Abstract

Background

Reablement services are intended to make a difference in the daily lives of older adults. Outcomes are often described in terms of independence, improving quality of life, improving ADL functioning, or reducing services. However, little is known if the older adults or next-of-kin experience these outcomes when talking about participating in reablement services.

Aim

This study aims to explore how older adults, next-of-kin, and professionals narrate the reablement recipients’ possible outcomes as gains and changes in everyday life during and after the reablement period.

Materials and methods

This meta-synthesis included 13 studies. Data were analyzed with a meta-ethnographic approach, searching for overarching metaphors, in three stages.

Results

The metaphor ‘the jigsaw puzzle of activities for mastering daily life again’ illustrates that re-assembling everyday life after reablement is not a straightforward process of gains and changes but includes several daily activities that must be organized and fit together. To obtain a deeper understanding of the participants’ gains, and changes after reablement, we use the theoretical framework of ‘doing, being, becoming, and belonging’.

Conclusion

The findings indicate the complexity of reablement services as well as the need for a holistic approach.

Significance

Outcome measures should be meaningful for reablement recipients.

Background

Reablement is a relatively new health care service for older adults that are at risk for functional decline and is intended to make a difference in an older adult’s everyday life functioning [Citation1,Citation2]. The concept of reablement is not consistently defined, and different concepts, such as everyday rehabilitation and restorative care have been used interchangeably [Citation3–5]. In this study, we use the definition from a recent Delphi study [Citation6] involving experts from 11 different countries and initiated by the ReAble research network: ‘Reablement is a person-centred, holistic approach that aims to enhance an individual’s physical and/or other functioning, to increase or maintain their independence in meaningful activities of daily living at their place of residence and to reduce their need for long-term services. Reablement consists of multiple visits and is delivered by a trained and coordinated interdisciplinary team. The approach includes an initial comprehensive assessment followed by regular reassessments and the development of goal-oriented support plans. Reablement supports an individual to achieve their goals, if applicable, through participation in daily activities, home modifications, and assistive devices as well as the involvement of their social network. Reablement is an inclusive approach irrespective of age, capacity, diagnosis or setting’ [Citation6, p. 11]. This definition has guided the research process and the discussion of the results.

Reablement service outcomes have shown positive results regarding cost-effectiveness for the service as well as changes in functioning for the older adult, and service utilization [Citation5,Citation7–11]. However, evidence also shows contradictory results. Legg, Gladman, Drummond, and Davidson [Citation12] state in their review that there is a lack of evidence of positive outcomes due to challenges regarding how to evaluate reablement interventions. Outcome measures used to evaluate reablement interventions are often used to measure ADL functioning, physical functioning, independence, change in the number of services provided, increasing the length of stay at home, and economic gains for the municipality. According to Glendinning et al. [Citation13] naming relevant reablement outcomes have both practical and conceptual challenges which remain to be explored.

Even though reablement is intended for people of all ages, older adults appear to be the main target group as they are well-represented in the current reablement literature. However, one may question if reablement outcome measures are applicable for all age groups. Thus, older adults’ experiences of gains and changes after their participation in reablement services are of interest to explore. According to the suggested definition of reablement, person-centeredness is central in reablement services. It is therefore important to capture the perceptions of the gains and changes of the reablement recipient as well as the professionals, and the older adult’s next-of-kin. With the increasing attention in taking the clients’ perspectives regarding health policy design and clinical practice into consideration [Citation14], there is an interest to further explore how older adults narrate their reablement outcomes. Furthermore, assessments that include older adults’ perspectives will allow more effective services targeting their expressed needs [Citation15].

Reablement services are grounded in the premise that service providers need to establish a collaborative process with the service recipient, allowing reablement to be about the daily life of the service recipient. In several countries, the question directed to the service recipient ‘What matters to you?’ is a starting point, occurring in the first meeting between the older adult and the professionals. Thus, to emphasize the individuals’ needs, reablement services should be grounded in the social and cultural life of the recipient, including their life history. This way, reablement recipients will have the possibility to do what they want and need, which is essential to reablement success [Citation13,Citation16]. This indicates a potential difference between the aim of reablement services based on measuring effects of for example dependence/independence, compared to how the intervention is grounded in the individual’s opportunity to decide and achieve what exactly ‘matters to her or him’.

