Abstract

Employee reports about suspected integrity violations and other types of wrongdoing are widely acknowledged as an important method for disclosing misconduct and improving the integrity of organizations. Organizations and employees may benefit from appointing Confidential Advisers (CAs) as part of their internal reporting procedures. Confidential Advisers inform employees about internal reporting, support employees in the reporting process, and can advise the organization on the improvement of its integrity management system. As such CAs can lower the threshold for internal reporting, improve the quality of the reports made, increase the chance that a report leads to an internal investigation, and consequently play an important role in resolving raised issues. This article explores how the CA position is currently organized in Dutch organizations and identifies conditions that could be relevant for future improvements based on a mixed–method research design.

The value of employee reports about suspected wrongdoing (also referred to as whistleblowing, Near & Miceli, Citation1985) is widely acknowledged among academic researchers (Brown, Lawrence, & Olsen, Citation2018), employer representatives (Business Europe, Citation2017; ICC, Citation2008), and international institutions like the OECD (Citation2017), the European Union (Citation2019), and the G20 (Citation2018). Managers and integrity professionals also acknowledge reports made by employees as the single most important method for bringing wrongdoings to light and affecting change (Brown et al., Citation2018).

Given the value of employee reports, it is important that employees can report their suspicions safely. Some research however suggests that about half of the reporters face retaliation (Brown et al., Citation2018; Maas, Verheij, Oostdijk, & Wesselink, Citation2014). Retaliation is very broad and includes for instance: termination of employment, forced transfer, demotion, bullying, intimidation, social isolation, delayed promotion, cancelled education, and “suddenly” negative job appraisals.

To understand and improve this situation, it is necessary to distinguish internal reporting (raising concerns within the organization) from external reporting (raising concerns externally, for instance to the media). Most employees go through a “protracted process” of reporting (Vandekerckhove & Phillips, Citation2019) in which they first report suspicions internally before blowing the whistle externally (Brown, Citation2018; Maas et al., Citation2014). In the Netherlands, employees are in the so–called three–tier system even legally obliged to first report internally, before being able to report to an external authority (Loyens & Vandekerckhove, Citation2018, p. 10).

There are important differences between these two types of reporting. Whereas internal reporters are mostly motivated to stop the perceived wrongdoing, external whistleblowers are mostly driven to reveal the injustice about what happened—to them and within their organization (Park, VandeKerckhove, & Lee, Citation2018). More importantly, internal reporters are significantly less likely to suffer negative repercussions than those who take their claims to an external venue (Smith, Citation2018). Organizations also face less negative consequences from internal reporting in terms of fewer costly lawsuits (Stubben & Welch, Citation2018) and reputational damage.

This raises the need for designing internal reporting procedures with a low threshold to report suspicions, protecting reporters from possible retaliation, and solving the matter in such a way that reporters do not feel the need to report outside the designated channels. In Europe, it will become even more pressing to design “attractive” internal reporting procedures, since a new “whistleblowers Directive” from the EU will make it easier for employees to immediately report externally (European Union, Citation2019). In a broader international context, good functioning reporting channels are important as well, since in many jurisdictions employees (especially civil servants) are expected or even obligated to report possible wrongdoings.

One possible measure organizations can take to enhance internal reporting procedures is to appoint Confidential Advisers (CAs), also sometimes referred to as trusted person, confidential counselor, confidential integrity adviser, or confidant(e). Employees can contact CAs to discuss integrity concerns in a confidential setting. The goal of employing CAs is to contribute to the internal reporting system, to lower the thresholds to report, to reduce the risks of reporting, to improve the quality of the reports made, and consequently to help tackling integrity violations or other types of wrongdoing.

As of yet, little research has been done into the CA specifically (De Graaf, Citation2019; De Graaf, Lasthuizen, Bogers, Ter Schegget, & Struwer, Citation2013; Hoekstra, Talsma, & Zweegers, Citation2018) or as subtopic in broader studies into whistleblowing systems (Berendsen et al., Citation2008; Maas et al., Citation2014; Talsma, Hoekstra, & Zweegers, Citation2017). This article examines the current position of CAs in the Dutch context and proposes a set of conditions that may support this position in the future. The article may inspire organizations in other countries to consider appointing CAs as part of their internal reporting procedures.

