Abstract

Background

Weighted blankets (WBs) have been suggested as a treatment option for insomnia and are commonly prescribed despite lack of evidence of efficacy.

Aim

To investigate prescription pattern, return rate and cost of WBs.

Material and methods

This observational cohort register-based study in western Sweden included every individual who, in a 2.5-year period, was prescribed and received at least one WB (n = 4092). A cost evaluation was made by mapping prescription processes for WBs and sleep medication.

Results

Individuals diagnosed with dementia, anxiety, autism or intellectual disability (ID) retained the WB longer than others. Individuals younger than six and older than 65 years had shorter use time. The cost evaluation showed that the prescription process for WBs was longer and resulted in a higher cost than for sleep medication.

Conclusions

Some individuals had longer use time, indicating a possible benefit from using a WB. Due to low risk of harm but high economic cost, a revision of the WBs prescription process could be recommended to identify those who might benefit from WB.

Significance

Our result points towards a need for revision of the prescription process, to implement standardized sleep assessments, and create a more efficient prescription process to lower the cost.

Introduction

Difficulties with sleep have been regarded as common and been found to be associated with adverse health outcomes [Citation1,Citation2]. In developed countries, the annual rate of people in the general population experiencing sleep difficulties have been estimated to be from 6 up to 30% [Citation3,Citation4]. The causes of sleep difficulties are varied and can be temporary in relation to stressful life situations or may be due to medical conditions, both somatic and psychiatric [Citation1,Citation2,Citation5]. Difficulties with sleep have been found to be associated with increased risk of depression, psychosomatic disorders, substance use disorder as well as cardiovascular and metabolic health problems [Citation1,Citation6]. Long-term difficulties with sleep, that also have a negative impact on social and family life and can affect working ability, leading to a fall in productivity, poor judgement and inappropriate emotional reactions is often referred to as insomnia [Citation1–3,Citation6,Citation7]. Insomnia both refers to a diagnosis but is also used to describe both recurrent and transient type of sleep difficulties [Citation8].

In addition, sleep difficulties were found to be associated with a large economic cost at both the societal and the individual level [Citation9,Citation10]. The societal costs of sleep-related difficulties, both direct and indirect, have been estimated to approach 1.55% of gross domestic product in some countries [Citation11].

Swedish disability policy focuses on providing solutions for the individual, to enhance the person’s ability to live and participate in society on equal terms with the non-disabled [Citation12]. The health care system provides a variety of interventions for insomnia, for example, pharmacologic treatment, cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and sleep education courses. Pharmaceuticals for sleep are frequently prescribed and are often perceived as a quick solution for insomnia, but there is a lack of longitudinal studies concerning side effects. Therefore, in Sweden the general recommendation is to keep sleep medication as a short-term intervention [Citation13,Citation14]. CBT is one common approach for sleep difficulties in the adult population. CBT is described as an evidence-based therapy, and a structured way of collaborating with a therapist. The therapist will map the difficulties, and work towards changing unwanted cognitive and behavioural patterns. CBT requires multiple treatment sessions [Citation13–15]. Sleep education is a collective name for several different psychoeducation programmes. The programmes usually involve lectures about different types of sleep issues and general information about sleep hygiene, such as optimal bed routines, creating an environment for sleep, while providing information about activities that may create a good foundation for sleep. It has been suggested that sleep education be used as a complement to larger programmes, and not as a replacement for other types of treatment [Citation16].

Weighted blankets (WBs) have been suggested as an alternative method for modulation of well-being through deep touch pressure (DTP) [Citation17]. The effect of the WB is based on the theory that DTP contribute to a feeling of well-being and comfort, through increased levels of oxytocin, which in turn results in relaxation and promotes sleep [Citation17–19]. A WB is a non-invasive intervention in the form of an assistive device [Citation17]. In Sweden they are usually prescribed by an occupational therapist as part of their focus on creating a sound relationship between sleep and daytime activity for the patient. At a national level in Sweden there are general guidelines regarding assistive and compensatory technical aids, but the process of prescription, assessment and evaluation of the use of the aids, has been delegated to the regional health authorities and can differ [Citation20].

