Abstract

Although the scholarly attention for the ethical leadership function in the public sector is increasing, empirical research into the importance of moral norms and values in governance and into what is expected of ethical leaders remains rare. The Dutch mayoralty provides an insightful case in point since a formal ethical leadership role has been attributed to the mayor and because job advertisements for the office are available, which, uniquely, enable tracing the use of the integrity concept. This article provides a quantitative longitudinal analysis of the integrity requirements placed on Dutch mayors in 349 vacancy text. The findings indicate that moral person expectations in particular feature prominently. But, contrary to expectations, the attention paid to integrity requirements for candidate mayors, both as moral persons and as ethical leaders, is found to decrease between 2008 and 2019. This finding may indicate that integrity has increasingly become a taken-for-granted value. In addition, a significant increase is observed in the focus on the role of the mayor in promoting integrity through proactive rather than reactive intervention. Although sanctioning violations remains at its core, the ethical leadership function, thus, seems to be moving towards the taking of preemptive measures.

Over the last decade, the integrity of government and the strengthening of the integrity culture in public administration has become more prominent in research as well as policy-making. In this line of research, traditionally, the focus lies on “integrity systems,” that is the “the policies, practices, and integrity institutions that are meant to contribute to the rectitude [of government]” (Huberts, Anechiarico, & Six, Citation2008). Increasingly, though, the focus is shifting towards the role that formal and informal leaders have in fostering normatively appropriate conduct through personal actions, interpersonal relationships, and the promotion of such conduct, or what is commonly referred to as “ethical leadership” (Brown & Treviño, Citation2006). This is because the contributions of individuals, as part of the broader integrity system, are increasingly seen to be a crucial part of effective moral management, also in the public sector (Lawton & Páez, Citation2015; Moore et al., Citation2019; Zhu, Zheng, He, Wang, & Zhang, Citation2019). Whereas perceptions of ethical leadership are known to vary between the public and private sectors, ethical leadership has remained underexplored in the public realm as the field continues to be dominated by the study of business ethics (Brown & Treviño, Citation2006; Heres, Lasthuizen, & Webb, Citation2019; Heres & Lasthuizen, Citation2012; Karsten, Citation2019a).

To the extent that studies on ethical leadership in public administration are available, ethical leadership is most often conceptualized as a leadership trait or as behavior, that is the actual demonstration of normally appropriate conduct and the efforts to promote such conduct to followers (Brown & Treviño, Citation2006; Hernandez, Eberly, Avolio, & Johnson, Citation2011). Less often, ethical leadership is conceptualized as a leadership function, or in other words: a particular responsibility or task to promote normatively appropriate conduct. The reasons are at least twofold. First, leadership functions, including ethical leadership, nowadays are more dispersed or “shared” (Palmer, Citation2009; Zhu, Liao, Yam, & Johnson, Citation2018). Most often, there is not one individual or specific body that carries the responsibility for the integrity of an organization. Consequently, to the extent that it is possible, it is often difficult to identify who is, or should be, the ethical leader in an organization and who carries responsibility for ethical management. Second, the ethical leadership function in the public sector is rarely formalized as a legal responsibility; the ethical leadership role often remains an informal one (Karsten, Citation2019a). In public administration, ethics committees and integrity officers may form an exception since they sometimes play an important formal role in integrity systems (Huberts et al., Citation2008). The difficulty of ethics committees, though, is that they form a collective assessment, which creates a “problem of the many hands” (Thompson, Citation1980): it renders ethical leadership responsibilities very difficult to attribute to individuals. Integrity officers, in turn, most often operate under the responsivity of a political superior, which implies that they do not carry the final responsibility for the ethical leadership function. Because of this situation, ethical leadership responsibilities in public organizations are hard to pin down and it is difficult to identify what is expected of ethical leaders.

The Dutch mayor forms an insightful exception for two reasons. First, as of February 2016, the Dutch mayor carries an explicit legal responsibility for the strengthening of the integrity of local government since Section 170 paragraph 2 of the Dutch Municipalities Act reads: “The mayor advances the administrative integrity of the municipality.” Neither the legal provision nor its explanatory memorandum provides a further elaboration of the meaning of the term “advancing” or of how the concept of “administrative integrity” is to be understood, which means that the legal implications remain very unclear (Versteden, Citation2014). But, the explanatory memorandum does indicate that Dutch mayors are obliged to act against any suspected integrity violations by councilors or executive politicians. This means that the Dutch mayoralty presents a unique case of formalized ethical leadership responsibility in the hands of a political figure. In addition, Dutch mayors are not directly elected but are selected by the municipal council of representatives through a public vacancy. At the start of the selection procedure, the council collectively writes a text that describes the “job requirements to be met by the person to be appointed as mayor” (Section 61, paragraph 2 Municipalities Act). These job descriptions have the same function as a job vacancy text in other professions but also play a formal role in the evaluation of the performance of mayors once they are in office (Karsten, Citation2019b). This is why they are a valuable source of information about the integrity requirements placed on Dutch mayors.

