Abstract

While most city governments in the United States acknowledge the importance of clean and healthy natural environment, their commitment to environmental sustainability varies widely. Scholarship on why some cities pursue the environmental agenda more than others is still evolving. This research adds to the model of municipal sustainability adoption by showing negative effects of residents’ political conservatism and positive effects of environmentally conscious neighboring cities on local sustainability action. The analysis of data for government finances and employment over the Great Recession also shows that commitment to sustainability was not associated with any distinct patterns in spending, debt or employment. Taken together, these findings point at a non-neutral role of social factors in sustainability transitions and suggest that cities pursuing the environmental mission can withstand tough economic times without substantial performance tradeoffs.

Commitment to environmental sustainability has recently become a type of ethical responsibility for public administrators and a way to create and safeguard public value through environmental action (Alibašić, Citation2017, Citation2022; Christie, Citation2018). The adoption of sustainability practices by American cities, however, is highly uneven and varies widely in scope and strategies used (Ji & Darnall, Citation2018; Wang et al., Citation2012). Though the sustainability adoption literature has grown substantially over the past decade (Zeemmering, Citation2018), understanding its determinants and outcomes is still evolving. For example, scholars do know that sustainability adoption is more active in larger cities with higher revenues, more educated populations, the council-manager form of government, cities in the West and Northeast, central cities, and in cities from states with strong environmental policy orientations. The understanding of the political and social determinants of sustainability adoption, however, is still wanting. Similarly, little is known about the relationship between sustainability action and other aspects of government performance such as government ability to control spending, manage debt, and manage workforce while taking up a sustainability mission. Since environmentally sustainable practices, from recycling to greenhouse reduction, are visible socially and may involve financial and managerial tradeoffs, exploring these relationships offers insight into how cities manage these transitions and can inform future local transitions to sustainable development.

This work adds to the literature on the adoption and outcomes of sustainability practices in several ways. First, it shows the effects of local residents’ political ideology and environmentally-conscious neighbor municipalities on the adoption of sustainability practices by cities. Then, the article examines the relationship between sustainability adoption and city spending, debt issuance and government hiring. It documents that local resident political conservatism effectively impedes sustainability adoption whereas a city’s geographic proximity to other sustainability-conscious local governments encourages it. No statistically significant effects of sustainable practices on local spending, debt issuance and employment management are detected over a prolonged economic recession.

To develop the first part of the paper, we use data on sustainability practices from a large national survey of cities conducted by the International City/County Management Association (ICMA) in 2010. To look at the linkages between environmental sustainability and the outcomes of financial and human resource management, we use the information on local spending, debt, and government employment from the 2007 and 2012 Censuses of Local Government Finances of the U.S. Census Bureau. As in these years, the Unites States saw a dramatic decline in economic output due to the Great Recession of December 2007–June 2009 (Chernick and Reschovsky Citation2017), the 2010 ICMA survey, bookended by two Censuses of Local Government Finances, provides for a close to the natural experiment setting for examining the relationships between sustainability and government performance in a recession.

What does sustainability adoption mean locally?

In the late 1980s, sustainability was defined by the United Nations as a societal modus operandi that focuses on meeting “the needs of the present generation without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their needs” (WCED, Citation1987, p. 41). Over time, the global sustainability framework has come to include a triple bottom line, with environmental, economic, and social goals (Savitz and Weber Citation2006; United Nations [UN], 2020). As of 2020, the United Nations sustainability development goals include 17 types of activities that foster sustainability, and over half of these goals focus on the economic and social objectives rather than environmental practices (UN, Citation2020). Governance goals that involve “internal efficacy, operational capacity, institutional longevity, and organizational resilience” (p. 40) as well as governmental accountability to all stakeholders are now recognized as the fourth facet of sustainability and call for the “quadruple bottom-line” (Alibašić, Citation2017).

The discourse on local government sustainability in the U.S. differs from the global discourse. When city leaders discuss sustainability, they often talk about prioritizing actions and practices that may contribute to economic development, design of urban space, and civic engagement while the term “sustainability” defies a simple definition (Zeemering, Citation2009; Osgood et al., Citation2017). Yet, in relative terms, local sustainability action is more focused on environmentally sustainable practices than on practices relating to social or economic resilience.

Local environmental sustainability action includes a wide range of practices and policies from recycling to energy efficient buildings (see for a list of local sustainability practices included in the ICMA survey). Linkages between environmental sustainability and social equity are of increasing interest to researchers, particularly in urban planning (Campbell, Citation1996; Campbell et al., Citation2015; Deslatte et al., Citation2017; Takai, Citation2014) but a more systematic integration of the social, economic, and governance dimensions into the framework of local sustainability action is still ahead (Alibašić, Citation2017; Chapman, Citation2008; Callahan & Pisano, Citation2014; Fiorino, Citation2010; Opp & Saunders, Citation2013).

Table 1. Sustainability practices and policy priorities of local governments from the 2010 ICMA sustainability survey (adapted from ICMA, Citation2010; Svara, Citation2011).

