Abstract

Background

Children in need of special support (INS) often display delays in time-processing ability (TPA) affecting everyday functioning. Typically developing (TD) children are not yet mature to use the information of a clock.

Aim

To investigate the feasibility of an intervention program, MyTime, to facilitate TPA and everyday functioning in pre-school children, including the subjective experiences of pre-school staff and the children.

Materials and Methods

The intervention sample consisted of 20 children: 4 INS and 16 TD. Intervention was given daily in 8 weeks with MyTime in the pre-school environment. Data collection procedures were evaluated and children were assessed for TPA pre- and post intervention. Everyday functioning were assessed by teachers, parents and children. Experiences of the intervention were assessed by a group interview with teachers and a Talking Mats© evaluation with children.

Results

MyTime worked well in pre-school and indicated an increase in the children’s TPA and everyday functioning. The program was perceived simple to use by teachers and children highlighted the importance to understand the duration of time.

Conclusion

The program MyTime was found to be feasible in the pre-school environment. Significance: The assessment and program design can be used to investigate intervention effectiveness in a randomised study.

Introduction

The ability to process and manage time not only affects children’s everyday functioning [Citation1,Citation2] but is also important for human occupation [Citation3]. Children with cognitive disabilities (e.g. attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, ADHD) have shown difficulties in time management, often with negative consequences for everyday life [Citation4–7] and academic achievement [Citation8]. These children have difficulties in estimating time and independently planning and executing school tasks on time. Most research investigating children and time has focussed on school-aged children with ADHD, but an increasing number of studies have widened this research agenda. Still, no evaluated intervention model facilitates the time processing ability (TPA) of pre-school children with disabilities or in need of special support (INS). Thus, this study aims to investigate the feasability of an intervention program, MyTime, to facilitate the TPA in pre-school children for an upcoming randomised controlled trial (RCT).

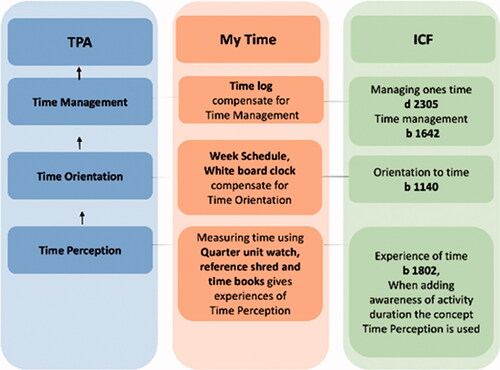

TPA consists of several subcategories, described in the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) [9]. provides an overview of the cognitive concepts of time included in body functions in ICF. Experiences of time (b1802) are defined as specific mental functions of the subjective experiences related to the length and passage of time. Adding awareness of the duration of activities, the concept time perception emerges. This area develops at an early stage and requires a low level of abstraction. The next development area, ‘Orientation to time’ (b1140) (presented as Time orientation in ), includes mental functions producing an awareness of today, tomorrow, yesterday, as well as the date, month and year. The last development area, ‘Time management’ (b1642), involves ordering events chronologically, allocating time for events and activities. These three concepts of time are cognitive functions that serve as a unified construct, operationalised as different levels in a hierarchy of complexity summated into TPA [Citation1,Citation10].

Figure 1. The relation between the key concepts; Time perception, Time Orientation and Time management as one construct called TPA. TPA in interaction with Environmental factors and Person factors results in a person’s Daily Time Management [Citation11].

![Figure 1. The relation between the key concepts; Time perception, Time Orientation and Time management as one construct called TPA. TPA in interaction with Environmental factors and Person factors results in a person’s Daily Time Management [Citation11].](/cms/asset/5760c304-7fa9-4af4-bc86-c8ebe7d0b907/iocc_a_1981434_f0001_c.jpg)

TPA also includes time perspective, both past and visionary (future), as well as when planning activities. This skill is needed to socialise and obtain a practical overview (e.g. understanding what will happen during the day and at what time) [9]. TPA, as a processing skill, develops through Time Perception, Time Orientation and Time Management. The child’s ability to process time is also affected by environmental factors (), including a structured visual environment and daily routines in, for example, a pre-school setting and by personal factors (), such as age and level of cognitive function. In Sweden, as in many other European countries, all mainstream pre-school education and care are inclusive [Citation12]. Inclusive care implies that almost all children with a diagnosed disability or informal needs of special support are included in the same preschools as their typically developing (TD) peers. Children with disabilities or INS have a formalised plan for support in their pre-school environment. However, this plan does not imply that the children have received a formal diagnosis. Very few INS children in the pre-school ages in Sweden have a formal diagnosis. Still, many children without a formal diagnos may display functional difficulties in group environments, such as the pre-school setting. In this study INS children are defined as children with a formalised plan in pre-school.

Daily time management

The level of TPA, together with other personal and environmental factors, affects children’s daily time management, i.e. the ability to manage time in everyday life () [Citation1]. In the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health – Child and Youth version (ICF-CY, [Citation13] daily time management is described by two concepts: managing onés time (d2305) and adapting to time demands (d2306). These two concepts can be considered two sides of the same construct- daily time management [Citation14]. Since 2019, the Swedish health authorities' recommendations suggest using the updated ICF for all ages [Citation15]. In the updated version one concept is accepted: managing onés time (d2305), i.e. managing the time required to complete usual or specific activities (e.g. as preparing to depart from the home) [16]. Managing onés time is categorised within the domain activity and participation in ICF and is a central aspect also of children’s everyday functioning. In this study daily time management is equivalent to managing onés time [Citation13].

The significance of the level of TPA, daily time management and everyday functioning

A diagnosis does not offer enough information about a child’s functional difficulties. Functional difficulties (e.g. speech and language delay), peer interaction, attention problems and hyperactivity are also seen in children not formally diagnosed. In Swedish pre-school children with such difficulties are informally identified by pre-school staff as children with INS [Citation17]. However, these children's difficulties may be similar to those of children with a formal diagnosis. In a study by Lillvist et al. (2010) teachers in 571 Swedish preschools reported that 17.3% (n = 1574) of the children had functional difficulties requiring special support. However, in their sample only 3.7% had a formal diagnosis. The functional difficulties in undiagnosed children (13.6%) could not be separated from children with a diagnosis [Citation17]. In Sweden children with disabilities are commonly diagnosed at school age, even though their problems often become prominent in pre-school. In six-year-old children problems with hyperactivity and behaviour seriously influence everyday functioning, including problems with initiating and completing activities and an increased need for structure [Citation18]. Although few children have obtained a specific diagnosis before school age [Citation17], they can still display developmental delays affecting TPA, resulting in impaired everyday functioning compared to same-aged peers. Delayed TPA in pre-school ages can also have profound consequences for their later ability to be prepared for school. Everyday functioning is a multidimensional concept with several definitions. In this study everyday functioning includes conceptual, social and practical skills [Citation19], as well as autonomy and daily time management [Citation1,Citation20]. Research indicates that process skills in TD children 6 to 9 years old are vital for autonomy in everyday functioning [21]. This could also be applicable to the process skill TPA. Studies have shown a significant relationship between children's self-rated autonomy and TPA and between parent ratings of the child’s daily time management and TPA in younger children [Citation1,Citation2]. Both autonomy and daily time management are significant dimensions of everyday functioning and essential prerequisites for later school adjustment. Thus, children with functional difficulties but who have not necessarily yet been diagnosed can benefit greatly from an early intervention that facilitates TPA in pre-school.

