Abstract

Background

Patrolling police officers engage in different mentally, socially, and physically challenging life contexts which may affect their life and health. The aim of this scoping review is twofold, to explore life contexts of patrolling officers in the European Union, and to investigate how their lives and health are affected by environmental characteristics within these contexts.

Methods

The scoping review followed Arksey and O’Malley’s methodology and included a critical appraisal. The environmental model within Kielhofner’s Model of Human Occupation was used in the thematic analysis. The review was reported following PRISMA-ScR.

Results

In the 16 included studies, two contexts (where environments interact with persons on different levels) were discovered: the global and the immediate context. No local contexts were found. Primarily, research on the social, and occupational environments, including qualities identified in these environments were found. However, some environmental characteristics within patrolling officers’ physical environments were also discovered.

Discussion

This review contributes to the emerging research area of police officers’ life contexts, by mapping contexts and environments affecting their life and health. However, to get a deeper understanding of how officers are affected by their environments, interviewing them regarding how their different contexts affect their everyday living, would be important.

Introduction

Police officers engage in different contexts during their working day, which according to previous research have been found to affect their health [Citation1,Citation2]. Some of these contexts are shared with other professions [Citation3–5]. However, police officers additionally face challenging situations as part of their job description and also experience violence, threats and harassment from the public [Citation6–9] more frequently than average professionals [Citation10]. For example, in the Swedish police force, 36% of work-related accidents are related to threats and violence [Citation10]. Additionally, international research shows that exposure to threats and violence at work has been found to affect police officers’ health [Citation2,Citation7,Citation11]. And, work-related injuries could result in psychological stress if occurring regularly [Citation12].

Furthermore, physical environmental characteristics such as wearing body armour [Citation13] or sitting in a patrol car [Citation14] have been found to impact patrolling police officers’ health. Additionally, taking their work issues home has shown to be a common pattern for police officers [Citation15], also affecting their private lives [Citation16,Citation17]. This indicates that the demands of work and private lives are important environmental characteristics affecting the health of police officers [Citation18].

To summarise, the environmental characteristics influencing patrolling police officers, including physically or mentally stressful contexts, and occupations at work, may ultimately result in poor health for many patrolling police officers [Citation12,Citation19,Citation20]. Thus, the contexts and environments of patrolling police officers warrant further investigation. By locating studies on patrolling police officers’ contexts and environments, using theories within occupational therapy, environmental characteristics affecting patrolling officers’ life and health can be found and synthesised. This review defines a patrolling police officer as a uniformed officer engaged in patrol duty while being in daily communication with the public. All while patrolling certain areas on foot or in a vehicle, while also keeping the public safe and upholding the law [Citation21,Citation22].

Defining life contexts using theoretical models within occupational therapy

The importance of the environment to individuals has been a crucial part of occupational therapy since the profession was established [Citation23]. In recent decades, there has been a shift towards more ecological conceptual frameworks [Citation24–26] in which the individual is intertwined with her environment, operating within different contexts, encountering environments and environmental characteristics. Contexts and environments are viewed as equally crucial as the person, when identifying what influences a person’s occupational life [Citation27,Citation28].

Thus, every person’s life context is based on a system of contexts and environments, consisting of their own set of environmental characteristics. Even though the available conceptual frameworks may differ in terms of focus area and label systems, they all include similar areas and concepts (see, for example, Townsend and Polatajko 2013 [Citation28], Christiansen and Baum 2015 [Citation29], Taylor 2017 [Citation30], and Law et al. 1996 [Citation31]). Additionally, several theories have been developed in different professional fields that explain the interrelationship between person and context, and often also the relationship to health (see, for example, Bronfenbrenner 1977 [Citation32], Dunn et al. 1994 [Citation26], Townsend and Polatajko 2013 [Citation28] and Wicker 1984 [Citation33]).

For example, the environment is considered to be multi-layered, both natural and constructed, interacting with people as they perform their occupations in different ways and places. In this article, environments are referring to physical, social and occupational components of one’s contexts. These life contexts, including both contexts and environments, will also change over time. Even though different environments are discussed separately, in reality, they are inseparable as they continuously affect each other, as well as the person, occupations, and occupational performance [Citation26,Citation28–31,Citation34]. For example, Iwama [Citation35] has described the environments in a person’s life as ever-changing riverbanks affecting the life flow in a river, in which the river itself is the person’s life and well-being, taking a complex journey through time and space [Citation35].

To further grasp the conceptualisation of environments, Fisher, Parkinson and Haglund [Citation36] presented a conceptualisation of environments within the theoretical framework of Kielhofner’s Model of Human Occupation (MOHO) [Citation30]. By applying the theories of Bronfenbrenner [Citation32,Citation37] this conceptualisation shows a transactional relationship between the person and her environments (physical, social and occupational). The model is visualised multi-levelled since the environments also exist in an immediate context (for example, home or work), local context (for example, community or neighbourhood), and global context (for example, laws and policies) and there is a continuous dynamic interaction between the different levels that has an impact on a person’s life. In addition to these contexts, other factors such as time, economic, political, cultural (cuts across all contexts in all environments), geographical, ecological and social factors, also influence a person’s occupational life [Citation36].

Fisher, Parkinson and Haglund [Citation36] also offer an explanation as to how the environments influence occupational participation by comprising different environmental characteristics (components and qualities). For instance, the environmental components comprise spaces and objects (physical environment); relationships and interactions (social environment); and occupations and activities (occupational environment), together with overarching contexts (such as cultural values and practices, as well as economic and political influence) [Citation36]. The three environments also contain qualities, for example, the physical environment includes the availability of spaces and objects; the social environment includes the availability of people and relationships, emotional support, etc; and the occupational environment includes, for example, occupation and activity choices, time elements and flexibility [Citation36]. These environmental characteristics interact with each other and influence the person [Citation34,Citation36], and are also considered key elements to the process of change [Citation36].

Environmental characteristics impacting police officers’ life and health

Police officers’ environments consist of high stress and high strain contexts [Citation1,Citation3,Citation38], which have been found to affect both their health [Citation2], but also their private life [Citation39]. Deschênes [Citation40] defined the environmental characteristics affecting the health of officers, as socioeconomic, organizational and personal factors. Socioeconomic factors include budgetary contexts and social pressure [Citation11,Citation40]. Organizational factors comprise police culture, leadership issues and interpersonal trust [Citation11,Citation40], low work-related social support and high job strain [Citation41], high job demands [Citation11], or a lack of communication or support at work [Citation42]. Personal factors include a sense of self-efficacy, emotional skills and disillusionment regarding the job description [Citation40].

Police officers are also more exposed to traumatic and stressful contexts than many other occupational groups [Citation10], which affect both their physical and psychological health [Citation2]. These traumatic and stressful contexts are not only related to health issues such as cardiovascular disease, burnout, Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), and sleep disorders [Citation2,Citation43–45] but also to dysfunctional behaviour [Citation46] such as problematic drinking [Citation47–49], hyper-aggressiveness and violence both on and off duty [Citation46,Citation50].

