate the possibility of nested data (managers within organizations within businesses), a three-level hierarchical linear regression analysis was conducted. First, principal component factor analysis (orthogonal varimax rotation) on the eight items intended to measure formalization and autonomy resulted in two factors with Eigenvalues higher than 1 with the items scoring as expected (factor loadings between .67 and .85). The factor (regression) scores were used as indicators on job autonomy and formalization in the multilevel regression. The intraclass correlation (ICC) at the organization level was 0.025, and not significant (confidence interval at 5%-level overlapping zero), while the ICC at business level was 0.05. The results indicate that a two or three level model will yield little extra to a simpler one-level model controlling for business level characteristics (task/technology). It furthermore specifies that the data show results for individual managers in an organizational context more than organizations. A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted to test the validity of the measurement of the two latent variables “formalization” (originally five items) and “autonomy” (three items). Comparing different models resulted in a reduction of items to measure formalization to three (items (2), (3) and (4) described in the methods section), as this yielded the model with the best fit (RMSA = 0.024, CFI = 0.99, SRMR = 0.020). Finally, to test the hypotheses, a structural equation model analysis (SEM) applying a gaussian distribution model was conducted using STATA 16.1 (). The model obtained very good fit indices (RMSA = 0.036, CFI = 0.936, SRMR = 0.020) even though the chi-square was highly significant, something very common with large samples.

Table 2. Zero-order correlations (Pearson’s r) between variables in the analysis.

Table 2. (Continued).

Table 3. Results from structural equation modeling (SEM). Reference category organization type = Pure private company. N = 2488. Standardized coefficients.

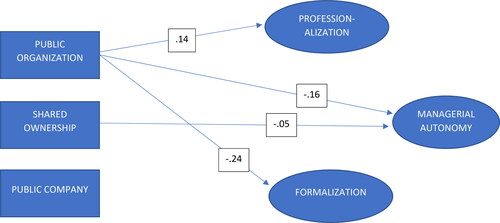

To test the robustness of this model, three ordinary OLS regression analyses were conducted using the regression factor score for job autonomy as the dependent variable, yielding highly similar results to the ones estimated in the SEM. A similar analysis was conducted on a sub-sample of organizations represented by two or more managers (N = 2001, number of organizations = 807). The results were strikingly similar, with the same significant paths and a slightly worse, but still highly acceptable, model fit (RMSA = 0.028, CFI = 0.97, SRMR = 0.022). shows he final model with only significant paths (.05-level).

Figure 1. Path diagram showing direct and indirect effects on organizational form on perceived managerial autonomy. Standardized coefficients. Only paths significant at the .05 level or lower are displayed. Effects of control variables omitted.

As there are no significant correlations between the two assumed mediating variables (professionalization and formalization) and the dependent variable (autonomy), there cannot be any indirect effects of organizational type (Hayes and Preacher Citation2014). Organizational type has a direct effect on managerial autonomy, in the sense that perceived autonomy decreases as one moves from the purely private organization via shared ownership to the purely public organizations. Thus, hypothesis H1 is mostly supported. The deviation here is public companies where mangers do not report less job autonomy than their colleagues in private organizations. As hypothesized in H3a, pure public organizations are far more professionalized than both hybrid and pure private organizations. More surprising is the finding that pure public organizations are less bureaucratized than private and hybrid organizations, thus not corroborating hypothesis H2a. Neither hypothesis H2b—that higher formalization is associated with lower autonomy, nor hypothesis H3b—that professionalization should be associated with lower autonomy, are supported by the data.

The multivariate analysis indicates that the best predictor of formalization is organizational size, in addition to what type of task or technology that is performed in the organization. Professionalization, on the other hand, is best predicted by task or technology.

