Abstract

Background: There is a growing need to support the health and wellbeing of older persons aging in the context of migration.

Objectives: We evaluated whether a group-based health promotion program with person-centred approach, maintained or improved life satisfaction and engagement in activities of older immigrants in Sweden.

Methods: A randomised controlled trial with post-intervention follow-ups at 6 months and 1 year was conducted with 131 older independently living persons aged ≥70 years from Finland and the Balkan Peninsula. Participants were randomly allocated to an intervention group (4 weeks of group intervention and a follow-up home visit) and a control group (no intervention). Outcome measures were life satisfaction and engagement in activities. Chi-square and odds ratios were calculated.

Results: The odds ratios for maintenance or improvement of life satisfaction (for social contact and psychological health) were higher in the person-centred intervention group. More participants in the intervention group maintained or improved their general participation in activities compared with the control group. However, no significant between-group differences were found.

Conclusion: Person-centred interventions can support older person’s capability to maintain their health in daily life when aging in migration. Further research is needed with a larger sample and longer intervention period to determine the effectiveness of the intervention.

Introduction

An occupational perspective on health focuses on a person’s abilities to engage in necessary, important and meaningful occupations in everyday life [Citation1]. Occupations are performed in a specific environment and context and are named by the culture in which they are carried out [Citation1,Citation2]. Persons aging in a context of migration experience cultural changes that may affect their health and life satisfaction. An occupational perspective on health considers whether a person perceives himself or herself as a capable person [Citation3,Citation4] and can use resources to achieve important life goals [Citation5]. Older persons’ self-assessments of health indicate that they experience health and wellbeing despite the decline and weaknesses that the aging process entails [Citation6,Citation7]. According to Melin [Citation8], life satisfaction is a core aspect of older persons’ experiences of health and wellbeing in daily life. Life satisfaction refers to a subjective sense of contentment with life. It incorporates not only health-related issues, but also issues dealing with the cultural, social and financial aspects of daily life [Citation9]. Humans have an innate drive to be active and participate in occupations [Citation10,Citation11]. Engagement in occupations contributes to life satisfaction and is strongly connected with a person’s experience of health and wellbeing [Citation12–14]. Occupational engagement also increases the sense of pleasure in life [Citation15] and there is a positive relation between occupational engagement and a sense of meaning in life in older persons [Citation15,Citation16]. Migration is usually considered a risk factor for health [Citation17,Citation18]. First-generation immigrants have lower life satisfaction in several different areas than most native-born persons [Citation19]. There are inequalities in health status between persons with an immigrant background and native-born older persons of the same age [Citation20] due to sociodemographic differences i.e poverty and low-paid jobs [Citation21]. Additionally, this group of older persons are also described as a homogeneous group with similar needs of health care services [Citation22].

Research also indicates that older immigrants who engage in fewer leisure activities have lower life satisfaction than older immigrants who engage in more leisure activities [Citation23]. Lack of engagement in activities also reduces the sense of meaning in life [Citation24,Citation25]. The functional decline inherent in the aging process can influence an individual’s daily life, life satisfaction and the ability to engage in valued activities [Citation13]. Health promotion interventions can be used to strengthen, support [Citation26] and maintain health and thus improve life satisfaction in daily life [Citation19]. Additionally, health promotion with a person-centred approach [Citation27] may be useful due to its possibilities to recognize the heterogeneity in this group of older persons. The philosophical base in the person-centred approach is to see human beings as capable persons [Citation4,Citation28] who possess the resources to be in charge of their own lives. Previous research has demonstrated positive effects of health promotion interventions for older native born persons [Citation29,Citation30]. Clark et al. [Citation31] have conducted a health promotion study of ethnically diverse older persons and identified positive outcome and Lood [Citation32] found a person-centred health promotion being beneficial for older persons born abroad.

However, research on health promotion strategies for persons aging in a place other than their country of origin is scarce [Citation33] and there is limited knowledge about health care and health promotion for older persons aging in the context of migration [Citation34]. Older persons with an immigrant background are often excluded from research projects; this occurs mainly because of linguistic and sociocultural barriers, but also because of attitudes among health care providers [Citation35]. More research is needed to investigate the effects of health promotion intervention, with a person-centred approach, for older persons aging in the context of migration. The person-centred approach creates an interaction between the older person receiving the service and the professionals who are providing the service [Citation32]. Thus the decisions made in the intervention is based on a partnership between the older person and professionals [Citation28], with the respect to the person’s own capability and needs. In this study, participants were older persons with a background of immigration. The aim was to analyse the effects of a person-centred health promotion intervention on life satisfaction and engagement in activities among older immigrants aging in a Swedish context.

