Abstract

Background

The need to support a healthy lifestyle among the population has become increasingly apparent in recent years. The National Board of Health and Welfare in Sweden has published national guidelines regarding unhealthy lifestyle habits since 2011. An instrument based on the practical and theoretical foundations of occupational therapy was developed to support the profession's unique contribution to implementing these guidelines.

Aims

The aim was to examine the utility of the instrument by investigating its implementation potential and clinical relevance.

Material and Method

Sixteen occupational therapists used the instrument in practice together with 60 clients. Afterwards, they completed a questionnaire covering questions of utility.

Result

The instrument demonstrated mostly positive dimensions of utility. The results show that the instrument seems to have a high implementation potential and is clinically relevant. It seems, for example, to support implementation of the national guidelines and to capture how a person's lifestyle habits are expressed in everyday occupations. The instrument further seems to promote people’s participation in treatment.

Conclusion

The instrument ‘Diary-based survey of lifestyle habits in everyday activities and support for the process of change’ seems promising in terms of utility. However, the scientific merit of the instrument will need to be further established.

Introduction

Unhealthy lifestyles, which increase the risk of developing noncommunicable diseases (NCD) and premature death, are today one of the biggest threats to global health. NCDs, such as cardiovascular diseases, cancers, chronic respiratory diseases, and diabetes kill 41 million people each year, equivalent to more than 70% of all deaths globally [Citation1]. The importance of healthy lifestyles has been further emphasised during the COVID-19 pandemic. Several risk factors for COVID-19 can be influenced by an unhealthy lifestyle. Experts have highlighted the importance of good habits of daily living to reduce the likelihood of becoming seriously ill [Citation2].

Supporting healthy lifestyles is also an important part of the realization of Goal 3 of the United Nations Agenda 2030, particularly goal 3.4: ‘By 2030, reduce by one-third premature mortality from non-communicable diseases through prevention and treatment and promote mental health and well-being’ [Citation3]. According to The Shanghai Declaration on Health Promotion [Citation4], societies must support healthy lifestyles by, for example, facilitating people to make healthy consumer choices and promoting social inclusion.

Since 2011 the National Board of Health and Welfare in Sweden has published national guidelines regarding the prevention of unhealthy lifestyle habits. The guidelines are based on current research and lessons of experience and include methods to counteract the four unhealthy lifestyle habits that contribute most to the overall disease burden in Sweden: tobacco use, hazardous use of alcohol, unhealthy eating habits and insufficient physical activity. In 2018, the national guidelines were updated, and their official title became: ‘Prevention and treatment of unhealthy lifestyles’ [Citation5], hereafter referred to as the ‘NG lifestyle’, where NG stands for national guidelines.

The two recommended methods in the NG lifestyle to decrease tobacco use, the hazardous use of alcohol, unhealthy eating habits and insufficient physical activity are: a) counselling and b) advanced counselling. All healthcare professionals in Sweden are considered to have the knowledge to be able to work with these two methods, but advanced counselling requires in-depth knowledge. It is a method that is theory-based; for example, Social learning theory, Cognitive behaviour theory, or Social cognitive theory according to the NG lifestyle.

In the long term, application of these methods is expected to reduce the number of people with unhealthy lifestyles, which in turn will reduce the risk of future illness and premature death.

Occupational therapy has a unique role in the prevention and treatment of unhealthy lifestyles due to its focus on the health effects of purposeful and meaningful occupations in everyday life [Citation6,Citation7]. It is in everyday occupations that unhealthy lifestyle habits are concretised. Occupational therapists use occupation-based interventions in which the dynamic relationships among humans, their occupations and the environment are central to supporting people in achieving a change in their everyday occupations [Citation8]. The overarching aim of occupational therapy is to change occupational performance and support occupational engagement to promote health and well-being [Citation9].

In terms of occupational therapy interventions aimed at changing any of the four lifestyle habits targeted in the NG lifestyle, there seems to be a lack of such interventions supported by reasonable levels of evidence. For example, we have not been able to find any articles describing how occupation-based interventions support decreased tobacco use. This is also confirmed by Ramafikeng, Galvaan and Amesun [Citation10], who found in 2019 that tobacco use has not been well documented in occupational therapy literature. Andersson et al. [Citation11], who studied women’s everyday occupations and alcohol consumption call for new preventive approaches in the treatment of alcohol overconsumption, including investigating the importance of having engaging leisure. No articles describing this could be found. Furthermore, Johannessen, Engedal and Helvik [Citation12] and Chippendale, Gentile and James [Citation13] draw attention to elderly people’s use of alcohol and how it affects, for example, the risk of falls. These authors argue that consumption should be investigated more, but no tools for this are described.

In 2018, Nielsen and Christensen [Citation14] published a review article showing that there is insufficient explanation of the role and contribution of occupational therapy to the outcomes in the treatment of adults who are overweight or obese. Conn et al. [Citation15] also point out the same shortcoming in their 2019 review. There are several articles describing studies where unhealthy eating habits are taken into account, because this is a common problem faced by occupational therapists, but the descriptions of interventions are often insufficient, and it is often not possible to distinguish the efforts that are only aimed at eating habits.

