Abstract

This paper examines contemporary Chinese-Kazakhstani political economic ties from the perspective of trade. In particular, it traces the evolution of this relationship before and after the critical juncture of 2013, when the Silk Road Economic Belt was announced in Astana, ushering the era of the Belt and Road Initiative. This paper advances three arguments. First and foremost, Kazakhstan has avoided developing a dependency on the Chinese economy. Its trade autonomy has been maintained before and after the Belt and Road Initiative was launched in 2013, as Kazakhstan benefited from the development of markets alternative to China. Secondly, trade between Kazakhstan and China was mostly focused on natural resources during the immediate pre-BRI years, but it has gradually shifted to a more balanced mix, encompassing intermediate goods, raw materials, and consumer goods. Thirdly, such diversification is the product of an increasingly sophisticated, complex value chain interconnecting Kazakhstan and the rest of the world, including but not limited to China. The growing complexity of these production networks, while certainly beneficial to Chinese firms, has also contributed to Kazakhstan’s multi-vector geopolitical strategy. In this environment, Kazakhstan demonstrates the capability to weather the ongoing deceleration of China’s economy, as the Central Asian country pursues the diversification of its own economy and external economic ties.

1. Introduction

Since its independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, Kazakhstan has adopted a multi-vector foreign policy, seeking partnerships with various nations. Kazakhstan’s basic idea of multi-vectorism is to establish mutually beneficial cooperation with other countries, even those beyond its immediate borders (see, for example, Bitabarova, Citation2018; Laumulin & Tolipov, Citation2010; Swanström, Citation2007; Vanderhill et al., Citation2020). In so doing, the Central Asian nation has thus far been able to preserve its sovereignty, allowing it to coexist with much bigger states without becoming their client states. Two of these states are particularly noteworthy. Firstly, there is Russia, a historically dominant power in Northern Eurasia that remains highly influential in the modern and contemporary periods. It shares deep cultural, historical, and linguistic ties with Kazakhstan, going back several centuries. Kazakhstan and Russia have also generally kept a close relationship after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Secondly, Kazakhstan devotes significant diplomatic attention to China. Much like Russia, China enjoys deep historical ties with Kazakhstan. China-Kazakhstan ties received a major boost after Kazakhstan’s 1991 independence as a series of border agreements and political partnerships were ratifiedFootnote1. China’s increasing economic prosperity has also laid the groundwork for closer economic ties. In 2013, Chinese President Xi Jinping, freshly entering his first term of office, announced what later became known as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). It has since become China’s signature foreign economic policy campaign. To a certain extent, the BRI has also become synonymous with the Xi government’s policiesFootnote2.

With the World Bank (Citation2019) valuing investments related to the BRI at US$575 billion, it was only logical for Kazakhstani economic planners to seek further cooperation with China. Their decision has borne some fruit as the BRI has ushered in economic gains for the Central Asian state. Yet, such development has to be viewed alongside some critique highlighting the initiative’s negative externalities (see Pantucci, Citation2019). Simonov (Citation2019) notes that about half of Chinese foreign direct investment (FDI) has been channeled toward the oil and gas industry. Relying on one’s abundant oil and gas deposit is not a problem per se, but the issue is seemingly complicated by a lack of transparency on such projects. Additionally, there is concern that the heavy weightage of oil and gas-related FDI would slow down the nation’s diversification into other (more productive and low-carbon) industries (Baldakova, Citation2022). The discontent is also observed outside the oil and gas industry. For example, local protests against the construction of Chinese factories were held across three Kazakhstani cities in 2019. These locals gathered to demand a ban on what they described as plans to move outdated and polluting Chinese plants to Kazakhstan (Maclean, Citation2019). Further back in 2016, protesters voiced anger against a planned land reform which they said would have allowed foreigners (in their interpretation, Chinese) to acquire swathes of Kazakhstani farmland (Abdurasulov, Citation2016). Perhaps aware of the public sentiment and the track record of earlier similar protests in 2010, the authorities soon shelved the reform. These reports are occasionally conflated with fiery (and arguably primordial-ist) rhetoric, which, coupled with Kazakhstan’s semi-liberal political environment, complicates the triangulation of information. However, the overarching theme appears to stem from longstanding, if unspoken, fears that China is ‘buying up Kazakhstan’ through a series of lopsided trade and investment deals.

With the above as a backdrop, this paper seeks to address the following research questions: Are there alternative ways to portray long-term China-Kazakhstan ties, especially from the viewpoint of international political economy? More to the point, how have China-Kazakhstan trade ties evolved in the pre- and post-BRI years? What implications can be drawn here for a more informed understanding of the opportunities and challenges facing Kazakhstan as the Xi administration enters its third term? Three inter-related arguments are forwarded. Firstly, trade dependence on China has generally been kept at a relatively stable rate, both in the pre- and post-BRI era. The development of alternative markets such as Russia, the EU, Central Asian and post-Soviet states, the Eurasian Economic Union, and Turkiye, has reduced Kazakhstan’s reliance on China. Secondly, trade between Kazakhstan and China was mostly focused on natural resources during the immediate pre-BRI years, but it has gradually shifted to a more balanced distribution that includes intermediate goods, raw materials, and consumer goods. Thirdly, such diversification is the product of an increasingly sophisticated, complex value chain interconnecting Kazakhstan and the rest of the world. Chinese firms, courtesy of their greater command of capital and technology, have most likely captured key positions in the Kazakhstan industrial ecosystem. Yet, this has also enhanced the sophistication of the value chain criss-crossing Kazakhstan, simultaneously bolstering the Central Asian nation’s multi-vector strategy.

