Abstract

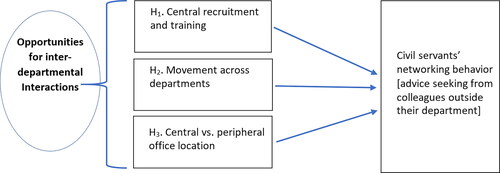

Extant research has identified individual, organizational, and environmental level attributes that shape the variation in public managers’ external networking behavior. It theorized that public managers’ networking behavior is instrumentally motivated by resource deficiencies. We postulate that beyond motivation, managers’ and civil servants’ networking behavior is shaped by the structuring of opportunities for interaction ensuing from HRM policies and the spatial design of government offices. Employing a mixed-method blend of survey and focus groups with low- and mid-level Israeli civil servants in the first eight years of employment, we analyze whether and how opportunities, ensuing from their mode of recruitment and training, mobility between departments, and work at geographically central government offices enable their exchange with colleagues from other departments. We further show that underlying the association between opportunities for interaction and external networking behavior is civil servants’ sense of shared language and outlook and trust-based relations.

Introduction

Public administration research documents the positive effect of managers’ external networking behavior on public organizations’ performance (Johansen and LeRoux Citation2013; Meier and O’Toole Citation2003; O’Toole and Meier Citation2004; Van der Heijden and Schalk Citation2018). External networking behavior, as defined in this article, involves informal information and knowledge exchange between individuals from different organizations regarding professional matters (Van der Heijden Citation2023). Such external networking behavior occurs between individuals linked by interpersonal “social ties” that vary in strength (cf. Granovetter Citation1973). That is by their relationships’ intensity and cognitive and affective nature. Extant research in the public sector regarding such informal exchange tends to focus on senior public managers. Yet, external networking by low- and mid-level civil servants, which is the focus of this article, may likewise benefit their organizations (Walker et al. Citation2007). However, external networking behavior by public managers and their employees cannot be taken for granted. Individuals’ allocation to different government departments constrains the pool of people with whom they regularly interact and communicate (cf. Kleinbaum et al. Citation2013). It further shapes their identities as members of distinct organizations (cf. Ashforth and Mael Citation1989). Moreover, within government division of powers and competition over limited resources produces turf wars, which discourage inter-departmental cooperation (Busuioc Citation2016; Costumato Citation2021; Feiock et al. Citation2010; Gilad et al. Citation2019). It is therefore imperative to discern the factors and causal mechanisms that enable civil servants’ external networking behavior.

Public administration research has identified an array of individual, organizational and environmental factors that shape the variation in public managers’ external networking behavior (Alexander et al. Citation2011; Andrews et al. Citation2011; Binz-Scharf et al. Citation2012; Hansen and Villadsen Citation2017; Ki et al. Citation2020; Rho and Lee Citation2018; Schönherr and Thaler Citation2022, Citation2023; Van der Heijden Citation2023; Zyzak and Jacobsen Citation2020). In the main, researchers have theorized that underlying the association between these different antecedents and public managers’ external networking behavior is their instrumental motivation to overcome contingencies and resource deficiencies (Andrews et al. Citation2011). However, we argue that public managers’ and employees’ networking behavior is further shaped by variation in the opportunities that they have or have had to interact with individuals outside their department. Furthermore, we suggest that underlying the effect of such opportunities is their association with the strength of civil servants’ external social ties (Granovetter Citation1973). Thus, we examine whether and how opportunities for interdepartmental interactions shape civil servants’ external networking behavior.

Drawing on management and human resource management (HRM) research, we examine the effect of opportunities that are rooted in employees’ modes of recruitment and training (e.g., Bannya et al. Citation2023; Cabrera and Cabrera Citation2005; Jolink and Dankbaar Citation2010; Kehoe and Collins Citation2017; Methot et al. Citation2018), movement across departments (Dokko and Rosenkopf Citation2010; Jolink and Dankbaar Citation2010; Kleinbaum Citation2012; Mawdsley and Somaya Citation2016), and government offices’ geographic isolation or co-location (cf. Bell and Zaheer Citation2007; Binz-Scharf et al. Citation2012; Funk Citation2014; Ki et al. Citation2020; Kleinbaum et al. Citation2013). We focus on these factors because they are malleable to managerial intervention through HRM policies and the spatial design of government offices. Thus, enhancing the policy relevance of our findings.

Empirically, we focus on the Israeli central government where turf wars between departments are ubiquitous (Gilad et al. Citation2019), rendering informal relations crucial for overcoming policy deadlocks. We examine external networking behavior by civil servants in the first eight years of their careers, focusing on their inclination to seek out task-related information and advice from colleagues in other government departments. To make sense of civil servants’ networking behavior, we employ a mixed-methods design, involving a survey and follow-up focus groups with a sample of the same participants. Our findings confirm the value of central recruitment and training, movement between departments, and office co-location, as well as participation in interdepartmental working groups. We also show that underlying the associations between these factors and civil servants’ external networking behavior are their strong social ties, as reflected in their perceptions of having a common language, shared outlook, and interpersonal trust with colleagues from other government departments (cf. Cabrera and Cabrera Citation2005).

The rest of the paper proceeds as follows. First, we survey the public administration, business management, and HRM research on the shaping of managers’ and employees’ networking behavior and social ties. Second, we delineate hypotheses and identify their empirical implications for the context that we study. Third, we present the research design, followed by the statistical and focus group data analyses. We conclude by summarizing our findings and their implications. Below we interchangeably use the terms ministry and department to denote central government units.

The shaping of civil servants’ external networking behavior

Research on social networks in the public sector has evolved around two traditions (Meier and O’Toole Citation2005). The first, engaging in whole-network analysis (Provan and Lemaire Citation2012), consists of studies that map the full array of ties between a pre-defined set of actors within one or a small number of clearly bounded social networks. Such analyses most often focus on formal networks between organizations. They aim to describe and explain the overall network structure, and the types of ties that compose it (e.g., Siciliano et al. Citation2021). The second type, involving ego-network analysis (Provan and Lemaire Citation2012), samples individuals, usually senior public managers, and analyzes the antecedents and outcomes of their external networking behavior (e.g., Meier and O’Toole Citation2005; O’Toole and Meier Citation2004; Schönherr and Thaler Citation2022, Citation2023). This article contributes to the latter type of studies, albeit focusing on the networking behavior of low- and mid-level career civil servants with colleagues in other departments.

A recent systematic literature review groups the varied antecedents that shape managers’ external networking behavior under three levels of analysis: environmental, organizational, and individual (Schönherr and Thaler Citation2022). At the individual level, it identifies three main types of antecedents: demographic (e.g., age, gender, race, and ethnicity), socioeconomic (e.g., education, profession, occupational experience, and hierarchical ranking), and psychological (e.g., personality traits; Schönherr and Thaler Citation2023). While explanations vary, researchers have mainly theorized that underlying the effects of the above antecedents are public managers’ instrumental motivations to overcome resource deficiencies (Torenvlied et al. Citation2013) ensuing from environmental contingencies (O’Toole Citation1997), organizational interdependencies, and their personal limited information and experience (Hansen and Villadsen Citation2017). Following this logic, Hansen and Villadsen (Citation2017) suggest that managers who have previous managerial experience from the same or another municipality engage less extensively in strong-tie networking. However, they also found that managers who have previously worked in central government engage more in strong-tie networking with other public managers at both the municipal and central levels. This finding is consistent with the findings of Zyzak and Jacobsen (Citation2020) that regional council managers who have previously worked in other institutional settings are most likely to contact functionally dissimilar and geographically distant actors. Thus, indicating that they are inclined to maintain contacts with external actors whose knowledge and expertise are not readily applicable to performing their current tasks.

