Abstract

The growth of East-Asian scholars in the American public affairs and administration (PA) field is increasingly apparent in recent years. Their participation demonstrates the diversity of the academic community and the globalization of higher education. However, little attention has been paid in the literature to this minority. From the broader perspective, Asian minorities have been overlooked in the discourse on diversity, equity, and inclusion, although they certainly confront social challenges such as inequity, injustice, discrimination, xenophobia, and even hate crimes. Our research attempts to address this gap in the literature by objectively documenting the participation and contributions of East-Asian scholars (EASs) to the American PA field. We find that across the top 100 PA schools, approximately 5% of the total full-time faculty members are East-Asian scholars, and that almost 20% of the peer-reviewed articles published in the top 10 PA journals are contributed by that scholarly community. However, the representation of East-Asian scholars in journal and association leadership teams remains low, which does not rise to their level of their contributions via peer-reviewed journal articles.

Introduction

Our research attempts to document the participation and contributions of East-Asian scholars (EASs) to the American public affairs and administration (PA) field in the discourse on diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) as well as globalization of higher education. East Asia mainly consists of China, South Korea, Japan, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Singapore, Vietnam, and Thailand. We define EASs as those who are East-Asian Americans or those with East-Asian nationality participating in teaching, research, or service in the American PA community, regardless of whether they were born in East Asia, the United States, or other regions. We focus on the East-Asian group rather than the entire Asian community because East-Asians are racially similar, they largely share the same cultures and customs, and they face similar challenges while they engage in the American society.

The number of EASs in the American PA field has apparently increased in recent years. Such growth not only demonstrates diversity of the academic community but also showcases the globalization of higher education. However, little attention has been paid in the literature to this minority as a contributing group. In the larger picture, Asian minorities have been overlooked in the discourse on DEI, although they confront various social challenges such as inequity, injustice, discrimination, xenophobia, and even hate crimes.

We address two questions in this article: First, what is the size of the East-Asian scholars’ community in American PA programs and academic networks? Second, what are their contributions to scholarly research and scholarly services? We also provide suggestions for future research at the end of the article. Our foundational assumption is that the participation of East-Asian scholars in the American PA field reflects historical changes in diversity, race, and globalization.

Diversity and race

Diversity is a multi-faceted concept which presents demographic differences across race/ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, faith and spirituality, class and equity, ageism, culture and language, and disabilities (Carrizales & Gaynor, Citation2013). Caleb (Citation2014) and Martin (Citation2014) focus on cultural diversity, which is associated with race, ethnicity, gender, age, sexual orientation, etc., and have analyzed negative and positive effects of diversity in the business workplace. They illustrated that, if poorly managed, diversity in a group can cause discomfort, lower communication, miscommunication, a lack of trust, greater perceived interpersonal conflict, dysfunctional adaptation behaviors, less cohesion, more concern about disrespect, and related problems. These problems may hinder the development of unity and cause interpersonal conflict, which further results in low productivity and negative morale among employees. Therefore, diversity could be detrimental to an organization if not appropriately managed.

However, the positive effects of diversity are also evident and present distinct advantages for improving organizational performance. Caleb (Citation2014) argued that a diverse group is more innovative than a homogeneous group, not only due to new information contributed by people with different backgrounds, but also because interacting with individuals who are different from themselves forces individuals to think in more depth and to anticipate alternative viewpoints, all the while encouraging efforts to reach consensus. Similarly, Martin (Citation2014) stated that an organization can benefit from its diverse workforce because employees with different cultures and experiences can provide the organization with a sound and vast knowledge base. Martin (Citation2014) also pointed out that cultural diversity can help a company overcome culture shock as it expands in other countries.

In the public sector, organizations have experienced stable increases in workforce diversity over the last decades (Sabharwal et al., Citation2018). Scholars in public administration may well embrace diversity more positively than their colleagues in other disciplines. They view diversity from perspectives of social justice, equity, inclusion and representative democracy, and take it as an important public value, parallel to those of efficiency and economy (e.g., Broadnax, Citation2010; Carrizales & Gaynor, Citation2013; Frederickson, Citation2005; Riccucci & Van Ryzin, Citation2017; Sabharwal et al., Citation2018). According to Sabharwal et al. (Citation2018), who comprehensively reviewed articles on issues of diversity published in seven public administration journals from 1940 to 2013, various dimensions of diversity—including race/ethnicity, gender, AA/EEO, representative bureaucracy, age, disability, religion, socioeconomic status (SES), sexual orientation, immigration and generations—have been investigated in the literature, while race has been the most researched topic. Sabharwal et al. (Citation2018) explained that race or inequality toward minorities has remained a severe problem facing our society. For instance, the concentration of poor African Americans in low-income urban areas has had a spiraling effect on inequality as they lack access to basic opportunities, such as good schools, jobs, transportation, housing, and safety (Frederickson, Citation2005). Frederickson (Citation2005) exhorted that “If politics is all about majority rule—and it is—then public administration should be all about seeing after the interests of minorities and the poor” (p. 38). As for the workforce in the public sector, Hewins-Maroney and Williams (Citation2013) suggested that public administrators worldwide have a pivotal role in overcoming challenges to successfully managing diversity and achieving productive employment.