Thus, police officers’ health is affected by multiple environmental characteristics in different environments and on diverse contextual levels [Citation40], which according to a previous review warrants further investigation when researching police officers’ health [Citation2]. Additionally, Abdollahi [Citation51] found that the reasons why police officers experience poor health are ambiguous, suggesting that intra-personal, occupational and organizational reasons explain some of the health consequences [Citation51]. This stresses the need for more knowledge regarding the health of police officers by investigating their life context. It is also the reason why Abdollahi [Citation51] suggests that to better comprehend the complex nature of police officers’ ill-health, researchers should include conceptual frameworks to offer explanations as to the origins of the health issues [Citation51]. Hence, studying the environments and contexts, for example, home, work, community, and laws and regulation, of patrolling officers, to implicate what constitutes the health of patrolling officers, is important. Thus, the aim of the present study is twofold, to explore life contexts of patrolling police officers in the European Union (EU), and to investigate how their lives and health are affected by environmental characteristics within these contexts.

Methods

The study commenced on 5 May 2020 with a preliminary search to identify the research field and refine the search string. A protocol was created, following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) guidelines [Citation52], where the guidelines were applicable for a scoping review. The protocol was registered with OSF, a register for scoping reviews [Citation53], and it was also submitted to a journal prior to data extraction [Citation54]. Any amendments to the protocol have been reported in this manuscript, while major changes were entered into the OSF registry [Citation53]. Ethical approval was waived as the scoping review used publicly available scientific literature.

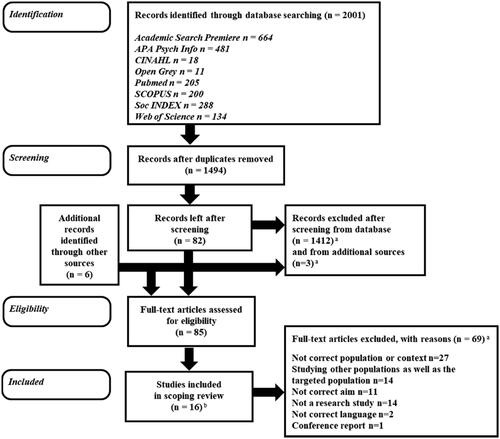

Arksey and O’Malley’s methodology [Citation55] was used to conduct the scoping review, following the first five stages. It is the most influential framework for conducting scoping reviews and has been widely used and refined since it was first created [Citation55–58]. The review was also performed in line with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [Citation59] with the extension for scoping reviews PRISMA-ScR [Citation60]. The process is described in a flowchart, displaying exclusion criteria for why articles were excluded. Some studies were excluded for more than one of these reasons, however, as soon as one criterion was met the study was removed, see .

Figure 1. Flowchart according to PRISMA-ScR. aStudies that did not match inclusion criteria were excluded when one exclusion criteria was met. bThree of the included articles came from our personal library (other identified sources) and the rest from databases.

Stage 1: Identifying the research question

The Population, phenomena of interest, Context (PICo) search strategy [Citation61] was used to formulate the search string, see . The search strategy used free-text words, together with the Boolean strategies ‘AND’ and ‘OR’. An example of the full search string for the EBSCO databases is included in the OSF registry [Citation53].

Table 1. Identifying the research question and identifying and selecting relevant studies.

Stage 2: Identifying relevant studies

The search was conducted using eight different databases (see ) and six potentially relevant articles from the reviewers’ personal library that had not been identified in the previously performed search were manually included before examining ‘full texts’ for eligibility.

Once the search had been completed, all articles were systemised in RAYYAN, a web application for conducting systematic reviews [Citation62]. The publication period was the last 20 years. See for the search dates and publication periods for each search. When the search was re-run prior to completion of the analysis, no new articles were found.

Stage 3: Study selection

Studies of patrolling officers from EU countries were included. In addition, studies from other Nordic countries (Iceland and Norway) and the United Kingdom were included as well, due to the long-term cooperation system with EU countries. The exclusion criteria for the review regarding population and context are presented in .

Since the study explored different life contexts related to the occupational role of patrolling police officers, no restrictions were applied regarding study design. However, editorials, protocols and letters to the editor were excluded. Grey literature in the form of research reports, were included to reduce publication bias, and enhance our comprehensibility of the research field [Citation63]. Hence, a specific grey literature database was searched (See ). Since the research team lacked the resources to support the translation of data, articles written in any other language than English, Swedish, Danish or Norwegian were excluded.

One reviewer (EGV) performed the search and removed duplicates of the search results. Titles and abstracts were then screened against the eligibility criteria by two separate reviewers (EGV and UN). The reviewers were blinded to each other and any study generating ‘uncertain’ to the eligibility criteria as well as the reasons for excluding the articles, prompted a discussion between the two reviewers. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion and no third party (KG) was needed in the final decision-making. For one article, the authors of the study were contacted for clarification regarding the admissibility of the study. As the last step, the six manually added articles were included.

After comparison and agreement of the first screening process, the full texts were obtained and examined for eligibility by one reviewer (EGV). Another reviewer (KG) randomly selected and checked 10% of the full texts for consistency. No discrepancies were found. Thus, no third party (MG) was required to make the final decision. A flowchart of the entire process, from identifying relevant studies to the inclusion of the final 16 articles in the scoping review, is presented in .

Before starting the data extraction, critical appraisal was performed by two reviewers (EGV and MG) blinded to each other. The Mixed Method Appraisal Tool (MMAT) [Citation64] was used, which evaluates studies using qualitative, quantitative randomized controlled, quantitative non-randomised, quantitative descriptive, and mixed-methods study designs. It has been used in critical appraisals globally and deemed valid in content, and reliable [Citation65,Citation66]. MMAT was chosen due to the possibility to assess many different study designs with the same instrument. Any lack of consensus regarding the critical appraisal was resolved through discussion. Owing to the consensus in our discussions, no third party (KG) was required to make the final decision. Critical appraisal was considered when conducting the last part of the analysis, hence included in the result of the review.

Stage 4: Charting the data

After the selection and critical appraisal of the studies, the data extraction began by charting the data. The data extraction sheet was designed by two reviewers (EGV and MG) and checked by a third reviewer (KG), pre-piloted by two reviewers (EGV and KG), and slightly revised afterwards (EGV and MG). The following data were extracted: publication year, title, authors, type of study, the aim of the study, method of analysis and PICo.

One reviewer (EGV) extracted the data into an Excel file [Citation67] and, out of 16 articles, four randomly selected articles were extracted by another reviewer (KG) to check for discrepancies. Any discrepancies were addressed through discussion between the two reviewers. Owing to the consensus in our discussions, no third party (UN) was required to make the final decision. However, two articles had insufficient data regarding age and gender. Thus, the authors of the studies were contacted for clarification, and additional information was received for one article.

