Abstract

Background: There exist few recovery and occupation-based interventions for mental health service users. Balancing Everyday Life (BEL) is a new occupation-based lifestyle intervention that was created to fill this need.

Aim: To gain group leaders’ and participants’ perspectives of the BEL intervention content and format, including factors that helped, hindered, and could be improved.

Methods: A constructivist grounded theory method guided data collection and analysis. Interviews took place with 12 BEL group leaders and 19 BEL participants from out-patient psychiatry settings and community-based day centers in Sweden.

Results: BEL’s structure and content were appreciated, yet flexibility was desired to adapt to participant needs. BEL could act as a bridge, helping participants connect with others, and to a more engaged and balanced everyday life. Facilitating factors included a person-focused (versus illness-focused) approach, physical and emotional environments, and connection. Barriers included room resources. More sessions were desired for the intervention.

Conclusion: Group leaders and participants experienced BEL as a useful tool to instigate meaningful change and connection in the participants’ lives. The combination of a positive person-focused approach and group support was appreciated. These results could inform future research, evaluation, and development of occupation-focused lifestyle interventions for mental health service users.

Introduction

Promoting healthy lifestyles and well-being for mental health service users, especially those living with severe mental illness, is an international concern [Citation1–4]. Developing health care interventions that support meaningful engagement, balance, and recovery toward mental health may be such a promotion [Citation5–8]. Majority of lifestyle interventions in the literature come from the nursing field and concern physical matters such as nutrition, weight management, smoking cessation and/or increasing physical activity, as these have been shown to be problematic health areas for people with mental illness [Citation9–12]. Although these are important lifestyle components, other research concludes that it is also warranted to create research-based lifestyle interventions for mental health service users that address occupational engagement, social connection, and balance [Citation8, Citation13, Citation14].

In order to create an opportunity for service users to address these aspects of life, the intervention Balancing Everyday Life (BEL) [Citation15] was developed. BEL is an occupational therapy intervention organized as a group-based course which focuses on different aspects of life and lifestyle. BEL draws inspiration from interventions promoting occupational engagement and balanced lifestyle patterns, namely ReDO for women with stress-related disorders [Citation16] and Lifestyle Redesign for the well elderly [Citation17, Citation18]. BEL has a similar structure to these interventions, but is designed for people receiving services from out-patient psychiatry or community-based social psychiatry. BEL’s content is based on research specifically addressing everyday life among mental health service users [Citation19–22] and incorporates factors to contribute to a more engaged and meaningful life and lifestyle. Differing from a traditional medical approach to lifestyle changes, such as prescriptions for healthy diet or exercise, BEL presents topics for discussion including occupational engagement, balance, social relationships, as well as healthy eating, exercise, and rest/sleep [Citation23]. In line with personal recovery [Citation24–27] and occupational therapy tenets, BEL aims to empower participants to set their own goals while taking into account their personal needs, interests, talents and opportunities.

In addition to the content and focus of lifestyle interventions for mental health service users, elements of the program’s format can act as barriers to, or incentives for, participating in lifestyle intervention programs. For example, motivational leadership in a group setting is a factor that has been valued by service users [Citation28], as is feeling on equal terms and connected to the staff [Citation29]. Group-based support is another factor that has been valued by both community mental health providers and service users [Citation10, Citation30]. Reported advantages of engaging in group-based lifestyle programs included getting to know one another, being with others who have mental health problems and understand, receiving support from peers, and having accountability to others when implementing lifestyle changes [Citation9, Citation10, Citation30]. An earlier study on BEL [Citation31] found that the group format was important for creating meaning through feeling connected through joining with others, feeling supported and understood through a sense of belonging, and feeling respected and worthy through re-valuing Self.

As BEL is a new intervention, and because few interventions designed for people with mental disorders have an occupational balance and personal recovery approach, an in-depth exploration of the experiences and perspectives of those involved appeared important. The aim of this grounded theory study was to gain group leaders’ and participants’ perspectives of the BEL intervention content and format, including factors that helped, hindered, and could be improved.

Methods

This study incorporated interviews conducted with BEL group leaders and participants. It was part of a larger research project using mixed methods aiming to evaluate the BEL intervention. The larger project included a randomized control trial [Citation15], and qualitative studies, including the current study. The earlier qualitative studies aimed at understanding BEL participant experiences of group participation [Citation31] and the process of making lifestyle changes [Unpublished observations]. They were conducted using a constructivist grounded theory approach, as proposed by Charmaz [Citation32, Citation33]. This method was seen as appropriate also for the current study as BEL was a new intervention and we were interested in exploring intervention-specific factors in relation to participating in, or leading the BEL intervention.

