Abstract

Background

The concept of occupational identity has become an important focus within occupational science and occupational therapy, drawing both recognition and inquiry. Even if the concept is highly relevant for understanding the occupational nature of human beings, ambiguity regarding the identification and application of occupational identity exists.

Aim

This analysis aimed to clarify the concept of occupational identity by examining its current use and application within occupational therapy.

Materials and methods

Walker and Avant’s method for concept analysis was utilized to clarify the concept of occupational identity.

Results

Analysis resulted in three distinct categories of use: occupational identity construction, occupational identity discrepancy and occupational identity disruption, described contextually in terms of the self being, the self being and doing, and the self being and doing with others.

Conclusions

Findings validated the significant connection between occupation and identity through doing, being and future becoming. Also uncovered were considerable connections to belonging.

Significance

Occupational identity encompassed complex connections comprising both individual and collective components. Personally meaningful expression and connection were of particular significance to occupational identity as discrepancies or disruption of meaningful connections had negative implications for occupational engagement.

Introduction

A relationship exists between what people do and who they perceive themselves to be [Citation1]. Occupation encompasses all that people do, so much so that it is theorized that life extends through time and place by means of occupation [Citation2]. Occupations are thought to express the known self, one’s identity, and create personal meaning [Citation1,Citation3,Citation4]. Quality of life relates directly to one’s capacity to engage as an occupational being who holds and seeks meaning, worth and place [Citation5]. As such, while a life can be viewed in relation to personal engagement in occupation, so can occupation be seen as an agent through which identity is constructed [Citation2,Citation6,Citation7]. The link between occupation and identity is so consequential that an inability to engage in meaningful occupation can threaten identity; similarly, occupation is a means to rebuild one’s identity [Citation1,Citation8]. While Christiansen [Citation3] spoke in terms of occupation as identity, Kielhofner is said to have coined the term occupational identity [Citation4]. Essentially, this term fuses the distinct concepts of occupation and identity, emphasizing the asserted connection between the two.

The concept of identity from the perspective of psychology and sociology is varied and complex. Identity relates to self-perception encompassing personal aspects unique to an individual and social aspects acquired from engagement in society [Citation9]. The self-perceptions comprising identity are active in shaping and affecting behaviour [Citation10]. Individual behaviour or action is determined by a merging of the personal and social aspects of identity as well as the contextual demands of a situation [Citation11]. A link between identity and behaviours expressed or actions taken is proposed. From an occupational perspective, this proposed link is between identity and occupation.

Occupational identity (OI) has since its inception become a central concept in understanding the occupational nature of human beings [Citation12] and, thus, a critical focus within occupational science and occupational therapy (OT). For instance, occupational therapists have examined how OI relates to: education [Citation13], human experience [Citation8,Citation14–16] health conditions [Citation6,Citation17], and also OI’s disruption and subsequent reconstruction after a crisis or the onset of disability [Citation18,Citation19].

Despite substantial investigation, OI is still in an incipient stage with vital aspects in need of further development and reformulation [Citation4,Citation12]. OI has been utilized in OT literature without explanation and when defined, variations in its characterization exist [Citation12,Citation20–22], implying disagreement regarding what OI means and just what it entails. Inconsistencies contribute to ambiguity regarding OI’s identification and application. Clarity of use and meaning is critical to knowing what phenomena one is influencing or investigating [Citation23]. Moreover, there has been critique of OI being too oriented on the individual without adequately reflecting surrounding socio-cultural perspectives [Citation4,Citation24]. Uncertainties concerning OI’s defining aspects indicate a need for conceptual clarification and refinement. This is particularly true given the pivotal link between occupation and identity over one’s lifetime and its consequent relevance within OT.

A concept is a mental representation of a thing or action that imparts meaning; it is dynamic and its strength depends on clearly naming and defining what it represents [Citation23]. Concept analysis enables comprehensive clarification of concepts through examination and description [Citation23]. Ideally, analysis will ‘capture the critical elements of it at the current moment in time’ [Citation23, p. 158]. Thus, identifying antecedents, attributes and consequences inherent to OI, as currently used and experienced, would promote greater understanding. ‘Understanding the meanings, experiences, and contextual dimensions of occupation’ is of critical importance to occupational therapists [Citation25, p. 4]. Furthermore, conceptual clarity could enhance research and application of OI within occupational science and OT practice.

Thus, the aim of this analysis is to clarify the concept of occupational identity by examining its current use and application within occupational therapy.

Materials and methods

Although different methods of content analysis exist, Walker and Avant’s [Citation23] method for concept analysis will guide this examination of occupational identity within OT.

Walker and Avant’s method is an acknowledged approach offering a clearly outlined procedure that facilitates a ‘careful examination and description of a word or term’ [Citation23, p. 158]. Walker and Avant’s [Citation23] eight-step method involves the iterative completion of the following:

Selecting a concept.

Determining the aim or purpose of analysis.