Material and Methods

The study Promoting Aging Migrants’ Capability (PAMC) was a randomised controlled trial with an intervention group and a control group. Participants were independently living older persons 70 years or older who had migrated to Sweden from Finland and the Balkan Peninsula. The present study concerns the 6-month and 1-year follow-ups. The regional Ethical Review Board approved the study (Reg. no.: 821-11) and the trial has been registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01841853).

Procedure, participants and settings

Participant recruitment comprised three hierarchical wave, where eligible participants were recruited differently in each wave. In the first wave, participants were randomly selected from official registers in one suburban district of a medium-sized town in Sweden. As the target inclusion rate was not achieved in the first wave, a second sampling wave was conducted. This sampling wave used the same procedure as in the first wave but used official registers from another suburban area with similar demographics. In these two waves, individuals were sent letters, which included a description of the study, how it would be conducted and what was expected of participants, and which stated that participation was voluntary. Eligible individuals were telephoned 1–2 weeks after the letters had been posted (if no telephone number was available, a new letter was sent). Additionally, snowball sampling [Citation36] was used as a third sampling step to recruit more participants from the target groups. The third wave was conducted by previous participants in the program and by key persons in the reference group, who advertised the study to potential participants. In addition, the study was advertised by advertisements on local radio. Persons interested in the program were invited to contact the research leader for further information, and these individuals were then assessed on the inclusion criteria by trained research assistants. The assessments and information about the study were conducted in the participants’ preferred language.

Eligible participants were persons aged 70 years or older who had migrated from Finland or from the Balkan Peninsula, including Bosnia–Herzegovina, Croatia, Montenegro and Serbia. The inclusion criteria were as follows: independent of others’ help in activities of daily living, as measured by the ADL-staircase [Citation37,Citation38], and living in ordinary housing in an urban district. The exclusion criterion was impaired cognition. Individuals who scored less than 80% on administered items from the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) [Citation39] at baseline were excluded and referred to appropriate health care services. In total, 131 persons fulfilled the inclusion criteria and consented to participate; 88 participants were allocated in the first wave, 37 participants in the second wave and 6 participants in the third wave. The study protocol contains additional information about the recruitment process [Citation34].

The health promotion intervention was conducted in two suburban areas conveniently located for the first and second recruitment waves. Most inhabitants in the areas of the first and second recruitment waves had been born abroad. These areas are characterised by lower income and educational level compared with the overall levels in the district ().

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of participants at baseline.

Data were collected during 2012–2016. Members of the interdisciplinary team, or a research assistant trained in the assessments, conducted the assessments at baseline. The research assistants conducted the follow-up assessments at 6 months and 1 year post-intervention.

Sample size, random allocation and blinding

A power calculation was performed based on one of the secondary outcome measures of the PAMC study, the Berg Balance Scale [Citation34]. To reach a power of 80%, a significance level of α = 0.05 was needed and to detect a difference of ≥15% between the groups, each study arm required a sample of 65 participants. The random allocation was stratified to enrol an equal amount of people from Finland and from any of the selected four countries in the Balkan Peninsula: Bosnia–Herzegovina, Croatia, Montenegro and Serbia. After the baseline assessment, participants were randomly assigned to the intervention group (IG) or to the control group (CG) using opaque, sealed envelopes. A researcher uninvolved in the enrolment or the intervention organised the randomisation, which was performed after baseline assessment. To enable blinding of the assessments at baseline and follow-ups, different persons conducted the assessments [Citation34].

Interventions

Senior group meetings with one follow-up home visit

The intervention consisted of four group meetings, named senior meetings (SM), held over a period of four weeks. The participants were from two language groups, Finnish and Serbo-Croatian, and separate group meetings were held for both language groups. Each meeting lasted for 1,5-2 hours. Additionally, the participants were offered a follow-up home visit two to three weeks after the last SM. Before the meetings, a written booklet in the participants’ native language supplied written evidence-based information about health-related issues. This booklet was used as a trigger to open up reflections about general challenges related to aging and health in daily life. Participants were encouraged to read the written information beforehand so that they had the opportunity to reflect on the various issues from a personal perspective. The interdisciplinary team, consisted of an occupational therapist, a physiotherapist, a registered nurse and a social worker. One of the professionals acted as a group leader of the meetings in order to create continuity and to stimulate the group discussions. The intention by using a person-centred approach [Citation40] was to promote a shift of power from the group leader to the participants in order to facilitate the partnership between the participants in the senior meetings but also between the participants and the professionals. The meetings started with the professionals introducing one of the topics mentioned in the booklet. The participants then discussed the relevance of the topic regarding their experiences from everyday life and how it would impact their current resources to manage daily life.