This paper starts with a critique on Kazakhstan’s well-established multi-vector strategy. More importantly, it exhorts an on-the-ground perspective of the multi-vector strategy, illustrating the merits of looking beyond large-scale geopolitical shifts and conventional literature. The subsequent section analyses trade ties between Kazakhstan and China. Then, several insights are discussed to showcase the production networks that have emerged after the BRI’s inception. Following this, the paper outlines the opportunities and challenges facing Kazakhstan in relation to China during President Xi’s third term. The paper concludes with a summary of the core arguments and outlines several avenues for future research.

2. Kazakhstan’s multi-vector foreign policy: maximizing the number of “baskets” for “eggs”

Much has been written about how China’s growing economic clout is reshaping the regional and global political economic architecture. The implicit understanding driving much of the discussion, especially popular in international relations and related disciplines, hinges on the extent to which China can be incorporated into a US-dominated international system (see, for example, Ji & Lim, Citation2022; Rana & Pardo, Citation2018; Soong, Citation2022). This perspective is observed just as much in post-Soviet Central Asia. In this line of thought, Kazakhstan (and the other Central Asian states) is often reductively conceived or downright misconceived as ‘Russia’s backyard’. Kazakhstan’s engagement with countries such as China and the US is thus interpreted as attempts to fill the power vacuum in the aftermath of the Soviet Union’s collapse.

Earlier discussion focused largely on the geostrategies by the external powers to secure Kazakhstan’s vast natural resources, consumer markets, and national territories, continuing the narrative of the so-called ‘New Great Game’ (e.g. Kazantsev, Citation2008; Menon, Citation2003). However, subsequent analysis has shed more spotlight on the perspectives of host states, challenged their objectification in scholarship, and critically engaged with the New Silk Road discourse (Cooley, Citation2014; Dadabaev, Citation2018; Kazantsev, Citation2008; Murashkin, Citation2019; Tjia, Citation2023). Bitabarova (Citation2018) has conducted one of such studies. The scholar demonstrates that Kazakhstan has exercised considerable agency in shaping the negotiation agenda in its interaction with China to implement BRI projects. There is little evidence that China imposes its own vision as Kazakhstani economic planners have preserved their nation’s autonomy by establishing priority areas and installing administrative safeguards.

Moreover, a shared understanding between the two states about the complementarity of mutual interests provides a solid foundation for overall China-Kazakhstan cooperation. According to Tjia (Citation2022), the leadership of Kazakhstan sought to link up the BRI with several of its most ambitious national development programs, especially the Nurly Zhol (Bright Path). Nurly Zhol was first announced by then Kazakh President Nursultan Nazarbayev in November 2014, about a year after Xi announced the ‘Silk Road Economic Belt,’ one-half of the plan which eventually became the BRI, when visiting Kazakhstan in September 2013. This bilateral economic collaboration encompasses not only transportation connectivity, but also wider forms of industrial cooperation. Research shows that the latter encompasses industries ranging from agriculture, machinery manufacturing, to natural resource processing (see also Harutyunyan, Citation2022). Kazakhstan’s apparent gravitation to China, however, must be interpreted in a more contextual manner. For example, popular opinion of China remains divided in the country. As mentioned earlier, anti-Chinese sentiment has been fueled by (perceived or real) factors such as environmental concerns, lack of transparency, land grabbing, and securitization of ethnic minorities (including Kazakhs) in parts of China (Baldakova, Citation2022). Relatedly, the forging of close economic ties with China has not seen Kazakhstan pull away from Russia. Rather, the opportunities from China (and other countries) have helped Kazakhstan hedge its traditional reliance on Russia without causing friction with Moscow. The usage of new and reinvigorated trade hubs, such as the dry port of Khorgos and the seaport of Lianyungang, benefited China, Kazakhstan, and Russia alike. What has transpired is the enmeshing of both China and Russia, in addition to other external powers, in a series of regional agreements without binary oppositions. These institutions foster interdependence, making direct conflict prohibitively expensive (Vanderhill et al., Citation2020).

Furthermore, Kazakhstan has been strengthening its own position in regional development finance as the second-largest shareholder (after Russia) of the Eurasian Development Bank, headquartered in Almaty since 2006 and not featuring China as a member; and, more recently, on a bilateral basis with the establishment of Kazakhstan Agency of International Development in 2020. Besides, Kazakhstan’s security cooperation with Russia and the Collective Security Treaty Organization was pivotal in President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev’s handling of the 2022 unrest.