This article combines both qualitative and quantitative research methods. Central questions to be addressed are: what is the background of CAs in the Dutch context and which roles do they fulfill; under what circumstances do they currently conduct their work as CAs; and what conditions could be proposed for future improvements? As such, this research article consists of five parts. It commences with a short description of the background and setting of the CAs in the Dutch context. Then the research design is introduced. Subsequently the research results from a survey amongst 159 CAs are presented. The fourth section formulates a set of conditions for possible future improvements for this position. In the final section, conclusions and discussion topics are presented.

BACKGROUND AND SETTING OF CAs IN THE DUTCH CONTEXT

In the Netherlands, the concern for integrity was put on the agenda in the early 1990s (Hoekstra & Kaptein, Citation2014). Pre–employment screening, integrity oaths, codes of conduct, integrity training, integrity officers, integrity risk assessments, integrity audits and reports, and investigation procedures are among the many instruments (Hoekstra & Kaptein, Citation2012) that gradually have been adopted to build a coherent integrity management approach (Huberts & Hoekstra, Citation2016).

This article focuses on CAs in the Netherlands. Currently around 90% of the Dutch organizations with more than 50 employees have appointed CAs (Talsma et al., Citation2017). The origin of CAs dates back from 2003. Since then, the Dutch Civil Service Act requires all public organizations to appoint CAs. At the same time, the Social and Economic Council of the Netherlands recommended employers in the private sector to appoint CAs as well. In 2003, there were only little specifications on the exact duties of the CAs since it concerned a new position (Berendsen et al., Citation2008; De Graaf, Citation2019). Over time, the function has gradually taken shape. The development of professional associations, specialized courses, conferences, and network meetings, and even certification systems for CAs illustrate the growing acknowledgement of the importance of this function in the Netherlands. Since 2016, new whistleblowing legislation requires from all employers with more than 50 employees to give employees access to CAs. Today most CAs have three core functions: providing (general) information, offering (specific) support, and giving (anonymized) signals (see ).

TABLE 1 Core Functions of CAs

The position of CAs differs from other positions that can be established in an integrity management system (Hoekstra, Citation2016). CAs do not investigate reports or sanction wrongdoers, unlike compliance officers or internal investigators. CAs are not responsible for the integrity management system as a whole, unlike integrity coordinators or ethics/compliance officers. CAs are neither representatives nor lawyers of the reporters, as they are appointed by their employers and cannot provide complete confidentiality in all possible situations: the Dutch Code of Criminal Procedure obliges everyone (article 160) and civil servants in particular (article 162) to report cases of criminal offences or malfeasance. CAs have to follow this obligation (see Verweij, Talsma, Hoekstra, & Zweegers, Citation2019, p. 45 for a detailed flow chart). Lastly, CAs are not reporting points themselves, unlike contact persons or the staff of whistleblowing hotlines. Instead, CAs inform and advice employees before, during, and after making a report in a whistleblowing channel. As such they make part of the whistleblowing system as a whole and are contributive to its overall functioning.

RESEARCH METHODS

This research is based on a mixed–method design and combines focus groups with an online survey.

Qualitative Research: Focus Groups

Thirty CAs from different types of public and private organizations were invited to participate in focus groups organized in September 2017. The participants were invited based on their experiences as CAs. Next to their experience in years, it was important to verify that they were not “just” confidential harassment advisers (CHAs) primarily advising on sexual harassment (Adams-Roy & Barling, Citation1998; O’Leary-Kelly, Bowess-Sperry, Bates, & Lean, Citation2009) and bullying (Einarsen & Skogstad, Citation1996; Kaplan, Pope, & Samuels, Citation2010) but that they (also) dealt with integrity and wrongdoing issues. De Graaf (Citation2019) points out that in cases of harassment and bullying, it is not the organization, but usually the reporter that is involved (as the victim). In matters of integrity, the organization is generally involved and not the reporter (for the reporter is most of the times merely the witness of integrity violations).

Both experience and the required involvement with integrity/wrongdoing issues were verified in intake interviews. To increase participation opportunities for all partakers, two separate focus group meetings were organized, each with 15 CAs. These meetings were held because not much is known about CAs and therefore an explorative and inductive strategy (Eisenhardt, Citation1989; Glaser & Strauss, Citation1967) seemed to be an appropriate start for understanding the most important issues among these advisers. The focus groups were moderated, semi–structured, documented, and lasted approximately 2.5 h. The outcomes were analyzed by three researchers and summarized in a report that was used as input for the design of the online survey.