The first national survey of sustainability practices in U.S. cities and counties was fielded by the ICMA in 2010 and collected data on 109 practices and policies of sustainable development (ICMA, Citation2010; Svara, Citation2011). The analysis in this paper relies on an index of sustainability action (described in the Data and Methods section) that is based on the ICMA survey.

presents the types of sustainability policies that were included in the index and provides percentage frequencies of specific environmental practices pursued by cities and their self-reported policy priorities. Recycling is the most common environmental practice, with 90% of the respondents engaged in at least some recycling activities. It is followed by transportation improvements (82%) and energy conservation (81%). Less than a quarter of the respondents had an alternative energy policy in place (23%) in 2010. About 60% of the respondents practiced sustainability in at least one of the 11 areas for sustainable action.

When it comes to prioritization, local governments traditionally place the highest priority on the growth of local economy and policies that help economic development (94%), followed by energy conservation (72%), and then the environment itself (60%). Interestingly, local governments that place a very high priority on sustainability are less likely to emphasize economic policies and are more likely to prioritize policies related to public transportation, green jobs, and climate change mitigation (Svara, Citation2011). Such priorities may be reflective of a vision of urban development where economic growth accompanies rather than conditions human well-being. In fact, city sustainability efforts that manifest as pleasing natural and built environments have been shown to attract high-skilled workforce (Hawkins et al., Citation2016; Krause & Hawkins, Citation2021).

Literature on determinants and outcomes of sustainability adoption

Literature on local sustainability adoption has documented many patterns in sustainability action among local governments. We know that cities in Western states, especially California, have led the way in adopting sustainable practices in the United States (Kwon et al., Citation2014; Opp & Saunders, Citation2013; Opp et al., Citation2014). Larger cities with higher revenues per capita, as well as central cities and cities with the council-manager form of government, have been more committed to sustainable practices than others (Homsy & Warner, Citation2015; Krause et al., Citation2019; Opp & Saunders, Citation2013; Portney & Berry, Citation2010). City fiscal and human resource capacities have been shown to be the strongest factors that influence city involvement in climate change mitigation (Homsy & Warner, Citation2015; Krause, Citation2012). The effects of local demography have also been noted, with a higher share of college-educated residents in a city associated with a higher number of sustainable practices (Homsy & Warner, Citation2015). Yet, researchers note that sustainability is often low on the agendas of local managers and political leaders and that evaluation of sustainability outcomes in cities is still rare which precludes adaptive learning and further progress (Laurian & Crawford, Citation2016).

Since localities are subject to state laws and constraints in their ability to tax and spend public funds, fiscal federalism may also affect local sustainability transitions. These effects, however, are not easy to predict with certainty. State policies and laws can encourage local sustainability action (Brandtner & Suárez, Citation2021; Homsy & Warner, Citation2015); have no influence on local climate change adaptation (Shi et al., Citation2015), or stall local sustainability initiatives (Elliot et al., Citation2017). An example of the latter is an overruling of city ordinances that restricted gas and oil exploration within city limits and banned plastic grocery bags by the conservative Texas state legislature (Elliot et al., Citation2017).

More broadly, local sustainability practices are influenced by their institutional environments (Bryan, Citation2016; Hawkins & Wang, Citation2012; Hawkins et al., Citation2016, Citation2018; Krause & Hawkins, Citation2021; Lubell et al., Citation2020; Scott & Carter, Citation2019). Cities with stronger business group support and environmental group support engage in more expansive collaborative networks of environmental impact mitigation (Hawkins et al., Citation2018). Cities from states with a stronger environmentally-focused nonprofit sector were shown to adopt sustainability practices more actively (Brandtner & Suárez, Citation2021). Both vertical and horizontal intergovernmental networks may affect environmental action (Hughes, Citation2015; Koontz & Thomas, Citation2006) though the effects of hierarchical structures have been shown to affect environmental policy action more than horizontal networks (Laurian & Crawford, Citation2016).

Transition to sustainable principles can lead to direct environmental gains such as energy and natural resource conservation, improved health outcomes, and even growth in biodiversity. These outcomes, however, may depend on policy implementation, actors engaged in sustainability action including special interests (Bulkeley & Betsill, Citation2005; Koontz et al., Citation2004; Koontz, Citation2005; Koontz & Thomas, Citation2006; Lubell et al., Citation2020; Portney, Citation2005). Sustainability transitions may also produce unintended consequences such as changes in urban form and “ecogentrification” (Cucca, Citation2012). Specifically, sustainable development goals may change spatial patterns of cities, with more green space amenities leading to higher real estate prices and ousting low-income populations out of their homes unless these effects are counteracted by policies that reinforce social equity such as affordable housing planning (Cucca, Citation2012). Regardless of these potential location-specific challenges of urban planning, local administrators, as stewards of the public good, have an ethical obligation to city residents to manage scarce resources responsibly and act on environmental threats with effect (Alibašić, Citation2022).