Discussion

Given that job autonomy—the freedom to choose tasks and procedures without conferring with others—is an important element in managerial autonomy, this study supports the general idea that managers in public organizations feel more constrained than their counterparts in private organizations. This is the case even when controlling for size and task, elements that have been largely missing from previous studies on the topic (Boyne Citation2002). Thus, hypothesis 1 is clearly corroborated through this study, supporting the general assumptions made in theory and previous studies (Andrews, Boyne, and Walker Citation2011; Andrews and Esteve Citation2015; Boyne Citation2002; Pollitt Citation2013; Rainey Citation1989, Citation2014). However, it stands in contrast to the relative recent findings presented by Hansen and Villadsen (Citation2010) in a Danish study, reporting higher job autonomy for public than private managers. That study did not, however, distinguish between public and hybrid organizations, and does not control for size and task. The current study clearly shows the importance of including these variables in a comparison of managerial job autonomy between public and private organizations (see Boyne Citation2002, for a similar argument).

Furthermore, the findings in this study support the notion that a public company context is associated with higher managerial autonomy, not significantly different to the one reported by managers in private organizations. Somewhat more surprising is the finding that managers in companies with shared ownership perceive lower job autonomy than those in private companies, many of them sharing the same legal organizational form (limited company). One explanation may by the “double standards” possibly imposed on managers by having two different types of owners with potentially different interests, values, and preferences. Such diverse ownership may actualize a “multiple principle” problem, resulting in complex governance systems aimed at satisfying quite different objectives (Voorn, Genugten, and Thiel Citation2019). The outcome may be conflicting signals from owners putting more restrictions on managers in such organizations.

Quite unexpected is the finding that professionalization measured through the number of employees with higher education in public organizations is not an element reducing perceived managerial job autonomy. The hypotheses in this study regarding professionalization and managerial autonomy are clearly derived from a conflictual perspective in the sense that they presuppose a conflict situation between managers and professionals (Scott Citation2008; Thomas and Hewitt Citation2011). In this perspective, a conflict between different logics—managerialism based on organizational logics rooted in performance and efficiency versus professionalism grounded in specialized knowledge on performance of a specific task—is assumed (Noordegraaf Citation2011). In contrast to such a conflictual perspective stands a perspective based on discourse and cooperation between managers and professionals where they seek understanding of each other’s positions, working to find a common ground to be able to cooperate in a way that is fruitful for both the profession and the organization (Liewellyn Citation2001). A conflictual view also overlooks the fact that many managers in professional organizations are professionals themselves (Farrell and Morris Citation2003; Hwang and Powell Citation2009), thus possessing enough knowledge of employees’ work necessary to overlook and control it. All in all, one should probably not overestimate the role of professionals in limiting the manager’s autonomy.

Another surprise is that formalization is not significantly related to lower managerial job autonomy. One explanation for this may be that the focus in this study is on individual managerial job autonomy, while the questions concerning formalization address the organizational level. Formalization is commonly strongest at the operative levels of the organization as a mean to regulate production processes, and to a lesser degree managers’ jobs (Mintzberg Citation1979, 92). Consequently, organizational formalization may not impact on managerial autonomy, but rather on lower-level employees’ autonomy. This interpretation is partly supported by the fact that the perception of formalization in this study is negative correlated to hierarchical level of the manager.

The most surprising finding is that purely public organizations are not more formalized than private organizations as other studies have led us to assume (Boyne Citation2002; Rainey Citation2014). On the contrary, they are—in general—less formalized. This result holds even when controlling for other important confounders known to correlate with formalization from several previous studies: size and task (technology) (Andrews, Boyne, and Mostafa Citation2017). Although a bit peripheral to the initial research question of the project, this finding deserves a thorough reflection. When the term “public organization” is used, one usually thinks of organizational units placed close—both formally and geographically—to political entities like cabinets, parliaments, and councils. This has also been the empirical objects in several studies concluding with higher formalization in the public sector (Feeney and Rainey Citation2010; Rainey and Chun Citation2005). But, as discussed earlier in this article, autonomy varies largely between different organizations within the “purely” public sector. Agencification—i.e., the establishment of semi-autonomous units, often regulated by specific laws and having their own boards—is a trend that probably has increased the variation in organizational autonomy within the public sector (Krause and Van Thiel Citation2019; Maggetti and Verhoest Citation2014; Verhoest et al. Citation2010). If the public sector is extended—as it is in this study—to service providing organizations, the public sector will include schools, hospitals, institutions for the elderly, research institutes, universities and colleges, libraries, and theaters. Many of these organizations are quite far removed from direct, daily political influence, and they work with tasks that are hard to standardize and thus to bureaucratize. In Mintzberg’s (Citation1979) terms, many organizations in the public sector will probably more resemble professional bureaucracies—even perhaps adhocracies—than machine bureaucracies on which the classic notions of bureaucracy rest.

