Abstract

Background: Integration of research-based knowledge in health care is challenging. Occupational therapists (OTs) need to implement new research-based interventions in clinical practice. Therefore it is crucial to recognize and understand the factors of specific barriers and facilitators affecting the implementation process.

Aim: To identify the key factors important for OTs during the implementation process of a complex intervention.

Materials and methods: A cross-sectional study with a combination of qualitative and quantitative data in a mixed method design. Forty-one OTs and 23 managers from three county councils in Sweden, responded to a questionnaire one year after the OTs participation in a workshop to prepare for implementation of a client-centered activity of daily living intervention for persons with stroke.

Results: Over 70% of the OTs benefitted from reading and discussing articles in the workshop; 60% had faith in the intervention; 69% reported usability of the intervention. High level of support from managers was reported, but less from team members. The therapists’ interaction, perceptions of own efforts and contextual influence affected the implementation process.

Conclusion: The workshop context with facilitation and access to evidence, supportive organizations and teams, sufficient interaction with researchers and satisfying self-image were successful key factors when involved in research.

Introduction

There is an ongoing discussion concerning the importance of anchoring research in healthcare services by creating dialogs and collaborations between researchers and clinicians [Citation1]. However, there is a gap between the research-based knowledge and the healthcare services available for clients [Citation1]. To reduce the gap, it is important to involve clinicians in research processes with account to their experiences and attitudes and to allocate time for reflection and knowledge translation [Citation2,Citation3]. The present study involved occupational therapist (OTs) and the aim was to identify the key factors important for the OTs in the implementation process of a complex intervention.

Developing a new intervention is a multifaceted process and the numerous parts involved increase the complexity further when the complex intervention is to be implemented in health care. Occupational therapy interventions as well as other interventions in healthcare are complex and can be characterized by; ‘the number of interacting components; the number and difficulty of behaviors required by those delivering or receiving the intervention; the number of groups or organizational levels targeted by the intervention; the number and variability of outcomes; and the degree of flexibility or if tailoring of the intervention permitted’ (pp 588) [Citation4]. The development may involve processes of evaluation, which may not be linear over time, but have a goal of improving the quality of the intervention [Citation5]. However, various factors can affect the clinicians who implement a new intervention, including the use of knowledge, how they respond and interact during the implementation process, and their relationship to the context in which the implementation is to take place [Citation6]. OTs are one group of clinicians working in the healthcare sector who also need to integrate new research-based interventions in clinical practice. To answer the questions about the various factors affecting research utilization, it is important to have knowledge, and an understanding, of the clinicians’ approaches to the implementation process. In this study, the Ots’ motivation, knowledge use [Citation7] and attitudes to translating research-based knowledge and interventions into practice [Citation8] will be explored.

A variety of frameworks is available to structure and guide the complex processes involved in, and the implementation of a new intervention. One framework, which describes three basic factors important for changing and implementing new knowledge in practice is Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services (PARIHS). These factors are evidence (includes research-based knowledge, knowledge from clinical experience including professional practical knowledge, patient preferences, and experiences), context (resources, values and leadership style), and facilitator (a person who support the implementation process by being a mentor and coach) [Citation9,Citation10]. This change could involve implementation of guidelines, research-based knowledge, etc. where the framework provides an opportunity to evaluate how these factors contribute to or prevent the actual implementation [Citation11–15]. The 2008 PARIHS version was used in the present study, but the framework has recently been revised to i-PARIHS, where the ‘i’ stands for integrated. Harvey and Kitson [Citation8] also replaced the factor evidence with innovation and recipients, arguing that evidence must be generated from practice [Citation16]. Furthermore, they believed that the research-based knowledge cannot be implemented in its original form such as clinical guidelines. The authors stressed the importance of being innovative and adapting evidence to the specific situation.

The National Implementation Research Networks’ [Citation17] define implementation as ‘a specified set of activities designed to put into practice an activity or program of known dimensions’. In the present study the activity was client-centered activities in daily living (ADL) intervention (CADL) [Citation18,Citation19]. Consideration must be given to two different sets of activities when studying the implementation process; an intervention-level activity (design, participants, dropouts) and an implementation-level activity (practitioners’ attitude and precondition, training time, recourses). Consequently, these activities provide different outcomes [Citation17]. This study will focus on the outcome of the implementation-level activity based on OTs experiences such as the conditions for participation, the use of an intervention and their own performance [Citation20,Citation21] while being involved in a Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT). A study by Rycroft and colleagues [Citation22] identified the importance of including the clinicians as part of the PARIHS framework. They emphasized that the clinicians’ role, attitudes to research, and behavior affected the degree of implementation success. At the micro-level, which means the individual level, the act of creating conditions is needed to eliminate the anxiety and uncertainty in the individuals to change behavior or deal with a new method. The person's character, abilities, motivation, position in the organization, knowledge, and beliefs about the intervention are individual factors that may affect the implementation process [Citation20,Citation21]. Numerous studies describe that communication and interaction, such as working with workshops, lectures, creating room for follow-up discussions with colleagues, networking, writing scientific articles as well as interaction with the researcher, have generated increased research-based knowledge [Citation16]. Furthermore, reading scientific articles/literature has emphasized the interest of research-based knowledge and has had an impact on daily practice for health professionals [Citation16,Citation23,Citation24].

