Abstract

FDI flows in China have increased for decades, but the sectoral and country-origin distribution change over times. Chinese FDI inflows have experienced a shift from manufacturing to real estate and service sectors. A series of factors including labor cost increase, currency appreciation, overcapacity of production, domestic competition rise and US trade war cause negative effects on manufacturing FDI flows. However, rising purchasing power, consumer demand and market capacity create new opportunities for foreign business in China. The government makes efforts to nurture service trade as an engine of economic growth alongside trade in goods. Many incentive policies have been launched for numerous service industries. These are the push hand behind the rapid rise in service FDI. The neighboring countries or regions in Asia and free trade ports with taxation advantages contribute vast majority of the FDI in China. Hong Kong's status as the largest supplier of FDI to the mainland has become increasingly prominent over the past 20 years, partially due to so called “round-trip” FDI. Chinese economic diplomacy promotes regional integration in East and Southeast Asia, and creates conditions for the liberalization of intra-regional investment. Closer trade connections with European countries boost the EU investment in China over recent years. Our studies of FDI's structural changes in China can generate policy implications widely for the government, foreign companies and investors, as well as developing countries committed to FDI attraction.

1. Introduction

Massive FDI and multinationals' entry boost the industrial development in China. The spillover effect of FDI on Chinese economy have much valued by scholars (Fan et al., Citation2019; Hu et al., Citation2020; Kim & Xin, Citation2021). But as time goes, Chinese domestic industrial environment or market ecology can influence subsequent FDI flows as well. A country’s trade advantage may be not solely determined by its natural resources, labor force, interest rate, and exchange rate as claimed by the traditional international trade theory simply, but by its industrial innovation and upgrading capability to a greater extent. The diamond theory (Porter, Citation1986, Citation1998) regards related and supporting industries as an important variable of a country’s comparative advantage, which involves factor conditions for production, demand conditions and firm strategy. Industrial advantages are considered to be a major reason for FDI flows and the key to regional competitiveness of capital attraction and retaining (Cui et al., Citation2020). The uniqueness of China is that it is an emerging, transforming and growing market. Advantages at multiple levels, such as relatively lower production cost, rising market capacity and expanding industry system, compose the national competitiveness in FDI attraction. Over the development process, the growth of certain industries and rising competitiveness may have affected the decision-making of foreign companies for investing China. At the same time, after China joined the WTO, more fields and industries have opened for foreign investment, and some mandatory regulations are lifted gradually. This motivates foreign capital to put in emerging industries and obtain the opportunity as early birds. China is not a passive recipient of foreign investment. Instead, the government spares no effort to maintain economic sovereignty and finance security. Through the Catalogue and Negative List for Guiding Foreign Investment Industries, Chinese policies claim the industries encouraged for FDI access. Generally, that is to encourage high-tech or innovative FDI but restrict investment in high-pollution and energy-intensive industries. Multinationals' investments are given the expectation by authorities to push Chinese industrial transformation and sustainable development. On the other hand, foreign companies are also likely to take advantage of Chinese industries and cluster benefits. Nowadays, China has established an all-rounded industrial system, and some manufacturing fields achieve technical leading status worldwide. Many multinationals set up R&D centers in China, and brings a round of FDI engaged in innovation activities.

Chinese economic development and market prosperity have attracted global attention in the century. Increasing number of entrepreneurs from all over the world come to invest and start businesses in China. Beyond productive factories, multinationals are setting up many branches and agencies to operate Chinese market. Various forms of trade in goods or services are being extensive with the engagement of foreign companies. The friendly institutional environment is a push power for cross-border commerce. In the official level, China practice economic diplomacy actively and built bilateral or multilateral free trade and investment agreements with more countries. The state has reconstructed its own institutional functions and reset dedicated agencies for investment promotion. They are committed to providing professional, transparent and all-rounded investment services for overseas entrepreneurs and corporates, as well as the publicity of Chinese regulation and favorable policies for doing business. Sino-foreign industrial parks and inter-state cooperative projects have been widely carried out for decades. This makes the work of attracting investment more efficient and targeted, and secure the stable FDI flows. Chinese FDI origin has composed a global network, covering Europe, America and many neighboring countries in Asia. The country-origin of FDI reflects Chinese international relations. The instability of international politics and some inherent or stubborn cognitions may affect the inter-annual changes of FDI in China. In seek of local knowledge and cost reduction for information access, foreign investors tend to co-locate with common-background FDI firms and cause country-of-origin agglomeration (Tan & Meyer, Citation2011; Wang et al., Citation2009). Inter-regional links in ethnic, culture and history may play a role in the FDI of specific origins (Gani & Scrimgeour, Citation2019; Wang et al., Citation2020). At the same time, political factors like state visits, presidential marketing and inter-government cooperative mechanism can lead to trade promotion and investment waves (Beaulieu et al., Citation2020), while negative ones like trade sanctions and commodity boycotts may bring inverse consequence suddenly (Kong, Citation2022).

