Abstract

Background: Social participation can be described as engaging in activities that provide interaction with others, and support for social participation may reduce loneliness and improve health. However, there is limited knowledge about social participation in a home care context.

Aim: To explore the perceptions and experiences of community-dwelling older adults with regard to aspects related to social participation in a home care context.

Materials and methods: Seven home care recipients, aged 79–94 years, from two Swedish municipalities participated in semi-structured interviews. The interviews were analyzed using qualitative content analysis.

Results: The study identified the central theme, Personhood in aloneness and in affinity, as important in accomplishing satisfactory social participation. The results incorporated cultivating personal interests and navigating occupations, as well as having one’s needs seen and experiencing mutuality in social encounters.

Conclusions: The study nuances existing knowledge about social participation among older home care recipients, and the findings strengthen the importance of framing a home care environment where recipients can cultivate personhood and be recognized as valuable individuals with relevant needs.

Significance: This study extends current understandings of the variety and richness of the social participation and occupational engagement enjoyed by older home care recipients, to be considered in research and practice.

Introduction

To be able to build and maintain relationships and to participate in society have been identified as key components for healthy ageing [Citation1]. These components are reflected in the concept of social participation, which have been described as engagement in activities that provide interaction with others in society or the community [Citation2]. However, there are several definitions of social participation used in the research literature and a unanimous definition have not yet been reached [Citation3]. As social participation is a complex construct, a taxonomy by Levasseur et al. [Citation2] adds understanding to the concept, by synthesizing descriptions and ranging levels of involvement in social occupations to illuminate the scope of the concept: preparation for connecting with others, being with others, interacting with others without physical contact, doing an activity with others, helping others, and contributing to society. To further grasp the meaning of social participation, the notions of ‘perceived togetherness’ [Citation4] and ‘enacted togetherness’ [Citation5,Citation6] add understanding to social participation, by focussing on the qualitative consequences of participating in social occupations as well as highlighting the place and process where meaning is produced. Low levels of perceived togetherness in social interaction have also been associated with loneliness [Citation4,Citation7], and in this paper, social participation and perceived togetherness, are viewed as the opposite state of loneliness. Loneliness in general increases in older age [Citation8], and more than half of the Swedish home care recipients report that they experience loneliness [Citation9]. Loneliness constitutes a major risk factor for mortality and decreased health and wellbeing [Citation10–12] by, for example, affecting blood pressure and the immune system [Citation12], as well as inducing psychological distress [Citation13–15]. Loneliness can be defined in many ways, but this paper uses the term to refer to a painful, self-identified experience, characterized by a discrepancy between a person’s actual and desired interpersonal relationships [Citation16–18]. There is a conceptual distinction between the subjective experience of loneliness and objective ‘social isolation’ [Citation19], but in colloquial language, these distinctions are not always as clear and this must be considered when evaluating qualitative research. In contrast to loneliness, social participation seems to be related to increased quality of life [Citation15], decreased morbidity [Citation20] and mortality [Citation21], and interventions to enhance social participation have shown the potential to reduce loneliness [Citation22]. Social participation can be supported via leisure activities [Citation23], and it seems that the association between leisure activities and health is stronger in older adults [Citation24] than in younger persons. However, social opportunities may be hampered by, for example, disability, reduced mobility, various environmental factors [Citation25,Citation26] and loss of significant others. It is apparent that loneliness and social participation are composite phenomena, impacted by a range of issues. Social participation may be achieved through an array of occupations that may well be entangled with other daily occupations, and therefore, home care services are in a good position to identify problems and provide individually relevant social support.

To remain safely at home and in the community as a person ages, known as ‘ageing in place’ [Citation27], is a conceptual framework in Swedish eldercare and is often referred to as staying in the same or a familiar place or neighborhood throughout ageing [Citation28]. The focus of eldercare lies on in-home assistance from home care services [Citation29] and residential care has been downsized in recent years [Citation30], making home care services the most common form of eldercare today (after security alarm) [Citation31]. Any person experiencing difficulty performing daily activities has the right to apply for assistance. Local municipality assessors evaluate the applicant’s needs and decide whether support will be granted, and a home care organization provides the support granted. To implement the services as a functioning supportive experience is a rather complex matter that requires, for example, adaptive communication skills and knowledge about the effect of social stimulation on health and wellbeing [Citation32]. Home care staff usually have assistant nurse training (or lack formal training), and their work situation has been described as demanding [Citation33], and that the work situation for staff in eldercare can be stressful and low in control: factors that may affect their health and also the quality of their care output [Citation34]. Home care should apply a person-centred approach, although research suggests that person-centred values are not strongly endorsed by the organizational cultures of home care [Citation35]. In addition to home care services, a home healthcare team consisting of occupational therapists, physiotherapists and registered nurses supports health and participation among community-dwelling frail older adults. The Social Services Act regulates Swedish home care services and stipulates that social services should strive towards providing older adults the ability to live ‘independently’ and have an ‘active and meaningful existence with others in the community’ (SFS 2010:427) [Citation36]. Social aspects of care are considered important by home care recipients, even when these are not expressed as a formal purpose of the service [Citation37]. Although participation in social and leisure activities has been established as beneficial for health, it is unknown how home care services specifically address social needs [Citation38]. Some research implies that social needs, in general, may be addressed less than practical needs within home care settings [Citation39], and a Swedish study shows there are insufficiencies and inconsistencies associated with home care assessments and plans for supporting social needs [Citation38]. However, loneliness and social participation are complex and interrelated in everyday life, and with the need for assistance in daily life, this becomes even more multifaceted. There is a lack of knowledge about how social participation is experienced in the specific context of living with support from home care services, and about how receiving home care services affects these experiences. The aim of the current study was to explore the perceptions and experiences of community-dwelling older adults with regard to aspects related to social participation in a home care context.

Materials and methods

Study design and setting

A qualitative design utilizing semi-structured interviews was selected for its capacity to increase understanding about thoughts and feelings related to lived experience [Citation40,Citation41]. The study is part of an ongoing research project funded by FORTE (Ref. no.: 2016-07089) with the overall goal of developing and evaluating a working model for addressing loneliness among older adults in a home care context. All authors were registered occupational therapists, female, and native speakers of the Swedish language. The second and third authors have extensive experience in qualitative research and research with older adults and home care services. The researchers had no relation to the interview participants prior to data collection. Ethical approval was obtained by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Umeå, Ref. no. 2017/187-31M.