Finally, regarding insufficient physical activity, there is a large body of articles describing exercise or physical activity, often for different diagnostic groups: for example, Marik and Roll [Citation16] who show that strengthening exercises are an effective occupational therapy intervention in musculoskeletal shoulder conditions, and Siegel [Citation17], who shows that aerobic exercise is appropriate in the treatment of people suffering from rheumatoid arthritis. But, the authors conclude that few efforts are occupation-based. Programmes that include exercise or physical activities are also described as NEW-R, Nutrition and Exercise for Wellness and Recovery [Citation18] and HEALS, Healthy Eating and Lifestyle after Stroke [Citation19], but no studies describing their effect can be found. Pettersson and Iwarsson [Citation20] report in a review article regarding everyday rehabilitation for the elderly that physical activity does have a certain effect on the ability to be active, but that the result has a low degree of evidence and further research is needed.

To sum up, to our knowledge, there are no cohort studies or randomized controlled trials focussing on specified occupational therapy interventions for changing any of the four lifestyle habits defined in the NG lifestyle, with reasonable levels of evidence. As all health care professionals in Sweden should work to improve healthy lifestyles [Citation5], it is important to clarify the role of occupational therapists in health promotion and the prevention of diseases/disabilities that are presented in the NG lifestyle. If the profession wants to be a recognized part of health promotion work in society, it must take responsibility for promoting methods for implementing change in the lifestyle habits described in the national guidelines, but from an occupational therapy perspective. This means focussing on the client’s motivation, daily habits, and doing of occupations such as work, recreation, and activities of daily living in his or her unique environment [Citation21].

Working to improve healthy lifestyles as an occupational therapist assumes the use of a process for providing service to the client. According to the American Occupational Therapy Association, this process includes the following three steps: (a) individualized evaluation, (b) customised intervention, and (c) outcomes evaluation [Citation22]. Undertaking these steps provides a systematic approach to the daily work together with clients. It is important to emphasize that the process is not linear. The occupational therapist may need to move back and forth between the different steps of the process. Collection of new information may, for example, need to be undertaken when interventions are planned, and goals are concretized. Individualized evaluation means to gather information. It is the initial step in the process, and it is crucial because it influences all the other steps that follows, such as goal setting, planning, choice of intervention, etc. The evaluation can be achieved by using different standardized procedures, such as interviews, observations, and self-assessments. A diary-based instrument, a self-assessment, capturing what a person does during the day at different times, can help habits and routines to become visible to the person, which in turn can clarify the need for change. Such an instrument facilitates reflections on how patterns of daily occupations influence well-being [Citation23,Citation24].

To support the implementation of the NG lifestyle in occupational therapy, a diary-based instrument for mapping lifestyles and supporting the process of change has been developed: ‘Diary-based survey of lifestyle habits in everyday activities and support for the process of change’ (DSL), (Kartläggning av levnadsvanor under aktivitet och stöd i förändringsprocessen) [Citation25]. The purpose of the instrument is to gather information about what a person does during the day by using a diary, how the four lifestyle habits in the NG lifestyle are concretized, and how the person perceives that his/her lifestyle habits contribute to health. The instrument has a person-centred approach [Citation26] and also provides support in clarifying any need for change.

Since DSL is a new instrument, it is important to evaluate its utilization potential. According to Polit and Beck [Citation27,Citation28], the benefits of an innovation, such as testing a new instrument in practice, can be evaluated by studying three aspects of utilization: implementation potential, clinical relevance, and scientific merit.

The aspect of implementation potential includes the feasibility, transferability, and costs and benefits of the innovation. Feasibility testing addresses practical issues such as requirements for equipment, materials, and knowledge and whether the instrument is compatible with the occupational therapist’s mission and function in practice. Feasibility also refers to the necessary skills to use the instrument. The term transferability means, for example, that the instrument is useful for the client and the occupational therapist, and that the instrument is suitable in the current environment. In addition, administrative and financial aspects as well as time required for its use are factors related to transferability. Costs and benefits of the innovation include the material and non-material costs of implementing the innovation and any conceivable risks relating to the implementation. In addition, it is also urgent to evaluate the potential benefits regarding change or retaining the status quo, including staff, clients, and the organization.

The second aspect, clinical relevance, considers whether, among other things, the instrument provides support for solving problems in practice, supports decision-making, and assists in choosing appropriate interventions. The practical relevance of the instrument and the support it can offer interprofessional collaborations are also included.

The last aspect is the scientific merit of the innovation. This focuses on evaluating the quality of the available research in the actual area, including the validity, reliability, and generalizability of the results of the studies in relation to the innovation.

The aim of this study was to examine the utility of the instrument ‘Diary-based survey of lifestyle habits in everyday activities and support for the process of change’. The study focuses on the following aspects of utility: implementation potential – i.e. feasibility, transferability, and costs/benefits, and clinical relevance.

