Abstract

With growing discussion and action around inequality, climate change, and a global pandemic, do the current pillars of public administration, economy, efficiency, and effectiveness, also known as the 3Es, meet the needs of the public administration? We propose that there are new pillars which better respond to 21st century problems in ways not addressed through values of efficiency, effectiveness, and economy. In this article, we will explore these new 4Es (empathy, engagement, equity, and ethics) in more depth, as well as articles in the first half of this double special issues on the topic. Through this article and special issue, we are eager to move the field of public administration forward towards creating more engaged, empathetic, equitable, and ethical public and nonprofit organizations.

Keywords:

How can the field of public administration be at the forefront of the change that the world needs on key, cross-cutting issues, such as pandemic response, climate change, income inequality, administrator-community relations, long standing inequities and injustices, decolonization, and more? What skills do public administrators, both those in government and nonprofit work, require to respond to these complex and wicked problems? Traditional values of efficiency, effectiveness, and economy, known as the “3Es,” are clearly one way to tackling these problems. For instance, efficiency prompts administrators to well use resources; effectiveness mandates that programs achieve their desired goals; economy centers the imperative that programs should be reasonably priced, especially since they use public money.

However, despite the continued importance of these traditional “pillars” of the discipline, numerous scholars and practitioners have argued that they miss important dimensions of public administration. For instance, Frederickson (Citation2010) argued that traditional public administration did not factor in considerations of equity, noting that it was as important to ask who a policy or program benefits, not just how. Systems can be efficient, effective, and economical without being equitable. Moreover, such systems, despite other values of bureaucratic neutrality, create, maintain, and extend disadvantage and marginalization of vulnerable communities (Portillo et al., Citation2020). As such, thanks to the work of social equity pioneers throughout the field, by the early 21st century, equity became a central pillar mandating fairness for all (Gooden, Citation2014, Citation2015; Johnson & Svara, Citation2015a, Citation2015b; Svara, Citation2014; Williams, Citation1947).

However, equity is not enough to meet the needs of our communities. For instance, empathy is needed to meet people where they are, to understand and share their feelings and concerns, and to act meaningfully to care for others (Dolamore, Citation2021). Relatedly, ethics mandate that administrators must embody key values. As per the code of ethics of the American Society for Public Administration (ASPA), administrators should promote the public interest, uphold constitutions and laws, promote democratic participation, strengthen social equity, fully inform and advise, demonstrate personal integrity, promote ethical organizations, and advance professional excellence (McCandless & Ronquillo, Citation2020; Svara, Citation2014; Svara et al., Citation2015). However, promoting any of these values requires engagement, especially with populations historically marginalized by public administration, and engagement is an important way public administrators work with communities to solve problems (Alkadry & Blessett, Citation2010). Since individual administrators are not neutral actors, public administration requires moving beyond models of constituents as customers and treating them as people (Dolamore, Citation2021; Humphrey; Citation2021; Portillo et al., Citation2020). Work by organizations such as the Section on Democracy and Social Justice in ASPA, the National Academy of Public Administration, and the Social Equity Leadership Conference, among others, have already started asking what if public administration focused more on engagement, empathy, ethics, and equity.

To move the conversation forward in public administration, we propose that four “new” pillars should guide our research and teaching: Empathy, Engagement, Equity, and Ethics. These 4Es provide the modern public administrator with the skills they need to serve the public in the 21st century and represent the field better than is possible with simply the 3Es of economy, efficiency, and effectiveness. We do not argue that these new 4Es by themselves are new (the field has been examining all four for decades) but rather, argue for a new formulation of the values of the field. We posit that to fulfill the numerous priorities in the field–whether efficiency, effectiveness, accountability, responsiveness, transparency, and more–we must act in ways that foster empathy, engagement, equity, and ethics. These “new” 4Es are the pillars needed in a 21st century public administration that center care (empathy), meet people where they are (engagement), promote fairness for all (equity), and do so in ways to advance the public interest and public benefit (ethics).

In the first half of this special double-issue, we will be exploring multiple perspectives of these new pillars of public administration. In this article, we will define the former 3Es and then discuss what the 4Es are and what they mean for the future of our field. We end this essay with a summary of the articles in this special issue.