In light of the growing interest in the outcomes of sustainability management, it is still largely unexplored how a city’s commitment to sustainability affects other aspects of city governance and performance. It is particularly valuable for practice to gauge how sustainability practices influence city finance and human resource management. On the one hand, sustainability implementation may be financially and organizationally burdensome. On the other hand, cities committed to environmentally sustainable practices may also be oriented toward longer-term planning and strategic resilience financially and organizationally. In this case, local commitment to environmental sustainability may correlate with sustainable financial and human resource management positively rather than threaten it. One of the challenges of such analysis empirically has traditionally been the difficulty of combining data from very different sources for a large national sample.

Hypotheses

Voter political ideology

While being embedded in the context of the federal environmental regulations and state influences, city commitment to sustainability practices is still largely a product of local deliberation and decision-making. The classic median voter model predicts that city policy choices should be influenced by local voters, whose aggregate policy preferences officials hold in sight (Downs, Citation1957). Even though the effects of political factors on local management are traditionally weaker than the effects of political factors at the state and federal level (Ferreira & Gyourko, Citation2009), local voter political preferences have been shown to find their way into the determination of local spending agendas. So, for example, Gerber and Hopkins (Citation2011) found that local elections of democratic mayors were associated with a reduction of spending on police and fire and with an increase of spending on transportation and housing. Alonso and Andrews (Citation2020) showed that left-wing governments tend to be less open to outsourcing service provision. In terms of sustainability correlates, negative effects of local political conservatism on a city’s choice of environmental policy instruments have been noted (Krause et al., Citation2019). The literature on the environmental “impacts” of local political ideology, however, remains thin (Hughes, Citation2017).

Conservatism and free-market individualism is associated with low environmental awareness and lack of willingness to address climate change (Heath & Gifford, Citation2006; Leiserowitz et al., Citation2010; Leiserowitz et al., Citation2016; Mildenberger et al., Citation2017). Though most Americans believe that climate change is a “major threat” and support policies that protect the environment, a wide partisan divide exists between Democrats and Republicans in the perception of seriousness of climate change and in the views on what government should do to address it (Funk & Kennedy, Citation2020; Kennedy, Citation2020). Based on these patterns, we expect that the political inclinations of local voters will affect whether local governments will prioritize sustainability practices. Specifically, we expect that political conservatism will hamper sustainability adoption locally (H1).

Neighbor proximity and policy diffusion

As a public good, environmental sustainability transcends jurisdictional boundaries; therefore, sustainability management naturally represents a collective action problem (Krause & Hawkins, Citation2021) and can be expected to involve relationships with other local governments, nonprofits, and the corporate sector. The understanding of network structures, actor involvement, and multijurisdictional policy environments that facilitate environmental policy success is one of the budding avenues for research in polycentric governance (Koontz & Thomas, Citation2006; Krause et al., Citation2019; Krause & Hawkins, Citation2021; Scott and Carter, Citation2019).

Apart from the explicit engagement in collaborative environmental networks with multiple actors as partners, cities may also be influenced by local peers. Cities are known to compete for the tax base, participate in the same councils of governments, and otherwise compare themselves to their neighbors. The classic law of geography posits that “everything is related to everything else, but near things are more related than distant things” (Tobler, Citation1970; Mildenberger et al., Citation2017). Does this law hold in the context of the sustainability policy diffusion at the local level?

Policy diffusion can occur though the mechanisms of vertical and horizontal transfer (Mitchell, Citation2018; Walker, Citation1969). The vertical transfer happens when smaller units adopt a policy of a hierarchically superior unit, such as, for example, when local governments adopt sustainability in states with active environmental agendas (Brandtner & Suárez, Citation2021; Homsy & Warner, Citation2015). The horizontal transfer occurs when close entities, often with contiguous borders, imitate each other. While we do know that the vertical transfer effects between state and localities are present (Homsy and Warner Citation2015), the extent to which local commitment to sustainability includes horizontal spillovers is an empirical question that has not yet been answered. The horizontal transfer may occur when neighboring jurisdictions belong to the same council of governments and establish similar policy priorities, act in concert in the pursuit of shared environmental goals through interlocal agreements, and mimic neighboring jurisdictions (against whom they may compare themselves financially, organizationally, and operationally) to keep up with trends in local governance. While evidence of local collaboration on sustainability action has been building (Hawkins, Citation2020; Krause et al., Citation2021), the association between city sustainability scores among neighbors has not been studied quantitatively at the national level. Based on these common practices, we expect to observe some mimicry among neighboring jurisdictions. Specifically, we expect that sustainability commitment of neighbor cities will have a positive association with the city’s own commitment to sustainable practices (H2).

Sustainability and city performance

Next, we proceed to examining whether a city’s sustainability commitment affects its financial and human resource management. The direction of these effects is difficult to predict with certainly. On the one hand, cities focused on environmental sustainability may promote the sustainability vision across the government, engage in more longer-term planning and favor more stable fiscal and human resource management patterns. As a result, city spending, debt issuance and hiring may reflect the sustainability mindset and be relatively constrained.

