Abstract

Background

Stress-related disorders cause suffering and difficulties in managing occupations and relationships in everyday life. A previous study of women with stress-related disorders, who photographed well-being and talked about the photographs in interviews, showed that moments of well-being still exist but further knowledge is needed about their perceptions of participating in such a study.

Aim

To describe how people with stress-related disorders experience taking photographs related to well-being in everyday life and reflecting on and talking about these photographs.

Material and methods

Twelve women, 27–54 years with stress-related disorders were recruited from primary healthcare centres. They participated in interviews based on the photographs and qualitative content analysis was used.

Results

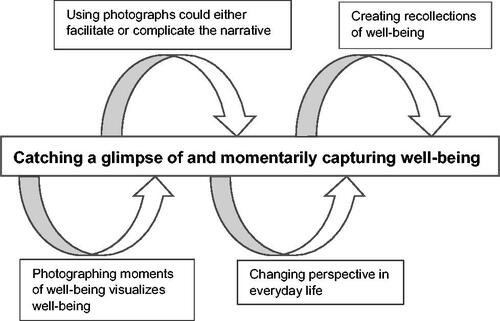

One theme ‘catching a glimpse of and momentarily capturing well-being’ and four categories were identified: ‘Photographing moments of well-being visualizes well-being’, ‘Using photographs could either facilitate or complicate the narrative’, ‘Changing perspective in everyday life’ and ‘Creating recollections of well-being’.

Conclusions and significance

Introducing a focus on well-being in everyday life despite living with a stress-related disorder might contribute a valuable complement to stress rehabilitation for occupational therapists and other health professionals. Using photographs as a basis for reflections about everyday life and health/well-being also seems positive for this group.

Introduction

Stress-related disorders are increasing in all age groups, and are more common among women [Citation1,Citation2]. They constitute a major public health problem due to suffering experienced by the individual and their relatives as well as the major costs for society in terms of healthcare and rehabilitation [Citation3]. Living with a stress-related disorder entails subjective distress related to mental well-being [Citation4] such as emotional disturbance, difficulties in managing occupations in everyday life and in social interactions [Citation5]. Meaningful occupations have shown to be of importance for recovering from mental illness, and have also shown to be closely related to well-being [Citation6–8]. Health can be understood as well-being and the quality to be able to do what is valuable in life. It is important to focus on a person’s existential vitality, his/her vigour, love of life and courage to carry out life projects, whether major or minor, in order to promote health processes in everyday life. It is also important to shed light on a person’s life rhythm in his/her life situation, which includes both opportunities for movement and stillness and an interaction between these. In order to support health, the most important is to find the person where he/she is and start from there [Citation9,Citation10].

A recently published study [Citation11] focussed on what well-being means in everyday life, despite living with stress-related disorders. The results of that study showed that situations of unconditional beingness could contribute to wellbeing. It was important to find the energy and the tools to balance everyday life as well as to find supportive environments. The data was collected by combining interviews with photographs taken by the participants on moments in everyday life that illustrated wellbeing [Citation11]. The present study focuses on the participants’ experiences of taking photographs of well-being and talking about them in an interview. These experiences can help to gain a greater understanding of whether the combination of visual tools and talking may be supportive in capturing well-being for individuals with stress-related disorders. Such knowledge can be useful for forthcoming research and developing health-promoting interventions, and is also in line with Hammell [Citation8], who emphasised the importance of focussing on well-being in occupational therapy.

Early identification of stress-related disorders has shown to be of importance for their treatment [Citation12], and a number of rehabilitation methodologies have been promoted [Citation13–15]. Most of these focus on psychological symptoms, e.g. [Citation16] in order to reduce stress, but have so far only generated marginal outcomes [Citation17]. There is not only a need for treatments for reducing psychological symptoms, but also for health promotion interventions for enabling individuals to improve their health and well-being [Citation18]. Research has shown that it is important for recovery from stress-related disorders to initially have time for rest, sleep and support from others, prior to gradually [Citation19] engaging in self-elected occupations [Citation20–22], including energy-consuming, recreational [Citation22,Citation23], and creative activities [Citation23]. What this actually entails for each individual in his/her everyday life may, however, differ and can include subjective elements that health professionals need to have greater knowledge of.