Sampling and participants

Persons 65 years or older who were receiving home care to meet social needs and/or experiencing loneliness were invited to participate. Persons with a pending application for residential care, extensive cognitive and/or communicative difficulties were excluded. Purposive sampling was utilized, and to ensure the target group was reached, recruitment was carried out via the home care organization. The home care workers in two municipalities were informed about inclusion/exclusion criteria and supplied with information letters to forward to older adults they thought fitted criteria and might be interested in sharing their experiences. Recruitment proceeded over several months, with ongoing communication and information meetings with the home care workers, in order to ensure that they felt comfortable about how to introduce the invitation letter and that they understood the inclusion/exclusion criteria. The older adults who received the information letter and expressed preliminary interest to participate gave their permission to be contacted by telephone by the first author to receive verbal information and to consider whether they thought they fitted the criteria and if they wanted to participate. Those who decided to participate also chose the time and location for the interview at this telephone call. Contact information for thirteen potential participants was collected, of which two were excluded due to the age requirement and three declined participation after receiving verbal information. Eight persons were willing to participate; however, one person wished to book the interview date at a later time but could thereafter not be reached. Altogether, seven older home care recipients were interviewed. Demographic data were collected via a questionnaire: five females and two males, 79–95 years of age and reported level of education between 6–12 years, participated in the study. Self-reported health varied from good to poor, but all reported that health problems affected daily life activities. All were widowed and living alone. Four participants perceived themselves as lonely sometimes or often and were not fully content with the number of their social contacts in daily life ().

Table 1. Participants’ demographic characteristics.

Data collection

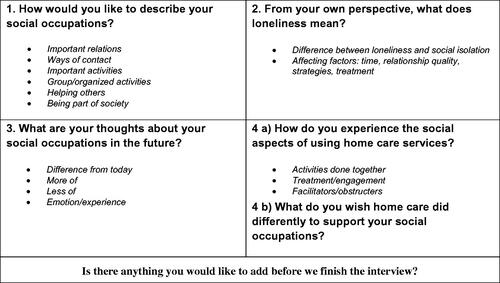

A semi-structured interview guide was constructed and tested in a trial interview with an older adult with previous experience of home care services in order to prepare for interviews, followed by changes to make questions more open-ended, and follow-up questions were changed into potential sub-topics. The trial interview was not included in the analysis. The final interview guide consisted of four topics: (1) current social participation, (2) loneliness, (3) desired social participation and (4) home care services’ impact on social participation, and five open questions in colloquial language were derived from those topics (). All interviews were conducted by the first author in the participants’ homes, at their kitchen table or living room sofa. The interviewer strived to encourage a calm and friendly atmosphere and to make the participant experience mutual comfort and undivided attention. All interview visits began and ended with small talk, and at the majority of visits (if the participant offered), coffee and/or snacks were shared during or after the interview. After initial small talk, the interview leader repeated the information previously provided during the initial phone conversation about audio recording, the possibility to withdraw and what would happen with the material after the interview, and verbal and written consent was collected along with a demographic questionnaire. The same question initiated all interviews, but thereafter the participant’s narrative directed the order of topics and questions. The interviews lasted for 63 minutes on average (35–93 minutes), excluding the provision of information about the study and small talk. An effort was made to keep questions clear, and to ensure understanding by asking for clarification when needed. All participants were encouraged to make contact if additional thoughts or questions arose and were offered the option to receive a copy of the transcript. Four accepted and were mailed their transcript along with a handwritten note welcoming contact. No participant made contact after the interview. The interviews were conducted from August 2017 to March 2018.

Data analysis

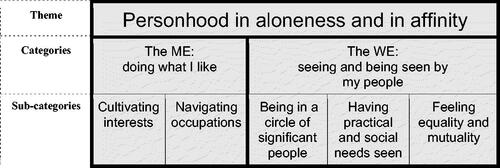

The audio recordings were transcribed verbatim and checked for the deviation between recording and transcript. The analysis was guided by qualitative content analysis [Citation42], as this offered a systematic analysis process to interpret the qualitative data, through focussing on expressions of experiences and identifying similarities and differences in manifest and latent data content [Citation42]. Emphasis or emotional expressions were noted in transcripts to ensure the transmission of intrinsic meaning and strengthen trustworthiness [Citation42]. Transcripts were read several times to obtain a sense of the whole. Meaning units relevant to the aim were identified and coded with a few summarising words. Each code was given an ID number for location in the transcript, and the whole context was considered throughout condensing and coding. The codes were compared based on differences and similarities and sorted into five sub-categories and two categories, which constitute the manifest content. Notes were taken during discussions and analysis in order to retain thoughts that arose about possible interpretations. Finally, the underlying meaning of the categories – the latent content – was formulated into a theme, and the wording of categories and sub-categories was finalized through extensive discussions between all of the authors. The analysis resulted in one theme, two main categories, and five subcategories ().

Results

Personhood in aloneness and in affinity

The theme Personhood in aloneness and in affinity was abstracted from the main categories: The ME: doing what I like and The WE: seeing and being seen by my people. Both main categories are permeated by desires to foster individual personhood through alone activities and through affinity to relevant others. To recognize and actualize ‘myself’ through doing and managing individually relevant occupations (sometimes performed alone), and through being validated as ‘myself’ in interaction with relevant others, were identified as important aspects of achieving satisfactory social participation. Personhood emerged through the analytical process as a common denominator throughout the findings and is presented as an overarching theme. The analysis revealed aspects of being in a physical and social environment that nurtured opportunities to engage in occupations and interactions that echoed the participants’ perceptions of themselves, as valuable for satisfactory social participation.

The ME and the WE could be seen as two entities that both relate to participating socially and experiencing togetherness, but that also relate to each other. To understand how opportunities to cultivate interests and to navigate occupations (the ME) affect a person’s satisfaction with his/her social participation, it may be necessary to consider the characteristics of the person's relationships (The WE) and vice versa.

The ME: doing what I like

This main category reveals barriers and promotors for realizing interests and engaging in occupations, and consequences for social participation when adjusting or not adjusting to changed circumstances. The phrasing ‘… doing what I like’ reflects both sub-categories by entailing a conscious double entendre, as it refers both to preferences; doing occupations I like to do, and to autonomy; doing occupations the way I like to do them through sustaining an active role in navigating occupations. The first subcategory, Cultivating interests, shows that individual interests can function as fuel for staying (socially) active and that both occupations performed alone and with company can affect social participation. The second subcategory, Navigating occupations, highlights the importance of having the possibility to govern what to do and when and where to do it, as relevant for feeling content with one’s social situation.