Diversity in the public workforce reflects bureaucratic representation, especially passive representation. Mosher (Citation1968) distinguished two types of representation—passive and active. The former refers to the proportion of individuals in a public entity, by demographic categories, that mirrors the total society the public entity serves. Active representation refers to the extent to which individuals in a public entity make efforts to promote the interests of a population they are presumed to represent. Public administration scholars have underscored findings that passive representation produces multiple benefits in the public sector (e.g., Hong, Citation2017; Lim, Citation2006; Riccucci & Van Ryzin, Citation2017). For example, Riccucci and Van Ryzin (Citation2017) suggested that a passively represented bureaucracy in a public entity, even as merely symbolic representation regardless of bureaucratic actions or results, can itself improve public service outcomes by influencing the attitudes and behaviors of their clients. Using data from English and Welsh police forces, Hong (Citation2017) empirically discovered that an increase in passive representation of a police force that reflects the community it serves can significantly reduce police misconduct and enhance organizational integrity; it can also improve police attitudes and behaviors toward minority citizens, and thus increase the overall satisfaction among minority constituents.

If we extend our discussion to higher education or academia, does the diversity of faculty also matter? Scholars have raised concerns about the lack of faculty diversity at American universities. For instance, Cole and Barber (Citation2003) investigated college students’ career paths and addressed the concern as to why minority students are less likely to become college professors compared to white students. Wooldridge and Rubin (Citation2000) particularly uncovered the shortage of minority faculty in public affairs programs. Farmbry (Citation2007) also focused on public administration education and explored barriers that might prevent minority doctoral students, the future faculty candidates in the field, from completing their programs.

Indeed, education for diversity and diversity management in public administration programs is crucial. Scholars have advocated not only for teaching social equity and diversity in public administration curricula, but also for making a concerted effort to diversify—racially and ethnically—public administration faculty (Rice, Citation2004) and PhD students (Farmbry, Citation2007). They argued that addressing diversity in public administration classrooms, as well as in the published literature, will enhance awareness and appreciation of social equity and inclusion among students—the current and future public managers—and further change the culture of public organizations as their current and future employers. In return, social equity and inclusion will ultimately be promoted in the process of public service delivery and in the broad society. Thus, the literature has implied a critical role for PA educators/researchers in the processes of diversification, inclusion, and anti-discrimination (Cole & Barber, Citation2003; Rice, Citation2004).

Diversity and East-Asian scholars

While race is the most researched theme of diversity studies in public administration, a prevalent focus has been placed on Black and Hispanic minorities (e.g., Cole & Barber, Citation2003; Farmbry, Citation2007; Riccucci & Van Ryzin, Citation2017; Sabharwal et al., Citation2018; Wooldridge & Rubin, Citation2000). In frequent cases, the terms “minority,” “social equity,” and “diversification” by default refer to those minorities. That discourse is certainly reasonable and necessary in the American context with a long history of limiting opportunities for Black and Hispanic communities. Such scholarly discussion is expected to encourage policymakers and educational institutions to find effective ways of attracting more Black and Hispanic students to engage in higher education and pursue academic careers.

Nevertheless, it is also worthwhile to consider a broad picture of diversity by paying attention to other minority groups, such as Asian scholars. One important reason for examinations of minority or diversity issues is to draw attention to racism. History, and today’s reality, repeatedly remind us that Asian-Americans have been attacked as a function of racism, and have struggled with inequity, injustice, discrimination, xenophobia, and hate crimes in the United States. There have been repeated examples of large-scale racial discriminations against Asian-Americans throughout American history, including the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882; the San Francisco plague in 1900; Japanese internment camps during WWII; the attacks on Vietnamese shrimpers by the KKK in 1979; and the Los Angeles riots targeting Korean American businesses in 1992.

The COVID-19 pandemic, beginning in early 2020, further inflamed xenophobia against Asian-Americans. For instance, a mass shooting hate crime against Asian-Americans in Atlanta, Georgia on March 16, 2021, killed eight individuals, six of whom were women of Asian descent. In March 2022, a man committed a two-hour spree of attacks on seven women of Asian descent in Manhattan, none of whom was known by the assailant (Zraick, Citation2022). In the same month, a 67-year-old woman of Asian descent was fiercely bludgeoned by a man while she was entering her apartment in Yonkers, NY. After the attacker beat the woman to the ground, he pummeled her repeatedly with both hands, delivering more than 125 blows, followed by stomping on her seven times and spitting on her before walking away. According to a police report, the woman sustained broken bones in her face, bleeding on the brain and numerous cuts and bruises on her head and face. The Yonkers Police Commissioner said in a statement, “This is one of the most appalling attacks I have ever seen. To beat a helpless woman is despicable; and targeting her because of her race makes it more so” (Shanahan, Citation2022). From late December 2021 to late February 2022 in the city of New York, four people of Asian descent lost their lives to hate crimes. Yao Pan Ma died from his injuries on New Year’s Eve of 2022, eight months after he was beaten by a racist attacker. Michelle Alyssa Go was pushed to her death at the Times Square subway station in January 2022. In February 2022, Christina Yuna Lee was fatally stabbed by a man who followed her into her Chinatown apartment. And GuiYing Ma died of her injuries, two months after she was attacked as she swept a sidewalk in Queens, NY (Zraick, Citation2022). These brutal incidents once again reveal the existence of racial bigotry in modern society and that Asian-Americans are among the targeted victims of such bigotry.

