Abstract

Politicians and public administrators have long played both prominent and supporting roles in works of fiction. The field of public administration has a tradition of using fictionalized depictions of administrative processes to understand better the relationship between theory and practice. Portrayals of public servants and government action in video games remain an understudied area, leaving gaps in our understanding related to digital media and bureaucratic characterization. Using Squire’s framework of understanding video games as a designed experience, this study examines the elements of administrative ethics and ethical decision making within the video game Papers, Please. Future research will most certainly be required to connect characterization of public service in digital media to public perception and pedagogy of administrative functions. This research aims to catalyze exploration into this concept through illustrated applicability and salience.

Public administrators and government officials have long played meaningful roles in popular culture. From novels to plays and from film to television, the public and private lives of public administrators have been the subject of both comedy and drama (Norman & Kelso, Citation2012; Stout, Citation2011) and have provided meaningful insights into government and its administration (Goodsell & Murray, Citation1995a). Literature and other art forms, such as plays, film, and television, provide public administration scholars and educators the opportunity, among other things, to explore the personal and professional challenges surrounding ethical decision making (Kroll, Citation1965; Marini, Citation1992; Waldo, Citation1956). Recent television sitcoms, such as NBC’s Parks and Recreation, introduce public administrators as central characters within shows and illustrate the complexities of public service to audiences. Politics and administrative action have proven fertile ground for authors and artists seeking to glean insights into the individual and societal challenges of government and its administration (Goodsell & Murray, Citation1995a). Although the majority of such works of art are developed for entertainment, the underlying contexts are readily evident and serve as a source of inspiration for exploring how popular culture integrates public service into larger themes. More importantly, such media provide an entertaining yet salient platform for examining ethical dilemmas within public service (Bharath, Citation2019; Borry, Citation2018a; Borry, Citation2018b; Dubnick, Citation2000; Jurkiewicz & Giacalone, Citation2000).

The characterization of public service within popular culture, most prominently through television and film, has provided a platform for blending entertainment into both theory and practice within the field of public administration. Investigations into how public servants have been portrayed in film suggest that such depictions often both reflect and reinforce negative stereotypes of government and government administration (Pautz, Citation2018; Pautz & Roselle, Citation2016). This is significant in that works of fiction not only impact societal views of public administration but, perhaps more importantly, also can influence the implementation of policy and professional conduct by public servants (McCurdy, Citation1995, p. 499). This is not to say that public administrators cannot and are not portrayed as protagonists in works of fiction (Goodsell & Murray, Citation1995b). Regardless of how practitioners are portrayed, artistic explorations into the field are valuable to both scholars and students in that they provide insights into how those outside the discipline view the administrative process (Waldo, Citation1956, p. 81). One form of media in particular, video games, represents an overlooked medium in examining the portrayal of government in general and specifically public administrators in popular culture.

Video games have come to have a profound sociological and economic influence on modern culture. Revenue for video game software and hardware eclipsed $43 billion globally in 2018 alone, surpassing projected global box office revenue and streaming service revenue (Shieber, Citation2019). Furthermore, digital content distribution platforms have fostered greater access to popular video games, creating an interconnected digital community across the world. Despite the impressive growth of the video game industry over the past two decades, only a handful of academic disciplines have taken genuine scholarly interest in how this budding industry shapes modern society.

The landscape of video games has evolved over the past several decades, a wealth of untapped potential that has developed through which relationships can be explored among video games, public service, and societal trends. Many video games are developed primarily for entertainment purposes; however, an increasing number of video games examining broader aspects of modern society are emerging, including games examining the realm of public service, administrative discretion, and ethical dilemmas. Perhaps no current video game explores the ethical and moral complexities of bureaucratic paradigms with greater depth and creativity than Papers, Please (Citation2013), the award-winning game created by independent video game developer Lucas Pope.

Exploring how video games tap into dimensions of public service theory and practice requires the application of an appropriate framework. Squire’s (Citation2006) model of video games as a designed experience, in which video game players participate and learn through action and context, provides such a framework. Examining video games as a designed experience rests upon three primary concepts: critical analysis of games as participation within ideological systems, learning as performance, and video games as designed experiences. Applying this framework to Papers, Please produces a critical analysis of how video games afford players an opportunity to participate in bureaucratic processes, experience administrative theory through simulation, and conceptualize ethical dilemmas of public service through gameplay.

The following analysis begins by illustrating existing literature concerning video games as viable learning and communications tools. Review of the relevant literature is followed by application of the designed experience framework to Papers, Please and identification of concepts and theories pertaining to administrative ethics contained within gameplay. The analysis then outlines approaches for applying existing frameworks toward further exploration of the relationship between video games and characterizations of public service. Suggestions for future research concepts conclude the study.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Video Games as Communications and Learning Tools

Although relatively nascent to many academic disciplines, the study of video games in both applied and theoretical contexts has expanded dramatically since the early 2000s. Video game research has resulted in scholarly inquiry into relationships bridging virtual settings and areas of civic engagement; governance; politics; community action; and economics across a variety of academic disciplines (Malaby & Burke, Citation2009, p. 324). The proliferation of studies examining the scope of influence exerted by video games can be attributed to the embracing of video games as both a cultural component and pedagogical tool as far back as the 1980s, with games such as The Oregon Trail (Citation1975), Where in the World is Carmen San Diego? (Citation1985), and Math Blaster! (Citation1984), providing an engaging dynamic of educational curriculum. Squire (Citation2008) notes that the acceptance of video games as a viable learning tool reflects the latent potential of video games as a powerful and altogether digital medium of learning experiences (p. 17). Educational use of video games such as Minecraft (Citation2009) has gained immense support in both scholarly and practical application globally since its release (Nebel, Schneider, & Rey, Citation2016).