Stage 5: Collating, summarising and reporting the results

The analysis was conducted by one reviewer (EGV) but discussed with all the other reviewers regularly. The descriptive characteristics were analyzed and collated in tables. Also, to locate complex multi-layered dimensions of life contexts, clusters were created by sorting articles according to life contexts in MOHO [Citation36]. The clusters were then grouped into both contexts and environments to identify gaps in the literature. This was undertaken using data from the extraction table (‘PICo Interest of phenomena’).

Thematic analysis according to Clark and Braun [Citation68] was used to identify environmental characteristics of the different environments and contexts. The coding was first conducted inductively but sorted deductively into themes using the environmental qualities concepts in MOHO [Citation36]. Environmental components (for example, time, space, objective or social interaction) from MOHO [Citation36] are not included in the analysis, since they were only used to describe and explain the study setting or participant characteristics in the articles. Thus, our thematic analysis only focussed on the environmental qualities identified. These qualities were visualised in a multi-layered figure, presenting the life contexts of patrolling officers in the EU, which is the contexts, environments and environmental qualities located in all the data.

All stages were conducted with the help of MAXQDA 2020 [Citation69] and Word [Citation70] to aid the process of coding and sorting the articles in a structured manner.

Results

The database search yielded a total of 2,001 articles, leaving 1,494 articles after the removal of duplicates. Eighty-five articles were left for full-text reading after applying inclusion and exclusion criteria. The final review comprised 16 articles for critical appraisal and data extraction, see .

Table 2. Peer-reviewed articles’ study and population characteristics including quality assessment, as well as results on an article level.

The publication period was from 2001 to 2020, and most articles were published in 2013 or later. The articles had different research designs: one qualitative method, 13 quantitative methods and two mixed-method studies, mainly conducted in Germany, Sweden and The Netherlands (See ). also includes the population characteristics of age, sex and sample size, as presented in each article, together with the PICo ‘phenomena of Interest’ used in the review.

The life contexts of patrolling police officers in the EU

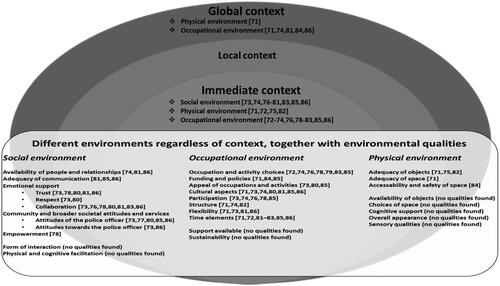

The contexts and environments located on article level, by clustering and grouping results, are shown in . Many articles touch upon several contexts and environments. However, no local contexts were found. Also, most studies of the police officers’ life contexts are described in social and occupational environments.

To answer the study’s aim, the environments and contexts were also combined in a multi-layered figure together with the identified environmental qualities showing the transactions the environments have with the officers. However, the environmental qualities are listed according to the different environments, regardless of contextual level in this model (See ).

Figure 2. The figure presents the located life contexts (contexts, environments and environmental characteristics) of patrolling police officers. At the top the contexts are presented, along with environments found within these contexts. At the bottom the environmental qualities are presented, regardless of contextual level. The qualities are arranged in order of appearance in the textual description.

The environmental qualities affecting the health of patrolling police officers

The environmental qualities found, according to the environmental model in MOHO [Citation36], are presented in italic font together with one or more examples, under the respective environment. Some environmental qualities were only slightly touched upon, while other environmental qualities were not identified at all (see ).

Physical environmental qualities

The physical environment describes the adequacy of objects [Citation71,Citation75,Citation82] related to police officers’ duty belts, safety vests, and thigh holsters, and their effect on e.g. the officers’ physical health, such as physical discomfort or musculoskeletal issues, while wearing the objects.

It also includes adequacy of spaces [Citation71], namely, the confined space in the police vehicle and the inability to adjust the seats comfortably when wearing both a duty belt and a safety vest. Also, accessibility and safety of spaces [Citation84] are considered regarding hazardous situations, where the type of physical intervention education had an impact on the physical health of police officers in violent situations.

Social environmental qualities

The social environment describes the availability of people and relationships [Citation74,Citation81,Citation86] including the availability of a supervisor within different shift systems, problems related to relationships in private life causing stress, as well as using the social network, such as venting or religion, as a strategy to cope with stressors. Another quality, adequacy of communication [Citation81,Citation85,Citation86], comprising different aspects of communication, both constructive and destructive. Having good communication between officers was considered important, and different shift systems seemed to affect how feedback was given from supervisors. Officers’ verbal use of force towards civilians was also found related to burnout, where officers who were observed using verbal force also scored significantly higher on burnout.

Emotional support revealed several different quality dimensions in this review and is therefore presented in three separate categories. For example, one category trust [Citation73,Citation78,Citation80,Citation81,Citation86] describes trust between colleagues, as well as trust in leadership, what affects commitment to the organization, and how trust is affected by different kinds of scheduling. Another category respect [Citation73,Citation80] describes the perceived lack of respect from the public, and also respectful and disrespectful treatment between officers. As well as how the officers’ work environment and perception of their work is affected by this lack of respect. The third category collaboration [Citation73,Citation76,Citation78,Citation80,Citation81,Citation83,Citation86] comprises examples of social support and collaboration between colleagues and with supervisors, as well as examples of non-functioning relationships and lack of collaboration.

Another important quality dimension was community and broader societal attitudes in which the dimension was slightly modified in this review to suit the environmental qualities of police officers. It was therefore separated into two categories in which the first category represented attitudes of the police officer affected by the environment [Citation73,Citation77,Citation80,Citation85,Citation86]: attitude towards the public or supervisors, towards the use of violence and force, opinions on police culture, and the sense of unease when enforcing rules that they felt were unfair. The second category included attitudes towards the police officer from the environment [Citation73,Citation86] in which the public’s attitude was categorised, for example, in relation to their inability to understand the importance of the police officers’ work, why they were warned or fined, or the general lack of respect. Both categories show the interaction between the community and broader societal attitudes and the police officer. As an example, the officers feel stressed when they are not understood or respected by the public, or have to enforce rules that are unfair. In turn officers with symptoms of burnout may interact with the public in a more forceful manner.

Another quality, empowerment [Citation78], was only included in one study and only minimally, i.e. touching upon the concept of organization-based self-esteem. Self-esteem was found positively related to organizational commitment, as well as mediating the organizational stressors and commitment relationship.

