Abstract

Reflexivity, which requires the conscious appraisal of how researchers’ social positions and subjectivities interact with the research process, has become increasingly popular in qualitative research with participants at heightened risk of marginalization and trauma histories. Despite the documented traumas associated with marginalization, little has been written about the process of integrating a reflexive approach into research with marginalized communities. This methodological paper seeks to redress this gap by illuminating how our research team used the lens of space as a reflexive framework to attend to positionality, transformation, and power in a qualitative study with older persons with experiences of homelessness. These reflections emerged from our work conducting research in one of three sites associated with a pan-Canadian study, on housing, aging, place/space, and homelessness. More specifically, they emerged from our team’s observations and de-briefings during and following data collection with 11 participants (aged 50+ years) of a long-term transitional housing site in Montreal, Canada. These reflections illuminate how integrating concepts of space may provide an avenue for attending to reflexivity when conducting research that informs policy and public service initiatives for marginalized communities, and support research processes that disrupt tendencies to overlook trauma.

Ultimately, home is not a physical place. Ultimately, home is feeling safe, secure, capable … inside myself. This is where the Anchoring in Space really […] addresses a very basic human need to be seen, heard, and accepted as is. Once I feel safe with you, and see you’re not trying to “make me fit into your agenda”, I might open up to you and tell you really what’s going on. (Dyane Provost, Co-author and Lived Expert)

A critical priority of policies that seek to support the needs of marginalized groups includes breaking down structural barriers and building bridges between organizations and individuals experiencing social exclusion and inequity (Barnes et al., Citation2003; Clark, Citation2018; Lombe & Sherraden, Citation2008). Policy-driven research is well positioned to support these aims if the voices, experiences, and recommendations of persons with lived experience are elevated and used to inform the public agenda and its’ accompanying strategies. One population whose experiences and voices could contribute great value to making policies more inclusive, equitable, and accessible are older persons with experiences of homelessness who are growing in numbers globally (Crane & Joly, Citation2014), and whose intersecting positions as older and homeless create multiple and unique layers of marginalization that require research and policy attention (Amster, Citation2003; Cockersell, Citation2018). Given the layers of intersections that often accompany marginalization, qualitative research that informs policy can be favorable in illuminating hidden interactions and variables that are experienced by an individual within a broader environmental context (Davies, Citation2000; Sallee & Flood, Citation2012). In this way, qualitative inquiry can complement the exploration of social issues addressed by policy research by leaning more deeply toward a participant’s experiences while also attending to how current cultural, institutional, and policy factors interact with their experiences.

Like other marginalized groups, older homeless persons have a high prevalence of trauma that is rarely acknowledged or attended to in the range of services and supports designed to support them (Kim & Ford, Citation2006). With a reported prevalence rate of trauma amongst the homeless population ranging from 50 to 98%, researchers seeking the input of older persons with experiences of homelessness (Buhrich et al., 2000 as cited in Deck & Platt, Citation2015; Burns et al., Citation2018; Burns & Sussman, Citation2019; Kessler et al., 1995 as cited in Kim & Ford, Citation2006; Lalonde & Nadeau, Citation2012) should create a research encounter cognizant that underlying traumas of this population, if rendered invisible, could reproduce a sense of exclusion and marginalization.

A reflexive approach to research has been purported to mitigate some of the ethical risks associated with conducting research with individuals with histories of trauma and experiences of marginalization (Abdelnour & Abu Moghli, Citation2021; Henwood, Citation2008). A reflective approach is a process of ongoing and conscious attendance to the interrelated tenants of positionality (Bourke, Citation2014; Working Group of the Knowledge Hub Community of Practice, Citation2020), transformation (Giorgio, Citation2013; Haynes, Citation2006; Smith, Citation1999), and power dynamics (Isobel, Citation2021; Kimberg & Wheeler, Citation2019; Merriam et al., Citation2001), which have been elaborated on in . Hence, illuminating how researchers can engage in such a reflexive process when conducting fieldwork with marginalized populations remains an important area of social science scholarship. This paper describes how our research team used the concept of space (a common theoretical anchor in research with homeless persons) to engage in reflexivity when conducting research with formerly homeless older persons. Our reflexive process of attending to our positionality and supporting the transformative potential of participants illustrates the steps and nuances involved when attempting to conduct meaningful research with marginalized groups, both from the inception of a project as well as while the project unfolds. In doing so, we offer considerations for ways in which researchers and scholars can more ethically engage in processes of eliciting information from persons who are valuable knowledge holders—whether this be in academic, governmental, or non-profit research endeavors.

