Abstract

While leadership is one of the most discussed concepts in the social sciences, there is a need for more scholarly research that examines the ambiguous leadership position of middle managers, and how their leadership work is perceived in practice. In this article, we follow the recent research turn of adopting a social constructionist view of leadership, and make use of metaphors to answer the following research question: how are middle managers in the public sector managing the expectations and demands from both top management and subordinates, and what are some of its consequences? We study this in the public sector, a context of particular importance but one that has often been neglected in previous research. Through a qualitative in-depth case study, based on observations, interviews, and organizational documents, our findings show that middle managers were trapped in the way they moved between being constructed as a leader and a follower, along what we call a leader-follower pendulum, and in the way they enacted two different leadership metaphors: the buddy and the commander. These aspects jointly contribute to a complex and ambiguous situation for middle managers, which in turn gives rise to alienation and the constant strive to fit in, something that we metaphorically refer to as “karma chameleon.”

Introduction

Middle managers (MMs) occupy a particularly interesting and important position within leadership processes (Gleeson and Knights Citation2008; Harding, Lee, and Ford Citation2014). They are located in the zone between the work of allegedly visionary leaders and the demand for direction and operational instructions in day-to-day work (Shi, Markoczy, and Dess Citation2009). Seen in this view, middle managers “muddle in the middle” (Newell and Dopson Citation1996) and are vulnerable to criticism coming from two directions (Dopson and Stewart Citation1990; Redman, Wilkinson, and Snape Citation1997; Sims Citation2003). Studies show that middle managers thus need to cope with this intermediary position in-between strategic and visionary thinking and operational concerns and the implementation of strategy and tactics by developing identities that help them handle this situation (Huy Citation2002; Thomas and Linstead Citation2002; Linstead and Thomas Citation2002). In addition to being stuck between the demands of top management and subordinates’ expectations of day-to-day routine (Gleeson and Knights Citation2008; Harding et al. Citation2014), MMs are also interesting and important to study because they can become constructed as both leaders and followers, as they are subordinates to higher-level managers (Alvesson Citation2019; Anicich and Hirsh Citation2017). However, since many existing studies have been grounded in a binary structure, in which there are two kinds of people, leaders and followers, and thus neglect the idea of leadership as distributed and dependent on social processes (Collinson Citation2014), calls are continuously made to provide in-depth descriptions of how MMs deal with their role as superiors, middlemen, and subordinates (Alvesson Citation2020; Gjerde and Alvesson Citation2020).

In this article, we answer this call and further build on and explore the above-mentioned insights as to how middle managers construct their identities in situ and on the basis of the social norms that regulate what is treated as legitimate leadership activities under specific conditions. We do this in the public sector context, which is of particular importance. In this context, leadership and the role of MMs have been highlighted as critical to organizational success, in which MMs are seen as playing a particularly important, albeit ambiguous, role (Gleeson and Knights Citation2008; Knies and Leisink Citation2014; Orazi, Turrini, and Valotti Citation2013). The public sector context includes certain particularities and dualities. For example, being impacted by the principle of equality and the public service provision, on the one hand, and being pressured to meet financial goals and to focus on profit-making, on the other (Blom et al. Citation2020; Christensen et al. Citation2007; Papenfuß and Keppeler Citation2020). We would expect to see this translated into a pressured role, as MMs are responsible for ensuring that subordinates execute their operational activities effectively, and for making sure enough efforts are made in empowering, growing, and developing them. However, as comparatively few in-depth empirical studies have been conducted in a public sector context, how this unfolds in practice is unclear (Ancarani et al. Citation2021; Andersen et al. Citation2018; Kuipers et al. Citation2014; Van Wart Citation2013). This article is an attempt to advance knowledge on this issue, and we use a qualitative in-depth case study, based on observations, interviews, and organizational documents, to answer the following research question: how are MMs in the public sector managing the expectations and demands from both top management and subordinates, and what are some of its consequences? To acquire a rich understanding of the context surrounding this question, we adopt a social constructionist perspective of leadership, and make use of metaphors as a theoretical framework (Fairhurst Citation2009; Oberlechner and Mayer-Schoenberger Citation2002).

Our findings show that MMs were trapped in the way they moved between being constructed as leaders and followers, along what we call a leader–follower pendulum, and in the way they were engaged in enacting two different leadership metaphors: the buddy and the commander. These aspects jointly contribute to a complex and ambiguous situation for MMs, in turn giving rise to alienation and a constant strive to fit in, something that we refer to as “karma chameleon.” Here we propose the “chameleon leadership” metaphor, whose meaning is in line with how Boy George once explained the meaning of the song Karma Chameleon by the British band Culture Club, aka difficulty and fear of alienation, of standing up for one thing, and trying to appease everybody, which is ultimately an act determined by a lack of self-esteem (and, in our case, sufficient confidence on one’s professional role; see Eames Citation2020). In highlighting this predicament, the study makes several important contributions to the literature. First, we contribute to the literature on leadership and the role of MMs (e.g., Einola and Alvesson Citation2019; Gleeson and Knights Citation2008; Harding et al. Citation2014; Kempster and Gregory Citation2017; Newell and Dopson Citation1996), by providing a more detailed understanding of how MMs can be constructed as both leaders and followers, indicative of the “double rationality” of MMs (Gjerde and Alvesson Citation2020), a concept that moves leadership research beyond mainstream research grounded in the use of binary categories (“leader” vs” follower”; “manager” vs “subordinates,” etc.) (Alvesson Citation2019; Collinson Citation2014). Importantly, we add important nuances to existing arguments by suggesting that MMs’ “double rationality” does not occur at random but involves a contingency component. Second, we contribute to the leadership literature using metaphor analysis (e.g., Alvesson and Spicer Citation2011; Hernández-Amorós and Martínez Ruiz Citation2018; Oberlechner and Mayer-Schoenberger Citation2002; Ruth Citation2014), by introducing an alternative leadership metaphor; that of the leader as a chameleon figure, apprehending a grounded and fine-grained description of the complex and often ambiguous situation that MMs are expected to handle and from which they can construct meaningful identities and a sense of self-esteem. We add to the conceptual arguments regarding the importance and relevance of using leadership metaphors by grounding our suggested metaphor in empirical data that show how MMs’ engagement in leadership unfolds in a practical setting, especially in the public sector. Taken together, these two contributions respond to the call for more qualitative studies on how MMs engage in leadership processes (Azambuja and Islam Citation2019; Gjerde and Alvesson Citation2020), and in particular the call for more leadership studies in a public sector context (Andersen et al. Citation2018; Orazi et al. Citation2013).

This article is structured as follows. A theoretical background is offered emphasizing the view of leadership as a socially-, relationally-, and contextually embedded process, the important and interesting position of MMs within this process, and the particularly well-suited perspective of metaphors in making sense of the leadership complexities of MMs. This is followed by a description of the research setting and methods. The findings are then presented, followed by the discussion. Contributions, limitations, and suggestions for future research are provided at the end.

Theoretical background

Changing views on leadership and the role of MMs

To shed light on how leadership unfolds in everyday work, alternative views on leadership have emerged which oppose the traditional view of leadership as located in individuals (predominantly individual leaders); instead, leadership is emphasized as an ongoing social and ambiguous process involving a number of organizational actors, such as leaders, followers, and the context in which they interact (Crevani, Lindgren, and Packendorff Citation2010; Schweiger, Müller, and Güttel Citation2020). Such alternative views imply that we need to move away from romanticizing individual leaders and their individual abilities, and instead start viewing leadership as a socially constructed process wherein both leaders and followers emerge as an outcome of situated leadership activities (DeRue and Ashford Citation2010; Fairhurst and Grant 2010). This calls attention to how contexts and situations are defined, as they are arguably the basis for successful leadership practices. The definition of “the situational” to which specific leadership styles respond, is largely related to social norms (Bicchieri Citation2017; Young Citation2015; McAdams Citation1997) that regulate what coworkers expect from their leaders in terms of practical day-to-day guidance. Thus, social norms can be construed as the context wherein effective leadership is being executed. Importantly, however, instead of a priori prescribing what norms apply in a specific situation, specific situations and contexts need to be examined in situ, in the course of everyday work. In this view, wherein effective leadership work is construed as a dynamic social practice assessed on the basis of shared social norms, interpretations and meanings derived from what is done and talked about in relation to leadership are of key importance.