BEL Intervention

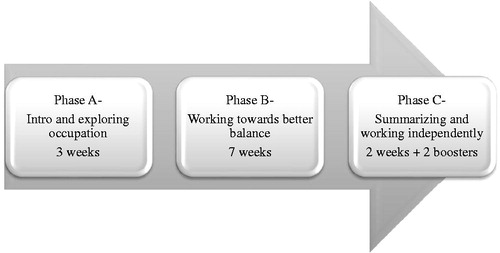

BEL was implemented in fourteen settings in Sweden. Eligible settings were out-patient psychiatry clinics or community-based activity centers in southern or western Sweden that had an occupational therapist with availability to attend the BEL training and be part of the larger research study. After attending the BEL group leader training, occupational therapists implemented the BEL intervention at their work setting, and most chose to have a co-leader who was another health professional. As is recommended in the BEL manual [Citation23], some occupational therapists had other staff members step in to support participant learning with certain subjects such as having a nutritionist talk about food, or a physical therapist talk about exercise. BEL is structured as a group-based, manualized course and will in this article be referred to interchangeably as an intervention and a course. The BEL group met weekly for three months, and then bi-monthly for two booster sessions. BEL was divided into three parts which can be seen in [Citation23]. Part A lasted three weeks and served as a general introduction and a time for the participants and leaders in the group to get acquainted. It included exploring one’s past and present occupational engagement, learning about occupational balance and imbalance, as well as meaning and purpose in life. Part B was the main section of the course which lasted seven weeks and focused on working towards a better balance in one’s life. Weekly topics included the art of rest and relaxation, mindfulness, nutrition, physical exercise, leisure activities, social life and relationships, and productivity. Part C focused on transitioning to working on one’s own, or with others, and was organized as two sessions plus two boosters. This was an opportunity for participants to reflect on progress made during the course, and to prioritize what they wanted to work on after the course end.

Data collection and analysis

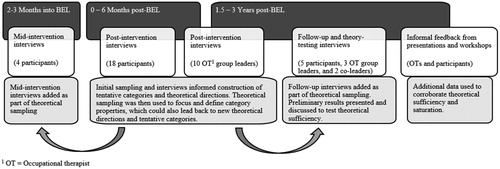

Data was collected through focus group discussions (FGDs) and individual/duo interviews with BEL group leaders, as well as individual interviews with BEL participants. summarizes the data collection process. As is recommended in grounded theory (Charmaz, 2014), analysis was an on-going process during the data collection period, which included initial and then focused coding, memo-writing, theoretical sampling, evolving interview questions, and theoretical assessing. During initial coding, the first author coded all the interview transcripts, starting with line-by-line coding for the three group leader FGD transcripts and first 12 participant interview transcripts, and memos were recorded. Analyst triangulation was used to enhance credibility [Citation34]; co-authors were involved throughout the analysis process, including reading, reviewing, and coding early interview transcripts, as well as challenging and giving feedback on emerging theory structure and the writing process. Focused coding and categorization involved grouping similar codes into categories and sub-categories, and continued throughout the analysis process until all interviews were coded and analyzed. In total, more than 1000 codes and memos were created. The categories and memos were used to build and test the emerging theory, which was an abductive process [Citation33]. As a tool to assist in storing data, coding, and organization, NVivo software v.11 [Citation35] was used.

BEL Group Leaders

A total of twelve group leaders were interviewed, which included ten occupational therapist group leaders from ten settings and two co-leaders. All occupational therapist group leaders who had completed at least one BEL group at the time of FGD data collection were invited to take part. Between 2014 and 2015, three FGDs took place with a total of nine BEL group leaders. The FGDs were comprised of two, four, and three occupational therapists, respectively, and took place in a room at the authors’ research institution. FGDs took between two and a half to three hours with breaks for coffee and lunch, which were provided. Late cancellations reduced the planned amount of group leaders interviewed in all three FGDs. A moderator (the second author) and an assistant led the FGDs, in accordance with Krueger and Casey [Citation36]. Grounded theory [Citation33] was used for the overall study design and analysis. Theoretical sampling [Citation33] included follow-up interviews in 2018 with three of the earlier-interviewed occupational therapists who were chosen as they were experienced group leaders having each led between four and nine BEL groups. Experiences of co-leading had been mentioned earlier in FGDs with occupational therapists. Therefore, based on theoretical sampling, two of these follow-up interviews also included their non-occupational therapist co-leaders. One individual interview was conducted with an additional occupational therapist who could not attend one of the FGDs. Interviews were conducted in a private room either at the group leaders’ place of work, the authors’ research institution, or a library. The staff focus of this study is on the occupational therapists, who had the main responsibility for BEL and also provided rich data. The non-occupational therapist co-leaders mainly corroborated their stories, and for this article, the term “group leaders” is used to denote both categories. Additional data used in this study included informal feedback sessions that the fourth and last authors had with group leaders regarding the manual and course content, as well as feedback from when the first author presented preliminary results from BEL to group leaders and participants involved in the project. Notes were taken and were used to validate, and if relevant, supplement the emerging categories.