Cultivating interests

The analysis revealed that doing occupations of personal interest could function as social fuel, and sometimes this also meant adjusting or integrating new occupations within a broad realm of interest. The participants expressed that engaging in occupations related to their interests were important, and both occupations performed alone and occupations performed with others could affect satisfaction with social participation. Interests differed, but some example topics were cooking/eating, clothes/shopping, culture/education, exercise, nature and religion. In addition to specific interests, there were also general wishes to do stimulating things within their realms of interest:

To get away, to get out, not just to get air … but something else … to see something, experience something, a conference, anything.

Interests pursued alone, such as media consumption, arts and crafts and walking in nature, could enhance wellbeing and diminish feelings of loneliness by keeping participants busy and giving meaning to time alone. Those occupations performed alone could also spark social interaction by providing conversation topics or result in a (created) product that could be given and sought after by significant others. Interests enacted in occupations performed alone could also evolve into occupations with others.

In order to keep engaging in cherished interests and to remain content with their situation, the participants often adjusted to their declining abilities. This could mean adding new occupations within the interest or doing them in a different way, and if the occupation was altered in an acceptable way, there was little perception of loss. Some had requested support for adding new occupations from professionals such as occupational therapists or home care workers, but their ideas were often dismissed as unrealistic. Community-based activity centres were described as ‘okay’, but also as offering uninteresting occupations. A place for older adults to contribute to each other’s lives was requested:

Today, all of the pensioners are sitting alone in their own separate hives without connections … I’m sure many have a lot to offer. Maybe they can play guitar or sing and tell about their lives.

It was mentioned that pensioners could wrongfully be viewed as a homogenous group and that older adults’ wide range of interests and abilities needed to be further addressed in the occupations offered:

You can’t just bunch everybody up and say ‘a group of pensioners’, because how you are and what you can and want to do is individual.

When valued interests could not be pursued by adjusting or exchanging occupations, participants could instead re-evaluate their need to actualize the interest and strive to come to terms with the interest not being enacted in the present. The participants described accepting their situation, only focussing on the future, or comparing their situation to those worse off, as ways to deal with losing their abilities to do what they used to do. Some expressed that they were content overall in their aloneness and despite reduced opportunities to actualize valued interests, while others voiced frustration, sadness or loss: ‘everything disappears’. Feeling lonely and discontent, despite practical help and a caring family, could also involve elements of shame:

I have a lot to be happy about, really, but sometimes I feel like I’m being ungrateful when I feel sad, like they can’t do everything for me, so that I’m not happy. And I’m a little ashamed about that.

Navigating occupations

To feel ownership of occupations and navigating occupational life were revealed as relevant for satisfactory social participation. The analysis revealed three aspects of navigating occupations: opportunity to navigate in time, in activities, and in space. Freedom to choose how to spend one’s time was described as valuable to avoid feeling lonely and to enjoy the social parts of life. The preferred balance between social time and non-social time was individual and could be part of how they viewed their time and themselves. While some described themselves as social persons, others expressed a self-view of being most comfortable in solitude. However, those who expressed preferring time alone also described regular social interactions and how these encounters enriched their lives. Being able to self-manage when to be alone and when to have company seemed to be an aspect that mattered. For example, one participant had an agreement with home care that the ‘social stimulation’ service would be kept optional (via telephone contact prior to the scheduled visits to decide whether the participant felt like a visit or not). This resulted in feelings of spontaneity and reduced the feeling of loneliness during time alone. Another participant expressed that being alone, despite the unpleasant aspects, also carried characteristics of freedom: ‘I don’t have any mental suffering from being alone … sometimes I think I am fortunate that I can do what I want, almost’. The home care service called ‘social stimulation’ was described as a 45-minute visit from home care without a specific task previously determined, and the care recipient was free to choose what to do together during this visit. Choosing what to do could be described as a ‘wonderful freedom’. However, there were also problems with a short time frame, not knowing who was coming, and uncertainty concerning what would be permissible to include, and this was expressed as limiting possibilities to take full advantage of this freedom. Being able to manage occupations on their own were described as a valued aspect of being able to participate in social occupations and feeling confident. Receiving a small amount of help, described as a ‘push’, such as information or encouragement about local events, assistance, and reassurance, in the beginning, could make a big difference in regaining ownership and navigating their occupational life. The participant in the following example was feeling anxious about walking alone to the activity centre and had at first been denied escort:

But eventually they followed me halfway, and I walked the rest of the way on my own … they saw I could manage … and I was happy and proud I could do it.

Navigating occupations could also concern mobility: moving freely in space was considered to be important for social participation. The participants described how using a wheelchair or walker could impede travel or entering other people’s homes. These aids could be difficult to manage on public transport or over doorsteps and staircases, making participants more reluctant to visit friends or to plan occupations: ‘before, I was part of my group [of friends] … because then I could walk … so it has inhibited my social life, absolutely, that I’m in a wheelchair’. It could also feel inappropriate to visit others while pushing a walker, or to ask for assistance with a wheelchair: ‘I don’t think I can have any demands. I can’t count on them pushing me around in some wheelchair’. Stopping driving was described as something that increased loneliness, and difficulties in fully replacing their means of transportation was common due to, for example, a reluctance to ask for lifts or to call a mobility service, extra costs for bringing walking aids or difficulty arranging long-distance mobility travels. A lack of outdoor mobility could cause frustration and feelings of limitation:

Before, I could get out, to the city, and look at clothes or something, now I can’t do anything! Now I just sit here, like an old crow.

The WE: seeing and being seen by my people

This main category accentuates important relationships, social interaction with relevant others and what creates quality in these interactions. To ‘see and be seen’ represents elements of mutuality and reciprocity, of being acknowledged and acknowledging others. ‘My people’ refers to people in general who are relevant to the older adult, and with whom the relationship conveys components of recurrent and reciprocative relating towards one another. This category is built on three sub-categories, where the first: Being in a circle of significant people, reveals which relationships were valued, about circumstances affecting these relationships, and about how having or missing these relationships affected satisfaction with social participation. Having practical and social needs seen shows that practical and social care can be seen as being intertwined with each other and how both may affect social participation. Feeling equality and mutuality highlights aspects of social interaction; to meet and be met with interest and respect and how being a valued partner in the social encounter establishes quality in relationships and thus promotes social participation.

