Abstract

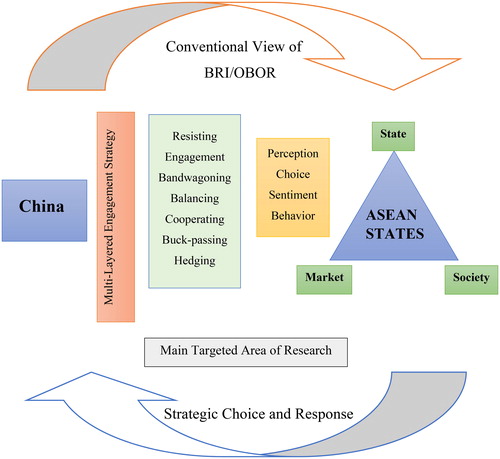

This special issue will propose that the changing relations among state-market-society in ASEAN’s states will play the crucial impact toward China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Under such circumstances, the changing state-market-society relations from internal and external impacts will reshape or modify their development strategy on China’s footprint in ASEAN by way of adopting balancing, bandwagoning, cooperating, or hedging consideration. The hedging strategical framework can be constructed and analyzed on each ASEAN’s country how to effectively deal with China’s economic and political involvement. It will be concerned that the hedging strategic framework is a combination of consideration on resisting, balancing, bandwagoning, and cooperating measures in order to efficiently and rationally deal with great powers like China, in different aspects and degrees. The application of general hedging framework is a kind of risk and benefit management strategy for ASEAN states toward China’s dominance on BRI that is smartly used by ASEAN states to pursue economic gains and to enjoy relative political autonomy at the same time.

This special issue will concentrate on four important conceptual concerns taken as a referent framework and structure. The first issue concern is the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) as development opportunity or trap? Does the BRI construct an economic win-win situation or an unequal economic sharing, or even a zero-sum game reality? The second issue concern is on a research view from ASEAN states’ side, not from the conventional stance of great power. Giving an alternative view departed from conventional international relations will be pinpointed to the perception and stance of relative, small, and weak states in response to BRI, which is somehow challenging to the great powers influences. The third issue concern is to construct a comprehensive framework of hedging strategy, internally and externally. How is the general hedging strategy formed and considered for responding to the great powers. The last issue concern is to have an approach and application of state-market-society interactions on the perception change and strategy choice for ASEAN’s states. All these issue concerns will be composed together into a major basic structure for guiding this special issue research.

I. The belt and road initiative as development opportunity or trap?

As known, People’s Republic of China (PRC) has released the ambitious development plans of the land-based “Silk Road Economic Belt” and the sea-based “21st Century Maritime Silk Road,” called the “Belt-and-Road Initiative” (BRI) by the end of 2013. China’s National Development and Reform Commission, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and Ministry of Commerce delivered and unveiled the “Vision and Actions on Jointly Building Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st Century Maritime Silk Road” on March 28, 2015 that is so called BRI Action Plan which is seen as Chinese version of Marshall Plan. Under such an action plan, it assumes that BRI will deliver the positive significance on regional economic cooperation. In fact, China’s reasons on the BRI are delivering the positive impacts for the regional and global economies. Recently, the BRI not only covers more than 120 countries spanning continents from Asia to Europe, Africa, and Latin America, but also withdraws much world-wide attention on economic opportunities.

Under the BRI, there are three main objects/purposes for China by means of using the multi-layered engagement. The first is to generate local supports for China’s economic and geo-strategic interests. The second is to promote the Chinese model of governance and economic development. The last is to advance the broader interests that include generating supports for the Communist Party of China (CPC) and its territorial claims in the South China Sea (Kyee, Citation2018).

Since 2013, via the view of great powers, the BRI has been treated as a grand strategy for implementing “China’s dream,” paving a path for China rise. The BRI has also linked with the “Walk-out Policy” in order to solve overproduction pressure and domestic market saturation. The BRI has aggressively implemented and invested big projects abroad on public infrastructure ignited by China’s state-own enterprises, such as high speed rail, train, highway, road, economic corridor, bridge, harbor, dam, special economic zone. For example, in ASEAN states, China invests East Coast Rail Link (ECRL) in Malaysia, JAVA High-Speed Rail in Indonesia, Sino-Thai Railway in Thailand, Kyaukpyu Deep Sea Port and Myitsone Dam in Myanmar, Lower Se San 2 Dam in Cambodia, Special Economic Zone in Vietnam. Eventually, the extension of investment and market on great infrastructure projects maintains China’s substantial growth as well as regional economic domination.