TD pre-school children usually have general knowledge about the duration of activities (what takes a long vs. short time to do) and daily activities' temporal order. Both are needed before learning to read and understand a clock [Citation22]. A study of TPA in TD children aged 5–10 years revealed that most of the least able pre-school children passed all items measuring time perception and the easiest item in time orientation placing pictures in temporal order [Citation10]. The study also found a significant correlation between children's TPA and parent-rated daily time management (as measured with Time-P), indicating a relationship between TPA and everyday functioning [Citation1]. Thus, most TD children do not need special measures to facilitate their TPA. However, TD children, not yet mature to understand and use the information from an ordinal clock, could benefit from intervention training abilities related to TPA affecting everyday functioning in an inclusive pre-school setting. Children with different cognitive and developmental disabilities experience different problems concerning time and can have TPA patterns similar to children 1–3 years younger [Citation2,Citation23,Citation24]. Although the TPA level could be a more valid base for designing TPA interventions compared to child diagnosis, most research in this area is diagnosis-specific [Citation2]. Studies show that the ability to manage time, maintain focus and finish an activity does not correspond to biological age in children with Spina bifida [Citation25], autism [Citation2,Citation26] and intellectual disabilities (IDs) [Citation24,Citation27]. Everyday functioning in the management of time described in these studies is similar to that found in children with ADHD. Thus, when conducting interventions to promote TPA in pre-school children, a diagnosis is probably not one of the most valid inclusion criteria. Instead, the degree of functional difficulties affecting everyday functioning should guide the assessment of needs to support TPA by the intervention.

Interventions to support TPA and everyday functioning

Several studies have evaluated interventions designed to support TPA in school-aged children. One randomised study investigated an intervention using time assistive devices in 6–10-year-old children with functional disabilities. TPA and the ability to manage time increased more in the intervention group than in the control group [Citation27] training organisation and time management in school-aged children with ADHD have also shown positive results [Citation7,Citation8]. Still, there is a lack of knowledge on how to remediate the time perception that develops earlier than both orientations to time and time management [Citation10]. Hence, TPA intervention programs in young INS children must be evaluated for their feasibility and usefulness in inclusive pre-school settings. The National Agency has developed a new occupational therapy (OT) intervention program for systematic training of TPA in children with IDs (called ‘MyTime’) for Special Needs Education and Schools (Swedish: SPSM) [Citation28]. The MyTime program is based on' the quarter-hour principle’ method derived from time-assistive devices [Citation29]. The purpose is to provide multiple options to collect experiences of the duration of everyday activities, using a system of dots in which each dot represents a quarter of an hour (15 min) [Citation28]. MyTime was evaluated in a randomised study showing that the 8-week program effectively increased TPA in children 10–17 years of age (n = 60) with mild to moderate IDs [Citation30]. Whether this method works for pre-school INS children is unclear.

To summarise, INS children with functional difficulties are at risk of developing or establishing low TPA. In addition, TD peers are not yet mature enough to use the information from an ordinal clock [Citation10]. Thus, both children with and without special needs in inclusive pre-school settings can benefit from a TPA intervention. Although evidence indicates the need for early intervention to prevent difficulties affecting everyday functioning and later school readiness, there is no evaluated method to facilitate TPA in TD children aged 5–6 years. Interventions to facilitate TPA development in inclusive pre-school settings may prevent future gaps between TD and INS children. Time perception is a crucial skill also for TD children to acquire before learning to use a clock [Citation10]. Although TD children are expected to have higher baseline values in TPA, they could still benefit from participating in the intervention. Therefore, in this study MyTime is implemented for all children in the same inclusive preschools.

Feasibility

Feasibility studies are still rare in OT research despite the importance of building a foundation for more extensive studies [Citation31]. Feasibility studies conduct parts of an upcoming study but on a smaller scale focussing on the feasibility of the intervention for the target group in the specific context [Citation32]. This is a feasibility study, evaluating all parts of a planned RCT, except the randomisation. It also adds a group interview with participating teachers not planned in the upcoming RCT. The interview was performed to reveal the possible obstacles preventing the successful implementation of an intervention in the RCT. Implementation is facilitated if the teachers are provided training, support and consultation [Citation33].

This study aimed to investigate the feasibility of an intervention program, MyTime, to facilitate TPA and everyday functioning in pre-school children with and without INS. In this study MyTime was extended for use with pre-school-aged children by adding time assistive devices.

Methods

This feasibility study was inspired by Orsmond and Cohn [Citation34]. We used five objectives to describe and evaluate the study process: (1) Evaluation of Recruitment Capability and Resulting Sample Characteristics, (2) Evaluation and Refinement of Data Collection Procedures and Outcome Measures, (3) Evaluation of Acceptability and Suitability of Intervention and Study Procedures, (4) Evaluation of Resources and Ability to Manage and Implement the Study and Intervention (5) Preliminary Evaluation of Participant Responses to the MyTime Intervention Program. The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board of Uppsala (Dnr 2013/470).

Participants

Here the obstacles and successes in recruiting children and the current sample are presented according to Objective 1. Both TD and INS children were invited to participate in the study. Inclusion criteria for all children were age 5–6 years during the year of the intervention and informed consent from children and parents. A specific inclusion criterion for INS children was a formalised plan for special support in pre-school. Exclusion criteria for all children were difficulties communicating. Exclusion criteria for INS children were early development stage and lack of a formalised plan for special support.

Consistent with the ethical approval, at least one of each child’s parents gave written consent. Twenty parents and six teachers gave informed consent to participate in the study. Four groups with five children (one INS child and four TD children) in each were included (n = 20). Of the 20 children, there were 3 INS boys and 1 INS girl and 9 TD boys and 7 TD girls. The children participated during two semesters: two groups in the spring (groups 1 and 2) and two groups in the autumn (groups 3 and 4).