Sector and origin distributions are important aspects of the composition of FDI flows. This not only affects the business judgment and investment tendency of multinationals, but also the host country's trade policy. International capital always flows to sectors or industries of certain countries which can generate profitable returns. The investment behavior of multinational giants may induce a domino effect of more companies to follow suit. Likewise, advanced countries' capital flow (e.g., the UK and US) are often indicative and can influence investment decisions of their partners. Scholars have noticed the rapid growth of FDI to China in the past two decades, but the structural changes at the sectoral and source levels are known little. Empirical studies based on econometric models can prove the influencing factors in a certain period. But some deeper reasons, especially non-financial factors that transcend economic scope, remain to be clarified. In fact, multiple dimensions of driving forces have affected FDI flows in Chinese context. They are difficult to assess quantitively within a single framework. On the one hand, their mechanisms of action intersect or overlap each other, so cannot be simply tested together. On the other hand, some crucial factors such as state policies, financial regulation and international trade relations are impossible to be measured accurately. We examine the sectoral and country-origin dynamics of FDI in China, against the backdrop of sustained and substantial growth over the past two decades. The longitudinal analysis involves many aspects closely related to FDI in the Chinese context, such as economic development, state policies, international trade relations and financial system. Our research will deepen the understanding of FDI's structural changes in China. It can cause broad policy implications for the Chinese government, foreign companies and investors, as well as developing countries committed to FDI attraction.

2. Patterns of FDI sectors and source-countries or regions

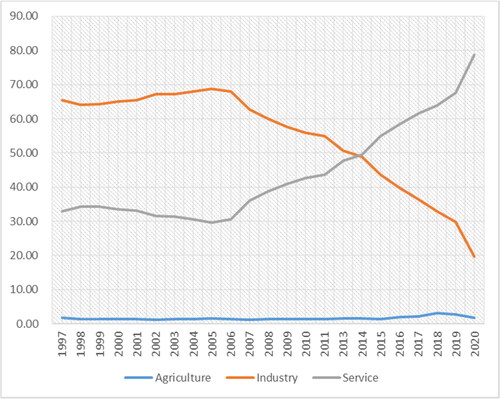

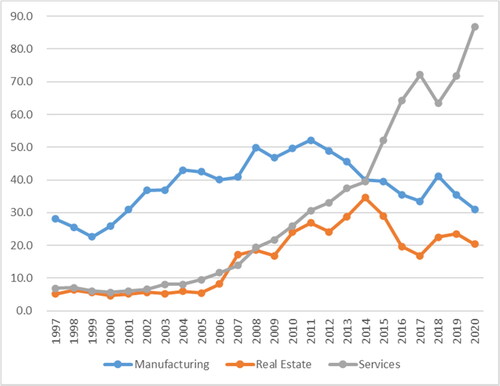

The vast majority of Chinese FDI inflows were into the manufacturing sector until the early 2010s ( and ). Manufacturing FDI contributes a lot to Chinese economic take-off. Alongside driving employment and tax creation, manufacturing FDI refreshes the country to a vigorous economic entity connected with international production networks from an originally closed system, as well as an important part of the global value chain. In particular, China's access to WTO has strengthened the production networks in developing countries (Aichele & Heiland, Citation2018; Zhang, Citation2007). Foreign invested enterprises have grown as an important subpart of Chinese national economy. They generate more than half of Chinese imports and exports, over one-fifth GDP and nearly half of the growth (Whalley & Xian, Citation2010). FDI is a key driver of the export capacity and competitiveness of Chinese manufacturing (Sun, Citation2012; Tang & Zhang, Citation2016; Zhang, Citation2015). The manufactured exports have strengthened the domestic supply chains and the linkage of related industries. The substitution of domestic for imported materials by processing exporters has caused an increase of Chinese domestic content in exports in the first decade of the century (Kee & Tang, Citation2016).

Figure 1. FDI inflow of major sectors since the late 1990s (unit: billion USD).

Data source: CHINA STATISTICAL YEARBOOK, National Bureau of Statistics of China

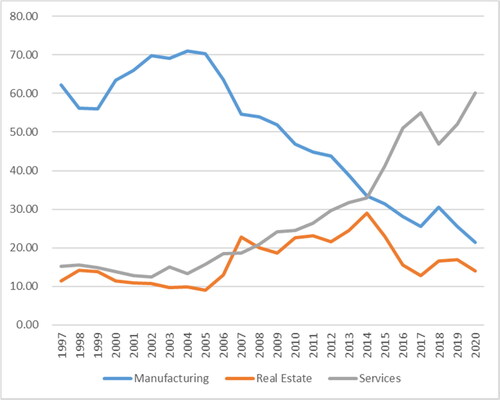

Figure 2. FDI proportion of major sectors in the annual total (unit: 100%).

Data source: CHINA STATISTICAL YEARBOOK, National Bureau of Statistics of China

Entering the 2010s, FDI in services has poured into China with unstoppable momentum. The stock and annual flow both surpass manufacturing FDI ever since 2014 (). Meanwhile, Chinese urbanization and large-scale infrastructure construction make real estate become a high profitable business. It triggers a continuous growth of real estate FDI until the mid-2010s (). Although it drops after that, real estate remains an investment filed that attracts more than 10% FDI inflows (). Service FDI has grown into the major driving force of FDI increase in China. More FDI are flowing into numerous service industries of China. It reshapes the FDI landscape, and leads to the sectoral diversification of foreign capital and corporates in China (). Chinese service sectors are absorbing FDI dividends and show broad growth prospects. It produces positive effects on the service export sophistication of China (Huang & Chen, Citation2014). The increasing FDI involved in services can increase the market competition. It will influence domestic service firms, and push them to adjust operation strategy for higher service quality (Tang et al., Citation2021). Chinese indigenous firms can get benefits from the entry of foreign services suppliers, and result in raising export product quality (Hayakawa et al., Citation2020; Latorre et al., Citation2018).