Economically, China’s Belt and Road Initiative plus Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) in the Southeast Asia has also been influential and impressive for investment and loans. The ASEAN market can fully serve for China’s economic extension and overproduction. Politically, the BRI also aims to counter against the American Rebalancing Asia Policy and even Indo-Pacific Strategy that were Obama’s and Trump’s Asia-Pacific strategy to maintain China’s regional security and sovereignty.

China and ASEAN states have enjoyed a very close economic relation and development on trade and investment since the year of 2000. Since the promotion of ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) has launched in December 2015, it becomes the third largest market in the world in terms of population. China-ASEAN bilateral trade amount has rapidly increased from US$8 billion in 1991 to US$472.2 billion in 2015 and almost up to US$600 billion in 2019. After China rising, ASEAN economies are also ascending. In 2020, China is the largest trade partner of ASEAN for almost 7 years while ASEAN enjoys the second largest trade partner of China in 2019, next to EU, but just exceeding USA.

Nevertheless, as acknowledged, the implementation of China’s BRI is not good enough for setting win-win consideration and cooperation with those countries along the routes. Those countries will increase their economic dependence on China’s investments, loans, and beyond their debt-burden responsibility. The over inflow of China’s capital, commodity, labor, service, investment, and technology into ASEAN countries has hampered ASEAN economic development. The worst recognition and perception of ASEAN countries regards BRI as a China’s grand policy and instruments only for its own interest pursuit, even emerging an unfair condition of economic exploitation and colonialism. China gains lot of national interests from BRI, while along-route countries, like ASEAN countries, get a heavy financial burden on debt and even create less job opportunities for local workers that are harmful for their economic development.

The so-called “debt diplomacy” (debt trap, distress, or crisis) has been frequently occurred, and perceived as negative effects on BRI from local societies. This worrisome debt crisis and economic exploitation enhances the sense of China’s economic invasion and escalates the fear of China’s colonialism. The ASEAN states somehow are afraid of losing their economic autonomy, independence, and even sovereignty. It may often raise a question: is China Colonizing Southeast Asia? Undoubtedly, this fear and worry will extend dissatisfaction and hostility under the rise of nationalism and patriotism on China’s BRI. The China-ization of ASEAN’s economy in terms of China’s economic invasion and overwhelming investment will bring a massive negative and frustrated perception for ASEAN societies.

II. A view from ASEAN’s side: challenging the view from great powers

This special issue will take ASEAN states as a leading subject rather than as an obedient and coordinated object on research. So many researches on BRI mainly focus on China’s investment capacity and its active role of regional economic involvement with all countries along the BRI routes. The China-centered considerations and approaches on BRI grand strategy have anchored in the regional or global development fields. Undoubtedly, the China factor on BRI has strongly developed and emphasized in the international relations and economies. Relatively, the standing point from the opposite side of subordinated members has been ignored and ruled out.

Besides, most of the critiques on BRI are still appearing controversial, on the one hand. On the other hand, it is also widely recognized that the BRI will shape the new paradigm of geo-political and economic situations around the world (Blanchard & Flint, Citation2017). Those views are often from the sides of great power or China that is usually ignoring the stance of small states or ASEAN’s states. Further speaking, it is less weight on the importance and response from the weaker states or ASEAN’s states on BRI.

Thus, what is special for this special issue is tending to emphasize more on the view of ASEAN states rather than from China’s glance at BRI development. It will be giving more concerns on ASEAN states’ perception and strategy toward China’s BRI. Also, taking the framework of state-market-society relations here intends to explain how will perception (positive or negative) changes directly or non-directly influence a nation’s strategic choice on BRI (as shown). The top of shows the conventional approach to explore how does China’s BRI affect the development and change of ASEAN’s states, while the bottom part indicates how do ASEAN states perceive and reply on China’s BRI based on strategic choice.