The first contact to identify a pre-school with children aged 5 or 6 years, including INS children, was taken with a special pedagogue in the municipality. When a suitable pre-school had been identified, we contacted the principal by sending written information about the study followed by a phone call. We then asked pre-school teachers to participate, giving them written information about the intervention study. Pre-school teachers asked parents with INS and TD children 5–6 years of age to participate. We received positive responses from parents of 16 TD children and 4 INS children with a formalised plan. Finally, we informed the TD and INS children and asked them to participate. We gave the children an adapted information form, including a picture showing the assessing situation. The children signed the invitation. Children and pre-school teachers from four diverse groups in the same pre-school participated in the study. The same pre-school participated twice, during spring and the following autumn.

Measures

Here the measures and assessment of the different instruments are presented according to Objective 2.

We used the KaTid-Child® instrument [Citation35] to measure TPA as the key outcome. The Autonomy scale [Citation36], the Time-Parent (Time-P) scale and the Adaptive Behaviour Assessment Scale (ABAS-II©) and Autonomy scale were used to measure changes in everyday functioning [Citation19]. The first author (SWA) distributed the ABAS-II and Time-P to pre-school teachers. The pre-school teachers helped to distribute the ABAS-II (parent form) to parents. Pre-school teachers collected the material and filled in the ABAS-II (teacher form) for all the children and returned the material to the first author, before data collection with KaTid-Child and Autonomy scale started.

The first author, an occupational therapist and trained KaTid-rater, administered the KaTid and Autonomy scale assessments in a convenient pre-school room. Data collection was performed at baseline (t1) and after 8 weeks of the intervention (t2). At t2, the children’s intervention experiences were collected using Talking Mats© (TMs). During the 8-week intervention, all teachers documented the frequency and type of intervention work in the logbook on a daily basis for each child ().

Changes in TPA were evaluated with the KaTid-Child instrument. Changes in everyday functioning were measured with ABAS-II, Time-P, and the Autonomy scale. The children’s perceptions of the intervention were evaluated with TMs [Citation37,Citation38] and quantitatively rated on a three-point scale from 1 (positive) to 3 (negative).

To evaluate the intervention's acceptability and suitability we conducted a group interview to investigate the pre-school staff’s experiences of carrying out the intervention. The first author developed the interview guide, supported by the second author. The group interview was audio-recorded, included three pre-school teachers and two childcare workers and lasted 2 h. The group interview was conducted by the first author who was thereby involved in the whole process from creating the interview guide to analysing the data.

Assessment to measure TPA

The KaTid-Child instrument contains 57 items measuring time perception, time orientation and time management, all of which are summated into TPA. KaTid-Child was validated using data from 5–10-year-olds with and without a disability, with acceptable psychometric properties, providing support for construct validity (internal consistency α = 0.78–0.86) [Citation1,Citation10]. Person separation was 3.21 (rel.0.91), indicating that the items could separate TD children aged 5–10 years (n = 144) into four levels of TPA and that it can be used to measure change, also shown in a previous RCT study [Citation1,Citation27].

After the intervention was completed, TMs [Citation37,Citation38] were used to obtain the children’s experiences. TMs can support children with cognitive and functional difficulties in conversations and in making choices. To visualise choices and opinions pictures are placed in three visually defined areas on a mat with three response alternatives: positive, do not know and negative. The choices can easily be adapted to suit individual needs in a semi-structured interview. In this study we used pictures of each component of the intervention (e.g. the quarter unit watch, Time Book, and White Board clock). The children were given a picture, followed by the question, ‘What do you think about this’? After the child had placed the picture on the three-point TM scale, the first question was followed by a second question, ‘Can you tell me why you placed it here’? In that way, the child being interviewed is in control over the entire process and can influence the talking pace [Citation38,Citation39].

Assessment to measure everyday functioning

To measure adaptive behaviour we used the ABAS-II Parent Form and the Teacher Form as one dimension of everyday functioning. The ABAS-II, developed for children aged 5–21 years, has nine scales associated with three skills: conceptual, social, and practical. Conceptual skills include the scales communication, functional academics, and self-direction. Social skills entail the scales leisure and social while the practical skills scale encompasses community use, home/school living, self-care and health and safety. Each scale is presented with four response alternatives ranging from 0 (lack of prerequisite to 4 (always/almost always). The ABAS-II also gives a degree of general adaptive composite score derived from the nine scales. Both the Parent and the Teacher Form were psychometrically sound (internal consistency for the Parent and Teacher Form was α = 0.90–0.97 and α = 0.95–0.97, respectively) [Citation19]. The ABAS-II Parent form was filled in by the parents and the Teacher form by the pre-school teachers. Time-P is a parent rating of the child’s daily time management. The instrument includes 12 statements using a Likert scale with four response alternatives ranging from 1 (No, I don’t agree at all) to 4 (Yes, I fully agree). The version for children aged 5–10 years was found psychometrically sound (internal consistency α = 0.79–0.86) [Citation1,Citation10]. Time-P [Citation1,Citation10] was filled in by the parents.

Because there is no self-rating of daily time management evaluated for pre-school children, the Autonomy scale was chosen to capture one dimension of everyday functioning. This scale is a self-rating instrument derived from a longer, validated questionnaire [Citation36]. The original Swedish version for children aged 7–12 years has been used in several studies indicating a close connection between autonomy and functional outcomes, such as participation [Citation20,40]. The Autonomy scale, presented by the first author, was used with pictures representing each statement. A Likert scale with four statement alternatives (I do this always, I do this often, I do this sometimes and I never do this) was also presented with pictures. The children pointed to the chosen alternative and the first author filled in the form. The full version of this instrument would have been time-consuming to administer in this study and the time duration to answer too long for children in these age groups. The short version of the Autonomy scale has previously been validated for construct validity in children aged 6–10 years with and without disabilities, indicating acceptable psychometric properties (α = 0.79–0.86) [Citation1,Citation10]. The relationship between TPA's cognitive functions, autonomy, and daily time management as an essential part of everyday functioning was identified in Blinded1, 2009.

Procedure

Here the preparation for intervention and study procedure are presented according to Objective 3.

The teachers were first provided training in TPA and everyday functioning and how to use the intervention materials. The training sessions lasted for approximately 2 h. During that time, the teachers tested the different parts of the intervention material and recieved support in how to use the method. The training session was followed by weekly coaching on implementing the intervention program during the intervention period. The pre-school teachers were able to contact the first author at any time. The first author implemented training on how to use the program.

The materials for the intervention were supplied free of charge. The intervention was conducted in pre-school and integrated into the educational process by pre-school teachers. All children in the pre-school setting took part, regardless of participation in the study.