Identifying all forms of concept usage.

Determining the concept’s defining attributes.

Identifying a model case.

Identifying additional cases.

Identifying antecedents and consequences.

Defining empirical referents.

Steps 1 and 2: selecting a concept and determining the aim or purpose of analysis

The first two steps of this process were addressed in the introduction. The concept for analysis is occupational identity and the aim is to clarify its use and application.

Preparation for step 3: identifying all forms of concept usage

To identify concept usage, one must first determine the data to be collected and considered for inclusion. When analyzing theoretical concepts ‘the relevant evidence must be restricted to scientific literature’ [Citation26, p. 688]. From this perspective, data were obtained from peer-reviewed, scientific journals, ensuring the quality of the journal articles used and enhancing overall credibility. Although Walker and Avant [Citation23] recommend using lay literature, this would be unproductive as ‘occupational’ is often linked to vocation, as seen in the following definition ‘relating to a person’s job or profession’ [Citation27]. The search was, therefore, confined to scientific literature relating to occupational therapy or occupational science.

All pertinent data were incorporated into the analysis, respecting the data’s true context, regardless of whether it supported or disproved the researchers’ personal understanding of the concept [Citation28,Citation29]. Sources are referenced with proper credit given to the originators of knowledge [Citation28,Citation29]. Furthermore, in accordance with the scientific, ethical and social responsibility that should govern a researcher’s conduct, All European Academics (ALLEA) principles for research integrity were considered including communication honesty, research reliability, objectivity, impartiality and independence, openness and accessibility, and reference fairness [Citation30].

A clear and comprehensive literature search can be achieved through strict adherence to a systematic methodology [Citation31], reducing bias and adding to research objectivity and impartiality [Citation30]. The following databases were searched successively to identify scientific journals: CINAHL with Full Text, AMED, MEDLINE, PsychINFO, PUBMED and OTseeker. The term ‘occupational identity’ OR ‘occupational identities’ was combined with ‘occupation’ AND ‘occupational therapy’ OR ‘occupational science.’ Using the ‘Advanced Search’ option, searches were limited according to the elections available on the databases to English language journal articles. Inclusion required articles to specify ‘occupational identity’ in the abstract, be written by an occupational therapist, and describe the experience of OI in the article Articles found relevant by abstract were fully reviewed. Exclusion criteria were articles not describing the experience of OI, articles expressing an opinion or solely examining the concept theoretically, articles that aimed to propose assessment, intervention or treatment methods and articles focussing on ‘occupation’ and ‘identity’ as single but related concepts. As primary source data are deemed important for analysis [Citation31] and first-hand analysis is critical to authenticity as well as understanding and representing true context, literature reviews were excluded. To investigate the concept’s current use, articles were restricted to those published from 2008 to February of 2019, when this search was conducted. Concepts change, acquire new meanings over time and vary according to their current contexts of use [Citation26]. From this perspective, current use is meant to reflect current OT practice. Natural use is also relevant – when a word is utilized within a situation or context ‘attributes of the word’s meaning’ are revealed [Citation26, p. 686]. Therefore, situations when occupational therapists used OI to refer participant experience within the context of OT were identified.

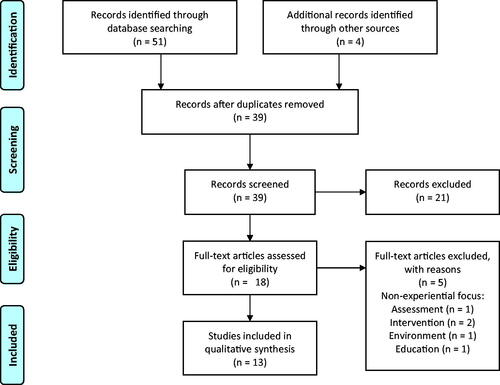

Database searches are not comprehensive; supplemental search methods maximize identification of relevant data [Citation31]. Therefore, reference lists of included articles and excluded literature reviews were searched. The database search resulted in 51 articles and supplemental search methods revealed 4 additional articles. After duplicates were removed, 39 articles were screened according to the predetermined inclusion and exclusion criteria resulting in the 21 articles being excluded and 18 articles remaining. Full-text review resulted in an additional 5 articles being excluded with reasons for not being an exploration of the experience of OI and 13 articles remaining. A PRISMA flow diagram outlining this search is presented in [Citation32].

With the intention of updating the results, the search process was repeated in November of 2019, applying the same procedure. The two articles found would not have altered the already established categories and therefore were not included.

Key characteristics of the reviewed articles, specifically the title, authors, journal and year of publication, purpose and participants are presented in .

Table 1. Overview of reviewed articles.