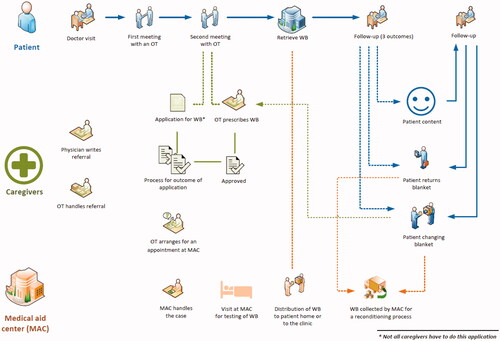

In Region Västra Götaland (VGR) the prescription process for WBs involves mapping the sleep difficulty through a structured interview, a 14-d sleep diary that the patient is required to write and discussions about sleep hygiene with a therapist, all before a decision is made concerning whether a WB could be suitable or not. The occupational therapist (OT) then applies for a WB if he/she considers that the documentation meets the criteria. There are different WBs available, containing a variety of materials such as balls, chains or fibres and the weight ranges from 3 to 14 kg. The type of blanket prescribed is decided in collaboration between the therapist and the patient. The patient is often given the possibility of trying out the different WBs at the clinic or at the Medical aid centre (MAC).

The use of WBs is believed to be safe, with no known side effects in the adult population [Citation21–23]. However, the scientific evidence of the effect of WBs on the treatment of sleep difficulties is debateable [Citation21]. The clinical experience from prescribing a WB has been a positive effect on patient well-being [Citation24,Citation25]. Double-blind randomized controlled studies (RCTs) have been difficult to execute since most individuals would know if they have used a weighted blanket or not. Nevertheless, the high interest in a non-invasive aid for sleep has resulted in several recent studies [Citation23,Citation25–29]. One study examined the effect on 16 new-born babies with neonatal abstinence syndrome and found a significant decrease in heart rate when the WB was applied, which was believed to represent the calming effect of the WB [Citation26]. Ekholm et al. [Citation27] studied 120 psychiatric patients who were randomized to either use a WB with heavy chains, or a lighter blanket with plastic chains. The patients with heavier blankets generally reported greater improvements in sleep, as well as possible better daytime functioning. Furthermore, there were no indications of adverse events [Citation21]. Baric et al. [Citation28] found positive effects on both sleep quality and daily routines for a group of people with psychiatric diagnoses using the WB every night [Citation28]. There has been a belief that WBs lessen the use of pharmaceuticals; Steingrímsson et al. found that in the adult population there is a weak, although significant association between reduced medications and use of WBs [Citation29].

To date, there has been no large-scale epidemiological study evaluating the usage and costs of WBs in clinical practice. In VGR the cost of prescribing a WB has been estimated at 7 million SEK/year, though free of charge for the patients [Citation30]. A general need has been identified for health economic evaluations of occupational therapy interventions [Citation31]. With a further need to study inter-regional and inter-national differences in the prescription processes that most likely exist despite national processes [Citation20] and how these affect both cost-effectiveness and use of resources for rehabilitation and prevention of further illness.

The aim of this study was to investigate the pattern of prescriptions, the return rate and the cost of WBs in VGR, Sweden.

Material and methods

Design

This study consisted of two parts: (1) a registry study to investigate the patterns of prescription and return rate of WBs and (2) an activity-based cost analysis comparing the prescribing process of WBs with that of sleep medications.

Participants

The cohort study included all individuals in VGR who in the period from 01-05-2015 to 31-12-2017 were prescribed and received at least one WB. VGR is Sweden’s second-largest region with a total population of over 1,725,000 people [Citation30]. The region consists of both rural and urban areas, with four major areas of care provision situated around four major hospitals. VGR guidelines for the process of prescribing a WB include criteria to establish that sleeping problems have been present for a long time, that the individual has been diagnosed with a chronic psychiatric disease and that the patient should fill in a sleeping diary for 2 weeks. If the individual requires an extended time to fall asleep (more than 1.5 h) and/or wakes up several times during the night (more than 3), he or she is eligible for prescription of a WB.

Data sources

Three major care data registries in VGR were used to collect data for statistical analyses. The variables extracted were: type and weight of the WB, date of delivery, exchange and return of the WB, sex, age, and diagnosis/-es prior to receiving the first WB.