The emphasis of current research on managers’ motivation to access external resources is arguably incomplete. It tends to overlook the role of opportunities for interaction that differently prompt and enable individuals’ access to reservoirs of support outside their organization. This is not to say that extant public administration research has completely ignored the role of opportunities for interaction in shaping public managers’ networking behavior. Andrews et al. (Citation2011) have found that a less hierarchical organizational structure offers greater leeway for managers’ external networking. Binz-Scharf et al. (Citation2012) point to professional conferences, FBI inspections, and geographical proximity as opportunities for the forging of social ties among members of different forensic labs. Schönherr and Thaler (Citation2023), whose empirical focus is on managers’ innate psychological traits and public-sector motivation, suggest that their effect may be moderated by situational factors, such as holding inter-organizational committee meetings. Still, other than Binz-Scharf et al. (Citation2012), the role of opportunities for interaction, and the causal mechanisms that underlie their association with public managers’ and employees’ networking behavior, have not been explicitly theorized and empirically unpacked.

Our focus on the structuring of opportunities for interaction draws on research regarding individuals’ networking within business corporations and on Human Resource Management (HRM) research. A key insight of the former literature is that organization members’ relationships are bound by the opportunities, or "social foci" (Feld Citation1981), provided by shared organizational units, professional roles, physical offices, and workgroups that shape their likelihood for interactions (Brennecke and Rank Citation2016; Feld Citation1981; Kleinbaum et al. Citation2013; Lazega and Van Duijn Citation1997; Lomi et al. Citation2014; McEvily et al. Citation2014; Spillane et al. Citation2012). Such opportunities facilitate employees’ frequent interactions with members of their organizational units, whilst curtailing their propensity to interact with those who are outside their habitual workflow (Brass et al. Citation2004). Consequently, employees’ interactions within unit boundaries display dense clusters of overlapping social ties. Conversely, cross-boundary interactions are sparse (Burt Citation2004; Granovetter Citation1973). Compatibly, due to their relative frequency, interactions within unit boundaries tend to yield strong ties, involving a common language and outlook, high interpersonal trust, and positive affect, whereas communication across boundaries is difficult and cautious (e.g., Cabrera and Cabrera Citation2005). Against this backdrop, “network brokers”, whose connections span across different network clusters, are crucial for organizations’ access to untapped knowledge, information, and resources (Burt Citation2004; Burt et al. Citation2013). Individuals whose career history involved atypical movement across units and organizations, resulting in a diverse set of strong social ties, are distinctly positioned to act as brokers (Kleinbaum Citation2012).

Adopting a similar approach, “relational HRM research” (Bannya et al. Citation2023; Methot et al. Citation2018) connects social networks theory with the focus of HRM studies on the facilitation of employees’ ability, motivation, and opportunities to perform their tasks (Appelbaum Citation2000; Blumberg and Pringle Citation1982; Boxall and Purcell Citation2003; Knies and Steijn Citation2021). It argues that “people management” practices, involving, inter alia, the design of employees’ selection and training, career progression, workflow, performance appraisal, and remuneration, all shape their abilities, motivation, and opportunities for informal interactions (Cabrera and Cabrera Citation2005; Jolink and Dankbaar Citation2010; Kehoe and Collins Citation2017; Methot et al. Citation2018). For example, team-based work, performance evaluation, and remuneration enable and incentivize employees’ horizontal coordination and collaboration. Moreover, HRM processes shape employees’ “relational identities” (Methot et al. Citation2018 Sluss & Ashforth Citation2008), that is who they see as their colleagues, and what they see as their roles vis-à-vis these colleagues (e.g., as supervisor-supervisee, mentor-mentee, coworker, etc.). Furthermore, relational HRM research stresses that HRM practices, such as job rotations, can disrupt the stability of employees’ social ties. Such disruptions induce employees to consciously consider their relationships and roles vis-à-vis new and former colleagues (Methot et al. Citation2018).

Following management and relational HRM research, the next section delineates testable hypotheses, which we tailor to the circumstances of the Israeli civil service. We focus on key factors that can create opportunities for interdepartmental interactions, which managers can replicate in other contexts through HRM policies and the spatial design of government offices. Still, the factors that we examine, although important and replicable, are not exhaustive. They are exemplary of how public managers can skillfully create opportunities that enable and motivate employees to engage in interdepartmental interactions.

The Israeli case and research hypotheses

Below we theorize whether and how central recruitment and training, movement between departments and government offices’ geographical location in isolation or proximity, shape Israeli civil servants’ external networking behavior. While external networking behavior may involve different dimensions, our focus is on civil servants’ inclination to seek out professional advice from colleagues in other departments. The Israeli civil service suffers from high friction and turf wars between government ministries over policy and resources (Gilad et al. Citation2019; Maor Citation2013), which likely hinder civil servants’ motivation for seeking and offering advice and support to colleagues in other ministries. Thus, enabling interdepartmental networking is difficult, yet crucial, in this context.

Central recruitment and training

Centralized or cross-departmental training is an HRM practice that provides employees with an opportunity to informally interact across departmental boundaries (cf., Methot et al. Citation2018). Such training can take place, as in the case that we study, before allocation to a government ministry, or at a later point in civil servants’ careers. By enabling a period of intensive, informal, interactions, training programs have the potential to yield interpersonal affect and trust that typify strong social ties (Cabrera and Cabrera Citation2005). Moreover, joint training of employees from different departments inculcates them with a common language and outlook, thereby facilitating the quality of their future communications (Cabrera and Cabrera Citation2005; Jolink and Dankbaar Citation2010). Furthermore, training can explicitly enhance employees’ capabilities to network with others, and/or signal the normative and instrumental value of connecting externally (Kehoe and Collins Citation2017). Still, upon completion of their training, employees’ frequency of interactions with other program members is disrupted, and they need to reconsider their relationships and roles vis-à-vis colleagues within and outside their ministry (Methot et al. Citation2018). Conceptualizing their role as “brokers” (Burt et al. Citation2013; Kleinbaum Citation2012), who exploit their unique position as members of a ministry with access to an array of trusted colleagues in other ministries, is a likely, albeit not a necessary, outcome of this identity reconstruction.

In the Israeli context, the training of new entrants is normally carried out on the job at the ministry level. However, in 2010 the Israeli government established the "Cadets State" program, which is a selective entry-level leadership program that targets individuals who are perceived as having the potential to become change-oriented leaders (Government Decision No. 1244, 17 January 2010). The Cadets are centrally recruited by a unit within the Civil Service Commission (CSC), and, until recently, have all been through an intensive two-year long training as a cadre, consisting of professional workshops, MA in public policy, and practicum prior to their full-time placement. The professional workshops focus on issues such as leadership and innovation and explicitly signal the value of future collaborations between the program’s members. Following their training, the Cadets are placed in entry-level positions across central government, and, in the first four years, are free to request job transfers to other departments.

We hypothesize that graduates of the Cadets program are likely to seek out professional advice outside their ministry. This is due to the opportunity that they have had to develop strong social ties to training cohort members, and the common language, professional outlook, and group identity that they share with all program graduates. Moreover, we expect that the Cadets’ ties to program graduates across the government provide them with further indirect access to a wide array of non-program members. Furthermore, given the program’s collaborative ethos, the Cadets are likely to explicitly consider themselves as brokers. Hence, we expect that:

H1 Members of the Israeli Cadets program, who have been centrally recruited and trained, are inclined to seek professional advice from colleagues outside their ministry.