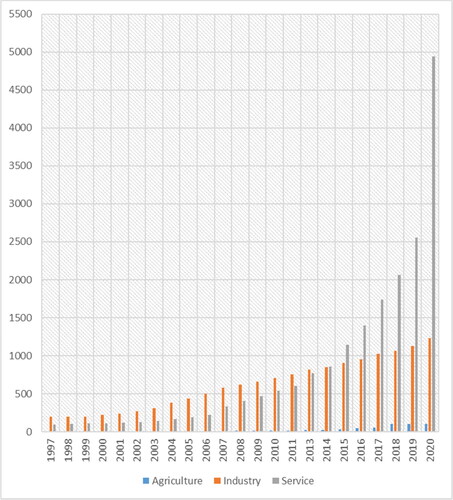

Figure 3. FDI stock by the three sectors in values over 1997-2020 (unit: billion USD).

Data source: CHINA STATISTICAL YEARBOOK, National Bureau of Statistics of China

Note: The agriculture (primary) sector includes planting, forestry, animal husbandry and fishery; the industry (secondary) sector includes mining, manufacturing, energy production and supply and construction; The service (tertiary) sector refers to other industries excluding the primary and secondary sector. The FDI stock is measured by the registered capital (foreign investors) of foreign-funded enterprises in China. Data for 2012 are missing.

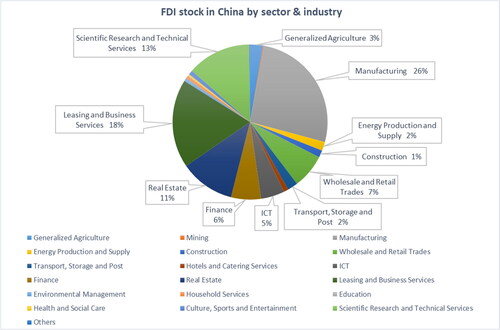

Figure 5. FDI stock in China by sector & industry as the end of 2019.

Data source: CHINA STATISTICAL YEARBOOK, National Bureau of Statistics of China

Note: The FDI stock is measured by the registered capital (foreign investors) of foreign-funded enterprises in China. ICT is abbreviation of information and communications technology (or technologies) that refers to infrastructure and components that enable modern computing.

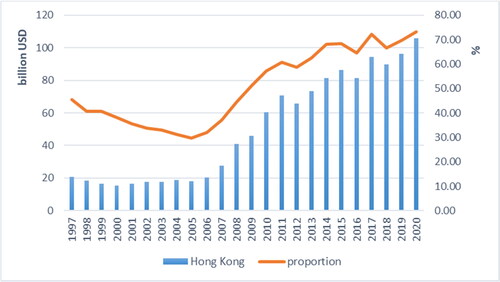

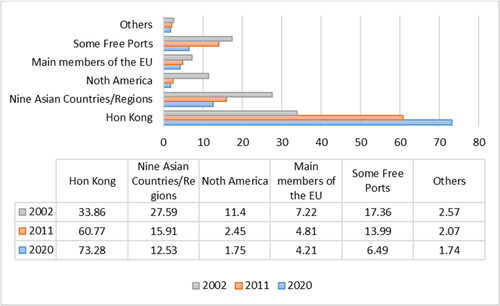

The vast majority of China's FDI comes from the neighboring East and Southeast Asia regions as well as some free ports with the role of offshore financial center. Hong Kong plays a pivotal role in the stabilization and growth of China's FDI inflows (). The role of Hong Kong's financial function is increasingly prominent in the past two decades. At the beginning of this century, around one-third FDI to China are through Hongkong. However, in the late 1990s and early 2000s, there was even a down-ward trend of Hong Kong’s FDI (). The 1997 Asian financial crisis hit Southeast Asia, Japan, and South Korea severely, and caused a regional economic recession lasting for several years. The Hong Kong stock and forex market were also volatile, disrupting financial stability. Entering 2010s, the proportion of Hong Kong’s FDI more than doubled in the mainland, and it reaches 70% recently. Hong Kong maintains its unique institutional space and advantages in bridging mainland China and the rest of the global economy (Li, Citation2020). It is like a goose that lays golden eggs (Bird, Citation2019; García-Herrero & Ng, Citation2019) that foreign companies and state investors have long used Hong Kong as a staging post for investing China (Liu, Citation2020). The incredible FDI data is also due to the existence of “round-trip” FDI – the capital that is first exported as outbound FDI and then imported back into China as inbound FDI (Huang, Citation2018). Almost all of the round-trip FDI uses Hong Kong as the transactional conduit. One indirect piece of evidence is the huge inbound FDI from Hong Kong and other free ports such as British Virgin Islands and Cayman Islands, and the huge outbound FDI to them. Offshore financial centers (characterized as a tax haven) have prominent location among the leading origin and destination points for FDI to China (Qiu, Citation2014; Vlcek, Citation2014), which include Hong Kong, Singapore, British Virgin Islands, Cayman Islands, Netherlands, Macao, and Samoa. In particular, Hong Kong, Singapore and British Virgin Islands are the top three FDI source of China in the current ().

Figure 6. The share of FDI flows to China by source (unit: 100%).

Data source: STATISTICAL BULLETIN OF FDI IN CHINA, MINISTRY OF COMMERCE, PRC

Note: The nine Asian countries/regions refer to Indonesia, Japan, Macao, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Republic of Korea, Thailand and Taiwan; Main members of the EU refer to Belgium, Denmark, Germany, France, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Greece, Portugal, Spain, Austria, Finland, Sweden and the UK (not included in 2020 due to Brexit); Some free port areas refer to Mauritius, Barbados, Cayman Islands, British Virgin Islands, Bermuda and Samoa.

