Abstract

This research examines whether the extent of citizen involvement as co-producers in a local government network helps explain the relationship between a network’s structure (density and cliques) and its effectiveness. We developed a model and hypotheses based on the combination of two theories: Provan and Milward inter-organizational network theory and Ostrom’s polycentric theory of co-production. Our main premise is that specific organizational structures enable more citizen co-production which in turn enhances network effectiveness. A sample of 565 participants from 64 Israeli networks in a nation-wide youth at risk program demonstrates that the degree to which the network is divided into subgroups (cliques), not the network’s density, enhances the extent of citizen-users’ co-production, which increases network effectiveness. Theoretical and practical contributions are discussed.

Introduction

Inter-organizational networks, that include autonomous actors such as local government, nonprofit organizations, private companies and citizens, have become a prominent mode of public service delivery (O‘Leary, Gerard, and Bingham Citation2006; Carboni et al. Citation2019). Combining these actor’s capacities, skills, and resources increases effective service delivery (Prahalad and Krishnan Citation2008). Yet, each party’s contribution to such effectivity, especially citizens’, is still being explored (Raeymaeckers and Kenis Citation2016). Based on theories of deliberative and networking democracy (Haus and Sweeting Citation2006), citizens within such networks may be perceived as equal partners, with the right to voice legitimate preferences (Cohen and Rogers Citation1992; Osborne, Radnor, and Nasi Citation2012). Thus, in the local government arena, residents may be seen not merely as citizens and clients; but rather as filling a third role, as co-producers of public services (Ostrom and Ostrom Citation1977; Uster, Beeri, et al. Citation2022; Nowell and Kenis Citation2019). The extent to which citizens indeed fill this role may be of importance to the network’s service delivery effectiveness.

Much public administration literature examines the factors enhancing inter-organizational service network effectiveness (Turrini et al. Citation2009; Wang Citation2016). Some scholars focus on aspects of leadership and management as antecedents of network effectiveness (Agranoff Citation2007; Agranoff and McGuire Citation2001, Citation2003; Milward and Provan Citation2006; Parent and Harvey Citation2009; Saz-Carranza and Ospina Citation2011; Shortell et al. Citation2015). Others examine structural factors (e.g. centralization and brokerage) (Provan and Milward Citation1995; Provan and Sebastian Citation1998) and types of governance relating to network effectiveness (Milward and Provan Citation2006; Kenis and Provan Citation2009; Provan and Kenis Citation2007; Saz-Carranza and Ospina Citation2011; Raab, Mannak, and Cambre Citation2015; Jun Park and Jeong Park Citation2009; Wang Citation2016; Yi Citation2018). However, research has yet to examine how aspects of co-production relate to a network’s effectiveness (Sicilia et al. Citation2016), specifically the role citizens, as co- producers, play in the provision of effective public services. Such co-production is likely to be relevant for network effectiveness as contemporary public administration theory claims that co-producers are not only required to carry out their tasks across various administrative boundaries but are also expected to collaborate with other co-producers across diverse organizational contexts (Spekkink and Boons Citation2016), with networks providing an opportunity for such collaboration. Moreover, if such citizen-co-production indeed enhances the effectiveness of the network, it is important to understand what may facilitate such co-production.

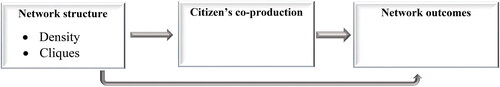

Thus we developed a model and hypotheses (see ) deriving from two main theories. The first, Ostrom (Citation1996, Citation1999) polycentric theory of co-production, emphasizes the importance of dividing the network into independent yet related small working subgroups to enhance citizens’ co-production. The second, the inter-organizational network theory (Provan and Milward Citation1995; Provan and Sebastian Citation1998), emphasizes the importance of the network’s structure for its effectiveness. The theory holds that the network’s structural conditions, such as the extent to which its connections are dense and the existence of small sub-groups (cliques), explain network effectiveness. Combining these approaches enables an understanding of the relationship between the network’s structure and the extent to which citizens co-produce, while also predicting the effect such co-production might have on the network’s effectiveness.

Our model was tested on a sample of 64 purpose-oriented mandated networks in Israeli local authorities. Mandated networks are formed by the national government but led and managed by the local authority (Provan and Kenis Citation2007). Mandated networks constitute a distinctive type of formal network, increasingly utilized by governments to tackle public issues, especially in situations where self-governing networks have not naturally emerged. Policymakers, together with other public agency managers, frequently mandate or strongly encourage the establishment of inter-organizational networks and collaborations involving public and private agencies, nonprofits and citizens that are aimed at addressing complex and challenging public issues. Public policymakers play a pivotal role in shaping critical aspects of the network, including scope, participation, benefit distribution, control mechanisms, and social learning activities (Bartelings et al. Citation2017). After a mandated network has been formed, a public agency, such as the local government in our case, assumes an initial lead role in managing the network, with the goal of fostering self-governance among its members in the long term (Segato and Raab Citation2019).

In mandated networks, members frequently lack pre-established connections and may not share similar visions or objectives. As a result, negotiation to reach agreements becomes essential to cultivate collaboration. This involves establishing reciprocal, close, and collaborative interactions among network members. Therefore, examining the interaction between various actors within the network structure is vital to understand the effectiveness of mandated networks (Segato and Raab Citation2019).

Recognizing the inherent challenges in governing mandated networks, it then becomes imperative to understand the factors that determine their effectiveness in addressing complex public issues (Maurya, Ramesh and Howlett Citation2023). In our study these networks were part of a nationwide welfare program dealing with different youth at risk issues. These networks involve small subgroups called the response teams including citizens who are the parents of youngsters at risk. These parents (i.e. citizens-coproduces) are tasked with designing and evaluating solutions for youth at risk (such as informal programs that include leisure activities for the youth during summer nights and outdoor group activities), and with implementing them alongside local professionals such as social workers. The results of the current study show that specific network structures are more likely to enhance citizen co-production, which, in turn, are related to greater network effectiveness. More precisely, the degree to which the network is divided into subgroups (cliques), not the network’s density, increased the extent of citizen-users’ co-production, which, in turn, enhanced the network’s effectiveness.

Taken as a whole, this research has the potential to make both theoretical and practical contributions. From a theoretical standpoint despite networks serving as the context in which co-production often occurs (Ferlie Citation2021; Poocharoen and Ting Citation2015; Williams et al. Citation2020), research on co-production still lacks a network perspective. Using a network theoretical framework we expand our knowledge of co-production, presenting both the antecedents and consequences of co-production in networks as a basis for a more comprehensive theory of co-production. From a practical perspective, this research may provide public managers - especially those at the local level - with knowledge regarding how to structure the network to enhance citizen co-production as well as network effectiveness.

Literature review and hypotheses’ development

Network effectiveness

Network effectiveness has various definitions (Smith Citation2020; Wang Citation2016). Provan and Milward (Citation1995) first attempted to define it but concluded that various network stakeholders view network effectiveness differently. So, the question of “for whom effective” became important (Provan and Kenis Citation2007). Another issue in the network literature concerns the level of analysis in which effectiveness should be defined (Provan and Milward Citation2001). Networks may be analyzed at three levels: organizational (i.e., an organization within the network), the network level, and the community level. At the organizational level network effectiveness refers to the quality of services provided and client outcomes (Provan and Milward Citation2001). At the network level, network effectiveness is the ability to achieve predetermined goals, innovating while remaining sustainable viable (Turrini et al. Citation2009). At the community level effectiveness regards the contribution the network makes to the communities it serves (Provan and Milward Citation2001).