Table 1. Definitions of reflexive tenants.

Space and place in homelessness

Space has been conceptualized as both physical (e.g., the bricks and mortar of a place) and relational (e.g., the boundaries or sociopolitical norms governing how to interact in a place). Research attending to these elements of space have noted their importance in addressing healing, healthy aging, and successful rehousing for older persons with experiences of homelessness (Canham et al., Citation2021). For example, older persons with experiences of homelessness encounter reoccurring systemic exclusion from physical space, through the process of being scrutinized and asked to leave public spaces (Amster, Citation2003; Cockersell, Citation2018; Cresswell, Citation1996). Further, older persons with experiences of homelessness have been found to feel “out of place” even when rehoused if the physical environment, staff interactions or rules and regulations governing the space threaten a sense of control, security, and self-expression (Burns et al., Citation2020). Finally, social and political norms which transcend space and can impact the way bodies within a given space relate and interact with one another (Bourdieu, Citation1989) and the ways in which individuals experience a sense of threat or safety in a given space (The Roestone Collective, Citation2014). With these broader sociopolitical dynamics in mind, attending to space and supporting the feeling of being “in place” during the research encounter is even more pressing when aiming to conduct research that is sensitive to trauma histories of people experiencing marginalization, such as older persons with experiences of homelessness.

In this article we draw from Harrison and Dourish (Citation1996) conceptualization of sociopolitical and relational space. More specifically, we consider sociopolitical space to represent “the structure of the world; […] the three-dimensional environment in which objects and events occur, and in which they have relative position and direction”), and relational space to embody “a space with something added—social meaning, convention, cultural understandings about role, function and nature and so on” (Harrison & Dourish, Citation1996, p. 69). It is within the interactions and meanings (i.e., relational space) embedded within sociopolitical space that we orient our reflexive process.

Materials and methods

The reflections presented below emerged from our field work interviewing and interacting with 11 older persons with experiences of homelessness, who were 50 years of age and older and rehoused in a long-term transitional housing site in Montreal, Quebec. With nine participants, we conducted a series of three in-person semi-structured interviews; two participants only completed a single in-person semi-structured interview. All interviews were completed over a four-week period between June 2021 and July 2021. The study on which these reflections are based, is part of a larger three-city Canadian project aimed at exploring how to support aging in the right place for older persons with experiences of homelessness in different housing circumstances (Canham et al., Citation2022). More specifically, this study is based on interview data, site observations, and field notes that two of us (Diandra and Émilie) conducted as graduate students and novice researchers in Montreal site. We have provided participants with pseudonyms to maintain anonymity.

Below we describe the two key reflexive tenants oriented in space: (1) attending to positionality through “sensing space” and (2) supporting participant transformation through “holding space.” These tenants, which were supported by the researchers’ postures (embodied presence in space) stemmed from the iterative process by which we conducted and adapted our fieldwork. Throughout the intensive data collection process and onsite presence, we worked closely together and the Montreal senior researcher, Tamara Sussman, de-briefing interviews, discussing onsite observations, and planning subsequent research encounters. These frequent de-briefs allowed us to identify and express our emotional reactions during and following data collection and our observations about what may or may not be working in our approach. It was through these supportive exchanges that we were able to enhance our capacities to attend to the relational spaces and sociopolitical spaces that we describe below and make the nuanced processes of reflexivity more visible and accessible to ourselves and (we hope) to our readers. draws from the conceptual elements of space, positionality, and transformation to illustrate our process of engaging in reflexivity and includes the two reflexive tenants oriented in space, the accompanying postures, and the adaptations we integrated to support these postures.

Table 2. Reflexive tenants and considerations to guide application of a reflexive approach oriented in space.