BEL Participants

In addition to group leader interviews, 29 individual interviews were conducted with 19 participants who had taken the BEL course. The earlier-published qualitative studies can be referenced for more details, including participant demographics and recruitment process [Citation31]. Participants were adults (ages 26 – 69) receiving services from an out-patient psychiatric clinic and/or a community-based activity center. All were on full or partial sick leave, and could work up to 50% to be eligible for BEL. The occupational therapists interviewed potential BEL participants to assess if the intervention could be beneficial for them, and if the person was interested in joining a group-based intervention focused on finding a better balance in daily life. Participants should be of working age and not have substance abuse as their primary diagnosis. Most participants were at the post-acute stage, as assessed by the occupational therapist. Diagnoses included anxiety, depression, bi-polar spectrum, autism spectrum, schizophrenia/psychosis, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), post-traumatic stress, and personality disorders. For this qualitative study, BEL participants were approached by their group leader who asked if they were interested in being interviewed. Those who agreed were contacted by the researchers. Participants were interviewed zero to six months post-course. In addition, interviews took place mid-course with four participants (attrition of one at post-course), as well as seven follow-up and theory-testing interviews with five participants one and a half to three years post-course. The reasoning for conducting interviews at different points in time was to obtain information about the whole process of participating in BEL, including a retrospective and follow-up perspective, which came about from the theoretical sampling process. Interviews took between one half hour and two and half hours, and took place either at participants’ care setting or at their home, with the exception of two follow-up/theory testing interviews conducted via telephone and one at the authors’ research institution, per the participants’ requests.

Ethics

This study followed guidelines set out by the 1975 Helsinki Declaration (2008 revision) and was approved by the Regional Ethical Vetting Board in Lund (Reg. No. 2012/70). Group leaders and participants who took part in this study were given verbal and written information about the study, and signed consent forms. The interviews were audio-taped and transcribed, except for four follow up/theory testing interviews which were meant to validate the findings and the theory. These four interviews were based on participants reading the preliminary findings. Notes were taken on their feedback, which were used in the final edits and revisions. A gift certificate to a florist or movie theater was given to the BEL participants.

Results

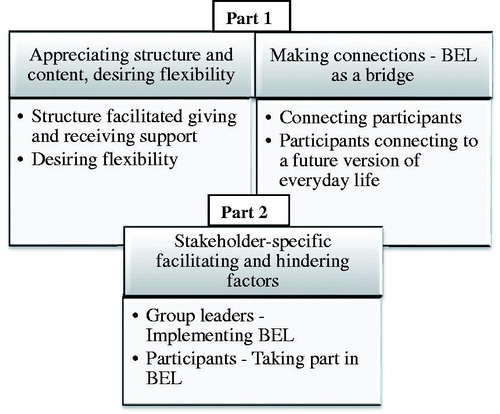

The results are separated into two main parts. Part 1 focuses on the perspectives of the occupational therapists and participants in regards to the content and format of BEL. For the most part, occupational therapists and participants reported similar experiences with the intervention. The results in Part 1 are thus organized with group leader and participants’ common experiences presented together, whereas unique or differing perspectives are indicated separately. Part 2 focuses on facilitating and hindering factors as experienced by the two identified categories of stakeholders for this study, i.e. occupational therapists leading BEL and participants taking part in the intervention. The categories are here separated to indicate the different perspectives. A description and relationship of the core and sub-categories derived from the interview data can be seen in .

Part 1: Perspectives of the BEL intervention content and format

Overall, the content and format of the BEL intervention was experienced as very positive by the group leaders and participants. Occupational therapists felt that BEL was a needed contribution in out-patient and social psychiatry. Both parties pointed out that the different subjects touched upon important life areas that allowed the participants to learn from the prepared material and to set and make progress towards personal goals.

Appreciating structure and content, desiring flexibility

Group leaders and participants appreciated the manualized course format and structure of the BEL intervention. At the same time, they desired flexibility in order to meet varying needs of the participants.

Structure facilitated giving and receiving support

The content and clear structure of BEL, as well as how the topics built upon each other through the course, were experienced as positive by group leaders and participants. Some participants were initially apprehensive of it being organized as a course as they feared they would not be able to keep up or “complete the course satisfactorily.” Reassurance and further explanation from the group leaders was important for these participants to join, and in the end many participants reported feeling proud or satisfied that they had completed BEL. Having a manual/binder was appreciated as it organized the lessons, exercises and personal goal setting through the course. The binder could also be referred to later as a refresher, or when working individually with the health care team. Some participants experienced it difficult to organize the papers before entering them into the binder. One participant commented, “I think it’s a little hard. Because what is easy for many, is not easy for us, or for people who have mental problems,/…/the small things are actually the hardest.” Group leader and peer support was appreciated in these cases, especially when participants could joke with one another and realize they were not alone.

BEL’s organization with different phases (see ) was reported as positive. It served to introduce the topics and for participants to get an overview of their daily life, set goals, work together, and eventually make plans for how to continue to work on goals and connect with others after the course. Reflecting on what had been done during the course, comparing assessments before and after the course, and focusing on what to continue working on, how, and with whom was also seen as positive. Booster sessions were appreciated as they spaced out the end, and made for a gentler transition. Both the group leaders and the participants described BEL as a “valuable tool” which supported learning and progress, and stressed the importance of learning how to set manageable goals. One participant said:

I’ve gotten the tools for how I will work [on my goals]. That is probably the biggest difference …I have dared to be able to speak in a group and broken down all of these goals that are part of a day, or daily life… because it is easier to see the smaller pieces than to see everything, and to grasp it all…/But this course, I feel that I have gotten so unbelievably much and I am really happy that I took it.