Despite the above complexity, Sørensen and Torfing (Citation2007, Citation2009) proposed a simple definition at the network level in terms of whether the network delivers on stated goals. Additionally, Provan and Kenis (Citation2007) conceptualized network effectiveness to be the “attainment of positive network level outcomes that could not normally be achieved by individual organizational participants acting independently” (p. 230). Yet, this definition remains broad, and Kenis and Provan (Citation2009) concluded "There is no scientific way to judge whether one criterion is ‘better’ than another in assessing the performance of a network" (p. 443), leaving the research criteria on network effectiveness to vary widely. In the current study we refer to network effectiveness at the network level as the extent the network achieves stated collective goals (Agranoff Citation2003; Whelan 2015). More specifically, as network effectiveness encompasses the outcomes, impacts, and benefits of the whole network, beyond those of any individual network organization, it includes evaluating the extent to which services delivered actually meet citizens’ needs (Lucidarme, Cardon and Willem Citation2016). As the main goal of mandated networks in the current study concerns the improvement of quality of life of youth at risk, we operationalize network effectiveness as the networks’ performance, measured through the municipality’s average score of the relevant youth regarding seven life areas (i.e., health, family, learning, well-being, social belonging, and protection from others and from risky behaviors). This score reflects the average improvement or worsening of youth’s situations in the municipality.

Network structure and network effectiveness

Social network theory maintains that an actor’s position in the network predicts outcomes such as the actor’s performance and behavior (Borgatti, Everett, and Johnson Citation2013). Similarly, at the network level, the assumption is that the outcomes of a group of network actors result from their structural connections (Smith Citation2020; Turrini et al. Citation2009). Based on Provan and Milward (Citation1995) social network framework and other studies (see e.g., Barabási and Frangos Citation2014; Bellotti Citation2009; Provan, Fish, and Sydow Citation2007), network structures represent the extent of network integration. Network integration encompasses two main mechanisms: network coordination and network cohesion. Network coordination refers to the extent to which the network actors are synchronized by a central actor and is examined by the degree of centralization. Network cohesion refers to the social aspects of the network, characterized by reciprocating ties between network actors. One such measure of social network cohesion is density, defined as the proportion of connections among network parties relative to the overall number of possible connections existing among actors (Wasserman and Faust Citation1994; Russell et al. Citation2015). Another cohesion measure relates to the intensity of interactions between actors through subgroups, also called cliques (de Nooy, Mrvar, and Batagelj Citation2011). Cliques are clusters of three or more network actors more closely and intensely inter-related than they are to other members of the network (Alba Citation1982; Scott Citation1991). Previous research found that network structural aspects such as density, centrality, and cliques are related to network performance and effectiveness (Ahuja and Carley Citation1999; Tsai and Ghoshal Citation1998; Tsai Citation2000; Nohria and Garcia-Pont Citation1991; Provan, Fish, and Sydow Citation2007; Provan and Milward Citation1995; Provan and Sebastian Citation1998).

Network density and network effectiveness

Most prior research reported positive relationships between density and network effectiveness (Meier and O'Toole Citation2003; Valente Citation2005; Reagans and McEvily Citation2003). Analyzing data from about 500 Texas school districts, Meier and O'Toole (Citation2003) found that the frequency of interaction between school board members, local business leaders, other school superintendents, state legislators, and the Texas Education Agency positively related to a school district’s performance. Moreover, network density was found as advantageous to network outcomes in diverse settings and relating to different types of performance. For example, studies have established that as an indicator of network cohesion, density is associated with local economic development (Agranoff and McGuire Citation2003); the extent to which the network has the capacity to achieve its desired outcomes (Huang and Provan Citation2007); the extent to which organizations remain engaged in collaborative work (Goldsmith and Eggers Citation2004); the extent of knowledge transfer (Reagans and McEvily Citation2003); and the extent of innovation within the network (Considine, Lewis, and Alexander Citation2009).

Further, public administration literature has found that dense connections are important for distributing information, trust, and influence among network partners (Huang and Provan Citation2007). In this vein, Provan, Huang, and Milward (Citation2009) found that networks existing for long periods with denser interactions perform better. Moreover, denser interactions promote the exchange of resources and negotiations about goals, which eventually facilitate outcomes (Klijn et al. Citation2013). We similarly maintain that in local government service networks, density relates to effectiveness; as such, density implies that the network organizations are tightly connected, enabling better information exchange of, knowledge flow, communication, and trust among the network members, enhancing the likelihood the network organizations will cooperate and achieve its goals. Therefore, we posit that:

H1: There is a positive relationship between the extent to which the network is dense and network effectiveness.

Network subgroups (cliques) and network effectiveness

Studies on network subgroups, such as cliques in inter-organizational networks, found that such cliques contribute importantly to the creation of positive outcomes. Even in for-profit business networks, network success likely results from effective interaction among small, overlapping subsets, often linked through a lead firm (Lorenzoni and Ornati Citation1988). So too with public administration entities (Human and Provan Citation1997; Hurlburt et al. Citation2014; Saldana and Chamberlain Citation2012).

In public administration literature, cohesive sub-networks have been found to positively impact organizational performance (Lerch, Sydow, and Provan Citation2006) due to their tight interconnections, degree of trust and multiple shared resources (Bunger and Gillespie Citation2014). Cliques facilitate learning and information sharing (Provan and Sebastian Citation1998), and foster the pace at which information is internally exchanged (Pieters et al. Citation2009). Intensive collaboration within cliques can generate shared knowledge necessary to performance and innovation during times of environmental instability (Gilsing, Vanhaverbeke, and Pieters Citation2014). In their study on health service delivery networks Bunger and Gillespie (Citation2014) found higher coordinating capacity in small subgroups and greater ability to analyze complex issues. Small subgroups provide more differentiated services matching a clients’ needs. Based on the literature claiming that the higher the number of cliques in the network, the more effective they are (Borgatti and Foster Citation2003; Brass et al. Citation2004; Schneider et al. Citation2003), we assume that this claim will be also relevant in local level mandated networks

More specifically, we claim that as small working subgroups functioning as communities within the network enable better coordination between network actors, the network is more likely to achieve its goals. In addition, as such sub-groups enable better and faster knowledge transfer, they are likely to be more effective in providing quality services. For example, while a network for at-risk youth may benefit from new sources of knowledge regarding reduction of risky situations, implementing this new knowledge may be easier when analyzed in small sub-groups where actions are also tightly coordinated. Thus, we hypothesize:

H2: There is a positive relationship between the number of cliques the network possesses and network effectiveness.

Citizens’ co-production

Co-production is defined as “the process through which inputs used to produce a good or service are contributed by individuals who are not ‘in’ the same organization” (Ostrom Citation1996:1073). Co-production mainly utilizes the practical skills and experience of both public professionals and citizens to provide satisfactory, high quality public services (Jaspers and Steen Citation2020). Elinor Ostrom introduced the term co-production in the 1970s when she tried to explain why neighborhood crime rates went up in Chicago when the city’s police officers retreated from the street into patrol cars (Ostrom Citation1978). Ostrom noted that when the police officers became detached from people’s everyday lives on the streets, they lost the knowledge and experience that came from interaction. Today, the concept of co-production accords well with the term “core economy,” which refers to resources such as the time, energy, experience, knowledge and skills used for internal activities such as production and consumption of services being obtained from households and communities (Coote and Goodwin Citation2010). Bovaird and Loeffler (Citation2012:4) claim that co-production of public services concerns “public service organization and citizens making better use of each other’s assets, resources and contributions to achieve better outcomes or improve efficiency”. Hence, co-production accords with the new governance approach that regards society as pluralistic, where multiple actors contribute to the delivery of public services through multiple systems and processes (Osborne Citation2006). The new public governance (NPG) approach emphasizes cooperating in a partnership between service users, the third sector, and private and public organizations, together encouraging an active citizenry to solve public problems (Osborne Citation2010; Verschuere, Brandsen, and Pestoff Citation2012). Such cooperation emphasizes open government, active citizenship, and co-production as central ideas for advancing and improving public service development (Brix, Tuurnas, and Mortensen Citation2021) and are manifested, for example, in health and social welfare networks (e.g., networks providing services for disabled children and at-risk youth; Uster, Beeri, et al. Citation2022). In such networks parents are involved with professionals in decision-making and provision of support. More recently, the COVID-19 pandemic brought increasing awareness that solutions do not reside with the government alone, and that more effective citizen co-production is paramount. For example, public policy makers responding to Covid-19 challenges collaborated with researchers, private organizations and the public to generate research and knowledge informing policy through co-production (Loeffler Citation2021).