Occupational environmental qualities

Examples of some of the qualities of the occupational environment includes occupation and activity choices [Citation72,Citation74,Citation76,Citation78,Citation79,Citation83,Citation85] which the officers lack at work. Being a patrolling police officer include high demanding or challenging job activities that has to be performed as it is part of their job, e.g. informing persons’ relatives of deaths, or witnessing criminal offences against children. These kinds of activities affect their health, e.g. by experiencing stress or emotional exhaustion. Funding and policies [Citation71,Citation84,Citation85] includes decisions made in a global context regarding what to wear, job activities, and the education provided regarding how to handle physical interventions. Funding and policies were found to e.g. affect the physical health of officers. The appeal of occupations and activities [Citation73,Citation80,Citation85] comprises how the environment influenced e.g. officers’ view on organizational aspects differently, which job activities were appealing and not, and how the environment shaped the appeal to certain occupations at work. Cultural aspects [Citation71,Citation73,Citation74,Citation80,Citation81,Citation85,Citation86] were also of interest and touch upon the work culture, police culture, and organizational culture, as well as the cultural preferences at individual workplaces and group climates.

Participation [Citation73,Citation74,Citation76,Citation78,Citation85] includes the scope of opportunities for decision-making, or lack of decision-making, being in control of work, involvement at work, and personal accomplishment and how it e.g. affected the mental health of the officers. Examples of the quality of structure [Citation71,Citation74,Citation82] includes frequency regarding physical activity and issues such as fatigue and sleep problems related to working hours. Flexibility [Citation71,Citation73,Citation81,Citation86] comprises the possibility of doing things the way one wanted. As well as the flexibility of scheduling, and not being able to participate in decisions regarding standard uniform and equipment. It also included own flexibility and opportunities to adapt. Time elements [Citation71,Citation72,Citation81–83,Citation85,Citation86] comprises scheduling, length of service, sedentary behaviour, and engaging in physical activity both at home and at work. It also included demanding physical activity at work, and elements of not having time to do things that were necessary or expected. There were also other time factors related to different work tasks, and how this affected the officers in different ways.

Since a critical appraisal was conducted, it should be incorporated in the analysis of the results. See . Thus, we can conclude that the specific results of some studies [Citation72,Citation73,Citation75,Citation84] should be considered with caution and that the findings include 16 articles representing 13 individual studies.

Discussion

This scoping review contributes to the emerging research body of patrolling police officers’ life contexts, by mapping several important contexts and environments affecting the life and health of patrolling officers in the EU. The analysis revealed knowledge gaps, e.g. regarding the officers’ local context, including minimal research on the officers’ private lives. However, the investigated contexts and environments were found to affect the working lives and health of the officers. For example, the officers were influenced by global and immediate contexts, and while residing in different environments during their workdays, different environmental qualities supported the officer, while others did not.

The social and occupational environments were the most frequently researched. This may be explained by our social situatedness as human beings that forms our identity and occupations. For example, we fluctuate between acting as individuals or group members, although we are influenced by, for example, ethnic or gendered relations [Citation87]. Being members of social systems also influences our choices [Citation88].

The result is discussed from an environmental perspective, with environmental qualities in italic font.

Social environment

Several environmental qualities were facilitating the police officers in their social environment. For example, the importance of the availability of people and relationships, adequacy of communication, and emotional support. Our affiliations and the availability of people and relationships are key to understanding everyday behaviour and occupation, both privately and at work. Earlier research has also shown that these affiliations have the potential to affect our health and well-being [Citation87] both positively [Citation89] and negatively [Citation90,Citation91]. For example, general access to social and emotional support both on duty and off duty has been identified as being crucial for the health [Citation41,Citation92–98] of police officers.

Likewise, the importance of adequate communication possibilities when interacting with others, particularly with the public [Citation99–104], has been previously researched. Public interaction has been confirmed as causing stress among police officers [Citation77,Citation105] and it has been theorised that this stress could stem from the risk of threats and violence [Citation103,Citation104] and the use of force [Citation106,Citation107]. This may lead to health-related problems [Citation12], physical injuries [Citation108] and sickness absence on the part of the officer [Citation19].

Other environmental characteristics seemed to cause mostly stress for the officers, e.g. within the community and broader societal attitudes and services. Police officers are held accountable for the work performed while upholding the law through force [Citation109], which could lead to difficult ethical issues. Our review touched upon community and broader societal attitudes and services, which included both police officers’ attitudes towards the public and their perceptions of the public’s views of the police. Interestingly, previous research has investigated that a police officer and the public living in a community do not always share the same view regarding police-community relations [Citation110] and this is something that needs further studying, and how it affects the health of police officers.

Empowering was unfortunately only minimally researched. Empowering police officers in their challenging work situations is important and previous research among police officers has emphasised the need for supportive feedback from supervisors [Citation111]. Thus, this area needs further studying.

Previous research has shown that a good social environment is important in terms of the health and well-being of police officers [Citation2,Citation41,Citation93]. Thus, it is important to continue investigating the different qualities of the social environment, since the patrolling police officers’ main task is to engage in different challenging social environments during their whole working day, while also being in daily communication with both the public living in the community they protect, colleagues, as well as different institutions.

Occupational environment

Our findings show some environmental qualities facilitating the police officers in their occupational environment. For example, time elements and the importance of cultural aspects. However, the hindering qualities seemed to overtake the facilitating qualities.

Time elements, flexibility and structure are closely linked in the review because they all relate to time in different ways. For example, the qualities include hours spent both at work and outside work, as well as aspects of time regarding the opportunities for patrolling officers to do what they want and when they want to do it. They also include scheduling, leisure time and the sense of not having enough time. These findings are supported by other police research, in which time, in different ways, relates to police officers’ health. For example, long working hours and shift work have been linked to poor health outcomes [Citation2,Citation98,Citation112–114]. Also, when examining leisure time activities such as sport and recreational activities, both have been shown to improve police officers’ health in different ways [Citation115,Citation116]. Work-life conflicts and the family life of patrolling police officers have been previously studied [Citation2,Citation15,Citation16,Citation39,Citation117]. However, such studies have not been conducted within the EU, as far as we know, and time elements need further research, particularly on time spent outside work.

The quality of participation is an interesting quality in which opportunities for decision-making within the police force and advancing professionally in different ways is regarded as being important. Previous research supports the finding of disparities between the job and the job description [Citation40], which has been found to negatively affect police officers’ health. Also, in previous research, organizational and environmental factors such as opportunities to innovate and job challenges have been shown to affect the job satisfaction of police officers [Citation118], as well as their ability to make their own choices that promote personal accomplishment and acknowledge a job well done [Citation119]. Also, according to Fisher, Parkinson and Haglund [Citation36], understanding how different environments influence human occupation is achieved by understanding the concept of enabling. Since different environments can enable or discourage a patrolling officer’s participation, it is an important quality to study when considering police officers’ health and well-being.

Likewise, funding and policies touch upon the quality of participation, since the uniform and equipment used, as well as the educational possibilities provided at work, are decisions that are made above the police officers’ heads. Professional education for police officers has been discussed as essential to organizational and personal performance to provide better service to the community safely and efficiently [Citation120].