Several recent qualitative studies, deal with the experiences of reablement from the perspective of older adults, the next-of-kin, and professionals, aiming at exploring the broader experience of participation in reablement services [Citation17–20]. However, these studies do not specifically focus on the gains or changes for the older recipient. Thus, to develop knowledge regarding the older adults’ perceptions of gains and changes, we decided to perform a meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. Findings from these types of studies have the potential to make novel contributions to the knowledge base and thus inform both policy and clinical practice [Citation14]. To add yet another perspective, we also want to include how next-of-kin and the professional's experience and describe possible outcomes as gains and changes for the reablement recipients. The study aims to explore how older adults, next-of-kin, and professionals narrate the reablement recipients’ possible gains and changes in everyday life during and after the reablement period.

Method

A qualitative meta-synthesis involves a systematic way of collecting, analyzing, and interpreting qualitative findings across multiple primary research studies, to produce an overarching new insight into a phenomenon [Citation21–23]. Different approaches have been suggested to synthesize qualitative research [Citation24]. For the present study, a meta-ethnographic approach was chosen. Meta-ethnography can be used as a framework for translating findings of various studies about similar topics into a shared language, using systematic comparison and then developing a metaphor [Citation22,Citation25]. Thus, the present study is a meta-ethnography that searched for overarching metaphors that captured the common findings from the included articles.

The systematic search processes

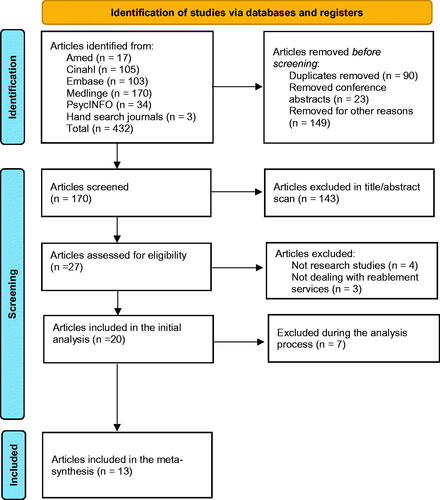

The research group (A.B., K.V., M.H., S.M., L.G., and K.M.H) decided on the inclusion criteria for the search process. The inclusion criteria were (1) qualitative or mixed-method studies, (2) studies dealing with older adults’, next-of-kin’, and staffs’ perceptions of recipients’ gains and changes of reablement services. Since reablement is a relatively new concept, we did not have any criteria regarding time limits for the search. A systematic search was first performed in September 2018. The search was performed by the last author (K.M.H.) and a librarian, using the electronic databases Cinahl, Amed, Embase, Medline, and PsycInfo. PubMed was excluded because the version of OVID Medline the University College is using has the same content, but the interface of OVID is better for systematic searching. The following key concepts in each database were used; ‘reable’ OR ‘re-able’, ‘restorative care’ OR ‘restorative rehabilitation’, ‘reactivation and care’ OR ‘reactivation and rehabilitation’. After removing duplications, 170 titles and abstracts were screened in the fall of 2018, and 143 were excluded. Twenty-seven full-text articles were assessed for eligibility and of these seven were excluded for reasons. The search was run again in February 2020, new references were screened, however, no new articles were included. The complete search strategy is presented in a flow diagram ().

Figure 1. Search strategy. For more information visit http://www.prisma-statement.org/.

Screening process

The authors, divided into pairs, received a set of titles and abstracts for screening. All titles and abstracts were independently read and then discussed by the pair. All pairs had the main responsibility for one set of articles and were then co-reviewers in another set. Two screening questions were put forth to the articles; Does the article report findings of research involving gains and changes for the older reablement recipient, and are the results narrated by older adults, next-of-kin, or professionals? [Citation27,Citation28]. Additionally, questions were posed, such as if the older person was living at home, and receiving services supporting meaningful daily activities, in line with the definition of reablement.

Analysis

All meta-synthesis methods represent an inductive way of comparing, contrasting, and translating the original authors’ understanding of key metaphors, phrases, ideas, concepts, and findings across studies. Data from the included studies is thus developed beyond the original study, aiming at developing new knowledge based on the original studies [Citation22]. In this synthesis, we followed the recommendations regarding meta-ethnography [Citation22,Citation23,Citation29], since this method gave the opportunity to explore and identify patterns among the studies’ results, and the current ideas deconstructed into a deeper theoretical understanding of the research question. This analyzation process allowed for further interpretations of the original articles [Citation22]. The analysis was conducted in three stages, also referred to as constructs. In the first order construct, extracts from the original studies were retrieved, thus constituting the raw data from the original studies. The second order construct consisted of the raw data grouped into constructs that captured the aim of the current study; gains and changes for the older recipients. Finally, the third-order construct involved the interpretation of key concepts and findings across the studies [Citation29].