During the meetings, the participants was encouraged to narrate who they are and how they perceived their capability in daily life. These narrations stimulated the group discussion, exchange of experiences and peer-learning between the participants [Citation41]. The study protocol contains detailed information about the content of the booklet and the responsible professionals [Citation34]. A bilingual approach was used meaning that participants chose their preferred language of communication. An interpreter was incorporated into the team when needed. To maintain the dynamic in the group, simultaneous interpretation was used according to preferences within the group. Thus, meetings could be held in Swedish, the participants’ mother tongue, or a combination of both. The follow-up home visits were conducted by one of the professionals who had conducted the SM. These follow-up visits gave the participants the opportunity to pose any individual questions that had occurred to them after the last meeting.

The SM was implemented according to the plan described in study protocol [Citation34]. A total of 57% (n = 32) of participants attended four SMs, 16% (n = 9) attended three SMs, 9% (n = 5) attended two SMs and 11% (n = 6) attended one SM. Four participants did not attend any SMs.

Control group

Participants in the control group (CG) did not receive any intervention. However, they had access to ordinary health care services, which they could contact as they wished. At baseline or follow-up, participants were given information about where to access health care if they required it urgently.

Outcomes

Life satisfaction

The primary outcome measure for this study was life satisfaction measured using the validated Life Satisfaction Assessment LiSat-11 [Citation19]. The LiSat-11 focuses on important life domains, such as financial and vocational situation, self-care management, contact with family and friends and global life satisfaction. Participants are asked to respond to each item by estimating their level of satisfaction, scored on a 6-point scale from 1 (very dissatisfied) to 6 (very satisfied). In this study, items on sexual life (item 6), family life (item 8) and partner relations (item 9) were excluded, producing eight items. This exclusion was based on previous experiences, which indicated that these items would be too sensitive for the target study population [Citation42]. The scores were dichotomised; scores of 1 to 4 indicated ‘not satisfied’ and scores >4 indicated ‘satisfied’ [Citation43,Citation44].

Engagement in activities

A questionnaire was used to assess engagement in 18 activities categorised into four domains: solitary-sedentary activities, such as watching TV, following the news, reading a book or completing a crossword puzzle; solitary-active activities, such as gymnastics, gardening or walking; social-cultural activities, such as going to the cinema or concerts or visiting a museum; and social-friendship activities, such as visiting friends, travelling and association membership activities [Citation45,Citation46]. Participation in these activities was rated on a 3-point scale: 1 (yes, often/regularly), 2 (yes, sometimes) and 3 (never). The response alternatives were then dichotomised into 1 (yes, often/regularly and yes, sometimes) and 0 (never). visualizes the categorisation.

Table 2. Proportion of participants and comparison of engagement in activities at baseline in CG and IG.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive and inferential statistics were used to compare the IG and CG groups on temporal changes in life satisfaction and engagement in activities at 6-month and 1-year follow-up. Chi-square test was used to analyse differences in the proportion of participants who had maintained or improved in outcome measures at follow-ups. Then the odds ratio (OR) was calculated in order to measure the odds for change between the groups in life satisfaction and engagement in activities. All statistical tests were two-sided with a significance of p ≤ 0.05. Data were analysed using SPSS version 24 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, 2009). Analyses were conducted according to the intention-to-treat principle, which required that all participants were analysed in the group to which they were randomly allocated [Citation47]. To ensure that the results were as comprehensive as possible, analyses were conducted by imputing missing values, assuming that life satisfaction is expected to deteriorate over time owing to normal aging. Therefore, the imputation method of median change of deterioration (MCD) was used for those lost to follow-up. MCD can be considered a form of worst change analysis [Citation48]. The MCD for the outcome measure was added to the individual value recorded at baseline, and imputed, substituting missing values at follow-up. For participants with missing values on more than one follow-up, the imputation was calculated from baseline to 6 months and from 6-month to 1-year follow-up.