Of course, these “profile descriptions” are only one part of the reality: not all actual requirements are put on article (Harper, Citation2012). In the job interviews that a delegation of the council conducts with mayoral candidates, for example, councilors might express addition or different integrity requirements. The extent to which they do so remains unclear because, by law, these interviews are secret. It is punishable by law to divulge any information about the specifics of the selection process. This inaccessibility of further information is all the more reason why descriptions are a valuable source when analyzing the mayoralty because they offer a unique insight into what, if anything, is expected from officeholders in terms of ethical leadership (Den Hartog, Caley, & Dewe, Citation2007; Karsten, Citation2019a, Citation2019b). And, research into vacancy texts has become an established research strategy in this field (Bee & Hie, Citation2015; Harper, Citation2012; Jørgensen & Rutgers, Citation2014; Tan & Laswad, Citation2018).

In this article, an analysis is provided of the integrity requirements placed on Dutch mayors in vacancy texts published between January 2008 and April 2019. This analysis contributes to the yet underdeveloped literature on ethical leadership in the public sector by fostering the crucial understanding of what ethical leadership entails through providing an analysis of Dutch councilors’ integrity requirements (see also Heres et al., Citation2019). In addition, an analysis is provided of whether and how these requirements change after the introduction of the 2016 integrity law. This longitudinal approach enables answering the questions of whether and how perceptions of ethical leadership change over time, which is important since conceptions of ethical leadership are dependent on context (see, e.g. Huberts, Citation2018; Zhu et al., Citation2019). In this way, the analysis carries a broader relevance than the Dutch mayoralty alone and functions as a stepping stone in the wider research agenda on ethical leadership in the public sector (Heres et al., Citation2019), where an “empirical turn” is strongly needed (Huberts, Citation2018). Two questions are at the core of the study, namely:

What integrity requirements do councilors, according to vacancy texts, place on mayors?

To what extent and how do the integrity requirements placed on mayors change after the introduction of the 2016 local integrity act?

The answer to the first question describes what is expected from Dutch mayors on the matter. This analysis aims to empirically identify the integrity requirements placed on mayors, which carries both academic and policy relevance since it contributes to the crucial understanding of what integrity and ethical leadership are taken to mean in practice (Huberts, Citation2018; Versteden, Citation2014).

The second question analyses whether a change in the integrity requirements over time can be observed. Here, a causal link between the introduction of the 2016 integrity law and changing requirements is deliberately not assumed. This is because the new responsibility ties in with several other legal obligations that the Dutch mayor had already before 2016. These include overseeing the quality of the local authority’s decision-making (Section 170 Municipalities Act) and ensuring the legality of decisions made (Section 273 Municipalities Act). These responsibilities resonate with the longstanding conviction that Dutch mayors should be “guardians of local democracy” (Karsten & Hendriks, Citation2017). As such, the responsibility is not new and has only been explicated. One could even say that its introduction was a matter of codification, where the existing practice was put into law. After all, the government was “keen to emphasize […] that, as regards the mayor's duty of care for the administrative integrity of the municipality, it does not intend to make a material change. In current practice, the mayor already fulfills this role” (Parliamentary Papers, 2015–2016, 33691 No. E). However, it cannot be ruled out that the new law has influenced the expectations that councilors have of their mayors since the explicit responsibility was still new and may also have made councilors more aware of this mayoral duty. However, such causal effects go beyond the scope of this article. It nevertheless remains relevant to determine whether and how the integrity requirements that city councils set for candidate mayors changed around the time of the change in the law. After all, this provides relevant insight into how perceptions of integrity change over time empirically (Huberts, Citation2018).

Theoretical foundation

Because norms and values are context-dependent, there is no general agreement on the definition of “integrity” (Huberts, Citation2018), let alone “administrative integrity.” Further, neither the Dutch 2016 integrity law nor its explanatory memorandum provides an explicit definition. To the extent that a perspective on integrity can accurately be derived from the explanatory memorandum, the legislator sees integrity mainly as the type of behavior where a person acts in accordance with moral values and norms since the text lays emphasis on compliance with and violation of “integrity rules.” This understanding of “integrity” is mirrored by the ministry’s 2016 definition of “acting in accordance with generally accepted norms and values.” Huberts (Citation2018) identifies this as one of eight well-established conceptions of integrity.