Movement across departments

Management research points to employees’ transfers within and between business corporations as an antecedent of cross-boundary communications (Dokko and Rosenkopf Citation2010; Kleinbaum Citation2012; Mawdsley and Somaya Citation2016). Civil servants’ movement across government departments may likewise facilitate their inclination to engage in interdepartmental networking behavior. HRM processes can create opportunities for such networking behavior by mandating or at least smoothing civil servants’ interdepartmental job rotations (Jolink and Dankbaar Citation2010; Methot et al. Citation2018). Interdepartmental movement facilitates external networking behavior because civil servants who have worked in other departments are likely to retain strong social ties to former coworkers whom they have previously grown to value, like, and trust (cf. Van der Heijden Citation2023). Moreover, their experience provides them with an understanding of their former coworkers’ organizational language and professional outlook, thereby easing their interdepartmental communications. Furthermore, in contexts where interdepartmental movement is scarce, mobile workers are likely to realize their advantageous position as potential brokers (Dokko and Rosenkopf Citation2010; Kleinbaum Citation2012). Still, the opportunities created by departmental mobility do not necessarily translate into inter-departmental networking. Such civil servants may feel compelled to invest in intra-departmental social ties, or they may believe that their managers and colleagues do not value their external relations, leading them to sever their external ties.

In the Israeli civil service, openings for positions, beyond entry-level jobs, are mostly restricted to government employees from within the same ministry, and movement between departments is scarce. Still, in recent years, ministries have been allowed to recruit candidates from other ministries when lacking qualified internal candidates. Therefore, we hypothesize that in this context mobile workers are distinctively positioned to act as interdepartmental brokers, so:

H2 Israeli civil servants who have moved during their careers between ministries are inclined to seek professional advice from colleagues outside their ministry.

The spatial design of government offices

Civil servants’ external networking behavior may further depend upon opportunities created by the spatial design of government offices, and the extent to which it enables informal interdepartmental interface. Research on business corporations establishes that employees’ and corporations’ geographical proximity is associated with information and knowledge exchange across formal boundaries (e.g., Funk Citation2014; Kleinbaum et al. Citation2013). This is because geographic proximity enables direct informal interactions, which are the basis for interpersonal affect and trust (Bell and Zaheer Citation2007), although these may not be enough to generate a common language and professional outlook. In this vein, Binz-Scharf et al. (Citation2012) and Zyzak and Jacobsen (Citation2020) both found that civil servants and public sector managers tend to hold more frequent contacts with colleagues in geographically proximate organizations. Following in their footsteps, we compare the advice-seeking behavior of Israeli civil servants whose offices are located in governmental hubs, consisting of multiple departments and ministries, versus geographically isolated offices. We therefore hypothesize that:

H3 Israeli civil servants who are physically based in geographically central offices, at a proximate distance to other ministries, are inclined to seek professional advice from colleagues outside their ministry.

Research design

This research employs a sequential mixed-methods design (Greene et al. Citation1989), involving a survey and follow-up focus groups with a sample of the original survey participants. We carried out the focus groups in pursuit of triangulation and investigation of the causal mechanisms that underlie the statistical findings. The project was ethically approved by the IRB of the Social Sciences Faculty of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem (number 128120).

We began the study, during the first half of 2019, via pilot interviews with three of the Cadet program’s managers, and nine of its graduates. The pilot provided us with a more concrete understanding of the program goals, and of the role of networking behavior, as understood by the participants. These interviews informed the design of the survey instrument, which we piloted among civil servants in two independent regulatory agencies.

To validly examine the effect of central recruitment and training, alongside the two other hypotheses, the survey was distributed to two groups of civil servants. One, it was distributed to all graduates of the Cadets program, which in 2019–2020, when we carried out the survey, consisted of 6 cohorts (N = 162), whose then maximum tenure was 8 years. The Cadets have all completed, as part of their training, an MA in public policy, and as such their civil service positions were classified as legal and social science professions. Two, the survey was distributed to a comparable “matched sample” (N = 1,207). This included all civil servants in the Israeli central government, who did not partake in the Cadets program, who were working in the same 25 ministries and agencies as the cadets, and who likewise completed an MA, occupied positions classified as legal or social sciences professions, and whose maximum tenure was eight years.

A weakness of our research design is that assignments to the Cadets program, to movement between departments and to office locations are not random. This entails that there are likely correlations among the factors that we study and between them and other control variables. Moreover, the statistical associations may reflect unknown confounders such as individuals’ innate sociability and consequent motivation and ability to develop wider social networks (cf. Schönherr and Thaler Citation2023). To tackle the first problem, we perform robust analysis in which we use formal matching. Regarding potential confounders, our survey included control variables that were intended to capture participants’ innate sociability to disentangle its effect from that of opportunities for interaction. Moreover, our causal interpretation of the quantitative analysis draws on the analysis of the focus group discussions, which allows us to examine participants’ experiences and understanding of the underlying causal mechanisms.

Survey design, data collection and analysis

Participant selection and response

Links to the online survey were circulated by the Civil Service Commission, on our behalf, between December 2019 and January 2020, to the graduates of cohorts 1 to 6 of the Cadets program and to the matched sample of non-Cadets. The only difference between the two surveys was that the introduction to the survey that was sent to the Cadets specifically addressed them as members of the program. This was done in order to boost participation among the Cadets, which was imperative given their relatively small numbers. Responses were directly collected by the authors through Qualtrics. The overall response rate among participants, following three reminders, was 20% (N = 270/1,369). A 50% response rate among the Cadets (N = 81/162) and a 16% response rate among the matched sample of non-Cadets (N = 189/1,207).

Operationalization of variables

presents the full operationalization of the main variables. The dependent variable, respondents’ advice seeking from colleagues outside their ministry, was measured, employing two operationalizations, relating to the frequency of their external advice seeking and the number of people from whom they most frequently sought advice. Both measures reflect the intensity of respondents’ networking behavior, which is the behavioral dimension of tie strength.

Table 1. Variables operationalization.

For frequency, drawing on an index devised by Hatmaker and Park (Citation2014) to study public-sector employees’ organizational socialization, we constructed seven Likert-scale items, which depict participants’ tendency to engage in friendship social ties (3 items) and to seek professional advice (4 items) from colleagues outside their ministry. This operationalization deviates from that of former studies of public managers’ networking behavior, which typically ask respondents about the frequency of their interactions or contacts with different types of actors, without specifically delineating what this interaction entails (e.g., Meier and O’Toole Citation2005; O’Toole and Meier Citation2004). Our items are arguably more reliable since they convey concrete types of advice seeking so that it is clear to the respondents what exactly they are being asked about. We asked respondents how frequently, in the last six months, have they interacted with colleagues from other government ministries as friends, and how often they approached them for professional advice, with potential responses ranging from “Not at all”, “Once or twice”, “About once a month”, “About once a week”, “Almost every day”, “Every day” (cf. O’Toole and Meier Citation2004). Online Appendix A1 presents a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) showing that a two-factor model, which differentiates friendship and professional advice social ties, makes a significantly better fit than a one-factor model. Still the two factors are highly correlated (r = 0.82). Below, we focus on the 4-item professional advice seeking factor (see ) given its clearer ramifications for organizational performance. Due to the relatively small size of our sample, we employ factor scores, produced with R’s Laavan package (Rosseel, Citation2012), over a latent factor.

Additionally, to measure the number of colleagues outside the ministry from whom participants sought advice we asked them to name the ministries of up to 10 people, from the ministry in which they work or other ministries, whom they most frequently approached for professional advice during the preceding six months. To this end, we provided the respondents with lists of all central government ministries (N = 26) and asked them to select the relevant ministry for each person whom they consulted during the relevant period (c.f., Ryu and Johansen Citation2017). We did not ask respondents to write the names or nicknames of their colleagues since we were concerned that respondents would feel uncomfortable naming concrete individuals from whom they sought advice. Our coding of respondents’ answers quantifies: (a) the overall number (1–10) of colleagues from whom the respondent sought frequent professional advice (“advice count”), and (b) based on our knowledge of respondents’ allocation to ministries, how many of these colleagues were from a different ministry than the one in which the respondent worked at the time of the survey (“external advice”). We use the former as a control variable, and the latter as a dependent variable.