Co-production is generally differentiated from co-creation (Brandsen and Honingh Citation2018). While co-production originally referred to involving users in the production of specific public services, co-creation encompasses the involvement of relevant and affected actors in the creation of innovative public value outcomes. The goal of co-creation is to engage various public and private actors in collaborative processes to identify and define problems, and then to design and implement more strategic, innovative solutions (Haustein and Lorson Citation2023; Scognamiglio et al. Citation2023). In simpler terms, "co-creation" occurs when citizens are engaged in the initial planning of a service, possibly even initiating it. By contrast, when citizens shape the service during later phases of the production cycle, this falls under the category of "co-production” (Ansell, Sørensen, and Torfing Citation2023).

The literature on co-production also distinguishes between service users and non-users referring to this difference as collective versus individual co-production (e.g., Alford Citation2014; Bovaird et al. Citation2015; Parrado et al. Citation2013). Individual co-production refers to co-production of the end users, those who want to improve their own consumption. Service users can actively contribute to improving, evaluating, and refining existing services, and can be involved at all stages of co-production (Mazzei et al. Citation2020). Collective co-production refers to the possibility that the benefits might accrue to the entire community (Brudney and England Citation1983) and thus the co-producers may be representatives of the public at large, not specifically of service users. In the current study, all the citizens in the network are users of the youth at risk services, namely, parents of youth at risk, participating together with local professionals and other actors.

Certainly, co-creation and co-production initiatives come with notable challenges that can impede their effectiveness. One key issue is the lack of clear responsibility and accountability, where multiple stakeholders’ involvement leads to a diffusion of responsibility, making it hard to attribute accountability for decisions or outcomes. This can weaken accountability structures within collaborative endeavors. Moreover, these joint processes often entail higher costs due to their intricate nature. The need for extensive coordination among diverse stakeholders can escalate transaction costs, including time, finances, and efforts required for successful collaboration.

Another significant concern is the potential erosion of democratic principles and the perpetuation of existing inequalities. Despite aiming for inclusive decision-making, power imbalances may arise among stakeholders, undermining democratic ideals. Dominance by influential groups or individuals might skew decision-making, limiting fair representation and exacerbating disparities among participating parties (Verschuere et al. Citation2018).

Mitigating these challenges requires recognizing and understanding the complexities and nuances inherent in collaborative networks. This involves acknowledging the diverse perspectives, interests, and concerns of the included stakeholders. It means adopting a holistic strategy that goes beyond mere acknowledgment and actively involves stakeholders in decision-making processes (Brandsen, Steen, & Verschuere, Citation2018). Moreover, this approach demands substantial commitment and investment from governing bodies or leaders overseeing these collaborative initiatives. It requires dedicating significant time and resources to build robust structures that facilitate transparent communication, equitable participation, and mechanisms for resolving conflicts or power imbalances among stakeholders.

Citizens’ co-production and network effectiveness

Democratic and participation theories suggest that participation in decision-making at the local level enhances both trust (Anheier Citation2014; Borre Citation2000; Irvin and Stansbury Citation2004) and performance in local government, while increasing stakeholder responsibility for outcomes (Dahl Citation1971; Putnam Citation1993; Fung and Wright Citation2001). Trust is of particular importance, strengthening and stabilizing the democratic system and building internal legitimacy, otherwise vulnerable in mandated networks (Provan and Lemaire Citation2012) where the formal expression of mission goals is conducted by an external entity, usually the one initiating the networks (Nye, Zelikow, and King Citation1997; Pharr and Putnam Citation2000). Thus, a high level of citizen co-producers’ participation in service implementation may strengthen the network’s ability to produce high level outcomes, not only be cutting costs and utilizing the citizens’ experience-based knowledge (Pestoff Citation2006), but also by enhancing their responsibility for an effective outcome.

As mentioned above, the current study integrates citizen-users as co-producers who are involved in the design and delivery of services for youth at risk. Users are defined as citizens that “receive private value from the service provided by the agency rather than public value, which is ‘consumed’ jointly, as occurs with public goods” (Alford Citation2002:33). Therefore, the more involved users are in service delivery, the more satisfied they are likely to be with it, particularly because the services have been tailored, partly by themselves, to their personal needs. Citizen users’ experience and expectations motivate them to improve the quality of the service. All in all, users’ main incentive for volunteering in a service provision network is to raise their own quality of life by improving the service. Hence, public service delivery through networks with co-producers-users may promise better services in the eyes of the users themselves (Calabrò Citation2012). (Osborne Citation2013; Alford Citation2014; Bovaird et al. Citation2015; Parrado et al. Citation2013), thereby enhancing the service outcomes (Milton et al. Citation2012; Tisdall Citation2014).

While it is important to acknowledge that many scholars theoretically postulated the positive effects of co-production there are, in fact, studies which have empirically demonstrated these effects. For example, studies on collaborative innovation demonstrated that co-production enhanced innovation in information technology (Chen, Tsou, and Ching Citation2011). In another study, Vamstad (Citation2012) found that co-production enhanced the quality of childcare services in Sweden and facilitated the accountability of their professionals. Additionally, research has shown that a community co-production strategy, focusing on social rather than solely medical measures, was crucial in preventing the spread of Covid-19 (Cepiku et al. Citation2021). Similarly, studies showed that citizens as co-producers played a significant role in assisting socially vulnerable individuals during the pandemic (Pilemalm Citation2020), that citizens that were rapidly engaged through social media platforms to co-produce in Covid-related care services strengthening solidarity (Andersen et al. Citation2020) and that citizen-led ‘hackathon’ resulted in collaborative projects (Beresford et al. Citation2021).

Drawing on the literature on co-production, our basic argument holds that when citizens play a proactive role in a service provision network through co-production, services become more closely aligned with the citizen’s needs (Whitaker Citation1980; Brudney and England Citation1983; Levine and Fisher Citation1984; Thomas Citation2013), leading to better network performance (i.e. more effective outcomes). Moreover, as service users and communities bring to bear such resources as personal experience and knowledge, not necessarily available to professionals, service quality may be improved. Further, active citizen involvement in service delivery may enhance their subjective perceptions of the quality of the service (Loeffler and Bovaird Citation2016). Hence, we posit that:

H3: There is a positive relationship between the extent to which citizens are involved as co-producers in a local service delivery networks and the network’s effectiveness.

Network structure and the extent of citizens’ users’ co-production

Assuming, as we explain above, that co-production is key for network effectiveness, it is important to understand the opportunity space for such co-production (Brix, Tuurnas, and Mortensen Citation2021). This opportunity space for co-production refers to the construction of effective routines for the development of inter-organizational relationships. These relationships should feature nonhierarchical and participatory decision-making, thereby fostering connections through mutual respect, understanding, and trust. This involves partners understanding ‘what’ to share, ‘when’ to share, and ‘in what form’ to share information. In other words, the structures and procedures that encourage collaboration in the form of co-production. For example, the presence or absence of adequate communication infrastructure within public organizations has been highlighted as critical for enabling effective interaction with citizens. These structures collectively influence the capacity of organizations to engage in collaborative endeavors and encourage citizen involvement across diverse domains and services (Farr Citation2018).

Yet, some structure types are more likely to create such opportunity spaces for co-production than others. We claim that network structure characteristics that are associated with network cohesion will be more likely to foster the inter-organizational relationship needed for citizen co-production. This is because cohesive social networks significantly increase an individual’s willingness to collaborate and engage in cooperative behaviors, fostering an environment conducive to knowledge sharing and collaboration (Reagans and McEvily Citation2003). The two main components of network cohesion are presented below and refer to network density and network cliques (de Nooy, Mrvar, and Batagelj Citation2011).

Network density and citizens’ co-production

Density, as a network’s cohesion indicator, is known as a structural factor representing an intense relationship between the actors, which translates into strong mutual information-sharing and trust (Mitchell and Bossert Citation2007). Indeed, Sparrowe et al. (Citation2001) found that dense networks are characterized by greater cooperation, information-sharing, and accountability between network actors. Thus, we assume that dense networks provide a better context for co-production. More specifically, as dense networks facilitate accountability and involve fluid and transparent information-sharing, we assume the citizenry involved in the network will have more faith in the other network partners, thus encouraging greater participation in the co-production process as trust is a crucial motivating factor for citizen participation in a network (Frieling, Lindenberg, and Stokman Citation2014; Voorberg, Bekkers, and Tummers Citation2015). In this vein, Frieling, Lindenberg, and Stokman (Citation2014) in their study on collaborative communities in two case studies, presented that active intensive face to face deliberation and facilitation of trust enhances the citizens motivation to co-produce with public professionals.

