Abstract

As academic managers, college deans, associate deans, assistant deans, department chairs, and program coordinators play pivotal leadership roles within universities. It is, therefore, crucial to understand their organizational behavior. Without ascribing causal values to conduct, this study hypothesizes that academic managers repeatedly practice workplace hypocrisy. To test this postulation, the study seeks to identify the characteristics of perceived hypocrisy before exploring the possible similarities between hypocritical behavior and toxic leadership behavior. The data were obtained via open-ended questions answered by 175 academic managers and 517 professors working in 13 universities. The results of the analyses support the initial hypothesis: 81% of all respondents reported experiencing more than one hypocritical incident in the last year; 84% of the academic managers and 64% of the professors testified to being directly affected by first-hand hypocrisy. The responses revealed four groups of hypocritical characteristics; dishonesty, attacking others, disregard to institutional wellbeing, and disingenuous personality. Similarities between hypocritical and toxic characteristics were discussed followed by theoretical and practical implications of the findings.

Introduction

Publicly-funded universities are an integral part of public administration and their employees are civil servants who should maintain the integrity, reputation, and role of their institutions in the society. College deans, associate deans, assistant deans, department chairs, and program coordinators are academic managers and civil servants who play leadership roles to produce value for their society while serving their respective units (Yaghi & Al-Jenaibi, Citation2018). Therefore, it is essential to examine the unethical behavior exhibited by academic managers and highlight the similarities between hypocritical and toxic characteristics. Leadership behaviors. The examination of hypocrisy can more appropriately identify the varied representations of unscrupulous conduct within the larger ambit of leadership behavior evinced in public institutions of higher education (i.e., universities) and their role in serving public interest (Moulton, Citation2009). The last decade has witnessed an increasing volume of research concerning toxic leadership, one of the most pervasive forms of unethical behavior, and its impact on organizational outcomes such as turnover, low quality of work life, and poor commitment (Alzahrani, Citation2019; Yaghi & Aljaidi, Citation2014; Yaghi & Yaghi, Citation2014). The extant literature on leadership has extensively discussed wide-ranging types of unethical behavior that can largely be described as aggressive, harsh, easily noticeable, and evidently negative in its aspects. Some examples of toxic leadership comprehensively investigated by scholars include destructive, abusive, bullying, and tyrannical conduct (Pelletier, Citation2010; Yaghi, Citation2019). Despite the significance of all toxic behaviors, including hypocrisy, only a few studies have, to date, highlighted the soft forms of non-aggressive, indirect, and difficult-to-notice toxic leadership that is represented by hypocrisy. In addition, most of the extant management and organizational scholarship on organizational hypocrisy has attended to the collective or macro level of organizations practicing hypocrisy by, for example, failing to match their rhetoric with their actions, primarily apropos of corporate social responsibility (Brunsson, Citation1986; Duthler & Dhanesh, Citation2018).

The appraisal of the role performed by culture is beyond the scope of the current study. Research has, however, established that in traditional societies such as the Arab countries, people tend to espouse conservative value-sets that may influence their perceptions of hypocrisy. For example, Arabs place a high value on group cohesion (collectivism), modesty, and saving face (Al-Kindi & Bailie, Citation2015). With respect to universities, Arabic communities generally tend to idealize professors (faculty members) and regard them as moral agents (Alzahrani, Citation2019). Congruently, the collection of data regarding hypocritical behavior can be a difficult task in such societies because the mere suggestion of immoral conduct on the part of educators can be appalling (Al Hafyan, Citation2009; Mohamed & Biljit, Citation2018). The present investigation is not culturally motivated, nor does it focus on the role played by culture. Nevertheless, relatively speaking, this study is located within a culturally homogeneous region of the Arab world that has not been adequately explored in the extant scholarly literature on leadership or hypocrisy (Yaghi, Citation2017). It is pertinent to note that most cases of unethical conduct in higher education are handled internally by the concerned educational institution without involving external agents such as researchers or the media (Bozwagh, Citation2017; Mahmood, Citation2008). Even when certain newspaper journalists have reported instances of immorality, misconduct, sabotage, corruption, or bullying, the cases are reviewed conscientiously without disturbing the public’s idealistic social beliefs about universities (Dayyeh & Skakiyya, Citation2018; Mahmood, Citation2008).

The lexical definition of the word “hypocrisy” accords a brief but impressively accurate explanation of the two elements that generate this behavioral practice: lying (conveying inauthentic information) and deception (the mismatch between intent and action). Hypocrisy is “behavior that contradicts what one claims to believe or feel” (Webster.com). The deceitful aspect of hypocrisy can also be found in the term’s Greek origin: hypo signifies “acting in an unreal manner” and cris means “to decide or determine.” When they are combined, the terms denote “to stage something that is unreal” (Webster.com). Hypocrisy is nefak in the Arabic cultural context. The Holy Quran condemns what it describes as “saying or doing things that contradict reality with the intent of deceiving someone” because garnering benefits at the expense of other people disrupts social cohesion and ignites conflict among people (Eshtawi, Citation2016; Wahab & Ismail, Citation2019). Nevertheless, the cultural inheritance of strong community values that condemn hypocrisy does not accord organizational immunity against hypocrisy (Al Addasi, Citation2001; Suyuti, Citation2017).

This investigation is grounded in the assumption that academic managers behave toxically when they are hypocritical because (a) hypocritical managers hurt others and (b) although hypocrisy is a soft form of toxicity, hypocritical managers exhibit many toxic traits. To test this hypothesis, it explores how faculty members perceive the hypocrisy of their superiors or peer managers. In this manner, the study intends to map the primary behavioral features of the perceived hypocritical behavior. Subsequently, the paper tests its initial assumption through the elucidation of the possible similarities between the mapped characteristics and the attributes of toxic leadership documented in the extant literature (Padilla, Hogan, & Kaiser, Citation2007; Pelletier, Citation2010).