Such subjective elements, containing moments of well-being, still existed when living with a stress-related disorder, according to the participants in the recent study by Hörberg et al. [Citation11]. Visual research methodology [Citation24] was used for the data collection in that study, where the participants took photographs of objects that represented well-being for them and then reflected on these. Photo elicitation entails using photographs as images to attain a greater depth in an interview in order to generate data and enhance knowledge [Citation24]. Images can provide a different type of information than that found in verbal communication alone and can thus increase the possibilities for empirical research. Visual research methodologies are considered useful in occupational therapy [Citation25] and suitable for exploring and understanding complex phenomena in everyday life [Citation26,Citation27], such as well-being. Photography based on what the photographer him/herself perceives as containing meaning in everyday life [Citation24,Citation28,Citation29], has also been considered to be well aligned with the basic assumptions of client-centred occupational therapy [Citation30] as the individual is active with taking pictures of his/her own preferences.

Furthermore, a review [Citation31] of qualitative studies using Photovoice to describe experiences of participants living with mental illness, indicated that the methodology promotes the participants’ conversations. Photography and the use of photographs as a basis for reflection thus appears to be suitable for encouraging people to talk and for gaining information about people with stress-related disorders [Citation11].

We have not found any studies, other than the one by Hörberg et al. [Citation11], where photographs taken by participants have been used as support for interviews about well-being in everyday life when living with stress-related disorders. Knowledge about how the participants experienced taking photographs of objects representing elements of their well-being can be of importance in forthcoming interventions using photographs as a complement to regular treatment. How to use photographs in clinical practice can also be important for occupational therapists in the assessment, treatment and rehabilitation of clients in a client-centred context. This is important due to the need for further knowledge about what support these people need, in order to enable their recovery in everyday life [Citation32]. The aim of the present study was thus to describe how people with stress-related disorders experience taking photographs related to their well-being and, based on these photographs, reflect and talk about well-being in everyday life.

Material and methods

The present study had a qualitative design and is part of the project ‘Finding viability in daily life, experiences of well-being despite stress-related illness’ [Citation11]. The data collection comprised photographs and individual interviews, where the photographs constituted a starting point for the interview. Only data from the interviews were analysed in the present study.

Participants

The participants were clients from three primary healthcare centres in the south of Sweden. The inclusion criteria were: aged between 25 and 65 years and diagnosed with stress-related disorders (ICD-10 F43.8, i.e. other reactions to severe stress or F43.9, i.e. reaction to severe stress, unspecified) [Citation33]. The exclusion criteria were severe somatic disease, neuropsychiatric diagnosis or psychotic disorders, linguistic difficulties and/or cognitive impairments that hindered comprehension and participating in the project.

Clients meeting the criteria were consecutively informed about the present study by their regular therapist, who acted as gate-keepers. The therapists were occupational therapists, psychologists, nurses and social workers. The clients who were interested in taking part were then contacted by one of the authors (ABG or UH). A total of 14 people were interested, two of these (one woman and one man) only participated in the information meeting prior to the interviews. Twelve people were thus interviewed. The participants were all female and were between 27 and 54 years old and most were on sick leave ().

Table 1. Characteristics of the participants (n = 12).

Data collection

Two of the authors (ABG or UH) performed the interviews. They met each participant twice individually; first at an information meeting and then when conducting the interview based on photographs (held between September 2017 and January 2018).

The participants received written and oral information about the aim of the study, the right to withdraw, and confidentiality at the first meeting. They also had the opportunity to ask any questions. They then signed a written informed consent and background data were collected. They also chose the time and place for the interview, which was held within 2 weeks. The participants were finally informed to take photographs with their mobile phones of situations, settings and/or places where they experienced well-being and that 1–4 of these photographs would be the basis for the interview. The participants e-mailed the selected photographs prior to the interview and each image was thereafter enlarged and printed on paper in A4 format.

