Abstract

Freedom of Information (FOI) or Access to Information (ATI) legislation regulates the right to make written requests for government records. Previous research either interrogates the effectiveness of FOI/ATI legislation for advancing government transparency or positions the requests as a means for gathering data on government institutions. This article intervenes in this debate by treating FOI/ATI mechanisms as the vantage point from which to examine questions about power in public administration. Adopting a transformative approach, this article explores the potential of using FOI/ATI requests as a liberatory tool that enables the analysis of power dynamics in public administration. For this purpose, the author draws upon her experience with Canada’s ATI regime and requests from the Immigration and Refugee Board. This article documents how ATI requests reveal policy tensions within the Board related to case and performance management, as well as patterns of front-line staff resistance to these measures. It goes on to examine complaints about delays made to the ATI watchdog which expose the attribution of ATI resources towards non-ATI responsibilities. This article highlights the contribution that FOI/ATI requests can make to public administration research.

The idea of government transparency gained prominence in the second half of twentieth century (Ball, Citation2009). One popular instrument for advancing government transparency is Freedom of Information (FOI) or Access to Information (ATI) legislation that regulates the right of citizens, journalists, corporations, and researchers to make written requests for government records. FOI/ATI laws allow requesters to ask for internal government information such as government spending, programs, strategic plans, and, daily communications (Savage & Hyde, Citation2014). The legislation codifies certain exemptions to disclosure, and occasionally designates an oversight body to handle related complaints (Larsen & Walby, Citation2012). According to a recent global survey, 125 countries have enacted FOI/ATI laws or similar guarantees, with 31 countries adopting such provisions since 2013 (UNESCO, Citation2019).

Despite the recognition of FOI/ATI legislation as a cornerstone of government transparency across the world, a growing body of research shows that there are significant barriers of access to government records for those interested in public policy and administration (Campbell, Citation2020; Duncan et al., Citation2023; Roberts, Citation2002, Citation2006). Yet some researchers, recognizing the challenges of gaining access to government information, nevertheless believe that FOI/ATI mechanisms offer a viable way to glean policy processes and practices (Walby & Luscombe, Citation2020), such as the production and use of expert evidence (Gerblinger, Citation2023), contentious security policy concerns around policing and terrorism (Clément, Citation2017), and the management of migration (Tomkinson, Citation2018) to name a few. Thus, previous research either interrogates the effectiveness of FOI/ATI legislation for advancing government transparency or positions the requests as a means for gathering data on government institutions. While the political nature of governing is evident in these studies, the exploration of power dynamics has not been the primary focus. This article intervenes in this debate by treating the FOI/ATI mechanisms as the vantage point from which to consider questions about power in public administration.

Examining, questioning, and transforming power dynamics are key objectives of liberatory research (Freire, Citation2000 [1970]; Gaventa, Citation2021; Mertens, Citation2021; Thambinathan & Kinsella, Citation2021). In line with this perspective, this article draws on the transformative framework of Donna M. Mertens (Citation2021) that emphasizes analyzing positions of power, critically examining different versions of reality, and valuing the lived experiences of affected actors as essential knowledge in research. It combines this commitment with the power cube approach of John Gaventa (Citation2006, Citation2021) that looks at forms, spaces, and levels of power, and their interrelationship. Doing so, this article develops and employs FOI/ATI requests as a transformative qualitative methodology, illustrating their important contribution to public administration studies. FOI/ATI research allows the researcher to obtain relatively unfiltered accounts of everyday administrative practices and to expose the power struggles that lie beneath some of the key concerns of traditional public administration research, such as results-based management, efficiency, and performance.

To demonstrate the contribution of this methodology to a liberatory perspective of public administration, I focus on the implementation of refugee policy in Canada between 2017 and 2020, a period of rising protection claims and multiyear backlogs. This article showcases the value of FOI/ATI research in investigating how policy work is done, and in this case, examining how the increase in pending refugee claims impacts the practices of Canada’s Immigration and Refugee Board, the agency responsible for hearing and deciding refugee protection claims. In my analysis, I draw upon my experience with Canada’s ATI regime and requests from the Refugee Board to illustrate how FOI/ATI research can reveal policy and power dynamics that are often concealed. After establishing the transformative foundations of FOI/ATI research, I present the workings of Canada’s federal ATI regime, which faced sustained criticism for its lack of transparency and delays. I also stress the recent legislative change that empowers the ATI oversight agency to issue binding orders for disclosure (OIC, Citation2021). Investigating how power is exercised and contested in public administration, this article documents how ATI requests reveal policy tensions within the Board related to case and performance management, as well as patterns of front-line staff resistance to these measures since the increase in pending claims. This is followed by an analysis of successful complaints to the ATI watchdog regarding disclosure of Board records that reveal the use of ATI resources for non-ATI responsibilities. The last section highlights the contribution that FOI/ATI requests can make to public administration research. In doing so, this article contributes to recent efforts to broaden the theoretical and methodological underpinnings of public administration research (Guy, Citation2021; Peters, Pierre, Sørensen, & Torfing, Citation2022; Zavattaro, Citation2021).