Hypocrisy is toxic because it causes injury to others (Younus et al., Citation2019). Although hypocrisy is secretive and hypocritical individuals purposefully tend to conceal their intentions and actions from others, the conduct of hypocrisy represents the softer, more indirect, and undisclosed form of toxic behavior. Conversely, the forms of adverse behavior that are debated in the existing leadership literature include the harmful (Pelletier, Citation2010), destructive (Einarsen, Aasland, & Skogstad, Citation2007), abusive (Tepper, Citation2000), tyrannical (Ashforth, Citation1994), bullying (Yaghi, Citation2019), and toxic activities (Lipman-Blumen, Citation2005). These types of actions may be described as hard and direct because they are not hidden and cannot indirectly harm other people. Researchers have reported very little information as regards organizational hypocrisy at the individual-level (micro). This paper avails of the accumulated knowledge on toxic leadership to overcome the difficulties posed by the paucity of research on organizational hypocrisy at the individual-level. It utilizes the available scholarly research data and discussions to establish fundamental similarities between toxicity and hypocritical practices for researchers to examine further in the future. In particular, the conceptual constructs of the typology of harmful behavior (Pelletier, Citation2010, p. 375) and the toxic leadership triangle (Padilla et al., Citation2007) are utilized in the sections that follow.

Theoretical Grounding and Review of Relevant Literature

Several characteristics connect toxicity with hypocrisy, such as lacking integrity, attacking others, causing social exclusion, promoting inequality, laissez-faire, divisiveness, threatening others, and abusiveness. While these characteristics make hypocrisy an integral part of toxicity, discussing the two terms overlaps. The toxic nature of hypocrisy suggests that hypocrisy is a viable vehicle for toxicity to inflict harm on others. Therefore, toxicity of hypocritical leadership behavior is not an isolated phenomenon.

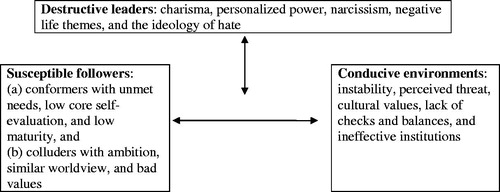

In order to exercise the soft form of toxicity, hypocritical managers may possess toxic characteristics but three factors are needed to enable the toxicity of hypocritical managers: toxic leaders, susceptible followers, and conducive environments () (Padilla et al., Citation2007, p. 180). Hypocritical managers may exhibit toxicity through silence (e.g., poor engagement), inaction (e.g., laissez-faire attitude, unwillingness to support others), late action (e.g., adaptive, or exaggerated flexibility), poor action (e.g., imitating others), deception (e.g., covering-up wrongdoings), and double standards (e.g., insincerity, misleading others, or evaluating them on varying scales) (Pope, Citation2015).

FIGURE 1 Model of toxic behavior (Padilla et al., Citation2007).

Dishonest managers are toxic and they often lie, mostly about workplace threats, aiming to deceive others by exaggerating the external threats. Similarly, they disregard the wellbeing of their institution and its members by fabricating common enemies in the hope of distracting their subordinates and peers to compel them to rally behind them, especially faculty members who possess certain amenabilities or characteristics that make them susceptible to deception (Padilla et al., Citation2007; Pope, Citation2015). If others resist to comply or if they try to expose the deception of the manager, the latter may attack them aiming to discredit them by actions, for example, such as questioning their loyalty and backbiting. describes susceptible followers as conformers or colluders. Conformers have unmet needs and low self-esteem and tend to lack emotional maturity. Thus, they tolerate hypocritical superiors to satisfy some of their own unsatisfied wants. Colluders are ambitious and toxic as they themselves are hypocritical (Chamberlain & Hodson, Citation2010). Toxicity of hypocritical leaders needs a conducive environment that facilitates their toxicity notwithstanding the personalities of their followers () (Padilla et al., Citation2007). Unstable workplace environments foster unconstructive conditions that result in poor organizational outcomes, facilitate bribing, and continuation of inconsistent behaviors and exploitation of workers (Taiwo, Citation2010; Yaghi, Citation2016; Yaghi & Yaghi, Citation2013). Padilla et al. (Citation2007) explain that hypocritical managers- who usually lack competency- favor ad-hoc committees that allow them to avoid checks and balances over standing committees governed by strict rules and regulations. Such flexible decision-making systems combine with informal communication to create loopholes that allow hypocritical managers who manipulate institutional systems (regulations and procedures) to take advantage of others to achieve selfish ends (Yaghi, Morris, & Gibson, Citation2007). Laissez-faire appears to be a soft form of the many types of toxicity observed in hypocritical organizational leadership that injure others. Noninterventionist leaders employ excessive tractability, informal means of communication, the false appearance of goodness, and fake friendliness to achieve their objectives (Xirasagar, Citation2008; Yukl, Citation1999). Laissez-faire managers show hypocrisy by utilizing eloquence to conceal their incompetency and poor leadership skills (Sharma & Singh, Citation2013). Unfortunately, notwithstanding the reporting of hard (e.g., bullying) or soft toxic leadership (e.g., hypocrisy), the extant literature primarily concerns only those forms of damaging outcomes that are noticeable, measurable, or judicable through effects such as turnover or low job satisfaction (Shaw, Erickson, & Harvey, Citation2011).