The traditional pillars of public administration: Economy, efficiency, and effectiveness

Traditionally in public administration, the 3Es (Economy, Efficiency, and Effectiveness) have been the go-to broad normative expectations for how public administration should operate. But what are they? provides a brief introduction to these three pillars. Economy focuses on the way public administrators work with scarce resources (Rosenbloom, Citation2005). Efficiency is used to explore how to get the greatest outcomes using the fewest resources (Norman-Major, Citation2011). Lastly, effectiveness explores how well a person or agency does the work it’s meant to do (Rainey & Steinbauer, Citation1999).

Table 1. The 3Es.

As these 3Es have been discussed in-depth elsewhere (see Norman-Major, Citation2011 for an analysis), we instead pivot to an important question: do these three pillars, economy, efficiency, and effectiveness, sufficiently address the needs and work of modern public administration? These pillars have a long history within the field of public administration, such as being included in White’s 1955 textbook on public administration (Yang & Holzer, Citation2005), and as separate concepts. But these pillars have been malleable over time. A full history of the 3Es is beyond this article, but a few examples of how the pillars of public administration have changed includes:

The pillars that Woodrow Wilson first proposed were centralization, economy, and efficiency. Effectiveness was added later on, taking the place of centralization (Newland, Citation1976; Yang & Holzer, Citation2005)

Rosenbloom (Citation2005) proposed that effectiveness and efficiency should be merged into one pillar due to their similarity.

Norman-Major (Citation2011) suggested adding equity as one of the pillars, creating 4Es instead of just three.

Norman-Major (2022) recently suggested that there should be 7 pillars of public administration, adding engagement, empathy, equity and ethics to economy, effectiveness, and efficiency.

Do public administrators find these pillars useful in their work? The research has found mixed results. For example, some research has identified that cultural contexts impact the importance of some of these pillars over others. When presenting an equity-efficiency trade-off, Fernández-Gutiérrez and van de Walle (Citation2019) reported that public administrators from Scandinavia are more likely to focus on equity while those from Southern Europe have an orientation toward efficiency. When asked to reflect on when, whether, and how public service values factor into their work, a sample of U.S. Midwestern public administrators ranked efficiency relatively low in importance as compared to other public service values (DeForest Molina & McKeown, Citation2012). Efficiency did rank 7th out of 38, with effectiveness being rated as 10th, of values identified in NASPAA self-study reports (Svara & Baizhanov Citation2019). Though these pillars are central to the field of public administration, they are not sacrosanct; they can be changed to meet the world in which public administrators live and work. Why should we change these pillars now? In the next section, we will explore this question in more depth.

Why do we need to rethink these pillars?

There are swelling income gaps, tensions among social, racial, and economic groups, which are further compounded by uneven access to health and education facilities across the globe. If these issues are left unattended, the income gap between the rich and the poor is likely to increase further. In addition, global warming is making the world unlivable, and is not impacting all parts of the world equitably. To respond to these issues, a new way of thinking is needed: a framework which focuses on empathy, engagement, equity, and ethics. These “new” four pillars provide public administrators with the skills needed to act in a way that is best for their constituents and the world (ethics), including those who may not always have a voice (equity), listening and supporting all communities in the ways that they want to be served (engagement) and understanding the complexities of the diverse world that these constituents live in (empathy).

This social inequality is not new. For example, American residents exposed to poverty in the 1960s included low-paid workers, female-headed families, rural residents, and minorities. Thanks to the Social Security benefits, the poverty rate among the elderly members of society had significantly decreased. However, social inequity was evident among rural and urban dwellers as of 1966. The poverty rate in the metropolitan regions was at 11% compared to 21% among rural Americans. In 1967, 32% of the low-income families had a breadwinner of the family who had full-time jobs, while 25% worked part-time jobs. Families that were headed by females were the poorest and comprised 11 million individuals. The poverty in female-headed families was caused by a lack of childcare and child-rearing responsibilities (Economic Research Service, Citation2022; Kenworthy & Marx, Citation2017; Proctor & Renwick, Citation2017).