The shift of video games from entertainment to educational tool for cognitive and intellectual development has spawned a growing field of scholarly research. As access to software and technology used to develop video games expanded, so, too, has scholarly interest in video games within various academic disciplines. Gros (Citation2007) highlights social science disciplines incorporating video games into research including literature; psychology; sociology; history; business; and education (p. 24).

Interest in games as learning and communications tools can be traced back to the 1950s, when private industry and business gaming promoted research into the potential impact of games on learning through board games and training exercises (Butler, Citation1988). Private sector interest in the potential of games continued well into the 1980s, when advanced technology in the field initiated a shift in examination of games into digital training and simulation experiences highlighted by publications such as Prensky’s (Citation2001) Digital Game Based Learning. Focus on computer games as educational and training tools increased exponentially during the 1980s and 1990s, largely due to research exploring the potential of computer games as educational and training aids such as Mind at Play and Mind and Media (Greenfield, Citation1996; Loftus & Loftus, Citation1983).

The progression of research on simulation games has generated additional questions regarding the impact of video games. Simulation video games are designed to provide players with experiences of fictional characters, thus warranting investigation into whether simulated experiences that players have with characters manifest into changes in personal affective and cognitive processors, as outlined by Oatley’s (Citation1995) theory of identification. Klimmt, Hefner, and Vorderer (Citation2009) argue that video game players may identify closely with specific characters or roles occupied within the context of the video game, due to the interactive nature of video games, by allowing players to take a personal-individual perspective into the video game world. This element highlights a primary distinction of video games from traditional forms of media, in that video games provide instantaneous identification feedback to players.

From a social psychological perspective, identification with video game characters changing a player’s self-perception can be construed as an activation of cognitive associations between character-related concepts and the player’s self (Klimmt, Hefner, Vorderer, Roth, & Blake, Citation2010, p. 326). To test this hypothesis, Klimmt et al. utilized an implicit measurement tool, the Implicit Association Test (IAT), capable of detecting cognitive associations between differing concepts (Greenwald, McGhee, & Schwartz, Citation1998). Results lent support to the theory suggesting identification as a cognitive process involved in player responses to video games. Further, games containing narratives in which players are assigned or select control of specific characters may facilitate a sense of vicarious self-perception, effectively altering players’ self-experience during game play (Goldstein & Cialdini, Citation2007; Klimmt et al., Citation2010).

Video Games as Simulated Experiences

In contrast to traditional video games, which suspend or augment rules of reality to construct the rules of a video game, simulations attempt to replicate systems and environments which are consistent with reality (Heinich, Molenda, Russell, & Smaldino, Citation1996). Simulation video games provide for a more closely analogous context for players to immerse themselves into fabricated or fictionalized environments. This dynamic allows players an opportunity to embody effectively game characters they control, fostering enhanced self-experience during game play. It is important to note, however, that not all video games as simulations exist within a single dimension.

Differentiating simulation systems is critical to the design and effectiveness of simulations, as Thiagarajan (Citation1998) outlines two primary simulation constructs: high fidelity simulations and low fidelity simulations. High-fidelity simulations are designed to replicate real-life conditions and environments as closely as possible, thus allowing for a heightened sense of user immersion within the simulation. These simulations are frequently utilized in situations where participating in the actual activity may be physically harmful or cost prohibitive. Prominent examples of high-fidelity simulations include those pertaining to aviation, law enforcement, and military exercises where physical harm is mitigated by replicating life-like simulated environments.

Unlike high-fidelity simulations, low-fidelity simulations find the greatest application when developing an understanding of concepts by allowing users to interact with complex systems while reducing or eliminating extraneous variables (Thiagarajan & Thiagarajan, Citation1999). As Papers, Please endows players with bureaucratic authority in the context of immigration, the game would be categorized as a low-fidelity simulation, since players are provided a fictional environment and the experience of an entry-level administrator. Although categorized as a low-fidelity simulation, players of Papers, Please are introduced to observable administrative practices and theories relevant to public service. Even within a simulated setting, by enabling players to interact with a model of a complex system, simulations place users in a unique position to understand a system’s dynamics (Squire, Citation2005, p. 6).

Low-fidelity simulations, such as in Papers, Please, allow players to explore decision-making processes and to engage in a world with consequences without the high stakes of real-world consequences. One weakness of low-fidelity simulations is that they often do not have the power to evoke the emotions and feelings of those who actually face simulated experiences in real life (Donald, Citation2019). Regardless of their ability to evoke a specific emotion within those who play them, video games are designed to produce certain action. As the goal of a particular video game is to win, or at the very least continue playing, it is not surprising that players tend to adapt their behavior to receive rewards offered based on the structure of the game. Helping students recognize that a game can influence one’s actions provides an opportunity to reflect on the reason why one action was taken over another and how the structure of a particular game influences which actions are considered right or wrong within a given context (Consalvo, Busch, & Jong, Citation2019). Such experiences allow students to explore how structures influence individual action both in video games and in real life and to grapple with if or when it is appropriate to bend or break a rule either for one’s own benefit or for the benefit of others (Fennewald & Phelps, Citation2019).