The present study is part of a larger project called Life After Stroke II, during which the OTs participated in a workshop which aimed at providing the knowledge needed to deliver the CADL [Citation18,Citation19]. The overarching goal of the developed CADL was to enable agency in daily activities and participation in everyday life for persons with stroke. An occupational and phenomenological perspective was applied by using the client’s lived experiences as the point of departure for the CADL intervention [Citation7,Citation25–28]. The CADL intervention comprised different components and strategies in which the OT’s role initially was to create a relationship with the client to collaborate regarding how the training was to be designed in activities that were important for the client to perform. Using a problem-solving strategy, the clients had the opportunity to collaborate with an occupational therapist (OT) on designing goals using the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM) [Citation29], planning training, evaluating, and formulating new goals. Many factors could influence the results of an intervention, posing challenges regarding the extent to which the outcomes of the implementation will be successful or not. This study intends to investigate the key factors important to the OTs in the implementation process of a new complex intervention. The research questions of this study are: What factors contributed to the implementation process of the new intervention for the OTs? What barriers and facilitators could be identified? What type of sustainable change emerged over time resulting from the experiences of the process of integration and use of knowledge?

Methods

Design

A cross-sectional study was conducted using a mixed method with convergent parallel design in which qualitative and quantitative data complement each other to enable a deeper understanding and knowledge of the results. Analysis of both types of data enabled integration and interpretation of the experiences from different points of view [Citation30,Citation31].

Participants

The sample consisted of two groups; 41 OTs that delivered the CADL intervention and their 23 managers from three different county councils in the eastern part of Sweden. The OTs were asked to participate in the project by their manager. They either worked in in-patient geriatric rehabilitation, in-patient medical rehabilitation or in home-based rehabilitation units and had experience of rehabilitation (2–39 years) of patients with stroke (see ). This study concerns the OT’s long-term perspective of their experiences. In the present study, all the OTs that had delivered the CADL were approached by a postal letter and asked to participate and respond to the questionnaire regarding their experiences of participating in the workshop and in the RCT.

Table 1. Participant characteristics (n = 31).

Settings

Before using the CADL intervention within the RCT, the OTs participated in a five-day workshop (five full days spread over one month) arranged by the researchers who were responsible for the project. The overarching goal of the workshops was to give the OTs knowledge and tools to enable agency in daily activities and participation in everyday life among people with stroke. Further the workshop aimed at supporting their knowledge acquisition concerning implementation of complex interventions. Therefore the workshop included lectures by experienced researchers on the theories and concepts underlying the research base for the new intervention. The OTs read articles and had time to practice and discuss the new intervention based on various case studies. After completion of the workshop, the OT’s included and implemented the CADL at their ordinary workplaces as a part of the RCT where the CADL intervention was compared to a usual ADL intervention (control group) during 2009–2011 [Citation18,Citation19,Citation32]. The researchers conducted monthly follow-ups face to face, by phone or email with the OTs to ensure that they performed the components that the CADL intervention comprised and further the provided information on how the study proceeded in a monthly newsletter.

Data collection

The researchers responsible for the RCT designed a questionnaire in line with the PARIHS framework [Citation10] summarized in . The questions were closed-ended and open-ended, divided in themes (1) the role as an OT, (2) conditions at the workplace, (3) the CADL intervention, and (4) how do you work today?

Table 2. Summary and response rate of the questions in the questionnaire.

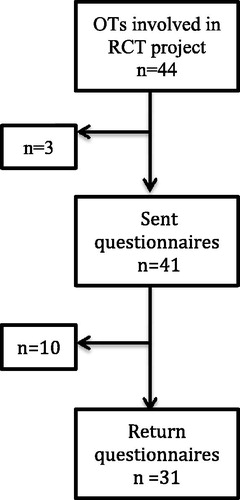

The closed-ended questions were recorded at Likert scales with four response alternatives constituting levels of agreement to different statements; disagree (=0), ‘partly agree’ (=1), agree to large extent (2=) and ‘strongly agree’ (=3). Contextual factors included questions about support from colleagues and managers, as well as about attitudes to research-based knowledge and their own experience of participating in a research project in collaboration with researchers. The confidence the OTs had in the usability and advantages of the intervention was reported on a vertical visual analog scale (VAS) from 1–10 where 1 represents no confidence and 10 represents strong confidence. Demographic information was collected in the questionnaire. The questionnaire was discussed in the research group until consensus was reached and was then tested by two clinically active OTs before it was sent out. The questionnaire [Citation30] was sent to the OTs by regular mail one year after participation in the research project had ended, see the flowchart in . Three OTs who participated in the RCT had ended their employment and their current addresses could not be found.