Occupational and activity choices are important qualities for all human beings. For police officers, they relate to the connection between challenges and demands. This is particularly important since, according to Fisher, Parkinson and Haglund [Citation36], environmental impact refers to the opportunity, support, demand and constraints of the different environments on particular individuals, in this case, police officers. This varies since it depends on the values, interests, personal causation, roles, habits and performance capacity of the specific officer [Citation36].

The quality of appeal of occupations and activities is also important and this review is adjacent to the quality of cultural aspects because it comprises aspects of the concept of police culture, which includes status or image of the job, as well as enjoyment of the job itself. Thus, cultural aspects and the appeal of occupations and activities include police culture, in which the organizational culture and cultural preferences of different workplaces, and the group climate are also included.

Organizational culture and police culture have been connected in previous research [Citation40] although, according to Bowling, Reiner, and Sheptycki [Citation121], police culture as a concept is defined in the following four dimensions: action orientation, the presence of a certain set of values, a particular kind of identity, and the distinctive meaning attached to police work [Citation121]. However, police culture has recently become more nuanced, focussing on individual aspects and implying that there has been a change in culture, including between different environments [Citation122]. This is also supported by our findings where not only does the typical concept of police culture exist but also other aspects of work culture. Thus, the meaning of these four key dimensions has been previously challenged and now potentially includes additional aspects [Citation123]. Consequently, it would be beneficial to further study the police culture in Europe.

Physical environment

Qualities regarding the physical environments were scarce, also which qualities would facilitate the health and life of police officers. However, the adequacy of objects and adequacy of space were identified as two qualities in the physical environment. These are important issues regarding police officers’ health and previous studies have shown, for example, that body armour has an impact on biomedical aspects and physical performance and that these should be optimised for the individual user [Citation124]. Previous research has also highlighted sedentary behaviour in, for example, police vehicles, which may impact police officers’ health together with other work-related factors [Citation1,Citation14,Citation125].

One key finding in this review is the need for further study of the physical environment for patrolling officers within the EU. For example, only one study was found touching upon the quality accessibility and safety of spaces. The study presents findings related to the direct result of hazardous situations and being affected physically by different education provided to the officers. It is important to comprehend occupational hazards and exposure to threats in physical environments as they have also been found to affect both the physical and mental health of police officers [Citation1,Citation11,Citation108], sometimes resulting in death [Citation126].

Strengths and limitations

A key strength of this review was the rigorous, systematic and standardised methodological approach to addressing significant gaps in the literature.

A few limitations should be discussed, for example, the exclusion of the sixth additional stage of Arksey and O’Malley’s methodology, for practical reasons. This would have provided an opportunity for knowledge transfer and exchange between police officers. Such a knowledge transfer and exchange could not be applied and thereby enhance the results.

Another limitation is that the scope of the review may have been too narrow since none of the grey literature that had been identified remained after the exclusion criteria had been applied. As an example, we excluded specialised units within patrolling services, such as traffic officers and dog handlers. Also, we only included studies written in English and the Scandinavian languages and had English words in the search string. Hence, reliable and relevant studies from countries not included in the study might have been missed, particularly within the grey literature. Although grey literature could have provided greater strength in terms of representing the field, we now had more control over the population we included in the study, which is a strength of the study.

Another limitation was the search algorithm, which excluded the frequently used keyword ‘policing’ to identify articles that only focussed on patrol duty. By excluding the word, we might have missed articles, but we also excluded an abundance of irrelevant articles not related to our study’s aim. Also, the articles’ reference lists were not checked due to resource limitations, meaning additional articles could have been missed. To compensate for this, we however added articles we were aware of that did not show up in the search.

Nevertheless, the scoping review was conducted using systematic review software to minimise the number of mistakes made by sorting articles, while aiding in the blinding process. We searched eight different databases and conducted a second search at the end of the analysis to enhance the correctness of the study. To ensure the quality of the study, several steps in the review were undertaken by two different reviewers and the data extraction form was piloted and revised. Hence, the study aimed to achieve procedural and methodological rigour and still has the potential to contribute to future developments, within theory, practice, education and research regarding patrolling police officers’ life contexts.

Conclusion and implications for future research

The present review has identified and summarised life contexts of patrolling police officers in the EU from the perspective of the environmental model in MOHO. It has also highlighted 20 years of peer-reviewed literature on the different environmental qualities that affect patrolling police officers’ life and health, mainly from their working life. Thus, due to the gaps in the identified knowledge, our results suggest there is a need for more research into police officers’ all life contexts and how their health is affected by the different environments they reside in. Hence, to complement this review, further research is needed also within their private life contexts and environments.

The global context also needs further study since police officers are frequently affected at work by new laws, regulations, and policy changes, and we do not know enough how this affects their health. These contexts and environments most likely make an impact and should be considered to be crucial factors when researching their health (see examples that describe the current working life of police officers [Citation127,Citation128]). Thus, new policy changes, new methods, and evidence-based police work within patrol duty should always include the outcomes of changes in police officers’ health, not least because, according to Taylor [Citation30], the demands and constraints of an environment can negatively affect the motives and actions of a person.

Since there was a gap in the geographical area of the research that was identified, we would also emphasise the need for research into patrolling officers’ life contexts in more European countries. Our results also indicate the need to use additional research methods, since most studies in the review comprised cross-sectional studies. For example, environmental components and qualities, and how these empower police officers, could be identified if more qualitative studies were to be conducted. Moreover, longitudinal studies are required to study police officers’ health over time in relation to ever-changing contexts.

Our findings show that working as a patrolling police officer means engaging in various life contexts in which several environments co-exist. While some environmental qualities support the officers, others do not. Patrolling police officers have a unique task in constantly upholding the law and protecting the public citizens while also dealing with public emergencies and legal issues. Hence, it should be of particular concern to focus on patrolling police officers’ health to enhance their occupational performance capacities. As well as their opportunities to engage in a sustainable lifestyle.

According to Rowles [Citation129], empirical and clinical research must develop environment-focussed practice strategies that support and encourage the continuing search for meaning that remains the core motivation of each person regardless of their life contexts [Citation129]. However, within occupational therapy practice and research, developing environment-focussed practice strategies for patrolling police officers has so far been excluded. Thus, our review will be used as a base for developing an instrument measuring police officers’ life and health grounded in their contexts and environments. The instrument could in the future be used by occupational therapists to measure health promotion programmes that contribute to the health and well-being of police officers.

This review has also paved the way for studying police officers’ health from the perspective of occupational science. As of today, the health of police officers has mainly been a research field within psychology and the social sciences. Thus, our intention is for the results to make an impact on future research to include the conceptual frameworks of occupational therapists when exploring police officers’ health, and the environments they exist in.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Mona GG, Chimbari MJ, Hongoro C. A systematic review on occupational hazards, injuries and diseases among police officers worldwide: policy implications for the South African Police Service. J Occup Med Toxicol. 2019;14:2–15.