Another explanation may be due to systematic differences between managers applying for and getting selected to managerial positions in public and private organizations (Kjeldsen and Jacobsen Citation2013, Jacobsen Citation2021). Combined with empirical findings that perceived and factual organizational traits may be weakly correlated (Kaufmann and Feeney Citation2012), there is a possibility that managers in public organizations have a higher tolerance for rules and regulations than those in private organizations. A consequence may be reporting less formalization than what may be the “objective” situation. This may also explain, at least partly, the missing link between formalization and autonomy. If this is the case, studies using objective indicators of formalizations should be used in comparisons between public, hybrid, and private organizations. Given the scarce, almost non-existent, empirical studies comparing private and public organizations and controlling for (at least) size and task, one should be open for the possibility that the general picture of public organizations as more formalized and bureaucratized is just based on a myth.

The empirical analysis also indicates that the main task or technology of the organization, in addition to size, is probably the most important factor for explaining formalization. First, the analysis shows that the financial sector and industry/manufacturing—two sectors with tasks that are quite possible to standardize (and digitalize)—are by far the most bureaucratic. In addition, formalization is strong in the oil and energy sector, something that quite easily can be explained by strict standards for security. An oil “blow-out” or water dam collapse will have extreme consequences, and thus requires strict regimes for security and control, usually in the form of elaborated rules, routines, and standard procedures. Although these explanations are linked to variables that are controlled for in the study, they are important in understanding the enormous variation of organizations that we find with both the public and the private sectors (Desmarais and de Chatillon Citation2010). A rather obvious conclusion from this study is that studies of formalization at least should take into consideration the effects of size and task/technology.

Future studies comparing managerial job autonomy across private, public and hybrid organizations should search for other mechanisms that may mediate the effect of context on autonomy. One possible element often thought to distinguish between public and private organizations, is the degree of goal ambiguity (Rainey and Jung Citation2015). Another element worth of study is centralization, as public organizations may be more centralized (Boyne Citation2002). A third element is the amount of stakeholders managers must take into consideration when making decisions, as it is commonly assumed that managers in purely public organization must confer with a significantly larger group of stakeholders than what is the case in private organizations (Perry and Rainey Citation1988). Surely other elements should be included to understand why the context of purely public organizations seems to produce lower managerial autonomy. Furthermore, different types of autonomy, for instance to recruit personnel, to make strategic decisions, and freedom to prioritize within budgetary frames, should become object to empirical studies as well, constructing a more detailed picture of similarities and differences between managing in different organizational contexts.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Dag Ingvar Jacobsen

Dag Ingvar Jacobsen is a professor of political science and management at Agder University (Kristiansand, Norway). He has worked extensively on relations between politics and administration, leadership in public organizations, as well as organizational change. He is currently involved in studying both operative and democratic effects of inter-municipal cooperation.

References

- Abbott, A. D. 1988. The System of Professions. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Abrutyn, S. 2009. “Toward a General Theory of Institutional Autonomy.” Sociological Theory 27(4):449–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9558.2009.01358.x.

- Andersen, J. A. 2010 Public versus Private Managers: How Public and Private Managers Differ in Leadership Behavior. Public Administration Review. 70(1):131–141. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6210.2009.02117.x.

- Andrews, R., G. A. Boyne, and R. M. Walker. 2011. “Dimensions of Publicness and Organizational Performance: A Review of the Evidence.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 21(Supplement 3):I301–I319. doi: 10.1093/jopart/mur026.

- Andrews, R., G. Boyne, and A. M. S. Mostafa. 2017. “When Bureaucracy Matters for Organizational Performance: Exploring the Benefits of Administrative Intensity in Big And Complex Organizations.” Public Administration 95(1):115–39. doi: 10.1111/padm.12305.

- Andrews, R., and M. Esteve. 2015. “Still Like Ships That Pass in the Night? The Relationship Between Public Administration and Management Studies.” International Public Management Journal 18(1):31–60. doi: 10.1080/10967494.2014.972483.