First order construct

The full-text articles were divided between the reviewing teams’ members and the analysis was performed according to the recommendations of Malterud [Citation29]. First, all articles were read and re-read with a special focus on the findings and how the findings described the experience of gains and changes during and after the reablement period. By reading the articles in full text, the authors searched for text elements that captured the aim of the current study [Citation29]. These text extracts are considered as empirical data. First-order constructs also imply how the participants, for example, the older recipients, construct their own understandings and meanings related to the phenomenon under discussion. In the first-order construct, we determined how the studies were related to identify a second-order construct. During this in-depth reading phase, we discovered that the findings in seven of the studies did not contain text regarding gains and changes for the reablement recipients, thus these were excluded and consequently, no articles from next-of-kin’s perspectives were analyzed in the second order construct (). Consequently, the analysis continued with thirteen articles ().

Table 1. Studies included in the metasynthesis.

Second order construct

The identified extracted text and relevant quotes from the primary studies were put in a matrix with the headings ‘how do the findings describe the older adults’ and staffs’/professionals’ perceptions of ‘possible gains and changes for the reablement recipients during and after the reablement period’. The authors used the matrix in an ongoing analysis process where concepts and categories were discussed, added, and deleted among the authors and where ‘new’ findings emerged. A second-order construct also includes research findings based on the author's interpretation of the data. All the findings and overall themes were discussed among the authors to determine how they were related to each other in the way they had been presented by the original authors and how they reflected the theoretical framework.

Third order construct

In the third-order construct phase, the authors created metaphors that captured and connected the findings from the primary text [Citation29,Citation30]. In this analytic process, the authors compared, contrasted, and translated the concepts, and from these discussions, a common metaphor was constructed. The metaphor of ‘The jigsaw puzzle of activities for mastering daily life again’ was chosen to illustrate that re-assembling everyday life during and after reablement is not a straightforward process of gains and changes but includes several daily activities that must be organized and fit together to restore daily life as the service recipient anticipates. The metaphor captures the overall descriptions of both the older adults and the professionals regarding how the reablement recipient perceives reablement (see ). In the findings, the reablement recipients talked about being able to perform daily activities safely and the ability to oversee household chores. Furthermore, when the reablement recipients were more concerned with being social and spending time with friends and family, the professionals focussed more on executing tasks and activities that would lead to independence.

Table 2. Examples of gains and changes.

The metaphor of an assembled jigsaw puzzle is used to illustrate a meaningful everyday life. During our reflection on the emerging metaphor, we saw how this encompassed a person’s doing, being, becoming, and belonging [Citation31–33]. When the jigsaw puzzle, or everyday life, for any reason, is interrupted, the person must start a process of reconstructing the puzzle of everyday life including regaining performance of everyday activities. The older adult’s gains and changes representing the outcomes of the reablement process can be seen in the jigsaw puzzle, where the puzzle pieces of doing, being, becoming, and belonging are assembled in a way that reflects the important everyday activities for the person. To obtain a deeper understanding of the participants’ gains, and changes during and after reablement, we use the theoretical framework of ‘doing, being, becoming and belonging’ [Citation31–33]. The current understanding of doing refers to the performance of activity [Citation32]. However, this goes beyond physical activity and includes the ‘doing’ as meaningful to the person [Citation31]. Being can be described as ‘the sense of who someone is as an occupational and human being and rest on inward awareness of your existence and is necessary for engaging in occupation’ [Citation32, p. 237]. Becoming reflects the person’s self-concept, self-creation, and desire to experience competence, efficacy, and consequences [Citation31]. Belonging can be described as the connectedness of people to each other and the context for the occupation [Citation31].

Results

The results section consists of a description of the included studies and the results of the meta-ethnography analysis.

The sample

The thirteen included studies were published in journals dealing with primary health care, multidisciplinary health care, or caring sciences and described different aspects of experiences of reablement from older adults and health professionals. The methods used in the studies included individual interviews, focus group interviews, and video recordings of practice (). Six of the included studies were conducted in Norway [Citation18,Citation34–38], five in the United Kingdom [Citation13,Citation15,Citation39–41], one in New Zealand [Citation20], and one in Australia [Citation42] ().