Quantitative Research: Online Survey

A recent (a-select and stratified) set of contact details of 993 Works Council members was used to come in touch with one of the CAs in their organization. This resulted in a list of n = 344 CAs forming the gross sample survey for this study. Consequently these CAs were asked (by e-mail and two interim reminders) to participate in this current study via a personal link to an online questionnaire. The fieldwork took place in the period from 16 to 31 January 2018. Ultimately, 159 CAs fully completed the questionnaire (response rate = 46%).

Since no population data of CAs in the Netherlands are available, it is not possible to determine whether the survey sample is representative. However, the survey sample was realized in a careful and transparent manner. All CAs employed in an organization with more than 50 employees ran a chance of being made part of the survey sample. All in all, the process of sampling and taking into account the solid size of the net survey sample provide a significant degree of confidence that the research results form a good indication of the actual situation of CAs in the Netherlands.

It turned out that both (semi–) public and larger organizations were more strongly represented than private and smaller organizations. An explanation could be that in government agencies CAs have been common for a longer period than in the private sector due to legal provisions in the Civil Servants Act (2003). In the research results, however, no notable differences in outcomes between company size and sectoral categories were detected. Where differences were visible, these are mentioned in the discussion of the results.

RESEARCH RESULTS

Individual Characteristics of CAs

The majority of the CAs in the survey is more than 45 years old (83%), higher educated (79%), works for more than 10 years for their current employer (69%), combines integrity advice with harassment advice (89%), fulfills the CA position for more than 3 years (57%), and spends less than 8 h on their designated CA position. 42% spend less than 4 h per month on the confidential work and for a further 30%, this share is between 4 and 8 h per month. In a nutshell, the first impression of the CAs is that of highly educated, senior employees, who know their organizations well, cover both integrity and harassment issues, and fulfilling their CA position additional to their core function.

Complementary Position Versus Core Function

Most CAs fulfill their confidential position part time, complementary to their core function in the organization. In the focus groups it was expressed that the combination of certain core functions could interfere with the confidential work of the CAs. Based on the survey, provides an overview of these particular conflicting core functions and to what extent this occurs.

TABLE 2 Possibly Conflicting Core Functionsa

CAs fulfil a specific role in the reporting procedure: they advise employees on a case level. It may constitute a risk to mix this position with functions like HRM, Audit and management, since this could lead to (perceived) conflicts of interest. Two in three CAs report not to be involved in such high–risk job combinations, which implies that one–third of the CAs do combine possible conflicting functions.

Organizational Provisions and Facilities for CAs

Based on the input of the focus groups, a set of survey questions was formulated that pertains to the organizational support and facilities that are considered important for CAs to perform well. shows, in descending order, the extent that these facilities are present within their organizations and indicates that most CAs are positive about the support and facilities they receive from management, their exchange with peers, and the training and the time they get from the organization to conduct their specific position adequately. About one in five CAs reported that they did not have a suitable room in which they could talk to employees discretely, and about the same percentage reported that they did not receive enough reports to sufficiently develop the skills required for their specific position. Both aspects are however important. In the focus groups, it was expressed that employees often experience a visit to a CA to discuss a delicate matter as uncomfortable and stressful. This is why it is vital that they can consult the CA discretely and out of sight of colleagues and managers. It is also important that CAs have sufficient “case–load.” The more consultations CAs have, the more experience and expertise they will build up. In the focus groups it was emphasized that sufficient case–load is connected with sufficient visibility. It is considered a shared responsibility of both the organization and the CAs themselves to actively profile and communicate the existence and role of the CAs.

TABLE 3 Organizational Support and Facilities for CAsa

The results of the study also indicate that regular intervision and exchange of ideas with other CAs scores relatively weak. Intervision can be defined as a form of work–related learning, aimed at improving the (quality of) work of professionals through peer conversations about experiences, best practices and dilemmas. CAs reported a need for intervision before (Berendsen et al., Citation2008, p. 51). This lack of interaction may explain why a quarter of the respondents currently feel “lonely” in the performance of their role. In functional terms, this seems to be an undesirable situation as intervision, exchange, and access to sparring partners enables the CA to reflect on difficult cases and to learn from each other (De Graaf et al., Citation2013).