Table 1. FDI inflows by major sources (top 15) in value and share of total FDI in years of 1997, 2002, 2008, 2019 and 2020.

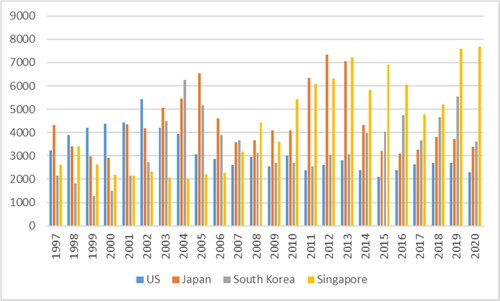

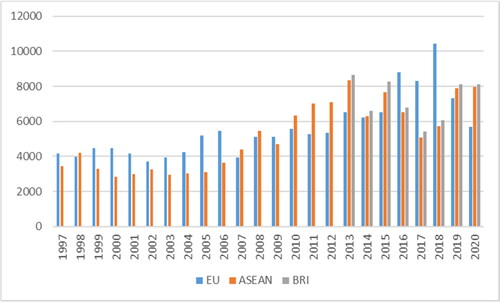

China's FDI attraction and foreign trade was benefited a lot from the easing Sino-US relations and trade normalization in the late 1990s. For the most time in the last century, U.S. direct investment in China was very small (Zhang, Citation2000). The U.S.-China Relations Act of 2000 in October, granting Beijing permanent normal trade relations with the United States and paving the way for China to join the World Trade Organization in 2001. This has induced US multinationals aggressively enter China and also led to a surge of Japanese and South Korean investments (). However, the 2008 financial crisis influenced global FDI flows and consequence a sudden shrink of FDI from advanced economic entities like US, Japan, and South Korea. In the Southeast Asia, Singapore contributes great share of FDI flows in China over the past decade (). As the regional financial hub, Singapore acts as a pivot or springboard for China-ASEAN economic cooperation and investment projects. Whereas, most ASEAN's FDI are through Singapore to enter China, and it accounts over 80% of the BRI countries' total ( and ). In the past years, at the time of growing tension with the US, China has its sights set on Europe and achieved substantial growth of FDI from the EU (). After a long-term negotiation, EU-China Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI) is finally completed at the end of 2020. The agreement aims to establish a unified legal framework for China-EU investment relations and replace the existing bilateral investment treaties between China and the 26 EU members. Although it has not been in effect officially, the investment agreement undoubtedly releases positive signals for doing business in China.

3. What drives the FDI sectoral changes?

Manufacturing FDI, especially the export-oriented, is driven by international price competitiveness measured by real unit labor costs (Riedl, Citation2010). As the rising price, China's attraction to labor-intensive manufacturing is downward, and many FDI recently move from China to Southeast and South Asia in seek of lower-cost production bases (Zhao et al., Citation2020). Rising wages and labor costs are negative to the expansion of manufacturing production, eroding China's global labor advantage (Ceglowski & Golub, Citation2012; Huang et al., Citation2021; Yang et al., Citation2010). Appreciation of the Chinese currency (RMB) since 2005 leads to cost increase of acquiring assets in China (Frankel, Citation2010; Goldstein & Lardy, Citation2006). It also increases construction and installation costs of direct investment projects especially greenfield FDI. Worse yet, as indigenous manufacturers grow and expand, there are much fiercer competitions in Chinese market in the 2010s. Overcapacity of the production, insufficient demand and down-ward profit cause mass bankruptcy and zombie firms of SMEs (Shen & Chen, Citation2017). The unfavorable market situation has made foreign investors cautious about Chinese manufacturing industries. US trade war against China and US-China geopolitical conflicts since 2018 makes manufacturing exports even worse. However, it does not dampen the growth of the FDI pool of China, because of more opportunities renewed in the rising market. As the Kuznets Law and the Inverted U curve describe, China is entering a higher stage of development with structural transformation and upgrading although turning to lower growth rate (Chen et al., Citation2011; Zhou et al., Citation2021). The sustained and rapid growth has led to multi-sectors' expansion of the national economy, and sectors as the driving force alternately. A fundamental transition is when China becomes the world's second largest economy only after the United States, the service sector is booming in the 2010s and contributes much more to the added value of gross production. Chinese urban growth, alongside infrastructure & municipal construction, has attracted massive FDI to be involved as well (Wang, Citation2011). For Chinese services, many sub-sector markets are still in the initial stage and have huge growth potentials. This is not only a growth point for the national economy, but a broad profit margin for investors. More international service suppliers have entered the Chinese market (Zhong & Wei, Citation2018). Thanks to rising incomes and expanding middle classes, Chinese wholesale and retail industry has embraced the golden era in the 2010s. Many multinational retailers have caught the opportunity and established sales networks throughout China, and foreign hypermarkets, products and brands are being more common and popular in China (Zhang & Wei, Citation2017). Besides merchandise trade for private consumption, business or production services are being the emerging investment field in China as well, due to massive demands of corporates and enterprises.

Manufacturing and trade in goods play a dominant role in Chinese economic development for the first three decades of reform and opening since 1978. But now, services are getting more attention in the national development strategy (Chen & Whalley, Citation2014). Service trade has been established as Chinese guideline for national development in the next five to ten years. To nurture some emerging services like E-commerce and digital finance, big data and cloud computing, cultural and creative industries, the state provides generous taxation favors, financial and insurance support as well as public platforms for professionalism training (Jiang et al., Citation2019). What China strives to build is a highly specialized and knowledge-intensive service industry (or namely modern services), which can spur the domestic consumer economy as well as service exports overseas. This requires the investment and participation of well-experienced multinationals, as Chinese service trade is in its infancy. The state holds the CHINA INTERNATIONAL FAIR FOR TRADE IN SERVICES (CIFTIS) regularly in Beijing. It is the largest exhibition in the field of global service trade, and bridge exchange and cooperation between Chinese and foreign service manufacturers. Foreign businessmen and multinationals investing in China's service industry can enjoy domestic preferential policies while avoiding tariff barriers or controls in related fields. They can not only operate Chinese domestic market, but also rely on networking channels to expand international trade.