Some group leaders reflected that after leading BEL groups they wanted to encourage other professionals at their work setting to focus on more manageable goals with clients as well.

BEL’s topics and approach, described by the group leaders as “occupation-based,” “recovery-oriented,” or “focused on daily life” was appreciated as they reported there are few manualized interventions geared toward psychiatric or community services, and the ones that exist often have a medical or illness focus. One group leader said she felt that with BEL it became quite clear for the participants “that the focus is on me and my situation, apart from my illness… The role as a person…different activities one is in…it is an occupational perspective in a whole different way that has been very good, I think, for the patients.” Participants often mentioned the BEL approach as being “different” and “positive” and appreciated the focus on their abilities and goals versus not feeling well.

Group leaders and participants felt that the topics were important, and the focus on the different life domains as well as the daily life tasks could open discussions that were refreshing for participants to learn they were not alone. Specific exercises were mentioned that helped participants to gain an overview of how their daily life was organized. For some it was the first time they had realized that they spent most days alone, at home, and not engaged in many activities, whereas others realized that they were constantly “on the go” from one place or activity to another, with little time for rest or recuperation. Exercises could also help participants realize resources they had in their lives that they could access. Getting an overview of one’s nutrition needs and low-cost, healthy recipes in the course materials were also appreciated. The topics of social relationships and productivity were often mentioned as sensitive topics that ultimately held the greatest personal meaning when participants were able to challenge long-term fears, attain personal goals, set boundaries, expand their social network or gain a more positive perspective on what they do. However, one participant who was positive to the intervention as a whole reacted when it was suggested that participants interested in a return-to-work program contact their occupational therapist. He felt this was provoking and said, “If you don’t have the ability it doesn’t matter how much desire you have… Of course I don’t go around thinking about work, if I can’t manage daily life.”

The course manual encouraged a group outing for the last session, which group leaders and participants reported as one of the highlights of the course. They shared stories of going to a theater, going for a picnic in a botanical garden, and going to a local café. Participants appreciated the group leader organizing the activity and being with them.

Desiring flexibility

Most of the group leaders and participants desired more flexibility in different aspects of the BEL intervention. For instance, some felt that examples or exercises given in the presentation or manual were referring to people who were “low functioning” such as an exercise on how to read facial expressions. Others thought that the level of information was good, and group leader support was appreciated to help them understand the material. Some participants wanted a more basic level of information on certain topics, such as diet and nutrition, while others wanted more advanced. Group leaders felt that more abstract exercises could be difficult for some clients, and desired more concrete options as well. As BEL was part of an RCT study, occupational therapists had been asked to follow the manual and PowerPoint presentations in order to support fidelity to the intervention and validity in the research findings. Both the group leaders and the participants felt that the course could have been better if the group leaders had the freedom to adapt. One participant explained, “I thought it was way too basic…as if they had too low expectations on what we could do actually.”

Related to flexibility, most group leaders and participants desired more time for the course length, though some felt that it was just right. The schedule of having a new topic each week was described as “tight” and “intensive” and participants wanted more time to reflect and “talk freely.” Both groups suggested different solutions such as a flexible timeline, more meetings for each subject, and additional booster sessions for continued social connectedness. One participant suggested, “instead of having the whole life in…three months, maybe you could take part of the life in six months.” Another participant said that she wanted “more time for it…I would have gladly gone eight months.” However, the comments from the occupational therapists were often that it would be hard to recruit group participants for such a long course. Interestingly, later in the research and interviewing process the intensity of the course length was no longer reported as a problem, and most participants said that they thought the intervention was the right length.

Making connections - BEL as a bridge

When group leaders and participants described the significance of BEL, it often related to participants connecting to others, or oneself, in new, different or improved ways. Some participants had not attended groups at the center before, but chose to join other groups after BEL. Other participants realized, through BEL, how much time they spent at the care center and became inspired to find activities outside the center and connect with other societal contexts.

Connecting participants

Group leaders and participants reported that BEL’s closed group structure was positive as they could get to know each other through the course, which contributed to deeper connections compared with open or drop-in groups where they sometimes did not discuss with others, or even introduce themselves. The group environment with understanding peers supported participants to share personal information with the others and break old patterns of shame by telling the group things they had never shared with the health professionals before. Group leaders were included in this connection, and participants often mentioned the value of feeling like friends, or being on an “equal standing,” with the group leaders. Increasing one’s social contacts, and developing friendships was often described as a highlight of BEL. Some participants continued to meet on their own after the course end; however, organizing social meetings after the course was not always successful and participants could find it stressful to organize on their own. One group leader reflected:

[The participants] had maybe met a few times sitting in the waiting room or at the coffee table, but not otherwise. So it was a little exciting how they could receive and give to each other. When we ended the group, everyone said they wanted to continue but they all said they couldn’t continue if there wasn’t a leader there. We had tried to organize it so that they could be in the [care setting] in a room, but it didn’t happen.