As commented on in the Joint Statement in April 2020 by multiple sections of the American Society for Public Administration to condemn anti-Asian hate crimes (ASPA Section on Korean Public Administration, Citation2021), the United States has witnessed a rapid and unprecedented increase in anti-Asian hate during the COVID pandemic. While a complete dataset is not available at the federal government level, the Center for the Study of Hate & Extremism (CSUSB) at California State University, San Bernardino, reports a 149% surge in anti-Asian hate crimes in 2020 in the United States, while overall hate crimes dropped 7% (CSUSB, Citation2021). In 2021, anti-Asian hate crimes further increased by 339% over 2020 (Yam, Citation2022). The Stop AAPI Hate Reporting Center is a joint initiative launched by AAPI Equity Alliance, Chinese for Affirmative Action, and the Asian-American Studies Department of San Francisco State University on March 19, 2020. As of December 31, 2021, the Center had received reports of 10,905 hate incidents against Asian-Americans and Pacific Islanders (AAPI), with 4,632 incidents occurring in 2020 and 6,273 incidents in 2021 (Stop AAPI Hate, Citation2022).

Including Asian-American minorities and other minorities in the discourse on diversity, equity, and inclusion will enhance the social power of minorities to correct the systematic injustice and inequality for the entire society. The presence of Asian scholars, including East-Asian scholars in American universities, reflects such diversification, as well as the globalization of higher education in the United States.

Globalization and East-Asian scholars

Public affairs scholars have perceived a growing globalization process in higher education (e.g., Devereux & Durning, Citation2001; Knight, Citation2012, Citation2017; Ryan, Citation2010; Yang, Citation2009). That globalization has become a vital aspect of contemporary higher education, with the desired outcomes of international awareness and intercultural competence for graduates (Coelen, Citation2015). Beyond teaching and learning, globalization in higher education strengthens cross-border scholarship, research, and problem-solving because many such problems are global issues that require global cooperation, such as alleviating inequality and poverty, remedying food and employment insecurity, controlling diseases and pandemics, preserving the environment and countering global warming, and prioritizing world peace (Hser, Citation2005). In a global environment, graduates are likely to supervise or be supervised by people of racial and ethnic groups different from their own (Qiang, Citation2003). Therefore, on the demand side, globalization necessitates diversification of educators and administrators in higher education.

As a result of globalization, the number of international students in the United States has greatly increased over the last decades. According to the Institute of International Education (Institute of International Education [IIE], Citation2018), 1,094,792 international students enrolled in US colleges and universities in the fall of 2017. That number increased 75.5% from 2007 to 2017, and 127.5% from 1997 to 2017. The number of total international students slightly decreased in the fall of 2018 and the fall of 2019 (IIE, Citation2019), and then decreased to a greater extent, 16%, in the fall of 2020 due to COVID-19 (IIE, Citation2020). The IIE report reveals that more than 77% of the international students in the United States come from Asia, including China, India, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan. The largest number is from China, accounting for 33.2% of all international enrollments in the United States, followed by India with 17.9%, South Korea with 5.0%, and Saudi Arabia with 4.1% (IIE, Citation2018). By regions, East-Asia—including China, Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Japan—contributes the largest proportion of international students to American colleges and universities over the years. Some of those students have completed their doctoral studies in the United States and have been hired by American academic institutions as faculty members. Therefore, the globalization of higher education has significantly supplied East-Asian scholars to the United States. The following section will report on the data collection process for the documentation of East-Asian PA scholars’ participation in, and contributions to, the American public administration community.

Data collection

The researchers leading this study collected multiple datasets from various sources for this documentary work. First, we used US News Rankings in 2020 and identified the top 100 NASPAA-accredited schools in public affairs, and then visited the website of each school and identified East-Asian faculty members and the total number of faculty in the school. We acknowledge that the US News and World Report rankings for graduate programs are calculated on self-reported data and thus produce a degree of bias in the rankings. However, the top 100 schools listed by US News and World Report generally cover larger-sized programs and institutions, which better represent the mainstreams in PA education and discipline development than do their small-sized counterparts.

Second, we also selected a PhD program among the NASPAA-accredited schools and collected data of alumni from the first cohort of graduates (1997) to the most current one (2021) in order to ascertain the proportion of students from East Asia and their job placements. The program was selected because it has a relatively long history (since 1994) and can provide complete records for longitudinal job placements of its PhD graduates.