The use of simulations aiding in the self-identity of users represents a key component assisting in cognitive development. As noted, simulations are often used to immerse users within an environment to facilitate development of self-identity. However, reflecting upon the impact that simulations have on real-life environments and contexts requires users developing characterizations or conceptualizations of how the simulation affects them beyond the notion of self-identification. Marshall (Citation2012) differentiates between the sociopolitical and psychopolitical dimensions of how media shapes opinions and beliefs concerning one’s relationship with the world by arguing the sociopolitical dimension of a film relates to a film’s ability to connect to large societal trends or culture while the psychopolitical dimension is the relationship between the film and a distinct viewer (p. 134). The application of a theoretical framework for examining how video games and simulations impact users’ perceptions of public service requires utilizing all three concepts discussed to assist in identifying changes in self, relationships, and environments among players and bureaucratic institutions.

WHAT PAPERS, PLEASE CAN TELL US ABOUT ADMINISTRATIVE ETHICS

Created by independent video game developer Lucas Pope, Papers, Please was released in 2013 to critical acclaim for its originality, design, and immersion within a bureaucratic context. Praised by reviewers, Papers, Please garnered numerous video game industry awards for its originality and immersive gameplay, including the Seumas McNally Grade Prize for Best Independent Game at the 16th Annual Independent Games Festival and Most Innovative and Best Game Play Awards at the Games for Change Festival (LeJacq, Citation2014; Staff, Citation2014).

Billed as a dystopian document thriller, Papers, Please places players in the role of an immigration agent of the fictional Eastern Bloc country of Arstotska in the winter of 1982. The game begins with an explanation that following diplomatic agreements between Arstorska and neighboring countries, restrictions related to immigration and travel policies have been relaxed. This change in government policy is fortuitous for the protagonist as unemployment in Arstotska is high and the new player is told that he or she has been chosen, through a lottery system, for employment as a border agent with the Ministry of Admission. The newspaper headlines of The Truth of Arstotska report that the border checkpoint to which the new player is assigned has not been open for several years and question whether the Ministry of Admission can keep its citizens safe from the threats of a weak domestic border. New players are given the opportunity to rent an apartment for their family and are compensated by the number of individuals processed in a given day. Players are not penalized for the first two administrative mistakes they make; however, after the third error in judgment, a player’s take-home pay is negatively impacted. This becomes an important incentive in that a player’s rent must be paid at the end of each day and if there is money remaining, the players can purchase food, medicine, or heat for the apartment. If a player fails to earn enough money in a given day to pay rent, gameplay ends and he or she is not only fired but is sent to prison until debts are paid.

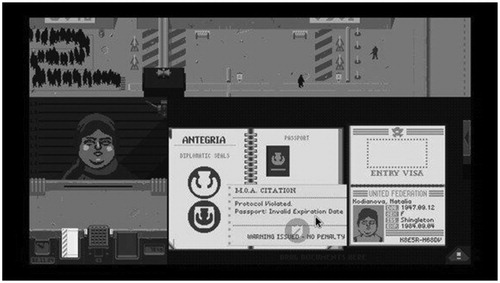

Gameplay requires players to screen Non-Player Characters (NPC’s) for admittance into Arstotska (see ). Despite this seemingly menial task, Papers, Please presents players with many ethical dilemmas routinely faced by public servants. It is within this lens that Papers, Please shines as an illustrative example of the characterization of bureaucratic functions within video games and digital entertainment.

Figure 1. Players must determine if NPC’s have relevant paperwork for admission into Arstotzka. Admission requests are either approved or denied by the player. Screen Capture from Papers, Please. © Copyright 3909 LLC. Used with permission.

Beyond the association that Papers, Please shares with elements of administrative ethics within its gameplay, the relative ease of gameplay mechanics in Papers, Please fosters accessibility to the game itself. Standing in contrast to graphically intense contemporary video games, Papers, Please relies on simplistic graphics capable of operation on most modern computers alongside common peripherals, such as mouse and keyboard, to allow players of all ages and experience to engage in gameplay. The straight-forward gameplay mechanics recall early iterations of “Point & Click” computer games of the 1980s, by relying more on the cognitive abilities of players over hand-and-eye coordination skills necessary for modern, fast-paced video games epitomized by the First-Person Shooter (FPS), Real-Time Strategy (RTS), and Massive Online Battle Arena (MOBA) genres.

Games as Participation in Ideological Worlds: Conditions of Administrative Evil

Examining the game through Squire’s (Citation2006) framework, the ideological context of the game is readily identifiable: players assume, through simulation, the nameless, faceless protagonist bureaucrat. Following recent relaxation of immigration policies by the government of Arstotska, players are tasked with enforcing the administrative rules and regulations implemented by the government concerning the admittance of citizens into Arstotska.

Although the country of Arstotska is fictional, the lack of personal identification of the protagonist within the game serves a dual purpose: to provide a connection between the player and the protagonist as an immersive self-identification tool, and metaphorically linking administrators as unidentifiable components of a rigid, mechanistic bureaucratic complex. In this lens, the game presents players with an administrative construct similar to the monolithic structure outlined by Weber (Citation1946). Denying the protagonist personal identification not only constructs an avenue for players to immerse themselves within the administrative role, but also further reinforces the notion of rigidity surrounding the contentious (and often controversial) administrative functions pertaining to immigration. Assuming the role of an autonomous bureaucrat provides players with an incentive to dehumanize effectively an otherwise emotionally and psychologically intense function: deciding the fate of others within the context of an intense and deeply personal action such as immigration.