Participants connecting to a future version of everyday life

Group leaders and participants shared stories of participants breaking old patterns in regards to their daily occupations and balance, taking a more active approach to self-care, and setting goals. BEL could connect participants to future engagement in meaningful occupations which could include volunteer work, creative activities, becoming more involved in their care center, or returning to work or studies. Many settings offered other groups such as gardening, creativity, or general occupation support groups. This was appreciated by participants who wanted to continue with something after BEL. Group leaders reported that they were pleasantly surprised with progress participants made, but both parties noted that change takes time and therapist-participant follow-up after the intervention was important.

Part 2: Stakeholder-specific facilitating and hindering factors

Participants and group leaders told about facilitating and hindering factors with their involvement in the BEL intervention. Some of those factors are incorporated in Part 1 above, as experiences or perceptions that were shared by group leaders and participants. This section focuses on the experiences that were specific to group leaders implementing BEL, as well as participants taking the BEL course. summarizes the facilitating and hindering factors.

Table 1. Facilitating and hindering factors for group leaders implementing BEL and participants taking part in BEL.

Group leaders - Implementing BEL

Facilitating factors

Group leaders appreciated the BEL training which included the assessments that are utilized in the intervention and the related research. They described the need for research-based interventions in their work settings as there was pressure to show evidence-based practice. In this way, BEL was appreciated as it linked the research on occupation, mental health, and well-being with a clinical intervention, even if the intervention itself was in process of being evaluated. All occupational therapists interviewed felt that implementing BEL in their work setting was welcomed by their co-workers and complemented existing programs offered at their work-place. Most had a co-leader and were positive to having another professional to share the leading experience with. Some occupational therapists felt that BEL helped to clarify their role in the care team, or to strengthen their relationship with co-workers who were engaged in BEL. As mentioned earlier, occupational therapists appreciated the occupation-focused manual and topics and many expressed that they had been waiting for such a manual. BEL participants sharing their positive experiences with others was a facilitator and some group leaders reported having a wait list for up-coming BEL groups as staff, clients, and even some Social Insurance agents had heard good reports and then recommended it for others who they felt needed support.

Hindering factors

The main implementation barrier that occupational therapists reported was that in some facilities, there were limited or no group rooms available, or they lacked a projector for the PowerPoint presentations. Examples of such facilities were community-based activity centers that lacked a large group room, or a busy psychiatry out-patient unit in which care professionals needed to “compete” for the larger room bookings. Therapists described the perfect scenario as having a suitable group room with another private room near-by in case a participant needed individual support during a group session. Another hindering factor described by the therapists was recruiting participants as some clients disliked groups, and others were hesitant to join.

Participants - Taking part in BEL

Facilitating factors

Group dynamics were generally reported as a facilitator for participants to feel supported in working towards goals and personal change. In general, group factors that encouraged feeling part-of and connected, such as the closed group structure and peer support mentioned earlier, were important facilitators. Supportive, competent group leaders were valued for holding the structure and promoting security in the group, but also for listening and sharing so that participants felt connected with them as a part of the group. Feeling safe in a group setting was especially appreciated by those who struggled with fears of opening up to others or of being treated poorly. Group leaders sharing their own life experiences was appreciated by participants as they realized that even the group leaders struggle with daily life and family domains, and it created an atmosphere of feeling on equal terms. One participant said that the atmosphere in the group was open and supportive, and as they got to know one another, it was as if “the dead began to talk.” He continued about the group leaders: “They gave us room and didn’t steer too much…We (participants) took responsibility for ourselves, but it had a lot to do with the staff too, they were the best, just suited for it… unbelievably patient, didn’t interrupt, and noticed things.”

From the participants’ comments about group diversity, including having a mix of genders, personalities, ages, diagnoses, working status, etc., the most important facilitating factor for engagement was having similar functioning levels in the group as well as similar goals/problems. This then led to participants feeling they could better relate to and help one another. When the term “level” was used it often referred to how well, or unwell, someone was feeling which then affected the types of goals they were working on. One participant explained that she appreciated that her group was high functioning, “we were at about the same level, all of us. We could understand each other well.”

Hindering factors

Having differences in functioning levels of group members could be reported as a barrier if participants felt it affected the group cohesiveness. One participant felt negatively affected when some group members were struggling or non-communicative in the group interactions: “…everyone was on so many different levels/…/I could feel almost ashamed sometimes that some things had gone so well for me and had gone so terribly wrong for another person who still feels so bad.” A related hindering factor was feeling that the group members were in a different phase in their life than oneself. For example, if most of the group was trying to increase activities while being on full-time sick leave, another participant who had too much to do or had recently started working could feel that they did not identify with the group. Status of sick-leave (temporary or permanent) could also be a factor that participants compared themselves to the others, feeling negatively about oneself if they felt they were “worse off”.