Third, we navigated the websites of major academic networks, including the American Society for Public Administration (ASPA), the Public Management Research Association (PMRA), the Network of Schools of Public Policy Affairs and Administration (NASPAA), and the Association for Public Policy Analysis and Management (APPAM) to collect data on the total number of scholars as well as the number of East-Asian scholars among conference participants and award winners in recent years.

Fourth, we used the Social Science Citation Index Rankings in 2020, identified the top 10 PA journals and computed their total number of peer-reviewed articles versus the number of articles authored or leading authored by East-Asian scholars. Finally, we visited websites of academic journals and associations for their leadership data.

During data collection, we relied on the spelling of last names to identify East-Asian scholars. In cases where it was hard to determine their demographic identities by the last name, we searched and reviewed their curriculum vitae online and tried to find relevant information from their educational and employment experiences. If profile photos were available online, we also took them as a reference.

The datasets we collected provide the possibility of measuring both the quantity and quality of EAS’s participation and their contributions in the American PA field. Since EASs are identified by their last names, the size of this minority group may be slightly undercounted because an EAS’s last name could be very rare and hard to identify, or it may change to an American-sounding last name for various reasons, such as marriage, and no document may be available to help identify their demographic origin. Consequently, the participation and contributions of East-Asian PA scholars might be underdocumented. Even with this potential limitation, the research, as the first documentary work for East-Asian PA scholars, will provide evidence to highlight the efforts and achievements of this relatively overlooked minority group in academia.

Findings

In this section, we review the participation, contributions, and representation of East-Asian scholars in teaching, research, and services in American public administration.

East-Asian faculty members in public affairs programs

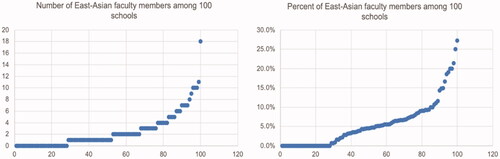

Among the 100 NASPAA-accredited top “schools” (a term that includes not only traditional schools, but institutes, programs and departments) by US News ranking in 2020, the total number of full-time faculty was 4,795, and the number of East-Asian faculty members was 247, in fall 2021. Hence, the overall share of East-Asian faculty is 5.15%. However, the variation is remarkable among the 100 schools. presents the variations in both number and percentage of East-Asian faculty members.

Among these 100 schools, 28 have no East-Asians among their full-time faculty, 52 schools have only one EAS, while 18 schools have 5 or more, and the largest number of EAS is 18 (the total number of faculty in that school is 237). The average number of East-Asian faculty members is 2.47. To better show the representation of East-Asian scholars, we calculated percentage as well. At the school level, the percentage of East-Asian faculty ranged from 0 to 27.27%, with the average at 5.62 and median at 4.62%. presents those statistics.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of East-Asian full-time faculty and tenured East-Asian faculty (N = 100 schools)

Among the total number of 247 East-Asian faculty members from 100 public affairs schools, 120, or 48.58% were tenured in fall 2021. As shown in , the share of tenured East-Asian faculty, out of the total tenured faculty, varies considerably across schools from 0 to 40%, with the average at 5.47% and the median at 2.20%. The share of tenured East-Asian faculty out of the total tenured faculty is slightly lower than the share of full-time East-Asian faculty out of the total full-time faculty, suggesting that the group of East-Asian faculty is relatively more junior than their colleagues.

A case study of a PhD program

In order to estimate the possible trend of EAS’s participation in PA schools as faculty members, the researchers obtained a longitudinal dataset of all PhD graduates with their demographic and employment information from one of the top schools. This PhD program has graduated 133 students with doctorates in public administration between 1997 and 2021. As shown in , among the 133 PhD graduates, 40 were from East-Asia, accounting for 30% of all graduates. Among the 93 non-East-Asian alumni, 42, or 45.2%, took tenure-track faculty positions after they graduated. Among the 40 East-Asian graduates, 33 or 82.5% started their careers with tenure-track faculty positions, including those outside of the United States. The data suggests that East-Asian PhD graduates are more likely to pursue research careers than other PhD graduates.

Table 2. Comparison of East-Asian PhD graduates with other PhD graduates

The percentage of East-Asian graduates who took a full-time position in the United States is only 47.5%, lower than that of other graduates (50.5%). Nevertheless, the East-Asian graduates who did not take academic positions in the United States took such positions in their home countries or other regions. From this sample, it is likely that East-Asian PhD students are more oriented to taking academic positions than their non-Asian colleagues. In addition, these East-Asian PhD graduates continue to engage in the American and global scholarly dialogues as conference speakers and published researchers in peer-reviewed journals.

Another observation from the longitudinal data of this particular PhD program is that the 93 non-East-Asian students completed their PhD program within 5.7 years on average, while the 40 East-Asian students completed their program within 5.1 years, on average. Hence, East-Asian PhD students in public administration are likely to graduate sooner than other students in the same cohort.