Cost analysis

The prescribing processes for both WB and sleep medications were mapped, and an activity-based process cost analysis, inspired by time-driven activity-based process cost analysis [Citation32], was performed to assess differences in costs between the prescribing processes. The mapping of each process was done by means of interviews with prescribers and other involved professionals. The processes were monetized in Euros (€) by using the Human Capital Method, which includes quantifying total time use by each prescriber, or other personnel, at each step in the process, valued at the cost of the salary for each personnel category, including social-security contributions at a rate of 46% of the salary amount [Citation33]. Costs such as the monthly subscription cost for each WB in the region, and the costs for pharmaceuticals were also included in the analysis. The time horizon was based on the median use of a WB rather than a life-cycle perspective. The time and other costs invested by the patient were not included in the cost analysis. The currency exchange rate from 7 February 2017, which is representative of the period studied, when SEK 10 = Euro (€)1, was used in the analysis.

In total, 16 different scenarios were constructed to describe how the prescribing process of WBs varied depending on, for instance, where the patients lived or where they were in the health care chain. Depending on what type of care provider the patient was treated by different requirements and activities were needed before the patient could be prescribed a WB. The proportion of patients treated by different types of providers was known from the register data, and as such the total number of prescribed WBs and sleep medications was distributed across the scenarios in accordance with these proportions. The scenarios ranged from only including parts of the steps described to including all of them. For WB, the scenario with the fewest number of steps included the OT visits and follow-up, the actual prescribing by the OT, the distribution of the WB to the clinic by the MAC, and then the collection of the WB which then are kept by the patient at follow-up. One scenario included all possible steps, i.e. all the visits, the prescriber having to write an application for WB that would have to be approved before the actual prescribing, the patient having to visit the MAC, and all associated steps and visits, as well as the patient returning and changing WB twice once collected, which then includes the MAC having to recondition the WB. Most patients belonged to scenarios where the OT had to write an application that had to be approved before writing the prescription of the WB, but without having to visit the MAC for testing of WB (). For the prescription of sleep medication, 4 scenarios were constructed. Given the proportion of patients in each scenario, this was used to calculate a weighted average cost for each prescribing process.

Statistics

This was a descriptive study and statistical analysis was primarily based on descriptive statistics such as mean and standard deviation for continuous variables such as age and absolute and relative frequencies for categorical variables. The relation between the time since the start of the study and the proportion of WB returned was summarized using 1 minus the estimated survival function, calculated using a Kaplan-Meier estimator. The association between time to return and sex, age, type of WB, the weight of the WB and pre-index diagnoses was evaluated using Cox proportional hazards regression which models the associated hazard function and its dependence on the covariates included in the model. People who died or moved out of the region without returning the WB were considered censored. The statistical analyses done in SAS version 9.4 (SAS Inc., Cary, NC) and "R Core Team" (2020) version 4.0.2 and were based on patients with complete data, as missing data were very rare.

Ethical approval and considerations

The data were protected through a code key that was destroyed before data was received by the individual researcher. This study was approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (registration number 1122-18/2019-00620).

Results

Prescription pattern

A total of 4092 individuals were included in the study. The mean age was 31.5 (SD 24.9) years, and the median age was 23 years (range 1–103). The distribution between men and women was relatively equal with a slight majority of women (55.9%) (). The chain blanket was the most common WB (64%), followed by the ball blanket (20%) and the fibre blanket (16%). The weight of the WB increased with increasing age, up to the adult ages.

Table 1. Participant’s demographics and type of weighted blanket.

Diagnoses

Some individuals had multiple diagnoses registered and thus the number and percentages add up to more than 4092 people and 100%, respectively. The most common diagnosis was attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (48.1%) and anxiety (40.9%) followed by autism (32.2%), and depression 27.1% (). The diagnoses varied across the age groups. In the youngest age groups (0–17 years) autism and ADHD were more frequent, while in young adults (18–24 years) anxiety was the most common diagnosis followed by ADHD. In the middle-aged group (25–65 years), anxiety and depression were the most common diagnoses. In the elderly group (65 years and older), dementia (67.1%) was the most common diagnosis, followed by anxiety (35.7%). Overall, there were more men diagnosed with ADHD and/or autism, while depression was the most common diagnosis among women. The diagnoses of insomnia were registered in the patient chart for 27% of the study population.

Return of WB

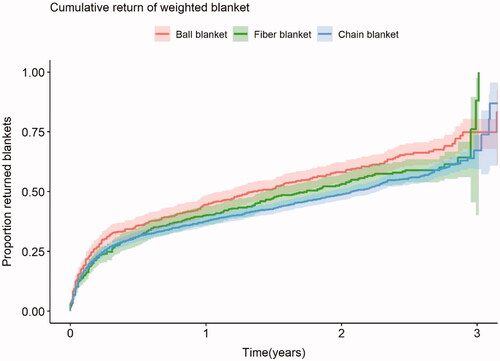

The mean follow-up time was 2.1 years. The longest follow-up period for a WB user was 3.7 years. During the follow-up period, a total of 2291 blankets were returned and the median time from delivery to return was significantly longer for chain blankets (2.3 years) compared to fibre and ball blankets, 1.8 and 1.55 years, respectively ().