For the current study, we take a heuristic approach to the integrity concept that identifies through content analysis how councilors use the notion. In the below analysis of integrity requirements, a twofold distinction is applied between two aspects of ethical leadership that have been theorized, that is the distinction between being a “moral person” and acting as a “moral manager” (Trevino, Hartman, & Brown, Citation2000; Zhu et al., Citation2019). Whereas the former is about leaders acting in a normatively appropriate way themselves, the latter is about “the demonstration of normatively appropriate conduct through personal actions and interpersonal relationships, and the promotion of such conduct to followers through two-way communication, reinforcement, and decision-making” (Brown & Treviño, Citation2006). Whereas a virtuous leader is a leader who behaves in an ethical manner as a moral person, an ethical leader is someone who is actively committed to promoting integrity among others by way of being a moral manager. Both aspects of ethical leadership can be expected to be of great importance to the Dutch mayoralty since mayors are strongly expected to behave with integrity and also find “being a moral person” of utmost relevance to being an officeholder themselves. In addition, mayors are confronted with strong moral manager expectations, not only by the law (Cohen, Citation2018; Karsten, Citation2019a, Citation2019b).

Within the main category of the “moral person,” there are three ways in which the word “integrity” can be used in profile descriptions. The first option is that councilors copy the definition of “integrity” as provided by the ministry, which reads: “The mayor always acts unambiguously and transparently in accordance with generally accepted norms and values. He has a well-developed moral compass” (Ministry of the Interior and Kingdom Relations, Citation2016). All profile descriptions that have adopted this definition or have opted for a wording that closely resembles it, have been placed in this subcategory. A second possibility is that profiles contain a definition that is different from that of the ministry, or that integrity requirements are referred to that substantially differ from that definition. Consider descriptions such as: “The council and the executive board attach great importance to integrity. This implies: treating each other with respect, respect for the rule of law and the constitutional arrangements of local government constitutional state, and respectful treatment of citizens” (Municipality of Sluis, Citation2017). Such self-developed definitions form the second subcategory. A third possibility is that the concept of integrity is included in the text, but is not defined in any way. This selection includes all profile descriptions that demand that the candidate acts with integrity but do not further elaborate on what this implies.

Within the main category of “ethical leadership,” drawing on Brown and Treviño (Citation2006) and Heres (Citation2014), three different types of behavior are distinguished between: (a) demonstrating exemplary behavior to promote integrity, (b) proactive action to prevent (suspected) integrity violations, and (c) assertive action against others as soon as a (suspected) violation of integrity has arisen. Under (a), ethical leadership is a set of behaviors, decision-making, and character traits of a leader who, through this behavior, encourages others to act similarly – the leader sets an example (Heres, Citation2014; Mayer, Kuenzi, Greenbaum, Bardes, & Salvador, Citation2009). Under (b) ethical leadership is about intervening or acting to prevent amoral behavior and integrity problems within the organization by establishing incentives and through communication (Trevino et al., Citation2000; Zhu et al., Citation2019). And, under (c), it is about retrospective intervention or action to address and rectify amoral behavior and integrity problems through sanctions (Trevino et al., Citation2000; Zhu et al., Citation2019).

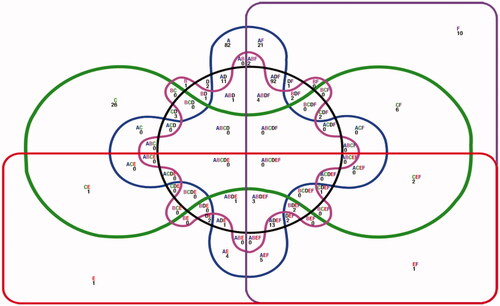

In this way, one arrives at an analytical framework for the use of the concept of integrity in profile descriptions with two main categories that each have three subcategories ().

TABLE 1. Analytic framework for the use of the integrity concept in profile descriptions.

Methodology

Our study first identified all mayors that were appointed in the Netherlands between 01-01-2008 and 30-04-2019 and then determined whether the vacancy text had been formalized within the period of validity. In this way, 402 valid profile descriptions were identified. Then, the actual texts were uncovered via the internet and through contact with municipal administrations. In this way, 349 profile descriptions from 340 municipalities were collected: 228 from the 2008 to 2016 period (86% of all 266 profiles from this period) and 121 (89% of the 136) from the 2016 to 2019 period. Thus, in total, 87% of the descriptions was analyzed. The remaining 53 texts could not be retrieved or were not suitable for digital analysis.