Additional hindering factors reported by participants included fears or previous negative experiences that could limit one’s willingness to “dare” to try something new. Fears included joining a group, speaking in a group, and opening oneself to others. Negative experiences with previous groups in health care, or health care professionals that were condescending or did not listen could add to these fears. Struggling with health and symptoms in general could be a factor that hindered having energy to make changes, as well as to participate in the course. Many participants described the importance of “being in the right place” in one’s life and personal recovery, and that they could not have benefitted as much from BEL when they were more acutely ill. Some participants expressed the wish to go through BEL again as they felt they were in a better place after completing the intervention. Not having enough time in day-to-day life to devote to the course and work on one’s goals was another barrier reported. Examples of situations that competed with time and energy for the course included recently starting a new job, family demands, or recovering from a burn-out depression and having many responsibilities already.

Discussion

This study illuminated that both occupational therapy group leaders and participants overall were positive to the intervention. BEL seemed to offer a tool that occupational therapists could easily implement in their work with clients, and could strengthen their professional role. Most participants interviewed reported that BEL made a lasting difference in their daily lives. These results support findings from a previous RCT study which showed that BEL participants had significantly increased levels of functioning as well as activity engagement [Citation15]. This qualitative study adds insight into what aspects of the intervention were perceived as beneficial, and not.

Desiring flexibility

An interesting finding was the contrast between appreciating the structure and content of BEL, yet desiring flexibility. Therapists reported following the manual as they had been directed to do so as being part of the RCT. However, extended flexibility in exercises, references, examples, and course content was desired as there was a wide range of functioning levels, occupational needs, and diagnoses of BEL participants. Others described incorporating more flexibility with groups run after the study concluded. This brings up the challenge of having guidelines for those implementing an intervention to follow it as presented. There appeared to be a need for flexibility in order to meet varying needs of the participants, which at times could conflict with following the intervention and manual exactly as presented. It is possible that some built-in flexibility could benefit the group leaders, participants, as well as the outcome of the intervention. This has been taken into consideration in a revised version of the BEL manual [Citation37].

Time

Many group leaders and participants desired more time for the intervention. This could be further researched as it seems that many other programs inspired by the Well Elderly studies are three to four months long [Citation16, Citation38, Citation39]. However, the original Well Elderly study was nine months long [Citation17], and the Well Elderly Study II was six months long [Citation18]. BEL was initially planned to be longer than four months, but both service users in a feedback panel and occupational therapists working in the mental health field argued that the time should be shorter as it is hard to recruit participants for longer interventions. It seems warranted to further research this topic. It is interesting that most participants said that BEL should be longer, but none suggested less subjects to better fit the time. Instead, participants desired more time to address the lifestyle changes they wanted to make, and to have continued support from the group. After the RCT, the BEL intervention and manual were updated by the authors based on feedback from the occupational therapists and participants. Since both parties preferred a lengthened course period, three sessions were added to part B (see ), extending the course duration from 12 weeks to 15 weeks [Citation37]. This allowed more time for the social life and sleep/rest subjects, and added a catch-up session at the end in which participants could address any goals or subjects they needed more support with.

Another aspect of time was when participants felt they had too many responsibilities in their daily lives to devote time to working on goals or course work. It is possible that these participants could feel less connected to the others who were trying to fill their time with new activities, social opportunities, or working together on goals. These findings suggest that it could be important for group leaders to be aware if participants are struggling with lack of time in their daily life so that they can be supported by setting appropriate goals that are not too time-intensive, and perhaps related to prioritizing or removing unnecessary tasks instead of adding more.

Environment

The physical and emotional environment played an important role for both groups. For group leaders, having the needed resources such as a group room with a projector was important, and yet not always available. This could cause extra time for planning BEL, sometimes even needing to rent a room outside the facility. Related to the physical environment, many participants reported going outside the facility together with the group leaders and members for the last sessions was a highlight of the course. Local trips to see a theater, eat in a café, or have a picnic in a botanical garden were highly prized experiences. This suggests that mental health practitioners could benefit their clients by incorporating opportunities for group-based outdoor activities. It is also possible that these experiences were memorable as the last session was a celebration and reflection over the time that the group had worked together to support each other towards meaningful change. In addition to the physical environment, the emotional environment was also very important as many participants reported generally being afraid of being in a group, but “felt safe” in the BEL group. This seemed to be an important component for participants, especially when trust issues or fears prevented such connection before. Group leaders were an important part of this, which supports other research on the importance of positive interactions and relationship-building with group leaders [Citation28, Citation29, Citation40, Citation41]. For example, Forsberg and Lindqvist [Citation29] found that one of the meanings experienced by mental health service users participating in a lifestyle intervention was feeling closer and more equal to the staff, as they socialized in the group and learned more about the staff including shared interests. Similar comments were made by BEL participants in this study as well as a previously-published study on meaning-making through BEL group participation [Citation31]. BEL participants found meaning in feeling listened to and believed, and reported they felt on more equal terms or as friends with the group leaders. In the current study, group leaders mentioned using examples from their lives regarding struggles to find balance, and participants appreciated their candor and learning that the group leaders also had struggles. These findings emphasize the importance of therapeutic use of self, which has also been discussed in the occupational therapy literature [Citation42].