At the same time as the questionnaire was sent to the OTs, the managers (n = 23) also received a questionnaire with 12 open- and closed-ended questions covering time periods of care; number of stroke patients admitted to rehabilitation; whether reorganization or other reasons may have influenced rehabilitation at the time of the CADL project.

Data analysis

The OTs responses to the questionnaire one year after ending the CADL project are considered to be the main data. Data from the managers (n = 16) was analyzed to complement the understanding of the contextual barriers and facilitators that might have influenced implementation of the CADL.

Quantitative analysis: The closed-ended questions were analyzed descriptively using the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 22 according to the frequency of the four different responses to the questions. The closed-ended questions to the managers concerned type of clinic, number of patients, length of stay and employee turnover.

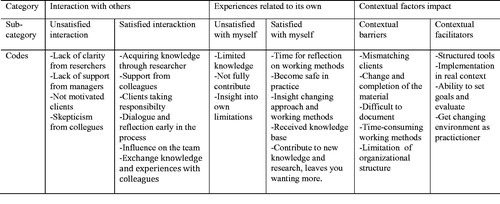

Qualitative analysis: The answers to the open-ended questions, where the OTs described their experiences of participating in the research project, were analyzed using qualitative content analysis [Citation33,Citation34]. The analysis sought to identify subcategories and categories that appeared to be important in the implementation process of the CADL intervention. In the first step, the informants' statements were divided into meaning units to further be condensed and related to each other through their content [Citation33]. In this stage, to assure trustworthiness, the author discussed with the coauthors as well as with other experienced researchers who were not involved in the project, regarding coding and the different categories [Citation35]. After summarizing the discussions, a coding scheme was designed by three of the researchers (CE, GE, UJ) who discussed and executed some changes until consensus for the entire coding scheme was reached. Thereafter the codes were grouped into subcategories that were finally summarized in three categories: interaction with others, experiences related to their own experiences and contextual factors’ impact [Citation33]. In an example of codes, subcategories, and categories is presented. The open questions in the questionnaire for the managers concerned whether organizational changes occurred during the project and how they affected care and rehabilitation, such as reorganization and the calicivirus (winter vomiting disease). These answers facilitated analysis in regard to the difficulty of including patients in the project. In conclusion, the categories and subcategories that were found in the qualitative analysis were weighed together with the answers from the quantitative section of the questionnaire and from the questionnaire addressed to the managers. The analyses of the different data resulted in a triangulation where quantitative statements were confirmed (or refuted) by the OTs’ and the managers’ own experiences and statements and vice versa.

Ethical considerations

The OTs received clear and repeated information that their responses would be coded to ensure and maintain confidentiality. Written informed consent was signed by the OTs the first day of the workshop. The OTs were not in regular contact with the researchers at the time of responding to the questionnaire, and their participation was voluntary. Ethical approval was obtained from the Regional Ethical Review Board in Stockholm (Dnr 2009/727-31/1).

Results

This study focused on identifying the key factors that appeared to be important to the OTs in the implementation process of the CADL intervention. The demographics of the participants are presented in . The questions (Q) from the questionnaire are presented in . The response rate is presented in . Data from the 16 managers showed that contextual factors mainly affected the implementation process in the various units as explained below.

The qualitative and quantitative results of this study were compiled and synthesized, starting from a structure based on qualitative categories () that emerged in the analysis and were supported by the quantitative data. The PARIHS framework constituted a part of the structure. These categories (see ) will be presented in the following.

Table 3. Categories after compilation and synthesized of qualitative and quantitative data.

The importance of evidence in clinical practice

One year after ending participation both quantitative (Q7) and qualitative data revealed the OTs’ views on the importance of evidence as research-based knowledge in clinical practice. An interest in developing clinical practice, the use of research-based knowledge (Q2 and 3) and their interest in literature and research findings related to clinical practice had increased (Q27).

Several of the OTs highlighted the importance of the structure and the theories underlying the CADL. The intervention had not only been put into use in the context of the actual implementation, but had also played a role in meetings with other clients. The OTs appreciated the usefulness of the intervention and its benefits, with an average of 7.5 on VAS (Q36 and 37).

The OTs considered that important knowledge had been conveyed in the workshop such as the contribution of information about the use of COPM (Q18). One of the OTs described the essence and the value of what had been conveyed in the workshop as follows: ‘COPM, client-centered approach, the process of occupational therapy – a partly new way of doing’. Some OTs requested more time for discussions during the workshop, as they expressed limited knowledge and understanding of how the intervention would be applied in practice (Q19). One OT described her experience of using the COPM like this: ‘Since I had not used the instrument I had difficulties in understanding the rating scale, it took some time to grasp it and to feel comfortable using it’.