As has been mentioned above, the cultural and sociological aspects of hypocrisy are beyond the scope of this study. Noteworthily, however, hypocrisy may frequently be practiced even within traditional societies that tend to value honesty such as the Arab communities. Principles akin to integrity, modesty, and honesty usually coexist with other values that can be misused: natural respect for authority, the impetus to “save face,” and the inclination toward conformity rather than confrontation. For people who live in conservative communities, hypocrisy can become a vehicle for toxic behavior without being easily exposed (Yaghi, Citation2017). Unlike the harder, more noticeable forms of toxic behavior such as rudeness or bullying, hypocrisy provides a secreted platform for people to exercise immorality while simultaneously maintaining virtuous personae (Nevicka, De Hoogh, Den Hartog, & Belschak, Citation2018). Faculty members may adopt hypocrisy because they fear retaliation (e.g., social exclusion) or social condemnation (e.g., stigmatization). They may appreciate the importance of being socially accepted and culturally fit, therefore they deceive others by, for example, pretending to be friendly or flexible (Hale, Citation2012). The practice of hypocrisy remains attractive to organizational members who are eager to advance self-interests without disturbing social mores regardless of the price others have to pay as a result (Neves & Story, Citation2015). Nevertheless, the present study is focused on mapping the behavioral characteristics of hypocrisy rather than discovering why academic managers behave hypocritically. It is thus hypothesized that academic managers in the surveyed universities repeatedly practice organizational hypocrisy (Proposition 1). As previously mentioned, notwithstanding the differences between hard and soft toxic behaviors, toxicity by definition inflicts injury on others in any form. It is therefore postulated that toxic and hypocritical behaviors share common themes (Proposition 2).

METHODOLOGY

Case Selection

This study utilized qualitative data unlike most of the previously conducted research on this subject. The research team selected thirteen publicly funded universities in six Arab countries that were selected for convenience: Jordan, Egypt, Lebanon, Morocco, United Arab Emirates, and Tunis. These countries are renowned for their advanced higher educational systems and internationally accredited programs. It was possible to group these universities because they evince similar rankings, structures, governance systems, and curricula (Herrera, Citation2007; Noori & Anderson, Citation2013).

Data Collection

The team of researchers navigated the websites of each university and compiled a list of 977 accessible email addresses of full-time faculty members to whom three open-ended questions were sent. An aggregate of 692 complete responses was received after several waves of email messages and reminders, totaling to an acceptable 71% response rate (Babbie, Citation2020). Responses were received from 517 professors (educators without administrative titles) and 175 academic managers (professors with administrative titles such as college dean, associate dean, assistant dean, department chair, or program coordinator). All responses were thematically analyzed to identify the behavioral characteristics of perceived hypocrisy without distinguishing universities or countries. presents the demographic statistics collected for the sample of 62% male and 38% female respondents. As illustrated in indicates, faculty members formed the larger portion of the sample because they were targeted as subordinates who could describe the behavior of their academic managers such as deans and department chairs at the college level.

TABLE 1 Demographic distribution of the study sample.

Data Analysis

In order to test the two propositions of the study, three questions were emailed to the targeted sample to identify the behavioral characteristics of organizational hypocrisy:

In the past year and in your current workplace, have you experienced and/or witnessed an academic manager who repeatedly (more than once) behaved in a manner you would consider hypocritical?

If yes, please describe at least one incident of hypocrisy in as much detail as you can remember but without mentioning names.

If applicable, please explain the unpleasant outcomes caused by the incident such as any kind of damage or injury to you or to others.

The grounded theory approach was utilized to develop a coding system for the collected qualitative data (Martin & Turner, Citation1986). The limited availability of management research on organizational hypocrisy specifically related to the micro-level of individuals, the behavioral dimensions of hypocrisy were interpolated from the extant scholarship in the domains of philosophy, psychology, and organizational research (Turner, Citation1990; Younus et al., Citation2019). The coding of responses was done in two stages according to the directions of qualitative analysis obtained from Chowdhury (Citation2015) and Miles, Huberman, and Saldana (Citation2014). Initially, the research team scrutinized the available literature to compile a list of codes derived encompassing two areas in which hypocritical behavior could be detected: (1) perceptions about the nature of hypocritical behavior and (2) insights about the harm it may cause (Alicke, Gordon, & Rose, Citation2013; Younus et al., Citation2019). The responses were coded contextually by the identification of words and themes in full paragraphs because Arabic writing tends toward long iterations. Thus, the examination of complete paragraphs yields the intended meaning more faithfully than the translation of individual statements. In the second stage, four colleagues specialized in qualitative and mixed research methodologies assisted the researchers to validate the coding system. The validation process successfully created inter-rater reliability based on four independently performed coding structures. After the changes suggested by the expert team were applied, the coding scheme was tested, revealing an acceptable inter-rater reliability ratio of 0.92.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Proposition 1 postulated that academic managers behave hypocritically as 85% of them reported experiencing, more than once, hypocritical behaviors displayed by superiors or colleague managers. Overall, 82% witnessed at least one hypocritical incident that involved others and 88% reported first-hand experience of hypocrisy directly involving the respondent. These numbers suggest that the demonstration of hypocritical conduct is a major behavior that academic managers practice.

