?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Mission valence holds a vital motivational potential vis-à-vis employees which subsequently can improve organizational performance. But which types public leadership hold the potential to cultivate mission valence as an attraction among their employees to the organizational vision? Both transformational leadership and reputation management involve visioning behavior performed by public managers but differ in terms of the former primarily targeting external audiences, for the purpose of fostering positive perceptions among those audiences of the organization’s contribution to society, and the latter targeting employees to transcend their own self-interest and achieve organizational goals. Based upon panel data using repeated measures of 193 employees in three Danish regulatory agencies, the article shows that both transformational leadership and reputation management is positively related to employee’s mission valence. By so doing the article adds to public leadership literature suggesting reputation management as an alternative route by which public managers can foster employee’s mission valence.

Introduction

Public organizations hold the potential to develop an ‘aura of magnetic appeal’ (Goodsell Citation2011a:477) condensed in their public vision or mission. Visions ideally embody and reflect the values, which come to characterize organizations over time (Selznick Citation1957). The ability of public managers to cultivate such a vision holds a motivational potential vis-à-vis their employees (Goodsell Citation2011b:2; Wright et al. Citation2012), and therefore a potential to influence performance positively. But how do public managers make their employees feel attracted to the organizational vision and the values and purpose embodied in the organizational vision?

Employee’s attraction to the vision has been conceptualized as mission valence. Originally defined by Rainey and Steinbauer (Citation1999), mission valence refers to an ‘employee’s perception of the attractiveness and salience of an organization’s purpose’ (Wright and Pandey Citation2011:24) or vision (Jensen et al. Citation2018). As such mission valence reflects the degree to which the organizational purpose and vision is perceived as ‘worthwhile’ to pursue (Rainey and Steinbauer Citation1999:16) due to ‘the intrinsic value’ which employee can see in the vision (Wright Citation2007:60). Therefore, mission valence resides in employees’ emotional or affective sides (Rainey and Steinbauer Citation1999:17; Vogel et al. Citation2023:1506).

Although formulated more than two decades ago, mission valence has gained increased scholarly attention within public management in recent years (Guerrero and Chênevert Citation2021:447), not least due to its relation to important employee outcomes and more downstream outcomes such as performance. Public management research has identified positive relations between mission valence and employee’s work motivation (Wright Citation2007), work efforts (Resh et al. Citation2018), extra-role behavior as well as performance (Caillier Citation2014, Citation2015; Guerrero and Chênevert Citation2021). In addition, mission valence has been identified as negatively related to turnover intentions (Caillier Citation2016) and emotional exhaustion (Bosak et al. Citation2021).

Next to identifying the consequences of mission valence, public management scholars have argued and empirically investigated whether and how in particular transformational leadership behavior fosters mission valence (Bosak et al. Citation2021; Desmidt and Prinzie Citation2019; Jensen et al. Citation2018; Moynihan et al. Citation2014; Wright et al. Citation2012) due to transformational leaderships emphasis on sharing the organizational vision with employees (Jensen et al Citation2019b; Vogel et al. Citation2023:1507).

However, transformational leadership is not the only leadership strategy performed by public managers where the organizational vision is the main mechanism. Defined as behavior that ‘attempts to identify perceptions and expectations held by audiences, to prioritize between different audiences (and expectations), and to communicate the vision of the organization to these (specific) audiences’ (Pedersen and Salomonsen Citation2023:43) reputation management also involves visioning behavior. However, contrary to when public managers perform transformational leadership and shares the vision with internal audiences being their employees, performing reputation management primarily targets external audiences with the intent to convey a positive portrayal of the organization and foster a positive perception among those audiences in terms of the organization’s contribution to society (Cornelissen Citation2017).

Building on autocommunication theory, we suggest that reputation management, albeit primarily targeting external audiences, also foster employees’ mission valence. According to Broms and Gahmberg (Citation1983), external communication often functions as autocommunication through which organizations tell themselves what they aspire to be in the future.

Reputation management may involve processes of autocommunication; that is, when public managers communicate the organizational vision externally, they simultaneously communicate to their employees. The simultaneous communication to external audiences and internal organizational members is argued to be one of the most powerful ways for managers to tell their employees who they are and aspire to be (Christensen Citation1997). As such, communicating to external audiences when performing reputation management provides an additional (indirect) channel through which public managers can communicate the vision to their employees (Jensen et al Citation2018). To investigate the empirical validity of the proposed theoretical arguments and expectations, the article investigates the following research question: Are public managers reputation management and transformational leadership related to their employee’s mission valence?

By pursuing this research question, the article expands existing research on public management and leadership in two interrelated respects.

First, in relation to research on leadership and mission valence, we empirically investigate and demonstrate that transformational leadership is not the only leadership behavior which we find to be positively related to employee’s mission valence. As such the article addresses the call for expanding the repertoire of leadership and management strategies investigated in public management research (Crosby and Bryson Citation2018:1277). Introducing reputation management next to the more established transformational leadership construct within public management research rests on the criterion that the mechanism is the same, that being the vision, although the main audience differ as reputation management is primarily targeted external audiences.

Second, this provides for developing existing research on reputation management within the public sector. Departing from bureaucratic reputation theory as coined by Carpenter (Citation2001, Citation2010), the relevance of reputation consciousness behavior has attracted increased scholarly interest (for an overview, see Maor Citation2016). Empirical evidence of reputation-based motives for explaining agency behavior within the public sector include studies of reactive communication responses (e.g. Moschella and Pinto Citation2019); as more proactive engagement in changes in output as well as public relation activities (Maor and Sulitzeanu-Kenan Citation2015) and external performance assessments (Doering et al. Citation2021) when facing reputational threats (Maor Citation2020). However, systematic theorizing with respect to the reputation management behind those agency responses, is relatively limited, at least in terms of providing a clear theoretical definition of reputation management when subject for empirical investigation (e.g., Christensen and Gornitzka Citation2019 on regulatory agencies’ communication on their websites or Wei et al. Citation2021 on local governments’ responses to public protests in the context of constructing nuclear projects).

Recent reputation research has started to explore the potential positive and negative relations between organizational reputation and employee outcomes, including employee engagement (Hameduddin Citation2021; Hameduddin and Shinwoo Citation2021) and job choice decisions (Lee and Zhang Citation2021), as well as between reputation management and employee voice behavior (Wæraas and Dahle Citation2020). While this provides for better understanding whether and how a positive perception of the organization by external audiences may be positively related to important employee outcomes, the managerial behaviors fostering this perception in the first place remains ‘black boxed’. In the article, we develop bureaucratic reputation research by, based upon a clear definition of reputation management (Pedersen and Salomonsen Citation2023), investigting the relationship between reputation management and employee outcomes.