In everyday work, certain situations include ambiguities, i.e., situations in which it is not self-evident what actions the leader should take to cope with current or emerging challenges (Tourish Citation2014). Acknowledging leadership as a co-constructed social process means that we need to understand all organizational actors, such as leaders, followers, and the context in which they act, as including potential sources of ambiguity (Virtaharju and Liiri Citation2019). First, leaders themselves may be an important source of ambiguity, since they seldom fit into the narrow categories used by mainstream leadership literature to describe leaders (DeRue and Ashford Citation2010). Furthermore, leaders sometimes seem unsure about what they do when they lead, and are even uncertain if they are able or willing to be leaders in the first place. Second, subordinates do not only respond to the leader’s commands, but may also influence, support, and even resist the leader (Blom and Alvesson Citation2014). This suggests that subordinates are more active in constructing leadership and contributing to ambiguity and complexity, which largely contrasts how subordinates are depicted in traditional views on leadership. Finally, the broad social and organizational context is also a relevant source of ambiguity and may set limits for what leadership will be accepted (Crevani et al. Citation2010). As certain contexts may favor the endorsement of specific kinds of leaders (Grint Citation2005), context itself determines what type of leadership is considered appropriate; which in turn may generate discontent and even clashes between actors (Alvesson and Spicer Citation2011; Chiu, Balkundi, and Weinberg Citation2017).

As stated in the introduction, MMs occupy a particularly interesting and important position within the ongoing social and ambiguous process of leadership (Gleeson and Knights Citation2008; Harding et al. Citation2014). They often experience feeling trapped between the demands of top management and subordinates’ expectations of day-to-day routines, something that imposes additional workloads and stress on MMs (Conway and Monks Citation2011; Tyskbo Citation2020). Styhre and Josephson (Citation2006) even argued that middle managers are left with few opportunities for determining their work situation. It is a role that tends to be seen as bypassed by top management, while at the same time, subordinates have expectations regarding their leadership (Dopson and Stewart Citation1990; Redman et al. Citation1997). Thus, MMs often face numerous ambiguities regarding what role they play, how to build relationships with subordinates, and how to create trust. They must be able to adapt how they practice leadership and incorporate perspectives that sometimes might conflict with their own interests in order to be successful (Einola and Alvesson Citation2019). Therefore, MMs are placed in an ambiguous position, and stress that may subject them to a debilitating vulnerability, often leading to burnout (Gleeson and Knights Citation2008; Harding et al. Citation2014). Theoretically, MMs are also of research interest, since they can be constructed as both leaders and followers, as they are subordinates to higher-level managers (Alvesson Citation2019; Anicich and Hirsh Citation2017). However, researchers have tended to focus on MMs as leaders (Alvesson Citation2020). Furthermore, and despite their perceived importance and interesting position in leadership hierarchy—as they are trapped in constructions of both leaders and followers—relatively little attention has been paid to how such leadership processes unfold in practice (Alvesson Citation2019; Chiu et al. Citation2017). Leadership studies have generally been grounded in binaries, in which there are two kinds of people: leaders and followers (Collinson Citation2014), thus neglecting the idea of leadership as distributed and dependent on social processes. A recent exception is Gjerde and Alvesson (Citation2020) study on MMs’ roles and identities, described as being in “a sandwiched middle.” The authors highlight three main subject positions taken by MMs: performance drivers, impotents, and protectors, and they and encourage researchers to continue providing in-depth descriptions of how MMs deal with their roles as superiors, middlemen, and subordinates.

In the public sector, leadership and the role of MMs have been highlighted as critical to organizational success (Chen, Berman, and Wang Citation2017; Currie Citation2000). Although the role of MMs has been emphasized as particularly important, it has also been suggested as ambiguous and pressured (Gleeson and Knights Citation2008; Knies and Leisink Citation2014; Orazi et al. Citation2013). This is because public organizations are significantly impacted by complexity and institutional mechanisms (Blom et al. Citation2020). For example, they may be strongly impacted by the principle of equality and the public sector provision, relying more on egalitarian values compared to private organizations (Christensen et al. Citation2007). At the same time, many public organizations have also been pressured to work toward financial goals and profit-making (Ancarani et al. Citation2021; Papenfuß and Keppeler Citation2020). Public sector leaders participate in leadership training and education programs in which private industry sector leadership practices are treated as exemplary of all leadership work, which in turn mirrors a belief that, e.g., listed companies have a higher degree of leadership effectiveness, all things being equal. Under these conditions, when the “leadership map” poorly mirrors the “leadership territory,” leadership ideals are advocated and promoted that are potentially unattainable in a sector of the economy that responds to a broader set of demands and signals result in leadership practices that are, if not irrelevant, at least sub-optimal for public sector organization work (see, e.g., Orazi et al. Citation2013). Given these particularities and dualities, we would assume a pressured role for MMs being both highly responsible for ensuring that subordinates execute their operational activities effectively, and for making sure enough efforts are made in empowering subordinates and developing their skillsets. How and to what extent this is the case in practice is, however, not well understood, because comparatively few empirical studies have been conducted in the public sector (Kuipers et al. Citation2014; Van Wart Citation2013). Scholars have thus called for research into how MMs’ engagement in leadership unfolds in practice, especially in public organizations (Andersen et al. Citation2018; Azambuja and Islam Citation2019; Gjerde and Alvesson Citation2020, Orazi et al. Citation2013).

Using metaphors to understand the expectations and demands on middle managers

In this study, we respond to the aforementioned call by using metaphors, which is helpful when trying to navigate the process of social construction and to make sense of the expectations and demands put on MMs in leadership processes (Alvesson and Spicer Citation2011; Hernández-Amorós and Martínez Ruiz Citation2018; Ruth Citation2014). Metaphor analysis is particularly suitable for providing rich understandings of leadership processes (Amernic, Craig, and Tourish Citation2007), and Oberlechner and Mayer-Schoenberger (Citation2002) even go so far as to argue that metaphors are essential to our understanding of leadership. It has been argued that our ordinary conceptual system, in terms of what we think and act, is fundamentally metaphorical in nature (Lakoff and Johnson Citation1980). With regard to leadership, a metaphor stands as a symbol of understanding leadership by relating it to a figure of speech, thus having great explanatory power (Alvesson and Spicer Citation2011; Ruth Citation2014). Metaphors give meaning through metaphorical language and establish relationships of similarity (Althaus Citation2016). As metaphors create a leadership reality by defining the leader’s role and the context in which the leadership takes place (Oberlechner and Mayer-Schoenberger Citation2002), they provide a particularly well-suited perspective for helping us to understand and recognize leadership as a process of social construction, in which leaders, followers, and the surrounding context all interact and are inextricably linked (Amernic et al. Citation2007). Furthermore, using metaphors is especially useful when studying MMs in the public sector, as they are facing specific dualities and are expected to take on multiple roles (Gjerde and Alvesson Citation2020). In what follows, we briefly describe two specific leadership metaphors (i.e., the buddy metaphor and the commander metaphor) that have been widely used in the leadership literature and have emerged as useful for interpreting our case.

The buddy metaphor is used to describe a leader as someone who engages in a relationship with subordinates characterized by satisfaction and motivation. The aim of the leader’s point of view is to reduce conflict by acting like a “good guy” (Sveningsson and Blom Citation2011). Furthermore, leadership as a buddy often involves leading by informal means, an approach that seems to work because leaders and followers exist on a more equal level. The priority in this metaphor is to create a strong feeling of “we” and inclusiveness for employees (Perreault Citation2005), something which could be facilitated by sharing the same basic attitudes (Boyd and Taylor Citation1998) A potential problem in a buddy-like context is that it may become uncomfortable and stressful in situations that require the leader to make unpopular decisions (e.g., layoffs, replacements, decreased salaries, etc.), which may also compromise trust (Unsworth, Kragt, and Johnston-Billings Citation2018). The commander metaphor is used to describe the leader as someone who commands and forces other people to get things done in the quickest and most efficient way (Spicer Citation2011). This metaphor describes leadership as being autocratic (Krasikova, Gren, and LeBreton Citation2013), and evokes “unflinching strength, toughness and even brutality” (Ashcraft and Muhr Citation2018, 208). This type of leadership often clashes with the humanistic values that are emphasized in many of today’s organizations, in which leaders are required to enact other metaphors to capture socially sensitive issues. However, acting in line with the commander metaphor, with an emphasis on goal-focused and aggressive behavior, seems to be rewarded and even expected from good leaders (Chiu et al. Citation2017). The metaphor is also both present and quite effective in extreme contexts (Buchanan and Hällgren Citation2019), or in organizations with a high stress factor and a more “masculine” workplaces (Amernic et al. Citation2007; Spicer Citation2011).