- Andrews, R., L. Ferry, C. Skelcher, and P. Wegorowski. 2020. “Corporatization in the Public Sector: Explaining the Growth of Local Government Companies.” Public Administration Review 80(3):482–93. doi: 10.1111/puar.13052.

- Aucoin, P. 1990. “Administrative Reform in Public Management: Paradigms, Principles, Paradoxes and Pendulums.” Governance 3(2):115–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0491.1990.tb00111.x.

- Battilana, J. and Dorado, S. 2010. Building Sustainable Hybrid Organizations: The Case of Commercial Microfinance Institutions. Academy of Management Journal, 53(6):1419–1440. doi: 10.5465/amj.2010.57318391.

- Bel, G., M. Esteve, J. C. Garrido, and J. L. Zafra-Gomez. 2021. “The Costs of Corporatization: Analysing the Effects of Forms of Governance.” Public Administration. In press. doi: 10.1111/padm.12713.

- Bezes, P., and G. Jeannot. 2018. “Autonomy and Managerial Reforms in Europe: Let or Make Public Managers Manage?” Public Administration 96(1):3–22. doi: 10.1111/padm.12361.

- Bilodeau, N., C. Laurin, and A. Vining. 2006. “‘Choice of Organizational Form Makes a Real Difference’: The Impact of Corporatization on Government Agencies in Canada.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 17(1):119–47. doi: 10.1093/jopart/mul014.

- Boon, J. A. N., and J. A. N. Wynen. 2017. “On the Bureaucracy of Bureaucracies: Analysing the Size and Organization of Overhead in Public Organizations.” Public Administration 95(1):214–31. doi: 10.1111/padm.12300.

- Bosetzky, H. 1980. “Forms of Bureaucratic Organization in Public and Industrial Administrations.” International Studies of Management & Organization 10(4):58–73. doi: 10.1080/00208825.1980.11656302.

- Boyne, G. A. 2002. “Public and Private Management: What's the Difference?” Journal of Management Studies 39(1):97–122. doi: 10.1111/1467-6486.00284.

- Bozeman, B. 2013. “What Organization Theorists and Public Policy Researchers Can Learn from One Another: Publicness Theory as a Case-in-Point.” Organization Studies 34(2):169–88. doi: 10.1177/0170840612473549.

- Bozeman, B., P. N. Reed, and P. Scott. 1992. “Red Tape and Task Delays in Public and Private Organizations.” Administration & Society 24(3):290–322. doi: 10.1177/009539979202400302.

- Bruton, G. D., Peng, M. W., Ahlstrom, D., Stan, C. and Xu, K. H. 2015. State-owned Enterprises around the World as Hybrid Organizations. Academy of Management Perspectives. 29(1):92–114. doi: 10.5465/amp.2013.0069.

- Chen, C. A. 2012. “Explaining the Difference of Work Attitudes Between Public and Nonprofit Managers: The Views of Rule Constraints and Motivation Styles.” The American Review of Public Administration 42(4):437–60. doi: 10.1177/0275074011402192.

- Chen, C. A., and H. G. Rainey. 2014. “Personnel Formalization and the Enhancement of Teamwork. A Public-Private Comparison.” Public Management Review 16(7):945–68. doi: 10.1080/14719037.2013.770057.

- Christensen, T., and P. Laegreid. 2011. “Beyond NPM? Some Development Features.” Pp. 391–404 in The Ashgate Research Companion to New Public Management, edited by T. Christensen and P. Laegreid. Farnham, Surrey: Routledge.

- Currie, G., and S. J. Procter. 2005. “The Antecedents of Middle Managers' Strategic Contribution: The Case of a Professional Bureaucracy.” Journal of Management Studies 42(7):1325–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6486.2005.00546.x.

- de Bruijn, H. 2011. Managing Professionals. Oxon: Routledge.

- Desmarais, C., and E. A. de Chatillon. 2010. “Are There Still Differences Between the Roles of Private and Public Sector Managers?” Public Management Review 12(1):127–49. doi: 10.1080/14719030902817931.