In addition, our article responds to recent calls within public administration research for using panel design to investigate the development of perceptions and attitudes over time (Stritch Citation2017), as the empirical analysis is based on survey responses from 193 employees in three Danish regulatory agencies in a two-wave panel data design. The three agencies were chosen based on two criteria, being comparability and resembling ‘most likely’ cases to find a relation between reputation management and employees’ mission valence. Hence, they are all Danish regulatory agencies having, relative to other agencies, experienced a high level of also negative media coverage.

Theory

Fostering mission valence involves an appeal to employees’ affective orientations (Rainey and Steinbauer Citation1999:17; Vogel et al. Citation2023:1506). As noted by Caillier, the original definition of mission valence by Rainey and Steinbauer (Citation1999) extends the idea of valence introduced by expectancy theory, where valence reflects ‘an individual’s emotional orientation with respect to, or the value placed on expected outcome (Croom, 1946)’ (2016:228). On this basis, Rainey and Steinbauer noted how also a mission or vision can be experienced and felt as rewarding (1999:16, see also Caillier Citation2016:228). As such, mission valence refers to how employees perceive the attractiveness of an organizational vision, deriving from ‘the satisfaction an individual experiences (or anticipates receiving) from advancing that purpose’ (Wright and Pandey Citation2011:24).

Mission valence has until now primarily been investigated in relation to transformational leadership (but see Vogel et al. Citation2023), where the ability to identify a direct relationship between transformational leadership and mission valence has been mixed. Wright, Moynihan and Pandey find transformational leadership to be positively related to managers’ mission valence but only through PSM and goal clarity in the context of U.S. local government (2012). Further, in the context of U.S. state agencies, Pasha et al. (Citation2017) identified an indirect relationship between transformational leadership and employees mission valence through performance management and goal clarity. In the context of Danish public sector organizations at different governance levels, Jensen, Moynihan and Salomonsen (Citation2018) identified a relationship between transformational leadership and employee mission valence when leaders share the vision via face-to-face dialogue. And in the context of a Canadian hospital Bosak et al. identified a direct relationship between transformational leaders and employees mission valence (2021). Finally, both a direct and an indirect (via goal clarity, PSM and work impact) relationship between top managers’ transformational leadership and employees’ mission valence has been identified in the context of Belgian social welfare organizations by Desmidt and Prinzie (Citation2019). Given the existing, albeit mixed, empirical findings of the relevance of transformational leadership to foster mission valence and given that both reputation management and transformational leadership are performing ‘visioning behavior’, we theorize and empirically investigate both reputation management and transformational leadership in relation to mission valence.

Transformational leadership—and mission valence

Transformational leadership was originally a multidimensional concept including idealized influence, individualized consideration, intellectual stimulation, and inspirational motivation (Burns Citation1978). In line with recent research on transformational leadership in public management research, we emphasize inspirational motivation and, hence, the visioning dimension of this leadership style (Caillier Citation2014; Jensen et al. Citation2019a, Citation2019b), defining transformational leadership as leadership behaviors with the intention to develop, share and sustain the vision of the organization (Jensen et al. Citation2019b:8).

The positive relationship between transformational leadership and mission valence is argued to be based on the mere ‘articulation of clear and attractive vision of the organization’s mission’ (Wright et al. Citation2012:207, italics in original) performed by transformational leaders; and as such based on the expectation that formulating, sharing and sustaining the vision renders the vision and the goals and values it reflects, attractive and desirable in themselves. When sharing and communicating the vision, public leaders, clarify the goals and the values of the organization, often reflecting the contribution which the organization makes to the broader society, enabling public employees to more clearly link their own values, goals and ultimately their behavior with the organizational vision (Desmidt and Prinzie Citation2019:667-668; Pasha et al. Citation2017:724). This in turn can foster the perceived attractiveness of the organization’s vision (Desmidt and Prinzie Citation2019:668). Additionally, this can enable aligning the often public service motivated public employees to see how they can contribute to society furthering the attraction to the vision (Caillier Citation2015). Based upon these theoretical arguments, we expect:

H1: Transformational leadership is positively related to employee’s mission valence.

Reputation management—and mission valence

Reputation management is a relatively new concept in public management research and few attempts have been made to define the management of organizational reputations in a public sector context (Maor Citation2015). While reputation management is often described as a reactive strategy in existing public management research on reputation (Pedersen and Salomonsen Citation2023), and as such primarily studied as responses to organizational threats, it can also be a proactive strategy pursued by organizations to convey the organizational identity and the organizational vision, and as such what the organization aspires to become and to be known for among external audiences (Carroll et al. Citation2018).

In this article, we argue that reputation management is the management of how external audiences perceive what the organization is, what it does and what it aspires to be. Reputation management is therefore defined as behavior with the intent to identify and affect external audiences’ perceptions of the organization (Pedersen and Salomonsen Citation2023:43).

Reputation management consists of three behaviors, being 1) identifying preexisting perceptions and expectations held by external audiences, 2) deciding which of these different audiences (and expectations) should be given priority, and 3) communicating the vision of the organization to these (specific) audiences’ (Pedersen and Salomonsen Citation2023:43).

Identification entails public managers to ‘hear, see and feel the public’ (Maor Citation2015:29) to enable them to “… more accurately gauging expectations regarding external demands placed on them” (Carpenter and Krause Citation2012:27). Identification as the first behavioral element takes places actively and continuously, to provide the necessary insights for the next two behavioral steps which presupposes that public managers know how different audiences perceives their organization as well as has insight into the expectations these audiences have for the organization.

The second behavioral element is prioritization, which, not least when performing reputation management, is a central public managerial task (Maor Citation2020:1046) given the multidimensional nature of a public organization’s audiences. Hence, a core challenge for public managers is that given different audiences may have different expectations to their organization, including how it should perform its tasks (Boon et al. Citation2019), satisfying a specific audience often involves, if not upsetting, then potentially disappointing others (Carpenter and Krause Citation2012:29).

The third behavioral element in reputation management is communicating which refers to efforts to convey the organization’s vision to external audiences to influence their perceptions (Elsbach, Citation2003), including the positive contribution the organization makes to society. Given that reputational beliefs and judgements reside in the perception of audiences, this third behavioral element is crucial in the formation of reputational beliefs (Pedersen et al. Citation2023:5; Pedersen and Salomonsen Citation2023).