The OTs’ descriptions from frustration to a satisfied sense of professionalism, as well as the use of the evidence-based CADL intervention, were significant experiences for the participants in the project. The workshop gave the OTs the opportunity to reflect and share their clinical experience. One OT described this as: ‘[In the workshop] feedback [was given] how you did and what others have done to be able to reflect on and improve their own work’.

For about half of the OTs, their perceptions of applying the CADL had completely or largely entailed a greater understanding of clients’ experience of their situation (Q22). All OTs, with the exception of two, reported that CADL had to some extent changed their approach (Q24). Many of the OTs associated this way of practicing with the client-centered approach, that it was the point of departure for the intervention, which had been the focus of the dialog during the workshop. After a year, the majority of the OTs agreed strongly or to a large extent that they worked with a client-centered approach (Q28). Most of the OTs had to some degree continued to apply the CADL for people with stroke one year after ending the project (23 of 29). In their role as OTs they felt more rigorous and focused in their meetings with the client. They reported that the use of the structure in the intervention enabled them to have a dialog and reflect together with their clients early in the implementation process (Q24). They expressed that in their interaction with the client they provided space for the client’s own ideas about how to solve problems, thus creating opportunities for participation. One OT described it as follows: ‘I’m MUCH more client-centered and often receive positive feedback on this from the client and their family members’.

The OTs described that they had reevaluated their attitude, for example regarding the client’s treatment and how their approach had changed. One OT expressed: ‘I've really changed my way of confronting a patient. I thought I was a good listener, but this has given me another dimension as a base for rehabilitation’.

In summary, both the quantitative and qualitative analyses showed that evidence including research-based knowledge increased knowledge and understanding of the clinical experience and the patient's experience and conditions had been of importance and impacted on their daily practice in the ‘long run’ for the majority of the OTs.

Contextual impacts

Contextual factors posed as facilitators

After one year, all the OTs largely acclaimed the value of meeting other colleagues in the context of workshops (Q14). The majority of the OTs were satisfied with the length of the workshop, and more than half stated that the time allocated for the various occasions was adequate (Q14 and 17). The OTs saw the potential and, in particular, that the intervention structure was a comprehensive support which made it easier for the OTs to work with the clients to set goals, plan, implement and evaluate the training. The following quotation exemplified this: ‘Querying the patients’ expectations and experience of the problems earlier in the process’.

Another factor that seemed to contribute as a facilitator was the option of conducting the implementation in a real environment where clients, regardless of context such as being at home, were offered the same intervention. The different circumstances and environments, and to ‘whom’ and ‘in what way’ were decisive for the OTs’ attitude to the usefulness of the intervention. The support and requests from colleagues and managers to use CADL were rated as high in the questionnaire but lower regarding the team members with whom they collaborated regarding the clients. (Q12 and 13).

The OTs gave several examples of factors that facilitated and changed their approach. These included the collegial exchange during the workshops; and the dialog and support from colleagues at their own workplace as well as from other workplaces that were prominent. One OT commented: ‘Good that many of us are taking part (in the workshop) from the workplace, to exchange experiences, support each other, this all makes it easier to initiate the changes’.

Most of the OTs stated that they had an operational manager who was positive to their participation in research and development projects (Q8). The OTs also stated that they had strong support to participate in the project and to use CADL from their immediate superiors. (Q9 and 10).

The managers may have influenced the OTs’ motivation to participate in the project by giving support from the organization. There were also major variations in the length of rehabilitation for the patient with stroke, ranging from 7 to 120 days.

Several OTs expressed their appreciation of the researchers in conjunction with the workshop and the conveyed knowledge of research evidence and space for reflections and discussions. Despite the initial skepticism, the OTs expressed that they valued the support the researchers gave them during the actual implementation of the intervention.

Contextual factors posed as barriers

Environments and conditions such as the OTs’ own workplace and lack of clients were parts of the context in which the intervention was implemented. These conditions affected the OTs’ perception of their role as ‘implementers’ and how the implementation process could be carried out. Further, the OTs reported difficulties including clients based on specific criteria, and this affected their satisfaction in terms of their professional role. The limited opportunities to contribute to the project to the extent requested caused frustration. Moreover, the lack of clients made it difficult to maintain their new knowledge. One OT described the experience as follows: ‘I feel I am unable to contribute much since I was given just two patients included in the ADL study….and I have not taken the time to perform all the steps’. Other challenges included motivating the client to participate in some parts of the intervention (Q29 and 35), with an implied dissatisfaction expressed as follows: ‘We’ve had problems getting the very ill patients to take part; they simply have been unable to join the project’.