Research setting and methods

PubLog (a pseudonym) is a Swedish public organization in the field of communications and logistics and is responsible for ensuring the fulfillment of universal postal service obligations. It has a unique supply chain and distribution network, offers services within communications, e-commerce, distribution, and logistics, and had net sales of EUR 3.9 billion in 2019. PubLog has recently implemented major changes in its operations due to efficiency requirements. The focus of this study is on the logistics hub in Sweden’s second city, which employs approximately 100 employees. While the ultimate responsibility for the production and performance of the hub lies with top managers, middle managers are largely responsible for the day-to-day operations performed by blue-collar workers.

PubLog was selected as a case study organization using a purposeful sampling technique and the logic of selecting an information-rich case (Lincoln and Guba Citation1985; Patton Citation2002). Two main reasons were used: first, because PubLog operates in a context where leadership and the role of middle managers have been highlighted as particularly critical and important for organizational success (Birasnav Citation2013; Ellinger and Ellinger Citation2014; Huo et al. Citation2015), and second because PubLog had only recently implemented major changes in its operations due to efficiency requirements. Middle managers were the ones closest to the employees on the ground and were thus described as, and expected to be, important actors in translating these new requirements into practice. Given this and in addition to how PubLog is considered a traditionally bureaucratic and hierarchical organization (Uhl-Bien and Marion Citation2009), we would expect middle managers to be placed in a somewhat pressured and ambiguous role: they are both responsible for ensuring that subordinates execute their operational activities effectively, and for making sure effort is made in developing their subordinates’ skillsets and talents. Taken together, we therefore expected this type of context to be ideal for observing the dynamics of how middle managers’ engagement in leadership processes unfolds in practice, and how they are managing expectations and demands from both top management and their subordinates, and some of its consequences—thus constituting a revelatory setting wherein the dynamics of interests would be more transparent (Patton Citation2002; Yin Citation2003). In adopting purposeful sampling in order to generate theoretical insight, our final selection of this organization was highly motivated by the site access that was afforded to us. Thus, we followed the arguments of grounded theory regarding considerable exposure to the empirical context, or the subject area being researched (Strauss and Corbin Citation1998; Suddaby Citation2006). Basing case selection on the potential to provide an understanding of leadership processes as socially-, relationally-, and contextually embedded, is further supported by various leadership scholars (e.g., Blom and Alvesson Citation2014; Alvesson and Spicer Citation2011; Fairhurst Citation2008), highlighting the difficulty of gaining access to organizations for research purposes (Alvesson and Deetz Citation2000).

The focus of this study is on middle managers and aims to provide a deeper understanding of how leadership unfolds in practice, especially when recognizing the MM as both a leader and a follower. Thus, a qualitative in-depth case study was found to be appropriate (Yin Citation2003). Qualitative data collection methods, such as interviews and observations, are especially relevant when the aim is to understand leadership in depth and as a complex social phenomenon (Alvesson Citation2019). We draw on arguments of empirical data always being interpretations of the phenomenon studied (Alvesson and Sköldberg Citation2018; Steier Citation1991). In line with the social constructionist view of leadership and our abductive interpretative analytical approach (described in detail below), we do not attempt to produce generalizable findings or claim our data is imaging some objective reality. Instead, we focus on the level of “meaning” (Alvesson and Sköldberg Citation2018) which is useful and relevant when the interest is in people’s constructions of leadership (Blom and Alvesson Citation2014). This choice of method complements the quantitative methods often adopted in studies on leadership in the public sector (Meier and O’Toole Citation2011; Vogel and Jacobsen Citation2021), and in doing so, also responds to calls for more qualitative in-depth studies (e.g., Andersen et al. Citation2018; Orazi et al. Citation2013).

Data collection

As suggested by Silverman (Citation2011), we included different data collection methods, including observations, in-depth interviews, and documents. One limitation of interviews is that they only include interviewees’ interpretations or accounts, so we relied heavily on observations to obtain a more holistic understanding of how the leadership process unfolds in practice (Watson Citation2011). Thus, by combining interviews and observations we were able to capture both the sayings and the doings/actions of leadership (Kärreman and Alvesson Citation2001; Sveningsson and Larsson Citation2006). During a period of five weeks, we shadowed top managers, MMs, and subordinates on numerous occasions and engaged with them in numerous informal conversations, which provided us with an understanding of the workplace and the interactions between leaders, followers, and the context. When taking notes, we divided our notebook into three columns: i.e., the first for time and actor, the second for notes, and the third for any immediate thoughts. Close to the end of each day, we reread the daily notes and expanded them with some additional comments and notes. We wrote memos about our impressions, and ideas as to how we could make sense of and interpret what we had observed. Doing observations also means talking to participants (Green and Thorogood Citation2013), and we thus participated in numerous ethnographic conversations (Emerson, Fretz, and Shaw Citation2011). These talks are similar to what Barley and Kunda (Citation2001) call “real-time interviewing,” and were often directly related to the current situation, and involved participants explaining what they were doing and us asking them what they were doing and why. They were spontaneous, took place wherever and whenever possible—for example, in seminar rooms, locker rooms, and in the canteen—and covered both general and emerging topics during work shifts. In some instances, we refer directly to our observations in the findings section, but in general these were broadly confirmed by the impressions we obtained from the interviews. We conducted 18 in-depth interviews (2 top managers, 12 middle managers, and 4 subordinates); a figure and distribution within the norm for workplace studies and large enough to reach data saturation and potential variability in qualitative research (Guest, Namey, and Chen Citation2020; Saunders and Townsend Citation2016).

Interviews were semi-structured and open-ended (Silverman Citation2011) in order not to steer the interviews, but rather allow interviewees to talk freely about their work. One limitation of leadership research is the reliance on a single perspective; for example, on managers or subordinates (Alvesson Citation2019), which falls short of providing an encompassing understanding of how leadership as a social process unfolds in practice. To mitigate this and to incorporate multiple perspectives, we interviewed top managers, MMs, and subordinates. As interviewees always hold the promise of new issues being addressed or surfacing, it is important to use the opportunity to ask the interviewee if he or she has other persons (colleagues, managers, etc.) that may be informed about these new issues. Thus, in addition to recruiting interviewees through “purposeful sampling,” where people are selected based on their knowledge and position (Patton Citation2002), and in order to optimize the ability to learn from specific cases and their conditions, we also used what is called a “snowballing” interviewee selection design, where one interviewee leads researchers to the next (Ekman Citation2015). Thus, the rationale for recruiting interviewees may not necessarily have led us to construct a fully representative account of leadership in PubLog, but it has enabled us to let many voices be heard, thus teasing out the “polyphony” of the organization (Justesen and Mik-Meyer Citation2012). The interviews lasted between 60 and 90 minutes, were conducted face-to-face, and were all recorded and transcribed verbatim. Interviews were loosely organized around an interview schedule, and questions were broad and addressed, for example, the interviewees’ self-images, views on leadership, organizational and work contexts, and relationships with senior employees, colleagues, and subordinates (for more details on the interview questions, see Appendix A). We complemented the observations and interviews with the collection of various organizational documents, such as brochures, financial reports, lists of role descriptions, and documents related to prescribed leadership behaviors.