Moving to the key independent variables, to examine H1, we compare members of the Cadets (“Tzoarim” in Hebrew) centralized training program and the matched sample of non-Cadets.

To examine H2, respondents were asked about the extent to which their careers involved movement across government ministries. To consistently measure respondents’ movements we provided them with a full list of central-government ministries and asked for how many of these ministries, including their independent sub-units, they have worked for six months or more, prior to their current position on a scale of “I haven’t worked in any of these departments”, “I worked in one of these departments”, “I worked in two of these departments”, “I worked in three or more of these departments”. We coded respondents’ answers into three categories, involving no past work in another ministry, past work in 1 ministry, and past work in 2 or more ministries since very few participants previously worked in more than two ministries (N = 16).

Finally, to test H3, regarding the effect of geographically central versus peripheral office locations, survey respondents were asked “where physically is the office in which you work most days of the week”. We provided respondents with a list of government office locations, as well as the option of “other”, and ranked them as more/less central (e.g., the central government offices in Jerusalem, Givaat Ram, were ranked as the most central location). The resultant variable has three categories, involving high, medium, and low geographical centrality.

Additionally, we control for individual differences that may bias our findings, including respondents’ gender, age, tenure, and the number of subordinates for whom they are personally responsible. Further, we control for the extent to which respondents perceive their role as such that formally requires regular communications with other ministries. The latter measure, although subjective, is intended to differentiate voluntary and task-mandated inter-departmental networking behavior.

Further, to account for innate differences between respondents, and to disentangle their effects from that of the opportunities for external interaction, we used two types of controls. One, to discern respondents’ general inclination to seek others’ professional advice, we measured the frequency of their interactions with colleagues from their own ministry, essentially replicating the dependent variable that measures the frequency of their advice-seeking outside their ministry. Confirmatory Factor Analysis, comparing a one- versus two-factor solutions, as presented in Online Appendix A1, again suggests that a two-factor model, consisting of intra-ministry friendship social ties, and professional advice seeking, is superior to a one-factor model. As above, our analysis is restricted to respondents’ professional advice seeking from colleagues within their ministry, and due to the relatively small size of our sample, we employ factor scores, estimated with a CFA model. However, further controlling for respondents’ intra-ministry friendship social ties does not alter our key findings (available upon request). Additionally, to further examine respondents’ innate sociability, we asked them about the extent to which they were active, as teenagers, in a youth movement, and as students, in a university-student association.

Survey analysis and findings

presents descriptive statistics for the above variables both across the sample and comparing Cadets (“Tzoarim”) and the matched sample of non-Cadets, including significance tests based on t-test or chi-square comparisons as applicable. A preliminary observation from is that the Cadets, as predicted by H1, exhibit higher rates of external advice seeking in terms of both the frequency of advice seeking and the number of external advisors.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics.

Next, we test hypotheses H1 to H3 in relation to the two dependent variables, which differently measure civil servants’ inclination to seek out professional advice from colleagues outside their ministry. Since civil servants are nested in ministries, we employ linear mixed-effect models, allowing the intercept to vary across ministries, estimated with the lme4 R package (Bates et al. Citation2021). To disentangle within and between ministry-level effects, continuous individual-level independent variables are group-centered to the ministry-level mean (other than with regards to respondents’ prior participation in youth movements or student associations, which are mere controls and of no substantive interest to our analysis).

presents our analysis of civil servants’ frequency of professional advice seeking in the last six months (ranging from never to daily), using, as explained, factor scores estimated with a CFA model (see Online Appendix A1). Model 1 estimates the effect of membership in the Cadets program (with the matched sample as the reference category). Model 2 adds the effect of respondents’ office geographic centrality (with low centrality as the reference). In model 3 we further examine the effect of respondents’ prior work experience in other departments (with no prior experience as the reference). Model 4 adds respondents’ perceptions of their role as inherently requiring external networking behavior (labeled “interfacing role”). Model 5 adds the remaining control variables, including gender, tenure, seniority (number of subordinates), and the proxies for respondents’ general inclination to seek advice from others and innate sociability (factor scores of intra-ministry advice seeking, and prior involvement in a youth movement or a student association, respectively).

Table 3. Linear mixed-effect model: frequency of inter-departmental advice seeking.

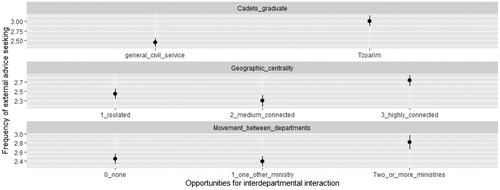

Models 1–5 of consistently suggest, supporting H1, that membership in the Cadets program, compared with the matched sample of non-Cadets, is positively associated with respondents’ higher frequency of advice seeking outside their ministry, amounting to a 0.455-points (p < 0.01) increase (model 5). Likewise, models 3–5 confirm the prediction of H2, indicating that respondents who have previously worked in two or more ministries seek external advice more frequently than those who have never worked in another ministry (a 0.329-points increase, p < 0.01; model 5). The findings are also consistent with the projection of H3. Respondents who work in an office located in the main government hub in Jerusalem more frequently seek professional advice from colleagues in other ministries (0.227 points, p < 0.05, model 5). Additionally, we find positive and significant effects to respondents’ perception of their role as necessitating inter-departmental interface (p < 0.01), and to seniority (p < 0.05). We also find a positive effect to individuals’ general inclination to seek advice, showing that those who more frequently seek professional advice within their ministry are also more likely to do so externally (p < 0.01). To facilitate interpretation of the results, presents a graphic depiction of the predictions of model 5 of regarding H1 to H3, holding all other variables constant, using a composite index of respondents’ frequency of professional advice seeking, which ranges from 1 (=not at all) to 6 (=every day) instead of the factor scores.

Figure 2. Respondents’ frequency of advice seeking with a composite index (1–6).

Notes: regressions predictions from an equivalent to model 5 of run with a composite index of the frequency of advice seeking.

Next, presents our analysis of the second dependent variable regarding the number of people outside the ministry, ranging from one to ten, from whom the respondent most frequently sought advice in the last 6 months. The introduction of the independent and control variables follows the same sequence as in other than the additional inclusion of “advice count”. This measure relates to the overall number of people (1–10) from whom the respondent sought advice, internally and/or externally, which is intended to capture the variation in respondents’ overall inclination to seek professional advice. The findings consistently confirm H1. Model 5 indicates that membership in the Cadets program, compared with the matched sample of non-Cadets, is associated with a 0.521-points (p < 0.01) increase in the number of external advisors. The effects of prior work in other departments (H2) and respondents’ office geographic centrality (H3) are both insignificant. Additionally, we find positive and significant effects to respondents’ seniority (p < 0.05), perception of one’s role as necessitating inter-ministerial interface (p < 0.01), and to prior participation in a student association (p < 0.05).

Table 4. Linear mixed-effect model: number of external advisors (1–10).

As a robustness check, Table A3 of the Online Appendix replicates the findings of models 5 of and with a matching technique that employs pre-weighted samples of Cadets and non-Cadets, using the ebal R package (Hainmueller, Citation2012). Using this procedure, the observations of the matched sample were first weighted such that the means and variances of all covariates matches that of the Cadets, and regressions were then run with weighted observations. As evident from that analysis, our above key findings remain intact.

Overall, the above findings lend strong support for the positive effect of membership in the Cadets centralized training program on both of our dependent variables, confirming H1. The effects of civil servants’ mobility between departments (H2) and the geographic centrality of the offices in which they work (H3) were significant with regard to respondents’ frequency of external advice seeking. They were insignificant with regard to the number of colleagues from whom respondents seek advice.