Strict adherence to the rules and policies of administrative systems that rest at the heart of the experience of Papers, Please extends beyond archetypes of bureaucracy into the inherent nature of classical administration. The growing emphasis on technical administrative expertise through rational action exacerbates the decay of moral consideration in administrative decision making (Balfour & Adams, Citation2004, p. 35). Devoid of introspective considerations within official decision-making processes, public administrators are effectively coerced to act upon the principles outlined within orders and policies rather than upon individual moral values (Thompson, Citation1985, p. 556). Such conditions eschew individualized problem solving, thus devaluing and discouraging emotional considerations and promoting a culture of bureaucratic impersonality (Martin, Knopoff, & Beckman, Citation1998).

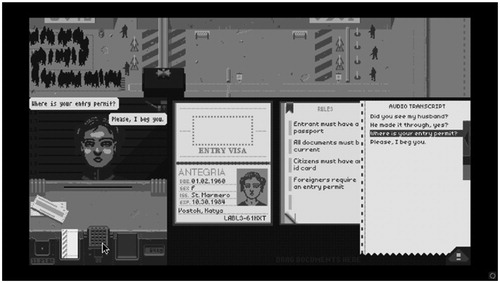

Left unaddressed, rigid bureaucratic systems actively repressing moral decision making may foster oppressive conditions conducive to administrative evil. Synthesizing the sociopolitical dynamics of Papers, Please, Kelly (Citation2018) powerfully outlines the conditions of administrative evil underlying the game’s setting which strongly propound elements of nationalism and fascism (p. 473; see ).

Figure 2. Player receives Ministry of Admission citation for admitting a passport holder with an expired passport. As the first infraction, the citation is a warning rather than a penalty; however, the player is not compensated for processing this individual’s entry into Arstotzka. Screen Capture from Papers, Please. © Copyright 3909 LLC. Used with permission.

Taken at face value, the conditions present within Papers, Please are suggestive of nothing more than a fictionalized environment conducive to administrative evil. However, the institutionalization of policies directed at selective populations can be an important means of understanding the impact of such policies and administrative action on these populations and those who administer them.

Knowledge as Performance: Bureaucratic Discretion and Ethics of Neutrality

A core dynamic of administrative rulemaking involves restraining bureaucratic discretion in individual cases (West, Citation2005, p. 655). This conceptualization of administrative rulemaking would seem to place it in a category of bureaucratic restraint, with the influence of administrative rulemaking as a constraint to bureaucratic notions of ethics and discretion illustrated throughout the game.

Progression in Papers, Please requires players to increase their performance through each sequential period of gameplay. Beginning with simplistic guidelines within the “Rule Book” provided to players, gameplay becomes increasingly challenging as players advance through their workdays while accounting for additional administrative rules. For example, entering the first work day, players are provided simple instructions within the “Rule Book” for admitting immigration applicants into Arstotska. Initial rules provided to players indicate permission to enter the country only to those who hold valid visas previously issued by Arstotska. However, with each passing work day, players are confronted with more challenging Rule Book guidelines for permitting entry to Arstotska, such as valid visas from specific neighboring countries, work permits, or travel documents. The layering of rules within the Rule Book add a degree of difficulty, by forcing players to process rapidly admission requests through rigid bureaucratic rules and time constraints, thus limiting the possibility for administrative discretion and conflicts arising from ethical decision making (see ).

Figure 3. As play continues, the Ministry of Admission adds increasing rules and restrictions on those seeing entrance into Arstozka, prompting player evaluation. Instances of administrative discretion afford players opportunities to engage in ethical decision-making as a form of dissent against established rules. In the image above, players must decide whether to grant admission into Arstotzka without proper documentation to the spouse of an NPC previously granted admission into the country. Denying admission, in this instance, results in conformity to established rules; however, granting admission results in either a written warning or a deduction of pay as a violation of established rules. Screen Capture from Papers, Please. © Copyright 3909 LLC. Used with permission.

Although players are provided the opportunity to exert administrative discretion in the admittance of immigration applicants, such as when the documents provided by immigrants do not contain matching information, allowing entrance to immigrants who do not have accurate or current documentation is met with punitive consequences in the form of written warnings or deduction of credits. This punitive action teaches players adherence to established bureaucratic rules and norms, thus deterring players from fully engaging in discretionary actions. Furthermore, deterrence from administrative discretion strips away the core foundation of administrative discretion as a political power wielded by administrators in the interests of a citizenry outlined by scholars, such as Mosher (Citation1982) and Rourke (Citation1984).

The implementation of administrative rules, by effectively limiting discretion afforded to players of Papers, Please, reinforces the concept of bureaucracy as a rigid, mechanical process. The strict guidelines provided to players, therefore, may be viewed as a method for players to learn the generalized structure of bureaucracy and administrative action through adherence to perpetually increasing administrative rules designed to limit administrative discretion. Despite this learned perception of bureaucracy as a cold, monolithic institution, players are afforded opportunities to wield the administrative power of discretion in various instances, emphasizing the oft-overlooked humanistic component of public service. Ironically, administrative discretion is not only a core component of gameplay, but also represents the key to finishing the game itself.