Additionally, dense connections are linked to the network’s ability to address challenges, bringing about new solutions for complex problems (Goldsmith and Eggers Citation2004; Considine, Lewis, and Alexander Citation2009). The network’s capacity to address challenges and develop innovative solutions can impact citizens’ motivation to participate. When citizens recognize the network’s effectiveness in problem-solving and perceive their contributions as meaningful toward achieving outcomes, they are more inclined to engage actively within the network (Van Eijk, & Gasco2018). Taken as a whole, we assume that parents of at-risk youth, being users of these services, would be willing to engage in a network characterized by a dense and cohesive structure.

Drawing on the above, we propose that:

H4: There is a positive relationship between the extent to which the network is dense and the extent to which citizens are involved as co-producers.

Network cliques and citizens’ co-production

Cliqued networks encompass closely connected sub-structures. When considering networks within the same organization, people within cliques are often characterized as having shared demographic characteristics (e.g. gender, age), common interests, shared values (Mehra, Kilduff, and Brass Citation1998) and shared knowledge (Li and Rowley Citation2002; Gilsing, Vanhaverbeke, and Pieters Citation2014). Research has found that shared knowledge and values, that enhance collective goals, mutual needs and expected behaviors (Schneider et al. Citation2003) are essential for successful collaboration in co-production processes (Wu, Lii, and Wang Citation2015; Verschuere, Brandsen, and Pestoff Citation2012). Moreover, such sub-groups may enhance citizens co-production in networks through the social capital created in them. As cohesive structures, cliques promote reciprocity, trust and solidarity between the network members (Li and Rowley Citation2002; Gilsing, Vanhaverbeke, and Pieters Citation2014). This is a result of the intensive resource sharing occurring between clique-participants (Lemieux-Charles et al. Citation2005; Ngamassi, Maitland, and Tapia Citation2014; Provan, Milward, and Isett Citation2002; Provan and Sebastian Citation1998), and constitutes strong social capital (Ostrom Citation1996). Social capital was found as an essential factor in enabling co-production because it fosters a strong commitment among individuals (Schafft and Brown Citation2000) and synergizes relations between citizens and government actors (Davidson et al. Citation2007; Thomas, Ott, and Liese Citation2011).

Finally, drawing on a polycentric approach of co-production, the division of the network into subgroups enables adjustment of network’s rules to members’ needs and characteristics (Ostrom Citation1999). Since a highly cliqued network is a decentralized arrangement, autonomous sub-groups can formally act independently of one another and exercise discretion, considering each group’s unique needs and characteristics (Dorsch and Flachsland Citation2017). Hence, cliques may better adapt services and solutions to needs and demands raised by the network’s subgroups. As in our specific case where the citizen co-producers are the users of the service (i.e. parents of youth at risk), who are devoted to the success of the network’s goals, the exchange of information, the reconfiguration of knowledge, and the generation of specialized insights are of specific importance to them. This is pivotal in engaging citizens to actively participate in co-production of such services (Mandell and Keast Citation2008; Brix, Tuurnas, and Mortensen Citation2021). Thus, we propose that:

H5: There is a positive relationship between the number of cliques the network possesses and the extent to which citizens are involved as co-producers.

Indirect effects of citizen’s co-production

We propose that network structure is related to network effectiveness partly due to its influence on the extent to which citizen-users’ co-produce within it. Taken together, we maintain that the extent of citizen co-production explains the relationship between the density and cliques of the network and its effectiveness. Density and cliques are measures of cohesion strengthening mutual trust, resource sharing and reciprocity, creating an opportunity space for citizens to co-produce in local networks. Provan and Sebastian (Citation1998) argued that in such contexts, organizations generate strong trust and collaborative working relationships creating performance advantages (i.e., improving client outcomes). As a result, citizens who participate in local service provision and use the services they provide, are committed to achieving network goals (Uster, Beeri, et al. Citation2022), utilizing their experience and knowledge and increasing trust in local government policy, while helping achieve network goals. (Osborne Citation2013; Alford Citation2014; Bovaird et al. Citation2015; Parrado et al. Citation2013). This is especially true in networks at the local arena where citizens take a prominent part in local policy design and implementation (Haus and Sweeting Citation2006). Hence, we posit that:

H6: There is an indirect relationship between the extent to which the network is dense and the network’s effectiveness, such that the denser the network, the greater the extent to which citizens are involved as co-producers, which in turn enhances networks effectiveness.

H7: There is an indirect relationship between the number of cliques in the network and network effectiveness, such that the greater the number of cliques, the higher the extent to which citizens are involved as co-producers, which in turn enhances the network’s effectiveness.

Methods

Field of study

This study’s unit of analysis is the inter-organizational network participating in “The National Program for Youth at Risk” providing social welfare programs for youngsters at risk, as implemented in 100 Israeli local authorities. The program was conducted under the auspices of the Ministry of Social Affairs and Social Services, in collaboration with five government agencies and a nonprofit organization. The Ministry of Social Affairs mandated that the local authority lead the program in its local authority and all collaborations within its jurisdiction, meaning that the local authority is responsible for managing the networks.

This program exemplifies the co-production process engaging individuals that are not part of a specific organization (Ostrom Citation1996), specifically parents of at-risk youth. The goal of the program is to develop and implement projects for at-risk youth at the local level regarding all aspects of at-risk youth’s lives such as education, leisure, and sports. The idea behind co-production in this case is to harness the practical expertise and experiences of various stakeholders (Bovaird and Loeffler Citation2012), including public professionals as social workers, representatives from local government, and those who are directly affected by the circumstance, i.e. the parents of the at-risk- youth themselves (Jaspers and Steen Citation2020).

A list of 100 local authorities where the program operates was received (although four did not in fact conduct co-production in their local authority). Following additional letters and telephone calls to local authority program managers replies were yielded from 64 local authorities (i.e. response rate of 64%). Of these a total of 565 respondents from the 64 inter-organizational networks participated in the study, each respondent representing a different organization within his/her network.

Dependent variable – Network service effectiveness

To avoid common source bias, we used a secondary data source to assess the dependent variable, i.e., network effectiveness. This measure referred to the outcomes of the local program as defined by the national program headquarters, using data on the children, youth and their parents who received service under this welfare program between September 2016 and December 2017. The headquarters’ staff was responsible for systematic data collection and continuous measurement. The main indicator of success is defined as a reduction in the percentage of youth at risk in the local authority (The Website of the Ministry of Social Affairs, National Program for Children and Youth at Risk, 2018). A general indicator of success was obtained by considering seven life areas where children and young adults were expected to improve. This division derives from the Convention of Child Rights, which defines risk in seven life areas: 1) physical health and development, 2) family affiliation, 3) learning and acquisition of skills, 4) emotional well-being, 5) social belonging, 6) protection against others and 7) protection from risky behaviors.

Each area has several observable risk situations, and each child or teenager entering the program receives a grade according to his/her risk situation in each area. The child receives a grade at the beginning of the school year (September) and at the end of the following calendar year (December). The program headquarters calculates the difference between the grades at these two chronological points (T0- September and T1- the following December) for each child and each area. Average scores for each life area for all participants in the local authority were then calculated, indicating improvement or deterioration of a particular child’s situation. The final program outcome refers to the average score in all seven areas for all participants per municipality. Here, too, this score points to the improvement or worsening of the children’s situation beyond the seven life areas in each local authority. The measure was calculated such that the higher the score the greater the improvement vis-a-vis the average risk level in each local authority.