Material and methods

Description of the instrument

The DSL is designed to support the implementation and application of the NG lifestyle in occupational therapy practice. It has been developed by the second author (LH) in collaboration with 18 professional occupational therapists, at the request of the Swedish Association of Occupational Therapists, with financial support from the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare. The aim of the instrument is to elucidate what a person does during a day and how the lifestyle habits – tobacco use, hazardous use of alcohol, unhealthy eating habits and insufficient physical activity – are concretized in the doing of everyday activities. The aim is also to provide support in identifying what changes a person can envisage and how that change could be made.

The person-centred approach used in this instrument highlights the need for individual evaluations and interventions and emphasizes that the responsibility for designing the individual change plan is shared between the client and the occupational therapist. The client must be given the opportunity to express his/her views about his/her lifestyle and occupational patterns as well as what activities are important for to him/her. The role of the occupational therapist is to support the client’s participation. A shared understanding of the client’s situation enables a strong alliance and promotes the his/her engagement.

The instrument highlights the client’s doing and has taken inspiration from the theoretical foundations of occupational therapy described by, for example, Reilly [Citation29] and Wilcock and Hocking [Citation30]. The theory of doing is based on the assumption that people have an innate need to engage in occupations because health depend on it. Doing takes place within a person’s physical and socio-cultural environment and is based on what the person needs to do, wants to do, is expected to do, or is forced to do.

The DSL is a self-assessment instrument and was developed to be used together with adults. It is not focussed on any special disability and/or impairment. The DSL manual covers areas such as (a) theoretical foundations, (b) general instructions to the occupational therapist when using the instrument together with the client, (c) how to support change by means of an occupation-based approach, and d) three different forms (A, B and C) for self-assessment. Form A includes all four lifestyle habits described in the NG lifestyle (tobacco use, hazardous use of alcohol, unhealthy eating habits and insufficient physical activity), Form B includes two lifestyle habits: unhealthy eating habits and insufficient physical activity and Form C:1–C:4 comprises separate forms for each of the four NG lifestyle habits.

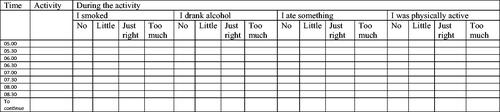

The instrument consists of three parts. In the initial self-assessment section, Part 1: Indicate your activities, each half hour during the day is documented by the client. For this purpose, the client, together with the occupational therapist, chooses one of the forms (A, B or C) and uses it to state what activities are being undertaken and then indicating whether he/she smoked, drank alcohol, ate something, and/or was physically active during the activity. If any of the four lifestyle habits are applicable a statement ‘Little’, ‘Just right’ or ‘Too much’ is noted in Part 2: Value your lifestyle habits ().

Figure 1. Form A. Including Part 1: Indicate your activities and Part 2: Value your lifestyle habits.

The client can choose to fill in a ‘Typical day’ or a ‘Specific day’. If the client chooses a ‘typical day’, he or she can fill in the form once and enter the activities that are normally performed during a day. If the client chooses a ‘specific day’, he or she reports every 30 min on what has been done. Choosing a ‘specific day’ means that it takes longer to fill in the form. Based on the client’s condition, adaptations can be made; for example, perhaps only the morning will be examined, or only one of the four lifestyle habits elucidated.

In the last part of the instrument, Part 3: Changing your lifestyle habits, the client identifies which lifestyle habits he/she would like to change, what goals can be seen, and which of these to priorities. After this, the client specifies during which activity he/she believes that a change would be possible and writes a description in more detail of how the change can be made. Finally, the date for follow-up is determined.

As shown, the instrument represents two essential points of view: the client’s perception of their lifestyle habits and need for change, and the partnerships between the client and the occupational therapist, where goals and change strategies are formulated.

The questionnaire

To determine the utility of the instrument, a questionnaire was developed and sent out to occupational therapists using the instrument in practice. The questionnaire contained questions related to two of the aspects of utility described by Polit and Beck: implementation potential and clinical relevance [Citation27,Citation28]. The questionnaire contained 54 questions and used different answer alternatives: yes/no alternatives, answer scales and short written notes. Initially, demographic information was requested.

The implementation potential included an examination of the instrument’s feasibility, transferability, and costs/benefits. Examples of questions that focus on feasibility in the questionnaire are: Is there anything that should be changed in the manual? How do you perceive your knowledge of the NG lifestyle habits? Does the instrument fit into your practice? Do you think the instrument is useful for occupational therapists? Does it reflect the theoretical and practical foundations of the profession?

Examples of questions about transferability in the questionnaire are: How long did it take for the client to fill in the different parts of the instrument? Could the client work independently with the instrument? Did the client use all the parts of the instrument? By asking whether the occupational therapists considered that the instrument was cost-effective or not, the cost–benefit perspective was examined.

Examples of questions related to clinical relevance are: Has the instrument supported you in your problem-solving process regarding elucidating the client’s lifestyle habits and need for intervention? Do you think you will use the instrument in the future? Would you recommend that colleagues use the instrument?