On the other hand, prior research has shown a positive relationship between sustainability adoption and city revenues suggesting that wealthier cities tend to adopt sustainability more actively (Homsy Mitchell, Citation2018; Krause, Citation2012; Lubell et al., Citation2009; Sharp et al., Citation2011; Warner, 2015; Zahran et al., Citation2008). Based on this previously established pattern, we acknowledge that commitment to environmental sustainability is resource-consuming and may exert additional fiscal pressure on a government’s budget by increasing the demand for additional spending, for funding sustainable infrastructure through debt and also by implementing the sustainability mission through additional workforce involvement. Given the exploratory nature of this analysis, we acknowledge plausibility of the effects in either direction and formulate the theoretical expectations in line with the “resource consumption” rationale. We expect that a higher commitment to environmental sustainability will be associated with higher spending (H3), higher debt (H4) and higher government employment (H5) over a recessionary period, relative to cities with lower sustainability commitments.

Data and methods

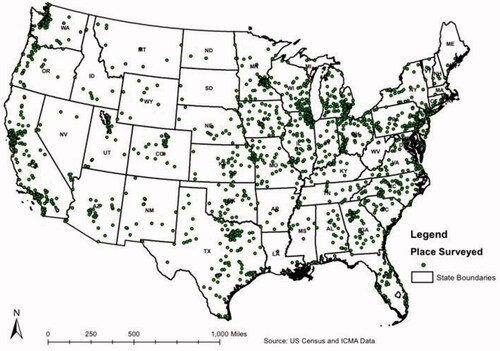

To test the hypotheses, we combine data from three sources. City sustainability practices and the form of government variables are drawn from the 2010 and 2011 national surveys of cities and counties conducted by the International City/County Management Association (ICMA). presents the full sample of cities used in the analysis. Demographic variables come from the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey, fiscal data—from the Censuses of Local Government Finances, and city employment data come from the Annual Surveys of Public Employment from the U.S. Census Bureau for years 2007 and 2012 (U.S. Census Bureau, Citation2017). After removing observations with missing values, we work with a sample of 1,574 cities. The variable that captures the political leaning of local residents comes from a unique dataset compiled through the American Ideology Project (AIP) and is only available for municipalities with population over 25,000 (see the project and data description in Tausanovitch & Warshaw, Citation2014). While using these data comes with the sample size tradeoff, it gives us an opportunity to overcome the data availability problem at the city level that has precluded such research in the past.

Dependent variables

The first dependent variable—Sustainability Score—is a weighted cumulative score based on 109 questions about sustainability practices from the ICMA survey. The ICMA survey covered 12 dimensions of sustainability such as energy and water conservation, greenhouse reduction, transportation, recycling, sustainable land use, the use of sustainability principles in building and purchasing (for more detail, see Homsy & Warner, Citation2015; Svara, Citation2011). Like Homsy and Warner (Citation2015), we create a composite score of commitment to environmental sustainability by excluding the social equity dimension. We calculate the percentage of policies adopted by a city in each of the eleven dimensions and compute the average percentage of adopted sustainability policies across all dimensions. This approach prevents excessively high scores for cities with sustainability commitment in only a few dimensions. The composite score ranges from 0% to 100%.

The second dependent variable—Staff for Sustainability—is dichotomous. It equals 1 if a city employs at least one dedicated staff member to implement sustainability policies and zero otherwise. We examine this variable as an outcome because we view staff hired to implement the sustainability mission as a strong signal of sustainability commitment.

The other dependent variables—changes in expenditures per capita, changes in debt per capita, and changes in full-time employment per capita—are continuous and are measured in percent from 2007 to 2012.

Independent variables

As mentioned above, we test the effects of local resident political ideology using the AIP project dataset that creates a measure of political ideology at the city level based on the voting characteristics of city voters in the 2012 presidential election. The political ideology variable is standardized into a score that ranges from −1 to +1, with an increase in the score meaning an increase in conservatism (American Ideology Project [AIP], Citation2015).

To create a measure of neighbor sustainability commitment, we identify the city’s three closest neighbors included in the ICMA survey as respondents. To calculate distances between the localities, we use their centroid tag geographic coordinates in ArcGIS. After finding the city’s closest three neighbors, we average their sustainability scores and use the average as our variable of interest.

The other independent variables gauge city differences in fiscal, socio-economic, regional and governance characteristics to capture the effects of these factors on sustainability adoption that have been identified by the prior literature. Since local political ideology is only available for cities with population over 25,000 residents, we run and show the analysis for several samples side-by-side.

Descriptive statistics

presents the descriptive statistics of the full sample. In 2010, U.S. cities were still at an early stage of adopting sustainability practices, with an average city sustainability score of 18 points out of 100. Twenty-seven percent of the sample had dedicated staff for implementing sustainability policies. From 2007 to 2012, an average city saw an 18% increase in expenditures per capita, a 1.3% increase in debt per capita, and a 0.37 decline in government workers per 1,000 residents.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics.