III. Applying the comprehensive framework on hedging strategy

The application of this special issue on hedging framework tends to be more dynamic, rather than static, analysis for ASEAN states’ perception formation and strategic choice in response to the extension of China’s BRI. Dynamic analysis for general hedging framework consists of two levels of interpretation on internal and external mechanism. It refers that the ASEAN states’ current hedging posture and behavior are closely associated to internal and external environment changes on China’s BRI. Internal dynamics on a nation can be affected by domestic crucial elements, such as perception, behavior, motivation, interaction, and calculation/rationality. Relatively, external dynamics for a nation will be highly impacted in relation to US-China trade disputes, outbreak of COVID-19 pandemic, the implementation of Indo-Pacific Alliance, exploitation with economic invasion, great powers’ competition and domination, nationalism against foreign powers, and South China Sea sovereignty conflict.

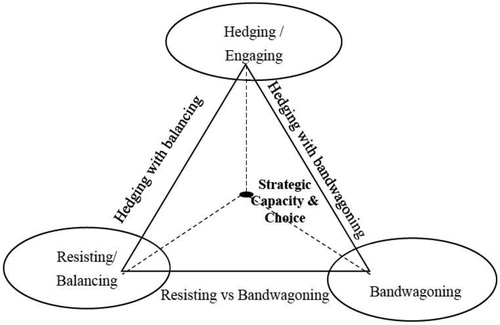

The general hedging framework is constructed as a dynamic process and decision on strategy formation. Several major strategic measures or instruments are considered and used as resisting, balancing, cooperating, engaging, bandwagoning, buck-passing, and hedging, in kind or in degree. The operational conceptualization on general hedging framework will no longer in kind take each/individual strategic instrument independently and exclusively with the others. Neither in degree places all instruments on a spectrum or an alignment between two extremes of resisting/balancing and bandwagoning (Kuik, Citation2016). In fact, it will be a combination and multi-layered engagement of those instruments for better hedging concerns in response to China’s BRI, such as hedging with balancing, hedging with bandwagoning, hedging with resisting, balancing with cooperating/engaging, or even balancing with bandwagoning.

The imaginative application of general hedging framework on strategic decision from three angels can be shown in . clearly indicates a triangular relation among resisting/balancing, bandwagoning, and hedging/engaging at the bases of perception, interaction, and rational choice. Hedging instruments become a part of general hedging framework and application. Hedging capacity can be simply expressed by free, autonomous, and flexible engagements within this comprehensive framework.

Figure 2. General framework on hedging strategy.

Source: drawn by author.

Note: Strategic capacity and choice is determined by interactions among hedging, resisting, balancing, cooperating, and bandwagoning on China’s BRI.

The strategic shift and formation is highly influenced by the changing perception, behavior, interaction, and profit between internal and external impacts on the weaker state from great powers. There are four major propositions on comprehensive framework of hedging strategy in order to refer the strategic behavior and choice. They are rational preference, risk-reduction, benefit maximization, and flexible engagement (autonomous choice). The basic concept on strategic selection is to increase autonomous capacity on balancing, on the one hand, and to minimize dependence on bandwagoning, on the other hand.

As a result, according to , general hedging framework, politically speaking, is losely linked to a state relative autonomy and independency on diplomatic, military, and political engagement and national sovereignty. In contrast, economically speaking, the general hedging framework is related to economic maximization on national benefits. Normally, the best hedging strategy is to gain political and economic interests as much as possible at the same time. Yet, as political interest conflicts with economic ones, a nation will evaluate and justify its preference, which interests should go first according to its internal and external situation. Broadly speaking, the general hedging framework is a strategic rational choice that works for the best and prepare the worst. This framework is also a consideration of both return-maximizing acts and risk-minimize control.