Figure 1. The process of prescribing a weighted blanket with the three main actors, patient, caregiver, and medical aid centre which is the provider of the weighted blankets.

Ball blankets, individuals in the age group 0–6 years and over 65 years and WBs with lighter weights were associated with shorter time to return (). For the ball blankets, the likelihood of return was 23% greater than for the chain blankets. Individuals aged 0–6 years had a 37% higher likelihood of return than the reference group (13–17 years), and those 65 years and older had 3.5 times higher likelihood of return than the reference group. For every kilo heavier the blanket was, the likelihood of return was reduced by 3%. Depression and ADHD were associated with shorter time to return, while dementia and organic mental disorders, anxiety and intellectual disability (ID) were associated with longer time to return. Individuals diagnosed with ADHD had an 18% higher likelihood of return than those without ADHD. Individuals with depression had a 13% higher likelihood of return than those without depression. Individuals with anxiety had an 11% lower likelihood of return than those without anxiety, and individuals with intellectual disabilities had a 19% lower likelihood of return of the WB ().

Table 2. Cox regression hazard ratios, presented with 95% confidence intervals and p-values, modelling the association between the time to return of the WB and sex, age, previous diagnoses, type of WB and weight of WB.

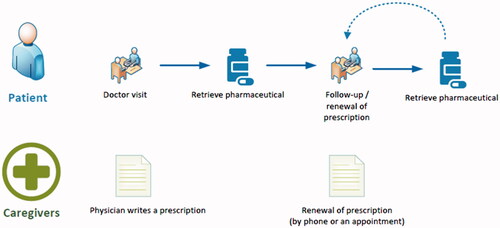

Cost of prescription processes

The prescription process of WB and sleep medication is presented in and . The prescription process for WB was found to be longer and to contain considerably more steps than the sleep medication prescription process. The WB process also involved more visits to the caregiver (approximately 6–7 visits), compared to the medication prescription process (approximately 2 visits). Not only does the WB process include more visits for the patients; each visit in relation to the prescription of WB involved more steps and time spent by the caregivers than that of medication prescription. Only including the time spent for the OT in the most common scenario for WB, the total time amounts to just under 5 h, compared to 45 min spent by the physician for medication. The actual cost for the WB themselves was lower than that of most other steps in the process; an hour spent by either an OT or a physician was more costly than the monthly cost of a WB. The time from first visit to delivery of the WB has been estimated to be between 3 and 12 weeks, depending on the number of intermediate steps.

The total cost for all the prescribed WBs in this study was estimated to reach about €1.44 million. The average cost for the prescription of a WB with a use time of 6 months, was calculated at just below €190, compared with sleep medications for the same period that was calculated to be slightly below €86.

The total average cost of a WB that was kept for the median time to return (2.1 years), was about €352. For sleep medication, the total average cost for the same time was just below €124. Hence it was possible to prescribe sleep medication to almost three individuals for every prescribed WB. The main cause for the higher costs for the WB is the more complex and lengthy prescription process, as indicated by more than 50% of the total costs occurring within the first 6 months after referral.

Discussion

The main findings of this study were that individuals diagnosed with dementia, anxiety, autism and ID had a significantly longer time until return of the WB than others. In addition, individuals younger than six and older than 65 years of age returned the WB sooner. The cost evaluation showed that the prescription process for WBs was longer and had a higher cost than that of prescribing sleep medication.

Prescription pattern and diagnoses

The findings support the clinical experience that individuals of all ages are seeking treatment for sleep difficulties, and there was a heterogeneity in diagnoses between the different age groups. It was not surprising that ADHD represented the largest group with 48%, since this diagnosis is associated with poor sleep as well as with other comorbidities such as depression that can also cause insomnia [Citation8]. This study also supports previous findings that there is a slight overrepresentation of women, among those seeking help for insomnia [Citation2]. Only 27% had insomnia as a registered diagnosis, which might be explained by the fact that its uncommon for people to seek help primarily for insomnia, since other problems such as ADHD, chronic pain or depression are the disorders and symptoms that individuals seek help for. The term insomnia is also open to debate since it can refer to both a transient sleep disorder and a clinical syndrome [Citation8], which might explain why there were relatively few individuals with insomnia as a main diagnosis in this study.