Some OTs considered it time-consuming to learn to use the intervention, and difficult to document in the clients’ medical records since they felt that they needed to give it more consideration. Another OT argued that the structure of the intervention was too controlling and limiting. Many also thought that there was insufficient time allocated for the actual implementation, as the various parts of the intervention were too extensive. For some OTs, it was difficult to continue using CADL as they would have liked to when they changed workplaces and did not have the ‘right’, i.e. stroke, patients. Another OT considered that change of personnel had an impact on the work situation and, indirectly, on the possibility of implementing the intervention.

After one year, almost half of the OTs felt that their workplaces did not, or only partly, encourage the use of research results in clinical practice (Q4). The OTs stated that they had a limited habit of seeking research evidence (Q5).

Several OTs requested more information to be provided to their colleagues and other team members during implementation as they also lacked a greater commitment from them. Initially, the team mistrusted some parts of the intervention, which created a need for more clear information described as: ‘The team was not very cooperative; not that they opposed us, but they certainly were not helpful’.

The questionnaire sent to the managers revealed several factors that could have affected the implementation of the intervention. During the time of the project, nine of the 16 units had been reorganized or had been informed about upcoming reorganization and streamlining, which caused concern. Other reasons were low staffing resulting from a recruitment freeze, difficulties in recruiting staff and the calicivirus (winter vomiting disease).

In the responses to the open questions, the OTs described both an inadequate as well as a trustworthy interaction with the researchers, colleagues, clients and their families. In the interaction with the researchers in the workshop and in the implementation of the intervention, some of the OTs initially experienced ambiguity from the researchers in how the intervention should be designed and communicated. One OT wrote: ‘It was a bit vague at first – and the material was changed during the process rather than being sorted out right from the beginning’.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to identify the key factors important for the OTs in the implementation process of a complex intervention. The main result presented the various factors that appeared to have impacted on the implementing process for CADL for which the OTs perceived research-based knowledge as essential in their daily practice. The OTs perceived that the new intervention had improved the quality of the rehabilitation and had facilitated their planning and decision making in the client’s rehabilitation.

In order to develop new interventions there is a need of generation of understanding among professionals. The following discussion is based on three aspects of the various factors affecting the research utilization in the implementation process of a new occupational therapy rehabilitation intervention. The first aspect is about the importance of supporting the OTs’ acquisition of complex clinical skills through participation in a research-based workshop and in mentoring. Secondly, the OTs positive responses, as well as barriers to the multifaceted approach in supporting knowledge development and implementation and the last and third aspect will discuss the overall positive values of applying evidence to OT practice.

Supporting OTs’ acquisition of complex clinical skills

This present study showed that by participating in a research project the OTs got access to research-based knowledge and knowledge on underlying theories, such as the client-centered approach and the structured CADL intervention.

The OTs interest in using research-based knowledge in practice had increased during the project despite the fact that they felt less confident as professionals. However, a different picture was noted in the open answers where they described how their knowledge, with the support from the researchers, was anchored and had been transformed into productive confidence.

To be given the opportunity for clinicians to translate their knowledge is an important component in the process of change when implementing evidence in clinical practice [Citation36]. A previous study [Citation37] of clinicians’ attitudes towards evidence-based practice (EBP) [Citation10] and their experiences of collaborating with researchers indicated that the participating OTs experienced both an expectation and a skepticism to whether or not that knowledge would assist them to change their clinical practice. However, by participating in a research project they received confirmation of their previous knowledge, which facilitated the implementation of the new intervention [Citation37]. The value of the researcher providing the ‘right’ research evidence consistent with the needs in clinical practice was confirmed in this present study underlining the importance of considering and showing respect for the practitioners’ role and clinical experiences are also in line with i-PARIHS [Citation8]. The evidence-based knowledge relating to the clients’ perspective contributed to a change in the approach the OTs used when implementing this new intervention.

The OTs positive responses as well as barriers to multifaceted approach

There were both positive responses and barriers described by the OTs to the manifold implementation process used in the RCT study. The multifaceted approach was influenced by factors as the context, the OTs as implementers well as the researcher as facilitator. Some researchers have stated that if sustainable knowledge is to be achieved, it requires a multifaceted implementation intervention where educational materials, audit, and feedback must be included [Citation36,Citation38]. Another study, where OTs participated in a project about work rehabilitation, also included a workshop. The participants described that after the completion of that project, they became more aware and critical of their own way of working on the basis of evidence and that new knowledge meant that they worked differently with the client as well as with others in the team [Citation39]. Furthermore, Stevenson et al. [Citation40] found indications that receiving evidence contributes to a possible change in practice after an evidence-based educational session. However, the change was not as extensive as expected, which may be due to the fact that the local opinion leaders who conveyed the evidence could not ensure its quality.