Number and Types of Consultations and Reports

The average number of consultations that CAs annually conduct on integrity issues and other forms of wrongdoings appears to be relatively low. About 13% of the CAs has more than five consultations per year about possible wrongdoings. More consultations are about harassment and undesirable behavior: 32% of the CAs has more than five consultations per year about such issues.

However, the fact that there are few consultations does not necessarily indicate that there are also few issues. The opposite seems to be more likely, which is also known as the “integrity paradox” (Huberts, Citation2014, p. 238): more consultations indicate higher integrity awareness; higher awareness of the existence of the CA; and more employee confidence in the CA’s role. In order to obtain a picture of the types of integrity violations on which CAs have received consultations, a widely used typology (Lasthuizen, Huberts, & Heres, Citation2011) was presented to the respondents. provides an overview and demonstrates that questions on “social integrity” (discrimination, bullying and sexual harassment) did occur more frequently in this study than questions on “material integrity” (theft, fraud, wastage, etc.). This is consistent with the study of De Graaf et al. (Citation2013).

TABLE 4 Integrity Violations Mentioned in Consultations

Trust, Safety, and Confidentiality

CAs are part of the organizational efforts to improve and protect its ethical culture. But as previous research showed, CAs are not capable of changing an entire culture on their own (Berendsen et al., Citation2008, p. 49). They thus have to work against the background of their organizational culture, which can either be helpful or harmful.

The surveyed CAs were therefore asked to what extent they felt trusted by employees and management and had to respond to a set of statements about the organizational culture, feelings of safety among employees, and matters of confidentiality. The questions are linked to the willingness of employees to report, for the safer they feel, the more likely they dare to raise wrongdoings. shows the results.

TABLE 5 Trust, Safety, and Confidentialitya

Overall, 18% agree with the statement that there is a culture of fear. Correspondingly a similar percentage (16%) of the respondents state that employees do not feel free to voice internal criticism, whereas 21% state that employees do not feel free to report wrongdoings. The CAs are thus fairly critical of the organizational culture, which is consistent with previous research among works council representatives (Talsma et al., Citation2017). The results relating to the perception of safety of the CAs themselves indicate that 11% believe that the CA position could harm their career, and 10% have occasionally considered giving up the confidentiality work due to a sense of insecurity. This is in line with earlier research, which reported a CA stating: “It is not a safe position: the CA is not loved by management.” (Berendsen et al., Citation2008, p. 50, our translation).

In the focus groups was repetitively expressed that “confidentiality is of the essence for CAs.” Nevertheless, confidentiality cannot always be guaranteed. It is limited in case of criminal offences or malfeasance (Verweij et al., Citation2019). CAs must then advise employees to contact the police or the public prosecutor. If the employee refuses, the CA is obliged to do it anyway, which would reveal the identity of the reporter. Therefore the CAs must be entirely open about their roles and responsibilities from the very first consultation. There seems to be more uniformity on this issue than ten years ago, when CAs reported considerable differences in the confidentiality their organization allowed them to provide (Berendsen et al., Citation2008, p. 50). Nevertheless, it remains a troublesome issue within this professional group (as was repeatedly expressed during the focus group sessions). De Graaf (Citation2019) found as well that CAs struggle with managing the expectations of employees.

Half of the surveyed CAs stated that they explain in every initial consultation that they cannot guarantee confidentiality in the mentioned circumstances, whereas 32% of the respondents refrain from doing so. Moreover, about 15% of the respondents stated that they have had to breach confidentiality on occasion. In the focus groups, participants stressed that confidentiality is only breached in serious circumstances and with precaution.

Formalization of the CA Position

The surveyed CAs were asked about several aspects of the formalization of their position. More than 40% of the respondents stated that they had to formally apply for the position of CA, while the others were contacted about this position in a more informal manner. In 40% of the cases, the Works Council was involved in the selection procedure, (top) management in more than 60% of the cases, and compliance/integrity officers in only 7%. About one–quarter of the organizations did not impose any specific job requirements for appointing CAs. Almost 70% of the organizations prescribed a training course for CAs as a requirement. Pre–employment screening (8%) and psychological assessment (2%) scored lowest as job requirements.