A systematic review by Eron et al. [Citation25] discussed the use of WBs and the effects on sleep in patients with insomnia compared to anxiety. They claim that WBs were more effective for the anxiety group, while in the insomnia group there were less effects, although there were many positive reports from the patients that were not seen in the objective measurements. In this study, individuals with anxiety diagnoses kept their WB for a significantly longer time than others. This might suggest a longer use time and positive effect of WBs in this group.

Characterization of those who return their blankets

The youngest and oldest individuals, as well as individuals diagnosed with ADHD and depression, had an increased likelihood of returning the WB earlier than others. The return of a WB may have many different explanations, but as the reason for return was not registered in this study it is not known whether the WB was returned due to dissatisfaction or satisfaction. Both reasons might be plausible, for instance, the former when little effect was experienced, and the latter if the sleep difficulty had been resolved. There is clinical experience indicating that individuals tend to stop using technical aids without returning them. Sometimes the individual may be unable to return the aid themself – due to functional limitations and sometimes the aid may be kept as security lest the sleep difficulties should return. Therefore, the prescription process dictates a thorough assessment and a close follow up of prescribed aids and their effect on the problem. Validated outcome measures for assessing the effects are often used clinically [Citation34], but none of these were used systematically in this study for example the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI), Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) or the Patient-Reported Outcome Information System (PROMIS) [Citation35–37]. It is a known fact that technical aids can be prescribed which then do not have sufficient effect for the individual intended [Citation34]. Lindstedt [Citation12] examined adults with ADHD who were introduced to different cognitive assistive technologies including WBs. Although the study group was small, with 19 individuals, there was a high return rate of 60% of the aids. Some of the early returns were explained by malfunctioning of the device, but also the fact that the need for the device ceased to exist, and sometimes because other treatments were found to be more effective [Citation12]. Steingrímsson et al. [Citation29] investigated changes in sleep medication usage after WB prescription as an indicator for the benefit of the WB. Findings showed no increase in medicine usage while using WB and a decrease in certain age groups such as for the younger adult population [Citation29].

The younger and older participants were found to return the WB earlier than others. For the younger age groups, returning the WB might have to do with the fact that sleep difficulties may sometimes be a developmental issue and thus resolve themselves naturally with increasing age [Citation1]. Improved sleep might also be associated with other components such as getting increased support from the healthcare system, going through the prescription process with continuous follow-up, puts focus on everyday activities. This support might also include individual advices and tailor-made sleep education, thus probably having a better chance to obtain a better sleep pattern. The elderly participants were a group with higher likelihood of returning their WB. The causes for this are largely unknown. But there may be a few possible reasons. Elderly individuals might have a long-established poor sleep routine and health care providers might not always devote their full attention to underlying causes of insomnia, since there might be a misconception that poor sleep has to do with age itself [Citation38]. Another reason for early return might be that the prescription process could have been initiated by someone other than the elderly person with insomnia, to try all options to improve sleep. On the other hand, individuals with dementia were found to keep their WB for a longer time. Dementia is a diagnosis associated with a known degenerative process to the areas that modulate sleep [Citation39], thus maybe being influenced by the WB. There are also reports that elderly people who suffer from dementia may find relief from deep pressure touch [Citation9,Citation40]. An alternative reason for longer use time among people with dementia and people with ID could be a speculation about the living arrangements for some people in these two groups. This study did not retrieve any data on living arrangements for the participants, but there are reasons to believe that some individuals with Dementia or ID live in group homes or other living arrangements where there might be staff who do not feel an obligation to manage the return of WBs. It could also be difficult for some individuals to communicate what they feel about the WB [Citation39,Citation41].