Data analysis was guided by the Walker and Avant [Citation23] method requiring, for example, differentiation between antecedents and consequences, and identification of attributes. To further facilitate concept data identification and characterization of OI usage, content analysis was implemented. Content analysis provides a systematic method for approaching analysis in qualitative research [Citation33]. The included articles were reviewed by two authors. Whereas one author identified categories and categorized data, another author affirmed the relevance of the categorization. Depending on its availability in the text, relevant manifest, latent or contextual content was sought for analysis [Citation33]. These data, in the form of meaning units, were extracted from the articles, analyzed, and condensed to represent its core meaning [Citation33]. Particular consideration was given to OI usage context, the situation for which OI was used and the significance of that use within OT. The Walker and Avant [Citation23] method of analysis was said to insufficiently relate concepts to their context, thus clarification of the context of use was deliberately included in this study with the aim of adding to the credibility of the analysis [Citation26]. Utilizing a systematic method for analysis links to credibility, dependability, and transferability, thus, trustworthiness in qualitative research [Citation33].

Results

Step 3: identifying all forms of concept usage

Usage includes both ‘explicit and implicit’ concept use [Citation23, p. 161]. The specific term occupational identity appeared to varying degrees in the articles, with its occurrence being attributed to the participants’ experiences by researchers. On the one occasion when the term was used by a participant, its meaning was attributed to a job [Citation#1]; however, the relevance of the content to occupation and its connection to identity remained.

OI usage was characterized according to the context of its use and application within OT. A discernible connection between occupation and identity was the basis for identifying relevant content. Clarifying the context of OI use within OT involved first determining the meaning of the individual experience referenced. The use of contextual categories was then meant to characterize the overall experience OI use was meant to represent. Analysis of the content in this context uncovered three distinct categories of use: OI construction, OI discrepancy and OI disruption. In the included articles, OI had been related to construction [Citation#1–#4] and disruption [Citation#5]. But to fully characterize the range of meanings and significance of OI usage conveyed and to achieve a comprehensive representation of the data the third category of discrepancy was created. OI experience reflected complex connections between occupation and identity, suggesting elements well-recognized within occupational science [Citation34]. Categories were thus also described in relation to the self being (an internal sense of who one knows oneself to be as an individual), the self being and doing (an external expression of the self as an individual), and the self being and doing with others (an external expression of the self as it relates to a collective). These subcategories were created to further distinguish the experience of OI as described in the texts. Beyond connections to doing and being, meanings revealed further connections with elements of becoming and belonging. Self refers to the reflective experiencing entity, encompassing thoughts, emotions, and motives [Citation35]. Examples of extracted meaning units, literal and condensed, along with codes delineating OI connections and contextual categories of use, are presented in .

Table 2. OI use extracted from included articles.

OI construction

OI construction characterizes the shaping or building of connections between being and doing over time. The self being denotes reflection or a perceiving of oneself as an occupational being. Success or failure, competence or incompetence from the past influenced one’s present sense of self or being with positive [Citation#6] or negative [Citation#1,Citation#7] implications. Similarly, one’s sense of past and current is connected to future being, doing or becoming [Citation#1,Citation#2,Citation#7,Citation#6]. This sense of self could relate to a role, for example, being a mother [Citation#6] a student [Citation#7] or a worker [Citation#1]; compatibility with and fulfilment of meaningful roles had a strong impact [Citation#6,Citation#8,Citation#9] as the meaningful doing associated to the known self-connected integrally to OI. Meaningful being also extended to objects of meaning that reinforced a particular sense of being [Citation#1,Citation#2]. Being was influenced not only by self-narratives but also others’ perception of one’s being and doing, as seen when family meanings were conveyed [Citation#2,Citation#7] or unknown others imparted meaning via shared societal views and expectations [Citation#1,Citation#2,Citation#7,Citation#9]. Personally, meaningful topics, like the value of work [Citation#9] or school [Citation#7] for the future, further influenced being. Multiple facets of the self were suggested, with different potentials for being through possible doing [Citation#1]. A willingness to know oneself anew and accept changes in ability connected to a sense of new being or future becoming [Citation#4,Citation#9,Citation#10].

Described in relation to the self being and doing, OI construction refers to how the established sense of self is expressed through individual agency or doing and is also constructed by way of doing. Meanings attributed to doing were highly relevant. As seen with roles, multiple facets of being can exist simultaneously. Ideally, doing to some extent should authentically express one’s being [Citation#1]. If personally meaningful, success while doing [Citation#3,Citation#4, Citation#11] and choice of doing [Citation#1,Citation#2,Citation#12] had positive implications for being and becoming [Citation#3]. Conversely, a lack of meaningful doing had negative implications for being [Citation#1,Citation#3], contributing to a negative experience of OI. Re-constructing one’s sense of self by reclaiming meaningful doing [Citation#9,Citation#12] or successfully employing new ways of doing [Citation#4,Citation#8,Citation#9] was described. Preservation of the known self, continued being through doing [Citation#1,Citation#9,Citation#12], was portrayed. Meaningful doing particularly fostered a sense of continuity [Citation#1,Citation#9,Citation#12]. Although continuity is often sought, OI is dynamic. A changing sense of self and what holds meaning resulted in changed occupations or doing [Citation#2,Citation#11]. Numerous connections between being and doing were suggested.