In some cases, the agreements on the tasks and performance of the CA were recorded in writing in a specific job profile (50%) or via an appointment decision (37%). In about one–third of the cases, the agreements and tasks were only discussed verbally, or not discussed at all. 40% of the respondents stated that their performance was evaluated, compared with 20% who stated that evaluation did not take place at all and 35% who indicated that there was no formal evaluation.

CAs as part of the integrity management system

De Graaf (Citation2019) emphasizes the importance of the internal reporting system and the CA as part of the broader organizational integrity policies. Therefore, a set of questions was included in the survey aimed to provide insight into the existence of such policies and measures (). In addition the degree of integration of the confidentiality position in these and related policy measures was determined ().

TABLE 6 Existence of Integrity Policies and Measures Within the Organizationsa

TABLE 7 Degree of Integration of the CAs Role in Related Policy Measuresa

shows that the CAs have a somewhat mixed appreciation of the integrity policies of their organizations. The rules and procedures seem to be in place, whereas for a number of other measures there seems to be room for improvement. These scores are consistent with the study among works councils, which were also critical of the presence, the familiarity with, and the quality of important integrity provisions (Talsma et al., Citation2017).

presents an overview of possible activities that seem rather obvious for the CA to contribute to. These activities seem to be opportunities to raise awareness of the CAs and to incorporate their role in the organizational integrity policies. In the focus groups, it was also emphasized that the CAs should be more than “a shoulder to cry on,” and have a broader role to address: “the CA’s role should not be seen as too limited and isolated. A broader role interpretation of the CAs will be contributive to their effect and impact within the organization.”

PROPOSING CONDITIONS FOR INCREASING CA EFFECTIVENESS

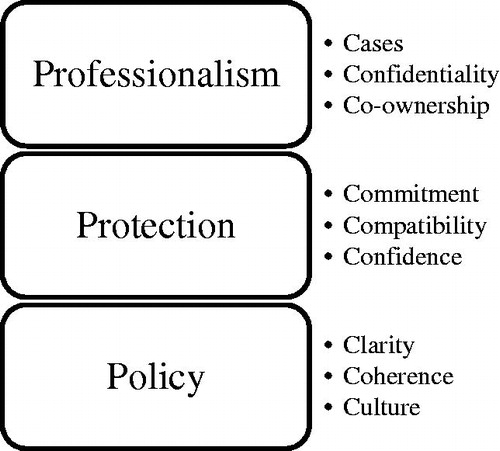

In this section, nine conditions are proposed that may influence the effectiveness of CAs. These conditions will be grouped in three themes (professionalism, protection, and policies). The conditions are formulated in order to get more grip on the issues that could increase CA effectiveness and are based on this study. They are first visualized in and then discussed.

Professionalism: Cases, Confidentiality, and Co–ownership

The first conditions can be grouped in the theme of professionalism. For CAs to perform well, they need to be able to develop and maintain a sufficient level of professionalism. This demands enough practice and experience (cases), sensitivity and skill in dealing with information (confidentiality), and clear communication about the CA’s dual role (co–ownership).

The first condition for a CA to perform well is having enough practice and experience, which is the basis for professionalism. This requires a sufficient number of cases. Preferably, there are enough consultations and reports to become and remain skilled. Additionally, cases can be simulated during training, and cases of other CAs could be discussed during intervision. Training could also be used to practice specific skills and to gain relevant knowledge.

Secondly, confidentiality is the essence of the CA, but also limited. It entails professionalism from CAs to manage expectations about the limits of confidentiality properly, without scaring off potential reporters. Clear communication about this is an important condition for an effective fulfillment of the CA function. This is not an easy task. It demands sensitivity and skill. De Graaf (Citation2019, p. 14) puts it very well: “The art is to be clear—on the one hand—about the important matter of confidentiality, and—on the other hand—not to scare off the potential reporter.”

The third condition pertains to co–ownership. CAs have two “owners” and thus a dual role to fulfill. First of all they inform and provide support to employees. Yet, CAs also have valuable insights on the risks and ethical issues that are current in the organization, which can (in an anonymized form) be presented as advice for management. For reporters who are distrustful of the organization, it can be hard to accept that “their” confidential advisor is also an adviser to the organization. It requires professionalism of the CA to mitigate the possible tensions of this role duality.