The type of blanket also played a role on the return rate, with ball blankets being associated with higher likelihood of return. The ball blanket is believed to have more pressure points than the other two types of WB which provide more of a solid feeling. Relating to theory the many plastic balls might give a sense of a lighter touch although they contain the same total weight as the others, people with hypersensitivity might experience this as a disadvantage [Citation42]. Comments have been made that the different types of WBs make disturbing noises and can be perceived as to warm which might have a disruptive effect on sleep if the person have a diagnosis involving sensory difficulties. Assumptions have been made that the different types of WB make noises and can be perceived as warmer or colder which can be disturbing when having diagnoses involving sensory difficulties. The heavier blankets were kept longer than the lighter ones, which is consistent with findings of previous studies [Citation9,Citation21]. The topic of WB weight has been discussed in literature, and often 10% of the person’s bodyweight is recommended as the optimal weight of the blanket [Citation9,Citation19,Citation21,Citation39,Citation43]. The ground rule is that the person using the WB should be able to remove it by themselves, with their own hands [Citation43].

Cost analysis

The cost analysis showed that the prescription process and use of the WB was almost three times more expensive than the prescription and use of sleep medications. The costs were due mainly to personnel costs and less to the material. It is likely that the close work that the OT does with the patient will provide added value for the patient in the form of, for example, personal contact, encouragement and comfort that cannot be accounted for in a strict economic analysis model. When considering the whole process of receiving a WB, it may be considered time-consuming both for the individual, and for the health care providers. It might be worthwhile revising this process to make it more efficient but also be more precise in the screening procedure to better identify those with the greatest need of a WB.

It was interesting to find that the cost for the first 6 months use of the WB (which includes the prescription process) constituted about half (€180/WB) of the total cost of a median use time of just over 2 years for a WB (€352/WB). This implies that it was the prescribing of the WB that was driving the costs for the WB, compared to prescribing and using sleep medicine, given a time use of 6 months. Therefore, the prescription process might need to be revised and systemized to a greater degree within the region, to reduce the costs. It also highlights the importance of both starting and ending the prescription process with patients with a higher likelihood of a longer use time and a possible benefit on the initial sleep problems. This study did not obtain data to be able to investigate and compare the cost-effectiveness of WB and pharmaceuticals on insomnia.

Methodological considerations

One aspect that was not accounted for in this study was how many individuals received help from an OT that did not result in a WB. This group were perhaps helped into better sleeping routines, hence improved sleep patterns from sleep education, individual advice, and other types of OT interventions [Citation1]. One major limitation of this study was that there was no outcome measure that evaluated the actual changes in sleep status for each participant. We cannot be sure if those who received the prescribed medicine, or the WB, used them. The quantitative design of this study does not answer questions concerning the reasons for returning the WB, nor why many of the participants kept both the WB and the sleep medicine. This study did not reveal whether the sleep problems were primary or secondary, as only cross-sectional retrievals from the health care registers were made. The strength of using register data in a study in this way, was that all available data was used in the analyses. This kind of study will also be a way for the healthcare system providers to reflect on the types of data that are entered into the administrative systems and how the data can be used to bring more knowledge about the health care delivered.

Clinical implications

Sleep is a basic human need, with a major impact on our health. The findings from this study emphasize the importance of thorough and systematic assessment and follow-up of the individual sleep difficulties and their impact on daily functioning, as well the reasons for prescribing a WB. Certain patient groups and age groups had an increased likelihood of early return of the WB, which may indicate a low benefit of WB for these groups.

OTs focus mainly on activity and occupational balance for the individual [Citation44,Citation45], and therefore it is very important to consider the individual sleep difficulties within a context, since several different interventions might be required to improve sleep function, depending on individual and relevant contextual factors [Citation6,Citation14,Citation45]. It may be possible that the individuals who received a WB also received melatonin, sleep education, or other activities, for example physical exercise, for their sleep difficulties [Citation12]. To reach an optimal use of a technical aid such as the WB, systematic and structured support by professionals trained in handling these types of problems needs to be integrated into the process.

This study contributes to new and increased knowledge about the prescription process and use of WBs, as well as providing an understanding of the use of health data registers. An important aspect is the lack of standardized outcome measurements used in a systematic way, which should be considered as an area for improvement. In order to use the economic recourses wisely, the OT should be able to show which type of treatment has proven to be effective by being more diligent in using validated assessments and communicating them in existing administrative and quality registers.

The prescription process of a WB was more costly than the process for prescribing sleep medications and the personnel costs were the main factor in the cost differences. These costs could be addressed by investigating the health care chain and process, but perhaps more importantly by investigating the costs of WB in comparison with the saved costs for society in total, as the cost to society for loss of sleep has been estimated to be up to €300 million in Sweden [Citation46].