IV. Constructing a state-market-society analysis

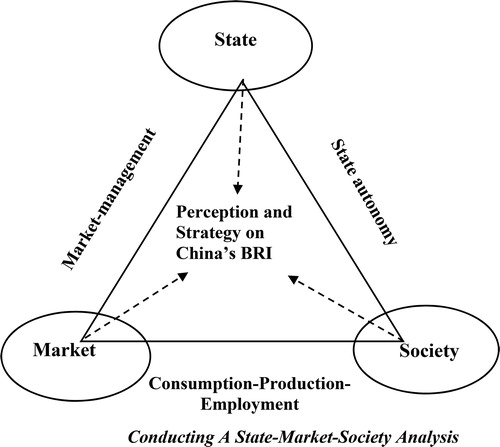

The analysis of State-Market-Society perspective is one of the comprehensive perspectives for assessing the developmental research as well as strategy selection. Indeed, the relations among the state, market and society are relevant to the formation of strategic choice (Zhiping, Citation1999, pp. 41–45). Even though state, market and society are so interlinked and overlapped each other, these three entities are still completely different from each other in terms of domain subjects and realms (Jessen, Citation2017a, Citation2017b). It is assumed that the state, market and society have three paradigms of national development, which has its own goals and purposes. The State is recognized as the first sector or paradigm, the Market as the second sector or paradigm, and the Society as the third sector or paradigm, as shown .

indicates that the perception and strategy will be formed by the changing relations and interests of each entity thru internal and external influences. The state has its own goal, ideology, policy preference, security, power, and interest, which always represents the perception and willingness of political elites and power leadership. The market has its own mechanism, function, management, trading, distribution, investment, and profit-seeking, which is highly concerned by commercial private sectors and enterprises. The society has also its own purpose and demand on human right, identity, interest, lifestyle, openness, justice, safety, and freedom, which is highly urged by civil society (Neocleous, Citation1996).

In dealing with China’s BRI, the response of the state policy consideration may be dependent on capital, investment, technology, and economic development. The focus of market will involve spontaneous actions on BRI among equal and private actors in order to acquire economic interest, rising production, and market openness. Society can be referred as the civil society and its perception on China’s BRI that will be more paid much attention on human right, freedom, sharing economy, job creation, national respect, economic invasion, and nationalism (Soong & Nguyen, Citation2018).

Even though society is interjected between market and state, the society is an entity, completely independent from politics and economic system. In addition, state legitimacy must derive from the support of civil society. However, the state perhaps enjoying higher relative autonomy from society can easily control societal collectivity. If not, the society will have a greater influence or challenge to state policy decision. In so doing, as long as ASEAN’s societies perceive a strong negative sense on China’s BRI, ASEAN’s states will be definitely irritated by rising nationalism and economic colonialism from society and in turn will implement a tougher policy against China’s BRI.

In sum, it will not only focus on the role of the ASEAN’s states toward China’s BRI in this special issue, but also the angles from market and society will be applied and emphasized. This means that state-centered approach is not the only actor dealing with China’s BRI in ASEAN, but market-oriented and society-centered approaches will be adopted in order to explore deeply and widely toward development reality. Furthermore, a national perception and strategy formation is not simply deriving from state reaction but also from market response and society return. As shown, the perception and strategy formation toward BRI is compounded of the reaction and interaction among state, market, and society with some mechanisms on market management, state autonomy, and production-consumption-employment. This approach will provide a very comprehensive interpretation of ASEAN states toward China’s BRI.

V. Final remarks: structure and arrangement of the special issue

Basically, the content of each article in this special issue will consider three parts for dealing with the perception and strategy of ASEAN’s states on China’s BRI. One, it examines the perception of ASEAN’s states on China’s footprints. Three aspects are deeply discussed as following: state view and policy purpose, people’s view and populist stance, capitalist view and its market consideration. Two, it further analyzes the strategy formation of ASEAN’s states toward China’s BRI. Several strategic approaches on balancing, resisting, cooperating, engaging, bandwagoning, and hedging will be analyzed and operated. Three, the possible linkage of perception and strategy toward China is elaborated and explored into several types, such as hedging with balancing, hedging with bandwagoning, hedging with resisting, or hedging combination. In sum, the insight of the development governance for a nation will be anchored on the perspective of state-market-society analysis in relation to general strategy of hedging.