While state agency and international power dynamics certainly underpin Kazakhstan’s multi-vectorism, it is also influenced by market forces. Take the proliferation of Chinese firms in Kazakhstan, for instance. Despite occasional concerns about their activities, their westward expansion is fundamentally driven by economic imperatives. One of the most important push factors is the secular deceleration of the Chinese economy following years of rapid growth. Faced with overcapacity and domestic economic slowdown, Chinese firms are under increasing pressure to target the international market (Liu & Lim, Citation2023). On the pull side of the equation, Kazakhstan’s emerging middle class is not commonly discussed in realist-driven scholarship. Market research also indicates that its demography—half of Kazakhstan’s population is under 29 years of age—is open to quality products and brand names, not least those brought in from abroad (Euromonitor International, Citation2024).

This paper fosters dialogue with such analysis, providing additional insights to illuminate the economic dimensions of the BRI in Kazakhstan. In so doing, the paper moves discussion away from literature that places the pursuit of geostrategic interest as virtually the sole objective of analysis. This is not to devalue Kazakhstan’s multi-vector foreign policy, nor does it deny multi-vectorism’s relevance in the crafting of Kazakhstani development trajectory. More specifically, it goes beyond a macro-level analysis, with the ultimate goal of offering the scholarly community a richer picture of the dynamics, contours, and effects of the BRI in Kazakhstan.

3. Trading with China

Trade is one of the most critical mechanisms for Kazakhstan, and virtually all other economies, to build ties with the rest of the world. Within the context of this paper, it is possible to estimate how Kazakhstan has engaged an increasingly wealthy China. Indeed, tracks Kazakhstan’s trade with China and the entire global economy over a 21-year period. Between 2000 and 2021, Kazakhstan consistently enjoyed a trade surplus against China. Trade turnover with China has also increased from 2000 to 2012, a year before the BRI’s announcement. However, it has gradually declined since, turning around only in 2017. Even then, post-2017 trade has not been able to match the heights recorded in the early 2010s. The expansion in trade also means that China has become one of Kazakhstan’s most important markets, growing in tandem with other partners such as Russia, Turkiye, and the EU. However, China has failed to capture more than 20% of Kazakhstan’s total trade portfolio during the period in question.

Table 1. Kazakhstan’s Trade with China and the World, 2000–2021 (billions US$).

China’s trade weightage after the BRI’s announcement has generally fluctuated. It was not until 2020 that it exceeded the 17.53%-mark recorded in 2012, the previous peak. Chinese market share in the export and import categories, however, displays some interesting trends. Once again, 2012 marks the turning point. Prior to 2012, China’s export share has generally outperformed the corresponding import share. However, since 2012, China’s import share began to outweigh the corresponding export share, barring one year (i.e. 2020).

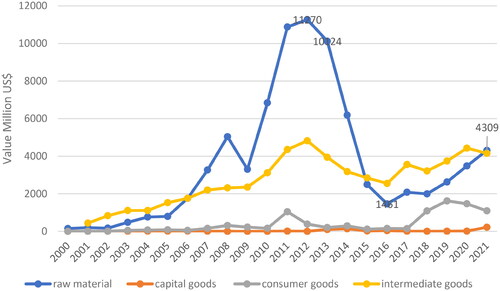

A more interesting perspective can be presented via further exploration of the China-Kazakhstan trade. and illustrate that export to China is driven largely by two product categories: raw materials and intermediate goods. A third product category—consumer goods—only gained prominence from 2018 onwards. Raw materials export rose sharply from 2000 to 2012, but experienced a drop of almost equal magnitude thereafter. It was not until 2016 that export revenue began to pick up, but the amount in 2021 (US$ 4.31 billion) is a far cry from the US$ 11.27 billion garnered during the peak year of 2012 (see ). Compared to raw materials export, export of intermediate goods shows a much smoother increase over the same period. While it did suffer a downturn in 2012, the decrease is much less drastic than the export of raw materials.

Figure 1. Kazakhstan’s exports to China: total value by category, 2000–2021.

Source: World Integrated Trade Solution data, World Bank, available at: https://wits.worldbank.org/CountryProfile/en/Country/KAZ/StartYear/2000/EndYear/2021/TradeFlow/Export/Indicator/XPRT-TRD-VL/Partner/CHN/Product/all-groups# (accessed 16 November 2023).

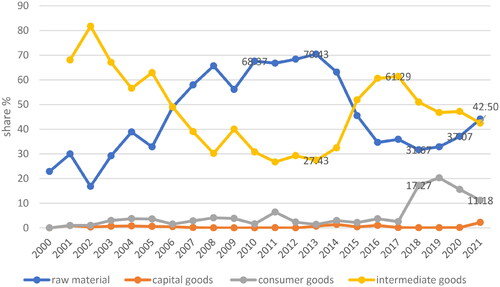

Figure 2. Kazakhstan’s exports to China: shares by category, 2000–2021.

Source: World Integrated Trade Solution data, World Bank, available at: https://wits.worldbank.org/CountryProfile/en/Country/KAZ/StartYear/2000/EndYear/2021/TradeFlow/Export/Indicator/XPRT-PRDCT-SHR/Partner/CHN/Product/all-groups# (accessed 16 November 2023).

displays the product market share data, revealing an inverse connection between raw materials and intermediate goods export. In 2021, both products have comparable market share of approximately 42% apiece. Consumer goods exported to China did not register a noticeable market presence for most of the period analyzed. However, it gained a large enough presence in 2018, capturing about 18% of the total market share. Its contribution can only be understood more meaningfully with more longitudinal data, but—in an encouraging development—it has managed to stay above the 10%-mark since 2018.