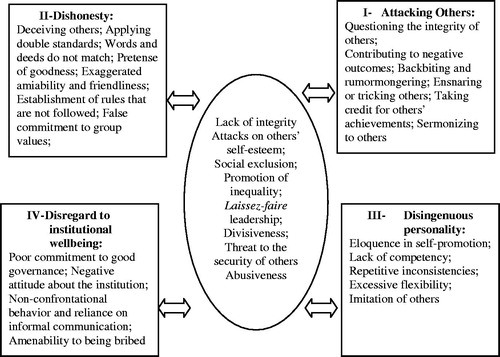

Proposition 2 posited that some similarities could be found between toxic and hypocritical behaviors. The thematic analysis of email responses supported the proposition as distinctive characteristics of organizational hypocrisy were revealed and grouped in four themes: dishonesty, attacking others, disregard to institutional wellbeing, and disingenuous personality. Each hypocritical characteristic within the four groups was referenced in the email responses with an average frequency of 74 times; the highest recorded occurrence of a theme is 120 and the lowest is 31. As frequency is considered an indication of popularity, it can be said that the most popular examples of hypocritical behaviors cited by the respondents are listed in under the title of each group of hypocritical behaviors.

FIGURE 2 Similarities between hypocritical and toxic behaviors. Note. The hypocritical characteristics within each box are sequentially ordered from the most to least frequently mentioned in the email responses. The oval shape represents the shared themes between hypocrisy and toxicity based on Pelletier’s typology (Citation2010).

shows eight similarities that intersect between the revealed hypocritical characteristics and toxic behaviors (Column B). The intersected similarities are overlapping toxic themes that are discussed in leadership literature and described as harmful, obnoxious, and destructive. The results show that similar to toxic leadership, a noxious workplace environment can only flourish when academic managers behave in a hypocritical manner and their colleagues are complacent or tolerate, participate, and accept the duplicity (Earp, Citation2016) notwithstanding their personal intentions, interests, or motives (Padilla et al., Citation2007). A single person (the hypocritical manager) cannot transform the workplace into a toxic environment (Crisp & Cowton, Citation1994). However, a comprehensive examination of this topic would require future research projects to further explore the correlations between hypocrisy and toxicity and their impact on organizational environment. Since the purpose of this study is to highlight similarities between hypocrisy and toxicity, the toxic themes (Column B) will not be extensively discussed since leadership literature discusses them extensively (Yaghi, Citation2019). Instead, the four groups of hypocritical characteristics are discussed below.

The analyses summarized in indicate that hypocritical leaders are dishonest, attack others, have no regard for institutional governance and wellbeing, and have disingenuous personality. The example behaviors cited under each one of the aforementioned groups overlap making it therefore necessary for future researchers to further examine each one of the reported traits to better understand, define, and distinguish them from others. None of the reported hypocritical characteristics seems to be overtly hostile or aggressive. This conclusion supports the early discussions in this paper and confirms the present study’s underlying claim that hypocrisy reflects the soft side of toxicity. The following section briefly discusses the four groups of hypocritical behaviors:

Dishonesty

Dishonest academic managers lack integrity, and deceive colleagues and subordinates by applying double standards allowing thus a palpable distance between their words and deeds (Palanski & Yammarino, Citation2007; Thoms, Citation2008). Academic managers may apply different rules to deal with two similar or even identical situations. A social science college dean states, “the provost says we cannot hire research assistants without going through the centralized system of HRM [human resource management] and also get his advanced approval, but he allows the dean of the college of business to hire research assistants directly without any of these requirements.” Academic managers deceive people by showing goodness. A program director elaborates, “she [department chair] pretends to be a good person who wishes good to others but in reality she is wicked, selfish, and hypocrite.” Pretense can be harmful or harmless depending on its intentions and outcomes. Feigning is harmless when it is personal that does not affect others, such as pretending to have dark hair, or when it does not produce bad outcomes, such as pretending to speak a foreign language. However, it is harmful when it is coupled with deception aiming to unrightfully gain benefits. Managers project an exaggerated friendliness that transcends the demands of civility. Such excessive amiability generally aims to conceal wrongdoing or malicious actions. They tend to behave agreeable when they convey information that is untrue or when they perform actions that are wrong. According to a dean, “when we are in a meeting, the provost behaves extremely nice, polite, and cooperative, but she is not nice at all when she meets individually with college deans.”

Some academic managers establish rules and then act against those very rules, thus evidencing toxic conduct (Alicke, Gordon, & Rose, Citation2013; Rohr, Citation1996, p. 554). A college dean describes a provost’s behavior by saying, “she made a decision that all administrative meetings should be scheduled on Thursdays, then she scheduled a meeting with deans a Monday then on a Wednesday.” Therefore, like toxic leaders, hypocritical managers establish rules that they are themselves willing to break; yet, they punish subordinates who challenge the instituted regulations (Atkinson & Butcher, Citation2003; Lipman-Blumen, Citation2005; Walton, Citation2007). By punishing violators, hypocritical managers aim to portray an image of an honest group member who cares about the shared-values and norms within the group. This type of rational thinking prioritizes self-interests over other concerns (Brunsson, Citation1986; Yaghi & Antwi-Boateng, Citation2017). Departmental benefits hence seem to define the morality of such managers and tend to direct the extent to which a behavior is considered ethical.