Applying a transformative approach to freedom of/access to information research

Over seven decades ago, Norton Long (Citation1949, p. 257) wrote, “the lifeblood of administration is power. Its attainment, maintenance, increase, dissipation and loss are subjects the practitioner and student can ill afford to neglect.” More recently, Peters et al. (Citation2022) have suggested that the separation of public administration research from its political nature results in a partial view of the complex reality that the discipline aims to portray. For them, this divide results in neglecting the political underpinnings of administrative practices and the power struggles within and surrounding public administration. Evidently, promoting a political approach to public administration and advocating for a re-evaluation of the field’s relevance are not novel as these ideas have been reiterated regularly since at least the 1950s (Nabatchi, Citation2022). That said, there is currently a stronger emphasis on the importance of these issues, as well as propositions for advancement (Guy, Citation2021; Johnson & Svara, Citation2015; Sowa & Lu, Citation2017).

While their use in in public administration research remains circumscribed (Gerblinger, Citation2023; Roberts, Citation2002; Tomkinson, Citation2018), social scientists increasingly draw on FOI/ATI records to obtain information about inside government practices (Campbell, Citation2020; Clément, Citation2017; Larsen & Walby, Citation2012; Savage & Hyde, Citation2014; Walby & Luscombe, Citation2020). Primarily understood as a method for acquiring government data, FOI/ATI requests serve to provide information that can enrich research endeavors beyond what prevailing methods like interviews, surveys or analysis of publicly available documents can offer (Walby & Luscombe, Citation2020). Yet, despite the growing use of FOI/ATI records to inform research on government processes and practices, few researchers have attempted to theorize their interaction with state power (Luscombe & Walby, Citation2017; Roberts, Citation2006). This section develops the transformative potential of FOI/ATI research.

With its commitment to addressing power imbalances, to shedding light on different versions of reality and prioritizing the experiences of affected groups, transformative research has liberatory ambitions (Mertens, Citation2021). There are various ways of conceptualizing or conducting transformative research, such as humanizing, critical, decolonizing, liberatory, and feminist research. Scholarly conversations regarding its foundations, components, and applications are ongoing (Kabeer, Citation1994; McGee & Pettit, Citation2019; Mertens, Citation2021; Thambinathan & Kinsella, Citation2021). Transformative research frequently entails an inquiry into problems relevant to marginalized groups through partnerships between the researcher and the community (Freire, Citation2000 [1970]; Thambinathan & Kinsella, Citation2021). In addition, a transformative study explicitly aims to address inequities and to elucidate power relationship (Mertens, Citation2021). Therefore, developing FOI/ATI requests as a transformative qualitative methodology also requires a theorization of power.

How to understand power theoretically and how to study it empirically has been an important question in social sciences (Ntienjom Mbohou & Tomkinson, Citation2022). Two contrasting conceptions of power are widespread, “one of power as domination, largely characterised as power over, and the other of power as empowerment, frequently theorised as power to” (Haugaard, Citation2012, p. 33). While seeking to understand how power produces domination is significant, it is not sufficient for liberation. Relatedly, the view of power simply as agency, or power to can “obscure the way power is embedded in socialized norms, beliefs, and behavior, shaping the boundaries of what is considered politically feasible” (McGee & Pettit, Citation2019, p. 2).

These different conceptualizations of power show how the exercise of power and resistance to it are interlinked. John Gaventa (Citation2006) offers an integrative perspective for linking and analyzing the different expressions of power in a given context. His ‘power cube’Footnote1 approach emphasizes that power takes various forms (visible, hidden, invisible), it is exercised in different spaces (closed, invited, claimed) and levels (global, national, local, household). According to Gaventa (Citation2021), this approach aligns with a liberatory outlook, as it offers new insights and associated concepts that researchers can use to examine how power operates and where opportunities for change exist.