- Dickinson, H., I. Snelling, C. Ham, and P. C. Spurgeon. 2017. “Are We Nearly There Yet? A Study of the English National Health Service as Professional Bureaucracies.” Journal of Health Organization and Management 31(4):430–44. doi: 10.1108/JHOM-01-2017-0023.

- Dill, W. R. 1958. “Environment as an Influence on Managerial Autonomy.” Administrative Science Quarterly 2(4):409–43. doi: 10.2307/2390794.

- DiPrete, T. A. 1987. “The Professionalization of Administration and Equal Employment Opportunity in the U.S. Federal Government.” American Journal of Sociology 93(1):119–40. doi: 10.1086/228708.

- Doherty, B., Haugh, H, and Lyon, F. 2014, “Social Enterprises as Hybrid Organizations: A Review and Research Agenda.” International Journal of Management Review 16(4):417–436. doi: 10.1111/ijmr.12028.

- Donaldson, L. 2001. The Contingency Theory of Organizations. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Donaldson, L., and B N. F. Luo. 2014. “The Aston Programme Contribution to Organizational Research: A Literature Review.” International Journal of Management Reviews 16(1):84–104. doi: 10.1111/ijmr.12010.

- Edelenbos, J., Van Buuren, A. and Klijn, E. H, 2013. Connective Capacities of Network Managers A comparative study of management styles in eight regional governance networks. Public Management Review. 15(1)131–159. doi: 10.1080/14719037.2012.691009.

- Egeberg, M., and J. Trondal. 2009. “Political Leadership and Bureaucratic Autonomy: Effects of Agencification.” Governance 22(4):673–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0491.2009.01458.x.

- Emery, Y., and D. Giauque. 2005. “Employment in the Public and Private Sectors: Toward a Confusing Hybridization Process.” International Review of Administrative Sciences 71(4):639–57. doi: 10.1177/0020852305059603.

- Empson, L. 2017. Leading Professionals: Power, Politics, and Prima Donnas. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Evans, T. 2011. “Professionals, Managers and Discretion: Critiquing Street-Level Bureaucracy.” British Journal of Social Work 41(2):368–86. doi: 10.1093/bjsw/bcq074.

- Farrell, C., and J. Morris. 2003. “The `Neo-Bureaucratic' State: Professionals, Managers and Professional Managers in Schools, General Practices and Social Work.” Organization 10(1):129–56. doi: 10.1177/1350508403010001380.

- Feeney, M. K., and H. G. Rainey. 2010. “Personnel Flexibility and Red Tape in Public and Nonprofit Organizations: Distinctions Due to Institutional and Political Accountability.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 20(4):801–26. doi: 10.1093/jopart/mup027.

- Flinders, M. 2009. “Review Article: Theory and Method in the Study of Delegation: Three Dominant Traditions.” Public Administration 87(4):955–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9299.2009.01783.x.

- Freidson, E. 1970. Profession of Medicins. A Study of the Sociology of Applied Knowledge. Chicago: University of Chacago Press.

- Grossi, G., and C. Reichard. 2008. “Municipal Corporatization in Germany and Italy.” Public Management Review 10(5):597–617. doi: 10.1080/14719030802264275.

- Hackman, J. R., and G. R. Oldham. 1980. Work Redesign. London: Addison-Wesley.

- Hall, K., R. Miller, and R. Millar. 2016. “Public, Private or Neither? Analysing the Publicness of Health Care Social Enterprises.” Public Management Review 18(4):539–57. doi: 10.1080/14719037.2015.1014398.

- Hansen, J. R., and A. R. Villadsen. 2010. “Comparing Public and Private Managers' Leadership Styles: Understanding the Role of Job Context.” International Public Management Journal 13(3):247–74. doi: 10.1080/10967494.2010.503793.

- Hayes, A. F., and K. J. Preacher. 2014. “Statistical Mediation Analysis with a Multicategorical Independent Variable.” The British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology 67(3):451–70. doi: 10.1111/bmsp.12028.

- Holdaway, E. A., J. F. Newberry, D. J. Hickson, and R. P. Heron. 1975. “Dimensions of Organizations in Complex Societies - Educational Sector.” Administrative Science Quarterly 20(1):37–58. doi: 10.2307/2392122.