Public administration should be concerned with justice, and all individuals should be treated equally and be accorded what they deserve at any single moment. As Guy and Ely (Citation2018) note, public administration’s primary normative duty is to improve people’s lives. This is where the 4Es excel. Again, this conversation is not new with some working in this space for decades (Gooden, Citation2017; Williams, Citation1947), raising important questions, like: What do people deserve; who decides; how do administrative decision-making process intersect with other values? These questions evoke the realities of administrative evil, namely that administrators can act within their professional roles yet remain unaware of committing harm and destruction, especially through dehumanization, treating some populations as “less” than others, and implementing discriminatory, marginalizing and, indeed, lethal policies (Adams et al., Citation2019). Guiding values center the broad goal of improving people’s lives are needed (Guy & Ely, Citation2018), yet it is incumbent on the field to remember that administrative values are themselves socially constructed, meaning that it matters not only how these values are defined but also who defines the values (McCandless & Blessett, Citation2022). Thus, empathy, engagement, equity, and ethics are needed because without them, public administration is not able to fulfill its highest mandate to improve people’s lives.

So how does the field of public administration do this? The 4Es allows the field to provide better supports and services and break down barriers for marginalized communities. Equity needs engagement. Engagement needs empathy. Ethics must guide all administrative and policy actions. To discuss and act upon one mandate discussing and acting upon the others. These values obtain their meaning and promise through working together. In the next section, we will explore these 4Es in more depth.

Moving the field forward: Empathy, engagement, (social) equity, & ethics

What are these new 4Es? Clearly, empathy, engagement, (social) equity, and ethics are not new ideas for the field of public administration. What is new is centering them in our field. We are proposing that these 4Es should be central to the way public administration is taught, researched, and practiced. In this section, we will look at the history and definitions of these four pillars, which can also be found in . Though some of these pillars have a long history (e.g., equity), others are relatively new to the field of public administration or are not as well-developed (e.g., empathy). Through this discussion, we will show how these 4Es are contextualized in public administration.

Table 2. The new pillars.

Social equity

Social equity generally refers to “fairness” and includes dimensions of due process, equal protection, and more (Johnson, Citation2017). Up until the 1960s, few authors wrote on the need for fairness for all (especially concerning racial equity), with rare exceptions like Frances Harriet Williams (Citation1947) who wrote on minority groups and the Office of Price Administration (OPA) (Gooden, Citation2017), and Philip Rutledge who encouraged equity to be included in both the ASPA code of ethics as well as the National Academy of Public Administration (Fredrickson, Citation2010). In the late 1960s and 1970s, social equity entered the lexicon through becoming a core tenet of New Public Administration (NPA). (Frederickson, Citation2010), and from the 1970s onward, social equity research grown slowly but substantially (Johnson, Citation2017). In the early 21st century, the National Academy of Public Administration (NAPA) provided the most commonly used definition: “The fair, just and equitable management of all institutions serving the public directly or by contract, and the fair and equitable distribution of public services, and implementation of public policy, and the commitment to promote fairness, justice, and equity in the formation of public policy” (as cited in Wooldridge & Bilharz, Citation2017). This definition by NAPA has helped guide the field in its search for equity in public administration.

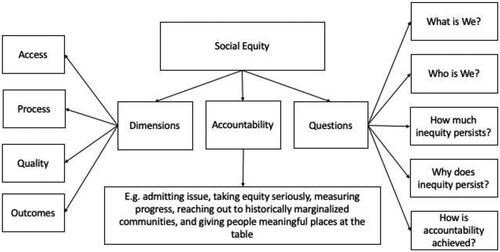

Three frameworks help parse social equity’s meaning. First, social equity has at least four major dimensions, namely that equity consists of: (a) access (i.e., the availability of a service); (b) processes (i.e., the fairness of how something is produced, especially from a procedural justice standpoints); c) quality (i.e., how good or useful a service is); and (d) outcomes (i.e., longitudinal consequences) (Johnson & Svara, Citation2015a). The reality is that for any one issue, these dimensions overlap significantly (Guy & McCandless, Citation2021). Second, Gooden (Citation2015) noted that social equity can be understood in terms of five central questions: (a) what is the context of the “We,” or that understanding social equity requires understanding protections embedded in founding documents like the U.S. Constitution; (b) who is “We,” or understanding how understandings of “We” have expanded over the decades; (c) how much inequity exists; (d) why does inequity persist (especially causes ranging from individual-level prejudice to systemic injustices); and (e) how accountability for social equity is achieved. Third, accountability for social equity refers to what governments can do to take equity more seriously, such as admitting issue, taking equity seriously, measuring progress, reaching out to historically marginalized communities (note the overlap with engagement), and giving people meaningful places at the table (Johnson & Svara, Citation2015b). We have merged this into one framework for social equity, found in .