- Violanti JM, Charles LE, McCanlies E, et al. Police stressors and health: a state-of-the-art review. Policing. 2017;40:642–656.

- Han M, Park S, Park JH, et al. Do police officers and firefighters have a higher risk of disease than other public officers? A 13-year nationwide cohort study in South Korea. BMJ Open. 2018;8:1–7.

- Larsson G, Berglund AK, Ohlsson A. Daily hassles, their antecedents and outcomes among professional first responders: a systematic literature review. Scand J Psychol. 2016;57:359–367.

- Nixon AE, Mazzola JJ, Bauer J, et al. Can work make you sick? A meta-analysis of the relationships between job stressors and physical symptoms. Work Stress. 2011;25:1–22.

- Woods J. Policing, danger narratives, and routine traffic stops. Mich Law Rev. 2019;117:635-712.

- Leino TM, Selin R, Summala H, et al. Violence and psychological distress among police officers and security guards. Occup Med (Lond). 2011;61:400–406.

- Schouten R, Brennan DV. Targeted violence against law enforcement officers. Behav Sci Law. 2016;34:608–621.

- Krope SF, Lobnikar B. Assaults on police officers in Slovenia - the profile of perpetrators and assaulted police officers. Rev Za Krim Kriminol. 2015;66:300–306.

- AFA försäkring. Hot och våld på den svenska arbetsmarknaden. Stockholm: AFA försäkring; 2018. [Internet]; [cited 2021 Oct 20]. Available from: https://www.afaforsakring.se/globalassets/nyhetsrum/seminarier/hot-och-vald-pa-den-svenska-arbetsmarknaden/f6345-delrapport-4---hotovald.pdf.

- Andersson EE, Larsen LB, Ramstrand N. A modified job demand, control, support model for active duty police. Work J Prev Assess Rehabil. 2017;58:361–370.

- West C, Fekedulegn D, Andrew M, et al. On-duty nonfatal injury that lead to work absences among police officers and level of perceived stress. J Occup Environ Med. 2017;59:1084–1088.

- Ramstrand N, Zügner R, Larsen LB, et al. Evaluation of load carriage systems used by active duty police officers: relative effects on walking patterns and perceived comfort. Appl Ergon. 2016;53:36–43.

- Benyamina Douma N, Côté C, Lacasse A. Occupational and ergonomic factors associated with low back pain among car-patrol police officers: findings from the Quebec Serve and Protect Low Back Pain Study. Clin J Pain. 2018;34:960–966.

- Duxbury L, Bardoel A, Halinski M. 'Bringing the Badge home’: exploring the relationship between role overload, work-family conflict, and stress in police officers. Polic Soc. 2021;31:997–1016.

- Tuttle BM, Giano Z, Merten MJ. Stress spillover in policing and negative relationship functioning for law enforcement marriages. Fam J. 2018;26:246–252.

- Lambert EG, Qureshi H, Frank J, et al. The relationship of work-family conflict with job stress among Indian police officers: a research note. Police Pract Res. 2017;18:37–48.

- Duxbury LE, Halinski M. It’s not all about guns and gangs: role overload as a source of stress for male and female police officers. Polic Soc. 2018;28:930–946.

- Svedberg P, Alexanderson K. Associations between sickness absence and harassment, threats, violence, or discrimination: a cross-sectional study of the Swedish police. Work Read Mass. 2012;42:83–92.

- Violanti JM, Hartley TA, Andrew ME, et al. Police work absence: an analysis of stress and resiliency. J Law Enforc Leadersh Ethics. 2014;1:49–67.

- PATROL OFFICER | definition in the Cambridge English Dictionary [Internet]. [cited 2020 Oct 13]. Available from: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/us/dictionary/english/patrol-officer.

- Polislag ( 1984:387) Svensk författningssamling 1984:1984:387 t.o.m. SFS 2019:37 - Riksdagen [Internet]. [cited 2020 Oct 13]. Available from: https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-lagar/dokument/svensk-forfattningssamling/polislag-1984387_sfs-1984-387.

- Wilcock AA, Hocking C. An occupational perspective of health. 3rd ed. Hocking C, editor. Thorofare (NJ): SLACK Incorporated; 2015.

- Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists. Enabling occupation: an occupational therapy perspective. Ontario, Canada: Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists; 1997.

- Christiansen CH, Baum CM. Occupational therapy: enabling function and well-being. 2nd ed. Thorofare (NJ): SLACK Incorporated; 1997.

- Dunn W, Brown C, McGuigan A. The ecology of human performance: a framework for considering the effect of context. Am J Occup Ther Off Publ Am Occup Ther Assoc. 1994;48:595–607.

- Hocking C. Occupation in context: a reflection on environmental influences on human doing. J Occup Sci. 2021;28:221–234.

- Townsend EA, Polatajko HJ. Enabling occupation II advancing an occupational therapy vision for health, well-being & justice through occupation. Ottawa, Ontario: Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists; 2013.

- Baum CM, Christiansen CH, Bass JD. The Person-Environment-Occupation- Performance (PEOP) model. In: Occup Ther Perform Particip Well-Being. 4th ed. Thorofare (NJ): SLACK Incorporated; 2015. p. 49–56.

- Taylor R. Kielhofner’s model of human occupation theory and application. Philadelphia: Wolvers Kluver; 2017.

- Law M, Cooper B, Strong S, et al. The Person-Environment-Occupation model: a transactive approach to occupational performance. Can J Occup Ther. 1996;63:9–23.

- Bronfenbrenner U. Toward an experimental ecology of human development. Am Psychol. 1977;32:513–531.

- Wicker A. An introduction to ecological psychology. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1984.

- Kielhofner G. Model of human occupation: theory and application. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008.

- Iwama M. The Kawa model: culturally relevant occupational therapy. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 2006.

- Fisher G, Parkinson S, Haglund L. The environment and human occupation. In: Taylo R, editor. Kielhofners model of human occupation. 5th ed. Philadephia: Wolters Kluwer; 2017. p. 91–106.

- Bronfenbrenner U. Making human beings human: bioecological perspectives on human development. London: Sage Publications; 2005.

- Brown JM, Campbell EA. Sources of occupational stress in the police. Work Stress. 1990;4:305–318.

- Karaffa K, Openshaw L, Koch J, et al. Perceived impact of police work on marital relationships. Fam J. 2015;23:120–131.

- Deschênes A-A, Desjardins C, Dussault M. Psychosocial factors linked to the occupational psychological health of police officers: preliminary study. Walla P, editor. Cogent Psychol. 2018;5:1–10.

- Hansson J, Hurtig A-K, Lauritz L-E, et al. Swedish police officers job strain, Work-related social support and general mental health. J Police Crim Psych. 2017;32:128–137.

- Price M. Psychiatric disability in law enforcement officers. Behav Sci Law. 2017;35:113–123.

- Zimmerman FH. Cardiovascular disease and risk factors in law enforcement personnel: a comprehensive review. Cardiol Rev. 2012;20:159–166.