Independent variables – Network density and number of cliques

Density and clique measures were based on SNA of communication networks (Borgatti, Everett, and Johnson Citation2013; Zohar and Tenne-Gazit Citation2008). First, as in Zohar and Tenne-Gazit (Citation2008) study, each network member was asked to identify all other members with whom he or she interacts. Then, respondents indicated the frequency of interaction with each on these individuals on a five-point Likert scale. These responses were translated to an adjacency matrix, and dichotomized as follows: Frequencies rated between “1-3” received the value “0”- no tie” in the matrix, while 4 - 5 received the value “1”- has a tie”. Survey responses were tabulated and data was recorded in the form of an adjacency matrix in Excel, where each node is assigned both a column and a row in the matrix. We used UCINET to calculate the networks-cohesion-overall density degree. Cliques were measured according to Provan and Sebastian (Citation1998) as the number of subgroups in each local network. UCINET is a common analytical measure of network structure data, as social network analysis (SNA) is used to understand network structure through participants evaluating the location of actors within the network (Kapucu, Hu, and Khosa Citation2014).

The mediator – Citizens’ co-production

The extent to which citizens were involved in co-production was assessed using items from a questionnaire consisting of 16 questions (El Ansari Citation1999) used in El Ansari, Phillips, and Zwi (Citation2004) research about partnerships and coalitions in the health care system, adapted to the context of networks dealing with youth at risk. Questions were also distributed to all network members in each local authority, including the nonprofit, public organizations representatives and citizens who are parents of the youth at risk. Sample items included: “In general, community representatives have a lot of influence in major decisions in this network”. “Youth at-risk and their parents are involved in this program’s implementation”. “I feel that the citizens’ representatives have many opportunities to take part in implementing the program decisions”. The questionnaire and respondents ranked the extent to which they agreed with the items on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “Strongly disagree”-1 to “Strongly agree”-5. Scores were aggregated to the municipality level using the mean, after obtaining appropriate agreement indices: Rwg =.75 and ICC1 = .25; ICC2 = .66.

Control variables

We controlled for the three variables that are usually utilized in the study of local authorities and networks: size of the network (number of players), size of the local authority, i.e., number of residents, and the geographic-social peripheral index of the local authority (indicative accessibility of financial, political and cultural resources; Beeri, Uster, and Vigoda-Gadot Citation2019).

Data procedures and statistical analysis

We used linear regression analysis for the first five hypotheses. For the final two hypotheses, i.e., the indirect effect hypotheses, we used the approach described by Hayes (i.e., PROCESS model 4; Hayes Citation2015). This approach derives from Preacher and Hayes (Citation2004, Citation2008), Shrout and Bolger (Citation2002) and Hayes (Citation2009) using bootstrap estimation of indirect effects (Williams and MacKinnon Citation2008).

Findings

Descriptive statistics

The average number of network participants was 8.6, with a minimum of 5 and a maximum of 21, according to the municipality’s size. Each network is comprised of at least one nonprofit organization, public entities from the local and central government (e.g. representative of the Ministry of Education, head of the local authority’s welfare department) and parents. Each network’s size was accounted for as a control variable. 59% of the networks took place in Jewish local authorities while 41% were from Arabic-speaking local authorities.

Direct effects of the network structure and citizens’ co-production on network effectiveness

H1 and H2 proposed a positive relationship between the extent to which the network is dense and cliqued and its effectiveness. Model 3 in indicates that there were no direct effects of network density or number of cliques on network effectiveness (β = −8.003; p = NS; β = .015; p = NS), thus potentially refuting H1 and H2. According to H3, a positive relationship exists between the extent to which citizens co-produce in the local service delivery process and network effectiveness. Indeed, the findings confirm H3. Model 4 in demonstrates a positive relationship between citizens co-production and network effectiveness (β = 2.460; p = < = .05). Hence, the greater the extent of citizens users’ co-production the more effective the network.

Table 3. Regression model predicting effectiveness.

H4 and H5 proposed a positive relationship between the extent of network density and cliqued and citizens’ corresponding co-production. While H4 was refuted (β=.239; p = NS), the fifth hypothesis was confirmed (β=.05; p<.01). Thus, there is a positive relationship between the number of cliques the network possesses and the extent of citizens’ co-production. shows that the number of cliques in the network makes a significant 12% contribution, explaining the variance in citizen-users’ co-production.

Table 4. Regression model predicting citizens- user’s co-production.

Indirect effects of citizens’ co-production

As mentioned above, we analyzed data using PROCESS to examine the indirect effect of Model 4 (Hayes Citation2015). This method permits an examination of the entire model in a single step. In addition, PROCESS can generate a bootstrap confidence interval for the indirect effects, which has become a widely recommended method for such analysis (Hayes Citation2015). shows is no significant indirect effect of the density on network effectiveness through citizens’ co-production (B = 2.23; SE = 1.02; 95% CI: (-50.6, −6.96)). Thus, we refute H6.

Table 5. Density co-production and network effectiveness -Mediation Model 4 (PROCESS).

indicates a significant indirect effect of the numbers of cliques through co-production with network effectiveness (B = 2.4 SE= 1.1; p<.05; 95% CI:(.0207; .2425, see ). In other words, our findings support H7 and are consistent with the proposal that the more the network is cliqued the greater the extent of citizens’ co-production, in turn enhancing network effectiveness.

Table 6. Cliques-co-production -network effectiveness Mediation Model 4 (PROCESS).

Table 7. Summary of the research hypotheses.

Discussion

This examination of the co-production of citizens in local government purpose-oriented mandated networks focused on a neglected aspect in the literature on public services provision. More specifically, we examined the role played by citizen co-production of services for youth at risk, in the relationship between network structural factors and network effectiveness. Our study indeed found support for such a relationship regarding structural cohesion as measured through cliques. Our findings suggest that the more the network consists of sub-groups, i.e., cliques, the more the network is characterized by high levels of citizens’ co-production, in turn, improving the network program outcomes. As Pestoff (Citation2012) suggested, small-group co-production can be particularly important because it generates intensive collective interaction, and it is more likely than large co-production groups to enhance social capital and reciprocity. Indeed, the literature emphasizes the importance of trust, social capital, mutuality and commitment as main characteristics of small groups which share common goals (Kim et al. Citation2017; Sicilia et al. Citation2016). These characteristics appear to impact the extent to which those members co-produce. This structure corresponds with the polycentric view, since networks with highly cohesive subgroups divide assignments and decentralize the decision-making processes to those subgroups that are still subject to the general rules of the network, yet which can make their own decisions matching their specific needs (Porter Citation2013). Based on Ostrom’s polycentric approach, we provide an additional aspect and empirical evidence for the importance of network sub-groups for citizens co-production. In contrast to a monocentric system that establishes uniform rules for all settings (Ostrom Citation1974, Citation1996, Citation1999), a polycentric system creates diverse sub-groups tailored to different needs and circumstances. In such a polycentric system, rules can be written at a large-system level in general form and then tailored to local circumstances. With specific regard to our case, we argue that sub-groups such as small response teams provide citizen co-producers with a platform to create tailored solutions (e.g. a group addressing leisure needs, a group addressing educational requirements). Thus, it can be argued that, at least in the case of citizen-users, desired outcomes may be achieved when co-producers act in subgroups based on common interests and needs. Our case study specifically focuses on a welfare project aimed at supporting at-risk youth. This demographic is notably diverse and heterogeneous, classified by the Israeli Ministry of Welfare into at least seven distinct profiles and needs. Consequently, a combination of knowledgeable parents familiar with these teenagers’ circumstances is essential. However, these parents seek collaboration not as mere participants in large forums but as experienced contributors, designing and implementing the responses together with the local professionals. This is only achievable within specialized working groups tailored to specific areas of concern. Such smaller units cater to various needs and age groups—such as a group addressing leisure needs or another addressing educational requirements. In our case study, we underscore the effectiveness of smaller response teams or subgroups in facilitating citizen co-producers to devise personalized solutions. We emphasize the significance of these specialized groups, especially in the context of a welfare project aimed at supporting at-risk youth, which constitutes a diverse population with varied needs. In so doing, parents’ collaboration within these smaller units fosters better communication, trust, and commitment, ultimately boosting the success of the projects they lead. These findings on the relationship between cliques and network effectiveness through citizen-users’ coproduction significantly contribute to both the coproduction and the network literatures. Whereas previous studies primarily focused on individual-level factors as determinants of coproduction, the literature on organizational elements is scarce and largely refers to such management capacities as the ability of public managers to appropriately lead financial and human resources focusing on results. These studies also mention the existence of technology and the presence of community organizations in public service delivery as essential antecedents of coproduction (e.g., Alford and Yates Citation2016; Bovaird et al. Citation2015; Andrews and Brewer Citation2010; Alonso et al. Citation2019; Voorberg, Bekkers, and Tummers Citation2015; Meijer Citation2012). However, to the best of our knowledge, no study has referred to organizational or network factors such as network structure as antecedents of co-production. This is especially important as the literature on co-production will need to accommodate the idea that co-production must be examined at different levels of analysis, with the network level constructs impacting the extent to which co-production as a phenomenon occurs.