Attacking Others

The relationship between leaders and their followers is certainly influenced by the value they accord to life and people. When a leader’s negative assessment of self and others is conjoined with incompetency or a lack of self-worth, questioning the integrity and intentions of others is a natural outcome. This tendency to suspect others can be damaging to the trust that ought to prevail in the university as a workplace. An associate dean posits, “the Provost accuses colleges of depriving the university administration the support it needs to carry out reforms… even when we go out of our way to support his initiatives, he continues to question our intentions.” The survey answers suggest that hypocritical managers contribute to negative outcomes by causing damage to the reputations of others (e.g., through actions such as backbiting or lying), depriving professors of legitimate benefits (e.g., by favoring others), and putting people down (e.g., by breaching others). One response states, “they [dean and provost] are hypocrites … they claim they support me but their continuous lying makes me sick and want to resign … they tie my hands yet claim to empower department chairs … the college dean is lousy and the provost is just a crock.” Moreover, hypocritical managers seem to become self-appointed teachers, clerics, and moral agents; they use the rhetoric of virtue and commitment to community values as a means of deception. Their tendency to over-preach is, in fact, the conduct that alerts others around them to notice the discrepancies between their rhetoric of morality and their deeds. A department chair notes that “he [the dean] works in the university for ten years and he never stops preaching people about the importance of honesty, yet he literally instructed me to fabricate a report that he needed to send to the provost.” Many hypocritical managers prefer backbiting to confrontation when they want to build a circle of trust around themselves. Badmouthing generates a closed environment that allows people to reveal their worst thoughts and show the most negative attitudes against others (Kusy & Holloway, Citation2009; Yaghi & Antwi‐Boateng, Citation2017). In addition, the vice of spreading rumors isolates some individuals and brings others closer. It is thus divisive and creates infighting fractions within an organizational unit. Backbiting often occurs behind closed doors but the parties engaged in this conduct do not necessarily trust one another because rumormongering can also serve as a means to display one’s likability. A professor explains, “my department chair tells me a lot of bad things almost about everybody in the department, I am sure he also talks bad about me with others as he talks about them with me.” In conjunction with backbiting, managers claim to something that others have produced. Some respondents report statements such as, “he boldly claimed he did it when he only stole it,” “she told me that my achievement is owned by the college because I work for the college,” “she removed my name from the first page of the self-study and wrote her name.”

Disregard for Institutional Wellbeing

Hypocritical managers deceive others by perpetrating duplicity and holding negative attitude about the institution (Alicke et al., Citation2013). Managers intend to conceal a dominant malicious objective by pretending to be loyal to the institution while they covertly and overtly work against it and its governance. Hypocritical managers are described to lack transparency, accountability, efficiency, and responsiveness—values that distinguish a beneficial system. In particular, they exhibit negative attitudes regarding core institutional systems, such as human resource management and policies, promotion procedures, decision-making, strategic planning, reporting systems, as well as policies pertaining to teaching loads, research, and curricular reform. A college dean says, “I know the provost likes to talk about accountability but really he never cared about that.” An assistant dean says, “the dean does not care about corruption and favoritism in his administration yet he brags about implementing best practices.” One department chair writes, “although my colleague [another department chair] always criticizes the bureaucracy of this university and argues it aims to kill our creativity, he fiercely fights to be renewed as a chair for his department relying on the same bureaucracy that he criticizes.” Some professors indicate that their superiors are open to accepting small inducements to do their jobs. Superiors may modify hostile conduct toward particular subordinates if they are offered simple objects such as pens or picture frames by the latter. A professor recounts that “my department chair constantly assigns my colleague light teaching load and this colleague brings home-made sandwich every Monday and Wednesday and spends an hour eating and chatting with the department chair.” Another professor tenders a gruesome description of the low-level bribes accepted by his department chair: “I applied for a conference and got rejected, I bribed the chair a picture frame as a gift and next he simply approved my conference participation.” These statements seem to confirm that hypocritical managers value bribes not because of their material value but because bribes symbolize perceived loyalty, support, and submission. Most reported bribes were as trivial as a pen, necktie, sandwich, coffee, donuts, or confectionery.

Disingenuous Personality

Respondents indicate that hypocritical superiors lack job-related competency but conceal their ineptitude by abusing others. A professor reports bitterly that “my department chair lacks the ability to manage a team but he never admits that.” A program manager explains, “the assistant dean for research is an assistant professor who has never published a single research since he graduated from the university twenty years ago, yet as a leader of research teams and activities in the college he covers up his lack of research knowledge by making all sorts of lies and gimmicks.” Some respondents noted that the colleagues or superiors they identify as hypocritical tend to be exceptionally flexible with workplace norms. Perhaps such tractability that loosens the coupling between established rules and actual practices represents another pragmatic strategy adopted by hypocritical managers to cope with workplace uncertainties (Weick, Citation1976). It can also reflect a form of laissez-faire leadership behavior as such adaptable managers also tend to be disengaged and show little concern regarding their units or the people working under them. As has been observed in toxic leaders (see, O’Connell & Kowal, Citation2002), hypocritical managers seem to persuasively articulate their values, interests, and achievements. Perhaps such expressiveness is an effective instrument for the concealment of misconducts because people tend not to check the authenticity of information when they are otherwise impressed by a personality. A department chair describes her superior as, “I have not seen more eloquent person as he is … he makes you enjoy the stories he tells and forget the reason the story is being told.” As discussed earlier, hypocritical academic managers are not confrontational and it is therefore efficient for them to conduct informal communication behind closed doors. A professor states about her department chair “I wish if he sends me an email instead of verbally telling me things.” Disingenuity appears when copying others and mimicking them which suggests incompetence, absence of self-confidence, or lack of originality. A professor notes that “he [department chair] does not have his own personality.” An associate dean details that “my dean parrots the provost and when the provost changes his position on something, the dean simply switches endlessly.” If someone occasionally behaves erratically, people would not notice or probably would not describe such an inconsistency of conduct as hypocritical behavior. Habitual inconsistent and contradictory project conducts the impression of a difficult personality and suggests immorality and categorizes the person as someone who is unprincipled, untrustworthy, hostile, unprofessional, or unfathomable. Several survey responses indicate that hypocritical academic managers habitually lie, pretend, act divisively, and evince numerous other duplicitous behaviors. A professor describes her superior as, “my program director keeps saying things and doing something else … she cannot stop doing this.” A dean says, “my colleagues are typical hypocrites who cannot stop backbiting and lying… they keep doing this.”