Focus groups data collection and analysis

Participant selection

The above survey included an invitation for participants to provide us with their email address for follow-up research. After initial analysis of the survey results, we contacted all graduates of the Cadets program (N = 162) and the non-Cadets who provided us with their email address (N = 46) and invited them to participate in focus group discussions. Willing participants, of whom 12 were Cadets and 10 were non-Cadets, were allocated, according to their schedule availability, into 7 focus groups. We assigned Cadets and non-Cadets to separate groups. Each group consisted of 2–4 participants from a mix of ministries. Focus groups were carried out between December 2020 and February 2021, performed on Zoon due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The discussions, each facilitated by one of the two authors, were kicked off by asking the participants to share an example of a colleague in a different ministry from whom they tend to seek advice, how that relationship was formed and its significance. Thereafter, we presented the participants with the above survey findings and sought their feedback about the extent to which it matches their individual experiences. The standardized focus group schedule is available from Online Appendix A2.

With participants’ permission, focus group discussions were recorded, including both audio and picture, and each session was verbatim transcribed. Transcripts were coded by the first author, aided by ATLAS.ti, in consultation with the second author, employing a pre-formulated set of deductive codes, as well as inductive codes that emerged from the data. Based on analysis of the coded transcripts, we identified key themes, which we grouped under three meta-categories: (a) factors that enable and inhibit inter-departmental networking behavior; (b) motivations for seeking advice and information from colleagues in other ministries; and (c) the effects of inter-departmental networking for innovation and collaboration. This article focuses on the first grouping. Online Appendix A3 provides a description of the full coding scheme.

Focus group analysis and findings

As evident below, focus group data analysis provides further validation for the importance of opportunities for interaction in shaping civil servants’ networking behavior. Additionally, the analysis provides relatively rare qualitative access to participants’ understanding of the causal mechanisms that underlie their networking behavior. In line with our theoretical expectations, we find that the opportunities offered by civil servants’ centralized training and movement across departments enhance participants’ external networking behavior due to their sense of shared language or professional outlook and interpersonal trust with colleagues in other ministries. Hence, the attitudinal dimension of strong social ties connects opportunities for interaction and external networking behavior. Finally, we demonstrate participants’ cognizant perception that their strong links to colleagues in other ministries allow them to act as brokers for the exchange of information and collaboration among otherwise unconnected colleagues in their own and other ministries.

Opportunities for interaction and external networking behavior

First, consistent with the findings of the above statistical analysis and with H1, the focus group data analysis confirmed that the Cadets’ training and group identity facilitated their access to cohort and program members across the central government. Participants of the Cadets program related that fellow Cadets are normally their first point of contact when they need advice or information from other ministries. The Cadets expected to receive assistance from and saw themselves as obligated to assist all graduates of the program, even in the absence of direct personal acquaintance. This was the case even when Cadets in other departments were not the obvious point of contact in terms of their roles. For example:

“[As Cadets] we have lots of connections in other ministries—those with whom we were in the same [training] cohort, and even if we weren’t in the same cohort…I assume that some Cadets are less inclined to exploit [the network], and [that] some might be less minded [to help], but this is the [general] expectation, and this how the majority of Cadets are [in fact operating]. If you need information… in another ministry… you would contact the Cadet whom you know there, even if they have nothing to do with [the issue]” (Cadets, 15 December 2020).

“My former colleague here [moved to work at an autonomous regulatory agency] …I consulted [him] … to understand …. what is similar, [and] what is different between the two [regulatory] models [that we and they are employing] … [It] helped me understand how they perceive [the model], how [well] it works for them… [and] what we can learn from it” (Matched sample, 6 December 2020).

“[My unit is located in city X] … [whereas] most of my colleagues are in Jerusalem, and they often meet … for lunch … in one of the offices … I can’t do that … so they exchange personal experiences that I am not at all part of … my communications [with them] is more formal, whereas between them it is also personal and not only professional. It definitely matters” (Matched Sample, 20 December 2020).

Additionally, some participants mentioned that their most meaningful external relationships originated from participation in formal interdepartmental structures such as ad hoc or permanent committees, working groups, and other professional forums. Finally, and consistent with the above statistical findings, the participants suggested that senior managers, and those whose formal tasks necessitate communications with other departments, tend to have more external contacts. They reasoned that this is a combination of the need to manage job responsibilities, and the opportunities that hierarchy and some job descriptions generate. These findings are consistent with management research suggesting that formal structures shape the likelihood for interactions (Feld Citation1981). Moreover, they echo previous findings that public managers’ higher ranking predicts external networking behavior (Hansen and Villadsen Citation2017; Walker et al. Citation2007). Yet, our respondents’ reasoning indicates that this reflects both managers’ task-related needs (Hansen and Villadsen Citation2017) and opportunities (c.f. Alexander et al. Citation2011).

Shared outlook and trust connecting opportunities and networking behavior

Altogether, the focus group data analysis confirmed the expectation that opportunities for inter-departmental interface, owing to central recruitment and training and movement across departments, as well as seniority, occupying similar roles, and participating in cross-departmental committees, facilitate cross-boundary exchange of information and advice. However, participants further stressed that frequent interdepartmental interface creates mere opportunity for developing fruitful relationships with colleagues from other departments. This is a vital starting point, yet it does not guarantee the development and maintenance of meaningful, that is strong, social ties. For example:

“[S]itting on joint [inter-departmental] committees … spending whole days together in the same committee … strengthens the bonds … but it is not that everyone I go into a committee with and sit with once a week for a whole day will become my professional “pivot” [focal point] in another ministry. There needs [to be] something beyond [for that to happen]” (Cadets, 30 December 2020).

“There is an inherent tension between [my] Ministry … and Ministry of X, because of a [jurisdiction] overlap in some areas. And down from the top [executives], there is a spirit of ‘non-cooperation’… When I tried to … pursue [cooperation with Ministry X] …I almost never found someone at the other end who was willing to reciprocate [in Hebrew: ‘take a step towards me’]. There was one person who initiated [a potential collaborative exchange with us] and I believe [that] she got stopped from the top … she [suddenly] cut off all contact” (Cadets, 15 December 2020)

Relating to the first condition, participants often referred to the importance of a “common language” as the basis for inter-departmental information and advice exchange. By this they often meant shared understandings of the issues. That is a joint professional understanding of policy issues, problems, and solutions, so:

“[One type of connection] is to colleagues who have worked with me in the same ministry or unit and moved to other places. So, we already share the same language and have a mutual understanding of the issues [under discussion], and of course [there is also] personal and collegial acquaintance, which is a given” (Matched Sample, 3 January 2021).

“We … share the same professional language … a connection around the same ethos, the same values… we [further] have a trust-based relationship, which was nurtured over many years of [mutual] work, with very explicit understanding that when we speak among ourselves, even if it relates to something that a ministry decided that it is not yet ready to be shared externally…it is fine to talk… and to exchange drafts” (Cadets, 30 December 2020).

Relating to the second condition, participants suggested that meaningful inter-departmental exchange requires not only a joint worldview or a common language, involving a similar understanding of policy issues, professional values and goals, but also trust that transcends parochial ministry loyalties. Together, shared worldview or language and trust-based relations enable opportunities for interface to evolve into strong social ties, which facilitate further networking behavior. Connecting the two conditions, the following participant stressed the need for joint understanding of the issues, and a willingness to transcend organizational vantage points and turf wars as the basis for a meaningful inter-departmental exchange:

“[T]he [inter-departmental] contacts that are easy for me to work with are [those who are] … honest and mission-focused [in Hebrew ‘put things on the table’]. And even if there are all sorts of ministry positions, we … say, ‘Okay, even if we end up not agreeing on the bottom line, because we represent some conflicting interests here, … we more or less understand where everyone is coming from’” (Cadets, 30 December 2020).