Games as Designed Experience: Organizational Justice and Administrative Dissent

A pivotal component requisite for completing Papers, Please involves active subversion of established administrative policy and procedure to thwart the continuing oppression of administrative discretion. Connecting the completion of the game to administrative dissent is a striking illustration of O’Leary’s (Citation2010) concept of “guerrilla government” in action, wherein acts of dissent are carried out by those dissatisfied with the action of public organizations or programs who have not disclosed publicly their actions in this respect for strategic purposes (p. 8). Whereas acts of organizational dissent are witnessed in both the public and the private spheres, Reed (Citation2014) notes that dynamics of dissent correlate with aspects of national security in the public sector (p. 6). This position, conjoined with immigration policies framed within national security contexts, provides palatable relation to retaining administrative power in the face of political disruption (O’Leary, Citation2017).

At its core organizational dissent reflects expressions of disagreement related to organizational actions, whether such actions reflect organizational practices or established policies (Kassing, Citation1997). In broadening this position, Kassing (Citation1997, Citation1998) outlines three variants of dissent common within organizations: articulated dissent, latent dissent, and displaced dissent. Although only one variant of dissent proposed by Kassing involves communicating dissatisfaction or concerns with organizational members able to affect change, all three involve relating or conveying along communication networks to individuals internal or external to the organization in question. Therefore, the concept of organizational dissent as universally applicable stands in stark contrast to the clandestine actions of guerrilla government.

Intertwined with elements of organizational dissent and guerrilla government in Papers, Please, organizational justice constructs remain prevalent throughout gameplay. As players are charged with reviewing and processing immigration documents as an element of gameplay, three core components of organizations justice emerge: namely, distributive justice, procedural justice, and interactional justice. Instances of distributive justice, described by Homans (Citation1961) as individual perceptions of fairness in outcomes, in gameplay are evidenced by players through their discretionary actions, which either violate or adhere to established policies, resulting in deduction or acquisition of credits. However, it is the enactment of procedural and interactional justice constructs that results in administrative dissent and guerrilla government tactics.

Procedural justice represents an axiom of gameplay in Papers, Please, as well as a critical link to the concepts of administrative discretion and administrative ethics. Relating to individual perceptions of fairness of procedural components of decision making, individual determinants of fairness involve judgment concerning the consistency of application; prevailing ethical standards; avoidance of bias; accuracy of information; correctability; and representativeness (Leventhal, Citation1980).

DISCUSSION

This study is not intended to be an exhaustive evaluation of the catalog of video games relevant to public administration theory and practice, but rather to serve as the opening salvo of a more expansive conversation. Video games have become an important part of modern American culture. As such, public administration scholars should consider them as an important medium to understand the ways in which government and public administration are depicted in popular culture. The use of Papers, Please as an illustrative case study into the potential insights that video games might offer into public administration praxis has its limits. Video games, such as Papers, Please, often do not have the broad appeal of a major motion picture or network television production. Many video games, such as Papers, Please, are developed independently of major gaming developers, which relegates many of these games to obscurity even within the gaming community. Consequently, public administration scholars and students may dismiss them as irrelevant or inconsequential. This would be a mistake; as video gaming becomes prevalent, it is important to investigate the representation of society.

A dynamic of video games warranting genuine scholarship and attention centers not only on the value of video games as entertainment, but also as a potent learning tool. The increasing development of serious games, or games which seek to impart value through experiential learning, provides such an avenue to develop critical skills through an entertaining experience. Coalescence of skills development and analysis of ethical problems represents a key step toward the cultivation of moral judgment (Staines, Formosa, & Ryan, Citation2019, p. 414). It is within this dimension that the potential of video games as a means to examine ethical and moral decision making, including within the realm of public service as well as how best to implement these emerging learning tools, is realized.

The concept of using video games as a medium for exploring ethical and moral decision making has steadily grown over the past several years. Much of this growth in literature can be attributed to the proliferation of accessibility to video games, along with increasing awareness of the cultural impact of video games in society. Importantly, scholars continue to position ethically notable video games as educational tools that can promote moral decision making and social values (Belman & Flanagan, Citation2010; Schrier, Citation2015; Staines, Citation2010). Exploration of the ethical and moral dilemmas encountered by players in video games, such as the moral and ethical decisions faced by players in the Mass Effect (Mass Effect Series, Citation2008–2017) video game series and Fallout 3 (Fallout 3, Citation2009), has resulted in the examination of how video games shapes decision-making events for so-called wicked problems (Bosman, Citation2019).

Given the strict authoritarian context underlying gameplay as rule-following or rule-governed behavior, through which a player’s deportment emerges, previous scholarship has centered on ethical and moral dilemmas faced by players of Papers, Please. For example, Formosa, Ryan, and Staines (Citation2016) closely examine and expand upon the ethical and moral themes arising in Papers, Please by focusing on four ethical conditions prominent throughout the game: dehumanization, privacy, fairness, and loyalty. As thorough as their exploration of these ethical and moral themes may be, the use of legitimate authority as an agent of the State (by which players use the protagonist as a proxy) receives little discourse. It is within this context that the ethical and moral dilemmas faced by players in Papers, Please underscores the emotional and ethical considerations latent in public service.

This exploration of Papers, Please provides a lens to view how public service, administrative discretion, and administrative ethics are characterized in digital media. It should be noted, however, that this study contains limitations in terms of scope and salience, the most obvious of which concerns subjectivity. Similar to scholarly analysis of abstract concepts, such as art or music, latent subjectivity exists due to individual interpretive approaches harnessed when examining mediums of personal expression. In the case of this analysis of Papers, Please, the lens of public administration and administrative ethics was considered throughout the course of more than 20 hours of gameplay to foster the underlying context of public service scholarship. However, replicating the same experience has generated scholarship through the lens of moral learning, critical skills development, and application of player-agency constructs (Johnson, Citation2015; Kelly, Citation2018; Romero, Usart, & Ott, Citation2015; Schrier, Citation2017).