If the PhD program of the selection represents a general population of PhD programs in public administration to a high degree, we may predict that East-Asian faculty in American PA schools will slightly increase in the future.

Publications of East-Asian scholars

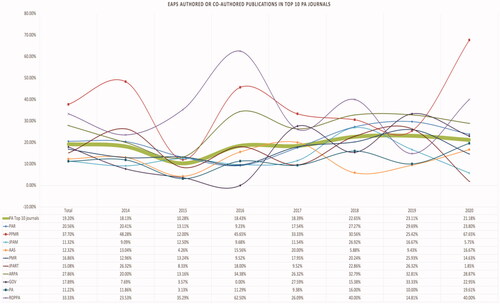

According to Social Science Citation Index Rankings in 2020, the top 10 public affairs journals are: Public Administration Review (PAR), Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory (JPART), Journal of Policy Analysis and Management (JPAM), Public Management Review (PMR), Administration and Society (AAS), The American Review of Public Administration (ARPA), Governance (GOV), Public Administration (PA), Public Performance & Management Review (PPMR), and Review of Public Personnel Administration (ROPPA). American PA scholars greatly participate in these journals through submissions and publications, reviewing manuscripts, and managing the journals.

We collected publication data for peer-reviewed articles in these journals from 2014 to 2020; the data for 2020 also incorporates online publications. Once again, we relied on last names for identifying East-Asian authors. The articles are counted as contributed by East-Asian scholars only if the sole or leading authors are East-Asian scholars. Because the journal submissions are broadly open to everyone, the East-Asian authors identified in these journals could be from everywhere in the world, not limited to the United States. Nevertheless, a large percentage of them is from the United States and/or earned degrees from US institutions. Taking publications in Public Administration Review (PAR) in 2020 as a small sample, the total number of published articles (including online publications) is 105; and 26 (24.8%) of them are sole-authored or leading authored by East-Asian scholars. Looking into the data more closely, we find that 13 (50%) of the 26 articles are sole-authored or leading authored by East-Asian scholars from US universities, 6 are contributed by scholars from mainland China, 4 belong to South Korean scholars, and another 3 are produced by East-Asian scholars from Taiwan, Singapore, and the Netherlands, respectively.

The 10 journals published a total of 3,338 articles over the 7 years, and 641 of them were authored or leading authored by East-Asian scholars, accounting for 19.20%. The share of publications by East-Asian scholars in these major PA journals is substantially higher than the share of East-Asian faculty in the top 100 PA schools in the United States (5.15%) because the former grouping contains East-Asian scholars from outside of the United States. Therefore, East-Asian scholars’ publications in the major PA journals somewhat overstates diversity or representations of East-Asian scholars in the American public administration. That is, the share of East-Asian scholars’ publications in these PA journals signifies the extent to which East-Asian scholars participate in the globalization of public affairs research.

reports the variation of East-Asian scholars’ publication shared across the 10 journals over 7 years from 2014 to 2020. First, the percentage of East-Asian scholars’ publications varies across journals. For instance, East-Asian scholars contributed 62.50% of peer-reviewed articles in Review of Public Personnel Administration (ROPPA) in 2016; but they published none in Governance in the same year. In 2019, East-Asian scholars published the lowest (9.43) percentage of articles in Administration and Society (AAS) and the highest (33.33) percentage in Governance. Over the seven years, Review of Public Personnel Administration (ROPPA), Public Performance Management Review (PPMR), and American Review of Public Administration (ARPA) were the top 3 journals among the 10 in publishing research products by East-Asian scholars. Meantime, also shows the fluctuation of their shares over time; the overall trend indicates that the percentage of articles by East-Asian scholars published in these ten journals has been steadily increasing. Of note, across all ten journals, the percentage of articles published by EAS expanded from less than 20% before 2018 to over 20% after 2018, suggesting that East-Asian scholars’ participation in the globalization of public affairs research has enhanced over the years.

In addition to the above-mentioned data, we also included the case of the Chinese Public Administration Review (CPAR), which is the official journal of the Section on Chinese Public Administration (SCPA) at ASPA. The journal represents a critical part of scholarly contributions to the American PA field by diversifying the intellectual and cultural foundations of PA research. Authors from East-Asian countries and regions, and EAS in the United States, contributed the majority of CPAR publications from 2002 to 2019 in this journal (Lu et al., Citation2019).

East-Asian scholars’ leadership role in major PA journals

East-Asian scholars’ leadership roles, however, have not grown at the same pace as their contributions to publications. Using the data of editorial board membership collected from each journal website in 2021, we measured leadership by the number and percentage of editorial board members. As shown in , the Journal of Policy Analysis and Management (JPAM) and Administration and Society (AAS) have no EAS members on their editorial boards, although East-Asian scholars contributed a considerable number of accepted articles to JPAM, ranging from 9.09% to 26.92%, and to AAS ranging from 4.26 to 20.00% in 2014–2020 as reported in . Other journals have 3–13 East-Asian scholars on their editorial boards, accounting for 3.57 to 21.31% of the total editorial seats, with the highest representation, 21.31%, of East-Asian scholars, at Public Administration (see ). The overall percentage of East-Asian members on all journal editorial boards is 8.22%, which is much lower than the 19.20% share of articles authored by East-Asian scholars published in these journals in 2014–2020.