- Hwang, H., and W. W. Powell. 2009. “The Rationalization of Charity: The Influences of Professionalism in the Nonprofit Sector.” Administrative Science Quarterly 54(2):268–98. doi: 10.2189/asqu.2009.54.2.268.

- Jacobsen, D. I. 2021. “Motivational Differences? Comparing Private, Public and Hybrid Organizations.” Public Organization Review 21(3):561–75. doi: 10.1007/s11115-021-00511-x.

- Jakobsen, M., and R. Jensen. 2015. “Common Method Bias in Public Management Studies.” International Public Management Journal 18(1):3–30. doi: 10.1080/10967494.2014.997906.

- Jermier, J. M., and S. Kerr. 1997. “Substitutes for Leadership: The Meaning and Measurement'' - Contextual Recollections and Current Observations.” The Leadership Quarterly 8(2):95–101. doi: 10.1016/S1048-9843(97)90008-4.

- Johanson, J.-E., and J. Vakkuri. 2018. Governing Hybrid Organizations. Milton Park: Routledge.

- Kaufmann, W., and M. K. Feeney. 2012. “Objective Formalization, Perceived Formalization and Perceived Red Tape Sorting out Concepts.” Public Management Review 14(8):1195–214. doi: 10.1080/14719037.2012.662447.

- Kerr, S., and J. M. Jermier. 1978. “Substitutes for Leadership - Their Meaning and Measurement.” Organizational Behavior and Human Performance 22(3):375–403. doi: 10.1016/0030-5073(78)90023-5.

- Kettl, D. A. 2002. The Transformation of Governance. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press.

- Kettl, D. F. 1997. “The Global Revolution in Public Management: Driving Themes, Missing Links.” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 16(3):446–62. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6688(199722)16:3<446::AID-PAM5>3.0.CO;2-H.

- Kjeldsen, A. M., and C. B. Jacobsen. 2013. “Public Service Motivation and Employment Sector: Attraction or Socialization?” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 23(4):899–926. doi: 10.1093/jopart/mus039.

- Krause, T., and S. Van Thiel. 2019. “Perceived Managerial Autonomy in Municipally Owned Corporations: Disentangling the Impact of Output Control, Process Control, and Policy-Profession Conflict.” Public Management Review 21(2):187–211. doi: 10.1080/14719037.2018.1473472.

- Larson, M. S. 1977. The Rise of Professionalism: A Sociological Analysis. Berkeley: University oif California Press.

- Leicht, K. T., and M. L. Fennell. 1997. “The Changing Organizational Context of Professional Work.” Annual Review of Sociology 23(1):215–31. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.23.1.215.

- Liewellyn, S. 2001. “Two-Way Windows': Clinicians as Medical Managers.” Organization Studies 22(4):593.

- Lindell, M. K., and D. J. Whitney. 2001. “Accounting for Common Method Variance in Cross-Sectional Research Designs.” The Journal of Applied Psychology 86(1):114–21. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.86.1.114.

- Lindlbauer, I., V. Winter, and J. Schreyogg. 2016. “Antecedents and Consequences of Corporatization: An Empirical Analysis of German Public Hospitals.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 26(2):309–26. doi: 10.1093/jopart/muv016.

- Maggetti, M., and K. Verhoest. 2014. “Unexplored Aspects of Bureaucratic Autonomy: A State of the Field and Ways Forward.” International Review of Administrative Sciences 80(2):239–56. doi: 10.1177/0020852314524680.

- March, J. G. and Olsen, J. P. 1989. Rediscovering Institutions. New York, Free Press.

- Marsden, P. V., C. R. Cook, and A. L. Kalleberg. 1994. “Organizational Structures – Coordination and Control.” American Behavioral Scientist 37(7):911–29. doi: 10.1177/0002764294037007005.

- Megginson, W. L., and J. R. Netter. 2001. “From State to Market: A Survey of Empirical Studies on Privatization.” Journal of Economic Literature 39(2):321–89. doi: 10.1257/jel.39.2.321.

- Meier, K. J., and J. L. J. O'Toole. 2011. “Comparing Public and Private Management: Theoretical Expectations.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 21(Supplement 3):i283–99. doi: 10.1093/jopart/mur027.