The sectoral changes of FDI in China get effects from easing market access and facilitation for doing business. Chinese updated governance system loosens regulations for foreign business setup, that is simplification of approval procedures and opening of more investment areas (Hu, Citation2020). The authorities have drastically reduced the approval procedures for foreign investment and implemented a more relaxed management system for notification and filing (Zhang & Corrie, Citation2018). The newly revised "Special Administrative Measures for Foreign Investment Access (2019 Edition)," colloquially called the negative list, removed restrictions on certain areas. The items of negative list are regularly revised in accordance with the principle of only decreasing but not increasing. Compared with the 2019 editions, the 2020 negative lists are much shorter and feature further opening up in the services, manufacturing and agriculture sectors. The negative list of foreign investment access nationwide has been reduced from 40 items to 33, and the negative list for pilot free trade zones has been reduced from 37 items to 30 (HKTDC Research, Citation2020). This means that foreign companies and capital can enter any Chinese industry or sector freely, except for a few segmentate industries. Multinationals and investments in services are usually knowledgeable intensive, with professionals in the field. Intellectual property protection is a tricky issue, and how to deal with trade disputes in China is a widespread concern of foreign companies and investors. Also, national treatment and fair competition guarantees are particularly important for foreign service enterprises based in the Chinese market. Fortunately, Chinese legislation in the field of foreign investment has made breakthroughs recently. The rights and interests of foreign investors will be able to get protection by legal regulations. The "Foreign Investment Law" and its implement regulations have launched and come into force in 2020 (Zhao, Citation2019). It marks a milestone in the 40-year policy process since the reform and opening up, and in replacement of the "Sino-Foreign Equity Joint Venture Law," "Sino-Foreign Contractual Joint Ventures Law" and "Wholly Foreign-Owned Enterprises Law" enacted in the 1980s (collectively referred to as the Three Foreign Investment Laws) (Lai, Citation2019). As the abolishment of the Three Foreign Investment Laws, multi-party investment and diverse business models across industries or sectors will no longer be constrained.

4. Factors behind changing country-origin of FDI

Hong Kong has become a major FDI source of mainland China ever since the return of sovereignty in 1997. It provides stable overseas funds for Chinese development and domestic construction. The role of Hongkong as a financial base is more significant in the context that Chinese indigenous corporates booming. Many newly established Chinese companies went to Hong Kong to list or set up financing institutions, for external funds collection, and then return to invest and expand production (Lin, Citation2018). This can take advantage of Hong Kong's financial platform to raise money, but also obtain tax deductions or exemptions in accordance with mainland policies as a “Hong Kong capital” identity. Behind the substantial growth of Hong Kong capital is the closing economic connections with the mainland. The process of financial and market integration has made Hong Kong a major channel to raise international capital for China. In addition to bond Hongkong with the mainland, China actively promotes regional economic and trade integration in the East and Southeast Asia. The slow recovery in the post-crisis era and growing tensive relation with the United States negatively influence China to stabilize FDI flow and international trade. To deal with the disadvantageous situation, China has exercised economic diplomacy and established a series of bilateral or multilateral investment and trade agreements. China is keenly on promoting the liberalization of trade and investment in East Asia. The tripartite free trade agreement has been in negotiations for long that aims to construct a China-Japan-Republic Korea Free Trade Area ultimately. As early results, the tripartite investment agreement (2012) and China-Republic Korea Free Trade Agreement have been signed and into effect. These policy favors spur the rebound and rise of Japanese and South Korean FDI to China in the post-crisis era.

In the Southeast Asia, Singapore's status as a major investor in China has been increasingly prominent. Singapore goes ahead in the economic and trade relations with China. It is the first ASEAN country to sign a comprehensive FTA with China. And in 2018, the two countries signed the protocol to upgrade FTA that supplements the original agreement’s rules of origin, customs procedures and trade facilitation, trade remedies, service trade, investment, and economic cooperation, as well as three newly added sectors: e-commerce, competition policies and the environment (Zhang, Citation2019). China has proposed and been promoting the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) vigorously since 2012. Singapore is the first country in the ASEAN to publicly support it, and the first developed economy to join the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. Especially, Singapore conducts some large-scale intergovernmental investment projects in China. It allows Singapore’s corporates to participate in Chinese domestic development & construction, and catch more business advantages in time. The China-Singapore (Chongqing) Demonstration Initiative on Strategic Connectivity (launched in 2015), covering the entire Southwest China, is in line with Chinese development strategies of the "Belt and Road," "Western Development," and "Yangtze River Economic Belt" (Gong, Citation2019). Massive Singaporean corporates and investments are flowing to China for business expansion in recent years.