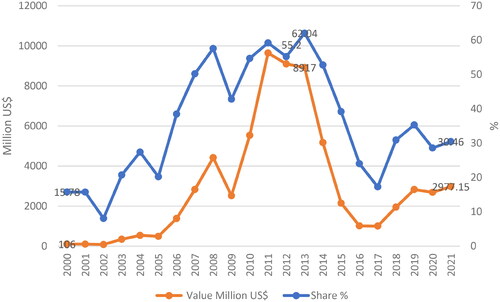

illustrates another dimension of Kazakhstani export to China. The country’s abundant oil and gas deposits have helped it garner export revenue from the Chinese; this is especially evident between 2000 and the early 2010s. However, fuel export—absolute value and market share—has shown a moderating trend after 2013. This boom-and-bust pattern broadly mirrors that of international oil price. Yet, as and have illustrated earlier on, export of intermediate goods (and to a smaller extent, consumer goods) has partially cushioned the export shortfall of raw materials, particularly fuel.

Figure 3. Kazakhstan’s fuel exports to China: total value and shares, 2000–2021.

Source: World Integrated Trade Solution data, World Bank, available at: https://wits.worldbank.org/CountryProfile/en/Country/KAZ/StartYear/2000/EndYear/2021/TradeFlow/Export/Indicator/XPRT-TRD-VL/Partner/CHN/Product/all-groups# (accessed 16 November 2023).

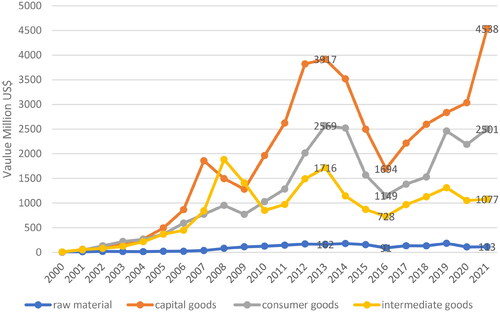

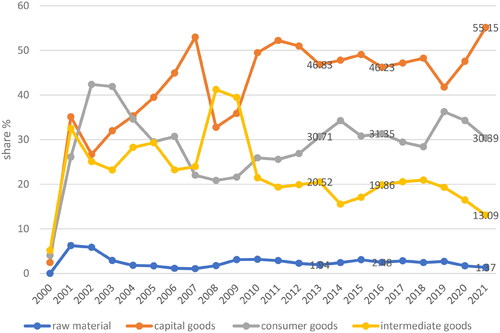

shows that the import of all items generally increased from 2000 to 2013, before witnessing a rather steep decline in the ensuing years. Import eventually picked up in 2016, with strong demand particularly for capital goods and consumer goods. Except for 2008 and 2009, capital goods is shown as the main item imported into the country. Consumer goods and intermediate goods are the second- and third-most valuable import items respectively.

Figure 4. Kazakhstan’s imports from China: total value by category, 2000–2021.

Source: World Integrated Trade Solution data, World Bank, available at: https://wits.worldbank.org/CountryProfile/en/Country/KAZ/StartYear/2000/EndYear/2021/TradeFlow/Import/Indicator/MPRT-TRD-VL/Partner/CHN/Product/all-groups# (accessed 16 November 2023).

Additionally, illustrates that capital goods have almost always accounted for 30% or more of the product market share throughout the period analyzed. This predominance has even intensified from 2010 onwards. The share of consumer goods has generally hovered around the 25%-mark from 2000 to 2021. For intermediate goods, its peak market share (slightly above 40%) was attained in 2008. Its market share has since been steadily declining.

Figure 5. Kazakhstan’s imports from China: shares by category, 2000–2021.

Source: World Integrated Trade Solution data, World Bank, available at: https://wits.worldbank.org/CountryProfile/en/Country/KAZ/StartYear/2000/EndYear/2021/TradeFlow/Import/Indicator/MPRT-PRDCT-SHR/Partner/CHN/Product/all-groups# (accessed 16 November 2023).

These trade networks have proliferated in tandem with an expansion of Chinese FDI. According to Tjia (Citation2022), the majority of Chinese FDI financed oil and gas extraction, pipeline construction, metal mining, transport infrastructure, and a few cultural projects before 2013. However, Chinese FDI flows have diversified further since. Her studies show that since 2013, close to 80% of Chinese projects in Kazakhstan have been directed toward non-fuel and non-connectivity activities. Chief amongst these are projects in agriculture and food processing, building materials, finance, industrial parks, and various forms of engineering. The point is, inward foreign investment and trade are interconnected elements of international economic activity, each influencing and complementing the other. To a certain extent, they also facilitate broader strategic goals of Kazakhstan and other economies.

4. Soaring with the Chinese economy?

Several intriguing observations can be discerned thus far. Firstly, China-Kazakhstan trade has declined since 2012, a year before the BRI was announced. Trade volume did not begin to recover until 2017 (see ). Moreover, China-Kazakhstan trade has, as of 2021, failed to reach the levels attained in the early 2010s. There is hardly any basis to support the ‘big bang’ that the BRI was supposed to usher into Kazakhstan, at least within the realm of international trade. This uneven performance, to a large degree, mirrors that of Kazakhstan’s trade with the international economy. It also reflects a fundamental truth of the Kazakhstani economy—it is amongst the largest oil producers in the world. Therefore, its trade performance tends to move with global oil price. Perhaps more interestingly, export and import dependence on China has hitherto been kept at a relatively stable rate, even if there was a growth spurt between 2000 and 2012.