Findings

Attending to positionality through “sensing space”

Informed by the vast literature on attending to positionality, we entered the field understanding that it was important to be aware of our social locations so that we could enhance our sensitivities towards the needs of our study participants (England, Citation1994; Sultana, Citation2007; Working Group of the Knowledge Hub Community of Practice, Citation2020). As such, we had an ongoing dialogue about how our multiple identities might affect our capacities to connect with participants, as well as how these might frame our understandings of their experiences. Prior to entering the field, we identified several characteristics that we (Diandra and Émilie) shared with participants which may have increased our sensitivities when establishing safety in our exchanges. For example, we anticipated that our experiences caring for family members with mental health issues might sensitize us to the unique needs and experiences of the participants. We also noted aspects of our personal identities that we anticipated may foster connectedness with certain participants. Diandra’s family history of immigration, and acculturation offered her a reference point from which to connect with those participants with similar stories. Émilie’s Francophone, lower-middle class background was anticipated to contribute to a sensitivity towards the challenges of social inequalities faced by participants, including a shared Francophone history in a province with tensions related to Anglicization. Finally, we discussed aspects of our histories that could position us as outsiders, including our histories of stable housing, our younger ages, our positions as researchers, and our gender identities (as women interviewing largely male participants). What we realized during our engagement in fieldwork was the extent to which the lens of space informed our application of these positions. More specifically, our efforts of sensing and attending to relational space and sensing space over time to attend to relational power, helped us to shift the relational dynamics between ourselves and the participants, and create rich opportunities for our multi-dimensional selves to emerge and connect.

Sensing and attending to relational space

We began our engagement in the research process with participants in an informal way. We organized a “meet and greet” in the common space of the housing complex we were partnering with to recruit participants. During this two-hour event we tried to conduct ourselves as guests in a space—engaging in casual conversation with the residents over coffee and snacks, sharing a bit about who we were and what our research was about, and asking questions to get to know some of the residents we may be interviewing. While we hoped that this group activity could help us in our outreach efforts, we did not anticipate the degree to which this informal process of connection and exchange could help us to attend to issues of positionality that we could carry forward into our interviews and which we believe contributed to richer exchanges with the participants.

For example, within the context of an informal discussion a Spanish-speaking resident Shawn, inquired about Diandra’s cultural identity. This question sparked a conversation about immigration and shared language as well as differences in cultural and racial backgrounds. The connection made between Shawn and Diandra while sharing their experiences was carried forward into the individual interviews as they moved between French and Spanish and discussed similarities and differences in their cultural heritage. Diandra recognized these exchanges as honoring Shawn’s need to get to know parts of her as a person, which we feel eventually fostered his capacity to open up about the traumatic impact of his immigration process. Our reciprocal exchanges also allowed us to attend to identities that might have distanced us from our study participants. For example, during the informal meet and greet, many of the men voiced their appreciation at “Seeing pretty girls,” making the gender differences between us explicit.

Our sensitivities to relational space, allowed us to reflect on the meaning of these differences and carry these reflections into our subsequent individual interviews. For example, in an interview encounter, Diandra questioned Kevin, one of the research participants who had made a comment on our appearance during the meet and greet, about whether his pastime of watching people and noticing women’s beauty supported a feeling of connection, which seemed to have validated the emotional significance of his experience and allowed him to elaborate on it. Although the male participant’s statements made our differences explicit and called attention to our gendered/outsider positions, our awareness and attention to these differences allowed us to use these as points of exchange and exploration, creating relational opportunities for the men to address deeper sentiments surrounding the connections and relationships they lost, missed, or yearned for in later interview conversations.

Overall, the meet and greet afforded us the opportunity to connect, identify areas of commonality and difference, and attend to the ways in which these identities surfaced as we navigated the relational space between ourselves and our participants in the context of our research interviews.

Sensing space over time to attend to relational power

Realizing the extent to which personal and informal connections appeared to break down barriers between ourselves and our participants, we decided that we would create further opportunities for connection by being onsite two full days per week for the duration of the recruitment and interviewing period. While our intention was largely to create further opportunities for informal exchanges, our regular presence in the housing complex allowed us to experience first-hand the control and regulation that was ingrained within the fabric of that environment.