Interestingly, although most of the literature stresses the importance of cliques to the network and its performance (Brass et al. Citation2004; Schneider et al. Citation2003; Gilsing, Vanhaverbeke, and Pieters Citation2014), we did not find a direct relationship between cliques and network effectiveness. This may be explained by the nature of the specific networks examined. It is possible that in a network tasked with reducing risk situations for youth, the division into sub-groups does not directly enhance the effectiveness of the network. To be effective, the sub-groups need to include citizens who use the service, such as the parents of the youth being served, who are experienced in, motivated and committed to contributing to the service they will later receive. This finding further reinforces the importance of co-production with citizen users as individual co-producers (Uster, Beeri, et al. Citation2022). Consequently, we connect “who" the co-producers are with "which" network is being examined (Nabatchi, Sancino, and Sicilia Citation2017).

Regarding density, the findings suggest that intense interactions in terms of density at the network level, does not necessarily lead to more desirable results. The explanation for this discrepant finding may, too, lie in the nature of the specific program examined in this study. It is possible that to promote good performance in the mandated program for youth at risk, intensive interaction between all actors is less important. In other words, it is possible that network collaboration does not advance this specific program’s goal, but simply serves as a tool for local government to make its job more efficient by saving costs of working with each actor separately. Reducing the rate of youth at risk may not necessarily require a collaborative network with dense relations; rather it requires sub-groups with common needs, goals, and preferences. Therefore, the more the program uses the sub- “response teams” the greater the involvement and the better the outcomes. As McMullin and Needham (Citation2018) showed different public services will be characterized by different barriers and avenues for effective co-production. Taken together, these findings further contribute to the research on networks by emphasizing the importance of understanding the network’s context and the definition of the network’s effectiveness, when examining the relationship between structure and effectiveness.

From both a practical standpoint and a policy perspective, our findings suggest that network-leading organizations should prioritize the establishment and maintenance of specific network structures. This involves creating interconnected groups or cliques within the network and fostering an environment conducive to citizen engagement in co-production activities. Within such structures, purpose-driven networks possessing clear mandates may be expected to be more effective. Therefore, a decentralizing approach to decision-making on social issues is essential. Such an approach allows for discretion and professional autonomy, enabling customized services for residents. It is imperative that managers comprehend that this decentralized approach augments their management role, rather than undermining it. Establishing a network with defined objectives, overseen by a public entity such as a local authority, can determine the framework for public service provision while permitting decentralized decision-making, project execution, and project adaptation to meet the diverse needs of the citizens. Adopting this integrated and open approach is instrumental to guiding local networks as they effectively address complex challenges in social policies.

As we draw insights from our findings, it is crucial to acknowledge the limitations of our study. First, data collection was confined to the change in network outcomes over a single year, potentially overlooking changes and developments over longer periods of time in youth at-risk situations and neglecting various external factors that might influence this specific period. A multi-year longitudinal approach could offer a more dynamic understanding of the relationships proposed in this study. Secondly, the assessment of network effectiveness, derived from objective secondary sources, contrasts with the self-reported data on network structure and citizen involvement obtained from actors within local municipalities, introducing potential biases. Future research should attempt at finding more objective ways to measure co-production. Finally, our examination focused on a specific type of network—mandated by the government and led by a local organization in a specific public area. To broaden our understanding, we recommend future research to explore the impacts of different network structures in various types of networks (e.g., health, welfare, and educational) and compare their distinctions.

Conclusion

The interest in co-production has increased in research and practice among public administration managers over the years. A widely-held opinion has been formed in research that co- production is positive, essential and has many advantages in public services, yet little research has examined the antecedents of this positive phenomena. The network structural perspective on co-production, as presented in the current study, represents a new perspective that may begin to answer the question of how to strengthen co-production and lower the potential barriers to it in inter-organizational networks.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Table 1. Citizens’ co-production -Rwg and ICC measures.

Table 2. Pearson`s correlations.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Anna Uster

Anna Uster, PhD is a lecturer in the Division of Public Administration and Policy at the The Max Stern Yezreel Valley College, Israel. Her research focuses on local service delivery in networked governance, citizens-users’ participation and government-nonprofit relationship. She has published in journals including Regional Studies, Local Government Studies, American Review of Public Administration.

Itai Beeri

Itai Beeri is a Professor of Public Administration and Management at the School of Political Science, The University of Haifa, Israel. His research focuses on local governance, local democracy, central-local relations and local network collaboration. He has published in journals including Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, Policy Sciences, and Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space.

Dana Vashdi

Dana Vashdi is Professor of Public Administration and Management at the School of Political Science, The University of Haifa, Israel. Her research focuses on public management and teamwork, and specifically on learning and innovation in such work. She also investigates factors influencing employee well-being and employee creativity as well as organizational networks. She has published in journals including Academy of Management Journal, Journal of Applied Psychology, Public Administration and Public Administration Review.

References

- Agranoff, R. 2003. “A New Look at the Value-Adding Functions of Intergovernmental Networks.” Seventh National Public Management Research Conference, Georgetown University.

- Agranoff, R. 2007. Managing within Networks: Adding Value to Public Organizations. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

- Agranoff, R., and M. McGuire. 2001. “Big Questions in Public Network Management Research.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 11(3):295–326. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.jpart.a003504.

- Agranoff, R., and M. McGuire. 2003. Collaborative Public Management. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

- Ahuja, M. K., and K. M. Carley. 1999. “Network Structure in Virtual Organizations.” Organization Science 10(6):741–57. doi: 10.1287/orsc.10.6.741.

- Alba, R. D. 1982. “Taking Stock of Network Analysis: A Decade’s Results.” Research in the Sociology of Organizations 1:39–74.

- Alford, J. 2002. “Defining the Client in the Public Sector: A Social-Exchange Perspective.” Public Administration Review 62(3):337–46. doi: 10.1111/1540-6210.00183.

- Alford, J. 2014. “The Multiple Facets of co-Production: Building on the Work of Elinor Ostrom.” Public Management Review 16(3):299–316. doi: 10.1080/14719037.2013.806578.

- Alford, J., and S. Yates. 2016. “Co-Production of Public Services in Australia: The Roles of Government Organisations and co-Producers.” Australian Journal of Public Administration 75(2):159–75. doi: 10.1111/1467-8500.12157.

- Alonso, J. M., R. Andrews, J. Clifton, and D. Diaz-Fuentes. 2019. “Factors Influencing Citizens’ co-Production of Environmental Outcomes: A Multi-Level Analysis.” Public Management Review 21(11):1620–45. doi: 10.1080/14719037.2019.1619806.

- Andersen, D., S. Kirkegaard, J. Toubøl, and H. B. Carlsen. 2020. “Co-Production of Care during COVID-19.” Contexts 19(4):14–7. doi: 10.1177/1536504220977928.

- Andrews, R., and G. A. Brewer. 2010. “Social Capital and Fire Service Performance: Evidence from the U.S. states.” Social Science Quarterly 91(2):576–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6237.2010.00708.x.

- Anheier, H. K. 2014. Nonprofit Organizations. London: Routledge.

- Ansell, C., E. Sørensen, and J. Torfing. 2023. “Public Administration and Politics Meet Turbulence: The Search for Robust Governance Responses.” Public Administration 101(1):3–22. doi: 10.1111/padm.12874.

- Barabási, A. L., and J. Frangos. 2014. Linked: How Everything is Connected to Everything Else and What It Means for Business, Science, and Everyday Life. Cambridge: Basic Books.