Additionally, Kazakhstan has recorded trade surplus against China from 2000 to 2021. Parallel to this is the lack of convincing evidence to back concerns about China ‘buying up Kazakhstan’ through unequal deals, a notion frequently portrayed in popular media. Analysts versed in global power dynamics would likely emphasize the multi-vectorism at play. They can, for instance, point to the numerous trade partners that have emerged to dilute Kazakhstan’s dependence on any single one since the turn of the twenty first century. The Russian market, in particular, remains important. It consistently ranks among Kazakhstan’s top three markets during the last decades, suggesting the resilience of historical ties. Another interpretation could be that the opportunities offered by China—which by 2010 became the world’s second-largest economy—has given Kazakhstan increased leverage to hedge its relationship with Russia. Yet, this has not generated apparent dissatisfaction in either Beijing or Moscow as it is more advantageous for all parties to maintain a cooperative, rather than zero-sum, relationship.

Secondly, trade between Kazakhstan and China was mostly focused on natural resources during the pre-BRI years, but it has gradually shifted to a more balanced distribution that encompasses intermediate goods, raw materials, and consumer goods after the BRI was introduced. A plausible reason is Kazakhstan’s rich oil and gas deposit, as mentioned previously. In the early stages of development at least, there is relatively little it can offer to its trade partners (including China) apart from oil and gas. However, trade reliance on oil and gas has since been diluted. This could be attributed to the long gestation period of oil and gas projects financed by foreign firms, especially those from China. This partly contradicts Baldakova (Citation2022), who argues that the heavy presence of Chinese FDI in Kazakhstan’s oil and gas industry would stunt the progress of other industries.

Another plausible reason reducing the weightage of oil and gas trade is the considerable influx of Chinese capital goods (see and ). Such import of capital goods, to a certain extent, implies competitive threat for domestic producers of equivalent goods. Yet, these capital goods may allow Kazakhstani firms to engage in other productive responses, ranging from reducing manufacturing cost, improving product quality, to developing more marketable product designs. Although in-depth research on this perspective is essential before a conclusive position is made, certain green shoots can still be inferred. For example, and show that intermediate goods export to China has grown increasingly prominent. and also demonstrate that intermediate goods import has seen its importance (absolute value and market share) reduced over the period analyzed. A similar trajectory, to a smaller extent, is observed for the export and import of consumer goods.

Thirdly, and related to the previous point, China-Kazakhstan trade is simultaneously the cause and effect of an increasingly complex production network. It would be naïve to claim that Chinese firms have not captured key positions in Kazakhstan; they most probably have. Yet, it is just as plausible that their entrance has rejuvenated the local industrial system, resulting in broad-based structural transformation that can hardly be observed through trade analysis alone. One way of unpacking this is to trace the China-Europe Rail Freight (CERF), especially its role in stimulating commercial activities within Kazakhstani territory. This project was started in 2011 and has been pivotal in interlinking selected Chinese cities such as Chongqing and Chengdu to Central Asian as well as European destinations. Based on the evidence gathered thus far, the CERF has seemingly gained acclaim as a convenient, safe, green, and stable international transport provider, in addition to catalyzing socioeconomic exchange and technology transfer between cities along the route (“Belt & Road” Construction Leading Group Office, 2022).

One of the most direct impacts of the CERF is the improvement of Kazakhstan’s cold chain logistics, especially important in facilitating the sales of perishable goods such as animal hides, meat, and grains. This has increased the income of enterprises and farmers who otherwise would have little access to such opportunities. Parallel to this is the growing willingness of business executives from both China and Kazakhstan to visit cities on each side of the border in the search for commercial opportunities. For example, Chinese transnational corporations (TNCs) have cooperated with the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, the Silk Road Fund, and other funding bodies to build new energy projects such as Zanatas wind farm, Turgusun hydropower plant, Almaty photovoltaic power plant, etc., and participate in the modernization of the Chimkent oil refinery (Zhang, Citation2023). These large-scale construction projects have injected vitality into Kazakhstan’s national economic development, filled the gaps in the local industrial complex, and leveraged its natural resource endowment.

Two Chinese cities, in particular, have formed denser ties with Kazakhstan (and by extension, other locales along the CERF). Yiwu, in China’s wealthy Zhejiang province, initially required both land and sea routes to export goods to Central Asian and European countries. This not only caused delays, but also incurred high expenses. After the opening of the Yiwu-Madrid railway line, Yiwu’s import and export to the five Central Asian countries has seen an almost 17-fold increase compared with 10 years ago (He, Citation2023). More technologically advanced goods, such as hardware tools, photovoltaic equipment, machinery, auto parts, and home building materials, now make up majority of exports to Central Asia, moving away from simple, relatively unprocessed commodities (see also Tjia, Citation2023). Yiwu-manufactured goods have also increasingly filled the shelves of supermarkets in several Kazakhstani cities. The faster transportation has facilitated the movement of goods and expanded the variety of products available to the people of Kazakhstan. This has diversified Kazakhstan’s trade with China beyond low-value daily necessities, as was common in the past (He, Citation2023).