Despite our attempts at connecting with participants through reciprocal exchanges, we sensed that our positions of power and authority as outsiders were highly visible to residents at the inception of our research. Not only were we younger, and living outside of the housing complex (two social privileges that separated us from participants), but we were also given two private offices from which to conduct our interviews (a privilege more commonly afforded to staff than to residents). This separation between “us” and “them” was made explicit to us when residents mistook us for staff, and entered the offices we were provided to ask us for instrumental assistance. Yet, over time, as the relational space between ourselves and our participants narrowed through our shared dialogue. Simultaneously, we started to notice that our dynamics with administrators/staff also shifted from feeling an initial closeness to feeling more distance. For example, the offices where we were conducting interviews became less private, as staff began walking in on our interviews and staff made more inquiries about how long we would be using the space. At one point, we lost access to one of the offices originally assigned to us. Seemingly, the closeness and familiarity we had the luxury of establishing with residents was gradually shifting our status with staff from welcomed allies to burdensome outsiders. Our sensitivities to space provided us with a glimpse of what residents had described to us tensions with a prolonged stay at the housing site to feel more at home and in place. This heightened our understanding of the need for ongoing support and safety, which we attended to by regularly distinguishing our relationship and role from that of the employees of the housing setting, minimizing conversations with staff/administration when they inquired about the progress of our research, and through continued reminders of the anonymity of the interviews.

Sensing and attending to relational space while immersed in the setting for an extended period of time allowed us to both observe and experience first-hand how power dynamics within the space could be shaping participants’ experiences both with homelessness and with us as researchers. Our first-hand accounts improved our capacities to attend to these issues during our encounters with participants through our joint understanding and our need to establish a clear separation between ourselves and staff.

Supporting participant transformation through “holding space”

As we began to engage in interviews with participants, we became keenly aware that the transformative potential that can come with sharing stories of trauma and resilience may only be achieved if participants can be held by a calm presence, whose curiosity and authenticity supports the telling of and reflecting upon their stories. With this in mind, we knew that it was important to reflect or restate what we had heard and provide the space and time for an interview to unfold naturally allowing participants to lead the rhythm of the exchange and repeat events or stories so that they could process their experiences and potentially achieve a new understanding of their lives. However, with the pressure of our research questions and foci looming it was not always easy to actualize these processes. Over time, we found a way of balancing these tensions by adapting the research tools we were using to elicit information from participants and by viewing repetition as a necessary element of our exchanges. We illuminate below how these adaptations evolved and the impact we believe they had on our exchanges.

Holding presence in space

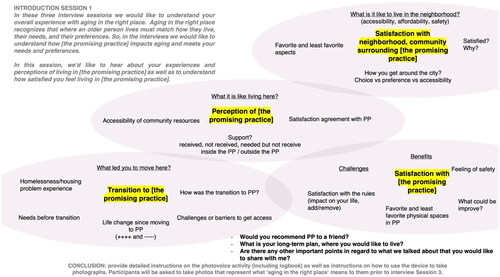

In qualitative interviewing, the interview guide forms the template from which a research conversation unfolds, and research questions are addressed. While we knew this research tool was necessary to help us navigate the research conversation, the extensive list of questions we originally developed to capture themes related to place and space served to detract us from our capacities to hold our presence in space. When we realized through our research de-briefings that the length and linear nature of the guide constrained our capacities to foster a fluid exchange with our participants, we decided to replace it with a visual map (). The visual map, which provided us with visual cues to remind us of our intended focus, promoted our capacity to hold presence in space by giving participants the opportunities to access their own rhythmic storytelling and revisit experiences or perspectives that they identified as significant. Our team de-briefings also allowed us to reframe our own understandings of repetition, viewing it as a sign that something important was being told. By viewing reemerging stories as opportunities to help participants uncover meanings from these events, we were able to encourage a reflective process that was transformative for some participants (Walsh et al., Citation2010).

For example, Kevin, who was given the space and opportunity to repeatedly speak of the “surveillance” and distress he was experiencing within the housing organization in his first interview, seemed to slightly shift this orientation in his subsequent interviews characterizing a worker as “much more helpful”, and how the presence of other residents allowed him to “break the isolation” he had been experiencing. We believe that part of this shift was fostered by the space we allowed for distressing and complex stories to be told and retold so that new meanings could be derived.

In other instances, participants’ re-storying and the researchers’ gentle validation, appeared to elicit acknowledgement of resilience in participants’ narratives that may not have been so explicit in their initial telling. For example, when Jeffery recounted the onset of his depression to friends, in his first interview, he noted the loss and stigma that accompanied his disclosure. He stated, “I lost all my friends then, when they realized I was suffering from mental illness, they didn’t bother with me anymore.” However, in the final interview Jeffery shared a somewhat different story which revolved around self and other acceptance. In this interview, he stated, “She accepted me as I was, even though I was mentally ill, a lot of people become mentally ill, you’d be surprised. You know, one of my friends is mentally ill too. As long as you take your medication every day you become stable. I’m stable now, I can talk to [my family and friends] on the phone, I’m not suffering from severe depression.”

