Abstract

Research into the harassment of politicians and other public officials in Northern America and Western Europe demonstrates that 30–93% of politicians report having experienced harassing or stalking behaviour which can comprise serious risks for the integrity of democracy and government. This leads to intriguing questions such as: what types of threats do politicians face and how do they respond to those threats? This article presents the results of research on those questions in The Netherlands. Semi-structured interviews and Q- methodology were applied to gain insight into the different types of threats and the ways in which aldermen cope with these threats and harassments. The types of threats and harassments are diverse from verbal abuse to physical violence. Q-methodology shows three types of rather different strategies towards threats and harassment. The first attitude is combative and decisive. The second attitude is vulnerable and cautious. The third attitude is down to earth and accepting. These findings are relevant because threats and harassment, unfortunately, are becoming an inevitable part of political life nowadays. More insight into the strategies used by politicians are relevant for fighting threats and harassment towards politicians and to strengthen the resilience of politicians.

INTRODUCTION

Research into the harassment of politicians and other public officials in Northern America and Western Europe demonstrates that 30–93% of politicians report having experienced harassing or stalking behaviour, which can comprise serious risks for the integrity of democracy and government (Adams, Hazelwood, Pitre, Bedars, & Landry, Citation2009; Every-Palmer, Barry-Walsh, & Pathé, Citation2015; Hoffmann, Meloy, & Sheridan, Citation2013; James, Farnham, & Wilson, Citation2013; Pathé, Phillips, Perdacher, & Heffernan, Citation2014). In more than half of the cases, the behaviour takes place in the victim’s private environment, and it consists of physical violence, death threats, libel, and slander and vandalism to private property. The prevailing idea is that more and more polarisation and social coarsening have led to more threats in the last decade, but Dutch research shows that the number of threats against politicians remains more or less the same over the years (Bouwmeester, Holzman, & Franx, Citation2014; Bouwmeester, Holzman, Löb, Abraham, & Nauta, Citation2016; Bouwmeester & Löb, Citation2018) (see ).

TABLE 1 Threats Towards Local Politicians in The Netherlands

However, threats, especially towards mayors, have become increasingly more serious in the last decade because of their role in combating organized crime (Nelen & Kolthoff, Citation2017). Therefore, the Ministry of the Interior recently announced a preventive nationwide security scan for the homes of all mayors in The Netherlands (Van Lieshout, Citation2018). Most threats come from citizens who are not able or willing to accept the outcome of a political decision. They use threatening behaviour or undertake malicious attempts to damage the reputation of the politician in order to affect the way the politician feels, thinks or acts on a political issue. Victimised politicians must deal with adverse consequences such as a degree of fearfulness, concern going out in public or being alone at home, a reduction in social outings, a change in routine, a change in personal relationships and work hours lost due to the incident (Adams et al., Citation2009). There are concerns that threats may interfere with the democratic process (Bjelland, Citation2014). Politicians may be influenced by threats in making decisions. The study presented in this article is part of a broader explorative research project. Its aim is to identify the nature of the threatening behaviour politicians have to face, the coping strategies used to deal with these incidents and the effects of the threatening behaviour on the process and the outcome of decision making. This contribution reports on the nature of the threats, the reasons behind the threats and the attitudes preferred to cope with the threats. The central question is:

In What Way and Why Are Local Politicians (Aldermen) Threatened and How Do They Deal With These Threats?

To answer this question two complementary research methods are used. Semi-structured interviews (N = 35) provide insight into the nature of the threats against aldermen in the local context and the perceived influence of the threats, both from a private and professional perspective. A Q-methodological study (N = 34) is conducted to collect respondents’ attitudes towards coping with threats. This article focuses on aldermen who have felt threatened at any point in their career. This is important because the threatening experience can have an influence on the attitude towards coping with threats and the attitude can influence the behaviour. So attitudes can have a moderating role.

To understand the relationship between aldermen and Dutch society it is relevant to keep in mind that The Netherlands is a decentralized unitary state. Different tasks are carried out at three different government levels (national, provinces, and municipalities). Due to their unique position close to society, the municipalities, over time, received a central position in creating and implementing policy. In the municipalities, the people are represented by the municipal council. The mayor chairs the municipal council and also chairs the Board of Aldermen. The latter forms the council executive and consists of two to nine members. Aldermen play a crucial role in Dutch politics. They are appointed by the municipal council and they can also be recalled by the council. The position of alderman comprises a mix of management, administration and political leadership activities (Figee, Eigeman, & Hilterman, Citation2008). Aldermen have a more political profile than the mayor and tend to be politically bound to a programme. Theoretically, the municipal council has the most power in local politics, but a Dutch study revealed that in the Netherlands the aldermen and the public servants are in power (Reussing, Citation1996).

The article is structured as follows. First, the theoretical background on threats, appraisal, coping, and decision-making is discussed, followed by an account on the design of empirical research. Next, the results of the study and conclusions are presented followed by some recommendations for further research and implications for practice.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

Threatening behaviour presents itself in many varieties ranging from verbal violence, serious threats to physical violence. In this study, a threat is defined as: “any offer to do harm, however, implausible” (Dietz et al., Citation1991, p. 1460) because people have different ways of perceiving threatening behaviour. The perception strongly depends on the context. Being among friends in a bar, the sentence “I know where to find you,” will not be considered threatening but the same sentence expressed during an emotional meeting with an angry and frustrated individual or group during a meeting at the town hall can be perceived as threatening. In addition to context, individual characteristics such as self-efficacy and locus of control are involved in the perception of threatening behaviour. Self-efficacy is “people’s beliefs about their capabilities to exercise control over their own level of functioning and over events that affect their lives” (Bandura, Citation1997, p. 257). Locus of control can be broken down into internal and external orientation. People who believe that they can influence outcomes through their own efforts, skills, and characteristics have an internal orientation, while those who perceive that outcomes are determined by external forces such as luck, chance, fate, and power of others have an external orientation (Millet, Citation2005). Self-efficacy and control are also concepts in the theory of planned behaviour (Ajzen, Citation1991). According to this theory, human behaviour is guided by three kinds of considerations: beliefs about the likely consequences of the behaviour (behavioural beliefs), beliefs about the normative expectations of other people (normative beliefs), and beliefs about the presence of factors that may affect performance of the behaviour (control beliefs). In combination, these beliefs lead to the formation of a behavioural intention. Finally, given a sufficient degree of actual control over the behaviour, people are expected to carry out their intentions when the opportunity arises (Ajzen, Citation2002, p. 665).