Before we describe our data analysis, it is important to clarify and further discuss our data sources. The focus of our attention was the role of MMs, and therefore most data collection was conducted with them. However, interviews and observations were also conducted with top managers and subordinates to obtain a range of perspectives, but also because this multi-actor approach (Eisenhardt Citation1989) resonates with the view of leadership adopted in this article; i.e., as a socially constructed phenomenon that is highly relational and distributed among various actors, and with the aim of this article to understand leadership in-depth (see Alvesson Citation2019). However, we acknowledge one potential limitation of this approach is the risk of detracting from the main actors; i.e., MMs, and emphasizing the perspective of others too heavily. With this in mind, we recognize that our distribution of the interviewees and observations may be viewed as skewed, and we suggest future research should consider this when deciding upon data sources and study designs.

Data analysis

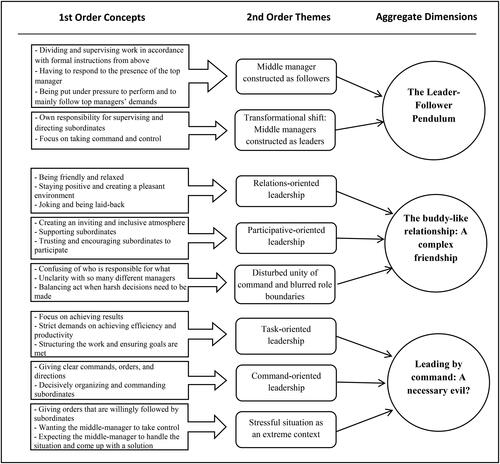

We analyzed the data using an abductive interpretative analytical approach (see Timmermans and Tavory Citation2012) with a focus on observing patterns of the leadership process and getting a good feeling for context and relations. The purpose of this approach was to get a deeper and grounded sense of the meaning of the phenomenon; in our case how MMs, in the public sector context, are managing expectations and demands from both top management and subordinates, and some of its consequences. To achieve this, we followed a three-step process similar to that described in the literature (Gioia, Corley, and Hamilton Citation2013), which is illustrated by our data structure as seen in . The first step in our data analysis consisted of an in-depth analysis of the raw data (i.e., observational notes, interview transcripts and organizational documents), during which we read each note, interview, and document several times, highlighting phrases and passages related to experiences of how leadership processes unfold in practice, in particular the role of MMs within these processes. By using an open coding logic in this way, we could code the common words, terms, phrases, and labels mentioned by respondents and used in documents into first-order concepts. These first-order concepts are in-vivo codes and largely reflect the views of the respondents in their own words (Locke Citation2011). The strength of this approach is that the starting point is within the strategic issues and managerial tensions as they are perceived in practice, rather than those stemming from theory. We also constructed comparative tables for each occupational group in which we coded data for how they described the workplace, the leadership processes, and the role of MMs within these processes, at PubLog. We looked for similarities as well as differences and were surprised by the high level of common views on leadership processes. The second step of the analysis consisted of further examining first-order concepts to detect potential links and patterns among them. By using axial coding and circulating back and forth between the data and the literature (Strauss and Corbin Citation1998), we could cluster the first-order concepts in relation to their foci, and subsequently reduce them to second-order themes. These themes relate to leaders and followers as they emerge as an outcome of enacted leadership processes, and the different orientations through which the leadership process unfolds in practice. Axial coding was complete when we were satisfied with the themes and theoretical saturation had been achieved (i.e., the data structure is stable and no new, novel interpretations emerge). The third step consisted of a frequent iteration between data and theory which allowed us to generate three aggregate dimensions (i.e., the leader–follower pendulum, the buddy-like relationship, and leading by command) that represented a higher level of abstraction. Here, we used insights from the literature on leadership as a process of social construction (e.g., Fairhurst and Grant Citation2010; DeRue and Ashford Citation2010), and leadership metaphors (e.g., Alvesson and Spicer Citation2011; Ruth Citation2014) to form these more theoretically rooted dimensions. For example, the majority of interviewees told stories and made statements that indicated that they regarded their role and the leadership processes at PubLog, to include both authority-based and supportive activities. From these grounded insights, and after consulting the literature, we understood that the content of the interviews was closely linked to the buddy metaphor and the commander metaphor, as they exist in leadership literature. Thus, the literature helped us make sense of our empirical material and to compare it with existing insights. To improve intra-rater reliability, we used a test-retest approach. The data was analyzed twice by the same researcher and re-sorted until there was complete agreement. The dimensions found here underpin our analysis of how MMs in the public sector are managing expectations and demands from both top management and subordinates, which reflects our transition from a lower to a higher level of abstraction.

Findings

The leader–follower pendulum

When exploring how MMs handle the complexities of managing expectations and demands from both top management and subordinates, it became evident that they move between being constructed as leaders and followers. This transformational shift in how the leadership process unfolds in practice is here labeled the leader–follower pendulum.

MMs generally described their work and their roles as producing high levels of stress and requiring the ability to efficiently plan and structure their work. These aspects were considered important in dividing the work sufficiently and in accordance with formal instructions from above. With imminent pressure coming from above to ensure that subordinates’ duties are performed on time, MMs often expressed during interviews that they also experienced their work to be stressful. This notion was further strengthened by observations we made in the mornings, during which MMs were highly stressed when printing out labels and calculating the number of pallets required for the current workday. It was mainly in the morning, before the subordinates had arrived at the workplace, and when having to respond to the presence of the top manager, that MMs’ experienced their work as stressful. One MM explained:

I must hurry to ensure that the workplace is well-prepared and well-structured before the subordinates arrive. My boss [top manager] expects me to take full responsibility for tasks being performed on time and for dividing the duties among the workers in a good way. He also demands open communication.

It was during a meeting, when my boss [top manager] made it clear to me that he expects us [middle managers] to take full responsibility for everything working as expected. After that meeting, I realized that I really had to follow his demands and that he was in fact dependent on me.

One of the most difficult issues for middle managers is related to their relationships with workers [subordinates]. It can be difficult for them to motivate workers and make them walk the extra mile that is needed in order to be successful. Results, organizational goals, and productivity are the most important aspects, and it can be difficult for them [middle managers] when these aspects involve making unpopular decisions, but feelings and emotions need to come secondary.

However, when preparations for the day’s working session were complete, and subordinates had arrived, MMs raised their specific goals and expectations they had on the subordinates regarding the current work shift. At this point, there is a transformation in how the leadership process unfolds in practice, as the leader and follower pendulum changes direction. Instead of being constructed as followers under the command of the top managers, MMs now become constructed as leaders in that they are responsible for supervising and directing subordinates. This indicates a transformational shift in the interpretation and meaning of what is played out in practice and relates to how today’s roles of actors are more complex and multidimensional, rather than merely defined with a predetermined and specific role. One MM described:

It’s clear that my role changes when workers arrive for the day and when the boss [top manager] is not here. I’m starting to focus more on taking commands and ensuring that they increase their productivity all the time.

It’s sometimes unclear which of the managers is responsible for what, and it has even happened that I have bypassed my manager and instead turned directly to the manager above [top manager].

The buddy-like relationship: a complex friendship

Understanding the culture at PubLog becomes important as different cultures may shape what kind of leadership is thought to be appropriate. Males dominated the workforce, and interviewees described the culture as being characterized by competition, tough verbal language, vulgar jokes, and aggressive body language; something that is particularly in line with what is broadly assumed to be typical for males. In fact, interviewees generally used the word “masculine” to summarize the workplace at PubLog. However, at the same time, the culture was described as if there existed a sense of “we,” through which employees behaved as friends and genuinely supported each other. Thus, despite being considered a traditional masculine workplace, leadership at PubLog was also described by both the MMs and subordinates as being friendly and supportive. Despite the knowledge that we should be prudent in gender-labeling leadership as “masculine” or “feminine,” this more relationship-orientated leadership, recognizing the importance of support and feelings, could still be illustrative of more traditional feminine values. However, it could also be connected to the broader context, where in Sweden and in the public sector, more relationship-oriented and participative-oriented leadership are seen as both necessary and acceptable. One MM explained his friendly leadership approach:

I try to stay positive and relaxed because I think this will make the workers happy. I try to make us all part of one and the same team, with the work environment being inviting and inclusive.

I usually don’t only talk about work-related things, but I also try to bring up things related to outside the workplace, which I think helps create a friendly and personal relationship with my workers.