The enlarged photographs were placed on a table in front of the participant and the interviewer during the interviews. The participant was encouraged to talk about the photographs and describe their experiences of well-being related to these images. The part of the interview focussing on the participants’ experiences of this procedure took place at the end of the interview. Examples of questions were: ‘How did you experience taking photographs?’, ‘What was it like to share and talk about the photographs?’ Follow-up questions, e.g. ‘Can you give me an example’ or ‘Can you tell me more about this’ were used as well.

Data analysis

The audio-recorded interviews were transcribed verbatim and analysed with qualitative content analysis [Citation34]. In order to strengthen trustworthiness during the analysis process, the research group members’ preunderstanding was taken into consideration by using critical reflection and a slowing down of the process of understanding. The researchers vary both in terms of professional background and experience of the target group and of qualitative research. Furthermore, two of the authors performed the interviews and thus had an inside perspective regarding data collection, while the other two authors, who had not collected the data had an outside perspective. The transcribed interviews were read several times to achieve an overall understanding of the data. The analysis process included identifying and underlining the meaning units related to the aim of the study, followed by condensing and abstracting meaning units into codes. Similarities and differences that guided the organisation of categories were then recognised on a descriptive level. Finally, a theme, which was as the common thread including the various categories was identified. An iterative process was used, and the focus switched between the whole and the parts of the data during the analysis [Citation34]. The emerging theme and categories were discussed within the research group until consensus was reached.

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Linköping, Sweden (Dnr 2017/284-31) and conducted in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki [Citation35]. Participating in a research study might, for people living with stress-related disorders, include a risk of not acknowledging the need for a pause and rest, or discontinuing their participation. The voluntary nature of participation in the study was highlighted, and the opportunity to withdraw at any time and without any explanation was thus emphasised in order to minimise this risk.

Results

Catching a glimpse of and momentarily capturing well-being

One theme ‘catching a glimpse of and momentarily capturing well-being’ was identified. The theme expresses how photographing well-being in everyday life and then talking about well-being based on the photographs started a process of helping the participants become attentive to and recognise their well-being. Furthermore, the photographs were experienced as memories enabling the participants to recollect those moments of well-being by just looking at the photograph. This process revealed four categories: ‘Photographing moments of well-being visualizes well-being’, ‘Using photographs could either facilitate or complicate the narrative’, ‘Changing perspective in everyday life’ and ‘Creating recollections of well-being’ ().

Photographing moments of well-being visualises well-being

The participants spoke of it being fun to take photographs. The photographing per se enhanced a feeling of well-being, and was easy to do as the camera was always accessible in their mobile phones. It could vary as to how easy they found the right motif illustrating well-being to bring to the interview. Some of them had many motifs to choose between while others had to reflect on what supported their well-being prior to selecting their motifs.

The choice of motif was sometimes described as being related to their mental health condition and could thus change when the condition changed, such as when being depressed and having difficulties in coping with everyday life. The kind of motif the participants chose could also vary and depend on different circumstances, such as the season of the year. Most of the chosen photographs were taken during the autumn or winter, i.e. when the interviews took part. Considering if the project had been carried out in summertime, one of the participants said: ‘I would perhaps have changed this [photograph] for a lake. A picture of a lake or when the sun is shining on the lake or something’ [P7].

The participants described that having the printed photographs in front of them during the interview visualised the situations, which had previously given them well-being. They also talked of having received insights and discovering common themes that were evident in their photographs ‘I realize that these photos are taken outside. And I feel great when I’m out but it’s seldom I go out. So, I really should go out more than I do’ [P8].

Looking at and reflecting on the photographs helped the participants’ feelings and thoughts to be more explicit. They realised things they had not thought about before, or something suddenly became obvious to them.