Gaventa’s (Citation2006) levels of power are quite straightforward to designate for public administration research, as it refers to the dispersion of authority to different jurisdictions, for instance local, regional, subnational, or federal. Regarding forms of power, visible power can be seen in the decisions of public officials in government institutions. Hidden power can be found by looking outside of these arenas and searching for voices of discontent which are not openly visible. Invisible power refers to the internalization of powerlessness; it explores situations where affected people accept norms and conditions that result in their subordination (Kabeer, Citation1994; McGee & Pettit, Citation2019). Spaces of power addresses how power relations pervade different spaces. Closed spaces are hidden from view or accessible only to some, such as public officials. Invited spaces are those made available by the powerful, such as governments or supranational organizations, to control participation and to legitimize closed spaces. Finally, claimed spaces are those that relatively powerless or excluded groups create for themselves, such as grassroot movements, where they can make their voices heard, challenging both closed and invited spaces (Gaventa, Citation2006).

Using this perspective supports a liberatory outlook by enabling an analysis of how and where power is exercised and contested in public administration. Before moving on to analysis, I will explain how ATI regime functions in Canada.

ATI regime and accessing government information in Canada

Canada’s ATI regime, which covers the Access to Information Act (RSC, 1985, c. A-1) that came into force in 1983, federal government institutions subject to the legislation, as well as the complaint mechanisms in place, has been the subject of much criticism by the ATI oversight agency, the Office of the Information Commissioner of Canada (OIC), elected officials, courts, public servants, researchers, and the media. Recurrent criticism has centered on the restrictive scope of the legislation, extensive delays in the treatment of requests, excessive fees, inconsistent interpretations by government institutions, unjustified exemptions, political interference, a lack of commitment to openness and an entrenched culture of secrecy (Clément, Citation2017; Duncan et al., Citation2023; Larsen & Walby, Citation2012; OIC, Citation2021; Roberts, Citation2002, Citation2006; Thomas, Citation2010).

Specialized units within federal public agencies are responsible for implementing the ATI legislation. To file a request, using a streamlined digital form,Footnote2 requesters must explain which records they seek and pay a $5 fee. In managing disclosures, ATI units may ask for time extension and withhold information under certain exemptions, such as when it infringes upon privacy, federal-provincial affairs, law enforcement, security, and defense (OPC, Citation2021). Previously released ATI documents become part of the public record.Footnote3

While access to government information is considered a quasi-constitutional right in Canada, “right to information” is a misnomer as the Act does not legislate an entitlement to receive these records (Larsen & Walby, Citation2012). In official terms, ATI is a straightforward process of making a records request from a government institution and receiving the related disclosure package. However, in practice, the operational aspects of ATI are less linear and more complicated. Especially in Canada, obtaining government information often requires informally negotiating with ATI analysts and involves unexpected obstacles (Clément, Citation2017; Luscombe & Walby, Citation2017).

The primary channel for lodging complaints about ATI requests is through the OIC, which conducts investigations to ensure compliance.Footnote4 Before the most recent legislative amendment, which came into force in June 2019, the OIC’s authority was comparable to ombuds institutions. In case of denials of information, the Commissioner could investigate and make recommendations to the head of the relevant government institution (OIC, Citation2021; Thomas, Citation2010). The Commissioner was also authorized to produce ATI compliance reports. Currently, following the adoption of Bill C-68 (An Act to amend the Access to Information Act and the Privacy Act and to make consequential amendments to other Acts [S.C. 2019, c. 18]) the OIC has the authority to issue binding orders concerning ATI requests and the release of government records. Thus, the OIC currently plays a more substantial role in the ATI regime. In the next section, before investigating different dimensions of power at Canada’s refugee agency, I will provide a summary of the policy issue.

The challenge of asylum backlog: Visible strategies for tackling the issue

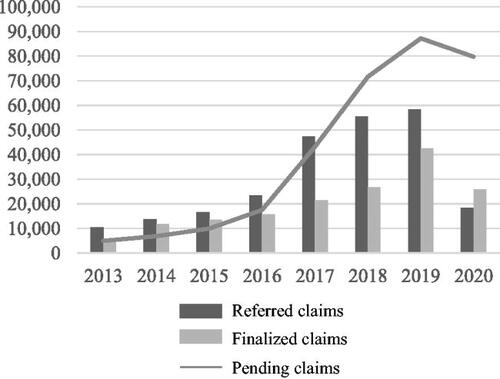

Canada’s refugee policy has been the subject of political and judicial controversy since 2017. Between 2017 and 2020, around 60,000 people claimed refugee status at Canada’s border with the United States (U.S.), entering irregularly via a rural road. Approximately 40% were U.S. residents with precarious immigration status (Smith, Citation2022). Referred to as irregular border crossers by the Canadian federal government, the majority were nationals of Haiti and Nigeria trying to avoid the provisions of the 2004 Canada/U.S. Safe Third Country Agreement (STCA) which would disqualify them for refugee status in Canada. Their arrivals strained reception capacities and provoked debate on the effectiveness of Canada’s refugee policy and the STCA (Tomkinson & Cloutier, Citation2022). This situation intensified intergovernmental conflict, resulted in several judicial review rulings regarding the constitutionality of the agreement,Footnote5 and required billions in emergency expenditure (Auditor General of Canada, Citation2019). The surge also led to multiyear backlogs at the Refugee Board, contributing to an increase in pending claims from under 18,000 in 2016 to over 87,000 in 2019 (IRB, Citation2023). illustrates the shift in the numbers of claims referred to the Board for determination, finalizations, and pending claims since the reform.