MyTime contains tasks for training TPA [Citation28], and in this study, the program was combined with time assistive devices. The program's key words are visualising, documenting, processing, and discussing time in concrete terms requiring early-level abstraction abilities. Focus was on time perception and time orientation [Citation1,9]. At the group level, the pre-school teachers could help the children explore time by visualising and measuring daily activities in quarter-hour units and documenting this in time books. The teachers and children also process and discuss time concretely and visually. This part of the intervention supports time perception [Citation1,9]. The time-assistive devices used were a Picture Schedule and a Whiteboard Clock. These time-assistive devices supported the transformation of the abstract time concepts into concrete things which children and teachers could handle and carry during the day. The Picture Schedule visualises the week's days, with each day having its colour according to the national system used in Sweden. The Whiteboard Clock works as an ordinary clock and shows the time with lit diodes in a vertical line of dots, with each dot representing a quarter of an hour. It is used to visualise the most important activities during the day; for example, each child's picture is put beside the ‘dot’ indicating their time to go home. This part supports the measured items for time orientation in the KaTid-Child instrument [Citation35] and the ICF subcategory Orientation to time b 1140 [9]. The children examine how many dots are left before home time and are encouraged to discuss and process with a friend the number of dots they can play with before someone must go home. The links between TPA, MyTime and ICF are presented in . The intervention was implemented daily for 8 weeks. During the 8 weeks of intervention, the pre-school teachers received weekly support from the first author.

To evaluate the intervention and study procedure’s acceptability and suitability, we conducted a group interview with the teachers using MyTime. The group interview (n = 5) included three female pre-school teachers and one male childcare worker. The interview was transcribed verbatim and analysed using qualitative content analysis inspired by Graneheim and Lundman [41].

In the first step of the analysis the meaning units judged to contain information related to the study's aim were identified and colour-coded by the first author. The units were then saved in a new document and condensed into codes without changing their perceived content. Codes with similar content were grouped into subcategories. When all codes were sorted into subcategories, the second author read the material to check whether the meaning units were correctly coded and placed in the appropriate subcategories. The subcategories were then sorted into categories, checking that each subcategory could only link to one category. Next, the second author reread the material and then analysed the codes, subcategories, and categories independently from the first author, which led to minor changes to these three units. Both authors then discussed the content of the subcategories and categories. This process was repeated until a consensus of the content was reached, resulting in a final count of four categories and twenty subcategories. Following this phase, the third author read the meaning units, condensations, codes, subcategories, and categories. Some minor changes were made in condensations and codes and suggestions to two of the categories and 17 subcategories were presented. Two categories and 18 subcategories were finally derived after suggestions from the first author. The first and third authors developed a general theme. The analysis continued until consensus was achieved according to the aim of the study ().

Table 1. Examples of meaning units, condensations, codes, subcategories and categories.

Results

The results are presented using the headings for the five Objectives.

Objective 1: Evaluation of recruitment capability and resulting sample characteristics

It was more demanding for the teachers to implement the intervention when starting in the autumn because at that time most children start pre-school in Sweden. In the autumn, the teachers form the pre-school groups and become acquainted with the children. It is also when children learn to know each other. Still, both children and pre-school teachers in all groups managed to complete both assessments and interventions.

By collecting data over several years we will have the advantage of re-using resources, e.g. data collectors and intervention material. By using pre-school teachers as recruiters, the recruitment process was fluent, unproblematic, and resource efficient. Children with a formalised plan for support are few in each pre-school compared to TD children. For an RCT that includes only TD children, the recruitment process could be managed during one spring semester. We also learned that the recruitment process of first asking the responsible special pedagogue and then principals of the targeted preschools worked well. Subsequently, pre-school teachers could work with the recruitment of children. The teachers were positive to inform parents and collect consent from them and the children. The teachers also fully completed the assessments, except for one teacher who left the employment at the time of assessment and did not complete all scales in ABAS-II for teachers. All children completed all assessments in KaTid-Child, except for one child INS that did not complete the second assessment. Three occasions for assessment were planned but this child was missing due to illness at all three.

Objective 2: Evaluation and refinement of data collection procedures and outcome

The KaTid-Child assessment lasted from 30 to 40 minutes for each child. All children but one INS child, at t1, could participate in the assessment with KaTid-Child. For this child, the assessment was performed on two occasions using the time log to increase motivation. The teachers and parents needed verbal information on how to fill in the ABAS-II. The ABAS-II was perceived as time-consuming for both pre-school teachers and parents. Still, all except one teacher managed to complete the forms. This teacher, responsible for one group, did not complete all the ABAS-II scales at t2 as she left the pre-school shortly after the intervention period. Time-P filled in by parents seemed to be easy to understand and complete. For the children, the Autonomy scale was challenging but made easier to understand with pictures representing the statements. There was a need to explain the word leisure and relate it to the child by giving concrete examples. The first author described leisure as when the children were not in pre-school and gave examples of what to do during leisure time (e.g. play with a friend, draw, or go swimming).

The KaTid-Child was completed for all children in the four groups (n = 20) at t1. At t2, 19/20 children completed the KaTid-Child. One INS child dropped out at t2. For this child, only the first part of the KaTid-Child kit was completed. Two dates for continuing the assessment were arranged, but the child did not come to pre-school during these dates. The Autonomy scale was administered to 19 children at t1 (one lacking from group 4) and 19 children at t2. At t2, it was the same INS child that did not complete the KaTid-Child assessment at t2. Parents filled in Time-P for 19 children at t1 (one TD child lacking from group 3) and 17 children at t2 (one TD child lacking from each group 1, 2 and 3). Data for the Autonomy scale at t1 lacked for one TD child (group 4) and at t2 for one INS child (group 3). The ABAS-II Parent assessment at t1 was completed in all scales for 19 children, lacking all scales for one TD child (group 3). All scales for the same TD child (group 3) were lacking at t1 and t2. At t2, 17 children completed all the scales. Three TD children (from groups 1, 2 and 3) did not complete all the scales. All the scales of the ABAS-II Teacher was completed in the four groups at t1. At t2, three of the groups completed all scales of the ABAS-II. The teacher in group 2 only completed the social scale for four of the five children, lacking rating on the social scale for one TD child. From this analysis, we learned that the time log should be used, when necessary, in the children’s evaluation process to provide information about assessment duration. It is also vital to prepare for more than one data collection occasion when assessing children INS. Moreover, there is a need to explain how to fill in the ABAS-II for teachers to support the parents, and the parents should be encouraged to contact the researchers if they have questions. Finally, we also learned that it is essential to have a backup plan for the assessment performed by pre-school teachers with at least two responsible pre-school teachers filling in the ABAS-II Teacher scale.