Table 3. Journal editorial board and the share of East-Asian members

We also note that more East-Asian scholars are beginning to lead journals. For example, Kaifeng Yang is the editor-in-chief of Public Performance and Management Review; Elaine Yi Lu was recently appointed as the Editor of the International Journal of Public Administration; Chao Guo is the editor-in-chief of Nonprofit & Voluntary Sector Quarterly; Hai (David) Guo is serving as the co-managing editor of the Journal of Public Budgeting, Accounting & Financial Management; and Chih-Wei Hsieh is an Associate Editor for Public Administration.

East-Asian scholars’ participation in conferences and associations

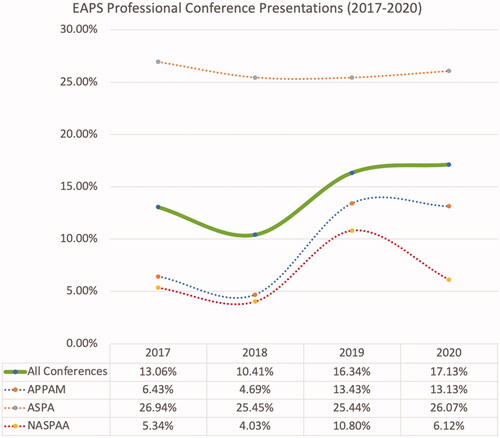

East-Asian scholars have actively participated in academic conferences and have won a substantial portion of awards from the associations. reveals the percentage of conference presentations delivered by East-Asian scholars out of total conference presentations in the three major annual conferences—ASPA, APPAM, and NASPAA—from 2017 to 2020. Overall, the share of conference presentations made by East-Asian scholars has increased from less than 15% before 2018 to over 15% after 2018. In 2020, East-Asian scholars made 17.13% of presentations at those three conferences. We also find great variation of East-Asian scholars’ participation across conferences. ASPA conferences have successfully attracted East-Asian scholars, and more than 25% of the conference presentations have been delivered by East-Asian scholars since 2017. Comparatively, East-Asian scholars’ participation in NASPAA conferences has remained the lowest among these three conferences, with the percentage of presentations between 4.03 and 10.8%.

Figure 3. East-Asian scholars’ presentations in academic conferences (2017–2020). ASPA 2020 conference was canceled due to COVID-19. Accepted manuscripts were presented at the 2021 conference. The 2020 ASPA number in this figure refers to the 2021 presentations.

East-Asian scholars have received considerable awards for their merit in research, teaching, and service from academic associations including APPAM, ASPA, NASPAA, and PMRA from 2017 to 2021 as shown in . Many of the annual best paper awards have been presented to East-Asian scholars. For instance, Lisa T. Quan and her co-authors won the Raymond Vernon Memorial Award for the best paper published in JPAM in 2020. Sounman Hong received the Beryl Radin Award for publishing the best paper at JPART in 2017. Hyunjung Lee presented the best conference paper in APPAM 2019 and was awarded the APPAM & Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis Award.

Table 4. East-Asian awardees with academic associations (2017–2021)

Besides research awards, East-Asian scholars were also recognized for teaching and service awards. For example, in 2018, Alfred Tat-Kei Ho received the NASPAA Leslie A. Whittington Excellence in Teaching Award; and Angela Park received the NASPAA Social Justice Curriculum Award. Myung Jin was awarded the Pi Alpha Chapter Advisor Award of Excellence in 2017. The Donald C. Stone Service to ASPA Award was presented to Pan Suk Kim in 2019, and to M. Jae Moon in 2020. Eric Chan won the JPAM Refereeing Award in 2020.

Young professional and doctoral student awardees suggest the future scholarly growth of East-Asian scholars. Trang Hoang and Angela Park received the Staats Emerging Scholar Award from NASPAA in 2018. The Pi Alpha Student Manuscript Award was presented to Jinhai Yu in 2017, and to Sunyoung Pyo in 2019. Hanjin Mao was awarded the ASPA Walter M. Mode Scholarship Award in 2021. David Woo and Kirby A. Chow received the APPAM Fall Conference Poster Session Awards in 2017.

East-Asian doctoral students have produced many award-winning dissertations. For example, Lang Yang and Y. Nina Gao received the APPAM PhD Dissertation Award in 2017 and 2018, respectively. Trang Hoang and Seulki Lee were the winners of the NASPAA Annual Dissertation Award in 2019 and 2020, respectively. Huafang Li and Miyeon Song were awarded the PMRA Best Dissertation Award in 2018 and 2019, respectively. East-Asian graduate students also actively participate in conferences and have been selected for scholarships and fellowships from the academic associations. Twelve East-Asian graduate students have been recognized as ASPA Founder’s Fellows since 2017 and 2021, accounting for 15% of the total awardees in this award category. ASPA awarded the Wallace O Keene Conference Scholarships to four East-Asian students in 2017–2021. APPAM awarded Equity and Inclusion Student Fellowships to 14 East-Asian students in 2017–2019.