The results in the present study confirmed that different environments and conditions as part of the context influenced for the implementation process as well as lack of appropriate clients for the OTs in the project. Some factors, such as the individual's interaction with the context, confirm what other studies have shown [Citation22]. The context was initially the workshop, which appeared to be a successful factor, together with the facilitation and access to evidence. Factors found in addition to the importance of the workshop included the interaction with the researchers, the use of research-based knowledge in practice and the knowledge translation process [Citation41]. The opportunity to discuss and reflect with other participating OTs and longitudinal support from the researchers on a regular basis during the project was important to maintain the new knowledge. This seems to be one of the key results of this study and contributed positively to the implementation. Grimshaw et al. [Citation38] have described that contextual factors, such as organization and attitudes from the environment and from individual clinicians, may hinder and be a barrier to knowledge translation. These conditions could affect the OTs perception of their role as ‘implementers’. The OTs stated that they had support and interest to use the intervention from the organization or colleagues and, to a lesser extent, from the team. The opportunity to get support from the team appears to have affected the implementation and sustainable change in the individual OTs as underlined by other researchers [Citation42].

The role as facilitators seemed to be very important and was contributing to the process of implementation when working in near collaboration with the clinicians. Being ‘served on a silver plate’ by the researchers seemed to influence the implementation process. Several studies have reported that having to search for and evaluate research evidence by themselves hinders the practitioners in translating research-based knowledge into everyday practice [Citation43,Citation44].

The role of the researchers and the researchers’ interaction with the OTs in the discussions, reflections, and support appears to be another facilitating factor and the collaboration that took place was very important throughout this process. Even if several participants admitted that they initially felt unsure of the researchers' intentions and was unclear regarding how to use the research they presented within the intervention they had a belief in the project and the role of the researchers. A recent study [Citation45] has shown that support from the researchers changed the OTs’ attitudes towards engaging in research from being an outsider to the scientific world to being included and then becoming a part of the research as an implementer of science. Creating a context built on a collaborative partnership between clinicians and researchers enabled the fusion of practice and science [Citation45].

For an intervention to be sustainable, it is necessary to review the parts that will affect both the barriers and facilitators associated with the implementation process, mechanisms and context [Citation5,Citation6,Citation46]. To change the way of working and performing something new, there was a need to create opportunities for how to practice the knowledge. The CADL structure was the tool to be integrated into practice, and in itself appears to be an additional factor contributing to the implementation process. The confidence in the usefulness of the intervention was confirmed when the OTs started using the intervention.

The client-centered approach implied that the participants reflected on their role in the assignment as an OT in interaction with the client and the structure of CADL facilitating the setting of goals with the client appeared to strengthen their sense of becoming more professional. This is in line with Kolehmainen and Francis [Citation42] who stated that to be professional means identifying clear and specific goals agreed upon with the client and evaluation of client change based on these goals after a certain time.

The overall positive values of applying evidence to OT practice

The OTs experience of professionalism after participating in the research project was estimated as high after one year can also be compared with the descriptions highlighted by Kolehmainen and Francis [Citation42] suggesting that the experience of being professional depends on the professional role and identity, skills, confidence in their capabilities, motivation and goals and the ability to change their behavior. A study by Wenke et al. [Citation47] showed that a motivation to participate in research provided an opportunity to develop skills in allied health teams. However, development of the professional role and identity had been confirmed only by some of the OTs to a greater extent. One explanation might be that, even before the intervention was implemented, the OTs felt that they worked client-centered and that some components of the intervention were consistent with previous values and practices. There was thus no need for change in work or behavior. In the closed questions the OTs indicated that they did not work more client-centered but that they used the intervention to some extent, and that over time they still had faith in the intervention and its benefits; thus knowledge had been integrated. However, in another study from the RCT project, Flink et al. [Citation48] found that training client-centredness have impacted the OTs’ documentation of client participation in finding common goals.

This research project has further been used as a model for developing new interventions, in collaboration between the researcher and health care professionals. This model for developing and evaluating an intervention is in line with how participatory research are conducted [Citation47]. Participatory research may be useful when the rehabilitation clinics have valuable data and practical experience and the researchers have the methods and theories [Citation47]. Participation in the workshop and involvement in a research project implied that to some extent over time, there was an increase in the OTs’ interest in the use of research and literature related to clinical practice [Citation49]. In addition, they also expressed a greater understanding of the client's perception of their situation as indicated in both the qualitative and quantitative analysis [Citation50]. These results illustrate that a prerequisite for implementation of the CADL was that the three elements evidence, context, and facilitation of different factors were present and interacting over time.