Procedure

The data collection was conducted during September – November 2020. The questionnaire was distributed via the survey tool ‘Survey Generator’. The Swedish Association of Occupational Therapists’ website and social media were used to advertise for participants. Nineteen occupational therapists registered their interest in participating in the study via email to the second author (LH). For introduction to the study LH made contact by email and/or telephone with each participating occupational therapist. This introduction included information about the instrument, how to use it in practice, the aim of the study, and a checklist. The idea of the checklist was to make it easier to answer the study-specific questionnaire that was distributed at the end of the study period. The participants were recommended to fill it in as they met each client with whom they used the instrument. The checklist contained question areas that occurred in the questionnaire. Only information about clients’ gender, age, and care unit was requested.

One reminder was sent out. Once the results were compiled, contact could be made with participants if any answers were difficult to clarify. However, all answers in the results section are reported anonymously.

Participants

Occupational therapists

Three of the nineteen occupational therapists, who registered their interest in participating in the study were unable to use the instrument in practice due to the prevailing COVID-19 situation during autumn 2020. Consequently, sixteen occupational therapists working in mental health, primary care, and outpatient specialist care participated in the study. All participants except one were female. Fifteen had a bachelor’s degree in occupational therapy, and two also had a master’s degree. Time as a professional occupational therapist varied between three and 35 years, with an average of 14.6 years. The number of applications of the instrument by each occupational therapist with their clients varied from one to eight ().

Table 1. Descriptions of participants: occupational therapists.

Clients

The instrument was used together with 60 adults, of whom 32 were female and 28 male. Approximately 63% of the clients were aged 30–49 years, and the most common form of care was primary care ().

Table 2. Descriptions of participants: clients.

Data analyses

Demographic and quantitative data collected via the questionnaire were analysed using descriptive statistics (frequency, percentage, median and range). The short -written notes were compiled and notes with the same intention were clustered. Quotes are used to illustrate response content.

Ethical concerns

This study was not associated with ethical risk criteria in Sweden. The study was performed according to the ethical guidelines and recommendations for good research practice published by the Swedish Research Council [Citation31].

Results

Implementation potential

Feasibility

Of the occupational therapists, 13 (81%) considered that they had fairly good or very good knowledge of the NG lifestyle before the study started, and all except one stated that they include lifestyle habits in their practice. Various forms of screening tools directed by the regional health and medical care authority were given as examples of how lifestyle aspects were included. Three occupational therapists stated that they had chosen to deepen their knowledge of NG lifestyle habits by retrieving knowledge from the web service offered by the National Board of Health and Welfare and/or the Swedish Association of Occupational Therapists which is referred to in the manual (theoretical foundations).

Fourteen (88%) occupational therapists stated that they consider the manual for the instrument to be easy to understand and to get started with when surveying a client’s lifestyle habits; one thought it was ‘very easy’ and one thought it was ‘difficult’. One occupational therapist pointed out that the manual needs to be modified with respect to the forms, as they are too long and detailed.

More than two-thirds of the occupational therapists (69%, n = 11) perceived that the information the client needed before they could fill in Parts 1 and 2 of the instrument was reasonable and more than 75% (n = 12) perceived that the client could most often use the scale steps’ Little’, ‘Just right’ or ‘Too much’. Difficulties arose with the scale steps if the client had problems with the use of the Swedish language. The final question in the questionnaire allowed occupational therapists to make additional comments; in these comments it also emerged that clients may have difficulty understanding the scale steps. The concepts need to be clarified better in the manual. Of the occupational therapists, 75% (n = 12) reported that the information the clients needed before they could fill in Part 3 was reasonable, and one occupational therapist reported that the clients needed an unreasonable amount of information.

To deepen their knowledge of various strategies for change using an occupation-based approach, one-third of occupational therapists have used the information and recommended literature given in the manual.

Two occupational therapists stated that there were times when it could be unethical to use the instrument. For example, the reason why the client has requested care may in some instances mean that it is inappropriate to ask about lifestyle habits. The instrument was also perceived as being confusing if the client had reading and writing difficulties or impaired cognitive ability due, for example, to depression or stroke. Furthermore, discussion of the interpretation of the scale steps can be experienced as being emotionally charged, for example, when patients have eating disorders.

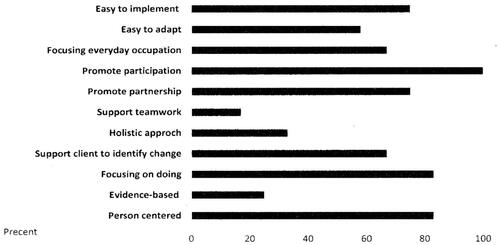

The strengths of the instrument indicated by the occupational therapists are shown in .

Strengths that are most appreciated by the occupational therapists are that the instrument promotes clients’ participation, focuses on doing and not disease symptoms, is person-centred, promotes partnerships between the client and the occupational therapist and is easy to implement. However, the instrument does not seem to promote collaboration within the team. Everyone, except one occupational therapist, stated that the instrument fills a gap in their professional toolbox and that it fits into their practice. When it does not fit, it is explained by the fact that it is too long and detailed.