Next, axial coding was used to code the vacancy texts according to the analytical framework. First, the profile descriptions were systematically analyzed on the basis of keywords from each of the six subcategories, as derived from the literature (Brown & Treviño, Citation2006; Khaouja, Mezzour, Carley, & Kassou, Citation2019; Zhu et al., Citation2019), and their synonyms. These were later complemented with terms from profiles that also related to the concept of integrity but did not feature in the original selection. Thus, an iterative process was used in which the eventual analytic framework was partly fed by the data. All texts were then analyzed individually by, depending on the file type (.doc(x) or .pdf), running the key terms and synonyms through the search functions within Microsoft Word and Microsoft Edge. Subsequently, all profile descriptions were checked for text sections in which the key words did not appear explicitly, but which nevertheless related to integrity. All profile descriptions were manually coded in full for this exercise.

All profile descriptions were then assigned a score of 0 or 1 per profile for each variable in correspondence to the absence or presence of requirements that fall within the six subcategories. The unit of analysis, thus, is the vacancy text. The fact that a requirement can occur in a single vacancy text more than once was ignored since the relative weight of a requirement within a profile description is less relevant in the light of the research question than its absence or presence. In addition, the intention was not to give unequal weights to municipalities. All profile descriptions were then re-coded by the other author until both authors finally agreed on all codes. This reinforces the reliability of the analysis.

Next, descriptive statistics were used to analyze the results and to compare periods. To answer the second research question, profile descriptions from two periods were compared: the period from 01-01-2008 to 31-12-2015 and the period from 01-02-2016 to 30-04-2019. This demarcation was chosen because Section 170, paragraph 2 of the Municipalities Act came into effect as of 1 February 2016 and around the same time a revised guide for drawing up profile description was published by the ministry. Levene’s tests were used to assess the equality of variances of the two groups. And, for their comparison, parametric statistical t-tests were performed. Significant differences by municipality size were not tested for since existing research shows that these are not to be expected as regards integrity (Karsten, Citation2019b).

Results

This section discusses the findings. First, the extent to which job vacancy texts for the Dutch mayoralty contain each of the six integrity requirements is discussed. Second, the two time periods are compared. Third, an analysis is provided of whether particular combinations of integrity requirements have become more prominent over time.

A moral person more than an ethical leader

This subsection describes and compares the moral person and ethical leadership requirements as they are posed on Dutch mayors in the full research period.

The results of the analysis, as depicted in , indicate that integrity requirements feature prominently in job vacancies for the Dutch mayoralty. Out of 349, 306 job vacancy texts contain one or more integrity requirements (87.7%), and only 43 (12.3%) pay no attention to integrity at all. With an 87.7% score on integrity requirements, as compared to other positions, the Dutch mayoralty scores relatively high (cf., e.g. Jørgensen & Rutgers, Citation2014; Bee & Hie, Citation2015; Roy, Citation2017; Tsahuridu & Perryer, Citation2002 ). This observation does not come as a surprise given the democratic guardianship role that Dutch mayors have (Karsten & Hendriks, Citation2017). Municipal councilors, thus, place great value on integrity when selecting and evaluating their mayor. The fact that around one in eight councils does not include any integrity requirements in their job advert might suggest that they value integrity less. This conclusion, however, does not necessarily hold. This is because focus group discussions indicate that some councils do not include a particular requirement in a job advert when it is taken for granted (Karsten, Citation2019b). Thus, councilors may have left integrity requirements out of the texts since they expect all candidates to be integritous (Jørgensen & Rutgers, Citation2014). Given the formal role of profile descriptions in the selection of candidates and the evaluation of officeholders, this strategy is unexpected since it makes it more difficult to judge an incumbent mayor by standards of personal integrity and moral management.

TABLE 2. Integrity requirements placed on Dutch mayors, 2008–2019.

Out of the two main categories, the “moral person” evidently seems to be the more important one. 287 texts, or 82.2%, indicate that a mayor should act with integrity and, thus, should be a moral person. Ethical leadership is expected less from mayors, but such requirements still feature in 198, or 56,7%, of the texts, which means that the majority of councils has explicit moral-management expectations of their future mayor.