Another representative case is Alashankou city on the China-Kazakhstan border. It was originally a modest-sized border post, but in recent years has established itself as one of China’s national first-class ports of entry. In particular, Alashankou’s comprehensive bonded zone has attracted a large number of (Kazakhstani and Chinese) enterprises to move in and facilitate cooperation. Bonded warehouses and their direct sales centers offer a wide selection of goods for business representatives and individual buyers from China, Kazakhstan, and other countries. These facilities shorten the distance from the factories to consumers and reduces potential losses from frequent transfers and customs inspections (Tavrovsky, Citation2017). For example, the reduced import tariff in these bonded warehouses has attracted the attention of Chinese manufactures who import wheat from Kazakhstan before processing it into noodles for sale in China and other export destinations (Sun, Citation2023).

Building on Soong’s (Citation2024) analytical model and the analysis unearthed in this paper, it is logical to infer that Kazakhstan state actors cast a somewhat positive light in their cooperation with China (see ). Absent significant shocks to the preexisting dynamic, China-Kazakhstan relationship during President Xi’s third term is expected to remain primarily driven by economics. As illustrated earlier on, the opportunity to acquire capital and technology from China to modernize Kazakhstan’s economy is especially appealing. Furthermore, Chinese economic support, when handled well, gives Kazakhstan more options to manage relations with other major powers as part of its oft-cited multi-vector foreign policy. Nevertheless, the fear of possible Chinese economic and cultural domination runs deep amongst segments of the population. At least in the foreseeable future, the Kazakhstan government is likely to adopt a hedging strategy, much like it has done in recent years.

Table 2. Kazakhstan’s perception toward President Xi Jinping’s Third Term.

5. Opportunities, challenges, and strategic choices in the age of Xi

How do the above findings inform our understanding of the opportunities and challenges facing Kazakhstan now that the Xi administration is in its third term? It is undeniable that the Chinese economy, plagued by issues ranging from overcapacity and rising debt levels, has decelerated in recent years. However, this does not necessarily mean that Kazakhstan’s economic fortunes will suffer. For example, many of the factors (e.g. China’s search for market access and Kazakhstan’s desire to diversify its oil-rich economy) that fueled the BRI in the past will likely hold sway in the near to medium term. By the same token, strengthening economic relations with China has enabled Kazakhstan to hedge its relations with other powers, in line with its multi-vectorist goals (Murashkin, Citation2020). Notwithstanding the geopolitical rationale behind Kazakhstan’s all-round internationalization, this process involves a range of exchanges not easily captured by formal state institutions. The key here is to take generalizations, oft-repeated in popular media, with a pinch of salt. It is also wise to exercise caution when making decisions based on one-off, anecdotal evidence rather than broader, long-term trends.

As detailed elsewhere (e.g. Dadabaev, Citation2018; Liu & Lim, Citation2019), the degree of freedom accorded to a host state in managing geopolitics is ultimately fueled by economic factors, although such a dynamic is not easily spelt out ex ante. This is just as valid for Kazakhstan. To take one example, the 2022 Russia-Ukraine conflict has disrupted international energy supply, in turn boosting Kazakhstan’s leverage in the sales of its oil and gas. The sanctions imposed by Western powers on Russia have also elevated Kazakhstan’s importance in the eyes of these stakeholders because of the extremely long Russia-Kazakhstan border. The efficacy of any sanctions will, to a large extent, depend on how tightly this border (and others) are monitored. Another example involves the situation in China. China’s escalating tension with the US means that it is even more important for the Chinese to secure other economic partners. Kazakhstan, by virtue of its proximity to China and relatively rich natural resource endowment, provides it with ample opportunities to deepen trade and investment.

However, these opportunities come with challenges. As mentioned previously, Kazakhstan has—throughout its long history—been subject to pressure from China, Russia, and other major powers. Therefore, stereotypes, especially those passed down from earlier generations, do not fade easily. As far as China-Kazakhstan ties are concerned, anti-Chinese sentiment will likely still represent a significant stumbling block. While advancement in communication technology should, in theory at least, facilitate information gathering about Chinese activities in Kazakhstan or elsewhere, it also makes it easier to spread rhetoric of a primordial nature. This seeming paradox will likely linger on for some years, extending beyond the third (and subsequent, if any) term of the Xi administration. A parallel concern can also be raised about some of the Chinese-funded projects. Oft-cited worries include but are not limited to alleged unfair commercial practices and negative impacts on the environment. However, these issues are usually not straightforward, so a more careful, dispassionate survey is recommended. To this end, the Kazakhstan government could adopt a more open, transparent approach in disseminating information to the public, especially for big-ticket projects (not only those financed by the Chinese).

Kazakhstan’s multi-vector foreign policy brings opportunities and challenges alike, especially in view of the tension between China and the West, which seems unlikely to subside in the near future. To leverage the framework put forth by Soong (Citation2024), the opportunities (4.0), while certainly ample, must be viewed in relation to the challenges (4.0), which are arguably just as complex (see ). As the saying goes, in the midst of every crisis, lies great opportunity. It is thus in the interest of both China and Kazakhstan to work on common issues, which over time can generate even more goodwill and trust.