Protection: Commitment, Compatibility, and Confidence

The second theme in which several conditions can be grouped is protection. For a CA to perform his work well, there needs to be sufficient safety. This demands real support from the organization (commitment), avoidance of high–risk role combinations (compatibility) and trust between CA, employees, and management (confidence).

A strong organizational commitment is most prominently shown in the level of formal protection that CAs themselves receive against possible retaliation. It is recommended that employers offer their CAs formal protection against retaliation in, for instance, their appointment letters, job descriptions, or in the internal reporting procedure. Another possible measure would be to give CAs the same legal protection as whistleblowers (something which EU member states will be obliged to do, following art.4-4 of European Union, Citation2019). Furthermore, commitment must also be shown in terms of appreciation and adequate resources. The focus groups cautioned: “management should show strong and sincere commitment for the CA’s position, if you get the feeling that it is just window–dressing then don’t do it.”

The second condition is compatibility. Most CAs fulfill this position part–time, next to their “main” jobs in the organization. Compatibility of these two roles protects the CA from unnecessary risks, or framed negatively: high–risk role combinations should be avoided (such as HRM, management, internal investigations). This protects CAs from perceived conflicts of interest.

Confidence and trust between the CA, employees, and management are also important for the safety of the CA. It is necessary for CAs to feel secure in their position, and for employees to feel secure to speak with the CA. This research indicates that CAs sometimes fear negative consequences of their CA position. On the other hand, CAs are prone to overestimate the confidence employees put in them. It would be helpful for CAs to gain a realistic insight into the way management and employees think about them, for instance, through surveys. This data may help to indicate when and where confidence needs to be restored.

Policy: Clarity, Coherency, Culture

The third theme is the embeddedness of the CA in broader integrity policies. For CAs to perform well, they need to be supported by other integrity measures. This requires that it must be clear what exactly the role of the CA entails (clarity), that this position is part of broader integrity policies (coherency) and that the CA operates against a healthy informal background (culture).

First of all, it must be clear to the CA, management, and the organization what is expected of the CAs, what they can and cannot do. This entails formalization of: procedures for selection and appointment; protection against retaliation; job descriptions; instructions regarding (breaking) confidentiality; evaluations of processes of CA performance; and how to terminate a CA appointment in case of obvious inadequacy. Such clear policies and procedures also stimulate the organization to formulate a more carefully considered vision of the confidential work.

Secondly, CAs cannot be effective as “standalone” measures. They ideally make part of the internal reporting procedure and of the broader integrity management system. Together these measures should be coherent and interconnected. For instance, the code of conduct and introductory programs should refer to the CA. This also implies efforts for the CAs themselves, for instance by: communicating their roles clearly; putting energy in the “acquisition of clients”; writing annual reports; and by participating in the development of integrity programs. Such embeddedness in the broader integrity policies ensures that the position of CA is best put to use.

And thirdly, CAs have to work against the background of the organization’s culture. Unsafe organizational cultures increase the threshold for employees to meet with the CA. Well performing CAs could have a positive influence on the organizational culture, but it is also clear they cannot change the culture on their own. Neither can it be expected that integrity policies and systems change a bad organizational culture overnight. This underscores the need for making continuous efforts to build ethical cultures and requires well–developed integrity policies.

CONCLUSION AND DISCUSSION

This article describes how the CA position is organized in Dutch organizations. From our research, the picture emerges of a CA as a highly educated, senior employee, who knows the organization well, covers both integrity and harassment issues, and fulfills his CA tasks in a complementary (part–time) position. This implies that CAs (and their organizations) should be aware of possible role conflicts with their “core” functions (for instance combining HR or management functions with the CA position). CAs are quite positive about the organizational support and facilities they get, although their “housing” and “case–load” are problematic. As for the case–content, the research indicates that CAs are more often consulted about “social integrity” violations (like bullying and harassment) than about “material integrity” violations (like theft and fraud), which is consistent with other studies.