Equity theory suggests that individuals feel most contented when they obtain what they deserve from their associations; no less or certainly no more. Equity theory encompasses four propositions. The first proposition is that all individuals from all genders naturally attempt to minimize pain and maximize pleasure. The second proposition suggests that society has consigned interest in convincing individuals to behave equitably and fairly (Ryan, Citation2016). Generally, groups are inclined to recognize members who consider others equitably and reprimand those who treat others unfairly or inequitably. The third proposition suggests that given societal pressures, individuals are most contented when they notice that they are receiving roughly what they merit from love and life. If they feel over benefited, they may feel a form of guilt, pettiness, and shame (2016 Equity Theory). In the same case, if they are underprivileged, they may feel anger, sadness, and some form of resentment. Finally, the fourth proposition implies that individuals in equitable associations will try to minimize their distress through various techniques like reestablishing psychological equity, tangible equity, or quitting the relationship (2016 Equity Theory).

Ethics

Ethics refer to moral principles governing behavior and are cornerstones of professions as shown in their codes of ethics (Svara, Citation2015). Perhaps the most commonly cited underpinning for ethics in the field, however, is public interest, or that administrators must act in ways that advance public benefit versus serving particularized interests (Cooper, Citation2004), as is codified in the ASPA code of ethics.

Given ongoing crises in government, it is incumbent on the field to better discuss ethics (Elias & Olejarski, Citation2020). Public administration ethics have numerous normative foundations (Cooper, Citation2004). For instance, ethical underpinnings are evident in regime values, constitutional theory, and founding thought. Ethical underpinnings are also evident in terms of citizenship theory, or the need for administrators to treat its primary stakeholders and citizens, as well as in virtue ethics, or promoting individual and agency-level honesty and morality. Ethics can be focused on many aspects of public administration, including environmentalism, technology, and consumerism (Zavattaro, Citation2021).

Revealingly, public administration ethics and professional standards are aspirational and action-oriented, in that they both highlight desired behaviors while encouraging particular actions (Plant, Citation2015; Svara, Citation2015). In the code of ethics of the American Society for Public Administration (ASPA, 2021), for instance, the first value is “Advance the Public Interest,” or “[promoting] the interests of the public and [putting] service to the public above service to oneself.” This value follows other people and action-oriented values, such as upholding the Constitution and the laws, promoting democratic participation, promoting ethical organizations, and more. As documented in ASPA’s guide to implementing the code of ethics, such ethical guides are meant not only to reduce bad behavior but also to promote good behavior (Svara et al., Citation2015).

Empathy

In certain ways, empathy is a somewhat newer concept in the public administration literature, and its place as a value in the field is somewhat undefined (Edlins, Citation2021). As can be the case in any field, historical myopathy can cloud institutional memory, meaning that “new” and “recently discovered” concepts likely were discussed by earlier, under-acknowledged pioneers (see Burnier, Citation2008, Citation2021b). Foundational figures like Jane Addams treated empathy, compassions, and care as interchangeable and, indeed, necessary for fruitful public administration, which should focus on addressing human needs (Addams, 1902/Citation2002).

At a minimum, empathy refers to the ability to understand and share the feelings of another; administrators should have the ability to understand and share the feelings of the populations they serve. Empathy concerns not only fulfilling rules but treating people with whom administrators act as whole people (Burnier, Citation2021a; Dolamore, Citation2021). This notion is somewhat in contrast to classical public administration’s focus on technical, neutral rationality, namely viewing people from primarily input-to-output behaviors (i.e., that people are affected by stimulus and response) and a growing recognition that understanding of human behavior requires understanding the roles of cognition and emotion (Dolamore et al., Citation2021; Guy et al., Citation2014; Portillo et al., Citation2020).

Still, empathy is comparatively better understood and woven throughout in other fields. For instance, nursing places a premium on the medical profession fostering empathy (see Texas A&M International University, Citation2022). Patients, for instance, can feel overwhelming, even terrifying emotions throughout medical procedures. Empathy extends beyond tending to traditional markers of health–vital signs and symptoms–and into treating patients as full beings with numerous needs. Empathy is a critical component of quality care in that it builds communication, understanding, and trust.