OI construction is further described relating to the self being and doing with others; being and doing often occurred in relation to others embedded within varying contexts. OI expression is influenced by other’s perception or expectations [Citation#2,Citation#6,Citation#9,Citation#8,Citation#10,Citation#11] and one’s own perception when one’s doing was compared to that of others [Citation#1,Citation#7]. Significant relationships with family [Citation#2] or partners [Citation#6] influenced being and doing. Meaningful doing with family, even if changed or altered, connected to being and belonging [Citation#8]. Similarly, sharing meaningful experiences by doing together beyond the family broadened the context of connections to greater people and places, linking to a sense of acceptance, understanding and belonging [Citation#1,Citation#2,Citation#4,Citation#6,Citation#7,Citation#8,Citation#10–#12,]. Meanwhile, an inability to form connections had negative implications for being and belonging [Citation#1,Citation#2,Citation#7,Citation#11]. Becoming was also influenced by others contributing to discontent or understanding and acceptance [Citation#6]. OI is influenced by social and cultural norms [Citation#2,Citation#7,Citation#8,Citation#10,Citation#11]; not meeting perceived standards for being and doing had negative implications [Citation#2,Citation#7]. Moreover, finding one’s place or a space for being and doing in broader society was important to one’s sense of self [Citation#8,Citation#10]. Multiple connections between OI and others in varied contexts impacted OI construction.

OI discrepancy

OI discrepancy characterizes a conflict or disconnect between the self and one or more of the established connections embodied in OI. The self being denotes a discrepancy of perception. Rejection of an attribute in oneself that is accepted in another [Citation#2] and a discrepancy between perceived role fulfilment in the past and actual role fulfilment [Citation#6] were described. These examples suggest a disparity between what is personally experienced and actuality.

In relation to the self being and doing, OI discrepancy describes an individually experienced incompatibility between one’s desire to be and do as before and one’s current capacity to do so. Valued activities were pursued regardless of physical consequences [Citation#4,Citation#5,Citation#13], suggesting a strong desire for continuity through meaningful doing.

OI discrepancy was most noted regarding the self being and doing with others. Incompatibility between one’s current disposition and previous being and doing with others in a former context [Citation#1] was cited. Reduced physical capacity interfered with meaningful, role-related doing when being a mother [Citation#4,Citation#15], grandmother [Citation#14] and friend or family member [Citation#8]. The desire to be and do as before with significant others superseded the ability to do with potentially negative consequences. OI discrepancy also demonstrated a contrast between one’s actual ability and other’s perceptions of said ability [Citation#2,Citation#8–#10] relating to underestimating [Citation#2,Citation#10] or overestimating [Citation#8,Citation#9] another’s capacity in different contexts. Others’ lack of understanding interfered with meaningful being and belonging, contributing to a negative experience of OI.

OI disruption

OI disruption characterizes a significant consequence to the aforementioned OI connections, fundamentally disrupting being and doing. Regarding the self being, the known self that was established through one’s being and doing, thus, far is lost, causing uncertainty for current being [Citation#6,Citation#11] or a longing for past being [Citation#6,Citation#9]. Perceived possibilities for being and becoming were impacted [Citation#9,Citation#10]. A substantial disruption of one’s sense of self as an occupational being was demonstrated.

Contrasting with reflecting on one’s loss as referred to above, OI disruption concerning the self being and doing occurred when the inability to do and thus be as before was experienced during individual agency [Citation#3,Citation#7]. Lack of choice regarding personally meaningful doing was also disruptive [Citation#3].

OI disruption was described most regarding the self being and doing with others as the disruption of who one had been and what one could do had direct implications for oneself in relation to others. OI disruption impacted meaningful roles [Citation#3,Citation#5,Citation#6,Citation#8,Citation#10,Citation#11], such as mother [Citation#3,Citation#6,Citation#8,Citation#11], partner [Citation#5], family member [Citation#11], worker [Citation#10] or athlete [Citation#5]. The inability to engage in role-related doing inhibited role-related being in these various contexts. Becoming [Citation#10] and belonging [Citation#10–#12] were substantially impacted. Disrupted being and doing connected to stigmatization, actual or anticipated, [Citation#10] and dissociation [Citation#11]. A lack of meaningful doing [Citation#2,Citation#11] or negative meanings imposed by others regarding one’s being and doing [Citation#10] connected to one’s sense of self, with negative implications for OI.