Results

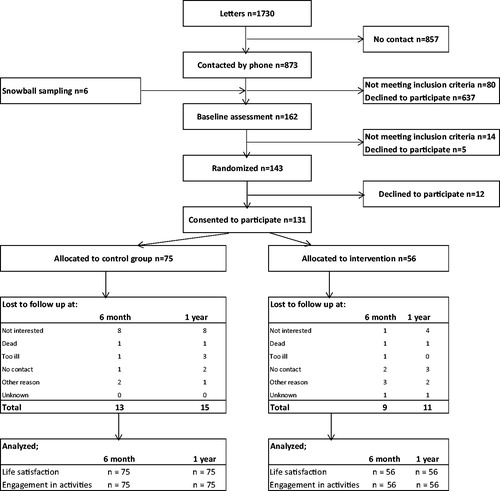

Baseline assessment was performed for 162 people, and 131 satisfied the inclusion criteria and consented to participate ().

Figure 1. The flow of participants through promoting aging migrants’ capabilities study and the reasons for declining participation at 6 months and 1 year follow-ups.

There were no statistically significant differences on demographic characteristics at baseline between the intervention group (IG) and control group (CG) ().

The dropout rate at 6 months was 17% (n = 22) and at 1-year follow-up was 20% (n = 26). There were no significant between-group differences in dropout rates. The main reason for dropout was a loss of interest in participation. At 6-month follow-up, there was a significantly higher proportion of dropouts among males. There was also a higher proportion of dropouts among participants born in the Balkan Peninsula, both at 6-month and 1-year follow-ups. Additionally, compared with participants who completed the study, those who dropped out contained a lower proportion of persons who scored ≥25 on the MMSE (at both 6 months and 1 year), who lived alone (at 6 months) and who rated their language ability as good (at 1 year) ().

Table 3. Differences in proportion of dropouts and participants at 6 months and 1 year.

Life satisfaction

There were no significant between-group differences at baseline on life satisfaction ().

Table 4. Amount of participants who evaluate their life satisfaction as satisfactory at baseline.

There were no statistically significant between-group differences in the odds for maintenance or improvement of life satisfaction (as assessed by the LiSat) at 6-month and 1-year follow-up. At 6 months, the ORs were higher in the IG for maintenance or improvement of life satisfaction on most of the items, except of “life as a whole”, leisure” and “physical health”. At 1-year follow-up, a greater proportion of participants in the IG had maintained or improved their life satisfaction with vocational situation (OR: 1.61; CI: 0.79–3.30), contact with friends (OR: 1.67; CI: 0.79–3.50) and psychological health (OR: 1.54; CI: 0.76–3.12) compared with the CG group (OR: 1.00) ().

Table 5. Proportion (%), odds ratio (OR), 95% confidence interval (CI), and p-value for maintenance or improvement of life satisfaction at 6 months and 1 year followup between control group and intervention group.

Engagement in activities

There were no significant between-group differences at baseline in engagement in activities ().

At 6-month and 1-year follow-up, there were no statistically significant between-group differences in odds for maintenance or improvement of engagement in activities. A comparison between baseline and 6-month follow-up showed that, compared with CG participants, a greater proportion of IG participants maintained or improved engagement in some of the activities: some/any of the 17 activities (OR: 1.76; CI: 0.80–3.84), social/cultural activities (OR: 1.61; CI: 0.60–4.29) and social/friendship activities (OR: 1.31; CI: 0.53– 3.24). At 1 year, the ORs were higher in the IG for maintenance or improvement of engagement in solitary-sedentary activities (OR: 1.57; CI: 0.50–4.88) and in social-cultural activities (OR: 1.29; CI 0.58-2.86) compared with CG participants (OR: 1.00) ().

Table 6. Proportions of persons engaged in activities at 6 months and 1-year post intervention and corresponding ORs.

Discussion

In this study, we evaluated the effect of a health promotion group intervention, with a person-centred approach, on life satisfaction and engagement in activities. Although the findings were not significant, some participants benefited from the health promotion intervention, indicating that this type of intervention might be useful and clinically relevant. One year after the intervention, the ORs for maintenance or even improvement of life satisfaction were higher in the person-centred IG than in the CG group. This was particularly so for domains related to social relationships, ability to engage in activities and psychological wellbeing. Although the findings lacked significance, the overall pattern of results is in accord with previous research findings. Clark et al. [Citation31] and Wilhelmson & Eklund [Citation49] showed that group intervention for older persons was effective in supporting life satisfaction. The difference in this study compared with the findings in Clark et al. [Citation31] is that our interventions were shorter, thus this can be an explanation for the non-significant results. With a longer implementation time, the findings may have shown more improvement.