Somehow, I feel that the photo is telling me something. The picture I take, if I look at it, I get thoughts and feelings. That I wouldn’t have got, I believe, if I hadn’t taken that picture and looked at this specific photo [P1].

Using photographs could either facilitate or complicate the narrative

The photographs were described as aiding the conversation during the interview. The photographs facilitated the narrative in the interview and were also considered as helping to create a clearer presentation for the listener, which could be expressed as ‘this [talking with the photograph as the starter] is easier for me than just sitting and explaining. I feel that it’s also easier for you (the interviewer) to understand as well’ [P2].

However, having the starting point in the photographs both facilitated and complicated the explanation of their experiences of well-being. On the one hand, it was perceived as easier to put words on emotions while having a photograph in front of them, as this made it possible to be connected with feelings that are seldom expressed but ‘just exist’. On the other hand, the participants said that it was difficult to talk about how the photographs described well-being. Some motifs were easier to describe, for example, those that depicted physical satisfaction, e.g. yoga or training their pet, while other motifs were more difficult to explain, which could be expressed as:

It’s just an essential feeling that just is, so, I’ve struggled a bit to find what it is because this is something that comes from deep down inside me, so I’ve struggled a little to put words on it or be able to describe it with thoughts or so [P8].

Changing perspective in everyday life

The participants stated that the focus on well-being contributed to gaining a positive perspective, which can be strengthening regardless of how they feel or where they are in their rehabilitation process. This changed perspective in how they looked upon their daily lives helped them to be more able to be aware of and notice that there were actually positive moments, which could be useful for them in the future.

Well, you just sort of capture [well-being] in the moment and think that ‘well I’ll enjoy it right now’. I think I’ve been good at this or at least better than I was before, a way of pausing one more time [P9].

The participants described a new and increased focus on well-being as they had previously been more focussed on what was not functioning and situations that caused stress, such as in the meetings with health professionals as well as with their relatives. However, the participants also perceived a need to continue training in viewing their everyday life from this positive perspective, as well as to continue practising to use this perspective in different life situations.

Even if you are not that focused on it [well-being] from the very beginning, it reinforces the whole concept with that, yes, this with the well-being/…/one focuses more and it gets a greater significance than it might have had before [P10].

Furthermore, the participants described that by focussing on well-being, they found out what it means to them. Advice they had previously received from healthcare professionals had sometimes been more general and not considered particularly suitable ‘well well-being is [said to be] going out and walking in the forest, but if you’re not that type of person, you can’t force yourself to do something you don’t enjoy doing’ [P5].

Finding answers to questions in the interview, such as reflecting on what harmony and joy can be about, and how this can be linked to one’s own well-being was perceived as something self-discovering.

Moreover, the focus on well-being helped the participants to re-prioritize and change perspective concerning their occupations in everyday life. Sometimes this happened almost directly after being included in this project. For example, the information letter they received together with the informant consent stimulated them to reflect about well-being. This resulted in a decision, for example, to write a list that clarified what contributed to their health and what decreased their energy and put this on the refrigerator. This could also entail concrete changes in their communication with their family members. By communicating their needs and desires, their relatives could better understand their needs for recovery, such as spending time on their own yoga practice or reading a book. They also reflected on the importance of setting aside time to engage in occupations that could lead to increased well-being although sometimes not having the drive or strength.

Perhaps, I need to pull myself together and program myself to take care of my flowers or go out in the garden. And just do it and not continue to think that I’ve got no strength or that it gives me stress, because I feel good when I get out into the garden [P5].

The participants expressed that they had to be able to do whatever generated well-being, without getting feelings of guilt. For example, it was said that it ought to be the opposite, i.e. that one should be guilty when not being involved in occupations that lead to well-being, with the argument that it would otherwise not be tenable in the long run.