East-Asian scholars’ leadership roles in associations

Finally, we also examined the leadership teams of academic associations and their representation of East-Asian scholars. We collected data from each association’s website in 2021 and found that associations use different labels for their leadership positions. ASPA’s website for leadership lists the positions of President, President-Elect, Immediate Past President, Executive Director, District Representatives, and Student Representatives. Section positions are not included in the leadership team. The total number of ASPA’s leadership is 21, and 3 of them are East-Asian scholars. NASPAA uses “Executive Council” to name its leadership on the website, which contains President, Vice-President, Immediate Past President, and 15 Council members. Among NASPAA’s 15 council members, only one is an East-Asian scholar. On APPAM’s website, 9 officers (President, President-Elect, Vice-president, etc.) and 17 Policy Council members are featured as the leadership team. Finally, PMRA uses the term “Board of Directors” for its leadership, which comprises President, Vice-president, Director of the Secretariat and Treasurer, Past President, and 13 Board Members. Neither APPAM nor PMRA has an East-Asian scholar in their leadership team. As shown in , ASPA manifests the highest representation of East-Asian scholars in their leadership team, with 14% of the leadership positions taken by EAS. Such representation in NASPAA is only 5.6%. In sum, East-Asian scholars are generally underrepresented in the leadership teams of the four academic associations.

Table 5. Representation of East-Asian scholars in associations’ leadership (2020).

Conclusion

Against a background of diversification and globalization, this article is the first study to contribute a deep understanding regarding the influx of East-Asian scholars in American public administration. It objectively examines East-Asian scholars’ overall participation and contributions to the field. Four major findings can be highlighted.

First, across the top 100 PA schools, approximately 5% of the total full-time faculty members are East-Asian scholars. However, the acceptance of this minority group is substantially unequal from school to school. Although in five PA schools more than 10% of their faculty members are East-Asian scholars, in the majority of schools only one or none East-Asians are on the faculty.

Second, examination of a PhD program in public administration with a total number of 133 graduates shows that about 30% of their students were from East-Asia, and more than 80% of those East-Asian graduates successfully located themselves in tenure-track faculty positions, with more than half of those at US universities. Compared to other PhD graduates, East-Asian students are more likely to graduate sooner and more likely to pursue academic careers. If the PhD program represents a typical pattern of public administration doctoral education, we have reasons to believe that the participation of East-Asian scholars in American PA schools will steadily increase.

Third, East-Asian scholars with academic positions all over the world actively contribute to conference presentations and journal publications in American and other contexts. Almost 20% of the peer-reviewed articles published in the Top 10 PA journals are contributed by East-Asian scholars. East-Asian students and young scholars are increasingly recognized at conferences through awards and fellowships. This suggests globalization of the public administration academic community.

Fourth, East-Asian scholars’ representation in journal and association leadership teams still remains low, which does not match their participation in conferences and contributions to journal articles. Diversification at the leadership level still requires more attention.

Suggestions for future research

Our research describes the participation, contribution, and representation of East-Asian scholars in the academy of public administration. By nature, it is a descriptive study. We expect that future research will address some in-depth issues, such as:

What determines a PA school’s openness to hiring East-Asian scholars or other faculty members with minority backgrounds?

How does the participation of East-Asian faculty in American PA schools change the educational cultural and training approaches?

Is there a gender difference in East-Asian scholars’ participation and contributions in the American PA society?

Do East-Asian faculty confront inequity in promotion and salary bargaining in PA schools?

What are the types and severity of challenges that East-Asian PA scholars face while they are navigating academia in the United States?

How could PA schools take advantage of diversity and globalization to prepare students for leadership in the new era?

References

- ASPA Section on Korean Public Administration. (2021). #StopAsianHate. https://www.facebook.com/ASPASKPA/posts/stopasianhatea-joint-statement-by-thesection-on-chinese-public-administration-sc/4215163798495274/

- Broadnax, W. D. (2010). Diversity in public organizations: A work in progress. Public Administration Review, 70, s177–s179. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2010.02268.x

- Caleb, P. (2014). How diversity works. Scientific American, 311(4), 43–47.

- Carrizales, T., & Gaynor, T. S. (2013). Diversity in public administration research: A review of journal publications. Public Administration Quarterly 37(3), 306–330.

- Center for the Study of Hate & Extremism. (2021). Report to the nation: Anti-Asian prejudice & hate crime: New 2020‐21 first quarter comparison data. https://www.csusb.edu/sites/default/files/Report%20to%20the%20Nation%20-%20Anti-Asian%20Hate%202020%20Final%20Draft%20-%20As%20of%20Apr%2030%202021%206%20PM%20corrected.pdf

- Coelen, R. (2015). Why internationalize education? International Higher Education, 83(83), 4–5. https://doi.org/10.6017/ihe.2015.83.9074

- Cole, S., & Barber, E. G. (2003). Increasing faculty diversity: The occupational choices of high-achieving minority students. Harvard University Press.