It’s not particularly hierarchical here. And I would say that we are pretty much on the same level, where I can joke with my boss and so on. I try to make him happy and relaxed, and hope that he finds me a support.

Importantly, the buddy-like relationship was not all good and fluffy but also had a “dark side.” For example, followers described the organization, specifically the order of command, as messy: “there are so many managers on different levels and several business areas that it is sometimes difficult to get a clear overview” (follower). Another follower raised similar critical concerns regarding the confusion of who is responsible for what, and who has the highest responsibility:

It’s not always clear for me who I should turn to with a problem. It has happened that I chose to go directly to the real supervisor [top manager].

MMs pointed to additional aspects related to the dark side of the buddy-like relationship, such as when they had to deal with subordinates not performing to expected standards. During these situations, MMs must engage in a balancing act: on the one hand, relating to and acting more in line with the expectations and demands of top managers, and on the other hand acting like an ombudsman by maintaining a friendly relationship and protecting the interests of subordinates. Thus, when the subordinates are not doing their work or are not delivering to what is expected, it creates ambiguities for MMs, who run the risk disturbing the friendly relationship when forced to reprimand them. Thus, one aspect of the dark side of the buddy-like relationship concerns the difficulty in switching from a buddy role when unpopular decisions must be made, such as job cuts or during tough conversations. This difficulty was expressed by MMs as having “to take on an authoritarian and controlling role, especially when the schedule is under time pressure” (middle manager). Followers also alluded to this by describing how leadership unfolds when it gets stressful during the “peak” part of the workday: “I know we’re friends, but it feels strange when my boss starts yelling at us and just commands us what to do.” Here, we see that trust becomes compromised, and that followers expect the leader to act in a friendly manner, which is contrary to what is considered necessary in stressful situations or when harsh decisions need to be made.

Leading by command: a necessary evil?

A more task-oriented and command-oriented leadership is often expected in organizations built on cultures of efficiency, something that public sector work, like that performed at PubLog, is increasingly seen as part of. As touched upon in the leader-follower pendulum section, this task and command-oriented leadership was especially evident and required during stressful work situations, like when a high workload was required in a short period of time. MMs explained that during these stressful situations, as in the following words of the top manager, “achieving results is the most important thing” (middle manager), which echoed as a constant reminder in the back of their heads. Thus, these changes in the social context shaped how the leadership process unfolded in practice, with a greater emphasis being placed on MMs to drive performance: “we really need to focus on structuring the work and ensuring that goals are met” (middle manager). As the context changed to become more serious, with strict demands on achieving efficiency and productivity, the way MMs engaged in leadership also changed. Now, they had to give clear commands, orders, and directions, rather than being allowed to act as laid-back leaders nestled in friendly relationships. One MM described this as follows:

When it starts to get hot, we have to focus on our goals…There is little room for jokes and laughter because we are expected to take full control of the situation. We must decisively organize and command workers.

Leading by command was also noticed by the followers, especially during stressful situations: “they are giving us orders on what to do, and I just follow these and listen to what they tell us” (follower). Followers’ experiences of these situations point to how they are given orders and directions, as well as how the leadership involves a centralization of the decision-making processes. Instead of being involved in how decisions are made, followers simply execute decisions already made. Interestingly, followers do not unequivocally seem to experience this commanding leadership as something negative, and they are not just being exposed to it. Rather, they seem to expect this type of leadership and are themselves contributing to this situation: “I want him to take control, that he is determined and takes all the responsibility” (follower). Thus, followers are dependent on instructions from MMs, indicating that followers even prefer MMs to engage in this stricter and more commanding leadership style. One follower described this as follows:

When it gets stressful or when something might go wrong, I expect him to come up with good solutions.

Discussion

We found that MMs were trapped in the way they moved between being constructed as a “leader” and “follower” along what we call a “leader–follower pendulum.” Adding to this was how MMs were engaged in enacting two different leadership metaphors; that is, the “buddy” and the “commander.” These aspects jointly contribute to a complex and ambiguous situation for MMs, which in turn gives rise to the difficulties of alienation and the constant strive to fit in. We refer this to as the “karma chameleon.”

Studying the “sandwiched middle” (Bryman and Lilley Citation2009), it is no surprise that MMs were trapped between expectations from top management and subordinates. However, we move beyond the question of whether or not MMs are trapped, to shed light on how this unfolds in practice, and with what consequences. In doing so, we respond to calls for more in-depth qualitative studies of how MMs engage in leadership processes (Azambuja and Islam Citation2019; Gjerde and Alvesson Citation2020), and for more leadership studies in the public sector context in particular (e.g., Andersen et al. Citation2018; Orazi et al. Citation2013). More specifically, we provide empirical support for conceptual arguments regarding how MMs can be constructed as both leaders and followers (e.g., Alvesson Citation2019; Anicich and Hirsh Citation2017). While much of mainstream research has been grounded in binaries in which there are two kinds of people: leaders and followers (Alvesson Citation2020; Collinson Citation2014), we provide a deeper understanding of MMs’ “double relationality” (Gjerde and Alvesson Citation2020). Navigating the middle includes, as our findings show, a balancing act of responding to organizational expectations (i.e., productivity, efficiency, and staffing) from top management, while at the same time directing and identifying with followers based on emotions and feelings. Aspects related to organizational expectations support arguments made in recent research which hold that top management requires MMs to act as performance drivers (e.g., Gjerde and Alvesson Citation2020). These findings also extend arguments made in previous research which hold that public sector organizations are increasingly pressured to meet financial goals and to focus on efficiency (Ancarani et al. Citation2021; Blom et al. Citation2020; Christensen et al. Citation2007; Papenfuß and Keppeler Citation2020), by showing how this unfolds in practice and shapes MMs’ day-to-day activities. It is also interesting to discuss how this finding relates to the specific public sector context and what type of leadership is often expected in this context. Previous research has reported that there is a growing pressure on public sector actors, such as MMs, to act as visionaries and as empowering leaders who have the capacity to involve followers and to engage coworkers (Ancarani et al. Citation2021; Orazi et al. Citation2013). However, our findings indicate that despite such expectations, norms and expectations exert pressures on middle managers (and certainly other actors as well) in the public sector to act in line with what can traditionally be considered ideal or proper leadership, the structure of public organizations and much of their daily problems and work activities do not seem to allow much space for it. Instead, the social construction of leadership in the specific context means that more space seems to be given to, and more emphasis is placed on, what could be described as goal- or task-oriented leadership. Additional aspects related to leading, and identifying with followers based on emotions and feelings support arguments made in previous research which hold that MMs are protectors with a need to establish strong relationships with subordinates (Gjerde and Alvesson Citation2020; Kempster and Gregory Citation2017), and that more relationship-oriented and participative-oriented leadership is aligned with values held in the public sector (Ancarani et al. Citation2021; Andersen et al. Citation2018; Holmberg and Åkerblom Citation2001).

In addition, our study adds important nuances to existing arguments. The findings show how MMs’ movement between being constructed as leaders and followers in a leader–follower pendulum does not occur at random, but rather in relation to the work context and the situation at hand. In our study, it was above all the timing of the work activities and the presence of leadership actors that influenced MMs’ movement within the leader-follower pendulum. In the morning during preparatory activities and when the top manager was physically present, MMs were constructed mainly as followers; while later, when actual core work activities were to be carried out and subordinates were in place, the MMs were constructed as leaders. This suggests that MMs’ “double relationality” involves a contingency component, with different work contexts and situations eliciting the emergence of different movements between being constructed as leaders and followers (Virtaharju and Liiri Citation2019). Thus, we enhance our theoretical understanding of how MMs navigate the middle and why they move along the leader–follower pendulum in specific ways.