Objective 3: Evaluation of acceptability and suitability of intervention and study

The experiences of the teachers clarified in what way MyTime was acceptable and suitable for use with pre-school children in the pre-school environment. The results from the group interview (presented in ) resulted in one theme: A simple model to facilitate everyday functioning in pre-school children, and two categories: A tool developing new abilities in preschoolers and MyTime is worth the effort to learn.

Table 2. Theme, categories, and subcategories.

A tool developing new abilities in preschoolers

Interest for time

Overall, the children showed involvement when working with MyTime. They have been positive in the practical work and the different parts of the intervention, for example, the Time Log used to show duration of activities.

The children wanted to work with it. How long can I sit for?/…/ 5:1

The children showed an increased interest also in the analogue clock.

The children asked for clocks and alarm clocks as birthday presents. 1:1

From the preschool playground you could see the [analogue] clock in the 4th-grade classroom. The children often stood there looking at the clock 5:2

The children showed a growing interest when working with time in pre-school.

I saw those who weren’t interested in the beginning, but they showed an interest after some time. 5:3

Time becomes visible

MyTime makes time visual and therefore understandable to the children. The program offers an alternative clock, a whiteboard clock

It was cool the way the dots sort of disappeared, it became so clear that time is up now. 3:1

An educational tool

The weekly schedule with different colours for the days was helpful. The children were able to keep track of activities throughout the day as well as the days of the week.

Because they know the color of the day. 5:4

The pre-school staff described the whiteboard clock as a tool that can be used to more easily explain when activities will take place during the day. They emphasised the importance of being able to help the children to understand time.

Some of them ask over and over again: When are we going home? And it became easier for them to tell when they could look at the board [whiteboard clock]. So they didn’t need to ask so often. 4:1

After the intervention period, the whiteboard clock was returned. At that point the importance of it became very clear, as it became more difficult for teachers to explain the passage of time in an understandable way to the children.

Íve noticed that they ask more frequently now that there isn’t a clock [whiteboard clock]. Sometimes they can ask ten times or so in five minutes/…/ 4:2

Contributes to time perception

Working with the program contributed to the children’s ability to process time. Having the possibility to see the time passing gave them not only a feeling for the duration of different activities but also of understanding how much time is left before an activity starts or ends.

This is not about learning to tell time in the typical way, it is about having a sense of the passage of time. 1:2

The children communicate about time

When using the whiteboard clock, it was possible for the children to communicate about time with both other children as well as adults. Time became visible, therefore the children could compare and reason about it.

Sometimes there was a group of children standing in front of the clock (whiteboard clock) talking to each other and comparing. It would have been interesting to record that, what the children were talking about. 2:1

Inspiration

The pre-school staff expressed a fascination with their experience of how the children think about time, of how important time is. For example, children made comments, when measuring time, on different activities taking different amounts of time.

/…/how it could be different when we walk to the forest from when we went to the mine. 3:2

Participation

The children participated in all parts of the program. When measuring the duration of an activity, children could cooperate. One of the children would be responsible for carrying the bag during the activity and another child could help reading the display when the activity was finished. Being responsible made the children feel proud and happy when they succeeded.

This is positive and exciting. I’m supposed to do something, Ím in focus. They have been happy about doing things like carrying the Time Bag. 1:3

The information given to the children through measuring time was important to them. The teachers noted that, for example, all participating children valued knowing the duration of an activity.

The children let the magnets remain. No one took them down. Only children from other groups poked around with the magnets – the ones who didn’t understand. 2:2

Development of abilities in other areas

The pre-school staff developed uses in areas other than developing time skills. As a result of this, the children developed abilities useful for preparation for elementary school.

/…/it became a kick-start in the development of reading and writing. 1:4

We added to the structure. Both a picture and some text. After that we also brought in digits. One thing came after the other. They would look at the picture and see how its name was spelled, and the children started to write what they saw. 1:5

Autonomy

The whiteboard clock and weekly schedule with set colours for each day have made it clear in an understandable way what’s going to happen during the day, which children and pre-school staff are present, and when it is everyone’s home time. This made the children more independent in time orientation and resulted in less questions being asked.

It became very clear, Olle didn’t came today and I go home the same time as you today. Mom, you are too early. 3:3

It was fun when they wanted us on it too [the whiteboard clock]. So they could see when we were going home. 3:4

Creates a feeling of security

Having comprehensible information about the day and what’s going to happen created a feeling of security for all children. For some children it determined how their day would be.

It’s a comfort to know when home time is, and some of them need it more than others. Some are more insecure. It influences how the day goes. 1:6

The children manage their time

All the activities the children measured were collected in their Time Books and this was used as a reference for the duration of different activities. By using this reference book, they started to plan what they were able to do within certain time frames.

Both you and I are going home in two dots. Íll have a look in my reference book [Time Book] to see how much time we have left. 3:5

Facilitates everyday activities

MyTime facilitated everyday activities at pre-school. It was easier to involve the children in an activity when they used the Time Log and decided in advance how much time to allocate to each activity. In activities not appreciated, the children chose the shortest possible time (a blue dot representing 5 min) and competed with the Time Log to be finished before the time ran out.

Now we are going to clean up and see how much time it takes. 3:6

Development of new methods in pre-school

The pre-school staff thought that MyTime is a positive way of working with pre-school children. They wished other pre-school staff could have access to this tool.

I would like to integrate this. To work with time. It should be integrated. 1:7

MyTime is worth the effort to learn

A new way of thinking

Working with the program required a new way of thinking about working with time in pre-school. It was a difference between the ordinal analogue clock and the whiteboard clock the teachers hadn’t seen before.

It felt interesting but also a little difficult, how are we going to manage this? You mentioned a clock, but this isn’t a circular one, but a straight or square one. 1:8

Challenges

Before the intervention began, there were concerns about the practical work and the different pieces of material.

I was thinking about it, wondering how this was going to work, until I saw it. 1:9

The pre-school staff worried about the possibility of extra work that could be time consuming.

It felt hard at first, how are we going to have time for this, I thought. 5:6

Sometimes the pre-school staff experienced stress that was related to the group of children.

Sometimes it could be stressful to fill in the Time Book. It depended on the children in the preschool group. 3:4

Requires new knowledge

MyTime provided an opportunity for pre-school staff to develop new skills. The experience they gained during the intervention period facilitated the practical work.

Measuring time went well. It was a bit difficult the first year/./. It’s much easier now that we have some experience and know how to do it. 1:10

Facilitating strategies

Routines for documenting was helpful in the practical work with the children.

We got into a routine [filling in the time book]. After lunch we sat down on the carpet and handed out the books. There was no stress then, and we could take the time it needed because afterwards we were just supposed to go outside 5:7

It helped to establish a flow in the practical work when pictures of different activities to measure were prepared in advance. This made it easy for pre-school staff or children to pick an activity.