Appraisal and Coping

To understand what happens when a person is confronted with a negative event such as a threat, Lazarus and Folkman’s work into stress, appraisals, and coping is relevant. Coping can be defined as “constantly changing cognitive and behavioral efforts to manage specific external and or internal demands that are appraised as taxing or exceeding the resources of the person” (Lazarus & Folkman, Citation1984, p. 41). When a person feels that the external and/or internal demands exceed his/her resources a feeling of stress can occur (Cohen, Kessler, & Gordon, Citation1995). The model “Theory of Cognitive Appraisal” by Lazarus and Folkman (Citation1984) states that when a person is confronted with a potentially stressful situation s/he will evaluate the situation and his or her ability to cope with the situation. When the situation is being evaluated as irrelevant, the person will probably not respond to the situation and life continues as before. When the situation is evaluated as positive (challenge appraisal) the person will most likely focus on profits and positive emotions like trust, hope, diligence, arousal, and an effective use of physiological means (Blascovich, Seery, Mugridge, Norris, & Weisbuch, Citation2004; Delahaij & Gaillard, Citation2008; Folkman & Lazarus, Citation1985). These positive emotions can lead to a more optimistic evaluation of the situation even when the emotions are not directly related to the threat. When a person evaluates the situation as a threat (threat appraisal) s/he will probably focus on possible losses and negative emotions like fear, anger and anxiety and a higher state of arousal. Negative emotions can cause a person to believe that there is a high probability that the threat will be carried out (Rottenstreich & Hsee, Citation2001). There are several ways to classify coping. In this study, the classification made by Connor-Smith and Flachsbart (Citation2007) is being used. These authors make a distinction between voluntary (controlled) versus involuntary (automatic) responses. Both voluntary and involuntary responses to stress can be further broken down into efforts to engage or disengage from the stressor and one’s responses (Skinner, Edge, Altman, & Sherwood, Citation2003). If a person feels he is in control of the situation s/he will probably choose an engagement coping strategy which enables him to control his emotions or the situation. With a disengagement strategy, s/he will probably try to disassociate himself/herself from his/her emotions or from the stressful situation. Voluntary engagement coping can be divided into primary (active coping) and secondary coping. Primary coping aims at changing the emotions or the situation and involves strategies such as problem solving, emotional expression and emotional, or instrumental support seeking. Secondary coping aims at adapting oneself to the emotion or the situation. This involves strategies as acceptance, distraction, cognitive restructuring, or positive thinking. In this study, a difference is made between coping style and coping strategy. Coping style is intentional behaviour and coping strategy is the actual behaviour.

The effectiveness of the coping strategy depends on personal goals and objectives. In this study, a coping strategy is defined as an effective strategy if the person acts as he would have done when he did not feel threatened, and there is no influence on the process or the outcome of decision-making. It is conceivable, however, that threats lead to an ineffective coping strategy that can influence decision-making. There is an influence when, in a relationship between the actors A and B, actor A, by his presence, thoughts or actions, causes actor B to serve A’s interests or purposes more than B would have done without A (Huberts, Citation1988, p. 20). Threats have a negative influence on functioning (Adams et al., Citation2009) and may interfere with the democratic process (Bjelland, Citation2014). Some of the respondents (15%) from the Dutch study by Bouwmeester and Löb (Citation2018) think that colleagues are influenced by threats in decision-making, and 6% think their own decisions are influenced by threats. The context in which public decision-making takes place is changing rapidly. Broad social, political, and economic developments, such as individualisation, globalisation, and information technology (Boutellier, Citation2011) have a profound influence on how public problems are solved (public governance). Public policy decisions are no longer fully controlled by the government, but subject to negotiations between a wide range of public, semi-public, and private actors (Mayntz, Citation1993a, Citation1993b). The checks and balances used to counteract undue influence such as rules and procedures may be under pressure.

Hunters and Howlers

Many perpetrators only express frustration, and never intend to do harm. This group is called “howlers.” Perpetrators who seriously intend to do harm are called “hunters” (Calhoun, Citation1998).

Meloy and colleagues (Citation2004) have compared various international studies on perpetrators and find some striking similarities. For instance: in many cases, personal motives are involved, perpetrators often approach different victims within a specific case, many perpetrators are not driven by aggression but are looking for help, satisfaction, or a person who is willing to listen. Being rejected can encourage feelings of anger and frustration. Direct verbal threats seem to reduce the chances of implementing the threat but must always be taken seriously. A significant part of all perpetrators is mentally ill and a significant part has a criminal background. Many of them are not feeling well in the months prior to the threat.

METHODOLOGY

This contribution reports on the nature of the threats and the attitudes preferred by aldermen to cope with the threats. The central question is:

In what way and why are local politicians (aldermen) threatened and how do they deal with these threats?To answer this question two complementary research methods were used. A Q-methodological study followed by semi structured interviews that provided insight into the nature of the threats against aldermen in the local context and the perceived influence of the threats, both from a private and professional perspective.

The study was announced in a newsletter published by the association of aldermen. All members (N = 750) were informed and aldermen who have felt threatened at one point in their career were invited to participate. This was important because former experiences affect coping styles. The aldermen could sign up for the study by sending an e-mail to the researcher. This invitation elicited 25 useful responses. Besides, eight aldermen were contacted directly because their names came up in media analyses and two respondents were recruited using snowball-sampling (Boeije, Citation2010). Eventually, 35 aldermen participated in the study. One of the aldermen did not participate in the Q-methodological part of the interview phase.

Q-Methodology

Q-methodology was introduced in 1935, by British physicist/psychologist William Stephenson (Brown, Citation1996; Stephenson, Citation1953). It is a method in which the respondent’s subjective experience is key. At first, Q methodology was practiced in the academic field of psychology but it has since been applied in different fields such as communication and political science, and more recently in the behavioural and health sciences (Brown, Citation1997). Q methodological studies are characterised by two main features: (1) the collection of data in the form of Q sorts, and (2) the subsequent intercorrelation and by-person factor analysis of those Q sorts (Watts & Stenner, Citation2012, p. 178). A Q sort is a collection of items which are sorted by participants from their individual point of view, according to some preference, judgement, or feeling about them, mostly yielding a quasi-normal distribution (Exel & de Graaf, Citation2005). These individual rankings (or viewpoints) are then subject to factor analysis. The calculations necessary to facilitate factor interpretation are provided with the help of specialised Q-methodology software PQMethod version 2.33 (Schmolck, Citation2002).