Methodological considerations

A strength in this study was that both qualitative and quantitative approaches were used, complementing each other. One possible limitation is the selected group, with a limited number of participants from the start. Another possible limitation could be the use of content analysis to analyze the written responses from the open questions in the questionnaire; here, the text was limited and the answers were therefore not exhaustive [Citation34]. According to Hsieh and Shannon [Citation51] this is not a hindrance but it is important to provide ‘an adequate description so that readers are able to readily evaluate its trustworthiness’ [Citation52]. Since the researchers responsible for the intervention designed the questions, their ideas could have influenced the questionnaire. However, they used the PARIHS framework’s perceptions [Citation10] of the implementation process in their endeavors to guarantee the quality.

Implication for occupational therapy practice

The present study has highlighted how, specifically in the area of stroke rehabilitation, OTs in close collaboration with researchers, can implement a new and complex intervention. Even though given access to research evidence conveyed and packaged by researchers to be transferred and become sustainable in clinical practice, the OTs needed time and opportunities in order for them to effectively implement the knowledge in the new intervention. Furthermore, the intervention required a structure in which it could be applied, as well as a supporting organization. Therefore, a prerequisite for integrating research-based knowledge into occupational therapy practice is that evidence, facilitation and context exist and interact simultaneously. Finally, in occupational therapy practice as well as in other health care professional areas there is a need of space and room for discussions and reflections over time to be able to do the translation of research-based knowledge based on the clinician’s previous experience and knowledge.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Kielhofner G. A scholarship of practice: creating discourse between theory, research and practice. Occup Ther Health Care. 2005;19:7–16.

- Thomas A, Law M. Research utilization and evidence-based practice in occupational therapy: a scoping study. Am J Occup Ther. 2013;67:e55–e65.

- Luker JA, Craig LE, Bennett L, et al. Implementing a complex rehabilitation intervention in a stroke trial: a qualitative process evaluation of AVERT. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2016;16:52.

- Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, et al. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. Int J Nurs Stud. 2013;50:587–592.

- Chambers DA, Glasgow RE, Stange KC. The dynamic sustainability framework: addressing the paradox of sustainment amid ongoing change. Implement Sci. 2013;8:117.

- Moore GF, Audrey S, Barker M, et al. Process evaluation of complex interventions: Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2015;350:h1258.

- Kitson AL, Rycroft-Malone J, Harvey G, et al. Evaluating the successful implementation of evidence into practice using the PARiHS framework: theoretical and practical challenges. Implement Sci. 2008;3.

- Rycroft-Malone J. The PARIHS framework – a framework for guiding the implementation of evidence-based practice (C) 2004. Oxford (United Kingdom): Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Inc.: Royal College of Nursing Institute; 2004.

- Bamford D, Rothwell K, Tyrrell P, et al. Improving care for people after stroke: how change was actively facilitated. J Health Organ Manag. 2013;27:548–560.

- Hagedorn HJ, Stetler CB, Bangerter A, et al. An implementation-focused process evaluation of an incentive intervention effectiveness trial in substance use disorders clinics at two Veterans Health Administration medical centers. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2014;9:12.

- Kristensen HK, Hounsgaard L. Implementation of coherent, evidence-based pathways in Danish rehabilitation practice. Disabil Rehabil. 2013;35:2021–2028.

- Powell-Cope G, Moore DH, Weaver FM, et al. Perceptions of practice guidelines for people with spinal cord injury. Rehabil Nurs. 2015;40:100–110.

- Tilson JK, Mickan S. Promoting physical therapists' of research evidence to inform clinical practice: part 1 – theoretical foundation, evidence, and description of the PEAK program. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14:125.

- Harvey G, Kitson A. PARIHS revisited: from heuristic to integrated framework for the successful implementation of knowledge into practice. Implement Sci. 2016;11:33.

- Menon A, Korner-Bitensky N, Kastner M, et al. Strategies for rehabilitation professionals to move evidence-based knowledge into practice: a systematic review. J Rehabil Med. 2009;41:1024–1032.

- NIRN. National Implementation Research Network. [cited 2016 Aug 27]. Available from: http://nirn.fpg.unc.edu/.

- Guidetti S, Ytterberg C. A randomised controlled trial of a client-centred self-care intervention after stroke: a longitudinal pilot study. Disabil Rehabil. 2011;33:494–503.

- Bertilsson A-S, Ranner M, von Koch L, et al. A client-centred ADL intervention: three-month follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. Scand J Occup Ther. 2014;21:377–391.

- Rycroft-Malone J, Seers K, Chandler J, et al. The role of evidence, context, and facilitation in an implementation trial: implications for the development of the PARIHS framework. Implementation Sci. 2013;8:1–13.

- McCluskey A, Vratsistas-Curto A, Schurr K. Barriers and enablers to implementing multiple stroke guideline recommendations: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:323.

- Michie S, van Stralen MM, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci. 2011;6:42.

- Kristensen HK, Borg T, Hounsgaard L. Aspects affecting occupational therapists' reasoning when implementing research-based evidence in stroke rehabilitation. Scand J Occup Ther. 2012;19:118–131.