Figure 1. Referrals, finalizations and pending refugee claims at the Refugee Board.

Source: IRB (Citation2023)

Referrals, finalizations and pending refugee claims at the Refugee Board

The increased backlog raised significant questions about the Board’s capacity to handle its caseload. The Auditor General of Canada (Citation2019) and an independent, government-commissioned reviewer (Yeates, Citation2018) noted that the growing number of irregular claims contributed to the increasing backlogs. The Board’s inability to meet its case finalization targets, a persistent issue since the enactment of the 2012 reform under the Protecting Canada’s Immigration System Act, exacerbated the backlog. Both reports underscored the need to enhance the efficiency of the refugee determination system.

In response to the backlog, the Refugee Board leadership devised an action plan aimed at boosting its productivity and improving its efficiency, alongside initiatives such as recruiting and training additional front-line staff (IRB, Citation2018). The 2016–2017 and 2017–2018 public reports from the Board recognize the difficulties it has for timely processing of refugee claims, with delays extending as long as 5 years. Subsequent reports emphasize progress made in addressing the backlog and increasing case finalizations. Improvement is attributed to the use of temporary funding for recruiting new staff and the establishment of a performance-driven organizational culture. The reports emphasize “improved productivity through innovation,” the adoption of new measures throughout the decision-making process, including improvements in claim intake, case and performance management strategies, such as short hearings for less complex claims (IRB, 2018–2019, p. 5).

The Refugee Board’s assertions of success in agency operations are illustrative of what Gaventa (Citation2006) calls visible power. In the prevailing views of public administration research, neutral, technical, and apolitical understandings of strategic management or results-based management practices abound (Peters et al., Citation2022). Thus, while we can see that there has been a rise in the number of case finalizations by the Board, the specific mechanisms behind this achievement are unclear. As Zavattaro (Citation2021, p. 1054) notes, “qualitative studies can go beyond telling us what is happening (usually numbers tell that story) to how and why something is happening.” To do this, I will shift our attention to ATI records in an effort to illuminate the obscured power dynamics at play, particularly between Board management and front-line staff.

Unveiling power dynamics in the Refugee Board’s management practices

To gain insight into the driving forces behind announced results, in the summers of 2018 and 2020, I submitted two formal ATI requests to the Refugee Board with a focus on performance and case management strategies. The requests (file # A-2018-01390 and A-2020-00599) sought all records related to performance monitoring, including objectives, indicators, statistical reports, and internal correspondences from January 2012 to August 2020. Choosing a broad time range gave a clear view of operations before the latest legislative change the increase in pending claims after 2017. Additionally, I obtained two previously released ATI packages from the Board on case management, which included records of instructions, procedures, and correspondance related to less complex claims (file # A-2018-03208 and file # A-2018-03171). In total, the four release packages amounted to over 6,000 pages of unstructured documents.

Through an analysis of obtained documents, in this section, I focus on a key issue of public administration research, as defined by Sowa and Lu (Citation2017), looking at the roles of public managers, front-line workers, and their interactions in shaping policy goals and influencing governance results. ATI research brings to light the underlying power dynamics in managerial strategies aimed at steering policy work. I document a policy environment marked by tensions between Board management and front-line workers over increasing efficiency and productivity demands and limited attention to the quality of procedures and refugee decisions.

As an administrative tribunal tasked with determining eligibility for refugee protection, the Refugee Board straddles the line between migration management and protection of human rights (Tomkinson, Citation2018). Compared to other asylum administrations, the Board has traditionally enjoyed insulation and independence from politics and courts (Hamlin, Citation2014). The Refugee Board management overseeing front-line staff (Board members) consists of one Deputy Chair (DC), three Assistant Deputy Chairs (ADC) responsible for three regional offices and Coordinating Members (CM), who supervise teams of 8–12 Board members (Yeates Citation2018). The independent reviewer mandated to examine the reasons for “lower than expected productivity” as the backlog was rising, emphasized the negative consequences of the Board management’s deference to front-line staff. Yeates (Citation2018, pp. 1–2) observed that “limited use has been made of guidance and other tools to both support and supervise these staff” such as setting “targets on decisions expected per week” and adopting “tools such as decision assessment aids”. The power implications of managerial practices, and front-line workers’ responses, should be understood within this context.