This example from nursing informs public administration. For instance, a common theme evident in the inequities committed by public administration is socially constructing entire populations as deviant (Gaynor, Citation2018; Ingram et al., Citation2007). There is little room for appreciating, valuing, listening to, and acting on the experiences and concerns of populations labeled with such constructions (Blessett, Citation2015; Gaynor & Blessett, Citation2021; Humphrey, Citation2021; Portillo et al., Citation2020), which is problematic given that public administration is a relational, people-centered enterprise (Burnier, Citation2008, Citation2021a; Guy & Ely, Citation2018).

Engagement

Of the new 4Es, engagement has perhaps the most voluminous literature. Engagement refers to the reality that administrators can and must be public facing and that their work is not solely encapsulated by classic aphorisms like POSDCORB (planning, organizing, staffing, directing, coordinating, reporting, budgeting) (Gulick, Citation1937). More directly, engagement is an umbrella term for bringing people together to address issues of importance (Nabatchi & Amsler, Citation2014). It is associated with numerous other terms, such as citizen engagement, civic engagement, community engagement, public administration, deliberative democracy, and more. Engagement is most democratic when it refers to direct public engagement, or when administrators engage people personally rather than through others like representatives or proxies. Any type of direct engagement consists of numerous factors and considerations, such as: (a) those who are involved (i.e., sponsors, conveners, and stakeholders as well as their respective motivations for direct public engagement); (b) how processes are designed; and (c) the outcomes associated with engagement, like impacts on individual participants, community capacity, and government and governance (Nabatchi & Amsler, Citation2014).

The need for public administrators to be engaged is a central piece of new public service [NPS] (Denhardt & Denhardt, Citation2015). NPS supporters argue, in distinction from other frameworks like new public management and even classical administration, that administrators must actively engage citizens to promote democratic decision-making. NPS principles include: serve citizens, not customers; seek the public interest; value citizenship and public service above entrepreneurship; think strategically, act democratically; recognize that accountability is not simple; serve, rather than steer; value people, not just productivity (Denhardt & Denhardt, Citation2015). Additionally, administrators must keep in mind how those with whom they engage are a broader group than simply “citizens” (which has a distinct meaning of legal recognition) and include persons who are permanent residents and those without protected legal status (Roberts, Citation2021).

Bringing it all together: Four pillars, one focus

In this first half of the double special issue, we are presenting one way to move the field of public administration forward. By focusing on empathy, equity, ethics, and engagement, we are suggesting that public administrators should be exploring ways that they can better all communities, including vulnerable communities which are forgotten. In this special double issue, we will be presenting work which will show not only why these four pillars are important for public administration, but how they can be used in research, teaching, and practice.

Articles in this section

Heckler and Mackey (Citation2022) in “COVID’s Influence on Black Lives Matter: How Interest Convergence Explains the 2020 Call for Equality and What That Means for Administrative Racism” use interest convergence to explore the 2020 resurgence of the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement. Employing an autoethnographic approach, the authors explore how, instead of aiming for cultural competency, public administration can use cultural humility to understand cultural contexts, strengths, and needs.

Dolamore and Whitebread (Citation2022), in “Recalibrating Public Service: Valuing Engagement, Empathy, Social Equity, and Ethics in Public Administration,” use interviews with American Sign Language (ASL) interpreters to explore the 4Es within public service. Dolamore and Whitebread find that ASL interpreters often use all four of these Es to guide their work. Building on this, the authors recommend updating the American Society of Public Administrators (ASPA) code of ethics, last updated in 2014, to provide guidance for public administrators.

Fenley (Citation2022) provides a critical lens on empathy in her article “Caveats to Governing With Empathy.” Fenley presents three types of interactions which can be unintentionally bad when using empathy: filtered empathy, false empathy, and power and inequality within empathetic interactions. Through this analysis, Fenley is able to provide feedback to the field of public administration in how empathy can go wrong and furthers our understanding of empathy within areas of public administration such as citizen-state interactions, marketing, and developing knowledge and skills.

Atkinson, Alibašić, and Oduro Nyarko’s (Citation2022) in “Diversity Management in the Public Sector for Sustainable, Inclusive Organizations: Ideals and Practices in Northwest Florida” examine diversity management through a social equity lens. Through semi-structured interviews, Atkinson and colleagues ask what creates effective and ineffective diversity management and social equity programming. While they find that there is much signaling around diversity, there is little evaluation of diversity efforts or engagement in a more meaningful way. Through this article, recommendations are made on how to create effective diversity management.