Step 4: determining the concept’s defining attributes

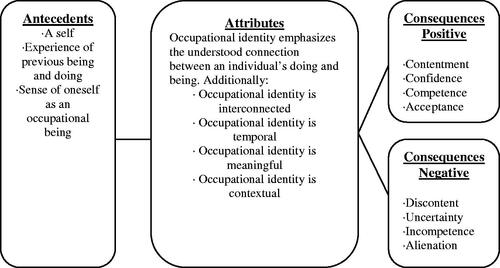

The concept’s attributes are its core characteristics, those that appear repeatedly and are associated most often [Citation23]. Attributes are chosen in relation to the aim of analysis [Citation23]. Analyzing natural use of OI – for this study its use within OT practice – should reveal attributes associated with the concept. Occupational identity emphasizes the understood connection between doing and being. Analysis of the OI experiences referenced in the studies characterized OI as being interconnected, temporal, meaningful and contextual.

OI is interconnected

Being is clearly connected to doing but is further connected to becoming and belonging. Connections are interrelated occurring internally and externally, individually and collectively.

OI is temporal

Connections are formed and exist over time. Connections to previous being and doing inform current being and doing. These connections also influence one’s sense of future becoming.

OI is meaningful

For doing to truly express one’s being, it must hold meaning. Meanings are derived from one’s own experiences of being and doing but also connect to others’ ascribed meanings.

OI is contextual

Being and doing are experienced within diverse contexts linking people and places. These contexts connect to one’s sense of being and how being is expressed through doing, influencing belonging in relation to others.

These attributes were present in each of the categories of OI use relating to OI construction, OI discrepancy and OI disruption.

Step 5: identifying a model case

A model case demonstrates all identified attributes of the concept; cases can be actual or created [Citation23]. The following example of a model case was constructed from participant experience to exemplify OI construction:

Alison, 11, is an active, young girl who happens to have Cerebral Palsy. Recently, she began horseback riding. She is very excited about her new hobby not only because she loves horses but because she wants to be more like her dad. She explained that he loves horses as much as she does and that he rode as a boy. Alison said being a rider is tricky but her dad gives her extra help on weekends when they ride together. Alison hopes to one day run a horse ranch with her dad.

The model case construction demonstrates a meaningful connection between Alison’s being and doing, and that of her father. Her sense of being is expressed through being and doing with her dad, connecting to a sense of belonging and becoming.

Step 6: identifying additional cases

Additional cases were also constructed from literature derived participant experience. A borderline case demonstrates most but not all the concept’s attributes [Citation23]. The following example of a borderline case was constructed to exemplify OI discrepancy:

Ruth, 27, who was diagnosed with cancer related lymphoedema, is the proud mother of 18-month-old Ian. She strongly identifies with the mother role and truly enjoys caring for Ian. She had established a perfect routine, every morning a trip to the park for a walk and a ride on the swing. Due to her lymphoedema, she was instructed not to lift her son. Ian stands by the swing and cries. Ruth laments this change. She acknowledges she can still care for Ian, but being a mother is tied to what they did before.

The borderline case construction demonstrates a meaningful connection between Ruth’s sense of being a mother and what she previously did as a mother. Her sense of being is still derived from role-related doing, yet she is conflicted as she is not allowed to express herself as a mother, as she once did.

A contrary case demonstrates none of the identified concept attributes [Citation23]. The following example of a contrary case was constructed to exemplify OI disruption:

Charles, 48, was discharged from rehabilitation after having had a stroke. On the drive home from the hospital he was overcome by an overwhelming sense of loss because he realized his life as he knew it was over. He would not be able to do any of the things that were important to him, his work as a teacher, coaching the little league, or tending to his garden. He imagined an empty, meaningless future and cried uncontrollably.

The contrary case construction demonstrates a serious disruption of the meaningful connections previously established between being and doing. Role-related being could no longer be expressed though role-related doing, such that Charles’ sense of current being and even future being was lost.

Step 7: identifying antecedents and consequences

Antecedents are events that must already be in place to enable the concept’s occurrence, while consequences are the outcomes of the concept’s occurrence [Citation23]. Data suggest that to experience OI: there must be a self; an experience of previous being and doing; and an awareness of oneself as an occupational being. Due to the subjective and experiential nature of OI, possible consequences could be positive, inducing a sense of contentment, confidence, competence or acceptance [Citation#1,Citation#2,Citation#4,Citation#6–#12], or negative, generating a sense of discontent, uncertainty, incompetence or alienation [Citation#1–#13], seemingly relating to compatibility or meaningfulness of expression and connection. The antecedents and consequences are presented, in connection to OI’s attributes ().

Step 8: defining empirical referents

Empirical referents, by their presence, aid in the concept’s identification and assessment and thus are closely linked to the concept’s attributes [Citation23]. OI attributes were identified as being interconnected, temporal, meaningful and contextual making OI dynamic and complex. OI experience is processed subjectively. Accordingly, it is the individual self, the reflective, experiencing entity, which must reveal his or her own experience of OI. OI encompasses an internal sense of being derived from connections to doing. The interconnectivity of OI extends through diverse contexts evidenced by an external expression of being through doing comprising individual and collective engagement in meaningful occupations. The experience of OI can be ascertained through self-reporting of one’s past and current occupations in connection to contentment with the self being, confidence and competence as it relates to the self being and doing, and acceptance regarding the self being and doing with others or belonging. This information should also be assessed temporally in consideration of not just the past and present, but also one’s future sense of self or becoming, with particular attention paid to meaningful occupations.