As well as the regional integration of Asian economies, China is pushing a framework for Sino-European business and trade cooperation. Leadership diplomacy and inter-state cooperation play an inestimable role in deepening China-EU investment relations, and encourage European investment in China. Germany is Chinese major trading partner in Europe as well as the main EU investor. It generates the largest direct investments and number of technology transfers from Europe to China. The German government pursue practical cooperation and friendly exchanges with China, and play a constructive role in China-EU relations. In relations with Western countries, leaders of China and Germany have the most frequent exchange and visits. During her 16 years as prime minister, Merkel has visited China 12 times, and her footprints almost spread all over China. This is so unique among leaders of Western countries. Economic, trade and industrial cooperation are the core themes of the exchanges between the two countries. In Chancellor Merkel's previous visits to China, an accompanying tour group mainly composed of business people is almost the standard. Chinese government also promotes the strategic connection between "Made in China 2025" and Germany's "Industry 4.0" and provides policy support for enterprises that categorized within the scope of industrial plan.

5. Concluding remarks and discussion

We make a systematic investigation of the FDI distribution and inter-annual changes in Chinese economic sectors. Longitudinal and multi-sectoral analysis is of necessity for emerging and transitional economies like China. Keenly capture the sectors or industries with foreign capital flows are the key to grasping international investment trends and growing points. Our research reveals the fields favored by FDI in different periods and the inter-relationship with the structure of national economy. It indicates the role or status of host land, especially developing countries, in cross-border investment can be re-defined. That can be a proactive go-getter rather than a pure passive recipient. FDI into China has no longer concentrated in the manufacturing sector in a traditional manner, but more in high-tech industries and knowledge-intensive services. This is inseparable from the current stage of Chinese development, economic restructuring and policy guidance. The massive transfer of foreign manufacturers to China has made outstanding contributions to the country's industrial development. After that, Chinese technology has risen sharply, and a complete industrial system has been established. Chinese economy is evolving toward a multi-sector complex. Many emerging industries become “hotspots” of investment and catch the eyes of foreign capital. Chinese FDI inflows have experienced a shift from manufacturing to real estate and service sectors. While China is still receiving substantial manufacturing FDI, services FDI has taken up a dominant share of total flows and as the main driver of FDI growth. A series of factors including labor cost increase, currency appreciation, overcapacity of production, domestic competition rise and US trade war cause negative effects on manufacturing FDI flows, but rising purchasing power, consumer demand and market capacity create new opportunities for foreign business in China. Chinese economy undergoes structural transformation and slowing growth. The policy guidance conforms to the new normal. Service trade is being Chinese development orientation in the current and future. The government aims to nurture it as an engine of growth alongside trade in goods. Many incentive policies have been launched and targeted for numerous service industries. These are the push hand behind the rapid rise in service FDI. Anyway, technological progress, economic restructure and market rise spawn the advantage of China for subsequent FDI attraction, and broad service industries are being new favorites of foreign capital in particular.

Foreign investment in China has maintained a growth trend in the long run, but the situation for the source countries is quite different. Entrepreneurs and investors are sensitive to international relations and Chinese domestic situations in order to avoid risks or maximize benefits. The specific exchanges and contacts between countries or regions become a boost to the realization of overseas investment goals. Sovereign ties and the status of offshore financial center make Hong Kong a crucial platform for China to attract and utilize foreign capital. The vast majority of foreign investment enters the mainland through Hong Kong. Rapid growth and diversified origins of FDI in China is a result of easing Sino-US relations and trade normalization. The U.S.-China Relations Act of 2000 in October, granting Beijing permanent normal trade relations with the United States and paving the way for China to join the World Trade Organization in 2001. This has induced US multinationals aggressively enter the Chinese market and also led to a surge of Japanese and South Korean investment in China. It contributes to China's rapid industrialization and economic growth in the first decade of this century. Since then, China has pursued a more active economic diplomacy and focused on building a regional multilateral investment and trade framework. This promotes regional economic integration in East and Southeast Asia and creates conditions for the liberalization of intra-regional investment. Singapore, South Korea, and Japan are the fulcrum of Chinese economic cooperation in Asia and the main FDI sources. In the past few years, the ongoing US-China trade war has heightened geopolitical tensions in the Asia-Pacific. The momentum of the substantial increase in U.S. FDI to China has gone forever. To handle the unfavorable international situation, China steps up the trade negotiations with the Europe. It improves Sino-EU economic and trade relations and boosts the EU investment in China. As a sum, Chinese policy practices encompassing industrial planning and international cooperation cause positive effects on the source dynamics of FDI in China.

Our studies of FDI's structural changes in China have policy implications widely. In the globalization era, adhering to free trade policies and market open are crucial for domestic development. But the government of host countries should make efforts to guide sector or industry distribution of FDI, in order to take FDI's advantage and better serve the industrialization in domestic. It is noteworthy that multinational's investment cannot naturally promote economic development of host areas. Wako (Citation2021) proposes a view that FDI is detrimental to certain aspects and has contributed to the ‘premature’ deindustrialization of sub-Saharan Africa. He defines it as an ‘institutional’ resource curse. Developing countries are likely to become the energy or natural resource bases of developed world due to massive FDI injection. It results in the concentration and lack in diversity of investment sectors, and has no way to boost local economy. A gradual manner of market access is a practical policy and may be more appropriate for developing countries. The industrial sector opened to FDI should be those that can play a role in national economic growth. The authorities should encourage investment in key areas and industries that can drive employment of local people. When facing international tensions and rising protectionism, the government can adjust to more active trade policies and establish FTA systems to maintain capital flow. For multinationals and international investors, the tariff advantages of free ports can reduce their trade risks and shocks from international political instability. Direct investment should go as far as possible into emerging industries of the host country. This will help them establish market advantage early on. More FDI projects can pay attention to energy saving and technological transformation, as environmental awareness rises and carbon emission limits. Meanwhile, multinationals can practice entrepreneurial spirits in the host country friendly and consciously assume social responsibilities. It will enable them build a reputation renowned and benefit their foreign business in a long run.