Everything was prepared. We put pictures of different activities on the wall. Then they could choose the picture to be measured that day. Everything was ready ahead of time. 5:8

New insights

Pre-school staff described how working with the program gave them new knowledge of how easy it could be to facilitate pre-school children developing a sense of time. They would have liked the opportunity to work with it for a longer period.

You feel therés so much more you want to give the children with this material. It is really easy to use. Íve started to think in dots too. 1:11

Pre-school staff related parents’ comments that they had expected too much from their 5 or 6 year old child when it came to their ability to understand and manage time.

As a parent I have demanded far too much. 3:7

The validity of the qualitative results is strengthened by the following procedures. We analysed transcribed material based on Malterud [Citation42] with illustrations of citations, which enhances the trustworthiness and credibility of the analysis. We first verified that all teachers and childcare workers participating in the group interview had worked for 8 weeks with the MyTime intervention program and ensured credibility by using a structured interview guide. There was a high consensus in the group of teachers; however, group pressure is always a possible bias in group interviews. Second, the credibility of the data was established by triangulation by the first, second and third authors. In addition, the first and second authors’ extensive experience as occupational therapists in child habilitation and their theoretical knowledge from the field enabled flexibility in the analysis and sustained credibility. The third author, a psychologist, has extensive experience in everyday functioning and participation in pre-school children. Conformability was achieved by carefully describing the data collection and analysis procedure enhanced with citations. Dependability was provided by using an interview guide with questions about teachers/childcare workers' experiences of the intervention material and the children working with the intervention. This approach strengthens the connection between the results and the study aim. Transferability was obtained by including all teachers who received education in the intervention material and applied it for 8 weeks with children in pre-school groups and by describing the participants' characteristics by their occupation.

We learned from the teachers that the use of the intervention program required a new way of thinking but that they thought it was worthwhile to provide this kind of training for the pre-school children. Outwardly, it seemed time-consuming, but they resolved this issue by preparing activities to measure in advance and establish routines. For example, the children could complete their Time Books after the lunch break while the teachers completed their logbooks. The teachers experienced the logbook as too challenging to use and remembering all the names of the intervention parts. Therefore, the logbook was revised in spring after the first intervention period (groups 1 and 2) and would now include a picture beside the name of the different parts of the intervention. This change resulted in more data from the teachers during the autumn intervention (groups 3 and 4). During the intervention the need for method support decreased. The frequency of the given intervention during the 8 weeks is shown in . Some data are missing even if the intervention part was used. Missing data applies to group 1 that used the quarter-unit watch to do the time book measurements but did not report it in the logbook. Groups 1 and 4 did not report the use of the timecard. Groups 1 and 2 missed out on reporting the use of the Whiteboard Clock, although it was used daily to let the children know the time to go home. Groups 3 and 4 did not report the use of the time log. The children’s time book measurements were calculated and then compared to the frequency of the time book filled in by the teachers, showing that the children measured time more than was reported in the logbook.

Table 3. Intervention frequency over the entire period registered in the Logbook by teachers.

Objective 4: Evaluation of resources needed for managing the study and intervention

The first and second authors' workplaces provided adequate space, financial and technological resources. All intervention material was provided for free during the study. The first author who assessed the pre-school children with KaTid-Child and educated the pre-school staff in the intervention had adequate expertise in KaTid-Child and the intervention MyTime. During the education, a psychologist from the habilitation centre explained for the pre-school staff how to fill in the ABAS- II form. To fully implement the intervention, the first author was available giving method support when needed during all eight weeks for intervention.

Objective 5: Preliminary evaluation of the children's responses to the MyTime

The pre-school teachers documented the given intervention's frequency for all four pre-school groups in logbooks. These data are presented in .

TPA in pre-school children

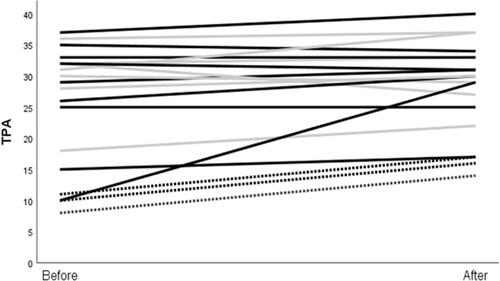

For the 5-year-old TD children (n = 83), a mean raw score of 30 (SD 6, range 24–36 is the norm value); for 6-year olds (n = 115), the mean raw score was 37 (SD 7) [Citation43]. For the INS children in this study, the highest raw score value was 17 at baseline. In total, 13/19 children that completed assessment t1 and t2 increased their TPA as measured pre- and post-test with KaTid-Child after the 8-week intervention (). We used descriptive statistics to determine change pre- and post-intervention. For ten of the TD children, the range in raw scores increased (range 1 to 19). For two TD children, TPA remained unchanged; for four TD children, the range in raw scores decreased (range 1–5) after the intervention. TPA increased for the three INS children (range 4–6 raw scores). TPA baseline levels were generally lower in the INS children () (n = 3, median raw score = 10) compared to TD children (n = 16, median raw score = 32.5).

Everyday functioning in pre-school children

Everyday functioning was measured pre- and post-test with ABAS-II, the Autonomy scale and Time-P.

ABAS-II subscales:

Social scale: three INS children were rated low by teachers at t1, but these ratings increased at t2. TD girls were rated higher in the social scale by the teachers than by the parents.

Conceptual scale: three of the four INS children increased their conceptual skills at t2 based on the parent ratings (for one INS child, there was no change). The TD boys were rated higher by the parents, whereas the TD girls were rated higher by the teachers.

Practical skills: two of the INS children increased their practical skills from t1 to t2 according to the teacher ratings. TD girls were rated higher by the teachers than by the parents.

In the General Adaptive scale the teachers rated the TD girls higher than the TD boys and INS children. Still, two INS children showed an increase from t1 to t2, according to the teachers. In the General Adaptive scale three INS children increased from t1 to t2 as rated by the parents.

Autonomy scale: The TD girls decreased from t1 to t2 in the Autonomy scale, whereas the TD boys increased. At t1, one INS child rated relatively high with a small decrease at t2. Another INS child rated lowest in the group at t1 but increased at t2.

Time-P: Data from Time-P showed an increase in parent rated daily time management from t1 to t2 for three INS children. One INS child was rated relatively high by the parent (in the range of TD children’s ratings) at t1, but the parent’s rating decreased at t2.

Expressions from the pre-school children

The children were overly optimistic when working with MyTime. They ranked the Whiteboard Clock highest and valued seeing when it was time for them or a friend to go home. They appreciated measuring time and documenting it in their Time Books because that way they could easily see the duration of different pre-school activities.