Six articles are delicately contributed in this special issue based on the above approach framework, more or less, of strategic affirmation on ASEAN states’ decision on China’s BRI. The first article is titled as “Malaysia’s Perception and Strategy towards China’s BRI Expansion: Continuity or Change?” and written by Kok Fay Chin. The political economy analysis of Malaysia’s response to BRI expansion has shed light on the intertwining roles that the domestic forces and national leadership play in shaping the actual BRI process, implementation and outcome.

The second article is titled as “Myanmar’s Perception and Strategy towards China’s BRI Expansion on Three Major Projects Development: Hedging Strategic Framework with State-Market-Society Analysis” and written by Jenn-Jaw Soong and Kyaw Htet Aung. It marks that the State-Market-Society relations in relation to hedging strategic consideration in Myanmar will shape the new paradigm of China-Myanmar relations for the future. The political economy of Myanmar’s development should be multilateral and holistic approach, rather than dependence only on China.

The third article is titled as “Indonesia’s Perception and Strategy towards China’s OBOR Expansion: Hedging with Balancing” and written by Tirta Nugraha Mursitama and Yi Ying. It concludes that President Joko Widodo has demonstrated his leadership and ability to navigate Indonesia by implementing hedging strategy with nuanced of balancing rather than bandwagoning toward China.

The fourth article is titled as “the Philippines’ Perception and Strategy for China’s Belt and Road Initiative Expansion: Hedging with Balancing” and written by Wen-Chih Chao. It highlights that the Philippine state urges to promote economic and infrastructure developments and to eliminate security threats from China without the US’ support through participating China’s BRI. The Duterte administration neutralizes the effects of the pro-United States foreign policy by strongly cooperating with China in favor of maximum on national interest.

The fifth article is titled as “Vietnam’s Perceptions and Strategies towards China’s Belt and Road Initiative Expansion: Hedging with Resisting” and written by Van Hoa Vu, Jenn-Jaw Soong, and Khac Nghia Nguyen. It finds that Vietnam’s perceptions on the BRI have varied across the various social spectra. Vietnam’s strategies toward China’s BRI are a mixture of seemingly contradictory policies, which show either their supports (bandwagonig strategy) or denials (balancing strategy) or both simultaneously. Its hedging strategy toward BRI is a flexible hedging combination of both bandwagoning and balancing strategies.

The last article is titled as “Thailand’s Perception and Strategy towards China’s OBORI Expansion: Hedging with Cooperating” and written by Piratorn Punyaratabandhu and Jiranuwat Swaspitchayas. It reveals that various projects and cooperation in Thailand under BRI have not progressed much. Thailand has negative recognitions and comments against China’s BRI strategy as well as remarks of distrust of China with lack of confidence in China’s technology. Moreover, Thailand fears that China’s BRI is a plan to dominate Thailand.

References

- Blanchard, J.-M. F., & Flint, C. (2017). The geopolitics of China’s maritime silk road initiative. Geopolitics, 22(2), 223–245. https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2017.1291503

- Jessen, M. H. (2017a, January 26). Should civil society be political? The political role of civil society in light of the refugee crisis. DBP's Blog. The Department of Business and Politics, CBS. https://blog.cbs.dk

- Jessen, M. H. (2017b). The separation between state, market and civil society in capitalism: A Marxist approach to civil society in (neoliberal) capitalism. Denmark: Roskilde Universitet.

- Kuik, C.-C. (2016). How do weaker states Hedge? Unpacking ASEAN states’ alignment behavior towards China. Journal of Contemporary China, 25(100), 500–514. https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2015.1132714

- Kyee, K. K. (2018). China's multi-layered engagement strategy and Myanmar's reality: The best fit for Beijing's preferences. ISP Myanmar Working Paper Series, 1(1), 1–99.

- Neocleous, M. (1996). Administering civil society: Towards a theory of state power. Springer.

- Soong, J. J., & Nguyen, K. N. (2018). China’s OBOR Initiative and Vietnam’s political economy: Economic integration with political conflict. The Chinese Economy, 51(4), 342–355. https://doi.org/10.1080/10971475.2018.1457333

- Zhiping, L. (1999). Market, society, and the state. The Chinese Economy, 32(4), 41–45. https://doi.org/10.2753/CES1097-1475320441