- Vachon B, Durand M-J, LeBlanc J. Using reflective learning to improve the impact of continuing education in the context of work rehabilitation. Adv Health Sci Educ. 2010;15:329–348.

- Tham K, Borell L, Gustavsson A. The discovery of disability: a phenomenological study of unilateral neglect. Am J Occup Ther. 2000;54:398–406.

- Guidetti S, Asaba E, Tham K. The lived experience of recapturing self-care. Am J Occup Ther. 2007;61:303–310.

- Merleau-Ponty M. Phenomenology of perception. London (UK): Routledge; 2002.

- Kielhofner G. Model of human occupation: theory and application. Baltimore (MD): Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007.

- Townsend EA, Polatajko HJ. Enabling occupation II: advancing an occupational therapy vision for health, well-being & justice through occupation. Ottawa (Canada): CAOT Publications ACE; 2007.

- Law M, Baptiste S, McColl M, et al. The canadian occupational performance measure: an outcome measure for occupational therapy. Can J Occup Ther. 1990;57:82–87.

- Creswell JW, Plano Clark VL. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Los Angeles (CA): SAGE Publications; 2011.

- Shaw RJ, Kaufman MA, Bosworth HB, et al. Organizational factors associated with readiness to implement and translate a primary care based telemedicine behavioral program to improve blood pressure control: the HTN-IMPROVE study. Implement Sci. 2013;8:106.

- Ranner M, von Koch L, Guidetti S, et al. Client-centred ADL intervention after stroke: occupational therapists' experiences. Scand J Occup Ther. 2016;23:81–90.

- Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today. 2004;24:105–112.

- Krippendorff KC. Analysis: an introduction to its methodology. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage; 2013.

- Guba EG. Criteria for assessing the trustworthiness of naturalistic inquiries. ECTJ. 1981;29:75.

- Jones CA, Roop SC, Pohar SL, et al. Translating knowledge in rehabilitation: systematic review. Phys Ther. 2015;95:663–677.

- Eriksson C, Tham K, Guidetti S. Occupational therapists' experiences in integrating a new intervention in collaboration with a researcher. Scand J Occup Ther. 2013;20:253–263.

- Grimshaw JM, Eccles MP, Lavis JN, et al. Knowledge translation of research findings. Implement Sci. 2012;7:50.

- Vachon B, Durand M-J, LeBlanc J. Empowering occupational therapists to become evidence-based work rehabilitation practitioners. Work. 2010;37:119–134.

- Stevenson K, Lewis M, Hay E. Does physiotherapy management of low back pain change as a result of an evidence-based educational programme? J Eval Clin Pract. 2006;12:365–375.

- Tetroe J, Graham ID, Straus SE. Knowledge translation in health care: moving from evidence to practice. John Wiley & Sons; 2013.

- Kolehmainen N, Francis JJ. Specifying content and mechanisms of change in interventions to change professionals' practice: an illustration from the Good Goals study in occupational therapy. Implement Sci. 2012;7:100.

- Heiwe S, Kajermo KN, Tyni-Lenné R, et al. Evidence-based practice: attitudes, knowledge and behaviour among allied health care professionals. Int J Qual Health Care. 2011;23:198–209.

- Petzold A, Korner-Bitensky N, Salbach NM, et al. Determining the barriers and facilitators to adopting best practices in the management of poststroke unilateral spatial neglect: results of a qualitative study. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2014;21:228–236.

- Eriksson C, Erikson A, Tham K, et al. Occupational therapists experiences of implementing a new complex intervention in collaboration with researchers: a qualitative longitudinal study. Scand J Occup Ther. 2017;24:116–125.

- Zidarov D, Thomas A, Poissant L. Knowledge translation in physical therapy: from theory to practice. Disabil Rehabil. 2013;35:1571–1577.

- Wenke RJ, Mickan S, Bisset L. A cross sectional observational study of research activity of allied health teams: is there a link with self-reported success, motivators and barriers to undertaking research? BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17:114.

- Flink F, Bertilsson AS, Johansson U, et al. Training in client-centeredness enhances occupational therapist documentation on goal setting and client participation in goal setting in the medical records of people with stroke. Clin Rehabil. 2016;30:1200–1210.

- Kielhofner G. Scholarship and practice: bridging the divide (C)2005 by The American Occupational Therapy Association, Inc. 2005 [cited 59 7705978, 3o4].

- Dahlberg K, Dahlberg H, Nyström M. Reflective Lifeworld Research. Lund (Sweden): Studentlitteratur; 2008.

- Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15:1277–1288.

- Elo S, Kääriäinen M, Kanste O, et al. Qualitative content analysis: a focus on trustworthiness. SAGE Open. 2014;4:2158244014522633.