CONCLUSION

This exploratory study aimed to identify hypocritical organizational behavior perceived in academic managers of several public universities in Arab countries. A list of professors and academic managers was compiled, and responses were collected through a survey conducted via an email message comprising several open-ended questions. All received answers were thematically analyzed and four distinctive groups of hypocritical behavior characteristics were revealed from the data; dishonesty, attacking others, disregard to institutional wellbeing, and disingenuous personality (see ). The analyses also highlight similarities between hypocritical organizational conduct and several previously reported characteristics of toxic leadership behaviors; lacking of integrity, attacking others, social exclusion, inequality, laissez-faire, divisiveness, threat to the security of others, and abusiveness.

All of the identified hypocritical characteristics reflect toxicity, albeit mostly its soft facets. The findings of this study, therefore, imply that hypocrisy takes many forms in universities and can be exhibited in discrete ways. The extant literature on leadership has established that toxicity can be measured by its outcomes: the adverse, unjust, wrong, evil, or damaging results that may be experienced by workers because of malicious or immoral managerial conduct (Yavaş, Citation2016). If the behaviors evinced by a manager do not injure another person, they may not be perceived as toxic. Put differently, hypocrisy and toxicity are similar in the sense that an individual’s conduct can be considered toxic; inappropriate, wrong, or bad when others are hurt by it. depicts that each identified hypocritical characteristic encompasses some aspect of toxicity within it.

From the standpoint of governance and administration, the present study reports significant results regarding the destructive nature of hypocrisy and elucidates the manner in which hypocritical managers subvert the governance systems of their institutions. These findings suggest that hypocritical academic managers cannot be trusted to function in constructive roles to implement organizational reforms or development plans. Researchers will be needed to further examine the impact of hypocrisy on the success of the curricular, programmatic, strategic, and administrative development of universities. Inability to trust managers in publicly-funded university implies that not only these civil servants do not produce value that the society and stakeholders (e.g., partners and students) need, but it also threatens the core issue of publicness of their institutions (Broucker, De Wit, & Verhoeven, Citation2018).

Contrary to the stereotypical views that toxic behavior is embodied by meanness, rudeness, or brutality, the present study discovers that toxic academic managers can be friendly and courteous. The hypocritical behavior of faculty members can therefore constitute only one facet of a broader toxic phenomenon that prevails in higher educational institutions. Hypocritical practices are toxic practices that reduce credibility and legitimacy of public universities (Bryson, Crosby, & Bloomberg, Citation2014; Hartley, Alford, Knies, & Douglas, Citation2017). While all universities bear responsibilities to educate students and provide relevant services such as research and training, publicly-funded universities represent the authority of government thus they are expected to maintain morality, integrity, and good governance which all are integral parts to the character of government and its public institutions (Bryson et al., Citation2014). The findings suggest that practicing hypocrisy does not help academic managers to realize the publicness of their universities and the moral obligations of the managers towards their subordinates, colleagues, and society (Merritt, Citation2019). Future research should focus on the linkages between organizational hypocrisy and its impact on diminishing the value that public universities should produce. For practitioners and as Merritt (Citation2019) implies, public universities should invest in building institutional systems that enhance the moral obligations of academic managers and their responsibility toward internal and external stakeholders. Reforming universities should go beyond the emphasis on efficiency (e.g., budget management) and effectiveness (e.g., ranking and competitiveness), there is need to focus on the role of publicness in maintaining legitimacy and trust in public universities as the guarantors of public interest. Because hypocrisy flourishes in uncertain environment (Effron, Lucas, & O’Connor, Citation2015), future research should examine factors contributing to the workplace environment, investigate the degrees of influence these factors exert on hypocritical behaviors, and assess the extent to which such soft toxic behaviors can, in turn, alter the workplace environment and influence governance systems within each university as well as in higher education as whole.

The current research initiative has generated original knowledge about hypocritical characteristics and leadership behavior. However, a few limitations must be acknowledged and maybe avoided by future researchers. Principally, the manner of sample selection may have influenced the nature of the responses. Prospective studies could employ the random sampling technique to validate the reported hypocritical characteristics. A questionnaire could also be developed on the basis of the 22 characteristics reported in this study. Finally, a comparative study may be able to produce valuable insights about the differences in the conduct of hypocritical academic managers working in Arab and non-Arab universities.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the faculty members who responded to our emails and provided their valuable feedback.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Al Addasi, M. (2001). The ethics of teaching in the Islamic culture and the extent of teachers’ commitment to morality (Doctoral Dissertation). Al-Quds University, Palestine. (in Arabic)

- Al Hafyan, M. (2009). Role of the University of Shindi in making the local social change (Doctoral Dissertation). University of Shindi, Algeria (in Arabic).

- Alicke, M., Gordon, E., & Rose, D. (2013). Hypocrisy: What counts? Philosophical Psychology, 26(5), 673–701. doi:10.1080/09515089.2012.677397

- Al-Kindi, I. A., & Bailie, H. T. (2015). Values and managerial practices in a traditional society. International Journal of Commerce and Management, 25(2), 138–156. doi:10.1108/IJCoMA-09-2013-0086

- Alzahrani, N. (2019). Impact of organizational justice in reducing work stress (Doctoral Dissertation). University of Nayif, Saudi Arabia (in Arabic).