Discussion

In this study we investigated the feasibility of a study process including the intervention MyTime in pre-school children with and without INS in the pre-school context. According to Eldridge et al. (2016) all parts of the planned RCT should be implemented, evaluated and presented in a feasibility study but on a smaller scale [Citation32].

The feasibility study showed that it was effective to recruit preschools with children INS via a special pedagogue in the municipality who knew which preschools had children INS matching the inclusion criteria. For the upcoming RCT, the recruitment of children INS must be planned over at least 4 years as there are few children INS integrated in each pre-school in Sweden [Citation12]. This will also make the whole study process manageable within existing resources for the research team. It also showed that it was possible to let the pre-school teachers distribute ABAS-II and Time-P. This way, parents and children can hand in written consent and assessments to the teachers, instead of sending them by mail to the research team and thereby reduce the dropout rate. To receive useful data, it is essential to inform teachers and parents of how to fill in the ABAS-form. More than one pre-school teacher needs to be responsible for filling in the form for optimising completed forms of the assessments.

To increase the children’s energy and motivation to finish the whole the assessment it could be suitable to use the Time log to clarify the time duration of the assessment situation. It is also important to plan for more than one assessment occasion with children INS since their focus and concentration might be more limited [Citation25–27]. Also the use of pictures for the statements in the Autonomy scale and during the interview with TM facilitated the communication and made the questions more understandable.

The intervention was completed in all four participating pre-school groups. The education and the method support probably facilitated the intervention implementation [Citation33] and its sustainability. The fact that the teachers over time seamed to become more independent, the need for method support decreased. This indicates that, the teachers had internalised the knowledge in how to use the whole concept. The intervention material seamed self-instructive and easy to use. For example the logbook used by the teachers was illustrated with pictures, so the teachers knew what part of the intervention to use and document. Encouraging the teachers to implement the intervention within the ordinary activities in the pre-school group may facilitate sustainability. Also, all children in the group participated in the intervention, regardless if taking part in the study which may increase intervention acceptability as the pre-school teachers don’t have to allocate extra time to plan for other activities for non-participating children. Eight weeks of intervention seemed to be manageable and enough time for the pre-school teachers to fully implement the intervention. It was however important to guide the study and intervention by providing method support via phone calls or visits when needed during all 8 weeks of intervention. It was also necessary to collect information about facilitators and obstacles and what will be needed to provide for a sustainable implementation of the method.

Most children increased in TPA during the intervention, including the INS children, indicating that the intervention facilitated TPA. Both INS and TD children were included in this study investigating the intervention's suitability for inclusive pre-school settings [Citation12,Citation44]. MyTime seems to work for all children in the pre-school environment. Providing an intervention in children’s daily environment enhances the children's possibilities to improve their everyday functioning [Citation3]. When giving the intervention to a whole group, the INS children are not specifically in focus and thereby not stigmatised. The program is also easier to implement for the teachers provided that the whole pre-school group can be included.

The teachers experienced MyTime as a simple program that facilitates everyday functioning in pre-school children. They thought it was worth the effort to learn and suitable for developing new abilities in the preschoolers’. MyTime has successfully been used in special schools [Citation30]. According to the teachers' experiences, this study adds that MyTime can also be useful in pre-school ages. This finding is encouraging and in accordance with previous studies establishing that training TPA and daily time management can help school-age children with ADHD [Citation7,Citation8].

The participating children's parents perceived an increase in the children’s conceptual skills after taking part in the intervention, including better communication, functional academics, and self-direction. The increase in the parent ratings in these functions indicates a transferral of pre-school skills to the home environment. Additionally, there was a small increase in the subscale general adaptive composite. It is known that difficulties in TPA affecting everyday functioning could have considerable adverse effects on children’s school readiness [Citation4–8,Citation45]. There was a distinct difference between TD and INS children in TPA at t1. This finding agrees with earlier research indicating that children with disabilities often are 1 to 3 years behind in TPA compared to their TD peers [Citation2,Citation23,Citation24]. The current results show that including children with INS is useful in identifying those who can benefit from the TPA intervention. This study also demonstrates that TPA problems are observable and can change already at pre-school age. It also indicates that improving TPA may have an effect on everyday functioning, but further research is needed to investigate the intervention's impact on TPA.

The intervention also helped teachers to understand the importance of TPA for pre-school children’s everyday functioning. The qualitative results highlight the positive changes in pre-school children when the intervention was provided.

This is not about learning to tell time in the typical way, it is about having a sense of the passage of time. 1:2

Overall, our findings indicate that the process from recruitment to analysis of the intervention program is suitable and acceptable for children in the pre-school context. Further investigation is needed to determine the effectiveness of the program in pre-school INS children. The intervention program MyTime will therefore be evaluated in an upcoming RCT (study protocol ISRCTN85136134).

Conclusions

MyTime was feasible and acceptable with pre-school children in a pre-school context. The findings indicate that the program can increase TPA and facilitate the children’s everyday functioning as rated by parents and described by pre-school teachers. Using MyTime enabled us to detect children with difficulties in TPA already in pre-school ages. Also, the teachers experienced MyTime as a manageable program that can facilitate children's everyday functioning in pre-school. For the participating children, it was important to understand the duration and timing of activities during their pre-school day. Our conclusion for upcoming randomised studies is that the assessment and program design can be used to investigate intervention effectiveness to facilitate TPA and everyday functioning in pre-school children with and without disabilities.

Acknowledgement

The authors express our gratitude to participating children, preschool teachers and parents. The authors are also grateful to Abilia for proving the time assistive devices. Thanks to the psychologist Brita Warne for administration of ABAS and Dr. Julie Hansen for translating citations to colloquial English.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Janeslätt G, Granlund M, Kottorp A. Measurement of time processing ability and daily time management in children with disabilities. Disabil Health J. 2009;2(1):15-19.

- Janeslätt G, Granlund M, Kottorp A, Almqvist L. Patterns of time processing ability in children with and without developmental disabilities. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 2010;23(3):250-262.

- Kielhofner G. Model of human occupation: theory and application. 4 ed. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008.

- Abikoff H, Nissley-Tsiopinis J, Gallagher R, et al. Effects of MPH-OROS on the organizational, time management, and planning behaviors of children with ADHD. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48(2):166–175.

- Noreika V, Falter CM, Rubia K. Timing deficits in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): evidence from neurocognitive and neuroimaging studies. Neuropsychologia. 2013;51(2):235–266.

- Smith A, Taylor E, Rogers JW, et al. Evidence for a pure time perception deficit in children with ADHD. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2002;43(4):529–542.