Engaging in a fluid conversational style, prompted by the visual map, appeared to be appreciated by participants, John for example, expressed an appreciation for “the opportunity to talk to people,” and Vincent described his participation in the interviews as having fostered “growth” in himself. As we considered the symbolic meaning of the field guide as an extension of the relational space of our exchanges, we began recognizing the visual map’s capacity to shift the power of storytelling towards the participants in a way that promoted their leadership in forging their story and highlighting the themes that were important to them. It is our reflection that simple adaptations can be made to the research tools’ structures to make the research process more empowering, and to ease the process of holding a fuller and more authentic presence that can elevate the shared transformational potential of both researchers and participants.

Holding as containing relational space

The transformative outcomes that emerged from holding presence for the dynamics and stories shared between the researchers and participants were accompanied by a sense of responsibility to honor the boundaries of the beginning-to-end of this relational space and beyond. Holding a container in space consisted of providing an opportunity for participants to reflect on their experiences in the research process, identify any impacts or insights of their participation, and to consider what this experience meant for them.

We decided to honor our relational space through a formal termination activity that provided an opportunity for collaborative reflection on the research process and the human relationships that had developed along the way. Two months after leaving the field, we invited participants to a reflective group activity within the housing complex that was inspired by an exercise conceived by Augusto Boal (1992/Citation2005). The exercise, which consisted of co-creating a sculpture with objects existing in the space, was intended to metaphorically collect participants’ impressions and feelings of their engagement with the research process. Guiding participants into introspective group reflections, we asked them exploratory questions about: where they felt they were situated in relation to the research, what, if anything, came from this experience, and what they wanted to see emerge from the research and their participation with it. Shane and Jeffrey thoughtfully described their participation as having “cleaned” part of their story—the objects chosen being a duster and pail—and a third, Vincent, suggested their participation “planted a seed” for the future—the object chosen being a watering can. These metaphorical depictions lent further support for the transformative potential we had witnessed as our interviews unfolded over time. Not only did our small acts of holding and containment allow for the telling of rich and meaningful stories, but they also promoted an environment wherein participants—through their own reflections—grew to understand their experiences differently.

Discussion

Our reflections on our research with older persons with experiences of homelessness living in a long-term transitional housing environment suggest that the lens of space can inform a reflexive research process that holds promise for supporting the elicitation of rich data whilst offering transformative opportunities for participants with trauma histories (Kimberg & Wheeler, Citation2019). Our decision to apply a spatial frame to our reflexive process seemed to help us navigate our positions as researchers, attend to power dynamics, and act as the “holders” of emotional space—all of which allowed participants to meaningfully engage in the research process.

The exchanges that took place outside of the interview encounter, such as during the informal introductory meet and greet, were useful in allowing us to create a space where our identities could emerge. We understand these exchanges to have supported the development of a “third space” (Dwyer & Buckle, Citation2009) where researchers and participants reflect on their similarities and differences and by so doing develop the authentic connections required for transformation to occur (Granek, Citation2013; Knox & Hill, Citation2003). While we appreciate that fostering such informal exchanges between researchers and participants can serve as a source of tension in the research community (Knox & Hill, Citation2003), our experience suggests that this form of reciprocal exchange may be of particular relevance to marginalized groups with experiences of trauma for whom relational space is pivotal towards mitigating harms.

Our findings further illuminate that sensing space over time can allow researchers to observe sociopolitical space and illuminate issues of power that would otherwise be unapparent. Sensing these power dynamics can enhance researchers’ understandings of participants’ narratives and needs for safety within research encounters. Ethnographers have long noted how observation over extended periods of time can foster a felt-understanding of participants’ narratives (Hoolachan, Citation2016; Watts, Citation2008). In our case, experiencing changes in how we were treated in the housing space fostered a greater understanding of the constraint and regulation participants recounted to us in their narratives, and subsequently led to our heightened attention to pick up on cues for safety and attend to these appropriately. Policy that addresses social inequities situates policymakers as well-positioned to highlight notions of power and work towards change in their dissemination activities. Related, the lens of space—comprising relational dynamics within a broader sociopolitical context—is particularly pertinent in work with populations who have experienced exclusion from space, but who remain in designated spaces over periods of time, such as older people in nursing homes or refugees in internment camps.