Discussion

In scientific literature, there are frequent references to OI conceptualized as ‘a composite sense of who one is and wishes to become as an occupational being generated from one’s history of occupational participation’ as defined by Kielhofner [Citation22, p. 106]. However, Unruh et al. characterized OI as ‘the expression of the physical, affective, cognitive, and spiritual aspects of human nature, in an interaction with the institutional, social, cultural, and political dimensions of the environment…’ [Citation12, p. 12]. These variations point to a distinction or division between the being and doing associated with OI.

Walker and Avant [Citation23] assert that conceptual clarification and refinement can be achieved through concept analysis. In this analysis, exploration of the experience of OI served to clarify this concept by revealing three distinct categories of use within OT: OI construction, OI discrepancy and OI disruption. OI was further described as being interconnected, temporal, meaningful and contextual. OI was presented as being rooted in the self, steadily extending outward through meaningful connections encompassing being, being and doing, and being and doing with others, further connecting to becoming and belonging. Described is a complex and dynamic concept where one’s being becomes known, expressed and known again through doing embedded in contextual and temporal dimensions across a lifetime. When reflecting on occupation, Wilcock emphasized the dynamic connection between doing and being, maintaining that through doing, being was altered [Citation34]. Interconnectivity is also reflected in the assertion that ‘… “doing” and “being” cannot be separated into distinct parts of occupational identity’ [Citation#1, p. 45]. The usage of OI in the identified categories supports this view.

Proposed is a complexity of intricate connections by which OI is continually derived and expressed, intersecting through diverse social contexts linking people and places. OI is both an internal sense of being derived from connections to doing, belonging and/or becoming; and an external expression of being through doing, connecting to becoming and/or belonging. Connections contributing to OI construction are prevalent and moreover ideally intact, authentic and compatible, as discrepancies or disruptions of the meaningful connections formed can potentially devastate the self that is known. Thus, meaning attributed by the self and others, or deriving meaning for oneself through meaningful expression, is particularly significant.

Phelan and Kinsella [Citation4] critically examined OI, noting an overemphasis on individual determination and underestimation of social influences. Asaba and Jackson [Citation24] extended this discourse, asserting that identities are negotiated through social contexts via occupation. OI responds to and is embedded within social–cultural contexts [Citation36]. This analysis shows that context shapes OI; OI shapes our perception, intentions, decisions and desires. OI is intricately interconnected to its surrounding circumstances. Individual agency occurs in relation to others’ agency, indicating a process that is not only an internal sense, but something also externalized and collectively experienced [Citation37]. OI is, in part, derived from a perception of the self-doing with others in diverse, changing contexts [Citation8]. Occupations also connect us to others. Engagement with others fosters belonging [Citation4]. Doing intertwines with belonging, and as these findings indicate, is not easily separated [Citation38]. Furthermore, through our interactions with others, doing acquires meaning [Citation7]. Meaning connects not only to doing, being and becoming, but closely to belonging [Citation7,Citation39]. In fact, life gains personal significance from the people and places of which we form part [Citation3]. Social–cultural dimensions are clearly important determining factors [Citation4,Citation24,Citation36,Citation40]; however, OI essentially comprises both individual and collective components [Citation24,Citation36]. OI is uniquely defined by the subjective experience of the self. Bound yet not confined to the individual, OI interconnects through broader, social contexts embedded in meaning and belonging.

In occupational science, future directions for research and development may include exploration of the relevance of meaningful expression and connection in cultivating positive OI experiences and the significance of differing contexts throughout life. In practice, OT could utilize occupation to facilitate a sense of connectedness reflective of the circumstances of our clients’ belonging. By reconciling discrepant and re-establishing disrupted connections, especially when personally meaningful, we may support our clients’ lifelong engagement as occupational beings. Indeed, Wilcock advocated that OT encompass not just what people do but how it relates to who they are, as through doing people shape the societies of which they are part and the world at large [Citation34].

OI encompassed complex connections comprising both individual and collective components. Personally meaningful expression and connection were of particular significance to OI, as discrepancies or disruption of meaningful connections had negative implications for occupational engagement.

Limitations

Claims that Walker and Avant’s method is linear exist, though they stipulate ‘this is a process, not a linear activity’ [Citation23, p. 159]. Nonetheless, their method has been widely used within OT to clarify occupational balance [Citation41], professional confidence [Citation42], self-determination [Citation43] and spirituality [Citation44]. Another ascribed limitation is that this method lacks contextual data, as scientific concepts should be precise and are highly dependent on context for meaning [Citation26]. Addressing this proclaimed limitation resulted in not following the recommendations of the selected method of analysis as written. Although context was a central focus in this analysis, concept identification was not precise. Cited usage was inferred, as most participants did not name OI [Citation#11]. Because cited occurrences were not self-evident, another researcher may have drawn different conclusions, therefore, the results are not conclusive. Moreover, due to the concept’s inherent connectivity, the categories and subcategories presented were not always clearly discernible. It was thought that following a systematic approach for analysis of content would help to define context while adding to the study’s trustworthiness [Citation33]. Analysis may have benefitted by a peer checking of intercoder reliability; however, all authors contributed to the research process and category agreement by co-authors was achieved.