CAs also appear to be prone to self–bias as they are more confident about the trust that employees have in them than is justified—as was demonstrated by other recent research. A too positive self–image on such a crucial aspect of the CA’s work can, however, be dangerous as it may temper the CA’s efforts to actively communicate about his important work and trustworthy position. The CA’s assessment of the organizational culture and of his own (un)safety proves to be quite worrisome, since this may negatively influence both the willingness of employees to voice their concerns and the unconstrained performance of the CA. As for the formalization of the CA position (e.g., selection procedure, job description and evaluation), there seems to be some room for improvement. This is the same for the existence of integrity policies and measures within organizations, and for the degree of integration of the CA’s role in these polices and measures.

Based on these mixed research results, there seems to be scope for further improvement and progress. Nine conditions (grouped in three themes) are proposed that may positively influence the CA’s effectiveness. These conditions and themes are inspired by the results of this research, but are of a more prescriptive nature. The conditions have to be empirically tested to assess their impact on the CAs effectiveness. Questions for future research are: to what degree is the CA position truly unique to the Dutch situation? Would this position fit within the legal and institutional context of other countries? What is the influence of CAs on their organizational leaders, for instance through their synthesized, anonymized annual reports? To what extend are reporters positive about the CA’s effectiveness to (help) disclose and remedy the raised concerns? And lastly, the new EU–directive on this issue will bring about more uniformization and less differences between reporting systems in different countries. Should the EU promote the CA as “facilitator” (European Union, Citation2019, art. 5–8) and as an indispensable element next to the already obliged “impartial person or department competent for following-up on the reports” (European Union, Citation2019, art. 9-1c) in the internal reporting channels required by the new Directive?

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This chapter was initially presented as a working paper for the International Whistleblowing Research Network (IWRN) Conference on June 21 2019, hosted by the Utrecht School of Governance in The Netherlands and is based on previous research of the authors (Hoekstra et al., Citation2018). We thank our fellow researchers and experts for their valuable feedback on this article. In particular: Gjalt de Graaf, A.J. Brown, Kim Loyens, and Wim VandeKerckhove.

REFERENCES

- Adams-Roy, J., & Barling, J. (1998). Predicting the decision to confront or report sexual harassment. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 19(4), 329–336. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-1379(199807)19:4<329::AID-JOB857>3.0.CO;2-S

- Berendsen, L., Bos, A., Bovens, M., Brandsma, G. J., Luchtman, M., & Pikker, G. (2008). Evaluatie klokkenluidersregelingen publieke sector. Utrecht, The Netherlands: USBO.

- Brown, A. J. (Ed.). (2018). Whistleblowing: new rules, new policies, new vision (Work-in-progress results from the Whistling While They Work 2 Project). Brisbane, Australia: Griffith University.

- Brown, A. J., Lawrence, S. A., & Olsen, J. (2018). Why protect whistleblowers? Importance versus treatment in the public & private sectors. In A. J. Brown (Ed.), Whistleblowing: new rules, new policies, new vision (work-in-progress results from the whistling while they work 2 project) (pp. 27–52). Brisbane, Australia: Griffith University.

- Business Europe. (2017). Position paper on whistleblower protection in the EU. Brussels, Belgium: Business Europe.

- De Graaf, G. (2019). What works: The role of confidential integrity advisors and effective whistleblowing. International Public Management Journal, 22(2), 213–231. doi:10.1080/10967494.2015.1094163

- De Graaf, G., Lasthuizen, K., Bogers, T., Ter Schegget, B., & Struwer, T. (2013). Een luisterend oor. Onderzoek naar het interne meldsysteem integriteit binnen de Nederlandse overheid. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Onderzoeksgroep Quality of Governance.

- Einarsen, S., & Skogstad, A. (1996). Bullying at work: Epidemiological findings in public and private organizations. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 5(2), 185–201. doi:10.1080/13594329608414854

- Eisenhardt, K. (1989). Building theories from case study research. Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 532–550. doi:10.5465/amr.1989.4308385

- European Union. (2019). Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on the protection of persons who report breaches of Union law. 2018/0106 (COD), LEX 1965.

- G20. (2018). G20 Anti-Corruption Action Plan 2019-2021. Published in: OECD, Directorate For Financial And Enterprise Affairs Working Group On Bribery In International Business Transactions, G20 Anti-Corruption Working Group Action Plan 2019 – 2021 and Extract from G20 Leaders Communiqué, 11-14 December 2018

- Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Chicago, IL: Aldine Publishing Company.