Future Research and Conclusion

As technology and video games have evolved, so, too, have societal perceptions of video games and video game players. Emerging genres of video games and increasing awareness of video game culture contest preconceived notions of the value of video games and the characteristics of video game players. These shifts, combined with greater access to high speed telecommunications, have promoted inclusiveness to video games across geographic and demographic strata. Kowert, Festl, and Quandt (Citation2014) illustrate this shift, noting a dramatic rise in video game players in their twenties and thirties, an increasing number of women playing video games, and dispelling the trope of video game players as psychologically and socially disengaged (p. 144). In many ways, the stereotype of the typical video game player as an introverted, disordered young male is rapidly eroding (Griffiths, Davies, & Chappell, Citation2003, p. 86).

On the surface, the mere concept of examining how public service is characterized in video games may seem bizarre to conservative observers, considering the wealth of literature focusing on established areas of scholarly interest in public administration. Roundly viewed as a subsect of popular culture and media, video games represent a fraction of consumable media. In the broader context of public administration scholarship, one would be forgiven for quickly dismissing the connection between depictions of public service in video games and public administration scholarship as irrelevant to the discipline at large. However, hastily dismissing this concept deprives scholars of the opportunity to examine closely another facet of popular culture that is substantially shaping opinions of public service.

Similar to other contemporary disciplines, the study of games and video games within the social sciences continues to experience proverbial growing pains. The rapidly expanding base of literature exploring the scholarly value of video games does not reflect established or universally accepted theoretical and methodological approaches employed by various disciplines. Yet this formative phase of video game scholarship permits flexibility in application toward a variety of fields of interest. A key advantage of such flexibility relates to the formation and positioning of research questions based on the objectification of games, such as storytelling mechanisms; communications tools; works of art; simulation of environment; or recreation of experiences (Corliss, Citation2011, p. 3).

Advantageously, determining whether characterization of public service in video games shapes perceptions of bureaucratic functions could be achieved through a variety of methods. The preliminary step to achieve this goal is the identification of video games and digital entertainment that incorporate the characterization of public service into user experience. Doing so requires identifying and locating games containing administrative concepts and feature central characters that represent key relationships within the game. Importantly, selecting video games for scholarship will necessitate delineating public service classifications to optimize their relative value for scholarly study.

Analytically, the evolving methodological applications harnessed by existing literature exploring dimensions of video games in adjacent scholarly disciplines provide insight into how such studies may be approached through qualitative methods. Examples of applying qualitative methods include the combination of traditional content analysis techniques with emerging approaches, such as neural networks and advanced machine-learning applications. Such approaches have been applied to analysis of content within consumer reviews to decipher underlying meanings and perceptions of commenters (Sharma et al., Citation2016; Zhang et al., Citation2015), suggesting application of techniques analyzing reviews by players of video games prominently featuring public servants as central characters. The results of such future studies of self-reporting could potentially unlock valuable findings concerning the role that video games featuring bureaucratic characters play in the development of player perceptions of public service.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Lucas Pope, developer of Papers, Please, for his contributions and for his approved use of in-game images for this scholarship.

REFERENCES

- Balfour, D. L., & Adams, G. B. (2004). Unmasking administrative evil. New York, NY: M.E. Sharpe.

- Belman, J., & Flanagan, M. (2010). Designing games to foster empathy. International Journal of Cognitive Technology, 15(1), 5–15.

- Bharath, D. M. N. (2019). Ethical decision making and The Avengers: Lessons from the screen to the classroom. Public Integrity, 1–4. doi:10.1080/10999922.2019.1600352

- Borry, E. L. (2018a). Linking theory to television: Public administration in Parks and Recreation. Journal of Public Affairs Education, 24(2), 234–254. doi:10.1080/15236803.2018.1446881

- Borry, E. L. (2018b). Teaching public ethics with TV: Parks and Recreation as a source of case studies. Public Integrity, 20(3), 300–315. doi:10.1080/10999922.2017.1371998

- Bosman, F. G. (2019). There is no solution! “Wicked Problems” in digital games. Games and Culture, 14(5), 543–559. doi:10.1177/1555412017716603

- Butler, T. (1988). Games and simulations: Creative education alternatives. TechTrends, 33(4), 20–24. doi:10.1007/BF02771190

- Consalvo, M., Busch, T., & Jong, C. (2019). Playing a better me: How players rehearse their ethos via moral choices. Games and Culture, 14(3), 216–235. doi:10.1177/1555412016677449

- Corliss, J. (2011). The social science study of video games. Games and Culture, 6(1), 3–16. doi:10.1177/1555412010377323

- Donald, I. (2019). Just war? War games, war crimes, and game design. Games and Culture, 14(4), 367–386. doi:10.1177/1555412017720359

- Dubnick, M. (2000). Movies and morals: Energizing ethical thinking among professionals. Journal of Public Affairs Education, 6(3), 147–159. doi:10.2307/40215484

- Fallout 3 [Computer software]. (2009). Rockville, MD: Bethesda Softworks.