Further studies

More research is needed to increase the knowledge of the effects of WB on sleep quality and quantity. Previous studies on WBs have had a focus on the younger population and there is, therefore, a lack of research on elderly groups, as well as in those with dementia. Both clinical and cost-effectiveness studies should be established with in-depth assessments and analysis using valid and reliable outcome measures, such as clinical assessments of sleep and functional outcomes. Both laboratory studies and controlled intervention studies could be designed for this purpose. A strict economic model cannot give the full picture, and the recommendation for future research would be to evaluate the effects of these two treatments through clinical studies, to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of WBs.

Acknowledgements

This study was performed with VGR as head of research. The authors represent various parts of the VGR Health care organization and the Centre Registration Västra Götaland with invaluable assistance from Anneli Karlsmo at Gothia Forum, who served as a highly appreciated project leader. Acknowledgement is also given to Bo Zetterlund and Jan Kilhamn who supported the initiation and implementation of this study.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest, and have no financial or other interests in companies, producing, distributing, marketing or selling WBs.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Green A, Brown C. editors. An occupational therapist's guide to sleep and sleep problems. London: Jessica Kingsley; 2015.

- Chattu VK, Manzar M, Kumary S, et al. The global problem of insufficient sleep and its serious public health implications. Healthcare. 2018;7(1):1.

- Cunnington D, Junge MF, Fernando AT. Insomnia: prevalence, consequences and effective treatment. Med J of Australia. 2013;199(8):36–40.

- Daley M, Morin CM, LeBlanc M, et al. The economic burden of insomnia: direct and indirect costs for individuals with insomnia syndrome, insomnia symptoms, and good sleepers. Sleep. 2009;32(1):55–64.

- Cortese S, Brown TE, Corkum P, et al. Assessment and management of sleep problems in youths with Attention-Deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2013;52(8):784–796.

- Ho E, Siu A. Occupational therapy practice in sleep management: a review of conceptual models and research evidence. Occup Ther Int. 2018;2018:8637498–8637412.

- Tester NJ, Foss JJ. Sleep as an occupational need. Am J Occup Ther. 2018;72(1):7201347010p1–7201347010p4.

- Garland S, Varga I, Grandner M, et al. Treating insomnia in patients with comorbid psychiatric disorders: a focused review. Can Psychol Assoc. 2018;59(2):176–186.

- Ackerley R, Olausson H, Badre G. Positive effects of a weighted blanket on insomnia. J Sleep Med Disord. 2015;2:1022.

- Hafner M, Stepanek M, Taylor J, et al. Why sleep matters & the economic costs of insufficient sleep: a cross-country comparative analysis. Rand Health Q. 2017;6(4):11.

- Hillman D, Mitchell S, Streatfeild J, et al. The economic cost of inadequate sleep. Sleep. 2018;41(8):1–13.

- Lindstedt H, Umb-Carlsson O. Cognitive assistive technology and professional support in everyday life for adults with ADHD. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2013;8(5):402–408.

- The national board of health and welfare. [Internet]. 2020. Available from: http://socialstyrelsen.se/en/

- Hetta J, Axelsson S, Eckerlund I. Behandling av sömnbesvär hos vuxna. Lakartidningen. 2010;107(44):2712–2714.

- Cheung JMY, Ji XW, Morin CM. Cognitive behavioral therapies for insomnia and hypnotic medications: considerations and controversies. Sleep Med Clin. 2019;14(2):253–265.

- Bragg S, Benich JJ, Christian N, et al. Updates in insomnia diagnosis and treatment. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2019;54(4–5):275–289.

- Reynolds S, Lane SJ, Mullen B. Effects of deep pressure stimulation on physiological arousal. Am J Occup Ther. 2015;69(3):1–5.

- Chen HY, Yang H, Chi HJ, et al. Physiological effects of deep touch pressure on anxiety alleviation: the weighted blanket approach. J Med Biol Eng. 2013;33(5):463–470.

- Grandin T. Calming effects of deep touch pressure in patients with autistic disorder, college students, and animals. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 1992;2(1):63–72.

- The national board of health and welfare. [Internet]. 2022. Available from: https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/globalassets/sharepoint-dokument/artikelkatalog/ovrigt/2021-12-7673.pdf

- Mullen B, Champagne T, Krishnamurty S, et al. Exploring the safety and therapeutic effects of deep pressure stimulation using a weighted blanket. Occup Ther Ment Health. 2008;24(1):65–89.

- Champagne T, Mullen B, Dickson D, et al. Evaluating the safety and effectiveness of the weighted blanket with adults during an inpatient mental health hospitalization. Occup Ther Ment Health. 2015;31(3):211–233.