Additionally, Ekström et al. [Citation50] and Gallagher et al. [Citation51] highlighted the important connections between activities and social contact and the impact of activities on life satisfaction. The odds for maintenance of life satisfaction 1 year post-intervention, and the association between life satisfaction and health resources, both indicate that SM with a the person-centred approach can support life satisfaction and health among older persons aging in the context of migration. The person-centred approach creates encounters in which older persons with an immigrant background are seen as a capable person with the resources to identify their own health resources, which leads to satisfaction with everyday life. This approach also supports peer learning, because participants are able to share experiences and good examples; a finding that has been demonstrated by previous research on group interventions [Citation52]. Moreover, the partnership between participants and professionals in an intervention with a person-centred approach creates a high level of interaction [Citation32] which reinforces the participants’ awareness of their personal health resources.

Nevertheless, since the intervention did not show any significant differences between the groups, it is also appropriate to reflect on the intervention itself. Was the intervention too general? Did it not capture the aspects, which would be relevant to support life satisfaction and engagement in activities among the participants, meaning that the intervention was not person-centred enough? Certainly, this could be the case. However, findings in qualitative studies indicates that participants in a person-centred group intervention experience that the intervention actually raises their awareness about their own health resources in daily life [Citation53]. Seen from this point of view, even if the results were not significant, it indicates that the group intervention with a person-centred approach had a positive effect on the participants’ life satisfaction.

The results on engagement in activities showed an interesting pattern. Although these results were not significant, at 6-month follow-up, the ORs for maintenance or improvement in activity engagement in some/any activity of interest for IG were 1.76 times higher than in the CG group. However, the odds for maintenance or improvement did not persist to the 1-year follow-up. Instead, the pattern of engagement in activities had shifted and the range of activities had narrowed. At 1-year follow-up, IG participants engaged in activities that could be conducted in the home environment (solitary-sedentary activities), but also in special interest activities, such as social-cultural activities. Nilsson, Häggström-Lundevaller and Fisher [Citation54] have suggested that as persons are ageing, their leisure activities become more critical because they have limited energy available for several activities. The change in activities showed by our IG participants may have been a strategy to save energy and prioritise activities that they found more meaningful at the expense of engaging in a broader range of activities. An alternative reason for this narrowing of the activity repertoire is that the intervention increased participants’ awareness of the risks and hazards of old age. They might have been more cautious in engaging in leisure activities outside the home, where the environment might be more challenging.

Methodological considerations

The randomised controlled design is a strength of the study; however, the intervention did not show any significant results for either life satisfaction or engagement in activities. Several reasons for the lack of significant results can be discussed. Firstly, a main reason was the difficulties in the recruitment process. Even with three different recruitment steps, it was not possible to obtain more participants. This affected the power of the study. There are several possible explanations for these recruitment difficulties. One is a distrust of health care providers among older persons with an immigrant background. This has been found in qualitative studies on health perceptions in older persons aging in the context of migration [Citation55]. Another possible reason for the recruitment difficulties is the age of participants. The age limit was set at 70 years or older, which was probably too low. This cutoff was based on previous research indicating that older immigrants have poorer health compared with native-born older persons [Citation18,Citation56]. Other similar studies conducted with native-born older persons have used an age limit of 80 years or older [Citation42] and have found significant results for life satisfaction. The lower age limit may have meant that participants were reasonably healthy with no frailty. Therefore, they probably did not yet need health promotion interventions. Secondly, the non-significant results might have been caused by the imbalance in the number of participants in the SM and CG groups. During the random allocation process, more participants in the SM group declined participation compared with the CG group. However, the groups were similar on demographic characteristics. If full power had been reached for both study arms, the results may have been different. The low number of participants, in combination with dropouts, may also have affected the internal validity of the results. A third reason for non-significant results might be connected to the measures used, especially the checklist which was used to measure engagement in activities. This checklist might not be sensitive enough when it comes to measuring change over time. In contrast, the instrument used to measure life satisfaction is a validated instrument and the results at follow-up can be considered as giving a correct result. Finally, the non-significant results might be influenced by the fact that the control group was also assessed at follow-ups. This might have created a Hawthorne effect where the participants change their natural behaviour just because they are participating in a study [Citation57].