Finally, regarding feasibility, occupational therapists indicate that the instrument helps them to pay attention to unhealthy lifestyle habits in their daily work as an occupational therapist, and all, except one occupational therapist considered that it reflects the theoretical and practical foundations of the profession to a ‘moderate’ or ‘high’ degree.

Transferability

It took on average 27 min for the clients to fill in Parts 1 and 2 of the instrument, with a range of 10–45 min. The time required was considered reasonable by 88% (n = 14) of the occupational therapists.

Forty-five clients chose to fill in a ‘Typical day’. Form A was used by 20 clients, form B by 22, and 18 clients chose one of the C forms. Furthermore, 48 clients filled in the instrument for ‘most all times’ of a day and 28 clients filled in Parts 1 and 2 independently without the participation of the occupational therapist. If the client chose to fill in the instrument during a visit to the occupational therapist, they filled it in together in 26 cases.

Forty-nine clients chose to work with Part 3: Change your lifestyle habits. shows how independently the clients worked with the different sections in Part 3: identification of which lifestyle habits the client wants to change, goal formulations, prioritization of goals, in what activity the change might be possible, and how the change would be made practically.

Table 3. Procedure in Part 3 of the instrument: change your lifestyle habits (n = 49).

As can be seen from the table, the degree of interaction between the client and the occupational therapist increased as the formulation of the change process progressed. They had more interaction when it came to formulating change strategies than in identifying which lifestyle habits the clients felt they wanted to change.

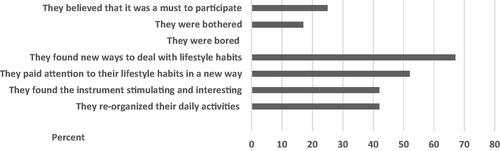

According to the occupational therapists, the clients experienced use of the instrument as rather rewarding. The use of the instrument seems to have given clients new ways of managing their lifestyle habits ().

Figure 3. Occupational therapists’ views about clients’ experiences. More than one option could be chosen.

The instrument provides certain options, and how important these options were perceived to be by the occupational therapists is shown in .

Table 4. The importance of options in the instrument*.

All the options that the instrument allows seem to be ‘important’ or ‘very important’ for the occupational therapists when applying the instrument. The opportunity to choose between different forms and to use different methods for collaboration with the clients seem to be perceived as most valuable.

Costs/benefits

Two occupational therapists stated that the instrument is not cost-effective. They reported that the effort required to gather information about how the four lifestyle habits are concretized in client’s everyday life, and how the client perceives that his/her lifestyle habits contribute to health, do not correspond with the benefit the occupational therapist derives from the instrument. The remaining occupational therapists (n = 14) stated that they considered the instrument to be cost-effective.

Clinical relevance

As reported above, 49 clients worked with Part 3 of the instrument. Within the timetable of the study, the changes were completed for seven clients, and their goals had been achieved. For the remaining clients, the follow-up had not yet been carries out (n = 14), or showed need for further change (n = 28).

All the occupational therapists, except one, indicated that the instrument helped them to take a person-centred approach and all, except one, also stated that it captured how the lifestyle, as presented in the NG lifestyle, are concretized in everyday occupations and how clients perceive that their lifestyle habits contribute to their health.

All the occupational therapists considered the instrument to provide support in identifying any change needs and when to formulate goals. Furthermore, 75% (n = 12) stated that the instrument provides support for choosing how the change should be made in an activity if the need for change has been identified. The instrument further facilitates documentation, according to 88% (n = 14) of occupational therapists.

The various parts (Parts 1, 2, and 3) were considered to have ‘moderate’ to ‘high’ practical relevance by most occupational therapists. One occupational therapist considered that all three parts lacked practical relevance and one occupational therapist considered that Part 2 had little practical relevance.

Interactions with the client were not affected by the application of the instrument according to 50% (n = 8) of the occupational therapists. Those who stated that the interaction had been affected provided notes such as:

“The patient is made more involved.”

“A smooth way to enter a very important area.”

“Not just yes and no questions.”

“Further conversations about the clients’ activities was facilitated.”

“It clarifies for the patient what to work with.”

All 16 occupational therapists would recommend that colleagues use the instrument, and they believe that they will use the instrument in the future.

Discussion

This study shows that DSL seems to be a useful instrument in occupational therapy practice. It supports the implementation of the NG lifestyle. It captures what a person does during a day and how the lifestyle habits – tobacco use, hazardous use of alcohol, unhealthy eating habits and insufficient physical activity – are concretized in the doing of everyday activities. It also illustrates how people perceive that their lifestyle habits contribute to their health. The study shows that the instrument seems to have a high implementation potential and is clinically relevant.

The instrument helps occupational therapists to pay attention to the NG lifestyle in their daily work and it reflects the theoretical and practical foundations of the profession. Consequently, the instrument seems to clarify the contribution of occupational therapy, and the efforts of an occupation-based intervention to support the changes in lifestyle habits described in the NG lifestyle. In previous literature, there were no support for occupational therapy interventions targeting any of the four lifestyles habits found [Citation10–20]. The findings of this utility study indicate that the instrument DSL has the potential to fill the gap in the occupational therapists’ toolbox of prevention and treatment of unhealthy lifestyles that were described in the background.