- Hoekstra, A. (2016). Institutionalizing integrity management: Challenges and solutions in times of financial crises and austerity measures. In A. Lawton, Z. van der Wal, and L. W. J. C. Huberts (Eds.), Ethics in public policy and management: A global research companion (pp. 147–164). Oxon, UK; New York, NY: Routledge.

- Hoekstra, A., & Kaptein, M. (2012). The institutionalization of integrity in local government. Public Integrity, 15(1), 5–27. doi:10.2753/PIN1099-9922150101

- Hoekstra, A., & Kaptein, M. (2014). Understanding integrity policy formation processes: A case study in The Netherlands of the conditions for. Public Integrity, 16(3), 243–263. doi:10.2753/PIN1099-9922160302

- Hoekstra, A., Talsma, J., & Zweegers, M. (2018). The confidential integrity advisor. Current status and future prospects in the Netherlands. Utrecht, The Netherlands: Dutch Whistleblowers Authority.

- Huberts, L. (2014). Integrity of governance. What it is, what we know, what is done and where to go. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Huberts, L., & Hoekstra, A, (Eds.). (2016). Integrity management in the public sector. The Dutch approach. Hague, The Netherlands: BIOS.

- ICC. (2008). International chamber of commerce guidelines on whistleblowing. Paris, France: International Chamber of Commerce.

- Kaplan, S. E., Pope, K. R., & Samuels, J. A. (2010). The effect of social confrontation on individuals’ intentions to internally report fraud. Behavioral Research in Accounting, 22(2), 51–67. doi:10.2308/bria.2010.22.2.51

- Lasthuizen, K., Huberts, L., & Heres, L. (2011). How to measure integrity violations. Towards a validated typology of unethical behavior. Public Management Review, 13(3), 383–408. doi:10.1080/14719037.2011.553267

- Lawrence, S. A. (2018). What else makes a difference? Testing other key factors for effective whistleblowing management. In A. J. Brown (Ed.), Whistleblowing: New rules, new policies, new vision (Work-in-progress results from the Whistling While They Work 2 Project) (pp. 109–131). Brisbane, Australia: Griffith University.

- Loyens, K., & Vandekerckhove, W. (2018). The Dutch Whistleblowers Authority in an international perspective: A comparative study. Utrecht, The Netherlands: USBO.

- Maas, F., Verheij, T., Oostdijk, A., & Wesselink, T. (2014). Veilig misstanden melden op het werk. Utrecht, The Netherlands: Berenschot.

- Near, J. P., & Miceli, M. P. (1985). Organizational dissidence: The case of whistle-blowing. Journal of Business Ethics, 4(1), 1–16. doi:10.1007/BF00382668

- OECD. (2017). OECD recommendation of the council on public integrity. Paris, France: OECD.

- O’Leary-Kelly, A. M., Bowes-Sperry, L., Bates, C. A., & Lean, E. R. (2009). Sexual harassment at work: A decade (plus) of progress. Journal of Management, 35(3), 503–536. doi:10.1177/0149206308330555

- Park, H., Vandekerckhove, W., & Lee, J. (2018). Laddered motivations of external whistleblowers: The truth about attributes, consequences, and values. Journal of Business Ethics, 1–14.

- Smith, R. (2018). Processes and procedures: Are organisational policies linked to reporter treatment? In A. J. Brown (Ed.), Whistleblowing: New rules, new policies, new vision (work-in-progress results from the whistling while they work 2 project) (pp. 67–80). Brisbane, Australia: Griffith University.

- Stubben, S., & Welch, K.T. (2018). Evidence on the use and efficacy of internal whistleblowing systems. Retrieved from https://ssrn.com/abstract=3273589

- Talsma, J., Hoekstra, A., & Zweegers, M. (2017). Reporting procedures and integrity provisions among employers in the Netherlands. Utrecht, The Netherlands: Dutch Whistleblowers Authority.

- Vandekerckhove, W., & Phillips, A. (2019). Whistleblowing as a protracted process: A study of UK whistleblower journeys. Journal of Business Ethics, 159(1), 201–219. doi:10.1007/s10551-017-3727-8

- Verweij, L., Talsma, J., Hoekstra, A., & Zweegers, M. (2019). Integrity in practice: The confidential integrity adviser. Utrecht, The Netherlands: Dutch Whistleblowers Authority.