- Ashforth, B. (1994). Petty tyranny in organizations. Human Relations, 47(7), 755–788. doi:10.1177/001872679404700701

- Atkinson, S., & Butcher, D. (2003). Trust in managerial relationships. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 18(4), 282–304. doi:10.1108/02683940310473064

- Babbie, E. R. (2020). The practice of social research. Florence, KY: Cengage learning.

- Bozwagh, H. (2017). The role of public service ethics in reducing misconduct (Doctoral Dissertation). University of Mawlood Maameri, Tezi Ozo, Algeria (in Arabic).

- Broucker, B., De Wit, K., & Verhoeven, J. C. (2018). Higher education for public value: Taking the debate beyond New Public Management. Higher Education Research & Development, 37(2), 227–240.

- Brunsson, N. (1986). Organizing for inconsistencies: On organizational conflict, depression and hypocrisy as substitutes for action. Scandinavian Journal of Management Studies, 2(3–4), 165–185. doi:10.1016/0281-7527(86)90014-9

- Bryson, J. M., Crosby, B. C., & Bloomberg, L. (2014). Public value governance: Moving beyond traditional public administration and the new public management. Public Administration Review, 74(4), 445–456. doi:10.1111/puar.12238

- Chamberlain, L. J., & Hodson, R. (2010). Toxic work environments: What helps and what hurts. Sociological Perspectives, 53(4), 455–477. doi:10.1525/sop.2010.53.4.455

- Chowdhury, M. F. (2015). Coding, sorting and sifting of qualitative data analysis: Debates and discussion. Quality & Quantity, 49(3), 1135–1143. doi:10.1007/s11135-014-0039-2

- Crisp, R., & Cowton, C. (1994). Hypocrisy and moral seriousness. American Philosophical Quarterly, 31(4), 343–349.

- Dayyeh, I., & Skakiyya, I. (2018). Perspectives of students and faculty at Bethlehem University towards Plagiarism: Challenges and solutions. Bethlehem University Journal, 35, 91–111. (in Arabic). doi:10.13169/bethunivj.35.2018.0091

- Duthler, G., & Dhanesh, G. S. (2018). The role of corporate social responsibility (CSR) and internal CSR communication in predicting employee engagement: Perspectives from the United Arab Emirates (UAE). Public Relations Review, 44(4), 453–462. doi:10.1016/j.pubrev.2018.04.001

- Earp, B. D. (2016). Between moral relativism and moral hypocrisy: Reframing the debate on “FGM.” Kennedy Institute of Ethics Journal, 26(2), 105–144. doi:10.1353/ken.2016.0009

- Effron, D. A., Lucas, B. J., & O’Connor, K. (2015). Hypocrisy by association: When organizational membership increases condemnation for wrongdoing. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 130, 147–159. doi:10.1016/j.obhdp.2015.05.001

- Einarsen, S., Aasland, M. S., & Skogstad, A. (2007). Destructive leadership behaviour: A definition and conceptual model. The Leadership Quarterly, 18(3), 207–216. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2007.03.002

- Eshtawi, A. (2016). Hypocrites and hypocrisy, reading in the Holy Quran and Sunna (Doctoral Dissertation). Al Najah University, Palestine (in Arabic).

- Hale, W. J. (2012). Moral hypocrisy: Rethinking the construct (Master Thesis). The University of Texas at San Antonio, CA.

- Hartley, J., Alford, J., Knies, E., & Douglas, S. (2017). Towards an empirical research agenda for public value theory. Public Management Review, 19(5), 670–685. doi:10.1080/14719037.2016.1192166

- Herrera, L. (2007). Higher education in the Arab world. In J. Forest & P. Altbach (Eds.), International handbook of higher education (pp. 409–421). Dordrecht: Dordrecht Springer.

- Kusy, M., & Holloway, E. (2009). Toxic workplace!: Managing toxic personalities and their systems of power. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Lipman-Blumen, J. (2005). The allure of toxic leaders: Why we follow destructive bosses and corrupt politicians—and how we can survive them. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Mahmood, G. (2008). Assessing the cost of administrative and financial corruption. Journal of Future Studies, 4(1), 51–82. (in Arabic).

- Martin, P. Y., & Turner, B. A. (1986). Grounded theory and organizational research. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 22(2), 141–157. doi:10.1177/002188638602200207

- Merritt, C. C. (2019). What makes an organization public? Managers’ perceptions in the mental health and substance abuse treatment system. The American Review of Public Administration, 49(4), 411–424. doi:10.1177/0275074019829610

- Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., & Saldana, J. (2014). Fundamentals of qualitative data analysis. Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook (pp. 69–103). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

- Mohamed, M., & Baljit, M. (2018). Role of Iraqi universities to prepare ethical leadership to confront crises: Opinion of heads of departments. Al Dananeer Journal, 13(1), 431–458. (in Arabic).

- Moulton, S. (2009). Putting together the publicness puzzle: A framework for realized publicness. Public Administration Review, 69(5), 889–900. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6210.2009.02038.x

- Neves, P., & Story, J. (2015). Ethical leadership and reputation: Combined indirect effects on organizational deviance. Journal of Business Ethics, 127(1), 165–176. doi:10.1007/s10551-013-1997-3

- Nevicka, B., De Hoogh, A. H. B., Den Hartog, D. N., & Belschak, F. D. (2018). Narcissistic leaders and their victims: followers low on self-esteem and low on core self-evaluations suffer most. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 422. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00422

- Noori, N., & Anderson, P. (2013). Globalization, governance, and the diffusion of the American model of education: Accreditation agencies and American-style universities in the Middle East. International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society, 26(2), 159–172. doi:10.1007/s10767-013-9131-1

- O’Connell, D. C., & Kowal, S. (2002). Political eloquence. In V. Ottati (Eds.), The social psychology of politics (pp. 89–103). Boston, MA: Springer.