Acknowledgment

The author appreciates kind comments and suggestions of the editor and reviewer.

Disclosure statement

The author reports there are no competing interests to declare.

References

- Aichele, R., & Heiland, I. (2018). Where is the value added? Trade liberalization and production networks. Journal of International Economics, 115, 130–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinteco.2018.09.002

- Beaulieu, E., Lian, Z., & Wan, S. (2020). Presidential marketing: Trade promotion effects of state visits. Global Economic Review, 49(3), 309–327. https://doi.org/10.1080/1226508X.2020.1792329

- Bird, M. (2019). Well-behaved Macau can't compete with unruly Hong Kong's financial clout. Wall Street Journal, 18 December. https://www.wsj.com/articles/well-behaved-macau-cant-compete-with-unruly-hong-kongs-financial-clout-11576670582

- Ceglowski, J., & Golub, S. S. (2012). Does China still have a labor cost advantage? Global Economy Journal, 12(3), 1850270. https://doi.org/10.1515/1524-5861.1874

- Chen, H., & Whalley, J. (2014). China's service trade. Journal of Economic Surveys, 28(4), 746–774. https://doi.org/10.1111/joes.12081

- Chen, S., Jefferson, G. H., & Zhang, J. (2011). Structural change, productivity growth and industrial transformation in China. China Economic Review, 22(1), 133–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2010.10.003

- Cui, L., Fan, D., Li, Y., & Choi, Y. (2020). Regional competitiveness for attracting and retaining foreign direct investment: A configurational analysis of Chinese provinces. Regional Studies, 54(5), 692–703. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2019.1636023

- Fan, H., He, S., & Kwan, Y. K. (2019). Foreign direct investment and productivity spillovers: Is China different? Applied Economics Letters, 26(20), 1675–1682. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504851.2019.1591591

- Frankel, J. (2010). The renminbi since 2005. The US-Sino Currency Dispute: New Insights from Economics, Politics and Law, 51, 51–60. https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.190.3115&rep=rep1&type=pdf#page=60

- Gani, A., & Scrimgeour, F. (2019). Can trading partner cultural diversity explain trade? Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy, 24(2), 313–327. https://doi.org/10.1080/13547860.2019.1602905

- García-Herrero, A., & Ng, G. (2019). Hong Kong's economy is still important to the Mainland, at least financially. Bruegel, 19 August. https://bruegel.org/2019/08/hong-kongs-economy-is-still-important-to-the-mainland-at-least-financially/

- Goldstein, M., & Lardy, N. (2006). China's exchange rate policy dilemma. American Economic Review, 96(2), 422–426. https://doi.org/10.1257/000282806777212512

- Gong, X. (2019). The Lion-Dragon Dance in the Chongqing Connectivity Initiative: A critical view on Singapore-China economic relations. Asian Education and Development Studies, 10(1), 135–145. https://doi.org/10.1108/AEDS-11-2018-0169

- Hayakawa, K., Mukunoki, H., & Yang, C. H. (2020). Liberalization for services FDI and export quality: Evidence from China. Journal of the Japanese and International Economies, 55, 101060. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jjie.2019.101060

- HKTDC Research. (2020). China releases 2020 negative lists for foreign investment access. HKTDC Research [online], 26 Jun 2020. Retrieved November 17, 2021, from https://research.hktdc.com/en/article/NDY2ODcyNTIz

- Hu, J. (2020). From SEZ to FTZ: An evolutionary change toward FDI in China. In J. Chaisse, L. Choukroune, & S. Jusoh (Eds.), Handbook of international investment law and policy (pp. 1–22). Springer.

- Hu, Y., Fisher-Vanden, K., & Su, B. (2020). Technological spillover through industrial and regional linkages: Firm-level evidence from China. Economic Modelling, 89, 523–545. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2019.11.018

- Huang, S., & Chen, Y. (2014). FDI in services and China's service export sophistication [Paper presentation]. In 2014 11th International Conference on Service Systems and Service Management (ICSSSM), June (pp. 1–5). IEEE.

- Huang, Y. (2018). Inbound Foreign Direct Investment. The SAGE handbook of contemporary China (pp. 189–204). SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Huang, Y., Sheng, L., & Wang, G. (2021). How did rising labor costs erode China’s global advantage? Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 183, 632–653. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2021.01.019

- Jiang, C., Hong, Q. L., & Qiu, L. (2019). The development and policy choice of China’s service trade. In C. Jiang, Q. L. Hong, & L. Qiu (Eds.), China's white-collar wave (pp. 165–186). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Kee, H. L., & Tang, H. (2016). Domestic value added in exports: Theory and firm evidence from China. American Economic Review, 106(6), 1402–1436. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20131687

- Kim, M., & Xin, D. (2021). Export spillover from foreign direct investment in China during pre-and post-WTO accession. Journal of Asian Economics, 75, 101337. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asieco.2021.101337

- Kong, W. N. (2022). Economic effect and resolution idea of the THAAD political conflict on South Korea’s exports to China. The Chinese Economy, 55(2), 88–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/10971475.2021.1930300

- Lai, K. (2019). PRIMER: China’s new foreign investment law. International Financial Law Review [online], May 2019. Retrieved November, 17, 2021, from https://queens.ezp1.qub.ac.uk/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/primer-china-s-new-foreign-investment-law/docview/2241168949/se-2?accountid=13374

- Latorre, M. C., Yonezawa, H., & Zhou, J. (2018). A general equilibrium analysis of FDI growth in Chinese services sectors. China Economic Review, 47, 172–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2017.09.002

- Li, C. (2020). Hong Kong’s economy navigating turbulent times. East Asian Policy, 12(01), 59–71. https://doi.org/10.1142/S1793930520000057

- Lin, D. (2018). Hong Kong’s China-invested companies and their reverse investment in China. In J. Child & Y. Lu (Eds.), Management issues in China (Vol. II, pp. 165–182). Routledge.