Semi-Structured Interviews

After the Q-methodological study, the respondents were interviewed. These interviews provided insight into the nature of the threats against aldermen in the local context and the perceived influence of the threats, both from a private and professional perspective. The interviews were semi structured. An interview schedule was designed with key questions. The first question was an open question in which the respondent was invited to tell what had happened to him/her and how s/he coped with the situation. Further questions were asked about (1) perpetrator characteristics such as background and motives; (2) personal characteristics such as self-efficacy, locus of control, and governance style; (3) the local context such as political culture, relationship with the media; and (4) the effects of the situation on their private lives and the process of decision making as perceived by the respondent. All interviews were recorded and transcribed literally. All respondents were guaranteed that their identities would not be made public. The transcribed interviews amounted to a great deal of data and were coded in various steps. The questions in the interviews were the basis of the main codes developed. Different types of codes (thematic and descriptive) were derived from the data. Once the coding was developed, open codes were added to function as sub-codes, making it possible to detect patterns. The software programme NVivo was used to help organise and analyse the interviews.

RESEARCH

Q-Methodological Study (Q-Study)

The main question for this Q methodological study was: “How do aldermen feel about and respond to a situation they perceive as threatening?”

Performing a Q methodological study involves the following steps: (1) definition of the concourse; (2) development of the Q sample; (3) selection of the P set; (4) Q sorting; and (5) analysis and interpretation (Exel & de Graaf, Citation2005). The steps will be discussed in more detail in the section below.

Definition of the Concourse

Thirty-four aldermen were asked to rank-order thirty-four opinion statements (Q-set) about coping with threats related to the job. Opinion statements were collected through personal interviews with politicians (who had or had not felt threatened at any point in their political career and did not participate in the Q-study) and literature on coping (e.g., Skinner et al., Citation2003; Spirito, Stark, & Williams, Citation1988; Tummers, Bekkers, Vink, & Musheno, Citation2015). The collection of items is called the concourse. At first, the concourse contained statements related to different themes ranging from offender characteristics, prevalent coping mechanisms, managerial styles to the effects of social processes such as mediatisation, and individualisation.

Development of the Q Sample

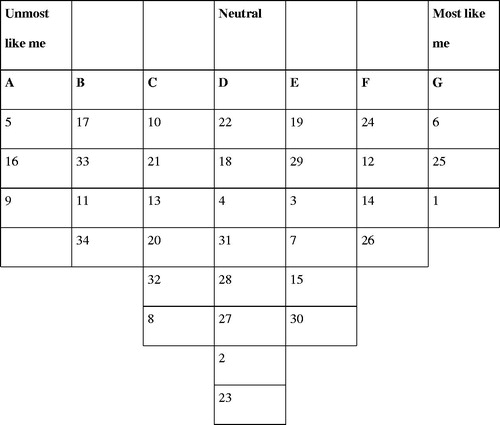

To judge the understandability of the statements members of the Centre of Expertise on Public Safety (part of Avans University) were asked to rank order the statements from their individual point of view using a quasi-normal distribution (Exel & de Graaf, Citation2005). The diversity of themes made it difficult to rank-order the statements. Therefore the research opted for a Q set comprising only frequently used scales in coping questionnaires such as Folkman & Lazarus’s Ways of Coping Questionnaire (Folkman & Lazarus, Citation1988) and the COPE (Carver, Scheier, & Weintraub, Citation1989). Eight scales were used (problem solving, seeking social support, expressing emotions, positive reinterpretation, disengagement, palliative responses, avoidance, and passive reaction patterns). All scales contained four to six statements, the Q-sample consisted of 45 statements. To ensure content validity, these sample statements were reviewed by fellow researchers and tested in two pilot studies among local politicians. After removing unclear formulations and duplications the final Q-set (see ) consisted of 34 statements.

TABLE 2 Factor-Exemplifying or Factor-Defining Q Sorts for Three Factors

TABLE 3 Factor Q-Sort Value for Each Statement

Selection of the Participants P-Set

The selection of participants is guided by the principle that there should be as many points of view on the subject as possible (Brown, Citation1980). How many times these points of view occur is not relevant. The same applies to the number of respondents. It is important, however, that the number of respondents is sufficient to structure a number of factors that represent different views as categories of response (Brown, Citation1980).

Aldermen in The Netherlands constitute a homogeneous group of mainly white males (21% is female), middle aged (54.4 years old) and highly educated (University Bachelor level 45%, University Master level, 38%). Most aldermen are members of a local political party and have been active in politics before they became an alderman (Vulperhorst, Citation2010). The aldermen participating in this study resemble the general picture. Thirty-one of them were male (there were three female aldermen participating but unfortunately only two of them actually sorted the statements), highly educated (except for one), middle aged (40–68 years), and many of them had been a member of the City Council, a public servant or an executive before they became alderman. Eleven aldermen belong to a local political party, the remaining belong to parties operating on a national scale. The distribution over the national political parties is as follows: eight aldermen belong to Christian Democrats (CDA), two aldermen are a member of Democrats’66 (D’66), five aldermen are a member of the Labour Party PvdA and eight belong to the Liberal Party VVD. Four alderman work in a city that has over 100,000 inhabitants, seven work in a medium-size city (50,000–99,000 inhabitants) and twenty-one work in a small city (15,000–49,000 inhabitants). All aldermen participated voluntarily. They signed an informed consent declaration and were guaranteed that their data remained anonymous.

Administering the Q-Sort (Procedure)

The participants were asked to sort the statements into three piles of categories: Category I for statements they definitely agreed on, Category II the ones they definitely disagreed on and Category III for those statements about which they felt indifferent or unsure about. The participants then returned to the three piles and sorted them in a more fine-grained way using a scale ranging from −3, unmost like me through 0 neutral to 3 most like me. In the distribution, however, these numbers were replaced by letters from (A), unmost like me, through (D) neutral to (G) most like me because during the pretests participants strongly reacted to the negative number. They felt uncomfortable putting statements in the “minus” category. Three statements were placed in the extremes and the majority were placed towards the centre, resulting in a normal distribution (see ).