Most of the included studies focussed on the perceptions of the professionals, though six studies explored and described how the older adults perceived gains and changes of reablement service [Citation15,Citation20,Citation37,Citation40–42]. Some of the studies described both the older adults and the staffs’ experiences of participating in perceived gains, changes, and outcomes of reablement service [Citation13,Citation39] (). As described in the method section, studies related to next-of-kin were excluded from the analysis, since they did not report findings related to gains and changes for the service recipients.

Findings

Doing everyday life activities—as a piece of the jigsaw puzzle

Doing includes everyday and routine activities, recovery-promoting activities, as well as choice and control regarding doing. The doing is described by the older adult in five studies [Citation13,Citation36–39]. The older adults argued that they valued the reablement team coming to their house, and this influenced how they gained self-efficacy and security to do everyday activities on their own. In a study by Hjelle et al., one woman expressed it like this:

….you are more active at home, at least for those who want to. It is activity in everything we do. I am more active at home. If I was somewhere else, it would be as they wanted, here it is the way I want to, that’s actually important for me [Citation37, p. 1586]

In another study by Glendinning et al. [Citation13], it was highlighted how users were encouraged to identify outcomes beyond self-care. One participant said:

One of my aims was to walk the dog, so they allowed him to come and see me-it was very helpful…it made all the difference in the world [Citation13, p. 59]

Doing everyday activities in a safe way may be interrupted due to illness, physical decline, or other reasons. This was expressed as:

They supported me in the beginning, so I showered myself while someone from the reablement services was here. I got a chair to sit on to be more secure when showering. They were here until I felt secure to shower myself [Citation37, p. 1586]

Doing everyday life activities at home and having a choice and control over doing, represented outcomes expressed as gains, or changes brought about by the reablement service and appreciated by the recipients. This was expressed like this: ‘I felt so frustrated at first. I just wanted to be independent. And they helped me to be able to do it myself’ [Citation39, p. 310].

Both the professionals and the home trainer supported the recipient to become confident and develop self-efficacy in the doing, as this example illustrates:

We practiced a lot with a stroke patient to cope with going to bed in a comfortable way. Then the patient told the home trainer: “Now I will try, because I’ve been practicing this, but only if you stand there and support me and help me if I cannot handle it.” She practiced several evenings, became more and more confident. She took the responsibility herself when she was ready for it [Citation38, p. 312]

Summing up, Doing everyday life activities—as a piece of the jigsaw puzzle, indicate how the older adult and the professionals are concerned about doing often performing tasks, additionally they highlight improving self-efficacy as a mean for the doing.

Being at home—as a piece of the jigsaw puzzle

After participating in the reablement service, the older adults talked about the importance of having the opportunity to be at home, do as they want to do, and as a place to be in control and have autonomy. The home is connected to privacy, identity, emotional bonds, and place attachment. Practical goals like being able to do the washing and shopping were stated. Several studies presented outcomes of being at home [Citation15,Citation34,Citation35,Citation37,Citation40–42] as illustrated in the following citation:

however, it is strange…, when you come home again … you are your own master in a way … you do what you cope with, what you want to do. When I am doing it myself here, I use the time I need … I have my time [Citation37, p. 1585].

The respondents overall indicated they were active to promote their well-being and health and fitness. They continued to enjoy activities with their family or friends and relied on them. The social aspects of being physically active, be it inside or outside their home, were also connected to being active due to well-being and health. In the study of Burton et al. [Citation42, p. 27], a 102-year-old female who lived alone stated:

….well I can’t imagine not [being physically active], you hear of people that are lonely and miserable, is it because they won’t exert themselves, even if you walk and smile at somebody, I grin from ear to ear and whether they smile back it doesn’t matter… I feel so much better when I’m active than when I’m sitting around.

Some older adults expressed distress at being confined to their house and requested help with social activities. One woman said her request for help with social activities was ignored. She said: ‘Oh, we’ll look into that’ is their favourite. I want to do something. I’m not dead. I’m only deaf’ [Citation41, p. 588].

Summing up, being at home—as a piece of the jigsaw puzzle, illustrates how important it is for older adults to have the opportunity to practice everyday activities in their own homes and neighbourhood. In their home, they have their identity and the opportunity to be in control of doing and mastering valued everyday activities.