Our reflections also suggest that the space we created for circular story-telling—that is, a persons’ natural style and pace of moving from the beginning to the ending of their narratives, using emotional expression and repetition—positioned us as holders of space. We contend that acting as the co-regulators of emotion by protecting the natural rhythm of participants’ storytelling, viewing and addressing repetition as meaningful, providing participants with the space and time to develop alternative viewpoints, and honoring the closure of the experience through a termination activity enabled participants to recount emotionally laden experiences that they may have otherwise blocked (Baum, Citation2005; Neimeyer, Citation2014; Ogden, Citation2004). The spatially informed reflexive de-briefs enhanced our capacities to hold space with our research participants over time. We also found that these exchanges allowed us to consider how the deficit-oriented ontologies that often inform work with older adults could serve to constrain our capacities for holding space. For example, in our initial de-briefs we noted how easy it was to consider the repetition we were seeing in our participants’ stories as a sign of the forgetfulness one might expect of older participants (Schlosser et al., Citation2020). Yet, it was our leaning into stories of repetition that allowed us to hold a space wherein difficult and important stories could be re-told.

Public policy has begun moving in a theoretical direction where administrative and organizational structures seek to be more equitable, just, and inclusive in their development of strategies, programming, and interventions (Meyer et al., Citation2022; Schwoerer et al., Citation2022). Such a focus requires attention to “process,” so that the expertise of persons with lived experiences of marginalization and exclusion are meaningfully integrated into policies and programs that affect their lives. Such a focus also requires the adoption of research strategies that meaningfully elicit the stories of marginalized persons. Qualitative research offers opportunity to uncover complex contextual elements that are embodied within participants’ rich narratives (Fossey et al., Citation2002; Sadovnik, Citation2006) that can sometimes be overlooked in research focused on efficiency and effectiveness (Meyer et al., Citation2022). Although qualitative research brings us closer to hearing participants’ stories, this form of inquiry may not in and of itself be enough to bridge the gap between policy and research if the voices of those most gravely affected by marginalization are excluded or harmed by a research process that neglects their experiences of trauma.

We recommend that policy researchers who seek to include the voices of marginalized groups with experiences of trauma in their research consider the ways in which notions of sensing space and holding space can inform their research designs and approaches so that meaningful exchanges between researchers and participants can occur and so that the disenfranchisement of trauma can be mitigated.

In light of these findings, engaging in research with individuals who have experienced marginalization and/or who may enter research exchanges with experiences of trauma (Hudson, Citation2016) requires that researchers remain accountable to the ethical obligation of minimizing harm, but also to an obligation of fostering opportunities for participants to experience individual and/or collective transformation, which can be realized through a reflexive approach to qualitative research. Thinking about reflexivity through the lens of relational and sociopolitical space, can be a beneficial tool to help engage in its’ tenants of attending to positionality, navigating power, and supporting the likelihood of personal transformation (through the process of the study) and sociopolitical transformation (through highlighting and addressing issues of power in dissemination activities). Building in opportunities for reciprocal exchanges (like a meet and greet), being more present in the space (if there is a space to move into), using visual maps instead of narrative guides to promote the individual’s natural rhythm of story-telling, integrating a closing reflexive activity, and creating opportunities for regular team de-briefing, can be mechanisms that help to achieve this end.

Ethics statement

Ethics approval was obtained by research ethics boards at three participating institutions: McGill University (#20-09-008), Simon Fraser University (#20200204), and University of Calgary (#20-1229).

Acknowledgments

We respectfully acknowledge that McGill University is situated on Kanien’kehà:ka, a place which has long served as a site of meeting and exchange amongst nations. For contributions to this project, we would like to acknowledge our passionate Montreal lived expert advisors: Dyane Provost, Michel Gauthier, Janet Torge, without whose invaluable insights this project would not be possible.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abdelnour, S., & Abu Moghli, M. (2021). Researching violent contexts: A call for political reflexivity. Organization, 2021, 135050842110306. https://doi.org/10.1177/13505084211030646

- Amster, R. (2003). Patterns of exclusion: Sanitizing space, criminalizing homelessness. Social Justice, 30(1), 195–221. http://www.jstor.org/stable/29768172

- Barnes, M., Newman, J., Knops, A., & Sullivan, H. (2003). Constituting ‘the public’ in public participation. Public Administration, 81(2), 379–399. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9299.00352