Although, external communication performed as part of reputation management is mainly intended external audiences, it also involves an element of autocommunication (Christensen et al. Citation2018). Coined by Lotman (Citation1977), autocommunication theory suggests that all individuals, institutions, and cultures communicate with themselves, even when addressing other audiences (Lotman Citation1977). As such, when public managers communicate with external audiences, employees listen too. As noted by Morsing, without disregarding the interest of external stakeholders when it comes to receivers of external communication “…the theory of auto-communication indicates that organizational members are perhaps the most interested readers, which serves to establish and reinforce corporate self-images and corporate identities, i.e., reinforces belongingness and identification among organizational members.” (2006:175). This type of ‘self-talk’ where organizations via external communication confirm, recognize, and convey their values is particularly the case for mission and vision statements (Bartkus and Glassman Citation2008:209; see also Christensen, Citation1997:199). Hence, although reputation management is behavior with the intent to affect the perceptions of external stakeholders, it has the potential to define, shape and alter employee’s perceptions and affective orientations too. Therefore, external communication presents itself as yet another channel through which managers can communicate and share the vision with their employees, next to the repertoire of internal communication channels (Jensen et al. Citation2018).

Christensen et al. (Citation2018) actually argues that the presence of a potentially interested and attentive external audience increases the likelihood that a message is taken seriously by the organizational members. When an organization conveys important messages such as its vision externally, it lends status and authority to the message, and also obligates the organization itself to take the message seriously (Christensen Citation1995), expectedly adding to the credibility of the vision as a leader intention in the eyes of the employees (Jakobsen, Andersen and van Luttervelt Citation2022).

Autocommunication can build organizational identification among organizational members, and make employees more inclined to ‘feel as one’ with the organization (Mael and Ashforth Citation1992:103). This has been empirically demonstrated within communication research focussing among others on CSR communication (Morsing Citation2006), media communication (Kjærgaard and Morsing Citation2010) and brand communication (Kärreman and Rylander Citation2008). Communicating a brand is, as communicating a vision, a way in which managers are able to express the preferred values, and may as such act as “…a vehicle for management of meaning…” (Kärreman and Rylander Citation2008:107), which informs employees’ process of identifying who we are as an organization increasing the attractiveness of belonging to the organization that is their organizational identification (Kärreman and Rylander Citation2008:120). In a similar way we argue that reputation management and the external communication of the vision feeds into employees’ sense of and attraction not only to whom the organization is, but also to where the organization is heading, what is aspires to become and the contribution it makes to the broader society while realizing the vision.

Based upon the theory of autocommunication and the empirical studies identifying a relationship between external communication efforts (branding, media, and CSR) and employees’ organizational identification we expect reputation management to be positively related to employees’ mission valence. Both organizational identification and mission valence reside in the affective orientations of employees. While they differ in terms of organizational identification reflecting felt and experienced oneness with the organization as such, and mission valence reflecting felt attraction to the organizational vision more specifically, we do expect managers’ autocommunicative efforts also to stimulate positive emotional attraction to the vision among employees. Hence, we expect that:

H2: Reputation management is positively related to employee’s mission valence.

Research design, methods, and data

To examine the hypotheses, we employ a balanced panel research design of employees in three Danish government agencies, including two consecutive survey studies conducted in 2019 and 2020. In both studies, we sent the survey to approximately 900 employees in three Danish agencies. The overall response rates were 43% in 2019 and 45.33% in 2020, with some variations across the three agencies. As we investigate the same employees over time, the data used in the analyses are from respondents who completed both survey rounds. 193 employees completed both surveys, giving a 21.2% response rate for the balanced panel, which is an acceptable response rate for panel data. The drawback of this approach is that the statistical power is reduced. However, using repeated measures of the same employees hold at least two important advantages relative to the cross-sectional designs often used in public leadership research (Nielsen et al. Citation2019:419, Jensen et al. Citation2018). First, panel designs allow us to investigate changes in our focal constructs over time (e.g., did mission valence increase on average?) and relate such changes to changes in the perceptions of leadership and management behavior. This is relevant as we are interested in whether leaders can change employees’ attraction to the organizational vision. Second, and related, repeated measures of the same employees offers an analytical strategy that is less vulnerable to concerns regarding endogeneity resulting from, for example, situations where the behavior of the public managers is influenced by existing or prior employee mission valence or from non-observed variables affecting the theoretical concepts, we are interested in. Examining how changes in employee perceived leadership and management behavior is related to changes in employees mission valence enables us to study within-unit variation over time and allows us to account for both observed and unobserved time-invariant confounders. (Wooldridge Citation2020).

The three agencies were chosen based on their common features to create as much comparability as possible. We chose agencies with a primarily regulatory function, as reputation is argued to be of special importance for regulatory agencies (Carpenter, Citation2010; Overman et al. Citation2020:416). The three agencies are media-salient and have, relative to other agencies, experienced a high level of also negative media coverage prior to the surveys (Boon et al. Citation2019). As such, we expect their reputational awareness to be relatively high, which also means that managers within these agencies expectedly strive to perform extensive reputation management behavior. Following this, we consider the chosen agencies to be ‘most likely’ cases to find a relation between reputation management and employees’ mission valence.

The agencies are the Danish Veterinary and Food Administration (DVFA), the Danish Health Authority (DHA) and ‘Agency X’ (the latter asking to remain anonymous). All employees of the DHA and Agency X were invited to participate in the study, while we chose to conduct the study only among a sample of the DVFA employees: the employees working at the agency’s head office. The tasks performed by these employees are similar to those performed by the employees in the two other agencies, and the sample size from this agency is somewhat similar to the number of employees in each of the other two.

Data collection

Our data consist of two questionnaires distributed via e-mail to employees of the three agencies (1½ years between the two surveys). On 4 March 2019, the questionnaire was sent to all 181 active DHA employees, i.e., excluding employees who were on leave or otherwise absent for a longer period during the time of investigation, on 20 March 2019, the questionnaire was sent to 314 employees at Agency X, and the questionnaire was sent to 377 employees at the Danish Veterinary and Food Administration (DVFA) on 8 April 2019. In total, the first round of the survey was sent to 872 employees with a response rate (whole survey) of 43% (n = 373).