- Devereux, E. A., & Durning, D. (2001). Going global? International activities by US schools of public policy and management to transform public affairs education. Journal of Public Affairs Education, 7(4), 241–260. https://doi.org/10.1080/15236803.2001.12023521

- Farmbry, K. (2007). Expanding the pipeline: Explorations on diversifying the professoriate. Journal of Public Affairs Education, 13(1), 115–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/15236803.2007.12001471

- Frederickson, G. (2005). The state of social equity in American public administration. National Civic Review, 94(4), 31–38. https://doi.org/10.1002/ncr.117

- Hewins-Maroney, B., & Williams, E. (2013). The role of public administrators in responding to changing workforce demographics: Global challenges to preparing a diverse workforce. Public Administration Quarterly, 37(3), 456–490.

- Hong, S. (2017). Does increasing ethnic representativeness reduce police misconduct? Public Administration Review, 77(2), 195–205. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12629

- Hser, M. P. (2005). Campus internationalization: A study of American universities’ internationalization efforts. International Education, 35(1), 35–48.

- Institute of International Education. (2018). International students enrollment data. https://www.iie.org/en/Research-and-Insights/Open-Doors/Data/International-Students

- Institute of International Education. (2019). Fall 2019 snapshot survey. https://www.iie.org/en/Research-and-Insights/Publications/Fall-2019-International-Student-Enrollment-Survey

- Institute of International Education. (2020). Fall 2020 snapshot survey. https://www.iie.org/Research-and-Insights/Publications/Fall-2020-International-Student-Enrollment-Snapshot

- Knight, J. (2012). Five truths about internationalization. International Higher Education, 69, 4–5.

- Knight, J. (2017). Global: Five truths about internationalization. In G. Mihut, P. G. Atlbach, & H. de Wit (Eds.), Understanding higher education internationalization. pp. 13–15. Sense Publishers.

- Lim, H. H. (2006). Representative bureaucracy: Rethinking substantive effects and active representation. Public Administration Review, 66(2), 193–204. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2006.00572.x

- Lu, E. Y., Li, H., & Mao, H. (2019). An overview of CPAR publications 2002–2019. Chinese Public Administration Review, 10(2), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.22140/cpar.v10i2.207

- Martin, G. C. (2014). The effects of cultural diversity in the workplace. Journal of Diversity Management (JDM), 9(2), 89–92. https://doi.org/10.19030/jdm.v9i2.8974

- Mosher, F. C. (1968). Democracy and the public service (Vol. 53). Oxford University Press.

- Qiang, Z. (2003). Internationalization of higher education: Towards a conceptual framework. Policy Futures in Education, 1(2), 248–270. https://doi.org/10.2304/pfie.2003.1.2.5

- Riccucci, N. M., & Van Ryzin, G. G. (2017). Representative bureaucracy: A lever to enhance social equity, coproduction, and democracy. Public Administration Review, 77(1), 21–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12649

- Rice, M. F. (2004). Organizational culture, social equity, and diversity: Teaching public administration education in the postmodern era. Journal of Public Affairs Education, 10(2), 143–154. https://doi.org/10.1080/15236803.2004.12001354

- Ryan, S. E. (2010). Let’s get them out of the country! Reflecting on the value of international immersion experiences for MPA students. Journal of Public Affairs Education, 16(2), 307–312. https://doi.org/10.1080/15236803.2010.12001598

- Sabharwal, M., Levine, H., & D’Agostino, M. (2018). A conceptual content analysis of 75 years of diversity research in public administration. Review of Public Personnel Administration, 38(2), 248–267. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734371X16671368

- Shanahan, E. (2022). Man hit woman in the head 125 times because she was Asian, officials say. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/03/14/nyregion/yonkers-hate-crime-anti-asian-attack.html

- Stop AAPI Hate. (2022). National report. https://stopaapihate.org/national-report-through-december-31-2021/.

- Wooldridge, B., & Rubin, M. (2000). Building the professoriate of the future: Increasing faculty diversity in PA programs (Diversity Report). National Association of Schools of Public Affairs and Administration.

- Yam, K. (2022). Anti-Asian hate crimes increased 339 percent nationwide last year, report says. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/asian-america/anti-asian-hate-crimes-increased-339-percent-nationwide-last-year-repo-rcna14282

- Yang, K. (2009). American public administration: Are we prepared for the challenges? Public Performance & Management Review, 32(4), 579–584. https://doi.org/10.2753/PMR1530-9576320407

- Zraick, K. (2022). Man charged with hate crimes after 7 Asian women are attacked in 2 hours. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/03/02/nyregion/asian-women-attacked-nypd.html on 3/17/2022