It is not possible to discuss here all the strategies deployed to increase efficiency and productivity initiatives. The following discussion, taking a power cube approach (Gaventa, Citation2021) to analyze power relations at the Refugee Board, illustrates how the management exercised hidden power in closed spaces to enact top-down efficiency and productivity initiatives, shifting such choices from local and regional levels to the federal level. Board members expressed their disagreement with these practices in claimed and invited spaces.

Due to issues of communication, uncertainty, limited evidence, and challenges of credibility assessment, determining refugee status is one of the most complex forms of decision-making (Hamlin, Citation2014; Tomkinson, Citation2018). In 2018, one of the strategic case management initiatives introduced by the Board involved the establishment of a task force dedicated to reducing the backlog of so-called “less complex claims” by classifying and prioritizing cases. The aim was to foster collaboration among the regions to address the challenge of pending cases more effectively. Relevant ATI documents indicate that Board management planned to resolve 5,000 to 10,000 refugee claims through this initiative. As they planned to explain to the public: “focusing on these claims in a dedicated manner over a short period of time will help the Board slow the growth of the inventory, reduce wait times and manage the inventory efficiently and fairly, while contributing to overall system integrity” (A-2018-03171, p. 24).The following criteria were used to decide whether a country or claim type was suitable for a short-hearing process: acceptance rates of 80% or higher, or 20% or lower; typically requiring the resolution of only one or two determinative issues; and not often raising complex legal or factual issues (Ibid, p. 32). These cases were presented as being likely to resolve quickly, allowing management to allocate more resources to more complex cases.

The criteria used by Board management to identify less complex claims appear to be neutral, based on purely technical factors, suggesting that treatment and outcomes would be equitable as well. However, e-mail correspondence between the three regions (ADCs and CMs) in early 2019 shows that top management was considering streamlining claims from Nigerian nationals—one of the top countries of alleged persecution among irregular border crossers—into short hearings even though the acceptance rate was over 40% in 2017–2018. (A-2018-03208, pp. 1967–68 and pp. 2760–2769). The e-mail from a Board member to management, excerpted below, shows how this practice falls short of equity, which seeks to ensure that “all social groups will have the same prospects for success and the same opportunities to be protected from the adversities of life” (Johnson & Svara, Citation2015, p. 3):

…I worked in Montreal this past summer for two weeks doing exclusively Nigerian claims, many of which resulted in negative decisions. None of them would have been completed in less than the regular hearing time… Yes, some Nigerian cases (such as FGM) can lead to a straightforward decision given the jurisprudential guide: however, that does not mean that the hearing itself is at all straightforward. Many areas need to be canvassed in order to ensure that an IFA is truly available in those cases. I find that restricting a claimant’s ability to present his or her case by scheduling a short hearing is breaching natural justice and procedural fairness. They must be given enough time to fully present their case, especially if a case is being perceived as potentially being a negative. (my emphasis, A-2018-03208, p. 2675)

Alongside case management strategies, Board leadership also intensified performance monitoring and management after 2017. A close look at performance objectives shows that Board management put tools in place to monitor various aspects of Board members’ work, such as percentage of cases finalized in a single sitting and average hearing times since 2015. Members’ individual performance were compared against their teams and region. In the post-2017 period, however, performance monitoring strategies were centralized, resulting in a shift of power from local and regional to the federal level. In line with the recommendations of the independent reviewer (Yeates, Citation2018), case targets were introduced for the first time in 2017–2018 performance objectives. In that fiscal year, new Board members with less than 12 months of experience were expected to finalize 80–90 claims, while regular members were required to complete 100–130 decisions or more. Finally, members who were part of the short hearing team needed to complete 150–180 finalizations. In following years, annual performance targets were fixed at 120 finalizations per year for all members (A-2018-01390 and A-2020-00599).