Finally, the conversation concerning the motifs from the photographs and well-being in everyday life during the interview was considered to be rewarding and confirmative. Some of the participants expressed that they felt secure during the interview and thus dared to open up and to speak freely and that it also generated new insights and perspectives ‘it [the interview] gives me something to sit here just you and me and talk about this. It gets my thoughts going’ [P1].

Creating recollections of well-being

The participants perceived satisfaction when looking at the enlarged photographs as well as being given the opportunity to take them home after the interview. The photographs were said to be memories enabling them to relive those moments of well-being just by looking at the photograph. Pleasurable feelings, such as happiness, longing and hope for the future, were described as well as safety, serenity and peace of mind.

The participants perceived a need for visualising some specific motifs in their everyday life, after the interview. They expressed a desire to hang up the photographs at home, and some also wanted to frame them. Hanging them at home was seen as a possibility for even more recollection about what well-being means to them, and sharing this with their relatives was seen as a possibility to communicate moments that they had enjoyed. By continuing to look at the photographs, the participants meant that they could be reminded of what they need to continue to work on in order to experience well-being in their future everyday life. ‘It’s a reminder of everyday life, that I, maybe when I’m up here and it’s chaotic in my head, I can still focus on the way to [well-being] and to get there’ [P11].

Discussion

This qualitative study aimed at describing the experiences of people with stress-related disorders taking photographs of well-being and talking about their well-being in everyday life based on these photographs. The results showed that the participants emphasised that the procedure encouraged them to reflect on their everyday life, change perspective and catch sight of their well-being. They experienced a change in focus from obstacles to being able to recognise and create recollections of positive situations and pay attention to moments in everyday life where they experienced well-being.

Although it should be recognised that the present study was not intended to be a therapeutic intervention, the opportunity to experience a changed perspective has been identified in relation to some interventions. The tree theme method (TTM) [Citation36] is an example of this where painted images are literally rotated and viewed from different angles throughout the sessions in order to support the client to see things from more than one perspective.

Furthermore, a changed perspective was also perceived by participants with stress-related disorders [Citation37], who took part in an anti-stress intervention based on complementary and alternative medicine. Those participants perceived exercises and dialogues with the therapist and other group participants as opportunities to recognise what they needed to change in their everyday lives.

The results in the present study indicate that the introduction of a focus on well-being, in this case by participating in a project, might be beneficial for catching a glimpse of well-being and capturing it momentarily. This entailed the participants reflecting on what contributes to their well-being, which could be something different to that described in the general advice, such as sleep hygiene and physical activity, which they had previously received within primary health care. The new insights that the participants described as having gained from the photographs concur with the participants’ descriptions of using the photographs as memories and reminders in previous research [Citation27].

Moreover, the participants stated that basing the conversation on the photographs made it easier to communicate and explain to the interviewer. This is in line with Glaw et al. [Citation24], who stated that photographs can facilitate and deepen an interview, when the reflection is based on an image, as the image can be understood by both participant and interviewer. The participants in the present study also described the interview and conversation based on photographs as a safe space and that the focus on well-being helped them to be aware of what contributed to their well-being in everyday life. Both these aspects are comparable to the findings among the participants participating in the TTM intervention [Citation36]. They are also similar to the outcomes of a gardening program for people with stress-related disorders, where the participating women described that the safe environment and enjoyable occupations contributed to adding more enjoyable occupations in their everyday life [Citation20,Citation23]. The use of creative activities in the latter study [Citation19] was perceived as helpful for reconnecting with previous memories of a former healthy self, and previously enjoyable occupations, which is in line with findings from the present study.

The present study differs, however, from these three aforementioned studies [Citation20,Citation23,Citation36] as photographs are used in the present study as a basis for the interviews, and not as a part of a rehabilitation program. However, the participants in the present study appreciated taking photographs and participating in the project per se. This is similar to previous findings in studies with participants with cancer where they had enjoyed taking photographs and the majority had also found talking with the researcher as helpful [Citation38]. Comparable findings can also be found in a study in which female survivors of sexual violence described the method as being promotive in itself [Citation27].