The individual Q sorts were captured on photo. After the sorting, the participant was asked to explain the choices s/he had made. The explanations of the choices made and the semi-structured interviews took 60–90 min and were used in the analysis and the interpretation and descriptions of the factors.

Results and Analysis

A total of 34 Q sorts were included in the analysis. Correlation and factor analysis were applied with the help of the dedicated computer package PQ method (Schmolck, Citation2002). At first, five factors were extracted because it is suggested that one factor should be extracted for every six Q sorts in the study (Watts & Stenner, Citation2012), which would suggest five or six should be extracted for this study. Then the Kaiser–Guttman Criterion was used to support the process of decision making on how many factors should be retained. This criterion stipulates that all factors with an Eigenvalue of more than 1.00 should be retained (Watts & Stenner, Citation2012). In this study, four factors had an Eigenvalue higher than 1.00. The second criterion used to support the process of decision making on how many factors should be retained, and is the number of significantly loading Q sorts on a factor. It is recommended that each factor should have at least 2 Q sorts that load significantly on it. To ascertain whether a Q sort loads significantly on a factor at the 0.01 level the following calculation is used (Brown, Citation1980): = 2.58×(1 ÷ √no. of items in Q set). Applied to this research: = 2.58 × 0.1715 = 0.44. The application of this criterion to the unrotated factor matrix suggests that three factors should be retained for rotation and further analysis. Three factors were extracted and rotated, which together explained 53% of the study variance. Of all Q sorts, 29 loaded significantly on one of the three factors (see ).

The Q sorts loading significantly on the same factor are those that share a similar sorting pattern and as a result, it can be assumed that the 12 exemplars of factor 1, the 8 exemplars of factor 2, and the 8 exemplars of factor 3 share a distinct way of coping with threats (Stenner, Cooper, & Skevington, Citation2003) (see ).

The table contains the factor arrays for each of the study factors.

Factor interpretation takes the form of a careful and holistic inspection of the patterning of statements in the factor array (Stenner et al., Citation2003). The overall aim of factor interpretation is to uncover, understand and explain the viewpoint captured by the interrelationship of the many items within the factor (Watts & Stenner, Citation2012). For the interpretation of the factor arrays, the most distinguishing statements (+3, +2, −3, and −2) were examined as well as the statements that stimulated the most disagreement. The remarks made by the respondents after the Q sort were used to facilitate the interpretation of the analysis results. In the following paragraph, description of each factor group is presented with some demographic details of the participants who’s Q-sorts loaded significantly on the factor. Rankings of relevant items are provided. For example (12: +3) indicates that item 12 is ranked in the +3 position in the factor array Q sort of factor … Comments made by participants associated with a factor are cited where they clarify the interpretation.

RESULTS Q-METHODOLOGICAL STUDY

The Q sorts show three types of rather different attitudes towards coping with threats. To easily distinguish between the different strategies names were given to them. The first attitude is called “combative and decisive,” the second attitude is called “vulnerable and cautious” and the third type is called “down to earth and accepting.”

Attitude 1: Combative and Decisive

The aldermen associated with this attitude are passionate about their profession. They see it as a privilege more than a job. They prefer to use engaged coping like problem solving and analysing (3, +3). “When you are in a threatening situation, it never resolves itself. That is not possible. You will always need to take action.” The actions can differ. For some, it means trying to find the offender just to: “Put an end to a threatening situation.” Others report the incident with the police just: “To be able to do something.” Within this attitude, one relies on personal skills rather than rules and procedures (28, −2) to solve the situation. They think it is important to seek support from people they trust (6, +3). The support can be instrumental or emotional: “When something like this happens, you need to talk about it, to share your thoughts, make other people complicit otherwise you become vulnerable and open to blackmail.” They also intend to use secondary coping like cognitive reconstruction: “I probably think to myself, all right, fortunately there’s only one person that hates me so bad. Imagine there would be more. So there’s an advantage.”

The thought of being threatened makes them angry, frustrated and agitated. Especially towards the perpetrator: “I could imagine hiring someone to threaten the perpetrator, to flatten her tires or to do her harm. That’s the kind of thoughts that keep me busy.” The thought of being threatened makes them fearful, especially when it is an anonymous threat. “In the supermarket I couldn’t stop thinking: ‘you could be the offender, or you, or maybe it’s you’.” They are concerned about their families (30, +2): “You feel helpless, when they touch your children, your family, it becomes too close.” But they also are combative: “I say to myself: ‘this will not happen to me, this is not how it will be.” The persons represented by this strategy consider themselves to be fighters: “When it comes to fight, freeze or flight than I’m a fighter. That’s who I am.”

Attitude 1 has an eigenvalue (an eigenvalue is the sum of squared loadings for a factor; it conceptually represents the amount of variance accounted for by a factor) of 13.6 and explains 22% of the study variance. Twelve participants are significantly associated with this factor. Ten of them are male, two are female. Their average age is 53.9 years. Four aldermen associated with this attitude belong to a local political party, one alderman is a member of PvdA, and three belong to VVD, one to D’66 and one to CDA. Eleven participants work in a small city (15,000– 49,000 inhabitants). All participants are highly educated and their portfolios differ. They all experienced threatening behaviour towards them during their careers. Almost all incidents (8) associated with this group infringed on the privacy of the participant. Some participants associated with this attitude were confronted with threatening communication or behaviour not only in the private sphere but also at the office and in the public sphere (e.g., a church). Most incidents had an instrumental aim: the offender wanted to affect the way the alderman thought or acted on a political issue. In four cases the aim was unclear: in one case it seemed like an emotional threat caused by a psychotic offender. Two other cases seemed to have an instrumental aim but formally the offender was unknown. In one case the offender was known but the aim was unclear.

Attitude 2: Vulnerable and Cautious

The aldermen associated with this attitude think it is important to establish a connection with others via content. They value cooperation. Being an alderman is like being a manager. They are not political figures. They also have strong feelings and emotions towards coping with threats, but compared to the aldermen associated with attitude 1, their feelings and emotions are focused on the possible consequences (e.g., reputational damage) instead of feelings of anger towards the situation or the perpetrator. Most distinctive of the “vulnerable and cautious” attitude is “maintaining control.” The possible lack of control makes them doubtful. “You don’t know what’s happening, you probably become doubtful; what is going on, what am I doing wrong? So you become very insecure. You don’t know how to react.” They also prefer engaged primary and secondary coping strategies such as seeking social and instrumental support, distraction, and creating an emotional distance. “you just try to take it professionally, they are talking to the alderman, not to me. of course that is difficult because when you look in the mirror you only see one person.”