- Magnavita N, Capitanelli I, Garbarino S, et al. Work-related stress as a cardiovascular risk factor in police officers: a systematic review of evidence. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2018;91:377–389.

- Franke WD, Ramey SL, Shelley MC. Relationship between cardiovascular disease morbidity, risk factors, and stress in a law enforcement cohort. J Occup Environ Med. 2002;44:1182–1189.

- Gershon RRM, Barocas B, Canton AN, et al. Mental, physical, and behavioral outcomes associated with perceived work stress in police officers. Crim Justice Behav. 2009;36:275–289.

- Davey JD, Obst PL, Sheehan MC. It goes with the job: officers’ insights into the impact of stress and culture on alcohol consumption within the policing occupation. Drugs Educ Prev Policy. 2001;8:140–149.

- Ballenger JF, Best SR, Metzler TJ, et al. Patterns and predictors of alcohol use in male and female urban police officers. Am J Addict. 2011;20:21–29.

- Argustaitė-Zailskienė G, Šmigelskas K, Žemaitienė N. Traumatic experiences, mental health, social support and demographics as correlates of alcohol dependence in a sample of Lithuanian police officers. Psychol Health Med. 2020;25:396–401.

- Beehr TA, Johnson LB, Nieva R. Occupational stress: coping of police and their spouses. J Organiz Behav. 1995;16:3–25.

- Abdollahi MK. Understanding police stress research. J Forensic Psychol Pract. 2002;2:1–24.

- Kamioka H. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Yakuri Chiryo Basic Pharmacol Ther. 2019;47:1177–1186.

- Valmari EG. Life contexts among patrolling police officers in the European Union, investigating environmental characteristics and health – A protocol for a scoping review and systematic review. 2021. [cited 2021 Aug 30]; Available from: https://osf.io/tzad8/

- Granholm Valmari E, Ghazinour M, Nygren U, et al. Life contexts among patrolling police officers in the European Union, investigating environmental characteristics and health – a protocol for a scoping review and a systematic review. Scand J Occup Ther. 2021;0:1–8.

- Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol Theory Pract. 2005;8:19–32.

- Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5:1–9.

- Daudt HML, Van Mossel C, Scott SJ. Enhancing the scoping study methodology: a large, inter-professional team’s experience with Arksey and O’Malley’s framework. BMC Med Res Methodol BioMed Central. 2013;13:1–9.

- Peters MDJ, Godfrey C, McInerney P, et al. Chapter 11: Scoping reviews (2020 version). In: Aromataris E, Munn Z, editors. JBI manual for evidence synthesis, JBI; 2020. [Internet]; [cited 2021 Nov 12]. Available from: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, PRISMA Group, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int J Surg. 2010;8:336–341.

- Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:467–473.

- Aromataris E, Munn Z. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis [Internet]. 2020. [cited 2021 Nov 16]. Available from: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global.

- Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, et al. Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016;5:1–10.

- Paez A. Gray literature: an important resource in systematic reviews. J Evid Based Med. 2017;10:233–240.

- Hong QN, Fàbregues S, Bartlett G, et al. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. EFI. 2018;34:285–291.

- Souto RQ, Khanassov V, Hong QN, et al. Systematic mixed studies reviews: updating results on the reliability and efficiency of the mixed methods appraisal tool. Int J Nurs Stud Elsevier Ltd. 2015;52:500–501.

- Hong QN, Pluye P, Fàbregues S, et al. Improving the content validity of the mixed methods appraisal tool: a modified e-Delphi study. J Clin Epidemiol. 2019;111:49–59.

- Microsoft Excel. Microsoft corporation; 2018. Available from: https://office.microsoft.com/excel

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77–101.

- VERBI Software. MAXQDA 2020 [computer software]. Berlin, Germany: VERBI Software; 2019.

- Microsoft Corporation. Microsoft word. 2018. Available from: https://office.microsoft.com/excel

- Ramstrand N, Larsen LB. Musculoskeletal injuries in the workplace: perceptions of swedish police. Int J Police Sci Manag. 2012;14:334–342.

- Takken T, Ribbink A, Heneweer H, et al. Workload demand in police officers during Mountain bike patrols. Ergonomics. 2009;52:245–250.

- Terpstra J, Schaap D. Police culture, stress conditions and working styles. Eur J Criminol. 2013;10:59–73.

- Backteman-Erlanson S, Padyab M, Brulin C. Prevalence of burnout and associations with psychosocial work environment, physical strain, and stress of conscience among Swedish female and male police personnel. Police Pract Res. 2013;14:491–505.

- Larsen LB, Tranberg R, Ramstrand N. Effects of thigh holster use on kinematics and kinetics of active duty police officers. Clin Biomech. 2016;37:77–82.

- Padyab M, Backteman-Erlanson S, Brulin C. Burnout, coping, stress of conscience and psychosocial work environment among patrolling police officers. J Police Crim Psych. 2016;31:229–237.

- Ellrich K. Burnout and violent victimization in police officers: a dual process model. PIJPSM. 2016;39:652–666.

- Ellrich K. The influence of violent victimisation on police officers’ organisational commitment. J Police Crim Psych. 2016;31:96–107.

- Ellrich K, Baier D. The influence of personality on violent victimization – A study on police officers. Psychol Crime Law. 2016;22:538–560.

- Wain N, Ariel B, Tankebe J. The collateral consequences of GPS-LED supervision in hot spots policing. Police Pract Res. 2017;18:376–390.

- Bürger B, Nachreiner F. Individual and organizational consequences of employee-determined flexibility in shift schedules of police patrols. Police Pract Res. 2018;19:284–303.

- Larsen LB, Andersson EE, Tranberg R, et al. Multi-site musculoskeletal pain in swedish police: associations with discomfort from wearing mandatory equipment and prolonged sitting. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2018;91:425–433.

- Engel S, Wörfel F, Maria AS, et al. Leadership climate prevents emotional exhaustion in german police officers. Int J Police Sci Manag. 2018;20:217–224.

- Vera Jimenez JC, Fernandez F, Ayuso J, et al. Evaluation of the police operational tactical procedures for reducing officer injuries resulting from physical interventions in problematic arrests. The case of the municipal police of cadiz (Spain). Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2020;33:35–43.

- Kop N, Euwema MC. Occupational stress and the use of force by Dutch police officers. Crim Justice Behav. 2001;28:631–652.

- Maran DA, Varetto A, Zedda M, et al. Stress among italian male and female patrol police officers: a quali-quantitative survey. Policing. 2014;37:875–890.

- Gallagher M, Muldoon OT, Pettigrew J. An integrative review of social and occupational factors influencing health and wellbeing. Front Psychol. 2015;6:1-11.

- James Brennan G, Gallagher M. Expectations of choice: an exploration of how social context informs gendered occupation. IJOT. 2017;45:15–27.