However, Glaw et al. [Citation24] maintained that visual methodology does not only include photography, but also creative activities, such as painting and artwork. The results from the present study can also be related to the steps in a creative process [Citation39]: preparation (when the individual gets knowledge about the problem), incubation (when the individual works subconsciously on a problem), illumination (when the individual gets an aha-experience how to solve a problem), and verification (when the individual tests their newly created idea). This thus indicates the potential of initiating a process of becoming conscious of and recognising aspects of one’s well-being, when taking photographs of well-being and talking about it as part of the rehabilitation for this group.

We recognise that the data collection may have had a therapeutic effect, even though the participant was aware that she participated in interviews as part of a research project and not in any treatment. The participation did not, however, arouse any negative emotions, but rather positive ones instead. Although the potentially therapeutic effect may be considered an issue from a methodological perspective, it also indicates that photographing well-being, reflecting and talking about the photographs could be developed into an intervention, which is in line with the views of Dahlberg et al. [Citation9] on the promotion of health processes.

This is further supported by the fact that our participants emphasised the need for training in this new perspective and described not having received it in their previous healthcare. Adding this perspective can thus be a positive complement to current rehabilitation methods for people with stress-related disorders, although further research is needed to determine to whom and when it is most beneficial so that it is introduced at a favourable time and in a positive manner.

Furthermore, freely engaging in and making meaning of everyday occupations is, according to Sutton et al. [Citation6], essential in occupational therapy practice and photographing well-being could potentially be one way of doing this. Our previous study in this project [Citation11] concluded that it is possible to experience well-being despite living with a stress-related disorder. The present study adds important information that this well-being has not been fully recognised by the participants themselves. The importance of taking photographs and of using them for reflecting on well-being needs further exploration and research. Similarly, investigations focussing on the content in the photographs taken and about which kind of occupation that reflects well-being in this group would be valuable together with further exploration about the meaning of these occupations.

Empirical studies are thus needed in order to gain further knowledge about how the taking of photographs and talking about them can have a health-promoting effect. Therefore, based on the results of the present study and the earlier study in this project by Hörberg et al. [Citation11], an intervention has been developed and is currently being investigated in a feasibility study, which includes an intervention group as well as a control group.

Methodological considerations

The trustworthiness [Citation34,Citation40] of the present study, based on its strengths as well as limitations, is necessary to recognise. The credibility was strengthened by using a qualitative design [Citation34] as this was well suited for addressing the aim of the study. Furthermore, credibility was strengthened by a detailed description of the data collection and analysis, and the results were confirmed by quotations. To further strengthen the credibility, participants with personal experience of stress-related disorders who wanted to take photographs and reflect on their experiences of well-being were recruited. This can be seen as a strength as the participants are representative of those with the best experience of the focus in the study.

The dependability was strengthened by reflecting upon the authors’ pre-understanding, i.e. that the research group had experiences of clients with mental illnesses within caring sciences and occupational science, as well of qualitative research. The analysis was continuously discussed between the authors, until consensus was reached. The dependability could have been further strengthened if some of the participants had also been included in member cheques. The importance of recognising the photographers’ rationale behind the photographs [Citation24] has been emphasised.

A limitation is that we do not know how many clients declined to participate as the gate-keepers forgot to note this information. On request the gate-keepers stated that most of those who were contacted agreed to participate.

The description of the participants, as well as the context, may help the reader to reflect on the transferability to similar groups of participants and contexts. The transferability is, however, limited due to only women participating as the one man available for recruitment to the study did not continue after receiving the information. Stress-related disorders are more common in women than men, which is reflected in the female gender domination in the study [Citation41], however, including men would most likely have contributed to a greater variation. On the other hand, our results might also be applicable to men.