In contrast to the aldermen associated with attitude 1, these aldermen are more aware of the fact that they will need others to solve the situation (8, −2). Persons represented by attitude 2 believe you have to come forward and talk about what happened, you should never keep it to yourself (20, −3). “You share your doubts and a threat is a doubt because it is not acceptable for people to use threatening communication or behavior and because there is a chance that unintentionally, your conduct follows your fear one way or another. You may show different behavior and then it’s useful for your colleagues to know where this comes from.” Distraction (engaged secondary coping) is used to create space to think about a solution: “Music always helps me to clear my mind, to find an out of the box solution.” In contrast to the first attitude, there is no need to combat confrontation. Worries about the family are present in all factors but in contrast to the first attitude the respondents in this attitude tend to feel guilty (22, +2). They are sure that threats have an effect on the process of decision making: “Of course it has an effect and everybody that denies that is not being honest. Of course it touches you as a person. And not all incidents have the same effect but it is clear that is has an effect on the process.”

Attitude 2 has an eigenvalue of 1.9 and explains 16% of the study variance. Eight participants (all male) are significantly associated with this factor. Their average age is 58.8 years. One alderman belongs to a local political party, two aldermen are members of PvdA, three belong to VVD, and one-two to CDA. Seven participants work in a small city, one works in a city with over 100,000 inhabitants. Seven participants are highly educated and their portfolios differ. Participants associated with this factor have been confronted with threats both at work and at home. Five participants were threatened at home and three at work. In seven cases, the offender had a clear aim. In one case the aim was reputational damage and in another case, reputational damage was used to reach another goal. In three cases the offender was formally unknown.

Attitude 3: Down to Earth and Accepting

Most distinctive for the “down to earth and accepting” attitude is the absence of emotions. The aldermen associated most with this attitude prefer disengaged coping strategies such as avoidance and acceptance. “It’s all part of the game nowadays, there nothing I can do, I have to accept that.” Optimism is important for them (14, +3), and they tend to think that a threatening situation will probably solve itself in time (18, +2). They always try to put things in perspective (29, +3): “I always try to stay optimistic and to put things in perspective, yes I’m an expert at that.” They prefer to think things over (4, +3) before they take action. Contrary to the other attitudes, the aldermen associated with this attitude prefer to keep a threatening situation to themselves as much as possible. They would only talk to colleagues of which they know they have been there as well and then it would be about the information on rules and procedures, it would not be about social support. The aldermen associated with this attitude are less worried about their families (30, 1) than the aldermen associated with the other attitudes (30, 2, 30, and 2). They prefer positive reconstructing coping: “Secured houses are okay. You can always check who’s at the door when you’re not at home. Convenient to see the boyfriends.” Some participants associated with this attitude actor worry about the role of the media in relation to threats. They feel like local newspapers have a tendency to overestimate the incidents and force you to do the one thing you do not want to do: talk to people about it.” They believe that a confrontation with a threatening situation will not affect them. In contrast to factors, they aldermen associated with this group strongly reject the statement: “I consider and I sometimes take a decision that I would not have taken otherwise. Not 180° the other way around but 10°, 20°, or 30°” (5, −3). “You need to support your own decision, you are accountable to the town council for those decisions and that is it. That is how it should be.”

Attitude 3 has an eigenvalue of 2.5 and explains 14% of the study variance. Nine participants (all male) are significantly associated with this factor. Their average age is 57.6 years. Two aldermen belong to a local political party, two aldermen are members of VVD, four belong to CDA and one to PvdA. Five participants work in a small city, one works in a medium-size city and three work in a city with over 100,000 inhabitants. All participants are highly educated and their portfolios differ. Six participants associated with this attitude were threatened at home or in a public space (e.g., a church). One perpetrator used social media. All the other threats took place at work. Five times the aim was clear, four times the perpetrator was unknown and the aim unclear.

In attitudes 1 and 2, the aldermen express strong emotions towards the phenomenon. They prefer engaged coping strategies and emotions. The aldermen associated with attitude 3 express hardly any emotions. Rationality dominates, and they prefer a combination of engaged and disengaged coping strategies.

Optimism and self-efficacy are distinctive in all strategies. The respondents hardly think about their own physical safety, but they all mention the physical safety of their loved ones. They do not think that a threat will affect the outcome of decision-making, but the aldermen associated with attitude 2 cannot rule out an effect on the process of decision-making.

RESULTS SEMI-STRUCTURED INTERVIEWS

The semi-structured interviews took place directly after sorting the statements in the Q-methodological study. The objective was to gain insight into the different types of threats, the feelings, emotions, and the actual behaviour during the threat.

Categories of Threats

The aldermen (N = 35) who participated in this study have been confronted with different types of threats, not only individually but also towards their families and private property. During the interviews, 64 incidents were discussed. All these incidents were deliberately used to cause fear or concern, to emotionally disrupt the alderman (9), or to force a decision (53). Most perpetrators seek physical contact. A second group uses letters, telephone calls, e-mails, and social media applications to seek contact, and a few perpetrators send objects to the alderman (bullets, powder, and flowers). Most of the incidents described by the aldermen took place in their private environment. The appraisal of a situation is influenced by the background of the perpetrator, his goal, and the extent to which the threat touches on the privacy of the alderman. A threat expressed by an anonymous perpetrator without a clear goal in the private sphere of the alderman is generally perceived as very threatening. During the interviews, some incidents were discussed that involved the use of threatening or abusive language on social media applications. Most aldermen did not perceive these incidents as threatening, but they are important because they signal a concern (see ).

TABLE 4 Overview of Threats Classified Into Categories, Duration and Type of Action

A distinction is made between the duration and the nature of the threat; some threats occur only once or a few times (stalking), whereas others continue for more than two weeks (harassment). This distinction marks a turning point regarding the impact of the threat on the victim (Mullen, Pathé, & Purcell, Citation2009). Shouting, cursing, provoking, and/or intimidating the alderman in his office may happen only once, but it can also occur repeatedly. Most incidents in this study can be classified as category II incidents. In this category, the incidents last longer. There are no indications that there is a link between the type of incident and age, experience, political background or portfolio. The incidents relate to several portfolios in which caravans in fixed locations (6), traffic (5), asylum seekers (3), cutting trees (2), and the construction of a mosque (2) appear several times. The women that participated in the study did not face physical violence. More than half of the respondents (18) faced more than one incident during their career as an alderman. Some also faced incidents during former careers in the army, the police force or as a researcher.