- Padilla, A., Hogan, R., & Kaiser, R. (2007). The toxic triangle: Destructive leaders, susceptible followers, and conducive environments. Leadership Quarterly, 18(3), 176–194. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2007.03.001

- Palanski, M., & Yammarino, F. (2007). Integrity and leadership: Clearing the conceptual confusion. European Management Journal, 25(3), 171–184. doi:10.1016/j.emj.2007.04.006

- Pelletier, K. (2010). Leader toxicity: An empirical investigation of toxic behavior and rhetoric. Leadership, 6(4), 373–389. doi:10.1177/1742715010379308

- Pope, K. (2015). Steps to strengthen ethics in organizations: Research findings, ethics placebos, and what works. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation : The Official Journal of the International Society for the Study of Dissociation (ISSD), 16(2), 139–152. doi:10.1080/15299732.2015.995021

- Rohr, J. (1996). An address. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 6(4), 547–558. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.jpart.a024326

- Sharma, L., & Singh, S. (2013). Characteristics of laissez-faire leadership style: A case study. CLEAR International Journal of Research in Commerce & Management, 4(3), 29–31.

- Shaw, J., Erickson, A., & Harvey, M. (2011). A method for measuring destructive leadership and identifying types of destructive leaders in organizations. The Leadership Quarterly, 22(4), 575–590. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2011.05.001

- Suyuti, R. (2017). The ethics of educators in Islam and the extent of its suitability for teaching (Doctoral Dissertation). Universitas Islam Negeri Maulana Malik Ibrahim, Indonesia.

- Taiwo, A. (2010). The influence of work environment on workers productivity: A case of selected oil and gas industry in Lagos. Nigeria. African Journal of Business Management, 4(3), 229–307.

- Tepper, B. (2000). Consequences of abusive supervision. Academy of Management Journal, 43(2), 178–190.

- Thoms, J. (2008). Ethical integrity in leadership and organizational moral culture. Leadership, 4(4), 419–442. doi:10.1177/1742715008095189

- Turner, D. (1990). Hypocrisy. Metaphilosophy, 21(3), 262–269. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9973.1990.tb00528.x

- Wahab, M., & Ismail, Y. (2019). Mas’uliyyah and Ihsan as high-performance work values in Islam. International Journal of Economics, Management and Accounting, 27(1), 187–212.

- Walton, M. (2007). Leadership toxicity–an inevitable affliction of organisations. Organisations and People, 14(1), 19–27. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/hypocrisy.

- Weick, K. (1976). Educational organizations as loosely coupled systems. Administrative Science Quarterly, 21(1), 1–19. doi:10.2307/2391875

- Xirasagar, S. (2008). Transformational, transactional among physician and laissez-faire leadership among physician executives. Journal of Health Organization and Management, 22(6), 599–613. doi:10.1108/14777260810916579

- Yaghi, A. (2016). Is it human resource policy to blame? Examining intention to quit among women managers in Arab middle eastern context. Gender in Management: An International Journal, 31(7), 479–495. doi:10.1108/GM-11-2015-0094

- Yaghi, A. (2017). Adaptive organizational leadership style: Contextualizing transformational leadership in a non-western country. International Journal of Public Leadership, 13(4), 243–259. doi:10.1108/IJPL-01-2017-0001

- Yaghi, M. (2019). Toxic leadership and the organizational commitment of senior-level corporate executives. Journal of Leadership, Accountability and Ethics, 16(4), 138–152. doi:10.33423/jlae.v16i4.2375

- Yaghi, A., & Aljaidi, N. (2014). Examining organizational commitment among national and expatriate employees in the private and public sectors in United Arab Emirates. International Journal of Public Administration, 37(12), 801–8011. doi:10.1080/01900692.2014.907314

- Yaghi, A., & Al-Jenaibi, B. (2018). Happiness, morality, rationality, and challenges in implementing smart government policy. Public Integrity, 20(3), 284–299. doi:10.1080/10999922.2017.1364947

- Yaghi, A., & Antwi-Boateng, O. (2017). Public policy issues and campaign strategies: Examining rationality and the role of social media in a legislative election within a Middle Eastern Context. Digest of Middle East Studies, 26(2), 398–421. doi:10.1111/dome.12118

- Yaghi, A., Morris, J., & Gibson, P. (2007). Identifying organizational culture. Dirasat Journal, 35(4), 871–884.

- Yaghi, A., & Yaghi, I. (2013). Human resource diversity in the United Arab Emirates: Empirical study. Education, Business and Society: Contemporary Middle Eastern Issues, 6(1), 15–30. doi:10.1108/17537981311314682

- Yaghi, I., & Yaghi, A. (2014). Quality of work life in the post-nationalization of human resources: Empirical examination of workforce emiratization in the United Arab Emirates. International Journal of Public Administration, 37(4), 224–236. doi:10.1080/01900692.2013.812112

- Yavaş, A. (2016). Sectoral differences in the perception of toxic leadership. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 229, 267–276. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2016.07.137

- Younus, T. S., Reyaz Ahmmad, D., Radrakrishnan, L., Wahba, H., & Al Bourini, F. (2019). The relationship between administrative hypocrisy and the organization disorder: Diagnostic approach. HexaTech, 2(1), 1–10. doi:10.18576/hexatech/020101

- Yukl, G. (1999). An evaluation of conceptual weaknesses in transformational and charismatic leadership theories. Leadership Quarterly, 10(2), 285–305. doi:10.1016/S1048-9843(99)00013-2