Becoming the person, I want to be—as a piece of the jigsaw puzzle

People in need of reablement services usually have a period of reduced functioning and decline in performing everyday activities and participating in society. Becoming relates to hope and exploration, overcoming challenges, goalsetting and determination, growth, and development, and was highlighted in several of the included studies [Citation36,Citation38,Citation41]. Becoming active again, participating in more activities, and engaging or re-engaging in daily life was described in three studies [Citation13,Citation37,Citation41]. Some older adults had a strong desire to regain former independence, getting out and resuming an active social life [Citation41]. Their goalsetting and determination to become the person they used to be were highlighted. One man had been encouraged to identify goals that were meaningful to him, and this motivated him to recover his ability to walk to the nearby place where his wife died [Citation41].

Becoming active was also related to being active in one’s own home, context, and with family and friends [Citation15,Citation41]. One participant in the study of Wilde and Glendinning [Citation41] expressed that the reablement service focussed mostly on personal activities of daily living, and not the promotion of independence, as he understood it. He said: ‘If they are helping me, then how can I be independent’ [Citation41, p. 586]. However, during the reablement process, it was a shift in emphasis to doing more for themselves. In the study of Trappes-Lomax and Hawton [Citation15], some older adults experienced mixed preparations for discharge when staying in community hospitals. One recipient adult said: ‘No hesitations. Pleased to be home. Yes – like a duck in water’. Others were much more anxious: ‘Oh I felt very frightened. I didn’t know how it was going to go’ [Citation15, p. 188].

Summing up, becoming the person I want to be—as a piece of the jigsaw puzzle, illustrates how important it is for an older adult to have the opportunity to practice everyday activities in their own context. This gives opportunities to gain confidence and function to practice and master everyday activities, to become the person, he/she wants to be, performing valued everyday activities in his/her context both at home and outside the home.

Belonging in own context—as a piece of the jigsaw puzzle

And finally, belonging is about connecting with others, inclusion and integration, affiliation and belonging. Belonging, another piece of the puzzle, can be understood as a sense of connectedness to others, places, cultures, etc. This was described in several studies [Citation37,Citation41,Citation42]. In the study of Burton et al. [Citation42], the respondents indicated they were active to promote their well-being and health and fitness, gained enjoyment, or liked the social aspects of being physically active, be it inside or outside their home. They continued to enjoy activities with their family or friends and rely on them, especially the accompanying social interaction, as this quote illustrates:

Oh yes she’s wonderful she’s my carer [daughter], wherever she goes she asks me if I want to go and I never say no, it’s either in the car or walking down the street or to see the family or something, we’re lucky that the family live reasonably close by, so we see a lot of them, very lucky (102-year-old female HIP active) [Citation42, p. 28].

In the study of Wilde and Glendinning [Citation41], the reablement service was reported to be much less concerned with social needs and activities also by the professionals. These activities were considered very important by many older adults, who expressed that they were frustrated that the reablement service did not offer help with this outcome.

Summing up, belonging in one’s own context—as a piece of the jigsaw puzzle, illustrates how belonging to other people, context, and participating in social life are important for gains, changes, and outcomes of the reablement process. Belonging to social networks is an important piece of the jigsaw puzzle to reassemble the pieces together again. The jigsaw metaphor indicates the complexity of reablement services as well as the need for a holistic approach. In other words, having all the pieces in the puzzle is necessary for reconstructing activities in everyday life.

The result section of this paper illuminates the metaphor of the ‘The jigsaw puzzle of activities for mastering daily life again’.

Discussion

This study explored how older adults and professionals narrate the possible gains and changes in everyday life during, and after a reablement period. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first meta-synthesis done regarding this topic, and is thus difficult to compare our findings with previous syntheses. However, our findings appear to be in accordance with a study published by Östlund et al. [Citation43], and their description of older adults' wishes to be more autonomous and independent from services by participating in reablement interventions.

The main finding of our analysis was the ‘jigsaw metaphor’ that indicates the complexity of reablement services as well as the need for a holistic approach or having all the pieces in place to be able to see the whole picture. This may have some implications for the possibilities to measure effects or possible changes of this kind of service.

The discussion is in three parts; Reflections regarding the gains and changes related to common outcome measurements, the definition of reablement in relation to the findings, and the possibility to measure the puzzle of daily life.