Libel and Slander

Libel and slander are mentioned several times and are perceived as threatening especially when media attention is involved. Many aldermen express their concern about the reputational damage caused. It undermines the credibility of the alderman involved and it makes it difficult to move on: “Articles published on the Internet are there to stay and that makes it difficult to move on.” Somebody else: “I couldn’t find another job because they googled me.” The reputational damage is not limited to the individual alderman but can also be branch related: “The threats, the physical violence, the stories on the Internet, the way the media approaches us. In consequence fewer highly educated and skilled people end up in local politics. When you try to put together an electoral roll you constantly hear people say: ‘but I am not going to put my reputation at stake in that circus’.” On the other hand, they do realise that publicity related to integrity violations at (local) government level undermines trust in that same government.

Emotions

All participants expressed concerns about their families, some aldermen also express feelings of guilt towards their families. For some aldermen, the memory of the threat brings up strong negative emotions when they talk about it. But the emotions are not always negative. Some aldermen mention positive emotions like personal growth, pride, and relief.

APPRAISAL AND COPING

The use of Q-methodology provided three different attitudes towards coping with threats. During the interviews, all aldermen described the use of engaged coping strategies such as problem solving, emotion regulation, support seeking (social and instrumental), acceptance, distraction, and cognitive reconstruction. The aldermen associated with attitude 1 use engaged coping strategies such as problem solving, emotion regulation, and seeking social support, aimed at changing the emotions or the situation. The aldermen associated with attitude 2 use engaged coping strategies such as cognitive restructuring, distraction, and acceptance, aimed at adapting oneself to the situation. In scientific literature on coping it is assumed that engaged coping strategies aimed at changing the emotions or the situation are more effective when the situation is controllable. Engaged coping strategies aimed at adapting oneself to the emotion or the situation are more adaptive when a person has no control over the situation (e.g., Ben-Zur, Citation1999; Cohen, Ben-Zur, & Rosenfeld, Citation2008; Endler, Speer, Johnson, & Flett, Citation2000; Folkman, Lazarus, Dunkel-Schetter, DeLongis, & Gruen, Citation1986; Folkman & Moskowitz, Citation2004; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984; Park, Folkman, & Bostrom, Citation2001; Strentz & Auerbach, Citation1988; Terry & Hynes, Citation1998). The aldermen associated with attitude 3 use secondary engagement strategies such as cognitive her structuring and acceptance combined with disengagement coping strategies such as denial and avoidance. The aldermen’s confidence in their ability to cope with the situation is high in all attitudes but emotions like excitement, optimism, anger, fear, and indignation affect the appraisal of the situation. Positive emotions like optimism are associated with challenge appraisal. Those emotions are present in all attitudes. In the appraisal of a challenge, people see the opportunity to prove themselves, gaining profit and personal growth. Negative emotions like anger (attitude 1), fear and indignation (attitude 2) are associated with threat appraisal. In the appraisal of a threat, people feel insecure about their resources to cope with the stressor and, therefore, perceive the situation as less controllable (Blascovich et al., Citation2004; Delahaij & Gaillard, Citation2008; Folkman & Lazarus, Citation1985). The aldermen associated with attitude 1 largely appraise the situation as challenging, the aldermen associated with attitude 2 appraise the situation as threatening. The aldermen associated with attitude 3 largely appraise the situation as “neutral.” Situational characteristics such as a negative governmental culture can affect the process of coping with threats in a negative way. Some aldermen (especially those associated with attitude 2) felt that their concerns were not taken seriously and their need for social or instrumental support was ignored. They became more persistent or more cautious in the decision making process (see ).

All respondents associated with the attitudes described in this study believe threats can have an effect on the process of decision making but only the respondents associated with attitudes 1 and 2 believe threats can also have an effect on the outcome.

TABLE 5 Coping Strategies and Effect on the Process and Outcome of Decision Making

Most politicians that participated in this study function as normal during the incident. They were able to quickly recover to a state of normal functioning and did not develop psycho-social complaints (Bonanno, Citation2004; Bonanno & Mancini, Citation2008). This could be explained by the fact that all the aldermen who have participated in this study were willing to speak frankly face to face about their experiences. It is not inconceivable that in the group of aldermen who were threatened and did not participate in the research other experiences occurred.

In a comparative case study that was carried out in three cases representing the three distinguished attitudes as a follow-up on the study presented in this article, we concluded that threats can indeed influence the process of decision making but in none of the cases the threats had influence on the actual outcome of that process (Marijnissen, Citation2019).

Conclusions

Based on our Q-study we distinguish three different types of attitudes towards threats. The interviews showed that these attitudes largely resemble the actual coping strategies used during the real-life threats our aldermen-respondents experienced. All alderman described the use of different engaged coping strategies, according to the corresponding type we found for them in the Q-study. These preferences give an indication of the coping strategies used under stress (Carver & Scheier, Citation1994; Delahaij, Citation2009; Endler & Parker, Citation1994; Matthews & Campbell, Citation1998). The predictive value of these strategies towards coping with threats can be helpful in coaching processes and training. Emotions play an important role in appraisal and coping processes. Training to learn to recognise and understand ones’ feelings and emotions seems to be useful. In relation to emotion regulation, it is relevant to address that some aldermen stopped working for a few days during the threatening situation, but most of them continued to work. In their own words, they hardly suffered any consequences from the respective threat. Nevertheless, several aldermen were very emotional during the interviews, even many years after the incident. It is recommended to set up an appropriate debriefing and aftercare programme for aldermen in which the psychosocial consequences of threats are discussed. It is also recommended to give structural attention to psychological counselling during (and after) a threatening situation. This can be done by means of so-called sounding board sessions with experts, in which the involvement of the partner is also important.

The interviews indicate that management culture affects the process of coping with threats. When aldermen see each other as competitors and trust and cooperation are not obvious, vulnerability is concealed and there is little room for emotions and dialogue with serious risks for the integrity of the democratic and administrative process (Huberts, Citation2014; De Graaf & Huberts, Citation2008). Safe working conditions must be stimulated to enable aldermen to show their vulnerability, share their worries and feelings and, if necessary, seek support.