Lastly, Wright Field and Conyers (Citation2022) present “An Argument for Administrative Critical Consciousness in Public Administration.” Administrative Critical Consciousness (ACC) is a way for administrators and leaders in public administration to assess inequality in organizations using skills such as engagement and empathy. Using all of the four Es, Wright Field and Conyers present ACC as a way to enact these new 4Es within public administration and provides a framework for how leaders can dismantle oppressive structures within the field.

Conclusion

In a post COVID-19 pandemic world, the question needs to be asked: what is the role of public administration? Specifically, what do we want the field to look like in the future, and what pillars do we want to use to guide students, practitioners, and researchers of public administration. In this essay and special double issue, we propose that the way forward is through engagement, empathy, ethics, and equity. These 4Es can help provide important perspectives to “wicked problems” of the field and provide the knowledge and skills our students need to be public administrators in this unequal society. As the field considers the reality of a world where growing discussions around inequality, decolonization, technology, and globalization is being tackled head on by public and nonprofit organizations, engagement, empathy, ethics, and equity will be key to moving the field into the 21st century.

References

- Adams, G. B., Balfour, D. L., & Nickels, A. (2019). Unmasking administrative evil (5th ed.). Routledge.

- Addams, J. (2002). Democracy and social ethics. University of Illinois Press. (Original work published 1902)

- Alkadry, M. G., & Blessett, B. (2010). Aloofness or dirty hands? Administrative culpability in the making of the second ghetto. Administrative Theory & Praxis, 32(4), 532–556. https://doi.org/10.2753/ATP1084-1806320403

- American Society for Public Administration (ASPA). (2022). Code of ethics. Retrieved from: https://www.aspanet.org/ASPA/Code-of-Ethics/ASPA/Code-of-Ethics/Code-of-Ethics.aspx?hkey=5b8f046b-dcbd-416d-87cd-0b8fcfacb5e7

- Atkinson, C. L., Alibašić, H., & Oduro Nyarko, E. (2022). Diversity management in the public sector for sustainable, inclusive organizations: Ideals and practices in Northwest Florida. Public Integrity, 2022, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/10999922.2022.2034339

- Blessett, B. (2015). Disenfranchisement: Historical underpinnings and contemporary manifestations. Public Administration Quarterly, 39(1), 3–50.

- Burnier, D. (2008). Frances Perkins’ disappearance from American Public Administration: A genealogy of marginalization. Administrative Theory & Praxis, 30(4), 398–423. https://doi.org/10.1080/10841806.2008.11029660

- Burnier, D. (2021a). Embracing others with “sympathetic understanding” and “affectionate interpretation: Creating a relational care-centered public administration. Administrative Theory & Praxis, 43(1), 42–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/10841806.2019.1700460

- Burnier, D. (2021b). Hiding in plain sight: Recovering public administration’s lost legacy of social justice. Administrative Theory & Praxis, 43(4), 395–411. https://doi.org/10.1080/10841806.2021.1891796

- Cooper, T. L. (2004). Big questions in administrative ethics: A need for focused, collaborative effort. Public Administration Review, 64(4), 395–407. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2004.00386.x

- DeForest, Molina, A., & McKeown, C. L. (2012). The heart of the profession: Understanding public service values. Journal of Public Affairs Education, 18(2), 375–396. https://doi.org/10.1080/15236803.2012.12001689

- Denhardt, J. V., & Denhardt, R. B. (2015). The new public service: Serving, not steering. Routledge.

- Dolamore, S. (2021). Detecting empathy in public organizations: Creating a more relational public administration. Administrative Theory & Praxis, 43(1), 58–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/10841806.2019.1700458

- Dolamore, S., & Whitebread, G. (2022). Recalibrating public service: Valuing engagement, empathy, social equity, and ethics in public administration. Public Integrity, 2022, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/10999922.2021.2014223

- Dolamore, S., Lovell, D., Collins, H., & Kline, A. (2021). The role of empathy in organizational communication during times of crisis. Administrative Theory & Praxis, 43(3), 366–375. https://doi.org/10.1080/10841806.2020.1830661

- Economic Research Service. (2022). Rural poverty & well-being. U.S. Department of Agriculture. https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/rural-economy-population/rural-poverty-well-being/

- Edlins, M. (2021). Developing a model of empathy for public administrations. Administrative Theory & Praxis, 43(1), 22–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/10841806.2019.1700459

- Elias, N. M., & Olejarski, A. M. (Eds.). (2020). Ethics for contemporary bureaucrats: Navigating constitutional crossroads. Routledge.