The second survey round was planned for exactly one year after the first survey. Due to the Covid-19 pandemic, however, the DHA questionnaire had to be postponed, and in agreement with the two remaining agencies, theirs too were postponed. Round 2 of surveys was thus distributed (again via e-mail) in September and October 2020 to the three agencies in the same order as Round 1. The second questionnaire was sent to a total of 919 employees with a response rate (whole survey) of 45.33% (n = 413). For an overview of all response rates see in appendix. Of the 193 employees answering both surveys 39.38% are from DVFA, 24.87% from DHA and 35.75% are from Agency X. Descriptive statistics concerning the background information of the respondents can be found in in the appendix.

Measures

All constructs were measured as latent variables. To the extent possible, we employed previously validated measures. Descriptive statistics for all constructs can be found in in the appendix, while correlations between all constructs are reported in also in the appendix. The measures for transformational leadership and mission valence have all been validated in existing studies and furthermore shown internal consistency in a Danish context (Jensen et al. Citation2018, Citation2019a, Citation2019b). The reputation management measure has been validated in Pedersen and Salomonsen (Citation2023). We measure transformational leadership and reputation management using employee ratings of their immediate manager because we know from previous studies that managers tend to overrate their own leadership and management relative to employees and that only employee-perceived leadership is positively related to organizational, including employee, outcomes (Jacobsen and Andersen 2015:829). All items were measured on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from ‘strongly agree’ to ‘strongly disagree’.

We measure reputation management using seven items developed in Pedersen and Salomonsen (Citation2023). The seven items reflect the three behavioral components of reputation management outlined in the theoretical section; that is, the managerial attempts to identify perceptions and expectations held by audiences, to prioritize between different audiences and their expectations, and lastly to communicate the organizational vision to these audiences (see in the appendix for item wording). To test the psychometric properties of the reputation management measure, we conducted confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) specifying a 3-factor model of identification, communication and prioritization. The estimation procedure is outlined in in the appendix. The CFA’s showed standardized factor loadings for the reputation management measure well above the lower recommended threshold (Acock Citation2013). As in Pedersen and Salomonsen (Citation2023), we found that a 3-factor model generally fits our data well and performs significantly better than less complex models (a model in which the items were constrained to load on two factors, identify and communicate as same factor, and a model where all items were constrained to load on a single factor). Additionally, as the CFA’s was conducted separately for each round, we are confident that a 3-factor model is the best fit for our data in both rounds. There are, however, a poor model fit to data in relation to the RMSEA for the CFA for round 2 as the RMSEA above the 0.08 threshold for a reasonably close fit (Acock Citation2013). This is possibly due to the small degrees of freedom under which RMSEA tends to falsely indicate a poor fit (Kenny, Kaniskan, and McCoach, Citation2015).

Even though the CFA’s showed similar loadings across rounds, we want to ensure that our respondents conceptually interpret our measure the same way in the two periods. Hence, we test for configural and metric invariance across time (Putnick and Bornstein Citation2016). We follow the procedure as Jensen et al. (Citation2019b). Firstly, we test for configural invariance by comparing a baseline model, i.e. a model with all parameters constrained to be equal across time, with a same form model, i.e. a model with the factor structure and pattern of loadings constrained to be equal across time. Secondly, to test for metric variance we compare the same form model with an equal loadings model, i.e. a model with the factor loadings constrained to be equal across time. The results of the invariance test are shown in in the appendix and the CFA’s used for the tests are available upon request.

By comparing the same form model with the baseline model, we find that a model without invariance constraints perform significantly better than a model, where all parameters are equal across time. Yet, the two models have the same factor structure, i.e. both models has the same factors loading at the same construct, and both fit the data well indicating configural invariance (Putnick and Bornstein Citation2016). Fit statistics for the baseline model and the same form model are respectively: χ2(46) = 115.28, p < .001 & χ2(22) = 70.50, p < .001, RMSEA = 0.088 & RMSEA = 0.107, CFI = 0.974 & CFI = 0.982, SMSR = 0.062 & 0.024. Moreover, we see that the equal loadings model does not perform significantly worse than the equal form model when testing the two models: χ2(4) = 2.83, p > .1, which indicates metric invariance. As the differences in the fit statistics when comparing the two models are quite small: ΔRMSEA = 0.010, ΔCFI = 0.000 and ΔSMSR = 0.006, we are confident that the respondents conceptually understand reputation management as the same concept in both rounds (Acock Citation2013). We generated a summative index of reputation management based on the three dimensions. That is, we created a summative index for each dimension and combined them into a single index, so that each dimension would have the same weight. Each dimension showed internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alphas well above the recommended 0.7 cutoff (Acock Citation2013). Finally, we rescaled the combined reputation management index to range from 0–1, 1 representing the maximum value.

To measure transformational leadership, we draw on four items developed by Jensen et al. (Citation2019a, Citation2019b) (see in the appendix for item wording). Cronbach’s alpha indicates internal consistency of items (0.95 in Round 1, 0.95 in Round 2). We generated a summative index for transformational leadership, giving equal weight to each item. We rescaled the index to range from 0–1, 1 representing the maximum value. As in Jensen et al. (Citation2019b), supplementary analysis showed configural and metric invariance across time for transformational leadership (these are available upon request).

Importantly, we wanted to ensure that the two constructs for public manager behavior, i.e. reputation management and transformational leadership, in fact measured two distinct constructs. Hence, for both rounds we included both constructs in the same CFA (see in the appendix) and found discriminant validity between the two constructs. Furthermore, in the CFA we analyzed the correlation between transformational leadership and reputation management (see in the appendix) and found that the two concepts are (highly) correlated, and the average variance extracted and shared variance are close to each other, suggesting that the two concepts are distinct but closely related in both rounds, which we would also expect theoretically (Pedersen and Salomonsen Citation2023). Yet, when constructing our measures as summative indexes the correlation is a bit lower (see ). Finally, to test for cross-loadings, exploratory factor analyses showed that the items only load strongly on the expected latent dimensions in both rounds (see in the appendix).

We measured mission valence using three items developed by Jensen et al. (Citation2018) based on Wright et al. (Citation2012) and Van Loon et al. (Citation2017) (see in the appendix for item wording). Cronbach’s alpha shows a reliability of items (0.64 in Round 1 and 0.74 in Round 2) just around the conventional standards. We created a summative index based on the three items and rescaled the index to range from 0–1.