Table 3. Opportunities and challenges for Kazakhstan during President Xi Jinping’s Third Term.

Further insights are evaluated and summarized in . In terms of politics (4.0), there is significant interest from Kazakhstan to engage with China. The overarching goal is not only establishing a peaceful relationship with the Chinese, but also leveraging China’s support to pursue multi-vectorism. When it comes to economics management (4.0), China’s large market and increasingly sophisticated TNCs provide an invaluable route for Kazakhstan to pursue industrialization. Arguably the most challenging aspect is societal level interactions (3.0) as political and economic dealings do not take place in a vacuum. Notwithstanding the potential windfall of greater China-Kazakhstan cooperation in the political and economic realms, it is important to underline that they cannot be decoupled from people-to-people ties. For this purpose, it is prudent to err on the side of caution when it comes to forecasting the degree by which ‘China’s dream’ can come to fruition in Kazakhstan. The point is, so long as societal distrust is not addressed, more ambitious bilateral cooperation will always be compromised. This also suggests that fostering trust between the people of both countries is as crucial, if not more than, as political and economic grand strategies. Taking these factors into account, Chinese presence in the Central Asian nation is likely to grow only slightly between the recent past (3.0) and Xi’s third term (3.5).

Table 4. Strategic choices in response to a rising China.

6. Conclusion

This paper has put forth three arguments, focusing on Kazakhstan’s trade with China. First and foremost, Kazakhstan has not grown reliant on the Chinese economy. Its trade autonomy has been preserved before and after the BRI was announced in 2013. Secondly, China-Kazakhstan trade was centered on natural resources before 2013. Bilateral trade has since evolved into a more balanced mix, encompassing intermediate goods, raw materials, and consumer goods. Last but not least, this trade diversification results from a more intricate value chain linking Kazakhstan to the international economy, including but not limited to China. The increasing complexity of these production networks, while certainly beneficial to Chinese firms, have contributed to Kazakhstan’s multi-vector geopolitical strategy. They have also brought in much-needed Chinese capital, technology, and expertise, fueling Kazakhstan’s industrialization ambitions.

Perhaps belaboring the obvious here, it is important to avoid depicting China-Kazakhstan ties under sweeping, uncritical themes. Just because Kazakhstan occasionally veers away from the Chinese does not automatically mean that it is leaning toward either Russia or other nations and vice versa. There needs to be a more detailed investigation on the issue at hand before a definitive stance is taken. Relatedly, geopolitical upheaval across various global theaters have indirectly opened up opportunities for Kazakhstan. However, these come with challenges too. Some of them are deep-rooted and would not likely be resolved in the near to medium term. The overall expectation is for China-Kazakhstan ties to develop further, but detours and bottlenecks are anticipated along the way. The research reported here has certainly captured important snapshots of the economic relationship tying China and Kazakhstan together. However, its emphasis is on trade. Prospective researchers would do well to explore in greater depth other elements of China-Kazakhstan economic ties such as FDI and official development assistance. Likewise, another fruitful research agenda is to conduct a more fine-grained analysis of how trade flows in particular products were forged, considering local political and economic conditions as well as industry-specific dynamics. Additional attention on these topics would further enrich the scholarship.

Acknowledgement

The authors would want to thank Yeung Pui Kam and Leung Tin Yi for their research assistance. In addition, the authors gratefully acknowledge support from the Library of National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies, Japan in making this paper open access.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Border agreements between Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Russia and Tajikistan and China in the mid-1990s paved the way for the establishment of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation.

2 According to Lo (Citation2022), the rationale for BRI has been anticipated and articulated as early as October 2012 by Chinese scholar Wang Jisi in a paper called ‘Going west, rebalancing China’s geostrategy.’ Originally written in Chinese, his thesis was subsequently edited and translated into English (see Wang, Citation2014).

References

- Abdurasulov, A. (2016). Kazakhstan’s land reform protests explained. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-36163103

- Baldakova, O. (2022). Kazakhstan’s three-way balancing act between competing powers is under pressure. Merics. https://merics.org/en/kazakhstans-three-way-balancing-act-between-competing-powers-under-pressure

- “Belt and Road” Construction Leading Group Office. (2022). National Development and Reform Commission Press Conference to Introduce the “China-Europe Railway Express Development Report (2021). https://www.ndrc.gov.cn/xwdt/wszb/zobl2021ygqk/?code=&state=123

- Bitabarova, A. G. (2018). Unpacking Sino–Central Asian engagement along the new Silk Road: a case study of Kazakhstan. Journal of Contemporary East Asia Studies, 7(2), 149–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/24761028.2018.1553226

- Cooley, A. (2014). Great games, local rules: The new great power contest in Central Asia. Oxford University Press.