Conclusion

Using photographs as a starting point for talking and reflecting about everyday life and health/well-being appears to be positive for this group. Introducing the focus on well-being in everyday life in spite of living with a stress-related disorder might constitute a valuable complement to stress rehabilitation programs and be useful for occupational therapists and other health professionals working with people suffering from stress-related disorders or at risk for this. However, further research is necessary for investigating how and when this should be conducted as well as research regarding its potential effects. Similarly, further exploration of the kinds of occupation conducted in relation to well-being and their meaning is needed.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Försäkringskassan [Swedish Social Insurance Agency]. Psykisk ohälsa. Sjukskrivning för reaktioner på svår stress ökar mest. [Mental illness. Sick-leave due to reactions on severe stress increases the most]. Försäkringskassan [Swedish Social Insurance Agency]; 2016.

- OECD. Mental health. [cited 2021 Jan 25]. https://www.oecd.org/els/health-systems/mental-health.htm.

- Folkhälsomyndigheten [Publich Health Agency of Sweden]. Folkhälsans utveckling - årsrapport 2018 [The development of public health -yearly report 2018]. 2018.

- World Health Organization. Mental health: a state of well-being. Geneve: World Health Organization; 2017. https://www.who.int/features/factfiles/mental_health/en/.

- World Health Organization. International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems. 10th revision. Geneve: World Health Organization; 2016.

- Sutton DJ, Hocking CS, Smythe LA. A phenomenological study of occupational engagement in recovery from mental illness. Can J Occup Ther. 2012;79(3):142–150.

- Wilcock AA, Hocking C. An occupational perspective of health. 3rd ed. Thorofare (NJ): Slack Incorporated; 2015.

- Hammell KW. Opportunities for well-being: the right to occupational engagement. Can J Occup Ther. 2017;84(4–5):209–222.

- Dahlberg K, Todres L, Galvin KT. Lifeworld-led healthcare is more than patient-led care: an existential view of well-being. Med Health Care Philos. 2009;12(3):265–271.

- Dahlberg K. Lifeworld phenomenology for caring and for health care research. In: Thomson G, Dykes F, Downe S, editors. Qualitative research in midwifery and childbirth, phenomenological approaches. London: Routledge; 2011.

- Hörberg U, Wagman P, Gunnarsson AB. Women’s lived experience of well-being in everyday life when living with a stress-related illness. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-Being. 2020;15(1):1754087.

- Holmgren K, Sandheimer C, Mardby A-C, et al. Early identification in primary health care of people at risk for sick leave due to work-related stress - study protocol of a randomized controlled trial (RCT). BMC Public Health. 2016;16(1):1193.

- Grahn P, Pálsdóttir AM, Ottosson J, et al. Longer nature-based rehabilitation may contribute to a faster return to work in patients with reactions to severe stress and/or depression. IJERPH. 2017;14(11):1310.

- Wallensten J, Åsberg M, Wiklander M, et al. Role of rehabilitation in chronic stress-induced exhaustion disorder: a narrative review. J Rehabil Med. 2019;51(5):331–342.

- Hitchcock C, Werner-Seidler A, Blackwell SE, et al. Autobiographical episodic memory-based training for the treatment of mood, anxiety and stress-related disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2017;52:92–107.

- Salomonsson S, Santoft F, Lindsäter E, et al. Effects of cognitive behavioural therapy and return-to-work intervention for patients on sick leave due to stress-related disorders: Results from a randomized trial. Scand J Psychol. 2020;61(2):281–289.

- Perski O, Grossi G, Perski A, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of tertiary interventions in clinical burnout. Scand J Psychol. 2017;58(6):551–561.

- World Health Organization. Ottawa charter for health promotion: first international conference on health promotion; 1986 [cited 2021 Jan 25]. http://www.who.int/healthpromotion/conferences/previous/ottawa/en/.

- Perski A. Rehabilitering av stressjukdomar sker i olika faser och blir ofta lång. Läkartidningen. 2004;101:1292–1294.

- Eriksson T, Westerberg Y, Jonsson H. Experiences of women with stress-related ill health in a therapeutic gardening program. Can J Occup Ther. 2011;78(5):273–281.