In an average city, revenues per capita were $1,742 (in 2007 dollars, adjusted for inflation using the Consumer Price Index), median household income was $54,109, and population was 37,715 residents. In an average city, 72% of city residents identified as white and 57% had a college degree. Close to 90% of housing units were occupied, population density averaged 2,328 individuals per square mile and the average poverty rate in 2010 was at a high of 13.82% due to the Great Recession.

Close to 57% of the cities were suburban (lower density cities relatively removed from the core of a metropolitan area), 33%—independent (cities away from a metropolitan area), and the remaining 11% were central cities (cities in the core of a metropolitan area). Almost 64% of the sample had the council-manager form of government. The average sustainability score of the three closest neighbors was 19.32%points and the average distance to a city’s three closest neighbors was 14.7 miles. An average city voted democratic, with the political conservatism score of −0.345 on a scale from −1 to +1. At the modelling stage, the political ideology scores are converted into percentages for the ease of interpretation.

Multivariate results

shows Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) models that predict the city’s sustainability score and logistic regression models that predict the probability that a city has dedicated staff for sustainability management as a strong indicator of sustainability commitment.

Table 3. Predicted: sustainability score (OLS) and presence of staff for sustainability action (logit), standard errors in parentheses.

We observe that more conservative communities are less likely to support sustainability action. A one-unit increase in the score of political conservatism is associated with a 0.05 decrease in the city’s sustainability score and with a reduction in the probability of hiring staff for sustainability management. With a sample of cities with a population over 25,000, we show that conservative political ideology impedes sustainability practice adoption. H1 is supported.

The models also show non-neutral effects of neighbor sustainability scores on a city’s adoption of sustainable practices. A one-point increase in the mean sustainability score of a city’s neighbors increases a city’s own score by 0.12 points, on average. These findings show that a local government is more likely to jump on the sustainability train which carries its neighbors. H2 is supported. One of the important limitations of our test of this relationship, however, is that we only measure the effects of respondents to the ICMA survey. Neighboring localities that did not respond to the ICMA survey are an important omitted variable that can shed more light on the geographic pathways of the sustainability policy diffusion.

The effects of the control variables are also noteworthy. As expected, city revenues have a positive association with sustainability practices. However, the magnitude of the effects is rather small: a thousand dollar increase in total revenues per capita is associated with a 1.2 point increase in the sustainability score, on average. In contrast, for example, city managers encourage sustainability adoption by about 8 points on average, which, given the national average sustainability score of 18, is a 44% increase. While revenue capacity does matter for sustainability adoption, its effects are substantively smaller than the effects of a governance-related variable. Interestingly, the city revenue effects on sustainability practices weaken statistically with the inclusion of political ideology.

City size is positively associated with sustainability commitment and with the hiring of staff dedicated to sustainability cross all models. Suburban cities are less active in pursuing sustainability initiatives, relative to central cities, with these negative effects being stronger for cities with a population over 25,000. Relative to the Northeast, cities in the South are less active in sustainability adoption whereas cities in the West are more active. College-educated residents encourage sustainability commitment (both adoption and hiring staff) in smaller cities, while their effects on sustainability commitment in larger cities are not statistically different from zero. Local median household incomes, city revenues per capita and form of government, while influencing sustainability practices, do not influence sustainability-related hiring.

Overall, based on the findings, we conclude that sustainability commitment is facilitated by the resident wealth and city revenue wealth but these effects are substantively weaker than the effects of voter political ideology, city neighbor sustainability, and form of government.

Next, we transition to the models that show associations between sustainability practices and changes in government performance from 2007 to 2012. presents models that predict percent changes in spending per capita, debt per capita, and full-time government employment per 1,000 residents. In these models, we again examine the full sample and subsamples of cities, including cities with population over 25,000 residents for which we are able to include political ideology as a predictor.

Table 4. Predicted: percent changes in revenues, spending, debt levels and full-time employment from 2007 to 2012, ordinary least squares regression parameter estimates.

The results suggest that sustainability practices have no statistically significant effects on any of the three outcomes of interest. Hypotheses H3, H4 and H5 that expected sustainability practices to be positively associated with spending, debt, and hiring are not supported. While seemingly underwhelming, these findings mean that cities committed to environmental sustainability bear no sizable financial or human resource costs of this commitment in a recession. Since environmentally sustainable practices are not associated with lower spending, debt and public sector employment, relative to cities with lower sustainability scores, we conclude that the three-pronged vision of sustainability is still a theoretical notion rather than empirical reality of local sustainability management.

Discussion

We have examined the role of local voters and neighbor cities in sustainability adoption and identified them as statistically significant factors in the pursuit of environmental sustainability by U.S. cities. Local residents’ political conservatism is a strong deterrent of sustainability action whereas neighbor city commitment of sustainability is a strong incentive for sustainability adoption. These findings offer an eagle’s-eye perspective on the role of local political ideology and local peers in sustainability action and call for further research on the social aspects of sustainability management. Can the effects of political conservatism be mediated by local leadership? Under what conditions does the horizontal transfer of sustainability policy across cities strengthen? Such and similar research questions can further enrich the body of knowledge and practice of sustainability management.