As regards what it means to be a moral person and to act with integrity, 68,8% of councils follow the definition as provided by the national ministry. To repeat, this reads that the mayor always acts unambiguously and transparently in accordance with generally accepted norms and values and that he has a well-developed moral compass. Less than 5% of the councils develop their own definition of what integrity entails. Given the fact that norms and values are context-dependent and the fact that there may be a need for customization according to local preferences, this may come as a surprise. At the same time, this finding ties in with Jans’ (Citation2015) observation that Dutch municipalities rarely make full use of the opportunities to develop tailored policies. In addition, since integrity is such an ambiguous concept, it may come as a surprise that 62 vacancy text, or 17.8%, demand their future mayor to act with integrity but refrain from providing any further conceptualization, leaving its interpretation to the reader. Moreover, between 2016 and 2019 this percentage increases to 24.8%. This finding carries profound policy relevance and might encourage municipal councilors to reflect more on what “integrity” means.

Out of the 349 vacancy texts that have been analyzed, 198 require their future mayor to act as an ethical leader, which amounts to 56.7%. Within the broader ethical-leadership requirements, reactive intervention is seen to be the most important since 171, or 49.0%, of the job advertisements include that they expect candidates to act against (expected) integrity violations. Only a slightly lower percentage of profile descriptions, 41.5% to be precise, indicates that the mayor should set an example in integrity by acting in accordance with the accepted norms and values, propagating them, and thereby encouraging others to act similarly. The taking of proactive measures by establishing virtuous-behavior incentives and through communication is taken to be of less importance since such requirements feature in only 11.5% of profile descriptions.

To the extent that it is required from candidate mayors in the Dutch context, ethical leadership and advancing the administrative integrity of a municipality are thus understood mainly in terms of speaking up against others who have committed possible integrity violations and by setting an inspirational example. Setting the integrity stage and improving the conditions for an ethical local government in a more proactive role are translated into explicit expectations less often.

Changing Integrity requirements over time

In the light of the increasing attention for integrity and integrity policies in Western democracies, including the Netherlands, it is somewhat of a surprise to find that the focus on integrity in job vacancy texts for the Dutch mayoralty diminishes during the 2008–2019 period. Levene’s tests show equality of variances between periods 1 and 2 for all six variables (p < .05) ().

TABLE 3. Levene’s tests for equality of variances between period 1 and period 2 (p<.05).

In period 1, that is between 2008 and 2015, 9.6% of the profile descriptions did not pay attention to integrity at all. In period 2, that is 2008–2019, this percentage increased to 18.2% (T = −2.4482, p=.015). This difference is caused by three significant changes.

First, a significant increase can be observed in the number of profiles that do not include aspects of the “ethical person” (T= −2.308, p=.022). One possible explanation for this change is that the integrity of mayors may be taken for granted more and more (see also Jørgensen & Rutgers, Citation2014). As discussed, given the formal role of the profile description in the selection of mayors and the evaluation of their performance, this strategy is unexpected, but it does tie in with what we know from focus group discussions on the matter (Karsten, Citation2019b).

Second, a significant decrease can be observed in the percentage of profile descriptions that require mayoral candidates to set an integrity example. Moreover, the significance level is high here (T = 2.8798, p = .0042). This decline is a striking finding since both the old and new guidelines for composing a profile description explicitly state that the mayor has an exemplary role in the field of integrity. However, the wording on this point is slightly different in the 2016 guidelines as compared to the 2008 version, which may have motivated councilors to opt for a different phrasing that is less explicit on the matter or to drop the requirement altogether.

Third, between and 2008–2015 and 2016–2019, a significant increase is observed in the percentage of vacancy texts that do not include any ethical leadership requirements (T = −1.9832, p = 0.048). Again, this finding does not fit very well with the observation that the societal and political-administrative attention for the integrity of local government has increased. One explanation could be that the introduction of the 2016 integrity law has reduced the necessity of including such requirements explicitly because since then it is an undisputable legal responsibility of the Dutch mayor anyway.

In contrast, and more in line with the expectations, a significant increase was found in integrity requirements that demand a mayor proactively strengthens the local integrity culture by establishing incentives and through communication. This includes profile descriptions that ask future mayors to act as sparring partners and coaches for both municipal councilors and political-executives. This approach to integrity management remains of secondary importance in profile descriptions but has nevertheless become more important around the same time that “advancing the local administrative integrity” became a legal task of Dutch mayors. This shift is also in line with the text of the 2016 national guidelines, which states that mayors are expected to actively promote integrity awareness.

Combinations of requirements over time

In addition to identifying significant changes in the occurrence of individual integrity requirements between 2008 and 2015 and 2016 and 2019, an analysis was conducted of whether particular combinations of integrity requirements have become more prominent over time.