- Fennewald, T., & Phelps, D. (2019). Analyzing moral deliberation during gameplay: Moral foundations theory as an analytic resource. Games and Culture, 14(7–8), 917–936. doi:10.1177/1555412017745231

- Formosa, P., Ryan, M., & Staines, D. (2016). Papers, Please and the systemic approach to engaging in ethical expertise in video games. Ethics and Information Technology, 18(2), 211–225. doi:10.1007/s10676-016-9407-z

- Goldstein, N. J., & Cialdini, R. B. (2007). The spyglass self: A model of vicarious self-perception. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(3), 402–417. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.92.3.402

- Goodsell, C. T., & Murray, N. (Eds.). (1995a). Public administration illuminated and inspired by the arts. Westport, CT: Praeger.

- Goodsell, C. T., & Murray, N. (1995b). Prologue: Building new bridges. In C. T. Goodsell & N. Murray (Eds.), Public administration illuminated and inspired by the arts (pp. 3–24). Westport, CT: Praeger.

- Greenfield, P. M. (1996). Video games as cultural artifacts. In P. M. Greenfield & R. R. Cocking (Eds.), Interacting with video (pp. 35–46). Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

- Greenwald, A. G., McGhee, D. E., & Schwartz, J. L. K. (1998). Measuring individual differences in implicit cognition: The implicit association test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(6), 1464–1480. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.74.6.1464

- Griffiths, M. D., Davies, M. N. O., & Chappell, D. (2003). Breaking the stereotype: The case of online gaming. CyberPsychology & Behavior: The Impact of the Internet, Multimedia and Virtual Reality on Behavior and Society, 6(1), 81–91. doi:10.1089/109493103321167992

- Gros, B. (2007). Digital games in education: The design of games-based learning environments. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 40(1), 23–38. doi:10.1080/15391523.2007.10782494

- Heinich, R., Molenda, M., Russell, J. D., & Smaldino, S. E. (1996). Instructional media and technologies for learning (5th ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Homans, G. C. (1961). Social behavior. New York, NY: Harcourt, Brace & World.

- Johnson, D. (2015). Animated frustration or the ambivalence of player agency. Games and Culture, 10(6), 593–612. doi:10.1177/1555412014567229

- Jurkiewicz, C. L., & Giacalone, R. A. (2000). Through the lens clearly: Using films to demonstrate ethical decision-making in the public service. Journal of Public Affairs Education, 6(4), 257–265. doi:10.2307/40215497

- Kassing, J. W. (1997). Articulating, antagonizing, and displacing: A model of employee dissent. Communication Studies, 48(4), 311–332. doi:10.1080/10510979709368510

- Kassing, J. W. (1998). Development and validation of the Organizational Dissent Scale. Management Communication Quarterly, 12(2), 183–229. doi:10.1177/0893318998122002

- Kelly, M. (2018). The game of politics: Examining the role of work, play, and subjectivity formation in Papers. Games and Culture, 13(5), 459–478. doi:10.1177/1555412015623897

- Klimmt, C., Hefner, D., & Vorderer, P. (2009). The video game experience as “true” identification: A theory of enjoyable alterations of players’ self-perceptions. Communication Theory, 19, 351–373.

- Klimmt, C., Hefner, D., Vorderer, P., Roth, C., & Blake, C. (2010). Identification with video game characters as automatic shift of self-perceptions. Media Psychology, 13(4), 323–338. doi:10.1080/15213269.2010.524911

- Kowert, R., Festl, R., & Quandt, T. (2014). Unpopular, overweight, and socially inept: Reconsidering the stereotype of online gamers. CyberPsychology, Behavior & Social Networking, 17(3), 141–146. doi:10.1089/cyber.2013.0118

- Kroll, M. (1965). Administrative fiction and credibility. Public Administration Review, 25(1), 80–84. doi:10.2307/974010

- LeJacq, Y. (2014, April 14). Papers, Please scored two big wins last night at the 2014 games for change festival’s award ceremony [Web log post]. Retrieved from http://kotaku.com/papers-please-scored-two-big-wins-last-night-at-the-20-1567107704.

- Leventhal, G. (1980). What should be done with equity theory? New approaches to the study of fairness in social relationships. In K. Gergen, M. Greenbers, & R. Willis (Eds.), Social exchange: Advances in theory and research (pp. 27–55). New York, NY: Plenum Press.

- Loftus, G., & Loftus, E. (1983). Mind at play: The psychology of video games. New York, NY: Basic Books.

- Malaby, T. M., & Burke, T. (2009). The short and happy life of interdisciplinarity in game studies. Games and Culture, 4(4), 323–330. doi:10.1177/1555412009343577

- Marini, F. (1992). Literature and public administration ethics. American Review of Public Administration, 22(2), 111–125. doi:10.1177/027507409202200203

- Marshall, G. (2012). Applying film to public administration. Administrative Theory & Praxis, 34(1), 133–142. doi:10.2753/ATP1084-1806340110

- Martin, J., Knopoff, K., & Beckman, C. (1998). An alternative to bureaucratic impersonality and emotional labor: Bounded emotionality at the body shop. Administrative Science Quarterly, 43(2), 429–469. doi:10.2307/2393858

- Mass Effect Series [Computer software]. (2008–2017). Austin, TX: BioWare Studios.

- Math Blaster! [Computer software]. (1984). Torrance, CA: Davidson & Associates.

- McCurdy, H. (1995). Fiction and imagination: How they affect public administration. Public Administration Review, 55(6), 499–506. doi:10.2307/3110340

- Minecraft [Computer software]. (2009). Stockholm, Sweden: Markus Persson.