- Danoff-Burg S, Rus HM, Cruz Martir L, et al. Worth the weight: weighted blanket improves sleep and increases relaxation. Sleep. 2020;43:A460–A460.

- Gringras P, Green D, Wright B, et al. Weighted blankets and sleep in autistic children-a randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2014;134(2):298–306.

- Eron K, Kohnert L, Watters A, et al. Weighted blanket use: a systematic review. Am J Occup Ther. 2020;74(2):7402205010p1–7402205010p14.

- Summe V, Baker RB, Eichel MM. Safety, feasibility, and effectiveness of weighted blankets in the care of infants with neonatal abstinence syndrome: a crossover randomized controlled trial. Adv Neonatal Care. 2020;20(5):384–391.

- Ekholm B, Spulber S, Adler M. A randomized controlled study of weighted chain blankets for insomnia in psychiatric disorders. J Clin Sleep Med. 2020;16(9):1567–1577.

- Bolic Baric V, Skuthälla S, Pettersson M, et al. The effectiveness of weighted blankets on sleep and everyday activities – a retrospective follow-up study of children and adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and/or autism spectrum disorder. Scand J Occuo Ther. 2021.

- Steingrímsson S, Odéus E, Cederlund M, et al. Weighted blanket and sleep medication use among adults with psychiatric diagnosis - a population-based register study. Nord J Psychiatry. 2022;76(1):29–36.

- Regionfakta. [internet] 2020. Available from: http://www.regionfakta.com/vastra-gotalands-lan/in-english-/population1/population/

- Green S, Lambert R. A systematic review of health economic evaluations in occupational therapy. Br J Occup Ther. 2017;80(1):5–19.

- Kaplan RS, Anderson SR. 2003. Time-driven activity-based costing. DOI:10.2139/ssrn.485443

- The Swedish association of local authorities and regions (SALAR). [Internet] 2020-12-15. 2019. Available from: https://skr.se/download/18.6d040f28179a309a49435680/1622458002768/Arbetsgivaravgifter-Lt-Reg-2005%E2%80%932021.xlsx

- Fuhrer MJ. Assistive technology outcomes research: challenges met and yet unmet. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;80(7):528–535.

- Morin CM, Belleville G, Bélanger L, et al. The insomnia severity index: psychometric indicators to detect insomnia cases and evaluate treatment response. Sleep. 2011;34(5):601–608.

- Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Monk TH, et al. The pittsburgh sleep quality index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28(2):193–213.

- Leung YW, Brown C, Cosio AP, et al. Feasibility and diagnostic accuracy of the Patient-Reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) item banks for routine surveillance of sleep and fatigue problems in ambulatory cancer care. Cancer. 2016;122(18):2906–2917.

- Boswell J, Thai J, Brown C. Older adults’sleep. In Green A, Brown C, editors. Sleep and sleep problems. London: Jessica Kingsley; 2015. p. 185–206.

- MacQueen K, Boswell J, Thai J. Sleep problems in dementia. In Green A, Brown C, editors. Sleep and sleep problems. London: Jessica Kingsley; 2015. p. 273–280.

- Hjort Telhede E, Arvidsson S, Karlsson S. Nursing staff's experiences of how weighted blankets influence resident’s in nursing homes expressions of health. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-Being. 2022;17(1):2009203.

- Nakopoulou E, Wale M, Wood E. Sleep problems in people with learning disabilities. In Green A, Brown C, editors. Sleep and sleep problems. London: Jessica Kingsley; 2015. p. 207–230.

- Bundy AC, Lane SJ. Sensory integration theory and practice. 3rd ed. Philadelphia (PA): F.A Davis Company; 2019.

- Parker E, Koscinski C. The weighted blanket guide. London: Jessica Kingsley; 2016.

- Kielhofner G. Model of human occupation: theory and application. 4. ed. ed. Baltimore (MD): Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007.

- Magnusson L, Håkansson C, Brandt S, et al. Occupational balance and sleep among women. Scand J Occup Ther. 2021;28(8):643–651.

- Laestadius. P. SKR och tyngdtäckena- en lektion i silobudgetering. Swedish MedTech [internet] [cited 2020 Oct 14]. Available from: https://www.medtechmagazine.se/article/view/744924/skr_och_tyngdtackena_en_lektion_i_silobudgetering