“It is not always easy to establish a relationship of trust with someone who is elsewhere in the system [that is in another ministry]. I can think of my colleague who worked with me for a year and a half in the ministry…. and once he moved to [unit X] in Ministry Y, which is [generally] hard for us to crack, then [we could] …. understand … what’s going on there, who is against whom, who should we talk to and about what. Much simpler!” (Matched Sample, 3 January 2021).

Strong social ties as a bridge across government silos

The effect of opportunities for interaction which enable the formation of strong ties, involving a sense of shared outlook and trust, transcends dyadic inter-departmental sharing of information and advice. Focus group participants suggested that their own and other individuals’ strong ties to colleagues in other ministries position them as a useful bridge for further interactions between colleagues in their own and other ministries. For example, this participant expressed her belief that membership in an inter-departmental professional forum of foreign relations employees renders her into a focal bridge for cross-departmental exchange.

“[My equivalent forum member] in Ministry X was approached [by someone in her ministry], because they could not decipher …who is in charge in my ministry for something. She turns to me, [because] she knows me…We create [inter-departmental] connections not just between ourselves [the forum members], but also between other divisions, and so we became a focal point for diverse operations of the [different] ministries” (Matched Sample, 20 Dec 2020)

Similarly, other participants, from both the Cadets and the non-Cadets matched sample, explained that the strong ties among the Cadets are pivotal for bridging cross-departmental exchange among employees who are not graduates of the program.

In conclusion, the analysis of the focus group discussions provides further validation for the finding that individuals’ membership in the Cadets program, and movement across government departments enable cross-departmental networking. It provides weaker support for our expectation that individuals’ geographic location in central versus peripheral offices shapes their likelihood for inter-departmental exchange. Additionally, the focus group analysis points to other types of opportunities for inter-departmental networking. Moreover, it unraveled that underlying the association between opportunities and inter-departmental networking behavior are strong social ties, involving participants’ sense of shared language or outlook regarding policy issues, values and goals, and trust-based relationships. Such common language, outlook and trust may emerge during a period of intensive training, prior work in the same ministry, and sometimes also amidst formal exchange in inter-ministerial committees and forums. It may further stem from the ease of communication among those occupying similar roles or sharing the same academic professions. Likewise, however, a sense of shared outlook and trust may arise, as in the case of the Cadets, from the mere knowledge of two people that they have a common group membership, even if they have not previously met. Finally, and consistent with Burt et al. (Citation2013), we demonstrated individuals’ awareness that strong ties to colleagues in other ministries allowed them to become a bridge for weak ties among colleagues in their own and other ministries.

Discussion

This article points to the importance of opportunities for interaction ensuing from factors that are open to managerial design via HRM policies and the spatial design of government offices. Specifically, our findings provide strong support for the expectation that centralized training as a cadre (H1) enhances the frequency and scope of civil servants’ interdepartmental advice seeking. The expected positive effect of civil servants’ movement between departments (H2) received partial support by the statistical analysis, and strong support from the qualitative findings. The effect of geographic centrality of civil servants’ work locations (H3) received weak and inconsistent support. The focus group data analysis suggested that opportunities for interaction further arise from participation in interdepartmental committees and work groups, and from the common concerns of those occupying similar roles across government. We further show that underlying the association between opportunities for interaction and cross-boundary information and advice exchange are civil servants’ sense of shared language and professional outlook and trust-based relations. Moreover, the focus groups indicate that civil servants’ strong social ties, based on common outlook and trust, form a bridge for inter-departmental exchange among others who are not otherwise connected. Thus, suggesting that civil servants are inclined to recognize and exploit their role as brokers to the benefit of their ministries (Burt et al., Citation2013; Kleinbaum, Citation2012).

The above findings come with some reservations. Our statistical analysis relies on cross-sectional, observational data analysis. It is thus possible that our findings are driven by a confounding association between individuals’ self-selection into the Cadets program or to movement between departments and their inclination to seek advice outside their ministry. To mitigate this concern, we employed multiple controls, matching, and, most importantly, examined the validity of our findings and the causal mechanisms that underlie them through qualitative focus groups.

Conclusion

This article contributes to the public administration literature that seeks to unravel the factors that enable managers’ and civil servants’ external networking behavior. Extant research suggests that managers’ external networking behavior is motivated by organizations’ and individuals’ dependence on external resources. We add to this research by highlighting that individuals, given the opportunities that they have or have had for frequent interactions with colleagues from other departments, are differently positioned to access external resources. Moreover, we propose that many such opportunities are malleable to top-down managerial design. Still, for opportunities to translate into meaningful interdepartmental exchange, civil servants from different departments need to develop strong social ties, which are based on a common language or outlook and interpersonal trust. Common language eases cross-boundary communication, and trust creates incentives and reduces perceptions of the risk of sharing confidential information and valuable knowledge. These findings, and their methodological limitations, point to avenues for further research as detailed below.

First, this article transcends current research by showing that civil servants’ inclination to seek out external advice is shaped not only by their motivational need for resources, as others have suggested, but also by their opportunities for interaction, as our study demonstrates. However, we did not statistically disentangle the relative contribution and interaction between employees’ motivations and opportunities for external networking behavior. Moreover, HRM theory suggests that employees’ performance is shaped not only by their motivations and opportunities, but also by their abilities (Knies and Steijn Citation2021). Relational HRM proposes that this multifaceted approach is likewise applicable to civil servants’ abilities, motivations and opportunities for external networking behavior (Cabrera and Cabrera Citation2005). Hence, future research may employ designs that simultaneously measure employees’ abilities (e.g., their personality traits), motivations (e.g., their beliefs about the value that managers attribute to their social capital) and the opportunities offered by their current or previous experiences.

Second, our study is among few to examine public sector employees’ external networking behavior, and their antecedents. In so doing we deviate from the focus of most studies on the networking behavior of senior public managers. Future research may examine how managerial style facilitates or hinders public-sector employees’ capacity, motivation and opportunities for external communications and collaborations. Specifically, we expect managerial style to shape the inclination of employees, who due to their training or movement between departments, for example, enjoy opportunities for external exchange, to exploit their structurally advantageous position as information and knowledge brokers (Burt et al. Citation2013).

Third, extant public administration research has also pointed to homophily based on similar demographics (Conner Citation2016), roles (Alexander et al. Citation2011), and shared local county membership (Ki et al. Citation2020) as antecedents of managers’ external networking behavior. We also find that homophily, in terms of professional backgrounds, enables information and advice exchange across departmental boundaries. However, probing further, we find that underlying meaningful inter-departmental exchange are civil servants’ shared outlooks and trust-based relations. These findings indicate that common outlooks and affective trust-based relations can be forged between people who a priori have little in common. Future studies may thus pursue further understanding of the prospects for forging opportunities for the development of shared outlooks and trust among civil servants of diverse ministries, roles, professions, and social backgrounds. Creating such opportunities is important since knowledge exchange is most valuable when it takes place across boundaries between dissimilar individuals who are nonetheless strongly connected (Dokko et al. Citation2014; Tortoriello and Krackhardt Citation2010; Tortoriello et al. Citation2012).

Fourth, following relational HRM research, our study suggests that we need to pay attention not only to employees’ and managers’ individual career paths, but also to their shaping by macro-level organizational and governmental structures. Future studies may thus employ rigorous research designs, such as discontinuity regression analyses, or, ideally, random control trials of public organizations’ implementation of real-world changes to their HRM practices in pursuit of enhancing managers’ and employees’ external networking behavior.