Occupational therapists seem to have the skills required to use the instrument, but if there is a need for additional knowledge, it was stated that the manual provides guidance on where such knowledge can be obtained. The manual is a support for application of the DSL. It was easy to understand and to start using the instrument.

The time required to work with the DSL is generally perceived as reasonable, although a few occupational therapists stated that it takes too long. About half of the clients who participated filled in Parts 1 and 2 independently. Part 3 was also filled in by many of the clients and many also worked with Part 3 independently.

The results indicate that, in the occupational therapists’ view, the clients consider the instrument to be applicable. Collaboration increased between clients and their occupational therapists when formulating changes in more detail in Part 3. Formulating changes to daily activities that are detailed enough to support more healthy lifestyle habits can be a challenge for many clients. Occupational therapists have the competence, for example, to break down activities into steps or actions [Citation32], and this can support the client in identifying strategies for change.

The various forms that the instrument contains seem to support the application of the DSL as well. All three versions, A, B, and C variants were used to about the same extent.

The results indicate that the instrument can help clients to pay attention to their lifestyle habits in a new way. It gives them new ways of dealing with problems with their lifestyle and they saw the survey as stimulating and as giving them ideas about how they could reorganize their activities. Most of the occupational therapist also found the instrument to be cost effective. Only two occupational therapists were of a different opinion.

The instrument seems to support the occupational therapist to solve problem in practice. It has a clear person-centredness, it promotes clients’ participation in the treatment process, e.g. everything from stated lifestyle habits during everyday activities, to indicating changes in lifestyle habits, identifying change strategies, and to clarifying follow-up. Additionally, recording the treatment is also facilitated.

All the participating occupational therapists believe that they will use the instrument in the future, and they are willing to recommend it to colleagues, even though some stated on other questions that they experienced some weaknesses in the instrument.

A weakness of the instrument is that some clients had difficulty in understanding the scale steps ‘Little’, ‘Just right’ and ‘Too much’. The manual therefore needs to be developed. It is suggested that a clearer description should be given of the fact that it is the client’s perception that is sought and that the occupational therapist must spend time examining and creating an understanding of how the client perceives the scale steps.

Another weakness to emerge is that the instrument is too extensive. One thing that may contribute to this statement is whether it is activities during a ‘Typical day’ or a ‘Specific day’ that are reported. The reason why this is highlighted is that the approaches to filling in Part 1 and Part 2 differ. If choosing a ‘Typical day’, Part 1 ‘Indicate your activities’, is carried out first, and then Part 2 ‘Value your lifestyle habits’. If, on the other hand, a ‘Specific day’ is chosen, the recommendation is to fill in the form retrospectively during the day; for example, once at lunchtime, once in the afternoon and once in the evening, and to fill in both Part 1 and Part 2 at the same time. The specification and choice of day also affects the approach, which can further affect the trustworthiness of the response. If a ‘Typical day’ is reported, the person may not remember exactly what was done during every half-hour, compared to filling in the form three to four times during a day and then at the same time value their lifestyle habits. The choice of day may also affect validity. Is it a typical day for the person’s everyday occupations that is being reported? Although the choice of day can be perceived as rather cumbersome, it is important to keep in mind that it is the client’s opinion that is being sought. There are no right or wrong answers.

Bias due to self-reporting could be present, and the client may provide unreliable responses for a wide variety of reasons [Citation33,Citation34]. However, the manual clearly states that the instrument is intended to be used as a basis for dialogue between the occupational therapist and the client in order to clarify any need for change. In any case, the occupational therapist must judge whether the client’s values, choice to change, and goal formulations are likely to support a healthier lifestyle. If the goals, are unreasonable, for example, or perhaps risky, this must of course be raised and discussed with the client. A person-centred approach does not mean that the occupational therapist must remain silent about his or her opinion, but it must be conveyed with respect for the client and the client has the right to say no to the occupational therapist’s suggestions. One way to deal with disagreement can be to start working with more detailed objectives or to jointly decide to ‘pause’ the aspects upon which the disagreement touches and return to them later.

The reporting of activities in 30-minutes segments during the day can also contribute to the experience that the instrument is too extensive. Studies have shown that a diary method may enable an understanding of the complexity of daily occupation, but that it is gives ‘… limited information regarding the action sequences that compose an occupation and how these are distributed in time’ [Citation35]. By reporting the activities in short time periods, the hope is that the instrument will provide a more detailed picture of the complexity of everyday activities for the client than reporting each hour.

Adding more examples to the manual and illustrating the adaptation potential of the instrument will hopefully reduce these limitations. Assessing the client’s ability to participate in using the instrument is a process that must be undertaken with great professional consideration. ‘How should the instrument be applied together with this unique client?’ is one important question the occupational therapist must consider. For example, if working with all four lifestyle habits at all hours of the day, Form A, might be too extensive for the client, and maybe it is better to choose to map and work with only one lifestyle habit during the morning. The possibility of making different choices in the application of the instrument was appreciated by the occupational therapists. This provides good conditions for adapting the application of the instrument to each unique client.