The analyses were based on the intention-to-treat principle and the MCD imputation method was used, based on the assumption that as persons age, they experience a decline in life satisfaction and engagement in activities. A different imputation method might have produced different results, but it is important to note that there is no universal imputation method that guarantees the most accurate results [Citation52]. The results might also have been affected by the fact that a larger proportion of male participants from the Balkan Peninsula dropped out. The main reason for dropout at follow-up was a loss of interest in participation. Participants may not have found the intervention interesting enough because of the themes raised. The themes and the booklet were translated from the Swedish SMs version [Citation30], and participants may have felt that some of the themes were not relevant or meaningful to them. Thus, participants may have been unsure how the intervention could support health in everyday life. Even if the booklet had been translated and discussed with a reference group, we might still not have captured the person-centred approach enough to capture the interest and needs of the participants sufficiently. Despite the fact that the intervention intended to be person-centred, it may have been more in a form of professional-centred practice [Citation58], which indicates that the content and process was led by the professionals and not merely by the interest and needs of the participants? However the qualitative research [Citation53] showed that the person-centred approach contributed to viewing the participants as people being able to shape the content according to each persons experienced needs influenced jointly by personnel and other participants.

This study was implemented in an area in which most inhabitants are immigrants. The groups were similar on sociodemographic characteristic. This indicates satisfactory external validity. However, the results should be interpreted with caution owing to several difficulties with enrolment and dropouts, which led to a lack of power. Further research is needed to achieve adequate power in a person-centred health promotion intervention targeting older persons aging in the context of migration. Future research should focus on how to overcome problems with recruitment of older immigrants. The content of the intervention should also be validated to ensure its themes reflect the needs and interests of older persons aging in the context of migration.

Conclusions

Although the results were not significant, they may have important implications for clinical practice. The pattern of results indicates that it is possible to maintain life satisfaction and support engagement in activities among older persons aging in the context of migration. A group-based and person-centred approach can encourage older person’s to reveal their own perspectives on health, life satisfaction and activity engagement. This enables them to effectively use their own capabilities and thus maintain and support their health in everyday life. A person-centred approach in health promotion interventions can help to develop older immigrants’ health-maintenance abilities.However, further studies with a larger number of participants and with a longer intervention period is needed to be able to detect the effectiveness of a group intervention with a person-centred approach on older person’s life satisfaction and engagement in occupations when aging in migration context.

Ethical approval

This work was financially supported by the Hjalmar Svensson Foundation and University of Gothenburg Centre for Person-Centerd care (GPCC), (htpp://www.gpcc.gu.se). GPCC is funded by the Swedish Government's grant for Strategic Research Areas, Care sciences (Application to Swedish Research Council nr 2009-1088) and co-funded by the university of Gothenburg.

Acknowledgment

The funders played no role in the execution or writing of the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Yerxa EJ. Health and the human spirit for occupation. Am J Occup Ther. 1998;52:412–418.

- Law M, Polatajko H, Baptiste S, et al. Core concepts of occupational therapy. In: Townsend E, editor. Enabling occupation: an occupational therapy perspective. Ottawa: Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists; 1997. p. 29–56.

- Nordenfelt L. Hälsa och värde: studier i hälso- och sjukvårdens teori och etik. [Health and value: studies in the theory and ethics of health care]. Stockholm: Thales; 1991.

- Ricoeur P, Backelin E. Homo capax: texter av Paul Ricoeur om etik och filosofisk antropologi. [Homo capax: texts by Paul Ricoeur about ethics and philosophical anthropology]. Göteborg: Daidalos; 2011.

- Venkatapuram S. Health justice. Cambridge: Polity Press; 2011.

- Ebrahimi Z, Wilhelmson K, Eklund K, et al. Health despite frailty: exploring influences on frail older adults’ experiences of health. Geriatr Nurs. 2013;34:289–294.

- Arola LA, Dellenborg L, Häggblom-Kronlöf G. Occupational perspective of health among persons ageing in the context of migration. J Occup Sci. 2018; 25:65–75.

- Melin, R. On life satisfaction and vocational rehabilitation outcome in Sweden [Doctoral thesis]. Uppsala: University print; 2003.

- Calvo R, Carr DC, Matz-Costa C. Another Paradox? The life satisfaction of older Hispanic immigrants in the United States. J Aging Health. 2017;29:3–24.