For this purpose, Venn diagrams were created that indicate how often all possible combinations of the six integrity requirements occur in the 349 texts. This was done for both the total period as well as for the two sub-periods separately. shows the result for the entire research period. includes the legend for the Venn diagram.

TABLE 4. Legend Venn diagram.

Since six types of integrity requirements were distinguished for the analytical framework, there would in principle be 64 (2∧6) possible combinations. But, since combinations of C and either A and/or B are not possible, 40 options remain. These 40 options were tested for significance through a parametric statistical t-test for independent samples, to test whether the two periods differed significantly in the occurrence of the various combinations.

On the level of individual profile descriptions, the Venn analysis presents some very interesting differences. For example, whereas some profile descriptions contain no integrity requirements at all or only one, three profile descriptions contain all possible aspects (ABDEF). The Westland 2018 job vacancy text provides a clear illustration since, in accordance with the national guidelines, it states “the mayor always acts unambiguously and transparently in accordance with generally accepted norms and values” (A). In addition, it states that the mayor’s legal duties include integrity, which is said to mean that the mayor “is independent and impartial" (B). These two ethical person requirements are then followed by three different types of ethical leadership requirements:

“With regard to integrity, he [the mayor] has an exemplary function” (D)

“He also actively monitors the integrity of the actions of the college, the council, and the civil service organization and makes the gray area negotiable.” + “The mayor promotes both the awareness of integrity and the prevention of (the appearance of) conflicts of interest.” (E)

“The mayor has an exemplary role, actively promotes integrity awareness and addresses others on this” (F)

When the prominence of the 40 combinations is compared over the two periods on a more abstract level using a t-test, four significant differences emerge. In all cases, this concerns combinations that follow the national definition of the moral person and that add aspects of ethical leadership ().

TABLE 5. Significant differences in combinations of integrity demands, 2008–2019.

This finding fits well with the new legal responsibility of the mayor for the promotion of administrative integrity and the increased attention for ethical leadership in general. The most striking change, however, concerns the ADF combination, which occurs less frequently in the second period and where there is a very high significance level (p=.00000095).

Both changes can be explained the fact that the national guidelines have changed on this point in 2016. They now also include the proactive action by the mayor (aspect E), as a result of which this aspect is included more often. At the same time, the original combination appears significantly less since the role of setting an example is included in the new guidelines less explicitly.

Conclusion and discussion

Whereas the societal and administrative attention for integrity has increased in the same decade and the issue has been high on the political agenda (Heres et al., Citation2019; Huberts, Citation2018), contrary to expectations, this study finds a significant decrease between 2008 and 2019 in integrity requirements being placed on Dutch candidate mayors in vacancy texts. One possible explanation could be that municipal councilors have come to value the integrity of candidates less. However, the increased saliency of integrity issues does not render this a very plausible account. Alternatively, the integrity of candidates and their efforts as ethical leaders may be taken more and more for granted (Jørgensen & Rutgers, Citation2014), which may serve as a motivation for councilors not to include such requirements in vacancy texts since these documents serve to distinguish suitable candidates from less suitable candidates. When all candidates are expected to be virtuous, it may not be needed to explicitly require them to be (Rodriguez, Patel, Bright, Gregory, & Gowing, Citation2002). In the light of the formal recruitment and selection function of profile descriptions and the legal role that the texts play in assessing the performance of mayors, this explanation, which was derived from earlier focus group discussions, seems to tell only a part of the story. A third explanation could be that the introduction of the 2016 integrity law in the Netherlands has reduced the necessity of additionally including moral person and ethical leadership requirements in vacancy texts since there is now an added law to evaluate mayors’ performance by.

At the same time, a significant increase can be observed in the focus on the role of the mayor in promoting the administrative integrity of the municipality, which is in line with the 2016 legislative change. Although reactive interventions and “setting an example” remain more important, the attention for proactive moral interventions has increased significantly. This shift is reflected both in the separate integrity requirements as well as in the combination of requirements. However, 43.3% of the municipal councils still do not impose any ethical leadership requirements on mayors, and of those that do, on average, only 11.5% impose proactive moral intervention requirements.

The broader relevance of the analysis lies in the fact that, as called for by Huberts (Citation2018), an empirical analysis is provided of what is expected of ethical leaders. In addition, the data show how understandings of integrity and ethical leadership can change over time. The latter emphasizes the context specificity of the integrity concept (see also Zhu et al., Citation2019). Also, the analysis of the ethical leadership requirements posed on the Dutch mayor provides a unique and valuable insight into what integrity and ethical leadership imply in the public domain (Heres et al., Citation2019; Karsten, Citation2019a).