- Meyer, M. W. 1987. “The Growth of Public and Private Bureaucracies.” Theory and Society 16(2):215–35. doi: 10.1007/BF00135695.

- Mintzberg, H. 1979. The Structuring of Organizations. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall.

- Mintzberg, H. 1998. “Covert Leadership: Notes - Knowledge Workers Respond to Inspiration, Not Supervision.” Harvard Business Review 76(6):140–1.

- Morales, F. N., R. Wittek, and L. Heyse. 2013. “After the Reform: Change in Dutch Public and Private Organizations.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 23(3):735–54. doi: 10.1093/jopart/mus006.

- Noordegraaf, M. 2011. “Remaking Professionals? How Associations and Professional Education Connect Professionalism and Organizations.” Current Sociology 59(4):465–88. doi: 10.1177/0011392111402716.

- Nutt, P. C. 2000. “Decision-Making Success in Public, Private and Third Sector Organizations: Finding Sector Dependent Best Practice.” Journal of Management Studies 37(1):77–108. doi: 10.1111/1467-6486.00173.

- Nutt, P. C., and R. W. Backoff. 1993. “Transforming Public Organizations with Strategic Management and Strategic Leadership.” Journal of Management 19(2):299–347. doi: 10.1177/014920639301900206.

- Olsen, J. P. 2009. “Democratic Government, Institutional Autonomy and the Dynamics of Change.” West European Politics 32(3):439–65. doi: 10.1080/01402380902779048.

- Osborne, D., and T. Gaebler. 1992. Reinventing Government: The Entrepreneurial Spirit is Transforming the Public Sector. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

- Overman, S., and S. van Thiel. 2016. “Agencification and Public Sector Performance: A systematic comparison in 20 countries.” Public Management Review 18(4):611–35. doi: 10.1080/14719037.2015.1028973.

- Perry, J. L., and H. G. Rainey. 1988. “The Public-Private Distinction in Organization Theory: A Critique and Research Strategy.” The Academy of Management Review 13(2):182–201. doi: 10.5465/amr.1988.4306858.

- Pesch, U. 2008. The Publicness of Public Administration. Administration & Society. 40(2):170–193. doi: 10.1177/0095399707312828.

- Podsakoff, P. M., B. P. Niehoff, S. B. MacKenzie, and M. L. Williams. 1993. “Do Substitutes for Leadership Really Substitute for Leadership? An Empirical Examination of Kerr.” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 54(1):1–25. doi: 10.1006/obhd.1993.1001.

- Pollitt, C. 2001. “Convergence: The Useful Myth?” Public Administration 79(4):933–47. doi: 10.1111/1467-9299.00287.

- Pollitt, C. 2013. “First Link.” Pp. 88–97 in Context in Public Policy and Management: The Missing Link?, edited by C. Pollitt. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

- Pollitt, G., and G. Bouckaert. 2011. Public Management Reform: A Comparative Analysis. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Poole, M., R. Mansfield, and J. Gould‐Williams. 2006. “Public and Private Sector Managers over 20 Years: A Test of the ‘Convergence Thesis’.” Public Administration 84(4):1051–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9299.2006.00626.x.

- Psychogios, A. G., A. Wilkinson, and L. T. Szamosi. 2009. “Getting to the Heart of the Debate: TQM and Middle Manager Autonomy.” Total Quality Management & Business Excellence 20(4):445–66. doi: 10.1080/14783360902781949.

- Raelin, J. A. 1989. “An Anatomy of Autonomy: Managing Professionals.” Academy of Management Perspectives 3(3):216–28. doi: 10.5465/ame.1989.4274740.

- Rainey, H. C., and C. S. Jung. 2015. “A Conceptual Framework for Analysis of Goal Ambiguity in Public Organizations.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 25(1):71–99. doi: 10.1093/jopart/muu040.

- Rainey, H. G. 1989. “Public Management: Recent Research on the Political Context and Managerial Roles, Structures, and Behaviors.” Journal of Management 15(2):229–50. doi: 10.1177/014920638901500206.