Reflections regarding the gains and changes, related to common outcome measurements in reablement services

Our findings indicated that the older adults were concerned with the doing, or performance of skills in ADL’s. This is in line with Tessiers et al. [Citation8] finding that the most common outcome measures in reablement are functional independence measures in P-ADL and I-ADL together with mobility measures. In this case, one may say that the gains of managing ADL are in line with the outcome measures used in reablement. However, the findings from qualitative studies show a broader picture since being secure or developing self-efficacy were changed that the older adults expressed. The subjective experiences from the user regarding improving the performance of daily activities seem to go beyond the execution of tasks like showering. These findings from qualitative studies can be substantiated by the findings in a recent quantitative Swedish study [Citation44], which showed that self-determination, an aspect of autonomy, was an important factor in determining the quality of life.

Considering relevant measures in reablement, the combined findings in our meta-synthesis indicate that the older adults’ experiences executing their ADL’s must be included to both understand changes in ADL performance, and how to promote and measure ADL- performance. In other words, understanding must go beyond the dependence/independence continuum since improvements in ADL may be due to changes in self-efficacy and feelings of increased security in performance and not only improvement in physical functioning. This may have consequences for reablement services as the professionals also must focus on improving, e.g. self-efficacy and autonomy. Additionally, the findings illustrate how becoming the ‘person I was’ implied by taking part in the ordinary daily life and social activities outside the home are relevant outcomes yet to be included in existing reablement measures. However, professionals still tend to focus on traditional P-ADL measures as documented in a Swedish study by Zingmark, Evertsson, and Haak [Citation45].

The definition of reablement in relation to our findings

The definition of reablement used in this study states that reablement ‘… aims to enhance an individual’s physical functioning, to increase or maintain their independence…’ [Citation6]. One may interpret the definition as highlighting functioning, or ‘functioning to increase or maintain (their) independence’ but this is not reflected in the findings in our analysis. Both the older persons in question and the professionals are more concerned about improving physical functioning as a means to maintain daily life, and interestingly, factors, such as self-efficacy and control seem to be of greater importance, also for what can be called quality of life. Concepts of ‘functioning’ and ‘independence’ are common in relation to outcomes of health care services. However, ‘concepts’ are not neutral and by narrowing the definition to functioning and independence, both holistic and client centred aspects may disappear. Using the expression of ‘improving functioning and independence’ may govern who can be eligible to participate in reablement or not. This in turn may exclude people that have the potential to improve the puzzle of their daily life, but this cannot be measured for example as improved ADL functioning.

Is it possible to measure the puzzle of daily life?

Perhaps it is necessary to acknowledge that capturing the life-world and the processes that unfold during reablement is perhaps impossible to measure quantifiably. However, to be true to the ideal of person-centeredness, we owe honesty to the reablement recipients and perhaps should acknowledge that we do not measure the changes they experience, or we are not interested in or have the means (or measurements) to go beyond measuring the immediate execution of tasks. Reablement services need to reflect on and discuss if they want to continue with measures, such as ADL measures and improving mobility as found by Tessier [Citation8] in hopes that funding agencies will be satisfied. Tessier also questioned if the well-known ADL measurements are sensitive enough to measure change. Another possibility is to consider adding measures of self-efficacy [Citation46] and autonomy [Citation47] which may better reflect the experience of the clients. Furthermore, the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM) may be implemented as a relevant measure for reablement outcomes. COPM measures the person's perceptions of their performance and the satisfaction with the performance of needed and wanted everyday activities [Citation48]. In a randomized controlled trial, Kjerstad and Tuntland [Citation49] found that the COPM was sensitive to measure the improvement of the reablement recipients’ participation in chosen everyday activities. How social connectedness can be a part of reablement outcomes remains to be explored. Hopefully, the jigsaw metaphor can be helpful in the dialogue regarding ‘what matters to you?’. A relevant question is, for example, if this is about the doing of specific (measurable) activities or is it about belonging?

Methodical reflections

In this study, we have included studies published in scientific peer-reviewed journals. We also added three articles after hand-searching reference lists. Since all the authors are familiar with research within reablement, we assume we have not missed published studies. However, it may be a shortcoming that we did not include scientific reports, textbooks, etc. as recommended in the literature [Citation14,Citation29], and thus missed relevant papers and findings.

A meta-synthesis of qualitative studies aims for an in-depth understanding of the phenomena under exploration. The metaphor of a jigsaw puzzle captures the analogy of reablement as a process containing numerous pieces that need to fit together to make up the daily life of the older adult.