By exploring the relationship of sustainability practices with city performance, we show that commitment to sustainability did not have any statistically significant associations with spending, debt, and public employment over 2007–2012. Cities that aspire to increase their sustainability action may take comfort in knowing that sustainability-conscious cities did not face additional spending, debt or public employment costs when subjected to the stress of a prolonged recessionary period relative to cities that are less committed to sustainability.

This analysis is based on a two-point-in-time measure of local financial and employment activity. Longitudinal data would offer stronger evidence on the association of sustainability action and financial management and employment in local government. In addition to the limitations of the paper related to the data structure, we need to acknowledge that the 2010 ICMA survey, while including a very large sample of cities, was not based on a random sample. Self-selection into participation represents a significant obstacle to causal inference in the study. Nevertheless, correlational patterns identified at an early stage of sustainability adoption by U.S. cities stimulate further thought and have value. While research on environmental sustainability has largely proceeded in the form of qualitative case studies and small within-state samples of local government, broad scale studies like the current paper have value as they provide a more generalized understanding of the patterns of sustainability adoption and outcomes across different locales.

Since our analysis documents a non-neutral role of local voters in the environmental sustainability walk of a city, it also suggests that differential political preferences locally may produce a growing polarization in local sustainability pursuits in the context of U.S. fiscal federalism. Normatively desirable civic engagement may produce normatively undesirable lack of sustainability action across conservative geographies, pitting direct local democracy against the professional ethics of city leaders who seek to create public value through environmental protection and regulation. In this context, local political leaders, such as mayors and council members, may be particularly important actors in sustainability adoption as brokers of local perceptions of the goals and ramifications of sustainability commitment for their city. As stewards of the public good, bold urban leaders may benefit from reminding themselves that they are at the center stage of environmental policy action in physical spaces with vast environmental impacts (Rosenzweig et al., Citation2010). Their action and inaction on sustainability is a policy choice. Their ability to integrate their professional value stances into work and their ethical commitment to creating public good through sustainability action will have the most immediate effects on local environmental quality and human well-being.

References

- Alibašić, H. (2022). The administrative and ethical considerations of climate resilience: The politics and consequences of climate change. Public Integrity, 24(1), 33–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/10999922.2020.1838142

- Alibašić, H. (2017). Measuring the sustainability impact in local governments using the quadruple bottom line. The International Journal of Sustainability Policy and Practice, 13(3), 37–45. https://doi.org/10.18848/2325-1166/CGP/v13i03/37-45

- Alonso, J. M., & Andrews, R. (2020). Political ideology and social services contracting: Evidence from a regression discontinuity design. Public Administration Review, 80(5), 743–754. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13177

- American Ideology Project. (2015). City-level preference estimates. https://americanideologyproject.com/

- Brandtner, C., & Suárez, D. (2021). The structure of city action: Institutional embeddedness and sustainability practices in U.S. cities. The American Review of Public Administration, 51(2), 121–138. https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074020930362

- Bryan, T. K. (2016). Capacity for climate change planning: Assessing metropolitan responses in the United States. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 59(4), 573–586. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2015.1030499

- Bulkeley, H., & Betsill, M. (2005). Rethinking sustainable cities: Multilevel governance and the “urban” politics of climate change. Environmental Politics, 14(1), 42–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/0964401042000310178

- Campbell, H. E., Kim, Y., & Eckerd, A. M. (2015). Rethinking environmental justice in sustainable cities: Insights from agent-based modeling. Routledge studies in public administration and environmental sustainability. Routledge.

- Campbell, S. (1996). Green cities, growing cities, just cities? Urban planning and the contradictions of sustainable development. Journal of the American Planning Association, 62(3), 296–312. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944369608975696

- Callahan, R., & Pisano, M. (2014). Aligning fiscal and environmental sustainability. In D. Mazmanian & H. Blanco (Eds.), The Elgar companion to sustainable cities: Strategies, methods and outlook (pp. 154–165). Edward Elgar Pub. Ltd.

- Chapman, J. I. (2008). State and local fiscal sustainability: The challenges. Public Administration Review, 68(1), S115–S131. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2008.00983.x

- Chernick, H., & Reschovsky, A. (2017). The fiscal condition of US cities: Revenues, expenditures, and the “Great recession”. Journal of Urban Affairs, 39(4), 488–505. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352166.2016.1251189

- Christie, N. V. (2018). A comprehensive accountability framework for public administration. Public Integrity, 20(1), 80–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/10999922.2016.1257349

- Cucca, R. (2012). The unexpected consequences of sustainability. Green cities between innovation and ecogentrification. Sociologica, (2), 1971–8853.

- Deslatte, A., Feiock, R. C., & Wassel, K. (2017). Urban pressures and innovations: Sustainability commitment in the face of fragmentation and inequality. Review of Policy Research, 34(5), 700–724. https://doi.org/10.1111/ropr.12242

- Downs, A. (1957). An economic theory of democracy. Harper Collins.