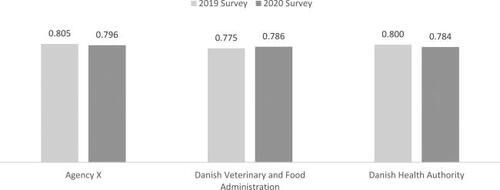

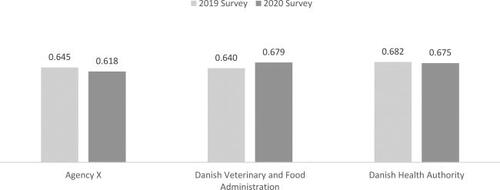

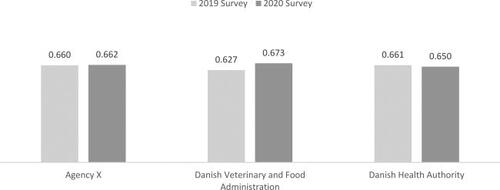

In order to illustrate how each agency rate the three constructs, in the appendix shows graphs with the mean value of respectably mission valence, transformational leadership and reputation management for each survey round.

Analytical strategy

The panel data design are very useful, since we are able to control for time-constant factors in our model, even if these factors might be correlated with the explanatory variables (Wooldridge Citation2020). We conduct our analysis at employee level using the Fixed Effect (FE) estimation meaning that we also eliminate the part of the measurement error that is constant within subjects. Furthermore, we apply cluster robust standard errors at the individual level to account for serial correlation in the idiosyncratic errors. We use three models to test our hypotheses and the equations are presented below:

Empirical findings

We first analyze model 1 and the relationship between transformational leadership and mission valence. In order to investigate the relationship between reputation management and mission valence we analyze model 2, before we in model 3 include both transformational leadership and reputation management in our regression (see below).

Table 1. Regression analyses of relationship between mission valence and transformational leadership, and mission valence and reputation management.

As proposed in the theoretical section, we expect that transformational leadership (H1) and reputation management (H2), respectively, are positively related to employee mission valence.

tests the hypotheses regarding the direct associations between transformational leadership and reputation management, respectively, and mission valence. In support of H1 and H2, the empirical results show that both transformational leadership (β = 0.120, p = 0.002) and reputation management (β = 0.150, p = 0.010) are positively related to mission valence. The means that mission valence on average increases with employee-perceived transformational leadership as well as with employee-perceived reputation management.

Due to the high degree of covariance between transformational leadership and reputation management, the analyses are run in separate models in model 1 and model 2. If transformational leadership and reputation management are included in the same model (model 3) the relationships are still positive, but with smaller coefficients, and not statistically significant. As one might could expect, the two leadership and management concepts do not explain enough unique variation to both be significant in the same model.

Yet, a subsequent test for joint significance showed that the two variables in model 3 are significant together: F (2, 192) = 5.27, p = 0.006. Looking at the size of the coefficient across the models, the coefficient for reputation management is larger than the coefficient for transformational leadership, i.e. both when comparing model 1 and model 2 but also in model 3. At the same time, it seems that the relationship between mission valence and transformational leadership is a bit stronger statistically than the relationship between mission valence and reputation management. In the next section we discuss the implication of our findings.

Discussion and conclusion

The ambition of the article has been to contribute to the public leadership and management literature concerned with mission valence, reputation management and transformational leadership.

Public employees who perceive the salience of the organizational vision and feels attracted to it are employees who “…are in charge of the organization’s purpose or social contribution…” (Vogel et al. Citation2023:1504), and combined with the beneficial relation mission valence have with other employee outcomes as well as performance, the renewed scholarly interest in public employee’s mission valence (Guerrero and Chênevert Citation2021:447) seems both timely and relevant for public management research and practices alike.

Relative to existing knowledge of how public managers can cultivate employee mission valence, the first and main contribution of the article is demonstrating that also reputation management is positively related to employees felt attraction to the organizational vision. This finding reflects the relevance of expanding our theoretical repertoire (Crosby and Bryson Citation2018:1277) in this case beyond transformational leadership when investigating how public managers can foster mission valence. Public managers can make their employees feel attracted to the organizational vision by performing other types of management and leadership than (just) transformational leadership. While the relevance of reputational aspects vis-à-vis external audiences’ mission valence has been demonstrated (Willems et al. Citation2021), our study points to the relevance of reputation management also for internal audiences’ mission valence, and as such relevant when public managers wish to make employees see ‘the intrinsic value’ (Wright Citation2007:60) and sense ‘the magnetic appeal’ (Goodsell Citation2011a:477) of the vision and become attracted to it.

We argue that autocommunication could be the mechanism through which public managers simultaneously convey the importance of the organizational vision to employees when they are actually aiming to communicate the message to external stakeholders.

As a second contribution, we further identify a positive direct relation between transformational leadership and mission valence, although not significant when reputation management is included in the analysis. Hence in the context of Danish regulatory agencies, public managers may foster mission valence directly via transformational leadership. In light of the additional recent similar finding of a direct relation between top managers’ transformational leadership behavior and employees’ mission valence in the context of Belgian social welfare organizations by Desmidt and Prinzie (Citation2019) this speaks to revising the existing assumption within public management literature, that “…transformational leadership does not have a direct relationship with mission valence but operates through other factors” (i.e., the indirect path) (Wright et al. Citation2012:212).

Turning to the practical implications of our study, the supplemental route to increasing employee mission valence by means of reputation management comes to the fore, and we suggest at least three rather immediate implications.

First, reputation management has mainly been seen as a management behavior thus far, primarily performed by manages at the upper echelons of the organization with the intent to affect external audiences’ perception (Cornelissen Citation2017). These efforts are generally considered challenging, as many other factors may affect such perceptions, including reputational intermediaries (Rindova and Martins Citation2012). Additionally, it has been recognized to be a type of behavior where the effect in terms of reputational judgements may have a long-term perspective. Our study points to the relevance of assessing the value of reputation management by managers across the managerial hierarchy, also in terms of its effect on employee outcome—even in a relatively short-term perspective, being in this study a year and a half.

Second, existing studies have shown that sharing the vision by transformational leaders via face-to-face dialogue to foster mission valence is conditioned by span of control (Jensen et al. Citation2018). This provides for a challenge when public managers have a larger span of control. Our study suggests that public managers faced with a relatively large span of control may explore the potential external communication holds in terms of simultaneously communicating to employees. As such our study speaks to the relevance of exploring alternative ways by which public managers can communicate the organizational vision to their employees. Also, of relevance given that virtual communication contexts, channels and media seems on the rise in both internal and external communication (Loyless Citation2023). This further suggests that the external communication of the organizational vision is a task of relevance for not only the executive levels of public organizations; but for all managers with employee responsibility to install the sense of attraction to the vision to, if not overcome, then supplement challenges associated with larger span of control.