- Baum, N. (2005). Correlates of clients’ emotional and behavioral responses to treatment termination. Clinical Social Work Journal, 33(3), 309–326. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-005-4946-5

- Boal, A. (2005). Games for actors and non-actors. Routledge. (Original work published 1992). https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203994818

- Bourdieu, P. (1989). Social space and symbolic power. Sociological Theory, 7(1), 14. https://doi.org/10.2307/202060

- Bourke, B. (2014). Positionality: Reflecting on the research process. The Qualitative Report, 19(33), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2014.1026

- Burns, V. F., Deslandes-Leduc, J., St-Denis, N., & Walsh, C A. (2020). Finding home after homelessness: Older men’s experiences in permanent supportive housing. Housing Studies, 35(2), 290–309. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2019.1598550

- Burns, V. F., & Sussman, T. (2019). Homeless for the first time in later life: Uncovering more than one pathway. The Gerontologist, 59(2), 251–259. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnx212

- Burns, V. F., Sussman, T., & Bourgeois-Guérin, V. (2018). Later-life homelessness as disenfranchised grief. Canadian Journal on Aging = La Revue Canadienne du Vieillissement, 37(2), 171–184. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0714980818000090

- Canham, S. L., Bosma, H., Palepu, A., Small, S., & Danielsen, C. (2021). Prioritizing patient perspectives when designing intervention studies for homeless older adults. Research on Social Work Practice, 31(6), 610–620. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731521995558

- Canham, S. L., Weldrick, R., Sussman, T., Walsh, C. A., & Mahmood, A. (2022). Aging in the right place: A conceptual framework of indicators for older persons experiencing homelessness. The Gerontologist, 62(9), 1251–1257. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnac023

- Clark, J. K. (2018). Designing public participation: Managing problem settings and social equity. Public Administration Review, 78(3), 362–374. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12872

- Cockersell, P. (Ed.). (2018). Social exclusion, compound trauma and recovery: Applying psychology, psychotherapy and pie to homelessness and complex needs. Jessica Kingsley.

- Crane, M., & Joly, L. (2014). Older homeless people: Increasing numbers and changing needs. Reviews in Clinical Gerontology, 24(4), 255–268. https://doi.org/10.1017/S095925981400015X

- Cresswell, T. (1996). In place/out of place: Geography, ideology, and transgression. University of Minnesota Press.

- Davies, P. (2000). Contributions from qualitative research. In H. T. O. Davies, S. M. Nutley, & P. C. Smith (Eds.), What works? Evidence-based policy and practice in public services (pp. 291–316). The Policy Press.

- Deck, S. M., & Platt, P. A. (2015). Homelessness is traumatic: Abuse, victimization, and trauma histories of homeless men. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 24(9), 1022–1043. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926771.2015.1074134

- Dwyer, S. C., & Buckle, J. L. (2009). The space between: On being an insider-outsider in qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 8(1), 54–63. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690900800105

- England, K. V. (1994). Getting personal: Reflexivity, positionality, and feminist research. The Professional Geographer, 46(1), 80–89. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0033-0124.1994.00080.x

- Fossey, E., Harvey, C., McDermott, F., & Davidson, L. (2002). Understanding and evaluating qualitative research. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 36(6), 717–732. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-1614.2002.01100.x

- Giorgio, G. (2013). Trust. listening. reflection. Voice: Healing Traumas through Qualitative Research. Counterpoints, 354, 459–474.

- Granek, L. (2013). Putting ourselves on the line: The epistemology of the hyphen, intersubjectivity and social responsibility in qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 26(2), 178–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2011.614645

- Harrison, S., & Dourish, P. (1996). Re-place-ing space: The roles of place and space in collaborative systems. In Proceedings of the 1996 ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work, 67–76. https://doi.org/10.1145/240080.240193

- Haynes, K. (2006). A therapeutic journey? Reflections on the effects of research on researcher and participants. Qualitative Research in Organizations and Management, 1(3), 204–221. https://doi.org/10.1108/17465640610718798

- Henwood, K. (2008). Qualitative research, reflexivity and living with risk: Valuing and practicing epistemic reflexivity and centering marginality. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 5(1), 45–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780880701863575

- Hoolachan, J. E. (2016). Ethnography and homelessness research. International Journal of Housing Policy, 16(1), 31–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616718.2015.1076625