- Rainey, H. G. 2011. “Sampling Designs for Analyzing Publicness: Alternatives and Their Strengths and Weaknesses.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 21(Supplement 3):I321–45. doi: 10.1093/jopart/mur029.

- Rainey, H. G. 2014. Understanding and Managing Public Organizations. 5th ed. San Fransisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Rainey, H. G., and Y. H. Chun. 2005. “Public and Private Management Compared.” Pp 72–102 in The Oxford Handbook of Public Management, edited by E. Ferlie, L. E. Lynn, and C. Pollit. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Reimann, B. C. 1973. “On the Dimensions of Bureaucratic Structure: An Empirical Reappraisal.” Administrative Science Quarterly 18(4):462–76. doi: 10.2307/2392199.

- Ritzer, G. 1975. “Professionalization, Bureaucratization and Rationalization: The Views of Max Weber.” Social Forces 53(4):627–34. doi: 10.2307/2576478.

- Rutherford, A. 2016. “Reexamining Causes and Consequences: Does Administrative Intensity Matter for Organizational Performance?” International Public Management Journal 19(3):342–69. doi: 10.1080/10967494.2015.1032459.

- Scott, P. G., and S. Falcone. 1998. “Comparing Public and Private Organizations - An Exploratory Analysis of Three Frameworks.” American Review of Public Administration 28(2):126–45. doi: 10.1177/027507409802800202.

- Scott, W. R. 2008. “Lords of the Dance: Professional as Institutional Agents.” Organization Studies 29(2):219–38. doi: 10.1177/0170840607088151.

- Terry, L. D. 2003. Leadership of Public Bureaucracies. 2nd ed. New York: M.E. Sharpe.

- Thomas, P., and J. Hewitt. 2011. “Managerial Organization and Professional Autonomy: A Discourse-Based Conceptualization.” Organization Studies 32(10):1373–93. doi: 10.1177/0170840611416739.

- Verhoest, K., P. G. Roness, B. Verschuere, K. Rubecksen, and M. MacCarthaigh. 2010. Autonomy and Control of State Agencies. Comparing States and Agencies. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Verhoest, K., S. van Thiel, G. Bouckaert, and P. Laegreid. 2012. Government Agencies: Practices and Lessons from 30 Countries. New York: Palgrave Manmillan.

- Voorn, B., R. T. Borst, and R. Blom. 2020. “Business Techniques as an Explanation of the Autonomy-Performance Link in Corporatized Entities: Evidence from Dutch Municipally Owned Corporations.” International Public Management Journal: 1–17. In press. doi: 10.1080/10967494.2020.1802632.

- Voorn, Bart, Marieke Genugten, and Sandra Thiel. 2019. “Multiple Principals, Multiple Problems: Implications for Effective Governance and a Research Agenda for Joint Service Delivery.” Public Administration 97(3):671–85. doi: 10.1111/padm.12587.

- Wagner, S. M., C. Rau, and E. Lindemann. 2010. “Multiple Informant Methodology: A Critical Review and Recommendations.” Sociological Methods & Research 38(4):582–618. doi: 10.1177/0049124110366231.

- Whitford, A. B. 2002. “Bureaucratic Discretion, Agency Structure, and Democratic Responsiveness: The Case of the United States Attorneys.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 12(1):3–27. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jpart.a003523.

- Williamson, A. L. 2011. “Assessing the Core and Dimensional Approaches. Human Resource Management in Public, Private, and Charter Schools.” Public Performance & Management Review 35(2):251–80. doi: 10.2753/PMR1530-9576350202.

- Wynen, J., K. Verhoest, E. Ongaro, and S. Van Thiel. 2014. “Innovation-Oriented Culture in the Public Sector Do Managerial Autonomy and Result Control Lead to Innovation?” Public Management Review 16(1):45–66.

- Yu-Chi, W. 2010. “An Exploration of Substitutes for Leadership: Problems and Prospects.” Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal 38(5):583–95.

- Yukl, G. 2013. Leadership in Organizations. 8th ed. Essex: Pearson Education Limited.

- Zibarras, L. D., and S. A. Woods. 2010. “A Survey of UK Selection Practices Across Different Organization Sizes and Industry Sectors.” Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 83(2):499–511. doi: 10.1348/096317909X425203.