The tranformative approach requires attending to perceptions and first-hand experiences of Board members regarding performance objectives and targets. The Board’s internal correspondance and verbatim notes on regional focus-group discussions on member performance allow us to analyze expressions of power and different versions of reality. In early February 2018, the DC asked the three regional heads to invite Board members to discuss 2018–2019 performance objectives and “a well-rounded performance management approach” (A-2018-01390, p. 269). The excerpt below is from the opening script for focus group sessions led regionally by the ADCs and/or their delegates:

Management is committed to engaging members in a consultative process towards establishing well-founded and workable performance objectives…

This process of engagement of members in a conversation on the performance objectives should not be confused with co-development; management retains its right to define the performance objectives and members retain their rights under their collective agreement to grieve. (my emphasis, A-2018-01390, p. 276)

Focus in on quantity & timeliness. No documented regard to the quality of decisions, hearing room performance, questioning, etc. re the assessment process for quality…It should matter and be formally monitored… If management does not have time, then something is wrong. We’re set up to do numbers…It undermines morale & motivation. It is an organizational problem. (A-2018-01390, p. 411)

Uncovering attribution of ATI resources towards non-ATI responsibilities

Timely processing of ATI requests has been a major problem in Canada (Luscombe et al, Citation2017; Roberts, Citation2006; Thomas, Citation2010). For example, a recent journalistic investigation found that in the last three years, it took 83 days on average for federal government institutions to process an ATI request despite the 30-day statutory timeline.Footnote7 Below, I will explore how delays in processing ATI requests may be intertwined with the unauthorized exercise of power in public administration in closed spaces and how official complaint mechanisms can reveal it.

Being aware that many social scientists in Canada have encountered challenges related to delays in their ATI requests (Clément, Citation2017; Larsen & Walby, Citation2012; Luscombe et al., Citation2017; Roberts, Citation2002), when I made my 2018 ATI request, I followed a cooperative approach with the Refugee Board and it took four months to finalize. However, in 2020, when I submitted a similar request for performance monitoring documents, the ATI office informed me via formal letter that an extension of 1,001 days was necessary. After brokering with a senior analyst for several weeks and significantly narrowing the scope of my request, the extension was reduced to 190 days. Unsatisfied with this outcome, I filed a complaint with the ATI oversight agency in early October 2020, arguing that the 190-day extension was unjustified considering the reduced volume of documents I sought. My complaint was successful: the Information Commissioner confirmed it as well-founded and declared the Board’s extension as invalid.Footnote8

To provide context for the unreasonably lengthy 1,001-day extension, I turn to another successful complaint about a time extension decision. Since the latest legislative change in 2019, the Commissioner has been publishing the final reports of investigations when she deems them to be of value for government institutions and complainants. In a recent decision, the Commissioner examined the Board’s explanations for a 1,295-day extension to an ATI request which sought records related to the updated version of the Weighing Evidence document available on the Board’s website (OIC, Citation2022).

The Board described the required timeframe: covering 2 weeks for scanning and indexing records, 160 weeks for an ATI analyst to review the records, 10 weeks for ATI Management’s review, and 10 weeks for final approval, including input by legal services and senior management. Additionally, 3 extra weeks were given for potential delays, like technical issues. The Board cited a substantial increase in the volume of requests and a shortage of staff as reasons for the limited resources devoted to the initial review. Three out of six analyst positions were vacant when extension decision was made, and operational capacity was still being rebuilt. However, the Commissioner challenged the validity of the Board’s claim: “requests under the Act have in fact remained relatively consistent over the past two years (i.e. 161 requests made in 2021–2022 and 159 requests made in 2020–2021), and are down from the 228 access requests received in 2019–2020.” Further, the decision reported that the Board management had directed ATI resources towards non-ATI responsibilities, as analysts were:

“…expected to devote more time per month depersonalizing refugee decisions for online publication (i.e. 20 hours per month per analyst) than the number of hours devoted to reviewing records responsive to the current request (i.e. 12.5 hours per month by one analyst).” (OIC, Citation2022, para. 17)

Conclusion

FOI/ATI research is increasingly used by social scientists to gain insight into policy processes that are hidden from public view (Campbell, Citation2020; Clément, Citation2017; Duncan et al., Citation2023; Luscombe & Walby, Citation2017; Savage & Hyde, Citation2014). As students of public administration, we are uniquely equipped to conduct FOI/ATI research to obtain and examine information under the control of government institutions. The transformative approach developed in this article is relevant for not only unearthing “highly consequential decisions and policy maneuvers government officials make” (Walby & Luscombe, Citation2020, p. 2) but also for examining power dynamics in public administration. Analysing power in public administration, similar to other settings, is not only looking at domination, but also at “power as challenge to that domination” (Gaventa, Citation2021, p. 113). A transformative approach helps us dissect reported outcomes, to identify who influences and takes decisions, to see how policies are shaped and implemented, and to look at the tensions inherent in this process. Notwithstanding its lengthy and messy nature, FOI/ATI research is vital to undertake comprehensive and accurate understandings of public administration, as emphasized by Guy (Citation2021, p. 1102), who argued against “convenience research” conducted solely due to accessible data.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 See further information and examples at www.powercube.net.