- Håkansson C, Dahlin-Ivanoff S, Sonn U. Achieving balance in everyday life. J Occup Sci. 2006;13(1):74–82.

- Johansson G, Eklund M, Erlandsson LK. Everyday hassles and uplifts among women on long-term sick-leave due to stress-related disorders. Scand J Occup Ther. 2012;19(3):239–248.

- Hellman T, Jonsson H, Johansson U, et al. Connecting rehabilitation and everyday life-the lived experiences among women with stress-related ill health. Disabil Rehabil. 2013;35(21):1790–1797.

- Glaw X, Inder K, Kable A, et al. Visual methodologies in qualitative research: autophotography and photo elicitation applied to mental health research. Int J Qual Methods. 2017;16(1):160940691774821.

- Asaba E, Rudman LD, Mondaca M, et al. Visual methods: a focus on photovoice. In: Nayar S, Stanley M, editors. Qualitative research methods in occupational science and occupational therapy. London: Routledge; 2014.

- Asaba E, Rudman LD, Mondaca M, et al. Visual methodologies: photovoice in focus. In: Nayar S, Stanley M, editors. Qualitative research methodologies for occupational science and therapy. London: Routledge; 2014.

- Sinko L, Munro-Kramer M, Conley T, et al. Healing is not linear: using photography to describe day-to-day healing journeys of undergraduate women survivors of sexual violence. J Community Psychol. 2020;48(3):658–617.

- Wang C, Burris M. Photovoice: Concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Educ Behav. 1997;24(3):369–387.

- Hansen‐Ketchum P, Myrick F. Photo methods for qualitative research in nursing: an ontological and epistemological perspective. Nurs Philos. 2008;9(3):205–213.

- Townsend EA, Polatajko HJ. Enabling occupation II: advancing an occupational therapy vision for health, well-being & justice through occupation. Ottawa (ON): CAOT Publications ACE; 2007.

- Han CS, Oliffe JL. Photovoice in mental illness research: a review and recommendations. Health (London). 2016;20(2):110–126.

- Försäkringskassan [Swedish Social Insurance Agency]. Psykiatriska diagnoser. Lång väg tillbaka till arbete efter sjukskrivning. [Psychiatric diagnoses. Long way back to work after sick leave]. Försäkringskassan [Swedish Social Insurance Agency]; 2017.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5). 5th ed. Washington (DC): APA; 2013.

- Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today. 2004;24(2):105–112.

- Helsinki Declaration. World medical association declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects; 2013 [cited 2020 Dec 22]. http://www.wma.net/en/30publications/10policies/b3/.

- Gunnarsson A, Peterson K, Leufstadius C, et al. Client perceptions of the tree theme method™: a structured intervention based on storytelling and creative activities. Scand J Occup Ther. 2010;17(3):200–208.

- Arvidsdotter T, Kylén S, Bäck-Pettersson S. Experiences of living with stress-related exhaustion disorder and participating in a tailor-made antistress program in primary care. PSYCH. 2019;10(11):1463–1484.

- Balmer C, Griffiths F, Dunn J. A review of the issues and challenges involved in using participant-produced photographs in nursing research. J Adv Nurs. 2015;71(7):1726–1737.

- Sadler-Smith E. Wallas’ four-stage model of the creative process: more than meets the eye? Creat Res J. 2015;27(4):342–352.

- Graneheim UH, Lindgren B-M, Lundman B. Methodological challenges in qualitative content analysis: a discussion paper. Nurse Educ Today. 2017;56:29–34.

- Swedish Agency for Health Tecnology Assessment and Assessment of Social Services. Behandling av stressrelaterade sjukdomar med fokus på maladaptiv stressreaktion och utmattningssyndrom [Treatment of stress-related disorders with focus on maladaptive stress reaction and exhaustion syndrome]. Stockholm: Swedish Agency for Health Tecnology Assessment and Assessment of Social Services; 2015.