Being in a circle of significant people

Belonging to a social circle of people they knew and could count on was expressed as an important part of social participation, and interaction with children and extended family was highly valued. Short distances could enable frequent contact, and having children living in the same town or even the same property could create feelings of calm and security and facilitate social interaction. Subsequently, larger distances often meant that contact was less frequent or did not take place at all. Another important relationship was with long-term friends, and such relationships could offer the opportunity to ‘talk about everything’. The telephone could serve as a supplement or replacement for meeting in person and could help maintain relationships with distant friends and family. Subsequently, difficulty handling the telephone could cause concern about not being reached. Neighbours constituted another type of valued relationship that could provide nearby access to social interaction or help with practical things. Not being content with one’s social circle, for example, because of moving, could spark initiatives to increase contact with old acquaintances or to strengthen loose connections, for example by visiting public places hoping friends would stop by or by ‘courting’ newly found acquaintances with the aim to deepen friendships. These endeavours, however, did not always pay off. One participant concluded: ‘you have to be born here to have a chance to make friends’. Experiences of losing loved ones, both spouses and friends, were common. Losing a spouse could result in an array of aspects associated with loneliness and participation, from having fewer chores to losing a best friend and confidant. But it could also change the conditions of the entire social arena:

Without a doubt it’s sad. Maybe not so much my spouse’s passing away in itself, as that the life I had then was so utterly different from what I have today.

Visits from home care workers sometimes accounted for the greatest number of regular face-to-face social contacts for the participants. One participant described an ordinary day as follows: ‘I sit here on this chair and receive the home care workers’. It was appreciated when home care staff made time to sit and chat, and for some, it could constitute the only break in loneliness and be the high point of the day.

Having practical and social needs seen

Having one’s needs seen was considered important, and practical and social needs seemed not always clearly separated from each other. Receiving help with practical needs and being given enough time also seemed to be interpreted as an expression of overall care and respect, and could also mediate social interaction via socialising during or after the chores were carried out. The care workers’ cheerfulness while doing chores could mitigate loneliness for some participants. Practical tasks could also be consciously used to obtain more social time with care workers, by asking for extra help or leaving things undone. Beyond chit-chat, home care workers could also show more care by, for example, asking about their day, patting their back, or picking up on the need to talk in other ways, which could alleviate loneliness. Care workers who were attentive to practical needs and showed eagerness to do extra things were highly appreciated and these actions were interpreted as the older adult being cared for and seen. For some, this contribution to social life was considered enough, while others wished for more time to socialise with home care workers, and feelings of loneliness prevailed. Not having practical needs seen appeared to be connected to feelings of not being known or seen. When care workers did not ‘see for themselves’ what needed to be done or did not do chores the ‘right way’, it could cause frustration and fuel feelings of social disconnection and disrupt the sense of ‘we’.

A lack of time for both practical and social visits by home care was another aspect that participants mentioned as a frequent and negative aspect. Observations such as ‘they don’t seem calm’ and that they only did what they absolutely had to do were common. Many participants felt sorry for the carers’ work situation and this made some participants avoid asking the careworkers to stay or talk when they felt lonely. Even if care workers were considered good at hiding their hurry, participants could still feel there was not enough time for their needs:

They make it seem as if we have all the time in the world, even though you know do they don’t. You just have to turn around and they are out the door.

The feeling that home carers had too little time for the participants had various emotional consequences. For some, it was mostly expressed as an observation that raised concern for the care workers, while it made other participants feel resignation about the possibilities with home care and made them frequently withhold requests to have their social needs seen or met.

Feeling equality and mutuality

Whether the social interaction concerned relationships with home carers or other relationships, the most highly valued aspects of social interaction concerned having things in common and the presence of mutual elements that conveyed a feeling that both parties benefitted from the social interaction. Even with their closest family members such as children – whom participants assured were all equally cherished – to share something still added extra value to their social interaction. Examples could be having a common interest or profession, or having a similar personality. Socialising with people of a similar age, meeting others who had ‘been around for a long time’ and sharing life experiences, were often brought up as adding value to participating in social interaction. This could be described as ‘being on the same wavelength’ or thinking alike. Consequently, a lack of peers could diminish the quality of social occupations. In the following quote, the participant loves dancing but has now stopped attending dances due to the lack of peers to connect with:

I love to dance…but there are no dances to go to, because there are only old people in wheelchairs there … they should be about my age, not much older because otherwise they’re often sick … but I’m not sick … It would have been great fun with that type of people, maybe 80 or 85 [years old].

The need for a sense of ‘we’ was also obvious in the interaction with home care workers, and was conveyed through a strong appreciation for mutuality and reciprocal elements in those relationships. Some participants shared stories of close and personal relationships with care workers, where the valued aspect was perceived mutual trust and sharing of their everyday lives, and there was a feeling of two-way confidentiality and reciprocal confiding. They felt these care workers liked them and liked visiting them and that these relationships resembled friendships or family relationships: ‘they are both my home carers and my friends’, or ‘she was like a mother to me’. These seemingly mutual elements of the relationships greatly diminished feelings of loneliness. Sometimes, professional relationships with carers also evolved into actual friendships or surrogate family relationships outside the home care context. This honest respect for some care workers could also have a contradictory effect: participants could feel they had to respect carers’ ways of doing chores, and despite feeling frustrated and sad, they would not complain but instead blame themselves for wanting things done differently and then redo a chore themselves after the home care worker had left.

The quality of ‘social stimulation’ was often affected by whether or not they had a mutual relationship with the carer, and experienced a sense of ‘we’. Even though the freedom of choosing occupation was valued, the mutual relationship was described as an additional important aspect to creating qualitative social time. The decision depended just as much on the care worker’s wishes and abilities, and if they did not know each other, ‘social stimulation’ became a chore for the older adult to come up with something to occupy the care worker instead of being part of a mutual social encounter.

…and he couldn’t speak Swedish. So we had to come up with something to do. He had told me he was a chef, so I asked if he could make creamed mushrooms – I had some chanterelles. But I can’t cook in Swedish, he said. So we helped each other, it worked out. But I didn’t exactly need that, and it’s not exactly me they’re helping.