Our findings also show how, despite PubLog being characterized by repetitive work with a focus on production and efficiency, and with both MMs and subordinates even using the word “masculine” to summarize the culture, thus being expected to embrace a more task-oriented and command-oriented leadership (Cherneski Citation2020; Due Billing and Alvesson Citation2000), MMs enacted two different leadership metaphors, that of the buddy and the commander. Through the enactment of these different leadership metaphors, MMs were taking on different and sometimes quite contrasting roles, which also resulted in the leadership process unfolding at PubLog as scattered and nuanced. This is interesting, because previous research has pointed to leadership as something unified and stable, and what kind of leadership is thought to be appropriate is largely shaped by workplace culture (e.g., Chen and Meindl Citation1991; Sveningsson and Blom Citation2011). Many previous studies have described how MMs enact rather stable leadership roles (Gjerde and Alvesson Citation2020), whereas in our study MMs constantly moved between roles and even enacted them simultaneously. MMs did not identify themselves as either a buddy, or a commander, but enacted both roles to various degrees at different times. While existing arguments in the literature on how MMs move between different positions seem to emphasize that it is up to the manager him/herself to freely choose between these positions (Harding et al. Citation2014), we show that this movement is largely shaped by followers and the context. For example, the buddy-like relationship was strengthened and shaped by followers, as well as by situations with lower stress levels. In contrast to what was expected, more commanding leadership was also sought for and stimulated by followers who, during stressful situations, searched for orders and commands. Thus, what kind of leadership is enacted cannot be solely attributed to the leader, but largely depends on the dynamics and interactions between leaders, followers, and the context (Crevani et al. Citation2010; Virtaharju and Liiri Citation2019). Thus, our findings illustrate the shortcomings of traditional views of leadership with descriptions of heroic leaders exercising far-reaching influences, when trying to understand MMs, and instead emphasize the importance of considering the relational and processual aspects of leadership (Alvesson and Spicer Citation2011; Fairhurst and Grant Citation2010).

Importantly, we add to the current understanding of how MMs are trapped between expectations and demands from both top management and subordinates by going beyond only stating that they are trapped and exploring how this occurs in practice, and also by theorizing some of its consequences. More specifically, the movement between being constructed as a leader and a follower together with the enactment of the two different leadership metaphors jointly contributed to a complex and ambiguous situation for MMs. We metaphorically refer to this as “karma chameleon,” as it meant alienation difficulties and a constant strive to fit in. First, MMs’ movement between being constructed as leaders and followers was not straightforward and clear-cut but caused ambiguities in the way they were torn between the demands of following and leading, and in the way their behaviors were viewed as inconsistent due to lack of clarity around who was really in charge (Sims Citation2003). Second, the enactment of the two different leadership metaphors, that is the buddy and the commander, not only resulted in a scattered and nuanced leadership process, but also in making a situation filled with tension and threat (Lutgen-Sandvik Citation2008). It “prompt[ed] feelings of confusion, contradiction and self-doubt, which in turn tend to lead to examination of the self” (Brown Citation2015, p. 25). MMs were again torn between their own expectations as followers, as well as the context of how to practice leadership. This contrasts with previous research that, when stressing the importance of MMs to be flexible and adaptive, also tends to assume that the incorporation of different perspectives is a straightforward and unambiguous process (see Einola and Alvesson Citation2019). Based on these findings and our theorizing, we suggest that a chameleon metaphor could be useful in understanding leadership complexities and ambiguities among MMs. This metaphor invites us to see different behaviors, such as fast adaption, awareness, and sensemaking. Similar to the chameleon’s ability to adapt to various situations and environments in order to survive, the MM shifts in behavior, whether he or she is exposed by the top or the bottom, in a way to “survive” in the organizational context. The dark side of leadership as a chameleon is that continuous adaptation to surroundings may cause stress and create a sense of confusion among the MMs themselves and among subordinates, in not understanding their roles or who the leader is in any specific situation. More specifically, if a middle management position is associated with a ceaseless adaptation to situations that demand a different repertoire of managerial skills, this puts pressure on the individual in this leadership role. Furthermore, in public sector organizations, which are, by definition, responsive to policy and political agendas; i.e., issues that managers in privately owned companies only need to consider to a lower extent, the risk that middle managers are exposed to additional demands and are expected to pay attention to an even broader scope of issues further pronounces this concern. As the capacity and willingness to constantly modify their behavior to suit different contexts and situations naturally differs between individuals, it may be that highly qualified and motivated would-be leaders and candidates for leadership positions are reluctant to assume such a role. That is, without any clear guidance from top management or professional norms and rules on how to cope with the challenges discussed in this study, it may be that certain qualified leadership candidates are unwilling to embark on a leadership career. Such a waste of leadership talent risk reduces economic and social welfare if top management inadvertently assume that it is attractive to work within the swings of the leader–follower pendulum.

Finally, our findings show that, despite good intentions from MMs to act as a buddy, the enactment of this metaphor nevertheless resulted in ambiguities and tensions. For example, and as mentioned above, when MMs acted as a buddy on a more equal level, it blurred the boundaries for subordinates, thus weakening their roles as leaders, and resulting in difficulties related to legitimacy and respect. The mainstream leadership literature is often based on the assumption that certain leadership styles (e.g., transformational, authentic, servant, and situational) are inherently “good” with positive consequences, and that these styles are followed by “good” responses from followers (Alvesson and Kärreman Citation2016; Kaiser and Craig Citation2014). In contrast, our findings suggest that what appears to be very good leadership and a well-functioning team (Einola and Alvesson Citation2019) can unfold very differently when considering consequences and studying leadership qualitatively in depth.

Contributions, limitations, and future research

Through our findings, we make several important contributions to the literature, as well as to practice. First, we contribute to the literature on leadership and the role of MMs (e.g., Einola and Alvesson Citation2019; Dopson and Stewart Citation1990; Gleeson and Knights Citation2008; Harding et al. Citation2014; Kempster and Gregory Citation2017; Newell and Dopson Citation1996), by analyzing how MMs are simultaneously constructed as both leaders and followers in their domain of day-to-day work. Navigating the middle required a balancing act to respond to and to follow organizational expectations from top management, and at the same time to direct and identify with followers based on strong and intimate relationships. Thus, while much of the mainstream research has been premised on leadership work being structured into binary and mutually exclusive categories in which there are two kinds of people, leaders and followers (Alvesson Citation2019; Collinson Citation2014), we provide a deeper understanding of MMs’ “double relationality” (Gjerde and Alvesson Citation2020). We advance current understanding by showing how MMs’ movements between being constructed as leaders and followers do not occur at random but involve a contingency component. Second, we contribute to the leadership literature using metaphor analysis (e.g., Alvesson and Spicer Citation2011; Hernández-Amorós and Martínez Ruiz Citation2018; Oberlechner and Mayer-Schoenberger Citation2002; Ruth Citation2014), by suggesting an alternative leadership metaphor; the chameleon. This metaphor underlines how middle managers deal with the complex and oftentimes ambiguous situations wherein they need to move back and forth between being leaders of and “buddies” to their subordinates, while at the same time acting on decisions from top managers. In doing this, we advance knowledge of how MMs are engaged in leadership processes and how this engagement unfolds in different contexts, especially in a public sector setting. By designing and conducting an in-depth and contextualized study, we present empirical material that, in contrast to much of the extant research, strongly suggests that general assumptions that certain leadership styles (e.g., transformational, authentic, servant, and situational) are inherently “good” or “effective,” and therefore have positive consequences (Alvesson and Kärreman Citation2016; Kaiser and Craig Citation2014), do not always comply with the “reality” of how leadership work occurs and unfolds in practice. Instead, we add to the few existing studies that show how what appears to be very good leadership and a well-functioning team (Einola and Alvesson Citation2019) can in fact develop very differently when shedding light on the ambiguities and complexities of day-to-day work, and when studying leadership in depth and qualitatively. In making these contributions, the study answers the call for more qualitative studies as to how MMs engage in leadership processes (Azambuja and Islam Citation2019; Gjerde and Alvesson Citation2020), and the call for more leadership studies in the public sector context in particular (Andersen et al. Citation2018; Orazi et al. Citation2013).

The findings from our study also have important practical implications that are social relevant to organizational issues (Grint and Jackson Citation2010). To increase the efficacy of people at work, organizations need to carefully understand the vulnerable positions of MMs. By being aware of the leader–follower pendulum and the enactment of leadership metaphors, organizations and high-level managers can avoid stopping at and relying on formal descriptions of how MMs’ leadership work takes place, and instead start considering in-depth investigations of day-to-day activities. This will help organizations to move beyond the naïve views on “good” leadership and the associated unidirectional positive consequences, instead acknowledging that what may appear to be good leadership and a well-functioning team can in fact unfold very differently in practice.