- Wilcock AA, Hocking C. An occupational perspective of health. Thorofare, N.J: Slack; 2015.

- Häggblom-Kronlöf, G, Hultberg, J, Eriksson, et al. Experiences of daily occupations at 99 years of age. Scan J Occup Ther. 2007;14:192–200.

- Hocking C. Contribution of occupation to health and well-being. In: Boyt Schell, B. A., Gillen G, Scaffa, M, Cohn ES, editors. Willard and Spackman's occupational therapy. 12th ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins cop; 2013.

- Kielhofner G. Model of human occupation: theory and application. 4th ed. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007.

- Nilsson I, Fisher AG. Evaluating leisure activities in the oldest old. Scand J Occup Ther. 2006;13:31–37.

- Low G, Molzahn AE. Predictors of quality of life in old age: a cross‐validation study. Res Nurs Health. 2007;30:141–150.

- Eakman AM, Carlson ME, Clark FA. The meaningful activity participation assessment: a measure of engagement in personally valued activities. Int J Aging Hum Dev. 2010;70:299–317.

- Statens Folkha¨lsoinstitut. Fo¨delselandets betydelse: En rapport om ha¨lsan hos olika invandrargrupper i Sverige. [The importance of the country of birth: A report on the health of different immigrant groups in Sweden] Stockholm: Statens Folkha¨lsoinstitut; 2002.

- Hjern A. Migration and public health: health in Sweden: The National Public Health Report 2012. Chapter 13. Scan J Publ Health. 2012;40:255–267.

- Fugl-Meyer KS. Life satisfaction in 18- to 64-year-old Swedes: in relation to gender, age, partner and immigrant status. J Rehab Med. 2002;34:239–246.

- Myndigheten för vårdanalys. En mer ja¨mlik vård a¨r mo¨jlig: Analys av omotiverade skillnader i vård, behandling och bemo¨tande. [A more equal care is possible: analysis of unjustified differences in care, treatment and encounters]. Stockholm: Myndigheten fo¨r vårdanalys; 2014.

- Socialstyrelsen. Vård och omsorg om äldre. [Care and welfare of older persons]. Stockholm: Socilastyrelsen; 2009.

- Torres S. Elderly immigrants in Sweden: 'Otherness' under construction. J Ethn Migr Stud. 2006;32:1341–1358.

- Kim MS. Life satisfaction, acculturation, and leisure participation among older urban Korean immigrants. World Leisure J. 2000;42:28–40.

- Chang P-J, Wray L, Lin Y. Social relationships, leisure activity, and health in older adults. Health Psychol. 2014;33:516–523.

- Hedberg P, Gustafson Y, Brulin C. Purpose in life among men and women aged 85 years and older. Int J Aging Hum Dev. 2010;70:213–229.

- Korp P. Vad är hälsopromotion? [What is health promotion]. Lund: Studentlitteratur; 2016.

- Ekamn, I. Personcentrering inom hälso- och sjukvård: från filosofi till praktik. [Personcenterdness in healthcare]. Stckholm: Liber AB; 2014.

- Ekman I, Swedberg K, Taft C, et al. Person-centered care-ready for prime time. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2011;10:248–251.

- Gustafsson S, Eklund K, Wilhelmson K, et al. Long-term outcome for ADL following the health-promoting RCT-elderly persons in the risk zone. Gerontologist. 2013;53:654–663.

- Gustafsson S, Wilhelmson K, Eklund K, et al. Health‐promoting interventions for persons aged 80 and older are successful in the short term—results from the randomized and three‐armed elderly persons in the risk zone study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:447–454.

- Clark F, Jackson J, Carlson M, et al. Effectiveness of a lifestyle intervention in promoting the well-being of independently living older people: results of the Well Elderly 2 Randomised Controlled Trial. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2012;66:782–790.

- Lood Q, Gustafsson S, Dahlin Ivanoff S. Bridging barriers to health promotion: a feasibility pilot study of the ‘Promoting Aging Migrants' Capabilities study’. J Eval Clin Pract. 2015;21:604–613.

- Lood Q, Häggblom-Kronlof G, Dahlin-Ivanoff S. Health promotion programme design and efficacy in relation to ageing persons with culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:560.

- Gustafsson S, Lood Q, Wilhelmson K, et al. A person-centred approach to health promotion for persons 70+ who have migrated to Sweden: promoting aging migrants’ capabilities implementation and RCT study protocol. BMC Geriatr. 2015;15:10.