Does the use of the framework doing being, becoming, and belonging add to or hamper the findings? One may question if making use of fixed concepts narrows the findings. However, we found that these concepts facilitated our understanding of the gains and changes that were included in the jigsaw puzzle (of activities) for mastering daily life again. The purpose of a qualitative meta-synthesis, by exploring the findings from the included studies, is to take the findings a step further, beyond the original studies, and explore the findings from another perspective. In our case, this perspective was the gains and changes attributed to reablement services. Making use of the concepts of ‘doing, being, becoming, belonging’ enabled us to realize the complexity of daily life during reablement and help illustrate this with the metaphor of the jigsaw puzzle.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Gunnhild Austrheim, Head of Learning Services, Library, Western Norway University of Applied Sciences for your help and encouragement with the literature search.

Thank you to the international ReAble research group for important input in developing and revising the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Aspinal F, Glasby J, Rostgaard T, et al. New horizons: reablement-supporting older people towards independence. Age Ageing. 2016;45:574–578.

- Cochrane A, McGilloway S, Furlong M, et al. Home-care ‘re-ablement’ services for maintaining and improving older adults' functional independence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;11:1–12.

- Birkeland A, Tuntland H, Førland O, et al. Interdisciplinary collaboration in reablement – a qualitative study. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2017;10:195–203.

- Sims-Gould J, Tong CE, Wallis-Mayer L, et al. Reablement, reactivation, rehabilitation and restorative interventions with older adults in receipt of home care: a systematic review. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2017;18:653–663.

- Tuntland H, Aaslund MK, Espehaug B, et al. Reablement in community-dwelling older adults: a randomised controlled trial. BMC Geriatr. 2015;15:1–11.

- Metzelthin SF, Rostgaard T, Parsons M, et al. Development of an internationally accepted definition of reablement: a Delphi study. Ageing and Society. 2022;42:703–716.

- Parsons JGM, Sheridan N, Rouse P, et al. A randomized controlled trial to determine the effect of a model of restorative home care on physical function and social support among older people. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2013;94:1015–1022.

- Tessier A, Beaulieu M-D, Mcginn CA, et al. Effectiveness of reablement: a systematic review. Healthc Policy. 2016;11:49–59.

- Whitehead P, Parry R, Walker M, et al. How can occupational therapists contribute to reablement outcomes? A qualitative study. Br J Occup Ther. 2015;78:55.

- Tang F, Lee Y. Social support networks and expectations for aging in place and moving. Res Aging. 2011;33:444–464.

- Beresford B, Mayhew E, Duarte A, et al. Outcomes of reablement and their measurement: findings from an evaluation of English reablement services. Health Soc Care Commun. 2019;27:1438–1450.

- Legg L, Gladman J, Drummond A, et al. A systematic review of the evidence on home care reablement services. Clin Rehabil. 2016;30:741–749.

- Glendinning C, Clarke S, Hare P, et al. Progress and problems in developing outcomes-focused social care services for older people in England. Health Soc Care Commun. 2008;16:54–63.

- Hansen HP, Draborg E, Kristensen FB. Exploring qualitative research synthesis: the role of patients' perspectives in health policy design and decision making. Patient. 2011;4:143–152.

- Trappes-Lomax T, Hawton A. The user voice: older people's experiences of reablement and rehabilitation. J Integr Care. 2012;20:181–195.

- Moe A, Brataas HV. Interdisciplinary collaboration experiences in creating an everyday rehabilitation model: a pilot study. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2016;9:173–182.

- Hjelle KM, Alvsvåg H, Førland O. The relatives' voice: how do relatives experience participation in reablement? A qualitative study. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2017;10:1–11.

- Hjelle KM, Skutle O, Førland O, et al. The reablement team's voice: a qualitative study of how an integrated multidisciplinary team experiences participation in reablement. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2016;9:575–585.

- Jakobsen FA, Vik K. Health professionals’ perspectives of next of kin in the context of reablement. Disabil Rehabil. 2019;41:1882–1888.

- King AI, Parsons M, Robinson E. A restorative home care intervention in New Zealand: perceptions of paid caregivers. Health Soc Care Commun. 2012;20:70–79.

- Bondas T, Hall EOC. A decade of metasynthesis research in health sciences: a meta-method study. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-Being. 2007;2:101–113.

- Noblit GW, Hare RD. Meta-ethnography: synthesizing qualitative studies. Newbury Park (CA): Sage Publications; 1988.