- Liu, K. (2020). Hong Kong: Inevitably irrelevant to China? Economic Affairs, 40(1), 2–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecaf.12391

- Porter, M. E., ed. (1986). Competition in global industries. Harvard Business School Press.

- Porter, M. E. (1998). The competitive advantage of nations (2nd ed.). Free Press (1st ed., Free Press, 1990).

- Qiu, D. (2014). Collecting unpaid tax offshore: Caribbean tax havens and foreign direct investment in China. Bulletin of International Taxation, 12, 648–659. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2539511

- Riedl, A. (2010). Location factors of FDI and the growing services economy 1: Evidence for transition countries. Economics of Transition, 18(4), 741–761. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0351.2010.00391.x

- Shen, G., & Chen, B. (2017). Zombie firms and over-capacity in Chinese manufacturing. China Economic Review, 44, 327–342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2017.05.008

- Sun, S. (2012). The role of FDI in domestic exporting: Evidence from China. Journal of Asian Economics, 23(4), 434–441. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asieco.2012.03.004

- Tan, D., & Meyer, K. E. (2011). Country-of-origin and industry FDI agglomeration of foreign investors in an emerging economy. Journal of International Business Studies, 42(4), 504–520. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2011.4

- Tang, Y., Yan, J., & Yu, F. (2021). The welfare effects of service trade liberalization: Evidence from the Chinese movie industry. Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/13547860.2021.1981035

- Tang, Y., & Zhang, K. H. (2016). Absorptive capacity and benefits from FDI: Evidence from Chinese manufactured exports. International Review of Economics & Finance, 42, 423–429. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iref.2015.10.013

- Vlcek, W. (2014). From Road Town to Shanghai: Situating the Caribbean in global capital flows to China. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 16(3), 534–553. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-856X.12010

- Wako, H. A. (2021). Foreign direct investment in sub-Saharan Africa: Beyond its growth effect. Research in Globalization, 3, 100054. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resglo.2021.100054

- Wang, C., Clegg, J., & Kafouros, M. (2009). Country-of-origin effects of foreign direct investment. Management International Review, 49(2), 179–198. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11575-008-0135-4

- Wang, H., Fidrmuc, J., & Tian, Y. (2020). Growing against the background of colonization? Chinese labor market and FDI in a historical perspective. International Review of Economics & Finance, 69, 1018–1031. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iref.2018.12.010

- Wang, L. (2011). Foreign direct investment and urban growth in China (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315582771

- Whalley, J., & Xian, X. (2010). China's FDI and non-FDI economies and the sustainability of future high Chinese growth. China Economic Review, 21(1), 123–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2009.11.004

- Yang, D. T., Chen, V. W., & Monarch, R. (2010). Rising wages: Has China lost its global labor advantage? Pacific Economic Review, 15(4), 482–504. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0106.2009.00465.x

- Zhang, K. H. (2000). Why is U.S. Direct investment in China so small? Contemporary Economic Policy, 18(1), 82–94. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1465-7287.2000.tb00008.x

- Zhang, K. H. (2007). International production networks and export performance in developing countries: Evidence from China. The Chinese Economy, 40(6), 83–96. https://doi.org/10.2753/CES1097-1475400605

- Zhang, K. H. (2015). What drives export competitiveness? The role of FDI in Chinese manufacturing. Contemporary Economic Policy, 33(3), 499–512. https://doi.org/10.1111/coep.12084

- Zhang, L., & Wei, Y. D. (2017). Spatial inequality and dynamics of foreign hypermarket retailers in China. Geographical Research, 55(4), 395–411. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-5871.12235

- Zhang, X., & Corrie, B. P. (2018). Chinese policies on encouraging foreign investment. In X. Zhang & B. P. Corrie (Eds.), Investing in China and Chinese investment abroad (pp. 13–20). Springer.

- Zhang, Z. (2019, October 21). China-Singapore FTA: Protocol to upgrade agreement in effect from October 16. China Briefing. Retrieved November 6, 2021, from https://www.china-briefing.com/news/china-singapore-fta-protocol-upgrade-effect-october-16/

- Zhao, M. (2019). Analysis and interpretation of the new foreign investment law of the People’s Republic of China. China and WTO Review, 5(2), 351–386. https://doi.org/10.14330/cwr.2019.5.2.05

- Zhao, S. X., Wong, D. W., Wong, D. W., & Jiang, Y. P. (2020). Ever‐transient FDI and ever‐polarizing regional development: Revisiting conventional theories of regional development in the context of China, Southeast and South Asia. Growth and Change, 51(1), 338–361. https://doi.org/10.1111/grow.12358

- Zhong, Y., & Wei, Y. D. (2018). Economic transition, urban hierarchy, and service industry growth in China. Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie, 109(2), 189–209. https://doi.org/10.1111/tesg.12276

- Zhou, X., Cai, Z., Tan, K. H., Zhang, L., Du, J., & Song, M. (2021). Technological innovation and structural change for economic development in China as an emerging market. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 167, 120671. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2021.120671