This study indicates that application of the instrument may be perceived as unethical on certain occasions. It was mentioned, for example, that the instrument could be perceived as challenging for clients with eating disorders. As with all other interventions, the occupational therapist must choose interventions based on what the client wants to do, needs to do, and is expected to do. As mentioned above, application of the DSL must be undertaken with great professional awareness. This means that interventions should be designed and implemented in partnership with the client, and always be related to his/her unique everyday life and the unique experiences this provides [Citation36].

The manual contains several examples of literature that shed light on how to promote changes in everyday occupations. For example, the occupation-based ValMO-model [Citation37] (The Value and Meaning in Occupations Model), highlights three different value triads: the occupation triad, the value triad, and the perspective triad. These triads are interconnected and clarify and deepen occupation as a phenomenon. Activities that are perceived to have value and to be meaningful can give an increased feeling of health, while activities that people feel they are forced to do can lead to a negative feeling of health. Another reference is to the Model of Human Occupation [Citation21], which is an evidence-based model that explains how and why humans choose to be active in their own unique way. The model provides an understanding of why a person is motivated to participate in occupations, how habits and roles support occupations, and how ability enables occupations. The impact of the environment also has a large explanatory role in this model. There are a few interventions described concerning engagement in occupations that can be applied to support change. It is stated, for example in the Model of Human Occupation, that advising, structuring, and encouraging can be useful strategies for enabling occupational change. The models described above show how occupation-based interventions can be used to support changes in lifestyle habits. This may well be directed towards one of the lifestyle habits that are addressed in the NG lifestyle. Interventions based on these models should be considered equivalent to the recommended method of advanced counselling in the NG lifestyle. As can be seen from our study, the occupational therapists perceive that the DSL supports clients in changing their lifestyle habits and finding strategies for change. In addition, the occupational therapist can give the client guidance in this change, through partnership and applying their professional knowledge. Here, different models of occupational therapy are significant.

Methodological considerations

This was a small study with just 16 participants. This may seem like a small number, but we argue that our results are nevertheless credible. One indicator for this statement is the feedback from the 18 occupational therapists who participated in the development process, as mentioned in the section Material and methods. The development process of the DSL resulted in a similar version of the instrument that was examined in this study. The 18 occupational therapists applied the instrument in their daily work and answered what was to a large extent the same questionnaire as used in this study in the development process. Their feedback on the utility of the instrument was fully in line with the results of this study. Therefore, we suggest that our study has an acceptable degree of credibility despite the small number of participants. However, further studies must be conducted; for example, to investigate the clients who use the instrument in order to capture their perceptions of its value. Furthermore, the scientific merit of the instrument also needs to be established, referring to Polit and Beck [Citation27,Citation28], in order to determine each part of utility. For example, one alternative could be to use a longitudinal study, focussing on intra-individual change [Citation38] to determine how lasting the change is over time with the occupation-based interventions provided by the instrument compared with interventions according to the recommendations in the NG lifestyle.

Conclusion

The instrument ‘Diary-based survey of lifestyle habits in everyday activities and support for the process of change’ demonstrated mostly positive dimensions of utility. The instrument seems to have a high implementation potential and is clinically relevant. It seems to provide a contribution to clarifying the role of occupational therapy in the work to reduce unhealthy lifestyles according to the NG lifestyle.

The instrument seems promising in terms of utility. However, the scientific merit of the instrument will need to be further established.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to acknowledge all the occupational therapists who participated in the study.

Disclosure statement

A swedish version of the instrument can be downloaded free of charge from the Swedish Association of Occupational Therapist’s website.

References

- WHO. Noncommunicable diseases. Key Facts. Juni 2018. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases.

- Hamer M, Kivimaki M, Gale CR, et al. Lifestyle risk factors, inflammatory mechanisms, and COVID-19 hospitalization: a community-based cohort study of 387,109 adults in UK. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;87:184–187.

- United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals. Goal 3: Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages. n.d. https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/health/.

- WHO. The Shanghai Declaration on Health Promotion. 2016. https://www.who.int/news/item/21-11-2016-9th-global-conference-on-health-promotion-global-leaders-agree-to-promote-health-in-order-to-achieve-sustainable-development-goals.

- Socialstyrelsen. Nationella riktlinjer för prevention och behandling vid ohälsosamma levnadsvanor. Stöd för styrning och ledning [Prevention and treatment of unhealthy lifestyles] Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare; 2018. Swedish.

- Jaffe E. The role of occupational therapy in disease prevention and health promotion. Am J Occup Ther. 1986;40:749–752.

- Wilcock AA. An occupational perspective of health. Thorofare (NJ): SLACK; 2006.

- Fischer AG. Occupation-centred, occupational-focused: same, same or different? Scan J Occup Ther. 2014;21:96–107.