- Sandelowski M. “Meta-Jeopardy”: the crisis of representation in qualitative metasynthesis. Nurs Outlook. 2006;54(1):10–16.

- Tong A, Flemming K, McInnes E, et al. Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2012;12:181.

- Sandelowski M, Barroso J. Handbook for synthesizing qualitative research. New York (NY): Springer Publishing Company; 2006.

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71.

- DeJean D, Giacomini M, Simeonov D, et al. Finding qualitative research evidence for health technology assessment. Qual Health Res. 2016;26:1307–1317.

- France EF, Uny I, Ring N, et al. A methodological systematic review of meta-ethnography conduct to articulate the complex analytical phases. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2019;19:35.

- Malterud K. Systematic text condensation: a strategy for qualitative analysis. Scand J Public Health. 2012;40:795–805.

- France EF, Cunningham M, Ring N, et al. Improving reporting of meta-ethnography: the eMERGe reporting guidance. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2019;19:25.

- Wilcock AA. Reflections on doing, being and becoming. Aust Occup Ther J. 2002;46:1–11.

- Hitch D, Pépin G, Stagnitti K. In the footsteps of Wilcock, part one: the evolution of doing, being, becoming, and belonging. Occup Ther Health Care. 2014;28:231–246.

- Hitch D, Pépin G, Stagnitti K. In the footsteps of Wilcock, part two: the interdependent nature of doing, being, becoming, and belonging. Occup Ther Health Care. 2014;28:247–263.

- Eliassen M, Henriksen N, Moe S. The practice of support personnel, supervised by physiotherapists, in Norwegian reablement services. Physiother Res Int. 2019;24:e1754.

- Vik K. Hverdagsrehabilitering og tverrfaglig samarbeid; en empirisk studie i fire norske kommuner. TFO. 2018;4:6–15.

- Jokstad K, Skovdahl K, Landmark BT, et al. Ideal and reality; community healthcare professionals' experiences of user-involvement in reablement. Health Soc Care Commun. 2019;27:907–916.

- Hjelle KM, Tuntland H, Forland O, et al. Driving forces for home-based reablement; a qualitative study of older adults' experiences. Health Soc Care Community. 2017;25:1581–1589.

- Hjelle KM, Skutle O, Alvsvag H, et al. Reablement teams' roles: a qualitative study of interdisciplinary teams' experiences. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2018;11:305–316.

- Gerrish K, Laker S, Wright S, et al. Medicines reablement in intermediate health and social care services. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2017;18:305–315.

- Whitehead PJ, Drummond AE, Parry RH, et al. Content and acceptability of an occupational therapy intervention in homecare re-ablement services (OTHERS). Br J Occup Ther. 2018;81:535–542.

- Wilde A, Glendinning C. ‘If they're helping me then how can I be independent?’ The perceptions and experience of users of home-care re-ablement services. Health Soc Care Commun. 2012;20:583–590.

- Burton E, Lewin G, Boldy D. Barriers and motivators to being physically active for older home care clients. Phys Occup Ther Geriatr. 2013;31(1):21–36.

- Östlund G, Zander V, Elfström ML, et al. Older adults’ experiences of a reablement process. “to be treated like an adult, and ask for what I want and how I want it”. Educ Gerontol. 2019;45(8):519–529.

- Bolenius K, Lamas K, Sandman P-O, et al. Perceptions of self-determination and quality of life among Swedish home care recipients–a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 2019;19:1–9.

- Zingmark M, Evertsson B, Haak M. The content of reablement: exploring occupational and physiotherapy interventions. Br J Occup Ther. 2019;82(2):122–126.

- Jones F, Partridge C, Reid F. The stroke self‐efficacy questionnaire: measuring individual confidence in functional performance after stroke. J Clin Nurs. 2008;17:244–252.

- van der Zee CH, Baars-Elsinga A, Visser-Meily JM, et al. Responsiveness of two participation measures in an outpatient rehabilitation setting. Scand J Occup Ther. 2013;20:201–208.

- Law M, Baptiste S, McColl M, et al. The Canadian occupational performance measure: an outcome measure for occupational therapy. Can J Occup Ther. 1990;57:82–87.

- Kjerstad E, Tuntland HK. Reablement in community-dwelling older adults: a cost-effectiveness analysis alongside a randomized controlled trial. Health Econ Rev. 2016;6:15.