Implementation

Occupational therapists and co-leaders reported few barriers in implementing BEL in their work places. This is likely because there was little or no additional cost, other than therapists’ work hours and time away for the training. Occupational therapists appreciated being able to see multiple patients at once and felt they could be more effective not only from a time perspective, but also as participants helped one another in a way that just the therapist could not. Although the aim of this study was not an implementation study per se, the results touched upon certain aspects. Acceptability, for example, can be defined as “the perception among implementation stakeholders that a given treatment … or innovation is agreeable, palatable, or satisfactory” [Citation43, p.67]. BEL’s acceptability was regarded as positive from the group leaders and participants. It fit well into the work occupational therapists were already doing, and having a set structure, topics and manual helped reduce the amount of preparation time required. In general, occupational therapists reported that co-workers were positive, and even eager, to co-lead the BEL groups. However, as mentioned earlier, resources for a group room in some settings were lacking, and there was a desire for flexibility in the structure and content.

Methodological discussion

Using a constructivist grounded theory approach [Citation33] with emphasis on an emergent research design supported the over-all aim to better understand group leaders’ and participants’ perceptions of the BEL intervention. Charmaz suggests that researchers and participants mutually construct meaning during collection and analysis of data. Theoretical sampling was an important part of this process, and the addition of mid-course and follow-up interviews strengthened the results through further development of categories’ properties through conversations with the participants and group leaders. Although the categories in Part 1 of the results were more theoretical in nature, Part 2 was kept more descriptive in order to stay true to the data as presented by the group leaders and participants regarding facilitating and hindering factors related to the BEL intervention. Charmaz [Citation33] describes that it is important to pay attention to what participants are saying when pursuing theory, and the authors felt that the more detailed data of Part 2 complemented the more theoretical nature of Part 1, and that both could be clinically applicable. Regarding the FGDs with the group leaders, interview groups were smaller than planned due to late cancellations related to transportation issues, weather, health, and work demands. However, this was not felt to affect the results as smaller groups meant that each therapist had more time to share their experiences. Limitations to the study could be lack of diversity in the participant groups as Swedish was required for group participation. It could be suggested that the BEL intervention and further research be developed for vulnerable populations who do not speak Swedish.

Conclusion

The results from this study add to the limited literature on occupation-based lifestyle interventions for people with mental disorders. In general, group leaders and participants appreciated the structure and content of BEL, while desiring more flexibility in regards to content level and the amount of time for the intervention. BEL could be seen as a bridge as connections were made between participants as they supported each other to make meaningful life changes as well as to become more connected in societal contexts. BEL supported participants in connecting to a future version of daily life which could include finding a personalized approach to balance in life, as well as their level of occupational engagement. Facilitating and hindering factors were explored from both group leaders implementing BEL and participants taking part in BEL. Facilitators included BEL’s person-focused (versus illness) approach, physical and emotional environments, and connection with others. Barriers included room resources, and if participants did not feel connected with the other group members. In general, more group sessions were desired. These results could serve to help other professionals who in the future may develop or evaluate interventions for mental health service users.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Cabassa LJ, Ezell JM, Lewis-Fernández R. Lifestyle interventions for adults with serious mental illness: a systematic literature review. Psychiatr Serv. 2010;61:774–782.

- National Board of Health and Welfare. Nationell utvärdering 2013 vård och insatser vid depression, ångest och schizofreni: Rekommendationer, bedömningar och sammanfattning. [2013 National evaluation of efforts and care for depression, anxiety and schizophrenia: recommendations, assessments and summary]. Stockholm: National Board of Health and Welfare; 2013.

- Parks J, Svendsen D, Singer P, et al. Morbidity and mortality in people with serious mental illness. Alexandria, VA: National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors (NASMHPD) Medical Directors Council; 2006.

- World-Health-Organization. The European mental health action plan. Çeşme Izmir, Turkey: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2013.

- Eklund M, Argentzell E. Perception of occupational balance by people with mental illness: a new methodology. Scand J Occup Ther. 2016;12:1–10.

- Krupa T, Fossey E, Anthony WA, et al. Doing daily life: how occupational therapy can inform psychiatric rehabilitation practice. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2009;32:155–161.

- Leufstadius C, Eklund M, Erlandsson LK. Meaningfulness in work – experiences among employed individuals with persistent mental illness. Work. 2009;34:21–32.

- Edgelow M, Krupa T. Randomized controlled pilot study of an occupational time-use intervention for people with serious mental illness. Am J Occup Ther. 2011;65:267–276.

- Butterly R, Adams D, Brown A, et al. Client perceptions of the MUSCSEL project: a community-based physical activity programme for patients with mental health problems. J Public Ment Health. 2006;5:45–52.

- Roberts SH, Bailey JE. Incentives and barriers to lifestyle interventions for people with severe mental illness: a narrative synthesis of quantitative, qualitative and mixed methods studies. J Adv Nurs. 2011;67:690–708.

- Lambert RA, Harvey I, Poland F. A pragmatic unblinded randomised controlled trial and economic evaluation of an occupational therapy-led lifestyle approach and routine GP care of the treatment of Panic Disorder presenting in primary care. J Affect Disord. 2007;9:63–71.

- Olfson M, Gerhard T, Huang C, et al. Premature mortality among adults with schizophrenia in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:1172–1181.