Third, if employees also ‘listen’ when the vision is conveyed to external audiences, it becomes even more important for public managers to come across as credible (Kouzes and Posner Citation1990), or ‘authentic’ (Vogel et al. Citation2023) both internally and externally. Hence it becomes even more important to ensure alignment between public managers own values and the values promoted in the organizational vision (Vogel et al. Citation2023:1507) to ensure authenticity as well as alignment between public managers internal visioning behavior and their external ditto, based upon alignment of what public managers say they and their organization do and what they actually do to ensure credibility (Jakobsen, Andersen and van Luttervelt Citation2022).

Limitations and future research

Although our study contributes to the empirical research on reputation management, transformational leadership and mission valence, there are a number of limitations requiring attention.

First, we do not measure the theoretical mechanism of autocommunication empirically, which limits our understanding of the mechanisms in relation to the relationship between reputation management and mission valence. Given that external communication seems as a task of increasing importance for also public managers, we encourage future studies to investigate autocommunication as a mechanism per se as well as its potential effects on other types of employee outcomes.

Second, although our panel design is preferable to cross-sectional designs, there is still some risk of common source bias relating to the use of employee ratings of both independent and dependent variables, which possibly reduces the validity of our findings.

Third, our empirical investigation is limited to Danish agencies performing primarily regulatory tasks, and it is not given that the results can be extended to agencies performing other tasks or other types of organizations, let alone to public organizations in other national contexts. In addition, we see our agencies as most likely cases in terms of being public organization in which reputation management is given priority. Hence including public organizations where such reputation conscious behavior may be less likely would further add to testing the external validity of the findings presented here.

Fourth, although we have tried to choose agencies that are as comparable as possible, we acknowledge their differences and that we must be cautious about apples-to-apples comparisons between them, as well as being cautious about including different agencies in the same sample as interchangeable units of analysis, as argued by Carpenter (Citation2020).

Finally, the specific context in which the second survey round was conducted was influenced by the Covid-19 pandemic for especially the DHA and DVFA employees, which may have influenced the employees’ survey responses. Important next steps for scholars are thus to replicate the study in order to improve our understanding of the potential of reputation management in fostering mission valence. This could include studies in different organizations; countries and cultures; applying measures of autocommunication to validate empirically the theoretical mechanism suggested in the article in order to move the emerging research agenda on the relationship between reputation management and employee outcomes even further.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Mette Østergaard Pedersen

Mette Østergaard Pedersen is international Advisor at the Danish Customs Agency. She has a Ph.D. in management, on the topics on reputation and reputation management in the public sector. She has published on these topics in Perspectives on Public Management and Governance, as well as contributed to Blind Spots of Public Bureaucracy and the Politics of Non-coordination, (Palgrave Macmillan)

Daniel Skov Gregersen

Daniel Skov Gregersen’s is employed at King Fredriks Center for Public Leadership at the Department of Political Science, Aarhus University. His research interests include public leadership and employee outcomes. He has published on these topics in International Public Management Journal.

Heidi Houlberg Salomonsen

Heidi Houlberg Salomonsen is Professor in Public Management at the Department of Management, Aarhus University, Denmark. Her research interests include public management and leadership, core executives, relationships between top civil servants, ministers and political advisers as well as reputation in the public sector. She has published on those topics in journals such as Public Administration, Public Administration Review, Journal of Public Administration Theory and Research, as well as Regulation and Governance

References

- Acock, A. C. 2013. Discovering Structural Equation Modelling Using Stata. Rev. ed. College Station, TX: Stata Press.

- Bartkus, B. R., and M. Glassman. 2008. “Do Firms Practice What They Preach? The Relationship between Mission Statements and Stakeholder Management.” Journal of Business Ethics 83(2):207–16. doi:10.1007/s10551-007-9612-0.

- Boon, J., H. H. Salomonsen, K. Verhoest, and M. Ø. Pedersen. 2019. “Media and Bureaucratic Reputation: Exploring Media Biases in the Coverage of Public Agencies.” Pp. 171–92 in The Blind Spots of Public Bureaucracy and the Politics of Non-Coordination, edited by T. Bach and K. Wegrich. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Bosak, J., S. Kilroy, D. Chênevert, and P. C. Flood. 2021. “Examining the Role of Transformational Leadership and Mission Valence on Burnout among Hospital Staff.” Journal of Organizational Effectiveness: People and Performance 8(2):208–27. doi:10.1108/JOEPP-08-2020-0151.

- Broms, H., and H. Gahmberg. 1983. “Communication to Self in Organizations and Cultures.” Administrative Science Quarterly 28(3):482–95. doi:10.2307/2392254.

- Burns, J. M. 1978. Leadership. New York, NY: Harper and Row.

- Caillier, J. 2015. “Towards a Better Understanding of Public Service Motivation and Mission Valence in Public Agencies.” Public Management Review 17(9):1217–36. doi:10.1080/14719037.2014.895033.

- Caillier, J. 2016. “Do Transformational Leaders Affect Turnover Intentions and Extra-Role Behaviors through Mission Valence?” The American Review of Public Administration 46(2):226–42. doi:10.1177/0275074014551751.

- Caillier, J. G. 2014. “Towards a Better Understanding of the Relationship between Transformational Leadership, Public Service Motivation, Mission Valence and Employee Performance: A Preliminary Study.” Public Personnel Management 43(2):218–39. doi:10.1177/00910260145284.

- Carpenter, D. 2001. The Forging of Bureaucratic Autonomy: Reputations, Networks, and Policy Innovation in Executive Agencies 1862–1928. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Carpenter, D. 2010. Reputation and Power: Organizational Image and Pharmaceutical Regulation at the FDA. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Carpenter, D. 2020. “On Categories and the Countability of Things Bureaucratic: Turning From Wilson (Back) to Interpretation.” Perspectives on Public Management and Governance 3(2):83–93. doi:10.1093/ppmgov/gvz025.

- Carpenter, D., and G. A. Krause. 2012. “Reputation and Public Administration.” Public Administration Review 72(1):26–32. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6210.2011.02506.x.

- Carroll, C. E., R. L. Heath, and W. Johansen. 2018. “Reputation Management.” Pp. 1–8 in The International Encyclopedia of Strategic Communication, edited by R. L. Heath and W. Johansen. Hoboken, USA: John Wiley and Sons. doi:10.1002/9781119010722.iesc0149.

- Christensen, L. T. 1995. “Buffering Organizational Identity in the Marketing Culture.” Organization Studies 16(4):651–72. doi:10.1177/0170840695016004.