- Santa Maria A, Wolter C, Gusy B, et al. The impact of health-oriented leadership on police officers’ physical health, burnout, depression and well-being. Polic J Policy Pract. 2019;13:186–200.

- Cheema R. Black and blue bloods: protecting police officer families from domestic violence. Fam Court Rev. 2016;54:487–500.

- Hall GB, Dollard MF, Tuckey MR, et al. Job demands, work-family conflict, and emotional exhaustion in police officers: a longitudinal test of competing theories. J Occup Organ Psychol. 2010;83:237–250.

- Santa Maria A, Wörfel F, Wolter C, et al. The role of job demands and job resources in the development of emotional exhaustion, depression, and anxiety among police officers. Police Q. 2018;21:109–134.

- McCanlies EC, Gu JK, Andrew ME, et al. The effect of social support, gratitude, resilience and satisfaction with life on depressive symptoms among police officers following hurricane katrina. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2018;64:63–72.

- Sundqvist J, Padyab M, Hurtig AK, et al. The association between social support and the mental health of social workers and police officers who work with unaccompanied asylum-seeking refugee children’s forced repatriation: a Swedish experience. Int J Ment Health. 2018;47:3–25.

- Simons Y, Barone DF. The relationship of work stressors and emotional support to strain in police officers. Int J Stress Manage. 1994;1:223–234.

- Horan SM, Bochantin J, Booth-Butterfield M. Humor in high-stress relationships: understanding communication in police officers’ romantic relationships. Commun Stud. 2012;63:554–573.

- Sherwood L, Hegarty S, Vallières F, et al. Identifying the key risk factors for adverse psychological outcomes among police officers: a systematic literature review. J Trauma Stress. 2019;32:688–700.

- Purba A, Demou E. The relationship between organisational stressors and mental wellbeing within police officers: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:1286.

- Viljoen E, Bornman J, Wiles L, et al. Police officer disability sensitivity training: a systematic review. Police J. 2017;90:143–159.

- Johnson RR. Perceptions of interpersonal social cues predictive of violence among police officers who have been assaulted. J Police Crim Psych. 2015;30:87–93.

- Brandl SG, Stroshine MS, Frank J. Who are the complaint-prone officers? An examination of the relationship between police officers’ attributes, arrest activity, assignment, and citizens’ complaints about excessive force. J Crim Justice. 2001;29:521–529.

- Ashlock JM. Gender attitudes of police officers: selection and socialization mechanisms in the life course. Soc Sci Res. 2019;79:71–84.

- van Reemst L, Fischer TF, Zwirs BW. Response decision, emotions, and victimization of police officers. Eur J Criminol. 2015;12:635–657.

- Simmler M, Stempkowski M, Markwalder N. Punitive attitudes and victimization among police officers in Switzerland: an empirical exploration. Police Pract Res. 2021;22:1191–1208.

- Qureshi H, Lambert EG, Frank J. The relationship between stressors and police job involvement. Int J Police Sci Manag. 2019;21:48–61.

- Cheong J, Yun I. Victimization, stress and use of force among South Korean police officers. Policing. 2011;34:606–624.

- Manzoni P, Eisner M. Violence between the police and the public. Crim Justice Behav. 2006;33:613–645.

- Lyons K, Radburn C, Orr R, et al. A profile of injuries sustained by law enforcement officers: a critical review. IJERPH. 2017;14:142.

- Verhage A, Noppe J, Feys Y, et al. Force, stress, and decision-making within the Belgian police: the impact of stressful situations on police decision-making. J Police Crim Psych. 2018;33:345–357.

- Nalla MK, Meško G, Modic M. Assessing police–community relationships: is there a gap in perceptions between police officers and residents? Polic Soc. 2018;28:271–290.

- Gong Z, Zhang J, Zhao Y, et al. The relationship between feedback environment, feedback orientation, psychological empowerment and burnout among police in China. PIJPSM. 2017;40:336–350.

- Fekedulegn D, Burchfiel CM, Hartley TA, et al. Shiftwork and sickness absence among police officers: the BCOPS study. Chronobiol Int. 2013;30:930–941.

- James L, James S, Vila B. The impact of work shift and fatigue on police officer response in simulated interactions with citizens. J Exp Criminol. 2018;14:111–120.

- Violanti JM. Shifts, extended work hours, and fatigue: an assessment of health and personal risks for police officers. Amherst (NY): Natl Inst Just (US); 2012 Mar. Report No.: 2005-FS-BX-0004.

- García-Rivera BR, Olguín-Tiznado JE, Aranibar MF, et al. Burnout syndrome in police officers and its relationship with physical and leisure activities. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:1–17.

- Fekedulegn D, Innes K, Andrew ME, et al. Sleep quality and the cortisol awakening response (CAR) among law enforcement officers: the moderating role of leisure time physical activity. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2018;95:158–169.

- Bazana S, Dodd N. Conscientiousness, work family conflict and stress amongst police officers in Alice, South Africa. J Psychol. 2013;4:1–8.

- Nalla MK, Rydberg J, Meško G. Organizational factors, environmental climate, and job satisfaction among police in Slovenia. Eur J Criminol. 2011;8:144–156.

- Johnson RR, Lafrance C. The influence of career stage on police officer work behavior. Crim Justice Behav. 2016;43:1580–1599.

- Haberfeld MR. Clarke CA, Sheehan DL. Police organization and training: innovations in research and practice. New York (NY): Springer New York; 2011.

- Bowling B, Reiner R, Sheptycki J. The politics of the police. 5th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2019.

- Reiner R. Opinion: is police culture cultural? Policing. 2016;11:236–241.

- Caveney N, Scott P, Williams S, et al. Police reform, austerity and ‘cop culture’: time to change the record? Polic Soc. 2020;30:1210–1225.

- Tomes C, Orr RM, Pope R. The impact of body armor on physical performance of law enforcement personnel: a systematic review. Ann Occup Environ Med. 2017;29:14.

- Douma NB, Côté C, Lacasse A. Quebec serve and protect low back pain study: a web-based cross-sectional investigation of prevalence and functional impact among police officers. Spine. 2017;42:1485–1493.

- Tiesman HM, Hendricks SA, Bell JL, et al. Eleven years of occupational mortality in law enforcement: the census of fatal occupational injuries, 1992–2002. Am J Ind Med. 2010;53:940–949.

- Felab Brown V. How COVID-19 is changing law enforcement practices by police and by criminal groups [Internet]. Brookings. 2020. [cited 2020 Nov 26]. Available from: https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2020/04/07/how-covid-19-is-changing-law-enforcement-practices-by-police-and-by-criminal-groups/.

- Stogner J, Miller BL, McLean K. Police stress, mental health, and resiliency during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Crim Just. 2020;45:718–730.

- Rowles GD. Place in occupational science: a life course perspective on the role of environmental context in the quest for meaning. J Occup Sci. 2008;15:127–135.