Conclusion

Concept analysis to clarify the current use and application of occupational identity within OT resulted in three categories of use, namely OI construction, OI discrepancy and OI disruption. Findings validated the compelling connection between occupation and identity, doing and being, and future becoming. Further uncovered were complex connections to diverse people and places over time, embedded in belonging and interwoven with meaning. In the end, what one does connects not only to who one is [Citation1], but more so, whom one is with and feels part of.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Laliberte-Rudman D. Linking occupation and identity: lessons learned through qualitative exploration. J Occup Sci. 2002;19:12–19.

- Christiansen C. Occupation and identity: becoming who we are through what we do. In: Christiansen C, Townsend E, editors. Introduction to occupation: the art and science of living. 7th ed. Upper Saddle River (NJ): Prentice Hall; 2004. p. 121–139.

- Christiansen CH. The 1999 Eleanor Clarke Slagle Lecture. Defining lives: occupation as identity: an essay on competence, coherence, and the creation of meaning. Am J Occup Ther. 1999;53:547–558.

- Phelan S, Kinsella EA. Occupational identity: engaging in socio-cultural perspectives. J Occup Sci. 2009;16:85–91.

- Yerxa EJ. Occupation: the keystone of a curriculum for a self-defined profession. Am J Occup Ther. 1998;52:365–372.

- Alsaker S, Josephsson S. Negotiating occupational identities while living with chronic rheumatoid disease. Scand J Occup Ther. 2003;10:167–176.

- Taylor J, Kay S. The construction of identities in narratives about serious leisure occupation. J Occup Sci. 2015;22:260–276.

- Vrkljan B, Polgar J. Linking occupational participation and occupational identity: an exploratory study of the transition from driving to driving cessation in older adulthood. J Occup Sci. 2007;14:30–39.

- Stets JE, Burke PJ. Identity theory and social identity theory. Soc Psychol Q. 2000;63:224–237.

- Reynolds KJ. Social identity. In: Wright JD, editor. International encyclopedia of the social and behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Amsterdam: Elsevier Ltd; 2015. p. 313–318.

- Hogg MA, Terry DJ, White KA. tale of two theories: a critical comparison of identity theory with social identity theory. Soc Psychol Q. 1995;58:255–269.

- Unruh AM, Versnel J, Kerr N. Spirituality unplugged: a review of commonalities and contentions, and a resolution. Can J Occup Ther. 2002;69:5–19.

- Du Toit S, Wilkinson A. Promoting and awareness of research-related activities: the role of occupational identity. Br J Occup Ther. 2011;74:489–493.

- Ashworth E. Utilizing participation in meaningful occupation as an intervention approach to support the acute model of inpatient palliative care. Palliat Support Care. 2014;12:409–412.

- Howie L, Coulter M, Feldman S. Crafting the self: older persons' narratives of occupational identity. Am J Occup Ther. 2004;58:446–454.

- Wilson LH. Occupational consequences of weight loss surgery: a personal reflection. J Occup Sci. 2010;17:47–54.

- Braveman B, Helfrich C. Occupational identity: exploring the narratives of three men living with AIDS. J Occup Sci. 2001;8:25–31.

- Collins M. Spiritual emergency and occupational identity: a transpersonal perspective. Br J Occup Ther. 2007;70:504–512.

- Cotton GS. Occupational identity disruption after traumatic brain injury: an approach to occupational therapy evaluation and treatment. Occup Ther Health Care. 2012;26:270–282.

- Braveman B, Kielhofner G, Albrecht G, et al. Occupational identity, occupational competence and occupational settings (environment): influences on return to work in men living with HIV/AIDS. Work. 2005;27:267–276.

- Curtin J, Hitch D. Experiences and perceptions of facilitators of THE WORKS. Work. 2018;59:607–616.

- Kielhofner G. Dimensions of doing. In Kielhofner G, editor. Model of human occupation: theory and application. 4th ed. Baltimore (MD): Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008. p. 101–109.

- Walker LO, Avant KC. Strategies for theory construction in nursing. 5th ed. Upper Saddle River (NJ): Prentice Hall; 2011.

- Asaba E, Jackson J. Social ideologies embedded in everyday life: a narrative analysis about disability, identities, and occupation. J Occup Sci. 2011;18:139–152.

- Pierce D. Occupational science: a powerful disciplinary knowledge base for occupational therapy. In: Pierce D, editor. Occupational science for occupational therapy. Thorofare (NJ): SLACK Incorporated; 2008. p. 1–10.