- Christensen, L. T. 1997. “Marketing as Auto-Communication.” Consumption, Markets and Culture 1(3):197–227. doi:10.1080/10253866.1997.9670299.

- Christensen, T., and Å. Gornitzka. 2019. “Reputation Management in Public Agencies: The Relevance of Time, Sector, Audience, and Tasks.” Administration & Society 51(6):885–914. doi:10.1177/0095399718771.

- Christensen, L. T., R. L. Heath, and W. Johansen. 2018. “Autocommunication.” Pp. 1–6 in The International Encyclopedia of Strategic Communication, edited by R. L. Heath and W. Johansen. Hoboken, USA: John Wiley and Sons. doi:10.1002/9781119010722.iesc0010.

- Cornelissen, J. 2017. Corporate Communication. A Guide to Theory and Practice. Los Angeles, CA: Sage

- Crosby, B. C., and J. M. Bryson. 2018. “Why Leadership of Public Leadership Research Matters: And What to Do about It.” Public Management Review 20(9):1265–86. doi:10.1080/14719037.2017.1348731.

- Desmidt, S., and A. Prinzie. 2019. “Establishing a Mission-Based Culture: Analyzing the Relation between Intra-Organizational Socialization Agents, Mission Valence, Public Service Motivation, Goal Clarity and Work Impact.” International Public Management Journal 22(4):664–90. doi:10.1080/10967494.2018.1428253.

- Doering, H., J. Downe, H. Elraz, and S. Martin. 2021. “Organizational Identity Threats and Aspirations in Reputation Management.” Public Management Review 23(3):376–96. doi:10.1080/14719037.2019.1679234.

- Elsbach, K. D. 2003. “Organizational Perception Management.” Research in Organizational Behavior 25:297–332. doi:10.1016/S0191-3085(03)25007-3.

- Goodsell, C. T. 2011a. “Mission Mystique: Strength at the Institutional Center.” The American Review of Public Administration 41(5):475–94. doi:10.1177/0275074011409566.

- Goodsell, C. T. 2011b. Mission Mystique: Belief Systems in Public Agencies. Washington, DC: CQ Press.

- Guerrero, S., and D. Chênevert. 2021. “Municipal Employees’ Performance and Neglect: The Effects of Mission Valence.” Review of Public Personnel Administration 41(3):447–65. doi:10.1177/0734371X19896013.

- Hameduddin, T. 2021. “Employee Engagement Among Public Employees: Exploring the Role of the (Perceived) External Environment.” The American Review of Public Administration 51(7):526–41. doi:10.1177/02750740211010346.

- Hameduddin, T., and L. Shinwoo. 2021. “Employee Engagement among Public Employees: Examining the Role of Organizational Images.” Public Management Review 23(3):422–46. doi:10.1080/14719037.2019.1695879.

- Jacobsen, C. B., and L. Bøgh Andersen. 2015. “Is Leadership in the Eye of the Beholder? A Study of Intended and Perceived Leadership Practices and Organizational Performance.” Public Administration Review 75(6):829–41. doi:10.1111/puar.12380.

- Jakobsen, M. L. F., L. B. Andersen, and M. P. van Luttervelt. 2022. “Theorizing Leadership Credibility: The Concept and Causes of the Perceived Credibility of Leadership Initiatives.” Perspectives on Public Management and Governance 5(3):243–54. E-print advance access doi:10.1093/ppmgov/gvac009.

- Jensen, U. T., L. B. Andersen, L. L. Bro, A. Bøllingtoft, T. L. M. Eriksen, A. Holten, C. B. Jacobsen, J. Ladenburg, P. A. Nielsen, H. H. Salomonsen, et al. 2019b. “Conceptualizing and Measuring Transformational and Transactional Leadership.” Administration & Society 51(1):3–33. doi:10.1177/0095399716667.

- Jensen, U. T., L. B. Andersen, and C. B. Jacobsen. 2019a. “Only When we Agree! How Value Congruence Moderates the Impact of Goal-Oriented Leadership on Public Service Motivation.” Public Administration Review 79(1):12–24. doi:10.1111/puar.13008.

- Jensen, U. T., D. Moynihan, and H. H. Salomonsen. 2018. “Communicating the Vision: How Face-to-Face Dialogue Facilitates Transformational Leadership.” Public Administration Review 78(3):350–61. doi:10.1111/puar.12922.

- Kärreman, D., and A. Rylander. 2008. “Managing Meaning through Branding—The Case of a Consulting Firm.” Organization Studies 29(1):103–25. doi:10.1177/0170840607084573.

- Kenny, D. A., B. Kaniskan, and D. B. McCoach. 2015. “The Performance of RMSEA in Models with Small Degrees of Freedom.” Sociological Methods & Research 44:486–507. doi.org/10.1177/0049124114543.

- Kjærgaard, A., and M. Morsing. 2010. “Strategic Auto-Communication in Identity—Image Interplay: The Dynamics of Mediatizing Organizational Identity.” Pp. 93–111 in Media, Organizations and Identity, edited by L. Chouliaraki and M. Morsing. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Kouzes, J. M., and B. Z. Posner. 1990. “The Credibility Factor: What Followers Expect From Their Leaders.” Management Review 79(1):29.

- Lee, D., and Y. Zhang. 2021. “The Value of Public Organizations’ Diversity Reputation in Women’s and Minorities’ Job Choice Decisions.” Public Management Review 23(10):1436–55. doi:10.1080/14719037.2020.1751253.

- Lotman, Y. M. 1977. “Two Models of Communication.” Pp. 99–101 in Soviet Semiotics: An Anthology, edited by D. P. Lucid. London: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Loyless, L. H. 2023. “Competence in Virtual Communication: Remote Transformational Leadership.” Public Administration Review 83(3):702–9. doi:10.1111/puar.13618.

- Mael, F., and B. E. Ashforth. 1992. “Alumni and Their Alma Mater: A Partial Test of the Reformulated Model of Organizational Identification.” Journal of Organizational Behavior 13(2):103–23. doi:10.1002/job.4030130202.

- Maor, M. 2015. “Theoretizing Bureaucratic Reputation” Pp. 17–36 in Organizational Reputation in the Public Sector, edited by A. Wæraas and M. Maor. New York: Routledge.

- Maor, M. 2016. “Missing Areas in the Bureaucratic Reputation Framework.” Politics and Governance 4(2):80–90. doi:10.17645/pag.v4i2.570.

- Maor, M. 2020. “Strategic Communication by Regulatory Agencies as a Form of Reputation Management: A Strategic Agenda.” Public Administration 98(4):1044–55. doi:10.1111/padm.12667.