- Fenley, V. M. (2022). Caveats to Governing with empathy. Public Integrity, 2022, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/10999922.2021.2015163

- Fernández-Gutiérrez, M., & Van de Walle, S. (2019). Equity or efficiency? Explaining public officials’ values. Public Administration Review, 79(1), 25–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12996

- Frederickson, H. G. (2010). Social equity and public administration: Origins, developments, and applications. Routledge.

- Garcia-Sanchez, I. M., Cuadrado-Ballesteros, B., & Frias-Aceituno, J. (2013). Determinants of government effectiveness. International Journal of Public Administration, 36(8), 567–577. https://doi.org/10.1080/01900692.2013.772630

- Gaynor, T. S. (2018). Social construction and the criminalization of identity: State-sanctioned oppression and an unethical administration. Public Integrity, 20(4), 358–369. https://doi.org/10.1080/10999922.2017.1416881

- Gaynor, T. S., & Blessett, B. (2021). Predatory policing, intersectional subjection, and experiences of LGBTQ people of color in New Orleans. Urban Affairs Review, 2021, 107808742110172. https://doi.org/10.1177/10780874211017289

- Gooden, S. T. (2014). Race and social equity: A nervous area of government. Routledge.

- Gooden, S. T. (2015). From equality to social equity. In M.E. Guy & M.M. Rubin (Eds.), Public administration evolving: From foundations to the future. (pp. 210–230). Routledge.

- Gooden, S. T. (2017). Frances Harriet Williams: Unsung social equity pioneer. Public Administration Review, 77(5), 777–783. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12788

- Gulick, L. H. (1937). Notes on the theory of organization. In L. Gulick & L. Urwick (Eds.), Papers on the science of administration (pp. 3–45). Institute of Public Administration.

- Guy, M. E., & Ely, T. L. (2018). Essentials of public service: An introduction to contemporary public administration. Melvin & Leigh.

- Guy, M. E., & McCandless, S. A. (2021). Achieving social equity: From problems to solutions. Melvin & Leigh.

- Guy, M. E., Newman, M. A., & Mastracci, M. (2014). Emotional labor: Putting the service in public service. Routledge.

- Hammond, T. H. (1990). In defense of Luther Gulick’s Notes on the theory of organization. Public Administration, 68(2), 143–173. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.1990.tb00752.x

- Heckler, N., & Mackey, J. (2022). COVID’s Influence on Black Lives matter: How interest convergence explains the 2020 call for equality and what that means for administrative racism. Public Integrity, 2022, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/10999922.2021.2014203

- Humphrey, N. M. (2021). Emotional labor and professionalism: Finding balance at the local level. State and Local Government Review, 53(3), 260–270. https://doi.org/10.1177/0160323X211048847

- Ingram, H., Schneider, A. L., & DeLeon, P. (2007). Social construction and policy design. In P. Sabatier (Ed.), Theories of the Policy Process. (2nd Ed., pp. 93–126). Westview Press.

- Johnson, N. J., & Svara, J. H. (2015a). Social equity in American society and public administration. In N. J. Johnson & J. H. Svara (Eds.), Justice for all: Promoting social equity in public administration (pp. 3–25). Routledge.

- Johnson, N. J., & Svara, J. H. (2015b). Toward a more perfect union: Moving forward with social equity. In N. J. Johnson & J. H. Svara (Eds.), Justice for all: Promoting social equity in public administration (pp. 265–290). Routledge.

- Johnson, R. G. (2017). Social equity in a time of change: A critical 21st century social movement. Birkdale Publishers.

- Kenworthy, L., & Marx, I. (2017). In-work poverty in the United States. Bonn, Germany: IZA Institute of Labor Economics. Retrieved from: https://docs.iza.org/dp10638.pdf.