The analyses of the data received from the interviews indicate that threats are not isolated actions. In several cases civil servants and colleagues also receive threats. These signals are still not taken seriously and are rarely shared. It is important to take all signals seriously, to record them and, if necessary, to share them to prevent undue influence, escalations, and copycat behaviour. It is important to review and extend the application of existing protocols regarding threatening situations, especially when it comes to internal communication. Not only because timely and unambiguous internal information can serve as a warning (see prevention) but also limit the negative impact of threats in relation to decision-making (four-eye principle).

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR FURTHER RESEARCH

The data analysed in this study are collected by means of qualitative methods. Although the results cannot be generalised because of the applied methodology, the findings give reason to believe that threats have a negative impact on the performance and the mental well-being of the victimised politicians which in turn can impact public integrity. More quantitative research is necessary to gain a good understanding of the scope of the problem. Based on the findings of this study, case studies are suggested to further investigate and test the relationship between appraisal, coping and the influence of threats on (the process of) decision making.

Handling Reputational Damage

The respondents are concerned about the reputation of the profession. This concern is partly due to the behaviour of some members of the profession, but also because the threats can deter a new generation of potentially suitable alderman candidates. As far as is known, there is no research that investigates the influence of threats on the reputation of the profession. To be able to determine whether the recruitment basis for aldermen from councils is indeed reduced by threats, large-scale research may be desirable.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors

References

- Adams, S., Hazelwood, T., Pitre, N., Bedars, T., & Landry, S. (2009). Harassment of members of parliament and the legislative assemblies in Canada by individuals believed to be mentally disordered. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 20(6), 801–814. doi:10.1080/14789940903174063

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. doi:10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

- Ajzen, I. (2002). Perceived behavioral control, self-efficacy, locus of control, and the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 32(4), 665–683. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.2002.tb00236.x

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York, NY: W.H. Freeman.

- Ben-Zur, H. (1999). The effectiveness of coping meta-strategies: Perceived efficiency, emotional correlates and cognitive performance. Personality and Individual Differences, 26(5), 923–939. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(98)00198-6

- Bjelland, B. (2014). Trusler og trusselhendelser mot politikere: En spørreundersøkelse blant norske stortingsrepresentante rog regjeringsmedlemmer. Oslo, Norway: Politihøgskolen.

- Blascovich, J., Seery, M., Mugridge, C., Norris, K., & Weisbuch, M. (2004). Predicting athletic performance from cardiovascular indexes of challenge and threat. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 40(5), 683–688. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2003.10.007

- Boeije, H. (2010). Analysis in qualitative research. London, UK: SAGE Publications.

- Bonanno, G. A. (2004). Loss, trauma and human resilience: Have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely aversive events? American Psychologist, 59(1), 20–28. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.59.1.20

- Bonanno, G. A., & Mancini, A. D. (2008). The human capacity to thrive in the face of potential trauma. Pediatrics, 121(2), 369–375. doi:10.1542/peds.2007-1648

- Boutellier, H. (2011). De improvisatiemaatschappij. Over de sociale ordening van een onbegrensde wereld. Den Haag, The Netherlands: Boom Lemma Uitgevers.

- Bouwmeester, J., Holzman, M., & Franx, K. (2014). Monitor agressie en geweld openbaar bestuur 2014. Hoorn, The Netherlands: I&O Research.

- Bouwmeester, J., Holzman, M., Löb, N., Abraham, M., & Nauta, O. (2016). Monitor integriteit en veiligheid openbaar bestuur 2016. Hoorn, The Netherlands: I&O Research.

- Bouwmeester, J., & Löb, N. (2018). Monitor agressie en geweld. (Vol. 2018). Hoorn, The Netherlands: I&O Research.

- Brown, S. (1980). Political subjectivity. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Brown, S. (1996). Q methodology and qualitative research. Qualitative Health Research, 6(4), 561–567. doi:10.1177/104973239600600408

- Brown, S. (1997). The history and principles of Q methodology in psychology and the social sciences. Kent, OH: Department of Political Science, Kent State University.

- Calhoun, F. S. (1998). Hunters and howlers: Threats and violence against federal judicial officials in the United States, 1789-1993. Arlington, VA: U.S. Dept. of Justice, U.S. Marshals Service.

- Carver, C. S., & Scheier, M. F. (1994). Situational coping and coping dispositions in a stressful transaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 66(1), 184–195. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.66.1.184

- Carver, C. S., Scheier, M. F., & Weintraub, J. K. (1989). Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically based approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56(2), 267–283. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.56.2.267

- Cohen, M., Ben-Zur, H., & Rosenfeld, M. (2008). Sense of coherence, coping strategies, and test-anxiety as predictors of test performance among college students. International Journal of Stress Management, 15(3), 289–303. doi:10.1037/1072-5245.15.3.289

- Cohen, S., Kessler, R., & Gordon, L. U. (1995). Measuring stress: A guide for health and social scientists. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Connor-Smith, J., & Flachsbart, C. (2007). Relations between personality and coping: A meta-analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93(6), 1080–1107. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.93.6.1080

- De Graaf, G., & Huberts, L. (2008). Portraying the nature of corruption. Using an explorative case-study design. Public Administration Review, 68(4), 640–653. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6210.2008.00904.x

- Delahaij, R. (2009). Coping under acute stress: The role of person characteristics. Breda: Koninklijke Broese & Peereboom.

- Delahaij, R., & Gaillard, A. (2008). Individual differences in performance under acute stress. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting, 52(14), 965–969. doi:10.1177/154193120805201403

- Dietz, P., Matthews, D., Martell, D., Stewart, T., Hrouda, D., & Warren, J. (1991). Threatening and otherwise inappropriate letters to members of the United States Congress. Journal of Forensic Sciences, 36(5), 1445–1468. doi:10.1520/JFS13165J

- Endler, N., & Parker, J. (1994). Assessment of multidimensional coping: Task, emotion, and avoidance strategies. Psychological Assessment, 6(1), 50–60. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.6.1.50

- Endler, N., Speer, R., Johnson, J., & Flett, G. (2000). Controllability, coping, efficacy, and distress. European Journal of Personality, 14(3), 245–264. doi:10.1002/1099-0984(200005/06)14:3<245::AID-PER375>3.0.CO;2-G

- Every-Palmer, S., Barry-Walsh, J., & Pathé, M. (2015). Harassment, stalking, threats and attacks targeting New Zealand politicians: A mental health issue. The Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 49(7), 634–641. doi:10.1177/0004867415583700

- Exel, V, J., & de Graaf, G. (2005). Q methodology: A sneak preview. Retrieved from www.qmethodology.net

- Figee, E., Eigeman, J., & Hilterman, F. (2008). Local government in the Netherlands. Den Haag, The Netherlands: Vereniging van Nederlandse Gemeenten.