- Hudson, N. (2016). The trauma of poverty as social identity. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 21(2), 111–123. https://doi.org/10.1080/15325024.2014.965979

- Isobel, S. (2021). Trauma‐informed qualitative research: Some methodological and practical considerations. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 30(Suppl 1), 1456–1469. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12914

- Kim, M. M., & Ford, J. D. (2006). Trauma and post-traumatic stress among homeless men: A review of current research. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 13(2), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1300/J146v13n02_01

- Kimberg, L., & Wheeler, M. (2019). Trauma and trauma-informed care. In M. R. Gerber (Ed.), Trauma-informed healthcare approaches (pp. 25–56). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-04342-1_2

- Knox, S., & Hill, C. E. (2003). Therapist self-disclosure: Research-based suggestions for practitioners. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 59(5), 529–539. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.10157

- Lalonde, F., & Nadeau, L. (2012). Risk and protective factors for comorbid posttraumatic stress disorder among homeless individuals in treatment for substance-related problems. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 21(6), 626–645. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926771.2012.694401

- Lombe, M., & Sherraden, M. (2008). Inclusion in the policy process: An agenda for participation of the marginalized. Journal of Policy Practice, 7(2–3), 199–213. https://doi.org/10.1080/15588740801938043

- Merriam, S. B., Johnson-Bailey, J., Lee, M.-Y., Kee, Y., Ntseane, G., & Muhamad, M. (2001). Power and positionality: Negotiating insider/outsider status within and across cultures. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 20(5), 405–416. https://doi.org/10.1080/02601370120490

- Meyer, S. J., Johnson, R. G., & McCandless, S. (2022). Meet the new Es: Empathy, engagement, equity, and ethics in public administration. Public Integrity, 24(4–5), 353–363. https://doi.org/10.1080/10999922.2022.2074764

- Neimeyer, R. A. (2014). Re-storying loss: Fostering growth in the posttraumatic narrative. In L. G. Calhoun & R. G. Tedeschi (Eds.), Handbook of posttraumatic growth: Research & practice (pp. 68–80). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315805597

- Ogden, T. H. (2004). On holding and containing, being and dreaming. The International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, 85(Pt 6), 1349–1364. https://doi.org/10.1516/T41H-DGUX-9JY4-GQC7

- Sadovnik, A. (2006). Qualitative research and public policy. In F. Fischer (Ed.), Handbook of public policy analysis: Theory, politics and methods (pp. 405–416). CRC Press.

- Sallee, M. W., & Flood, J. T. (2012). Using qualitative research to bridge research, policy, and Practice. Theory into Practice, 51(2), 137–144. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2012.662873

- Schlosser, M., Demnitz-King, H., Whitfield, T., Wirth, M., & Marchant, N. L. (2020). Repetitive negative thinking is associated with subjective cognitive decline in older adults: A cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry, 20(1), 500. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-02884-7

- Schwoerer, K., Keppeler, F., Mussagulova, A., & Puello, S. (2022). Co‐Design‐ing a more context‐based, pluralistic, and participatory future for public administration. Public Administration, 100(1), 72–97. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12828

- Smith, B. A. (1999). Ethical and methodologic benefits of using a reflexive journal in hermeneutic-phenomenologic research. Image-the Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 31(4), 359–363. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1547-5069.1999.tb00520.x

- Sultana, F. (2007). Reflexivity, positionality and participatory ethics: Negotiating fieldwork dilemmas in international research. An International E-Journal for Critical Geographies, 6(3), 374–385.

- The Roestone Collective. (2014). Safe space: Towards a reconceptualization. Antipode, 46(5), 1346–1365. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12089

- Walsh, C. A., Ahosaari, K., Sellmer, S., & Rutherford, G. E. (2010). Making meaning together: An exploratory study of therapeutic conversation between helping professionals and homeless shelter residents. The Qualitative Report, 15(4), 932–947. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2010.1188

- Watts, J. H. (2008). Emotion, empathy and exit: Reflections on doing ethnographic qualitative research on sensitive topics. Medical Sociology Online, 3(2), 3–14.

- Working Group of the Knowledge Hub Community of Practice. (2020). Toward a trauma-and violence-informed research ethics module: Consideration and recommendations. Public Health Agency of Canada. http://kh-cdc.ca/en/resources/reports/Grey-Report–-English.pdf