3 Federal agencies are required to post summaries of disclosed ATI records on the open government website which offers a centralized platform for searching and requesting information from relevant institutions. See https://open.canada.ca/en/content/about-access-information-requests. Depending on the size of the release package, like initial disclosures, documents are sent electronically, by e-mail, on a CD or a USB key or in hard copy.

4 Furthermore, any refusal to disclose requested documents is subject to judicial review by the Federal Court of Canada. The OIC can also take the complainants’ cases to the court on their behalf (Thomas, Citation2010).

5 The Federal Court judgment was overturned on appeal and in Canadian Council for Refugees v. Canada (Citizenship and Immigration), 2023 SCC 17, the Supreme Court of Canada upheld that the SCTA is constitutional in part, regarding Section 7 of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, life, liberty and security of persons and sent the case back to the Federal Court to determine whether the agreement violated equality rights under Section 15.

6 This JG was subject to judicial review alongside others on Pakistan, China, and India. While the Federal Court of Appeal did not find that the JG pertaining to Nigeria was encroaching upon the Board member’s adjudicatory independence, it was revoked in 2020 (IRB, Citation2020).

7 See https://www.secretcanada.com.

8 Office of the Information Commissioner 5820-01524 / IRB A-2020-00599.

References

- Auditor General of Canada. (2019). Report 2—Processing of Asylum Claims Retrieved from https://www.oag-bvg.gc.ca/internet/English/parl_oag_201905_02_e_43339.html.

- Ball, C. (2009). What is transparency? Public Integrity, 11(4), 293–308. https://doi.org/10.2753/PIN1099-9922110400

- Campbell, J. R. (2020). Analyzing Public Policy in the UK: Seeing through the secrecy, obfuscation and obstruction of the FOIA by the Home Office. In K. Walby & A. Luscombe (Eds.), Freedom of information and social science research design (pp. 173–190). Routledge.

- Clément, D. (2017). The transformation of security planning for the Olympics: The 1976 Montreal Games. Terrorism and Political Violence, 29(1), 27–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2014.987342

- Duncan, J., Luscombe, A., & Walby, K. (2023). Governing through transparency: Investigating the new access to information regime in Canada. The Information Society, 39(1), 45–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/01972243.2022.2134241

- Freire, P. (2000 [1970]). Pedagogy of the Opressed (30th anniversary edition ed.). Continuum.

- Gaventa, J. (2006). Finding the spaces for change: A power analysis. IDS Bulletin, 37(6), 23–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1759-5436.2006.tb00320.x

- Gaventa, J. (2021). Linking the prepositions: using power analysis to inform strategies for social action. Journal of Political Power, 14(1), 109–130. https://doi.org/10.1080/2158379X.2021.1878409

- Gerblinger, C. (2023). Peep show: A framework for watching how evidence is communicated inside policy organisations. Evidence & Policy, 19(1), 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1332/174426421X16426978266831

- Guy, M. E. (2021). Expanding the Toolbox: Why the citizen-state encounter demands it. Public Performance & Management Review, 44(5), 1100–1117. https://doi.org/10.1080/15309576.2019.1677255

- Hamlin, R. (2014). Let me be a refugee: Administrative justice and the politics of asylum in the United States, Canada and Australia. Oxford University Press.

- Haugaard, M. (2012). Rethinking the four dimensions of power: domination and empowerment. Journal of Political Power, 5(1), 33–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/2158379X.2012.660810

- IRB. (2018). IRB Plan of Action for Efficient Refugee Determination. Retrieved from https://irb.gc.ca/en/legal-policy/procedures/pages/IRB-plan_action.aspx.

- IRB. (2018–2019). Departmental Results Report. Retrieved from https://irb.gc.ca/en/reports-publications/planning-performance/Pages/departmental-results-report-1819-r.aspx.

- IRB. (2019). Instructions governing the streaming of less complex claims at the Refugee Protection Division. Retrieved from https://irb.gc.ca/en/legal-policy/policies/Pages/instructions-less-complex-claims.aspx.

- IRB. (2020). Notice of Revocation of Jurisprudential Guide—Nigeria. Retrieved from https://irb.gc.ca/en/legal-policy/policies/Pages/revocation-tb7-19851.aspx.

- IRB. (2023). Refugee Claims Statistics. Retrieved from https://irb.gc.ca/en/statistics/protection/Pages/index.aspx.

- Johnson, N. J., & Svara, J. H. (2015). Social equity in American society and public administration. In N. J. Johnson & J. H. Svara (Eds.), Transformational trends in governance and democracy. Justice for all (pp. 3–25). promoting social equity in public administration. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315703060

- Kabeer, N. (1994). Reversed realities: Gender hierarchies in development thought. London Verso Books.