There were also narratives in which participants did not feel that they were being viewed and treated as equal and capable people; for example, that others were talking over their heads, nagging or persuading them to make unwanted decisions. Exaggerated praising could also convey aspects of belittlement. Although appreciated, excess praise could make participants feel like nothing was expected of them. Some experienced that they were often were not addressed as equal adults but rather treated like children, which seemed to cut off the feeling of mutuality and turn participation in one-way communication.

We are adults, and have clear thoughts, so that thing about treating us like children, that has to go. … It’s the worst thing I know, we are on the same level as anyone.

Discussion

The aim of the study was to explore the perceptions and experiences of community-dwelling older adults with regard to aspects related to social participation in a home care context. The analysis revealed that both occupations performed alone and occupations performed together with others could affect the experience of social participation, and furthermore, that these occupations should contain elements of actualizing or validating personhood. For social interaction to be perceived as an experience of participation, aspects of having needs validated and experiencing mutuality in the social encounters were of importance. Both ‘Doing what I like’ and ‘Seeing and being seen by my people’ should be viewed as related entities that may synergistically work to strengthen social participation that meets the needs and expectations of older adults: in other words, perceived togetherness. The notion of personhood has been explored in many disciplines, from philosophy to gerontology, and can be understood as a response to the question ‘what is a person?’ [Citation43]. In these findings, the meaning of ‘personhood’ resonates with the individuals’ perceptions of their identities, as reflexively understood in relation to their personal narratives [Citation44], and as acquired or actualized through relationships with others [Citation35]. This can, for example, be seen in the participants’ wishes for attending activities with people of the same age or interacting with people ‘on the same wavelength’, or that interaction even with close family members was enhanced if they shared interests or personality traits. To experience ‘sameness’ can be seen as resonating and strengthening their sense of personhood. Personhood has been argued to be the core of person-centeredness, and as such, is central to relevant and respectful care services [Citation35]. The term ‘occupational identitiy’ is another way of understanding identities, as operationalized through desired or executed occupations. Occupational identity has been defined as a compound definition of the self, and as related to what individuals want to do, find enjoyable and interesting to do, and serving as a motor for volition [Citation45]. An example that may illuminate the importance of occupational identities were performing creative occupations of interest in solitude, that resulted in a product that family and friends wanted to take part in and that later became a topic for social interaction. This strengthens the interpretation that occupations that means engaging in personally relevant activities can ameliorate the sense of identity, and strengthen the role in the lives of significant others. Engagement in occupations have been described as fuelling understanding and negotiation of identities [Citation46,Citation47], and it seems probable that personal interests can guide an individual’s path into a relevant social context. By contrast, research [Citation48] indicates that social opportunities may be dismissed by lonely older adults if those opportunities do not fit individual wishes and values, as such opportunities may threaten some aspects of identity. This could be resonated in examples from the current study, where participants were reluctant to attend senior activity centres when they did not offer interesting occupations or peers with similar interests. As occupational engagement can shape and fuel occupational identities, this reluctance of participating in specific activities could be seen as a conscious choice. On the other hand, other studies have shown that senior activity centres can provide good opportunities for activities of choice and interaction with others [Citation49,Citation50]. Therefore, it seems an important task for municipalities to ensure that community activity centres offer an individualized range of occupations in order to provide a viable place to establish social connections. A guideline from Swedish social services states that activity centres for persons with dementia should have a person-centred, rehabilitative approach and cooperate closely with home care services and rehabilitative professionals such as occupational therapists. For example, the importance of the occupational therapists’ assessments of the person’s resources and challenges, of continuing assessments, and of the possibility for occupational therapists to contribute by collaborating with activity centre staff, is highlighted [Citation51]. These recommendations provide grounds for occupational therapists to argue for increased involvement in the development of activity centres, as well as in supporting occupational engagement among attenders.

In the present study, occupations performed alone were also reported as increasing connectedness to a larger context, such as to the participant’s profession or society at large. In some research [Citation23], activities performed alone, such as listening to the radio or using a computer, did not show any association with social connectedness, while others [Citation52] report the opposite. The current study supports the notion that occupations performed alone may well harbour the potential for social participation by supporting inclusion in societal discourse and act as a mediator for social contacts, as well as the notion that supporting both interests performed alone and those performed with others may positively affect social participation and life satisfaction.

To have the possibility to navigate what to do and when and where to do it, and to self-manage the balance between time alone and social time was connected to feeling more content with one’s social situation, which is in line with other research [Citation53]. ‘Navigating occupations’ could be discussed through concepts such as autonomy, independence, and agency. Autonomy is often depicted as an essential value in health care provision and as an innate part of participation and is defined as the ability for independent action without support [Citation54]. However, autonomy as a goal has been criticized for not adequately capturing the realities for most older adults [Citation55], and for being based on individualism and an untenable aspiration in the context of eldercare [Citation56]. The participant who felt self-sufficient by receiving an escort halfway to the activity centre shows how experiences of autonomy are not always as clear-cut in the lived experience. Closely related to autonomy is independence and the connected term interdependence, which refers to experiencing reciprocate influence and mutual dependence between oneself and others in a social group. A person is interdependent when performing an occupation with a choice over his/her actions, and the occupation is performed in a supportive environment with interaction with others to overcome obstacles [Citation57], which perhaps makes ‘interdependence’ a more nuanced way of understanding the current result. In the framework Occupational Therapy Independence Framework (OTIF) [Citation57], a hierarchy of independence, interdependence and dependence is defined, including instructions on how to intervene in such issues, making it an accessible concept for occupational therapists to use. Another applicable concept is agency, which has also been seen as a central part of personhood [Citation43]. ‘Agency’ adds understanding to what one aims to achieve by being independent or interdependent. From a social constructionist perspective [Citation58], agency is understood as the capability to act intentionally within a social context together with others, and furthermore, that by understanding agency as differently constituted across time and space, and seeing empowerment and disempowerment as conjoined rather than polarised, power relations are positioned in the relevant context [Citation58]. The participant with a ‘renegotiation agreement’ with home care illustrates how agency can be aided even when social support from home care is needed. Through care workers checking in by phone prior to the weekly ‘social stimulation’ visit, the participant experienced the visits as spontaneous and mutually arranged. It seems probable that through interdependence with their social circles, older adults’ potential to reach empowerment and agency could increase. To continue playing a role in others’ lives could contribute to feelings of authority, self-worth and power (power as an aspect of reciprocity rather than self-sufficiency) [Citation58]. Mobility aids and mobility services may play a valid part in keeping these roles, and research has shown that access to transportation and local community supports social participation [Citation59], identity and independence [Citation60]. Perhaps a lack of this perspective depicts why mobility aids – whose sole purpose is to enable – were sometimes instead considered to be hindering participation and increasing loneliness. To strengthen agency and thus strengthen opportunity for social participation, occupational therapists may need to enforce a stronger focus on identifying preferred social arenas outside the home, as well as on thoroughly assessing and addressing social, physical and occupational barriers [Citation45] in the process of prescribing mobility aids and other services.