- Word federation of occupational therapist (WFOT). About occupational therapy. https://www.wfot.org/about/about-occupational-therapy.

- Ramafikeng MC, Roshan G, Amesun SL. Tobacco use and concurrent engagement in other risk behaviours: a public health challenge for occupational therapists. S Afr j Occup Ther. 2019;49:26–35. http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2019/vol49n1a5

- Andersson C, Eklund M, Sundh V, et al. Women’s patterns of everyday occupations and alcohol consumption. Scand J Occup Ther. 2012;19:225–238.

- Johannessen A, Engedal K, Helvik AS. Use and misuse of alcohol and psychotropic drugs among older people: is that an issue when services are planned for and implemented? Scand J Caring Sci. 2015;29:325–332.

- Chippendale T, Gentile PA, James MK. Characteristics and consequences of falls among older adult trauma patients: considerations for injury prevention program. Aust Occup Ther J. 2017;64:350–357.

- Nielsen S, Christensen J. Occupational therapy for adults with overweight and obesity: mapping interventions involving occupational therapists. Occup Ther Int. 2018;2018:7412686.

- Conn A, Bourke N, James C, et al. Occupational therapy intervention addressing weight gain and obesity in people with severe mental illness: a scoping review. Aust Occup Ther J. 2019;66:446–457.

- Marik TL, Roll SC. Effectiveness of occupational therapy interventions for musculoskeletal shoulder conditions: a systematic review. Am J Occup Ther. 2017;71:1–11.

- Siegel P, Tencza M, Apodaca B, et al. Effectiveness of occupational therapy intervention for adults with rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review. Am Jour Occup Ther. 2017;2017:71–71.

- Brown C, Read H, Stanton M, et al. A pilot study of the nutrition and exercise for wellness and recovery (NEW-R): a weight loss program for individuals with serious mental illnesses. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2015;38:371–337.

- Hill A, Vickrey B, Cheng E, et al. A pilot trial of a lifestyle intervention for stroke survivors: design of healthy eating and lifestyle after stroke (HEALS). J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2017;26:2806–2813.

- Pettersson C, Iwarsson S. Evidence-based interventions involving occupational therapists are needed in Re-Ablement for older Community-Living people: a systematic review. Br J Occup Ther. 2017;80:273–285.

- Taylor RR. (ed). Kielhofner’s model of human occupation, 5th ed, Philadelpia (PA): Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2017.

- The American Occupational Therapy Association. Acc Aug 2021. https://www.aota.org/About-Occupational-Therapy/Professionals.aspx.

- Orban K, Edberg A-K, Erlandsson L-K. Using a time-geographical diary method in order to facilitate reflections on changes in patterns of daily occupations. Scand J Occup Ther. 2012;19:249–259.

- Kennedy-Behr A, Hatchett M. Wellbeing and engagement in occupation for people with Parkinson’s disease. Br J Occup Ther. 2017;80:745–751.

- Haglund L. Kartläggning av levnadsvanor under aktivitet och stöd i förändringsprocessen [Diary-based survey of lifestyle habits in everyday activities and support for the process of change]. Nacka: The Swedish Association of Occupational Therapists; 2020. Swedish.

- Karstensen JK, Kristensen HK. Client-centred practice in Scandinavian contexts: a critical discourse analysis. Scand J Occup Ther. 2021;28:46–62.

- Polit DF. Beck Ct Nursing research: principles and methods. 7th ed. Philadelphia (PA): Lippincott; 2004.

- Polit D, Beck CT. Nursing research: generating and assessing evidence for nursing practice. 8th ed. Philadelphia (PA): Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008.

- Reilly M. Occupational therapy can be one of the great ideas of 20th century medicine. Am J Occup Ther. 1962;16:1–9.

- Wilcock AA, Hocking C. An occupational perspective of health. 3rd ed., Thorefare (NJ): Slack; 2015.

- Swedish Research Council. Good research practice. 2017. https://www.vr.se/english/analysis/reports/our-reports/2017-08-31-good-research-practice.html.

- Haglund L, Henriksson C. Activity-from action to activity. Scand J Caring Sci. 1995;9:227–234.

- Hill NL, Mogle J, Whitaker EB, et al. Sources of response bias in cognitive self-report items: Which memory are you talking about? Gerontologist. 2019;59:912–924. Geront.

- Althubaiti A. Information bias in health research: definition, pitfalls, and adjustment methods. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2016;9:211–217.

- Erlandsson L-K, Eklund M. Describing patterns of daily occupations – a methodological study comparing data from four different methods. Scand J Occup Ther. 2001;8:31–39.

- Arbetsterapeuter S. Etisk kod för arbetsterapeuter [Code of ethics for occupational therapists]. Nacka: The Swedish Association of Occupational Therapists; 2020. Swedish

- Erlandsson L-K, Persson D. ValMO model – occupational therapy for a healthy life by doing. Lund: Studentlitteratur; 2020.

- Grimm KJ, Davoudzadeh P, Ram N. IV developments in the analysis of longitudinal data. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev. 2017;82:46–66.