- Risjord M. Rethinking concept analysis. J Adv Nurs. 2008;22:684–691.

- Collins English Dictionary [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Mar 23]. Available from: https://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/occupational.

- Creswell JW. Research design: qualitative, quantitative, & mixed methods approaches. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks (CA): SAGE Publications Inc; 2014.

- Machi LA, McEvoy BT. The literature review: six steps to success. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks (CA): Corwin, A SAGE Company; 2016.

- The European Code of Conduct for Research Integrity [Internet]. Amsterdam: ALLEA; 2011. [cited 2019 Jun 11]. Available from: https://www.allea.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/Code_Conduct_ResearchIntegrity.pdf.*

- Aveyard H. Doing a literature review in health and social care: a practical guide. 3rd ed. Maidenhead: Open University Press; 2014.

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, PRISMA Group, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:1006–1012.

- Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today. 2004;24:105–112.

- Wilcock AA. Reflections on doing, being and becoming. Aust Occup Ther J. 2002;46:1–11.

- Carlson M, Park DJ, Kuo A, et al. Occupation in relation to the self. J Occup Sci. 2014;21:117–129.

- Laliberte Rudman D, Dennhardt S. Shaping knowledge regarding occupation: examining the cultural underpinnings of the evolving concept of occupational identity. Aust Occup Ther J. 2008;55:153–162.

- Phillips PA, Kelk N, Fitzgerald MH. Object or person: the difference lies in the constructed identity. J Occup Sci. 2007;14:162–171.

- Hammell KW. Self-care, productivity, and leisure, or dimensions of occupational experience? Rethinking occupational "categories". Can J Occup Ther. 2009;76:107–114.

- Kantartzis S, Molineux M. The influence of western society’s construction of a healthy daily life on the conceptualization of occupation. J Occup Sci. 2011;18:62–80.

- Unruh AM. Reflections on: "So. what do you do?" Occupation and the construction of identity?. Can J Occup Ther. 2004;71:290–295.

- Wagman P, Håkansson C, Björklund A. Occupational balance as used in occupational therapy: a concept analysis. Scand J Occup Ther. 2012;19:322–324.

- Holland K, Middleton L, Uys L. Professional confidence: a concept analysis. Scand J Occup Ther. 2012;19:214–224.

- Ekelund C, Dahlin-Ivanoff S, Eklund K. Self-determination and older people-a concept analysis. Scand J Occup Ther. 2014;21:116–124.

- Jones J, Topping A, Wattis J, et al. A concept analysis of spirituality in occupational therapy practice. J Study Spiritual. 2016;6:38–57.

References Included Articles

- Blank AA, Harries P, Reynolds FR. Without occupation you don’t exist’: occupational engagement and mental illness. J Occup Sci. 2015;22:197–209.

- Phelan SK, Kinsella EA. Occupation and identity: perspectives of children with disabilities and their parents. J Occup Sci. 2014;21:334–356.

- Hess-April L. A study to explore the occupational adaptation of adults with MDR-TB who undergo long-term hospitalization. South Afr J Occup Ther. 2014;44:18–24.

- Johansson C, Isaksson G. Experiences of participation in occupation of women on long-term sick leave. Scand J Occup Ther. 2011;18:294–301.

- Man A, Davis A, Webster F, et al. Awaiting knee joint replacement surgery: an occupational perspective on the experience of osteoarthritis. J Occup Sci. 2017;24:216–224.

- Martin LM, Smith M, Rogers J, et al. Mothers in recovery: an occupational perspective. Occup Ther Int. 2011;18:152–161.

- Levanon-Erez N, Cohen M, Traub Bar-Ilan R, et al. Occupational identity of adolescents with ADHD: a mixed methods study. Scand J Occup Ther. 2017;24:32–40.

- Del Fabro Smith L, Suto M, Chalmers A, et al. Belief in doing and knowledge in being mothers with arthritis. OTJR Occup Particip Health. 2011;31:40–48.

- Walder K, Molineux M. Re-establishing an occupational identity after stroke – a theoretical model based on survivor experience. Br J Occup Ther. 2017;80:620–630.

- Bryson-Campbell M, Shaw L, O’Brien J, et al. Exploring the transformation in occupational identity: perspectives from brain injury survivors. J Occup Sci. 2016;23:208–216.

- VanderKaay S. Mothers of children with food allergy: a discourse analysis of occupational identities. J Occup Sci. 2016;23:217–233.

- Liddle J, Phillips J, Gustafsson L, et al. Understanding the lived experiences of Parkinson's disease and deep brain stimulation (DBS) through occupational changes. Aust Occup Ther J. 2018;65:45–53.

- McGrath T. Irish insights into the lived experience of breast cancer related lymphoedema: implications for occupation focused practice. World Federation Occup Ther Bull. 2013;68:44–50.