- Elliot, E., Goodman, D., & Kim, A. (2017). Texas in a federal system: Its evolving role. In E. Elliot & D. Goodman (Eds.), Texas: Yesterday and today—Readings in Texas politics and policy. Great River Learning.

- Feiock, R. C., Portney, K. E., Bae, J., & Berry, J. M. (2014). Governing local sustainability: Agency venues and business group access. Urban Affairs Review, 50(2), 157–179. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087413501635

- Ferreira, F., & Gyourko, J. (2009). Do political parties matter? Evidence from U.S. cities. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 124(1), 399–422. https://doi.org/10.1162/qjec.2009.124.1.399

- Fiorino, D. J. (2010). Sustainability as a conceptual focus for public administration. Public Administration Review, 70(1), s78–s88. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2010.02249.x

- Funk, C., Kennedy, B. (2020). How Americans see climate change and the environment in 7 charts. https://pewrsr.ch/2UqQsOI.

- Gerber, E. R., & Hopkins, D. J. (2011). When mayors matter: Estimating the impact of mayoral partisanship on city policy. American Journal of Political Science, 55(2), 326–339. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2010.00499.x

- Hawkins, C. V. (2020). Interlocal agreements and multilateral institutions: Mitigating coordination problems of self-organized collective action. International Journal of Public Administration, 43(7), 563–572. https://doi.org/10.1080/01900692.2019.1643879

- Hawkins, C. V., Kwon, S., & Bae, J. (2016). Balance between local economic development and environmental sustainability: A multi-level governance perspective. International Journal of Public Administration, 39(11), 803–811. https://doi.org/10.1080/01900692.2015.1035787

- Hawkins, C. V., & Wang, X. (2012). Sustainable development governance: Citizen participation and support networks in local sustainability initiatives. Public Works Management & Policy, 17(1), 7–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087724X11429045

- Hawkins, C. V., Krause, R. M., Feiock, R. C., & Curley, C. (2016). Making meaningful commitments: Accounting for variation in cities investments of staff and fiscal resources to sustainability. Urban Studies, 53(9), 1902–1924. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098015580898

- Hawkins, C. V., Krause, R., Feiock, R. C., & Curley, C. (2018). The administration and management of environmental sustainability initiatives: A collaborative perspective. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 61(11), 2015–2031. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2017.1379959

- Heath, Y., & Gifford, R. (2006). Free‐market ideology and environmental degradation: The case of belief in global climate change. Environment and Behavior, 38(1), 48–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916505277998

- Homsy, G. C., & Warner, M. W. (2015). Cities and sustainability: Polycentric action and multilevel governance. Urban Affairs Review, 51(1), 46–73. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087414530545

- Hughes, S. (2015). A meta-analysis of urban climate change adaptation planning in the U.S. Urban Climate, 14, 17–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.uclim.2015.06.003

- Hughes, S. (2017). The politics of urban climate change policy: Towards a research agenda. Urban Affairs Review, 53(2), 362–380. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087416649756

- ICMA. (2010). International city and county managers association. Local government sustainability policies and programs, survey. ICMA.

- Ji, H., & Darnall, N. (2018). All are not created equal: Assessing local governments strategic approaches towards sustainability. Public Management Review, 20(1), 154–175. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2017.1293147

- Kennedy, B. (2020). U.S. concern about climate change is rising, but mainly among democrats. https://www.pewresearch.org/?p=319435

- Koontz, T. M., Carmin, J. A., Steelman, T. A., & Thomas, C. W. (2004). Collaborative environmental management: What roles for government? RFF Press.

- Koontz, T. M. (2005). We finished the plan, so now what? Impacts of collaborative stakeholder participation on land use policy. Policy Studies Journal, 33(3), 459–481. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0072.2005.00125.x

- Koontz, T. M., & Thomas, C. W. (2006). What do we know and need to know about the environmental outcomes of collaborative management? Public Administration Review, 66(s1), 111–121. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2006.00671.x

- Krause, R. M. (2012). Political decision-making and the local provision of public goods: The case of municipal climate protection in the US. Urban Studies, 49(11), 2399–2417. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098011427183

- Krause, R., & Hawkins, C. V. (2021). Implementing city sustainability: Overcoming administrative silos to achieve functional collective action. Temple University Press.