- Bartelings, J. A., J. Goedee, J. Raab, and R. Bijl. 2017. “The Nature of Orchestrational Work.” Public Management Review 19(3):342–60. doi: 10.1080/14719037.2016.1209233.

- Beeri, I., A. Uster, and E. Vigoda-Gadot. 2019. “Does Performance Management Relate to Good Governance? A Study of Its Relationship with Citizens’ Satisfaction with and Trust in Israeli Local Government.” Public Performance & Management Review 42(2):241–79. doi: 10.1080/15309576.2018.1436074.

- Bellotti, E. 2009. “Brokerage Roles between Cliques: A Secondary Clique Analysis.” Methodological Innovations Online 4(1):53–73. doi: 10.1177/205979910900400106.

- Beresford, P., M. Farr, G. Hickey, M. Kaur, J. Ocloo, D. Tembo, and O. Williams. 2021. “Introduction to Volume 1.” In COVID-19 and Co-Production in Health and Social Care Research, Policy and Practice: Volume 1: The Challenges and Necessity of Co-Production, 3–16. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Borgatti, S. P., M. G. Everett, and J. C. Johnson. 2013. Analyzing Social Networks. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

- Borgatti, S. P., and P. C. Foster. 2003. “The Network Paradigm in Organizational Research: A Review and Typology.” Journal of Management 29(6):991–1013. doi: 10.1016/S0149-2063_03_00087-4.

- Borre, O. 2000. “Critical Issues and Political Alienation in Denmark.” Scandinavian Political Studies 23(4):285–309. doi: 10.1111/1467-9477.00039.

- Bovaird, T., and E. Loeffler. 2012. “From Engagement to co-Production: The Contribution of Users and Communities to Outcomes and Public Value.” VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 23(4):1119–38. doi: 10.1007/s11266-012-9309-6.

- Bovaird, T., G. G. Van Ryzin, E. Loeffler, and S. Parrado. 2015. “Activating Citizens to Participate in Collective co-Production of Public Services.” Journal of Social Policy 44(1):1–23. doi: 10.1017/S0047279414000567.

- Brandsen, T., and M. Honingh. 2018. “Definitions of Co-Production and Co-Creation.” In Co-Production and Co-Creation, edited by Taco Brandsen, Bram Verschuere, and Trui Steen, 9–17. New York: Routledge.

- Brandsen, T., T. Steen, and B. Verschuere. 2018. Co-Production and Co-Creation: Engaging Citizens in Public Services. London: Taylor & Francis.

- Brass, D. J., J. Galaskiewicz, H. R. Greve, and W. Tsai. 2004. “Taking Stock of Networks and Organizations: A Multilevel Perspective.” Academy of Management Journal 47(6):795–817. doi: 10.5465/20159624.

- Brix, J., S. Tuurnas, and N. Mortensen. 2021. “Creating Opportunity Spaces for co-Production: Professional co-Producers in Interorganizational Collaborations.” Pp. 157–75 in Processual Perspectives on the co-Production Turn in Public Sector Organizations, edited by A. Thomassen and J. Jensen. Hershey PA: IGI Global.

- Brudney, J. L., and R. E. England. 1983. “Toward a Definition of the Coproduction Concept.” Public Administration Review 43(1):59–65. doi: 10.2307/975300.

- Bunger, A. C., and D. F. Gillespie. 2014. “Coordinating Nonprofit Children’s Behavioral Health Services: Clique Composition and Relationships.” Health Care Management Review 39(2):102–10. doi: 10.1097/HMR.0b013e31828c8b76.

- Calabrò, A. 2012. “Co-Production: An Alternative to the Partial Privatization Processes in Italy and Norway.”Pp. 317–36 in New Public Governance, the Third Sector and co-Production, edited by V. Pestoff, T. Brandsen, and B. Verschuere. London: Routledge.

- Carboni, J. L., A. Saz-Carranza, J. Raab, and K. R. Isett. 2019. “Taking Dimensions of Purpose-Oriented Networks Seriously.” Perspectives on Public Management and Governance 2(3):187–201. doi: 10.1093/ppmgov/gvz011.

- Cepiku, D., F. Giordano, T. Bovaird, and E. Loeffler. 2021. “New Development: Managing the Covid-19 Pandemic—From a Hospital-Centred Model of Care to a Community Co-Production Approach.” Public Money & Management 41(1):77–80. doi: 10.1080/09540962.2020.1821445.

- Chen, J.-S., H.-T. Tsou, and R. K. H. Ching. 2011. “Co-Production and Its Effects on Service Innovation.” Industrial Marketing Management 40(8):1331–46. doi: 10.1016/j.indmarman.2011.03.001.

- Cohen, J., and J. Rogers. 1992. “Secondary Associations and Democratic Governance.” Politics & Society 20(4):393–472. doi: 10.1177/0032329292020004003.

- Considine, M., J. M. Lewis, and D. Alexander. 2009. Networks, Innovation and Public Policy. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Coote, A., and N. Goodwin. 2010. “The Great Transition: Social Justice and the Core Economy.” (The New Economics Foundation Working Paper No. 1).

- Dahl, R. A. 1971. Polyarchy: Participation and Opposition. Michigan: Yale University Press.

- Davidson, C. H., C. Johnson, G. Lizarralde, N. Dikmen, and A. Sliwinski. 2007. “Truths and Myths about Community Participation in Post-Disaster Housing Projects.” Habitat International 31(1):100–15. doi: 10.1016/j.habitatint.2006.08.003.

- de Nooy, W., A. Mrvar, and V. Batagelj. 2011. Exploratory Social Network Analysis with Pajek. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Dorsch, M. J., and C. Flachsland. 2017. “A Polycentric Approach to Global Climate Governance.” Global Environmental Politics 17(2):45–64. doi: 10.1162/GLEP_a_00400.

- El Ansari, W., C. J. Phillips, and A. B. Zwi. 2004. “Public Health Nurses’ Perspectives on Collaborative Partnerships in South Africa.” Public Health Nursing (Boston, MA) 21(3):277–86. doi: 10.1111/j.0737-1209.2004.021310.x.

- El Ansari, W. A. H. 1999. “A Study of the Characteristics, Participant Perceptions and Predictors of Effectiveness in Community Partnerships in Health Personnel Education: The Case of South Africa.” (Publication No. 2130071121) [Doctoral dissertation, University of South Wales]. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global.

- Farr, M. 2018. “Power Dynamics and Collaborative Mechanisms in Co-Production and Co-Design Processes.” Critical Social Policy 38(4):623–44. doi: 10.1177/0261018317747444.

- Ferlie, E. 2021. “Concluding Discussion: Key Themes in the (Possible) Move to co-Production and co-Creation in Public Management.” Policy & Politics 49(2):305–17. doi: 10.1332/030557321X16129852287751.

- Frieling, M. A., S. M. Lindenberg, and F. N. Stokman. 2014. “Collaborative Communities through Coproduction: Two Case Studies.” The American Review of Public Administration 44(1):35–58. doi: 10.1177/0275074012456897.

- Fung, A., and E. O. Wright. 2001. “Deepening Democracy: Innovations in Empowered Participatory Governance.” Politics & Society 29(1):5–41. doi: 10.1177/0032329201029001002.

- Gilsing, V., W. Vanhaverbeke, and M. Pieters. 2014. “Mind the Gap: Balancing Alliance Network and Technology Portfolios during Periods of Technological Uncertainty.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 81:351–62. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2013.04.010.

- Goldsmith, S., and W. D. Eggers. 2004. Governing by Network: The New Shape of the Public Sector. Harvard: Brookings Institution Press, Innovations in American Government Program at the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University.

- Haus, M., and D. Sweeting. 2006. “Local Democracy and Political Leadership: Drawing a Map.” Political Studies 54(2):267–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9248.2006.00605.x.

- Haustein, E., and P. C. Lorson. 2023. “Transparency of Local Government Financial Statements: Analyzing Citizens’ Perceptions.” Financial Accountability & Management 39(2):375–93. doi: 10.1111/faam.12353.

- Hayes, A. F. 2009. “Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical Mediation Analysis in the New Millennium.” Communication Monographs 76(4):408–20. doi: 10.1080/03637750903310360.