Finally, our findings provide significant guidance for practitioners. There is general agreement about the benefits of inter-organizational social ties. Yet, as our respondents acknowledged, such connections are not easily forged. This is so because formal organizational structures generally give precedence to internal interactions. Moreover, civil servants may lack the capabilities to expand their network, or sense that managers devalue their investment in external connections. To transcend this reality, public organizations need to devise a cohesive bundle of HRM practices that aim to advance civil servants’ abilities, motivations and opportunities for external interactions.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (42.9 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Yael Schanin

Yael Schanin is a Ph.D. student at the Federmann School of Public Policy and Governance at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and the head of the legal department of the Israel Competition Authority. Her research focuses on civil servants’ social networks, voice behavior, and collaborations.

Sharon Gilad

Sharon Gilad is a Professor of Political Science and Public Policy at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Her research focuses are bureaucratic politics and behavioral public administration. She employs mixed methods, bridging quantitative and qualitative methods, to make sense of real-world bureaucratic settings. Her most recent work and interest are in how citizens’ political attitudes shape their attraction to government work, and on citizen-state interactions, including citizens’ coping behaviors, representative bureaucracy and the diverse mechanisms that underlie bureaucratic discrimination of minorities. She is also interested in bureaucratic reputation and response to external demands, and in civil-servants’ social networks. Her work has been published in key journals in the field of public administration, and she is member of the editorial boards of several of these key journals.

References

- Alexander, D., J. M. Lewis, and M. Considine. 2011. “How Politicians and Bureaucrats Network: A Comparison across Governments.” Public Administration 89(4):1274–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9299.2010.01890.x.

- Andrews, R., G. A. Boyne, K. J. Meier, J. L. J. O’Toole, and R. M. Walker. 2011. “Environmental and Organizational Determinants of External Networking.” American Review of Public Administration 41(4):355–74. doi: 10.1177/0275074010382036.

- Appelbaum, E. 2000. Manufacturing Advantage: Why High-Performance Work Systems Pay Off. Cornell University Press.

- Ashforth, B. E., and F. Mael. 1989. “Social Identity Theory and the Organization.” Academy of Management Review 14(1):20–39. doi: 10.2307/258189.

- Bannya, A. R., H. T. Bainbridge, and S. Chan‐Serafin. 2023. “HR Practices and Work Relationships: A 20-Year Review of Relational HRM Research.” Human Resource Management 62(4):391–412. doi: 10.1002/hrm.22151.

- Bates, D., M. Maechler, B. Bolker, S. Walker, R. H. B. Christensen, H. Singmann, B. Dai, F. Scheipl, G. Grothendieck, P. Green, et al. 2021. lme4: Linear Mixed‐Effects Models using “Eigen” and S4 (Version 1.1‐27.1).

- Bell, G. G., and A. Zaheer. 2007. “Geography, Networks, and Knowledge Flow.” Organization Science 18(6):955–72. doi: 10.1287/orsc.1070.0308.

- Binz-Scharf, M. C., D. Lazer, and I. Mergel. 2012. “Searching for Answers: Networks of Practice among Public Administrators.” American Review of Public Administration 42(2):202–25. doi: 10.1177/0275074011398956.

- Blumberg, M., and C. D. Pringle. 1982. “The Missing Opportunity in Organizational Research: Some Implications for a Theory of Work Performance.” Academy of Management Review 7(4):560–9.

- Boxall, P., and J. Purcell. 2003. “Strategic HRM: ‘Best Fit’ or ‘Best Practice.” Strategy and Human Resource Management 1:47–70.

- Brass, D. J., J. Galaskiewicz, H. R. Greve, and W. Tsai. 2004. “Taking Stock of Networks and Organizations: A Multilevel Perspective.” Academy of Management Journal 47(6):795–817. doi: 10.5465/20159624.

- Brennecke, J., and O. N. Rank. 2016. “The Interplay between Formal Project Memberships and Informal Advice Seeking in Knowledge-Intensive Firms: A Multilevel Network Approach.” Social Networks 44:307–18. doi: 10.1016/j.socnet.2015.02.004.

- Burt, R. S. 2004. “Structural Holes and Good Ideas.” American Journal of Sociology 110(2):349–99. doi: 10.1086/421787.

- Burt, R. S., M. Kilduff, and S. Tasselli. 2013. “Social Network Analysis: Foundations and Frontiers on Advantage.” Annual Review of Psychology 64(1):527–47. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143828.

- Busuioc, E. M. 2016. “Friend or Foe? Inter‐Agency Cooperation, Organizational Reputation, and Turf.” Public Administration 94(1):40–56. doi: 10.1111/padm.12160.

- Cabrera, E. F., and A. Cabrera. 2005. “Fostering Knowledge Sharing through People Management Practices.” International Journal of Human Resource Management 16(5):720–35. doi: 10.1080/09585190500083020.

- Conner, T. W. 2016. “Representation and Collaboration: Exploring the Role of Shared Identity in the Collaborative Process.” Public Administration Review 76(2):288–301. doi: 10.1111/puar.12413.

- Costumato, L. 2021. “Collaboration among Public Organizations: A Systematic Literature Review on Determinants of Interinstitutional Performance.” International Journal of Public Sector Management 34(3):247–73. doi: 10.1108/IJPSM-03-2020-0069.

- Dokko, G., and L. Rosenkopf. 2010. “Social Capital for Hire? Mobility of Technical Professionals and Firm Influence in Wireless Standards Committees.” Organization Science 21(3):677–95. doi: 10.1287/orsc.1090.0470.

- Dokko, G., A. A. Kane, and M. Tortoriello. 2014. “One of Us or One of My Friends: How Social Identity and Tie Strength Shape the Creative Generativity of Boundary-Spanning Ties.” Organization Studies 35(5):703–26. doi: 10.1177/0170840613508397.

- Feiock, R. C., I. W. Lee, Park, H. J., and Lee, K. H. 2010. Collaboration Networks among Local Elected Officials: Information, Commitment, and Risk Aversion. Urban Affairs Review, 46(2), 241–262. doi: 10.1177/1078087409360509.

- Feld, S. L. 1981. “The Focused Organization of Social Ties.” American Journal of Sociology 86(5):1015–35. doi: 10.1086/227352.

- Funk, R. J. 2014. “Making the Most of Where You Are: Geography, Networks, and Innovation in Organizations.” Academy of Management Journal 57(1):193–222. doi: 10.5465/amj.2012.0585.

- Gilad, S., S. Alon‐Barkat, and C. M. Weiss. 2019. “Bureaucratic Politics and the Translation of Movement Agendas.” Governance 32(2):369–85. doi: 10.1111/gove.12383.

- Granovetter, M. S. 1973. “The Strength of Weak Ties.” American Journal of Sociology 78(6):1360–80. doi: 10.1086/225469.

- Greene, J. C., V. J. Caracelli, and W. F. Graham. 1989. “Toward a Conceptual Framework for Mixed-Method Evaluation Designs.” Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 11(3):255–74. doi: 10.2307/1163620.

- Hainmueller, J. 2012. “Entropy Balancing for Causal Effects: A Multivariate Reweighting Method to Produce Balanced Samples in Observational Studies.” Political Analysis 20(1):25–46. doi: 10.1093/pan/mpr025.

- Hansen, M. B., and A. R. Villadsen. 2017. “The External Networking Behaviors of Public Managers-The Missing Link of Weak Ties.” Public Management Review 19(10):1556–76. doi: 10.1080/14719037.2017.1299200.

- Hatmaker, D. M., and H. H. Park. 2014. “Who Are All These People? Longitudinal Changes in New Employee Social Networks within a State Agency.” American Review of Public Administration 44(6):718–39. doi: 10.1177/0275074013481843.