- Mosher, F. C. (1982). Democracy and the public service (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Nebel, S., Schneider, S., & Rey, G. D. (2016). Mining learning and crafting scientific experiments: A literature review on the use of minecraft in education and research. Educational Technology & Society, 19(2), 355–366.

- Norman, K., & Kelso, A. W. (2012). Television as text: The public administration of parks & recreation. Administrative Theory & Praxis, 34(1), 143–146. doi:10.2753/ATP1084-1806340111

- Oatley, K. (1995). A taxonomy of the emotions of literary response and a theory of identification in fictional narrative. Poetics, 23(1–2), 53–74. doi:10.1016/0304-422X(94)P4296-S

- O’Leary, R. (2010). Guerrilla employees: Should managers nurture, tolerate, or terminate them? Public Administration Review, 70(1), 8–19. doi:10.1111/j.15406210.2009.02104.x

- O’Leary, R. (2017). The ethics of dissent: Can President Trump survive guerrilla government? Administrative Theory & Praxis, 39(1), 63–79. doi:10.1080/10841806.2017.1309803

- Papers, Please [Computer software]. (2013). Lucas Pope: Dukope.

- Pautz, M. C. (2018). Civil servants on the silver screen: Hollywood’s depiction of government and bureaucrats. New York, NY: Lexington Books

- Pautz, M. C., & Roselle, L. (2016). Are they ready for their close-up? Civil servants and their portrayal in contemporary American cinema. Public Voices, 11(1), 8–32. doi:10.22140/pv.98

- Prensky, M. (2001). Digital game based learning. New York, NY: McGraw Hill Press.

- Reed, G. (2014). Expressing loyal dissent: Moral considerations from literature on followership. Public Integrity, 17(1), 5–18. doi:10.2753/PIN1099-9922170101

- Romero, M., Usart, M., & Ott, M. (2015). Can serious games contribute to developing and sustaining 21st century skills? Games and Culture, 10(2), 148–177. doi:10.1177/1555412014548919

- Rourke, F. E. (1984). Bureaucracy, politics, and public policy (3rd ed.). Boston, MA: Little, Brown.

- Schrier, K. (2015). EPIC: A framework for using video games in ethics education. Journal of Moral Education, 44(4), 393–425. doi:10.1080/03057240.2015.1095168

- Schrier, K. (2017). Designing games for moral learning and knowledge building. Games and Culture, 1–38. doi:10.1177/1555412017711514

- Sharma, R. D., Tripathi, S., Sahu, S. K., Mittal, S., & Anand, A. (2016). Predicting online doctor ratings from user reviews using convolutional neural networks. International Journal of Machine Learning and Computing, 6(2), 149–154. doi:10.18178/ijmlc.2016.6.2.590

- Shieber, J. (2019, January 22). Video game revenue tops $43 billion in 2018, an 18% jump from 2017 [Online article]. Retrieved from https://techcrunch.com/2019/01/22/video-game-revenue-tops-43-billion-in-2018-an-18-jump-from-2017.

- Squire, K. (2005). Video games in education. Unpublished manuscript, Comparative Media Studies Department, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA.

- Squire, K. (2006). From content to context: Videogames as designed experience. Educational Researcher, 35(8), 19–29. doi:10.3102/0013189X035008019

- Squire, K. D. (2008). Video games and education: Designing learning systems for an interactive age. Educational Technology, 48(2), 17–26.

- Staff. (2014, March 19). Papers, Please takes the grand prize at 16th Annual IGF Awards [Web log post]. Retrieved from http://www.gamasutra.com/view/news/213548/Papers_Please_takes_the_grand_prize_at_16th_annual_IGF_Awards.php.

- Staines, D. (2010). Video games and moral pedagogy: A neo-Kohlbergian approach. In K. Schierer & D. Gibson (Eds.), Ethics and game design (pp. 35–51). Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

- Staines, D., Formosa, P., & Ryan, M. (2019). Morality play: A model for developing games of moral expertise. Games and Culture, 14(4), 410–429. doi:10.1177/1555412017729596

- Stout, M. (2011). Portraits of politicians, administrators, and citizens. Administrative Theory & Praxis, 33(4), 604–609. doi:10.2753/ATP1084-1806330409

- The Oregon Trail [Computer software]. (1975). Brooklyn Center, MN: MECC.

- Thiagarajan, S. (1998). The myths and realities of simulations in performance technology. Educational Technology, 38(5), 35–41.

- Thiagarajan, S., & Thiagarajan, R. (1999). Interactive experiential training: 19 strategies. Bloomington, IN: Workshops by Thiagi.

- Thompson, D. F. (1985). The possibility of administrative ethics. Public Administration Review, 45(5), 555–561. doi:10.2307/3109930

- Waldo, D. (1956). Perspectives on administration. Birmingham, AL: University of Alabama Press.

- Weber, M. (1946). Bureaucracy. In H. H. Gerth & C. Wright Mills (Eds.), From Max Weber: Essays in sociology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- West, W. (2005). Administrative rulemaking: an old and emerging literature. Public Administration Review, 65(6), 655–668. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6210.2005.00495.x

- Where in the World is Carmen San Diego? [Computer software]. (1985). Eugene, OR: Broderbund Software.

- Zhang, D., Xu, Y., Xu, H., & Su, Z. (2015). Chinese comments sentiment classification based on word2vec and SVMperf. Expert Systems with Applications, 42(4), 1857–1863. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2014.09.011