- McCandless, S. A., & Ronquillo, J. C. (2020). Social equity in professional codes of ethics. Public Integrity, 22(5), 470–484. https://doi.org/10.1080/10999922.2019.1619442

- McCandless, SA., & Blessett, B. (2022). Dismantling racism and white supremacy in public service organizations and society. Administrative Theory & Praxis, 2022, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/10841806.2022.2043071

- Nabatchi, T., & Amsler, L. B. (2014). Direct public engagement in local government. The American Review of Public Administration, 44(4_suppl), 63S–88S. https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074013519702

- Newland, C. A. (1976). Public personnel administration: Legalistic reforms vs. effectiveness, efficiency, and economy. Public Administration Review, 36(5), 529–537. https://doi.org/10.2307/974233

- Norman-Major, K. (2011). Balancing the four E s; or can we achieve equity for social equity in public administration? Journal of Public Affairs Education, 17(2), 233–252. https://doi.org/10.1080/15236803.2011.12001640

- Norman-Major, K. (2021). How Many Es? What must public administrators consider in providing for the public good? Public Integrity, 2021, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/10999922.2021.1967010

- Plant, J. F. (2015). Seventy-five years of professionalization. In M. E. Guy & M. M. Rubin (Eds.), Public administration evolving: From foundations to the future (pp. 232–253). Routledge.

- Portillo, S., Bearfield, D., & Humphrey, N. (2020). The myth of bureaucratic neutrality: Institutionalized inequity in local government hiring. Review of Public Personnel Administration, 40(3), 516–531. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734371X19828431

- Proctor, B., & Renwick, T. (2017). 50 years of poverty statistics. U.S. Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/blogs/random-samplings/2017/09/50_years_of_poverty.html

- Rainey, H. G., & Steinbauer, P. (1999). Galloping elephants: Developing elements of a theory of effective government organizations. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 9(1), 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.jpart.a024401

- Roberts, A. S. (2021). Who should count as citizens? Categorizing people in public administration research. Public Administration Review, 81(2), 286–290. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13270

- Rosenbloom, D. (2005). Taking social equity seriously in MPA education. Journal of Public Affairs Education, 11(3), 247–252. https://doi.org/10.1080/15236803.2005.12001397

- Ryan, J. (2016). Strategic activism, educational leadership and social justice. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 19(1), 87–100.

- Svara, J. H., & Baizhanov, S. (2019). Public service values in NASPAA programs: Identification, integration, and activation. Journal of Public Affairs Education, 25(1), 73–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/15236803.2018.1454761

- Svara, J., Braga, A., de Lancer Julnes, P., Massiah, M., S. Ward, J, G., Shields, W. (2015). Implementing the ASPA Code of Ethics: Workbook and assessment guide. Retrieved from: https://www.aspanet.org/ASPADocs/Resources/Ethics_Assessment_Guide.pdf

- Svara, J. H. (2014). Who are the keepers of the code? Articulating and upholding ethical standards in the field of public administration. Public Administration Review, 74(5), 561–569. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12230

- Svara, J. H. (2015). From ethical expectations to professional standards. In M. E. Guy & M. M. Rubin (Eds.), Public administration evolving: From foundations to the future (pp. 254–273). Routledge.

- Texas A&M International University. (2022). Why empathy is crucial in nursing. Retrieved from: https://online.tamiu.edu/articles/rnbsn/empathy-is-crucial-in-nursing.aspx

- Turner, H. A. (1956). Woodrow Wilson as administrator. Public Administration Review, 16(4), 249–257. https://doi.org/10.2307/973137

- Williams, F. H. (1947). Minority groups and the OPA. Public Administration Review, 7(2), 123–128. https://doi.org/10.2307/972754

- Wooldridge, B., & Bilharz, B. (2017). Social equity: The fourth pillar of public administration. In A. Farazmand (Ed.), Global encyclopedia of public administration, public policy, and governance. Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-31816-5_2383-1

- Wright Fields, C., & Conyers, A. (2022). An argument for administrative critical consciousness in public administration. Public Integrity, 2022, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/10999922.2022.2034340

- Yang, K., & Holzer, M. (2005). Re-approaching the politics/administration dichotomy and its impact on administrative ethics. Public Integrity, 7(2), 110–127.

- Zavattaro, S. M. (2021). We’ll see who’s powerless now! Using WALL-E to teach administrative ethics. Public Integrity, 2021, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/10999922.2021.1985344