- Larsen, M., & Walby, K. (Eds.). (2012). Brokering access: Power, politics, and freedom of information process in Canada. University of British Columbia Press.

- Long, N. E. (1949). Power and administration. Public Administration Review, 9(4), 257–264. https://doi.org/10.2307/972337

- Luscombe, A., & Walby, K. (2017). Theorizing freedom of information: The live archive, obfuscation, and actor-network theory. Government Information Quarterly, 34(3), 379–387. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2017.09.003

- Luscombe, A., Walby, K., & Lippert, R. (2017). Brokering Access Beyond the Border and in the Wild: Comparing Freedom of Information Law and Policy in Canada and the United States. Law & Policy, 39(3), 259–279. https://doi.org/10.1111/lapo.12080

- McGee, R., & Pettit, J. (Eds.). (2019). Power, empowerment and social change. Taylor & Francis.

- Mertens, D. M. (2021). Transformative research methods to increase social impact for vulnerable groups and cultural minorities. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 20, 160940692110515. https://doi.org/10.1177/16094069211051563

- Nabatchi, T. (2022). Between a rock and a hard place: (Re)Integrating public administration and political science. Governance, 35(4), 991–998. https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12732

- Ntienjom Mbohou, L. F., & Tomkinson, S. (2022). Rethinking ‘elite’ interviews through moments of discomfort: The role of information and power. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 21. https://doi.org/10.1177/16094069221095312

- OIC. (2021). Frequently asked questions: Implementation of Bill C-58. Retrieved from https://www.oic-ci.gc.ca/en/frequently-asked-questions-implementation-bill-c-58.

- OIC. (2022). Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada (Re), 2022 OIC 42. Retrieved from https://www.oic-ci.gc.ca/en/decisions/final-reports/immigration-and-refugee-board-canada-re-2022-oic-42.

- OPC. (2021). Submission of the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada to the President of the Treasury Board. https://www.priv.gc.ca/en/opc-actions-and-decisions/submissions-to-consultations/sub_tbs_210217/.

- Peters, B. G., Pierre, J., Sørensen, E., & Torfing, J. (2022). Bringing political science back into public administration research. Governance, 35(4), 962–982. https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12705

- Roberts, A. (2002). Administrative discretion and the Access to Information Act: An “internal law” on open government? Canadian Public Administration/Administration Publique du Canada, 45(2), 175–194. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1754-7121.2002.tb01079.x

- Roberts, A. (2006). Blacked out: Government secrecy in the information age. Cambridge University Press.

- Savage, A., & Hyde, R. (2014). Using freedom of information requests to facilitate research. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 17(3), 303–317. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2012.742280

- Smith, C. D. (2022). Policy change, threat perception, and mobility catalysts: The trump administration as Driver of Asylum Migration to Canada. International Migration Review, 2022, 019791832211124. https://doi.org/10.1177/01979183221112418

- Sowa, J. E., & Lu, J. (2017). Policy and management: Considering public management and its relationship to policy studies. Policy Studies Journal, 45(1), 74–100. https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12193

- Thambinathan, V., & Kinsella, E. A. (2021). Decolonizing methodologies in qualitative research: Creating spaces for transformative praxis. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 20, 160940692110147. https://doi.org/10.1177/16094069211014766

- Thomas, P. G. (2010). Advancing access to information principles through performance management mechanisms: The Case of Canada. The World Bank.

- Tomkinson, S. (2018). Who are you afraid of and why? Inside the Black Box of Refugee Tribunals. Canadian Public Administration, 61(2), 184–204. https://doi.org/10.1111/capa.12275

- Tomkinson, S., & Cloutier, A. (2022). Représentations médiatiques des jeunes demandeurs d’asile « irréguliers » au Québec et au Canada. Hommes & Migrations, 2022(1336), 99–106. https://doi.org/10.4000/hommesmigrations.13643

- UNESCO. (2019). Powering sustainable development with access to information: highlights from the 2019 UNESCO monitoring and reporting of SDG indicator 16.10.2. Retrieved from https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000369160.

- Walby, K., & Luscombe, A. (Eds.). (2020). Freedom of Information and Social Science Research Design. Routledge.

- Yeates, N. (2018). Report of the Independent Review of the Immigration and Refugee Board: A Systems Management Approach to Asylum.

- Zavattaro, S. M. (2021). Why is this so hard?: An autoethnography of qualitative interviewing. Public Performance & Management Review, 44(5), 1052–1074. https://doi.org/10.1080/15309576.2020.1734035