- Krause, R. M., Hawkins, C. V., & Park, A. Y. S. (2021). The perfect amount of help: An examination of the relationship between capacity and collaboration in urban energy and climate initiatives. Urban Affairs Review, 57(2), 583–608. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087419884650

- Krause, R. M., Hawkins, C. V., Park, A. Y. S., & Feiock, R. C. (2019). Drivers of policy instrument selection for environmental management by local governments. Public Administration Review, 79(4), 477–487. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13025

- Kwon, M. J., Jang, H. S., & Feiock, R. C. (2014). Climate protection and energy sustainability policy in California cities: What have we learned? Journal of Urban Affairs, 36(5), 905–924. https://doi.org/10.1111/juaf.12094

- Laurian, L., & Crawford, J. (2016). Organizational factors of environmental sustainability implementation: An empirical analysis of US cities and counties. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 18(4), 482–506. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2016.1138403

- Leiserowitz, A., Maibach, E., Roser-Renouf, C., Rosenthal, S., & Cutler, M. (2016, December 13). Politics & global warming, November 2016. Yale program on climate change communication. http://climatecommunication.yale.edu/publications/politics-global-warming-november-2016/

- Leiserowitz, A., Smith, N., Marlon, J. (2010, October 12). Americans knowledge of climate change. Yale project on climate change communication. http://climatecommunication.yale.edu/publications/americans-knowledge-of-climate-change/

- Lubell, M., Feiock, R. C., & Handy, S. (2009). City adoption of environmentally sustainable policies in California’s central valley. Journal of the American Planning Association. 75(3), 293–308. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944360902952295

- Lubell, M., Mewhirter, J., & Berardo, R. (2020). The origins of conflict in polycentric governance systems. Public Administration Review, 80(2), 222–233. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13159

- Mildenberger, M., Marlon, J., Howe, P., & Leiserowitz, A. (2017). The spatial distribution of republican and democratic climate opinions at state and local scales. Climatic Change, 145(3–4), 539–548. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-017-2103-0

- Mitchell, J. L. (2018). Does policy diffusion need space? Spatializing the dynamics of policy diffusion. Policy Studies Journal, 46(2), 424–451. https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12226

- Opp, S. M., & Saunders, K. L. (2013). Pillar talk: Local sustainability initiatives and policies in the United States—Finding evidence of the “Three-E’s”: Economic development, environmental protection, and social equity. Urban Affairs Review, 49(5), 678–717. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087412469344

- Opp, S. M., Osgood, J. L., & Rugeley, C. R. (2014). Explaining the adoption and implementation of local environmental policies in the United States. Journal of Urban Affairs, 36(5), 854–875. https://doi.org/10.1111/juaf.12072

- Osgood, J. L., Opp, S. M., & DeMasters, M. (2017). Exploring the intersection of local economic development and environmental policy. Journal of Urban Affairs, 39(2), 260–276. https://doi.org/10.1111/juaf.12316

- Portney, K. E. (2005). Civic engagement and sustainable cities in the United States. Public Administration Review, 65(5), 579–591. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2005.00485.x

- Portney, K. E., & Berry, J. M. (2010). Participation and the pursuit of sustainability in U.S. cities. Urban Affairs Review, 46(1), 119–139. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087410366122

- Rosenzweig, C., Solecki, W., Hammer, S. A., & Mehrotra, S. (2010). Cities lead the way in climate-change action. Nature, 467(7318), 909–911. https://doi.org/10.1038/467909a

- Savitz, A. W., & Weber, K. (2006). The triple bottom line. Jossey-Bass.

- Scott, T. A., & Carter, D. P. (2019). Collaborative governance or private policy making? When consultants matter more than participation in collaborative environmental planning. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 21(2), 153–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2019.1566061

- Sharp, E. B., Daley, D. M., & Lynch, M. S. (2011). Understanding local adoption and implementation of climate change mitigation policy. Urban Affairs Review, 47(3), 433–457. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087410392348

- Shi, Linda, Eric Chu & Jessica Debats (2015) Explaining Progress in Climate Adaptation Planning Across 156 U.S. Municipalities, Journal of the American Planning Association, 81(3), 191–202.

- Svara, J. H. (2011). The early stage of local government action to promote sustainability. Municipal Yearbook, 43–60.

- Takai, K. (2014). Pursuing sustainability with social equity goals. https://icma.org/articles/pm-magazine/pursuing-sustainability-social-equity-goals

- Tausanovitch, C., & Warshaw, C. (2014). Representation in municipal government. American Political Science Review, 108(3), 605–641. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055414000318

- Tobler, W. (1970). A computer movie simulating urban growth in the Detroit region. Economic Geography, 46, 234–240. https://doi.org/10.2307/143141

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2017). Census of governments. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/cog.html

- United Nations. (2020). https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/.

- Walker, J. L. (1969). The diffusion of innovations among the American states. American Political Science Review, 63(3), 880–899. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055400258644

- Wang, X., Hawkins, C. V., Lebredo, N., & Berman, E. M. (2012). Capacity to sustain sustainability: A study of U.S. cities. Public Administration Review, 72(6), 841–853. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2012.02566.x

- WCED. (1987). World commission on environment and development. Our common future. http://www.un-documents.net/our-common-future.pdf

- Zahran, S., Himanshu, G., Brody, S. D., & Vedlitz, A. (2008). Risk, stress, and capacity: Explaining metropolitan commitment to climate protection. Urban Affairs Review, 43(4), 447–474. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087407304688

- Zeemering, E. S. (2009). What does sustainability mean to city officials? Urban Affairs Review, 45(2), 247–273. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087409337297

- Zeemmering, E. S. (2018). Sustainability management, strategy and reform in local government. Public Management Review, 20(1), 136–153.