This study is also tied to certain boundary conditions; i.e., the situations to which the insights are likely to be theoretically generalizable and have certain limitations, which together offer opportunities for future research. An important contextual factor that might have an impact on whether, and how, the categories and their relationships observed in this study will occur concerns the empirical research context. Public organizations in many countries and different public sector contexts are generally thought of as converging or as becoming similar, due to global public management paradigms (e.g., NPM, NPG). However, different organizational and cultural contexts can still imply variations in how leadership and the role of MMs are played out, which becomes important to keep in mind when comparing different countries and or institutions (see Kuhlmann and Wollmann Citation2019). For example, the field of communications and logistics, is, on the whole, frequently described, both in the literature and by the respondents, as production-focused and bureaucratic, thus stressing efficiency and productivity concerns and possibly constraining leadership work with rigid rules and regulations. We would, perhaps, expect leadership and the role of MMs to unfold somewhat differently in other public sector contexts; e.g., knowledge-intensive organizations or those with an innovation focus or a professional development focus, which are characterized by different leadership ideals and processes (e.g., a focus on learning, empowerment and involvement) (Uhl-Bien, Marion, and McKelvey Citation2007). In addition, Swedish culture is often regarded as egalitarian and collectivist (at least in the workplace) (see Holmberg and Åkerblom Citation2001), and contexts based more on elitism would perhaps facilitate unequal power relations (Kabanoff, Waldersee, and Cohen Citation1995), thus having a potential impact on how leadership and the role of MMs play out in practice. Furthermore, countries differ in terms of what educational background is expected for public servants; e.g., a more general or specialized education and training (Kuhlmann and Wollmann Citation2019), which are aspects that may affect the possibilities that our results are transferable to other contexts.

There are other important limitations to this study which future research could address. We adopted a single case study with our empirical data consisting of a limited number of observations, interviews, and organizational documentation. While this enabled an in-depth understanding, it only reveals certain aspects of how leadership unfolds in practice. Our findings are therefore exploratory, and we encourage future research to take our insights into consideration and investigate the leadership complexities of being trapped on a larger scale and in different contexts. For example, while we only found support in our data that the buddy-like behavior was related to the relationship between MMs and subordinates, it is likely that this could also be the case for the relationship between MMs and top managers, something on which we urge future studies to focus.

Conflict of interest

We have no conflict of interest to declare.

Data availability statement

Due to the nature of this research, participants of this study did not agree for their data to be shared publicly, so supporting data is not available.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Daniel Tyskbo

Daniel Tyskbo is an Assistant Professor at Halmstad University, Sweden. His research interests include HRM, talent management, public management, public administration, new technology, complex and advanced healthcare practices, and the implementation of information-driven care.

Alexander Styhre

Alexander Styhre, PhD, is chair of management and organization, Dept. of Business Administration, School of Business, Economics and Law, University of Gothenburg. His current research examines video game production, urban development and affordable housing policy, and institutional changes in the economy.

References

- Althaus, C. 2016. “The Administrative Sherpa and the Journey of Public Service Leadership.” Administration & Society 48(4):395–420. doi: 10.1177/0095399713498747.

- Alvesson, M. and A. Spicer. (eds.) 2011. Metaphors we Lead by: Understanding Leadership in the Real World. London: Routledge.

- Alvesson, M. 2019. “Waiting for Godot: Eight Major Problems in the Odd Field of Leadership Studies.” Leadership 15(1):27–43. doi: 10.1177/1742715017736707.

- Alvesson, M. 2020. “Upbeat Leadership: A Recipe for–or against–“Successful” Leadership Studies.” The Leadership Quarterly 31(6):101439. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2020.101439.

- Alvesson, M., and S. Deetz. 2000. Doing Critical Management Research. London: Sage Publications.

- Alvesson, M., and D. Kärreman. 2016. “Intellectual Failure and Ideological Success in Organization Studies: The Case of Transformational Leadership.” Journal of Management Inquiry 25(2):139–52. doi: 10.1177/1056492615589974.

- Alvesson, M., and K. Sköldberg. 2018. Reflexive Methodology: New Vistas for Qualitative Research, 2nd ed., Sage: London.

- Amernic, J., R. Craig, and D. Tourish. 2007. “The Transformational Leader as Pedagogue, Physician, Architect, Commander, and Saint: Five Root Metaphors in Jack Welch’s Letters to Stockholders of General Electric.” Human Relations 60(12):1839–72. doi: 10.1177/0018726707084916.

- Ancarani, A., F. Arcidiacono, C. D. Mauro, and M. D. Giammanco. 2021. “Promoting Work Engagement in Public Administrations: The Role of Middle Managers’ Leadership.” Public Management Review 23(8):1234–63. doi: 10.1080/14719037.2020.1763072.

- Andersen, L. B., B. Bjørnholt, L. L. Bro, and C. Holm-Petersen. 2018. “Leadership and Motivation: A Qualitative Study of Transformational Leadership and Public Service Motivation.” International Review of Administrative Sciences 84(4):675–91. doi: 10.1177/0020852316654747.

- Anicich, E. M, and J. B. Hirsh. 2017. “The Psychology of Middle Power: Vertical Code-Switching, Role Conflict, and Behavioral Inhibition.” Academy of Management Review 42(4):659–82. doi: 10.5465/amr.2016.0002.

- Ashcraft, K. L, and S. L. Muhr. 2018. “Coding Military Command as a Promiscuous Practice? Unsettling the Gender Binaries of Leadership Metaphors.” Human Relations 71(2):206–28. doi: 10.1177/0018726717709080.

- Azambuja, R, and G. Islam. 2019. “Working at the Boundaries: Middle Managerial Work as a Source of Emancipation and Alienation.” Human Relations 72(3):534–64. doi: 10.1177/0018726718785669.

- Barley, S. R., and G. Kunda. 2001. “Bringing Work Back In.” Organization Science 12(1):76–95. doi: 10.1287/orsc.12.1.76.10122.

- Bicchieri, C. 2017. Norms in the Wild: How to Diagnose, Measure, and Change Social Norms. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Birasnav, M. 2013. “Implementation of Supply Chain Management Practices: The Role of Transformational Leadership.” Global Business Review 14(2):329–42. doi: 10.1177/0972150913477525.

- Blom, M., and M. Alvesson. 2014. “Leadership On Demand: Followers as Initiators and Inhibitors of Managerial Leadership.” Scandinavian Journal of Management 30(3):344–57. doi: 10.1016/j.scaman.2013.10.006.

- Blom, R., P. M. Kruyen, B. I. Van der Heijden, and S. Van Thiel. 2020. “One HRM Fits All? A Meta-Analysis of the Effects of HRM Practices in the Public, Semipublic, and Private Sector.” Review of Public Personnel Administration 40(1):3–35. doi: 10.1177/0734371X18773492.

- Boyd, N. G., and R. R. Taylor. 1998. “A Developmental Approach to the Examination of Friendship in Leader-Follower Relationships.” The Leadership Quarterly 9(1):1–25. doi: 10.1016/S1048-9843(98)90040-6.

- Brown, A. D. 2015. “Identities and Identity Work in Organizations.” International Journal of Management Reviews 17(1):20–40. doi: 10.1111/ijmr.12035.

- Bryman, A., and S. Lilley. 2009. “Leadership Researchers on Leadership in Higher Education.” Leadership 5(3):331–46. doi: 10.1177/1742715009337764.

- Buchanan, D. A., and M. Hällgren. 2019. “Surviving a Zombie Apocalypse:Leadership Configurations in Extreme Contexts.” Management Learning 50(2):152–70. doi: 10.1177/1350507618801708.

- Chen,C. A., E. M. Berman, and C. Y. Wang. 2017. “Middle Managers’ Upward Roles in the Public Sector.” Administration & Society 49(5):700–29. doi: 10.1177/0095399714546326.