- Dadabaev, T. (2018). “Silk Road” as foreign policy discourse: The construction of Chinese, Japanese and Korean engagement strategies in Central Asia. Journal of Eurasian Studies, 9(1), 30–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euras.2017.12.003

- Euromonitor International. (2024). Kazakhstan. https://www.euromonitor.com/kazakhstan

- Harutyunyan, A. (2022). China-Kazakhstan: Cooperation within the Belt and Road and Nurly Zhol. Asian Journal of Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies, 16(3), 281–297. https://doi.org/10.1080/25765949.2022.2128135

- He, X. (2023). A look at ten years of trade between world supermarkets and five Central Asian countries. Tidenews. https://tidenews.com.cn/news.html?id=2473291&from_channel=63e60cad5476b20001d52d62&top_id=2473306

- Ji, X.-B., & Lim, G. (2022). The Chinese way of reforming global economic governance: An analysis of China’s rising role in the group of twenty (G-20). The Chinese Economy, 55(4), 282–292. https://doi.org/10.1080/10971475.2021.1972546

- Kazantsev, A. (2008). Great game with unknown rules: Central Asia and world politics. MGIMO University Press. [In Russian Language].

- Laumulin, M., & Tolipov, F. (2010). “Uzbekistan i Kazakhstan: Bor’ba za liderstvo?” [Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan: A struggle for leadership?] Security Index, 1, 105–128.

- Liu, H., & Lim, G. (2019). The political economy of a rising China in Southeast Asia: Malaysia’s response to the belt and road initiative. Journal of Contemporary China, 28(116), 216–231. https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2018.1511393

- Liu, H., & Lim, G. (2023). When the state goes transnational: The political economy of China’s engagement with Indonesia. Competition & Change, 27(2), 402–421. https://doi.org/10.1177/10245294221103069

- Lo, A. (2022). “How a seminal paper in 2012 predicted our world today.” South China Morning Post, 5 July. https://www.scmp.com/comment/opinion/article/3184198/how-seminal-paper-2012-predicted-our-world-today

- Maclean, W. (2019). Dozens protest against Chinese influence in Kazakhstan. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-kazakhstan-china-protests-idUSKCN1VP1B0/

- Menon, R. (2003). The new great game in Central Asia. Survival, 45(2), 187–204. https://doi.org/10.1093/survival/45.2.187

- Murashkin, N. (2019). Japan and Central Asia: Do diplomacy and business go hand-in-hand? IFRI Center for Asian Studies.

- Murashkin, N. (2020). The belt and road initiative and Sino-Russo-Japanese relations. In D. De Cremer, B. McKern, & J. McGuire (Eds.), The belt and road initiative: Opportunities and challenges of a Chinese economic ambition. Sage.

- Pantucci, R. (2019). China’s complicated relationship with Central Asia. East Asia Forum. https://eastasiaforum.org/2019/10/30/chinas-complicated-relationship-with-central-asia/

- Rana, P. B., & Pardo, R. P. (2018). Rise of complementarity between global and regional financial institutions. Global Policy, 9(2), 231–243. https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-5899.12548

- Simonov, E. (2019). Half China’s investment in Kazakhstan is in oil and gas. China Dialogue. https://chinadialogue.net/en/energy/11613-half-china-s-investment-in-kazakhstan-is-in-oil-and-gas-2/#:∼:text=The%20Kazakhstan%20government%20has%20finally,in%20oil%20and%20gas%20projects.

- Soong, J.-J. (2022). The political economy of China’s rising role in regional international organizations: Are there strategies and policies of the Chinese way considered and applied? The Chinese Economy, 55(4), 243–254. https://doi.org/10.1080/10971475.2021.1972550

- Soong, J.-J. (2024). Opportunities and challenges of China’s economic and political development under the third term of Xi leadership: Ascent of China’s dream? The Chinese Economy. (Forthcoming).

- Sun, S. (2023). Alashankou, Xinjiang: Building an important base for grain storage and processing in the Silk Road economic belt. Xinhuanet. http://xj.news.cn/2023-04/26/c_1129567345.htm

- Swanström, N. (2007). China and Central Asia: A new great game or traditional vassal relations? Journal of Contemporary China, 14(45), 569–584. https://doi.org/10.1080/10670560500205001

- Tavrovsky, Y. (2017). Wings of a great power: A note on the westward journey of the “belt and road initiative.” Central Party School Press.

- Tjia, L. Y. (2022). Kazakhstan’s leverage and economic diversification amid Chinese connectivity dreams. Third World Quarterly, 43(4), 797–822. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2022.2027237

- Tjia, L. Y. (2023). Fragmented but enduring authoritarianism: Supply-side reform and subnational entrepreneurialism in China’s rail delivery services. The China Quarterly, 256, 905–918. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741023000516

- Vanderhill, R., Joireman, S. F., & Tulepbayeva, R. (2020). Between the bear and the dragon: Multivectorism in Kazakhstan as a model strategy for secondary powers. International Affairs, 96(4), 975–993. https://doi.org/10.1093/ia/iiaa061

- Wang, J. (2014). Marching westwards: The rebalancing of China's geostrategy. In B.H. Shao (Ed.), The world in 2020 according to China (pp. 129–136). Brill.

- World Bank. (2019). Belt and road economics: Opportunities and risks of transport corridors. World Bank.

- Zhang, J. (2023). Summary: China and Kazakhstan join hands to jointly build the “Belt and Road” and achieve fruitful results. Xinhuanet. http://www.news.cn/world/2023-05/18/c_1129624141.htm