- Wennberg B, Janeslätt G, Kjellberg A, Gustafsson PA. Effectiveness of time-related interventions in children with ADHD aged 9–15 years: a randomized controlled study. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017;1-14.

- Abikoff H, Gallagher R, Wells KC, et al. Remediating organizational functioning in children with ADHD: Immediate and long-term effects from a randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2013;81(1):113–128.

- WHO. International classification of functioning, disability and health ICF. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020.

- Janeslätt G, Granlund M, Alderman I, Kottorp A. Development of a new assessment of time processing ability in children, using Rasch analysis. Child Care Health Dev. 2008;34(6):771-780.

- Janeslätt G. TIME FOR TIME; Assessment of time processing ability and daily time management in children with and without disabilities [PhD Doctoral]. Stockholm: Karolinska Institutet; 2009.

- Nilholm C, Almqvist L, Göransson K, Lindqvist G. Is it possible to get away from disability-based classifications in education?: an empirical investigation of the swedish system. Scand J Disabil Res. 2013;15(4):379-391.

- WHO. International classification of functioning, disability and health: children and youth version: ICF-CY. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007.

- Sköld A, Janeslätt GK. Self-rating of daily time management in children: psychometric properties of the Time-S. Scand J Occup Ther. 2017;24(3):178-186.

- Socialstyrelsen. Rekommendation gällande användning av ICF i relation till ICF-CY 2019. Available from: https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/globalassets/sharepoint-dokument/dokument-webb/klassifikationer-och-koder/icf-rekommendation-anvandning-av-icf-i-relation-till-icfcy-2019.pdf.

- WHO. ICF Update Platform 2020. [cited 2020 2020-11-15]. Available from: https://extranet.who.int/icfrevision/nr/loginICF.aspx.

- Lillvist A, Granlund M. Preschool children in need of special support: prevalence of traditional disability categories and functional difficulties. Acta Paediatr. 2010;99(1):131–134.

- Andersson AK, Martin L, Brodd KS, Almqvist L. Predictors for everyday functioning in preschool children born preterm and at term. Early Hum Dev. 2016;103:147-153.

- Harrison PL, Oakland T. Adaptive behavior assessment system ABAS-II svensk version. 2nd ed. Stockholm: Pearson; 2008.

- Almqvist L, Granlund M. Participation in school environment of children and youth with disabilities: A person-oriented approach. Scand J Psychol. 2005;46(3):305-314.

- Rosenberg L. The associations between executive functions’ capacities, performance process skills, and dimensions of participation in activities of daily life among children of elementary school age. Appl Neuropsychol Child. 2015;4(3):148–156.

- Labrell F, Câmara Costa H, Perdry H, et al. The time knowledge questionnaire for children. Heliyon. 2020;6(2):e03331.

- Forer RK, Keogh BK. Time understanding of learning disabled boys. Except Child. 1971;37(10):741–743.

- Owen AL, Wilson RR. Unlocking the riddle of time in learning disability. J Intellect Disabil. 2006;10(1):9–17.

- Persson M, Janeslätt G, Peny-Dahlstrand M. Time-processing abilities and daily time management in children aged 10–17 with spina bifida. Journal of Pediatric Rehabilitation medicine. 2017.

- Isaksson S, Salomäki S, Tuominen J, et al. Is there a generalized timing impairment in autism spectrum disorders across time scales and paradigms? J Psychiatric Res. 2018;99:111–121.

- Janeslätt G, Kottorp A, Granlund M. Evaluating intervention with time aids in children with disabilities. Scand J Occup Ther. 2014. DOI:https://doi.org/10.3109/11038128.2013.870225

- Åberg K. Manual för Min Tid; verktyg för att undersöka, förstå och hantera tid [Manual for My Time; tool for examining, understanding and managing time]. Abilia; 2012.

- Arvidsson G, Jonsson H. The impact of time aids on independence and autonomy in adults with developmental disabilities. Occup Ther Int. 2006;13(3):160–175.

- Janeslätt G, Wallin Ahlström S, Granlund M. Intervention in time processing ability, managing one’s time and autonomy in children with intellectual disability aged 10–17 years, a cluster randomised trial. Aust Occup Ther J. 2018. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1630.12547

- Tickle-Degnen L. Nuts and bolts of conducting feasibility studies. Am J Occupat Ther. 2013;67(2):171–176.

- Eldridge SM, Lancaster GA, Campbell MJ, et al. Defining feasibility and pilot studies in preparation for randomised controlled trials: development of a conceptual Framework. PloS One. 2016;11(3):e0150205.

- Forman SG, Forman SG, Olin SS, et al. Evidence-Based interventions in schools: developers’ views of implementation barriers and facilitators. School Mental Health. 2009;1(1):26–36.

- Orsmond GI, Cohn ES. The distinctive features of a feasibility study: objectives and guiding questions. OTJR. 2015;35(3):169–177.

- Alderman I, Janeslätt G. Manual Kartläggning av Tidsuppfattning KaTid-B [Manual to Kit for assessing Time-processing ability, KaTid] (K. s. AB Ed. version 18b ed.). Falun, Sweden: Centre for Clinical Research Dalarna; 2010.

- Sigafoos AD, Feinstein CB, Damond M, et al. The measurement of behavioral autonomy in adolescence: the autonomous functioning checklist. In: Feinstein CB, Esman A, Looney G, et al. editors. Adolescent psychiatry. Vol. 15. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1988. p. 432–462.

- Murphy J, Cameron L. Talking mats. A resource to enhance communication. Stirling: University of Stirling; 2006.

- Ferm U, Pilesjö MS, Jöborn MT. Samtalsmatta: svenska erfarenheter av metoden. Hjälpmedelsinstitutet, Sweden; 2009.

- Cameron L, Murphy J. Enabling young people with a learning disability to make choices at a time of transition. Br J Learning Disab. 2002;30(3):105–112.

- Eriksson L, Granlund M. Perceived participation. A comparison of students with disabilities and students without disabilities. Scand J Disab Res. 2004;6(3):206–224.

- Graneheim U, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today. 2004;24(2):105–112.

- Malterud K. Qualitative research: standards, challenges, and guidelines [article. Lancet. 2001;358(9280):483–4984151.

- Janeslätt G, Alderman I. Manual for KaTid-Child -version 19. Falun, Sweden; 2017.

- Ramberg J, Lénárt A, Watkins A. eds. European agency statistics on inclusive education: 2018 dataset Cross-Country report. Odense: European Agency of Special Needs and Inclusive Education; 2020.

- Langberg JM, Epstein JN, Urbanowicz CM, et al. Efficacy of an organizational skills intervention to improve the academic functioning of students with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Sch Psychol Q. 2008;23(3):407–417.