- Chen, C. C., and J. R. Meindl. 1991. “The Construction of Leadership Images in the Popular Press: The Case of Donald Burr and People Express.” Administrative Science Quarterly 36(4):521–51. doi: 10.2307/2393273.

- Cherneski, J. 2020. “Evidence‐Loving Rock Star Chief Medical Officers: Female Leadership Amidst COVID‐19 in Canada.Gender.” Gender, Work & Organization 27(5):900–13. doi: 10.1111/gwao.12494.

- Chiu, C. Y. C., P. Balkundi, and F. J. Weinberg. 2017. “When Managers Become Leaders: The Role of Manager Network Centralities, Social Power, and Followers' Perception of Leadership.” The Leadership Quarterly 28(2):334–48. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2016.05.004.

- Christensen, T., P. Laegreid, P. G. Roness, and K. A. Røvik. 2007. Organization Theory and The Public Sector: Instrument, Culture and Myth. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Collinson, D. 2014. “Dichotomies, Dialectics and Dilemmas: New Directions for Critical Leadership Studies?” Leadership 10(1):36–55. doi: 10.1177/1742715013510807.

- Conway, E, and K. Monks. 2011. “Change from below: The Role of Middle Managers in Mediating Paradoxical Change.” Human Resource Management Journal 21(2):190–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-8583.2010.00135.x.

- Crevani, L., M. Lindgren, and J. Packendorff. 2010. “Leadership, Not Leaders: On the Study of Leadership as Practices and Interactions.” Scandinavian Journal of Management 26(1):77–86. doi: 10.1016/j.scaman.2009.12.003.

- Currie, G. 2000. “The Public Manager in 2010: The Role of Middle Managers in Strategic Change in the Public Sector.” Public Money and Management 20(1):17–22. doi: 10.1111/1467-9302.00197.

- DeRue, D. S., and S. J. Ashford. 2010. “Who Will Lead and Who Will Follow? A Social Process of Leadership Identity Construction in Organizations.” Academy of Management Review 35(4):627–47.

- Dopson, S., and R. Stewart. 1990. “What is Happening to Middle Management?” British Journal of Management 1(1):3–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8551.1990.tb00151.x.

- Due Billing, Y. and M. Alvesson. 2000. “Questioning the Notion of Feminine Leadership: A Critical Perspective on the Gender Labelling of Leadership.” Gender, Work & Organization 7(3):144–57. doi: 10.1111/1468-0432.00103.

- Eames, T. 2020. The Story of… ‘Karma Chameleon’ by Culture Club. Smooth Radio. March 16. https://www.smoothradio.com/features/the-story-of/culture-club-karma-chameleon-meaning-lyrics-facts/

- Einola, K., and M. Alvesson. 2019. “When ‘Good’ Leadership Backfires: Dynamics of the Leader/Follower Relation.” Organization Studies doi: 10.1177/0170840619878472.

- Eisenhardt, K. M. 1989. “Building Theories from Case Study Research.” Academy of Management Review 14(4):532–50. doi: 10.2307/258557.

- Ekman, S. 2015. “Critical and Compassionate Interviewing: Asking Until It Makes Sense.” In E. Jeanes and T. Huzzard (Eds.), Critical Management Research: Reflections From the Field (pp. 119–34). London: SAGE.

- Ellinger, A. E, and A. D. Ellinger. 2014. “Leveraging Human Resource Development Expertise to Improve Supply Chain Managers’ Skills and Competencies.” European Journal of Training and Development 38(1/2):118–35.

- Emerson, R. M., R. I. Fretz, and L. L. Shaw. 2011. Writing Ethnographic Fieldnotes. 2nd ed., Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Fairhurst, G. T. 2008. “Discursive Leadership: A Communication Alternative to Leadership Psychology.” Management Communication Quarterly 21(4):510–21. doi: 10.1177/0893318907313714.

- Fairhurst, G. T. 2009. “Considering Context in Discursive Leadership Research.” Human Relations 62(11):1607–33. doi: 10.1177/0018726709346379.

- Fairhurst, G. T, and D. Grant. 2010. “The Social Construction of Leadership: A Sailing Guide.” Management Communication Quarterly 24(2):171–210. doi: 10.1177/0893318909359697.

- Gioia, D. A., K. G. Corley, and A. L. Hamilton. 2013. “Seeking Qualitative Rigor in Inductive Research: notes on the Gioia Methodology.” Organizational Research Methods 16(1):15–31. doi: 10.1177/1094428112452151.

- Gjerde, S, and M. Alvesson. 2020. “Sandwiched: Exploring Role and Identity of Middle Managers in the Genuine Middle.” Human Relations 73(1):124–51. doi: 10.1177/0018726718823243.

- Gleeson, D, and D. Knights. 2008. “Reluctant Leaders: An Analysis of Middle Managers' Perceptions of Leadership in Further Education in England.” Leadership 4(1):49–72. doi: 10.1177/1742715007085769.

- Green, J, and N. Thorogood. 2013. Qualitative Methods for Health Research. London: Sage.

- Grint, K. 2005. “Problems, Problems, Problems: The Social Construction of ‘Leadership.” Human Relations 58(11):1467–94. doi: 10.1177/0018726705061314.

- Grint, K, and B. Jackson. 2010. “Toward “Socially Constructive” Social Constructions of Leadership.” Management Communication Quarterly 24(2):348–55. doi: 10.1177/0893318909359086.

- Guest, G., E. Namey, and M. Chen. 2020. “A Simple Method to Assess and Report Thematic Saturation in Qualitative Research.” PLoS One 15(5):e0232076.

- Harding, N., H. Lee, and J. Ford. 2014. “Who is “the Middle Manager”?” Human Relations 67(10):1213–37. doi: 10.1177/0018726713516654.

- Hernández-Amorós, M. J., and Martínez Ruiz, M. A. 2018. “Principals’ Metaphors as a Lens to Understand How They Perceive Leadership.” Educational Management Administration & Leadership 46(4):602–23. doi: 10.1177/1741143216688470.

- Holmberg, I., and S. Åkerblom. 2001. “The Production of Outstanding Leadership—An Analysis of Leadership Images in the Swedish Media.” Scandinavian Journal of Management 17(1):67–85. doi: 10.1016/S0956-5221(00)00033-6.

- Huo, B., Z. Han, H. Chen, and X. Zhao. 2015. “The Effect of High-Involvement Human Resource Management Practices on Supply Chain Integration.” International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management 45(8):716–46. doi: 10.1108/IJPDLM-05-2014-0112.

- Huy, Q. N. 2002. “Emotional Balancing of Organizational Continuity and Radical Change: The Contribution of Middle Managers.” Administrative Science Quarterly 47(1):31–69. doi: 10.2307/3094890.

- Justesen, L, and N. Mik-Meyer. 2012. Qualitative Research Methods in Organization Studies. Copenhagen: Hans Reitzels Forlag.

- Kabanoff, B., R. Waldersee, and M. Cohen. 1995. “Espoused Values and Organizational Change Themes.” Academy of Management Journal 38(4):1075–104.

- Kaiser, R, and B. Craig. 2014. “Destructive Leadership in and of Organizations.” In The Oxford Handbook of Leadership and Organization, Pp. 260. edited by D. Day. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press

- Kärreman, D, and M. Alvesson. 2001. “Making Newsmakers: Conversational Identities at Work.” Organization Studies 22(1):59–90. doi: 10.1177/017084060102200103.

- Kempster, S, and S. H. Gregory. 2017. “Should I Stay or Should I go?’Exploring Leadership-as-Practice in the Middle Management Role.” Leadership 13(4):496–515. doi: 10.1177/1742715015611205.

- Knies, E., and P. Leisink. 2014. “Leadership Behavior in Public Organizations: A Study of Supervisory Support by Police and Medical Center Middle Managers.” Review of Public Personnel Administration 34(2):108–27. doi: 10.1177/0734371X13510851.

- Krasikova, D. V., S. V. Gren, and J. M. LeBreton. 2013. “Destructive Leadership: A Theoretical Review, Integration, and Future Research Agenda.” Journal of Management 39(5):1308–38.

- Kuhlmann, S, and H. Wollmann. 2019. Introduction to Comparative Public Administration: Administrative Systems and Reforms in Europe. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.