Contact with friends and family was considered very important for social participation. The findings also indicate that the presence and impact of home care service personnel were quite significant for the participants’ daily social interaction. Help with practical chores and talking while receiving this help were appraised as means to have social needs seen and sometimes met, but there were also strong parallel wishes to meet peers and participate in social occupations outside the home. However, aid with practical chores from home care services is considerably more common than socially aimed interventions [Citation39], and research indicates that talking [Citation61] and activities inside the home are common constructs of how older adults can and want to be social [Citation62,Citation63]. These dual wishes for social support might illustrate the conjunction between aspirations emanating from agency and wishes based on what seems to be realistically accessible.

Experiencing mutuality and equality in social encounters was described as an important relational aspect for supporting social participation and diminishing loneliness. Somewhat surprisingly, this was also applicable to relationships with home care workers – a relationship that is innately unequal in power in the sense of being a service provider–service recipient relationship. It seemed that they sometimes, in parallel with the professional relationship, also developed a personal relationship and that these relationships were difficult to precisely distinguish from one another. This personal aspect was highly valued and was considered mutual, reciprocal and greatly important for life satisfaction and for diminishing feelings of loneliness. Another interview study with older adults [Citation64] demonstrated that older adults can perceive care worker relationships as mutual, with true friendship bonds where both parties contribute to the relationship, and also that feeling of isolation could emerge if reciprocation to care workers was not accepted. However, with the asymmetrical power of the caregiver–care recipient relationship in mind, it seems important that care professionals are conscious and reflective when forming care relationships in order to avoid unwanted consequences. Vik [Citation63] argues that care providers may focus too strongly on ‘filling in’ for lost relationships and thus disregard service recipients’ own social circles or interests, and as a result neglect their possible function of supporting those. As an opposite state of feeling equality and mutuality, being treated as a child or being excessively praised were voiced in the findings. One way of understanding this, may be through a phenomenon called accommodative speech or ‘elderspeak’ [Citation65] in the scientific literature. Elderspeak is well established as both common [Citation66] and resented (by older adults [Citation67]) in eldercare, and is characterized by, for example, simplified wording, changed pitch and inappropriate terms of endearment. To be exaggeratedly praised may be in line with inappropriate terms of endearment. Elderspeak is considered a patronizing and demeaning approach, and a greater emphasis on respectful communication skills has been suggested to address this problem [Citation65]. The concept ‘therapeutic use of self’ [Citation68–70] describes how caregivers can foster therapeutic relationships in a professional way through self-awareness and intentional use of personality, language, perceptions, insights and judgements. Competence development among care workers, focussing on theory and language about professional relationship-building and respectful communication, might increase care workers’ capabilities to reflect, discuss and enhance strategies towards building relationships with mutual characteristics, whilst also being empowering and person-centred [Citation71]. Occupational therapists could increase their reach through sharing competences about the therapeutic use of self through coaching and cooperating with home care workers in order to enhance professional relationship-building that in turn enhances social participation and perceived togetherness. Through involvement in person-centred planning of ‘social stimulation’ content, occupational therapists could also strive towards planned occupations that fit the person’s interests and valued social relationships in order to support both occupational identity and togetherness.

Methodological discussion

To enhance trustworthiness, recommendations from Graneheim and Lundman [Citation42] were followed throughout the research process. The study design, interview technique and analysis were carried out in continuous dialogue between the researchers, and the research procedure is thoroughly described. An observation of an experienced researcher during an interview on a similar topic, as well as a pilot interview for the current study, were conducted to promote a relevant and sensitive interview technique. To ensure anonymity, citations are presented in gender-neutral form without connection to the participant charts. Due to the potentially sensitive interview topics, the interview guide was constructed to begin and end with more positive topics. The small talk after the interview sessions was intentionally used to try to ensure the person felt at ease, and to provide him/her a second opportunity to share lingering thoughts. The results is based on rather a small number of participants as there were some difficulties recruiting older adults willing to participate. Recruitment problems could be due to initially presenting the study as having a focus on loneliness but also through difficulties in mobilizing the home care staff member to forward information letters to potential participants. However, the chosen recruitment procedure, via home care staff, gave us access to the older adults, a frail group that could otherwise be difficult to reach. For future studies, a more effective way could be to cooperate with only a few home care staff members and offer both training and time to introduce and forward the information letter. Those who did participate provided rich accounts. To address the risk of the care providers’ power advantage affecting the older adults’ autonomous choices to participate, home care staff were repeatedly coached to accentuate that participation was optional and of no concern of theirs, when forwarding the information letter. Another limitation was that some participants did not consider themselves as being generally lonely. This, however, brought an opportunity to access valuable narratives about instances of home care support successfully averting loneliness, which deepened understanding of the issues explored. Findings indicated that some participants could experience satisfaction with social conditions and life as a whole despite (unwanted) diminished social participation, and there is still limited knowledge about what differentiates older adults who experience loneliness from those who don’t. As such, further research on both lonely and non-lonely (socially isolated) older adults is recommended. The limited number of men included may have influenced the results. However, there are fewer men than women in this age group in Sweden [Citation72], and all men meeting the criteria and willing to participate were interviewed. As the gender perspective is to a large extent lacking in this study, as well as in others, this would need to be highlighted in future research.

Conclusions

The present study increases understanding of aspects important in social participation among older adults, living with support from home care services. The study highlights the importance of the possibility to maintain one’s sense of personhood throughout occupations done alone as well as together with others. To be in an environment where it is possible to pursue interests and being recognized as a valuable person with relevant needs is possible, was emphasized as adding quality to social participation and decreasing the risk of loneliness. This study expands our understanding of the variety and richness of social participation among home care recipients. The findings may be useful in further research but also for professionals in a home care context, in order to identify and enhance strategies to support social participation among older adults.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the participants for their contributions to the study, and the home care workers for support with recruitment.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- World Health Organization. Ageing: Healthy ageing and functional ability. 2020 [cited 2020 Nov 5]. Available from: https://www.who.int/westernpacific/news/q-a-detail/ageing-healthy-ageing-and-functional-ability

- Levasseur M, Richard L, Gauvin L, et al. Inventory and analysis of definitions of social participation found in the aging literature: proposed taxonomy of social activities. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71:2141–2149.