- Eklund M, Erlandsson L-K, Leufstadius C. Time use in relation to valued and satisfying occupations among people with persistent mental illness: exploring occupational balance. J Occup Sci. 2010;17:231–238.

- Eklund M, Leufstadius C, Bejerholm U. Time use among people with psychiatric disabilities: implications for practice. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2009;32:177–191.

- Eklund M, Tjörnstrand C, Sandlund M, et al. Effectiveness of Balancing Everyday Life (BEL) versus standard occupational therapy for activity engagement and functioning among people with mental illness–a cluster RCT study. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17:363.

- Eklund M, Erlandsson L-K. Return to work outcomes of the Redesigning Daily Occupations (ReDO) program for women with stress-related disorders – a comparative study. Women Health. 2011;51:676–692.

- Clark F, Azen SP, Zemke R, et al. Occupational therapy for independent-living older adults. A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1997;278:1321–1326.

- Clark F, Jackson J, Carlson M, et al. Effectiveness of a lifestyle intervention in promoting the well-being of independently living older people: results of the Well Elderly 2 Randomised Controlled Trial. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2012;66:782–790.

- Bejerholm U, Eklund M. Time-use and occupational performance among persons with schizophrenia. Occup Ther Ment Health. 2004;20:27–47.

- Leufstadius C, Erlandsson LK, Eklund M. Time use and daily activities in people with persistent mental illness. Occup Ther Int. 2006;13:123–141.

- Argentzell E, Håkansson C, Eklund M. Experience of meaning in everyday occupations among unemployed people with severe mental illness. Scand J Occup Ther. 2012;19:49–58.

- Bejerholm U. Relationships between occupational engagement and status of and satisfaction with sociodemographic factors in a group of people with schizophrenia. Scand J Occup Ther. 2010;17:244–254.

- Argentzell E, Eklund M. Vardag i Balans. En manual för kursledare. [Balancing Everyday Life. A manual for course leaders]. Lund (Sweden): Lund University; 2012. Swedish.

- Anthony W. Recovery from mental illness: the guiding vision of the mental health service system in the 1990s. Psychosoc Rehabil J. 1993;16:11–23.

- Davidson L, Shahar G, Stayner DA, et al. Supported socialization for people with psychiatric disabilities: lessons from a randomized controlled trial. J Community Psychol. 2004;32:453–477.

- Le Boutillier C, Leamy M, Bird VJ, et al. What does recovery mean in practice? A qualitative analysis of international recovery-oriented practice guidance. Psychiatr Serv. 2011;62:1470–1476.

- Slade M. Mental illness and well-being: the central importance of positive psychology and recovery approaches. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:26.

- McDevitt J, Snyder M, Miller A, et al. Perceptions of barriers and benefits to physical activity among outpatients in psychiatric rehabilitation. J Nursing Scholarsh. 2006;38:50–55.

- Forsberg KA, Lindqvist O, Bjorkman TN, et al. Meanings of participating in a lifestyle programme for persons with psychiatric disabilities. Scand J Caring Sci. 2011;25:357–364.

- Yarborough BJ, Stumbo SP, Yarborough MT, et al. Improving lifestyle interventions for people with serious mental illnesses: qualitative results from the STRIDE study. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2016;39:33–41.

- Lund K, Argentzell E, Leufstadius C, et al. Joining, belonging, and re-valuing: a process of meaning-making through group participation in a mental health lifestyle intervention. Scand J Occup Ther. 2017:1–13.

- Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory: a practical guide through qualitative analysis. 1st ed. London (UK): Sage; 2006.

- Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory. 2nd ed. London (UK): Sage; 2014.

- Patton MQ. Qualitative research and evaluation methods. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage; 2015.

- NVivo. [Computer software, v. 11]: QSR International; 2015 [cited 2018 Oct 22]. Available from: https://www.qsrinternational.com

- Krueger R, Casey M. Focus groups: a practical guide to applied science. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage; 2009.

- Argentzell E, Eklund M. Vardag i Balans. En manual för kursledare. 2:a uppl. [Balancing Everyday Life. A manual for course leaders. 2nd ed.]. Lund (Sweden): Lund University; 2017. Swedish.

- Mountain G, Windle G, Hind D, et al. A preventative lifestyle intervention for older adults (lifestyle matters): a randomised controlled trial. Age ageing. 2017;46:627–634.

- Johansson A, Björklund A. The impact of occupational therapy and lifestyle interventions on older persons’ health, well-being, and occupational adaptation: a mixed-design study. Scand J Occup Ther. 2016;23:207–219.

- Roberts SH, Bailey JE. An ethnographic study of the incentives and barriers to lifestyle interventions for people with severe mental illness. J Adv Nursing. 2013;69:2514–2524.

- Molin J, Graneheim UH, Lindgren B-M. Quality of interactions influences everyday life in psychiatric inpatient care—patients’ perspectives. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being. 2016;11:29897.

- Taylor RR, Lee SW, Kielhofner G, et al. Therapeutic use of self: a nationwide survey of practitioners' attitudes and experiences. Am J Occup Ther. 2009;63:198–207.

- Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, et al. Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2011;38:65–76.