- Hayes, A. F. 2015. “An Index and Test of Linear Moderated Mediation.” Multivariate Behavioral Research 50(1):1–22. doi: 10.1080/00273171.2014.962683.

- Huang, K., and K. G. Provan. 2007. “Structural Embeddedness and Organizational Social Outcomes in a Centrally Governed Mental Health Services Network.” Public Management Review 9(2):169–89. doi: 10.1080/14719030701340218.

- Human, S. E., and K. G. Provan. 1997. “An Emergent Theory of Structure and Outcomes in Small-Firm Strategic Manufacturing Networks.” Academy of Management Journal 40(2):368–403. doi: 10.2307/256887.

- Hurlburt, M., G. A. Aarons, D. Fettes, C. Willging, L. Gunderson, and M. J. Chaffin. 2014. “Interagency Collaborative Team Model for Capacity Building to Scale-up Evidence-Based Practice.” Children and Youth Services Review 39:160–8. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2013.10.005.

- Irvin, R. A., and J. Stansbury. 2004. “Citizen Participation in Decision Making: Is It Worth the Effort?” Public Administration Review 64(1):55–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6210.2004.00346.x.

- Jaspers, S., and T. Steen. 2020. “The Sustainability of Outcomes in Temporary Co-Production.” International Journal of Public Sector Management 33(1):62–77. doi: 10.1108/IJPSM-05-2019-0124.

- Jun Park, H., and M. Jeong Park. 2009. “Types of Network Governance and Network Performance: Community Development Project Case.” International Review of Public Administration 13(sup1):91–105. doi: 10.1080/12294659.2009.10805142.

- Kapucu, N., Q. Hu, and S. Khosa. 2014. “The State of Network Research in Public Administration.” Administration & Society 49(8):1087–120. doi: 10.1177/0095399714555752.

- Kenis, P., and K. G. Provan. 2009. “Towards an Exogenous Theory of Public Network Performance.” Public Administration 87(3):440–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9299.2009.01775.x.

- Kim, C., H. Nakanishi, D. Blackman, B. Freyens, and A. M. Benson. 2017. “The Effect of Social Capital on Community co-Production: Towards Community-Oriented Development in Post-Disaster Recovery.” Procedia Engineering 180:901–11. doi: 10.1016/j.proeng.2017.04.251.

- Klijn, E. H., V. Sierra, T. Ysa, E. M. Berman, J. Edelenbos, and D. Y. Chen. 2013. “Context in Governance Networks: Complex Interactions between Macro, Meso and Micro. A Theoretical Exploration and Some Empirical Evidence on the Impact of Context Factors in Taiwan, Spain and the Netherlands.” Pp. 233–57 in Context in Public Policy and Management: The Missing Link?, edited by C. Pollitt. Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar Publishing. doi: 10.4337/9781781955147.00027.

- Lemieux-Charles, L., L. W. Chambers, R. Cockerill, S. Jaglal, K. Brazil, C. Cohen, K. LeClair, B. Dalziel, and B. Schulman. 2005. “Evaluating the Effectiveness of Community-Based Dementia Care Networks: The Dementia Care Networks’ Study.” The Gerontologist 45(4):456–64. doi: 10.1093/geront/45.4.456.

- Lerch, F., J. Sydow, and K. G. Provan. 2006. “Cliques within Clusters – Multi-Dimensional Network Integration and Innovation Activities.” [Paper presentation]. The 22nd annual colloquium of the European Group for Organizational Studies, Bergen, Norway.

- Levine, C. H., and G. W. Fisher. 1984. “Citizenship and Service Delivery: The Promise of Coproduction.” Public Administration Review 44:178–89. doi: 10.2307/975559.

- Li, S. X., and T. J. Rowley. 2002. “Inertia and Evaluation Mechanisms in Interorganizational Partner Selection: Syndicate Formation among U.S. investment Banks.” Academy of Management Journal 45(6):1104–19. doi: 10.5465/3069427.

- Loeffler, E. 2021. “Co-Delivering Public Services and Public Outcomes.” Pp. 387–408. in The Palgrave Handbook of Co-Production of Public Services and Outcomes. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Loeffler, E., and T. Bovaird. 2016. “User and Community co-Production of Public Services: What Does the Evidence Tell us?” International Journal of Public Administration 39(13):1–14. doi: 10.1080/01900692.2016.1250559.

- Lorenzoni, G., and O. A. Ornati. 1988. “Constellations of Firms and New Ventures.” Journal of Business Venturing 3(1):41–57. doi: 10.1016/0883-9026(88)90029-8.

- Lucidarme, S., G. Cardon, and A. Willem. 2016. “A Comparative Study of Health Promotion Networks: Configurations of Determinants for Network Effectiveness.” Public Management Review 18(8):1163–217. doi: 10.1080/14719037.2015.1088567.

- Mandell, M. P., and R. Keast. 2008. “Evaluating the Effectiveness of Interorganizational Relations through Networks: Developing a Framework for Revised Performance Measures.” Public Management Review 10(6):715–31. doi: 10.1080/14719030802423079.

- Maurya, D., M. Ramesh, and M. Howlett. 2023. “Governance of Dependency Relationships in Mandated Networks.” Asia Pacific Journal of Public Administration :1–23. doi: 10.1080/23276665.2023.2270085.

- Mazzei, M., S. Teasdale, F. Calò, and M. J. Roy. 2020. “Co-Production and the Third Sector: Conceptualizing Different Approaches to Service User Involvement.” Public Management Review 22(9):1265–83. doi: 10.1080/14719037.2019.1630135.

- McMullin, C., and C. Needham. 2018. “Co-Production in Healthcare.” Pp. 151–60 in Co-Production and co-Creation: Engaging Citizens in Public Services, edited by T. Brandsen, T. Steen, B. Verschuere. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Mehra, A., M. Kilduff, and D. J. Brass. 1998. “At the Margins: A Distinctiveness Approach to the Social Identity and Social Networks of Underrepresented Groups.” Academy of Management Journal 41(4):441–52. doi: 10.5465/257083.

- Meier, K. J., and L. J. O'Toole. Jr. 2003. “Public Management and Educational Performance: The Impact of Managerial Networking.” Public Administration Review 63(6):689–99. doi: 10.1111/1540-6210.00332.

- Meijer, A. 2012. “Co-Production in an Information Age: Individual and Community Engagement Supported by New Media.” VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 23(4):1156–72. doi: 10.1007/s11266-012-9311-z.

- Milton, B., P. Attree, B. French, S. Povall, M. Whitehead, and J. Popay. 2012. “The Impact of Community Engagement on Health and Social Outcomes: A Systematic Review.” Community Development Journal 47(3):316–34. doi: 10.1093/cdj/bsr043.

- Milward, H. B., and K. G. Provan. 2006. A Manager’s Guide to Choosing and Using Collaborative Networks. Washington, DC: IBM Center for The Business of Government.

- Mitchell, A. D., and T. J. Bossert. 2007. “Measuring Dimensions of Social Capital: Evidence from Surveys in Poor Communities in Nicaragua.” Social Science & Medicine (1982) 64(1):50–63. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.08.021.

- Nabatchi, T., A. Sancino, and M. Sicilia. 2017. “Varieties of Participation in Public Services: The Who, When, and What of Coproduction.” Public Administration Review 77(5):766–76. doi: 10.1111/puar.12765.

- Ngamassi, L., C. Maitland, and A. H. Tapia. 2014. “Humanitarian Interorganizational Information Exchange Network: How Do Clique Structures Impact Network Effectiveness?” VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 25(6):1483–508. doi: 10.1007/s11266-013-9403-4.

- Nohria, N., and C. Garcia-Pont. 1991. “Global Strategic Linkages and Industry Structure.” Strategic Management Journal 12(S1):105–24. doi: 10.1002/smj.4250120909.

- Nowell, B. L., and P. Kenis. 2019. “Purpose-Oriented Networks: The Architecture of Complexity.” Perspectives on Public Management and Governance 2(3):169–73. doi: 10.1093/ppmgov/gvz012.

- Nye, J. S., P. Zelikow, and D. C. King. (Eds.). 1997. Why People Don’t Trust Government. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.