- Maor, M., and R. Sulitzeanu-Kenan. 2015. “Responsive Change: Agency Output Response to Reputational Threats.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 26(1):muv001. doi:10.1093/jopart/muv001.

- Morsing, M. 2006. “Corporate Social Responsibility as Strategic Auto-Communication: On the Role of External Stakeholders for Member Identification.” Business Ethics: A European Review 15(2):171–82. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8608.2006.00440.x.

- Moschella, M., and L. Pinto. 2019. “Central Banks’ Communication as Reputation Management: How the Fed Talks under Uncertainty.” Public Administration 97(3):513–29. doi:10.1111/padm.12543.

- Moynihan, D., S. Pandey, and B. Wright. 2014. “Transformational Leadership in the Public Sector: Empirical Evidence of Its Effects” Pp. 87–104 in Public Administration Reformation: Market Demand from Public Organizations. New York and London: Routledge.

- Nielsen, P. A., S. Boye, A.-L. Holten, C. B. Jacobsen, and L. B. Andersen. 2019. “Are Transformational and Transactional Types of Leadership Compatible? A Two-Wave Study of Employee Motivation.” Public Administration 97(2):413–28. doi:10.1111/padm.12574.

- Overman, S., M. Busuioc, and M. Wood. 2020. “A Multidimensional Reputation Barometer for Public Agencies: A Validated Instrument.” Public Administration Review 80(3):415–25. doi:10.1111/puar.13158.

- Pasha, O. Q., T. H. Poister, B. E. Wright, and J. C. Thomas. 2017. “Transformational Leadership and Mission Valence of Employees: The Varying Effects by Organizational Level.” Public Performance & Management Review 40(4):722–40. doi:10.1080/15309576.2017.1335220.

- Pedersen, M. Ø., and H. H. Salomonsen. 2023. “Conceptualizing and Measuring (Public) Reputation Management.” Perspectives on Public Management and Governance 6(1):40–53. doi:10.1093/ppmgov/gvac023.

- Pedersen, M. Ø., K. Verhoest, and H. H. Salomonsen. 2023. “How is Reputation Management by Regulatory Agencies Related to Their Employees’ Reputational Perception?” Regulation & Governance. Advance online publication. doi:10.1111/rego.12574.

- Putnick, D. L., and M. H. Bornstein. 2016. “Measurement Invariance Conventions and Reporting: The State of the Art and Future Directions for Psychological Research.” Developmental Review: DR 41:71–90. doi:10.1016/j.dr.2016.06.004.

- Rainey, H. G., and P. Steinbauer. 1999. “Galloping Elephants: Developing Elements of a Theory of Effective Government Organizations.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 9(1):1–32. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.jpart.a024401.

- Resh, W. G., J. D. Marvel, and B. Wen. 2018. “The Persistence of Prosocial Work Effort as a Function of Mission match2.” Public Administration Review 78(1):116–25. doi:10.1111/puar.12882.

- Rindova, V. P., and L. L. Martins. 2012. “Show Me the Money: A Multidimensional Perspective on Reputation as an Intangible Asset.” Pp. 16–33 in Oxford Handbook of Corporate Reputation, edited by T. G. Pollock and M. L. Barnett. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Selznick, P. 1957. Leadership in Administration: A Sociological Interpretation. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Stritch, J. M. 2017. “Minding the Time: A Critical Look at Longitudinal Design and Data Analysis in Quantitative Public Management Research.” Review of Public Personnel Administration 37(2):219–44. doi:10.1177/0734371X1769711.

- van Loon, N. M., W. Vandenabeele, and P. Leisink. 2017. “Clarifying the Relationship between Public Service Motivation and in-Role and Extra-Role Behaviors: The Relative Contributions of Person–Job and Person–Organization Fit.” The American Review of Public Administration 47(6):699–713. doi:10.1177/0275074015617.

- Vogel, R., D. Vogel, and A. Reuber. 2023. “Finding a Mission in Bureaucracies: How Authentic Leadership and Red Tape Interact.” Public Administration 101(4):1503–25. doi:10.1111/padm.12895.

- Wæraas, A., and D. Y. Dahle. 2020. “When Reputation Management is People Management: Implications for Employee Voice.” European Management Journal 38(2):277–87. doi:10.1016/j.emj.2019.08.010.

- Wei, Y., Y. Guo, and J. Su. 2021. “Dancing on a Tightrope: The Reputation Management of Local Governments in Response to Public Protests in China.” Public Administration 99(3):547–62. doi:10.1111/padm.12699.

- Willems, J., L. Faulk, and S. Boenigk. 2021. “Reputation Shocks and Recovery in Public-Service Organizations: The Moderating Effect of Mission Valence.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 31(2):311–27. doi:10.1093/jopart/muaa041.

- Wooldridge, J. M. 2020. Introductory Econometrics: A Modern Approach. 7th ed. Boston, MA: Cengage.

- Wright, B. 2007. “Public Service and Motivation: Does Mission Matter?” Public Administration Review 67(1):54–64. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6210.2006.00696.x.

- Wright, B. E., D. P. Moynihan, and S. K. Pandey. 2012. “Pulling the Levers: Transformational Leadership, Public Service Motivation, and Mission Valence.” Public Administration Review 72(2):206–15. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6210.2011.02496.x.

- Wright, B. E., and S. K. Pandey. 2011. “Public Organizations and Mission Valence: When Does Mission Matter?” Administration & Society 43(1):22–44. doi:10.1177/0095399710386303.

Appendices tables

Figure A2. Transformational Leadership (Means), Balanced Panel (n = 193).

Note: Index scaled from 0-1

Table A1. Response rates.

Table A2. Descriptive statistics for background information (round 1).

Table A3. Descriptive statistics for constructs (panel).

Table A4. Correlations.

Table A5. Confirmatory factor analyses reputation management, Round 1.

Table A6. Confirmatory factor analyses reputation management, Round 2.

Table A7. Test for measurement invariance across time (round 1 and round 2).

Table A8. Full confirmatory factor analysis of reputation management (1 factor) and transformational leadership (1 factor) (employee perception of immediate manager).

Table A9. Intercorrelations and estimates for discriminant validity and reliability: Employee ratings of immediate manager (N = 193), first survey.

Table A10. Intercorrelations and estimates for discriminant validity and reliability: Employee ratings of immediate manager (N = 193), second survey.

Table A11. Exploratory factor analysis of transformational leadership and reputation management for immediate manager (N = 193).

Table A12. Exploratory factor analysis of mission valence (N = 193).