Admittedly, “job adverts only represent a small part of the phenomenon being investigated” (Harper, Citation2012, p. 45; see also Jørgensen & Rutgers, Citation2014 ). Council members may have and express additional or different expectations of candidate mayors as regards integrity beyond the profile descriptions. In addition, as part of the selection procedure, candidate mayors are screened for integrity risks by the commissioner of the King. The fact that the selection of mayors in the Netherlands is classified as secret adds to the complexity of unearthing the integrity requirements placed on them through the use of alternative research methods. Interviews with candidate-mayors or councilors, for example, would have produced non-specified information at best since the law prohibits participants to divulge any information about the actual selection. Further, profile descriptions are the product of a collective body that needs to reach a majority agreement on the final text, which makes it difficult to identify the preferences of individual councilors.

Nevertheless, profile descriptions provide original data on the desired qualities of mayors, which offers relevant information on the profession and the context in which mayors operate. Also, profile descriptions have a crucial role in the selection of candidates, as a formal performance evaluation standard, and in the day-to-day work of mayors. For this reason, they cannot be ignored in the study of political leadership and ethical leadership (Karsten, Citation2019b).

Further empirical research on integrity management in the public sector is still very much required (Greenbaum, Quade, & Bonner, Citation2015; Heres et al., Citation2019; Huberts, Citation2018). Such research could usefully investigate whether and how citizens’ expectations of mayors on the matter deviate from councilors’ expectations. With exceptions (Hlynsdottir, Citation2016; Kukovic, Copus, Hacek, & Blair, Citation2015), information on citizens’ expectations of mayors is still rare. Such research could usefully identify the desired integrity qualities of mayors in different societal and institutional contexts.

Our study contributes to this line of research by identifying the required leadership competencies in the field of integrity for Dutch mayors and demonstrating that significant shifts are taking place in the direction of proactive integrity management. The findings can also contribute to the conceptual interpretation of the concept of “administrative integrity” and its translation into policy (Khaouja et al., Citation2019; Mohammad & Nicoleta Camelia, Citation2016). Finally, by showing that there is ample room for the crucial local customization of integrity requirements, the findings carry profound policy relevance.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bee, O. K., & Hie, T. S. (2015). Employers' emphasis on technical skills and soft skills in job advertisements. The English Teacher, 44(1), 1–12.

- Brown, M. E., & Treviño, L. K. (2006). Ethical leadership: A review and future directions. The Leadership Quarterly, 17(6), 595–616.

- Cohen, M. J. (2018). Hoeder van integriteit. Bestuurswetenschappen, 72(2), 3–4. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5553/Bw/016571942018072002001

- Den Hartog, D. N., Caley, A., & Dewe, P. (2007). Recruiting leaders: An analysis of leadership advertisements. Human Resource Management Journal, 17(1), 58–75.

- Greenbaum, R. L., Quade, M. J., & Bonner, J. (2015). Why do leaders practice amoral management? A conceptual investigation of the impediments to ethical leadership. Organizational Psychology Review, 5(1), 26–49.

- Harper, R. (2012). The collection and analysis of job advertisements: A review of research methodology. Library and Information Research, 36(112), 29–54. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.29173/lirg499

- Heres, L. (2014). One style fits all? A study on the content, effect, and origins of follower expectations of ethical leadership. Amsterdam: VU University Amsterdam.

- Heres, L., & Lasthuizen, K. M. (2012). What's the difference? Ethical leadership in public, hybrid and private sector organizations. Journal of Change Management, 12(4), 441–466.

- Heres, L., Lasthuizen, K. M., & Webb, W. (2019). Ethical leadership within the public and political realm: A dance with wolves? Public Integrity, 21(6), 549–552.

- Hernandez, M., Eberly, M. B., Avolio, B. J., & Johnson, M. D. (2011). The loci and mechanisms of leadership: Exploring a more comprehensive view of leadership theory. The Leadership Quarterly, 22(6), 1165–1185.

- Hlynsdottir, E. (2016). Leading the locality: Icelandic local government leadership dilemma. Lex Localis, 14(4), 807–826.

- Huberts, L. W., Anechiarico, F., & Six, F. (2008). Local integrity systems: World cities fighting corruption and safeguarding integrity. The Hague: BJu Legal.