- Piškur B, Daniëls R, Jongmans MJ, et al. Participation and social participation: are they distinct concepts? Clin Rehabil. 2014;28:211–220.

- Pynnönen K, Rantanen T, Kokko K, et al. Associations between the dimensions of perceived togetherness, loneliness, and depressive symptoms among older Finnish people. Aging Ment Health. 2018;22:1329–1337.

- Nyman A, Josephsson S, Isaksson G. Being part of an enacted togetherness: narratives of elderly people with depression. J Aging Stud. 2012;26:410–418.

- Nyman A, Isaksson G. Enacted togetherness - a concept to understand occupation as socio-culturally situated. Scand J Occup Ther. 2020. DOI:10.1080/11038128.2020.1720283

- Tiikkainen P, Heikkinen RL. Associations between loneliness, depressive symptoms and perceived togetherness in older people. Aging Ment Health. 2005;9:526–534.

- Vozikaki M, Papadaki A, Linardakis M, et al. Loneliness among older European adults: results from the survey of health, aging and retirement in Europe. J Public Health. 2018;26:613–624.

- Vad tycker de äldre om äldreomsorgen? [What do the elderly think of eldercare?] [Internet]. [cited 2020 May 7]. Swedish. Available from: https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/globalassets/sharepoint-dokument/artikelkatalog/ovrigt/2019-9-6349.pdf

- Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Baker M, et al. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2015;10:227–237.

- Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Layton JB. Social relationships and mortality risk: a meta- analytic review (social relationships and mortality). PLoS Med. 2010;7:e1000316.

- Luanaigh CO, Lawlor BA. Loneliness and the health of older people. Int. J. Geriat. Psychiatry. 2008;23:1213–1221.

- Bindels J, Cox K, De La Haye J, et al. Losing connections and receiving support to reconnect: experiences of frail older people within care programmes implemented in primary care settings. Int J Older People Nurs. 2015;10:179–189.

- Kharicha K, Iliffe S, Manthorpe J, et al. What do older people experiencing loneliness think about primary care or community based interventions to reduce loneliness? A qualitative study in England. Health Soc Care Community. 2017;25:1733–1742.

- Levasseur M, St-Cyr Tribble D, Desrosiers J. Meaning of quality of life for older adults: importance of human functioning components. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2009;49:e91–e100.

- Dahlberg L, McKee KJ. Correlates of social and emotional loneliness in older people: evidence from an English community study. Aging Ment Health. 2014;18:504–514.

- Van Baarsen B, Snijders TAB, Smit JH, et al. Lonely but not alone: emotional isolation and social isolation as two distinct dimensions of loneliness in older people. Educ Psychol Meas. 2001;61:119–135.

- Niedzwiedz CL, Richardson EA, Tunstall H, et al. The relationship between wealth and loneliness among older people across Europe: is social participation protective? Pre Med. 2016;91:24–31.

- Andersson L. Loneliness research and interventions: a review of the literature. Aging Ment Health. 1998;2:264–274.

- Douglas H, Georgiou A, Westbrook J. Social participation as an indicator of successful aging: an overview of concepts and their associations with health. Aust Health Rev. 2017;41:455–462.

- Minagawa Y, Saito Y. Active social participation and mortality risk among older people in japan: results from a nationally representative sample. Res Aging. 2015;37:481–499.

- Masi CM, Chen H-Y, Hawkley LC, et al. A meta-analysis of interventions to reduce loneliness. Pers Soc Psychol Rev. 2011;15:219–266.

- Toepoel V. Ageing, leisure, and social connectedness: how could leisure help reduce social isolation of older people? Soc Indic Res. 2013;113:355–372.

- Nilsson I, Häggström Lundevaller E, Fisher A. The relationship between engagement in leisure activities and self-rated health in later life. Act Adapt Aging. 2017;41:175–190.

- Rosso AL, Taylor JA, Tabb LP, et al. Mobility, disability, and social engagement in older adults. J Aging Health. 2013;25:617–637.

- Levasseur M, Gauvin L, Richard L, et al. Associations between perceived proximity to neighborhood resources, disability, and social participation among community-dwelling older adults: results from the VoisiNuAge Study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;92:1979–1986.

- Morley JE. Aging in place. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012;13:489–492.

- Johansson K, Laliberte Rudman D, Mondaca M, et al. Moving beyond ‘aging in place’ to understand migration and aging: place making and the centrality of occupation. J Occup Sci. 2013;20:108–119.

- Abramsson M. Äldres bostadsval och preferenser – en sammanställning av aktuell forskning [Housing choices and preferences of the elderly – a compilation of current research]. Linköping (Sweden): Linköping University; 2015. Swedish.

- Ulmanen P, Szebehely M. From the state to the family or to the market? Consequences of reduced residential eldercare in Sweden. Int J Soc Welf. 2015;24:81–92.

- Statistik om socialtjänstinsatser till äldre 2019 [Statistics on social services for elderly 2019]. [Internet]. [cited 2020 May 7]. Swedish. Available from: https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/globalassets/sharepoint-dokument/artikelkatalog/statistik/2020-4-6745.pdf

- Grundläggande kunskaper hos personal som arbetar i socialtjänstens omsorg om äldre [Basic knowledge among social services staff working in eldercare]. Västerås (Sweden): Socialstyrelsen; 2011.

- Sandberg L, Borell L, Rosenberg L. Risks as dilemmas for home care staff caring for persons with dementia. Aging Ment Health. 2020;1–8. DOI: 10.1080/13607863.2020.1758914.

- Edvardsson D, Sandman PO, Borell L. Implementing national guidelines for person-centered care of people with dementia in residential aged care: effects on perceived person-centeredness, staff strain, and stress of conscience. Int Psychogeriatr. 2014;26:1171–1179.

- Anker-Hansen C, Skovdahl K, McCormack B, et al. Collaboration between home care staff, leaders and care partners of older people with mental health problems: a focus on personhood. Scand J Caring Sci. 2020;34:128–138.