- Hussain-Gambles M, Atkin K, Leese B. Why ethnic minority groups are under‐represented in clinical trials: a review of the literature. Health Soc Care Community. 2004;12:382–388.

- Sadler, G, Lee, H, Lim, R, et al. Recruitment of hard-to-reach population subgroups via adaptations of the snowball sampling strategy. Nurs Health Scien. 2010;12:369–374.

- Hulter Åsberg K. ADL-trappan. [ADL-staircase]. Lund: Studentlitteratur; 1990.

- Sonn U. Longitudinal studies of dependence in daily life activities among elderly persons: methodological development, use of assistive devices and relation to impairments and functional limitations. Scan J Rehab Med. 1996;28:1–35.

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini- mental state. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198.

- Ekman I, Norberg A, Swedberg K. Tillämning av personcentrering inom hälso- och sjukvård. In: Ekman I, ed. Personcentrering inom hälso- och sjukvård. [Adaptation of person-centred care in healthcare. In Ekman, I. Personcenterdness in healthcare]. Stockholm: Liber AB; 2014.

- Barenfeld E, Wallin L, Björk Brämberg E. Moving from knowledge to action in partnership: A case study on program adaptation to support optimal aging in the context of migration. J Appl Gerontol. 2017;30:1–26.

- Berglund H, Hasson H, Kjellgren K, Wilhelmson K. Effects of a continuum of care intervention on frail older persons’ life satisfaction: a randomized controlled study. J Clin Nurs. 2015;24:1079–1090.

- Borg T, Berg P, Fugl-Meyer K, Larsson S. Health-related quality of life and life satisfaction in patients following surgically treated pelvic ring fractures. A prospective observational study with two years follow-up. Injury. 2010;41:400–404.

- Fugl-Meyer A, Bränholm I, Fugl-Meyer K. Happiness and domain-specific life satisfaction in adult northern Swedes. Clin Rehab. 1991;5:25–33.

- Lennartsson C, Silverstein M. Does engagement with life enhance survival of elderly people in Sweden? The role of social and leisure activities. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sc. 2001;56:335–342.

- Häggblom-Kronlöf G, Sonn U. Interests that occupy 86‐year‐old persons living at home: associations with functional ability, self‐rated health and sociodemographic characteristics. Aust Occup Ther J. 2006;53:196–204.

- Altman DG. Practical statistics for medical research. London: Chapman and Hall; 1991.

- Unnebrink K, Windeler J. Sensitivity analysis by worst and best case assessment: is it really sensitive? Ther Innov Regul Sci. 1999;33:835–839.

- Wilhelmson K, Eklund K. Positive effects on life satisfaction following health-promoting interventions for frail older adults: a randomized controlled study. Health Psychol. 2013;1:44–50.

- Ekström H, Ivanoff SD, Elmståhl S. Restriction in social participation and lower life satisfaction among fractured in pain: results from the population study” Good Aging in Skåne”. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2008;46:409–424.

- Gallagher M, Muldoon OT, Pettigrew J. An integrative review of social and occupational factors influencing health and wellbeing. Front Psychol. 2015;6:1281.

- Behm L, Wilhelmson K, Falk K, et al. Positive health outcomes following health-promoting and disease-preventive interventions for independent very old persons: Long-term results of the three-armed RCT Elderly Persons in the Risk Zone. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2014;58:376–383.

- Barenfeld E, Gustafsson S, Wallin L, et al. Understanding the black box of a health-promotion program: Keys to enable health among older persons aging in the context of migration. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being. 2015;10:1–10. DOI:10.3402/qhw.v10.29013

- Nilsson I, Häggström Lundevaller E, Fisher AG. The Reationship between Engagement in Leisure Activities and Self-Rated Health in Later Life. Act Adapt Aging. 2017;41:175–190.

- Arola LA, Mårtensson L, Häggblom Kronlöf G. Viewing oneself as a capable person – experiences of professionals working with older Finnish immigrants. Scand J Caring Sci. 2017;31:759–767.

- Socialstyrelsen. Folkhälsorapport 2009-126-71. [Public Health Report].Stockholm: Socialstyrelsen; 2009.

- Sedgwick P. The Hawthorne effect. BMJ. 2012;344:1–2. DOI:10.1136/bmj.d8262

- Brown T. Person-centred occupational practice: is it time for a change of terminology? Br J Occup Ther. 2013;76:207.