- Johansen, M., and K. LeRoux. 2013. “Managerial Networking in Nonprofit Organizations: The Impact of Networking on Organizational and Advocacy Effectiveness.” Public Administration Review 73(2):355–63. doi: 10.1111/puar.12017.

- Jolink, M., and B. Dankbaar. 2010. “Creating a Climate for Inter-Organizational Networking through People Management.” International Journal of Human Resource Management 21(9):1436–53. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2010.488445.

- Kehoe, R. R., and C. J. Collins. 2017. “Human Resource Management and Unit Performance in Knowledge-Intensive Work.” Journal of Applied Psychology 102(8):1222–36. doi: 10.1037/apl0000216.

- Ki, N., C. G. Kwak, and M. Song. 2020. “Strength of Strong Ties in Intercity Government Information Sharing and County Jurisdictional Boundaries.” Public Administration Review 80(1):23–35. doi: 10.1111/puar.13135.

- Kleinbaum, A. M. 2012. “Organizational Misfits and the Origins of Brokerage in Intrafirm Networks.” Administrative Science Quarterly 57(3):407–52. doi: 10.1177/0001839212461141.

- Kleinbaum, A. M., T. E. Stuart, and M. L. Tushman. 2013. “Discretion within Constraint: Homophily and Structure in a Formal Organization.” Organization Science 24(5):1316–36. doi: 10.1287/orsc.1120.0804.

- Knies, E., and B. Steijn. 2021. “Introduction to the Research Handbook on HRM in the Public Sector.” Pp. 1–12, in Research Handbook on HRM in the Public Sector. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Lazega, E., and M. Van Duijn. 1997. “Position in Formal Structure, Personal Characteristics and Choices of Advisors in a Law Firm: A Logistic Regression Model for Dyadic Network Data.” Social Networks 19(4):375–97. doi: 10.1016/S0378-8733(97)00006-3.

- Lomi, A., D. Lusher, P. E. Pattison, and G. Robins. 2014. “The Focused Organization of Advice Relations: A Study in Boundary Crossing.” Organization Science 25(2):438–57. doi: 10.1287/orsc.2013.0850.

- Maor, M. 2013. “Bureaucratic Representation in Israel.” Pp. 204–57, in Representative Bureaucracy in Action: Country Profiles from the Americas, Europe, Africa, and Asia, edited by Maravic Patrick von Schroeter, Eckhard, and B. Guy Peters. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Mawdsley, J. K., and D. Somaya. 2016. “Employee Mobility and Organizational Outcomes: An Integrative Conceptual Framework and Research Agenda.” Journal of Management 42(1):85–113. doi: 10.1177/0149206315616459.

- McEvily, B., G. Soda, and M. Tortoriello. 2014. “More Formally: Rediscovering the Missing Link between Formal Organization and Informal Social Structure.” Academy of Management Annals 8(1):299–345. doi: 10.5465/19416520.2014.885252.

- Meier, K. J., and J. L. J. O’Toole. 2003. “Public Management and Educational Performance: The Impact of Managerial Networking.” Public Administration Review 63(6):689–99. doi: 10.1111/1540-6210.00332.

- Meier, K. J., and J. L. J. O’Toole. 2005. “Managerial Networking: Issues of Measurement and Research Design.” Administration & Society 37(5):523–41. doi: 10.1177/0095399705277142.

- Methot, J. R., E. H. Rosado-Solomon, and D. G. Allen. 2018. “The Network Architecture of Human Capital: A Relational Identity Perspective.” Academy of Management Review 43(4):723–48. doi: 10.5465/amr.2016.0338.

- O’Toole, L. J., Jr,., and K. J. Meier. 2004. “Desperately Seeking Selznick: Cooptation and the Dark Side of Public Management in Networks.” Public Administration Review 64(6):681–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6210.2004.00415.x.

- O’Toole, J. L. J. 1997. “Treating Networks Seriously: Practical and Research-Based Agendas in Public Administration.” Public Administration Review 57(1):45–52. doi: 10.2307/976691.

- Provan, K. G., and R. H. Lemaire. 2012. “Core Concepts and Key Ideas for Understanding Public Sector Organizational Networks: Using Research to Inform Scholarship and Practice.” Public Administration Review 72(5):638–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6210.2012.02595.x.

- Rho, E., and K. Lee. 2018. “Gendered Networking: Gender, Environment, and Managerial Networking.” Public Administration Review 78(3):409–21. doi: 10.1111/puar.12918.

- Rosseel, Y. 2012. “Lavaan: An R Package for Structural Equation Modeling.” Journal of Statistical Software 48(2):1–36. doi: 10.18637/jss.v048.i02.

- Ryu, S., and M. S. Johansen. 2017. “Collaborative Networking, Environmental Shocks, and Organizational Performance: Evidence from Hurricane Rita.” International Public Management Journal 20(2):206–25. doi: 10.1080/10967494.2015.1059915.

- Schönherr, L., and J. Thaler. 2022. “Managerial Networking: A Systematic Literature Review and Research Agenda.” International Public Management Journal 1–31. doi: 10.1080/10967494.2022.2125603.

- Schönherr, L., and J. Thaler. 2023. “Personality Traits and Public Service Motivation as Psychological Antecedents of Managerial Networking.” Public Management Review 1–27. doi: 10.1080/14719037.2023.2192218.

- Siciliano, M. D., W. Wang, and A. Medina. 2021. “Mechanisms of Network Formation in the Public Sector: A Systematic Review of the Literature.” Perspectives on Public Management and Governance 4(1):63–81. doi: 10.1093/ppmgov/gvaa017.

- Sluss, D. M., and B. E. Ashforth. 2008. “How Relational and Organizational Identification Converge: Processes and Conditions.” Organization Science 19(6):807–23. doi: 10.1287/orsc.1070.0349.

- Spillane, J. P., C. M. Kim, and K. A. Frank. 2012. “Instructional Advice and Information Providing and Receiving Behavior in Elementary Schools: Exploring Tie Formation as a Building Block in Social Capital Development.” American Educational Research Journal 49(6):1112–45. doi: 10.3102/0002831212459339.

- Torenvlied, René, Agnes Akkerman, Kenneth J. Meier, and Laurence J. O’Toole. Jr. 2013. “The Multiple Dimensions of Managerial Networking.” American Review of Public Administration 43(3):251–72. doi: 10.1177/0275074012440497.

- Tortoriello, M., and D. Krackhardt. 2010. “Activating Cross-Boundary Knowledge: The Role of Simmelian Ties in the Generation of Innovations.” Academy of Management Journal 53(1):167–81. doi: 10.5465/amj.2010.48037420.

- Tortoriello, M., R. Reagans, and B. McEvily. 2012. “Bridging the Knowledge Gap: The Influence of Strong Ties, Network Cohesion, and Network Range on the Transfer of Knowledge between Organizational Units.” Organization Science 23(4):1024–39. doi: 10.1287/orsc.1110.0688.

- Van der Heijden, M., and J. Schalk. 2018. “Making Good Use of Partners: Differential Effects of Managerial Networking in the Social Care Domain.” International Public Management Journal 21(5):729–59. doi: 10.1080/10967494.2016.1199449.

- Van der Heijden, M. 2023. “Liking or Needing? Theorizing on the Role of Affect in Network Behavior.” Perspectives on Public Management and Governance 6(1):28–39. doi: 10.1093/ppmgov/gvac025.

- Walker, R. M., L. J. O’Toole, Jr., and K. J. Meier. 2007. “It’s Where You Are That Matters: The Networking Behaviour of English Local Government Officers.” Public Administration 85(3):739–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9299.2007.00667.x.

- Zyzak, B., and D. I. Jacobsen. 2020. “External Managerial Networking in Meta-Organizations. Evidence from Regional Councils in Norway.” Public Management Review 22(9):1347–67. doi: 10.1080/14719037.2019.1632922.