- Socialtjänstlag (2001:453) [Social Services Act] [Internet]. [cited 2020 May 7]. Swedish. Available from: http://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-lagar/dokument/svensk-forfattningssamling/socialtjanstlag-2001453_sfs-2001-453

- Birkeland A, Natvig GK. Elderly living alone and how they experience their social needs are taken care of by home nursing services. Norsk Tidsskrift for Sykepleieforskning. 2008;10:3–14.

- Nilsson I, Luborsky M, Rosenberg L, et al. Perpetuating harms from isolation among older adults with cognitive impairment: observed discrepancies in homecare service documentation, assessment and approval practices. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18:800.

- Turcotte P-L, Larivière N, Desrosiers J, et al. Participation needs of older adults having disabilities and receiving home care: met needs mainly concern daily activities, while unmet needs mostly involve social activities. BMC Geriatr. 2015;15:95.

- Carter RE, Lubinsky J. Rehabilitation research: principles and applications. 5th ed. St. Louis (MO): Elsevier; 2016.

- Kvale S, Brinkmann S, Torhell S-E. Den kvalitativa forskningsintervjun [The qualitative research interview]. 3rd ed. Lund (Switzerland): Studentlitteratur; 2014.

- Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today. 2004;24:105–112.

- Higgs P, Gilleard C. Interrogating personhood and dementia. Aging Ment Health. 2016;20:773–780.

- Giddens A. Modernity and self-identity: self and society in the late modern age. Cambridge (UK): Polity press; 1991.

- Taylor RR, Kielhofner G. Kielhofner’s model of human occupation : theory and application. 5th ed. Philadelphia (PA): Wolters Kluwer; 2017.

- Christiansen C. The 1999 Eleanor Clarke Slagle Lecture. Defining lives: occupation as identity: an essay on competence, coherence, and the creation of meaning. Am J Occup Ther. 1999;53:547–558.

- Asaba E, Jackson J. Social ideologies embedded in everyday life: a narrative analysis about disability, identities, and occupation. J Environ Occup Sci. 2011;18:139–152.

- Johanna CG, Georgina C, Katrina S, et al. Barriers to social participation among lonely older adults: the influence of social fears and identity. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0116664.

- Cg de las H, Geist R, Kielhofner G, et al. Bedömning av viljeuttryck: VQ-S, svensk version (3.1) av the Volitional Questionnaire (VQ), version 4.1 [Evaluation of statements of will: VQ-S, Swedish version (3.1) of the Volitional Questionnaire (VQ), version 4.1]. Nacka (Sweden): Förbundet Sveriges Arbetsterapeuter FSA; 2015.

- Svidén GA, Borell L. Experience of being occupied—some elderly people’s positive experiences of occupations at community-based activity centers. Scand J Occup Ther. 1998;5:133–139.

- Dagverksamhet för personer med demenssjukdom En vägledning [Activity centres for persons with dementia. Guidelines]. Västerås (Sweden): Socialstyrelsen; 2020.

- Nilsson I, Lundgren AS, Liliequist M. Occupational well-being among the very old. J Occup Science. 2012;19:115–126.

- Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Experiences of loneliness among the very old: the Umeå 85+ project. Aging Ment Health. 2010;14:433–438.

- Cardol M, Jong BAD, Ward CD. On autonomy and participation in rehabilitation. Disabil Rehabil. 2002;24:970–974.

- Nolan MR, Davies S, Brown J, et al. Beyond person-centred care: a new vision for gerontological nursing. J Clin Nurs. 2004;13:45–53.

- McCormack B. Negotiating partnerships with older people: a person centred approach. London (UK): Routledge; 2001.

- Collins B. Independence: proposing an initial framework for occupational therapy. Scand J Occup Ther. 2017;24:398–409.

- Wray S. What constitutes agency and empowerment for women in later life? Sociol Rev. 2004;52:22–38.

- Levasseur M, Cohen AA, Dubois M-F, et al. Environmental factors associated with social participation of older adults living in metropolitan, urban, and rural areas: the NuAge Study. Am J Public Health. 2015;105:1718–1725.

- Classen S, Winter S, Lopez EDS. Meta-synthesis of qualitative studies on older driver safety and mobility. OTJR. 2009;29:24–31.

- Wreder M. Time to talk? Reflections on ‘home’, ‘family’, and talking in Swedish elder care. J Aging Stud. 2008;22:239–247.

- Wits AE, Eide AH, Vik K. Professional carers’ perspectives on participation for older adults living in place. Disabil Rehabil. 2011;33:557–568.

- Vik K, Eide AH. The exhausting dilemmas faced by home-care service providers when enhancing participation among older adults receiving home care. Scand J Caring Sci. 2012;26:528–536.

- Gantert TW, McWilliam CL, Ward-Griffin C, et al. The key to me: seniors’ perceptions of relationship-building with in-home service providers. Can J Aging. 2008;27:23–34.

- Brown A, Draper P. Accommodative speech and terms of endearment: elements of a language mode often experienced by older adults. J Adv Nurs. 2003;41:15–21.

- Samuelsson C, Adolfsson E, Persson H. The use and characteristics of elderspeak in Swedish geriatric institutions. Clin Linguist Phon. 2013;27:616–631.

- Hehman JA, Bugental DB. Responses to patronizing communication and factors that attenuate those responses. Psychol Aging. 2015;30:552–560.

- Freshwater D. Therapeutic nursing improving patient care through self-awareness and reflection. London (UK): SAGE; 2002.

- Solman B, Clouston T. Occupational therapy and the therapeutic use of self. Br J Occup Ther. 2016;79:514–516.

- Taylor RR. The intentional relationship: occupational therapy and use of self. 2nd ed. Philadelphia (PA): F.A. Davis Company; 2020.

- McCormack B. Person-centredness in gerontological nursing: an overview of the literature. J Clin Nurs. 2004;13:31–38.

- Sveriges befolkningspyramid [Sweden’s population pyramid] [Internet]. [cited 2020 May 7]. Swedish. Available from: https://www.scb.se/hitta-statistik/sverige-i-siffror/manniskorna-i-sverige/sveriges-befolkningspyramid/

- Institute K. Research programme future care - for older adults in home care and care home | NVS 2018 04 10; [cited 2019 Feb 20]. Available from: https://ki.se/en/nvs/research-programme-future-care-for-older-adults-in-home-care-and-care-home-nvs