- Huberts, L. W. J. C. (2018). Integrity: What it is and why it is important? Public Integrity, 20(1), S18–S32. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10999922.2018.1477404

- Jans, W. (2015). Policy innovation in Dutch municipalities. Enschede: University of Twente.

- Jørgensen, T. B., & Rutgers, M. R. (2014). Tracing public values change: A historical study of civil service job advertisements. Contemporary Readings in Law & Social Justice, 6(2), 59–80.

- Karsten, N. (2019a). Not biting the hand that feeds you: How perverted accountability affects the ethical leadership of Dutch mayors. Public Integrity, 21(6), 571–581. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10999922.2019.1604060

- Karsten, N. (2019b). What councilors expect of facilitative mayors: The desired leadership competencies in job advertisements for the Dutch mayoralty and how they are affected by municipal size. Lex Localis, 17(1), 177–197. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4335/17.1.179-199(2019)

- Karsten, N., & Hendriks, F. (2017). Don’t call me a leader, but I am one: The Dutch mayor and the tradition of bridging-and-bonding leadership in consensus democracies. Leadership, 13(2), 154–172.

- Khaouja, I., Mezzour, G., Carley, K. M., & Kassou, I. (2019). Building a soft skill taxonomy from job openings. Social Network Analysis and Mining, 9(1), 43.

- Kukovic, S., Copus, C., Hacek, M., & Blair, A. (2015). Direct mayoral elections in Slovenia and England: Traditions and trends compared. Lex Localis, 13(3), 693–714.

- Lawton, A., & Páez, I. (2015). Developing a framework for ethical leadership. Journal of Business Ethics, 130(3), 639–649. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2244-2

- Mayer, D. M., Kuenzi, M., Greenbaum, R., Bardes, M., & Salvador, R. B. (2009). How low does ethical leadership flow? Test of a trickle-down model. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 108(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2008.04.002

- Ministry of the Interior and Kingdom Relations. (2016). Handreiking burgemeesters: Benoeming, herbenoeming, klankbordgesprekken en afscheid. The Hague: Ministry of the Interior and Kingdom Relations

- Mohammad, J., & Nicoleta Camelia, C. (2016). Strategies to improve the quality of personnel recruitment and selection in public administration. Management Strategies Journal, 31(1), 219–226.

- Moore, C., Mayer, D. M., Chiang, F. F., Crossley, C., Karlesky, M. J., & Birtch, T. A. (2019). Leaders matter morally: The role of ethical leadership in shaping employee moral cognition and misconduct. Journal of Applied Psychology, 104(1), 123–145. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000341

- Municipality of Sluis. (2017) Profielschets nieuwe burgemeester. Sluis: Municipality of Sluis

- Palmer, D. E. (2009). Business leadership: Three levels of ethical analysis. Journal of Business Ethics, 88(3), 525–536. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-009-0117-x

- Rodriguez, D., Patel, R., Bright, A., Gregory, D., & Gowing, M. K. (2002). Developing competency models to promote integrated human resource practices. Human Resource Management, 41(3), 309–324. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.10043

- Roy, S. (2017). The significance of business ethics as a competency requirement in Fiji’s accountancy profession. Australian Academy of Accounting and Finance Review, 2(3), 264–279.

- Tan, L. M., & Laswad, F. (2018). Professional skills required of accountants: What do job advertisements tell us? Accounting Education, 27(4), 403–432. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09639284.2018.1490189

- Thompson, D. (1980). Moral responsibility of public officials: The problem of many hands. American Political Science Review, 74(4), 905–916. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/1954312

- Trevino, L. K., Hartman, L. P., & Brown, M. (2000). Moral person and moral manager: How executives develop a reputation for ethical leadership. California Management Review, 42(4), 128–142. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/41166057

- Tsahuridu, E., & Perryer, C. (2002). Ethics and integrity: What Australian organizations seek and offer in recruitment advertisements. Public Administration & Management, 7(4), 304–319.

- Versteden, C. J. N. (2014). De nieuwe bepalingen in Gemeentewet en Provinciewet inzake de zorg voor bestuurlijke integriteit: Een zorgplicht tevens zorgelijke plicht? De Gemeentestem, 40(7403), 39–46.

- Zhu, J., Liao, Z., Yam, K.C., & Johnson, R. E. (2018). Shared leadership: A state‐of‐the‐art review and future research agenda. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 39(7), 834–852. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2296

- Zhu, W., Zheng, X., He, H., Wang, G., & Zhang, X. (2019). Ethical leadership with both “moral person” and “moral manager” aspects: Scale development and cross-cultural validation. Journal of Business Ethics, 158(2), 547–565. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3740-y