- Folkman, S., Lazarus, R., Dunkel-Schetter, C., DeLongis, A., & Gruen, R. (1986). Dynamics of a stressful encounter: Cognitive appraisal, coping, and encounter outcomes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 50(5), 992–1003. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.50.5.992

- Folkman, S., & Moskowitz, J. (2004). Coping: Pitfalls and promise. Annual Review of Psychology, 55(1), 745–747. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141456

- Folkman, S., & Lazarus, R. (1985). If it changes it must be a process: Study of emotion and coping during three stages of a college examination. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 48(1), 150–179. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.48.1.150

- Folkman, S., & Lazarus, R. (1988). Manual for the ways of coping questionnaire. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

- Hoffmann, J., Meloy, J. R., & Sheridan, L. (2013). Contemporary research on stalking, threatening, and attacking public figures. In J. R. Meloy & J. Hoffmann (Eds.), International Handbook of Threat Assessment (pp. 160–177). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Huberts, L. W. J. C. (1988). De politieke invloed van protest en pressie. Besluitvormingsprocessen over rijkswegen. Leiden: DSWO Press.

- Huberts, L. (2014). The integrity of governance. What it is, what we know, what is done, and where to go. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

- James, D., Farnham, F., & Wilson, S. (2013). The fixated threat assessment centre. In J. R. Meloy & J. Hoffmann (Eds.), International handbook of threat assessment (pp. 229–320) New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Lazarus, R., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company.

- Marijnissen, D. (2019). Bedreigde wethouders. Een onderzoek naar de aard en invloed van bedreigingen tegen lokale politici. The Hague, The Netherlands: Boom Criminologie.

- Matthews, G., & Campbell, S. E. (1998). Task-induced stress and individual differences in coping. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting, 42(11), 821–825. doi:10.1177/154193129804201111

- Mayntz, R. (1993a). Governing failure and the problem of governability: Some comments on a theoretical paradigm. In J. Kooiman (Ed.), Modern governance (pp. 9–20). London, UK: Sage.

- Mayntz, R. (1993b). Modernization and the logic of interorganizational networks. In J. Child, M. Crozier, & R. Mayntz (Eds.), Societal change between markets and organization (pp. 3–18). Aldershot, UK: Avebury.

- Meloy, J. R., James, D. V., Farnham, F. R., Mullen, P. E., Pathé, M., Darnley, B., & Preston, L. (2004). A research review of public figure threaths, approaches, attacks, and assassinations in the United States. Journal of Forensic Sciences, 49(5), 1086–1093. doi:10.1520/JFS2004102

- Millet, P. (2005). Locus of control and its relation to working life: Studies from the fields of vocational rehabilitation and small firms in Sweden (Ph.D. thesis). Luleå University of Technology, Luleå, Sweden.

- Mullen, P., Pathé, M., & Purcell, R. (2009). Stalkers and their victims (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Cambridge Press.

- Nelen, H., & Kolthoff, E. (2017). Schaduwen over de rechtshandhaving. Den Haag, The Netherlands: Boom Criminologie.

- Park, C., Folkman, S., & Bostrom, A. (2001). Appraisals of controllability and coping in caregivers and HIV + men: Testing the goodness-of-fit hypothesis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 69(3), 481–488. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.69.3.481

- Pathé, M., Phillips, J., Perdacher, E., & Heffernan, E. (2014). The harassment of queensland members of parliament: A mental health concern. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 21(4), 577–584. doi:10.1080/13218719.2013.858388

- Reussing, R. (1996). Politiek-ambtelijke betrekkingen en het beginsel van de machtenscheiding. Twente, The Netherlands: Universiteit Twente.

- Rottenstreich, Y., & Hsee, C. (2001). Money, kisses, and electric shocks: On the affective psychology of risk. Psychological Science, 12(3), 185–190. doi:10.1111/1467-9280.00334

- Schmolck, P. (2002). PQ method. Retrieved from http://schmolck.org/qmethod/pqmanual.htm

- Skinner, E., Edge, K., Altman, J., & Sherwood, H. (2003). Searching for the structure of coping: A review and critique of category systems for classifying ways of coping. Psychological Bulletin, 129(2), 216–269. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.129.2.216

- Spirito, A., Stark, L., & Williams, C. (1988). Development of a brief coping checklist for use with pediatric populations. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 13(4), 555–574. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/13.4.555

- Stenner, P. H., Cooper, D., & Skevington, S. M. (2003). Putting the Q into quality of life; the identification of subjective constructions of health-related quality of life using Q methodology. Social Science & Medicine, 57(11), 2161–2172. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00070-4

- Stephenson, W. (1953). The study of behavior: Q-technique and its methodology. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Strentz, T., & Auerbach, S. (1988). Adjustment to the stress of stimulated captivity: Effects of emotion-focused versus problem-focused preparation on hostages differing in locus of control. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 55(4), 652–660. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.55.4.652

- Terry, D., & Hynes, G. (1998). Adjustment to a low control situation: Re examining the role of coping responses. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(4), 1078–1092. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.74.4.1078

- Tummers, L., Bekkers, V., Vink, E., & Musheno, M. (2015). Coping during public service delivery: A conceptualization and systematic review of the literature. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 25(4), 1099–1126. doi:10.1093/jopart/muu056

- Van Lieshout, M. (2018). Woningen van burgemeesters voortaan preventief op veiligheid gecontroleerd. Retrieved from https://www.volkskrant.nl/nieuws-achtergrond/woningen-van-burgemeesters-voortaan-preventief-op-veiligheid-gecontroleerd∼bb10a140/?referer=https%3A%2F%2Fduckduckgo.com%2F

- Vulperhorst, L. (Ed.). (2010). Praktische dromers. Over het vak van wethouder. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Van Gennep.

- Watts, S., & Stenner, P. (2012). Doing methodological research. Theory, method and interpretation. London, UK: Sage Publications.